Abstract

Aerobic methane-oxidizing bacteria (MOB) are a diverse group of microorganisms that are ubiquitous in natural environments. Along with anaerobic MOB and archaea, aerobic methanotrophs are critical for attenuating emission of methane to the atmosphere. Clearly, nitrogen availability in the form of ammonium and nitrite have strong effects on methanotrophic activity and their natural community structures. Previous findings show that nitrite amendment inhibits the activity of some cultivated methanotrophs; however, the physiological pathways that allow some strains to transform nitrite, expression of gene inventories, as well as the electron sources that support this activity remain largely uncharacterized. Here we show that Methylomicrobium album strain BG8 utilizes methane, methanol, formaldehyde, formate, ethane, ethanol, and ammonia to support denitrification activity under hypoxia only in the presence of nitrite. We also demonstrate that transcript abundance of putative denitrification genes, nirS and one of two norB genes, increased in response to nitrite. Furthermore, we found that transcript abundance of pxmA, encoding the alpha subunit of a putative copper-containing monooxygenase, increased in response to both nitrite and hypoxia. Our results suggest that expression of denitrification genes, found widely within genomes of aerobic methanotrophs, allow the coupling of substrate oxidation to the reduction of nitrogen oxide terminal electron acceptors under oxygen limitation. The present study expands current knowledge of the metabolic flexibility of methanotrophs by revealing that a diverse array of electron donors support nitrite reduction to nitrous oxide under hypoxia.

Keywords: methanotroph, nitrous oxide, denitrification, hypoxia, Methylomicrobium album BG8, methane monooxygenase, nitrite reduction

Introduction

Aerobic methane-oxidizing bacteria (MOB) form an important bridge between the global carbon and nitrogen cycles, a relationship impacted by the global use of nitrogenous fertilizers (Bodelier and Steenbergh, 2014). Ammonia (NH3) and nitrate (NO3-) can stimulate the activity of methanotrophs by acting as a nitrogen source for growth and biomass production (Bodelier et al., 2000; Bodelier and Laanbroek, 2004). Further, some methanotrophs such as Methylomonas denitrificans utilize NO3- as an oxidant for respiration under hypoxia (Kits et al., 2015). Evidently, denitrification in aerobic methanotrophs functions to conserve energy during oxygen (O2) limitation (Kits et al., 2015). Alternatively, NH3 and nitrite (NO2-) can act as significant inhibitors of methanotrophic bacteria (King and Schnell, 1994). NH3 is a competitive inhibitor of the methane monooxygenase enzyme and NO2-, produced by methanotrophs that can oxidize NH3 to NO2-, is a toxin with bacteriostatic properties that is known to inhibit the methanotroph formate dehydrogenase enzyme that is essential for the oxidation of formate to carbon dioxide (Dunfield and Knowles, 1995; Cammack et al., 1999; Nyerges et al., 2010).

In spite of the recent discovery that aerobic methanotrophs can denitrify, the energy sources, genetic modules, and environmental factors that govern denitrification in MOB are still poorly understood. M. denitrificans FJG1 respires NO3- using methane as an electron donor to conserve energy. However, it is not known whether C1 energy sources other than CH4 (methanol, formaldehyde, and formate) can directly support denitrification. Another possibility, which has not yet been investigated, is that C2 compounds (such as ethane and ethanol) and inorganic reduced nitrogen sources (NH3) support methanotrophic denitrification. Previous work shows that several obligate methanotrophs, including Methylomicrobium album strain BG8, oxidize ethane (C2H6) and ethanol (C2H6O) using particulate methane monooxygenase (pMMO) and methanol dehydrogenase (MDH), respectively, even though neither substrate supports growth (Whittenbury et al., 1970; Dalton, 1980; Mountfort, 1990). NH3 may be able to support methanotrophic denitrification because many aerobic methanotrophs are capable of oxidizing NH3 to NO2-: a process facilitated by the presence of a copper-containing monooxygenase (CuMMO) enzyme and, in some methanotrophs, a hydroxylamine dehydrogenase homolog (Poret-Peterson et al., 2008). The ability to utilize alternative energy sources to support denitrification would augment the metabolic flexibility of methanotrophs and enable them to sustain respiration in the absence of CH4 and/or O2.

Methylomicrobium album strain BG8 is an aerobic methanotroph that belongs to the phylum Gammaproteo bacteria; the genome lacks a soluble methane monooxygenase but does contain one particulate methane monooxygenase operon (pmoCAB – METAL_RS17430, 17425, 17420) and one operon encoding a putative copper monooxygenase (pxmABC – METAL_RS06980, 06975, 06970) with no known function. The genome also contains gene modules for import and assimilation of NH4+ (amtB – METAL_RS11045/gdhB – METAL_RS11695/glnA – METAL_RS11070/ald – METAL_RS11565), assimilation of NO3- (nasA – METAL_RS06040/nirB – METAL_RS15330, nirD – METAL_RS15325), oxidation of NH2OH to NO2- (haoA – METAL_RS13275), as well as putative denitrification genes – cytochrome cd1 nitrite reductase (nirS – METAL_RS10995), and two copies of cytochrome c-dependent nitric oxide reductase (norB1 – METAL_RS03925, norC1 – METAL_RS03930/norB2 – METAL_RS13345). The recent release of several genome sequences of aerobic methanotrophs, including M. album strain BG8, points to the frequent presence of putative nitrite and nitric oxide reductases, while only three cultivated methanotrophs possess a respiratory nitrate reductase (Stein and Klotz, 2011; Stein et al., 2011; Svenning et al., 2011; Khadem et al., 2012b; Vuilleumier et al., 2012; Kits et al., 2013). It is also unclear whether methanotrophs that lack a respiratory nitrate reductase but possess dissimilatory nitrite and nitric oxide reductases are still capable of denitrification from NO2-. Moreover, due to the significant divergence of the methanotroph nirS from known sequences, it is not known, whether nirS is the operational nitrite reductase in the methanotrophs that lack a nirK (Wei et al., 2015). While the genome of the nitrate respiring M. denitrificans FJG1 encodes both nirS and nirK nitrite reductases, transcript levels of only nirK increased in response to denitrifying conditions (Kits et al., 2015).

The goal of the present study was to test whether a variety of C1, C2, and inorganic energy sources can directly support denitrification, characterize the environmental factors that regulate NO2--dependent N2O production in M. album strain BG8 and to assess the expression of its putative denitrification inventory.

Materials and Methods

Cultivation

Methylomicrobium album strain BG8 was cultivated in 100 mL of nitrate mineral salts medium containing 11 mM KNO3 (NMS) or 10 mM KNO3 plus 1 mM NaNO2 (NMS + NO2-) in 300 mL glass Wheaton bottles topped with butyl rubber septa (Whittenbury et al., 1970). The NMS media was buffered to pH 6.8 using a phosphate buffer (0.26 g/L KH2PO4, 0.33 g/L Na2HPO4). The final concentration of copper (CuSO4) was 5 μM. Using a 60 mL syringe (BD) and a 0.22 μm filter/needle assembly, CH4 (99.998%) was added into the sealed bottles as a sole carbon source. The initial gas-mixing ratio in the headspace was adjusted using O2 gas (99.998%, Praxair) to 1.6:1, CH4 to O2 (or ca. 28% CH4, 21% O2). The initial pressure in the gas tight bottles was adjusted to ca. 1.3 atm to prevent a vacuum from forming during growth as gas samples and liquid culture samples were withdrawn every 12 h for analysis. Cultures were incubated at 30°C and shaken at 200 rpm. To track growth, the cultures were periodically sampled using a needle fitted syringe (0.5 mL) and cell density was determined by direct count with phase contrast microscopy using a Petroff–Hausser counting chamber. Six biological replicates were grown on separate days and data was collected on each replicate (n = 6). Culture purity was assessed by 16s rRNA gene sequencing, phase contrast microscopy, and plating on nutrient agar and TSA with absence of growth indicating no contamination. We assessed purity of the cultures prior to beginning all of the experiments and then assessed it again for each replicate at the conclusion of each experiment.

Gas Analysis

Concentrations of O2, CH4, and N2O were determined by sampling the headspace of each culture using gas chromatography (GC-TCD, Shimadzu GC8A; outfitted with a molecular sieve 5A and a Hayesep Q column, Alltech). The headspace of each batch culture was sampled with a 250 μL gastight syringe (SGE Analytical Science; 100 μL/injection) at 0 (immediately post inoculation), 6, 12, 16, 20, 24, 30, 36, 42, 48, 60, 72, 96, and 120 h. A total of 200 μL was sampled from each replicate at every time point. We determined the bottles were gastight by leaving a replicate set of bottles uninoculated throughout the experiment and measuring headspace gas concentrations; leakage was <1% over 120 h. Standard curves using pure gases O2, CH4, and N2O (Praxair) were generated and used to calculate the headspace concentrations in the batch cultures.

Instantaneous Micro-sensor Assays

Methylomicrobium album strain BG8 was grown in NMS + NO2- medium as described above. At 96 h of growth, when denitrification activity was highly evident, 4 × 1010 cells were harvested using a filtration manifold onto 0.2 μm filters (Supor 200, 47 mm, Pall Corporation). The biomass was washed three times with sterile, nitrogen-free mineral salts medium – identical to the mineral salts medium used for cultivation but devoid of NH4Cl, KNO3, or NaNO2. For data presented in Figures 2 and 4, the washed biomass was resuspended in the same nitrogen-free medium and transferred to a gastight 10 mL micro-respiration chamber equipped with an OX-MR O2 micro-sensor (Unisense) and an N2O-500 N2O micro-sensor (Unisense). For data presented in Figure 3, biomass was resuspended in mineral salts medium amended with 100 μM NaNO2. Data was logged using SensorTrace Basic software. CH4 gas, 0.001% CH3OH (HPLC grade methanol, Fisher Scientific), 0.01% CH2O (Methanol free 16% formaldehyde, Life technologies), 10 mM HCO2H, C2H6 gas (99.999%), 0.01% C2H6O (Methanol free 95% ethyl alcohol, Commercial Alcohols), 200 mM NH4Cl, and/or 1 M NO2- was injected directly into the chamber through the needle injection port with a gas-tight syringe (SGE Analytical Science). In Figures 3B–E, the dissolved O2 was decreased to <100 μmol/L (Figure 3B) and <25 μmol/L (Figures 3C–E), respectively, with additions of CH4 (Figure 3A), CH3OH (Figure 3B), CH2O (Figure 3C), HCO2H (Figure 3D), C2H6 (Figure 3E), C2H6O (Figure 3F) before data logging was enabled to limit the traces to <100 min and to reduce the number of sampling points. NO2- concentration was determined using a colorimetric method (Bollmann et al., 2011). Experiments were performed 3–4 times to demonstrate reproducibility of results and a single representative experiment was selected for presentation.

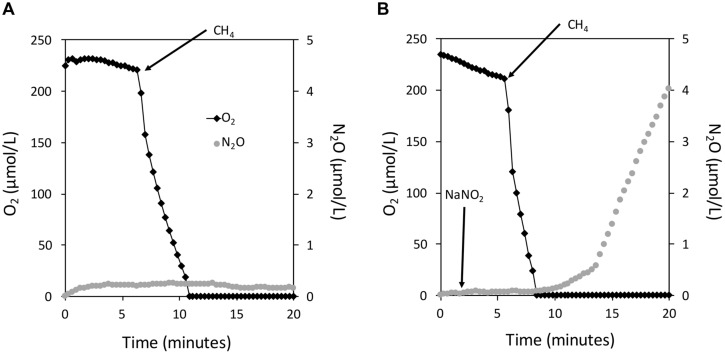

FIGURE 2.

The instantaneous coupling of CH4 oxidation to NO2- reduction in Methylomicrobium album strain BG8 under hypoxia. Experiments were performed in a closed 10 mL micro-respiratory chamber outfitted with an O2 and N2O microsensor and logged with Sensor Trace Basic software. O2 (black diamonds) and N2O (gray circles) were measured using microsensors. Cells of M. album strain BG8 were harvested as described in the materials and methods and resuspended in nitrogen free mineral salts medium. Arrows mark the addition of CH4 (∼300 μM) and NaNO2 (1 mM) to the micro-respiratory chamber in all panels. There is no measureable denitrification activity in the absence of NO2- (A); denitrification activity is dependent on CH4 and NO2- (B).

FIGURE 4.

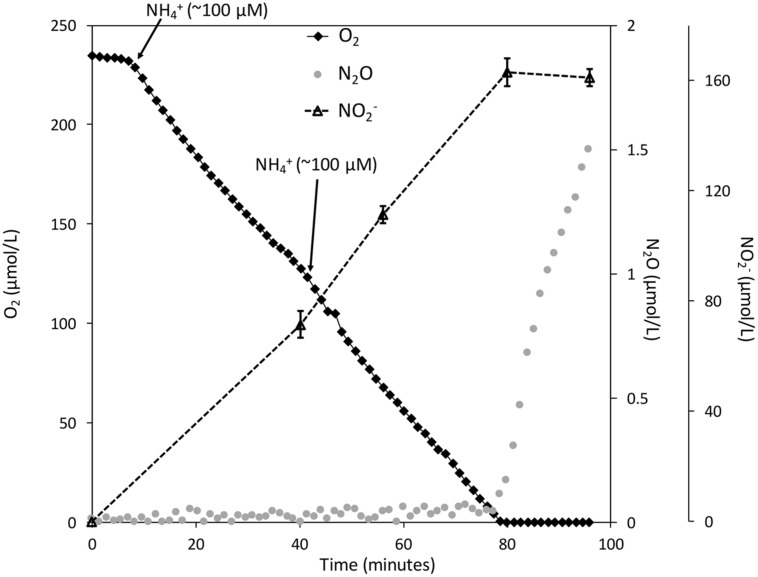

The coupling of NH3 oxidation to NO2- reduction in Methylomicrobium album strain BG8 under hypoxia. Experiments were performed in a closed 10 mL micro-respiratory chamber outfitted with an O2 and N2O microsensor and logged with Sensor Trace Basic software. O2 (black diamonds), N2O (gray circles), NO2- (black dashed triangles). Cells of M. album strain BG8 were grown and harvested as described in the materials and methods and resuspended in nitrogen free mineral salts medium. Arrows mark the addition of NH4+ (100 μM) to the closed micro-respiratory chamber. Traces (O2 + N2O) are single representatives of reproducible results from cultures grown on different days. NO2- was measured using a colorimetric method as described in the Section “Materials and Methods” and data points represent the mean ± SD for three technical replicates.

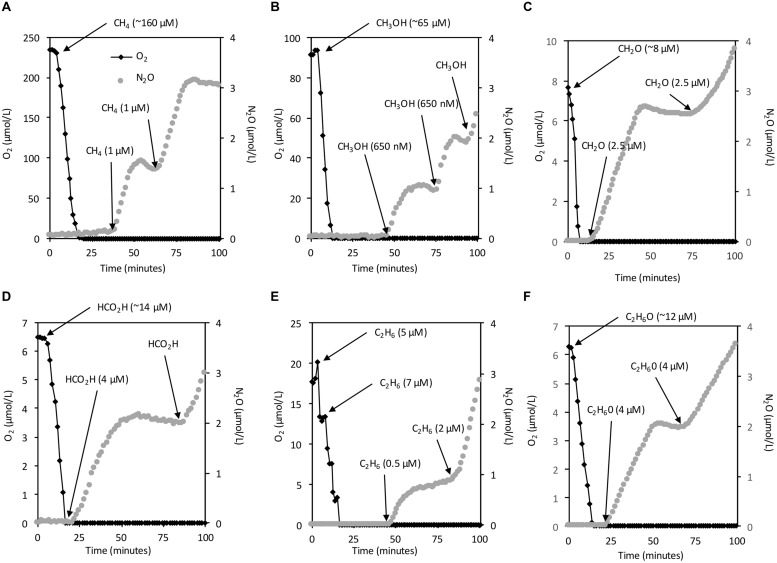

FIGURE 3.

NO2- reduction to N2O by M. album strain BG8 is dependent on an energy source at <50 nM O2. Experiments were performed in a closed 10 mL micro-respiratory chamber outfitted with an O2 and N2O microsensor and logged with Sensor Trace Basic software. O2 (black diamonds) and N2O (gray circles). Cells of M. album strain BG8 were harvested as described in the materials and methods and resuspended in mineral salts medium containing 100 μM NO2-. Arrows mark the addition of either CH4 (A), CH3OH (B), CH2O (C), HCO2H (D), C2H6 (E), C2H6O (F), in all panels. The right y-axis is identical in all panels. However, it should be noted that the left y-axis differs in all panels.

RNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted from ca. 109 M. album strain BG8 cells grown in NMS or NMS + NO2- medium at 24, 48, and 72 h using the MasterPure RNA purification kit (Epicentre). Briefly, cells were harvested by filtration through a 0.22 μm filter and inactivated with phenol–ethanol stop solution (5% phenol, 95% EtOH). Total nucleic acid was purified according to manufacturer’s instructions with the following modifications: 6 U proteinase K (Qiagen) were added to the cell lysis step and the total precipitated nucleic acid was treated with 30 units of DNase I (Ambion). The total RNA was then column-purified using RNA clean & concentrator (Zymo Research). RNA quality and quantity was assessed using BioAnalyzer (Agilent Technologies) and Qubit (Life Technologies). Residual genomic DNA contamination was assessed by quantitative PCR (qPCR) targeting norB1 or nirS genes (primers listed in Table 1). PCR conditions are described below. The total RNA samples were deemed free of genomic DNA if no amplification was detected after 40 cycles of qPCR. High quality RNA (RIN number >9, no gDNA detected) was converted to first strand cDNA using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies), according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Table 1.

qPCR Primers used in this study.

| Gene target | Locus tag1 | Primer set | Sequence (5′→3′) | qPCR efficiency | Standard curve – R2 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pxmA | METAL_RS06980 | QpxmA-FWD-3 | GCTTGTCAGGGCTTACGATTA | 97.7% – 101.8% | 0.9989 | This study |

| QpxmA-REV-3 | CTTCCAGTCCACCCAGAAATC | |||||

| pmoA | METAL_RS17425 | QpmoA-FWD-7 | GTTCAAGCAGTTGTGTGGTATC | 95.1% – 97.2% | 0.9999 | This study |

| QpmoA-REV-7 | GAATTGTGATGGGAACACGAAG | |||||

| nirS | METAL_RS10995 | QnirS-FWD-1 | GTCGACCTGAAGGACGATTT | 95.1% – 98.8% | 0.9999 | This study |

| QnirS-REV-1 | GTCACGATGCTGTCGTCATA | |||||

| norB1 | METAL_RS03925 | QnorB-FWD-2 | ACTGGCGGTGCACTATTT | 97.2% – 97.4% | 0.9998 | This study |

| QnorB-REV-2 | CATCCGGTTGACGTTGAAATC | |||||

| norB2 | METAL_RS13345 | QnorB-F-1 | CACCATGTACACCCTCATCTG | 96.2% – 102.2% | 0.9999 | This study |

| QnorB-R-1 | CCAAAGTCTGCGCAAGAAAC | 96.1% – 101.8% | 0.9999 | This study | ||

| 16S rRNA | METAL_RS04240 | 341F | CCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG | 96.9% – 102.2 % | 0.9997 | Muyzer et al., 1993 |

| 518R | ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG |

1The complete genome sequence of M. album strain BG8 is deposited in Genbank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/) under the accession NZ_CM001475 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term=methylomicrobium%20album%20Bg8).

Quantitiative PCR

Gene copy standards were created using the genomic DNA of M. album strain BG8 using universal and gene-specific primers (Table 1). A 10-fold dilution series (100–108 copies/20 μl reaction) of purified amplicons was prepared and used to establish an optimized qPCR condition. Each 20 μl reaction contained 10 μl of 2X qPCR SYBR based master mix (MBSU, University of Alberta), 0.2 μM of forward and reverse primer, 1 μl diluted cDNA, and nuclease-free water. Amplification was performed on a StepOne Plus qPCR system (Applied Biosystems) with an initial activation at 95°C for 3 min and fluorescence emission data collected from 40 cycles of amplification (95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 15 s). Target specificity was assessed by melt curve analysis, which ensured that a single peak was obtained. Gene copy number was estimated from cDNA diluted from 10-3 to 10-5 copies for 16S rRNA and pmoA transcript analyses and dilutions from 10-1 to 10-3 copies for nirS, norB1, norB2, and pxmA transcript analyses. The transcript abundance of each functional gene was normalized to that of 16s rRNA to yield a copy number of transcripts per one billion copies of 16s rRNA. Then, to calculate the N-fold change, we divided the transcript abundance (per one billion copies of 16s rRNA) in the NMS + NO2- cultures by transcript abundance (per one billion copies of 16s rRNA) in the NMS cultures. Samples were run in triplicate with three dilutions each on at least three biological replicates from cells grown and processed on separate dates. Quantitative PCR efficiencies ranged from 95–102% with r2-values of at least 0.99 for all assays (Table 1).

Statistics

A Student’s t-test (two tailed) was used to calculate the P-level between the control (NMS alone) and experimental (NMS + NO2-) replicates as indicated for each experiment. Equal variance between the control and experimental groups was determined using a two sample F test for variance. The doubling time, O2 and CH4 consumption, cell density, and total headspace O2 and CH4 consumed (Supplementary Table S1) all had equal variance between the control and experimental (F < Fcrit); thus a homoscedastic t-test was calculated for the aforementioned comparisons. For qPCR, comparisons between NMS + NO2- and NMS alone at 48 h for pmoA, pxmA, nirS, and norB1, as well as for pxmA and nirS at 72 h showed unequal variance (F > Fcrit); thus a heteroscedastic t-test was used to calculate the P-level for these comparisons. The variance between NMS + NO2- and NMS alone for all other genes at all other time points was equal (F < Fcrit).

Results

Growth Phenotype of Methylomicrobium album Strain BG8 in the Absence or Presence of NO2-

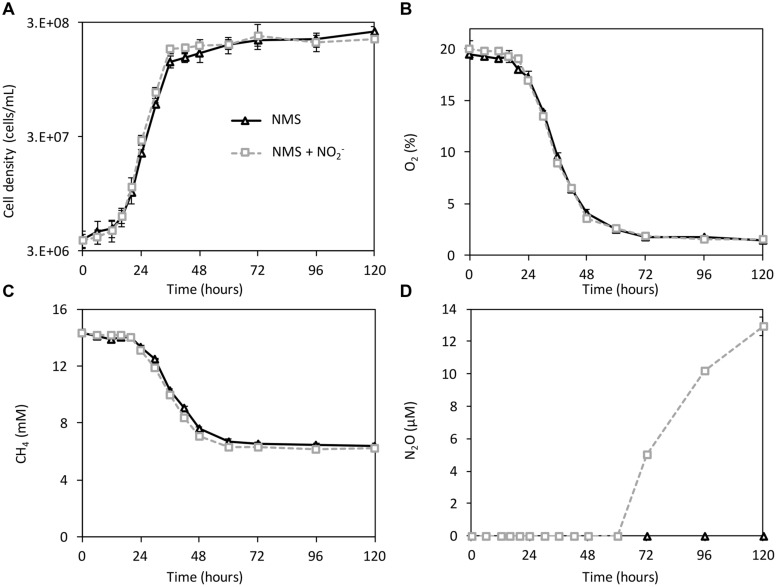

Methylomicrobium album strain BG8 was cultivated in NMS or NMS supplemented with NO2- over 120 h to determine the effect of NO2- on growth, O2 and CH4 consumption, and N2O production (Figure 1). The total amount of nitrogen was kept constant to eliminate a difference in N-availability and salt concentration between treatments. All of the cultures were initiated at an oxygen (O2) tension of 19.5 ± 0.7% (Figure 1B). As observed previously (Nyerges et al., 2010), NO2- amendment (1 mM) did not have an inhibitory effect on growth or substrate consumption of M. album strain BG8 (Figures 1A–C and Supplementary Table S1). The limiting substrate in all treatments was O2, as demonstrated by supplementing cultures with additional O2 (20 mL) after 48 h of growth and observing a significant increase in optical density in comparison to cultures not receiving additional O2 (Supplementary Figure S1). N2O production occurred only in the NMS plus NO2- cultures (Figure 1D). N2O production was first apparent in the headspace of NO2- amended cultures at 72 h of growth when O2 reached ca. 1.8% of the headspace and continued up to the termination of the experiment (120 h) at a rate of 9.3 × 10-18 mol N2O per cell per hour (Figure 1D). After 120 h of growth, the N2O yield percentage from the added NO2- (100 μmol) was 5.1 ± 0.2% (5.1 ± 0.2 μmol) in the NMS + NO2- cultures.

FIGURE 1.

Growth, CH4 and O2 consumption, and N2O production by Methylomicrobium album strain BG8 cultivated on NMS and NMS plus 1 mM NaNO2. Methylomicrobium album strain BG8 was cultivated for 5 days in 100 mL of NMS (black triangles) or NMS + 1 mM NO2- (gray dashed squares) media in 300 mL closed glass Wheaton bottles sealed with butyl rubber septum caps. The initial headspace gas-mixing ratio of CH4 to O2 was 1.6:1. Cell density (A) was measured using direct count with a Petroff–Hausser counting chamber and headspace gas concentrations of O2 (B), CH4 (C) and N2O (D) were measured using GC-TCD. All data points represent the mean ± SD for six biological replicates (n = 6).

O2 Consumption and N2O Production by Resting Cells of M. album Strain BG8 with Single or Double Carbon Substrates or Ammonium under Atmospheric and Hypoxic O2 Tensions

To determine which conditions govern N2O production in M. album strain BG8, we measured instantaneous O2 consumption and N2O production by M. album strain BG8 with CH4 as the sole carbon and energy source in a closed 10-mL micro-respiratory (MR) chamber outfitted with O2 and N2O-detecting microsensors. Introduction of CH4 (300 μM) into the chamber led to immediate O2 consumption; O2 declined to below the detection limit of the sensor (<50 nM O2) after ca. 3 min (Figure 2A). Addition of NO2- to the chamber led to production of N2O shortly after O2 declined below the detection limit at a rate of 7.9 × 10-18 mol cell-1 h-1 (Figure 2B). In the absence of NO2-, we observed no measureable N2O production (Figure 2A). Though the O2 concentration is <50nM O2 when N2O production is evident, it is important to note that M. album strain BG8 still requires O2 for methane oxidation and cannot grow on CH4 anaerobically.

Using the same setup described above, we supplemented resting cells in the MR chamber with CH3OH, CH2O, HCO2H, C2H6, or C2H6O to experimentally address whether carbon-based reductant sources other than CH4 support denitrification in M. album strain BG8. Also, to substantiate that the one- and two-carbon sources we tested can all serve as direct electron donors for denitrification by M. album strain BG8 under hypoxia, we provided resting cells only enough reductant to consume the dissolved O2 (ca. 234 μmol/L) present in the MR chamber sparing no reductant to support denitrification (Figure 3). We then measured instantaneous N2O production through serial addition of small quantities of CH4, CH3OH, CH2O, HCO2H, C2H6, or C2H6O to the MR chamber, which contained medium supplemented with NaNO2 (100 μM; Figure 3). For all six substrates, N2O production was stoichiometric with the amount of added substrate (Figure 3).

Many methanotrophs, including M. album BG8, can oxidize NH3 to NO2- due to homologous inventory to ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (Yoshinari, 1985; Bedard and Knowles, 1989; King and Schnell, 1994; Holmes et al., 1995; Poret-Peterson et al., 2008; Campbell et al., 2011; Stein and Klotz, 2011). We aimed to test whether reductant and NO2- from NH3 oxidation could also drive denitrification by M. album strain BG8. Resting cells in the MR chamber consumed the dissolved O2 promptly after NH4Cl (200 μM) was injected into the chamber (Figure 4). After ca. 70 min, the biomass depleted the dissolved O2 to <50 nM and NO2- concentration reached 163 ± 5 μM. The rate of N2O production following O2 depletion was 1.2 × 10-18 mol cell-1 h-1.

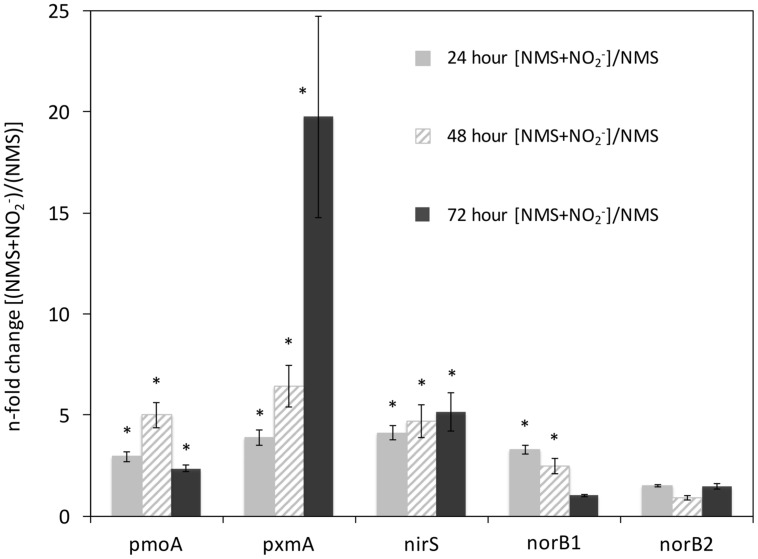

Expression of Predicted Denitrification Genes in M. album Strain BG8 under Denitrifying Conditions

The genome of M. album strain BG8 encodes several genes predicted to be involved in denitrification. The first step in respiratory denitrification is the one-electron reduction of NO3- to NO2-; a reaction performed by one of two membrane-associated dissimilatory nitrate reductase enzymes, neither of which is encoded in the M. album strain BG8 genome (Kits et al., 2013). The second step in denitrification, the one-electron reduction of NO2- to NO is carried out by one of two non-homologous nitrite reductases, either a copper containing (nirK) or a cytochrome cd1 containing (nirS) nitrite reductase, of which the latter was annotated in the genome (Kits et al., 2013). The genome of M. album strain BG8 also contains two copies of a putative cytochrome c-dependent nitric oxide reductase (norB1 and norB2, respectively). We also investigated expression of the pxmA gene of the pxmABC operon that encodes a CuMMO with evolutionarily relatedness to particulate methane monooxygenase (Tavormina et al., 2011). We chose to examine expression of pxmA in M. album strain BG8 to determine whether this gene responded similarly to that of M. denitrificans FJG1; expression of the pxmABC operon in M. denitrificans FJG1 significantly increased in response to denitrifying conditions (Kits et al., 2015).

To assess the effect of NO2- amendment on gene expression, we used cultures grown in NMS alone as the control. The O2 concentration in the headspace of NMS and NMS + NO2- cultures after 24 h growth was ca. 17.2 and 16.9%, respectively (Figure 1B). The transcript levels of pmoA, pxmA, nirS, and norB1 were significantly higher at the 24 and 48 h time points in the NO2- amended cultures when compared to the NMS alone (Figure 5). At the 72 h time point, levels of pmoA and nirS transcript levels remained significantly elevated in the NMS + NO2- relative to the NMS only cultures, whereas expression of norB1 was no longer significantly elevated (Figure 5). Most interestingly, the transcript abundance of pxmA at 72 h was 19.8-fold higher in NMS + NO2- relative to NMS only cultures (Figure 5). The second copy of norB (norB2) was unresponsive (below twofold) to NO2- amendment at all time points sampled.

FIGURE 5.

Expression of pmoA, pxmA, nirS, norB1, and norB2 in Methylomicrobium album strain BG8 cultivated in NMS or NMS media amended with 1 mM NaNO2. Total RNA was extracted from Methylomicrobium album strain BG8 at 24, 48, and 72 h of growth (see Figure 1) from three separate cultures, converted to cDNA, and the abundance of pmoA, pxmA, nirS, norB1, and norB2 transcripts was determined using quantitative PCR. The transcript abundance of each gene of interest was normalized to that of 16s rRNA. The n-fold change in transcript abundance of the NO2- amended (1 mM NaNO2) NMS cultures relative to the unamended NMS cultures at 24 h of growth (light gray), 48 h of growth (diagonal white/gray), and at 72 h of growth (black). Error bars represent the SD calculated for triplicate qPCR reactions performed on each of the three biological replicates for each treatment. The (∗) above the bars designates a statistical significance (P < 0.05) as determined by t-test between NMS only and NMS + NO2- for each time point.

Discussion

Methylomicrobium album Strain BG8 Produces N2O Only as a Function of Hypoxia and NO2-

Batch cultivation of M. album BG8 clearly revealed that both NO2- and low O2 were required for denitrification, as measured by N2O production. Although batch cultures of M. album strain BG8 have been shown to produce N2O previously in end-point assays (Nyerges et al., 2010), the mechanism and required conditions for denitrification by this strain were not determined until now. N2O production by M. denitrificans FJG1 was also shown to be dependent on hypoxia (Kits et al., 2015); however, this strain was able to respire NO3- in addition to NO2- likely due to the presence of a narGHJI dissimilatory nitrate reductase that is absent in the genome of M. album strain BG8. The genome of M. album strain BG8 encodes putative dissimilatory nitrite (nirS) and nitric oxide (norB) reductases (Kits et al., 2013) like M. denitrificans FJG1; hence, it is likely that N2O by M. album strain BG8 is from the enzymatic reduction of NO2- to N2O via the intermediate NO.

The correlation between N2O production and low O2 tension is similar to two other microbial processes, aerobic denitrification in heterotrophic bacteria such as Paracoccus denitrificans and nitrifier denitrification in ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (Richardson et al., 2001; Kozlowski et al., 2014). Aerobic denitrification in chemoorganoheterotrophs and nitrifier-denitrification in ammonia-oxidizing bacteria is a tactic used to maximize respiration during O2 limitation or to expend surplus reductant (Richardson et al., 2001; Stein, 2011). Utilization of NO2- in combination with or instead of O2 in the respiratory chain of M. album strain BG8 would reduce the overall cellular O2 demand, thus conserving O2 for additional CH4 oxidation. Thus, it is possible that M. album strain BG8 uses NO2- as a terminal electron acceptor under O2 limitation to maximize total respiration. The N2O yield percentage from NO2- by M. album strain BG8 (5.1 ± 0.2%) is similar to that of Nitrosomonas europaea ATCC 19718 (ca. 4.8%) and one order of magnitude higher than that of Nitrosospira multiformis ATCC 25196 (0.27 ± 0.05%; Kozlowski et al., 2014; Stieglmeier et al., 2014).

Denitrification by M. album Strain BG8 is Enzymatically Supported by Diverse Reductant Sources

Resting cells of M. album strain BG8 reduced NO2- to N2O at the expense of any of four tested C1 substrates (CH4, CH3OH, CH2O, HCO2H), the two C2 substrates (C2H6, C2H6O), and NH4Cl. These data show that intermediates of the methanotrophic pathway and co-substrates of pMMO, MDH, and likely hydroxylamine dehydrogenase support respiratory denitrification. These results agree with previous work on the methanotroph Methylocystis sp. strain SC2, which couples CH3OH oxidation to denitrification under anoxia (Dam et al., 2013). Remarkably, both C2 compounds we tested – C2H6 and C2H6O – supported denitrification. The ability of C2 compounds to support denitrification in methanotrophs may have environmental significance as natural gas consists of ∼1.8–5.1% (vol%) C2H6 (Demirbas, 2010). Further, C2H6O is a significant product of fermentation by primary fermenters during anoxic decomposition of organic compounds (Reith et al., 2002). The results also demonstrate that electrons derived from the oxidation of NH3 to NO2- were effectively utilized by nitrite and nitric oxide reductases in M. album strain BG8, which represents yet another pathway for methanotrophic N2O production that is not directly dependent on single-carbon metabolism, provided that the methane monooxygenase can access endogenous reductant (Dalton, 1977; King and Schnell, 1994; Stein and Klotz, 2011).

Instantaneous O2 consumption and N2O production measurements (Figures 2–4) provide strong support that catabolism of C1 – C2 substrates and ammonia is directly coupled to NO2- reduction under hypoxia in M. album strain BG8. Some aerobic methanotrophs ferment CH4 and excrete organic compounds such as citrate, acetate, succinate, and lactate (Kalyuzhnaya et al., 2013). Some studies also suggest that methanotrophs only support denitrification within CH4-fed consortia by supplying these excreted organics to denitrifying bacteria, since methanotrophs were thought incapable of denitrification by themselves (Costa et al., 2000; Knowles, 2005; Liu et al., 2014). Although M. album strain BG8 may excrete organic compounds under hypoxia when provided with CH4, the ability of CH3OH, CH2O, HCO2H, C2H6, C2H6O, or NH3 oxidation to support denitrification unequivocally demonstrates the linkage between methanotroph-specific enzymology and denitrifying activity within a single organism.

Transcription of Predicted Denitrification Genes, nirS and norB1, Increased in Response to NO2- but not Hypoxia

The expression of a nirS homolog in an aerobic methanotroph has been investigated so far only in the NO3- respiring M. denitrificans FJG1 (Kits et al., 2015). Interestingly, the genome of M. denitrificans FJG1 encodes both the copper-containing (nirK) and cytochrome cd1 containing (nirS) nitrite reductases and only the steady state mRNA levels of nirK increased in this strain in response to simultaneous O2 limitation and NO3- availability (Kits et al., 2015). In the case of M. album strain BG8, which only possesses a nirS homolog, we showed that the abundance of this nirS transcript responded positively to NO2- treatment but not to O2 limitation. This suggests that NO2- availability alone elicits the expression of nirS, even though hypoxia was required for NO2- reduction to occur.

The cytochrome c dependent nitric oxide reductase (norB) is widely found in the genomes of aerobic methanotrophs (Stein and Klotz, 2011). This may in part be due to the need to detoxify NO that is produced during aerobic ammonia oxidation by reducing it to N2O (Sutka et al., 2003). The expression of norB in Methylococcus capsulatus strain Bath increased 4.8-fold after treatment with 0.5 mM sodium nitroprusside, a NO releasing compound (Campbell et al., 2011). It is possible that the NorB protein is involved in detoxification of NO during NH3 oxidation in M. capsulatus strain Bath, since the genome lacks a dissimilatory nitrite reductase. More recently, it was demonstrated in M. fumariolicum strain SolV that transcription of norB was upregulated during O2 limitation during chemostat growth (Khadem et al., 2012a); however, it is unknown whether M. fumariolicum strain SolV can consume NO2- or NO. The transcription of norB in M. denitrificans FJG1 increased 2.8-fold in response to NO3- and hypoxia (Kits et al., 2015). While the genome of M. album strain BG8 encodes two copies of the norB gene, only one copy (norB1) is followed by norC – the essential cytochrome c-containing subunit (Mesa et al., 2002). Although some organisms like Cupriavidus necator possess two independent functional nitric oxide reductases (Cramm et al., 1997), the present work illustrates that expression of only norB1 in M. album strain BG8 is responsive to NO2- treatment. Although the function of NorB may differ between M. album strain BG8 and M. capsulatus strain Bath, both bacteria show a similar transcriptional response of norB genes to NO2- (Campbell et al., 2011).

Transcript Abundance of pxmA Significantly Increased in Response to both NO2- and Hypoxia

Genomes of some aerobic methanotrophs belonging to the phylum Gammaproteobacteria have been shown to encode a sequence divergent CuMMO protein complex, pXMO (Tavormina et al., 2011). The function and substrate of the putative pXMO protein encoded by the pxm operon remains unknown. Previous studies on the pxm operon have shown that it is expressed at low levels during growth in Methylomonas sp. strain LW13 as well as in freshwater peat bog and creek sediment (Tavormina et al., 2011). Metagenomic sequencing of the SIP-labeled active community in an oilsands tailings pond revealed that pxmA sequences were present in the active methanotroph community (Saidi-Mehrabad et al., 2013). Analysis of the transcriptome of M. denitrificans FJG1 revealed that steady state mRNA levels of the pxmABC operon increased ∼10-fold in response to denitrifying conditions (Kits et al., 2015).

We now demonstrate that expression of pxmA in M. album strain BG8 is significantly increased in response to both NO2- and hypoxia. We did not observe any increase in the expression of pxmA in O2 limited NMS-only cultures where denitrification was not occurring, suggesting that hypoxia alone is not sufficient to illicit an increase in the steady state mRNA levels. This study adds further support to the observation that expression of pxmA is responsive to denitrifying conditions. However, it must be noted that at 72 h in the NO2- amended media, absolute transcript abundance of pxmA (1 × 103 copies pxmA/1 × 109 copies 16s rRNA) was three orders of magnitude lower than absolute transcript abundance of pmoA (1 × 106 copies pxmA/1 × 109 copies 16s rRNA).

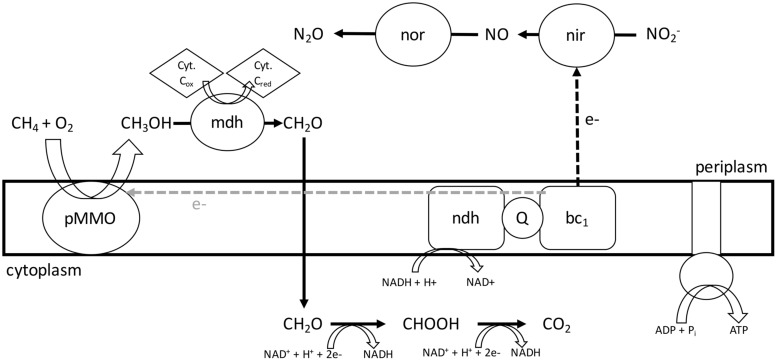

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that an aerobic methanotroph – M. album strain BG8 – couples the oxidation of C1 (CH4, CH3OH, CH2O, HCO2H), C2 (C2H6, C2H6O), and inorganic (NH3) substrates to NO2- reduction under O2 limitation resulting in release of the potent greenhouse gas N2O. The ability to couple C1, C2, and inorganic energy sources to O2 respiration and denitrification gives M. album strain BG8 considerable metabolic flexibility. We propose a model for methane driven denitrification in M. album strain BG8 (Figure 6). This discovery has implications for the environmental role of methanotrophic bacteria in the global nitrogen cycle in both N2O emissions and N-loss. Comparing the genome and physiology of the NO2- respiring M. album strain BG8 to NO3- respiring M. denitrificans FJG1 suggests that the inability of M. album strain BG8 to reduce NO3- to N2O is likely due to the absence of a dissimilatory nitrate reductase in the genome, but that expression of predicted denitrification genes, nirS and norB1, enable this aerobic methanotroph to respire NO2-.

FIGURE 6.

Proposed model for NO2- respiration and central metabolism in Methylomicrobium album strain BG8. During hypoxia, M. album strain BG8 utilizes electrons from aerobic CH4 oxidation to respire NO2-. Abbreviations: pMMO, particulate methane monooxygenase; mdh, methanol dehydrogenase; Cyt, cytochrome; nor, nitric oxide reductase; nir, nitrite reductase; ndh, NAD(P)H dehydrogenase complex; Q, coenzyme Q; bc1, cytochrome bc1 complex.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant to LS from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2014-03745) and fellowship support to KK from Alberta Innovates Technology Futures.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01072

References

- Bedard C., Knowles R. (1989). Physiology, biochemistry, and specific inhibitors of ch4, nh4+, and co oxidation by methanotrophs and nitrifiers. Microbiol. Rev. 53 68–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodelier P., Laanbroek H. (2004). Nitrogen as a regulatory factor of methane oxidation in soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 47 265–277. 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00304-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodelier P. L. E., Roslev P., Henckel T., Frenzel P. (2000). Stimulation by ammonium-based fertilizers of methane oxidation in soil around rice roots. Nature 403 421–424. 10.1038/35000193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodelier P. L. E., Steenbergh A. K. (2014). Interactions between methane and the nitrogen cycle in light of climate change. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 9–10, 26–36. 10.1016/j.cosust.2014.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bollmann A., French E., Laanbroek H. J. (2011). Isolation, cultivation, and characterization of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea adapted to low ammonium concentrations. Methods Enzymol. 486(Pt a), 55–88. 10.1016/B978-0-12-381294-0.00003-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammack R., Joannou C. L., Cui X. Y., Martinez C. T., Maraj S. R., Hughes M. N. (1999). Nitrite and nitrosyl compounds in food preservation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1411 475–488. 10.1016/S0005-2728(99)00033-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. A., Nyerges G., Kozlowski J. A., Poret-Peterson A. T., Stein L. Y., Klotz M. G. (2011). Model of the molecular basis for hydroxylamine oxidation and nitrous oxide production in methanotrophic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 322 82–89. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02340.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa C., Dijkema C., Friedrich M., Garcia-Encina P., Fernandez-Polanco F., Stams A. J. M. (2000). Denitrification with methane as electron donor in oxygen-limited bioreactors. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 53 754–762. 10.1007/s002530000337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramm R., Siddiqui R. A., Friedrich B. (1997). Two isofunctional nitric oxide reductases in Alcaligenes eutrophus H16. J. Bacteriol. 179 6769–6777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton H. (1977). Ammonia oxidation by methane oxidizing bacterium Methylococcus-Capsulatus strain bath. Arch. Microbiol. 114 273–279. 10.1038/ismej.2008.71 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton H. (1980). Oxidation of hydrocarbons by methane monooxygenases from a variety of microbes. Advan. Appl. Microbiol. 26 71–87. 10.1016/S0065-2164(08)70330-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dam B., Dam S., Blom J., Liesack W. (2013). Genome analysis coupled with physiological studies reveals a diverse nitrogen metabolism in Methylocystis sp. Strain SC2. PLoS ONE 8:e74767 10.1371/journal.pone.0074767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demirbas A. (2010). Methane gas hydrate. Methane Gas Hydrate 1–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dunfield P., Knowles R. (1995). Kinetics of inhibition of methane oxidation by nitrate, nitrite, and ammonium in a humisol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61 3129–3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes A. J., Costello A., Lidstrom M. E., Murrell J. C. (1995). Evidence that particulate methane monooxygenase and ammonia monooxygenase may be evolutionarily related. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 132 203–208. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07834.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyuzhnaya M. G., Yang S., Rozova O. N., Smalley N. E., Clubb J., Lamb A., et al. (2013). Highly efficient methane biocatalysis revealed in a methanotrophic bacterium. Nat. Commun. 4:2785 10.1038/ncomms3785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadem A. F., Pol A., Wieczorek A. S., Jetten M. S. M., Op den Camp H. J. M. (2012a). Metabolic regulation of “Ca. Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum” soIV cells grown under different nitrogen and oxygen limitations. Front. Microbiol. 3:266 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadem A. F., Wieczorek A. S., Pol A., Vuilleumier S., Harhangi H. R., Dunfield P. F., et al. (2012b). Draft genome sequence of the volcano-inhabiting thermoacidophilic methanotroph Methylacidiphilum fumariolicum strain SoLV. J. Bacteriol. 194 3729–3730. 10.1128/JB.00501-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G. M., Schnell S. (1994). Ammonium and nitrite inhibition of methane oxidation by methylobacter-albus bg8 and methylosinus-trichosporium ob3b at low methane concentrations. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60 3508–3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kits K. D., Kalyuzhnaya M. G., Klotz M. G., Jetten M. S. M., Op den Camp H. J. M., Vuilleumier S., et al. (2013). Genome sequence of the obligate gammaproteobacterial methanotroph Methylomicrobium album strain BG8. Genome Announc. 1:e0017013 10.1128/genomeA.00170-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kits K. D., Klotz M. G., Stein L. Y. (2015). Methane oxidation coupled to nitrate reduction under hypoxia by the Gammaproteobacterium Methylomonas denitrificans, sp. nov. type strain FJG1. Environ. Microbiol. 17 3219–3232. 10.1111/1462-2920.12772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles R. (2005). Denitrifiers associated with methanotrophs and their potential impact on the nitrogen cycle. Ecol. Eng. 24 441–446. 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2005.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski J. A., Price J., Stein L. Y. (2014). Revision of N2O-producing pathways in the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium Nitrosomonas europaea ATCC 19718. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80 4930–4935. 10.1128/AEM.01061-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Sun F., Wang L., Ju X., Wu W., Chen Y. (2014). Molecular characterization of a microbial consortium involved in methane oxidation coupled to denitrification under micro-aerobic conditions. Microb. Biotechnol. 7 64–76. 10.1111/1751-7915.12097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesa S., Velasco L., Manzanera M. E., Delgado M. J., Bedmar E. J. (2002). Characterization of the norCBQD genes, encoding nitric oxide reductase, in the nitrogen fixing bacterium Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Microbiology 148 3553–3560. 10.1099/00221287-148-11-3553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountfort D. O. (1990). Oxidation of aromatic alcohols by purified methanol dehydrogenase from Methylosinus-Trichosporium. J. Bacteriol. 172 3690–3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muyzer G., de Waal E. C., Uitterlinden A. G. (1993). Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16s rRna. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59 695–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyerges G., Han S., Stein L. Y. (2010). Effects of ammonium and nitrite on growth and competitive fitness of cultivated methanotrophic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76 5648–5651. 10.1128/AEM.00747-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poret-Peterson A. T., Graham J. E., Gulledge J., Klotz M. G. (2008). Transcription of nitrification genes by the methane-oxidizing bacterium, Methylococcus capsulatus strain bath. ISME J. 2 1213–1220. 10.1038/ismej.2008.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reith F., Drake H. L., Kusel K. (2002). Anaerobic activities of bacteria and fungi in moderately acidic conifer and deciduous leaf litter. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 41 27–35. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb00963.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson D. J., Berks B. C., Russell D. A., Spiro S., Taylor C. J. (2001). Functional, biochemical and genetic diversity of prokaryotic nitrate reductases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 58 165–178. 10.1007/PL00000845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saidi-Mehrabad A., He Z., Tamas I., Sharp C. E., Brady A. L., Rochman F. F., et al. (2013). Methanotrophic bacteria in oilsands tailings ponds of northern Alberta. ISME J. 7 908–921. 10.1038/ismej.2012.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L. Y. (2011). “Heterotrophic nitrification and nitrifier denitrification,” in Nitrification, eds. Ward B. B., Arp D. J., Klotz M. G. (Washington, DC: ASM Press; ). 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Stein L. Y., Bringel F., DiSpirito A. A., Han S., Jetten M. S. M., Kalyuzhnaya M. G., et al. (2011). Genome sequence of the methanotrophic alphaproteobacterium Methylocystis sp strain rockwell (ATCC 49242). J. Bacteriol. 193 2668–2669. 10.1128/JB.00278-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L. Y., Klotz M. G. (2011). Nitrifying and denitrifying pathways of methanotrophic bacteria. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39 1826–1831. 10.1042/BST20110712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stieglmeier M., Mooshammer M., Kitzler B., Wanek W., Zechmeister-Boltenstern S., Richter A., et al. (2014). Aerobic nitrous oxide production through N-nitrosating hybrid formation in ammonia-oxidizing archaea. ISME J. 8 1135–1146. 10.1038/ismej.2013.220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutka R. L., Ostrom N. E., Ostrom P. H., Gandhi H., Breznak J. A. (2003). Nitrogen isotopomer site preference of N2O produced by Nitrosomonas europaea and Methylococcus capsulatus bath. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 17 738–745. 10.1002/rcm.968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svenning M. M., Hestnes A. G., Wartiainen I., Stein L. Y., Klotz M. G., Kalyuzhnaya M. G., et al. (2011). Genome sequence of the arctic methanotroph Methylobacter tundripaludum SV96. J. Bacteriol. 193 6418–6419. 10.1128/JB.05380-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavormina P. L., Orphan V. J., Kalyuzhnaya M. G., Jetten M. S. M., Klotz M. G. (2011). A novel family of functional operons encoding methane/ammonia monooxygenase-related proteins in gammaproteobacterial methanotrophs. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 3 91–100. 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuilleumier S., Khmelenina V. N., Bringel F., Reshetnikov A. S., Lajus A., Mangenot S., et al. (2012). Genome sequence of the haloalkaliphilic methanotrophic bacterium Methylomicrobium alcaliphilum 20Z. J. Bacteriol. 194 551–552. 10.1128/JB.06392-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Isobe K., Nishizawa T., Zhu L., Shiratori Y., Ohte N., et al. (2015). Higher diversity and abundance of denitrifying microorganisms in environments than considered previously. ISME J. 9 1954–1965. 10.1038/ismej.2015.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittenbury R., Phillips K. C., Wilkinson J. F. (1970). Enrichment, isolation and some properties of methane-utilizing bacteria. J. Gen. Microbiol. 61 205–218. 10.1099/00221287-61-2-205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinari T. (1985). Nitrite and nitrous oxide production by Methylosinus trichosporium. Can. J. Microbiol. 31 139–144. 10.1139/m85-027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.