Abstract

Background and Purpose

We have reported that exposure to a diabetic intrauterine environment during pregnancy increases blood pressure in adult offspring, but the mechanisms involved are not completely understood. This study was designed to analyse a possible role of perivascular sympathetic and nitrergic innervation in the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) in this effect.

Experimental Approach

Diabetes was induced in pregnant Wistar rats by a single injection of streptozotocin. Endothelium-denuded vascular rings from the offspring of control (O-CR) and diabetic rats (O-DR) were used. Vasomotor responses to electrical field stimulation (EFS), NA and the NO donor DEA-NO were studied. The expressions of neuronal NOS (nNOS) and phospho-nNOS (P-nNOS) and release of NA, ATP and NO were determined. Sympathetic and nitrergic nerve densities were analysed by immunofluorescence.

Key Results

Blood pressure was higher in O-DR animals. EFS-induced vasoconstriction was greater in O-DR animals. This response was decreased by phentolamine more in O-DR animals than their controls. L-NAME increased EFS-induced vasoconstriction more strongly in O-DR than in O-CR segments. Vasomotor responses to NA or DEA-NO were not modified. NA, ATP and NO release was increased in segments from O-DR. nNOS expression was not modified, whereas P-nNOS expression was increased in O-DR. Sympathetic and nitrergic nerve densities were similar in both experimental groups.

Conclusions and Implications

The activity of sympathetic and nitrergic innervation is increased in SMA from O-DR animals. The net effect is an increase in EFS-induced contractions in these animals. These effects may contribute to the increased blood pressure observed in the offspring of diabetic rats.

Tables of Links

| TARGETS | |

|---|---|

| GPCRsa | Enzymesc |

| α2 adrenoceptor | Dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH) |

| P2Y receptors | |

| Ligand-gated ion channelsb | iNOS |

| P2X4 receptor | nNOS |

| LIGANDS | |

|---|---|

| 1400 W | NA |

| ACh | Nitric oxide (NO) |

| ATP | Phentolamine |

| CGRP | Suramin |

| CGRP (8-37) | TTX |

| L-NAME |

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (a,b,cAlexander et al., 2013a,b,c).

Introduction

A growing body of evidence during the last decade suggests that adverse environmental conditions during crucial periods of development may cause profound structural and biochemical changes in the body, resulting in modifications that, in later life, can become threats to health (Barker, 2004; Visentin et al., 2014). In line with this, maternal diabetes is a common medical complication in pregnancy that has been rapidly increasing worldwide. Both epidemiological investigations and animal studies have shown that intrauterine exposure to a hyperglycaemic environment can affect embryonic and fetal life, predisposing the offspring to develop metabolic disorders, including diabetes and hypertension in adult life (Simeoni and Barker, 2009).

The molecular mechanism underlying the association between diabetes during pregnancy and elevated blood pressure in the offspring remains unclear, and the relatively few existing studies have rarely address vascular function. Holemans et al. (1999) showed a reduced relaxation to endothelium-dependent dilators and enhanced constriction to NA in small mesenteric arteries in the offspring of diabetic rats. Rocha et al. (2005) and Tran et al. (2008) found early life hypertension with renal function impairment and decreased endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in mesenteric microvessels. We ourselves have recently demonstrated an enhanced formation of vasoconstrictor prostanoids in mesenteric resistance arteries from the offspring of diabetic rats, which contributes to a hyper-reactivity to NA that may participate in their hypertension (Ramos-Alves et al., 2012a,b,).

It is well known that vascular tone is determined by an equilibrium among several mechanisms in which perivascular innervation plays an important role. Tone regulation involves sympathetic, cholinergic, nitrergic, peptidergic and/or sensory neurons that are specific to the vascular bed under consideration (Loesch, 2002; Sastre et al., 2010). It is well known that the splanchnic circulation makes an important haemodynamic contribution to the early development of hypertension, and an increase in vascular resistance is apparent in various splanchnic organs (Meininger et al., 1985). The superior mesenteric artery (SMA) regulates around 20% of total blood flow; thus, changes in mesenteric vascular tone are involved in total peripheral resistance. The application of electrical field stimulation (EFS) produces a vasoconstrictor response that is the integrated result of the release of different neurotransmitters, including the sympathetic vasoconstrictors NA and ATP, NO from nitrergic neurons and CGRP from sensory nerves (Kawasaki et al., 1988; Li and Duckles, 1992; Marín and Balfagón, 1998; Blanco-Rivero et al., 2013b). Alterations in the functional role of these components in rat mesenteric artery have been associated with several experimental and pathophysiological conditions including hypertension, a high fat diet intake, ageing and portal hypertension (Marín et al., 2000; Ferrer et al., 2003; Blanco-Rivero et al., 2011a; Sastre et al., 2012a). Additionally, we have previously reported that diabetes alters the function of perivascular neurons in rat mesenteric arteries (Ferrer et al., 2000; del Campo et al., 2011). These findings suggest that perivascular neurons in the mesenteric circulation have an important influence on the development of several kinds of hypertension, such as angiotensin II-salt hypertension (Osborn and Fink, 2010), mild DOCA-salt hypertension (Kandlikar and Fink, 2011) and renovascular hypertension (Koyama et al., 2010).

Taking into account this information, we considered it relevant to investigate whether the development of maternal diabetes during pregnancy could lead to alterations in the perivascular neurons, which could affect vascular tone in the adult offspring of diabetic rats. For this purpose, we analysed the possible functional changes in perivascular innervation in mesenteric arteries from the offspring of diabetic rats, evaluating any alterations in the activity of sympathetic, nitrergic or sensory innervations, as well as the mechanisms involved.

Methods

Ethics statement

All animals were obtained from the Animal Quarters of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid and housed in the animal facility of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (registration number EX-021U) in accordance with guidelines 609/86 of the E.E.C., R.D. 233/88 of the Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación of Spain, and Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the United States National Institute of Health (NIH publication no. 85.23, revised 1985). The experimental protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

Animals

Virgin female Wistar rats were kept in cages with male rats in a 3:1 ratio for mating. Evidence of copulation was confirmed by the presence of sperm in a vaginal smear 24 h after which was considered to be day 1 of gestation. Seven days after the onset of pregnancy, diabetes was induced by a single injection of streptozotocin (50 mg·kg−1, i.p.), as described previously (Wichi et al., 2005; Ramos-Alves et al., 2012a,b,). Control animals received an equal volume of vehicle (citrate buffer). Blood glucose was measured 7 days after injecting either streptozotocin or citrate buffer to confirm whether or not diabetes had been induced; only rats with severe hyperglycaemia above 2 mg·mL−1 were used. During lactation, the offspring were restricted to six animals per rat. This study used only 6-month-old male offspring from diabetic mothers (O-DR) and control offspring (O-CR). Rats were weighed and killed by CO2 inhalation followed by decapitation; the SMA was carefully dissected out, placed in Krebs–Henseleit solution (KHS, in mmol·L−1: NaCl 115, CaCl2 2.5, KCl 4.6, KH2PO4 1.2, MgSO4·7H2O 1.2, NaHCO3 25, glucose 11.1, Na2 EDTA 0.03) at 4°C, cleaned of perivascular fat and connective tissue and divided into 2 mm long segments using a micrometre eyepiece mounted on a Euromex Holland binocular lens (Mataró, Spain). Some samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C. Additionally, some segments were mounted on 100 μm wires in a small vessel myograph to measure internal diameter (1–1.2 mm in diameter; Simonsen et al., 1999). No differences were found between experimental groups.

Glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity

The oral glucose tolerance test was performed according to a standard protocol. After a 10 h fast, a single oral dose (2 g·kg−1 of body weight) of glucose was delivered. Blood glucose was then measured from the tail vein just before and at 30, 60, 90 and 120 min after glucose injection using test strips and reader (ACCU-CHEK®, Roche Diagnostics, Madrid, Spain). After 48 h, animals were subjected to a new 10 h fast for assessment of insulin sensitivity by an insulin tolerance test. For this, regular insulin was administered i.p. at a dose of 1.5 U·kg−1 body weight. Blood glucose was determined before and at 15, 30, 45 and 60 min after insulin administration.

Arterial blood pressure measurement

The animals were anaesthetized with a mixture of ketamine, xylazine and acetylpromazine (64.9, 3.2 and 0.78 mg·kg−1, respectively, i.p.). The right carotid artery was cannulated with a polyethylene catheter (PE-50) filled with heparin-containing saline. After 24 h, mean arterial pressure was measured in conscious animals by a pressure transducer (model MLT844; ADInstruments Pty Ltd, Castle Hill, New South Wales, Australia) and recorded using an interface and software for computer acquisition (ADInstruments Pty Ltd). Heart rate was calculated from the pressure signal recorded by a pressure transducer and connected to a computerized measuring programme (LabChat v7, ADInstruments Pty Ltd).

Serum biochemical parameters

Serum concentrations of total cholesterol, triglycerides and HDL cholesterol were determined using specific quantitative enzyme assays (Vitros Chemistry Products) and measured with a colorimetric spectrophotometer (Vitros Fusion 5.1 FS Chemistry System, Ortho-Clinical). The assays were performed following the manufacturer's instructions. Results are expressed as mg·L−1. Serum concentrations of insulin were analysed using the Rat/Mouse Insulin elisa Kit (EMD Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA). The assay was performed following the manufacturer's instructions. Results are expressed as ng insulin·mL−1.

Vascular reactivity study

The method used for isometric tension recording has been described in full elsewhere (Nielsen and Owman, 1971; Marín and Balfagón, 1998). Briefly, two parallel stainless steel pins were introduced through the lumen of the vascular segment: one was fixed to the bath wall and the other connected to a force transducer (Grass FTO3C, Quincy, MA, USA); this, in turn, was connected to a model 7D Grass polygraph. For EFS experiments, segments were mounted between two platinum electrodes 0.5 cm apart and connected to a stimulator (Grass, model S44) modified to supply the appropriate current strength. Segments were suspended in an organ bath containing 5 mL of KHS at 37°C continuously bubbled with a 95% O2 to 5% CO2 mixture (pH 7.4). Some experiments were performed in endothelium-denuded segments to eliminate the main source of vasoactive substances, including endothelial NO. This avoided possible actions by different drugs on endothelial cells that could have led to a misinterpretation of the results. The endothelium was removed by gently rubbing the luminal surface of the segments with a thin wooden stick. The segments were subjected to a tension of 4.95 mN, which was readjusted every 15 min during a 90 min equilibration period before drug administration. After this, the vessels were exposed to 75 mmol·L−1 KCl to check their functional integrity. Endothelium removal did not alter the contractions elicited by KCl. After a washout period, the presence/absence of vascular endothelium was tested by the ability of 10 μmol·L−1 ACh to relax segments precontracted with 1 μmol·L−1 NA. We consider as endothelium-denuded those arteries that were unable to relax to ACh.

Vasodilator responses to ACh (0.1 nmol·L−1 to 10 mmol·L−1) were obtained in endothelium-intact arteries from all experimental groups. Frequency–response curves to EFS (1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 Hz, a range considered to reproduce physiological situations) were performed in endothelium-intact and endothelium-denuded mesenteric segments from all experimental groups. The parameters used for EFS were 200 mA, 0.3 ms, 1–16 Hz, for 30 s with an interval of 1 min between each stimulus, the time required to recover basal tone. A washout period of at least 1 h was necessary to avoid desensitization between consecutive curves. Two successive frequency–response curves separated by 1 h intervals produced similar contractile responses. To evaluate the neural origin of the EFS-induced contractile response, the nerve impulse propagation blocker, tetrodotoxin (TTX; 0.1 mmol·L−1), was added to the bath 30 min before the second frequency–response curve was obtained.

To determine the participation of sympathetic neurons in the EFS-induced response in endothelium-denuded segments from O-CR and O-DR rats, 1 μmol·L−1 phentolamine, an α-adrenoceptor antagonist, or phentolamine plus 0.1 mmol·L−1 suramin, a non-specific purine receptor antagonist, was added to the bath 30 min before performing the frequency–response curve. Additionally, the vasoconstrictor response to exogenous NA (1 nmol·L−1 to 10 mmol·L−1) was tested in segments from both experimental groups.

To study the possible participation of sensory neurons in the EFS-induced response in endothelium-denuded segments from O-CR and O-DR rats, 0.5 μmol·L−1 CGRP (8–37), a CGRP receptor antagonist, was added to the bath 30 min before performing the second frequency–response curve.

To analyse the participation of NO in the EFS-induced response in endothelium-denuded segments from O-CR and O-DR rats, 0.1 mmol·L−1 Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME), a non-specific inhibitor of NOS, was added to the bath 30 min before performing the second frequency–response curve. The vasodilator response to the NO donor, diethylamine NONOate, (DEA-NO, 0.1 nmol·L−1 to 0.1 mmol·L−1), was determined in NA-precontracted arteries from both experimental groups.

NA and ATP release

Endothelium-denuded segments of rat mesenteric arteries from O-CR and O-DR animals were pre-incubated for 30 min in 5 mL of KHS at 37°C and continuously gassed with a 95% O2 to 5% CO2 mixture (stabilization period). This was followed by two washout periods of 10 min in a bath of 0.4 mL KHS. Then the medium was collected to measure basal neurotransmitter release. Next, the organ bath was refilled and cumulative EFS periods of 30 s at 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 Hz were applied at 1 min intervals. Afterwards, the medium was collected to measure the EFS-induced release. Mesenteric segments were weighed in order to normalize the results. NA and ATP release were measured using Noradrenaline Research EIA (Labor Diagnostica Nord, Gmbh and Co., KG, Nordhon, Germany) or an ATP colorimetric/fluorometric assay kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The assays were performed following the manufacturer's instructions. Results are expressed as ng NA·mL−1 mg−1 tissue, or nmol ATP·mL−1 mg−1 tissue.

NO release

NO release was measured using fluorescence emitted by the fluorescent probe 4,5-diaminofluorescein (DAF-2) as previously described (Blanco-Rivero et al., 2011a). Endothelium-denuded mesenteric arteries from O-CR and O-DR rats were subjected to a 60 min equilibration period in HEPES buffer [in mmol·L−1: NaCl 119; HEPES 20; CaCl2 1.2; KCl 4.6; MgSO4 1; KH2PO4 0.4; NaHCO3 5; glucose 5.5; Na2HPO4 0.15; (pH 7.4)] at 37°C. Arteries were incubated with 2 μmol·L−1 DAF-2 for 30 min. The medium was collected to measure basal NO release. Once the organ bath was refilled, cumulative EFS periods of 30 s at 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 Hz were applied at 1 min intervals. Afterwards, the medium was collected to measure EFS-induced NO release. The fluorescence of the medium was measured at room temperature (RT) using a spectrofluorometer (LS50 PerkinElmer Instruments, FL WINLAB Software, Waltham, MA, USA) with excitation wavelength set at 492 nm and emission wavelength at 515 nm.

The EFS-induced NO release was calculated by subtracting basal NO release from that evoked by EFS. Also, blank samples were collected in the same way from segment-free medium in order to subtract background emission. Some assays were performed in the presence of 0.1 mmol·L−1 TTX or 1 mmol·L−1 1400 W, the specific iNOS inhibitor. The amount of NO released was expressed as arbitrary units·mg−1 tissue.

Superoxide anion production

Superoxide anion levels were measured using lucigenin chemiluminescence (Blanco-Rivero et al., 2011b). Endothelium-denuded mesenteric segments from O-CR and O-DR animals were rinsed in KHS for 30 min, equilibrated for 30 min in HEPES buffer at 37°C, transferred to test tubes that contained 1 mL HEPES buffer (pH 7.4) with lucigenin (5 μmol·L−1) and then kept at 37°C. The luminometer was set to report arbitrary units of emitted light; repeated measurements were collected for 5 min at 10 s intervals and averaged. 4,5-Dihydroxy-1,3-benzene-disulfonic acid ‘Tiron’ (10 mmol·L−1), a cell-permeant, non-enzymatic superoxide anion scavenger, was added to quench the superoxide anion-dependent chemiluminescence. Also, blank samples were collected in the same way without mesenteric segments to subtract background emission.

Immunofluorescence staining of nerve fibres

SMA was immediately placed in cold PBS (in g·L−1): NaCl 8, Na2HPO4 1.15, KCl 0.2, KH2PO4 0.2 (pH 7.2). The whole vessel was fixed (4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, 50 min, RT). After three 10 min PBS washing cycles, non-specific binding was blocked by incubating the samples for 1 h in 5% bovine albumin PBS + 0.3% Tween 20 (PBS-T). The vessels were cut into segments and incubated with primary antibodies: rabbit polyclonal anti-dopamine β-hydroxylase (Sigma 1:200) or rabbit polyclonal anti-neuronal NOS (nNOS; Abcam 1:100) diluted in 2% bovine albumin PBS-T. Thereafter, tissues were stained with the nuclear dye DAPI (1:500 dilution, 15 min, RT) and, after two PBS-T washing cycles, incubation with Alexa 647 anti-rabbit fluorescent secondary antibodies (1:200 dilution, 1 h, RT) was carried out. Negative controls were performed by omitting primary antibodies. After four PBS-T washing cycles, tissue preparations were mounted in a single well filled with antifading agent (Citifluor AF-2, Citifluor Ltd).

Preparations were visualized with a Leica SP5 laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) system (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) fitted with an inverted microscope (×40 oil immersion lens). Stacks of 2 μm thick serial optical images were captured from the entire adventitial layer, which was identified by the shape and orientation of the nuclei (Arribas et al., 1997). Image acquisition was always performed under the same laser power, brightness and contrast conditions.

Two to three different regions were scanned along each mesenteric artery, and the resulting images were reconstructed separately with ImageJ 1.48c software (National Institutes of Health) to generate extended focus images. After obtaining the 0 value for the background, the area fraction parameter was set to determine the areas occupied by fibres defined as percentage of pixels with non-zero. Data are presented as percentage of area occupied by nerve fibres.

nNOs and phospho-nNOS (P-nNOS) expression

Western blot analysis of nNOS and P-nNOS expression was performed in endothelium-denuded mesenteric segments from O-CR and O-DR rats as described previously (Blanco-Rivero et al., 2011a,b,). For these experiments, we used mouse monoclonal nNOS antibody (1:1000, Transduction Laboratories), rabbit polyclonal P-nNOS antibody (1:2000, Abcam) and monoclonal anti-β-actin-peroxidase antibody (1:50 000, Sigma-Aldrich, Madrid, Spain). Rat brain homogenates were used as positive control.

Drugs used

L-Noradrenaline hydrochloride, ACh chloride, diethylamine NONOate diethylammonium salt, CGRP (8–37), TTX, L-NAME hydrochloride, 1400 W, phentolamine, suramin sodium salt, lucigenin, tiron and DAF-2 (Sigma-Aldrich) were used. Stock solutions (10 mmol·L−1) of drugs were made in distilled water, except for NA, which was dissolved in a NaCl (0.9%) ascorbic acid (0.01% w/v) solution. These solutions were kept at −20°C and appropriate dilutions were made in KHS on the day of the experiment.

Data analysis

The responses elicited by EFS and NA were expressed as a percentage of the initial contraction elicited by 75 mmol·L−1 KCl for comparison between O-CR and O-DR rats. The relaxation induced by ACh or DEA-NO was expressed as a percentage of the initial contraction elicited by NA (control: 10.36 ± 0.85 mg; O-DR: 10.81 ± 0.55 mg; P > 0.05). For concentration–response curves, non-linear regression was performed. Results are given as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was carried out by comparing the curve obtained in the presence of different substances with the previous or control curve by means of repeated measure anova followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test. Some results are expressed as differences in AUC (dAUC). AUCs were calculated from the individual frequency–response plots. For dAUC, NO, NA and ATP release experiments, the statistical analysis was performed using one-way anova followed by Newman–Keuls post hoc test. Glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, arterial blood pressure, heart rate, results of general characteristics and immunofluorescence staining were analysed using t-test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Dams injected with streptozotocin had severe hyperglycaemia on gestational days 14 (control 829 ± 31 vs. diabetic 4572 ± 337 mg·L−1, t-test: P < 0.05) and 21 (control 872 ± 26 vs. diabetic 4806 ± 394 mg·L−1, t-test: P < 0.05) compared with control dams. Blood glucose levels were similar in O-CR an O-DR in 3-month-old (O-CR 764 ± 37 vs. O-DR 743 ± 28 mg·L−1, t-test: P > 0.05) and 6-month-old animals (O-CR 788 ± 62 vs. O-DR 792 ± 78 mg·L−1, t-test: P > 0.05).

The oral glucose tolerance test revealed that blood glucose levels were higher in O-DR at 30 min compared with O-CR (results not shown) and remained increased until 120 min (O-CR, 1133 ± 97 vs. O-DR, 1568 ± 34 mg·L−1, t-test: P < 0.05). Results from the insulin sensitivity test demonstrated significant insulin resistance in the O-DR as they presented a higher blood glucose level from 30 to 60 min after an insulin injection (blood glucose 60 min after the insulin injection: O-CR, 230 ± 15 vs. O-DR, 612 ± 97 mg·L−1; t-test: P < 0.05).

O-DR had a higher blood pressure than O-CR (mean arterial pressure: O-CR: 119 ± 6.5 vs. O-DR: 137 ± 0.5 mmHg; t-test: P < 0.05). The heart rate was similar in both the O-DR and the O-CR (O-CR: 392 ± 21 vs. O-DR: 397 ± 32 bpm; t-test: P > 0.05).

Body weight was decreased in the O-DR group (Table 1). Serum insulin, total cholesterol, HDL and triglycerides were similar in both experimental groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Body weight and serum biochemical parameters

| O-CR | O-DR | |

|---|---|---|

| Body weight (mg) | 438.8 ± 17.16 | 381.3 ± 8.25* |

| Total cholesterol (mg·mL−1) | 0.80 ± 0.07 | 0.73 ± 0.04 |

| HDL (mg·mL−1) | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.02 |

| Triglycerides (mg·mL−1) | 1.32 ± 0.12 | 1.27 ± 0.17 |

| Insulin (ng·mL−1) | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 4.8 ± 0.1 |

At 6 months, body weight was measured, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides and insulin in O-CR and O-DR animals. Data shown are means ± SEM.

P < 0.05 versus O-CR. n = 8 animals per group.

Vasomotor response to KCl

In endothelium-intact mesenteric segments, the vasoconstrictor response to 75 mmol·L−1 KCl was similar in both experimental groups (O-CR: 13.8 ± 1.1 mN; O-DR: 15.53 ± 1.18 mN; P > 0.05). Endothelium removal did not alter KCl-induced vasoconstriction (O-CR: 15.21 ± 1.5 mN; O-DR: 14.59 ± 10.9 mN; P > 0.05).

Vasodilator response to ACh

ACh-induced cumulative concentration- and endothelium-dependent relaxations in NA-contracted arteries (O-CR: 10.26 ± 0.84 mN; O-DR: 10.71 ± 0.55 mN; P > 0.05) from both the O-CR and O-DR groups. However, the exposure to maternal diabetes decreased this vasodilator response as compared with the response in the O-CR group (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) ACh-induced vasodilatation in endothelium-intact mesenteric segments from O-CR and O-DR rats. Results (mean ± SEM) are expressed as a percentage of the previous tone elicited by exogenous NA. anova *P < 0.05 O-CR versus O-DR. n = 12 animals in each group. (B) EFS-induced vasoconstriction in endothelium-intact mesenteric segments from O-CR and O-DR rats. Results (mean ± SEM) are expressed as a percentage of the initial contraction elicited by KCl. *P < 0.05 versus O-CR animals at each frequency (Bonferroni test). n = 12 animals per group. Effect of endothelium removal on the vasoconstrictor response to EFS in mesenteric segments from O-CR (C) and O-DR (D) animals. Results (mean ± SEM) are expressed as a percentage of the initial contraction elicited by KCl. anova *P < 0.05 endothelium-intact versus endothelium-denuded arteries. n = 12 animals per group. (E) dAUC in the absence or presence of endothelium.

Vascular responses to EFS

The application of EFS induced a frequency-dependent contractile response in endothelium-intact mesenteric segments from both the O-CR and O-DR groups. This vasoconstriction was greater in segments from O-DR rats compared with O-CR animals (Figure 1B). Endothelium removal increased EFS-induced contractile response similarly in segments from all experimental groups (Figure 1C and D). EFS-induced contractions were practically abolished in segments from all experimental groups by the neurotoxin TTX (0.1 mmol·L−1), indicating the neuronal origin of the factors inducing this response (Table 2).

Table 2.

Effect of pre-incubation with TTX (0.1 μmol·L−1) on the frequency–contraction curves performed in mesenteric segments from O-CR and O-DR

| 1 Hz | 2 Hz | 4 Hz | 8 Hz | 16 Hz | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O-CR | 8.74 ± 2.9 | 25.45 ± 4.1 | 41.44 ± 5.7 | 58.49 ± 6.9 | 81.92 ± 8.5 |

| TTX | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.4 ± 0.06 | 0.7 ± 0.1 |

| O-DR | 21.61 ± 6.8 | 37.92 ± 6.4 | 35.53 ± 6.9 | 74.05 ± 7.1 | 100.49 ± 8.5 |

| TTX | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.5 ± 0.04 | 0.9 ± 0.02 |

Results (means ± SEM) are expressed as percentages of the response elicited by 75 mM KCl; 0, no contraction was detected. n = 7 animals for each group.

Participation of the sympathetic component of mesenteric vascular neurons

Pre-incubation with the α-adrenoceptor antagonist phentolamine (1 μmol·L−1) decreased the vasoconstrictor response induced by EFS in endothelium-denuded segments from both experimental groups (Figure 2A and B). This decrease was greater in mesenteric segments from O-DR animals (Figure 2C). NA-induced vasoconstriction was similar in both experimental groups (Figure 3A). EFS-induced NA release was higher in mesenteric segments from the O-DR group than in segments from O-CR animals (Figure 3B). A phentolamine-resistant contractile response remained, which was greater in mesenteric segments from O-DR animals (Figure 2D). Pre-incubation with phentolamine plus 0.1 mmol·L−1 suramin, a non-specific P2 purine receptor antagonist, decreased the EFS-induced contraction only in segments from the O-DR group (Figure 2A and B). In line with this, EFS-induced ATP release was increased in segments from O-DR animals (Figure 3C).

Figure 2.

Effect of pre-incubation with 1 μmol·L−1 phentolamine or phentolamine plus 0.1 mmol·L−1 suramin on the vasoconstrictor response induced by EFS in endothelium-denuded mesenteric segments from O-CR (A) and O-DR animals (B). Results (mean ± SEM) are expressed as a percentage of the initial contraction elicited by KCl. anova P < 0.05 versus conditions without phentolamine or suramin in both experimental groups. *P < 0.05 versus conditions without phentolamine at each frequency (Bonferroni test). #P < 0.05 conditions phentolamine plus suramin versus conditions without suramin at each frequency (Bonferroni test). n = 8 animals each group. (C) dAUC in the absence or presence of 1 μmol·L−1 phentolamine. dAUC values are expressed as arbitrary units. (D) Representation of the vasoconstriction remaining after pre-incubation with 1 μmol·L−1 phentolamine, expressed as AUC (in arbitrary units).

Figure 3.

(A) Vasoconstrictor response to NA in segments from O-CR and O-DR. Results (mean ± SEM) are expressed as a percentage of the initial contraction elicited by KCl. n = 8 animals each group. EFS-induced NA (B) and ATP (C) release in mesenteric segments from O-CR and O-DR animals. Results (mean ± SEM) are expressed as ng NA·mL−1 mg−1 tissue or nmol ATP·mL−1 mg−1 tissue. n = 8 animals per group.

LSCM allowed visualization of the sympathetic nerve network in the adventitial layer of mesenteric arteries through reconstruction of stacks of images with dopamine β-hydroxylase immunoreactivity (Figure 4, upper panel). Quantification of nerve fibre density confirmed that there were no differences between either experimental groups (Figure 4, lower panel).

Figure 4.

Dopamine β-hydroxylase immunoreactivity in the adventitia of mesenteric arteries from O-CR and O-DR animals (upper panel). Tissues were stained with primary monoclonal dopamine β-hydroxylase (DβH) antibody and a species-specific secondary Alexa 647 antibody. Bar = 75 μm. All images are reconstructions from 10 serial optical sections obtained by LSCM. Lower panel shows percentage of area occupied by sympathetic nerve fibres. n = 6 animals per group. (For a better visualization, brightness and contrast were modified equally in both experimental groups using ImageJ software.)

Participation of the sensory component in vascular responses to EFS

Pre-incubation with the CGRP receptor antagonist CGRP (8–37) (0.5 μmol·L−1) did not alter the EFS-induced contraction in any experimental group (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effect of pre-incubation with 0.5 μmol·L−1 CGRP (8–37) on the vasoconstrictor response induced by EFS in mesenteric segments from O-CR (A) and O-DR (B) animals. Results (mean ± SEM) are expressed as a percentage of the previous contraction elicited by KCl. n = 8 animals each group.

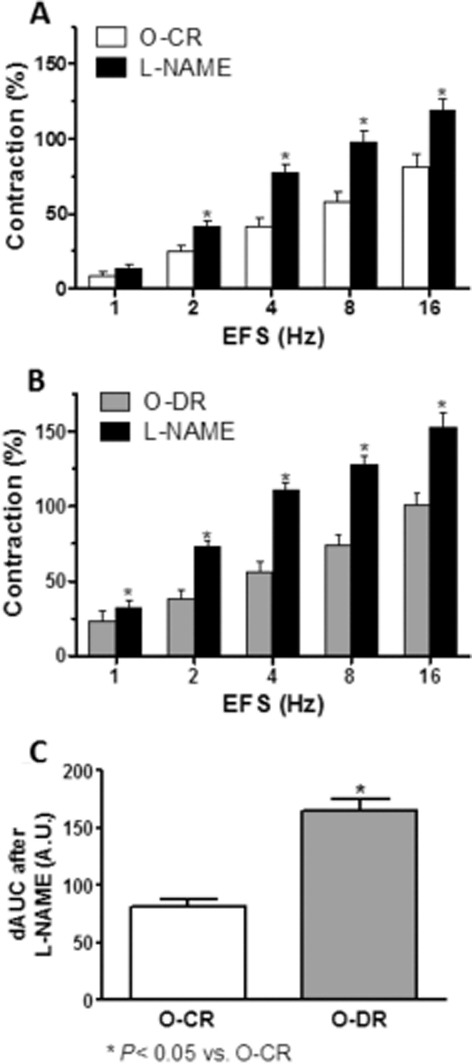

Participation of the nitrergic component in vascular responses to EFS

Pre-incubation with non-specific NOS inhibitor L-NAME (0.1 mmol·L−1) significantly increased the EFS–contractile response in endothelium-denuded segments from both experimental groups (Figure 6A and B). This increase was greater in segments from O-DR animals (Figure 6C). EFS induced NO release in segments from both groups. This release was higher in O-DR mesenteric segments (Figure 7A). TTX practically abolished EFS-induced NO release, whereas 1400 W did not modify it in either experimental group (Figure 7A). The expression of nNOS was not modified, whereas P-nNOS expression was increased in homogenates from O-DR arteries compared with that in O-CR segment homogenates (Figure 7B). Maternal gestational diabetes did not alter either the vasodilator response to DEA-NO (NA pre-contraction: control: 10.33 ± 0.74 mN; O-DR: 10.46 ± 0.65 mN; P > 0.05) or the superoxide anion release in the offspring (Figure 7C and D).

Figure 6.

Effect of pre-incubation with 0.1 mmol·L−1 L-NAME on the vasoconstrictor response induced by EFS in mesenteric segments from O-CR (A) and O-DR (B) rats. Results are expressed as a percentage of the previous contraction elicited by KCl. anova P < 0.05 versus conditions without phentolamine or suramin in both experimental groups. *P < 0.05 versus conditions without L-NAME for each frequency (Bonferroni test). n = 8 animals each group. (C) dAUC in the absence or presence of 0.1 mmol·L−1 L-NAME. dAUC values are expressed as arbitrary units. *P < 0.05.

Figure 7.

(A) EFS-induced NO release in segments from O-CR and O-DR rats. Results (mean ± SEM) are expressed as arbitrary (A.U.)·mg−1 tissue; n = 8 animals per group. (B) Effect of exposure to maternal hyperglycaemia on nNOS and P-nNOS expression. The blot is representative of eight separate segments from each group. Rat brain homogenates were used as a positive control. Lower panel shows relationship between P-nNOS or nNOS expression and β-actin. Results (mean ± SEM) are expressed as ratio of the signal obtained for each protein and the signal obtained for β-actin. (C) Vasodilator response to NO donor DEA-NO in segments from O-CR and O-DR rats. Results (mean ± SEM) are expressed as a percentage of the previous tone elicited by exogenous NA. n = 8 animals each group. (D) Superoxide anion release in mesenteric segments from O-CR and O-DR rats. Results (mean ± SEM) are expressed as chemiluminescence U·min−1 mg tissue. n = 8 animals each group.

LSCM allowed visualization of the nitrergic nerve network in the adventitial layer of mesenteric arteries through reconstruction of stacks of images with nNOS immunoreactivity (Figure 8, upper panel). Quantification of nerve fibre density confirmed the absence of differences between both experimental groups (Figure 8, lower panel).

Figure 8.

nNOS immunoreactivity in the adventitia of mesenteric arteries from O-CR and O-DR animals (upper panel). Tissues were stained with primary polyclonal nNOS antibody and a species-specific secondary Alexa 647 antibody. Bar = 75 μm. All images are reconstructions from 10 serial optical sections obtained by LSCM. Lower panel shows percentage of area occupied by nitrergic nerve fibres. n = 6 animals per group.

Discussion

This study provides the first evidence that maternal diabetes alters the participation of different kinds of perivascular mesenteric neurons in adult offspring. The results presented here demonstrate that in utero exposure to maternal hyperglycaemia increases EFS-induced vasoconstriction in adulthood. This increase is endothelium independent, and is the net effect of an increased participation of sympathetic neurons, through increased release of NA and ATP, and an augmented activity of nitrergic neurons, associated with increased NO production.

The body weight of rats in the O-DR group was significantly lower compared with those in the O-CR group. This result agrees with previous reports showing that maternal diabetes induced by STZ produces a decrease in offspring weight (Grill et al., 1991; Holemans et al., 1999; Porto et al., 2010; Ramos-Alves et al., 2012a) that has been associated with reduced protein synthesis (Canavan and Goldspink, 1988). However, several studies have found no changes or even increases in the body weight of the offspring of rats subjected to this experimental procedure (Rocha et al., 2005; Nehiri et al., 2008). This apparent contradiction may be due to differences in the severity of maternal hyperglycaemia during pregnancy, as previously suggested by Segar et al. (2009).

Intrauterine exposure to maternal hyperglycaemia is a significant risk factor for the development of metabolic and cardiovascular disorders in the offspring. In the current study, 6-month-old male offspring of diabetic mothers exhibited glucose intolerance, insulin resistance and an elevated blood pressure, as we (Ramos-Alves et al., 2012a,b,) and others have reported previously (Simeoni and Barker, 2009). Glucose and insulin levels and lipid profile were similar in both experimental groups, in agreement with Blondeau et al. (2011). The mechanisms of hyperglycaemia-programmed hypertension are complex and involve renal, neural and vascular factors (Rocha et al., 2005; Wichi et al., 2005; Nehiri et al., 2008; Segar et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2010). The analysis of the vasoconstrictor response induced by EFS in endothelium-intact segments showed a frequency-dependent contraction in segments from both experimental groups. This vasoconstriction was greater in mesenteric segments from O-DR than O-CR animals. This increase could not be attributed to changes in the intrinsic contractile machinery as a similar vasoconstrictor response to KCl was obtained in both experimental groups. The endothelium has been reported to affect the response to several substances including neurotransmitters such as NA (Vanhoutte and Houston, 1985; Li and Duckles, 1992). Because we observed that the relaxation to ACh was impaired in O-DR compared with O-CR rats, as we and other groups had previously reported (Holemans et al., 1999; Rocha et al., 2005; Segar et al., 2009; Ramos-Alves et al., 2012a), we expected differences in the influence of endothelium on the vasoconstrictor response to EFS in segments from the two experimental groups. However, endothelium removal increased this vasoconstriction to the same extent in both experimental groups. These results indicate that endothelial dysfunction does not influence the EFS-induced response in diabetic offspring, similar to reports on this artery in rats fed a high fat diet (Sastre et al., 2015). One possible explanation could be that the vasoconstrictor response to α-adrenoceptor activation has been reported as maintained in the absence of endothelium (Xavier et al., 2004a) independently of the modifications of the vasodilator response to ACh. In endothelium-denuded segments, the EFS-induced vasoconstriction was almost abolished in the presence of the neurotoxin TTX, indicating a neuronal origin for this response. The remaining contractile response to high-frequency stimulation could be explained by a direct action potential produced in smooth muscle cells elicited by EFS. For that reason, we performed the following experiments in endothelium-denuded mesenteric segments.

Sympathetic function is essential for blood pressure regulation, and sympathetic hyperactivity has an important role in the development of hypertension (Lohmeier, 2001). Sympathetic neurons mainly release NA and ATP when electrically stimulated. The activity of these neurons is altered in different physiological and pathological situations (Sastre et al., 2010). Increased sympathetic activity has been reported in O-DR (Young and Morrison, 1998; Iellamo et al., 2006; de Almeida Chaves Rodrigues et al., 2013). This effect could be associated with an increased NA release and/or vasoconstrictor response to NA. To the best of our knowledge, although increased NA release in different tissues has been suggested (Morriss, 1984; Iellamo et al., 2006), as well as increases or no modifications in NA vasoconstriction (Holemans et al., 1999; Ramos-Alves et al., 2012b), an integrated study of both mechanisms has not yet been performed in arteries. Thus, our next objective was to determine possible differences in the function of sympathetic neurons between the O-CR and O-DR experimental groups. The fact that the α-adrenoceptor antagonist phentolamine significantly diminished the vasoconstrictor response to EFS in mesenteric segments from both experimental groups confirms that this response would be mediated mainly by the release of NA from sympathetic nerve terminals. Moreover, our study showed that phentolamine produced a more marked decrease in EFS vasoconstriction in segments from OD-R rats than O-CR animals, confirming an increased involvement of sympathetic neurons in this experimental group. This different participation can be produced by modifications in NA vasoconstrictor response and/or release. Exogenous NA-induced vasoconstriction was similar in both experimental groups, like the vasoconstriction described in endothelium-denuded mesenteric resistance arteries (Ramos-Alves et al., 2012b), whereas EFS-induced NA release was higher in segments from O-DR animals, confirming that the increased adrenergic activity in O-DR is associated with increased NA release.

It should also be mentioned that both groups showed a substantial phentolamine-resistant contractile response. This remaining vasoconstriction was higher in segments from O-DR animals. We have previously observed that ATP released from sympathetic nerves caused vasoconstriction in this vascular bed (Blanco-Rivero et al., 2011a; 2013a,b,). Based on this information, we analysed EFS-induced contraction after simultaneous pre-incubation with phentolamine plus the non-specific P2 purine receptor antagonist suramin. In these conditions, the contractile response to EFS was reduced only in segments from the O-DR group, indicating that ATP contributes to this response. In line with these results, EFS-induced ATP release was higher in mesenteric segments from O-DR than O-CR rats, as previously described (Rummery et al., 2007; Sousa et al., 2014), suggesting an increased contribution of ATP in neurovascular transmission in hypertension. Altogether, these observations indicate that the increased participation of sympathetic neurons observed in mesenteric segments from O-DR animals is due to an increase in NA and ATP release from nerve terminals. Because this increased release of sympathetic neurotransmitters could be due to an increase in nerve fibre density, our next objective was to determine possible differences in the sympathetic nerve density. Results obtained by immunofluorescence staining for dopamine β-hydroxylase showed no differences between either experimental group, ruling out an increase in sympathetic nerve density and suggest that the augmented release of NA and ATP could be related to an increase in enzymatic activity involved in the synthesis of both neurotransmitters. However, neurotransmitter release by sympathetic neurons is mediated by several subtypes of adrenoceptor (Sanchez-Merino et al., 1990; Arribas et al., 1991; Enero et al., 1997; Kanagy, 2005), so some type of presynaptic dysfunction cannot be ruled out.

We have previously reported that CGRP released from sensory neurons does not participate in the vasoconstrictor response to EFS (Blanco-Rivero et al., 2011a,c,), although the level of CGRP is increased in several pathological situations, such as hypertension and diabetes (Blanco-Rivero et al., 2011c; del Campo et al., 2011; Sastre et al., 2012a). Pre-incubation with the CGRP receptor antagonist CGRP (8–37) did not modify EFS-induced vasoconstriction in either O-CR or O-DR mesenteric segments. This observation led us to conclude that maternal diabetes did not alter the activity of sensory neurons in this vascular bed in adulthood.

A decrease in endothelial NO release has been reported to participate in the development of hypertension (Wu et al., 1997; Bernatova, 2014). Similar results have been observed in rat aorta and mesenteric resistance arteries from offspring of diabetic rats (Holemans et al., 1999; Cavanal Mde et al., 2007; Ramos-Alves et al., 2012a). However, there are no data studying the possible role of neuronal NO in this model. The fact that previous studies have reported increases in endothelial NO release due to ATP-induced activation of P2X4 and P2Y receptors and augmented NOS activity due to endothelial α2 adrenoceptor activation by NA in rat mesenteric arteries (Boric et al., 1999; Buvinic et al., 2002; Codocedo et al., 2013), as well as our earlier report of increased neuronal NO in both diabetes and hypertension (Ferrer et al., 2000; 2003,; Marín et al., 2000; del Campo et al., 2011), make it necessary to evaluate whether a hyperglycaemic environment intra utero could also affect the synthesis of NO from nitrergic neurons. In our experimental conditions, the involvement of neuronal NO in the EFS-induced response was demonstrated by the fact that pre-incubation with the non-specific NOS inhibitor L-NAME increased the response to EFS in segments from both experimental groups. The greater effect of L-NAME observed in segments from O-DR rats suggests an increased role for neuronal NO in this experimental group, possibly related to increases in nitric NO and/or increases in smooth muscle sensitivity to NO.

In our experimental conditions, we observed an increased EFS-induced NO release in mesenteric segments from O-DR animals. The fact that pre-incubation with TTX abolished EFS-induced NO release in segments from both groups of rats, and that pre-incubation with the specific iNOS inhibitor 1400 W did not alter NO release confirms the neural origin of NO and rules out the involvement of inducible NOS. We have previously demonstrated that NO released from nerve endings in this vascular bed is synthesized through nNOS (Blanco-Rivero et al., 2011a,b,; 2013a,b,). The increase in neuronal NO could be due to an increase in nitrergic nerve fibre density or an increase in the enzymatic activity of nNOS. Thus, our next objective was to determine possible differences in nitrergic nerve density. Immunofluorescence staining for nNOS showed no differences between experimental groups, suggesting that the differences in NO release could be due to modifications in the expression and/or activation of nNOS. We found that nNOS protein expression was similar in both experimental groups, whereas the active form P-nNOS was increased in O-DR rats, indicating that increased nNOS activity is responsible for the increase in NO release observed in O-DR mesenteric arteries. These results contrast with observations in endothelium-intact arteries (Holemans et al., 1999; Rocha et al., 2005; Segar et al., 2009; Porto et al., 2010), where the NO release from eNOS was decreased. Similar differences in this vascular bed have been demonstrated previously in several pathological situations (Wu et al., 1997; Ferrer et al., 2000; 2003,; Favero et al., 2014).

Several observations indicate that diabetic pregnant rats and their offspring are exposed to increased oxidative stress induced by the inadequate production of free radical scavengers (Horal et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005; Katkhuda et al., 2012). Thus, the involvement of reactive oxidative species in the vascular response to NO cannot be ruled out as these species could alter the metabolism and consequently affect neuronal NO bioavailability. Superoxide anion production was similar in both experimental groups, in contrast to findings from previous studies (Horal et al., 2004; Li et al., 2005; Katkhuda et al., 2012). These differences can be attributed to the different tissues analysed as well as to the method of inducing maternal diabetes. As was expected from the earlier results, the vasodilator response to the NO donor DEA-NO was similar in segments from both experimental groups, and similar to responses in aorta and mesenteric resistance arteries (Holemans et al., 1999; Katkhuda et al., 2012; Ramos-Alves et al., 2012a). Altogether, these results confirm that the increased activity of the nitrergic neurons is due to increased neuronal NO release and not to changes in the vasodilator response and/or metabolism of neuronal NO.

A reciprocal interaction between sympathetic and nitrergic neurons has been demonstrated in several vascular beds (Lee, 2002; Hatanaka et al., 2006; Koyama et al., 2010). However, in SMA, we have demonstrated an increase in nitrergic activity with no change (Xavier et al., 2004b), a decrease (Sastre et al., 2012a,b,) or increase (Ferrer et al., 2000; 2003,; Marín et al., 2000; del Campo et al., 2011) in adrenergic activity, as in the current study. These observations indicate that modifications in the activity of adrenergic and nitrergic neurons in OD-R are independent and lead us to consider them as primary changes.

Based on previous studies, various hypotheses can be raised about the mechanism/s involved in these effects. During pregnancy, maternal high blood glucose levels stimulate the fetal pancreas to produce high insulin levels (Dabelea, 2007). Hyperinsulinaemia may cause sympathetic overactivation due its effects on the CNS (Scherrer and Sartori, 1997). In the offspring of diabetic rats, a decrease in the mean area of neuronal nuclei and neuronal cytoplasm has been demonstrated in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus, paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus and arcuate nucleus (Plagemann et al., 1999). These changes were accompanied by an increased number of neurons expressing tyrosine hydroxylase in the arcuate nucleus. It has been proposed that this increase in tyrosine hydroxylase-expressing neurons might activate and overstimulate the differentiation of hypothalamic catecholaminergic systems due to hyperinsulinism. Previous reports have demonstrated that hyperinsulinaemia may also increase the phosphorylation of nNOS (Chiang et al., 2009; Fioramonti et al., 2010; Hinchee-Rodriguez et al., 2013) and thereby increase neuronal NO release in the offspring of diabetic dams. Additionally, fetal leptin levels are also raised by maternal hyperglycaemia, which may contribute to central leptin resistance and hypothalamic dysfunction (Steculorum and Bouret, 2011) in the offspring of diabetic rats. Thus, it is possible to postulate that hormonal changes produced by hyperglycaemia during fetal life induce changes in neuronal activity/development that persist to some extent into adult life, as observed in the current study.

In conclusion, maternal diabetes increases the contractile response to EFS in SMA of their adult offspring. This effect is endothelium-independent and is the net result of increased levels of sympathetic vasoconstrictors NA and ATP along with an augmented release of neuronal NO, whereas the activity of sensory neurons is unaltered. This mechanism could be involved in the development of hypertension in the adult offspring of diabetic mothers, reinforcing the concept of fetal programming of chronic diseases.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (SAF2012-38530) and Fundación MAPFRE. E. S. received a FPI-UAM fellowship. D. B. Q. received a Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Brazil) fellowship. F. E. X. is a recipient of research fellowships from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Brazil).

Glossary

- DAF-2

4, 5-diaminofluorescein

- DEA-NO

diethylamine nonoate diammonium salt

- EFS

electrical field stimulation

- O-CR

control offspring

- O-DR

diabetic offspring

- SMA

superior mesenteric artery

Author contributions

D. B. Q., F. E. X., J. B.-R. and G. B. conceived and designed the experiments. D. B. Q., E. S., L. C. and M. C. performed the experiments. D. B. Q., E. S., L. C., M. C. and J. B.-R. analysed the data. F. E. X., J. B.-R. and G. B. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. D. B. Q., E. S., F. E. X., G. B. and J. B.-R. wrote the manuscript. D. B. Q. and E. S. contributed equally to the study and should be considered joint first authors.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: G protein-coupled receptors. Br J Pharmacol. 2013a;170:1459–1581. doi: 10.1111/bph.12445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: ligand-gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2013b;170:1582–1606. doi: 10.1111/bph.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14: enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2013c;170:1797–1867. doi: 10.1111/bph.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribas S, Galvan R, Ferrer M, Herguido MJ, Marin J, Balfagón G. Characterization of the subtype of presynaptic alpha 2-adrenoceptors modulating noradrenaline release in cat and bovine cerebral arteries. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1991;43:855–859. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1991.tb03194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribas SM, Hillier C, González C, McGrory S, Dominiczak AF, McGrath JC. Cellular aspects of vascular remodeling in hypertension revealed by confocal microscopy. Hypertension. 1997;30:1455–1464. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.6.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ. The developmental origins of adult disease. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23:588–595. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2004.10719428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernatova I. Endothelial dysfunction in experimental models of arterial hypertension: cause or consequence? Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:598271. doi: 10.1155/2014/598271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Rivero J, de las Heras N, Martín-Fernández B, Cachofeiro V, Lahera V, Balfagón G. Rosuvastatin restored adrenergic and nitrergic function in mesenteric arteries from obese rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2011a;162:271–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01030.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Rivero J, Furieri LB, Vassallo DV, Salaices M, Balfagón G. Chronic HgCl(2) treatment increases vasoconstriction induced by electrical field stimulation: role of adrenergic and nitrergic innervation. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011b;121:331–341. doi: 10.1042/CS20110072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Rivero J, Márquez-Rodas I, Sastre E, Cogolludo A, Pérez-Vizcaíno F, del Campo L, et al. Cirrhosis decreases vasoconstrictor response to electrical field stimulation in rat mesenteric artery: role of calcitonin gene-related peptide. Exp Physiol. 2011c;96:275–286. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2010.055822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Rivero J, Roque FR, Sastre E, Caracuel L, Couto GK, Avendaño MS, et al. Aerobic exercise training increases neuronal nitric oxide release and bioavailability and decreases noradrenaline release in mesenteric artery from spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2013a;31:916–926. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835f749c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Rivero J, Sastre E, Caracuel L, Granado M, Balfagón G. Breast feeding increases vasoconstriction induced by electrical field stimulation in rat mesenteric artery. Role of neuronal nitric oxide and ATP. PLoS ONE. 2013b;8:e53802. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau B, Joly B, Perret C, Prince S, Bruneval P, Lelièvre-Pégorier M, et al. Exposure in utero to maternal diabetes leads to glucose intolerance and high blood pressure with no major effects on lipid metabolism. Diabetes Metab. 2011;37:245–251. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boric MP, Figueroa XF, Donoso MV, Paredes A, Poblete I, Huidobro-Toro JP. Rise in endothelium-derived NO after stimulation of rat perivascular sympathetic mesenteric nerves. Am J Physiol. 1999;277(3 Pt 2):H1027–H1035. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.3.H1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buvinic S, Briones R, Huidobro-Toro JP. P2Y(1) and P2Y(2) receptors are coupled to the NO/cGMP pathway to vasodilate the rat arterial mesenteric bed. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136:847–856. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canavan JP, Goldspink DF. Maternal diabetes in rats. II. Effects on fetal and protein turnover. Diabetes. 1988;37:1671–1677. doi: 10.2337/diab.37.12.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanal Mde F, Gomes GN, Forti AL, Rocha SO, Franco Mdo C, Fortes ZB, et al. The influence of L-arginine on blood pressure, vascular nitric oxide and renal morphometry in the offspring from diabetic mothers. Pediatr Res. 2007;62:145–150. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318098722e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Chenier I, Tran S, Scotcher M, Chang SY, Zhang SL. Maternal diabetes programs hypertension and kidney injury in offspring. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:1319–1329. doi: 10.1007/s00467-010-1506-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang HT, Cheng WH, Lu PJ, Huang HN, Lo WC, Tseng YC, et al. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase activation is involved in insulin-mediated cardiovascular effects in the nucleus tractus solitarii of rats. Neuroscience. 2009;159:727–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codocedo JF, Godoy JA, Poblete MI, Inestrosa NC, Huidobro-Toro JP. ATP induces NO production in hippocampal neurons by P2X(7) receptor activation independent of glutamate signaling. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e57626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida Chaves Rodrigues AF, de Lima IL, Bergamaschi CT, Campos RR, Hirata AE, Schoorlemmer GH, et al. Increased renal sympathetic nerve activity leads to hypertension and renal dysfunction in offspring from diabetic mothers. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2013;304:F189–F197. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00241.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Campo L, Blanco-Rivero J, Balfagon G. Fenofibrate increases neuronal vasoconstrictor response in mesenteric arteries from diabetic rats: role of noradrenaline, neuronal nitric oxide and calcitonin gene-related peptide. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;666:142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabelea D. The predisposition to obesity and diabetes in offspring of diabetic mothers. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(Suppl. 2):S169–S174. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enero MA, Langer SZ, Rothlin RP, Stefano FJ. Role of the alpha-adrenoceptor in regulating noradrenaline overflow by nerve stimulation. 1971. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120(4 Suppl):361–377. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1997.tb06817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favero G, Paganelli C, Buffoli B, Rodella LF, Rezzani R. Endothelium and its alterations in cardiovascular diseases: life style intervention. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:801896. doi: 10.1155/2014/801896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer M, Marín J, Balfagón G. Diabetes alters neuronal nitric oxide release from rat mesenteric arteries. Role of protein kinase C. Life Sci. 2000;66:337–345. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00595-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer M, Sánchez M, Minoves N, Salaices M, Balfagón G. Aging increases neuronal nitric oxide release and superoxide anion generation in mesenteric arteries from spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Vasc Res. 2003;40:509–519. doi: 10.1159/000075183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioramonti X, Marsollier N, Song Z, Fakira KA, Patel RM, Brown S, et al. Ventromedial hypothalamic nitric oxide production is necessary for hypoglycemia detection and counterregulation. Diabetes. 2010;59:519–528. doi: 10.2337/db09-0421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill V, Johansson B, Jalkanen P, Eriksson UJ. Influence of severe diabetes mellitus early in pregnancy in the rat: effects on insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in the offspring. Diabetologia. 1991;34:373–378. doi: 10.1007/BF00403173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatanaka Y, Hobara N, Honghua J, Akiyama S, Nawa H, Kobayashi Y, et al. Neuronal nitric-oxide synthase inhibition facilitates adrenergic neurotransmission in rat mesenteric resistance arteries. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:490–497. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.094656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinchee-Rodriguez K, Garg N, Venkatakrishnan P, Roman MG, Adamo ML, Masters BS, et al. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase is phosphorylated in response to insulin stimulation in skeletal muscle. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;435:501–505. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holemans K, Gerber RT, Meurrens K, de Clerck F, Poston I, Van Assche FA. Streptozotocin diabetes in the pregnant rat induces cardiovascular dysfunction in adult offspring. Diabetologia. 1999;42:81–89. doi: 10.1007/s001250051117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horal M, Zhang Z, Stanton R, Virkamäki A, Loeken MR. Activation of the hexosamine pathway causes oxidative stress and abnormal embryo gene expression: involvement in diabetic teratogenesis. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2004;70:519–527. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iellamo F, Tesauro M, Rizza S, Aquilani S, Cardillo C, Iantorno M, et al. Concomitant impairment in endothelial function and neural cardiovascular regulation in offspring of type 2 diabetic subjects. Hypertension. 2006;48:418–423. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000234648.62994.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanagy NL. α2-Adrenergic receptor signaling in hypertension. Clin Sci. 2005;109:431–437. doi: 10.1042/CS20050101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandlikar SS, Fink GD. Splanchnic sympathetic nerves in the development of mild DOCA-salt hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1965–H1973. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00086.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katkhuda R, Peterson ES, Roghair RD, Norris AW, Scholz TD, Segar JL. Sex-specific programming of hypertension in offspring of late-gestation diabetic rats. Pediatr Res. 2012;72:352–361. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki H, Takasaki K, Saito A, Goto K. Calcitonin gene related peptide acts as a novel vasodilator neurotransmitter in mesenteric resistance vessels of the rat. Nature. 1988;335:164–167. doi: 10.1038/335164a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T, Hatanaka Y, Jin X, Yokomizo A, Fujiwara H, Goda M, et al. Altered function of nitrergic nerves inhibiting sympathetic neurotransmission in mesenteric vascular beds of renovascular hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res. 2010;33:485–491. doi: 10.1038/hr.2010.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TJ. Sympathetic modulation of nitrergic neurogenic vasodilation in cerebral arteries. Jpn J Pharmacol. 2002;88:26–31. doi: 10.1254/jjp.88.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Chase M, Jung SK, Smith PJ, Loeken MR. Hypoxic stress in diabetic pregnancy contributes to impaired embryo gene expression and defective development by inducing oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E591–E599. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00441.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YJ, Duckles SP. Effect of endothelium on the actions of sympathetic and sensory nerves in the perfused rat mesentery. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;210:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90647-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loesch A. Perivascular nerves and vascular endothelium: recent advances. Histol Histopathol. 2002;17:591–597. doi: 10.14670/HH-17.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohmeier TE. The sympathetic nervous system and long-term blood pressure regulation. Am J Hypertens. 2001;14(6 Pt 2):147S–154S. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(01)02082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín J, Balfagón G. Effect of clenbuterol on non-endothelial nitric oxide release in rat mesenteric arteries and the involvement of beta-adrenoceptors. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:473–478. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín J, Ferrer M, Balfagón G. Role of protein kinase C in electrical-stimulation-induced neuronal nitric oxide release in mesenteric arteries from hypertensive rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 2000;99:277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meininger GA, Routh LK, Granger HJ. Autoregulation and vasoconstriction in the intestine during acute renal hypertension. Hypertension. 1985;7:364–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morriss FH., Jr Infants of diabetic mothers. Fetal and neonatal pathophysiology. Perspect Pediatr Pathol. 1984;8:223–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nehiri T, Duong Van Huyen JP, Viltard M, Fassot C, Heudes D, Freund N, et al. Exposure to maternal diabetes induces salt-sensitive hypertension and impairs renal function in adult rat offspring. Diabetes. 2008;57:2167–2175. doi: 10.2337/db07-0780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen KC, Owman C. Contractile response and amine receptor mechanism in isolated middle cerebral artery of the cat. Brain Res. 1971;27:33–42. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90370-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn JW, Fink GD. Region-specific changes in sympathetic nerve activity in angiotensin II-salt hypertension in the rat. Exp Physiol. 2010;95:61–68. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2008.046326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP, et al. NC-IUPHAR. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert-driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;42(Database Issue):D1098–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plagemann A, Harder T, Janert U, Rake A, Rittel F, Rohde W, et al. Malformations of hypothalamic nuclei in hyperinsulinemic offspring of rats with gestational diabetes. Dev Neurosci. 1999;21:58–67. doi: 10.1159/000017367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porto NP, Jucá DM, Lahlou S, Coelho-de-Souza AN, Duarte GP, Magalhães PJ. Effects of K+ channels inhibitors on the cholinergic relaxation of the isolated aorta of adult offspring rats exposed to maternal diabetes. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2010;118:360–363. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1241824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Alves FE, de Queiroz DB, Santos-Rocha J, Duarte GP, Xavier FE. Effect of age and COX-2-derived prostanoids on the progression of adult vascular dysfunction in the offspring of diabetic rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2012a;166:2198–2208. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Alves FE, de Queiroz DB, Santos-Rocha J, Duarte GP, Xavier FE. Increased cyclooxygenase-2-derived prostanoids contributes to the hyperreactivity to noradrenaline in mesenteric resistance arteries from offspring of diabetic rats. PLoS ONE. 2012b;7:e50593. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha SO, Gomes GN, Forti AL, do Carmo Pinho Franco M, Fortes ZB, de Fátima Cavanal M, et al. Long-term effects of maternal diabetes on vascular reactivity and renal function in the rat male offspring. Pediatr Res. 2005;58:1274–1279. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000188698.58021.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rummery NM, Brock JA, Pakdeechote P, Ralevic V, Dunn WR. ATP is the predominant sympathetic neurotransmitter in rat mesenteric arteries at high pressure. J Physiol. 2007;582:745–754. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.134825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Merino JA, Arribas S, Arranz A, Marín J, Balfagón G. Regulation of noradrenaline release in human cerebral arteries via presynaptic alpha 2-adrenoceptors. Gen Pharmacol. 1990;21:859–862. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(90)90445-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre E, Márquez-Rodas I, Blanco-Rivero J, Balfagón G. Perivascular innervation of the superior mesenteric artery: pathophysiological implications. Rev Neurol. 2010;50:727–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre E, Balfagón G, Revuelta-López E, Aller MA, Nava MP, Arias J, et al. Effect of short- and long-term portal hypertension on adrenergic, nitrergic and sensory functioning in rat mesenteric artery. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012a;122:337–348. doi: 10.1042/CS20110303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre E, Blanco-Rivero J, Caracuel L, Lahera V, Balfagón G. Effects of lipopolysaccharide on the neuronal control of mesenteric vascular tone in rats: mechanisms involved. Shock. 2012b;38:328–334. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31826240ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sastre E, Caracuel L, Balfagón G, Blanco-Rivero J. Aerobic exercise training increases nitrergic innervation function and decreases sympathetic innervation function in mesenteric artery from rats fed a high-fat diet. J Hypertens. 2015;33:1819–1830. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherrer U, Sartori C. Insulin as a vascular and sympathoexcitatory hormone: implications for blood pressure regulation, insulin sensitivity, and cardiovascular morbidity. Circulation. 1997;96:4104–4113. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.11.4104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segar EM, Norris AW, Yao JR, Hu S, Koppenhafer SL, Roghair RD, et al. Programming of growth, insulin resistance and vascular dysfunction in offspring of late gestation diabetic rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 2009;117:129–138. doi: 10.1042/CS20080550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeoni U, Barker DJ. Offspring of diabetic pregnancy: long-term outcomes. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen U, Wadsworth RM, Buus NH, Mulvany MJ. In vitro simultaneous measurements of relaxation and nitric oxide concentration in rat superior mesenteric artery. J Physiol. 1999;516:271–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.271aa.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa JB, Vieira-Rocha MS, Sá C, Ferreirinha F, Correia-de-Sá P, Fresco P, et al. Lack of endogenous adenosine tonus on sympathetic neurotransmission in spontaneously rat mesenteric artery. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e105540. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steculorum SM, Bouret SG. Maternal diabetes compromises the organization of hypothalamic feeding circuits and impairs leptin sensitivity in offspring. Endocrinology. 2011;152:4171–4179. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran S, Chen YW, Chenier I, Chan JS, Quaggin S, Hébert MJ, et al. Maternal diabetes modulates renal morphogenesis in offspring. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:943–952. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007080864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhoutte PM, Houston DS. Platelets, endothelium, and vasospasm. Circulation. 1985;72:728–734. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.4.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visentin S, Grumolato F, Nardelli GB, Di Camillo B, Grisan E, Cosmi E. Early origins of adult disease: low birth weight and vascular remodeling. Atherosclerosis. 2014;237:391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichi RB, Souza SB, Casarini DE, Morris M, Barreto-Chaves ML, Irigoyen MC. Fetal physiological programming increased blood pressure in the offspring of diabetic mothers. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:1129–1133. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00366.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CC, Chen SJ, Yen MH. Loss of acetylcholine-induced relaxation by M3-receptor activation in mesenteric arteries of spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1997;30:245–252. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199708000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier FE, Rossoni LV, Alonso MJ, Balfagón G, Vassallo DV, Salaices M. Ouabain-induced hypertension alters the participation of endothelial factors in alpha-adrenergic responses differently in rat resistance and conductance mesenteric arteries. Br J Pharmacol. 2004a;143:215–225. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier FE, Salaices M, Márquez-Rodas I, Alonso MJ, Rossoni LV, Vassallo DV, et al. Neurogenic nitric oxide release increases in mesenteric arteries from ouabain hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2004b;22:949–957. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200405000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JB, Morrison SF. Effects of fetal and neonatal environment on sympathetic nervous system development. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(Suppl. 2):B156–B160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]