Abstract

We asked if the type of carotid body (CB) chemoreceptor stimulus influenced the ventilatory gain of the central chemoreceptors to CO2. The effect of CB normoxic hypocapnia, normocapnia and hypercapnia (carotid body  ≈ 22, 41 and 68 mmHg, respectively) on the ventilatory CO2 sensitivity of central chemoreceptors was studied in seven awake dogs with vascularly-isolated and extracorporeally-perfused CBs. Chemosensitivity with one CB was similar to that in intact dogs. In four CB-denervated dogs, absence of hyper-/hypoventilatory responses to CB perfusion with

≈ 22, 41 and 68 mmHg, respectively) on the ventilatory CO2 sensitivity of central chemoreceptors was studied in seven awake dogs with vascularly-isolated and extracorporeally-perfused CBs. Chemosensitivity with one CB was similar to that in intact dogs. In four CB-denervated dogs, absence of hyper-/hypoventilatory responses to CB perfusion with  of 19–75 mmHg confirmed separation of the perfused CB circulation from the brain. The group mean central CO2 response slopes were increased 303% for minute ventilation (

of 19–75 mmHg confirmed separation of the perfused CB circulation from the brain. The group mean central CO2 response slopes were increased 303% for minute ventilation ( )(P ≤ 0.01) and 251% for mean inspiratory flow rate (VT/TI) (P ≤ 0.05) when the CB was hypercapnic vs. hypocapnic; central CO2 response slopes for tidal volume (VT), breathing frequency (fb) and rate of rise of the diaphragm EMG increased in 6 of 7 animals but the group mean changes did not reach statistical significance. Group mean central CO2 response slopes were also increased 237% for

)(P ≤ 0.01) and 251% for mean inspiratory flow rate (VT/TI) (P ≤ 0.05) when the CB was hypercapnic vs. hypocapnic; central CO2 response slopes for tidal volume (VT), breathing frequency (fb) and rate of rise of the diaphragm EMG increased in 6 of 7 animals but the group mean changes did not reach statistical significance. Group mean central CO2 response slopes were also increased 237% for  (P ≤ 0.01) and 249% for VT/TI(P ≤ 0.05) when the CB was normocapnic vs. hypocapnic, but no significant differences in any of the central ventilatory response indices were found between CB normocapnia and hypercapnia. These hyperadditive effects of CB hyper-/hypocapnia agree with previous findings using CB hyper-/hypoxia.We propose that hyperaddition is the dominant form of chemoreceptor interaction in quiet wakefulness when the chemosensory control system is intact, response gains physiological, and carotid body chemoreceptors are driven by a wide range of O2 and/or CO2.

(P ≤ 0.01) and 249% for VT/TI(P ≤ 0.05) when the CB was normocapnic vs. hypocapnic, but no significant differences in any of the central ventilatory response indices were found between CB normocapnia and hypercapnia. These hyperadditive effects of CB hyper-/hypocapnia agree with previous findings using CB hyper-/hypoxia.We propose that hyperaddition is the dominant form of chemoreceptor interaction in quiet wakefulness when the chemosensory control system is intact, response gains physiological, and carotid body chemoreceptors are driven by a wide range of O2 and/or CO2.

Key points

The influence of specific carotid body (CB) normoxic hypocapnia, hypercapnia and normocapnia on the ventilatory sensitivity of central chemoreceptors to systemic hypercapnia was assessed in seven awake dogs with extracorporeal perfusion of the vascularly isolated CB.

Chemosensitivity in this preparation was similar to that in the intact animal.

Separation of CB circulation from that of the brain was confirmed.

When the isolated CB was hypercapnic vs. hypocapnic and when the isolated CB was normocapnic vs. hypocapnic, the group mean central CO2 response slopes of minute ventilation (

) (P ≤ 0.01) and mean inspiratory flow rate (VT/TI) (P ≤ 0.05) increased significantly. Tidal volume (VT), breathing frequency (fb)and rate of rise of diaphragm EMG were increased in 6 of 7 dogs but did not achieve statistical significance.

) (P ≤ 0.01) and mean inspiratory flow rate (VT/TI) (P ≤ 0.05) increased significantly. Tidal volume (VT), breathing frequency (fb)and rate of rise of diaphragm EMG were increased in 6 of 7 dogs but did not achieve statistical significance.

We propose that hyperaddition is the dominant form of chemoreceptor interaction under conditions of quiet wakefulness in intact animals and over a wide range of CB

and

and  .

.

Introduction

Peripheral–central chemoreceptor interactive effects on control of breathing have been observed using animal models with isolated perfusion of the carotid body and/or central chemoreceptors in such varied conditions as eupnoea, apnoea, hypercapnia, and hypoxia (Day & Wilson, 2007,2009; Smith et al. 2007,2010; Blain et al. 2009,2010; Dempsey et al. 2012; Fiamma et al. 2013). However, the exact nature of these chemoreceptor interactions are controversial with studies in a wide variety of experimental preparations and theoretical models claiming additive, hyperadditive, or hypoadditive effects on the control of breathing (Duffin, 1990; Duffin & Mateika, 2013; Teppema & Smith, 2013; Wilson & Day, 2013). Based on these divergent findings some investigators (Wilson & Day, 2013; Guyenet, 2014) have suggested a ‘hybrid’ model as a basis for peripheral–central interaction, whereby variations in both the experimental models and in the prevailing physiological conditions and/or chemoreceptor stimuli may markedly alter the nature of the chemoreceptor interactions (also see Discussion).

Accordingly, in the present study we have tested the nature of the peripheral–central interaction under novel experimental conditions consisting of hypercapnic stimulation and hypocapnic inhibition at the level of the isolated CB chemoreceptor. This represents an important advance in addressing the interaction problem for several reasons. First, comparing normoxic hypercapnia/hypocapnia to results from our prior use of hypoxia/hyperoxia at the carotid body (Blain et al. 2010) provides a test of the equivalence of the observed hyperadditive interactive effect in the presence of both major peripheral chemoreceptor stimuli, i.e. CO2 and O2. Second, perturbations in  per se have widespread physiological significance in the control of breathing and breathing stability during wakefulness and sleep, which appear to depend critically upon peripheral–central chemoreceptor interactions (Smith et al. 2007; Dempsey et al. 2012; Fiamma et al. 2013). Third, we tested these interactive effects in a unique awake canine preparation which incorporates two essential characteristics for quantifying the nature of these interactions, namely (a) that the preparation’s chemoresponsiveness is within the physiological range and close to that in the intact animal, and (b) that central and peripheral chemoreceptors are truly separated both anatomically and functionally. Fourth, although there is no direct evidence we are aware of that the carotid sinus nerve discharge pattern can encode information concerning the nature of the carotid body stimulus, there are some lines of evidence showing that carotid body hypercapnia might have quite different cardiorespiratory influences from carotid body hypoxaemia. For example, in the awake goat, carotid body hypoxia, even for very short periods beyond the acute phase, progressively increased the ventilatory response whereas specific carotid body hypercapnia did not (Bisgard et al. 1986). In anesthetized goats short periods of hypoxia sensitized output of the carotid body chemoreceptor (Nielsen et al. 1988), whereas hypercapnia did not (Engwall et al. 1988). In anaesthetized rats, carotid body denervation prevented the response of CO2 sensitive neurons in the retrotrapezoid nucleus to very brief exposures of reduced

per se have widespread physiological significance in the control of breathing and breathing stability during wakefulness and sleep, which appear to depend critically upon peripheral–central chemoreceptor interactions (Smith et al. 2007; Dempsey et al. 2012; Fiamma et al. 2013). Third, we tested these interactive effects in a unique awake canine preparation which incorporates two essential characteristics for quantifying the nature of these interactions, namely (a) that the preparation’s chemoresponsiveness is within the physiological range and close to that in the intact animal, and (b) that central and peripheral chemoreceptors are truly separated both anatomically and functionally. Fourth, although there is no direct evidence we are aware of that the carotid sinus nerve discharge pattern can encode information concerning the nature of the carotid body stimulus, there are some lines of evidence showing that carotid body hypercapnia might have quite different cardiorespiratory influences from carotid body hypoxaemia. For example, in the awake goat, carotid body hypoxia, even for very short periods beyond the acute phase, progressively increased the ventilatory response whereas specific carotid body hypercapnia did not (Bisgard et al. 1986). In anesthetized goats short periods of hypoxia sensitized output of the carotid body chemoreceptor (Nielsen et al. 1988), whereas hypercapnia did not (Engwall et al. 1988). In anaesthetized rats, carotid body denervation prevented the response of CO2 sensitive neurons in the retrotrapezoid nucleus to very brief exposures of reduced  , but had no effect on their response to inhaled CO2(Mulkey et al. 2004). In anaesthetized rats conditioned by exposure to chronic intermittent hypoxia for 10 days, acute intermittent hypoxia elicited long-term facilitation of carotid sinus nerve output whereas acute intermittent hyperoxic hypercapnia did not (Peng et al. 2003). Further, in awake humans, acute periods of arterial isocapnic hypoxaemia or asphyxia elicited marked lingering after-effects on muscle sympathetic nerve activity once the stimulus was removed whereas similar periods of arterial normoxic hypercapnia did not (Morgan et al. 1995; Xie et al. 2000,2001).

, but had no effect on their response to inhaled CO2(Mulkey et al. 2004). In anaesthetized rats conditioned by exposure to chronic intermittent hypoxia for 10 days, acute intermittent hypoxia elicited long-term facilitation of carotid sinus nerve output whereas acute intermittent hyperoxic hypercapnia did not (Peng et al. 2003). Further, in awake humans, acute periods of arterial isocapnic hypoxaemia or asphyxia elicited marked lingering after-effects on muscle sympathetic nerve activity once the stimulus was removed whereas similar periods of arterial normoxic hypercapnia did not (Morgan et al. 1995; Xie et al. 2000,2001).

We found that, in the awake dog, specific carotid body stimulation/inhibition by means of hyper- or hypocapnia resulted in hyperadditive interaction when the central chemoreceptors were stimulated by means of increased  . The similarity of these hyperadditive interactions to those caused primarily by means of changes in carotid body

. The similarity of these hyperadditive interactions to those caused primarily by means of changes in carotid body  suggest that short-term changes in

suggest that short-term changes in  and

and  at the carotid body have equivalent effects on peripheral–central interaction for a given change in baseline ventilation.

at the carotid body have equivalent effects on peripheral–central interaction for a given change in baseline ventilation.

Methods

Ethical approval

Experimental protocols and the roles of each investigator involved were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health and were performed with strict adherence to all American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC) and National Institutes of Health guidelines embodied in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th edition, published by the National Academies Press, 2011.

Animals

Studies were performed during wakefulness on 13 unanaesthetized, spayed (n = 12) or anoestrus (n = 1), adult, female, mixed-breed dogs (20–25 kg). The dogs were trained to lie quietly in an air conditioned (19–22°C) sound attenuated chamber. The dogs were housed in an AAALAC accredited animal care facility. Seven of the 13 dogs were used in the main perfusion/interaction portion of the study. Four additional dogs were used to assess the anatomical isolation of our perfusion preparation. Two additional dogs were used to further assess the ventilatory effects of unilateral CB denervation.

Surgical procedures and chronic instrumentation

Our preparation required two surgical procedures performed under general anaesthesia; identical anaesthetic protocols were used for both procedures. All dogs were pre-medicated with acepromazine (0.04–0.08 mg · kg−1s.c. or i.m.) and buprenorphine (0.01–0.03 mg · kg−1i.v. or i.m.); induced with propofol (3–5 mg · kg−1i.v.); intubated immediately with a 7.5 mm ID cuffed endotracheal tube and maintained with 1–2% isoflurane in O2 with mechanical ventilation. Strict sterile surgical techniques and appropriate postoperative analgesics and antibiotics were used. No agents producing neuromuscular blockade (‘paralysing’ agents) were used.

In the first procedure, using a ventral abdominal midline approach, 12 of 13 dogs were subjected to ovariectomy and hysterectomy, a chronic indwelling catheter was placed into the abdominal aorta via a branch of the femoral artery, and bipolar electromyogram (EMG) recording electrodes were installed into the costal diaphragm. The catheter and EMG wires were tunnelled subcutaneously to the dorsal aspect of the thorax where they were exteriorized a few centimetres caudal to the scapulae.

After a recovery interval of at least 3 weeks a second procedure was performed in which the left carotid body (CB) was denervated (CBD). The right carotid sinus was equipped with a vascular occluder and catheter to permit extracorporeal perfusion of the reversibly isolated carotid sinus–carotid body. A chronic indwelling catheter was also placed in the cranial vena cava via a branch of the jugular vein. Catheters were tunnelled subcutaneously to the lateral aspect of the dog’s neck where they were exteriorized. Dogs recovered for at least 4 days before study.

The instrumentation was protected with a heavy nylon jacket and a padded ‘Elizabethan’ collar modified to allow normal eating and drinking.

Post-operative analgesia was achieved with buprenorphine (0.005 to 0.02 mg · kg−1i.m. or i.v. q6–12 h; initial dose administered 30 min prior to the end of surgery) for the first 24 h in the first procedure and 12 h in the less invasive second procedure. We also administered one s.c. dose of carprofen (4 mg · kg−1; Pfizer, NY, USA) just after induction of anaesthesia. We continued carprofen p.o. (2.2 mg · kg−1q 12 h or 4.4 mg · kg−1q 24 h) for 3–7 days.

A wide-spectrum oral antibiotic (cephalexin, Karalex Pharma, NJ, USA) 20–30 mg · kg−1p.o., BID or cefpodoxime proxetil (Pfizer, NY, USA) 10 mg · kg−1, p.o., SID or enrofloxacin (Bayer, KS, USA) 5–10 mg · kg−1, p.o., SID) was begun 24 h prior to surgery and was continued for 5–7 days post-operatively for the first procedure and 7–21 days for the second procedure. In addition, cefazolin (Sagent, IL, USA) (20–30 mg · kg−1, slow i.v. injection) was administered immediately pre-operatively and every 2 h intra-operatively.

It is important to note that we used spayed female dogs (and one ovaries and uterus-intact dog which was in anoestrus) to avoid problems with ventilatory effects of fluctuating ovarian hormone levels. We do not think this introduces a significant bias; we have discussed this in detail in a previous publication (Blain et al. 2009).

Carotid sinus perfusion

Dogs lay unrestrained on a bed within the sound attenuated chamber. The extracorporeal circuit was primed with ∼700 ml of saline, 120 ml of allogenic, packed red cell blood (Animal Blood Resources International, Dixon, CA, USA), and 2000 U of heparin and supplemented with 500–1000 U · h−1.  ,

,  and pH in the perfusion circuit were set by adjustment of the gas concentrations supplying the circuit and by addition of NaHCO3. Complete isolation of the carotid body from the systemic circulation and absence of any other peripheral chemosensitivity were confirmed by lack of ventilatory response to systemic intravenous injections of NaCN (20–30 μg · kg−1) during isolated sinus perfusion (‘CB perfusion’). The retrograde perfusion of the carotid sinus region raised blood pressure in the sinus <10 mmHg, a level shown to have no effect on breathing in the unanaesthetized canine (Saupe et al. 1995). These techniques have been described in detail in previous publications (Smith et al. 1995,2006; Curran et al. 2000; Blain et al. 2009).

and pH in the perfusion circuit were set by adjustment of the gas concentrations supplying the circuit and by addition of NaHCO3. Complete isolation of the carotid body from the systemic circulation and absence of any other peripheral chemosensitivity were confirmed by lack of ventilatory response to systemic intravenous injections of NaCN (20–30 μg · kg−1) during isolated sinus perfusion (‘CB perfusion’). The retrograde perfusion of the carotid sinus region raised blood pressure in the sinus <10 mmHg, a level shown to have no effect on breathing in the unanaesthetized canine (Saupe et al. 1995). These techniques have been described in detail in previous publications (Smith et al. 1995,2006; Curran et al. 2000; Blain et al. 2009).

Experimental set-up and measurements

Ventilation was measured using a tight-fitting muzzle mask connected to a pneumotachograph (model 3700, Hans Rudolph, Kansas City, MO, USA) that was calibrated before each study with four known flows. The dogs were acclimated to the mask during several weeks of training prior to study. Costal diaphragm EMG (EMGdi) signals were amplified, band-pass filtered (100–1000 Hz), rectified and moving-time-averaged (BMA-931; MA-821RSP, CWE Ardmore, PA, USA). End tidal  and

and  were measured using appropriate analysers (Applied Electrochemistry S3-A, Pittsburgh, PA, USA and Sable Systems CA-1B, Las Vegas, NV, USA, respectively).

were measured using appropriate analysers (Applied Electrochemistry S3-A, Pittsburgh, PA, USA and Sable Systems CA-1B, Las Vegas, NV, USA, respectively).

Arterial and perfusion circuit blood samples (∼0.5–1.0 ml) were analysed for pH,  and

and  on a blood gas analyser (ABL-5 or ABL 700, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Blood pressure was recorded continuously from the femoral artery (Statham P23XL, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA).

on a blood gas analyser (ABL-5 or ABL 700, Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). Blood pressure was recorded continuously from the femoral artery (Statham P23XL, Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA, USA).

Ventilation and blood pressure signals were digitized (128 Hz sampling frequency) and stored on the hard disk of a PC for subsequent analysis. Key signals were also recorded continuously on a polygraph (AstroMed K2G, West Warwick, RI, USA). All ventilatory data were analysed on a breath-by-breath basis by means of custom analysis software developed in our laboratory.

Experimental protocol

Interaction

Eupnoeic ventilation and blood gases and the ventilatory response to hypercapnia via increased  were determined under three sets of conditions: (a) when the carotid bodies were both intact with normal endogenous CB perfusion;(b) after unilateral CB denervation with normal endogenous CB perfusion; and(c) during normal, hypocapnic/normoxic, or hypercapnic/normoxic CB perfusion (see below). In the steady-state of each CB perfusion condition, the ventilatory response to inhaled CO2 was assessed in a progressive, stepwise fashion consisting of 5–7 min intervals of air breathing followed by three increasingly higher levels of

were determined under three sets of conditions: (a) when the carotid bodies were both intact with normal endogenous CB perfusion;(b) after unilateral CB denervation with normal endogenous CB perfusion; and(c) during normal, hypocapnic/normoxic, or hypercapnic/normoxic CB perfusion (see below). In the steady-state of each CB perfusion condition, the ventilatory response to inhaled CO2 was assessed in a progressive, stepwise fashion consisting of 5–7 min intervals of air breathing followed by three increasingly higher levels of  (∼ 0.02, 0.04 and 0.06) such that

(∼ 0.02, 0.04 and 0.06) such that  was raised in steps achieving a maximum

was raised in steps achieving a maximum  ∼10 mmHg >eupnoea. Arterial blood gases were obtained during 3–7 min of exposure to each level of

∼10 mmHg >eupnoea. Arterial blood gases were obtained during 3–7 min of exposure to each level of  , and ventilation, diaphragm EMG activity and blood pressure were recorded continuously throughout.

, and ventilation, diaphragm EMG activity and blood pressure were recorded continuously throughout.

For CB perfusion, each test protocol consisted of a 5–7 min control period (eupnoea), during which perfusion of the CB was endogenous, i.e. systemic arterial blood. Two 1 ml blood samples were collected at ∼3–7 min for determination of control value for blood gases and pH. Then, CB perfusion was abruptly switched to the extracorporeal circuit. The dogs were perfused from the extracorporeal circuit with blood gases and pH concentrations matching a given dog’s eupnoeic values (CB normal), or with hypocapnic ( ∼20 mmHg) and normoxic blood, or with hypercapnic (

∼20 mmHg) and normoxic blood, or with hypercapnic ( ∼60–70 mmHg) and normoxic blood. The different CB perfusate conditions were presented in random order and usually repeated at least once on a different day. In the steady-state of each CB perfusion condition, the ventilatory response to central hypercapnia was assessed as described above; usually two to four response trials were obtained for each CB perfusion condition. We were able to complete central CO2 response trials in all three CB perfusion conditions in six dogs; in a seventh dog we completed only the CB hypo- and hypercapnic portions of the experiment.

∼60–70 mmHg) and normoxic blood. The different CB perfusate conditions were presented in random order and usually repeated at least once on a different day. In the steady-state of each CB perfusion condition, the ventilatory response to central hypercapnia was assessed as described above; usually two to four response trials were obtained for each CB perfusion condition. We were able to complete central CO2 response trials in all three CB perfusion conditions in six dogs; in a seventh dog we completed only the CB hypo- and hypercapnic portions of the experiment.

Assessing contamination of vertebral artery blood by perfusate

Four dogs were instrumented as described above but underwent bilateral CB denervation. CBD was confirmed by absence of a ventilatory response to intravenous NaCN (20–30 μg · kg−1). We used these dogs to assess the significance of potential CB perfusate contamination of the blood flow to the brain via the vertebral artery. To this end, air-breathing ventilation and blood gases were assessed during carotid sinus region perfusion with hypocapnic and hypercapnic perfusates. In two of these bilaterally carotid body denervated dogs we also tested their ventilatory response to inhaled CO2 (as described above) to verify that these animals were responsive to systemic hypercapnia.

Killing

Upon completion of the protocol, dogs (n = 12) were humanely killed with an overdose of 200 mg propofol into the implanted i.v. catheter followed by 5 ml Beuthanasia-D Special (Schering Plough, NJ, USA) via the same catheter after full unconsciousness was achieved. One dog was enrolled in a special protocol at the University of Wisconsin that allows removal of instrumentation and subsequent adoption after a suitable period of recovery.

Statistics

Slopes of the CO2 responses were determined by linear regression. Significance of the differences in group mean ventilatory responses to central hypercapnia between the three CB perfusion conditions was determined by means of one-way ANOVA. Significant ANOVAs were followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc analyses with correction for unequal n using the harmonic mean of n(Portney & Watkins, 2009). The significance of the ventilatory effects of unilateral CBD was determined by means of one-way ANOVA. Means are presented as mean ± SD. Differences were considered significant if P ≤ 0.05.

Results

Unilateral carotid body denervation

Table1 shows the effects of unilateral CBD on key ventilatory components for the seven dogs used in the main interaction portion of this study. On average, there was a modest, variable and non-significant hypoventilation ( = +4.5 ± 5.9 mmHg; P > 0.08) following unilateral CBD. There were no significant changes in the other ventilatory components. Including two earlier studies from our laboratory (Curran et al. 2000; Blain et al. 2010) as well as the present study we now have data from 26 dogs before and within 7–10 days following unilateral CBD. In this larger pool of dogs we found a small but significant (P < 0.01) average CO2 retention compared to intact controls (intact:

= +4.5 ± 5.9 mmHg; P > 0.08) following unilateral CBD. There were no significant changes in the other ventilatory components. Including two earlier studies from our laboratory (Curran et al. 2000; Blain et al. 2010) as well as the present study we now have data from 26 dogs before and within 7–10 days following unilateral CBD. In this larger pool of dogs we found a small but significant (P < 0.01) average CO2 retention compared to intact controls (intact:  = 39.5 ± 1.9 mmHg vs. unilateral CBD:

= 39.5 ± 1.9 mmHg vs. unilateral CBD:  = 41.9 ± 3.9 mmHg). Fifteen of the 26 dogs hypoventilated more than 1.5 mmHg

= 41.9 ± 3.9 mmHg). Fifteen of the 26 dogs hypoventilated more than 1.5 mmHg  relative to the intact state; three hyperventilated more than 1.5 mmHg, and the remaining 8 dogs changed less than 1.5 mmHg. Intact vs. unilateral CBD ventilatory CO2 response slopes were available in 19 of the 26 dogs. The intact ventilatory response to hypercapnia averaged 0.69 ± 0.28 L · min−1 · mmHg−1 and was not significantly different from the unilateral CBD response, which averaged 0.63 ± 0.22 (P > 0.4).

relative to the intact state; three hyperventilated more than 1.5 mmHg, and the remaining 8 dogs changed less than 1.5 mmHg. Intact vs. unilateral CBD ventilatory CO2 response slopes were available in 19 of the 26 dogs. The intact ventilatory response to hypercapnia averaged 0.69 ± 0.28 L · min−1 · mmHg−1 and was not significantly different from the unilateral CBD response, which averaged 0.63 ± 0.22 (P > 0.4).

Table 1.

Eupnoeic values during air breathing when the dogs were intact vs. unilateral CBD(CB not perfused)

| Intact | Unilateral CBD | |

|---|---|---|

| n | 7 | 7 |

| pHa | 7.37 (0.03) | 7.35 (0.03) |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

39.15 (2.52) | 43.70 (5.94) |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

101.80 (3.54) | 100.95 (5.70) |

(L · min−1) (L · min−1) |

4.50 (0.78) | 3.80 (0.59) |

| VT (L) | 0.36 (0.05) | 0.37 (0.10) |

| fb (breaths · min−1) | 12.84 (2.91) | 11.12 (3.35) |

| VT/TI (L · s−1) | 0.21 (0.02) | 0.18 (0.02) |

Data are means (SD).

Assessing contamination of vertebral artery blood by CB perfusates

In two bilaterally carotid body denervated dogs we obtained normoxic steady-state ventilatory response curves to systemic hypercapnia via increased  which were decreased relative to the intact condition by 40% (Δ

which were decreased relative to the intact condition by 40% (Δ /Δ

/Δ , 0.57 to 0.34 L · min−1 · mmHg−1) and 70% (Δ

, 0.57 to 0.34 L · min−1 · mmHg−1) and 70% (Δ /Δ

/Δ , 0.81 to 0.25 L · min−1 · mmHg−1). Taken together with our earlier findings in this species (Rodman et al. 2001), these data confirm that our awake canine model remains highly responsive to systemic (and therefore central) hypercapnia even after bilateral CBD.

, 0.81 to 0.25 L · min−1 · mmHg−1). Taken together with our earlier findings in this species (Rodman et al. 2001), these data confirm that our awake canine model remains highly responsive to systemic (and therefore central) hypercapnia even after bilateral CBD.

Table2 shows the changes in steady-state eupnoeic air-breathing  in four carotid body denervated dogs (the two dogs mentioned in the preceding paragraph plus two additional dogs) in which the carotid sinus region was perfused for 5–10 min with blood that was hypocapnic (

in four carotid body denervated dogs (the two dogs mentioned in the preceding paragraph plus two additional dogs) in which the carotid sinus region was perfused for 5–10 min with blood that was hypocapnic ( 19–24 mmHg) or hypercapnic (

19–24 mmHg) or hypercapnic ( 66–75 mmHg). Note that the steady-state changes in

66–75 mmHg). Note that the steady-state changes in  and the ventilatory variables are small and not correlated with the

and the ventilatory variables are small and not correlated with the  of the perfusate; nor were any transient changes observed in ventilation or

of the perfusate; nor were any transient changes observed in ventilation or  at any time throughout the 5–10 min period of carotid sinus perfusion. The finding that increases or decreases in carotid sinus perfusate

at any time throughout the 5–10 min period of carotid sinus perfusion. The finding that increases or decreases in carotid sinus perfusate  did not change ventilation in a systematic, predictable fashion in these carotid body denervated dogs indicates that any contamination of the right vertebral artery blood flow with blood that we perfused into the carotid sinus region was functionally insignificant.

did not change ventilation in a systematic, predictable fashion in these carotid body denervated dogs indicates that any contamination of the right vertebral artery blood flow with blood that we perfused into the carotid sinus region was functionally insignificant.

Table 2.

Mean changes, relative to non-CB perfused, in steady-state air-breathing in response to hypercapnic and/or hypocapnic CB perfusates in four CBD dogs

| Dog |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

Δ (mmHg) (mmHg) |

Δ (L · min−1) (L · min−1) |

ΔVT (L) | Δfb (breaths · min−1) | ΔVT/TI (L · s−1) | ΔDiRR (% of control) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 19 | −0.3 | 0.6 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.05 | −0.8 |

| D | 24 | −0.7 | −0.1 | −0.03 | 0.1 | 0.00 | 6.7 |

| D | 66 | −1.1 | −0.2 | 0.03 | −1 | 0.01 | 1.0 |

| N | 75 | 0.3 | 1.2 | −0.32 | 1.8 | 0.01 | −31.9 |

| Q | 24 | −1.6 | 1.2 | 0.11 | −3.4 | 0.09 | −33.7 |

| Q | 68 | 0.5 | −0.4 | 0.02 | −2.8 | −0.01 | −7.9 |

Effects of CB hypercapnia and hypocapnia on eupnoea

Time course

In four dogs (of the 7 used in the main perfusion/interaction portion of the study) we obtained technically acceptable transitions from non-perfused to CB perfusion with hypercapnic blood during room air breathing. All four dogs increased  (mean Δ

(mean Δ = +2.32 L · min−1; range 0.36–2.89) reaching a peak

= +2.32 L · min−1; range 0.36–2.89) reaching a peak  at 29.7 s (mean; range 10–46 s) after perfusion was initiated. All four dogs achieved partial compensation for the transient hyperventilation such that the steady-state Δ

at 29.7 s (mean; range 10–46 s) after perfusion was initiated. All four dogs achieved partial compensation for the transient hyperventilation such that the steady-state Δ values (obtained in the third to seventh minute of perfusion; see Methods) averaged +0.23 L · min−1 (range −0.16 to +0.53).

values (obtained in the third to seventh minute of perfusion; see Methods) averaged +0.23 L · min−1 (range −0.16 to +0.53).

In five dogs (of the 7 used in the main perfusion/interaction portion of the study) we obtained technically acceptable transitions over 3–7 min periods from non-perfused to CB perfusion with hypocapnic blood during room air breathing. All five dogs decreased  reaching a nadir value (mean Δ

reaching a nadir value (mean Δ = −1.74 L · min−1; range −0.39 to −3.57) at 19.7 s (mean; range = 3–32 s) after hypocapnic perfusion was initiated. All five dogs achieved partial compensation for the transient hypoventilation such that the steady-state Δ

= −1.74 L · min−1; range −0.39 to −3.57) at 19.7 s (mean; range = 3–32 s) after hypocapnic perfusion was initiated. All five dogs achieved partial compensation for the transient hypoventilation such that the steady-state Δ values (obtained in the third to seventh minute of perfusion; see Methods) averaged −0.43 L · min−1 (range +0.62 to −1.68).

values (obtained in the third to seventh minute of perfusion; see Methods) averaged −0.43 L · min−1 (range +0.62 to −1.68).

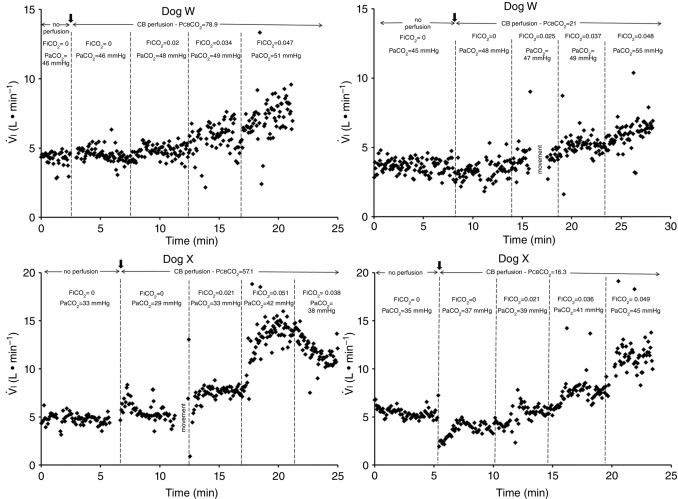

Figure 1 shows examples of transitions in response to the hypercapnic CB perfusion in two representative dogs, one with a brisk ventilatory response to changes in  (dog X) and one with a relatively small response (dog W). These transition data are consistent with previous reports from our laboratory (Smith et al. 1995; Blain et al. 2009).

(dog X) and one with a relatively small response (dog W). These transition data are consistent with previous reports from our laboratory (Smith et al. 1995; Blain et al. 2009).

Figure 1.

Breath-by-breath time course plots showing the effects of hypercapnic and hypocapnic CB perfusion on ventilation and the ventilatory response to systemic hypercapnia in two representative dogs

Key transitions are marked by vertical dashed lines; the initiation of perfusion is indicated by a filled arrow.  ,

,  and

and  for each condition are indicated above each panel. Dog W (upper panels) showed limited response to CB hypo- or hypercapnic perfusion during air breathing. Dog X (lower panels) showed larger responses to CB hypo- or hypercapnic perfusion during air breathing. Note that in both dogs,(a) there was a transient hyper-or hypoventilation in response to CB hypercapnia and CB hypocapnia, respectively (filled arrow and vertical dashed line),(b) after the transient peak or nadir, partial ventilatory compensation occurred (between first two vertical dashed lines in each panel), and(c) the ventilatory responses to increased

for each condition are indicated above each panel. Dog W (upper panels) showed limited response to CB hypo- or hypercapnic perfusion during air breathing. Dog X (lower panels) showed larger responses to CB hypo- or hypercapnic perfusion during air breathing. Note that in both dogs,(a) there was a transient hyper-or hypoventilation in response to CB hypercapnia and CB hypocapnia, respectively (filled arrow and vertical dashed line),(b) after the transient peak or nadir, partial ventilatory compensation occurred (between first two vertical dashed lines in each panel), and(c) the ventilatory responses to increased  and systemic hypercapnia (last 3 sections in each panel) were greater in both dogs during CB hypercapnia vs. CB hypocapnia (compare right panel to left panel in each dog after the filled arrow and vertical dashed line).

and systemic hypercapnia (last 3 sections in each panel) were greater in both dogs during CB hypercapnia vs. CB hypocapnia (compare right panel to left panel in each dog after the filled arrow and vertical dashed line).

Steady-state

Table3 shows the effect on steady-state, air-breathing eupnoea during specific carotid body normocapnia, hypercapnia and hypocapnia during CB perfusion. We observed that rather marked changes in CB  of ±20–30 mmHg were required to elicit measurable steady-state hyper- or hypoventilation during air-breathing in the steady-state. These responses were also highly variable among animals. Thus, comparing the group mean responses to CB hypercapnia vs. CB hypocapnia where all seven dogs are represented there was a non-significant trend toward hyperventilation (42 vs. 45.6 mmHg

of ±20–30 mmHg were required to elicit measurable steady-state hyper- or hypoventilation during air-breathing in the steady-state. These responses were also highly variable among animals. Thus, comparing the group mean responses to CB hypercapnia vs. CB hypocapnia where all seven dogs are represented there was a non-significant trend toward hyperventilation (42 vs. 45.6 mmHg  ) which is accompanied by non-significant trends toward alkalosis and increased

) which is accompanied by non-significant trends toward alkalosis and increased  , VT, VT/TI, and rate of rise of the diaphragm EMG (DiRR). Eupnoeic fb was unchanged by either hypercapnic or hypocapnic CB perfusion.

, VT, VT/TI, and rate of rise of the diaphragm EMG (DiRR). Eupnoeic fb was unchanged by either hypercapnic or hypocapnic CB perfusion.

Table 3.

Air breathing eupnoeic values during CB perfusion

| CB | CB | CB | |

|---|---|---|---|

| hypercapnia | normocapnia | hypocapnia | |

| n | 7 | 6 | 7 |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

68.2 (8.3) | 41.1 (6.1) | 22.3 (2.9) |

| pHa | 7.35 (0.05) | 7.34 (0.03) | 7.33 (0.03) |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

41.99 (9.67) | 42.51 (7.65) | 45.61 (6.70) |

(mmHg) (mmHg) |

112.64 (14.51) | 102.40 (5.58) | 94.16 (5.70) |

(L · min−1) (L · min−1) |

4.82 (1.04) | 4.21 (0.91) | 4.35 (1.13) |

| VT (L) | 0.47 (0.15) | 0.42 (0.08) | 0.41 (0.12) |

| fb (breaths · min−1) | 10.85 (2.75) | 10.28 (2.59) | 10.90 (3.05) |

| VT/TI (L · s−1) | 0.23 (0.05) | 0.21 (0.02) | 0.20 (0.02) |

| DiRR (% of control) | 107.17 (24.95) | 95.63 (7.54) | 96.94 (15.55) |

Data are means (SD).

Effects of CB hypercapnia and hypocapnia on the central ventilatory response to systemic hypercapnia

In the time course response to CB hyper- and hypocapnia shown in Fig. 1, the ventilatory response to progressive increases in  and, therefore, central hypercapnia are shown over the final three sections of each panel. It is readily apparent in both animals that the magnitude of the steady-state ventilatory responses to comparable levels of increasing systemic hypercapnia was substantially enhanced in the presence of CB hypercapnia (left panels) vs. CB hypocapnia (right panels). This hyperadditive effect was observed during both the early transitional and the steady-state phases of the ventilatory responses to central hypercapnia.

and, therefore, central hypercapnia are shown over the final three sections of each panel. It is readily apparent in both animals that the magnitude of the steady-state ventilatory responses to comparable levels of increasing systemic hypercapnia was substantially enhanced in the presence of CB hypercapnia (left panels) vs. CB hypocapnia (right panels). This hyperadditive effect was observed during both the early transitional and the steady-state phases of the ventilatory responses to central hypercapnia.

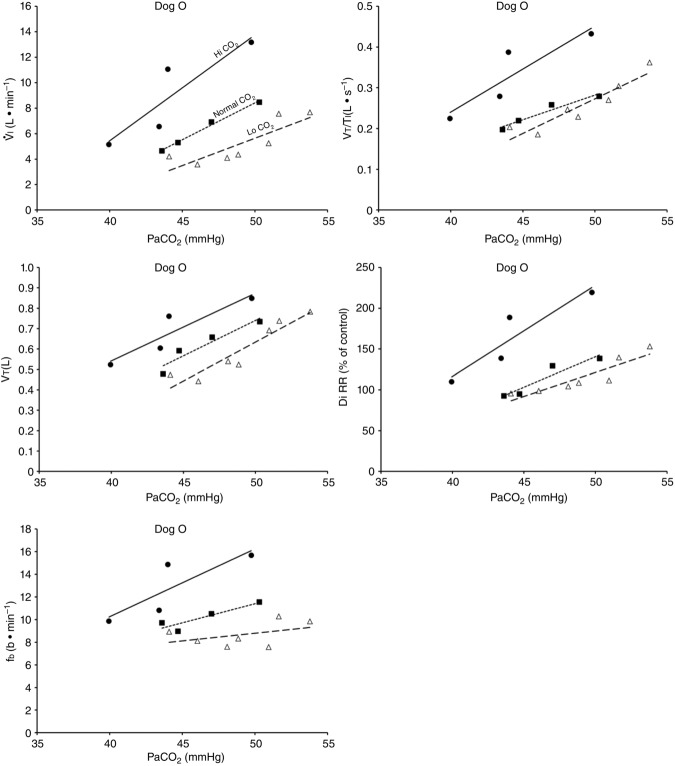

Figure 2 illustrates the steady-state responses of five ventilatory components in a representative dog to increased central  during CB perfusion with normocapnic, hypercapnic and hypocapnic blood. Note that the peripheral–central ventilatory interaction for

during CB perfusion with normocapnic, hypercapnic and hypocapnic blood. Note that the peripheral–central ventilatory interaction for  is hyperadditive (i.e. increased slope of CB hypercapnia vs. CB normocapnia vs. CB hypocapnia). In this dog, the hyperaddition of the

is hyperadditive (i.e. increased slope of CB hypercapnia vs. CB normocapnia vs. CB hypocapnia). In this dog, the hyperaddition of the  response between CB hypocapnia and CB hypercapnia was due entirely to hyperadditive responses of fb, VT/TI, and rate of rise of the diaphragm EMG (DiRR) as the VT response was additive (i.e. no slope change). The slope of the central ventilatory response to CB normocapnia was intermediate to those for CB hypo- and hypercapnia for most variables except VT/TI and VT.

response between CB hypocapnia and CB hypercapnia was due entirely to hyperadditive responses of fb, VT/TI, and rate of rise of the diaphragm EMG (DiRR) as the VT response was additive (i.e. no slope change). The slope of the central ventilatory response to CB normocapnia was intermediate to those for CB hypo- and hypercapnia for most variables except VT/TI and VT.

Figure 2.

Steady-state ventilatory responses of five key ventilatory components to increased FICO2

Data obtained during CB normocapnic ( = 39.2 mmHg), CB hypercapnic (

= 39.2 mmHg), CB hypercapnic ( = 73.4 mmHg) and CB hypocapnic (

= 73.4 mmHg) and CB hypocapnic ( = 22.3 mmHg) perfusion in a representative dog. Lines are linear regressions.

= 22.3 mmHg) perfusion in a representative dog. Lines are linear regressions.

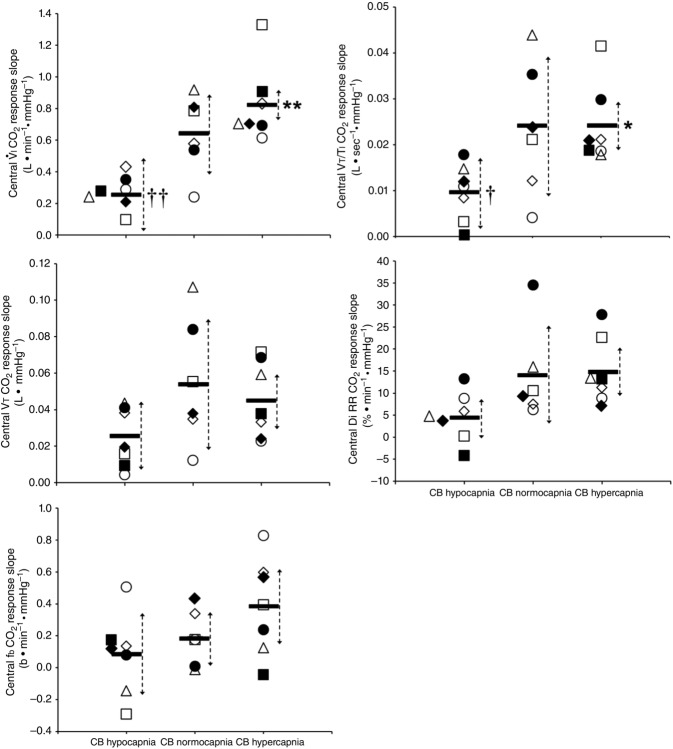

Central CO2 response slopes for all variables during CB normocapnia, hypercapnia and hypocapnia are summarized as individual slopes and group means for all animals in Fig. 3. The central CO2 response slopes for  and VT/TI were significantly increased (0.27 ± 0.11vs. 0.82 ± 0.24 L min−1 · mmHg−1 (means ± SD, P ≤ 0.01) and 0.024 ± 0.006 vs. 0.010 ± 0.009 L · s−1 · mmHg−1 (P ≤ 0.05), respectively). When isolated CB hypocapnia was compared to CB hypercapnia. Increases in the central CO2 response for VT, fb, and DiRR between CB hypo-vs. hypercapnia increased in 6 of 7 dogs but did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05; also see Fig. 3). Similarly, the central CO2 responses between CB hypocapnia and CB normocapnia were increased for

and VT/TI were significantly increased (0.27 ± 0.11vs. 0.82 ± 0.24 L min−1 · mmHg−1 (means ± SD, P ≤ 0.01) and 0.024 ± 0.006 vs. 0.010 ± 0.009 L · s−1 · mmHg−1 (P ≤ 0.05), respectively). When isolated CB hypocapnia was compared to CB hypercapnia. Increases in the central CO2 response for VT, fb, and DiRR between CB hypo-vs. hypercapnia increased in 6 of 7 dogs but did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05; also see Fig. 3). Similarly, the central CO2 responses between CB hypocapnia and CB normocapnia were increased for  and VT/TI (0.27 ± 0.11 vs. 0.64 ± 0.25 L · min−1 · mmHg−1 (P ≤ 0.01) and 0.010 ± 0.006 vs. 0.024 ± 0.010 L · s−1 · mmHg−1 (P ≤ 0.05) respectively). Increases in the central CO2 response for VT, fb, and DiRR between CB hypocapnia and CB normocapnia increased in 5 of 6 dogs but did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05; also see Fig. 3). Finally, none of the central CO2 response slopes between CB normocapnia and CB hypercapnia changed significantly (P > 0.05) although most dogs showed an increased slope with CB hypercapnia.

and VT/TI (0.27 ± 0.11 vs. 0.64 ± 0.25 L · min−1 · mmHg−1 (P ≤ 0.01) and 0.010 ± 0.006 vs. 0.024 ± 0.010 L · s−1 · mmHg−1 (P ≤ 0.05) respectively). Increases in the central CO2 response for VT, fb, and DiRR between CB hypocapnia and CB normocapnia increased in 5 of 6 dogs but did not reach statistical significance (P > 0.05; also see Fig. 3). Finally, none of the central CO2 response slopes between CB normocapnia and CB hypercapnia changed significantly (P > 0.05) although most dogs showed an increased slope with CB hypercapnia.

Figure 3.

Individual and mean ventilatory response slopes to increased systemic PaCO2 grouped by CB perfusate condition

Each type of symbol represents the responses of one dog; the thick horizontal bars represent the group means; vertical dashed arrows represent ±95% confidence interval. *Mean value significantly different (*P ≤ 0.05; **P ≤ 0.01) from hypocapnic mean; †significantly different (†P ≤ 0.05; ††P ≤ 0.01) from normocapnic mean. Some symbols have been moved to the left where extensive overlap between points occurred. n = 7 for CB hypocapnia ( = 22.3 ± 2.9 mmHg) and CB hypercapnia (

= 22.3 ± 2.9 mmHg) and CB hypercapnia ( = 68.2 ± 8.3 mmHg), n = 6 for CB normocapnia (

= 68.2 ± 8.3 mmHg), n = 6 for CB normocapnia ( = 41.1 ± 6.1 mmHg). (See text for details.)

= 41.1 ± 6.1 mmHg). (See text for details.)

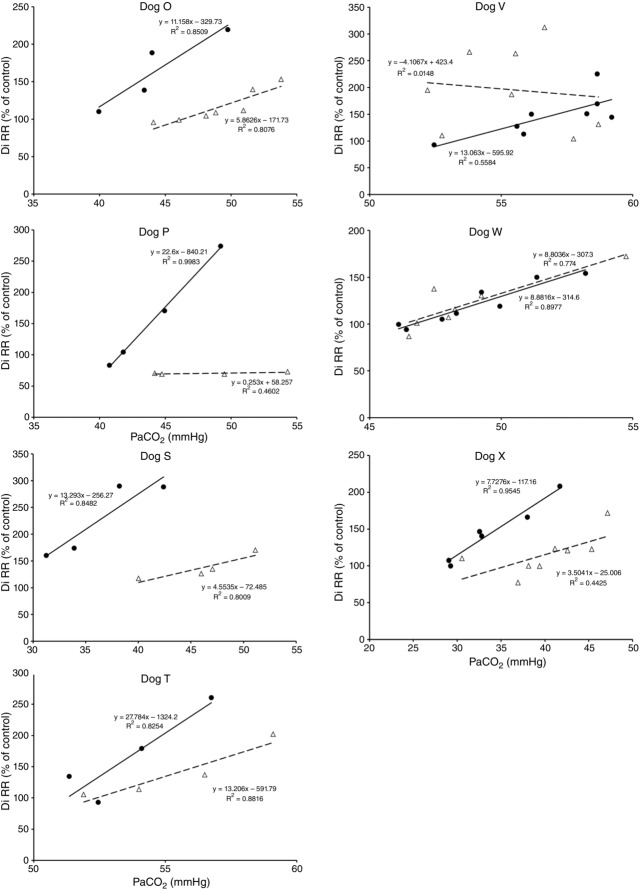

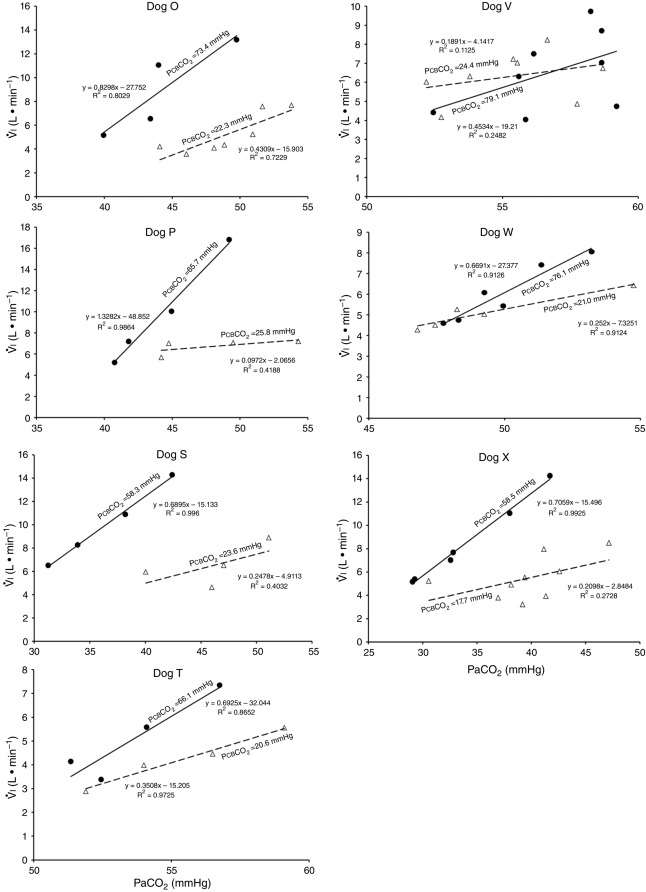

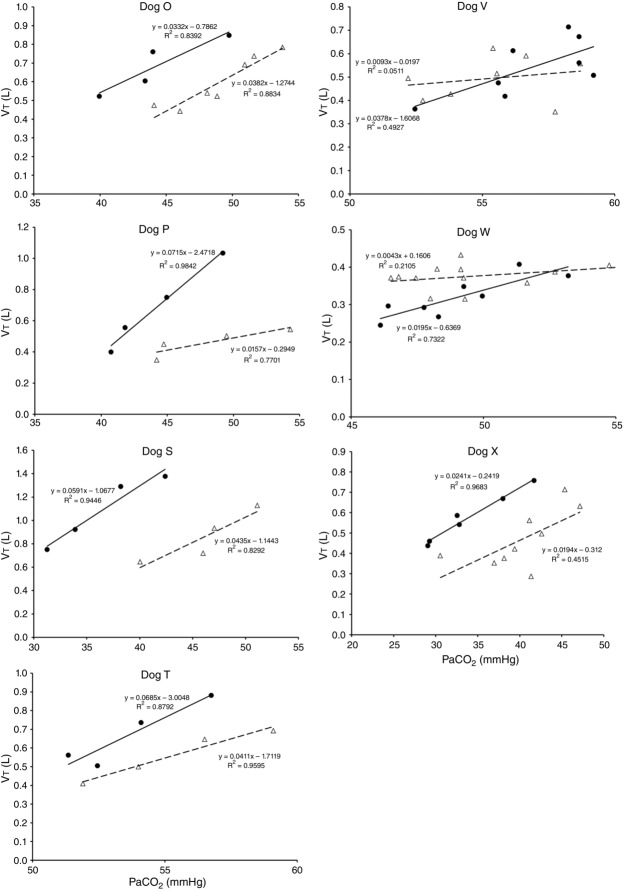

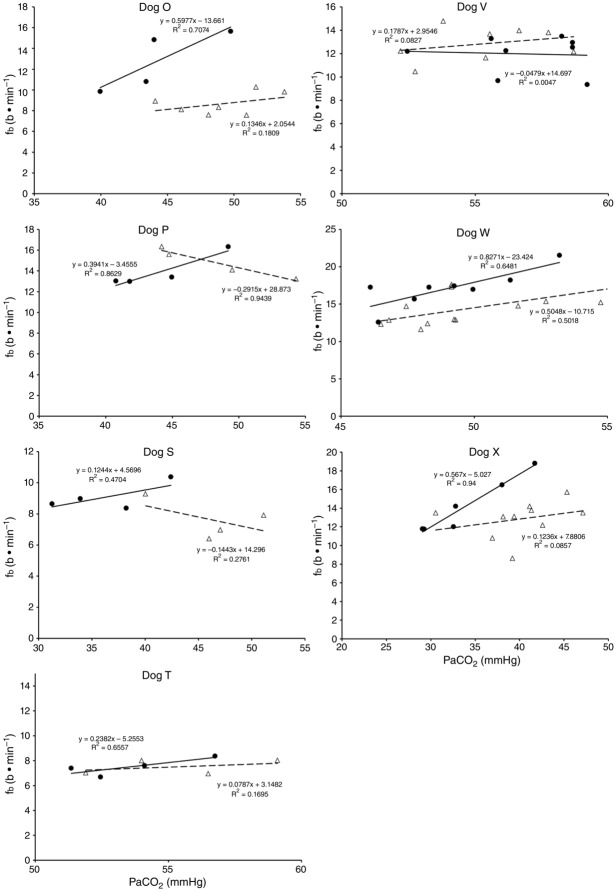

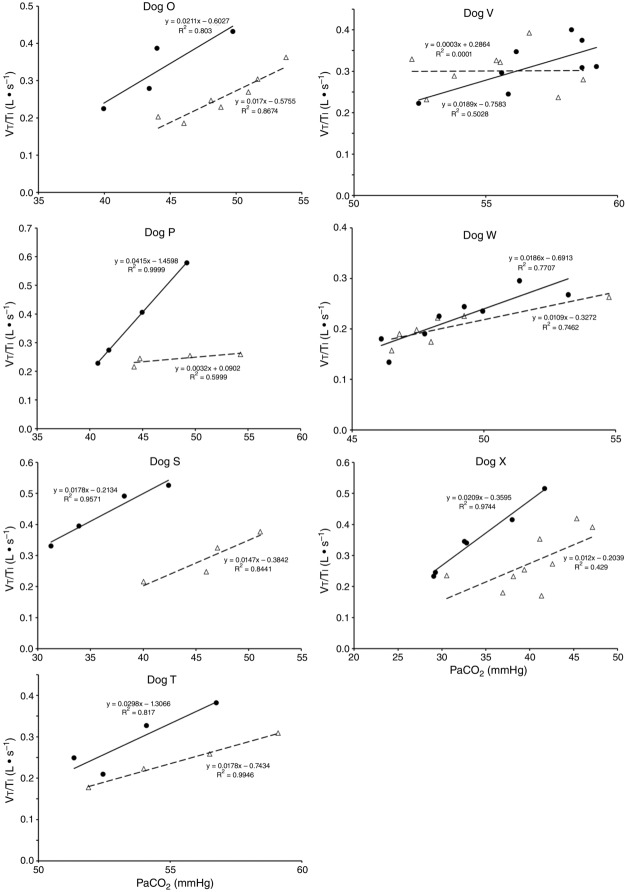

Figures 8 show individual steady-state response slopes to central hypercapnia for five key components of ventilation comparing only the hypercapnic and hypocapnic CB perfusion conditions. These figures make the point that hyperaddition (i.e. hypercapnic CB perfusion ventilatory response slopes steeper than hypocapnic CB perfusion ventilatory response slopes) is a consistent finding in all seven animals for most variables. The slopes of the ventilatory responses to central  during CB hypercapnia are higher than those during CB hypocapnia in 7 of 7 dogs for

during CB hypercapnia are higher than those during CB hypocapnia in 7 of 7 dogs for  and VT/TI and in 6 of 7 dogs for VT, fb, and DiRR. While the ventilatory responses to a ± 20–30 mmHg change in

and VT/TI and in 6 of 7 dogs for VT, fb, and DiRR. While the ventilatory responses to a ± 20–30 mmHg change in  in the CB perfusate elicited steady-state changes in air-breathing

in the CB perfusate elicited steady-state changes in air-breathing  only over a range of ±4.3 mmHg, these changes in CB

only over a range of ±4.3 mmHg, these changes in CB  were accompanied by ±2- to -4-fold changes in the central CO2 responses. Dogs V and W had the lowest and most variable

were accompanied by ±2- to -4-fold changes in the central CO2 responses. Dogs V and W had the lowest and most variable  response slopes to central CO2 and their eupnoeic ventilation showed little or no steady-state response to CB hypo- or hypercapnia. However, as with the other five dogs, V and W showed clear hyperadditive effects of CB hypocapnia vs. CB hypercapnia for most ventilatory components in response to central hypercapnia.

response slopes to central CO2 and their eupnoeic ventilation showed little or no steady-state response to CB hypo- or hypercapnia. However, as with the other five dogs, V and W showed clear hyperadditive effects of CB hypocapnia vs. CB hypercapnia for most ventilatory components in response to central hypercapnia.

Figure 8.

Ventilatory responses of DiRR to increased Fico2 during CB hypercapnic and CB hypocapnic perfusion for each of the seven dogs

Regression equations and r2 values are adjacent to the regression line they pertain to (See text for details). Symbols as in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Ventilatory responses of  to increased Fico2 during CB hypercapnic and CB hypocapnic perfusion for each of the seven dogs

to increased Fico2 during CB hypercapnic and CB hypocapnic perfusion for each of the seven dogs

Regression equations and r2 values are adjacent to the regression line they pertain to. (See text for details.)

Figure 5.

Ventilatory responses of VT to increased Fico2 during CB hypercapnic and CB hypocapnic perfusion for each of the seven dogs

Regression equations and r2 values are adjacent to the regression line they pertain to (See text for details). Symbols as in Figure 4.

Figure 6.

Ventilatory responses of fb to increased Fico2 during CB hypercapnic and CB hypocapnic perfusion for each of the seven dogs

Regression equations and r2 values are adjacent to the regression line they pertain to (See text for details). Symbols as in Figure 4.

Figure 7.

Ventilatory responses of VT/TI to increased Fico2 during CB hypercapnic and CB hypocapnic perfusion for each of the seven dogs

Regression equations and r2 values are adjacent to the regression line they pertain to (See text for details). Symbols as in Figure 4.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Our study was concerned with the nature of the dependence of the ventilatory response to brain (‘central’) hypercapnia on CO2-induced inhibition vs. stimulation of the vascularly-isolated carotid body chemoreceptor in the canine during quiet wakefulness. Using this preparation we determined that the slopes of the mean responses of  , VT, fb, VT/TI and DiRR to increasing steady-state levels of central hypercapnia were increased by 185–462% when the isolated carotid body was hypercapnic relative to when the isolated carotid body was hypocapnic; these changes were statistically significant for

, VT, fb, VT/TI and DiRR to increasing steady-state levels of central hypercapnia were increased by 185–462% when the isolated carotid body was hypercapnic relative to when the isolated carotid body was hypocapnic; these changes were statistically significant for  and VT/TI. These 2- to 4-fold changes in the central CO2 response occurred despite a relatively small range of changes in air-breathing ventilation (Δ

and VT/TI. These 2- to 4-fold changes in the central CO2 response occurred despite a relatively small range of changes in air-breathing ventilation (Δ range −4.3 to +4.3 mmHg) in response to CB hyper-/hypocapnia. These findings demonstrate hyperadditive influences of CO2-induced carotid body stimulation/inhibition on the central ventilatory response to CO2/pH. Significant but smaller increases in the central CO2 responses also occurred between CB hypocapnia and normocapnia but not between CB normocapnia and hypercapnia. These hyperadditive effects between the peripheral and central chemoreceptors are in the same direction as and of similar magnitude to those previously reported in this canine preparation for alterations in (primarily)

range −4.3 to +4.3 mmHg) in response to CB hyper-/hypocapnia. These findings demonstrate hyperadditive influences of CO2-induced carotid body stimulation/inhibition on the central ventilatory response to CO2/pH. Significant but smaller increases in the central CO2 responses also occurred between CB hypocapnia and normocapnia but not between CB normocapnia and hypercapnia. These hyperadditive effects between the peripheral and central chemoreceptors are in the same direction as and of similar magnitude to those previously reported in this canine preparation for alterations in (primarily)  at the carotid chemoreceptor (Blain et al. 2010).

at the carotid chemoreceptor (Blain et al. 2010).

Limitations of our preparation

Perfusate contamination of vertebral artery blood

We have reported previously that our animal preparation has the potential for a portion of the perfusate of the isolated right carotid sinus region to reach the brain via the right vertebral artery after mixing with systemic blood in the brachiocephalic artery (Blain et al. 2010). We note that the right vertebral artery is only one of three major arteries supplying the brain in our preparation; both the left carotid and left vertebral blood flows are not subject to contamination from the carotid body perfusate. We previously established, based on measurements of ∼500 ml · min−1 blood flow in the brachiocephalic artery, that our retrograde perfusion of the right carotid artery at a rate of ∼40–60 ml · min−1 would provide a 5-to10-fold dilution of the perfusate blood available for entry into the right vertebral artery (Blain et al. 2010). In the present study we tested the functional consequences of potential contamination of the central blood supply via the CB perfusate by assessing the ventilatory response to perfusion of the isolated carotid sinus region with markedly hypocapnic or hypercapnic blood in four carotid body denervated animals. We found no consistent effect of these changes in carotid sinus perfusate CO2 on eupnoeic, air-breathing ventilation, breathing pattern, or diaphragmatic EMG (Table1). This lack of response to changes in  in the carotid sinus perfusate contrasts with the substantial effects of an increased systemic

in the carotid sinus perfusate contrasts with the substantial effects of an increased systemic  (via increased

(via increased  ) (Bisgard et al. 1980; Pan et al. 1998; Rodman et al. 2001; Dahan et al. 2007) (also see Results) or reductions in systemic

) (Bisgard et al. 1980; Pan et al. 1998; Rodman et al. 2001; Dahan et al. 2007) (also see Results) or reductions in systemic  (via mechanical ventilation) (Nakayama et al. 2003) on eupnoeic ventilation in the bilaterally CB denervated dog, goat, or human in which the central

(via mechanical ventilation) (Nakayama et al. 2003) on eupnoeic ventilation in the bilaterally CB denervated dog, goat, or human in which the central  would clearly have been influenced by changes in the systemic

would clearly have been influenced by changes in the systemic  . Taken together, we interpret these results to mean that any contamination of vertebral artery perfusion of the brain with our carotid sinus perfusates was insufficient to exert discernible functional effects on ventilation.

. Taken together, we interpret these results to mean that any contamination of vertebral artery perfusion of the brain with our carotid sinus perfusates was insufficient to exert discernible functional effects on ventilation.

Unilateral carotid body denervation

Our animal preparation is awake and intact except for the required denervation of the left carotid body. So the question remains whether our preparation actually responds similarly to a completely intact, awake preparation with both carotid bodies present. Eldridge et al.(1981) showed increased phrenic nerve responses to electrical stimulation of two vs. one carotid sinus nerves in anaesthetized cats and Brooks & Tenney (1966) reported reduced ventilatory responses to hypercapnic-hypoxic combinations in two of three goats following unilateral CBD; there was no change in the third goat.

We compared 26 awake dogs before and after unilateral CBD (see detailed findings in Results). During eupnoeic air-breathing, group mean  was increased modestly but significantly by 2.4 ± 3.5 mmHg following unilateral CBD with no systematic change in the slope of the ventilatory response to increased

was increased modestly but significantly by 2.4 ± 3.5 mmHg following unilateral CBD with no systematic change in the slope of the ventilatory response to increased  . Similarly, Busch et al.(1983) found no difference in the ventilatory response to hypoxia between two different groups of intact vs. unilaterally denervated awake goats. We propose that available findings would support the conclusion that most aspects of chemoreceptor-induced ventilatory control in awake animals with one carotid body are very close to those in the intact animal.

. Similarly, Busch et al.(1983) found no difference in the ventilatory response to hypoxia between two different groups of intact vs. unilaterally denervated awake goats. We propose that available findings would support the conclusion that most aspects of chemoreceptor-induced ventilatory control in awake animals with one carotid body are very close to those in the intact animal.

Variability

On the one hand our use of awake animals ensures that cardiorespiratory response gains to chemoreceptor stimuli are in the physiological range and not subject to ‘neural saturation’ as might be the case in surgically reduced and/or anaesthetized preparations (Eldridge et al. 1981). On the other hand, a limitation of studying the awake animal is that ventilatory responses to hyperpnoeic stimuli are variable – both within and among animals – likely to be attributable at least in part to variable behavioural responses to chemoreceptor and ventilatory stimulation. For example, in 6 of our 7 unilaterally carotid body denervated animals, each with multiple CO2 steady state response tests, we found average coefficients of variation of 24 ± 17%, and 28 ± 11% for the slopes of the ventilatory response to CO2 for  and VT/TI, respectively. Since in our carotid body perfused preparations our CO2 response slopes were obtained from tests conducted over 4–6 days in the same animal, variability would be an important limitation to our ability to detect systematic effects of variations in carotid body

and VT/TI, respectively. Since in our carotid body perfused preparations our CO2 response slopes were obtained from tests conducted over 4–6 days in the same animal, variability would be an important limitation to our ability to detect systematic effects of variations in carotid body  on the central CO2 response. (Also see the Hyperadditive interaction section below.)

on the central CO2 response. (Also see the Hyperadditive interaction section below.)

Effects of changes in systemic

In our isolated carotid body perfused model, as compared to some reduced preparations with isolated perfusions of both carotid body and brain stem (Berkenbosch et al. 1984; Day & Wilson, 2007), our increase in  will acidify all organs exposed to the systemic hypercapnia, not just the ponto-medullary regions. Accordingly, the influence we observed of carotid body

will acidify all organs exposed to the systemic hypercapnia, not just the ponto-medullary regions. Accordingly, the influence we observed of carotid body  on the ‘central’ ventilatory response to CO2 refers to all CO2-sensitive neurons exposed to the systemic circulation.

on the ‘central’ ventilatory response to CO2 refers to all CO2-sensitive neurons exposed to the systemic circulation.

Duration of carotid body chemoreceptor stimulation

Our current and prior studies demonstrated very similar hyperadditive effects of CB stimulation/inhibition on central CO2 ventilatory responses for alterations in either CB  or

or  . However, as summarized in the Introduction, constant or intermittent CB hypoxaemia has been shown to exert quite different effects on ventilation over time from CB hypercapnia. Accordingly, current findings obtained over<30 min of CB hypoxia/hyperoxia or hypercapnia/hypocapnia may not be predictive of their relative influences on central CO2 sensitivity under more chronic conditions.

. However, as summarized in the Introduction, constant or intermittent CB hypoxaemia has been shown to exert quite different effects on ventilation over time from CB hypercapnia. Accordingly, current findings obtained over<30 min of CB hypoxia/hyperoxia or hypercapnia/hypocapnia may not be predictive of their relative influences on central CO2 sensitivity under more chronic conditions.

Hyper-, hypo- and/or additive interaction of peripheral with central chemoreceptors

The long-standing controversy over the nature of central–peripheral chemoreceptor interaction (whether there is hyper-, hypo- and/or additive interaction of peripheral with central chemoreceptors) was recently reviewed (Forster & Smith, 2010; Smith et al. 2010; Guyenet, 2014) and also debated extensively in publications in which three sets of authors defended their positions and suggested new concepts and approaches (Duffin & Mateika, 2013; Teppema & Smith, 2013; Wilson & Day, 2013). Clearly, there are several studies using a wide variety of preparations in animals and also in humans to support additive, hyperadditive, or hypoadditive interactive effects on ventilatory control between peripheral and central chemoreceptors. We now summarize our perception of each of these positions and compare these findings and concepts to our recent and current findings which utilized two different means of stimulation and inhibition of the isolated, perfused carotid sinus region (and, therefore, carotid body chemoreceptor) in the awake canine preparation. We concentrate our analysis on published findings in unanaesthetized preparations and refer the reader to comprehensive recent reviews of this topic (Forster & Smith, 2010; Smith et al. 2010; Guyenet, 2014).

Hypoadditive

Hypoadditive interactive effects between medullary and peripheral chemoreceptors on ventilatory responses to CO2 have been reported consistently primarily in reduced preparations and perhaps most notably in the rat (Day & Wilson, 2007,2009; Tin et al. 2012). The rat preparation has the advantage of including specific, isolated perfusions of the brain stem as well as the carotid chemoreceptor. These preparations have included anaesthesia (Tin et al. 2012) and decerebration as well as ‘reconfigured’ chemosensitive control pathways achieved via removal of vagal, hypothalamic and/or cortical inputs (Day & Wilson, 2007,2009; Guyenet, 2014). In these preparations the ventilatory responses to inhaled CO2 are commonly 10–20% of those in the intact, awake rat of the same strain (Day & Wilson, 2007,2009; Mouradian et al. 2012). We also reported hypoadditive effects of an alkaline CSF perfusate which increased the transient carotid chemoreceptor response to NaCN in the awake goat – but interpretation of this augmented transient response was confounded by a concomitant hypoventilation, CO2 retention and systemic respiratory acidosis (Smith et al. 1984).

Additive

Additive effects between central and peripheral chemoreceptors have been reported primarily (see exception below) in intact humans using methods which rely on separation of the peripheral and central chemoreceptor responses via temporal dissociation of the ‘early’ (peripheral) and ‘late’ (central) responses to inhaled CO2(Clement et al. 1992,1995; St Croix et al. 1996; Cui et al. 2012). We suggest that any determination of the nature of peripheral–central interaction cannot be adequately quantified in these intact preparations because (a) given that an enhanced or reduced sensory input originating in the carotid chemoreceptors is transduced immediately to central CO2-sensitive neurons (Takakura et al. 2006) (i.e. the concept of chemoreceptor interdependence), then precise, complete, temporal separation of the relative responses of the peripheral and central chemoreceptors is not achievable;(b) clear separation of early- and late-phase CO2 responses is not always measurable perhaps because a significant portion of the so-called ‘late’ response to CO2 might be attributed to peripheral (rather than central) chemoreceptors (Pedersen et al. 1999; Dahan et al. 2007); and (c) the likelihood that a short-term potentiation of respiratory motor output (Eldridge & Gill-Kumar, 1980) will follow the initial peripheral chemoreceptor responses to CO2 would seriously confound attempts at assigning response gains exclusively to the different sets of receptors. These limitations indicate to us that quantification of the interdependence between peripheral and central chemoreceptors requires their anatomical isolation.

Hyperadditive

Hyperadditive effects of peripheral chemoreceptor inhibition/stimulation on the central ventilatory CO2 responses have been demonstrated in two types of awake, cortically and vagally intact preparations. First, in several species including dogs, goats, ponies and humans, bilateral CBD (within the initial few days following CBD) results in significant hypoventilation and CO2 retention during air breathing together with a substantial reduction in the slope of either the normoxic or hyperoxic response to systemic hypercapnia (Bisgard et al. 1980; Pan et al. 1998; Rodman et al. 2001; Fatemian et al. 2003; Dahan et al. 2007) or to the ventilatory response to focal medullary acidosis (Hodges et al. 2005). Rats of several strains appear to be exceptions to this evidence for hyperadditive interaction as bilateral CBD in this species results in hypoventilation but without any decrement in the slope of the response to systemic hypercapnia (da Silva et al. 2011; Mouradian et al. 2012; Takakura et al. 2014). On the other hand, it is noteworthy that reductions in the slope of the ventilatory response to CO2 and/or reductions in air-breathing eupnoea observed following partial ablation of central chemosensitive regions in the awake rodent was further reduced in a markedly hyperadditive fashion following denervation or hyperoxic inhibition of the carotid body chemoreceptors (da Silva et al. 2011; Ramanantsoa et al. 2011; Takakura et al. 2014).

The second type of awake preparation with findings that support hyperaddition is found in our essentially intact canine model with isolated, perfused carotid bodies. Combining previous and current findings using this preparation revealed hyperadditive effects on the central CO2 response whether the carotid chemoreceptor was exposed to a combination of hyperoxia and hypocapnia vs. normocapnic hypoxia (Blain et al. 2010) or to normoxic hypercapnia vs. normoxic hypocapnia (present study).

Further support for hyperaddition is provided by experiments in the sleeping canine model utilizing transient hypocapnia. Transient hyperventilation-induced systemic hypocapnia in this model resulted in apnoea and periodic breathing with an apnoeic threshold approximately 5 mmHg below eupnoeic  ; following carotid body denervation the absence of apnoea and periodicity in response to transient hypocapnia showed that CBs were required for the apnoeas to occur (Nakayama et al. 2003). However, hypocapnia applied only to the isolated CB per se, even as much as 10–15 mmHg below eupnoea, did not elicit apnoeas (Smith et al. 1995). Further, systemic (i.e.‘central’) hypocapnia by itself (achieved by means of mechanical ventilation) when the CB chemoreceptor was maintained at constant normocapnia via extracorporeal perfusion also did not elicit apnoea(Smith et al. 2007). Apparently, even a normal ‘tonic’ sensory input from the CB was sufficient to prevent apnoea in the face of marked central hypocapnia in the sleeping animal. These findings in the sleeping canine are consistent with the hyperadditive effects of CB chemoreceptor hypercapnia/hypocapnia on the steady-state central hypercapnic response slopes shown in the present study and suggest that peripheral–central hyperaddition provides an essential contribution to the development of breathing instabilities/periodicities in non-REM sleep in response to transient systemic hypocapnia.

; following carotid body denervation the absence of apnoea and periodicity in response to transient hypocapnia showed that CBs were required for the apnoeas to occur (Nakayama et al. 2003). However, hypocapnia applied only to the isolated CB per se, even as much as 10–15 mmHg below eupnoea, did not elicit apnoeas (Smith et al. 1995). Further, systemic (i.e.‘central’) hypocapnia by itself (achieved by means of mechanical ventilation) when the CB chemoreceptor was maintained at constant normocapnia via extracorporeal perfusion also did not elicit apnoea(Smith et al. 2007). Apparently, even a normal ‘tonic’ sensory input from the CB was sufficient to prevent apnoea in the face of marked central hypocapnia in the sleeping animal. These findings in the sleeping canine are consistent with the hyperadditive effects of CB chemoreceptor hypercapnia/hypocapnia on the steady-state central hypercapnic response slopes shown in the present study and suggest that peripheral–central hyperaddition provides an essential contribution to the development of breathing instabilities/periodicities in non-REM sleep in response to transient systemic hypocapnia.

On the other hand, investigators using a vascularly isolated, perfused carotid body chemoreceptor preparation in the unanaesthetized goat reported additive effects of changes in CB  or

or  on the group mean central CO2 response slopes (Daristotle & Bisgard, 1989; Daristotle et al. 1990). We are not aware of any specific biological differences between these species (or models) that might account for these differences. To the contrary, the awake goat – like most other mammals (see above) – does show markedly reduced ventilatory response slopes to systemic hypercapnia following bilateral CBD, i.e. evidence which would support a hyperadditive effect of carotid body input on the central CO2 response in this species (Pan et al. 1998). So, while we are unable to completely account for these discrepant findings, one potential explanation might be found in the limited ability to detect relatively modest systematic changes in the face of random variations in within-animal CO2 responsiveness as often occurs in awake animals (see Limitations section above). For example, Daristotle & Bisgard (1989) compared their central CO2 response slopes between normoxic vs. hypoxic CB perfusions and reported that half of their animals (3 of 6) increased their central CO2 response slopes when the CB was hypoxic compared to when the CB was normoxic, whereas their remaining three animals showed additive effects. Our current study compared normocapnic, hypocapnic and hypercapnic CB effects on central ventilatory responses to CO2. We observed significant differences for

on the group mean central CO2 response slopes (Daristotle & Bisgard, 1989; Daristotle et al. 1990). We are not aware of any specific biological differences between these species (or models) that might account for these differences. To the contrary, the awake goat – like most other mammals (see above) – does show markedly reduced ventilatory response slopes to systemic hypercapnia following bilateral CBD, i.e. evidence which would support a hyperadditive effect of carotid body input on the central CO2 response in this species (Pan et al. 1998). So, while we are unable to completely account for these discrepant findings, one potential explanation might be found in the limited ability to detect relatively modest systematic changes in the face of random variations in within-animal CO2 responsiveness as often occurs in awake animals (see Limitations section above). For example, Daristotle & Bisgard (1989) compared their central CO2 response slopes between normoxic vs. hypoxic CB perfusions and reported that half of their animals (3 of 6) increased their central CO2 response slopes when the CB was hypoxic compared to when the CB was normoxic, whereas their remaining three animals showed additive effects. Our current study compared normocapnic, hypocapnic and hypercapnic CB effects on central ventilatory responses to CO2. We observed significant differences for  and VT/TI responses between CB hypocapnia and either normocapnia or hypercapnia, but the CB normocapnic vs. CB hypercapnic effects were slightly more variable and non-significant. Thus, our experience would suggest that given the variability of responses to chemoreceptor stimuli in awake animals that multiple comparisons across several levels of CB stimluli might offer the best approach to quantifying central/peripheral interaction effects.

and VT/TI responses between CB hypocapnia and either normocapnia or hypercapnia, but the CB normocapnic vs. CB hypercapnic effects were slightly more variable and non-significant. Thus, our experience would suggest that given the variability of responses to chemoreceptor stimuli in awake animals that multiple comparisons across several levels of CB stimluli might offer the best approach to quantifying central/peripheral interaction effects.

Hybrid models

Given the divergent types of peripheral–central interactions reported to date across many species and preparations it is not surprising that ‘hybrid’ models have been proposed to account for these divergent findings (Nuding et al. 2009; Wilson & Day, 2013; Guyenet, 2014). The finding that different experimental models, ranging from intact humans and animals to anatomically reduced preparations, are producing these divergent findings is not surprising – especially given the markedly ‘reconfigured’ chemoreceptor networks and substantial departures from physiological chemosensitivity present in some of these models (see above). On the other hand, a proposal that the nature of peripheral–central interactions may be critically dependent upon changing ‘physiological states’ and conditions – even within the same experimental preparation – has considerable merit and is especially relevant to interaction effects on ventilatory control (Nuding et al. 2009; Wilson & Day, 2013; Guyenet, 2014). For example, Guyenet (2014) predicts that a key determinant of the type of interaction might be found in the resting membrane potentials of the central CO2-sensitive neurons, which in turn would be influenced by the relative strengths of the inhibitory vs. excitatory input from the respiratory pattern generator, carotid chemoreceptors, and various links within the chemoreceptor pathway. Accordingly, it is suggested that the net effect of these inputs might depend upon such factors as the background states, i.e. wakefulness vs. sleep vs. exercise, prevailing levels of systemic and/or central CO2 and hypoxia, whether ventilatory drive is operating above or below eupnoea, the duration of chemoreceptor stimulation, and the central ‘amplification’ of chemoreceptor input occurring at one or more sites within the medulla, pons, or hypothalamus (Reddy et al. 2005; Schultz & Li, 2007; Nuding et al. 2009; Duffin, 2010; Wilkinson et al. 2010; Wilson & Day, 2013; Dempsey et al. 2014; Guyenet, 2014).

So while future studies may well uncover an effect of one or more of these potential influences on the nature of peripheral chemoreceptor interaction, we propose that current evidence (as described above) is strongly supportive of hyperadditivity as the dominant form of peripheral–central interaction. At present we must limit this proposal to the specific conditions of acute CB inhibition/stimulation (<30 min) during quiet wakefulness or sleep, with ventilation operating within a physiological range either above or below eupnoea, and when the multiple links within the chemosensory control system are anatomically intact, chemosensitivity gains are within the physiological range, and sensory inputs from the carotid chemoreceptors are driven by a wide range of O2 and/or CO2. It is unknown if long-term CB inhibition/stimulation via variations in CB  vs.

vs.  will have similar effects on central–peripheral chemoreceptor ventilatory interaction; this question awaits further study.

will have similar effects on central–peripheral chemoreceptor ventilatory interaction; this question awaits further study.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the outstanding technical contributions of Theodore (Ted) Snyder and Anthony Jacques.

Glossary

- CB

carotid body

- CBD

carotid body denervation

- DiRR

rate of rise of the diaphragm EMG

- EMG

electromyogram

- fb

breathing frequency

fractional inspired CO2

arterial

arterial

carotid body

carotid body

minute ventilation

- VT

tidal volume

- VT/TI

mean inspiratory flow rate

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

C.A.S., G.M.B. and J.A.D. carried out the conception and design of research; C.A.S., G.M.B. and K.S.H. performed the experiments; C.A.S., G.M.B. and K.S.H. analysed the data; C.A.S., G.M.B., K.S.H. and J.A.D. interpreted the results of the experiments; C.A.S. prepared the figures; C.A.S., G.M.B. and J.A.D. drafted the manuscript; C.A.S., G.M.B., K.S.H. and J.A.D. edited and revised the manuscript; C.A.S., G.M.B., K.S.H. and J.A.D. approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants HL50531 and HL15469 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health, and a grant from the American Heart Association.

References

- Berkenbosch A, van Beek JH, Olievier CN, De Goede J. Quanjer PH. Central respiratory CO2 sensitivity at extreme hypocapnia. Respir Physiol. 1984;55:95–102. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(84)90119-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgard GE, Busch MA, Daristotle L, Berssenbrugge AD. Forster HV. Carotid body hypercapnia does not elicit ventilatory acclimatization in goats. Respir Physiol. 1986;65:113–125. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(86)90010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisgard GE, Forster HV. Klein JP. Recovery of peripheral chemoreceptor function after denervation in ponies. J Appl Physiol. 1980;49:964–970. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1980.49.6.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blain GM, Smith CA, Henderson KS. Dempsey JA. Contribution of the carotid body chemoreceptors to eupneic ventilation in the intact, unanesthetized dog. J Appl Physiol. 2009;106:1564–1573. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.91590.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blain GM, Smith CA, Henderson KS. Dempsey JA. Peripheral chemoreceptors determine the respiratory sensitivity of central chemoreceptors to CO2. J Physiol. 2010;588:2455–2471. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.187211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JGI. Tenney SM. Carotid bodies, stimulus interaction, and ventilatory control in unanesthetized goats. Respir Physiol. 1966;1:211–224. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(66)90018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch MA, Bisgard GE, Mesina JE. Forster HV. The effects of unilateral carotid body excision on ventilatory control in goats. Respir Physiol. 1983;54:353–361. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(83)90078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement ID, Bascom DA. Robbins PA. An assessment of central-peripheral ventilatory chemoreflex interaction in humans. Respir Physiol. 1992;88:87–100. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(92)90031-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement ID, Pandit JJ, Bascom DA, Dorrington KL, O’Connor DF. Robbins PA. An assessment of central-peripheral ventilatory chemoreflex interaction using acid and bicarbonate infusions in humans. J Physiol. 1995;485:561–570. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Z, Fisher JA. Duffin J. Central-peripheral respiratory chemoreflex interaction in humans. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2012;180:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran AK, Rodman JR, Eastwood PR, Henderson KS, Dempsey JA. Smith CA. Ventilatory responses to specific CNS hypoxia in sleeping dogs. J Appl Physiol. 2000;88:1840–1852. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.5.1840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva GS, Giusti H, Benedetti M, Dias MB, Gargaglioni LH, Branco LG. Glass ML. Serotonergic neurons in the nucleus raphe obscurus contribute to interaction between central and peripheral ventilatory responses to hypercapnia. Pflugers Arch. 2011;462:407–418. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-0990-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan A, Nieuwenhuijs D. Teppema L. Plasticity of central chemoreceptors: effect of bilateral carotid body resection on central CO2 sensitivity. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e239. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daristotle L, Berssenbrugge AD, Engwall MJ. Bisgard GE. The effects of carotid body hypocapnia on ventilation in goats. Respir Physiol. 1990;79:123–135. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(90)90012-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daristotle L. Bisgard GE. Central-peripheral chemoreceptor ventilatory interaction in awake goats. Respir Physiol. 1989;76:383–391. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(89)90078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

-

Day TA. Wilson RJ. Brainstem