Abstract

Tumor metastasis is not only a sign of disease severity but also a major factor causing treatment failure and cancer-related death. Therefore, studies on the molecular mechanisms of tumor metastasis are critical for the development of treatments and for the improvement of survival. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is an orderly, polygenic biological process that plays an important role in tumor cell invasion, metastasis and chemoresistance. The complex, multi-step process of EMT involves multiple regulatory mechanisms. Specifically, the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway can affect the EMT in a variety of ways to influence tumor aggressiveness. A better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms related to the EMT can provide a theoretical basis for the early prediction of tumor progression as well as targeted therapy.

Keywords: anti-cancer therapy, EMT, extracellular matrix, PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, transcription factors, tumor aggressiveness

Abbreviations

- EMT

epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PKB

protein kinase B

- PDK1

3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1

- CK

cytokeratin

- bHLH

basic helix-loop-helix protein

- YB-1

Y-box binding protein-1

- MET

mesenchymal-epithelial transition

- GSK-3β

glycogen synthase kinase 3 β

- ILK

integrin-linked kinase

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor-β

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- MDR

multidrug resistance

Introduction

Due to changes in living environments as well as human habits, increasing numbers of patients continue develop and die from cancer. However, tumor cell invasion and metastasis are the primary causes of malignant tumor-related death.1 A large number of studies on tumor metastasis have been conducted; however, the exact mechanism of metastasis remains unclear. Thus, further explorations of the molecular mechanisms that are associated with the metastatic process are essential. Tumor metastasis is a continuous multi-step process that includes a reduction in cell adhesion, the perforation of the basement membrane, the migration of tumor cells into blood circulation, the avoidance of immune surveillance, and finally, the colonization of tumor cells at distant sites.2 The EMT is one of the most important mechanisms in the initiation and promotion of tumor cell metastasis.3

The EMT is a phenomenon that refers to the transition of differentiated epithelial cells to mesenchymal cells in specific physiological and pathological conditions. In pathological conditions, the EMT is related to the development of chronic diseases such as organ fibrosis and Crohn's disease as well as the invasion and metastasis of tumors of epithelial cell origin.4,5 This process is accompanied by alterations in cell morphology, cell-cell adhesion, the activity of cellular signaling pathways, and the extracellular matrix. Therefore, tumor cells are capable of invasion into the surrounding environment and eventually distant sites through blood and lymph.6

The phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathway plays an important role in regulating cell proliferation and maintaining the biological characteristics of malignant cells.7 PI3K is a heterodimer consisting of a regulatory subunit, p85, and a catalytic subunit, p110. It is ubiquitous in the cytoplasm in the resting state, and both phosphatidylinositol kinase and serine/threonine protein kinase are important players in the pathway. Akt is a protein kinase encoded by a homolog of intracellular retrovirus. Due to its high level of homology with protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC), Akt is also known as protein kinase B (PKB). PI3K can be activated by tyrosine kinase to generate PIP3 in the plasma membrane. Then, PIP3 interacts with the PH domain of Akt to cause aggregation of Akt at the membrane. Then, with the aid of 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1), Thr308 of Akt will be phosphorylated, leading to activation of Akt. Activated Akt will then phosphorylate a series of substrates, thereby affecting a variety of cellular and physiological processes, including the cell cycle, cellular growth, differentiation, survival, apoptosis, metabolism, angiogenesis and migration.8 These changes may induce the EMT.

The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway mediates the process of EMT and has attracted widespread attention as a potential target for the prevention and treatment of metastatic tumors.9,10 This review investigated the regulatory mechanisms of EMT, which are strongly related to the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway and the role of EMT in cancer treatment. The elucidation of the relevant regulatory mechanisms is beneficial for the discovery of new molecular markers of tumor recurrence and prognosis as well as for the discovery of novel targets for gene therapy and drug development.

Characteristics of EMT

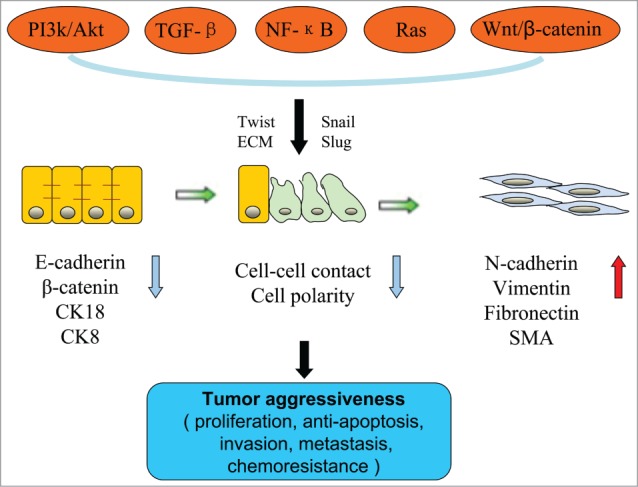

The EMT can be divided into 3 types according to the biological environment, relevant functions and regulatory mechanisms. Type I is related to implantation, embryogenesis and the development of organs; the transformed mesenchymal cells can form new epithelial tissues. Type II is involved in wound healing, tissue reconstruction, tissue regeneration and organ fibrosis. This type can be initiated by inflammatory stimulation and ends when the stimulation disappears; persistent stimulation can lead to organ fibrosis and tissue reconstruction.11 Type III plays an important role in the development and metastasis of cancer and can induce the transformation of epithelial cells into mesenchymal cells.12-13 As a transient, reversible process, the primary features of this type of EMT include the following (Fig. 1): (1) Changes in cellular morphology when epithelial cells lose polarity and transform into mesenchymal cells with long spindle shapes and a dispersed arrangement14 and (2) changes in the expression of proteins with a decrease in epithelial cell markers, such as E-cadherin, β-catenin, cytokeratin (CK) 8 and CK18, and an increase in the expression of mesenchymal cell markers, such as N-cadherin, vimentin, fibronectin, and SMA, among others.15 E-cadherin is a characteristic marker of epithelial cells.20 Reduced expression of E-cadherin induces the remodeling of cytoskeletal proteins and leads to decreased intercellular adhesion. This process is regulated by a variety of factors within the tumor cells, including basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins, Snail, Slug and others.16-18 After stimulation by these inducible factors, a series of chain reactions occurs, which results in enhanced cellular mobility and invasion.19 Another feature of this type of EMT is (3) changes in the biological behavior of the cell when epithelial cells lose their interactions with each other and transform into mesenchymal cells with a high capacity for invasion.20 Protein-dissolving enzymes are able to degrade the basement membrane so that cells can invade the extracellular matrix; the cells thereby obtain a strong capacity for invasion and metastasis and escape from apoptotic death. Although not all cells that undergo EMT will also undergo the above 3 changes, the ability to migrate is a feature of all types of EMT.

Figure 1.

The characteristics, regulators and effects of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). The EMT is an orderly process whereby epithelial cells lose their phenotype and gradually acquire the phenotype of mesenchymal cells. This process is accompanied by changes in the physical contacts between cells as well as in cellular polarity, cellular morphology, and biomarkers. The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway cooperates with other signaling pathways, either directly or indirectly, to induce the EMT. This results in enhanced tumor aggressiveness, including proliferation, apoptosis resistance, invasion, metastasis and chemoresistance.

The PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway is Involved in the Direct Induction of EMT

PI3K/Akt and transcription factors

Twist is a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor with a strong ability to induce the EMT, and there are 2 Twist family members: Twist1 and Twist2. Twist often acts as a transcriptional activator to increase the expression of N-cadherin, Bmi1, Akt2, and Y-box binding protein-1 (YB-1).21-23 Twist expression is positively correlated with the degree of infiltration and with lymphatic and distant metastasis; in addition, cancer patients with high Twist expression exhibit lower 5-year survival rates, suggesting that Twist may be a useful marker for evaluating the prognosis of gastric cancer.24,25 Vichalkovski examined the interaction between Twist and Akt and found that activated Akt upregulated the expression of phosphorylated Twistl and subsequently alleviated the induction of p53 caused by chemotherapy-induced DNA damage, resulting in the inhibition of apoptosis.26 Moreover, the levels of Twist and phosphorylated Akt are also positively correlated in oral squamous cell carcinoma.27 When oral cancer cells, which typically exhibit sustained Akt activation and low E-cadherin expression, were treated with an Akt inhibitor, Snail and Twist expression decreased. This decreased expression subsequently promoted E-cadherin expression, reduced vimentin expression, restored the cells' polygonal shape, and stimulated the mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET).28,29 Twist expression was suppressed after the inhibition of Akt activity in prostate cancer cells.30 However, Twist can also have a significant effect on Akt signaling pathway activation.31 Twist induced the expression of miR-10b and subsequently promoted the phosphorylation of Akt, thereby increasing the invasiveness of gastric cancer cells.32 Kim et al.33 also found that periostin protein could modulate the Akt signaling pathway in bladder cancer via Twist. Twist can enhance the biological activity of Akt, mainly through interaction with the E-box element in the Akt2 promoter. Akt2 is a crucial factor in the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, as it regulates cell proliferation, differentiation and survival in physiological and pathological processes.34 Numerous studies indicate that Akt2 functions downstream of Twist and can regulate Twist function. Some studies have confirmed that Twist upregulates the expression of the Akt2 gene, and Twist-Akt2 is involved in the invasiveness and drug resistance of breast cancer.35 Silencing of Akt2 could reduce Twist-induced tumor cell metastasis, invasion and resistance to paclitaxel.36 Thus, Akt and Twist are involved in a positive feedback loop, which results in a series of events that enhance their pro-EMT function.

Snail and Slug are DNA binding proteins with zinc finger structures that belong to the same transcription factor family. Snail and Slug can shuttle between the cytoplasm and the nucleus to locate an E-box that serves as the promoter upstream of E-cadherin; these proteins then bind to the E-box area and inhibit the expression of the E-cadherin gene, thereby triggering the EMT.37 The location of Snail in the nucleus affects the transcription of β-catenin and also increases the expression of vimentin, fibronectin, MMP-2 and MMP-9.38,39 The regulation of Snail by the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway is a complex process that involves multiple mechanisms of regulation. On the one hand, PI3K/Akt can inhibit the degradation of Snail. For example, the activation of PI3K/Akt can phosphorylate the 9th residue of glycogen synthase kinase 3 β (GSK-3β). This process facilitates GSK-3β ubiquitination and subsequent degradation; thus, GSK-3β can no longer participate in the degradation of Snail.40 On the other hand, the activation of PI3K/Akt can directly upregulate the intracellular expression of Snail. Hong et al.28 used an Akt inhibitor to treat oral cancer cells that exhibited continuous Akt activation and low E-cadherin expression. This treatment led to decreased Snail expression at both the transcriptional and translational levels as well as the appearance of epithelial phenotypes. Slug is also an important molecule in the EMT in cancer cells.41 Slug overexpression in breast cancer can simultaneously downregulate E-cadherin, CK8, and CK9. When Slug is silenced in prostate cells, cellular proliferation is inhibited, the cell cycle is arrested at the G0 to G1 phase, and expression of integrins α6 and β4, which form an adhesion receptor for extracellular matrix (ECM) components, are suppressed at both the transcriptional and translational levels.42 A report demonstrated that phosphorylated Akt expression is positively correlated with Slug expression and negatively correlated with E-cadherin expression in endometrial cancer.43 GSK-3β degradation after PI3K/Akt activation therefore leads to Slug overexpression followed by the induction of the EMT.44

PI3K/Akt and integrin-linked kinase

Integrin-linked kinase (ILK) is a serine-threonine protein kinase that binds to the β integrin cytoplasmic domain. ILK mediates downregulation of E-cadherin, which leads to the EMT.45 Delcommenne et al.46 reported that after cells were transfected with activated P13K, ILK activity was significantly increased compared with the control group; however, when cells were transfected with inactivated P13K, ILK-mediated activation of its downstream factor was significantly reduced. Recent research indicates that P13K is involved in the ILK-induced EMT process; thus, the addition of LY294002 can inhibit the process. The mechanism likely involves P13K-mediated enhancement of ILK activity and its downstream factors GSK3 and LEF-I.47

PI3K/Akt and ECM

ECM, matrix-degrading proteases, and ECM receptors participate in the regulation of cell function, including cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, migration, and invasion. During the EMT, tumor cells degrade their basement membrane and gain access into the matrix by extending pseudopodia. Matrix-degrading proteases are required for EMT for the following reasons. These proteases degrade the basement membrane and interstitial matrix, thereby providing a path for tumor cell invasion; promote the release and activation of cytokines that bind to the extracellular matrix; and split the extracellular domain of E-cadherin.48,49 MMPs are an important family among matrix-degrading proteases. The activity of MMP2 and the amount of secreted MMP9 are related to the extent of EMT.50 In head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, the activation of PI3K/Akt increases MMP9 expression, degrades E-cadherin, and promotes cell invasion and migration.51 The inhibition of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in gastric cancer blocked MMP9 activation. In addition, the EMT triggered by Sonic hedgehog was also reduced.52 Moreover, MMP9 activation is also relevant to the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in tumor necrosis factor-induced EMT in renal cancer cells.53

PI3K/Akt Induces the EMT Through Cooperation with Other Signaling Pathways

Intracellular signal transduction is a complex network. PI3K/Akt proteins can also cooperate with other signaling pathways, such as TGF-β, NF-κB, Ras, and Wnt/β-catenin, to induce the EMT either directly or indirectly (Fig. 1).

PI3K/Akt and the TGF-β signaling pathway

The EMT requires the activation of cytokines, such as platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α).12 Among these, TGF-β is known to be the most potent EMT-inducing agent. TGF-β is produced by macrophages, stromal cells, and tumor cells. TGF-β can inhibit cell proliferation, induce apoptosis, and regulate cellular autophagy. In the early stage of the neoplastic process, TGF-β is an important factor inhibiting the primary tumor; however, in the late stage of the neoplastic process, it promotes the release of cytokines, induces the EMT, stimulates angiogenesis and inhibits immune surveillance.54,55

Bakin et al.9 reported that P13K/Akt activation was essential to the EMT process induced by TGF-β1 in tumor cell lines. The addition of LY294002, a P13K inhibitor, suppresses this process. Hofmann et al.56 used TGF-β to stimulate primary hepatocytes in mice and demonstrated induction of the EMT and the activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Moreover, BMP-2, a member of the TGF-β superfamily, induces EMT in pancreatic cancer cells; this induction was also dependent on the activation of Akt.57 The mechanism by which TGF-β1 activates the P13K/Akt signaling pathway remains controversial. In addition to the direct activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway by the RhoA signaling pathway, TGF-β can also affect the expression of EGF and induce the intracellular localization of EGFR; this action in turn activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway.58,59 The activation of AKT regulates the phosphorylation of Twist, promotes the transcription of TGF-β2 and activates TGF-β receptors. However, the activation of the latter can induce excessive PI3K/Akt signaling pathway activity, which further provides positive feedback for the induction of EMT.60

PI3K/Akt and the NF-κB signaling pathway

NF-κB also participates in the induction of EMT by PI3K/Akt. Maier et al.61 reported that EMT can occur even in the absence of TGF-β in breast cancer cells with sustained NF-κB activation. The enhanced activity of PDK and P13K promote the activation of Akt and increased expression of the NF-κB subunit p65. Moreover, Arsura et al.62 blocked NF-κB in Ha-RaS, a type of mammary epithelial cell, and injected these cells into nude mice. They found a significantly diminished cellular capability for tumor formation and metastasis. The specific mechanism is as follows: Ras activates the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, which then reactivates NF-κB to induce the expression of Snail; this in turn leads to the downregulation of E-cadherin expression.63

PI3K/Akt and the tyrosine kinase receptor signaling pathway

Ras is a key tyrosine kinase receptor within the tyrosine kinase receptor signaling pathway. The activation of the Ras/Akt signaling pathway is not only associated with malignancy in epithelial cells but can also promote changes (such as the EMT). One study found that Akt and ERK were activated after the transfection of a mutant Ras gene into murine mammary epithelial cells; therefore, the cells acquired a tumorigenic capacity and underwent EMT-like changes.64 Liao et al.65 found that PDGF lost the capacity to activate Akt after knockdown of the K-Ras gene in mouse fibroblasts. In this scenario, the cells could not secrete MMP2, and PDGF was not able to promote cell migration. However, the addition of exogenous K-Ras restored the PDGF-driven activation of Akt as well as its pro-EMT effects.

PI3K/Akt and the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

The Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is also known as typical Wnt signaling pathway. β-catenin combines with intracellular domain of E-cadherin to form a complex. The complex subsequently connects to the actin cytoskeleton, mediates intercellular adhesion, and regulates tumor cell invasion and metastasis. When exogenous Wnt combines with Frizzled, Dsh/Dvl proteins are activated to inhibit the phosphorylation of β-catenin by GSK3R/APC/AXIN. β-catenin levels increase sharply in the cytoplasm, where it can enter the nucleus and bind with TCF/LEF. This binding leads to the activation of target genes that induce EMT.66 The PI3K/Akt pathway positively regulates Wnt/β-catenin in 2 different manners, both of which contribute to the induction of EMT. The first mechanism involves the movement of β-catenin into the nucleus, which is typically accompanied by Akt phosphorylation. Activated Akt then phosphorylates the serine at residue 552 in β-catenin, which increases its transcriptional activity.67 In the second mechanism, GSK3β simultaneously degrades β-catenin and Snail. The excessive activation of Akt results in the phosphorylation of the serine at residue 9 in GSK3β, which facilitates the ubiquitination and degradation of GSK3β.68 The activation of Akt then increases intracellular β-catenin levels.

Role of EMT in Chemoresistance and Anti-cancer Therapy

The correlation between EMT and chemoresistance

Tumor cells with mesenchymal properties often exhibit primary resistance.69 The EMT has been increasingly considered to represent a new and crucial mechanism of drug resistance.70 Initial studies revealed that colon cancer cell lines with resistance to oxaliplatin presented characteristics of long fusiform cell processes, the loss of polarity, cell separation, the formation of pseudopods, the decreased expression of E-cadherin and the increased expression of vimentin.71,72 Subsequently, Snail, Twist, MMP-2 and membrane-type-1-MMP were found to be increased in ovarian cancer cell lines with resistance to paclitaxel. Following this discovery, another study found that doxorubicin can induce the EMT in breast cancer cells in vitro; moreover, the authors demonstrated that did the cells tended to possess the enhanced capacity for invasion and metastasis as well as the acquisition of multidrug resistance (MDR) only during the EMT.73 The phenomenon of EMT was also observed in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cell lines, gemcitabine-resistant and cisplatin-resistant pancreatic cancer cell lines, and 5-FU-resistant breast cancer, colon cancer and pancreatic cancer cell lines.74-78 Overall, these studies indicate the close relationship between EMT and chemoresistance.

Targeting the EMT for anti-cancer therapy

In the process of EMT, there is a strong link among alterations in the cell phenotype, related signaling pathways and transcription factors during the tumor response to chemotherapy. On one hand, EMT and chemoresistance share many common regulatory pathways. Activation and disorders of EMT-related signaling pathways play a synergistic role in the regulation of drug resistance in tumors, mainly functioning with the P13K/Akt signaling pathway and its partners TGF-β, NF-κB, Ras, and the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. On the other hand, under the regulation of the PI3K/Akt and related signaling pathways, EMT-related transcription factors (Zebl and Slug) have key regulatory roles in anti-tumor drug resistance. Inhibiting the activity of EMT-related transcription factors weakens their abilities to regulate downstream factors and may reverse the mesenchymal state of drug-resistant cells as well as their sensitivity to anti-cancer therapies.

First, given the key role of the above signaling pathways in the EMT, the inhibition of these signal transduction pathways is regarded as a new tool in anti-cancer therapy. For example, redford is one of the most mature Akt inhibitors. This inhibitor can block the combination of PI3K and Akt and has been used in Phase II clinical trials alone or as a joint treatment for various tumor types to treat drug-resistant cancer cells. Fujiwara also employed the PI3K inhibitor LY294002 and cisplatin to treat pancreatic cancer.79 The pancreatic cancer cells then became more sensitive to cisplatin compared with the control group. The in vitro application of wortmannin to inhibit the activity of Akt suppressed the malignant potential of glioma cells, ovarian cancer cells, and pancreatic cancer cells.

Sulindac exhibits anti-tumor effects and can inhibit the Wnt signaling pathway via the downregulation of β-catenin in colon carcinoma; sulindac can also drive the downregulation of cyclin D1.80,81 In a mouse model of pulmonary metastasis from breast cancer, the inhibition of the Wnt signaling pathway by LRP6 reduced the number of tumor stem cells and reversed EMT; therefore, the epithelial phenotype of the cells was restored.82 Some scholars reported that cyclopamine, a specific blocker of the Hh signaling pathway, can effectively block the transcription of Gli1 mRNA to significantly weaken cellular invasiveness and adhesive ability.83 Zhang et al.84 found that the new Hh inhibitor CUR-0199691 possesses an inhibitory function against breast cancer cells. Other studies have reported that dexamethasone can inhibit the TGF-induced EMT and the migration of cells, which prevents tumor metastasis.85 Additionally, glucocorticoids can regulate the body's immune functions and thereby suppress tumorigenesis. However, dexamethasone should be used with caution due to the serious adverse reactions associated with this drug. Some studies have shown that doxorubicin is able to induce Twist, which can mediate the EMT, multidrug resistance and tumor invasion in MCF-7 breast cancer cells.73 Moreover, the small interfering RNA-mediated silencing of Twist can significantly reduce doxorubicin-related resistance and decrease p53 activity.

Second, suppression of EMT-related transcription factors is beneficial for recovering the sensitivity of drug-resistant cells to chemotherapy.86 Recent findings indicate an important role for Zeb1 (an EMT-related transcription factor) in the recovery of histone deacetylation to promote the downregulation of E-cadherin in human pancreatic cancer.87 However, MS-275, an inhibitor of histone deacetylation, is able to inhibit this action and increase the expression of E-cadherin, inducing the resistant cells to adopt characteristics of epithelial cells and inducing the reversal of the EMT in these cells.88 This effect has been demonstrated to be effective in the reversal of resistance to gefitinib and gemcitabine, and this drug is currently part of a Phase I clinical trial. Additionally, the EMT-related transcription factor Slug contributes to the acquisition of resistance to gefitinib. Silencing of the Slug gene can reverse the mesenchymal characteristics and the sensitivity of cells to gefitinib.89 MDR of tumor cells is often accompanied by EMT. Multidrug-resistant tumor cells with high P-gp expression often exhibit a strong capacity for invasion and metastasis.90 Notably, the activation of the PI3K/Akt and MAPK signaling pathways can upregulate the expression of P-gp, which may lead to MDR.91,92 This shows that these common signaling pathways may be involved in the pathogenesis of both the EMT and MDR. Additionally, P-gp and the ATP-binding cascade transporter protein are governed by Snail and Twist.93,94 These points further illustrate that EMT and MDR may have common regulatory mechanisms.95

Concluding Remarks

The EMT is not only an essential physiological process during embryonic development but is also an important process in tumor invasion and metastasis. An in-depth study on the role of EMT-related signal transduction pathways and multiple transcription factors in tumor growth, invasion and metastasis will provide a favorable platform for the prevention and treatment of cancer. However, many issues remain to be clarified. For example, this article discusses EMT-related biomarkers, but these biomarkers have certain limitations with respect to the indication of EMT in vivo. This is because the expression patterns of the above markers are not maintained at the same level in different tumor cell states. For example, Wei et al.96 reported a lack of vimentin expression in tumor cells in the primary lesion, whereas vimentin was detected in tumor cells that had invaded the blood vessels or the bone marrow. Therefore, better markers or methods to identify the EMT in vivo are needed.

Regarding tumor treatment, although the role of the EMT in chemoresistance provides one avenue of addressing drug resistance, many other issues have yet to be resolved. Likewise, it is unclear whether the utilization of EMT-related signaling pathways as targets for the reversal of chemoresistance can achieve the desired therapeutic effect. Additionally, despite advances in the development of drugs that target EMT-related regulatory mechanisms, these drugs continue to lack specificity; they also possess hepatotoxicity, myelosuppression or other side effects. Moreover, some drugs block the transcription of downstream molecules in these signaling pathways to activate other signaling pathways through feedback, which may then stimulate other tumor-related biological activity. Further, current studies on EMT-related regulatory mechanisms primarily perform in vitro experiments. It is necessary to explore EMT in vivo for a better understanding of its effects on tumor invasion and metastasis. Therefore, research on the EMT faces significant challenges in this field, and substantial research must be conducted to develop highly specific, low-toxicity drugs that are targeted to EMT-related regulatory mechanisms.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Projects for “Major New Drugs Innovation and Development” (China; No. 2011ZX09302-007-03), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Number: 81060038;81460377), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province, China (20142BAB215036), the Science and Technology Foundation of the Department of Education of Jiangxi Province, China (GJJ14169), and the “Talent 555 Project” of Jiangxi Province, China.

References

- 1.Friedl P, Wolf K. Plasticity of cell migration: a multiscale tuning model. J Cell Biol 2010; 188:11-9; PMID:19951899; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200909003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwatsuki M, Mimori K, Yokobori T, Ishi H, Beppu T, Nakamori S, Baba H, Mori M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer development and its clinical significance. Cancer Sci 2010; 101:293-9; PMID:19961486; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01419.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talbot LJ, Bhattacharya SD, Kuo PC. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, the tumor microenvironment, and metastatic behavior of epithelial malignancies. Int J Biochem Mol Biol 2012; 3:117-36; PMID:22773954 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee SJ, Kim KH, Park KK. Mechanisms of fibrogenesis in liver cirrhosis: The molecular aspects of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. World J Hepatol 2014; 6:207-16; PMID:24799989; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4254/wjh.v6.i4.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Xiao Y, Ge W, Zhou K, Wen J, Yan W, Wang Y, Wang B, Qu C, Wu J, et al.. miR-200b inhibits TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and promotes growth of intestinal epithelial cells. Cell Death Dis 2013; 4:e541; PMID:23492772; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cddis.2013.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamouille S, Subramanyam D, Blelloch R, Derynck R. Regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal and mesenchymal-epithelial transitions by microRNAs. Curr Opin Cell Biol 2013; 25:200-7; PMID:23434068; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lunardi A, Webster KA, Papa A, Padmani B, Clohessy JG, Bronson RT, Pandolfi PP. Role of aberrant PI3K pathway activation in gallbladder tumorigenesis. Oncotarget 2014; 5:894-900; PMID:24658595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye B, Jiang LL, Xu HT, Zhou DW, Li ZS. Expression of PI3K/AKT pathway in gastric cancer and its blockade suppresses tumor growth and metastasis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2012; 25:627-36; PMID:23058013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakin AV, Tomlinson AK, Bhowmick NA, Moses HL, Arteaga CL. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase function is required for transforming growth factor beta-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cell migration. J Biol Chem 2000; 275:36803-10; PMID:10969078; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M005912200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu Q, Ma J, Lei J, Duan W, Sheng L, Chen X, Hu A, Wang Z, Wu Z, Wu E, et al.. alpha-Mangostin suppresses the viability and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic cancer cells by downregulating the PI3K/Akt pathway. Biomed Res Int 2014; 2014:546353; PMID:24812621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pinzani M. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in chronic liver disease: fibrogenesis or escape from death? J Hepatol 2011; 55:459-65; PMID:21320559; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Araki K, Shimura T, Suzuki H, Tsutsumi S, Wada W, Yajima T, Kobayahi T, Kubo N, Kuwano H. E/N-cadherin switch mediates cancer progression via TGF-beta-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Cancer 2011; 105:1885-93; PMID:22068819; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/bjc.2011.452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest 2009; 119:1420-8; PMID:19487818; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI39104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackenzie IC. Stem cell properties and epithelial malignancies. Eur J Cancer 2006; 42:1204-12; PMID:16644206; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galvan JA, Astudillo A, Vallina A, Fonseca PJ, Gomez-Izquierdo L, Garcia-Carbonero R, Gonzalez MV. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers in the differential diagnosis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Am J Clin Pathol 2013; 140:61-72; PMID:23765535; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1309/AJCPIV40ISTBXRAX [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siemens H, Jackstadt R, Hunten S, Kaller M, Menssen A, Gotz U, Hermeking H. miR-34 and SNAIL form a double-negative feedback loop to regulate epithelial-mesenchymal transitions. Cell cycle 2011; 10:4256-71; PMID:22134354; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.10.24.18552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu YN, Abou-Kheir W, Yin JJ, Fang L, Hynes P, Casey O, Hu D, Wan Y, Seng V, Sheppard-Tillman H, et al.. Critical and reciprocal regulation of KLF4 and SLUG in transforming growth factor beta-initiated prostate cancer epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Mol Cell Biol 2012; 32:941-53; PMID:22203039; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1128/MCB.06306-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu KJ, Yang MH. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stemness: the Twist1-Bmi1 connection. Biosci Rep 2011; 31:449-55; PMID:21919891; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1042/BSR20100114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mani SA, Guo W, Liao MJ, Eaton EN, Ayyanan A, Zhou AY, Brooks M, Reinhard F, Zhang CC, Shipitsin M, et al.. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 2008; 133:704-15; PMID:18485877; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenburg G, Hay ED. Epithelia suspended in collagen gels can lose polarity and express characteristics of migrating mesenchymal cells. J Cell Biol 1982; 95:333-9; PMID:7142291; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.95.1.333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang MH, Hsu DS, Wang HW, Yang WH, Kao SY, Tzeng CH, Tai SK, Chang SY, Lee OK, Wu KJ. Bmi1 is essential in Twist1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat. Cell Biol 2010; 12, 982-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang TM, Hung WC.Transcriptional repression of TWIST1 gene by Prospero-related homeobox 1 inhibits invasiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. FEBS Lett 2012; 586:3746-52; PMID:22982861; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.08.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shiota M, Izumi H, Onitsuka T, Miyamoto N, Kashiwagi E, Kidani A, Yokomizo A, Naito S, Kohno K. Twist promotes tumor cell growth through YB-1 expression. Cancer Res 2008; 68:98-105; PMID:18172301; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kwon MJ, Kwon JH, Nam ES, Shin HS, Lee DJ, Kim JH, Rho YS, Sung CO, Lee WJ, Cho SJ. TWIST1 promoter methylation is associated with prognosis in tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma. Hum Pathol 2013; 44:1722-9; PMID:23664538; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ru GQ, Wang HJ, Xu WJ, Zhao ZS. Upregulation of Twist in gastric carcinoma associated with tumor invasion and poor prognosis. Pathol Oncol Res 2011; 17:341-7; PMID:21104359; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12253-010-9332-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vichalkovski A, Gresko E, Hess D, Restuccia DF, Hemmings BA. PKB/AKT phosphorylation of the transcription factor Twist-1 at Ser42 inhibits p53 activity in response to DNA damage. Oncogene 2010; 29: 3554-65.; PMID:20400976; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2010.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silva BS, Yamamoto FP, Pontes FS, Cury SE, Fonseca FP, Pontes HA, Pinto-Junior DD. TWIST and p-Akt immunoexpression in normal oral epithelium, oral dysplasia and in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2012; 17:e29-34; PMID:21743395; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4317/medoral.17344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hong KO, Kim JH, Hong JS, Yoon HJ, Lee JI, Hong SP, Hong SD. Inhibition of Akt activity induces the mesenchymal-to-epithelial reverting transition with restoring E-cadherin expression in KB and KOSCC-25B oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2009; 28:28; PMID:19243631; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1756-9966-28-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin YC, Lin JC, Hung CM, Chen Y, Liu LC, Chang TC, Kao JY, Ho CT, Way TD. Osthole inhibits insulin-like growth factor-1-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition via the inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in human brain cancer cells. J Agric Food Chem 2014; 62:5061-71; PMID:24828835; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jf501047g [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim CJ, Sakamoto K, Tambe Y, Inoue H. Opposite regulation of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and cell invasiveness by periostin between prostate and bladder cancer cells. Int J Oncol 2011; 38:1759-66; PMID:21468544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Way TD, Huang JT, Chou CH, Huang CH, Yang MH, Ho CT. Emodin represses TWIST1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells by inhibiting the beta-catenin and Akt pathways. Eur J Cancer 2014; 50:366-78; PMID:24157255; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Z, Zhu J, Cao H, Ren H, Fang X. miR-10b promotes cell invasion through RhoC-AKT signaling pathway by targeting HOXD10 in gastric cancer. Int J Oncol 2012; 40:1553-60; PMID:22293682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hong KO, Kim JH, Hong JS, Yoon HJ, Lee JI, Hong SP, Hong SD. Inhibition of Akt activity induces the mesenchymal-to-epithelial reverting transition with restoring E-cadherin expression in KB and KOSCC-25B oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. J Exp Clin Canc Res 2009; 28:28; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1756-9966-28-28 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agarwal E, Brattain MG, Chowdhury S. Cell survival and metastasis regulation by Akt signaling in colorectal cancer. Cell Signal 2013; 25:1711-9; PMID:23603750; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng GZ, Chan J, Wang Q, Zhang W, Sun CD, Wang LH. Twist transcriptionally up-regulates AKT2 in breast cancer cells leading to increased migration, invasion, and resistance to paclitaxel. Cancer Res 2007; 67:1979-87; PMID:17332325; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen LX, He YJ, Zhao SZ, Wu JG, Wang JT, Zhu LM, Lin TT, Sun BC, Li XR. Inhibition of tumor growth and vasculogenic mimicry by curcumin through down-regulation of the EphA2/PI3K/MMP pathway in a murine choroidal melanoma model. Cancer Biol Ther 2011; 11:229-35; PMID:21084858; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cbt.11.2.13842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prokop JW, Liu Y, Milsted A, Peng H, Rauscher FJ 3rd. A method for in silico identification of SNAIL/SLUG DNA binding potentials to the E-box sequence using molecular dynamics and evolutionary conserved amino acids. J Mol Model 2013; 19:3463-9; PMID:23708613; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00894-013-1876-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cano A, Perez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, Portillo F, Nieto MA. The transcription factor Snail controls epithelial mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol 2000; 2:76-83; PMID:10655586; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35000025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qiao B, Johnson N, Gao J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in oral squamous cell carcinoma triggered by transforming growth factor-β1 is Snail family-dependent and correlates with matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 expressions. Int J Oncol 2010; 37:663-8; PMID:20664935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee YJ, Han HJ. Troglitazone ameliorates high glucose-induced EMT and dysfunction of SGLTs through PI3K/Akt, GSK-3beta, Snail1, and beta-catenin in renal proximal tubule cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2010; 298:F1263-75; PMID:20015942; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajprenal.00475.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adhikary A, Chakraborty S, Mazumdar M, Ghosh S, Mukherjee S, Manna A, Mohanty S, Nakka KK, Joshi S, De A, et al.. Inhibition of epithelial to mesenchymal transition by E-cadherin up-regulation via repression of slug transcription and inhibition of E-cadherin degradation: dual role of SMAR1 in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 2014; 289:25431-44; PMID:25086032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emadi Baygi M, Soheili ZS, Essmann F, Deezagi A, Engers R, Goering W, Schulz WA. Slug/SNAI2 regulates cell proliferation and invasiveness of metastatic prostate cancer cell lines. Tumour Biol 2010; 31:297-307; PMID:20506051; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s13277-010-0037-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saegusa M, Hashimura M, Kuwata T, Okayasu I. Requirement of the Akt/beta-catenin pathway for uterine carcinosarcoma genesis, modulating E-cadherin expression through the transactivation of slug. Am J Pathol 2009; 174:2107-15; PMID:19389926; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bolos V, Peinado H, Perez-Moreno MA, Fraga MF, Esteller M, Cano A. The transcription factor Slug represses E-cadherin expression and induces epithelial to mesenchymal transitions: a comparison with Snail and E47 repressors. J Cell Sci 2003; 116:499-511; PMID:12508111; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.00224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yan Z, Yin H, Wang R, Wu D, Sun W, Liu B, Su Q. Overexpression of integrin-linked kinase (ILK) promotes migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells by inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition via NF-kappaB signaling. Acta Histochem 2014; 116:527-33; PMID:24360977; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.acthis.2013.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Delcommenne M, Tan C, Gray V, Rue L, Woodgett J, Dedhar S. Phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase-dependent regulation of glycogen synthase kinase 3 and protein kinase B/AKT by the integrin-linked kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1998; 95:11211-6; PMID:9736715; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li L, Pan XY, Shu J, Jiang R, Zhou YJ, Chen JX. Ribonuclease inhibitor up-regulation inhibits the growth and induces apoptosis in murine melanoma cells through repression of angiogenin and ILK/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Biochimie 2014; 103:89-100; PMID:24769129; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biochi.2014.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kang MH, Oh SC, Lee HJ, Kang HN, Kim JL, Kim JS, Yoo YA. Metastatic function of BMP-2 in gastric cancer cells: the role of PI3K/AKT, MAPK, the NF-kappaB pathway, and MMP-9 expression. Exp Cell Res 2011; 317:1746-62; PMID:21570392; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cichon MA, Radisky DC. ROS-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in mammary epithelial cells is mediated by NF-kB-dependent activation of Snail. Oncotarget 2014; 5:2827-38; PMID:24811539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tester AM, Ruangpanit N, Anderson RL, Thompson EW. MMP-9 secretion and MMP-2 activation distinguish invasive and metastatic sublines of a mouse mammary carcinoma system showing epithelial-mesenchymal transition traits. Clin Exp Metastasis 2000; 18:553-60; PMID:11688960; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/A:1011953118186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zuo JH, Zhu W, Li MY, Li XH, Yi H, Zeng GQ, Wan XX, He QY, Li JH, Qu JQ, et al.. Activation of EGFR promotes squamous carcinoma SCC10A cell migration and invasion via inducing EMT-like phenotype change and MMP-9-mediated degradation of E-cadherin. J Cell Biochem 2011; 112:2508-17; PMID:21557297; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcb.23175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoo YA, Kang MH, Lee HJ, Kim BH, Park JK, Kim HK, Kim JS, Oh SC. Sonic hedgehog pathway promotes metastasis and lymphangiogenesis via activation of Akt, EMT, and MMP-9 pathway in gastric cancer. Cancer Res 2011; 71:7061-70; PMID:21975935; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu ST, Sun GH, Hsu CY, Huang CS, Wu YH, Wang HH, Sun KH. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition of renal cell carcinoma cells via a nuclear factor kappa B-independent mechanism. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2011; 236:1022-9; PMID:21856755; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1258/ebm.2011.011058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O'Connor JW, Gomez EW. Biomechanics of TGFbeta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition: implications for fibrosis and cancer. Clin Transl Med 2014; 3:23; PMID:25097726; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/2001-1326-3-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ao M, Williams K, Bhowmick NA, Hayward SW. Transforming growth factor-beta promotes invasion in tumorigenic but not in nontumorigenic human prostatic epithelial cells. Cancer Res 2006; 66:8007-16; PMID:16912176; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hofmann AF. In memoriam: Dr. Herbert Falk (1924-2008). Hepatology 2009; 49:1-3; PMID:19108004; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/hep.22746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen X, Liao J, Lu Y, Duan X, Sun W. Activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway mediates bone morphogenetic protein 2-induced invasion of pancreatic cancer cells Panc-1. Pathol Oncol Res 2011; 17:257-61; PMID:20848249; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12253-010-9307-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wendt MK, Smith JA, Schiemann WP. Transforming growth factor-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition facilitates epidermal growth factor-dependent breast cancer progression. Oncogene 2010; 29:6485-98; PMID:20802523; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2010.377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Caja L, Ortiz C, Bertran E, Murillo MM, Miro-Obradors MJ, Palacios E, Fabregat I. Differential intracellular signalling induced by TGF-beta in rat adult hepatocytes and hepatoma cells: implications in liver carcinogenesis. Cell Signal 2007; 19:683-94; PMID:17055226; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xue G, Restuccia DF, Lan Q, Hynx D, Dirnhofer S, Hess D, Ruegg C, Hemmings BA. Akt/PKB-mediated phosphorylation of Twist1 promotes tumor metastasis via mediating cross-talk between PI3K/Akt and TGF-beta signaling axes. Cancer Discov 2012; 2:248-59; PMID:22585995; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maier HJ, Schmidt-Strassburger U, Huber MA, Wiedemann EM, Beug H, Wirth T. NF-kappaB promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition, migration and invasion of pancreatic carcinoma cells. Cancer Lett 2010; 295:214-28; PMID:20350779; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arsura M, Panta GR, Bilyeu JD, Cavin LG, Sovak MA, Oliver AA, Factor V, Heuchel R, Mercurio F, Thorgeirsson SS, et al.. Transient activation of NF-kappaB through a TAK1/IKK kinase pathway by TGF-beta1 inhibits AP-1/SMAD signaling and apoptosis: implications in liver tumor formation. Oncogene 2003; 22:412-25; PMID:12545162; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1206132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Julien S, Puig I, Caretti E, Bonaventure J, Nelles L, van Roy F, Dargemont C, de Herreros AG, Bellacosa A, Larue L. Activation of NF-kappaB by Akt upregulates Snail expression and induces epithelium mesenchyme transition. Oncogene 2007; 26:7445-56; PMID:17563753; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1210546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ward KR, Zhang KX, Somasiri AM, Roskelley CD, Schrader JW. Expression of activated M-Ras in a murine mammary epithelial cell line induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumorigenesis. Oncogene 2004; 23:1187-96; PMID:14961075; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.onc.1207226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liao J, Planchon SM, Wolfman JC, Wolfman A. Growth factor-dependent AKT activation and cell migration requires the function of c-K(B)-Ras versus other cellular ras isoforms. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:29730-8; PMID:16908523; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M600668200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Savagner P. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenomenon. Ann Oncol 2010; 21 Suppl 7:vii89-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sheng S, Qiao M, Pardee AB. Metastasis and AKT activation. J Cell Physiol 2009; 218:451-4; PMID:18988188; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jcp.21616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qiao M, Sheng S, Pardee AB. Metastasis and AKT activation. Cell Cycle 2008; 7:2991-6; PMID:18818526; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.7.19.6784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singh A, Settleman J. EMT, cancer stem cells and drug resistance: an emerging axis of evil in the war on cancer. Oncogene 2010; 29:4741-51; PMID:20531305; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/onc.2010.215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ginnebaugh KR, Ahmad A, Sarkar FH. The therapeutic potential of targeting the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2014; 18:731-45; PMID:24758643; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1517/14728222.2014.909807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang AD, Fan F, Camp ER, van Buren G, Liu W, Somcio R, Gray MJ, Cheng H, Hoff PM, Ellis LM. Chronic oxaliplatin resistance induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12:4147-53; PMID:16857785; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kajiyama H, Shibata K, Terauchi M, Yamashita M, Ino K, Nawa A, Kikkawa F. Chemoresistance to paclitaxel induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition and enhances metastatic potential for epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol 2007; 31:277-83; PMID:17611683 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Li QQ, Xu JD, Wang WJ, Cao XX, Chen Q, Tang F, Chen ZQ, Liu XP, Xu ZD. Twist1-mediated adriamycin-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition relates to multidrug resistance and invasive potential in breast cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res 2009; 15:2657-65; PMID:19336515; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hiscox S, Jiang WG, Obermeier K, Taylor K, Morgan L, Burmi R, Barrow D, Nicholson RI. Tamoxifen resistance in MCF7 cells promotes EMT-like behaviour and involves modulation of beta-catenin phosphorylation. Int J Cancer 2006; 118:290-301; PMID:16080193; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/ijc.21355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shah AN, Summy JM, Zhang J, Park SI, Parikh NU, Gallick GE. Development and characterization of gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic tumor cells. Ann Surg Oncol 2007; 14:3629-37; PMID:17909916; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1245/s10434-007-9583-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Arumugam T, Ramachandran V, Fournier KF, Wang H, Marquis L, Abbruzzese JL, Gallick GE, Logsdon CD, McConkey DJ, Choi W. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition contributes to drug resistance in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res 2009; 69:5820-8; PMID:19584296; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zhang W, Feng M, Zheng G, Chen Y, Wang X, Pen B, Yin J, Yu Y, He Z. Chemoresistance to 5-fluorouracil induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition via up-regulation of Snail in MCF7 human breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2012; 417:679-85; PMID:22166209; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.11.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hoshino H, Miyoshi N, Nagai K, Tomimaru Y, Nagano H, Sekimoto M, Doki Y, Mori M, Ishii H. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition with expression of SNAI1-induced chemoresistance in colorectal cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009; 390:1061-5; PMID:19861116; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fujiwara M, Izuishi K, Sano T, Hossain MA, Kimura S, Masaki T, Suzuki Y. Modulating effect of the PI3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 on cisplatin in human pancreatic cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2008; 27:76; PMID:19032736; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1756-9966-27-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.ho NL, Lin CI, Whang EE, Carothers AM, Moore FD Jr., Ruan DT. Sulindac reverses aberrant expression and localization of beta-catenin in papillary thyroid cancer cells with the BRAFV600E mutation. Thyroid 2010; 20:615-22; PMID:20470206; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/thy.2009.0415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tai WP, Hu PJ, Wu J, Lin XC. The inhibition of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in human colon cancer cells by sulindac. Tumori 2014; 100:97-101; PMID:24675499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.DiMeo TA, Anderson K, Phadke P, Fan C, Perou CM, Naber S, Kuperwasser C. A novel lung metastasis signature links Wnt signaling with cancer cell self-renewal and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Res 2009; 69:5364-73; PMID:19549913; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lewis C, Krieg PA. Reagents for developmental regulation of Hedgehog signaling. Methods 2014; 66:390-7; PMID:23981360; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ymeth.2013.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang X, Harrington N, Moraes RC, Wu MF, Hilsenbeck SG, Lewis MT. Cyclopamine inhibition of human breast cancer cell growth independent of Smoothened (Smo). Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009; 115:505-21; PMID:18563554; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10549-008-0093-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jang YH, Shin HS, Sun Choi H, Ryu ES, Jin Kim M, Ki Min S, Lee JH, Kook Lee H, Kim KH, Kang DH. Effects of dexamethasone on the TGF-beta1-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in human peritoneal mesothelial cells. Lab Invest 2013; 93:194-206; PMID:23207448; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/labinvest.2012.166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang Z, Li Y, Kong D, Banerjee S, Ahmad A, Azmi AS, Ali S, Abbruzzese JL, Gallick GE, Sarkar FH. Acquisition of epithelial-mesenchymal transition phenotype of gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells is linked with activation of the notch signaling pathway. Cancer Res 2009; 69:2400-7; PMID:19276344; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Aghdassi A, Sendler M, Guenther A, Mayerle J, Behn CO, Heidecke CD, Friess H, Buchler M, Evert M, Lerch MM, et al.. Recruitment of histone deacetylases HDAC1 and HDAC2 by the transcriptional repressor ZEB1 downregulates E-cadherin expression in pancreatic cancer. Gut 2012; 61:439-48; PMID:22147512; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liao W, Jordaan G, Srivastava MK, Dubinett S, Sharma S, Sharma S. Effect of epigenetic histone modifications on E-cadherin splicing and expression in lung cancer. Am J Cancer Res 2013; 3:374-89; PMID:23977447 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chang TH, Tsai MF, Su KY, Wu SG, Huang CP, Yu SL, Yu YL, Lan CC, Yang CH, Lin SB, et al.. Slug confers resistance to the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011; 183:1071-9; PMID:21037017; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1164/rccm.201009-1440OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li L, Jiang AC, Dong P, Wang H, Xu W, Xu C. MDR1/P-gp and VEGF synergistically enhance the invasion of Hep-2 cells with multidrug resistance induced by taxol. Ann Surg Oncol 2009; 16:1421-8; PMID:19247716; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1245/s10434-009-0395-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ma H, Cheng L, Hao K, Li Y, Song X, Zhou H, Jia L. Reversal effect of ST6GAL 1 on multidrug resistance in human leukemia by regulating the PI3K/Akt pathway and the expression of P-gp and MRP1. PLoS One 2014; 9:e85113; PMID:24454800; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0085113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 92.Zhao BX, Sun YB, Wang SQ, Duan L, Huo QL, Ren F, Li GF. Grape seed procyanidin reversal of p-glycoprotein associated multi-drug resistance via down-regulation of NF-kappaB and MAPK/ERK mediated YB-1 activity in A2780/T cells. PLoS One 2013; 8:e71071; PMID:23967153; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0071071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Li W, Liu C, Tang Y, Li H, Zhou F, Lv S. Overexpression of Snail accelerates adriamycin induction of multidrug resistance in breast cancer cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2011; 12:2575-80; PMID:22320957 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Zhu K, Chen L, Han X, Wang J, Wang J. Short hairpin RNA targeting Twist1 suppresses cell proliferation and improves chemosensitivity to cisplatin in HeLa human cervical cancer cells. Oncol Rep 2012; 27:1027-34; PMID:22245869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Saxena M, Stephens MA, Pathak H, Rangarajan A. Transcription factors that mediate epithelial-mesenchymal transition lead to multidrug resistance by upregulating ABC transporters. Cell Death Dis 2011; 2:e179; PMID:21734725; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/cddis.2011.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wei J, Xu G, Wu M, Zhang Y, Li Q, Liu P, Zhu T, Song A, Zhao L, Han Z, et al.. Overexpression of vimentin contributes to prostate cancer invasion and metastasis via src regulation. Anticancer Res 2008; 28:327-34; PMID:18383865 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]