ABSTRACT

Cell cycle checkpoints prevent mitosis from occurring before DNA replication and repair are completed during S and G2 phases. The checkpoint mechanism involves inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdk1, a conserved kinase that regulates the onset of mitosis. Metazoans have two distinct Cdk1 inhibitory kinases with specialized developmental functions: Wee1 and Myt1. Ayeni et al used transgenic Cdk1 phospho-acceptor mutants to analyze how the distinct biochemical properties of these kinases affected their functions. They concluded from their results that phosphorylation of Cdk1 on Y15 was necessary and sufficient for G2/M checkpoint arrest in imaginal wing discs, whereas phosphorylation on T14 promoted chromosome stability by a different mechanism. A curious relationship was also noted between Y15 inhibitory phosphorylation and T161 activating phosphorylation. These unexpected complexities in Cdk1 inhibitory phosphorylation demonstrate that the checkpoint mechanism is not a simple binary “off/on” switch, but has at least three distinct states: “Ready”, to prevent chromosome damage and apoptosis, “Set”, for developmentally regulated G2 phase arrest, and “Go”, when Cdc25 phosphatases remove inhibitory phosphates to trigger Cdk1 activation at the G2/M transition.

Keywords: cell cycle checkpoint, Cdk1 inhibitory phosphorylation, mitosis, genome stability

Progression through the eukaryotic cell cycle is catalyzed by the activities of conserved cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdks). The master mitotic regulator Cdk1 is responsible for initiating the early events of mitosis, phosphorylating proteins that are involved in mitotic processes such as nuclear envelope breakdown, chromosome condensation, spindle assembly and the disassembly of the Golgi and ER membranes. Cell cycle checkpoints that promote inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdk1 by Wee1-related inhibitory kinases are therefore needed to prevent aberrant mitotic events from occurring prematurely during S and G2 phases (Figure 1). There are two types of Cdk1 inhibitory kinases in metazoans: Wee1 and Myt1. Nuclear Wee1 kinases catalyze inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdk1 on tyrosine residue 15, whereas cytoplasmic Myt1 kinases localize to Golgi and endoplasmic reticulum membranes and phosphorylate both Y15 and the adjacent threonine (T14) residue. Together, these Cdk1 inhibitory kinases ensure that cells complete DNA replication and repair before mitosis begins. Otherwise, checkpoint defects result in genome instability and lethal mitotic catastrophe.1 Paradoxically, human cancer cells with G1/S checkpoint defects are often resistant to chemotherapy because they over-express Wee1 and rely instead on G2/M checkpoint responses to withstand DNA damage that would otherwise trigger apoptosis.2,3 To exploit the unique vulnerability of these cancers, treatment with Wee1 inhibitors is currently being tested and encouraging results suggest that this will be an effective new therapeutic strategy .4,5

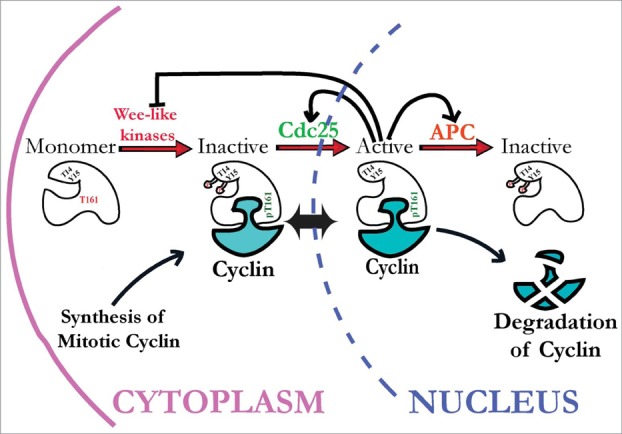

Figure 1.

Current view of how cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1) activity is regulated by inhibitory and activating phosphorylation. Stable Cdk1 kinase subunits are bound by newly synthesized mitotic cyclins during S and G2 phases and subject to activating phosphorylation on threonine-161 (T161) residue by CAK kinases, but kept inactive via inhibitory phosphorylation on Y15 and T14 residues by Wee1-like inhibitory kinases (Myt1 and Wee1, in metazoans). During interphase, these Cdk1/cyclin complexes can shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus. To initiate mitosis, Cdk1/cyclin complexes must be activated by Cdc25 phosphatases that remove inhibitory phosphates from Cdk1. Active Cdk1 can then initiate a positive feedback loop that inactivates Wee1 and Myt1 kinases and further activates Cdc25 phosphatases, creating a burst of Cdk1 activity that initiates mitosis. This mechanism is re-set during mitosis by Cdk1 activation of the APC/C complex, extinguishing Cdk1 activity via ubiquitin-mediated cyclin proteolysis.

Developmental Regulation of Cdk1 Inhibitory Phosphorylation by Wee1 and Myt1 Kinases

Drosophila researchers have made many important contributions to understanding how Cdk1 regulation by inhibitory phosphorylation coordinates the timing of mitosis to avoid interference with dynamic developmental processes. For example, during Drosophila gastrulation bursts of Cdc25 phosphatase expression (encoded by the stg gene) activate Cdk1, driving an intricate pattern of “mitotic domains”6-8 that is controlled by complicated transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms which temporally and spatially restrict Cdc25stg activity.9-13 Regulation of Cdk1 by inhibitory phosphorylation also coordinates cell division with terminal cell fate differentiation later in development,14 by mechanisms that are not yet well understood.

Most animal models have multiple Wee1 paralogs, however Drosophila only has a single representative of each type of Cdk1 inhibitory kinase: dWee1 and dMyt1. The Drosophila wee1 homolog was cloned by genetic complementation of fission yeast wee1 mik1 mutants, demonstrating strong functional conservation.16 The wee1 gene is expressed throughout development, however studies of maternal effect mutants revealed an essential function during the first two hours of early embryonic development, when nuclei rapidly cycle between S and M phases in a common syncytium.17 Maternal Wee1 collaborates with the Drosophila Chk1 and ATR-related checkpoint kinases, Grp and Mei-41 (18, 19)18,19 in a conserved checkpoint mechanism that lengthens S phase to accommodate the onset of late replicating origins during the late syncytial cycles.20,21 Although embryonic development initiates normally without this checkpoint mechanism, wee1 mutants undergo lethal mitotic catastrophe in cycle 11-12.17 Studies of injected live embryos have also shown that Wee1 and Grp are also required for DNA condensation and metaphase checkpoint mechanisms that respond to DNA damage in the early embryo.22 Curiously, inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdk1 on Y15 is extremely difficult to detect in early embryos compared with later stages of development,23,24 implying that the checkpoint for controlling Cdk1 activity in syncytial embryos operates by a novel mechanism. Wee1 is also essential for genome stability and cell viability in early mammalian embryos, suggesting that the embryonic checkpoint mechanism may be conserved in other animals.25

The Drosophila myt1 gene was cloned by its similarity to human and Xenopus Myt1 dual specificity kinases.15,26-28 Null myt1 mutants are male sterile with defects in the development of certain sensory bristles as well as G2/M checkpoint responses to DNA damage.15,29 Drosophila Myt1 is also required for male meiosis in Drosophila, in contrast with C. elegans and X. laevis where it is essential for female meiosis.30-32 In spite of these specialized developmental roles however, the zygotic functions of Drosophila Wee1 and Myt1 are redundant for viability throughout most of development.15

Experimental Hypothesis and Approach

The significance of the dual phosphorylation checkpoint mechanism that evolved for regulating Cdk1 in metazoans remains poorly understood. In fission yeast where Wee1 was first discovered for its role in cell size control, phosphorylation of Cdk1 on Y15 by Wee1 is both necessary and sufficient for checkpoint arrest responses to DNA replication or DNA damage.33,34 In metazoans, Myt1-mediated dual phosphorylation of Cdk1 on two adjacent residues (T14 and Y15) produces three different inhibited Cdk1 phospho-isoforms: T14p, Y15p and T14pY15p. These phospho-isoforms can all be detected in cycle 14 Drosophila embryos as newly formed cells enter their first G2 phase cell cycle arrest.23 Our hypothesis is that the unique biochemical properties of Wee1 and Myt1 kinases are central to understanding their specialized developmental functions in vivo. For example, dual phosphorylation may make Cdk1 more refractory to de-phosphorylation by Cdc25 than Cdk1 phosphorylated on Y15 or T14 alone. This could make for a more robust “developmental switch” mechanism for timing mitosis or meiosis, consistent with evidence that Myt1 serves an important role in cells which undergo prolonged G2 phase arrest as part of their developmental program.15,29-31,35-37 In contrast, phosphorylation of Cdk1 on either T14 or Y15 could influence Cdk1 activity by non-canonical mechanisms, for example recent evidence that T14 phosphorylation can facilitate T161 activating phosphorylation under certain circumstances.38

To test the hypothesis that biochemical differences in Wee1 and Myt1 phosphorylation mechanisms underlie the specialized as well as redundant roles of Cdk1 inhibitory kinases during Drosophila development, Ayeni et al. constructed transgenic strains for expressing VFP-tagged versions of Cdk1 wild type and phospho-acceptor mutant variants.39 Experiments with these new transgenic strains revealed that G2 phase checkpoint responses used to delay mitosis in response to developmental cues and to DNA damage could be uncoupled from a mechanism that promotes cell survival by preserving chromosome stability. Their study therefore provides new insights into the regulatory mechanisms used to regulate Cdk1 during Drosophila development that may also be relevant to other multicellular organisms.

Drosophila G2/M Checkpoint Regulation Depends on Y15 Phosphorylation

Transgene expression of non-inhibitable Cdk1 (Cdk1-AF) has previously been shown to drive G2 phase-arrested cells prematurely into mitosis, either by direct phosphorylation of mitotic Cdk1 substrates or by triggering “all or none” amplification mechanisms for activating endogenous Cdk1.40,41 Using Gal4-inducible expression, Ayeni et al. examined the effects of wild type and phospho-acceptor mutant Cdk1 variants to investigate how each aspect of the dual Cdk1 phosphorylation checkpoint mechanism affected imaginal development.39 Because these transgenic Cdk1 proteins were tagged with a fluorescent reporter (VFP), they were able to directly compare properties of different Cdk1 phospho-isoforms, in vivo and in vitro. Cdk1-VFP fusion proteins expressed in imaginal wing discs could bind endogenous mitotic cyclins A and B and were phosphorylated by endogenous Wee1 and Myt1 kinases;39 see Figure 1). Ubiquitous expression of wild type Cdk1-VFP or the T14A mutant could also rescue the pupal lethality of temperature-sensitive cdc2 mutants, demonstrating that these proteins were fully functional in vivo. In contrast, the Y15F and T14AY15F mutants that could not be phosphorylated on Y15 were not able to rescue the cdc2 mutants, implying that phosphorylation of Cdk1 on this residue was specifically required for cell cycle checkpoint responses during Drosophila development.

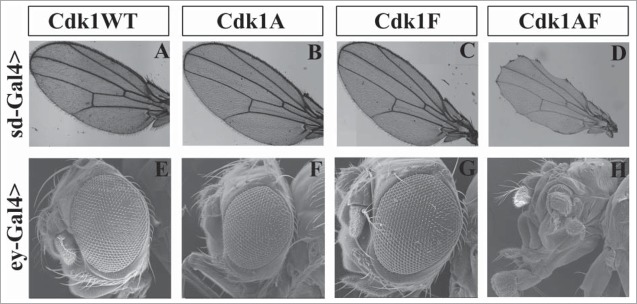

Expression of non-inhibitable Cdk1(T14AY15F)-VFP in wing or eye imaginal discs produced adult morphological defects that were not observed with any of the other Cdk1 variants (Figure 2;.39 When the wing discs were examined directly, however, we observed that expression of either Y15F or T14AY15F caused elevated mitotic index and ectopic apoptosis that was not observed with the T14A or WT variants.39 The Y15F and T14AY15F mutants were also both effective at bypassing G2 phase checkpoint arrest induced by ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage or a developmentally-regulated G2 phase checkpoint arrest that is characteristic of cells at the presumptive wing margin (see Figure 3;.39 We therefore concluded from these results that phosphorylation of Cdk1 on Y15 is necessary for normal development.39 This interpretation also accounts for the functional redundancy of Drosophila Wee1 and Myt1 for most aspects of zygotic development, since both kinases phosphorylate Cdk1 on Y15.15

Figure 2.

UASp-Cdk1-VFP transgenes expressed in imaginal wing or eye discs with sd-Gal4 or ey-Gal4, respectively, cause distinct phenotypic effects. Panels A to D show adult wings of progeny expressing the indicated transgenes in an otherwise wild-type background. Expression of Cdk1(WT), Cdk1(T14A) or Cdk1(Y15F) caused no detectable defects in adult wing morphology (A–C), whereas expression of Cdk1(T14A,Y15F) resulted in wing margin defects (D). (E–H) Scanning electron micrographs of adult eyes. Expression of Cdk1(WT), Cdk1(T14A) or Cdk1(Y15F) did not affect adult eye development (E–G), however Cdk1(T14A,Y15F) produced severe defects in adult eye and head structures resulting in pharate adult lethality. © Genetics Society of America. Reproduced with permission from Genetics Society of America. Permission to reuse must be obtained by the copyright holder.39

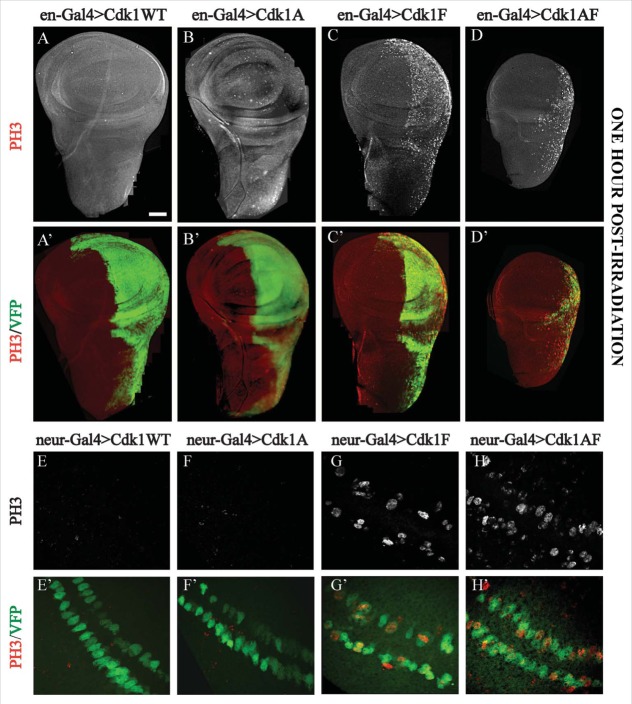

Figure 3.

G2/M checkpoint responses assayed in imaginal wing discs expressing Cdk1-VFP transgenes under control of engrailed-Gal4 or neuralized-Gal4. (A–D) Expression of the VFP-tagged Cdk1 transgene (Green) in the posterior compartment of the wing disc, whereas (E–H) show transgene expression in a subset of G2 phase developmentally-arrested sensory organ precursor cells at the presumptive wing margin.52 In panels A to D, DNA damage checkpoint responses were assayed by dissecting wing discs from late third instar larvae 60 min after exposure to 40 Gy of ionizing radiation and labeling them with PH3 antibodies to mark mitotic cells (white in A-D, red in A’–D’). A and A’ and B and B’ showed no PH3-positive cells in either compartment of wing discs expressing Cdk1(WT) or Cdk1(T14A), demonstrating a functional G2/M checkpoint response to DNA damage. In C and C’ and D and D’ however, wing discs expressing Cdk1(Y15F) or Cdk1(T14A,Y15F) showed PH3 labeling specifically in the posterior compartment, indicating defects in the G2/M checkpoint response. In E and F the transgenes were expressed in sensory organ precursor (SOP) cells using neuralized-Gal4 to assay developmentally regulated G2/M checkpoint responses. SOP cells expressing Cdk1(WT)-VFP and Cdk1(T14A) were PH3-negative as expected for G2 phase arrested cells. Cells expressing Cdk1(Y15F)-VFP or Cdk1(T14A,Y15F) appeared as a mixture of smaller, mitotic (PH3-positive) and non-mitotic cells (G and H), indicating that many of the SOP cells were no longer arrested in G2 phase. E’–H’ are controls, showing that each of the VFP-tagged transgenes was expressed in the two rows of SOP cells. © Genetics Society of America. Reproduced with permission from Genetics Society of America. Permission to reuse must be obtained by the copyright holder.39

Myt1-Mediated T14 Phosphorylation Prevents DNA Damage and Genome Instability

If phosphorylation of Cdk1 on Y15 by either Wee1 or Myt1 is sufficient for G2/M checkpoint arrest, then what is the significance of Myt1 phosphorylation of Cdk1 on T14? One important clue was the observation that expression of non-inhibitable T14AY15F mutants caused developmental defects that were not seen with the Y15F mutant (33; Figure 2) even though these mutants were equally effective at bypassing G2/M checkpoint arrest (Figure 3). These differences were eliminated when the Y15F mutant was expressed in a myt1 mutant background, indicating that T14 phosphorylation of the Y15F mutant was the relevant factor. Measurements of in vitro H1 kinase activity showed that the catalytic activity of the Y15F mutant proteins was intermediate between T14AY15F and Cdk1(WT) or T14A, demonstrating that T14 phosphorylation partially inhibited Cdk1 activity of the Y15 mutant.39 From these results we concluded that T14 inhibitory phosphorylation was capable of promoting cell survival by a distinct molecular mechanism, even though it was insufficient for G2/M checkpoint arrest.

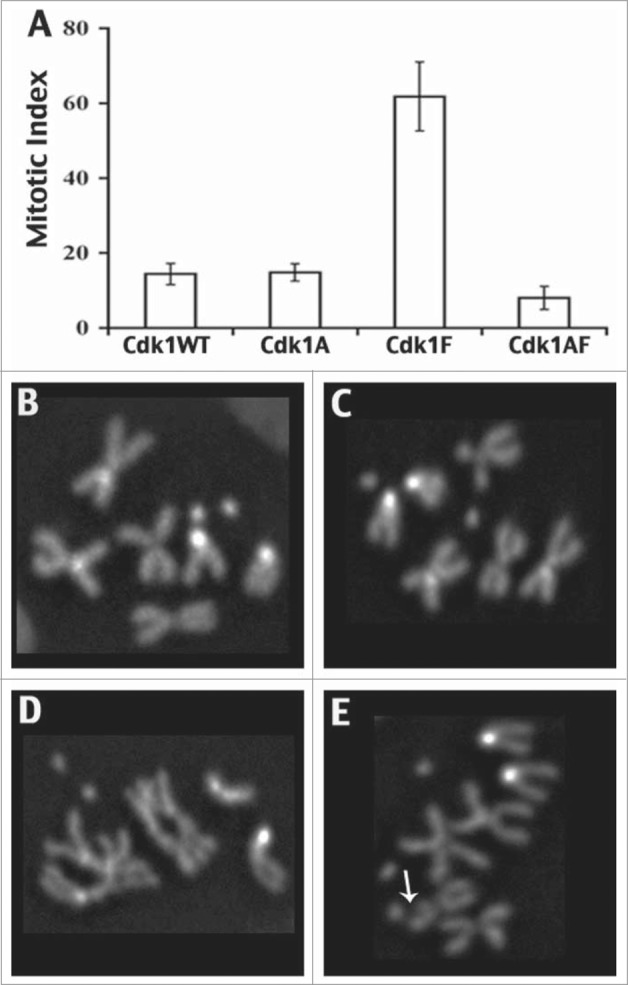

Another clue to the significance of Myt1-mediated T14 phosphorylation came from studies of type I larval neuroblasts, where expression of the T14AY15F mutant caused mitotic defects and gross chromosomal aberrations not observed with any of the other mutant Cdk1 transgenes (Figure 4; 39). Collectively, these results showed directly that Myt1 phosphorylation of Cdk1 on T14 protects chromosomes and promotes genome stability by a mechanism that is distinct from the canonical G2/M checkpoint. The most likely explanation is that T14 phosphorylation of Cdk1 is sufficient for an S phase checkpoint mechanism that protects cells when they are replicating or repairing their DNA.42 Since defects in the S phase checkpoint are already known to trigger chromosome rearrangements and apoptosis,42,43 this interpretation is consistent with our data showing more severe defects caused by expression of the T14AY15F mutant than the Y15F mutants. We therefore concluded that checkpoint-mediated inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdk1 on either T14 or Y15 can make cells “Ready” for mitosis, but by distinct mechanisms. As mitotic cyclins accumulate during G2 phase cells become “Set” by dual T14 and Y15 inhibitory phosphorylation, building up a large pool of inhibited Cdk1 complexes that can then be rapidly activated to coordinately initiate mitosis (“Go”), once Cdc25 phosphatases are expressed.

Figure 4.

Mitotic phenotypes associated with expression of Cdk1-VFP transgenes in type 1 neuroblasts using prospero-Gal4. These data were derived from metaphase karyotypes of colchicine-treated brain squashes labeled with Hoechst 33258 to identify mitotic chromosomes. At least 800 interpretable karyotypes were examined for each genotype. (A) Bar chart indicating the mitotic index associated with each Cdk1 transgene, showing an elevated mitotic index associated with Cdk1(Y15F) expression. In B–E, karyotypes of type 1 neuroblasts expressing Cdk1-VFP transgenes are shown. (B and C) Neuroblasts expressing Cdk1(WT) or Cdk1(Y15F) had normal metaphase chromosomes with cohered sister chromatids, whereas Cdk1(T14A,Y15F)-expressing neuroblasts exhibited gross chromosomal aberrations, including poorly condensed chromosomes (D) and chromosome breaks (E). © Genetics Society of America. Reproduced with permission from Genetics Society of America. Permission to reuse must be obtained by the copyright holder.39

A Curious Relationship Between Inhibitory and Activating Phosphorylation of Cdk1

Activation of Cdk1 requires both binding to a mitotic cyclin and T-loop phosphorylation. In Drosophila, T-loop phosphorylation at residue T161 is controlled by a Cdk1-activating kinase (CAK) called Cdk7, which is also part of the transcription machinery.44,45 In a recent study of mammalian cells, T14 phosphorylation was reported to facilitate T161 activating phosphorylation as a mechanism for protecting cells from prematurely activated Cyclin B-Cdk1.38 We therefore examined how T161 phosphorylation was affected in our transgenic Drosophila Cdk1 proteins expressed in wing discs. As predicted, T161 phosphorylation was undetectable on T14A mutant Cdk1 proteins that could not be phosphorylated on T14 (see Figure 1B in 39). Results with the T14AY15F mutant proteins that also lacked T14 phosphorylation were puzzling, however, because in this case the T161 residue was phosphorylated as well as Cdk1(WT) controls. To explain these paradoxical results, we propose that phosphorylation of the T14A mutant on the Y15 residue has a disruptive effect on Cdk1-cyclin complex stability.

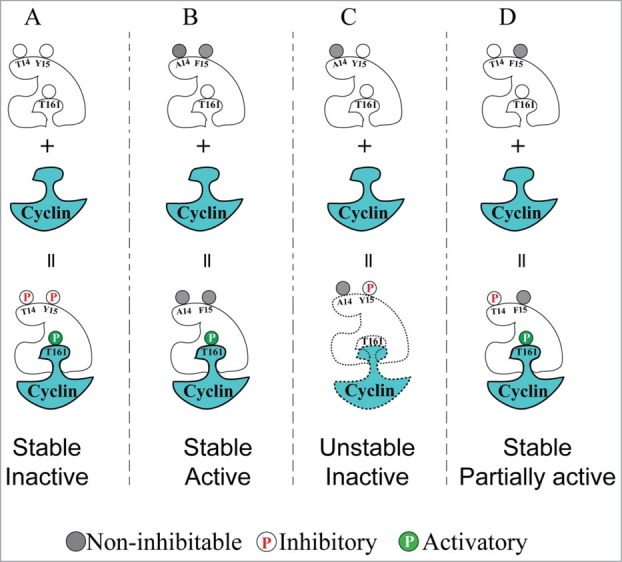

The model shown in Figure 5 summarizes the findings of Ayeni et al., describing how we think that phosphorylation of T14 and Y15 affects Cdk1 activity. In this model we propose that Y15 phosphorylation can both inhibit Cdk1 catalytic activity and de-stabilize Cdk1/Cyclin complexes, consistent with evidence from other systems that phosphorylation of Y15 specifically de-stabilizes Cdk1-cyclin B complexes whereas T161 phosphorylation facilitates stable interactions between cyclin B and Cdk1.38,46,47 T14 phosphorylation can partially inhibit Cdk1 activity and although this is not sufficient for G2 phase arrest, we propose that dual phosphorylation overcomes the proposed de-stabilizing effect of Y15 phosphorylation on Cdk1-cyclin stability.

Figure 5.

Model that can account for the distinct effects of Cdk1 inhibitory phosphorylation on T14 and Y15 residues. (A) Cdk1 is normally inactive (but can be activated) during interphase, due to simultaneous dual inhibitory phosphorylation and T161 activating phosphorylation. (B) Non-inhibitable Cdk1(T14A,Y15F) mutant can be immediately activated by T161 phosphorylation upon cyclin binding, causing G2/M checkpoint defects and genome instability. (C) Phosphorylation of Cdk1 on Y15 alone (mimicked by the T14A mutant) caused interference with T161 phosphorylation resulting in low in vitro HI kinase activity. These effects could be explained if Y15 phosphorylation by itself has an antagonistic effect on the stability of Cdk1/cyclin complexes. (D) Phosphorylation of Cdk1 on T14 alone (mimicked by the Y15F mutant) resulted in intermediate levels of Cdk1 activity and by-pass of G2 phase checkpoint arrest, but without causing the genome instability observed with the T14AY15F mutant.

Our proposal that Y15 phosphorylation affects Cdk1-cyclin stability has interesting implications for understanding the maternal function of the Wee, the Y15-directed kinase, during early Drosophila development. Embryos lacking maternal Wee1 activity initiate development normally but subsequently undergo lethal “mitotic catastrophe” due to absence of the checkpoint mechanism that progressively lengthens S phase during cycles 10-13.17,24 How this Wee1 embryonic checkpoint mechanism operates remains an enigma however, as Y15 phosphorylation of Cdk1 is barely detectable, unlike somatic cells.24 Curiously, activating phosphorylation of Cdk1 on T161 (and therefore Cdk1 activity) oscillates during interphase of Drosophila cycles 10-13,23 transiently disappearing during S phase. This timing coincides with when the Wee1 checkpoint is active,24 suggesting a possible mechanistic link between Cdk1 activating and inhibitory phosphorylation. Although speculative at present, such a coupling mechanism could explain the enigma of the Wee1 embryonic checkpoint21,49 if the inability to phosphorylate Cdk1 on Y15 in maternal wee1 mutants leads to mitotic catastrophe because of elevated mitotic kinase activity resulting from sustained Cdk1 activating (T161) phosphorylation or increased stability of Cdk1/Cyclin complexes. This proposed mechanism could also be conserved in other metazoans, since observations that Cdk1 inhibitory phosphorylation is difficult to detect have also been made in early Xenopus embryos.50

Future Directions

In addition to coordinating mitosis with morphogenetic movements during gastrulation, Cdk1 regulatory mechanisms are also used to synchronize developmental timing of mitosis with the adoption of specific terminal cell fates.51 How this process occurs is presently not well understood, however. For example, thoracic microchaetae develop from sensory organ precursor cells that undergo an invariant cell lineage to produce four terminally differentiated cell types (socket, shaft, neuron and sheath cells). Drosophila myt1 mutants exhibit macrochaetae defects, however the exact role that inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdk1 plays in the development of this cell lineage remains unclear.15 A previous study of this lineage used ectopic expression of Wee1 and Myt1 to investigate the relationship between cell fate specification and Cdk1 activity and found that although inhibitory phosphorylation of Cdk1 coordinated the timing of mitosis with terminal cell differentiation, acquisition of neuronal cell fate potential involved a Cdk1-independent mechanism that could still occur in G2 phase-arrested cells.14 The Cdk1Y15F mutants described by Ayeni et al. will be very useful tools for manipulating mitotic timing in this developmental system, in future studies aimed at resolving how developmental regulation of the cell cycle coordinates the formation of cells with distinct, terminally differentiated characteristics.

Funding Statement

Funding of our research came from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge helpful comments on the manuscript from Ellen Homola, David Stuart, Martin Srayko and Pierre Roger.

References

- 1. Lundgren K, et al. , Cell 1991; 64:1111; PMID:1706223; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90266-2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Magnussen GI, et al. , PLoS One 2012; 7:e38254; PMID:22719872; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0038254] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vriend LE, De Witt Hamer PC, Van Noorden CJ, Wurdinger T, Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1836:227; PMID:23727417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Do K, Doroshow JH, Kummar S, Cell Cycle 2013; 12:3159; PMID:24013427; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/cc.26062] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Van Linden AA, et al. Mol Cancer Ther 2013; 12:2675; PMID:24121103; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0424] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Edgar BA, O'Farrell PH, Cell 1989; 57:177; PMID:2702688; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90183-9] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Edgar BA, O'Farrell PH, Cell 1990; 62:469; PMID:2199063; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90012-4] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Foe VE, Dev 1989; 107:1; PMID:22483720NOT_FOUND [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Di Talia S, Wieschaus EF, Dev Cell 2012; 22:763; PMID:22483720; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.01.019] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Edgar BA, Lehman DA, O'Farrell PH. Dev 1994; 120:3131; PMID:10850494NOT_FOUND [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grosshans J, Wieschaus E, Cell 2000; 101:523; PMID:10850494; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80862-4] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mata J, Curado S, Ephrussi A, Rorth P. Cell 2000; 101:511; PMID:10850493; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80861-2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seher TC, Leptin M. Curr Biol 2000; 10:623; PMID:10837248; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00502-9] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fichelson P, Audibert A, Simon F, Gho M. Trends Genet 2005; 21:413; PMID:15927300; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.tig.2005.05.010] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jin Z, Homola E, Tiong S, Campbell SD. Genetics 2008; 180:2123; PMID:18940789; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.108.093195] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Campbell SD, Sprenger F, Edgar BA, O'Farrell PH. Mol Biol Cell 1995; 6:1333; PMID:8573790; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.6.10.1333] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Price D, Rabinovitch S, O'Farrell PH, Campbell SD. Genetics 2000; 155:159; PMID:10790391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fogarty P, et al. Curr Biol 1997; 7:418; PMID:9197245; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0960-9822(06)00189-8] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sibon OC, Laurencon A, Hawley R, Theurkauf WE. Curr Biol 1999; 9:302; PMID:10209095; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80138-9] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McCleland ML, Shermoen AW, O'Farrell PH. J Cell Biol 2009; 187:7; PMID:19786576; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200906191] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shermoen AW, McCleland ML, O'Farrell PH. Curr Biol 2010; 20:2067; PMID:21074439; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2010.10.021] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fasulo B, et al. Mol Biol Cell 2012; 23:1047; PMID:22262459; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E11-10-0832] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Edgar BA, Sprenger F, Duronio RJ, Leopold P, O'Farrell PH. Genes Dev 1994; 8:440; PMID:7510257; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.8.4.440] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stumpff J, Duncan T, Homola E, Campbell SD, Su TT. Curr Biol 2004; 14:2143; PMID:15589158; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.050] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tominaga Y, Li C, Wang RH, Deng CX. Int J Biol Sci 2006; 2:161; PMID:16810330; [http://dx.doi.org/10.7150/ijbs.2.161] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Price DM, Jin Z, Rabinovitch S, Campbell SD. Genetics 2002; 161:721; PMID:12072468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Booher RN, Holman PS, Fattaey A. J Biol Chem 1997; 272:22300; PMID:9268380; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.272.35.22300] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mueller PR, Coleman TR, Kumagai A, Dunphy WG. Science 1995; 270:86; PMID:7569953; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.270.5233.86] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jin Z, et al. Development 2005; 132:4075; PMID:16107480; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.01965] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burrows AE, et al. Development 2006; 133:697; PMID:16421191; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.02241] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gaffre M, et al. , Development 2011; 138:3735; PMID:21795279; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/dev.063974] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Oh JS, Han SJ, Conti M. J Cell Biol 2010; 188:199; PMID:20083600; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200907161] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. O'Connell MJ, Raleigh JM, Verkade HM, Nurse P. EMBO J 1997; 16:545; PMID:9034337; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1093/emboj/16.3.545] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rhind N, Russell P. Mol Cell Biol 1998; 18:3782; PMID:9632761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lamitina ST, L'Hernault SW. Development 2002; 129:5009; PMID:12397109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakajo N, et al. Genes Dev 2000; 14:328; PMID:10673504 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Palmer A, Nebreda AR. Prog Cell Cycle Res 2000; 4:131; PMID:10740821; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-1-4615-4253-7_12] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Coulonval K, Kooken H, Roger PP. Mol Biol Cell 2011; 22:3971; PMID:21900495; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1091/mbc.E11-02-0136] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ayeni JO, et al. Genetics 2014; 196:197; PMID:24214341; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1534/genetics.113.156281] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. O'Farrell PH. Trends Cell Biol 2001; 11:512; PMID:11719058; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0962-8924(01)02142-0] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Su TT, Campbell SD, O'Farrell PH, Dev Biol 1998; 196:160; PMID:9576829; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/dbio.1998.8855] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Aguilera A, Garcia-Muse T. Annu Rev Genet 2013; 47:1; PMID:23909437; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1146/annurev-genet-111212-133232] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Recolin B, van der Laan S, Tsanov N, Maiorano D. Genes (Basel) 2014; 5:147; PMID:24705291; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3390/genes5010147] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen J, Larochelle S, Li X, Suter B, Nature 2003; 424:228; PMID:12853965; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/nature01746] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Larochelle S, Pandur J, Fisher RP, Salz HK, Suter B. Genes Dev 1998; 12:370; PMID:9450931; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.12.3.370] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ducommun B, et al. EMBO J 1991; 10:3311; PMID:1833185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gould KL, Moreno S, Owen DJ, Sazer S, Nurse P. EMBO J 1991; 10:3297; PMID:1655416; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Solomon MJ. Trends Biochem Sci 1994; 19:496; PMID:7855894; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90137-6] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Farrell JA, Shermoen AW, Yuan K, O'Farrell PH. Genes Dev 2012; 26:714; PMID:22431511; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1101/gad.186429.111] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ferrell JEJ, Wu M, Gerhart JC, Martin GS. Mol Cell Biol 1991; 11:1965; PMID:2005892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tio M, Udolph G, Yang X, Chia W. Nature 2001; 409:1063; PMID:11234018; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35059124] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Johnston LA, Edgar BA. Nature 1998; 394:82; PMID:9665132; [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/27925] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]