Abstract

Cytoplasmic Ca2+ overload is known to trigger autophagy and ER-stress. Furthermore, ER-stress and autophagy are commonly associated with degenerative pathologies, but their role in disease progression is still a matter of debate, in part, owing to limitations of existing animal model systems. The Drosophila eye is a widely used model system for studying neurodegenerative pathologies. Recently, we characterized the Drosophila protein, Calphotin, as a cytosolic immobile Ca2+ buffer, which participates in Ca2+ homeostasis in Drosophila photoreceptor cells. Exposure of calphotin hypomorph flies to continuous illumination, which induces Ca2+ influx into photoreceptor cells, resulted in severe Ca2+-dependent degeneration. Here we show that this degeneration is autophagy and ER-stress related. Our studies thus provide a new model in which genetic manipulations trigger changes in cellular Ca2+ distribution. This model constitutes a framework for further investigations into the link between cytosolic Ca2+, ER-stress and autophagy in human disorders and diseases.

Keywords: autophagy, calcium homeostasis, calphotin, Drosophila, ER-stress, photoreceptor cells

Abbreviations

- Cpn

calphotin

- Cpn1%

calphotin hypomorph

- TRP

Transient receptor potential

- Moe

dMoesin

Introduction

The Drosophila compound eye is a widely used genetic model for studying the underlying mechanisms associated with neuronal degeneration.1,2 Drosophila retina has been used for studying apoptosis regulating factors,1,3 constituting a genetic model for retinal degeneration.4,5 Fly photoreceptor cells are highly polarized and elongated epithelial cells with a specialized signaling compartment composed of tightly dense microvilli, the rhabdomere. The phototransduction machinery is housed exclusively in the rhabdomere, while the nucleus and cellular organelles reside in the cell body (reviewed in 6, 7).6,7 Upon intense illumination, TRP channels that are highly Ca2+ permeable and mainly localized along the rhabdomeric microvilli, are robustly activated. Consequently, the free Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]) in the rhabdomere is highly increased.8 Recently, we showed that Ca2+ diffusion between the rhabdomere and the cell body is strongly attenuated by the localization of an immobile Ca2+ buffer, calphotin (Cpn), at the base of the rhabdomere.9 The specific localization of calphotin at the boundary between the rhabdomere and cell body reduces Ca2+ diffusion to the cell body during illumination and protects the cell from degeneration. We showed that exposure of calphotin hypomorph flies to continuous illumination for 7 d induced severe photoreceptor degeneration, while no significant degeneration was observed in wild type (WT) flies under the same conditions, or in dark raised calphotin hypomorph flies. This light- and age- dependent degeneration was shown to be a consequence of Ca2+ overload in the cytosol of photoreceptor cells by partial rescue of the degenerative phenotype in flies overexpressing CalX (a Na+-Ca2+ exchanger, the major Ca2+ extrusion protein in photoreceptor cells).9,10 It is well established that Ca2+ overload in photoreceptor cells can lead to retinal degeneration10,11; however, the mechanism by which this degeneration occurs is largely unknown.

Although it is well established that cytoplasmic Ca2+ overload can trigger autophagy- and ER-stress- related cell death, the molecular targets of elevated cytosolic Ca2+ remain obscure. Increasing evidence has linked ER-stress and autophagy to pathologies such as neurodegenerative diseases, cancer and diabetes.12,13 Indeed, ER-stress and autophagy markers have been observed in degenerating tissues. However, the role of ER-stress and autophagy in disease progression is still a matter of debate. Moreover, the links between these processes and a wide variety of neurodegenerative disorders remain indirect and controversial, in part, owing to limitations of existing animal model systems.14

Here we show that light induced degeneration in calphotin hypomorph flies is autophagy and ER-stress related. Our studies further provide a new model, in which genetic manipulations trigger changes in cellular Ca2+ distribution leading to Ca2+ overload. This model constitutes a framework for further investigations into the link between cytosolic Ca2+, ER-stress and autophagy in human disorders and diseases.

Results

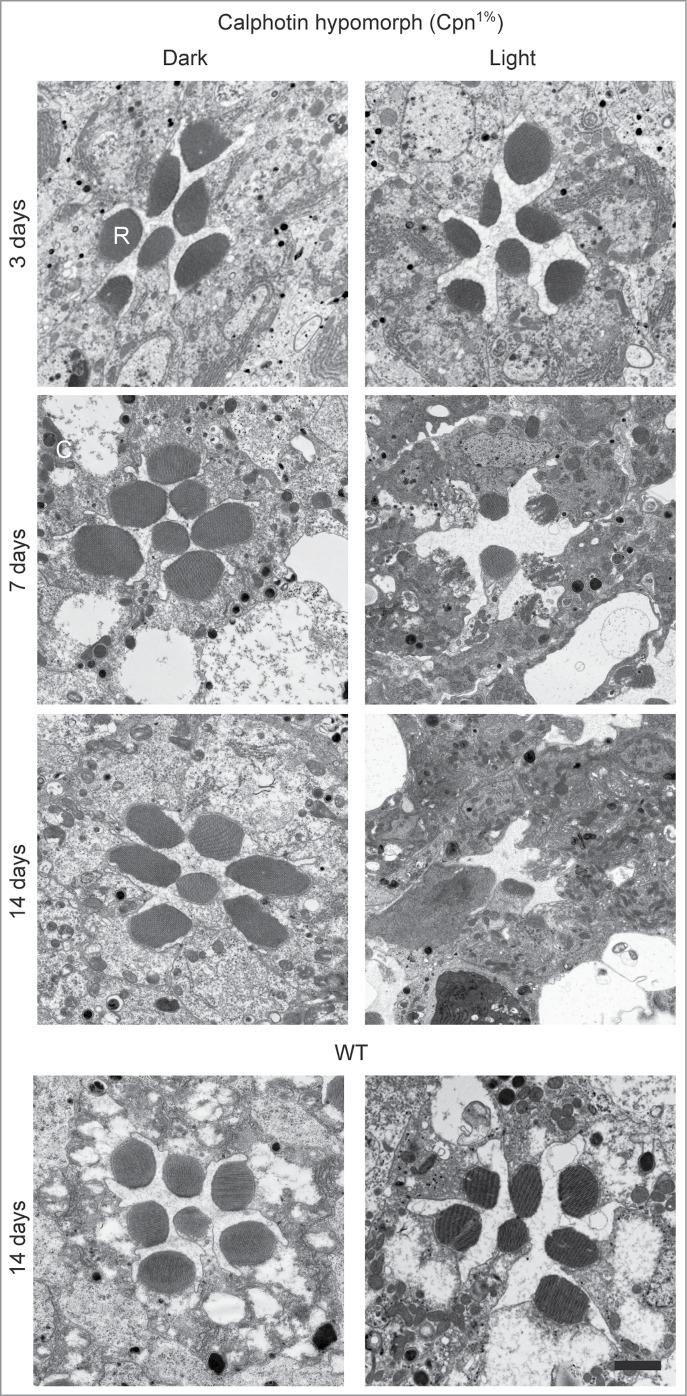

Elimination of calphotin induces severe age- and light- dependent photoreceptor degeneration

In our comprehensive study aiming to unravel the role of calphotin in Drosophila photoreceptor cells, we generated transgenic flies in which calphotin level was reduced to ∼1% (Cpn1%) of WT level.9 Exposure of Cpn hypomorph flies to continuous illumination for 3 d induced mild photoreceptor cell deformations (Fig. 1, upper panel). Further exposure of Cpn flies to 7 d of continuous illumination induced severe photoreceptor degeneration (Fig. 1). Most rhabdomeres of 7 d illuminated Cpn1% flies were either missing or strongly deformed, and the cell body appeared inundated with rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER) relative to WT photoreceptors (see below). Further exposure of the Cpn1% flies to 14 d of continuous illumination, virtually eliminated all photoreceptor cells. Cpn1% flies raised in the dark for 7 d showed relatively mild retinal deformation and Cpn1% flies raised in the dark for 14 d still maintained all rhabdomeres, but with deformed morphology (Fig. 1). In contrast, WT photoreceptor cells display no significant degeneration phenotypes, even when raised in continuous intense illumination for 14 d (Fig. 1, lower panel). The results thus show that elimination of calphotin induces severe age- and light- dependent photoreceptor degeneration.

Figure 1.

Elimination of calphotin induces severe age- and light- dependent photoreceptor degeneration. Thin EM sections of 3–14 d old Cpn1% ommatidia raised either in complete darkness (left) or in continuous illumination (right). Cpn1% retinae show only minor age dependent retinal deformations after 3 d of illumination. Cpn1% flies reared for 7 d or 14 d under constant illumination undergo severe age and light-dependent retinal degeneration compared to WT flies (lower panel) (N = 3 flies for each genotype and treatment, Bar = 2 μm).

Enhanced autophagy in Cpn hypomorph flies

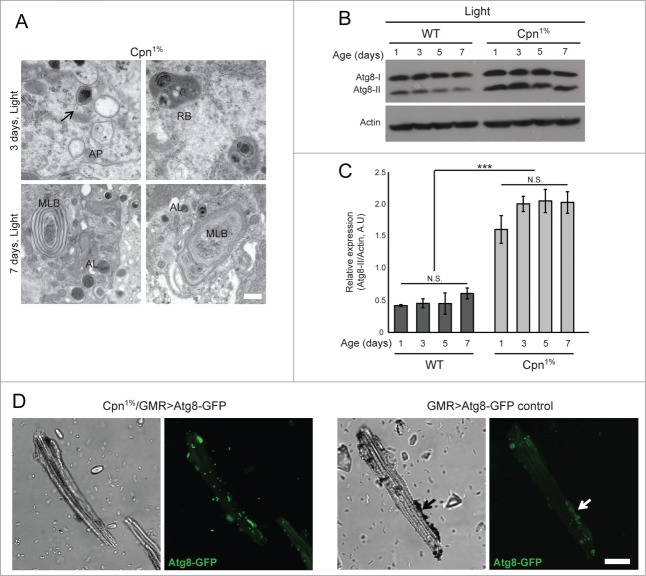

Elimination of calphotin caused severe age and light- dependent photoreceptor degeneration (Fig. 1). Moreover, reduction of calphotin expression also caused a pronounced upregulation of the photoreceptor autophagic machinery. Accordingly, high level of autophagy was detected by EM in light raised Cpn1% flies (Fig. 2A). Morphologic features typical of autophagosomes (AP) maturation were frequently and clearly observed in photoreceptor cells after various periods of illumination (Fig. 2, upper panel). Autophagosome appearance began with formation of double-membraned cisterns in the cytoplasm of Cpn1% flies (Fig. 2A, upper panel, arrow). The double-membraned cisterns enveloped cytoplasmic contents or entire organelles, forming APs (Fig. 2A, upper panel, AP). The formation of double membranes and APs was frequently seen as early as after 3 d of continuous illumination in Cpn1%. Vesicles containing semi-degraded material, possibly as a result of fusion between autophagosomes and lysosomes, were also found, forming either autophagolysosome or residual bodies (RB, Fig. 2A). Partially degraded cargo contents within RBs were manifested as unevenly distributed electron-dense particles (Fig. 2A, RB). In addition, after 7 d of continuous illumination, the characteristic concentric multi-lamellar and membrane whorls structures (Fig. 2A, lower panel) and the electron-dense inclusions of autolysosomes were observed (Fig. 2A, lower panel, AL) in Cpn1% flies. The later structures were frequently seen in the cytoplasm of Cpn1% flies (Fig. 2A, lower panel) representing the end of cell organelle/cytoplasm digestion by the autophagy pathway.15 In contrast, no similar structures were observed in WT and “CalX rescue” flies raised under identical conditions, or in dark raised Cpn1%.9

Figure 2.

Enhanced autophagy in Cpn1% flies. (A) Thin EM sections of single ommatidia. High magnification shows autophagosomes (AP)/ autolysosomes (AL) and multi lamellar bodies (MLB) formation in Cpn1% flies raised for 3 or 7 d in constant illumination (Bar = 500 nm, N = 3 flies). (B) Atg8 (Drosophila LC3 homolog) was quantified using Western blot analysis. Flies were raised in constant bright illumination to induce light-dependent retinal degeneration. Imunoblots of Atg8 (I and II) showed a total enhancement in Atg8 expression in Cpn1% relative to WT flies. Enrichment of Atg8-II was observed in Cpn1% relative to WT flies at all ages (∼1.5-2 fold increase, n = 3 experiments, each lane is N = 5 heads). (C) A histogram comparing the expression of lipidated Atg8 (Atg8-II) normalized to actin expression (n = 3 experimental runs, data is presented as average ± SEM ). Since there were no significant changes in the abundance of Atg8-II between different age groups (both WT and Cpn1%), the data for each genotype were pooled together. When comparing the pooled data, the elevation in Atg8-II in Cpn1% photoreceptors was highly significant (student T-test, P < 0 .005). (D) Confocal images of single ommatidia from 1 day old Cpn1%/GMR>Atg8-GFP fly raised under constant illumination showing noticeable accumulation of GFP-Atg8 puncta (left panel, showing a transmission and fluorescence channels), and from 1 day old GMR>Atg8-GFP/+ control fly raised under the same conditions, showing relatively rare accumulations of GFP-Atg8 puncta (right panel). (Bar = 100 μm, N = 3 flies). Note the enhanced appearance of autophagosomes only in the remaining debris of the pigment cells (lower panel, arrows).

The elongation of the double-membraned cisterns results in the cleavage and lipidation of the microtubule associated protein 1 light chain 3 protein (LC3, called Atg8 in Drosophila). The lipid tail enables LC3-II insertion into the membranes of the forming autophagosomes.16 LC3-II resides on autophagosomes until lysosomal fusion,17 and hence can serve as a marker for autophagosome formation.18 To confirm that the autophagic machinery is indeed up-regulated in light-raised Cpn1% flies, the distribution of the autophagy marker Atg8 was explored by biochemical and confocal microscopic analyses of photoreceptor cells. Western blot analysis showed a total elevation in Atg8 protein expression level and a drastic up-regulation of lipidated Atg8 (Atg8-II, ∼1.5–fold2- increase) in Cpn1% flies relative to WT control under identical conditions (Fig. 2B, C). The changes in the expression level and protein distribution between Atg8-I and Atg8-II were not age-related, suggesting that the autophagy flux is unaffected and there is no autophagosome accumulation due to perturbation in the autophagy process. This conclusion was also supported by the appearance of electron-dense inclusions of autolysosomes, representing the end of cell organelle/cytoplasm digestion by the autophagy pathway (Fig. 2A, lower panel, AL). Confocal images of isolated single ommatidia from 1 day old Cpn1%/GMR>Atg8-GFP fly raised under constant illumination, showed accumulation of GFP-Atg8 puncta representing Atg8II localization to the forming autophagosomes (Fig. 2D, left panel). Atg8 punctuation was observed as early as 1 hour post eclosion, whereas GFP-Atg8 puncta were rarely observed in control (GMR>Atg8-GFP/+) flies of the same age (Fig. 2D, right panel, note that enhanced autophagy is observed only in the remaining debris of the pigment (glia) cell, arrows). These results indicate that elimination of calphotin expression leads to cellular stress which activates autophagy. Together, our results revealed a constitutive enhancement of the autophagic flux in Cpn-depleted cells.

It was previously shown that elevated cellular Ca2+ level induce autophagy19 and that autophagy is related to cell death in a Drosophila model of neurodegenerative disease.20 Thus, the enhanced appearance of autophagosomes in photoreceptor cells of Cpn1% flies found in the present study is consistent with the observed elevated Ca2+ levels and reduced cell viability reported in our previous study.9

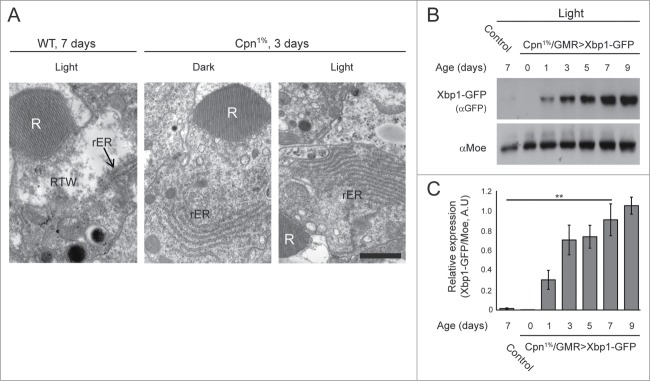

Activation of ER-stress in Cpn1% flies

The degeneration observed in Cpn1% flies, following 7 d illumination was accompanied by an unusually large accumulation of rough-ER (rER) in the cytoplasm adjacent to the rhabdomere. Furthermore, the rest of the Cpn1% photoreceptor cell body appeared inundated with rER relative to WT photoreceptors (Fig. 3A, right). Similar accumulation of rER was observed in dark raised Cpn1% flies, although to a lesser extent (Fig. 3A, middle). In WT flies, massive ER accumulations were rarely detected, even after 7 d of intense illumination and endoplasmic reticulum was distributed along the entire length of the photoreceptor cell body, outside the retinal terminal web (RTW, Fig. 3A, left). The pronounced accumulation of rER in Cpn1% flies may imply that the elimination of calphotin leads to the induction of ER-stress.

Figure 3.

Activation of ER-stress in Cpn1% flies. (A) Thin EM sections showing accumulation of rER in Cpn1% flies (middle and right panels) but not in WT (left panel, rER is indicated with an arrow). (N = 3 flies for each genotype and treatment, Bar = 1 μm). (B) Western blot analysis for the ER-stress marker, XBP1-GFP (using an α-GFP antibody) showing elevation in the ER-stress response (each lane is N = 5 heads). (C) A histogram comparing relative expression levels of XBP1-GFP, normalized to moesin expression (n = 2 experimental runs, data is presented as average ±stdev , ANOVA analysis P < 0 .005). The expression level of XBP1 is significantly higher in Cpn1% 7days samples vs. WT 7days samples (student T-test, P < 0 .01, **).

The Drosophila xbp1 mRNA undergoes unconventional splicing in response to ER-stress. This property was used by Ryoo et al. to develop a specific ER-stress marker, in which eGFP is expressed in frame only after ER-stress (xbp1-GFP).4 This marker was used in the present study to detect ER-stress induction in illuminated Cpn1% photoreceptor cells. Interestingly, the expression level of the ER marker, XBP1-GFP, increased with age. In control flies (GMR>xbp1-GFP/+) only minor basal expression of the marker was observed after 7 d of continuous illumination (Fig. 3B–C, control). These results revealed activation of ER-stress response in Cpn-depleted cells.

Together, the induction of autophagy and ER-stress pathways in Cpn1% flies, in which Ca2+ homeostasis is impaired; indicate that elimination of calphotin activates cellular mechanisms, which are known to operate under stressful conditions. Thus, when cell survival is threatened, leading to reduced photoreceptor cells viability and retinal degeneration, both autophagy and ER-stress responses are triggered, most likely, by the abnormally elevated cytosolic [Ca2+].

Discussion

Autophagy and ER-stress are highly conserved during evolution as many other essential cell maintenance pathways.21,22 Autophagy has been implicated in several pathologies, including protein aggregate disorders, neurodegeneration and cancer.23 Both autophagy and ER-stress are commonly associated with degenerative pathologies, but their role in disease progression is still a matter of debate. Many human genes, implicated in degenerative diseases, have orthologs in Drosophila. Studies in fly models have identified novel factors that regulate these diseases; therefore, Drosophila is a powerful model system for studying these genes.24,25 An illuminating example is the Drosophila model for class III autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa (ADRP),4 in which ER-stress was shown to be activated, playing a protective role against retinal degeneration. Moreover, it was shown that when Drosophila cells (both photoreceptors and S2 cells) were pre-exposed to a mild ER-stress, they were protected from treatments with various cell death agents.26 It was also shown recently that activation of mild ER stress is neuroprotective, both in Drosophila and mouse models of Parkinson disease, and this protection was shown to be a consequence of autophagy activation.27 Accordingly, it is well established that activation of the ER-stress response by accumulation of misfolded proteins (unfolded protein response, UPR) can triggers autophagy.24

It is well established that elevation of intracellular Ca2+ can trigger autophagy.18 The stimulation of autophagy by elevated cytosolic [Ca2+] was studied mainly in tissue cultured cells, in which mobilization of Ca2+ was triggered by application of various Ca2+ mobilizing agents (e.g. thapsigargin, ionomycin, vitamin D).28 However, since increased cytosolic [Ca2+] also activates ER-stress which induces autophagy, a question arises as to whether the activation of autophagy by Ca2+ is induced directly or indirectly via activation of ER-stress. The fact that thapsigargin-induced autophagy was shown to occur in UPR-deficient cells, suggests a direct involvement of Ca2+ in the induction of autophagy.29 Although Ca2+ regulation of autophagy was found to be mediated through the activation of Bcl-2 and calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase- β,19 the target by which Ca2+ activates autophagy directly is yet to be elucidated. These unsolved issues can be conveniently addressed in the new model of Ca2+ induced autophagy in Drosophila photoreceptor cells.

Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson, Alzheimer and Huntington's diseases are accompanied by the accumulation of large aggregates of mutant proteins and are autophagy associated diseases. These autophagy associated diseases, which are characterized by abnormal protein aggregations, have highly developed model systems of Drosophila. The increased autophagosome formation observed in these diseases, may play a protective role by degrading misfolded proteins.25 Many of the above diseases, including Parkinson and Alzheimer diseases, are also associated with reduced cellular Ca2+ buffering and impairments in cellular Ca2+ homeostasis30,31 reminiscent of Drosophila photoreceptors with reduced calphotin. Therefore, combining the Drosophila models of autophagy associated diseases with calphotin hypomorph can be very useful for studying the possible link between reduced cellular Ca2+ buffering and neurodegeneration.

In the genetic fly model of calphotin hypomorph,9 reduced calphotin levels, which trigger changes in cellular Ca2+ homeostasis allows induction of Ca2+ induced autophagy, simply by changing the illumination conditions of the flies’ environment. Accordingly, both the severity and progression of the observed degeneration can be highly controlled and manipulated. The degeneration process of this experimental model is sufficiently slow, allowing monitoring the progression of the degeneration process and elucidation of the involved proteins. Thus, the Drosophila Cpn hypomorph photoreceptor cells, constitutes a powerful model, in which genetic manipulation combined with illumination determine the level of sustained cellular Ca2+ that trigger the induction of Ca2+ dependent autophagy, ER- stress and cell death. This model can provide a framework for further investigations into the link between cytosolic Ca2+, ER-stress and autophagy in human disorders and diseases.

Materials and Methods

Fly stocks

Flies were raised at 24°C in a 12 h dark/light cycle. For the EM experiments flies were raised either in darkness to prevent light induced retinal deformations or under intense illumination. The CantonS, Rh1:Gal4 and Atg8-GFP fly stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. White-eyed GMR:Gal4 flies were a gift from A. Huber. Red-eyed GMR:Gal4 flies were obtained from J. Yoon. CalX over expression strain was obtained from R. Hardie. Xbp1-GFP flies were a kind gift from P. Domingos. Calphotin transgenic strains were generated as described in our previous study.9 For determination of light dependent retinal degeneration, flies were kept in the dark, or were illuminated with white light (Schott NG3 heat filter, cold light source KL1500, Schott, Germany) for 3–14 d Dark raised flies were dissected under dim red light (Schott RG 620, cold light source KL1500, Schott, Germany).

Western blots

Flies were collected at the age mention in the text. To detect XBP1-GFP and Atg8, 5 fly heads were homogenized in a buffer solution (150 mM NaCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, protease inhibitor, 50 mM HEPES pH = 7.4) and separated by SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred for 2 hr at 70-80 mA to BioTraceTM PVDF membranes (Pall Corporation) in Tris-glycine buffer. The blots were probed with anti-GFP (poly-clonal, 1:1,000 dilution, novagen), anti-Atg8 (poly-clonal, 1:2,000, a kind gift from Katja Köhler) or control antibodies and subsequently with goat anti-mouse/rabbit IgG peroxidase conjugate. Signals were detected using ECL reagents (Biological Industries). An αMoesin32 (αMoe, 1:10,000) and an αActin (1:1,000 dilution) antibodies were used as a loading control. Blots were quantified using imageJ software.

Electron microscopy

For all EM experiments Cpn-RNAi and CantonS (WT) flies were used. For the deformation/degeneration experiment flies were divided into 2 groups before eclosion. One of them was raised at complete darkness while the other was raised at intense illumination conditions during the same period. Fly heads were separated and bisected longitudinally from flies at different ages: newly-eclosed, 3, 7 or 14 d old. Tissues including compound eyes were dissected out of the flies in fixative solution (5% glutaraldehyde, 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH = 7.4) and incubated overnight. Samples were then postfixed (1% OsO4, 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH = 7.4), dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol, and embedded in epoxy resin. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, were observed with a Tecnai-12 transmission electron microscope (FEI) and photographed with a Mega-view II charge-coupled device camera (Philips).For all experiment at least 3 heads were dissected (N ≥ 3 flies) and analyzed (n ≥ 5 sections).

Confocal microscopy

Dissected live retinas were visualized using the Fluoview confocal microscope (model 300 IX70; Olympus) using an Olympus UplanF1 60x/0.9 water objective. Optical sections were recorded from the middle of the cell. GFP fluorescence and bright field images were recorded sequentially.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Katja Koehler and Françios Payre for the kind gift of antibodies against Atg8 and dMoesin, respectively. We also thank Dr. Pedro Domingos for the Drosophila xbp1-GFP strain and valuable discussions. We also thank Dr. Bertrand Mollereau for valuable discussions, Ben Katz for critical reading of the manuscript and Ms. Noami Feinstein for extensive help in the EM studies.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the National Eye Institute (R01 EY 03529), the Israel Science Foundation (ISF) and the Deutsch-lsraelische Projektkooperation (DIP).

References

- 1. Gambis A, Dourlen P, Steller H, Mollereau B. Two-color in vivo imaging of photoreceptor apoptosis and development in Drosophila. Dev Biol 2011; 351:128-34; PMID:21215264; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mollereau B, Domingos PM. Photoreceptor differentiation in Drosophila: from immature neurons to functional photoreceptors. Dev Dyn 2005; 232:585-92; PMID:15704118; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/dvdy.20271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mollereau B. Cell death: what can we learn from flies? Editorial for the special review issue on Drosophila apoptosis. Apoptosis 2009; 14:929-34; PMID:19629695; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10495-009-0383-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ryoo HD, Domingos PM, Kang MJ, Steller H. Unfolded protein response in a Drosophila model for retinal degeneration. EMBO J 2007; 26:242-52; PMID:17170705; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xu D, Woodfield SE, Lee TV, Fan Y, Antonio C, Bergmann A. Genetic control of programmed cell death (apoptosis) in Drosophila. Fly (Austin) 2009; 3:78-90; PMID:19182545; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/fly.3.1.7800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hardie RC, Raghu P. Visual transduction in Drosophila. Nature 2001; 413:186-93; PMID:11557987; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/35093002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Katz B, Minke B. Drosophila photoreceptors and signaling mechanisms. Front Cell Neurosci 2009; 3:2; PMID:19623243; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3389/neuro.03.002.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hardie RC, Minke B. The trp gene is essential for a light-activated Ca2+ channel in Drosophila photoreceptors. Neuron 1992; 8:643-51; PMID:1314617; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90086-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weiss S, Kohn E, Dadon D, Katz B, Peters M, Lebendiker M, Kosloff M, Colley NJ, Minke B. Compartmentalization and Ca2+ Buffering Are Essential for Prevention of Light-Induced Retinal Degeneration. J Neurosci 2012; 32:14696-708; PMID:23077055; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2456-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang T, Xu H, Oberwinkler J, Gu Y, Hardie RC, Montell C. Light activation, adaptation, and cell survival functions of the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger CalX. Neuron 2005; 45:367-78; PMID:15694324; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yoon J, Ben-Ami HC, Hong YS, Park S, Strong LL, Bowman J, Geng C, Baek K, Minke B, Pak WL. Novel mechanism of massive photoreceptor degeneration caused by mutations in the trp gene of Drosophila. J Neurosci 2000; 20:649-59; PMID:10632594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jing K, Lim K. Why is autophagy important in human diseases? Exp Mol Med 2012; 44:69-72; PMID:22257881; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3858/emm.2012.44.2.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marciniak SJ, Ron D. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling in disease. Physiol Rev 2006; 86:1133-49; PMID:17015486; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/physrev.00015.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Forman MS, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. 'Unfolding' pathways in neurodegenerative disease. Trends Neurosci 2003; 26:407-10; PMID:12900170; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00197-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu CL, Chen S, Dietrich D, Hu BR. Changes in autophagy after traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008; 28:674-83; PMID:18059433; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Geng J, Klionsky DJ. The Atg8 and Atg12 ubiquitin-like conjugation systems in macroautophagy. 'Protein modifications: beyond the usual suspects' review series. EMBO Rep 2008; 9:859-64; PMID:18704115; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/embor.2008.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ravikumar B, Sarkar S, Davies JE, Futter M, Garcia-Arencibia M, Green-Thompson ZW, Jimenez-Sanchez M, Korolchuk VI, Lichtenberg M, Luo S, et al. Regulation of mammalian autophagy in physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol Rev 2010; 90:1383-435; PMID:20959619; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/physrev.00030.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Decuypere JP, Bultynck G, Parys JB. A dual role for Ca(2+) in autophagy regulation. Cell Calcium 2011; 50:242-50; PMID:21571367; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoyer-Hansen M, Bastholm L, Szyniarowski P, Campanella M, Szabadkai G, Farkas T, Bianchi K, Fehrenbacher N, Elling F, Rizzuto R, et al. Control of macroautophagy by calcium, calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-beta, and Bcl-2. Mol Cell 2007; 25:193-205; PMID:17244528; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang T, Lao U, Edgar BA. TOR-mediated autophagy regulates cell death in Drosophila neurodegenerative disease. J Cell Biol 2009; 186:703-11; PMID:19720874; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200904090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klionsky DJ, Abeliovich H, Agostinis P, Agrawal DK, Aliev G, Askew DS, Baba M, Baehrecke EH, Bahr BA, Ballabio A, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy in higher eukaryotes. Autophagy 2008; 4:151-75; PMID:18188003; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.5338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Neufeld TP, Baehrecke EH. Eating on the fly: function and regulation of autophagy during cell growth, survival and death in Drosophila. Autophagy 2008; 4:557-62; PMID:18319640; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.5782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McPhee CK, Baehrecke EH. Autophagy in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochim Biophys Acta 2009; 1793:1452-60; PMID:19264097; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yorimitsu T, Nair U, Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. Endoplasmic reticulum stress triggers autophagy. J Biol Chem 2006; 281:30299-304; PMID:16901900; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M607007200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yuan J, Lipinski M, Degterev A. Diversity in the mechanisms of neuronal cell death. Neuron 2003; 40:401-13; PMID:14556717; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00601-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mendes CS, Levet C, Chatelain G, Dourlen P, Fouillet A, Dichtel-Danjoy ML, Gambis A, Ryoo HD, Steller H, Mollereau B. ER stress protects from retinal degeneration. EMBO J 2009; 28:1296-307; PMID:19339992; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/emboj.2009.76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fouillet A, Levet C, Virgone A, Robin M, Dourlen P, Rieusset J, Belaidi E, Ovize M, Touret M, Nataf S, et al. ER stress inhibits neuronal death by promoting autophagy. Autophagy 2012; 8:915-26; PMID:22660271; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4161/auto.19716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hoyer-Hansen M, Jaattela M. Connecting endoplasmic reticulum stress to autophagy by unfolded protein response and calcium. Cell Death Differ 2007; 14:1576-82; PMID:17612585; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sakaki K, Wu J, Kaufman RJ. Protein kinase Ctheta is required for autophagy in response to stress in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 2008; 283:15370-80; PMID:18356160; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M710209200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Riascos D, de Leon D, Baker-Nigh A, Nicholas A, Yukhananov R, Bu J, Wu CK, Geula C, et al. Age-related loss of calcium buffering and selective neuronal vulnerability in Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol 2011; 122:565-76; PMID:21874328; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00401-011-0865-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Selvaraj S, Sun Y, Watt JA, Wang S, Lei S, Birnbaumer L, Singh BB. Neurotoxin-induced ER stress in mouse dopaminergic neurons involves downregulation of TRPC1 and inhibition of AKT/mTOR signaling. J Clin Invest 2012; 122:1354-67; PMID:22446186; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1172/JCI61332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chorna-Ornan I, Tzarfaty V, Ankri-Eliahoo G, Joel-Almagor T, Meyer NE, Huber A, et al. Light-regulated interaction of Dmoesin with TRP and TRPL channels is required for maintenance of photoreceptors. J Cell Biol 2005; 171:143-52; PMID:16216927; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1083/jcb.200503014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]