Abstract

Our recent studies implicate the transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) channel as a mediator of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) function and survival. With elevated pressure in the eye, TRPV1 increases in RGCs, supporting enhanced excitability, while Trpv1 -/- accelerates RGC degeneration in mice. Here we find TRPV1 localized in monkey and human RGCs, similar to rodents. Expression increases in RGCs exposed to acute changes in pressure. In retinal explants, contrary to our animal studies, both Trpv1 -/- and pharmacological antagonism of the channel prevented pressure-induced RGC apoptosis, as did chelation of extracellular Ca2+. Finally, while TRPV1 and TRPV4 co-localize in some RGC bodies and form a protein complex in the retina, expression of their mRNA is inversely related with increasing ocular pressure. We propose that TRPV1 activation by pressure-related insult in the eye initiates changes in expression that contribute to a Ca2+-dependent adaptive response to maintain excitatory signaling in RGCs.

Keywords: glaucoma, mechanosensation, neurodegeneration, optic nerve, retina, retinal ganglion cell, TRPV1, TRPV4

Abbreviations

- TRPV1

transient receptor potential vanilloid-1

- TRPV4

transient receptor potential vanilloid-4

- IRTX

iodo-resinferatoxin

- CAP

capsaicin

- EGTA

ethyleneglycol-bis(B-aminoethyl)-N, N, N1, N1-tetraacetic acid

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling)

Introduction

Activation of the transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 (TRPV1) channel modulates a variety of Ca2+-dependent cascades that influence the transduction of physical stimuli necessary for sensory function, including mechanical, thermal and tactile information.1-4 Levels of expression and subcellular localization of TRPV1 are highly mutable, leading us to propose a role for the channel in mediating neuronal and glial responses to disease-relevant stressors.5 In other systems, TRPV1 is upregulated with activation and undergoes translocation to the plasma membrane, where it increases post-synaptic neurite activity and survival.6-9 TRPV1 can be activated and/or sensitized either directly by mechanical stress or by endogenous ligands like endocannabinoids and growth factors.6,10-12 TRPV1-gated Ca2+ promotes spontaneous excitation and potentiates post-synaptic responses to glutamate.13-17 Phosphorylation of TRPV1 promotes sensitization, continued translocation, and increased depolarization.18 The channel can be desensitized by dephosphorylation via the calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase, calcineurin, or by re- internalization.19

In a series of recent studies, we focused on probing novel roles for TRPV1 in neuronal and glial function in the retina and optic projection to the brain. We demonstrated that pharmacological antagonism of TRPV1 in isolated astrocytes decelerates Ca2+ -dependent migration in response to mechanical injury.20 We have also described an important and complex role for TRPV1 in modulating the physiology of retinal ganglion cell (RGC) neurons, whose axons comprise the optic nerve. These neurons are specifically vulnerable to injury related to ocular pressure, due to stress transferred to the unmyelinated segment of the axon as it passes from the retina to the nerve head.21,22 This sensitivity to pressure-related stress underlies the degeneration of RGCs in glaucoma, the world's most prevalent age-related neuropathy and leading cause of irreversible blindness. Early on, we found that pharmacological antagonism of TRPV1 in isolated RGCs exposed to elevated pressure in vitro prevented both increased intracellular Ca2+ and apoptosis.23 Based on these results, we proposed that TRPV1 is a critical and early mediator of pressure-dependent RGC degeneration in glaucoma, perhaps via direct transduction of membrane stress.23 This hypothesis is consistent with a broader role for Ca2+dependent cascades in mediating progression of neurodegeneration in glaucoma and other diseases.24

TRPV1 in the retina is expressed in a variety of neuronal and glial cell types, as are other TRP subunits.23,25-33 Because of this complexity, discerning how TRPV1 exerts its influence in vivo is more difficult. We discovered recently in testing our initial hypothesis that both knock-out and pharmacological antagonism of TRPV1 accelerated RGC degeneration with exposure to elevated intraocular pressure in an inducible model of glaucoma.34 Furthermore, RGCs from Trpv1-/- retina lacked a compensatory, transient increase in spontaneous action potentials with elevated pressure and required greater depolarization to reach firing threshold.34 Thus, we proposed that TRPV1 in response to pressure-related stress in vivo acts to boost excitatory activity as a way of promoting RGC survival in glaucoma.34 In support of this hypothesis, additional results from our laboratory indicate that TRPV1 expression and localization in RGCs increases with short-term exposure to elevated ocular pressure and supports an enhanced excitatory influence on RGC activity.35

Here we supplement our recent investigations by further characterizing the pattern of TRPV1 expression in RGCs and its influence on their survival. We report that like their rodent counterparts, RGCs in non-human primate and human retina express TRPV1 abundantly. While levels of Trpv1 mRNA are highly variable between retinas, expression increases in RGCs stressed by pressure. Contrary to our in vivo results,34 for adult retinal explants maintained ex vivo, we found that both pharmacological antagonism of TRPV1 and Trpv1-/- improved RGC survival with exposure to elevated hydrostatic pressure, as did chelation of extracellular Ca2+. Interestingly, while TRPV1 co-localizes and forms a protein complex with TRPV4, in the DBA2J mouse model of glaucoma, expression of mRNA encoding the 2 subunits is inversely related as ocular pressure increases. Thus, different TRPV subunits are likely to contribute in different ways to the RGC response to ocular stress in diseases such as glaucoma.

Results

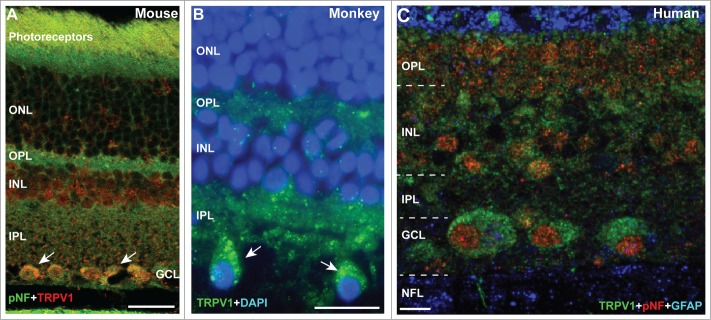

TRPV1 in retinal ganglion cell neurons supports increased intracellular Ca2+

Recently we demonstrated that levels of TRPV1 increase with elevated intraocular pressure in an inducible mouse model of glaucoma.35 In normal tissue, TRPV1 localizes diffusely in both synaptic layers and in punctate pockets within RGC bodies for C57 mouse, macaque and human retina (Fig. 1A-C). These results are consistent with our previous studies of rodent retina, including the DBA2J mouse model of hereditary glaucoma.23,35 Localization in human RGCs was slightly more diffuse in the cytoplasm than in macaque.

Figure 1.

TRPV1 Expression in Retinal Ganglion Cell Neurons. (A) Immuno-labeling for TRPV1 in mouse retina shows strong localization in the outer and inner plexiform layers (OPL and IPL, respectively) and in peri-nuclear compartments of RGC bodies co-labeled against phosphorylated neurofilaments (pNF). In macaque monkey retina (B), RGCs (large cells) demonstrate discrete pockets of TRPV1 localization (arrows), while in aged human retina (C) TRPV1 distributes throughout the RGC cytoplasm. Scale = 20 μm (A, B) or 10 μm (C).

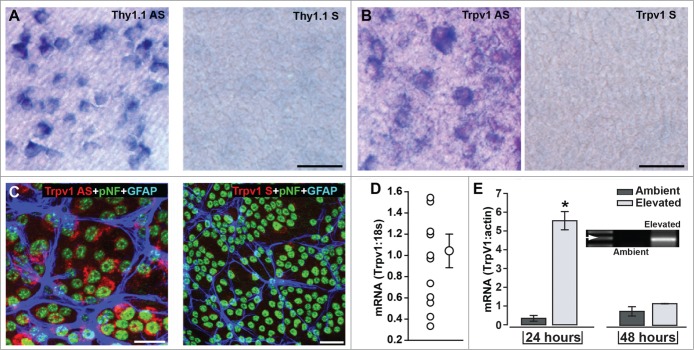

Using in situ hybridization for RGC-specific Thy1 mRNA for comparison (Fig. 2A), Trpv1 mRNA distributed more modestly in the RGC layer of C57 retina (Fig. 2B). Roughly 70% of RGCs immuno-labeled for phosphorylated neurofilaments show Trpv1 mRNA signal compared to the control sense sequence (Fig. 2C). Quantitative RT-PCR showed that Trpv1 mRNA expression was highly variable between naïve C57 retinas compared to a control sequence, varying over a 4-fold range of values (Fig. 2D). In contrast, for isolated RGCs maintained in culture, Trpv1 expression was enhanced 12-fold by short-term (24 hr) exposure to elevated hydrostatic pressure (+70 mmHG) with little variability between preparations (Fig. 2E). By 48 hrs of pressure, which doubles RGC apoptosis,23 Trpv1 levels were identical to ambient conditions. Thus, while normal Trpv1 message may be relatively low and variable, under conditions that stress RGCs, expression rises considerably.

Figure 2.

Trpv1 mRNA in Retinal Ganglion Cell Neurons. (A) In situ hybridization using anti-sense (AS) sequence for RGC-specific Thy1.1 in whole-mounted C57 retina labels nearly every RGC compared to the control sense sequence (right). Anti-sense label for Trpv1 (B) in C57 labels fewer cells in ganglion cell layer (sense probe shown for comparison, right). (C) Fluorescent in situ hybridization probe for Trpv1 mRNA combined with immune-labeling for RGCs (pNF) and astrocytes (GFAP) shows strong anti-sense signal in roughly 70% of RGCs compared to the control sense sequence (right). (D) Quantitative RT-PCR detection of Trpv1 mRNA compared to 18s in individual naïve C57 retinas shows large inter-retina variability (mean ± sem is shown for comparison: 1.04 ± 0.17, n = 12). (E) Conventional RT-PCR product for Trpv1 mRNA in isolated RGCs maintained in culture (inset) shows significant increase following 24 hr exposure to elevated hydrostatic pressure (+70 mmHG; *, P < 0.001). By 48 hrs, expression had returned to ambient levels. Scale = 40 μm (B) or 20 μm (C).

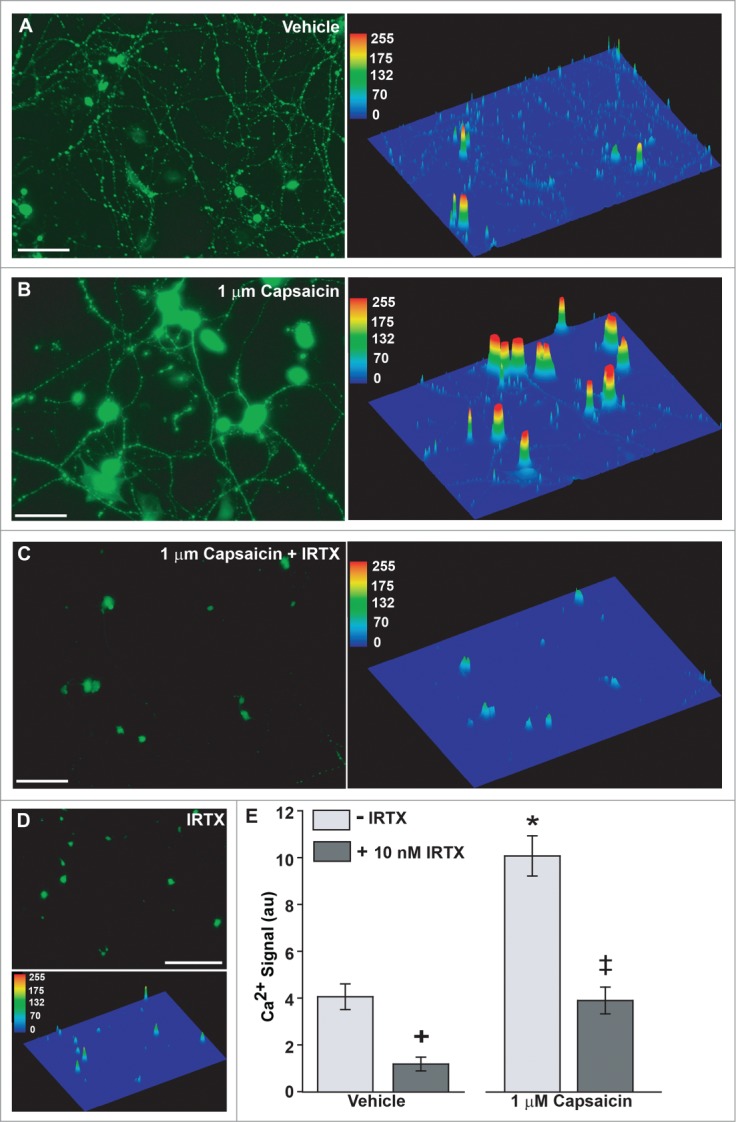

TRPV1 gates a robust Ca2+ conductance upon activation.36-40 Earlier we found that one hour of hydrostatic pressure (+70 mmHg) increases by 4-fold accumulated intracellular Ca2+ as measured by Fluo-4 AM; this increase was reduced 40% by blocking TRPV1 with the subunit-specific antagonist iodo-resinferatoxin (IRTX42, 10 nM).23 Here, in untreated RGCs, Fluo-4 signal was nearly uniform across the field, with modest accumulation in cell bodies overlying a meshwork of highlighted dendrites (Fig. 3A). Activation of TRPV1 with 1 μM capsaicin (CAP) for one hour increased Fluo-4 label in both RGC bodies and neurites (Fig. 3B). Co-application with IRTX (10 nM) eliminated nearly all Fluo-4 accumulation (Fig. 3C). That a similar result was obtained in RGCs without CAP (Fig. 3D) indicates that TRPV1 contributes to basal levels of intracellular Ca2+. Quantification of total Fluo-4 intensity indicated a 2.5-fold increase with CAP treatment (P < 0.01), consistent with our previous results.35 This increase was reduced 62% by co-treatment with IRTX (P < 0.01; Fig. 3E). The 73% reduction of baseline intracellular Ca2+ in RGCs with IRTX alone was also significant (p = 0.04).

Figure 3.

TRPV1 Activation Increases RGC Intracellular Ca2+. (A) Fluo-4 conjugated Ca2+ accumulates in RGC cell bodies and neurites. Quantification with intensity map (right panel) shows a consistent network of neurites outlined by small puncta of low Ca2+ accumulation. (B) RGCs treated for 1 hour with 1 μM capsaicin (CAP) demonstrate increased Ca2+ in the cell body and primary neurites, with lower accumulation in background neurites (right panel). (C) RGCs treated for 1 hour with both 1 μM CAP and 10 nM of the TRPV1-specific antagonist IRTX show greatly diminished Ca2+ accumulation, especially in neurites, where Fluo-4 signal is almost completely absent. (D) Treatment with 10 nM IRTX alone eliminates most Ca2+ signal. E. Quantification of Fluo-4 signal indicates a significant increase with CAP compared to vehicle (*). IRTX significantly reduces signal relative to vehicle (+) and CAP-treated RGCs (‡). Symbols indicate P ≤ 0.05; error bars represent standard error. Pixel intensity calculated as average of total intensity from 15–20 independent fields. N = 3 preparations per condition. Scale = 100 μm (A-C) or 150 μm (D).

TRPV1 contributes to the detection of RGC stress

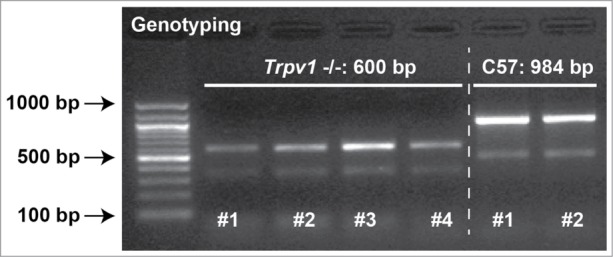

Our published finding that RGC degeneration in vivo is accelerated both by Trpv1-/- and pharmacological antagonism of TRPV1 could be explained be enhanced sensitivity to stress related to ocular pressure. If correct, such an enhancement when TRPV1 is silenced obviously would challenge our original hypothesis that TRPV1 contributes to RGC sensitivity to mechanical stress in glaucoma.23 To probe this relationship further, we prepared retinal explants from C57 and Trpv1 -/- mice and exposed them in parallel to increased hydrostatic pressure ex vivo. The Trpv1 -/- mouse is a germ-line mutation that was created by deletion of an exon encoding part of the fifth and all of the sixth transmembrane domains of the TRPV1 channel, including the pore-loop region between the 2.43 With the primer combination we used for conformational genotyping (see Methods), wild-type C57 mice yield a product size of 984 base pairs while Trpv1-/- mice yield a truncated product of 600 base pairs (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Trpv1-/- Mice Express Truncated Form of Gene. Agarose gel showing PCR products from genotyping 4 Trpv1-/- and 2 C57 mice used in our experiments. Reaction products were 984 base pairs (bp) for C57 and 600 bp Trpv1-/- mice, as expected based on the truncated protein.

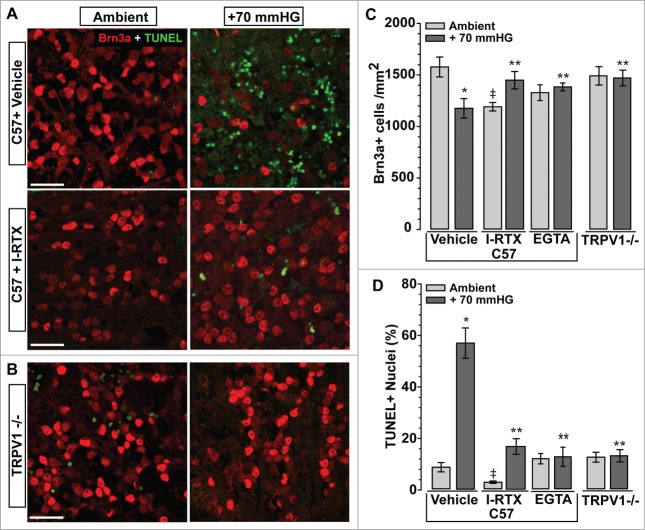

Previously we demonstrated that exposure to a 70 mmHG step of hydrostatic pressure for 48 hrs diminishes the survival of isolated RGCs by 40%, which is prevented by treatment with IRTX or chelation of extracellular Ca2+ with EGTA.44,23 In explants from adult C57 retina, 48 hrs of pressure caused a reduction in Brn3a-labeled RGCs and an increase in TUNEL-labeled apoptotic nuclei in the RGC layer; both were prevented by treatment with 10 nM IRTX (Fig. 5A). For explants from Trpv1-/- retina, pressure had little noticeable effect on either Brn3a label or TUNEL compared to ambient pressure (Fig. 5B). When quantified, these results were highly significant (Fig. 5C,D). On average, exposure to pressured reduced the density of Brn3a-labeled RGCs in C57 explants by 25%, while increasing the number of TUNEL-labeled nuclei 7-fold. Treatment with IRTX prevented the pressure-induced decrease in RGC density and significantly lowered the fraction of TUNEL+ nuclei compared to vehicle only (17 vs. 57%). For Trpv1-/- explants, RGC density at both ambient and elevated pressure was the same as C57 at ambient (P ≥ 0.39, Fig. 5C), as was TUNEL reactivity (P ≥ 0.16, Fig. 5D). As with isolated RGCs,23 treatment with EGTA (950 μM) also prevented the pressure-induced reduction in Brn3a-labeled RGCs and the increase in TUNEL+ cells (Fig. 5C,D).Thus, both pharmacological antagonism of TRPV1 and Trpv1-/- reduces the apoptotic response of RGCs exposed to elevated hydrostatic pressure, as does chelation of extracellular Ca2+, consistent with our results using isolated RGCs.23 Interestingly, while Trpv1-/- explants had similar density of Brn3a-labeled RGCs as C57 at ambient pressure, we found that IRTX treatment actually caused a slight decrease (Fig. 5C). Since the fraction of TUNEL+ cells was dramatically lower than vehicle explants (2 vs. 9%), this result is probably due to compromised explant integrity.

Figure 5.

TRPV1 Suppression Improves RGC Survival in Retinal Explants. (A) Confocal micrographs through ganglion cell layer of explants from C57 retina maintained ex vivo at either ambient or elevated (+70 mmHG) hydrostatic pressure for 48 hrs. Compared to vehicle (DMSO, top row), explants under pressure treated with the TRPV1-specific antagonist iodoresiniferatoxin (IRTX, 10 nM, bottom row) exhibit far fewer TUNEL+ nuclei (green) and no loss of Brn3a immune-labeled RGCs (red). (B) Explants from Trpv1-/- retina show similar density of Brn3a-labeled RGCs at 48 hrs of either ambient or elevated pressure and no increase in TUNEL with pressure.(C) Quantification of explants indicates a 25% reduction in Brn3a-labeled RGCs with pressure compared to ambient (*, p = 0.01). IRTX prevents the pressure-induced reduction in Brn3a-labeled RGCs compared to C57 (**, p = 0.02), but also reduces the number cells compared to vehicle at ambient pressure (‡, P < 0.001). EGTA (950 μM) reduces RGC loss in under pressure (**, p = 0.03), as does Trpv1-/- compared to C57 (**, p = 0.02). There was no difference between C57 and Trpv1-/- at ambient pressure (p = 0.4).(D) Fraction of TUNEL+ nuclei in the RGC layer of C57 explants is increased nearly 7-fold compared to ambient pressure (*, P < 0.001). IRTX treatment reduces TUNEL label compared to vehicle both at ambient (‡, p = 0.003) and elevated (**, P < 0.001) pressure. For explants under pressure, both EGTA and Trpv1-/- decrease TUNEL significantly compared to C57 with pressure (**P < 0.001). Scale = 20 μm (A,B).

Evidence for TRPV1 interaction with TRPV4

An important issue to resolve is whether TRPV1 exerts its influence on RGC physiology and survival on concert with any of the other TRPV subunits (TRPV2–6). Generally, TRP channel subunits can assemble into homo- or hetero-tetrameric channel complexes with physiological properties determined by subunit composition.45 Ankyrin repeat domains likely play a role in determining particular subunit interactions.46 A recent study indicated that RGCs in mouse retina express the TRPV4 subunit and that this channel, like TRPV1,35 contributes to increased intracellular Ca2+ upon activation by agonists or exposure to hypotonic stress.30 The same study also found TRPV4 expressed in Müller glia end-feet, just distal to RGC bodies.

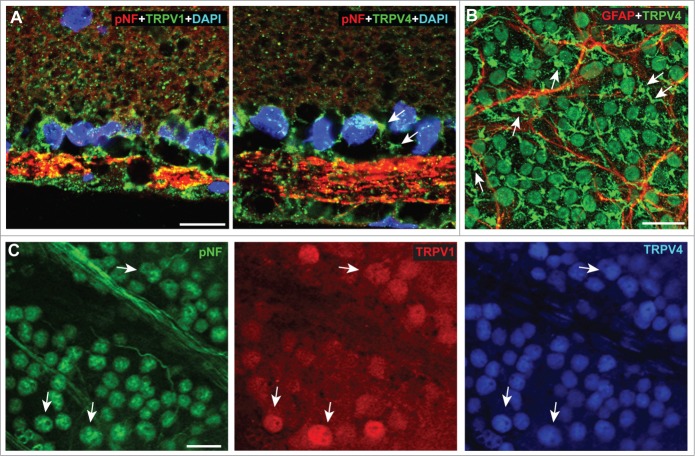

Here we confirm the localization of TRPV4 to RGCs and Müller glia in rat (Fig. 6A) and mouse (Fig. 6B) retina. Since TRPV1 is also expressed in RGCs, we co-labeled rat retina for TRPV4 and found some co-localization in RGCs visualized by immune-labeling against phosphorylated neurofilaments (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, in this preparation, TRPV4 label was more consistent across RGCs and generally stronger in individual cells, suggesting higher levels of TRPV4 expression than TRPV1.

Figure 6.

TRPV1 Co-localizes with TRPV4. (A) Vertical sections of rat retina show localization of TRPV1 (left) and TRPV4 (right) in RGCs whose axons are strongly labeled for phosphorylated neurofilaments (pNF). The pNF fluorescent signal has been decreased purposefully due to its high levels in axons. Arrows indicate likely localization of TRPV4 in Müller glia end-feet. (B) In whole-mount of C57 retina, TRPV4 localizes to most cell bodies of the ganglion cell layer and to Müller glia end-feet in between them (arrows). GFAP-labeled astrocytes are shown for comparison. (C) Rat retina labeled for TRPV1 and TRPV4 shows strong co-localization (arrows) in pNF-labeled RGCs.

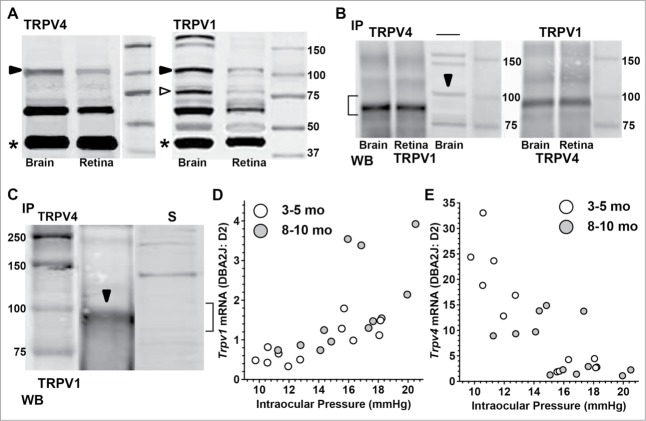

Western blots indicate, however, that protein levels of TRPV4 and TRPV1 are similar in retina, compared to levels of β-actin (Fig. 7A). Immuno-precipitation of TRPV4 from brain and retina protein extracts followed by western blot to probe for TRPV1 revealed that the 2 subunits form a complex in both structures (Fig. 7B, left). This interaction was confirmed by repeating the experiment in the reverse direction, that is, immuno-precipitation of TRPV1 followed by protein gel blot against TRPV4 (Fig. 7B, right). In both cases, the strongest reaction product is just under 100 kDa, probably reflecting the lower weight of the TRPV4 epitope (see Methods). We repeated in brain the immuno-precipitation of TRPV4 followed by western blot for TRPV1 and noted the same reaction product near 100 kDA (Fig. 7C). As a control, we found this particular reaction product missing, after probing the supernatant from the co-immuno-precipitation experiment once more for TRPV1(Fig. 7C). This indicates that the interaction with TRPV4 occurs with the full-length isoform of TRPV1. Our result is consistent with an earlier prediction showing that co-expression leads to TRPV1-V4 interaction as measured via fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) and single-channel recording.47 Control precipitation experiments in which the primary antibody for the protein gel blot was omitted yielded no product (not shown).

Figure 7.

TRPV1 Forms a Protein Complex with TRPV4. (A) Western blots from brain and retina for TRPV4 and TRPV1 with full-length product in expected range near 100 kDa (dark arrowhead). TRPV1 also shows strong product near 75 kDa (open arrowhead), consistent with earlier work.20 Product for β-actin (*, run simultaneously) is shown for comparison. Smaller products (∼60 kDa) likely represent protein degradation. (B) Western blots (WB) for TRPV1 (left) and TRPV4 (right) following immuno-precipitation (IP) of TRPV4 or TRPV1, respectively, from brain and retina extracts. Co-immuno-precipitation product for the TRPV4/TRPV1 complex (bracket) is the same whether the immuno-precipitate is TRPV4 (left) or TRPV1 (right) and is slightly less heavy than the WB product for TRPV1 for brain in the absence of IP (arrowhead). (C) Western blots for TRPV1 (brain) following immuno-precipitation (IP) of TRPV4 shows same reaction product near 100 kDa as before. When supernatant (S) from the co-immuno-precipitation reaction is probed again for TRPV1, this product is absent (bracket), supporting specific binding of the 100 kDa form of TRPV1 to TRPV4. (D) Quantitative PCR measurements of Trpv1 mRNA in young (3–5 mo) and aged (8–10 mo) DBA2J retina relative to levels in age-matched D2 control retina; both calculated relative to 18s rRNA. Trpv1 mRNA correlates significantly with intraocular pressure for the 3–5 mo group (r2 = 0.656, P < 0.001) but not for the 8–10 mo group (r2 = 0.17, p = 0.17). Some data modified from recent work.35 In contrast, while expression of Trpv4 mRNA is higher than Trpv1 (E), levels are inversely correlated with increasing pressure for the 3–5 mo group (r2 = 0.79, P < 0.001), but not for the 8–10 mo group (r2 = 0.26, p = 0.091)

Interestingly, in the DBA2J mouse model of glaucoma, Trpv1 and Trpv4 mRNA were inversely related as a function of increasing intraocular pressure, when calculated relative to expression in the D2 control strain (Fig. 7D,E). Both correlations were significant for young (3–5 mo) mice (P < 0.001). We reported earlier that older DBA2J retina (8–10 mo) had significantly higher Trpv1 expression when separated into low vs. high ocular pressure groups.35 For Trpv4, retinas from young eyes (3–5 mo) with lower pressure (9.8–12.8 mmHG) had significantly greater expression compared to retinas from eyes with higher pressures (15.6–18.2 mmHG) in the same age group: 21.6 ± 7.1 vs. 3.0 ± 1.1 (p = 0.002), both relative to expression in D2 control retinas (Fig. 7E). In older (8–10 mo) retinas from eyes with lower pressure (12.8–14.8 mmHG), Trpv4 also was higher compared to retinas from eyes with higher pressure (15.1–20.5 mmHG): 11.3 ± 2.8 vs. 3.5 ± 4.5 (p = 0.018), relative to D2 expression. Age itself also diminished Trpv4 expression for both the low pressure (p = 0.01) and high pressure (p = 0.03) groups.

Discussion

The contribution of TRP subunits to retinal function is complex and seemingly ever-growing in diversity.5,48,49 Our group has focused on expression RGC neurons and their axons, because of their susceptibility to pressure-related stress in glaucoma, a leading cause of blindness that is associated with sensitivity to intraocular pressure.50,51,22 We and others have found that RGCs express a number of TRP channels, including the vanilloid subunits TRPV1 and TRPV4, which we have focused on in this paper.23,26,28-30,33,35 This is so for both rodent and primate retina (Fig. 1). TRPV1 also contributes to diverse Ca2+-dependent functions in retinal glial cells, including astrocyte responses to mechanical stress and microglial release of interleukin-6, which is protective of RGCs exposed to pressure in vitro.20,27,37 The channel may also contribute to Müller glia reactivity in the retina following optic nerve insult.32

Interestingly, we found that expression of Trpv1 mRNA in retina is quite variable from eye to eye in naïve mice (Fig. 2). We have summarized elsewhere evidence that TRPV1 mediates diverse neuronal and glial responses to insult or stress.5 Such a role is consistent with our recent finding that TRPV1 expression increases in RGCs in response to elevated intraocular pressure in vivo.35 Here we demonstrate a similar result for Trpv1 mRNA in isolated RGCs exposed to a hydrostatic pressure load in vitro (Fig. 2). Our single-unit electrophysiology studies suggests that one purpose of increased TRPV1 expression is to enhance membrane excitability, a property missing in Trpv1 -/- mice.35 This enhancement is likely mediated by Ca2+ currents, since activation of TRPV1 in RGCs increases intracellular Ca2+ in isolated RGCs,35, a result we replicate here (Fig. 3).

We have proposed that TRPV1 mediates a form of RGC self-repair to slow degeneration in response to elevated ocular pressure, since progression is accelerated in Trpv1 -/- mice.34 Why, then, do we find that Trpv1-/- reduces RGC degeneration in explants exposed to pressure (Fig. 5)? This is analogous to our earlier result showing that TRPV1 antagonism with IRTX blunts apoptosis of isolated RGCs exposed to hydrostatic pressure in culture.23 In both preparations, chelating extracellular EGTA is also protective of RGCs (Fig. 5). Together with our Ca2+-imaging results, these findings indicate that upregulated TRPV1 under acute conditions in culture causes a lethal disruption in intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis – in effect, overburdening the cells with an influx of extracellular Ca2+. In the intact system, activation of TRPV1 by pressure-related stimuli increases its expression and boosts RGC activity, perhaps by enhancement of post-synaptic membrane potential.35 Our idea is consistent with TRPV1's role in neuronal responses to mechanical stimuli underlying pressure-induced pain, injury monitoring and visceral distension.52-61 The robust Ca2+ conductance associated with TRPV1 activation can also contribute to apoptosis, neurodegenerative disease, and synaptic remodeling.40,62-66 TRPV1 also couples to protective cascades. The endogenous cannabinoid anandamide is a ligand for TRPV1 and the cannabinoid type 1 (CB1) receptor and is known to protect against ischemic injury and excitotoxicity.67

In the normal retina, we find that TRPV1 co-localizes with TRPV4 in some RGCs and forms a protein complex retina, as in normal brain tissue (Figs. 6, 7). The antibodies we used against TRPV1 for our co-immuno-precipitation experiments recognize multiple subunit-specific epitopes. These include the full-length epitope of 100–113 kDa, a dimer near 200 kDa, and a smaller epitope below 75 kDa.20,23,68,69 Our western blot results are consistent with these previous studies. For TRPV4, the antibodies we used recognize slightly smaller subunit-specific intracellular epitopes of approximately 90–110 kDa70-72. Thus, it is not surprising that the co-immuno-precipitation product for TRPV1 and TRPV4 is slightly below 100 kDa. This product is absent when we re-run the western for TRPV1 following the precipitation reaction (Fig. 7C), suggesting a specific interaction in the full-length epitope.

In retinal mRNA from the DBA2J mouse model of chronic glaucoma, Trpv1 and Trpv4 expression were inversely related: even as Trpv1 increased with elevated ocular pressure (Fig. 7D), Trpv4 decreased (Fig. 7E). The meaning of this relationship is unclear, given that in normal retina TRPV1 and TRPV4 co-localize in some RGCs and form a reaction complex. In mouse magnocellular neurosecretory cells, both TRPV1 and TRPV4 contribute to spontaneous firing of action potentials, but only TRPV1 encodes dynamic changes in response to temperature fluctuations necessary for thermosensation.73 Similarly, for RGCs exposed to elevations in intraocular pressure, as in glaucoma, opposite changes in levels of TRPV1 and TRPV4 could reflect a need to encode quickly (or transiently) a greater range of excitation rates to accommodate the higher spontaneous level of action potentials we have observed.34,35 This could explain the rise in TRPV1 expression we see. That TRPV4 expression diminishes might be explained by its role in pressure and mechanosensation in many systems.74 In retina, TRPV4 elevates RGC Ca2+ in response to membrane stress, and so excessive activation could lead to Ca2+-dependent cell death,30 as with TRPV1 (Fig. 5).23 A reduction in TRPV4 expression over time could reflect desensitization of the channel as well and might serve to blunt the system's sensitivity to stress associated with elevated ocular pressure.

Methods

Animals and tissue

All animal procedures were approved by the Vanderbilt University Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. We obtained Trpv1-/- (B6.129 × 1-Trpv1tm1Jul/J) mice and their age-matched control C57BL/6 (C57) strain as well as adult DBA/2J (3–12 mo) and its age-matched transgenic control strain D2-Gpnmb+ (D2) from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). Animals were maintained in a 12-h light/dark cycle with standard rodent chow available ad libitum as described.44,75 Sections from adult macaque monkey and normal human (88 yrs, female) retina were prepared from paraffin blocks prepared for other purposes. Immuno-labeling was performed as described in previous studies using anti-TRPV1 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, for rat, monkey and human retinas, 1:1000; Neuromics, Edina, MN, for mouse, 1:100) and anti-TRPV4 (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel; 1:200).23,76,77,35 To label RGCs we used monoclonal antibodies against phosphorylated heavy-chain neurofilament (SMI31, Sternberger Monoclonal Inc., Baltimore, MD, 1:1000); for astrocytes, we used antibodies against glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP, Millipore, 1:500).

Purified retinal ganglion cell primary cultures and Ca2+ imaging

Primary cultures of purified RGCs from post-natal day 4–10 Sprague-Dawley rats were prepared using immune-magnetic separation and maintained either at ambient pressure in a standard incubator or at +70 mmHg hydrostatic pressure within the incubator as previously described.44,23

To assess TRPV1-mediated changes in accumulated intracellular Ca2+, we utilized the BAPTA-based Ca2+ indicator dye Fluo-4 AM (Molecular Probes, Eugene OR), following published protocols.78,79,23,35 Briefly, primary cultures were treated for one hour with either the TRPV1-specific agonist capsaicin (CAP, 1 μM), its vehicle (ETOH), or CAP with the TRPV1-specific antagonist iodo-resinferatoxin (IRTX, 10 nM). We chose this period of exposure for comparison with our previous Ca2+ accumulation experiments in which RGCs were exposed to hydrostatic pressure for one hour prior to imaging.23 As well, though Ca2+ levels can change rapidly in response to stimuli, we are interested in sustained changes in Ca2+ levels that could influence cell survival. Live cultures were cover-slipped with physiological saline and imaged using confocal microscopy. For each sample, 15–20 independent fields were acquired and Fluo-4 intensity quantified using Image Pro Plus (v.5.1.2; Media Cybernetics, San Diego, CA). Preparations were conducted in triplicate.

Retinal explants

For ex vivo retinal preparations, eyes were enucleated from adult C57 and TRPV1-/- mice and retinas rapidly removed and prepared as previously described.77 Briefly, explants were placed on organotypic culture inserts (0.4 mm pore; Millipore, Temecula, CA) held within culturing plates containing modified Neurobasal A media (2% B27 and 1% N2 supplements, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 μM inosine, 0.1% gentamicin, 50 ng/mL BDNF, 20 ng/mL CNTF, and 10 ng/mL bFGF), and allowed to equilibrate overnight in an incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2.Explants were maintained at ambient pressure in a standard incubator or at +70 mmHg hydrostatic pressure within the incubator, as previously described.44,23 All experiments using explants were performed minimally in triplicate.

The TRPV1-specific antagonist iodo-resiniferatoxin (I-RTX; Alexis Biochemicals, Lausen, Switzerland) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide(DMSO) as a vehicle and diluted with explant culture media to a concentration of 10 nM, which we have shown is protective of isolated RGCs exposed to pressure.23 Similarly, we used 950 μM ethyleneglycol-bis(B-aminoethyl)-N,N,N1,N1-tetraacetic acid (EGTA; Gibco) to reduce the concentration of available Ca2+ in the culture media from 1 mM to 100 μM, as determined by Max Chelator (Stanford University, Stanford, CA). This too we have shown prevents pressure-induced death of RGCs in culture.23 Following experimentation, explants were fixed overnight at 4°C in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Immuno-labeling of RGCs in retinal explants was performed with antibodies recognizing mouse anti-Brn3a (1:50; Chemicon80) and visualized with goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated with Alexa 594 dye (10 mg/ml; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). We assessed apoptosis of RGCs using a terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) assay with DAPI counterstain (50 mg/ml, Molecular Probes). RGC body density was determined by counting in multiple (≥ 10) random images the number of Brn3a+ RGCs per mm2. TUNEL+ apoptotic nuclei in the ganglion cell layer were quantified as a percent of all DAPI-stained cells.

Quantitative and conventional RT-PCR

For quantitative RT-PCR, following Weitlauf et al.,35 we extracted RNA from retina of naïve C57, DBA2J and D2 mouse eyes. Briefly, after incubation in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris/HCl, pH 8.0; 0.1 mM EDTA, pH8.0; 2% SDS, pH 7.3; and 500 μg/ml Proteinase K (Clontech Labs, Mountain View, CA), RNA was extracted using Trizol Invitrogen) with 10 μg of glycogen added as an RNA carrier prior to precipitation. RNA concentration and purity were determined using a NanoDrop 8000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). Samples (1 μg) were DNase-treated (Invitrogen) prior to cDNA synthesis (Applied Biosystems reagents, Foster City, CA), and quantitative was performed using an ABI PRISM 7300 Real-Time PCR System and a FAM dye-labeled gene-specific probe for Trpv1 (Applied Biosystems). Cycling conditions and cycle threshold values were automatically determined by the supplied ABI software (SDS v1.2). Relative product quantities for the Trpv1 transcript were performed in triplicate and determined using the 2ΔΔCt analysis method,81 with normalization to 18s rRNA as an endogenous control.

For conventional RT-PCR, total RNA was isolated from cultured RGCs using the Qiagen Micro-RNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA), according to manufacturer's instructions. RT-PCR was performed as previously described.27,44 Briefly, following first and second strand synthesis of cDNA, gene-specific PCR was conducted for 30 cycles with the following primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA): mouse actin (5′-TCC TGG GTA TGG AAT CCT GTG G-3′; 5′-CTT GAG TCA AAA GCG CCA AAA C-3′) and rat Trpv1 (5′-CAA GCA CTC GAG ATA GAC ATG CCA-3′; 5′ –ACA TCT CAA TTC CCA CAC ACC TCC-3′). Actin was used to confirm the presence of comparable cDNA concentrations between samples. To ensure that genomic DNA was not the source of PCR products, primers for both actin and Trpv1 were designed to span an intron. In addition, gene-specific PCR was performed on an aliquot of each sample that did not undergo reverse transcription. PCR products of 514 bp (actin) and 282 bp (Trpv1) were separated on an agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and digitally imaged on a gel reader (Alpha Innotech, San Leandro, CA). To evaluate contamination of RNA samples by genomic DNA, PCR was conducted on RNA samples from each culture.

Genotyping

Trpv1-/- (B6.129 × 1-Trpv1tm1Jul/J) mice were genotyped prior to experimentation to confirm the transgene, following protocols provided by Jackson Laboratories. DNA from small ear was extracted using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, MD) and concentration determined using a NanoDrop 8000 (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). Each PCR reaction contained the following: 2.5 μl 10× PCR Buffer (Invitrogen), 0.75 μl 50 mM MgCl2 (Invitrogen), 0.5 μl 10 mM dNTP mix (Promega, Madison, WI), 0.5 μl of each primer (10 μM working stocks; Integrated DNA Technologies), 0.1 μl Platinum Taq polymerase (Invitrogen), 40 ng of extracted template DNA, and the correct amount of DNase/RNAse free water to increase the total reaction volume to 25 μl. For detection of Trpv1 gene truncation in Trpv1-/- mice, 2 forward primers were used to produce wild-type (Jackson Laboratory, oIMR1561; 5′ CCT GCT CAA CAT GCT CT TG 3′) and Trpv1-/- (Jackson Laboratory, oIMR0297; 5′ CAC GAG ACT AGT GAG ACG TG 3′) gene products, both of which used a shared reverse primer (Jackson Laboratory, oIMR1562; 5′ TCC TCA TGC ACT TCA GGA AA 3′). With this primer combination, wild-type animals yield a product size of 984 bp and Trpv1-/- animals yield a product size of 600 bp. Positive control detection of Gapdh gene products used forward (5′ TTG GCA TTG TGG AAG GGC TC 3′) and reverse (5′ TGC TGT TGA AGT CGC AGG AGA C 3′) primers to detect a 363 bp product. Often a second round of PCR was necessary to obtain sufficient gene product to detect on an agarose gel using ethidium bromide labeling.

Western blots and co-immuno-precipitation

Brain and retina from adult Brown Norway rats were homogenized in ice-cold RIPA-Tris lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.1% SDS, .5% Na Deoxycholate, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.2 mM Na3VO4) and supplemented with the protease inhibitors, Proteinase IC and Phosphatase IC (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Lewes, UK). The tissue homogenate was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C and protein concentration of the supernatant determined by BCA Assay. For protein gel blots, proteins (40 μg per lane) were separated with SDS-PAGE using Bio-Rad 4–20% Mini Gels and Criterion 12% Tris-HCl gels. Protein was transferred onto PVDF membrane (Millipore Immobilon) and blotted overnight at 4°C using anti-TRPV1 (Novus, NB100–1617; 1:1000) or anti-TRPV4 (Santa Cruz, H-79 sc-98592). This TRPV1 antibody recognizes full-length TRPV1 in any glycosylation state (100 to 113 kDa), while that for TRPV4 recognizes a glycosylated form of the protein (97–107 kDa). The blots were incubated with secondary Alexa Fluor 680 goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) antibodies (Invitrogen, 1:5000) and detected by Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor).

To assess whether TRPV1 and TRPV4 form a heteromeric protein complex, we pre-incubated 250 μg of protein in 20 μl of A/G agarose beads for one hour to reduce nonspecific binding. After centrifuging at 11,000 rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C, the supernatant was removed, and pre-cleared protein was immuno-precipitated overnight at 4°C using 5 μg of either the anti-TRPV1 or anti-TRPV4 antibodies described above. Beads were collected and washed 5 times in 500 μl of RIPA-PBS washing buffer (1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 200 uM Na3VO4, PIC, pH adjusted to 7.2 wih 1N HCl). The bead pellet was resuspended in DTT loading buffer and denatured at 95°C for 10 min. Samples were centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 5 min, and supernatant was used for SDS-PAGE and Western blotting to detect either TRPV1 (Novus NB100–1617) or TRPV4 (Alomone, ACC-034, 1:200). The latter antibody is highly specific and directed against an intracellular epitope in the C-terminus of rat TRPV4 (90 kDa). Membrane was blocked with 3% non-fat milk in TBS-T (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) for one hour at room temperature and incubated with secondary antibody for one hour at room temperature.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization with immuno-labeling

We generated Trpv1 mRNA probes for mouse tissue as described in our published protocol, using RNA extracted from C57BL/6 mouse brain (Qiagen Inc.. USA, Valencia, CA) and first-strand cDNA synthesis using Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen)35,82 An antisense probe recognizingTrpv1 mRNA was made against a nucleotide sequence present in mouse Trpv1 (nucleotides 226 to 500 of [GenBank: NM_001001445]). We inserted a transcript generated by PCR using primers to Trpv1 (forward 5′-ATC ACC GTC AGC TCT GTT GTC ACT-3′ and reverse 5′-TGC AGA TTG AGC ATG GCT TTG AGC-3′) into pGEM-T Easy Vector (Promega, Madison, WI) and orientation verified by sequencing. Isolated plasmids were linearized and purified, and labeled Trpv1 RNA probes generated using SP6 and T7 RNA polymerases and Digoxigenin RNA Labeling Mix (Roche Applied Sciences; Indianapolis, IN). Immmuno-detection of labeled Trpv1 mRNA was performed using anti-DIG-Fab-POD conjugate (Roche) diluted 1:100 in blocking buffer (1% blocking reagent (Roche) in 0.1 M Tris (pH 7.5), 0.15 M NaCl) followed by detection using the TSA plus Fluorescein system (Perkin-Elmer; Boston, USA). Immmuno-labeling for RGCs in the same tissue was performed with antibodies to phosphorylated heavy chain neurofilament (1:1000, SMI31; Sternberger Monoclonal Inc., Baltimore, MD).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian J. Carlson, Wendi Lambert, and Kelsey Karas for their expert assistance.

Funding

Funding provided by the National Eye Institute (5R01EY017427; DJC), the Melza M. and Frank Theodore Barr Foundation through the Glaucoma Research Foundation, Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., and BrightFocus Foundation. Imaging supported through the Vanderbilt Vision Research Center (P30EY008126).

References

- 1. Corey DP. New TRP channels in hearing and mechanosensation. Neuron 2003; 39: 585-8; PMID:12925273; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00505-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moran MM, Xu H, Clapham DE. TRP ion channels in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2004; 14:362-9; PMID:15194117; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.conb.2004.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lin S-Y, Corey DP. TRP channels in mechanosensation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2005; 15:350-7; PMID:15922584; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.conb.2005.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O’Neil RG, Heller S. The mechanosensitive nature of TRPV channels. Pflugers Arch Eur J Physiol 2005; 451:193-203; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00424-005-1424-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ho KW, Ward NJ, Calkins DJ. TRPV1: a stress response protein in the central nervous system. Am J Neurodegener Dis 2012; 1:1-14; PMID:22737633 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang X, Huang J, McNaughton PA. NGF rapidly increases membrane expression of TRPV1 heat-gated ion channels. EMBO J 2005; 24:4211-23; PMID:16319926; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Biggs JE, Yates JM, Loescher AR, Clayton NM, Robinson PP, Boissonade FM. Effect of SB-750364, a specific TRPV1 receptor antagonist, on injury-induced ectopic discharge in the lingual nerve. Neurosci Lett 2008; 443:41-5; PMID:18634850; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.06.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schumacher MA, Eilers H. TRPV1 splice variants: structure and function. Front Biosci 2010; 15:872-82; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.2741/3651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goswami C, Rademacher N, Smalla KH, Kalscheuer V, Ropers HH, Gundelfinger ED, Hucho T. TRPV1 acts as a synaptic protein and regulates vesicle recycling. J Cell Sci 2010; 123:2045-57; PMID:20483957; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.065144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Straiker AJ, Maguire G, Mackie K, Lindsey J. Localization of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the human anterior eye and retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1999; 40(10):2442-8; PMID:10476817 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stamer WD, Golightly SF, Hosohata Y, Ryan EP, Porter AC, Varga E, Noecker RJ, Felder CC, Yamamura HI. Cannabinoid CB(1) receptor expression, activation and detection of endogenous ligand in trabecular meshwork and ciliary process tissues. Eur J Pharmacol 2001; 431(3):277-86; PMID:11730719; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01438-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lau J, Dang M, Hockmann K, Ball AK. Effects of acute delivery of endothelin-1 on retinal ganglion cell loss in the rat. Exp Eye Res 2006; 82:132-45; PMID:16045909; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.exer.2005.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Marinelli S, Di Marzo V, Berretta N, Matias I, Maccarrone M, Bernardi G, Mercuri NB. Presynaptic facilitation of glutamatergic synapses to dopaminergic neurons of the rat substantia nigra by endogenous stimulation of vanilloid receptors. J Neurosci 2003; 23:3136-44; PMID:12716921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Xing J, Li J. TRPV1 receptor mediates glutamatergic synaptic input to dorsolateral periaqueductal gray (dl-PAG) neurons. J Neurophysiol 2007; 97:503-11; PMID:17065246; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/jn.01023.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Medvedeva YV, Kim MS, Usachev YM. Mechanisms of prolonged presynaptic Ca2+ signaling and glutamate release induced by TRPV1 activation in rat sensory neurons. J Neurosci 2008; 28:5295-311; PMID:18480286; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4810-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jiang CY, Fujita T, Yue HY, Piao LH, Liu T, Nakatsuka T, Kumamoto E. Effect of resiniferatoxin on glutamatergic spontaneous excitatory synaptic transmission in substantia gelatinosa neurons of the adult rat spinal cord. Neurosci 2009; 164:1833-44; PMID:19778582; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Peters JH, McDougall SJ, Fawley JA, Smith SM, Andresen MC. Primary afferent activation of thermosensitive TRPV1 triggers asynchronous glutamate release at central neurons. Neuron 2010; 65:657-69; PMID:20223201; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Van Buren JJ, Bhat S, Rotello R, Pauza ME, Premkumar LS. Sensitization and translocation of TRPV1 by insulin and IGF-I. Mol Pain 2005;1:17; PMID:15857517; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1744-8069-1-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mohapatra DP, Nau C. Regulation of Ca2+-dependent desensitization in the vanilloid receptor TRPV1 by calcineurin and cAMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 2005; 280(14):13424-32; PMID:15691846; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M410917200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ho KW, Lambert WS, Calkins DJ. Activation of the TRPV1 cation channel contributes to stress-induced astrocyte migration. Glia 2014; 62: 1435-1415. PMID:24838827; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/glia.22691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burgoyne CF. A biomechanical paradigm for axonal insult within the optic nerve head in aging and glaucoma. Exp Eye Res 2011; 93:120-32; PMID:20849846; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.exer.2010.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Calkins DJ. Critical pathogenic events underlying progression of neurodegeneration in glaucoma. Prog Retin Eye Res 2012; 31:702-19; PMID:22871543; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2012.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sappington RM, Sidorova T, Long DJ, Calkins DJ. TRPV1: contribution to retinal ganglion cell apoptosis and increased intracellular Ca2+ with exposure to hydrostatic pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2009; 50(2): 717-28; PMID:18952924; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1167/iovs.08-2321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Crish SD, Calkins DJ. Neurodegeneration in glaucoma: progression and calcium-dependent intracellular mechanisms. J Neuroscience 2011; 176:1-11; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.12.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zimov S, Yazulla S. Localization of vanilloid receptor 1 (TRPV1/VR1)-like immunoreactivity in goldfish and zebrafish retinas: restriction to photoreceptor synaptic ribbons. J Neurocytol 2004; 33:441-452; PMID:15520529; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000046574.72380.e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nucci C, Gasperi V, Tartaglione R, Cerulli A, Terrinoni A, Bari M, De Simone C, Agro AF, Morrone LA, Corasaniti MT, et al. Involvement of the endocannabinoid system in retinal damage after high intraocular pressure-induced ischemia in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2007; 48:2997-3004; PMID:17591864; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1167/iovs.06-1355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sappington RM, Calkins DJ. Contribution of TRPV1 to microglia-derived IL-6 and NFkB translocation with elevated hydrostatic pressure. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2008; 49(7): 3004-17; PMID:18362111; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1167/iovs.07-1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Maione S, Cristino L, Migliozzi AL, Georgiou AL, Starowicz K, Salt TE, Di Marzo V. TRPV1 channels control synaptic plasticity in the developing superior colliculus. J Physiol 2009; 587:2521-35; PMID:19406878; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.171900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang X, Teng L, Li A, Ge J, Laties AM, Zhang X. TRPC6 channel protects retinal ganglion cells in a rat model of retinal ischemia/reperfusion-induced cell death. Invest Ophthalmol Visual Sci 2010; 51:5751-8; PMID:20554625; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1167/iovs.10-5451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ryskamp DA, Witkovsky P, Barabas P, Huang W, Koehler C, Akimov NP, Lee SH, Chauhan S, Xing W, Renteria RC, et al. The polymodal ion channel transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 modulates calcium flux, spiking rate, and apoptosis of mouse retinal ganglion cells. J Neurosci 2011; 31:7089-101; PMID:21562271; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0359-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leonelli M, Martins DO, Kihara AH, Britto LR. Ontogenetic expression of the vanilloid receptors TRPV1 and TRPV2 in the rat retina. Int J Dev Neurosci 2009; 27:709-18; PMID:19619635; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2009.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leonelli M, Martins DO, Britto LR. TRPV1 receptors are involved in protein nitration and Muller cell reaction in the acutely axotomized rat retina. Exp Eye Res 2010; 91:755-68; PMID:20826152; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.exer.2010.08.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leonelli M, Martins DO, Britto LR. Retinal cell death induced by TRPV1 activation involves NMDA signaling and upregulation of nitric oxide synthases. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2013; 33:379-92; PMID:23324998; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10571-012-9904-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ward NJ, Ho KW, Lambert WS, Weitlauf C, Calkins DJ. Absence of transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 accelerates stress-induced axonopathy in the optic projection. J Neurosci 2014; 34:3161-70; PMID:24573275; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4089-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Weitlauf C, Ward NJ, Lambert WS, Sidorova TN, Ho KW, Sappington RM, Calkins DJ. Short-term increases in transient receptor potential vanilloid-1 mediate stress-induced enhancment of neuronal excitation. J Neurosci 2014; 34(46): 15369-81; PMID:25392504; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3424-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lakshmi S, Joshi PG. Co-activation of P2Y2 receptor and TRPV channel by ATP: implications for ATP induced pain. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2005; 25:819-32; PMID:16133936; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10571-005-4936-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van der Stelt M, Trevisani M, Vellani V, De Petrocellis L, Schiano Moriello A, Campi B, McNaughton P, Geppetti P, Di Marzo V. Anandamide acts as an intracellular messenger amplifying Ca2+ influx via TRPV1 channels. EMBO J 2005; 24:3026-37; PMID:16107881; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. El Kouhen R, Surowy CS, Bianchi BR, Neelands TR, McDonald HA, Niforatos W, Gomtsyan A, Lee CH, Honore P, Sullivan JP, et al. A-425619 [1-isoquinolin-5-yl-3-(4-trifluoromethyl-benzyl)-urea], a novel and selective transient receptor potential type V1 receptor antagonist, blocks channel activation by vanilloids, heat, and acid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005; 314:400-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1124/jpet.105.084103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Toth A, Wang Y, Kedei N, Tran R, Pearce LV, Kang SU, Jin MK, Choi HK, Lee J, Blumberg PM. Different vanilloid agonists cause different patterns of calcium response in CHO cells heterologously expressing rat TRPV1. Life Sci 2005; 76:2921-32; PMID:15820503; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Reilly CA, Johansen ME, Lanza DL, Lee J, Lim JO, Yost GS. Calcium-dependent and independent mechanisms of capsaicin receptor (TRPV1)-mediated cytokine production and cell death in human bronchial epithelial cells. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2005; 19:266-75; PMID:16173059; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jbt.20084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rigoni M, Trevisani M, Gazzieri D, Nadaletto R, Tognetto M, Creminon C, Davis JB, Campi B, Amadesi S, Geppetti P, et al. Neurogenic responses mediated by vanilloid receptor-1 (TRPV1) are blocked by the high affinity antagonist, iodo-resiniferatoxin. Br J Pharmacol 2003; 138:977-85; PMID:12642400; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Caterina MJ, Leffler A, Malmberg AB, Martin WJ, Trafton J, Petersen-Zeitz KR, Koltzenburg M, Basbaum AI, Julius D. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science 2000; 288:306−313; PMID:10764638; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1126/science.288.5464.306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sappington RM, Chan M, Calkins DJ. Interleukin-6 protects retinal ganglion cells from pressure-induced death. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2006; 47:2932-42; PMID:16799036; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1167/iovs.05-1407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hellwig N, Albrecht N, Harteneck C, Schultz G, Schaefer M. Homo-and heteromeric assembly of TRPV channel subunits. J Cell Sci 2005; 118(Pt5): 917-28; PMID:15713749; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1242/jcs.01675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Minke B, Cooke B. TRP channel proteins and signal transduction. Physiol Rev 2002; 82:429-72; PMID:11917094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Cheng W, Yang F, Takanishi CL, Zheng J. Thermosensitive TRPV channel subunits coassemble into heteromeric channels with intermediate conductance and gating properties. J Gen Physiol 2007;129(3):191-207; PMID:17325193; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1085/jgp.200709731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ryskamp DA, Redmon S, Jo AO, Križaj D. TRPV1 and endocannabinoids: emerging molecular signals. Cells 2014; 3: 914-38; PMID:25222270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Vennekens R, Menigoz A, Nilius B. TRPs in the Brain. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 2012; 163:27-64; PMID:23184016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jonas JB, Budde WM. Diagnosis and pathogenesis of glaucomatous optic neuropathy: morphological aspects. Prog Retinal Eye Res 2000; 19:1-40; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S1350-9462(99)00002-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol 2006; 90:262-7; PMID:16488940; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/bjo.2005.081224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Mutai H, Heller S. Vertebrate and invertebrate TRPV-like mechanoreceptors. Cell Calcium 2003; 33:471-8; PMID:12765692; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0143-4160(03)00062-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hwang SJ, Burette A, Rustioni A, Valtschanoff JG. Vanilloid receptor VR1-positive primary afferents are glutamatergic and contact spinal neurons that co-express neurokinin receptor NK1 and glutamate receptors. J Neurocytol 2004; 33:321-9; PMID:15475687; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1023/B:NEUR.0000044193.31523.a1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rong W, Hillsley K, Davis JB, Hicks G, Winchester WJ, Grundy D. Jejunal afferent nerve sensitivity in wild-type and TRPV1 knockout mice. J Physiol 2004; 560:867-81; PMID:15331673; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.071746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Scotland RS, Chauhan S, Davis C, De Felipe C, Hunt S, Kabir J, Kotsonis P, Oh U, Ahluwalia A. Vanilloid receptor TRPV1, sensory C-fibers, and vascular autoregulation: a novel mechanism involved in myogenic constriction. Circ Res 2004; 95:1027-34; PMID:15499026; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1161/01.RES.0000148633.93110.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jones RC, 3rd, Xu L, Gebhart GF. The mechanosensitivity of mouse colon afferent fibers and their sensitization by inflammatory mediators require transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 and acid-sensing ion channel 3. J Neurosci 2005; 25:10981-9; PMID:16306411; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0703-05.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ma W, Zhang Y, Bantel C, Eisenach JC. Medium and large injurd dorsal root ganglion cells increase TRPV-1, accompanied by increased alpha2C-adrenoceptor co-expression and functional inhibition by clonidine. Pain 2005; 113(3): 386-94; PMID:15661448; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pain.2004.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Plant TD, Zollner C, Mousa SA, Oksche A. Endothelin-1 potentiates capsaicin-induced TRPV1 currents via the endothelin A receptor. Exp Biol Med 2006; 231:1161-4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Liedtke W. Transient receptor potential vanilloid channels functioning in transduction of osmotic stimuli. J Endocrinol 2006. 191:515-23; PMID:17170210; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1677/joe.1.07000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Daly D, Rong W, Chess-Williams R, Chapple C, Grundy D. Bladder afferent sensitivity in wild-type and TRPV1 knockout mice. J Physiol 2007; 583:663-74; PMID:17627983; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.139147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pingle SC, Matta JA, Ahern GP. Capsaicin receptor: TRPV1 a promiscuous TRP channel. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2007; 179:155-71; PMID:17217056; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/978-3-540-34891-7_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Agopyan N, Head J, Yu S, Simon SA. TRPV1 receptors mediate particulate matter-induced apoptosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004;286:L563-72; PMID:14633515; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajplung.00299.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Aarts MM, Tymianski M. TRPMs and neuronal cell death. Pflugers Arch Eur J Physiol 2005; 451:243-249; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00424-005-1439-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Miller BA. The role of TRP channels in oxidative stress-induced cell death. J Membrane Biol 2006; 209:31-41; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s00232-005-0839-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Kim SR, Kim SU, Oh U, Jin BK. Transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1 mediates microglial cell death in vivo and in vitro via Ca2+-mediated mitochondrial damage and cytochrome c release. J Immunol 2006; 177:4322-9; PMID:16982866; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hong S, Agresta L, Guo C, Wiley JW. The TRPV1 receptor is associated with preferential stress in large dorsal root ganglion neurons in early diabetic sensory neuropath. J Neurochem 2008; 105(4): 1212-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kim SR, Chung YC, Chung ES, Park KW, Won SY, Bok E, Park ES, Jin BK. Roles of transient receptor potential vanilloid subtype 1 and cannabinoid type 1 receptors in the brain: neuroprotection versus neurotoxicity. Mol Neurobiol 2007; 35(3): 245-54; PMID:17917113; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s12035-007-0030-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wang C, Hu HZ, Colton CK, Wood JD, Zhu MX. An alternative splicing product of the murine trpv1 gene dominant negatively modulates the activity of TRPV1 channels. J Biol Chem 2004;279:37423-30; PMID:15234965; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1074/jbc.M407205200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Stein AT, Ufret-Vincenty CA, Hua L, Santana LF, Gordon SE. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase binds to TRPV1 and mediates NGF-stimulated TRPV1 trafficking to the plasma membrane. J Gen Physiol 2006;128:509-22; PMID:17074976; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1085/jgp.200609576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tian W, Salanova M, Xu H, Lindsley JN, Oyama TT, Anderson S, Bachmann S, Cohen DM. Renal expression of osmotically responsive cation channel TRPV4 is restricted to water-impermeant nephron segments. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2004; 287: F17-24; PMID:15026302; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1152/ajprenal.00397.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Phan MN, Leddy HA, Votta BJ, Kumar S, Levy DS, Lipshutz DB, Lee SH, Liedtke W, Guilak F. Functional characterization of TRPV4 as an osmotically sensitive ion channel in porcine articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60(10):3028-37; PMID:19790068; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/art.24799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zaika O, Mamenko M, Berrout J, Boukelmoune N, O'Neil RG, Pochynyuk O. TRPV4 dysfunction promotes renal cystogenesis in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 24(4):604-16; PMID:23411787; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1681/ASN.2012050442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Sudbury JR, Bourque CW. Dynamic and permissive roles of TRPV1 and TRPV4 channels for thermosensation in mouse supraoptic magnocellular neurosecretory neurons. J Neurosci 2013; 33(43):17160-5; PMID:24155319; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1048-13.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Liedtke W. Molecular mechanisms of TRPV4-mediated neural signaling. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008; 1144:42-52; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1196/annals.1418.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Crish SD, Sappington RM, Inman DM, Horner PF, Calkins DJ. Distal axonopathy with structural persistence in glaucmatous neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107(11):5196-201; PMID:20194762; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.0913141107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Lambert WS, Ruiz L, Crish SD, Wheeler LA, Calkins DJ. Brimonidine prevents axonal and somatic degeneration of retinal ganglion cell neurons. Mol Neurodegener 2011; 6:4; PMID:21232114; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1186/1750-1326-6-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dapper JD, Crish SD, Pang IH, Calkins DJ. Proximal inhibition of p38 MAPK stress signaling prevents distal axonopathy. Neurobiology of disease 2013; 59C:26-37; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Gee KR, Brown KA, Chen WN, Bishop-Stewart J, Gray D, Johnson I. Chemical and physiological characterization of fluo-4 Ca(2+)-indicator dyes. Cell Calcium 2000; 27:97-106; PMID:10756976; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1054/ceca.1999.0095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Kreitzer AC, Gee KR, Archer EA, Regehr WG. Monitoring presynaptic calcium dynamics in projection fibers by in vivo loading of a novel calcium indicator. Neuron 2000; 27:25-32; PMID:10939328; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00006-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Xiang M, Zhou L, Macke JP, Yoshioka T, Hendry SH, Eddy RL, Shows TB, Nathans J. The Brn-3 family of POU-domain factors: primary structure, binding specificity, and expression in subsets of retinal ganglion cells and somatosensory neurons. J Neurosci 1995; 15:4762-685; PMID:7623109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001; 25:402-8; PMID:11846609; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Crish SD, Dapper JD, MacNamee SE, Balaram P, Sidorova TN, Lambert WS, Calkins DJ. Failure of axonal transport induces a spatially coincident increase in astrocyte BDNF prior to synapse loss in a central target. Neuroscience 2013; 229:55-70; PMID:23159315; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.10.069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]