Abstract

Flavodoxins in combination with the flavin mononucleotide (FMN) cofactor play important roles for electron transport in prokaryotes. Here, novel insights into the FMN-binding mechanism to flavodoxins-4 were obtained from the NMR structures of the apo-protein from Lactobacillus acidophilus (YP_193882.1) and comparison of its complex with FMN. Extensive reversible conformational changes were observed upon FMN binding and release. The NMR structure of the FMN complex is in agreement with the crystal structure (PDB ID: 3EDO) and exhibits the characteristic flavodoxin fold, with a central five-stranded parallel β–sheet and five α-helices forming an α/β-sandwich architecture. The structure differs from other flavoproteins in that helix α2 is oriented perpendicular to the β-sheet and covers the FMN-binding site. This helix reversibly unfolds upon removal of the FMN ligand, which represents a unique structural rearrangement among flavodoxins.

Keywords: protein–ligand interaction, protein folding, cofactor binding, flavin mononucleotide

Introduction

Flavodoxins are small electron transfer proteins which are found primarily in prokaryotes and function in combination with a non-covalently bound cofactor, flavin mononucleotide (FMN).1–3 Overall, the Pfam flavoprotein clan (CL0042) contains seven families,4 five of which have been structurally characterized in complex with FMN, and two in their apo-forms. The apo-flavodoxin structures have the same overall fold and secondary structures as the corresponding holo-proteins,5–8 but some conformational heterogeneity at the FMN binding site was attributed to partial unfolding.9 Mutational and binding studies with riboflavin (non-phosphorylated FMN) indicated that cofactor binding is initiated through an aromatic interaction between the isoalloxazine ring of FMN and the hydrophobic binding site of apo-flavodoxin.10

Here we present the NMR and crystal structures of flavodoxin-4 from Lactobacillus acidophilus (YP_193882.1) in complex with FMN, and the NMR structure of its apo-form. These are the first structural representatives of the flavodoxin-4 Pfam family4 (PF12682) that consists of more than 1133 members from 627 species, including 593 bacteria. Unexpectedly, NMR studies in solution revealed a major ligand-associated conformational rearrangement in this structural genomics target selected by the Joint Center of Structural Genomics (JCSG, www.jcsg.org), which seems to be unique to the flavodoxins-4 family, which is a subset of the Pfam flavoprotein clan (CL0042).4

Results and Discussion

NMR and crystal structures of the Flavodoxin-4–FMN complex

Flavodoxin-4 from Lactobacillus acidophilus (YP_193882.1) was isolated and purified as a complex with the FMN cofactor (see Materials and Methods). The NMR-Profile11 generated from a 2D [15N,1H]-HSQC spectrum contained a complete set of backbone amide group signals, which indicated that the protein solution was homogeneous and that all amino-acid residues were NMR-observable.

The NMR structure determination at 298K followed the J-UNIO protocol12 (for further details, see Materials and Methods). Nearly 87% of the backbone atoms were automatically assigned using APSY-NMR data13 as input for UNIO-MATCH,14 and complete polypeptide backbone chemical shift assignments were obtained after interactive validation and extension of these assignments. Automated assignment with UNIO-ATNOS-ASCAN15,16 then yielded 72% of the side-chain chemical shifts expected from the primary structure, which were then interactively validated and, where applicable, corrected to yield chemical shift assignments for 90% of the side chains. The input for the structure calculation obtained on the basis of these chemical shift assignments with UNIO-ATNOS-CANDID17 is listed in Table1, which also presents the statistics of the structure calculation. The resulting structure contains a five-stranded parallel β-sheet (β1: Thr6—Tyr10, β2: Glu32—Glu35, β3: Leu79—Pro85, β4: Glu108—Phe114, β5: Val136—Arg141) and five α-helices (α1: Thr17—Glu27, α2: Lys49—Ile58, α3: Lys96—Met102, α4: His120—Glu129, α5: Val146—Trp149), in an α/β sandwich architecture (Fig. 1). The NMR structure superimposes with the crystal structure (PDB ID: 3EDO; see Materials and Methods) with an RMSD of 1.60 Å, as calculated for the backbone Cα atoms of Lys4 to Ser150.

Table 1.

Determination of the NMR Structure of Flavodoxin-4 in Aqueous Solution Containing 20 mM Sodium Phosphate and 50 mM NaCl at pH 6.0: Input for the Structure Calculations of the Apo-protein (Apo) and the FMN Complex (Holo) and Characterization of the Bundles of 20 Energy-minimized CYANA Conformers Representing These Structures

| Quantity | Valuea | |

|---|---|---|

| Holo (298K) | Apo (308K) | |

| NOE upper distance limit | 2471 | 2392 |

| Intraresidual | 646 | 630 |

| Short range | 709 | 646 |

| Medium range | 455 | 399 |

| Long range | 661 | 717 |

| Dihedral angle constraints | 798 | 795 |

| Residual target function value (Å2) | 2.04±0.26 | 1.95±0.21 |

| Residual NOE violations | ||

| Number≥0.1 Å | 22±4 | 16±4 |

| Maximum (Å) | 0.14±0.4 | 0.13±0.01 |

| Residual dihedral angle violations | ||

| Number≥2.5° | 1±1 | 2±1 |

| Maximum (°) | 3.0±1.1 | 3.5±1.0 |

| RMSD from ideal geometry | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.012 | 0.012 |

| Bond angles (°) | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| AMBER energies [kcal mol−1] | ||

| Total | −5351± 155 | −4737±134 |

| van der Waals | −397±27 | −328±17 |

| Electrostatic | −6071±174 | −5723±132 |

| RMSD to the mean coordinates (Å)b | ||

| Backbone (5−150) | 0.66±0.09 | 1.67±0.48 |

| Heavy atoms (5−150) | 1.18±0.10 | 2.43±0.64 |

| Backbone (5−10,16−37,68−150) | 0.56±0.10 | 0.58±0.09 |

| Heavy atoms (5−10,16−37,68−150) | 1.11±0.17 | 1.05±0.14 |

| Ramachandran plot statistics (%)c | ||

| Most favored regions | 78.8 | 72.6 |

| Additional allowed regions | 20.8 | 26.3 |

| Generously allowed regions | 0.5 | 1.0 |

| Disallowed regions | 0.0 | 0.1 |

Except for the top six entries, which represent the input generated for the final cycle of structure calculation with UNIO-ATNOS/CANDID and CYANA 3.0, average values and standard deviations for the 20 energy-minimized conformers are given.

The numbers in parentheses indicate the residues for which the RMSD was calculated.

As determined by PROCHECK.18

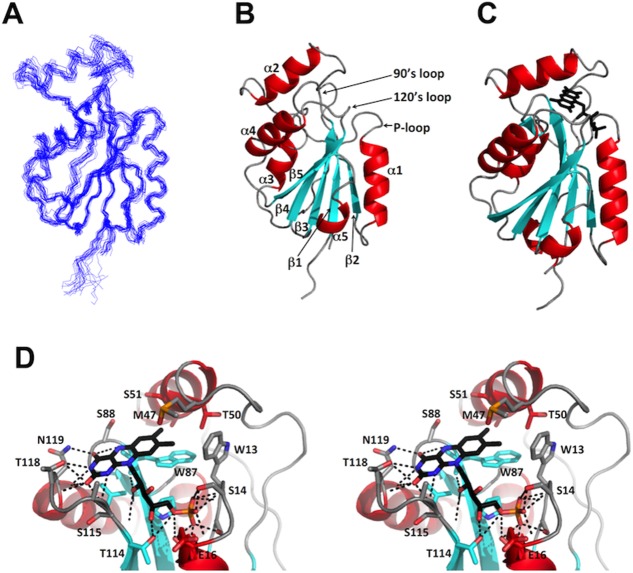

Figure 1.

NMR and crystal structures of Flavodoxin-4 in complex with FMN. (A) Ensemble of 20 energy-minimized CYANA conformers representing the NMR structure (PDB ID 2MWM). (B) Ribbon presentation of the NMR conformer closest to the mean coordinates of the bundle in (A), with identification of the three FMN binding loops. (C) Ribbon presentation of the crystal structure (PDB ID 3EDO). FMN is shown as a black stick diagram. In (B) and (C), the regular secondary structures were defined with DSSP.19(D) Close-up stereo view of the FMN binding site in the crystal structure in (C). Relative to the view in (C) the structure has been rotated by 60° about a vertical axis. Residues in contact with FMN are shown as stick diagrams and identified with the one-letter amino acid code and the sequence number. Dotted black lines indicate hydrogen bonds. The color code for regular secondary structures is used also for the carbon skeleton of the side chains, and oxygen and nitrogen atoms in the side chains and in FMN are colored red and blue, respectively.

The interface between the protein and the FMN cofactor in the crystal structure of the complex was analyzed using the PISA server.20 The FMN binding site consists of three functional loops, as was also observed in other flavodoxins: that is, the phosphate binding or P-loop between β1 and α1, the 90’s loop between β3 and α3, and the 120’s loop between β4 and α4 [Fig. 1(B)]. In contrast to other flavodoxin structures, helix α2 also interacts with FMN, with direct contacts with M47, T50, S51, and A54 [Fig. 1(D)]. The FMN phosphate group binds to the flavodoxin via hydrogen bonding to the P-loop. The hydroxyl groups of the isoalloxazine ring of FMN form hydrogen bonds with the 120’s loop, and the ribityl moiety hydrogen bonds with both the 90’s and 120’s loops. Finally, the indole ring of W87 in the 90’s loop is involved in aromatic interactions with the isoalloxazine ring of the FMN.

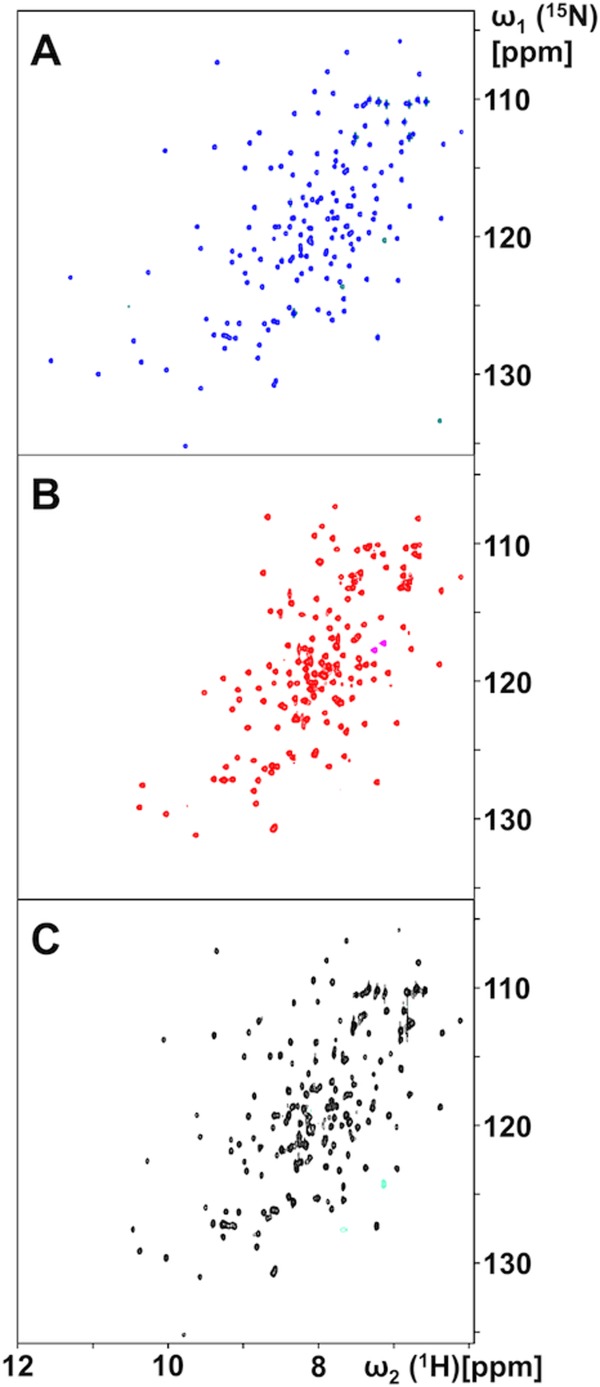

NMR structure of apo-Flavodoxin-4

The apo-form of Flavodoxin-4 was prepared by denaturing the purified protein–FMN complex with 6 mM GdHCl, run on a desalting column to obtain a colorless apo-protein solution, and refolding in NMR buffer. The 600 MHz 2D [15N,1H]-HSQC spectrum of the resulting solution at 298K contained an incomplete set of signals, with 21 backbone 15N–1H correlation peaks missing, and some of the observed cross peaks exhibited chemical shifts not seen in the flavodoxin-FMN complex [Fig. 2(A,B)]. Subsequent complexation of apo- Flavodoxin-4 with FMN showed that the ligand-dependent spectral changes are fully reversible [Fig. 2(A–C)], since, with the exception of three peaks at the low field end, the spectrum of the freshly prepared FMN complex [Fig. 2(A)] was recovered after addition of 1.1 equivalent of FMN to the solution of the apo-protein. In apo-protein solutions containing less than 1.0 equivalent of FMN, two sets of NMR signals were observed, corresponding respectively, to apo-Flavodoxin-4 and its FMN complex. This result corresponds with previous reports that FMN exchange between flavodoxin molecules is slow on the chemical shift timescale.6 The absence of 21 peaks in the spectrum of the apo-protein [Fig. 2(B)] can be rationalized by the assumption that the missing signals experience large chemical shift differences between two or multiple conformational states of the apo-protein, and that the absence of the expected 15N–1H correlation peaks is due to line broadening beyond detection due to exchange between these states.

Figure 2.

NMR spectral changes induced by FMN-binding to and release from Flavodoxin-4, as observed in 700 MHz 2D [15N,1H]-HSQC spectra at 298°C. (A) FMN complex obtained after initial protein expression and purification. (B) Apo-protein obtained after denaturation of the FMN-complex, FMN removal, purification and refolding (see text). (C) Protein–FMN complex obtained upon addition of 1.1 equivalents of FMN to a solution of the apo-protein.

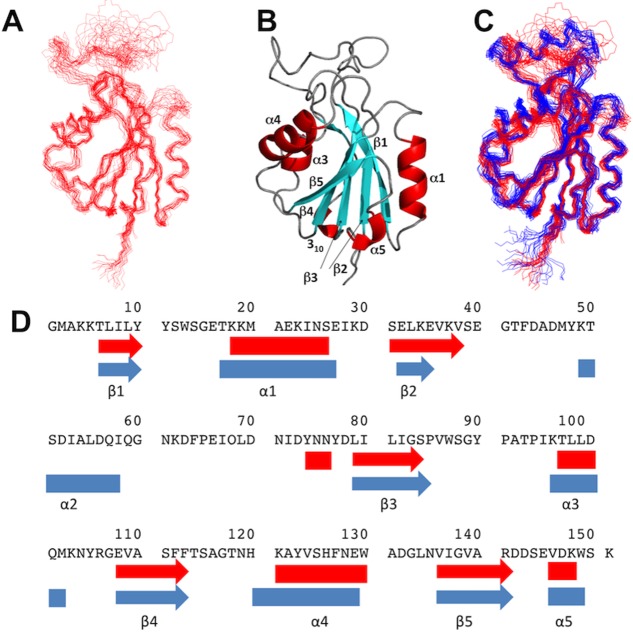

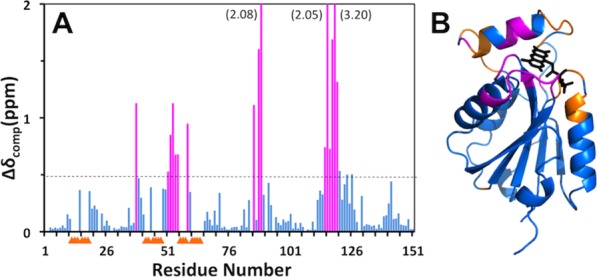

Improved, but still incomplete NMR-profiles11 of apo-Flavodoxin-4 were obtained at higher temperatures and the NMR structure of apo-Flavodoxin-4 was therefore determined at 308K, using the J-UNIO protocol (Table1).12 The apo-form of the protein contains most of the α/β sandwich architecture seen in the FMN complex. There are five β-strands (β1, Thr6—Tyr10; β2, Ser31—Val38; β3, Leu79—Ser84; β4, Glu108—Phe113; β5, Val136—Arg141), four α-helices (α1, Lys18—Ser26; α3, Thr97—Asp100; α4, Lys121—Trp130; α5, Val146—Lys148) and a 310 helix (Tyr74—Asn76) (Fig. 3). Superposition with the FMN-complex of Flavodoxin-4 shows near-identity for the protein core, with a backbone RMSD of 0.86 Å calculated for the superposition of residues 5–11, 17–36, 67–115, and 119–151. Large structural differences, which are also clearly manifested in the distribution of chemical shift changes and line-broadening effects along the amino-acid sequence (Fig. 4), are observed for the amino-acid segments 12–16, 37–66, and 116–118 that include helix α2 and other FMN binding elements in the structure of the flavodoxin-4-FMN complex (see above and Fig. 1). The conformational rearrangement involves the entire upper part of the structure in the orientation of Figure 3, and includes residues in direct contact with FMN as well as amino acids near the protein surface, which experience large conformational changes due to the unfolding of helix α2.

Figure 3.

NMR structure of apo-Flavodoxin-4 and comparison with its FMN complex. (A) Bundle of 20 energy-mimimized CYANA conformers representing the NMR structure. (B) Ribbon presentation of the conformer in (A) which is closest to the mean atom coordinates of the bundle. (C) Superposition of bundles of 20 NMR conformers of apo-Flavodoxin-4 (red) and its FMN-complex (blue). (D) Sequence positions of regular secondary structures in the NMR structures of apo-Flavodoxin-4 (red) and its FMN-complex (blue). Arrows indicate β-strands, and α-helices are shown as rectangles.

Figure 4.

Effect of FMN-binding on the backbone 15N−1H chemical shifts of Flavodoxin-4. (A) Plot along the amino-acid sequence of the combined chemical shift differences, Δδ=√{(ΔδH)2+(ΔδN/5)2}, between apo-Flavodoxin-4 and its FMN-complex. Residues with Δδ>0.5 ppm are highlighted in magenta. For the residues identified with yellow triangles, no data are available because the backbone amide signals in the 2D [15N,1H]-HSQC spectrum of the apo-protein at 298°C are broadened beyond detection (see text). (B) Ribbon diagram of the crystal structure of the Flavodoxin-4–FMN complex [3EDO; same as in Fig. 1(C)] color-coded to identify peptide segments showing either large chemical shift differences between the apo-protein and the FMN complex (magenta) or signal line-broadening beyond detection (yellow).

Conclusions

All five structurally characterized families of the seven families that form the flavoprotein clan exhibit an α/β sandwich architecture with a parallel five-stranded β-sheet (Fig. 1). Structure comparisons reveal that, within this common fold, the orientation of helix α2 is quite variable. In flavodoxin-4, it is part of the FMN binding site (Fig. 1), whereas in flavoprotein NrdI it is absent,19,21 and, in other structurally characterized families, it is located far away from the FMN binding site.5–8 It appears that a long insertion between helix α2 and strand β3 enables the unique orientation of helix α2 in members of the flavodoxin-4 family.

In previous studies of flavodoxins, the most significant conformational changes that were induced by ligand binding and release were at the FMN binding loops (Fig. 1), and no changes of regular secondary structures were reported.5–8 In the NMR structure of apo-Flavodoxin-4, we now observe that the polypeptide segment corresponding to helix α2 in the FMN complex is flexibly disordered. To the best of our knowledge, this is by far the largest FMN binding-induced structural rearrangement observed in a flavodoxin. The unique involvement of helix α2 in FMN-binding to Flavodoxin-4 and its different orientations in other members of the flavoprotein clan5–8 suggest that it has played an important role in the adaptation of flavodoxins to different physiological milieus.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression and purification

The LBA1001 gene (Uniprot ID: Q5FKC3, GenBank: YP_193882.1) was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from Lactobacillus acidophilus genomic DNA using PfuTurbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene) and I-PIPE (forward primer, 5′-ctgtacttccagggc ATGGCTAAAAAAACATTAATTTTAT-3′; reverse primer, 5′-aattaagtcgcgtta TTTACTCCATTTATCAACTTCACTATC-3′, target sequence in upper case) that included sequences for the predicted 5′ and 3′ ends. The expression vector, pSpeedET, which encodes an amino-terminal tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease-cleavable expression and purification tag (MGSDKIHHHHHHENLYFQ-G), was PCR amplified with V-PIPE (Vector) primers (forward primer: 5′-taacgcgacttaattaactcgtttaaacggtctccagc-3′, reverse primer: 5′-gccctggaagtacaggttttcgtgatgatgatgatgatg-3′). V-PIPE and I-PIPE PCR products were mixed, and the amplified DNA fragments were annealed. E. coli GeneHogs (Invitrogen) competent cells were transformed with the I-PIPE/V-PIPE mixture and dispensed on selective LB-agar plates. The cloning junctions were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Expression was performed in E. Coli BL21(DE3) cells (EMD Biosciences). Uniformly 13C,15N-labeled protein was prepared in kanamycin-containing M9 minimal medium, using 15NH4Cl and [13C6]-D-glucose as the sole nitrogen and carbon sources. The cells were grown at 37°C with vigorous shaking to an OD600nm of 0.6. The temperature was then reduced to 18°C, and protein expression was induced by 1 mM isopropyl β-d−1-thiogalactopyranoside for 20 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 g at 4°C for 5 min and re-suspended in buffer A (20 mM sodium phosphate at pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole) supplemented with Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche). The cells were lysed by sonication, insoluble debris was separated by centrifugation (20,000g at 4°C for 30 min), and the supernatant was filtered using 0.22 µm syringe filters. The protein was bound to a HisTrap HP Ni2+ affinity column (GE Healthcare) and eluted using a stepwise gradient from 50 to 500 mM imidazole. TEV protease was added to the fractions containing the target protein, which were incubated at room temperature overnight to remove the polyhistidine-tag. Imidazole was removed by loading the solution onto a HiPrep 26/10 desalting column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer A. The desalted solution was applied to another Ni2+ affinity column to collect the tag-free protein, which was then loaded onto a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with NMR buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate at pH 6.0, 50 mM NaCl). The fractions containing Flavodoxin-4 were concentrated to 1.2 mM, using a 3 kDa cutoff Amicon Ultra-15 centrifugal filter device (Millipore). The resulting intensively yellow solution was supplemented with 5% D2O (vol/vol) and 4.5 mM sodium azide for use as the NMR sample.

The apo-form of Flavodoxin-4 was obtained by denaturing 500 μL of a 1.4 mM solution of its FMN complex in 2 mL of denaturing buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate at pH 6.0, 50 mM NaCl, 6 mM GdHCl) and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The solution was loaded onto a HiPrep 26/10 desalting column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with denaturing buffer to obtain the apo-protein in a colorless solution. The protein-containing fractions were concentrated to 0.5 mL and refolded by adding them at 4°C with constant stirring at a rate of 34 μL h−1 to 50 mL of NMR buffer. The resulting solution was concentrated and then purified using a HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 75 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with NMR buffer. The NMR sample was prepared by addition of 5% D2O (v/v) and 4.5 mM sodium azide.

NMR spectroscopy and NMR structure calculation

“NMR-profiles”11 were prepared from 2D-[15N,1H]-HSQC spectra recorded on a Bruker Avance 700 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 1.7 mM TXI z-gradient microcoil probe. For each structure determination, three APSY experiments, 4D APSY-HACANH, 5D APSY-HACACONH and 5D APSY-CBCACONH, were recorded on a Bruker Avance 600 spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm CP2 QCI-F z-gradient cryogenic probehead, and 3D 15N-resolved, 3D 13Cali-resolved and 3D 13Caro-resolved [1H,1H]-NOESY spectra were recorded with a mixing time τm=65 ms on a Bruker Avance 800 MHz spectrometer equipped with a 5 mM TXI probe.

The J-UNIO protocol12 was used for automated chemical shift assignment and structure calculation. The APSY data were used as input for UNIO-MATCH.14 The results from UNIO-MATCH were validated and extended with the help of the 3D 15N-resolved and 3D 13Cali-resolved [1H,1H]-NOESY spectra. Automatic side-chain resonance assignments were carried out with the software UNIO-ATNOS/ASCAN,15,16 and the results were interactively checked and extended. The structure calculation was done with the UNIO-ATNOS/CANDID16,17 software for automated NOE assignment, and the torsion angle molecular dynamics program CYANA.22 The structures were energy minimized with the software OPALp23,24 and validated using in-house JCSG NMR Core criteria.12 The structure calculation statistics are summarized in Table1.

Titration of the apo-protein with FMN was performed by stepwise addition of FMN to the protein solution, and the complex formation was monitored by 2D [15N,1H]- HSQC experiments collected on a Bruker Avance 700-MHz NMR spectrometer equipped with a 1.7 mm micro-coil probe.

Crystal data collection, structure determination, and refinement

Initial screening for diffraction was carried out using the Stanford Automated Mounting system (SAM)25 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL, Menlo Park, CA). X-ray diffraction data were collected at the SSRL beamline 11-1 and indexed in the orthorhombic P212121 space group. A dataset corresponding to the peak wavelength of a selenium single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD) experiment was collected using a MarMosaic 325 CCD detector from a cryo-cooled crystal at 100 K. Data were integrated and scaled using XDS26 and XSCALE,26 respectively. The selenium substructure was solved with SHELXD,27 and the MAD phases were refined with autoSHARP.28 Iterative automated model building was performed with ARP/wARP from density-modified electron density. Model completion was performed throughout the procedure, using the interactive computer-graphics program COOT.29 The refinements with REFMAC30 were restrained against the SAD phases. X-ray data collection and refinement statistics are shown in Table2.

Table 2.

X-ray Data Collection and Refinement Statistics of the Flavodoxin-4–FMN Complex: (PDB ID 3EDO)

| Data collection | |

| Beamline | SSRL 11-1 |

| Space group | P212121 |

| Unit cell (Å) | a=44.56 b=52.03 c=156.75 |

| Dataset | λ1SAD |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97910 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 29.42–1.20 |

| No. observations | 434,233 |

| No. unique reflections | 114,258 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.4 (96.0) |

| Mean I/σ (I) | 10.5 (2.5) |

| Rmerge on I (%)a | 9.3 (58.2) |

| Rmeas on I (%)b | 10.9 (70.5) |

| Rpim on I (%)c | 5.5 (39.1) |

| Highest resolution shell | 1.23–1.20 |

| Model and refinement statistics | |

| Dataset used in refinement | λ1SAD |

| No. reflections (total)d | 114,155 |

| No. reflections (test) | 5,724 |

| Cutoff criteria | |F|>0 |

| Rcryst (%)e | 13.6 |

| Rfree (%)e | 16.0 |

| Stereochemical parameters | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.012 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.42 |

| MolProbity clash score | 2.3 |

| Ramachandran plot (%)f | 98.8 (0) |

| Rotamer outliers (%) | 0.72 |

| Average isotropic B-value (Å2)g | 15.8/9.8 |

| Wilson B-value (Å2) | 10.3 |

| ESU based on Rfree (Å)h | 0.034 |

| No. protein residues/chains | 300/2 |

| No. water molecules | 616 |

| Ligandsi | 2 FMN, 8 EDO |

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

Rmerge=ΣhklΣi|Ii(hkl)−(I(hkl))|/Σhkl Σi(hkl).

Rmeas=Σhkl[N/(N-1)]1/2Σi|Ii(hkl)−(I(hkl))|/ΣhklΣiIi(hkl).31

Typically, the number of unique reflections used in refinement is slightly less than the total number that were integrated and scaled. Reflections are excluded owing to negative intensities and rounding errors in the resolution limits and unit-cell parameters.

Rcryst=ΣhklǁFobs|−|Fcalcǁ/Σhkl|Fobs|, where Fcalc and Fobs are the calculated and observed structure-factor amplitudes, respectively. Rfree is the same as Rcryst but for 5.0% of the total reflections chosen at random and omitted from refinement.

Percentage of residues in favored regions of Ramachandran plot (No. outliers in parenthesis).

Values correspond to Flavodoxin-4/FMN.

Estimated overall coordinate error.34

FMN (flavin mononucleotide), EDO (1,2-ethanediol).

Crystal structure validation

The quality of the crystal structures was analyzed using the JCSG Quality Control server (see http://smb.slac.stanford.edu/jcsg/QC/). This server verifies: the stereochemical quality of the model, using AutoDepInputTool,35 MolProbity.36 and WHATIF 5.037; agreement between the atomic model and the X-ray data using SFcheck 4.038 and RESOLVE39; the protein sequence using CLUSTALW40; atom occupancies using MOLEMAN2.0.41 It also checks consistency of NCS pairs, evaluates differences in Rcryst/Rfree, expected Rfree/Rcryst, and maximum/minimum B-values by parsing the refinement log-file and header of the coordinate file. Protein quaternary structure analysis was performed using the EBI PISA server.20 The rendering of the structures was carried out with PyMOL (Schrödinger LLC) and CCP4mg.42

Data bank depositions

The NMR and crystal structures of the Lactobacillus acidophilus Flavodoxin-4–FMN complex have been deposited in the PDB under the accession codes 2MWM and 3EDO, respectively, and the NMR structure of the apo-protein with accession code 2N1M. NMR data of apo-Flavodoxin-4 and its FMN complex have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Bank with accession codes 25567 and 25342, respectively.

Acknowledgments

Kurt Wüthrich is the Cecil H. and Ida M. Green Professor of Structural Biology at The Scripps Research Institute. The authors thank all members of the JCSG for their contribution to the development and operation of our HTP structural biology pipeline and for bioinformatics analyses, protein production and structure determination. Genomic DNA from Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM was obtained from Rhodia Food (Cranbury, N.J.) distributed under the Florafit brand name. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS or NIH.

Glossary

- APSY

automated projection spectroscopy

- ASCAN

software for automated side-chain resonance assignment

- ATNOS

software for automated NMR peak picking

- CANDID

software for automated NOE assignment

- CYANA

software used for NMR structure calculation

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- FMN

flavin mononucleotide

- HSQC

heteronuclear single quantum coherence spectroscopy

- JCSG

Joint Center for Structural Genomics

- MATCH

software used for backbone chemical shift assignments

- NOE

nuclear Overhauser effect

- NOESY

nuclear overhauser effect spectroscopy

- PDB

protein data bank

- RMSD

root-mean-square deviation

- TEV

tobacco etch virus.

References

- Sancho J. Flavodoxins: sequence, folding, binding, function and beyond. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:855–864. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5514-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight E, Jr, Hardy RW. Flavodoxin. Chemical and biological properties. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:1370–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman SK, Reid GA. Flavoprotein protocols. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Finn RD, Bateman A, Clements J, Coggill P, Eberhardt RY, Eddy SR, Heger A, Hetherington K, Holm L, Mistry J, Sonnhammer EL, Tate J, Punta M. Pfam: the protein families database. Nucl Acids Res. 2014;42:D222–230. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genzor CG, Perales-Alcon A, Sancho J, Romero A. Closure of a tyrosine/tryptophan aromatic gate leads to a compact fold in apo flavodoxin. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:329–332. doi: 10.1038/nsb0496-329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Li Y, Zhang X, Guo X, Xia B, Jin C. Solution structures and backbone dynamics of a flavodoxin MioC from Escherichia coli in both Apo- and Holo-forms: implications for cofactor binding and electron transfer. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:35454–35466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Julvez M, Cremades N, Bueno M, Perez-Dorado I, Maya C, Cuesta-Lopez S, Prada D, Falo F, Hermoso JA, Sancho J. Common conformational changes in flavodoxins induced by FMN and anion binding: the structure of Helicobacter pylori apoflavodoxin. Proteins. 2007;69:581–594. doi: 10.1002/prot.21410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Q, Hu Y, Jin C. Conformational dynamics of Escherichia coli flavodoxins in apo- and holo-states by solution NMR spectroscopy. PloS One. 2014;9:e103936. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lostao A, Daoudi F, Irun MP, Ramon A, Fernandez-Cabrera C, Romero A, Sancho J. How FMN binds to anabaena apoflavodoxin: a hydrophobic encounter at an open binding site. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24053–24061. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301049200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayuso-Tejedor S, Abian O, Velazquez-Campoy A, Sancho J. Mechanism of FMN binding to the apoflavodoxin from Helicobacter pylori. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8703–8711. doi: 10.1021/bi201025y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrini B, Serrano P, Mohanty B, Geralt M, Wüthrich K. NMR-profiles of protein solutions. Biopolymers. 2013;99:825–831. doi: 10.1002/bip.22348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano P, Pedrini B, Mohanty B, Geralt M, Herrmann T, Wüthrich K. The J-UNIO protocol for automated protein structure determination by NMR in solution. J Biomol NMR. 2012;53:341–354. doi: 10.1007/s10858-012-9645-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta SK, Serrano P, Proudfoot A, Geralt M, Pedrini B, Herrmann T, Wüthrich K. APSY-NMR for protein backbone assignment in high-throughput structural biology. J Biomol NMR. 2015;61:47–53. doi: 10.1007/s10858-014-9881-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk J, Herrmann T, Wüthrich K. Automated sequence-specific protein NMR assignment using the memetic algorithm MATCH. J Biomol NMR. 2008;41:127–138. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9243-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorito F, Herrmann T, Damberger FF, Wüthrich K. Automated amino acid side-chain NMR assignment of proteins using 13C- and 15N-resolved 3D [1H, 1H]-NOESY. J Biomol NMR. 2008;42:23–33. doi: 10.1007/s10858-008-9259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann T, Güntert P, Wüthrich K. Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE-identification in the NOESY spectra using the new software ATNOS. J Biomol NMR. 2002;24:171–189. doi: 10.1023/a:1021614115432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann T, Güntert P, Wüthrich K. Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE assignment using the new software CANDID and the torsion angle dynamics algorithm DYANA. J Mol Biol. 2002;319:209–227. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson R, Torrents E, Lundin D, Sprenger J, Sahlin M, Sjöberg B, Logan D. High-resolution crystal structures of the flavoprotein NrdI in oxidized and reduced states—an unusual flavodoxin. Structural biology. FEBS J. 2010;277:4265–4277. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Güntert P, Mumenthaler C, Wüthrich K. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program DYANA. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:283–298. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koradi R, Billeter M, Güntert P. Point-centered domain decomposition for parallel molecular dynamics simulation. Comp Phys Comm. 2000;124:139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Luginbühl P, Güntert P, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. The new program OPAL for molecular dynamics simulations and energy refinements of biological macromolecules. J Biomol NMR. 1996;8:136–146. doi: 10.1007/BF00211160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AEE, Miller PJ, Deacon MD, Phizackerley AMRP. An automated system to mount cryo-cooled protein crystals on a synchrotron beamline, using compact sample cassettes and a small-scale robot. J Appl Crystallogr. 2002;35:720–726. doi: 10.1107/s0021889802016709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. XDS. Acta Cryst D. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider T, Sheldrick G. Substructure solution with SHELXD. Acta Cryst D. 2002;58:1772–1779. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vonrhein C, Blanc E, Roversi P, Bricogne G. Automated structure solution with autoSHARP. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;364:215–230. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-266-1:215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Skubak P, Lebedev AA, Pannu NS, Steiner RA, Nicholls RA, Winn MD, Long F, Vagin AA. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Cryst D. 2011;67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederichs K, Karplus PA. Improved R-factors for diffraction data analysis in macromolecular crystallography. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:269–275. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss MS, Hilgenfeld R. On the use of the merging R factor as a quality indicator for X-ray data. J Appl Crystallogr. 1997;30:203–205. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss MS, Metzner HJ, Hilgenfeld R. Two non-proline cis peptide bonds may be important for factor XIII function. FEBS Lett. 1998;423:291–296. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshank DW. Remarks about protein structure precision. Acta Cryst. 1999;D55:583–601. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998012645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Guranovic V, Dutta S, Feng Z, Berman HM, Westbrook JD. Automated and accurate deposition of structures solved by X-ray diffraction to the Protein Data Bank. Acta Cryst D. 2004;60:1833–1839. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen VB, Arendall WB, III, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Cryst D. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriend G. WHAT IF: a molecular modeling and drug design program. Mol Graph. 1990;8(29):52–56. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(90)80070-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaguine AA, Richelle J, Wodak SJ. SFCHECK: a unified set of procedures for evaluating the quality of macromolecular structure-factor data and their agreement with the atomic model. Acta Cryst D. 1999;55:191–205. doi: 10.1107/S0907444998006684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger T. SOLVE and RESOLVE: automated structure solution, density modification and model building. J Synchrot Rad. 2004;11:49–52. doi: 10.1107/s0909049503023938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG, Thompson JD. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucl Acid Res. 2003;31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt GJ. Validation of protein models from Calpha coordinates alone. J Mol Biol. 1997;273:371–376. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNicholas S, Potterton E, Wilson KS, Noble ME. Presenting your structures: the CCP4mg molecular-graphics software. Acta Cryst D. 2011;67:386–394. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911007281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]