Abstract

N,N’-diacetylbacillosamine is a novel sugar that plays a key role in bacterial glycosylation. Three enzymes are required for its biosynthesis in Campylobacter jejuni starting from UDP-GlcNAc. The focus of this investigation, PglE, catalyzes the second step in the pathway. It is a PLP-dependent aminotransferase that converts UDP-2-acetamido-4-keto-2,4,6-trideoxy-d-glucose to UDP-2-acetamido-4-amino-2,4,6-trideoxy-d-glucose. For this investigation, the structure of PglE in complex with an external aldimine was determined to a nominal resolution of 2.0 Å. A comparison of its structure with those of other sugar aminotransferases reveals a remarkable difference in the manner by which PglE accommodates its nucleotide-linked sugar substrate.

Keywords: aminotransferase; N,N’-diacetylbacillosamine; N-glycosylation; bacterial glycoproteins; pyridoxal 5’-phosphate

Introduction

Bacillosamine is the d-gluco member of the 2,4,6-trideoxy-2,4-diamino-hexose family of bacterial saccharides.1 In its di-N-acetyl form, also known as QuiNAc4NAc, it is a key component of the N- and O-linked protein glycosylation pathways in Campylobacter jejuni and other bacteria.2,3 It is also a precursor to legionaminic acid, a nonulosonic acid analog of sialic acid, which occurs as an O-linked sugar on C. jejuni flagella4 and forms the O-antigen of Legionella pneumophila.5

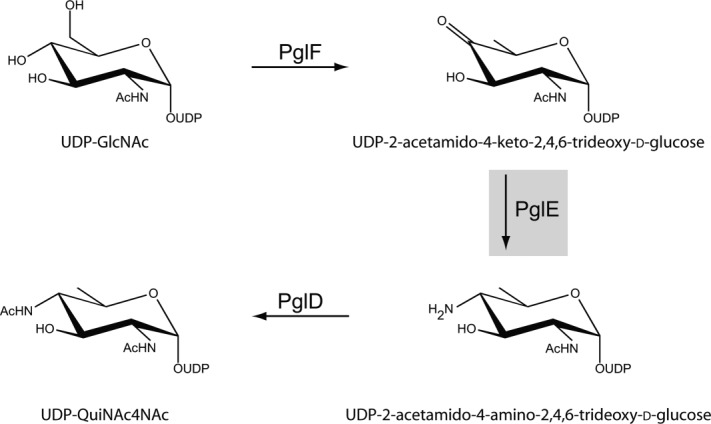

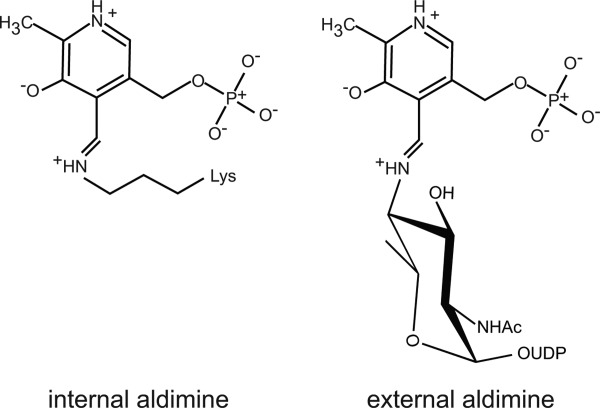

The biosynthetic pathway for the production of UDP-QuiNAc4NAc from UDP-GlcNAc in C. jejuni is shown in Scheme 1. The keto sugar product formed by the dehydratase PglF is aminated by the PLP-dependent enzyme PglE.6 On the basis of a preliminary X-ray analysis, PglE is known to belong to the aspartate aminotransferase superfamily.7 In the resting state of the sugar aminotransferases, the PLP cofactor is attached to the ε-amino group of a conserved lysine residue. This is referred to as the internal aldimine (Scheme 2). An amino group from a glutamate donor then forms PMP, which through a complex series of intermediates leads to an external aldimine as shown in Scheme 2.8 In the final step, the amino sugar product is displaced from the external aldimine by reaction of the ε-nitrogen of the conserved lysine.

Figure 1. Scheme.

Biosynthetic pathway for UDP-QuiNAc4NAc production.

Figure 2. Scheme.

Internal and external aldimines.

Within recent years the three-dimensional structures of various sugar aminotransferases have been reported. Of particular importance for the study presented here are the X-ray models of PseC from Helicobacter pylori,8 DesI from Streptomyces venezuelae,9 and ArnB from Salmonella typhimurium.10,11 These enzymes, which catalyze the reactions displayed in Scheme 3, are involved in the production of pseudaminic acid, desosamine, and 4-amino-4-deoxy-l-arabinose (Ara4N), respectively. Pseudaminic acid, and its derivatives, are required for the proper assembly of the flagellins in H. pylori and C. jejuni.4 Desosamine, an unusual 3-dimethylamino-3,4,6-trideoxhexose found attached to such clinically important antibiotics as erythromycin and azithromycin, is important for drug efficacy.12 Finally, Ara4N is observed on the lipid A moieties of some Gram negative bacteria where it plays a role in resistance to antimicrobial peptides such as polymyxin B.13

Figure 3. Scheme.

Representative reactions catalyzed by sugar aminotransferases.

Here we describe the three-dimensional architecture of the external aldimine form of PglE determined to 2.0-Å resolution. A comparison of the PglE, PseC, DesI, and ArnB models reveals a remarkable difference in the manner by which PglE accommodates its nucleotide-linked sugar substrate.

Results and Discussion

Overall structure of PglE

In most aminotransferases, the PLP cofactor typically forms a Schiff base with the ε-amino group of an active-site lysine, the internal aldimine (Scheme 2).14 This residue, in PglE, is Lys 184. To produce X-ray diffraction quality crystals of PglE, the site-directed mutant variant, K184A, was constructed, purified, and crystallized in the presence of PLP and the UDP-sugar product, which led to the formation of the external aldimine. Crystals of this complex belonged to the P41212 space group with the PglE dimer packing along a crystallographic twofold rotational axis. The structure was solved to 2.0-Å resolution, and the model was refined to an Roverall of 19.1% (Table1).

Table 1.

X-ray Data Collection Statistics and Model Refinement Statistics

| External aldimine complex | |

|---|---|

| Resolution limits (Å) | 30.0-2.0 (2.1–2.0)a |

| Number of independent reflections | 26,017 (3396) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (97.4) |

| Redundancy | 13.6 (6.1) |

| avg I/avg σ(I) | 15.1 (2.8) |

| Rsym (%)b | 5.3 (23.7) |

| R-factor (overall)%/no. reflectionsc | 19.1/26017 |

| R-factor (working)%/no. reflections | 18.8/24687 |

| R-factor (free)%/no. reflections | 25.4/1330 |

| Number of protein atoms | 3088 |

| Number of heteroatoms | 328 |

| Average B values | |

| Protein atoms (Å2) | 24.9 |

| Ligand (Å2) | 18.7 |

| Solvent (Å2) | 29.8 |

| Weighted RMS deviations from ideality | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.014 |

| Bond angles (º) | 1.7 |

| Planar groups (Å) | 0.008 |

| Ramachandran regions (%)d | |

| Most favored | 88.9 |

| Additionally allowed | 10.8 |

| Generously allowed | 0.3 |

Statistics for the highest resolution bin.

Rsym=(∑|I− |/∑ I) × 100.

|/∑ I) × 100.

R-factor=(Σ|Fo−Fc|/Σ|Fo|) × 100 where Fo is the observed structure-factor amplitude and Fc. is the calculated structure-factor amplitude.

Distribution of Ramachandran angles according to PROCHECK.15

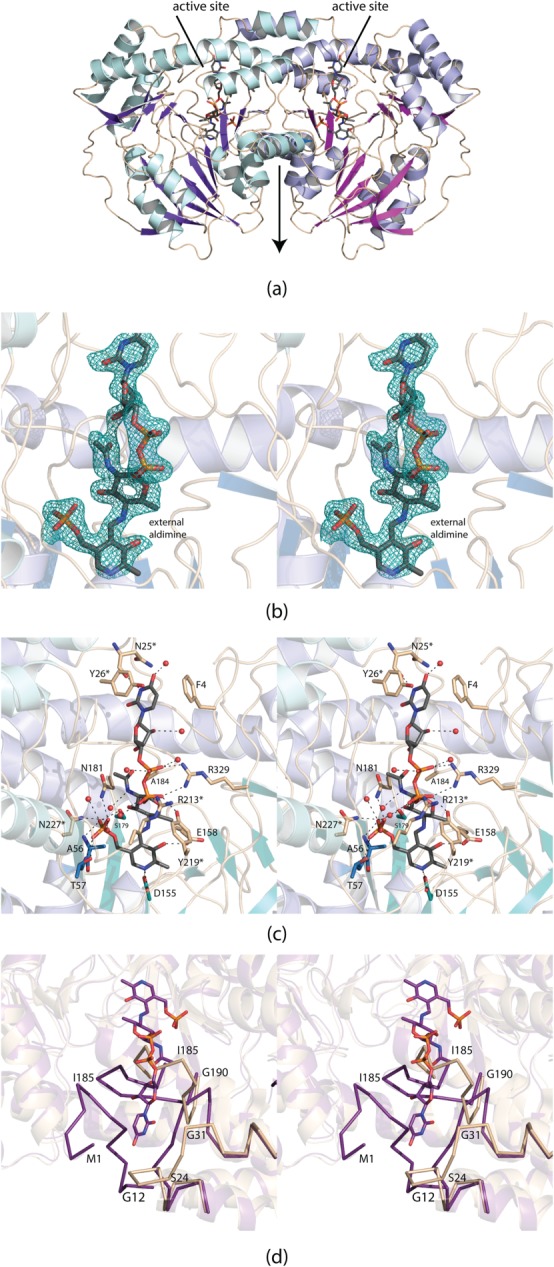

Shown in Figure 4 is a ribbon representation of the model. The dimer has dimensions of ∼80 Å × 80 Å × 65 Å and a total buried surface area of 5400 Å2. The active sites are separated by ∼30 Å. Each subunit contains 14 β-strands and 11 α-helices with the overall fold being dominated by a nine-stranded mixed β-sheet. The active sites of the dimer are wedged between the two subunits. PseC, ArnB, and DesI all contain a cis peptide that resides near the active site (Tyr 316, Phe 330, and Phe 330, respectively). In PglE, the corresponding residue is Trp 332, which adopts a trans peptide bond.

Figure 4. Figure.

Structure of the external aldimine form of PglE. Shown in (a) is a ribbon representation of the PglE dimer. The local twofold rotational axis lies in the plane of the page as indicated by the arrow. Displayed in (b) is the observed electron density for the external aldimine before it was included in the model. The map, contoured at 3σ, was calculated with coefficients of the form Fo−Fc, where Fo was the native structure factor amplitude and Fc was the calculated structure factor amplitude. A close-up view of the active site is presented in (c). Those amino acids highlighted in wheat reside on loops whereas those depicted in blue are located on either β-strands or α-helices. An asterisk next to the amino acid label indicates that the residue is located on the second subunit of the dimer. Ordered water molecules are represented as red spheres. Potential hydrogen bonding interactions within 3.2 Å are indicated by the dashed lines. A superposition of the region surrounding the external aldimine in the PglE complex reported here versus the free enzyme (PDB entry 1O61) is shown in (d). The ribbon displayed in wheat corresponds to the original 1O61 coordinates, whereas the ribbon colored in purple represents the observed loops in the external aldimine form. All figures were prepared using PyMOL.16

Electron density corresponding to the observed external aldimine is displayed in Figure 4(b). The ligand is well ordered with an average B-factor of 18.7 Å2. The pyranosyl moiety of the ligand adopts the 4C1 conformation. A close-up view of the active site is presented in Figure 4(c). Most of the side chains involved in ligand binding reside on loops. Phe 4 (subunit 1) participates in a T-shaped stacking interaction with the thymine ring of the ligand whereas Tyr 26 (subunit 2) provides a parallel aromatic stacking interaction. There is a potential hydrogen bond between the carbonyl oxygen of Asn 25 (subunit 2) and N3 of the thymine ring. There are no side chain interactions between the ligand ribose and the protein. The pyrophosphoryl moiety of the external aldimine is surrounded by Arg 329 of subunit 1 and Arg 213 and Tyr 219 of subunit 2. There is a decided lack of interactions between the protein and the pyranosyl group of the external aldimine. As is typical of the aminotransferases, the phosphate moiety of the PLP is involved in extensive hydrogen bonding interactions. Nine water molecules lie within 3.2 Å of the external aldimine.

As discussed in the Introduction, a preliminary X-ray analysis of PglE was reported in 2005.7 The structure of PglE reported here was determined via molecular replacement using, as a search probe, the Protein Data Bank entry 1O61. Although the 1O61 model contained coordinates for the two PLP cofactors in the dimer, the electron densities corresponding to these ligands were not convincing and suggested that, if present, they were at very low occupancy. Using the structure factors deposited in the Protein Data Bank, we removed the PLP moieties from the X-ray coordinate file and calculated an electron density map with Fo−Fc coefficients. This difference map suggested nine of the cysteine residues were oxidized, that some water molecules were incorrectly modeled into the density surrounding these cysteine residues, and that there was a string of electron density that corresponded nicely to three histidine residues wedged between Arg 329 in subunit 1 and Arg 213 and Asn 215 of subunit 2. Numerous side chains were built in only as alanine residues although there was clear electron density in maps calculated with Fo−Fc coefficients. Strikingly, Lys 184, which would be expected to form an internal aldimine with the cofactor, projects outwards towards the solvent in the 1O61 model.

A comparison of the PglE active site with the bound external aldimine versus that deposited under accession code 1O61 is presented in Figure 4(d). As can be seen, the first N-terminal residues and the Ser 24 to Gly 31 loop form part of the binding pocket for the thymine ring of the external aldimine. There is a dramatic reorientation of the Ser 24 to Gly 31 loop such that the α-carbons for Pro 29, for example, are displaced by ∼12 Å in the two models. Another remarkable change occurs in the conformation of the loop delineated by Tyr 180 to Gly 190. Because of the binding of the external aldimine, the loops adopt completely different orientations with the α-carbons of Ile 185, for example, shifted by ∼16 Å. Excluding these conformational differences, however, the α-carbons for the two PglE models correspond with a root-mean-square deviation of 0.41 Å.

There is another PglE coordinate file deposited into the Protein Data Bank under the accession code 1O69. In this model, the first subunit reportedly contains an internal aldimine with a PLP analogue ((2-amino-4-formyl-5-hydroxy-6-methylpyridin-3-yl) methyl dihydrogen phosphate) whereas the second subunit has only the bound analogue. Again, the electron density for the PLP analogue in the second subunit was not convincing, suggesting less than full occupancy. In addition, if the aldehyde form was bound, it might be expected to be in the hydrated state as observed, for example, in ColD, another member of the aminotransferase superfamily.17 The electron density for the internal aldimine in the first subunit was stronger than that for the cofactor in the second subunit, but not unambiguous. We subsequently calculated difference electron density maps using the coordinates and X-ray data deposited under accession code 1O69. Again, it appears that three cysteine residues were oxidized, that many side chains were modeled as alanines although there was clear Fo−Fc density extending from the β-carbons, and that in one place the carbonyl oxygen of Tyr 180 was pointed in the wrong direction, and a water molecule was built into where the carbonyl oxygen should have been positioned.

Comparison of PglE to PseC, DesI, and ArnB

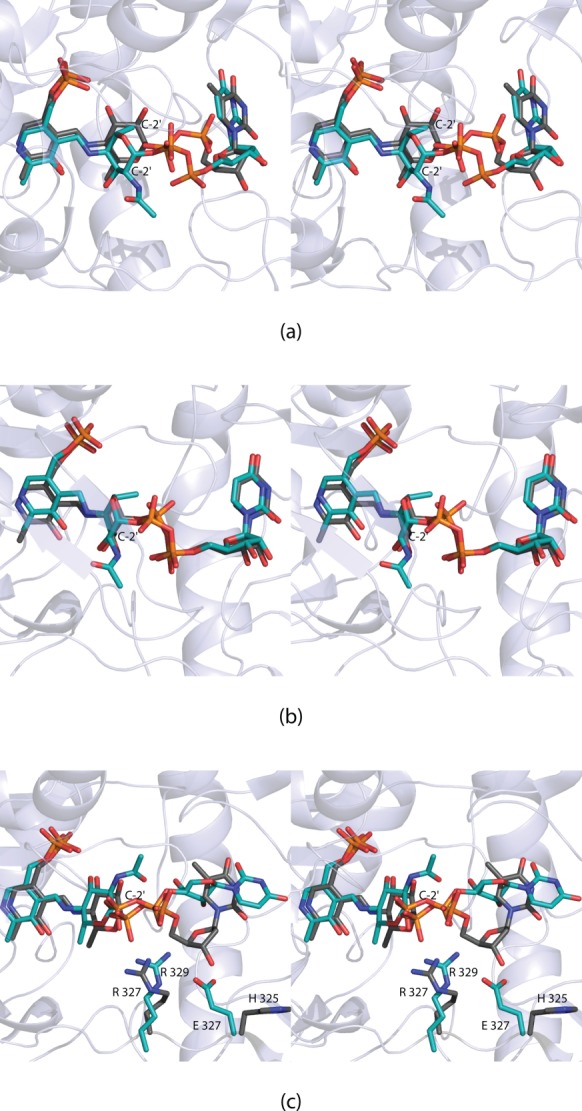

The first sugar aminotransferase structure to be reported with a bound external aldimine was that of PseC from H. pylori.6 The product of this enzyme has the C-4’ amino group in the axial orientation (Scheme 3). The structural investigation of PseC was followed by the X-ray analysis of DesI from S. venezuelae.9 The product of the DesI reaction has the amino group in the equatorial position (Scheme 3). A superposition of the active sites of these two enzymes revealed a nearly 180° rotation of the hexose moieties of the ligands, thereby explaining the axial versus equatorial amino transfer [Fig. 5(a)].9 Note that the nucleotide portions adopt similar conformations, although the positions of the α-phosphorus atoms differ by ∼2 Å.

Figure 5. Figure.

Comparison of the external aldimines observed in the sugar aminotransferases. The observed conformations of the ligands bound to DesI (gray) and PseC (teal) are shown in (a). There is an ∼180° rotation of the pyranosyl moieties. In (b) the conformations of the ligands, when bound to ArnB (gray) and PseC (teal), are displayed. Finally, in (c) the conformations of the ligands when bound to DesI (gray) and PglE (teal) are presented. In DesI, Arg 327 interacts with the pyrophosphoryl group of the ligand. This residue is conserved in PglE. In PglE, however, there is a change from a histidine to a glutamate residue, which precludes the ligand from adopting a similar conformation to that observed in DesI.

ArnB from S. typhimurium, like PseC, catalyzes an amino transfer reaction leading to the axial orientation at the C-4’ carbon (Scheme 3). A superposition of the active sites for ArnB and PseC is shown in Figure 5(b). As can be seen, the two ligands adopt similar conformations within the active site pockets. Unlike the structural analyses of both PseC and DesI where only the external aldimine complexes were solved, the structure of ArnB has been determined in both the internal and external states.10,11 The movements of the flexible loops observed in PglE do not occur in ArnB.

Given that both PglE and DesI lead to products with amino groups in the equatorial positions, it was expected that their external aldimine ligands would adopt similar conformations. As shown in Figure 5(c), the pyranosyl moieties are, indeed, in comparable positions. The orientations of the pyrophosphoryl and nucleotide portions, however, are significantly different. In DesI, the side chain of Arg 327 forms an electrostatic interaction with the pyrophosphoryl group of the ligand. This residue is conserved in PglE as Arg 329. However, in PglE there is a glutamate at position 327 that in DesI is a histidine residue. The side chain of Glu 327 in PglE forces the ribose of the ligand into a completely different position in the active site.

In conclusion, it can be safely predicted that the differences in stereochemistries of the sugar aminotransferase products arise primarily from the orientations of the pyranosyl rings in the active site pockets. Those enzymes that transfer the amino group to the axial position versus those that deliver it to the equatorial position have the pyranosyl rings of the sugars rotated by ∼180°. What is also clear from this investigation is that the orientation of the nucleotide portions of the substrates may be much more variable than ever envisioned. Furthermore, the dramatic movement of the loops defined by Ser 24 to Gly 31 and Tyr 180 to Gly 190 in PglE in the presence of the external aldimine could not have been accurately modeled. Thus this investigation once again emphasizes the continuing need for experimental data rather than relying solely on model building and bioinformatics approaches. Finally, this study underscores the need for caution when utilizing X-ray coordinates deposited in the Protein Data Bank.

Materials and Methods

Cloning of the pglE gene

A PglE gene cloned from C. jejuni NCTC11168 served as the starting template for PCR using Platinum Pfx DNA polymerase (Invitrogen). Primers were designed that incorporated NdeI and XhoI restriction sites. The PCR product was digested with NdeI and XhoI and ligated into pET28T, a laboratory pET28b(+) vector that had been previously modified to incorporate a TEV protease cleavage recognition site after the N-terminal polyhistidine tag.18 The amino acid sequence of the protein utilized in this investigation corresponds to that deposited in the Protein Data Bank (accession no. 1O61) with the exception of position 334, which is a threonine residue in the current model. In some strains of C. jejuni, this residue is a threonine. To trap the external aldimine, the conserved lysine at position 184 was converted to an alanine. This approach was previously done in our laboratory for the structural analysis of WlbE (PDB accession no. 3NYT). Finally, three glycine residues were added after the TEV recognition site to make it more accessible to cleavage.

Protein expression and purification

The pET28T-pglE plasmid was utilized to transform Rosetta2(DE3) Escherichia coli cells (Novagen). The cultures were grown in terrific broth supplemented with kanamycin and chloramphenicol at 37°C with shaking until an optical density of 0.8 was reached at 600 nm. The flasks were cooled in an ice bath, and protein expression was initiated with the addition of 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside, and the cells were allowed to grow at 16°C for 24 h.

The cells were harvested by centrifugation and disrupted by sonication on ice. The lysate was cleared by centrifugation, and PglE was purified with Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The histidine tag was removed by digestion with TEV protease. The protein was dialyzed against 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 200 mM NaCl and concentrated to 26 mg mL−1 based on an extinction coefficient of 0.98 (mg/mL)-1cm-1.

Preparation of UDP-2-acetamido-4-amino-2,4,6-trideoxy-d-glucose was performed using 2 mM UDP-GlcNAc, 50 mM monosodium glutamate, 50 mM HEPPS, 0.2 mM PLP, 0.5 mg mL−1 PglF, and 1.0 mg mL−1 PglE (Scheme 1). PglF was prepared as previously described.6 The reaction was incubated overnight at 37°C. Enzymes were removed by passage through an Amicon Ultra 10 kDa cutoff membrane. The reaction mixture was diluted and loaded onto a HiLoad 26/10 Q-sepharose column and purified by HPLC at a buffered pH of 4.0 with an ammonium acetate gradient of 0–450 mM over seven column volumes. The product sugar, which eluted at ∼250 mM ammonium acetate, was pooled, lyophilized, and reapplied to the same column and purified at pH 8.5 using an ammonium bicarbonate gradient of 0–800 mM over seven column volumes. The product sugar eluted at ∼400 mM ammonium bicarbonate.

Crystallization and structural analysis

Crystallization conditions were surveyed by the hanging drop method of vapor diffusion using a laboratory based sparse matrix screen at both room temperature and 4°C. X-ray diffraction quality crystals of the enzyme were subsequently grown from precipitant solutions containing 15–18% poly(ethylene glycol) 3350, 1 mM PLP, 10 mM UDP-2-acetamido-4-amino-2,4,6-trideoxy-d-glucose, and 100 mM MOPS (pH 7.0) at 21°C. The crystal morphology was distinctly bipyramidal, and most of the crystals were highly twinned in nature. After screening with numerous salt additives, it was found that crystals grown in the presence of tetraethylammonium chloride showed little to no twinning. The crystals belonged to the space group P41212 with unit cell dimensions of a=b=66.2 Å and c=169.0 Å. The asymmetric unit contained one subunit.

For X-ray data collection, the crystals were transferred to a cryoprotectant solution containing 27% poly(ethylene glycol) 3350, 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM tetraethylammonium chloride, 15% ethylene glycol, 0.5 mM PLP, and 100 mM MOPS (pH 7.0). X-ray data were collected at 100 K with a Bruker AXS Platinum 135 CCD detector controlled by the Proteum software suite (Bruker AXS Inc.). The X-ray source was Cu Kα radiation from a Rigaku RU200 X-ray generator equipped with Montel optics and operated at 50 kV and 90 mA. These X-ray data were processed with SAINT version 7.06A (Bruker AXS) and internally scaled with SADABS version 2005/1 (Bruker AXS). Relevant X-ray data collection statistics are listed in Table1. The structure was determined via molecular replacement with the software package PHASER and using as a search model the X-ray coordinates 1O61 from the Protein Data Bank.19 Iterative cycles of model building with COOT and refinement with REFMAC reduced the Rwork and Rfree to 18.8 and 25.4%, respectively, from 30 to 2.0 Å resolution.20–22

Glossary

- dTDP

thymidine diphosphate

- HEPPS

N-2-hydroxyethylpiperazine-N’-3-propanesulfonic acid

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- MOPS

3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid

- Ni-NTA

nickel nitrilotriacetic acid

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- PLP

pyridoxal 5’-phosphate

- PMP

pyridoxamine 5’-phosphate

- TEV

tobacco etch virus; Tris, tris-(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane

- UDP

uridine diphosphate

- UDP-GlcNAc

UDP-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-D-glucose.

References

- Sharon N. Celebrating the golden anniversary of the discovery of bacillosamine, the diamino sugar of a Bacillus. Glycobiology. 2007;17:1150–1155. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwm089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothaft H, Szymanski CM. Bacterial protein N-glycosylation: new perspectives and applications. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6912–6920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R112.417857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison MJ, Imperiali B. The renaissance of bacillosamine and its derivatives: pathway characterization and implications in pathogenicity. Biochemistry. 2014;53:624–638. doi: 10.1021/bi401546r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nothaft H, Szymanski CM. Protein glycosylation in bacteria: sweeter than ever. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:765–778. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knirel YA, Rietschel ET, Marre R, Zähringer U. The structure of the O-specific chain of Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 lipopolysaccharide. Eur J Biochem. 1994;221:239–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenhofen IC, McNally DJ, Vinogradov E, Whitfield D, Young NM, Dick S, Wakarchuk WW, Brisson JR, Logan SM. Functional characterization of dehydratase/aminotransferase pairs from Helicobacter and Campylobacter: enzymes distinguishing the pseudaminic acid and bacillosamine biosynthetic pathways. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:723–732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger J, Sauder JM, Adams JM, Antonysamy S, Bain K, Bergseid MG, Buchanan SG, Buchanan MD, Batiyenko Y, Christopher JA, Emtage S, Eroshkina A, Feil I, Furlong EB, Gajiwala KS, Gao X, He D, Hendle J, Huber A, Hoda K, Kearins P, Kissinger C, Laubert B, Lewis HA, Lin J, Loomis K, Lorimer D, Louie G, Maletic M, Marsh CD, Miller I, Molinari J, Muller-Dieckmann HJ, Newman JM, Noland BW, Pagarigan B, Park F, Peat TS, Post KW, Radojicic S, Ramos A, Romero R, Rutter ME, Sanderson WE, Schwinn KD, Tresser J, Winhoven J, Wright TA, Wu L, Xu J, Harris TJ. Structural analysis of a set of proteins resulting from a bacterial genomics project. Proteins. 2005;60:787–796. doi: 10.1002/prot.20541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenhofen IC, Lunin VV, Julien JP, Li Y, Ajamian E, Matte A, Cygler M, Brisson JR, Aubry A, Logan SM, Bhatia S, Wakarchuk WW, Young NM. Structural and functional characterization of PseC, an aminotransferase involved in the biosynthesis of pseudaminic acid, an essential flagellar modification in Helicobacter pylori. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8907–8916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512987200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgie ES, Holden HM. Molecular architecture of DesI: a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of desosamine. Biochemistry. 2007;46:8999–9006. doi: 10.1021/bi700751d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noland BW, Newman JM, Hendle J, Badger J, Christopher JA, Tresser J, Buchanan MD, Wright TA, Rutter ME, Sanderson WE, Muller-Dieckmann HJ, Gajiwala KS, Buchanan SG. Structural studies of Salmonella typhimurium ArnB (PmrH) aminotransferase: a 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose lipopolysaccharide-modifying enzyme. Structure. 2002;10:1569–1580. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00879-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Sousa MC. Structural basis for substrate specificity in ArnB. A key enzyme in the polymyxin resistance pathway of Gram-negative bacteria. Biochemistry. 2014;53:796–805. doi: 10.1021/bi4015677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönfeld W, Kirst HA. Macrolide antibiotics. Germany: Birkhäuser Verlag; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raetz CR, Reynolds CM, Trent MS, Bishop RE. Lipid A modification systems in gram-negative bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:295–329. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.76.010307.145803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden HM, Cook PD, Thoden JB. Biosynthetic enzymes of unusual microbial sugars. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:543–550. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. The pymol molecular graphics system. San Carlos, CA, USA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Cook PD, Thoden JB, Holden HM. The structure of GDP-4-keto-6-deoxy-D-mannose-3-dehydratase: a unique coenzyme B6-dependent enzyme. Protein Sci. 2006;15:2093–2106. doi: 10.1110/ps.062328306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoden JB, Holden HM. The molecular architecture of human N-acetylgalactosamine kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32784–32791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505730200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. J Appl Cryst. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Cryst. 2004;D60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Cryst. 2010;D66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta Cryst. 1997;D53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]