Abstract

Hereditary mixed polyposis syndrome (HMPS) is characterised by the development of mixed morphology colorectal tumours and is caused by a 40 kb duplication that results in aberrant epithelial expression of the mesenchymal Bone Morphogenetic Protein antagonist, GREM1. Here we use HMPS tissue and a mouse model of the disease to show that epithelial GREM1 disrupts homeostatic intestinal morphogen gradients, altering cell-fate, that is normally determined by position along the vertical epithelial axis. This promotes the persistence and/or reacquisition of stem-cell properties in Lgr5 negative (non-expressing) progenitor cells that have exited the stem-cell niche. These cells form ectopic crypts, proliferate, accumulate somatic mutations and can initiate intestinal neoplasia, indicating that the crypt base stem-cell is not the sole cell-of-origin of colorectal cancer. Furthermore, we show that epithelial expression of GREM1 also occurs in traditional serrated adenomas, sporadic pre-malignant lesions with a hitherto unknown pathogenesis and these lesions can be considered the sporadic equivalents of HMPS polyps.

Introduction

The intestinal mucosa is covered by a self-renewing layer of epithelium making it ideal for the study of tissue-specific stem-cells and cell fate determination. Lineage tracing experiments have helped identify genes selectively expressed by stem-cells. One of these marker genes, the Wnt target leucine-rich-repeat-containing G protein coupled receptor 5 (Lgr5) is expressed in crypt-base columnar cells (CBC) within the crypt base stem-cell niche that also comprises surrounding Paneth cells and intestinal sub-epithelial myofibroblasts1. In homeostasis, cell fate determination is coupled to position along the crypt-villus (vertical) axis of the epithelium and this is controlled by strict gradients of interacting morphogens - soluble molecules produced by a restricted region of a tissue that form an activity gradient away from source. The phenotypic response of a cell is determined by its position within this concentration gradient2.

Wnt and Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) pathways form polarized expression gradients along the epithelial vertical axis. Stem-cell division and transit amplifying cell proliferation are driven by high Wnt/low BMP levels in the lower half of the crypt whereas daughter cell differentiation and apoptosis is controlled by low Wnt/high BMP at the luminal surface 3. These gradients are maintained partly by diffusion of ligands, but also by the restricted paracrine secretion of ligand-sequestering BMP antagonists, such as Gremlin1, Gremlin2 and Noggin that are exclusively derived from sub-crypt myofibroblasts and act locally within the crypt base stem cell niche (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 3). These antagonists are thought to prevent BMP activity within the niche, promoting intestinal stem-cell stemness 4.

Dysregulation of the homeostatic Wnt/BMP balance can promote intestinal tumorigenesis. The conventional adenoma-carcinoma sequence is commonly initiated by activation of Wnt signaling in the epithelium through Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC) or β-catenin (CTNNB1) mutation 5. However, disrupted BMP signaling can also predispose to intestinal polyps and cancer 6. Human Juvenile Polyposis syndrome (JPS) results from inactivating germline BMPR1A or SMAD4 mutations and epithelial expression of Noggin under the control of villin or fatty acid binding protein (Fabpl) regulatory elements causes a JPS-like phenotype in the mouse 7,8. Recently we demonstrated that human Hereditary Mixed Polyposis syndrome (HMPS) is caused by a 40 kb duplication upstream of the BMP antagonist GREM1 which results in ectopic gene expression and resultant BMP signalling antagonism throughout the epithelium (Supplementary Fig. 1c–e)9. HMPS is an autosomal dominant condition and untreated patients develop colorectal cancer at a median age of 47 10. HMPS is named for the distinctive morphology of the polyps with individual lesions exhibiting mixed adenomatous crypts, epithelial serration and dilated cysts (Fig. 1a).

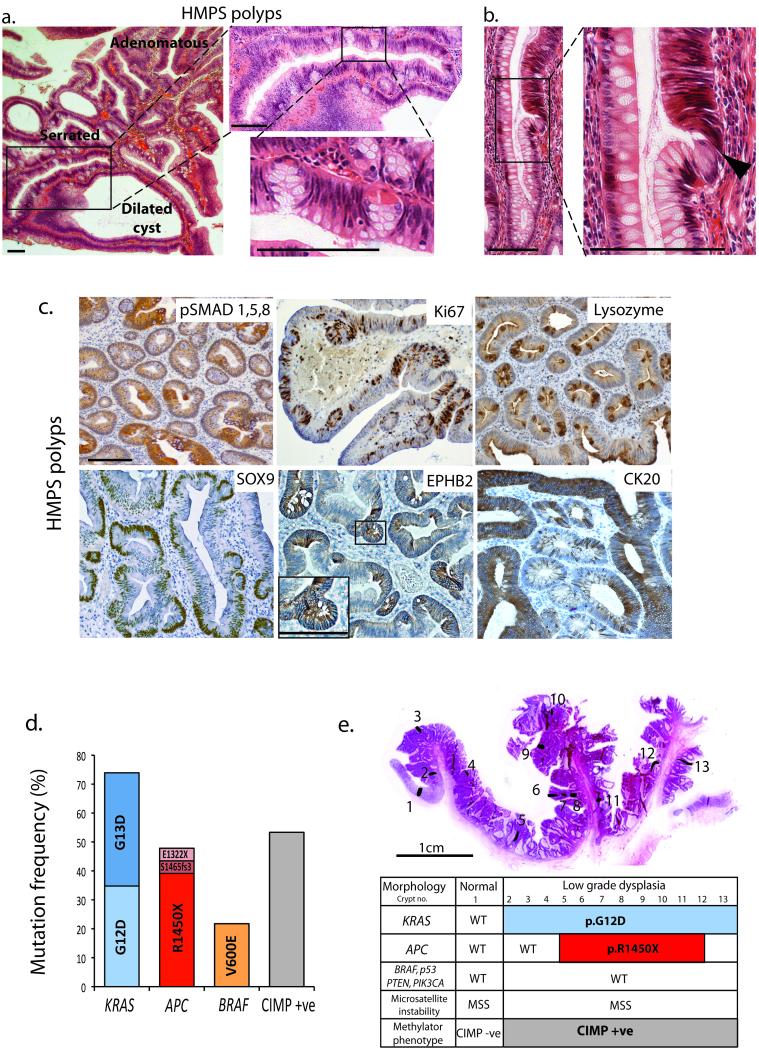

Fig. 1. Human HMPS polyps.

(a) H&E of HMPS polyp showing mixed adenomatous, serrated and dilated cyst morphology and close up of ectopic crypts growing orthogonally to crypt axis. (b) Dysplastic cells (black arrowhead) emerging from an ectopic crypt rather than from the crypt base. (c) Immunostaining of HMPS polyps showing patchy loss of p-SMAD1,5,8 stain, Ki67 stain in proliferating ectopic crypt foci cells and ectopic lysozyme stain in dysplastic crypts (upper panels). Sox9 and EPHB2 immunostaining is increased whereas staining for the differentiation marker CK20, is lost in the ectopic crypt foci of HMPS polyps (lower panels) (n > 10 polyps for all stains). (d) Candidate gene (epi)genetic mutation spectra in HMPS polyps. (e) Laser-capture isolation of individual crypts across HMPS lesions. Spatial distinction of mutant clones allowed inference of mutation timing (see also Supplementary Fig. 2). Scale bars are 100 μm unless stated.

Daughter cells that exit the stem-cell niche migrate along the vertical intestinal axis, progressively differentiating into tissue appropriate specialised cells and the majority of these cells (enterocytes, colonocytes and goblet cells) are shed into the lumen within five days. Although rare post-mitotic cells such as enteroendocrine or tuft cells can persist outside the stem cell niche 11, it has been considered that the perpetual stem-cell at the crypt base is the cell-of-origin of colorectal cancer (CRC) 12. Here, we use a mouse model of HMPS to show that disruption of homeostatic BMP gradients by aberrant epithelial expression of GREM1/Grem1 alters cell fate determination allowing cells outside the crypt base stem-cell niche to act as tumour progenitors. Furthermore, we demonstrate that this is the pathogenic mechanism underpinning the development of human HMPS polyps and some sporadic intestinal tumours.

Results

HMPS polyps are characterised by ectopic crypt foci formation

All crypts in HMPS individuals have epithelial GREM1 expression, yet the polyps are discrete, often containing mixed dysplastic and non-dysplastic areas. Histopathological review of the polyps revealed ectopic crypt foci (ECFs) that developed orthogonally to the crypt axis and contained actively proliferating cells (Fig. 1a–c, Supplementary Fig. 1b). Within some polyps, we identified dysplastic cells emerging from ECFs rather than from the crypt base (Fig. 1b) and hypothesised that dysplasia resulted from somatic mutations within the ECFs.

Sequencing of HMPS polyps revealed a high frequency of CRC driver mutations. Mutually-exclusive KRAS or BRAF mutations were seen in 100% of lesions with APC, predominantly p.Arg1450X, mutations seen in 48%. The CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP)13 was present in 53% of lesions tested (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 2a). In contrast, we found a very low frequency of known driver mutations in a cohort of JPS polyps with germline BMPR1A mutations (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Clonal ordering following microdissection of individual HMPS crypts revealed clonal KRAS or BRAF mutations detected throughout entire polyps, including ECFs and the different morphological crypt subtypes (Supplementary Fig. 2d–e). In contrast APC mutations were often spatially restricted to dysplastic areas, indicating that Wnt dysregulation was a subsequent event (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig 2a, c).

A mouse model of HMPS

In order to understand more about the pathogenesis of HMPS, we generated Vill-Grem1 mice expressing mouse Grem1 cDNA under the control of the intestinal epithelium-specific Villin promoter. Epithelial expression of Grem1 was confirmed by in situ hybridisation (Fig. 2c) and qRT-PCR, with highest levels in the proximal small bowel (Supplementary Fig. 3d). BMP signalling was assessed using BMP ligand and target gene expression (Supplementary Fig. 3e) and immunohistochemistry to phosphorylated Smad1,5,8, which was absent throughout the vertical axis of the intestines of transgenic mice (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 4b).

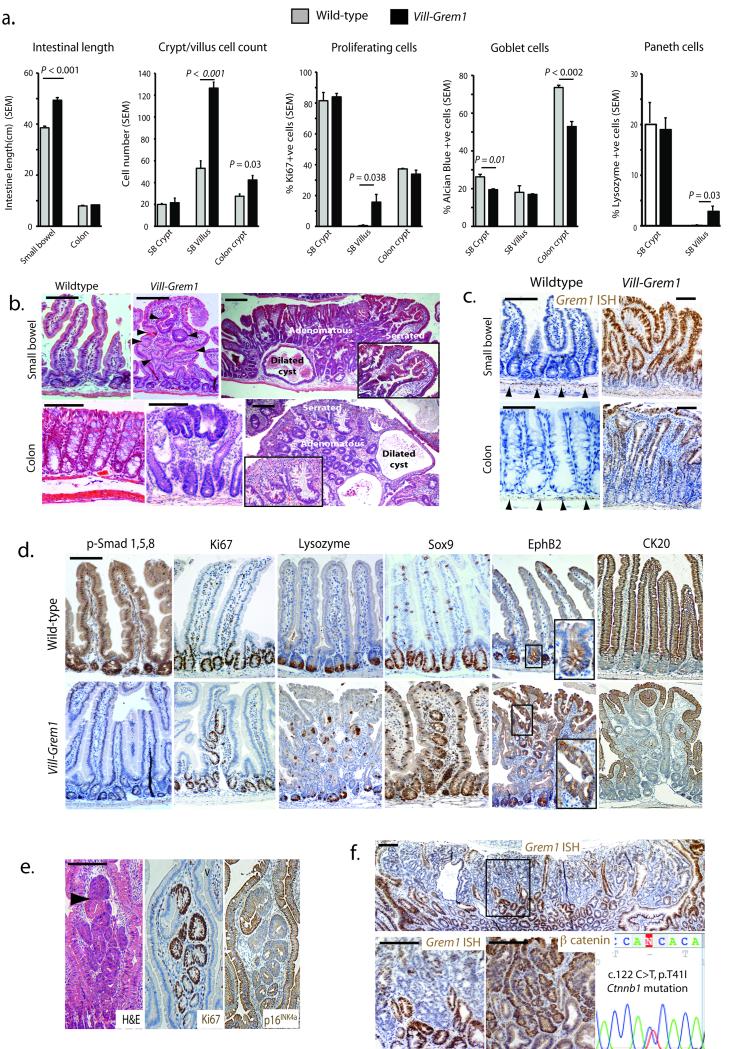

Fig. 2. Vill-Grem1 mouse phenotype.

(a) Macroscopic and microscopic phenotyping of Vill-Grem1 versus wild-type mouse intestine. Significant differences were noted in intestinal length and diameter (n = 10, P < 0.001, t-test), villus (n = 50) and colonic crypt (n = 100) cell count (P = 0.001, t-test), villus proliferating cell proportion (n = 50, P = 0.03, t-test), small bowel (n = 50, P < 0.002, t-test) and colonic goblet cells count (n = 50, P = 0.01, t-test) and proportion of lysozyme positive Paneth cells on the villus (n = 50, P = 0.038, t-test). In all cases: student t-test using two-tailed, unpaired and unequal variance was employed. The data from each group did not significantly deviate from a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test). (b) Top left: Wildtype mouse small bowel 1 (SB1). Top middle: SB1 of a three-month old Vill-Grem1 mouse, with widened villi containing intravillus ectopic crypts (black arrowheads). Top right: dysplastic polyp formation in a seven-month old Vill-Grem1 animal exhibiting mixed morphology with serrated (inset), adenomatous and dilated cyst phenotypic regions. Lower left: wildtype mouse colon. Lower middle: early colonic lesion with luminal surface dysplasia distant from the crypt basal stem-cell niche. Lower right: colonic polyps in a seven-month old mice with mixed crypt morphology (serrated crypts, inset). (c) In situ hybridization (ISH) for mouse Grem1 with normal intestinal expression of Grem1 exclusively from the sub-crypt myofibroblasts (black arrowheads). Aberrant epithelial expression is seen in early small intestinal and colonic lesions from the Vill-Grem1 mouse. (d) Immunohistochemical analysis Vill-Grem1 versus wildtype small intestine shows loss of p-Smad1,5,8 throughout the crypt-villus axis, with Ki67, Sox9 and EphB2 staining all present in the villus ectopic crypts. Ck20 differentiation marker staining was lost in villus ECFs (n > 20 polyps for all stains). (e) Dysplasia arising in intravillus ectopic crypts (black arrowhead) with active cell proliferation correlating with p16Ink4a stain loss. (f) Grem1 ISH in Vill-Grem1 mouse tissue shows loss of Grem1 expression in a large polyp, which correlates with nuclear β–catenin staining, resulting from a Ctnnb1 p.T41I mutation. Scale bars are 100 μm.

Transgenic animals’ small intestines were 28% longer than those of their wild-type littermates (n = 10, P < 0.001, t-test) partly due to an increase in the size and cell count of the villi (P < 0.001, t-test) (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4a). Although there was no change in the proportion of Ki67 positive proliferating cells in the crypts there was a significant increase in the number of proliferating cells on the villi of Vill-Grem1 mice (P = 0.038, t-test, Fig. 2a, d). Analysis of epithelial cell lineages showed a decrease in the number of goblet cells in both small intestinal (P = 0.01, t-test) and colonic crypts (P = 0.002, t-test) and the presence on the villus of lysozyme positive Paneth cells (P = 0.038, t-test), a cell type normally restricted to the small intestinal crypt base (Fig. 2a, d). At three months of age, Grem1-expressing ectopic crypts were seen developing orthogonally to the vertical axis of the widened and flattened small bowel villi (Fig. 2b–c). Ectopic crypts budded off to become actively proliferating intravillus lesions which subsequently developed dysplastic features with concomitant loss of p16Ink4a expression (Fig. 2e). By seven months, these lesions had progressed to a pan-intestinal polyposis (Supplementary Fig. 4c) with median 183 polyps per mouse. Small intestinal lesions had a mixed serrated/adenomatous/cystic phenotype characteristic of the lesions seen in HMPS (Fig. 2b).

Epithelial Grem1 and membranous β-catenin expression were seen in unaffected intestine and small polyps but some larger polyps with more advanced dysplasia exhibited marked down-regulation of epithelial Grem1 expression, which correlated with foci of cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin staining. Sequencing demonstrated activating Ctnnb1 mutations in some of these lesions (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 4d).

Although total colonic length was unchanged, the proximal colonic folds were exaggerated. Hyperplastic appearing colonic crypts had an increased cell count (P = 0.03, t-test, Fig. 2a). Crypt crowding meant that ECFs could not be easily distinguished in the colon but colonic dysplasia originated at the luminal surface and progressed to form lesions that contained all three morphological crypt phenotypes (Fig. 2b).

These data indicate that aberrant epithelial Grem1 expression results in a progressive intestinal polyposis with small intestinal and colonic polyps containing the three characteristic morphologies seen in human HMPS lesions. Throughout the bowel, early lesions can be seen developing outside the crypt basal stem-cell niche - on the luminal surface in the colon and within ECFs that bud into the villus of the small intestine. Down-regulation of epithelial expression in some advanced lesions indicates that epithelial Grem1 is no longer required once epithelial somatic mutation events have occurred.

Vill-Grem1 mice have enlargement of the progenitor cell pool

As the villus ECFs appeared to be the origin of small intestinal dysplasia in the Vill-Grem1 mouse, we looked for increased expression of stem-cell markers on the villi of these animals. We crossed Vill-Grem1 mice with Lgr5-EGFP reporter mice 1 but were unable to detect discrete Lgr5-EGFP positive cells outside the stem-cell niche, with none seen in the villus ECFs (Fig. 3a). To confirm this, we mechanically separated crypts and villi from Vill-Grem1 and age-matched wild-type mice and used qRT-PCR to detect stem-cell markers aberrantly expressed in the Vill-Grem1 mouse villus compartment. Of the stem-cell markers tested, Sox9 showed the greatest expression in villus cells (Fig. 3b) and immunostaining for Sox9 confirmed ectopic crypt-specific expression in both human HMPS and mouse tissue (Figs. 1c and 2d).

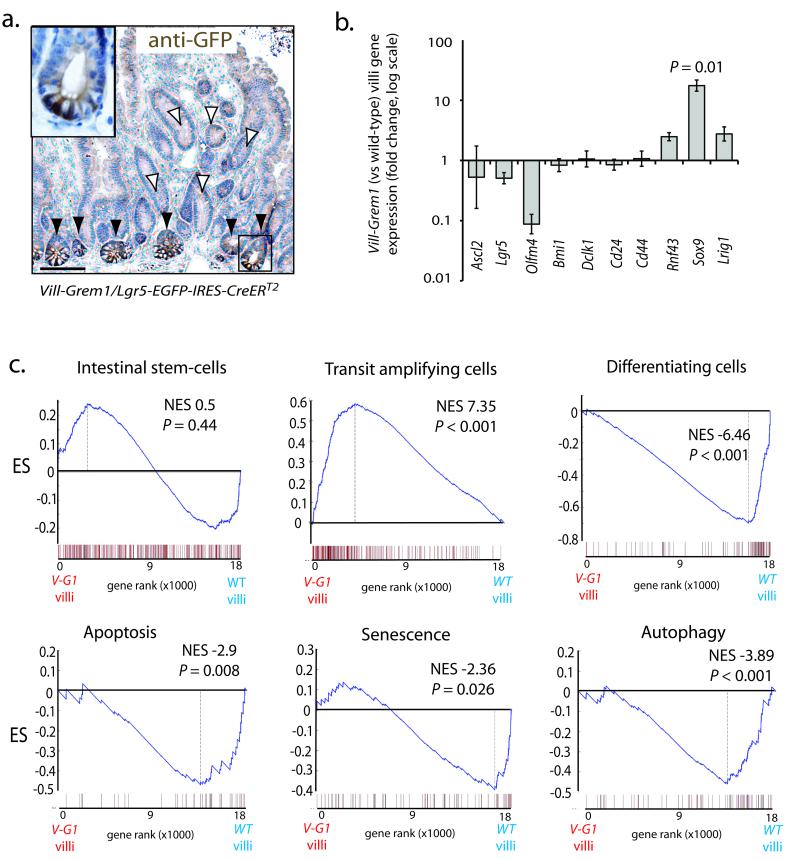

Fig. 3. Gene expression analysis of separated crypt/villus compartments in Vill-Grem1 mice.

(a) Vill-Grem1 mice were crossed with Lgr5-EGFP-IRES-CreERT2 mice and tissues stained with anti-GFP antibody. No Lgr5/EGFP positive cells were seen in the ectopic crypts on the villi (white arrowheads) but were found as expected in the underlying crypt bases (black arrowheads and inset). (b) qRT-PCR analysis of villus stem-cell marker expression in individual Vill-Grem1 villi versus wild-type littermate villi. There was a significant increase in expression of Sox9 (n = 10, P = 0.01, t-test) in Vill-Grem1 villi. (c) Villi from Vill-Grem1 and wild-type littermates underwent gene expression microarray and GSEA analysis using established gene program sets. GSEA plots shown are for Vill-Grem1 (n = 5) versus wildtype villi (n = 6). Enrichment score is calculated using Kolomogrov-Smirnov test (Supplementary reference8). P-value is calculated using a permutation test. Scale bars are 100 μm.

Next, we examined the global mRNA expression profiles of transgenic versus wild-type crypt and villus compartments using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) (Fig. 3c). GSEA confirmed no significant enrichment of Lgr5-based intestinal stem-cell profiles on the villi of transgenic mice 14,15. In contrast there was enrichment of villus gene programs characterising proliferating, early transit amplifying cells 15 (normalised enrichment score (NES) 7.35, P < 0.001) with concomitant reduced levels of genes normally expressed in differentiating cells 15 (NES= −6.46; P < 0.001) Furthermore, we also observed reduced expression of villus genes regulating apoptosis 16 (NES-2.9; P = 0.008), cellular senescence 17 (NES-2.36; P = 0.026) and autophagy (NES-3.89; P < 0.001) 18, homeostatic processes that have all been shown to have early lesion tumour suppressor roles 19,20.

A decreasing gradient of EphB2 expression from the crypt base along the vertical axis of the intestine has been used to distinguish intestinal stem (EphB2high), progenitor (EphB2medium) and differentiating (EphB2low/absent) cell populations in the mouse and human intestine 15. Consistent with this and our GSEA findings, EphB2 protein was aberrantly expressed in the ECFs of both Vill-Grem1 transgenic mouse and human HMPS polyps (Figs. 1c and 2d). Cytokeratin 20 protein expression was used as a marker of differentiated cells and was reduced or absent in the ECFs of both Vill-Grem1 mouse and human HMPS polyps (Figs. 1c and 2d)

Taken together, these data indicate that epithelial Grem1 expression disrupts the coupling of cell-fate to position along the vertical axis of the intestine. Although cell-fate/position uncoupling does not generate an ectopic Lgr5 positive stem-cell population it does cause expansion of an Lgr5 negative, proliferating progenitor cell population on to the villi. Concomitant down-regulation of differentiation, apoptosis, senescence and autophagy gene programs means there is a marked expansion of a progenitor cell pool outside of the intestinal stem-cell niche that can be defined immunohistochemically as Sox9+; EphB2+; Ck20− (Figs. 1c and 2d).

Epithelial Grem1 promotes persistence of somatically mutant villus cells

In order to test the clonogenic, tumour-forming potential of villus cells in our Vill-Grem1 mouse model, we utilised the established in vitro enteroid technique that uses media supplemented by the niche-derived morphogens, epidermal growth factor (E), Noggin (N) and R-Spondin (S) 21. Normal appearing crypts from Vill-Grem1 mice readily formed branching enteroids not only in these standard conditions but also in the absence of media Noggin supplementation (ES media). Endogenous epithelial Grem1 expression could be overcome by addition of competing BMP ligands 2, 4 and 7 to the media (ES+rBMP2,4,7) which inhibited Vill-Grem1 enteroid development indicating that the culture of non-dysplastic crypts was dependent on a source of BMP antagonist (Fig. 4a, heatmap). In contrast, culture of dysplastic mouse adenomas (ApcMin/−) generated non-branching clonogenic cystic spheroids, which could be successfully initiated and propagated in the absence of media BMP antagonist, or following addition of recombinant BMP ligands (Fig. 4a). These data further support the notion that BMP antagonism is dispensable once Wnt activating somatic mutations have occurred 12,22

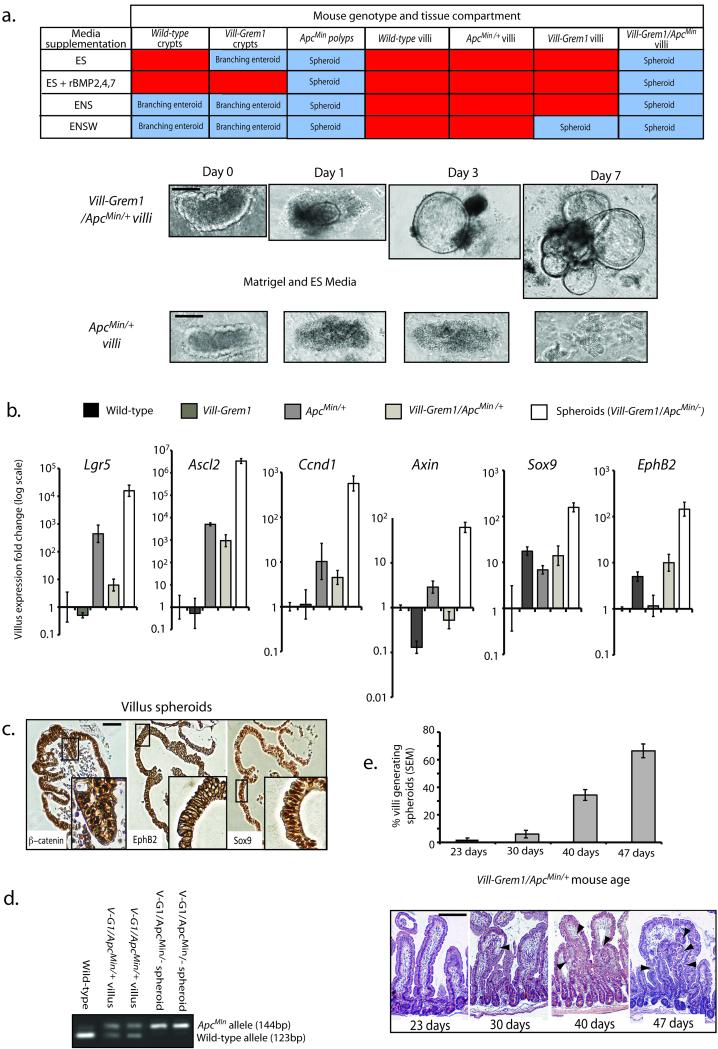

Fig. 4. In vitro villus cell clonogenicity.

(a) Non-dysplastic small intestinal crypts from wild-type and Vill-Grem1 mice readily formed branching enteroids with similar efficiency in standard conditions (ENS media). Vill-Grem1 crypts also formed lasting enteroids in the absence of Noggin in the medium (ES media), although the effect of endogenous Grem1 expression could be overcome by addition of competing recombinant BMP ligands 2, 4, and 7 (ES+rBMP2,4,7 media). Culture of ApcMin polyp tissue resulted in non-branching spheroid generation in all media conditions, indicating dispensability of BMP antagonist in somatically mutant cells. Villi dissected from wild-type and ApcMin/+ mice dissociated and died regardless of media supplementation. Villi dissected from Vill-Grem1 mice (in Wnt3A supplemented (ENSW) media) and Vill-Grem1/ApcMin mice (in all media conditions) could form proliferative spheroid lesions that could be repeatedly passaged and propagated long-term. Vill-Grem1/ApcMin mice generated villus spheroids efficiently in the absence of Noggin as a media supplement and spheroid generation could not be abrogated by addition of competing BMP ligands indicating BMP antagonist independent growth. Abbreviations of media supplements E: Epidermal growth factor; N: Noggin; S: R-Spondin; W: Wnt3A. (b) qRT-PCR analysis of effect of mouse genotype on villus Wnt target gene expression (versus wild-type) showed that a single Apc hit was sufficient to increase endogenous individual villus Wnt target gene expression including the stem-cell markers Lgr5 and Ascl2. Expression of the progenitor cell markers Sox9 and EphB2 was significantly increased in Vill-Grem1 animals (n = 10 villi for each strain, P < 0.01, t-test) and emergent spheroids had a further increase in both Wnt target and progenitor marker genes. (c) Villus spheroid immunostain showing nuclear β–catenin staining, membranous EphB2 and nuclear Sox9 stain. (d) Selection of somatically mutant cells on the villus of Vill-Grem1/ApcMin/+ mice. Extracted non-dysplastic villi entering into culture retained a residual wild-type Apc allele, whilst emergent spheroids had lost this allele. (e) There was an increase in the percentage of villi transforming into clonogenic spheroids with increasing age of Vill-Grem1/ApcMin/+ mice. Histology review showed that this increase correlated with the emergence of villus ectopic crypts (black arrowheads). Scale bars are 100 μm.

Next, we separated and cultured villi from Vill-Grem1 and age-matched wild-type littermates in order to assess whether aberrant epithelial Grem1 expression influenced the tumour-forming capacity of villus cells. In the presence of recombinant Wnt3a (ENSW media), clonogenic cystic spheroids did develop from Vill-Grem1 mouse villi but these were rare events (< 0.1% of villi). We reasoned that the inefficiency of this transformation resulted from the short half-life of the media Wnt3a 23. To counter this, we generated Vill-Grem1/ApcMin/+ mice to activate the endogenous Wnt pathway. In extracted villi, a germline ApcMin/+ mutation did induce an increase in villus Wnt target gene expression. However, epithelial Grem1 reduced the expression of these Wnt targets in an Apc mutant background, whilst increasing the expression of the progenitor markers Sox9 and EphB2 (Fig. 4b). These results were consistent with our GSEA findings.

We then repeated villus culture taking care to sample from regions without microscopically visible polyps. Villi from wild-type, and age matched ApcMin/+ mice did not survive in culture. By contrast, villi from Vill-Grem1/ApcMin/+ animals rapidly formed clonogenic spheroids that could be successfully propagated in long-term culture and were unaffected by the addition of competing BMP ligand to the media (Fig. 4a). Somatic loss of heterozygosity of the wild-type Apc allele was seen in all spheroids and this was coupled with a further increase in Wnt target gene expression (Fig. 4b–d). Spheroids could be formed from mice as young as 23 days old, but transformation efficiency increased with the age of the mouse and histological analysis showed that this coincided with the emergence of villus ECFs (Fig. 4e).

Taken together these results suggest that modest Wnt activation induced by a single Apc mutation alone is insufficient for the clonogenic growth of villus spheroids in non-dysplastic ApcMin/+ villi. However, epithelial Grem1-induced disruption of cell fate allows the persistence of progenitor cells on the villus, and if Wnt activating somatic mutations are present within this accumulating, expanded progenitor population, these cells are capable of generating BMP antagonist independent spheroid growth in the cell culture environment.

Grem1 and activated Wnt signalling act in a synergistic fashion

Crossing Vill-Grem1 mice with ApcMin/+ mice caused a profound exacerbation of intestinal tumorigenesis, with tumour burden in two-month old compound transgenic animals greater than that seen in animals with the individual parental mutations (Fig. 5a). Vill-Grem1/ApcMin/+ mice had to be sacrificed at mean 57 days as opposed to > 200 days for ApcMin/+ and > 250 days for Vill-Grem1 animals. Interestingly, morphological elements of the polyps from both parental strains could be seen in individual lesions in double transgenic animals. In the colon, superficial aberrant crypt foci progressed to lesions with luminal surface, not crypt base dysplasia. In the small bowel, dysplasia arose from intravillus ectopic crypts contained within non-dysplastic serrated epithelium (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 5a). Laser dissection of these different morphological elements demonstrated somatic loss of the wild-type Apc allele exclusively in the dysplastic crypts within the serrated villi (Fig. 5b), indicating that somatic Apc inactivation provides a selective advantage and occurs rapidly in actively proliferating villus cells.

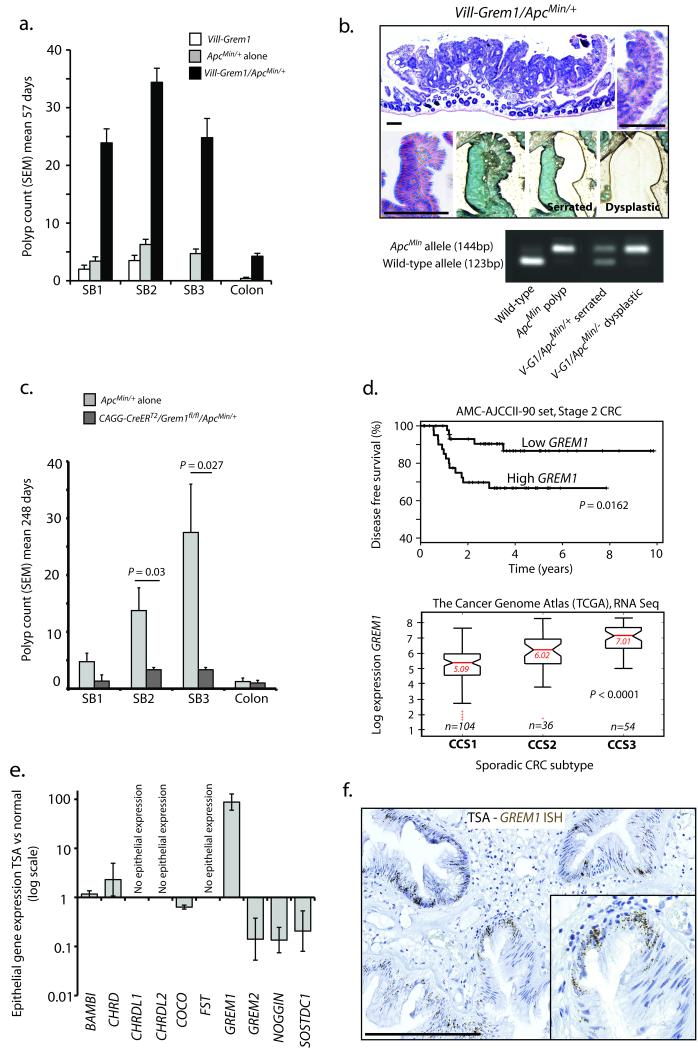

Fig. 5. Effect of Grem1 on conventional Wnt driven tumorigenesis and pathogenic role in human sporadic traditional serrated adenomas.

(a) Double-mutant Vill-Grem1/ApcMin/+ mice had a rapidly progressive intestinal phenotype, with a greater polyp burden than the parental strains at mean 57 days (Vill-Grem1 n = 5; ApcMin/+ n = 7; Vill-Grem1/ApcMin/+ n = 8, Pinteraction<0.002 for all regions of the bowel, generalized linear regression incorporating a multiplicative interaction term between Apc mutation and Grem1 status). Polyp size was also significantly greater in Vill-Grem1/ApcMin/+ animals (Pinteraction < 0.001, linear regression, data not shown). The data from each group did not significantly deviate from a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test) (b) Vill-Grem1/ApcMin/+ mouse polyps had central dysplastic areas with a sharp cut off between enclosing serrated epithelium. Laser dissection of the different morphological types revealed Apc loss of heterozygosity in the dysplastic tissue. (c) Conditional inactivation of physiological Grem1 significantly reduced conventional, Wnt-initiated tumourigenesis in CAGG-CreERT2/Grem1fl/fl/ApcMin/+ mice at mean 248 days (n = 4 mice for test and non-injected control, P = 0.027, t-test unpaired with unequal variances). The data from each group did not significantly deviate from a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test). (d) Top panel: above-median expression of GREM1 in the AMC-AJCCII-90 human CRC set was associated with a significant reduction in disease-free survival (P = 0.0162, log rank test). Bottom panel: the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) RNAseq data was used to classify tumours into the three colon cancer subtypes (CCS) described by De Sousa et al 28. A highly significant correlation was seen between CCS3 subtype cancers and high whole tumour GREM1 expression (P < 0.0001, ANOVA). (e) qRT-PCR measurement of known BMP antagonists from individual fresh TSAs (22 crypts from four different lesions) compared with surrounding normal crypts. (f) In situ hybridsation for GREM1 in archival human TSA samples showed aberrant epithelial GREM1 mRNA expression in TSA epithelium (brown dots). Scale bars are 100 μm.

Grem1 knockout reduces Wnt driven tumour progression

Next we generated Cagg-CreERT2/Grem1fl/fl mice and induced widespread, multi-compartmental Grem1 knockout with high-dose tamoxifen at six weeks 24. Successful Grem1 knockout was confirmed with qRT-PCR and in situ hybridisation, but Cagg-CreERT2/Grem1fl/fl animals had no consistent change in the expression of BMP constituents, Wnt targets or stem cell markers, and developed no significant phenotype indicating possible functional redundancy or buffering of BMP antagonists in adult intestinal homeostasis (Supplementary Fig. 6). As we, and others have seen epithelial and/or stromal upregulation of GREM1 in some, but not all, sporadic human intestinal polyps, cancers and cell lines 25-27 (Supplementary Fig. 5d and 7a), we examined the effect of knockout of physiological Grem1 expression on Wnt-initiated tumour burden by crossing Cagg-CreERT2/Grem1fl/fl with ApcMin mice. Grem1 knockout caused a significant reduction of ApcMin/+ mouse polyp burden (Pinteraction < 0.002 for all regions of the bowel, linear regression, Fig. 5c), and size (Pinteraction < 0.001, linear regression, Supplementary Fig. 6d) demonstrating that knockout of stromal and/or aberrant epithelial Grem1 expression ameliorates the development of conventional intestinal tumourigenesis. To investigate whether GREM1 might influence the behavior of human tumours, we analysed associations between GREM1 expression and survival in two publically-available CRC datasets. Individuals with above median GREM1 expression had significantly shorter disease-free survival in both data sets (AMC-AJCCII-90 set, stage II: log-rank P = 0.0162, Moffit-Vanderbilt-Royal Melbourne set, stages I-III: log-rank P = 0.0112) (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 5e).

Collectively these results strongly support the notion that GREM1 and Wnt signaling act in a synergistic fashion in the initiation and progression of intestinal polyps. We propose that in both human and mouse neoplasia resulting from aberrant GREM1 expression, there is a strong selective pressure for somatic Wnt activation in actively dividing ECFs, whereas in conventional tumourigenesis, stromal-derived GREM1 provides a favourable microenvironment for the persistence of somatically mutant cells.

Epithelial GREM1 expression in sporadic traditional serrated adenomas

Based on gene expression and somatic mutation profiles De Sousa et al. recently divided sporadic colorectal cancer into three main molecularly distinct subtypes: CCS1 enriched for tumours with chromosomal instability (CIN), CCS2 enriched for tumours with microsatellite instability (MSI) and a third group, CCS3. This group was more heterogenous, appeared to arise from serrated adenoma precursors and gave rise to an aggressive subset of cancers with poor prognosis 28. To see if whole tumour GREM1 expression correlated with this classification we used The Cancer Genome Atlas RNA-Seq data to match sporadic tumour samples to the published CCS1, CCS2 and CCS3 subtypes and found a highly significant correlation between high GREM1 expression and CCS3 subtype tumours (P < 0.0001, ANOVA) (Fig. 5d).

Traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs) are distal colonic polyps with hitherto unknown pathogenesis that make up about 2% of the lesions removed at colonoscopy. The characteristic histological feature of these sporadic lesions is the development of ectopic crypt foci29. We collected and dissected individual crypts from four fresh TSA specimens. Individual crypt analysis of BMP antagonist expression revealed a mean 87-fold upregulation of epithelial GREM1 expression over surrounding normal mucosa (Fig. 5e), significantly greater than that seen in conventional, hyperplastic and sessile serrated adenomas (P < 0.01, t-test, Supplementary Fig. 7a). Epithelial GREM1 expression was validated in a set of ten paraffin-embedded TSAs using mRNA in situ hybridisation. Clearly visible epithelial GREM1 expression was detected in a further 6/10 polyps (Fig. 5f). Immunohistochemical assessment and (epi)mutation analysis revealed a very similar molecular phenotype and somatic mutation pattern to HMPS polyps (Supplementary Fig. 7b–c). CIMP was seen in 33% of TSAs, and p16INK4A promoter methylation correlated with p16INK4A protein down-regulation and resultant cell proliferation - similar to that seen in the Vill-Grem1 mouse (Supplementary Fig. 7d). These data strongly suggest that the ECFs that characterize sporadic TSAs also arise from disruption of homeostatic morphogen gradients and that in the majority of cases this is the consequence of aberrant epithelial GREM1 expression. Furthermore it is likely that TSAs give rise to CCS3 subtype tumours that are often refractory to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) targeted therapy and have an unfavourable prognosis 28.

Discussion

Here we use a mouse model of a human disease to demonstrate the pathogenetic mechanism in hereditary mixed polyposis syndrome (Fig. 6). Aberrant epithelial GREM1 disrupts intestinal morphogen gradients, altering daughter cell fate and promoting the persistence of Lgr5 negative progenitor cells in ECFs distant from the crypt base. Cell proliferation within ECFs means that progenitor cells are prone to tumour causing somatic mutations. Human HMPS polyps progress through KRAS/BRAF mutation and frequent selection of a very restricted set of APC mutations. In the mouse model Grem1 initiated lesions advance through p16 loss and Ctnnb1 mutation and once somatic mutation has occurred in some advanced lesions, epithelial Grem1 expression becomes redundant. Ex vivo culture of transgenic mouse villi demonstrates that persistence of somatically mutated villus cells can initiate clonogenic growth. Using mouse models we have also shown the exacerbation or amelioration of conventional, Wnt-driven neoplasia initiation by Grem1 overexpression or knockout respectively. Lastly we show that epithelial expression of GREM1 also occurs in sporadic traditional serrated adenomas, lesions similarly characterized by the development of aberrantly proliferating cells in ectopic crypt foci, and that these lesions can thus be considered the sporadic equivalents of HMPS polyps.

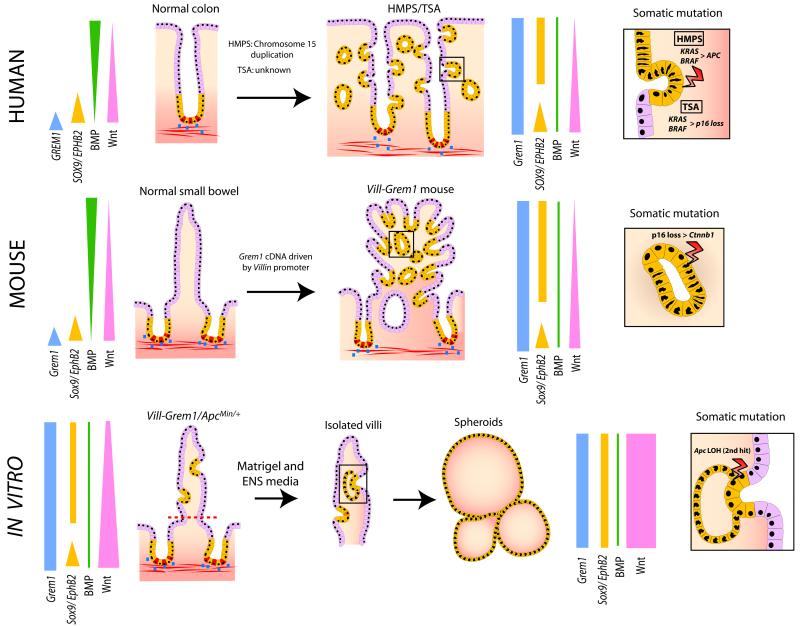

Fig. 6. Model summarising the proposed mechanistic consequences of disrupted GREM1 morphogen gradients.

Aberrant ectopic epithelial expression of GREM1 disrupts the coupling of cell-fate determination to position along the crypt-villus axis and allows persistance and expansion of an Lgr5 negative progenitor cell pool (characterized by aberrant SOX9 and EPHB2 expression) which form orthogonal ectopic crypt foci. Aberrant cell-proliferation in this progenitor cell population within these ECFs predisposes towards somatic (epi)mutation events and gives rise to neoplastic transformation (inset boxes). In vitro, the persistence of somatically mutated progenitor cells in dissected villi gives rise to clonogenic tumour spheroid growth from cells that have exited the crypt basal stem-cell niche. Coloured bars represent morphogen and gene expression gradients in the normal and pathological states. Blue dots represent physiological Grem1 expression from peri-cryptal myofibroblasts. CBC stem cells are coloured red.

Multiple BMP antagonists have been described, with varying levels of intestinal expression and importance in intestinal homeostasis. There is much greater physiological expression of both GREM1 and GREM2 than Noggin in human intestinal stroma (Supplementary Fig. 5f) and the importance of GREM1 has been highlighted by its causative role in HMPS 9 and the association of sporadic CRC with GREM1 common allelic variants 30. The association of germline inactivating Noggin mutations with skeletal conditions like symphalangism and tarsal-carpal coalition31 correspondingly reflects the greater significance of Noggin’s role in bone development than in intestinal homeostasis. Previous investigation of the pathogenesis of Juvenile Polyposis led to the generation of Vill–Xenopus Noggin 7 and Fabp1-Xenopus Noggin 8 mice. Both models initially developed intravillus ectopic crypts before progressing to a juvenile polyposis-like phenotype. The differences between small intestinal polyp morphology in these models and the Vill-Grem1 mouse may reflect the Xenopus origin of the Noggin, the relative importance of these different antagonists in intestinal homeostasis or fundamental differences in the ligand targets or biology of these BMP antagonists which share minimal sequence homology. Human HMPS and JPS are pathogenically and morphologically distinct32 and the profound differences in pathogenesis, phenotype and somatic pathway progression between these conditions highlights how subtle alterations in the BMP signaling cascade can have different effects on intestinal tumourigenesis.

The histogenesis of colorectal neoplasia has historically been a subject of some debate: the classical ‘bottom-up’ model favours dysplasia arising from the crypt basal stem-cell niche 33 whereas the ‘top-down’ model proposes that dysplasia originates at the luminal surface and spreads downwards 34. The identification of the Lgr5 positive CBC stem-cell at the very base of the crypt 1 seemed to have settled the argument in favour of the ‘bottom up’ model. Here we demonstrate that pathological disruption of morphogen gradients in animal models and human inherited and sporadic disease causes a profound change in the fate of cells situated outside of the crypt base stem/proliferative zone, with expansion of an Lgr5 negative progenitor cell population. These cells form ectopic crypt structures, proliferate, accumulate somatic mutations and are capable of initiating intestinal neoplasia indicating that the crypt basal stem-cell is not the exclusive cell-of-origin of all subtypes of colorectal cancer. Conceivable histogenic origins of this progenitor population includes the vertical expansion of a crypt base progenitor population containing variably competent stem cells, the generation of an ectopic niche for a migrated Lgr5 negative stem cell or dedifferentiation of post-mitotic specialized intestinal epithelial cells. Very recently Schwitalla et al. have shown that activated NF-KB induced mucosal inflammation in combination with constitutive epithelial Wnt signalling can also promote the initiation of neoplasia from cells situated outside the crypt base stem-cell niche 35. Taken together these studies highlight the importance of the intestinal microenvironment in maintaining stem-cell homeostatic control and cell-fate determination. This work challenges the concept of a strict unidirectional tissue organisational hierarchy in the intestine and demonstrates that a ‘top-down’ model of tumour histogenesis may fit some subtypes of inherited, sporadic and inflammation-associated colorectal cancers.

Online Methods

Generation and genotyping of Vill-Grem1 mice

Grem1 cDNA was amplified from normal mouse intestinal mesenchyme using the following primers F 5′- GACGTCGACCAATGGAGAGAC –3′ and R 5′ GACGTCTGACGGACAAGCAA-3′, adding an AatII restriction enzyme site at each end. The excised cDNA fragment was then cloned into the Villin-MES-SV40polyA plasmid (kind gift of Sylvie Robine) downstream of the 9 Kb Villin promoter (active after embryonic day E9). This plasmid was linearised with Kpn1 digestion. Transgenic mice were derived by pronuclear injection using standard methods by the Transgenic Facility, WTCHG, Oxford University. To identify successful transmission, tail snips were taken from mice at weaning age and amplified by PCR using the following primers; F 5′-GAGGTCGAGGCTAAAGAAGA-3′ and R 5′-ACCTAGTGTCGGGCATCTCC-3′. Successful transmission was confirmed by Southern blot using standard methods. In brief, the probes were amplified using the following primers F 5′-AGGTAGGGAGGTCGAGGCTA-3′ and R 5′-CAACGCTCCCACAGTGTATG-3′. The probes were then radioactively labelled by random priming with α32P dCTP using the random primed labelling kit (Roche) as previously described 36. 20 μg of genomic DNA were digested to completion with SphI and MscI restriction enzymes. The digested DNA was electrophoresed on 0.8% gels in 1x TBE overnight. After denaturation, the gels were blotted onto Hybond N+ membrane (GE healthcare) overnight, UV crosslinked (Stratalinker, Stratagene) and hybridised with the radiolabelled probes. Hybridisation and washing of Southern blots was performed using standard methods and detected a 2079 bp region of the inserted transgene in founder mice (Supplementary Fig. 3c). Three founder lines were established and all developed an identical phenotype. One line was arbitrarily chosen to be taken forward.

Mouse procedures

All procedures were carried out in accordance to Home Office UK regulations and the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. All mice were housed at the animal unit at Functional Genomics Facility, Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, Oxford University. All strains used in this study were maintained on C57Bl/6J background for ≥ 6 generations. To induce recombination in conditional lines mice were treated with 1 mg tamoxifen by intra peritoneal injection for five days. Genotyping protocols for the ApcMin/+ 37, Cagg-CreERT2 and Gremfl/fl 38 mice have previously been reported.

Tissue preparation and histology

Mice were sacrificed at pre-defined time points or when showing symptoms of intestinal polyps (anaemia, hunching) by cervical dislocation. The intestinal tract was removed immediately and divided into small intestine (proximal/SB1, middle/SB2 and distal/SB3) and large intestine. The intestines were opened longitudinally, using a gut preparation apparatus 39, washed in PBS, fixed overnight in 10% neutral buffered formalin (NBF). For scoring of polyps, gut preparations were stained with 0.2% methylene blue for 10 s, washed in PBS for 20 min and polyps were counted/measured using a dissecting microscope at 3x magnification. Specimens of 10% formalin-fixed tissue were embedded in paraffin and then sectioned at 4 μm. Fixed specimens were embedded and H&E stained following standard protocols.

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections (4 μm) were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrated through graded alcohols to water. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked using 1.6% H2O2 for 20 min. For antigen retrieval, sections were pressure cooked in 10 mmol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 5 min. Sections were blocked with 10% serum for 30 min. Slides were incubated with primary antibody for 2 h. The following antibodies have been used in this study; Alkaline phosphatase (Abcam, ab65834), β-catenin (BD, 610154), Caspase3 (R and D, AF835), Cdkn2a/ p16Inka (mouse) (Thermoscientific, PA1-30670), CDKN2A/p16Inka (human) (Abcam, ab51243), Chromogranin A (Abcam, ab15160), Cytokeratin 20 (Abcam, ab118574), EphB2 (R and D, AF467), GFP (Life Technologies, A-6455), Ki67 (mouse) (DAKO, TEC-3), KI67 (human) (DAKO, MIB-1), Lysozyme (DAKO, EC 3.2.1.17), pSmad1/5/8 (Cell Signalling, 9511L) and Sox9 (Millipore, ab5535). Appropriate secondary antibodies were applied for 1 h at room temperature. Sections were then incubated in ABC (Vector labs) for 30 min. DAB solution was applied for 2–5 min and development of the colour reaction was monitored microscopically. Slides were counterstained with haematoxylin, dehydrated, cleared and then mounted.

Alcian-blue stain for goblet cells

Sections were dewaxed in xylene for 5 min, then rehydrated through graded ethanols (100%, 90%, 70%) for 5 min each followed by 2 min in tap H20. Slides were then stained in alcian-blue solution (Sigma) for 30 min, then washed in running tap H20 for 2 min, before being rinsed in dH20. Slides were then stained in nuclear fast red solution (Sigma) for 5 min and washed in running tap H20 for 1 min. Slides were then dehydrated through degraded alcohols for 2–5 min each, before mounting a coverslip with DPX.

Immunohistochemical quantification

For mouse phenotype quantification analyses, we used no less than three animals per group (control and experimental, at age ten months). To assess overall change in epithelial cell numbers between Vill-Grem1 mice compared to age-matched, wildtype counterparts we microscopically captured images of haemotoxylin-eosin stained 4 μm sections of the small intestine and colon at 10x magnification and then randomly selected crypts and villi, counting individual cells within these compartments. An average of 50 individual villi within the small intestine and 100 crypts were counted. Similarly, 100 crypts of the colon were counted giving us enough power to run a t test. Data is represented as total number of cells per crypt/villus. Excel was used to calculate means and standard error. To determine the proliferative index in experimental and control mice, a total of three mice per group were used. Small intestinal and colon sections were immunohistochemically labelled with Ki67 antibody. Microscopic images at 20x magnification were taken and number of Ki67 positive cells per total epithelial cells in randomly selected 50 crypts (colon or small intestine) and 50 villi (small intestine) were counted. Data is represented as a percentage of Ki67+ cells in each compartment. The percentage of goblets cells in epithelial cells of the villus (small intestine) and crypt (small intestine/colon) was quantified by counting Alcian blue positive cells in at least 50 crypts of the colon/small intestine and 50 villi from small intestine in three mice of each genotype. Similarly, quantification of Paneth cells was determined by counting lysozyme positive cells over total epithelial cells in three Vill-Grem1 and three wildtype mice. To assess apoptosis, cleaved Caspase 3 positive cells over total number of epithelial cells per crypt (50 crypts in total) in small intestine/colon, and per villus (50 villi in total) in small intestine were counted. No randomisation or blinding of mouse genotypes was used. All statistical analyses were done in Excel.

Individual crypt and villus isolation, RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

For both mouse and human individual crypt/villus isolation, biopsies were washed with PBS and incubated in 5 ml dissociation media (30 mM EDTA in DMEM without Ca2+ and Mg2+, 0.5 mM DTT, 2% RNAlater (Life Technologies) for 10 min at room temperature. The digested tissue was then transferred to PBS and shaken vigorously for 30 s to release individual crypts and villi. Individual structures were selected using a drawn out glass pipette under a dissection microscope and transferred to RLT buffer ready for subsequent RNA extraction with the RNeasy microkit (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNAs were treated with DNase I to degrade residual DNA. When required, complementary DNA was reverse transcribed in vitro using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). When using cDNA generated from individual crypts or villi, pre-amplification of these cDNAs was necessary prior to qRT-PCR. The TaqMan PreAmp (Applied Biosystems) kit was used following manufacturer’s instructions. Absolute quantification qRT-PCR was performed on the ABI 7900HT cycler (Applied Biosystems) with GAPDPH/Gapdh serving as an endogenous control. A list of TaqMan Gene Expression assays (Applied Biosystems) used is available on request. The primary assumption in analyzing Real time PCR results is that the effect of a gene can be adjusted by subtracting Ct number of target gene from that of the reference gene (ΔCt). The deltaCt for experimental and control can therefore be subject to t-test, which will yield the estimation of ΔΔCt. In all cases the data met the normal distribution assumption of the t-test.

In situ hybridisation (ISH)

4 μm sections were prepared using DEPC (Sigma) treated H20. In situ hybridisation was carried out using the GREM1 (312831), PPIB (313901), Grem1 (314741) Ppib (313911) and DapB (310043)(Advanced Cell Diagnostics) probes and the RNAscope 2.0 HD Detection Kit (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) following manufacturer’s instructions.

Mouse Apc loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH)

Apc allelic status was assessed by a PCR assay described previously using primers F 5′-TCTCGTTCTGAGAAAGACAGAAGCT-3′ and R 5′-TGATACTTCTTCCAAAGCTTTGGCTAT-3′ 40. PCR products were electrophoresed on 2.5% agarose gels. Briefly, the amplification of the ApcMin allele resulted in a 155-bp PCR product with one HindIII site, whereas the 155-bp product for the Apc+ allele contained two HindIII sites. HindIII digestion of PCR-amplified DNA from ApcMin/+ heterozygous tissue generates 123-bp and 144-bp products. PCR products from tissue with LOH displayed only one band (144-bp).

Laser capture microdissection

MembraneSlide 1.0 PEN slides (Zeiss) were exposed to UV light for 30 min before mounting 8 μm sections. These slides were baked at 37°C for 30 min, then dewaxed for 5 min and rehydrated through graded alcohols to water for 3–5 min each. The slides were then briefly dipped in methyl green, washed in water and dried at 37°C for 1 h. Laser capture microdissection was performed with the laser capture PALM system (Zeiss). DNA was extracted using the PicoPure DNA extraction kit (Arcturus).

Sequencing

Sequencing of gDNA was carried out using the 2x Big Dye Terminator v3.1 reagent (Applied Biosystems). Unincorporated dye terminators were removed with the DyeEx 2.0 Spin kit (Qiagen) and the purified products were run on the ABI 3730 DNA analyser (Applied Biosystems). Primers are available on request.

Determination of the CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP)

500 ng of DNA was bisulphite treated using the EZ DNA Methlyation-Gold kit (Zymo) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Subsequent determination of CIMP status was performed using real-time PCR based protocol (MethyLight) assaying a five marker panel composed of CACNA1G, IGF2, NEUROG1, RUNX3 and SOCS1 described in 41. Samples with ≥3 of five markers positive for methylation is considered CIMP positive whilst a sample with ≤2 of the five markers positive for methylation is considered CIMP negative.

Microsatellite stability determination

A multiplex PCR (Qiagen) was performed for the markers Bat25, Bat26 and D2S123 using the following primers Bat25 F 5′-TCGCCTCCAAGAATGTAAGT-3′, R 5′-TCTGGATTTTAACTATGGCTC, Bat26 F 5′-TGACTACTTTTGACTTCAGCC-3′ and R 5′-TTCTTCAGTATATGTCAATGAAAACA-3′, D2S123 F 5′-AAACAGGATGCCTGCCTTTA-3′ and R 5′-GGACTTTCCACCTATGGGAC-3′. The forward primers were differentially dye-labelled (Bat25 and D2S123 Hex labelled, Bat26 FAM labelled). The PCR products were run on a semi-automated ABI3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) by Sequencing Service, Zoology Department, Oxford University. Results were analysed using GeneMarker software (SoftGenetics). Microsatellite instability was assigned when two or more markers showed instability.

Culture of mouse intestinal crypts

Mouse intestinal crypts were isolated and cultured as described by Sato et al 22. In brief, crypts were isolated, resuspended in Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and plated out in 24-well plates. The basal culture medium (advanced Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F12 supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin, 10 mmol/L HEPES, Glutamax, 1x N2, 1x B27 (all from Invitrogen), and 1 mmol/L N-acetylcysteine (Sigma)) was overlaid containing the following growth factors; Epidermal Growth Factor at 50 ng/ml (Life Technologies), Noggin at 100 ng/ml (PeproTech) and R-spondin1 at 500 ng/ml (R and D) [ENS media]. The media was changed every two days.

To see if addition of recombinant BMP ligands to the media could compete with the endogenous overexpression of Grem1 and to demonstrate the necessity of a source of BMP antagonist, Vill-Grem1 crypt enteroids were grown in media lacking Noggin (ES media) together with a range of rBMP ligand 2, 4 and 7 concentrations (rhBMP2, rmBmp4 and rmBmp7 (R and D) 0-1000 ng/ml of each of the three BMP ligands). Cells cultured in media containing rBmp concentrations of 50-1000ng/ml of each ligand, were not viable (enterospheres formed and were still present on day two but completely disaggregated by day five).

Culture of intestinal adenomas (ApcMin)

From symptomatic ApcMin/+ animals the intestines were opened longitudinally and adenomas were scraped with a coverslip. The first scrape of material was discarded and the subsequent scrapes were collected into sterile PBS. The material was gently washed with PBS and then centrifuged at 100 g for three min. The material was then plated out in 24-well plates in Matrigel (BD Biosciences). The wells then overlaid with Epidermal Growth Factor at 50 ng/ml (Life Technologies), R-spondin1 at 500 ng/ml (R and D) and Gremlin1 at 100 ng/ml (R and D) [EGS media]. After spheroids had formed (four days of culture) Gremlin1 was subsequently withdrawn from the media [ES media]. Adenoma spheroids were comparable when maintained in both EGS and ES media. In the following experiment, adenomas were cultured in ES media immediately on removal from the animals and again spheroids were found and were comparable with the EGS control. In summary recombinant Gremlin1 is not required for the expansion or maintenance of ApcMin adenoma spheroids. This concurs with previous findings that neither R-spondin or Noggin are required for the expansion and maintenance of ApcMin adenoma spheroids 22.

Culture of mouse intestinal villi

Vill-Grem1 animal intestines were opened longitudinally and the villi were scraped off with a coverslip. The first scrape of material was discarded and the subsequent scrapes were collected into sterile PBS. The material was gently washed with PBS and then centrifuged at 100 g for 3 min. The villi were then plated out in 24-well plates in Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and were overlaid by standard media that was additionally supplemented with mWnt3a at 100 ng/ml (ENSW media) (R and D systems). The media was changed every two days. To calculate the percentage efficiency of villi transformation the number of villi per well were counted after seeding (day 0) and the number of spheroids present on day four. Multiple wells were plated out for each time point. Spheroids were cultured from Vill-Grem1/ApcMin/+ as described above, although in addition recombinant Bone morphogenetic proteins (as above) were added to the media in an attempt to out-compete the antagonist effect of endogenous overexpression of Grem1 in this model. Spheroids formed and grew in all of these concentrations of BMP ligands showing the overexpression of Grem1 is no longer required for the growth and maintenance of villus spheroids.

Passaging and embedding of spheroids

After the intestinal villi had been cultured for appropriately a week and had grown into spheroid structures they were passaged by adding cold media to melt the Matrigel and subsequently re-plating in fresh Matrigel. To collect material for embedding, the Matrigel was melted by adding cold media, then multiple wells were combined. The cells were fixed with 500 μl PFA was 30 min at room temperature, centrifuged at 5000 rpm and resuspended in 150 μl 2% agarose (in PBS). The paraffin embedded cell pellet was then processed and embedded using standard protocols.

DNA extraction

To extract DNA from crypt, villi and spheroids the QiaAmp Micro kit (Qiagen) was used following manufacturer’s instructions.

Gene expression arrays

For GEP study we used n=6 controls and n=6 experimental groups to have a good estimate of the mean expression as well as to give us sufficient power for the t-test. Raw data from Illumina gene expression arrays (MouseWG-6_V2_0_R0_11278593_A chips) was processed after removing one outlier sample from initial quality control (detection score of < 0.95 of the background intensity for majority of probes) using the VSN (variance-stabilisation and normalisation) algorithm (Supplementary Table 1). We applied a filter by taking a detection score of > 0.95 of the background intensity distribution for all samples to consider a probe detectable, resulting in a total of 24,854 detectable probes. Differentially expressed genes between experimental (Vill-Grem1 small intestinal crypts (n = 6 mice)/villi (n = 5 mice)) and normal (wildtype small intestinal crypt (n = 6 mice)/villi (n = 6 mice)) were identified using Student’s t-test by running “ttest2” command in MATLAB® (Supplementary Table 2). Gene expression data is available on Gene Expression Omnibus, NCBI (accession number GSE62307).

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was performed using Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics and gene shuffling permutations as described 42. Genes were ranked by computing their differential expression in the experimental versus age-matched normal samples by the Student’s t-test method. If multiple probes were present for a gene, probe with the highest absolute differential expression between experimental and normal was selected. We used gene shuffling with 1,000 permutations to compute the P-value for the enrichment score. A list of gene signatures14-19 used in the enrichment analysis is given in Supplementary Table 3a, b. If the signature was from human dataset, we mapped these human genes to their mouse orthologs using the sequence-based method available from MGI (http://www.informatics.jax.org/).

Human colorectal cancer patient cohorts

Two publically available patient cohorts were downloaded from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) using the R BioConductor package GEOquery. The first set comprises 90 stage II CRC patients treated in the Academic Medical Center in Amsterdam, defined by the GEO accession number GSE33114 (AMC-AJCCII-90 set} 28. The second set contains 345 colorectal cancer (CRC) patients, defined by GEO accession numbers GSE14333 and GSE17538 (Moffit-Vanderbilt-Royal Melbourne set)15. Both sets are explained in detail in Supplementary Table 1 of De Sousa et al28.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated using the R package survival. The median expression value of GREM1 was used to segregate patients into low- or high-GREM1 expressors. P value was calculated using the log-rank test as informative covariates for Cox proportional hazards (such as stage) were not present in all data sets and because the test is robust to the high degree of right-censored data present.

RNA-Seq data from sporadic colorectal cancer patients was downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Data portal (https://cancergenome.nih.gov) and normalized using Voom in Limma package. Tumour samples were matched to the published CRC subtypes CCS1, CCS2 and CCS3 as described by De Sousa et al 28. If for any given patient multiple samples were profiled, we randomly selected one sample for further analysis. The Analysis Of Variance (ANOVA) test was used to compare the mean expression value of GREM1 across multiple patients. We assessed whether GREM1 expression levels in the TCGA cohort correlated with any of the CCS1, CCS2, CCS3 sub-types.

Ethics

Ethical approval for use of archival HMPS tissue was provided by the Southampton and South-West Hampshire Research Ethics Committee A (REC 06/Q1702/99). Ethical approval for the collection and use of endoscopic and archival TSA samples was obtained from the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee A (REC 10/H0604/72.) Informed consent for tissue use in research was obtained from all patients prior to endoscopic or surgical procedure. All mouse experiments were completed in accordance with UK Home Office regulations under the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986 (project license PPL30/2763).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Cancer Research UK Clinician Scientist Fellowship A16581 to SJL and Programme Grant A16459 to IT. Core funding to the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics was provided by the Wellcome Trust (090532/Z/09/Z). We thank the transgenics core and the staff of the Functional Genomics Facility at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics.

References

- 1.Barker N, van Es J, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, et al. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van den Brink G, Offerhaus G. The morphogenetic code and colon cancer development. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hardwick JC, Van Den Brink GR, Bleuming SA, Ballester I, Van Den Brande JM, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 is expressed by, and acts upon, mature epithelial cells in the colon. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:111–121. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scoville D, Sato T, He X, Li L. Current view: intestinal stem cells and signaling. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:849–864. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hardwick J, Kodach L, Offerhaus G, van den Brink G. Bone morphogenetic protein signalling in colorectal cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:806–812. doi: 10.1038/nrc2467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haramis AP, Begthel H, van den Born M, van Es J, Jonkheer S, et al. De novo crypt formation and juvenile polyposis on BMP inhibition in mouse intestine. Science. 2004;303:1684–1686. doi: 10.1126/science.1093587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batts LE, Polk DB, Dubois RN, Kulessa H. Bmp signaling is required for intestinal growth and morphogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:1563–1570. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaeger E, Leedham S, Lewis A, Segditsas S, Becker M, et al. Hereditary mixed polyposis syndrome is caused by a 40-kb upstream duplication that leads to increased and ectopic expression of the BMP antagonist GREM1. Nat Genet. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ng.2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitelaw S, Murday V, Tomlinson I, Thomas H, Cottrell S, et al. Clinical and molecular features of the hereditary mixed polyposis syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:327–334. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9024286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westphalen CB, Asfaha S, Hayakawa Y, Takemoto Y, Lukin DJ, et al. Long-lived intestinal tuft cells serve as colon cancer-initiating cells. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:1283–1295. doi: 10.1172/JCI73434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barker N, Ridgway R, van Es J, van de Wetering M, Begthel H, et al. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature. 2009;457:608–611. doi: 10.1038/nature07602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weisenberger DJ, Siegmund KD, Campan M, Young J, Long TI, et al. CpG island methylator phenotype underlies sporadic microsatellite instability and is tightly associated with BRAF mutation in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2006;38:787–793. doi: 10.1038/ng1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Munoz J, Stange DE, Schepers AG, van de Wetering M, Koo BK, et al. The Lgr5 intestinal stem cell signature: robust expression of proposed quiescent ‘+4’ cell markers. Embo J. 2012;31:3079–3091. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merlos-Suarez A, Barriga FM, Jung P, Iglesias M, Cespedes MV, et al. The intestinal stem cell signature identifies colorectal cancer stem cells and predicts disease relapse. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;8:511–524. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qiagen Biosciences Curated apoptosis array. 2012 http://www.sabiosciences.com/rt_pcr_product/HTML/PAMM-012Z.html.

- 17.Qiagen Biosciences Curated cellular senescence array. 2012 http://www.sabiosciences.com/rt_pcr_product/HTML/PAMM-050Z.html.

- 18.Qiagen Biosciences Curated autophagy array. 2012 http://www.sabiosciences.com/rt_pcr_product/HTML/PAMM-084Z.html.

- 19.Bieging KT, Mello SS, Attardi LD. Unravelling mechanisms of p53-mediated tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:359–370. doi: 10.1038/nrc3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brech A, Ahlquist T, Lothe RA, Stenmark H. Autophagy in tumour suppression and promotion. Mol Oncol. 2009;3:366–375. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, van de Wetering M, Barker N, et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009;459:262–265. doi: 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sato T, Stange DE, Ferrante M, Vries RG, Van Es JH, et al. Long-term expansion of epithelial organoids from human colon, adenoma, adenocarcinoma, and Barrett’s epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1762–1772. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dhamdhere GR, Fang MY, Jiang J, Lee K, Cheng D, et al. Drugging a stem cell compartment using Wnt3a protein as a therapeutic. PLoS One. 2014;9:e83650. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayashi S, McMahon AP. Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: a tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev Biol. 2002;244:305–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewis A, Freeman-Mills L, de la Calle-Mustienes E, Giraldez-Perez RM, Davis H, et al. A Polymorphic Enhancer near GREM1 Influences Bowel Cancer Risk through Differential CDX2 and TCF7L2 Binding. Cell Rep. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Segditsas S, Sieber O, Deheragoda M, East P, Rowan A, et al. Putative direct and indirect Wnt targets identified through consistent gene expression changes in APC-mutant intestinal adenomas from humans and mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sneddon J, Zhen H, Montgomery K, van de Rijn M, Tward A, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein antagonist gremlin 1 is widely expressed by cancer-associated stromal cells and can promote tumor cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14842–14847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606857103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Sousa E.M. F, Wang X, Jansen M, Fessler E, Trinh A, et al. Poor-prognosis colon cancer is defined by a molecularly distinct subtype and develops from serrated precursor lesions. Nat Med. 2013;19:614–618. doi: 10.1038/nm.3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torlakovic EE, Gomez JD, Driman DK, Parfitt JR, Wang C, et al. Sessile serrated adenoma (SSA) vs. traditional serrated adenoma (TSA) Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:21–29. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318157f002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaeger E, Webb E, Howarth K, Carvajal-Carmona L, Rowan A, et al. Common genetic variants at the CRAC1 (HMPS) locus on chromosome 15q13.3 influence colorectal cancer risk. Nat Genet. 2008;40:26–28. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potti TA, Petty EM, Lesperance MM. A comprehensive review of reported heritable noggin-associated syndromes and proposed clinical utility of one broadly inclusive diagnostic term: NOG-related-symphalangism spectrum disorder (NOG-SSD) Hum Mutat. 2011;32:877–886. doi: 10.1002/humu.21515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomlinson I, Jaeger E, Leedham S, Thomas H. Reply to “The classification of intestinal polyposis”. Nat Genet. 2013;45:2–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Preston SL, Wong WM, Chan AO, Poulsom R, Jeffery R, et al. Bottom-up histogenesis of colorectal adenomas: origin in the monocryptal adenoma and initial expansion by crypt fission. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3819–3825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shih IM, Wang TL, Traverso G, Romans K, Hamilton SR, et al. Top-down morphogenesis of colorectal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2640–2645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051629398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwitalla S, Fingerle AA, Cammareri P, Nebelsiek T, Goktuna SI, et al. Intestinal Tumorigenesis Initiated by Dedifferentiation and Acquisition of Stem-Cell-like Properties. Cell. 2013;152:25–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Online references

- 36.Feinberg AP, Vogelstein B. A technique for radiolabeling DNA restriction endonuclease fragments to high specific activity. Analytical biochemistry. 1983;132:6–13. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(83)90418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moser AR, Dove WF, Roth KA, Gordon JI. The Min (multiple intestinal neoplasia) mutation: its effect on gut epithelial cell differentiation and interaction with a modifier system. The Journal of cell biology. 1992;116:1517–1526. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.6.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gazzerro E, Smerdel-Ramoya A, Zanotti S, Stadmeyer L, Durant D, et al. Conditional deletion of gremlin causes a transient increase in bone formation and bone mass. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:31549–31557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701317200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rudling R, Hassan AB, Kitau J, Mandir N, Goodlad RA. A simple device to rapidly prepare whole mounts of murine intestine. Cell Prolif. 2006;39:415–420. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2006.00391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luongo C, Moser AR, Gledhill S, Dove WF. Loss of Apc+ in intestinal adenomas from Min mice. Cancer research. 1994;54:5947–5952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weisenberger DJ, Campan M, Long TI, Laird PW. Determination of the CpG Island Methylator Phenotype (CIMP) in colorectal cancer using. MethyLight. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.