Abstract

From paired blood and spleen samples from three adult donors we performed high-throughput V-h sequencing of human B-cell subsets defined by IgD and CD27 expression: IgD+CD27+ (“MZ”), IgD−CD27+(“memory”, including IgM (“IgM-only”), IgG and IgA) and IgD−CD27− cells (“double-negative”, including IgM, IgG and IgA). 91,294 unique sequences clustered in 42,670 clones, revealing major clonal expansions in each of these subsets. Among these clones, we further analyzed those shared sequences from different subsets or tissues for Vh-gene mutation, H-CDR3-length, and Vh/Jh usage, comparing these different characteristics with all sequences from their subset of origin, for which these parameters constitute a distinct signature. The IgM-only repertoire profile differed notably from that of MZ B cells by a higher mutation frequency, and lower Vh4 and higher Jh6 gene usage. Strikingly, IgM sequences from clones shared between the MZ and the memory IgG/IgA compartments showed a mutation and repertoire profile of IgM-only and not of MZ B cells. Similarly, all IgM clonal relationships (between MZ, IgM-only, and double-negative compartments) involved sequences with the characteristics of IgM-only B cells. Finally, clonal relationships between tissues suggested distinct recirculation characteristics between MZ and switched B cells. The “IgM-only” subset (including cells with its repertoire signature but higher IgD or lower CD27 expression levels) thus appear as the only subset showing precursor-product relationships with CD27+ switched memory B cells, indicating that they represent germinal center-derived IgM memory B cells, and that IgM memory and MZ B cells constitute two distinct entities.

Introduction

Different B-cell lineages are mobilized in mice during T-dependent and T-independent immune responses. T-dependent responses against protein antigens drive recruitment of naive follicular B cells into germinal centers, where somatic hypermutation and isotype switching allow emergence of expanded IgG+ and IgA+ memory B-cell clones with higher affinity for immunizing antigens. Recent evidence in mice demonstrates the existence of a mutated IgM memory compartment generated in parallel during the germinal center (GC) response (1, 2), even though the precise conditions of its activation in subsequent antigen challenges are still a matter of debate. In contrast, mouse T-independent responses, e.g. those against polysaccharides from encapsulated bacteria, involves marginal zone (MZ) B cells, a distinct splenic subset with limited recirculation capacities that rapidly differentiate into effector plasma cells secreting IgM as well as IgG and IgA antibodies after isotype switching (3).

The murine and human peripheral and splenic B cell compartments differ in many ways. In man, subsets with mutated Ig genes are markedly expanded, accounting for ~40% of B cells. Mutated B cells are identified by the CD27 marker, even though a small CD27− compartment that contains IgM+, IgG+, IgA+ has been identified in blood (4-6). Switched CD27+ B cells are GC-derived and are capable of accumulating a considerable number of mutations, while it was recently proposed that blood IgA+CD27− cells may have a T-independent origin, possibly originating in gut-associated lymphoid tissues (7).

The existence of a human MZ cell lineage is still a topic of debate. Splenic IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells share with mouse MZ B cells a localization at the periphery of B cell follicles and a distinct cell surface phenotype (CD21highCD23−IgMhighIgDlowCD1chigh). However, in contrast to mouse MZ B cells previously described as a splenic resident subset with unmutated B-cell receptors, human IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells harbor mutated IgV genes and recirculate (8). Based on the presence of such cells in CD40L-deficient patients (albeit in reduced numbers) that cannot initiate GC reactions, we proposed that MZ B cells pre-diversify their Ig receptor outside immune responses (9). This proposition was further supported by finding splenic MZ B cell Ig gene diversification in infants, before the development of functional T-independent responses (10).

The presence of Ig V-gene mutations in the IgM+IgD+CD27+ subset however is consistent with another interpretation, i.e., they represent IgM memory B cells that exited GCs prior to isotype switching (11). “IgM-only” CD27+ cells, a minor B-cell subset with very low IgD expression, are similarly categorized (12). The most striking evidence favoring the memory lineage argument is the observation of a large number of clonal relationships between blood IgG+CD27+ and IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells through CDR3-specific PCR amplification (13).

The relative relationship with other B-cell subsets was investigated further by extensive phenotypic and molecular profiling and by high-throughput sequencing of Ig genes (7, 14). In the latter study, clonal relationships were found between blood IgM+IgD+CD27+ and other IgM+ B-cell subsets (IgM-only and IgM+IgD−CD27−), but not with switched CD27+ cells, although large-scale sequencing is less powerful than a CDR3-targeted PCR approach.

We addressed the origin of IgM memory subsets in humans using high-throughput sequencing of paired blood and spleen samples. For each subset, we identified a specific repertoire profile, based on Vh-gene mutation distribution, H-CDR3 size, and Vh and Jh usage. Surprisingly, we found that all clonal relationships between IgM+IgD+CD27+ and switched CD27+ cells, as well as with other IgM+ subsets, involved cells displaying the IgM-only repertoire profile, suggesting that IgM memory cells have a more heterogeneous IgD and CD27 expression level than previously thought. This repertoire profile is distinct from MZ B cells. We also observed that all CD27− subsets (IgM+, IgG+ and IgA+) include different subpopulations having multiple origins.

Methods

Samples

Paired blood and spleen samples were obtained from three organ donors (45, 48 and 54-years-old). All died from cerebral vascular accidents, and blood samples were taken before organ removal. The criteria for inclusion as organ donor include a non-infectious serology, as well as normal blood parameters for standard metabolic markers and cell composition. These individuals can thus reasonably be considered as “healthy donors” at the time of their blood and spleen sampling. This study was authorized by the French Agence Nationale de la Biomédecine.

Cell sorting

PBMCs and splenocytes obtained by Ficoll-Hypaque density centrifugation were stained with the following anti-human antibodies: V500 anti-CD19 (Becton Dickinson), PerCPcy5.5 anti-CD38 (Biolegend), PE-cy7 anti-CD24 (Biolegend), FITC anti-IgD (Invitrogen), APC anti-CD27 (Becton Dickinson). Dead cells were excluded by Sytox Blue staining (Invitrogen). B cells (1,000-20,000) were sorted using a FACSAria (Becton Dickinson) and collected into 30 μl of RT lysis buffer(14).

Vh gene amplification and sequencing

cDNA synthesis and isotype-specific semi-nested PCR amplification was performed as described (14). Purified PCR products were used for high-throughput sequencing on Roche 434 Titanium platform (LGC Genomics). Sequences were processed as reported (14).

Selection of unique sequences and H-CDR3 clustering

Identical sequences are predominantly generated by PCR amplification, and not through contribution of identical mRNA species, since they present an inverse correlation with the initial cell input (not shown). Only unique sequences were used for these analysis. Identical sequences were removed, including those differing only by insertions/deletions, which most probably were generated by the sequencing procedure, and by selecting the in-frame one. Among 152,981 sequences determined, 103,066 unique sequences were obtained.

Sequences from each donor were clustered based on CDR3 nucleotide sequences in order to identify clonally related sequences. CDR3 is defined as the nucleotide region comprised between the invariant Cys residue at the end of all Vh genes and the invariant Trp from all Jh segments. We empirically selected a 16.5% divergence cut-off for the CDR3 clustering algorithm, i.e. allowing for an 8-nucleotide difference over an average CDR3 length of 16 amino acids. We arrived at this value by starting from a higher cut-off (20%), and performing a manual evaluation (described below) of a representative selection of the resulting clones. After subsequent clustering at lower cut-offs (0.5% interval), we selected the lower threshold that maintained the assessed clonal associations. It needs to be emphasized that the stringency of this cut-off depends upon the average mutation frequency of the subset analyzed, and, accordingly, a higher stringency should be used for the analysis of naive B cells (not included in this study). All clusters with sequences belonging to two or more B cell subsets, isotypes and/or tissues were manually aligned and, in the case of false positive associations, were assigned to a new cluster. The criteria used to evaluate the relevance of the clustering included the distribution of divergent positions along the CDR3 sequence (in the V, D and J coding segments vs. at the V-D and D-J junctions) as well as the number of shared mutations in the V gene sequence.

Estimate of clone size and B cell sampling

The size of a clone is the number of cells belonging to that clone, and this can be estimated from the number of sequences attributed to that clone in the sequence dataset, using Bayes’s inversion rule. N represents the total number of cells under consideration (e.g. of a given cell type), and M the subset of these cells that belong to a given clone. Likewise, n represents the total number of sequences within that type, and m the subset of these that belong to the clone of interest. The naive estimate M = N × m / n could be quite inaccurate for very small clones, e.g. clones that have been seen once in the sequence dataset (m = 1). Such clones could be of size of order ~ N / n, but they could also be much smaller. These, out of many similarly small clones, could randomly be assigned to the sequence dataset by chance. To better control what M could be based on our knowledge of m, we use Bayes’s rule: P(M | m) = P(m | M) × P(M) / P(m) = P(M | m) × P(M) / normalization.

If we assume that the sequenced reads are a random subset of the cell receptors, P(M | m) is given by a Poisson distribution: P(M | m) = (1 / M!) × exp(−N × m / n) (N × m / n)^M. P(M), on the other hand, represents our prior information about the distribution of clone sizes. These distributions are typically observed to obey power laws, P(M) ~ M^-nu (here we use nu = 1). The result of Bayes’ procedure is a distribution over the possible values of M, P(M | m), rather than a single number. In the plots depicted in Figure S1B, we represent the median value of that distribution, with error bars showing 95% confidence intervals. The higher m is, the more reliable the estimate of M is, as evidenced by the shrinking error bars as m increases.

We used the lower estimate of the real size of each individual clone in the different subsets to estimate the minimal fraction of the total B cell subset that the sampled clones represent (described in Figure S1 and listed in Table S1).

Statistics

For continuous variables, the unpaired t-test was used and for proportions chi-square test was used; for both, Bonferroni corrections were included. Table S3 lists the results of statistical tests performed for the repertoire analysis reported in Figures 5 and 6. All repertoire characteristics include error bars representing the 95% confidence interval of the distribution.

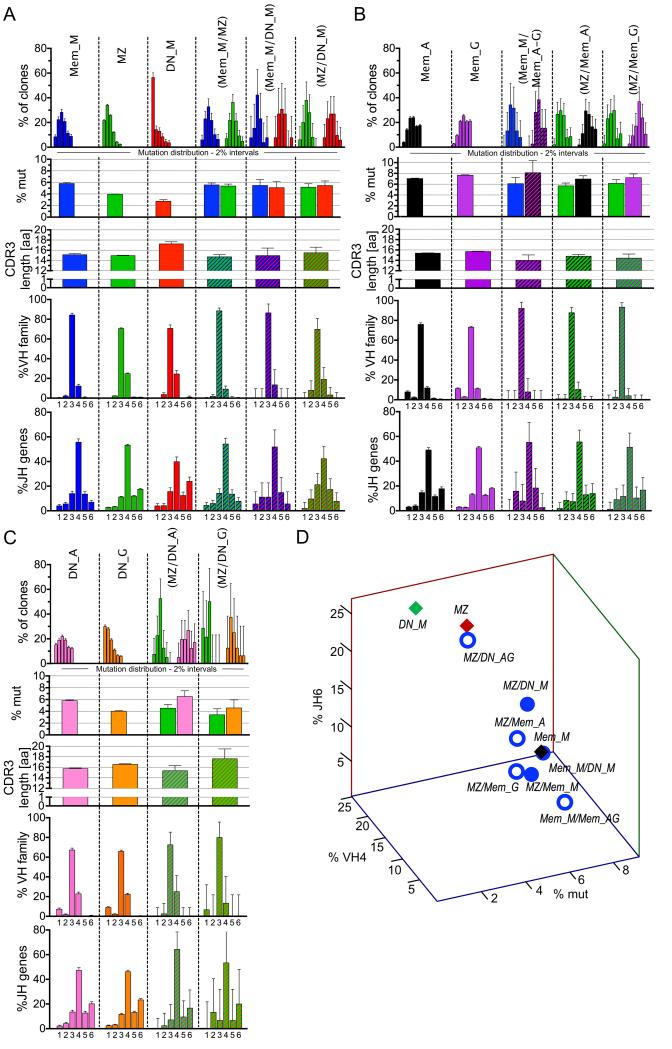

Figure 5. Repertoire profile of clones shared between different subsets.

Analysis of clones shared between the different IgM B cell subsets (A), between IgM memory or MZ and IgG/IgA memory B cells (B), and between MZ and double-negative IgG/IgA B cells (C). . Each column represents a specific B cell population, with its name indicated on top of each panel: B cell subset, CD27+IgD− memory (Mem), CD27+IgD+ marginal zone (MZ) and CD27−IgD− double-negative B cells (DN); immunoglobulin isotype: IgG (G), IgA (A), IgM (M). MZ are IgM+, and only analyzed in (C). Populations indicated in brackets represent the tissue/subset of origin between which the clones analyzed are shared. The repertoire analysis includes 5 rows, with, from the top: i) Vh mutation frequency depicted as fraction of clones within 6 different 2% mutation intervals, from 0-2% (left) to >10% mutation frequency (far right); ii) average Vh mutation frequency; iii) average H-CDR3 amino acid length; iv) Vh family 1 to 6 usage v) Jh 1 to 6 usage. The mutation data for shared clones (first and second row) is plotted separately for the sequences belonging to each of the two populations involved, because, contrary to other parameters, Vh mutations can vary between B cells belonging to the same clone. All analyses are based on clones, not sequences, and take into account, for mutation frequencies, the average mutation frequency of the clone. (D) 3-D plot representation according to mutation frequency, Vh4 and Jh6 usage of clones shared between two IgM-positive subsets (filled blue dots), or between MZ or Mem_M and Mem_A/Mem-G or DN_A/DN_G (open blue dots). In the latter case, data concerning MZ clones shared with DN_A and DN_G subsets were pooled. Parental IgM subsets are represented by diamonds, red for MZ, green for DN_M and black for Mem_M. Statistics are depicted in Table S3 to facilitate reading, with the different pair wise comparisons indicated. Error bars represent the 95% interval of confidence of data distribution and therefore directly reflect the size of the sample analyzed.

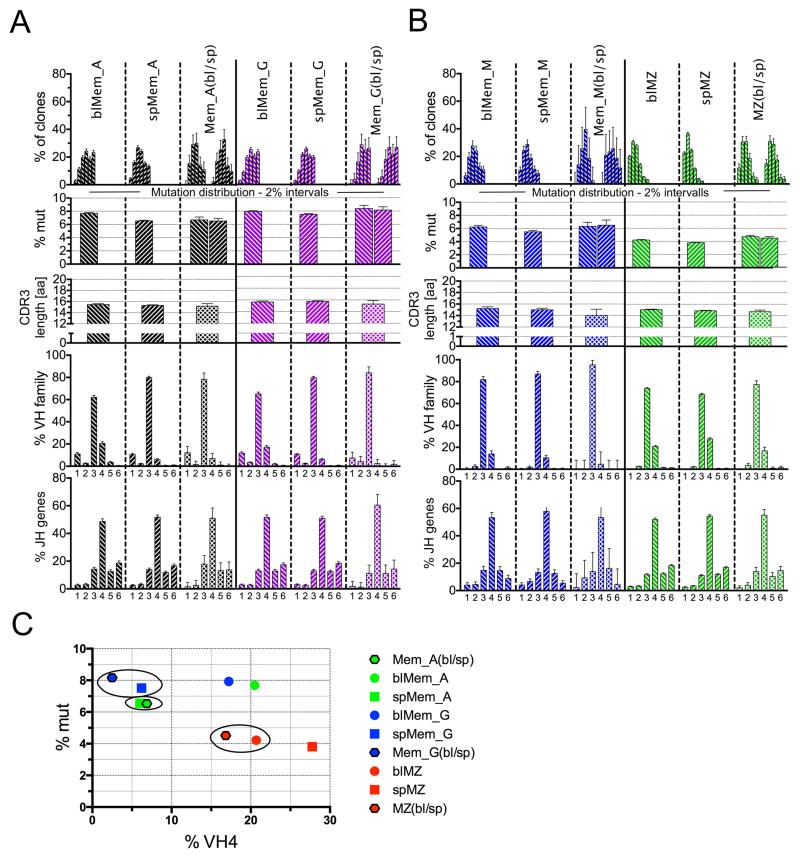

Figure 6. Repertoire profile of clones shared between blood and spleen.

Analysis of clones shared between blood and spleen for IgG and IgA (A), and IgM subsets (B). Abbreviations and criteria of repertoire analysis are depicted in legend to Figure 5 with the addition of tissue: blood (bl) and spleen (sp). (C) 2D plot representation according to mutation frequency and Vh4 usage of the clones shared between blood and spleen for Mem_G (blue), Mem_A (green) and MZ (red) B cells, together with the profile of the parental blood and spleen subsets. Spleen sequences are represented by squares, blood sequences by dots, and sequences shared between blood and spleen by a hexagon framed in black. Circles mark the closest parental subset of the clones shared between both tissues.

Results

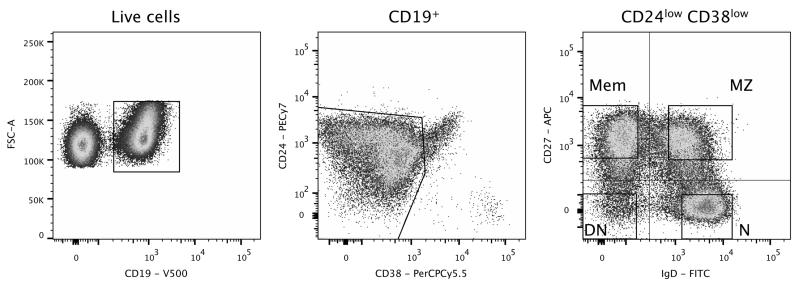

We used paired blood and spleen samples from three adult organ donors, who, to the best of our knowledge, did not present any overt pathology. We isolated three different CD19+ B-cell populations according to surface CD27 and IgD expression: marginal zone (MZ; CD27+IgD+), classical memory (Mem; CD27+IgD−) and double negative (DN; CD27−IgD−) B cells. Surface expression of CD38 and CD24 was used to exclude transitional, GC, and plasma cells from the sorted populations (Figure 1). Using isotype-specific heavy chain primers, IgM sequences were amplified from MZ B cells, while IgM, IgG, and IgA isotypes were amplified from both memory and double-negative cells (Mem_M, Mem_G, Mem_A, and DN_M, DN_G and DN_A, respectively). After eliminating 49,975 duplicates, we obtained 91,294 unique IgH sequences from the three donors. These fell into 42,670 clonotypes after H-CDR3 clustering (Table S2).

Figure 1. Isolation of naive, marginal zone, memory and double-negative B cell subsets.

Human peripheral blood and splenic CD19+ B cells were stained with CD38 and CD24 to exclude transitional, germinal center, and plasma cells. The four gated populations were sorted according to CD27 and IgD expression: CD27+IgD− memory cells (Mem), CD27+IgD+ marginal zone B cells (MZ), CD27−IgD+ naive (N) and CD27−IgD− double-negative (DN) B cells. The profile shown corresponds to a spleen sample.

We also isolated IgM sequences from naive B cells (N; CD27−IgD+) to estimate background mutations and for H-CDR3 length comparisons.

H-CDR3 clustering

The H-CDR3 clustering algorithm has to be sufficiently stringent to minimize the number of false clusters, but flexible enough to not exclude sequences that differ due to somatic mutations or sequencing errors. Therefore, we empirically determined a threshold for inclusion of 16.5% sequence divergence and then systematically performed a manual screening of all clusters containing sequences from different populations, isotypes, and/or tissues (see Materials and Methods).

In order to estimate the errors (false clusters) generated by this algorithm, we ran the clustering algorithm on spleen sequences pooled from two different donors and performed a manual screening of the clusters containing sequences from both donors with the same selection criteria. False clustering can be influenced by the average mutation frequency and the number of sequences analyzed. The occurrence of false clusters varied for the different subsets, representing 2.4% for MZ and 0.1% for memory B cells; no shared clones were detected for DN B cells between donors. The fraction of clusters judged as real after manual screening among total clones was 0.6%, and this therefore represents the probability of having unrelated sequences clustering by chance, i.e. similar heavy chain rearrangements occurring in non clonally-related B cells.

Sampling and estimate of clone sizes and clonal diversity

The adult lymphoid compartment comprises approximately 10×109 cells (5-25×109) in blood and 75×109 cells (70-80×109) in spleen (15). Taking into account the B cell percentage observed in the lymphoid gate by flow cytometry, the B cell pool was estimated to 10, 23 and 24×108 B cells in blood and 25, 55, and 43×109 B cells in spleen, for the three donors, respectively. We similarly estimated B-cell numbers for each subset from flow cytometry data for each donor, which, in combination with the number of unique sequences obtained for each B-cell population, allowed us to evaluate the extent of our sampling as a fraction of total B cells per subset (Table S1). We collected roughly the same number of sequences for blood and spleen. Since blood is a 20 to 30-fold smaller reservoir for B cells, we achieved better sampling for the blood (10−4-10−5) than for the spleen (10−5-10−6), even though these values are low in both cases (Table S1).

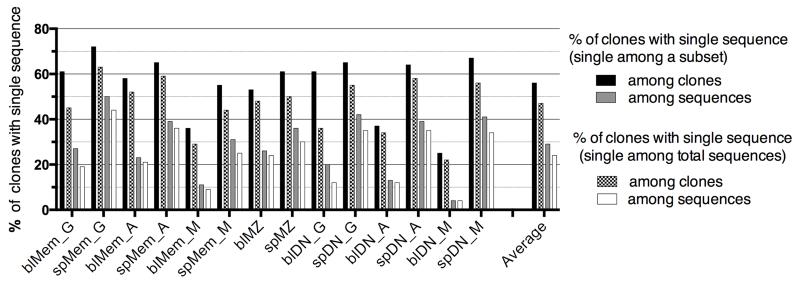

Observing clonally related sequences clearly indicates the presence of expanded clones. Clones defined by only one sequence represented 56% on average of the clones of a given subset (with large variation, see Figure 2) but, in terms of sequences, only 29% of the sequences of this subset. This proportion is further reduced if the total pool of sequences obtained for one individual is taken into account for defining clones with one sequence, and represents then 47% of the clones and 24% of the sequences on average for each subset (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Fraction of clones with single sequences among each subset.

Fraction of clones with single sequences among each subset, reported either to the total number of clones or the total number of sequences of this subset. Two different calculations are performed, depending whether clones have single sequence at the level of a given subset (first two bars), or at the level of the total sequence pool of the donor (last two bars).

Using Bayes’s rule and Poisson statistics, we extrapolated an estimated size of each sampled clone in each subset-tissue combination (see Material and Methods), an extrapolation whose precision increases with the number of clonally related sequences. From this, we estimated the minimum fraction of the entire B-cell subset that all sampled clones represent in vivo (Table S1 and Figure S1 for the calculation procedure). Thus, despite small B-cell sampling, sampled clones represent an average of at least 15% of the B cells in vivo in a given subset (Table S1). For all subsets, B-cell clones are larger in spleen compared to blood, consistent with the relative size of their B lymphocyte compartment (Figure S1 and data not shown).

Clonal relationships between subsets and tissues

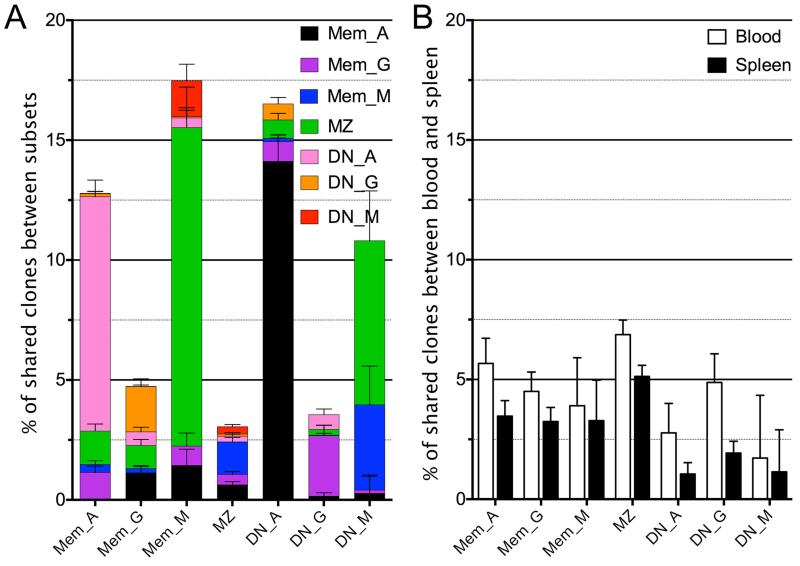

Through H-CDR3 clustering, we found clones that were present in different B-cell populations, isotypes, and tissues. Clustering of all sequences was first performed for each donor separately, and then clones falling within the same category (e.g. clones present in blood and spleen MZ subsets) were pooled for the three donors to obtain weighted averages in frequency estimates. The total numbers of shared clones is listed in Table S2 and the fraction they represent, related to the total number of clones in the subset/tissue, is depicted in Figure 3. The fraction of shared clones observed between two given subsets depends on the sampling size, the in vivo clone size distribution, and the total B-cell numbers comprising each subset, making the observed fraction of shared clones not readily comparable. Nevertheless, this fraction represents a minimal estimate of the clonal relationships existing in vivo. A high frequency of clonally related sequences is observed between the Mem_A and the DN_A subset, and amounts to 9.5% of Mem_A and 12.5% of DN_A clones (Figure 3A). Clones shared with MZ B cells also represent a large part of the Mem_M and DN_M subsets. In contrast, even though MZ B cells represent the largest sequence set, they display the lowest frequency of clonal relationships with other subsets. All subsets studied presented clones shared between blood and spleen, the highest frequency being observed for MZ B cells (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Clonal relationships between subsets and tissues.

(A) Percentage of clones shared between B cell subsets, analyzed for each individual subset and color-coded for the subset sharing these clones. (B) Percentage of clones showing clonal relationships between blood and spleen for the same subset among blood cells (white) and spleen cells (black). The error bars represent the binomial proportion confidence interval (95%). Clonal relationships were analyzed for each donor separately, and the total number of clones belonging to the same category (e.g. clones shared between blood and spleen Mem_A subsets) were pooled from the three donors and reported to the total number of clones obtained in the corresponding subset for the three samples (e.g., total clones from blood Mem_A or spleen Mem_A subsets, first two columns, panel B).

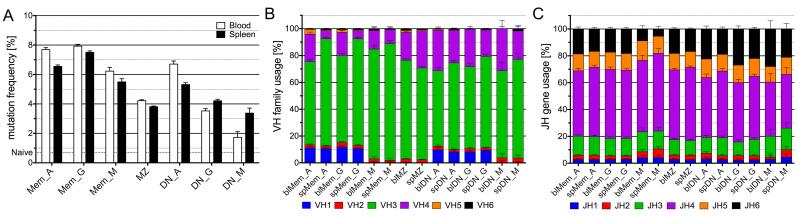

The different B-cell subsets can be characterized by mutation frequency and distribution, H-CDR3-length, and usage of Vh family and Jh genes. We found that blood subsets tended to carry more mutations than splenic ones (apart from DN_M, discussed below) and mutation frequencies varied based on individual subsets and isotypes (Figure 4A). With respect to Vh gene family usage, the Vh1 family was rarely used by the various IgM-positive subsets, and the frequency of Vh4 family gene usage appeared to be the most consistent discriminating feature (Figure 4B). It should be noted that Vh family distribution might be biased due to the amplification reaction, i.e. the frequency of Vh1 usage is less than in previous reports (14). Thus we do not consider our result as an absolute estimate of the Vh family repertoire, although it does serve as a valid tool to compare within B-cell subsets as each was subjected to the same Vh amplification protocol. For Jh usage, Jh6 (the Jh segment with the longest sequence contribution to H-CDR3) was the most variable (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Vh mutation frequencies, Vh family and Jh gene usage of the different B-cell subsets.

(A) Vh mutation frequencies were estimated by comparison with the IMGT database. Mutation frequencies are calculated based on the average mutation value obtained for each clone. The mutation frequency observed for the naive B cell pool (0.7 %) is represented by a dotted line, and is taken as an estimate of the contribution of sequencing errors. Vh family (B) and Jh gene (C) usage.

Out of 42,670 clones, 1,629 clones contained sequences from blood and spleen for the same B-cell subset and 1,681 contained sequences from different subsets, allowing us to trace their relationships. We therefore analyzed these different repertoire parameters in clones sharing sequences from different B-cell populations, comparing their profiles with those of their subset of origin. For mutation frequency, the only parameter that can differ between sequences within a single clone, we analyzed sequences from each subset within a clone separately (see legend to Figure 5). In Figure 5 and 6, V gene mutations are represented both by mutation distribution (with 6 different 2% mutation intervals from 0-2% to >10%) and by the average mutation frequency. The statistical relevance of the comparisons depicted in these figures is listed in Supplementary Table 3.

Clonal relationships between different B-cell subsets

IgM subsets: MZ, IgM-only (Mem_M), and double-negative (DN_M)

The three IgM-positive subsets (Mem_M, MZ, and DN_M) differed from each other for all four parameters. Mutation frequency decreased from Mem_M, to MZ, and then to DN_M, a difference most noticeable in the mutation distribution plot by the marked different proportion of sequences in the 0-2% mutation range (Figure 5A, first row). MZ and DN_M clones differed from Mem_M based on greater Vh4 and Jh6 usage (Figure 5A, 4th and 5th rows). DN_M differed from the other two due to its longer average H-CDR3 length (Figure 5A, 3rd row).

Analyses of clonal relationships between IgM subsets showed that clones shared between each two-population combination (MZ/Mem_M, MZ/DN_M and Mem_M/DN_M) exhibited mutation distribution, Vh and Jh profiles similar to the Mem_M, even for MZ/DN_M where Mem_M was not part of the comparison (Figure 5A). Accordingly, clones shared between MZ and Mem_M diverged from the MZ subset with respect to these three parameters; shared Mem_M/DN_M clones differed from DN_M with respect to mutation frequency and Jh usage; shared MZ/DN_M clones deviated from MZ and DN_M based on mutation frequency and Jh usage.

A 3D-analysis of these different subsets based on mutation frequency and Vh4 and Jh6 usage is presented in Figure 5D. This illustrates the closer proximity of all clones shared between two IgM-positive subsets with Mem_M B cells, than with MZ or DN_M B cells. All IgM shared clones thus appeared to display a homogenous profile, similar to the Mem_M subset, regardless of the isolated B-cell population from which these sequences originated.

MZ/IgM-only and IgG/IgA memory subsets

Examination of clonal relationships between MZ and switched memory subsets (MZ/Mem_G and MZ/Mem_A) indicated that shared clones displayed a Mem_M profile for Vh and Jh usage, as well as for mutation (for the IgM sequences) (Figure 7B). Accordingly, shared clones diverged from MZ for mutations and Vh repertoire. The switched sequences of the shared clones had a higher mutation frequency than the IgM ones, each matching the corresponding switched subset.

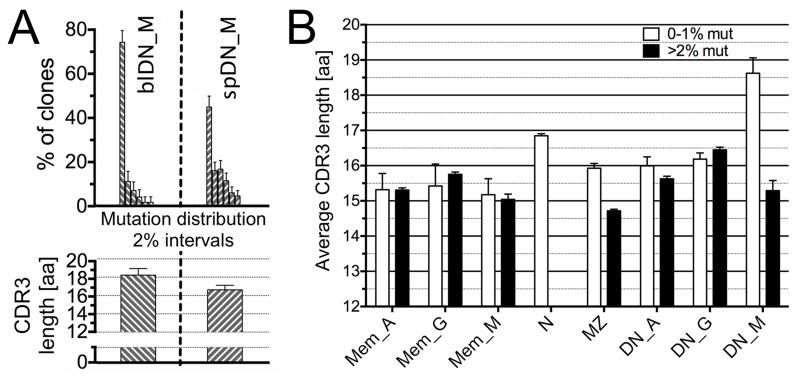

Figure 7. Mutation frequency of DN_M subsets and average H-CDR3 amino acid length in mutated and unmutated splenic clones.

A) Vh mutation frequency depicted as fraction of clones within 6 different 2% mutation intervals, from 0-2% to >10% mutation frequency (first row); average CDR3 amino acid (a.a.) length (second row) of blood (bl) and spleen (sp) DN_M subsets. B) Average H-CDR3 length of each splenic B-cell subset, represented according to their mutation frequency (white bars: less than 1% mutation; black bars: more than 2% mutation). Error bars represent the 95% interval of confidence.

The clonal relationship between IgM and switched memory subsets was analyzed by combining IgG and IgA clones (38 clones in total). Shared clones (Mem_M/Mem_A-G) presented an IgM-only profile for Vh and Jh usage, with mutation frequency corresponding to the parent isotype-matching subset.

These data suggest that clones shared between the MZ and switched memory subsets present a repertoire profile similar to Mem_M/Mem_A-G shared clones and represent IgM-only B cells that underwent class switching with accumulation of additional mutations. Accordingly, these clones segregated close to the Mem_M subset in the 3D plot (Fig. 5D).

MZ and DN_G/DN_A subsets

Finally, defining clonal relationships between MZ and switched DN subsets revealed that shared clones (MZ/DN_G and MZ/DN_A) exhibit a MZ profile for Vh and Jh usage, and, for IgM sequences within these clones, for mutation frequency (Figure 5C), although the data are limited in amount (MZ/DN_G: 16 clones, MZ/DN_A: 41 clones). Accordingly, both MZ/DN_G and MZ/DN_A shared clones differed from Mem_M for mutation, and MZ/DN_A also differed from Mem_M for Vh repertoire (other parameters were not statistically significant). Switched sequences within shared clones had a mutation frequency corresponding to the isotype-matching DN cells. MZ/DN_G shared clones had H-CDR3 lengths similar to the DN parental subset, while differing from both MZ and Mem_M. MZ clones shared with DN_A and DN_G sequences were the only ones segregating close to the MZ subset in the 3-D plot (Figure 5D).

These data suggest that a small fraction of MZ B cells undergoes isotype switching and persists in the DN population. MZ B cell switching to IgG DN cells appears biased for clones bearing longer H-CDR3 than the bulk MZ B cell population.

Clonal relationships between blood and spleen subsets

Memory B cells

Switched memory B cells differed between blood and spleen mainly by Vh4 usage, which was lower in spleen (Figure 6A and B, 4th row), and, for Mem_A, for mutation frequency, which was higher in blood (Figure 6A, 1st and 2nd rows).

Clones shared between blood and spleen in the switched memory IgG and IgA subpopulations displayed low Vh4 usage and mutation frequency for IgA, typical of the spleen (Figure 6A and B). Thus, it appeared that switched memory cells in the spleen recirculate in an unbiased manner, at least based on Vh repertoire, whereas the blood counterparts comprised a mixture of splenic and other lymphoid tissue-derived memory B cells with different Vh repertoires, contributing to its higher Vh4 usage. Moreover, for IgA but not for IgG, the total blood contained clones had significantly more mutations than the ones shared with spleen, indicating that clones from other lymphoid tissues contributing to the blood repertoire carried Igs with higher mutation loads. The IgM-only memory subset displayed minor differences between tissues; thus analysis of the 43 shared clones was not informative (Figure 6C).

The closer proximity of clones shared between blood and spleen to the spleen compartment for switched memory B cells is illustrated on a 2D-plot of mutation frequency and Vh4 usage (Figure 6C).

Marginal zone B cells

MZ B cells in blood and spleen exhibited a Vh profile opposite to that of the other subsets, with a lower Vh4 usage in the blood. MZ B cells clones shared between blood and spleen displayed a Vh profile closer to the blood (low Vh4) and significantly different from spleen (Figure 6C), suggesting that splenic MZ B cells have a biased recirculation, consisting of those with a lower Vh4 representation. Accordingly, clones shared between blood and spleen segregated closer to the blood subset in the 2D representation (Figure 6C). Thus, the blood MZ B cell population appeared to be composed of a subset of splenic MZ B cells, suggesting that not all splenic MZ B cells recirculate equally.

DN subsets

The switched DN subsets presented the same differences between blood and spleen as their CD27+ counterpart: higher Vh4 usage (and mutation frequency for DN_A) in blood. Similarly, shared clones for the double-negative IgG subset showed the same Vh repertoire bias towards the splenic repertoire observed for memory IgG; the shared DN_A clones had in addition the same mutation bias observed for memory IgA, the only two parameters for which differences in the comparison with the two parent tissues reached statistical significance (not shown). This suggests that switched cells show similar recirculation dynamics for both CD27+ and CD27−, with blood subsets containing both recirculating splenic cells and cells from other tissues.

DN IgM cells did not present a sufficient number of shared clones to perform such analysis. Nevertheless, blood and spleen subsets present consistent differences, notably in mutation distribution and H-CDR3 length (Figure 7A). In spleen, almost half of the clones displayed unmutated Vh genes with H-CDR3s longer than naive B cells (18.6 vs. 16.8 amino acids) (Figure 7B). In contrast, the mutated fraction carries H-CDR3s with a length comparable to the other mutated subsets. Segregation of these two parameters suggested that the DN_M subset included B cells having at least two different origins, and that part of the mutated DN_M sequences corresponds to IgM-only B cells down-modulating surface CD27. The blood DN IgM subset was composed mainly of clones with low mutation (only twice the background of naive B cells) and long H-CDR3 (Figure 4 and 5C), suggesting a different recirculation of mutated and unmutated subsets, or a down-modulation of the CD27 marker taking place upon splenic location or trafficking of IgM-only B cells.

Discussion

We performed high-throughput Ig VhDJh sequencing of human B-cell subsets from paired blood and spleen samples, to investigate clonal relationships between MZ B cells and other memory subsets, as well as the recirculation dynamics of different B cell subsets between blood and spleen.

Sequences from seven different B-cell populations were collected from these two compartments, based on cell sorting according to expression of surface IgD and CD27 (after excluding GCs or plasma cells) and on isotype-specific PCR amplification: MZ B cells (IgD+CD27+, IgM+), memory B cells (IgD−CD27+, IgG+, IgA+ and IgM+, i.e. “IgM-only”) and “double-negative” cells (IgD−CD27−, IgM, IgG and IgA). This latter subset, albeit CD27−, was previously shown by several groups to include B cells with mutated Ig genes (4, 5).

Even though we collected and analyzed several thousand unique Vh sequences, they still only represent a small sample of the total B-cell pool, which is estimated to be ~10−5 for blood B-cell subsets and ~10−6 for splenic ones. Surprisingly, in spite of this low sampling, a large number of non-identical sequences were clonally related (91,294 sequences segregating into 42,670 clones). As mentioned in similar studies (6), isolation of clonally related Vh sequences indicates that B-cell clones have undergone major clonal expansion, with estimated average clone sizes of ~105 cells for blood and 106 for spleen. Clones having more than one sequence within a subset represented 40-50% of the total number of clones obtained, i.e. ~70% of the total sequences. Moreover, an average of 16% of clones composed by a single sequence within a subset appeared to have a clonal relative in another subset or tissue of the same individual, suggesting that expanded clones represent a major fraction of each B-cell subset, and not a minor one.

Interestingly, after extrapolating to the in vivo size of the B-cell clones, we calculated that the sampled clones represented at least 15% of the total B cells in the compartment, in striking contrast with the 10−5-10−6 sampling performed. Estimating the global repertoire diversity of these different subsets was not within the scope of this study, as it would require sequencing of multiple samples of the same B-cell population to estimate if expanded clones are distributed along a normal distribution of sizes, a likely possibility for classical memory subsets, or distributed bi- or multi-modally, thus corresponding to a much larger repertoire diversity.

The focus of this study was the investigation of clonal relationships between subsets and tissues. We used an “intermediate” high throughput approach that generated tens of thousands, but not hundreds of thousands of sequences, allowing a relatively easy manual assessment of clones obtained through the clustering program, a critical point for their validity and for the relevance of the conclusions obtained. The number of sequences collected was nevertheless sufficiently large to define a robust repertoire signature for each individual subset and for most combinations of shared clones between two given populations. This subset-specific signature was based on mutation frequency and distribution, Vh repertoire (Vh4 gene family usage that appears to be the most discriminating parameter), Jh repertoire (notably Jh6 usage) and H-CDR3 length.

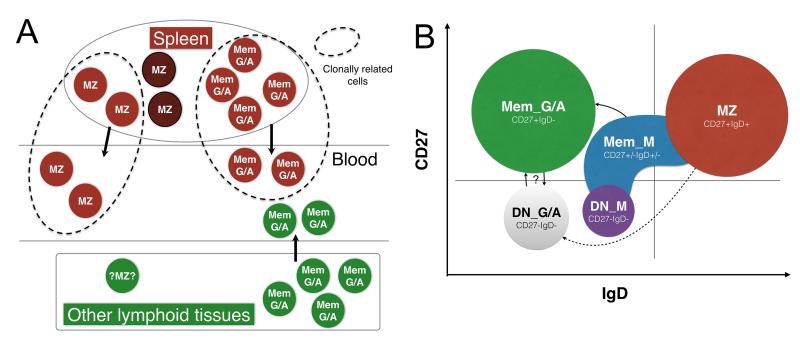

One-hundred-seventy-seven MZ clones among 16,824 analyzed had clonal relationships with switched IgG or IgA memory subsets. Strikingly, the overall mutation frequency and Vh gene profile of these IgM sequences differed from MZ B cells, while precisely matching characteristics of IgM-only B cells, clearly showing a mutation level intermediate between MZ and switched memory B cells and a lower Vh4 usage. Clones shared between switched memory and IgM-only B cells also harbored this IgM-only repertoire profile. Similarly, all IgM sequences presenting clonal relationships between subsets (MZ with IgM-only, IgM-only with DN IgM, or even DN IgM with MZ), displayed the unique repertoire profile of IgM-only B cells. These results suggest that IgM memory B cells with IgM-only repertoire characteristics are in fact more heterogeneous than previously estimated for IgD and CD27 expression, and therefore fall in the MZ and DN sorting gates (schematized in Figure 8A).

Figure 8. Recirculation of spleen MZ and switched memory subsets and clonal relationships between B cell subsets.

A. Recirculation between blood and spleen is schematized for MZ and switched memory B cell subsets, as deduced from the repertoire characteristics of clones shared between both tissues (within dotted lines). Brown circles represent splenic and spleen-derived cells, and green circles cells from other lymphoid tissues. B. Clonal relationships between subsets. Each subset is represented with a different color, distributed over a theoretical FACS profile for IgD and CD27 expression. Clonal relationships with switched memory B cells are observed for IgM memory B cells, which present the repertoire profile of IgM-only B cells (IgD−CD27+) while extending within the MZ and DN gate. MZ B cells only present a few clonal relationships with DN IgG+ and IgA+ cells. The switched memory and DN pool have many clones in common, which could correspond either to precursor-product relationships or reversible up- and down-modulation of CD27 expression. Subsets are not drawn on scale, since IgM memory B cells represent on average 2-4% of the total B cell pool, switched memory 20% and double-negative IgM less than 1%.

Clonal relationships between tissues further distinguished MZ from switched B cells. In effect, switched memory B cell clones shared between blood and spleen had the spleen repertoire profile of the corresponding memory subset, suggesting, possibly not unexpectedly, that B cells from multiple lymphoid compartments and harboring a different repertoire profile contribute to the memory recirculating pool. For IgA memory B cells, clones contributed by other lymphoid tissues carry Ig with a higher mutation load, which would be consistent with a possible mucosal origin, a tissue in which IgA+ B cells display the highest mutation frequency (16). Recirculating MZ clones had a signature significantly closer to the blood subset, suggesting, in contrast, that recirculation concerns a subset of splenic MZ B cells with a distinct repertoire (Figure 8B). Our data support the notion that the spleen is the major reservoir for blood IgM+IgD+CD27+ B cells, in agreement with the observed impact of splenectomy on this recirculating subset (8, 17). However, a minor contribution of other lymphoid tissues cannot be excluded (18), but, if existing, it would concern cells with a repertoire similar to recirculating splenic MZ cells, contrary to memory B cells.

While MZ B cells do not appear affiliated with the switched CD27+ subset, a few clonal relationships involving MZ B cells with an MZ-like mutation profile were observed with CD27− switched cells, a minor subset showing age-related accumulation (19). Interestingly, the clones shared with DN IgG+ cells have longer H-CDR3s compared to the MZ subset, indicating that switching and maintenance within the DN pool might involve MZ B cells with distinct specificities. This was not the case for IgA, for which H-CDR3 sizes were in the normal range.

Double-negative memory subsets thus appear to have multiple origins, comprising at least MZ and CD27+ memory related B cells. CD27−IgA+ cells indeed have a large fraction of clonally related sequences, which are for their major part shared with CD27+IgA+ cells. Whether such relations represent precursor-product relationships or a reversible modulation of surface CD27 remains to be established. CD27−IgG+ cells have similar, albeit less numerous clonal relationships with their CD27+ counterparts. The most drastic heterogeneity concerns DN IgM cells that can be split into cells with an IgM-only profile or cells with low mutation frequency and H-CDR3 sizes larger than naive B cells. Their presence in the DN pool likely corresponds to a repertoire selection bias, possibly redirecting cells with autoimmune potential into this CD27− fraction. Whether specific activation conditions could salvage DN IgM+ B cells with such unusual H-CDR3 lengths and mobilize them into the memory effector pool is obviously an important issue, since such long H-CDR3s are notably the hallmark of autoreactive immunoglobulins (20) and broadly neutralizing anti-HIV antibodies (21).

Post-germinal center IgM memory B cells have been documented in mouse, and appear to represent a population numerically equivalent to switched ones (1, 22). The issue of their existence, number, and function in humans is however more confused. Several reports documented the presence of IgM memory B cells in specific responses, notably in allo-immunized individuals following blood transfusions, but their surface phenotype, IgD+ or not, has not been addressed (23). IgM-only B cells are found in AID-deficient patients, who lack switched B cells but have active GC reactions (8, 24). This observation suggested that IgD down-modulation taking place during the GC reaction might be conserved in germinal center-derived cells that did not isotype switch. However, this observation did not preclude a heterogeneous IgD expression profile. IgM memory B cells, assessed as IgM-only cells, appear in most cases as a minor subset in humans (2-3%), while switched memory averages 20% (8). We estimated, based on their distinct mutation profiles, that they may represent up to 15% of MZ clones: these figures would indicate that IgM memory B cells may in fact be broadly distributed over the IgD+ and IgD−CD27+ B cell gates.

In conclusion, the “IgM-only” subset (including cells with its repertoire signature but higher IgD or lower CD27 expression levels) appears as the only subset showing precursor-product relationships with CD27+ switched memory B cells, indicating that they represent germinal center-derived IgM memory B cells. MZ B cells, in contrast, only present a few clones in common with CD27− IgG and IgA cells, involving, in the former case, MZ B cells with a distinct repertoire. Uncovering new surface markers that may allow the unambiguous identification of the MZ and IgM memory compartments will be key towards studying the conditions of their mobilization and better delineating their respective contributions to T-dependent and T-independent immune responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The team “Développement du système immunitaire”, INSERM U1151 is supported by the Ligue Nationale contre le Cancer (“Equipe labelisée”), the Fondation Princesse Grace and by an ERC advanced investigator grant (Memo-B). The King’s College London team is supported by the MRC, BBSRC, Human Frontiers Science program and the Dunhill Medical Trust. The authors are indebted to Nick Chiorazzi for a thorough editing of the manuscript.

Abbreviations used in this article

- Mem

memory

- MZ

marginal zone

- N

naive

- DN

double-negative

References

- 1.Dogan I, Bertocci B, Vilmont V, Delbos F, Megret J, Storck S, Reynaud CA, Weill JC. Multiple layers of B cell memory with different effector functions. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1292–1299. doi: 10.1038/ni.1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pape KA, Taylor JJ, Maul RW, Gearhart PJ, Jenkins MK. Different B cell populations mediate early and late memory during an endogenous immune response. Science. 2011;331:1203–1207. doi: 10.1126/science.1201730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balazs M, Martin F, Zhou T, Kearney J. Blood dendritic cells interact with splenic marginal zone B cells to initiate T-independent immune responses. Immunity. 2002;17:341–352. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00389-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wirths S, Lanzavecchia A. ABCB1 transporter discriminates human resting naive B cells from cycling transitional and memory B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:3433–3441. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fecteau JF, G Cote,, Neron S. A new memory CD27-IgG+ B cell population in peripheral blood expressing VH genes with low frequency of somatic mutation. J Immunol. 2006;177:3728–3736. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu YC, Kipling D, Dunn-Walters DK. The relationship between CD27 negative and positive B cell populations in human peripheral blood. Front Immunol. 2011;2:81. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2011.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berkowska MA, Driessen GJ, Bikos V, Grosserichter-Wagener C, Stamatopoulos K, Cerutti A, He B, Biermann K, Lange JF, van der Burg M, van Dongen JJ, van Zelm MC. Human memory B cells originate from three distinct germinal center-dependent and -independent maturation pathways. Blood. 2011;118:2150–2158. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-345579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weill JC, Weller S, Reynaud CA. Human marginal zone B cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:267–285. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weller S, Faili A, Garcia C, Braun MC, Le Deist FF, de Saint Basile GG, Hermine O, Fischer A, Reynaud CA, Weill JC. CD40-CD40L independent Ig gene hypermutation suggests a second B cell diversification pathway in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1166–1170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weller S, Mamani-Matsuda M, Picard C, Cordier C, Lecoeuche D, Gauthier F, Weill JC, Reynaud CA. Somatic diversification in the absence of antigen-driven responses is the hallmark of the IgM+ IgD+ CD27+ B cell repertoire in infants. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1331–1342. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tangye SG, Good KL. Human IgM+CD27+ B cells: memory B cells or “memory” B cells? J Immunol. 2007;179:13–19. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seifert M, Przekopowitz M, Taudien S, Lollies A, Ronge V, Drees B, Lindemann M, Hillen U, Engler H, Singer BB, Kuppers R. Functional capacities of human IgM memory B cells in early inflammatory responses and secondary germinal center reactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1416276112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seifert M, Kuppers R. Molecular footprints of a germinal center derivation of human IgM+(IgD+)CD27+ B cells and the dynamics of memory B cell generation. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2659–2669. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu YC, D Kipling,, Leong HS, Martin V, Ademokun AA, Dunn-Walters DK. High-throughput immunoglobulin repertoire analysis distinguishes between human IgM memory and switched memory B-cell populations. Blood. 2010;116:1070–1078. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Westermann J, Pabst R. Distribution of lymphocyte subsets and natural killer cells in the human body. Clin Investig. 1992;70:539–544. doi: 10.1007/BF00184787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn-Walters DK, Hackett M, Boursier L, Ciclitira PJ, Morgan P, Challacombe SJ, Spencer J. Characteristics of human IgA and IgM genes used by plasma cells in the salivary gland resemble those used in duodenum but not those used in the spleen. J Immunol. 2000;164:1595–1601. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cameron PU, Jones P, Gorniak M, Dunster K, Paul E, Lewin S, Woolley I, Spelman D. Splenectomy associated changes in IgM memory B cells in an adult spleen registry cohort. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dono M, Zupo S, Leanza N, Melioli G, Fogli M, Melagrana A, Chiorazzi N, Ferrarini M. Heterogeneity of tonsillar subepithelial B lymphocytes, the splenic marginal zone equivalents. J Immunol. 2000;164:5596–5604. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bulati M, Buffa S, Candore G, Caruso C, Dunn-Walters DK, Pellicano M, Wu YC, Colonna Romano G. B cells and immunosenescence: a focus on IgG+IgD-CD27- (DN) B cells in aged humans. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10:274–284. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wardemann H, Yurasov S, Schaefer A, Young JW, Meffre E, Nussenzweig MC. Predominant autoantibody production by early human B cell precursors. Science. 2003;301:1374–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1086907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwong PD, Mascola JR. Human antibodies that neutralize HIV-1: identification, structures, and B cell ontogenies. Immunity. 2012;37:412–425. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor JJ, Pape KA, Jenkins MK. A germinal center-independent pathway generates unswitched memory B cells early in the primary response. J Exp Med. 2012;209:597–606. doi: 10.1084/jem.20111696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Della Valle L, Dohmen SE, Verhagen OJ, Berkowska MA, Vidarsson G, Ellen van der Schoot C. The majority of human memory B cells recognizing RhD and tetanus resides in IgM+ B cells. J Immunol. 2014;193:1071–1079. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weller S, Braun MC, Tan BK, Rosenwald A, Cordier C, Conley ME, Plebani A, Kumararatne DS, Bonnet D, Tournilhac O, Tchernia G, Steiniger B, Staudt LM, Casanova JL, Reynaud CA, Weill JC. Human blood IgM “memory” B cells are circulating splenic marginal zone B cells harboring a prediversified immunoglobulin repertoire. Blood. 2004;104:3647–3654. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.