ABSTRACT

Purpose: People living in rural and remote regions need support to overcome difficulties in accessing health care. The objectives of the study were (1) to compare demographic characteristics, professional engagement indicators, and clinical characteristics between physiotherapists practising in rural settings and those practising in urban settings and (2) to map the distribution of physiotherapists in Saskatchewan. Method: This cross-sectional study used de-identified data collected from the 2013 Saskatchewan College of Physical Therapists membership renewal (n=643), linked with the Saskatchewan Physiotherapy Association's (SPA) 2012 membership list and a list of physiotherapists who had served as clinical instructors. Employment location (rural vs. urban) was determined by postal code. Results: Only 11.2% of Saskatchewan physiotherapists listed a rural primary employment location, and a higher density of physiotherapists per 10,000 people work in health regions with large urban centres. Compared with urban physiotherapists, rural physiotherapists are more likely to provide direct patient care, to provide care to people of all ages, and to have a mixed client level, and they are less likely to be SPA members. Conclusions: Rural and urban physiotherapists in Saskatchewan have different practice and professional characteristics. This information may have implications for health human resource recruitment and retention policies as well as advocacy for equitable access to physiotherapy care in rural and remote regions.

Key Words: health services accessibility, manpower, rural health

RÉSUMÉ

Objet : Les personnes qui vivent dans des régions rurales et éloignées ont besoin de soutien pour surmonter les difficultés liées à l'accès aux soins de santé. Les objectifs de cette étude étaient: 1) de comparer les caractéristiques démographiques, les indicateurs d'engagement professionnel et les caractéristiques cliniques entre les physiothérapeutes qui pratiquent dans des milieux ruraux et ceux qui travaillent dans des milieux urbains; 2) d'établir la répartition des physiothérapeutes en Saskatchewan. Méthode : Cette étude transversale a utilisé les données dépersonnalisées tirées du renouvellement des adhésions pour 2013 de l'Ordre des physiothérapeutes de la Saskatchewan (n=643), de la liste des membres de 2012 de l'Association de physiothérapie de la Saskatchewan et d'une liste des physiothérapeutes qui ont agi à titre d'enseignants cliniques. Le lieu de travail (rural ou urbain) était déterminé à l'aide des codes postaux. Résultats : Seulement 11,2 % des physiothérapeutes de la Saskatchewan avaient inscrit comme lieu de travail principal un milieu rural, et une plus forte densité de physiothérapeutes par 10 000 personnes travaille dans des régions sociosanitaires où il y a de grands centres urbains. Comparativement aux physiothérapeutes en milieu urbain, les physiothérapeutes en milieu rural sont plus susceptibles de prodiguer des soins directement aux patients, de s'occuper des personnes de tous les âges et de posséder une clientèle variée, mais ils sont moins susceptibles d'être membres de l'Association de physiothérapie de la Saskatchewan. Conclusions : Les physiothérapeutes en milieu rural et urbain en Saskatchewan ont des pratiques et des caractéristiques professionnelles qui diffèrent. Ces renseignements peuvent influer sur les politiques de recrutement et de rétention des ressources humaines en santé, ainsi que sur la promotion de l'accès équitable aux soins de physiothérapie dans les régions rurales et éloignées.

Mots clés : accessibilité aux services de santé, main-d'œuvre, santé rurale

An important theme of health care in Canada is equitable access, defined as the capacity of and opportunity for all individuals to access health care services of similar quality, regardless of barriers.1 The objective of the 1984 Canada Health Act was “to provide reasonable and uniform access to insured health services, free of financial or other barriers.”2 Despite this mandate, however, discrepancies in equitable access to care still exist, particularly between rural and urban populations. People living in rural and remote regions need significant support to overcome difficulties in accessing care and improving health.3 Geographical location constitutes a barrier to equitable access to physiotherapy (PT) care for many Canadians; in Saskatchewan, for example, although rural and remote residents make up approximately 30% of the population, only 10% of physiotherapists practise in these geographical regions.3,4

Access is a multidimensional term that describes the relationship between characteristics and expectations of the health care provider and the patient or client,5,6 including affordability, availability, accommodation, awareness, accessibility, and acceptability.5–7 Availability, for example, is influenced by geographical location and population needs. Affordability barriers such as indirect travel costs and lost wages also factor into equitable access to services. Other factors influencing geographical accessibility include health status, income, location of services, and access to public transport.8 Previous research examining geographical imbalances of human health resources has concluded that strategies to achieve a better distribution of health care professionals must be based on an understanding of the characteristics and dynamics of both health care providers and the patients and populations they serve.9

Although recent research has investigated the supply and distribution of physiotherapists in Canada, several gaps remain in our understanding of access to PT services as it relates to geographical barriers. Little is known about the differences in demographic and professional practice characteristics among urban and rural physiotherapists. Furthermore, location and distribution patterns of PT service delivery beyond primary place of employment have yet to be studied.4,10,11 Holyoke and colleagues10 examined factors that affect the distribution of physiotherapists in Ontario by investigating potential influences of public, private, or quasi-public PT payers. Although they provided information about general PT services distribution, they did not explicitly examine differences between rural and urban geographical distribution.10

A national picture of PT workforce characteristics and distribution is provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information's (CIHI's) annual report.12 CIHI collects and compiles information on supply, demographics, education, employment, geography, and mobility of physiotherapists in Canada, but CIHI data on service delivery locations are presented as dichotomous variables (rural vs. urban) and thus do not show relative rurality, that is, the degree to which a community is influenced by neighbouring urban centres.12 CIHI's reports also do not discuss travel to alternative sites to provide care or examine differences between rural and urban PT service delivery.

Another gap in our understanding of differences between physiotherapists practising in rural settings and those practising in urban settings relates to the question of engagement with the profession. Indications of professional engagement include voluntary membership in the Canadian Physiotherapy Association (CPA) and participation in clinical education through supervision of PT students.11 A recent study in Ontario examined the distribution and type of PT student placements over 1 year relative to the number of practising physiotherapists in the province.11 The study found substantial differences in placement-type mixes across local health integration networks (LHINs) in Ontario; because the analysis did not include comprehensive data on physiotherapist characteristics and practice areas, however, the researchers were not able to identify the reasons for these differences.11 Furthermore, the LHINs represent 14 geographical regions in Ontario, which may or may not encompass both rural and urban settings. Thus, this research could not directly examine the distribution between rural and urban PT placements.11 Finally, the locations of student placements do not necessarily correlate with professional engagement in the clinical education process as a clinical instructor.

Recruiting and retaining health care professionals in rural areas has been a long-standing problem in Saskatchewan, as in many other places in Canada and around the world.9,13 Improving access to PT services in rural and remote communities requires understanding where physiotherapists are geographically distributed, to determine where gaps may exist in PT service availability and how physiotherapists practising in rural and remote regions may differ from their urban counterparts. To identify potential discrepancies in PT services availability between rural and urban areas, we need a comprehensive understanding of physiotherapists' demographic, clinical practice, and professional engagement characteristics.

The purpose of our study, therefore, was to examine the distribution of clinical characteristics of practising physiotherapists in Saskatchewan and identify where access to PT services may be lacking, especially in rural and remote geographical areas. Specifically, our objectives were (1) to examine differences in demographics, professional engagement indicators, and clinical characteristics between physiotherapists practising in rural settings and those practising in urban settings and (2) to map the distribution of physiotherapists in Saskatchewan.

Methods

Study design and data sources

Our cross-sectional study examined the distribution and clinical practice characteristics of physiotherapists who obtained an active practising licence through the 2013 annual renewal of the Saskatchewan College of Physical Therapists (SCPT). All physiotherapists practising in Saskatchewan must have a licence through the SCPT, which they must renew each year to practise legally. Data collected through the 2013 SCPT membership renewal (n=643) were linked with the Saskatchewan Physiotherapy Association (SPA) 2012 membership list (n=406) and with a list of physiotherapists who had served as clinical instructors (for student placements) from 2010 to 2013 (n=278), provided by the Clinical Education Program at the University of Saskatchewan's School of Physical Therapy. Data linkage was performed by an SCPT employee, who then provided the de-identified, linked database to the research team. The study was approved by the University of Saskatchewan Biomedical Research Ethics Board.

The information acquired through this research is potentially valuable to a range of stakeholders, including provincial PT professional organizations, health region managers, and provincial health human resource planners. We therefore used an integrated knowledge translation approach in which representatives from key stakeholder groups participated in informing and developing the research questions and methods, interpreting the results, and disseminating the results in meaningful ways to a variety of target audiences.14 Stakeholder groups included representation from SCPT, SPA, the Clinical Education Unit (CEU) of the School of Physical Therapy and Continuing Physical Therapy Education (CPTE) at the University of Saskatchewan, the Workforce Planning Branch of Saskatchewan Health, and the Saskatoon Health Region. SPA, the provincial branch of CPA, represents physiotherapists by promoting the PT profession and participating in consultation and advocacy activities with government and other stakeholders on behalf of the profession.15 The CEU communicates with coordinators of clinical sites, preceptors, and students to establish, develop, maintain, coordinate, and evaluate clinical placement experiences for PT students in a diverse range of settings.16 CPTE is a postgraduate professional program dedicated to the continuing professional development of physiotherapists and other health care professionals; in addition to delivering courses, CPTE provides educational event development and inter-professional educational events.17

Study variables

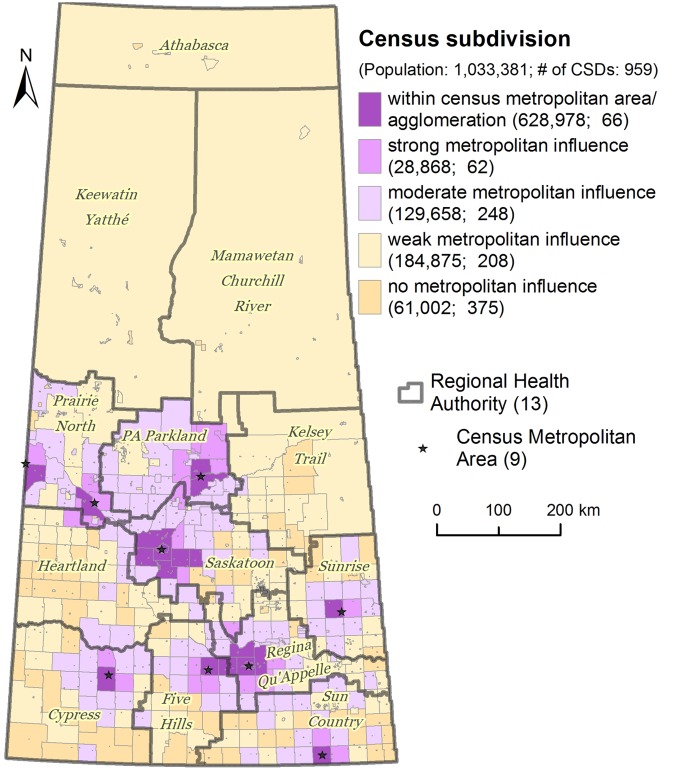

Table 1 outlines the demographic, clinical practice, and professional engagement variables investigated in our study. With the exception of CPA or SPA membership and clinical instructor status, all study variables were obtained from the SCPT database. The dependent variable of interest was primary physiotherapist employment location postal code, which we recoded into an urban or rural category. Urban communities, as defined by Statistics Canada, are those with 10,000 or more inhabitants, such as census metropolitan areas (CMAs) and census agglomerations (CAs). Rural and small-town (RST) communities or areas are census subdivisions (CSDs) that are outside CMAs, and CAs are further classified into metropolitan influence zone (MIZ) categories depending on the proportion of residents who commute to work in urban centres.18 In a rural area with a strong MIZ, at least 30% of the employed labour force commutes to work in an urban area;18 in a moderate MIZ, 5%–30% of the population commutes to work in an urban area; and in a weak MIZ, 5% or less of the population does so.18 The two remaining categories are “no MIZ” (applied to areas with no commuters to urban areas or <40 in the resident labour force) and “territories” (applied to all non-urban areas in Canada's three territories).18

Table 1.

Description of Independent and Dependent Variables

| Variable | Description (if applicable) and categories |

|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | |

| Age | Categories determined by quartiles: ≤32 y, 33–40 y, 41–50 y, ≥51 y |

| Sex | Male, female |

| Place of graduation (PT degree) | University of Saskatchewan, other Canadian university, international |

| PT designation | Level of education achieved on entry to practice: diploma, baccalaureate, master's, doctorate |

| PCE | Has the physiotherapist written and passed the PCE: yes–no |

| Clinical practice characteristics | |

| Rural or urban employment location | A Statistics Canada derived variable; urban residence includes communities with populations ≥10,000 people, and rural communities are disaggregated into sub-groups or metropolitan influenced zones on the basis of the size of commuting flows to any larger urban centre.18 |

| Employment status | Part time, full time |

| Area of PT practice | Direct patient care, PT professor, administration, consultant and research, client service management, more than one system, not available, other |

| Client level | Acute, long-term care, rehab, mixed, N/A, unknown |

| Client age | All ages, adults, seniors, paediatric |

| Sector of employment | Public, private |

| Focus of practice | Musculoskeletal, other (“Other” included neurological, cardiorespiratory, mixed, more than 1, unknown, none) |

| Additional authorized acts | Acupuncture, manipulation, pelvic floor, intramuscular stimulation |

| Professional involvement characteristics | |

| SPA membership | Membership with SPA (2012): Yes–no |

| Clinical instructor | Accepted a student for a clinical placement at least once in the past 3 years (2010–2013): Yes–no |

Note: Some variables were missing data, hence the variable sample sizes.

PCE=Physiotherapy Competency Exam; PT=physiotherapy; SPA=Saskatchewan Physiotherapy Association.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics (frequencies, percentages, means, standard errors, medians, and interquartile ranges for continuous variables) to examine the demographic, clinical practice, and professional membership characteristics of our sample. To explore differences between physiotherapists practising in rural settings and those practising in urban settings (Objective 1), we used bivariate and multivariate approaches using logistic regression. The dependent variable, practice location, was dichotomized into urban or rural, with all categories of RST communities or areas (i.e., strong, moderate, weak or no MIZ) collapsed into rural. Reported employment locations other than the primary location were also explored with descriptive statistics.

The independent variables were transformed and recoded into categorical or dichotomized values to allow for clearer interpretation of the resulting odds ratios (ORs) and to avoid restrictive assumptions of straight-line linearity between variables.19 Variables with more than two levels or categories that had cell counts of zero in the initial bivariate analysis (i.e., cross-tabulation tables) were recoded by collapsing categories of the independent variable. The bivariate analysis explored the association between rural or urban primary employment and physiotherapists' demographic, practice, and other variables using either χ2 tests or Fisher's exact test (when cross-tabulation table cell counts were <5). Any variable for which the bivariate analysis produced a p-value less than 0.25 was considered a candidate for the multivariate analysis. We then applied Spearman's correlation coefficient to evaluate the association between independent variables; among variables that were found to be correlated (r>0.5), we included only the most significant in the multivariate analysis, to avoid multicollinearity in the multivariate model. Backwards stepwise selection (logistic regression) was used to analyze the remaining dependent variables with a p-value of 0.10 to exit the model and 0.05 to enter.19,20 A stepwise selection procedure is recommended for exploratory procedures analyzing the relationships among dependent outcome variables that are not established, and backwards stepwise selections reduce the risk of Type II error.20 The multivariate logistical regression included physiotherapists for whom only complete data were available. The final results are presented as unadjusted (i.e., bivariate) ORs and adjusted ORs with 95% CIs.

To map the distribution of physiotherapists in Saskatchewan, we used the postal code of primary PT employment location. We calculated a set of geographical coordinates (latitude and longitude) for each postal code (n=643), using DMTI's multiple enhanced postal code data set in Geographic Information Systems environment (Platinum Postal Code Suite Version 2011.3, DMTI Spatial, Markham, ON). ArcGIS software (ArcMap Desktop Version 10.1, ESRI, Redlands, CA) was used for data preparation and mapping purposes. Next, with the help of the spatial join tool, information from health region and CSD layers was assigned to the physiotherapist data-point layer. Finally, physiotherapists were aggregated by health region to calculate the ratio of physiotherapists per 10,000 population—a container approach21 widely used in health workforce measures.22 Geographic and demographic data from the 2011 census were used to illustrate the census MIZ and to calculate population ratios.

Results

Participant characteristics

Our analysis included 643 Saskatchewan physiotherapists, of whom 72 (11.2%) listed a rural postal code as their primary place of employment (see Table 2). Participants' mean age was 41.4 (SD 11.08) years (SE 0.437, range 25–71). A total of 232 physiotherapists (36.08%) reported another employment location in addition to their primary location. An additional 26 physiotherapists reported working at more than one location; however, they did not provide geographical information for the second location. Our discussion in the next section therefore includes only 617 physiotherapists. Within this sample of 617, 17 (2.76%) traveled to a site in another health region, and 223 (36.14%) traveled within the same health region. Also, 34 (5.51%) traveled between different MIZ levels, and 13 (2.11%) worked at two or more work sites. Last, 23 (3.73%) physiotherapists traveled from an urban postal code to a rural postal code for work. See Table 2 for additional demographic, clinical practice area, and professional engagement characteristics of the study sample.

Table 2.

Sample by Demographic, Clinical, and Professional Engagement Characteristics

| Variable | No. (%) of respondents |

|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics (n=643) | |

| Sex | |

| Female | 508 (79.0) |

| Male | 135 (21.0) |

| Prior education (n=643) | |

| Educational institution | |

| University of Saskatchewan | 521 (81.0) |

| Other Canadian | 84 (13.1) |

| International | 38 (5.9) |

| Designation | |

| Diploma or certificate | 78 (12.1) |

| Bachelor's degree | 444 (69.1) |

| Master's or doctoral degree | 121 (18.8) |

| Physiotherapy Competency Exam | |

| No | 319 (49.6) |

| Yes | 324 (50.4) |

| Clinical practice characteristics | |

| Employment status (n=629) | |

| Full time | 471 (74.9) |

| Part time | 156 (25.1) |

| Area of practice (n=636) | |

| Direct practice | 550 (86.5) |

| Other | 86 (13.5) |

| Client level (n=599) | |

| Mixed | 332 (55.4) |

| Acute, long-term care, or rehab | 267 (44.6) |

| Client age (n=609) | |

| All ages | 404 (66.3) |

| Adults, senior, paediatrics | 205 (33.7) |

| Sector of employment (n=597) | |

| Public | 347 (58.1) |

| Private | 250 (41.9) |

| Focus of practice (n=628) | |

| Musculoskeletal | 356 (56.7) |

| Other | 272 (43.3) |

| Additional authorized acts (n=643) | |

| Pelvic floor | |

| No | 609 (94.7) |

| Yes | 34 (5.3) |

| Manipulations | |

| No | 609 (94.7) |

| Yes | 34 (5.3) |

| Acupuncture | |

| No | 529 (82.3) |

| Yes | 114 (17.7) |

| IMS | |

| No | 612 (95.2) |

| Yes | 31 (4.8) |

| Professional involvement characteristics | |

| SPA–CPA membership (n=635) | |

| No | 229 (36.1) |

| Yes | 406 (63.9) |

| Clinical instructor (n=643) | |

| No | 365 (56.8) |

| Yes | 278 (43.2) |

IMS=intramuscular stimulation; SPA=Saskatchewan Physiotherapy Association; CPA=Canadian Physiotherapy Association.

Comparison of rural and urban physiotherapist characteristics

Table 3 shows the results of the bivariate analysis comparing urban and rural physiotherapists, dichotomized on the basis of postal code of reported primary employment site; Table 4 summarizes the results of the multivariate analysis examining factors associated with rural primary employer location (both unadjusted and adjusted ORs). Three variables were associated with employment in a rural location: providing direct patient care (adjusted OR=9.79; 95% CI, 1.31–73.38), providing care to all age groups (adjusted OR=2.53; 95% CI, 1.19–5.39), and having a mixed caseload (adjusted OR=6.04; 95% CI, 2.86–12.73). Physiotherapists practising in rural areas were also less likely to be members of SPA or CPA (adjusted OR=0.48; 95% CI, 0.28–0.84).

Table 3.

Association of Physiotherapists' Place of Employment (Rural or Urban) with Their Demographic, Employment or Practice, and Other Professional Characteristics (Bivariate Analysis)

| No./sample size (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics or variables | Urban | Rural | p-value |

| Demographic | |||

| Age (quartile), y | 0.55 | ||

| ≤32 | 155/571 (27.1) | 23/72 (31.9) | |

| 33–40 | 137/571 (24.0) | 12/72 (16.7) | |

| 41–50 | 142/571 (24.9) | 19/72 (26.4) | |

| ≥51 | 137/571 (24.0) | 18/72 (25.0) | |

| Median age: ≤40 y | 282/571 (51.1) | 35/72 (48.6) | 0.69 |

| Sex: female | 448/571 (78.5) | 60/72 (83.3) | 0.34 |

| Employment or practice | |||

| Employment status | 0.96 | ||

| Full time | 418/558 (74.9) | 53/71 (74.6) | |

| Part time | 140/558 (25.1) | 18/71 (25.4) | |

| Practice area | 0.039 | ||

| Direct patient care | 483/565 (85.5) | 67/71 (94.4) | |

| Other (i.e., admin, other, N/A, client service management, more than one system, teaching PT, consultant and research) | 82/565 (14.5) | 4/71 (5.6) | |

| Client age | <0.001 | ||

| All ages | 345/541 (63.8) | 59/68 (86.8) | |

| Adult | 132/541 (24.4) | 7/68 (10.3) | |

| Senior | 42/541 (7.8) | 1/68 (1.5) | |

| Paediatric | 22/541 (4.1) | 1/68 (1.5) | |

| Client level | 274/531 (51.5) | 58/67 (86.6) | <0.001 |

| Mixed | 274/532 (51.5) | 58/67 (86.6) | |

| Acute | 115/532 (21.6) | 7/67 (10.4) | |

| LTC | 21/532 (3.9) | 0/67 (0.0) | |

| Rehabilitation | 122/532 (22.9) | 2/67 (3.0) | |

| Public practice (vs. private) | 307/529 (58.0) | 40/68 (58.8) | 0.90 |

| Practice focus | 0.37 | ||

| MSK | 320/556 (57.6) | 36/70 (51.4) | |

| Neurology | 54/556 (9.7) | 1/70 (1.4) | |

| Cardiorespiratory | 20/556 (3.6) | 1/70 (1.4) | |

| More than 1 system | 133/556 (23.9) | 30/70 (42.9) | |

| Other Professional | |||

| Pelvic floor authorization | 32/571 (5.6) | 2/72 (2.8) | 0.41 |

| Acupuncture authorization | 95/571 (16.6) | 19/72 (26.4) | 0.041 |

| Manipulation authorization | 31/571 (5.4) | 3/72 (4.2) | 1.00 |

| IMS authorization | 26/571 (4.6) | 5/72 (6.9) | 0.38 |

| PCE completion | 285/571 (49.9) | 39/72 (54.2) | 0.50 |

| SPA member | 365/563 (64.8) | 41/72 (56.9) | 0.19 |

| SPA member & division membership | 0.28 | ||

| Clinical instructor | 248/571 (43.4) | 30/72 (41.7) | 0.78 |

| Designation | 0.26 | ||

| Diploma/ certificate | 65/571 (11.4) | 13/72 (18.1) | |

| Baccalaureate | 397/571 (69.5) | 47/72 (65.3) | |

| Master's or doctorate | 109/571 (19.1) | 12/72 (16.7) | |

| Place of graduation | 0.47 | ||

| University of Saskatchewan | 462/571 (80.9) | 59/72 (81.9) | |

| Other Canadian | 77/571 (13.5) | 7/72 (9.7) | |

| International | 32/571 (5.6) | 6/72 (8.3) | |

LTC=long-term care; MSK=musculoskeletal; IMS=intramuscular stimulation; PCE=Physiotherapy Competency Exam; SPA=Saskatchewan Physiotherapy Association.

Table 4.

Summary of Multivariate Model for Factors Associated with Rural Primary Employment Location

| OR (95% CI) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Unadjusted | Adjusted |

| Direct patient care | 2.84* (1.01–8.01) | 9.79* (1.31–73.38) |

| Clients all ages (vs. paediatrics, senior, or adult only) | 3.72* (1.81–7.67) | 2.53* (1.19–5.39) |

| Client level mixed (vs. acute, LTC, or rehab) | 6.07* (2.95–12.50) | 6.04* (2.86–12.73) |

| SPA/CPA member | 0.72 (0.44–1.18) | 0.48* (0.28–0.84) |

Significant at p<0.05.

OR=odds ratio; LTC=long-term care; SPA=Saskatchewan Physiotherapy Association; CPA=Canadian Physiotherapy Association.

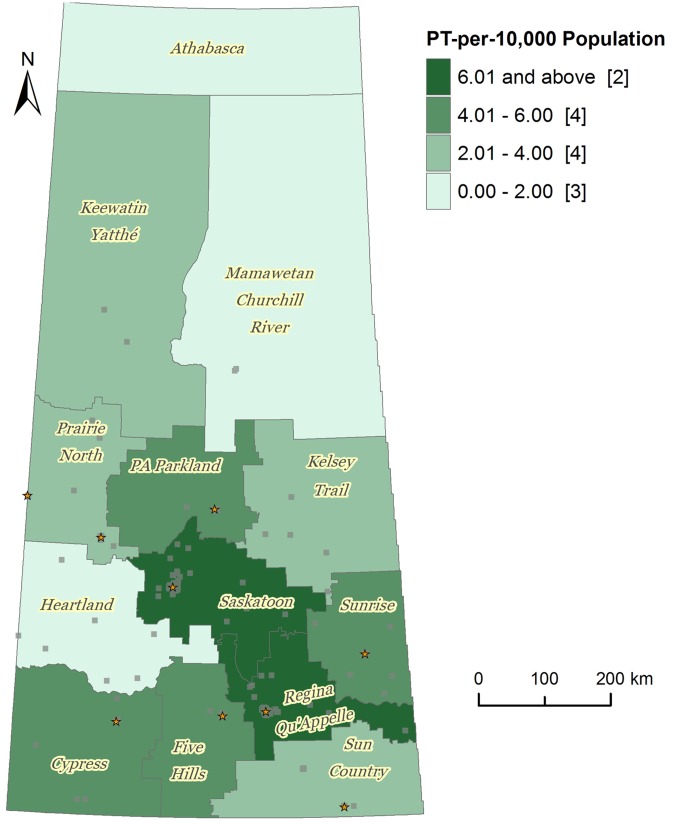

Figure 1 shows the spatial distributions of MIZ categories across Saskatchewan, as well as the 13 regional health authorities; Figure 2 shows the physiotherapist ratio (i.e., physiotherapists per 10,000 population) across Saskatchewan health regions. To create the map in Figure 2, we categorized the physiotherapist ratios along with the number of health regions into four classes: 2.00 per 10,000 or less, 2.01–4.00 per 10,000, 4.01–6.00 per 10,000, and 6.01 per 10,000 or more. Physiotherapist ratios were high (≥6.01 per 10,000 population) in the Saskatoon and Regina–Qu'Appelle health regions; the Athabasca, Mamawetan Churchill River, and Heartland health regions fell in the lowest class (≤2.00 per 10,000 population).

Figure 1.

Study area map: metropolitan influence zone categories. CSD=census subdivision.

Figure 2.

Physiotherapist ratio by health region: number of physiotherapists per 10,000 population.

Discussion

Our objectives in this study were to compare demographic, clinical, and professional engagement characteristics between rural and urban practising physiotherapists in Saskatchewan and to identify PT service distribution, especially in rural and remote geographical locations. Our results show a tremendous geographical imbalance between where PT services are delivered and where people in Saskatchewan live: Only 11.2% of physiotherapists listed a rural location as their primary place of employment, whereas approximately 36.0% of Saskatchewan's population lives in rural areas.3 We also found that rural physiotherapists were more likely than their urban counterparts to provide direct patient care, to provide care to all ages, and to have a mixed caseload and that they were less likely to be members of SPA or CPA. We found no other significant differences in demographic, clinical practice, or professional characteristics between rural and urban physiotherapists.

Our findings may be applicable to other Canadian provinces because a large segment of Canada's population lives in rural and remote locations—ranging from 15% in Ontario and British Columbia to as much as 68% in Nunavut.3 Although Ontario and British Columbia have a smaller proportion of residents in rural and remote regions, the populations of these provinces are very large, and thus the total rural and remote population is still relatively high.3

The high proportion of physiotherapists practising in the Saskatoon Health Region, home to the only university PT program in the province, is not surprising; in Ontario, similarly, LHINs that host a university PT university program have the highest ratio of practising physiotherapists per 100,000 people.11 These employment trends may reflect new graduates' preference for working in a familiar setting where they have pre-established social and professional ties.

Within our sample, rural physiotherapists reported a more generalist practice, with greater likelihood of a mixed and all-ages caseload. This finding is consistent with those of a study examining rural physiotherapist characteristics in Australia,23 which also reported that being a generalist was associated with lower job satisfaction, particularly when respondents believed their work was less valued than that of other members of their profession.23 Decreased job satisfaction was attributed to a variety of factors, including professional isolation, poor access to education and training, lack of financial incentives, and lack of opportunity to use specialized skills.23

In Saskatchewan, these factors could help explain why some health regions are experiencing increased difficulty in recruiting and retaining physiotherapists to work in rural and remote regions. Interestingly, we did not find any differences in rural versus urban distribution between physiotherapists working in private practice settings and those working in public practice settings, which suggests that rural recruitment and retention is likely an equally important issue in both the public and the private sectors. The addition of a new rural division in the CPA may help to provide additional support for those physiotherapists working in rural and remote regions. Virtual communities of practice, which use technology to link rurally based physiotherapists with other physiotherapists and health care professionals, are another potential mechanism to help provide support, reduce feelings of isolation, and improve job satisfaction.24–26

The urban–rural imbalance in physiotherapists' distribution calls for an examination of recruitment and retention strategies for rural and remote settings. Playford and colleagues, 27 who investigated the distribution of rural clinical student placements, concluded that a rural placement of 4 weeks or less during the final year of study positively influences a student's future decision to work rurally. Strategies currently in place in Saskatchewan to promote rural retention include financial incentives such as return-for-service bursaries and relocation allowances; according to the Saskatchewan Ministry of Health, all regional health authorities receive dedicated budgets to engage health professionals in return-for-service bursaries.28 Given the apparent disparity of PT service delivery in rural and remote locations, however, further recruitment and retention strategies should be explored.

Primary health care services within an area should match the population's health needs to deliver quality service.6 Unfortunately, our results show a disconnect between the number of physiotherapists practising in Saskatchewan's rural and remote regions and the population living in these areas. In addition to the obvious geographical barriers to access, this imbalance in health service delivery may create additional barriers for rural and remote residents, such as the costs and time associated with travel away from their home locations and the resulting loss of productivity and wages from time off work.

The most obvious barrier to access in rural and remote areas is that availability of services is limited relative to where people live; however, understanding distribution of PT services alone is not enough. To further identify where disparities exist, we need to identify population health characteristics and needs of rural and remote residents and link these to PT distribution and practice characteristics. In a health care system based on equity, people with the greatest need for PT services should be able to access those services more easily than others.8 However, these needs are evidently not being met, because studies have shown that Canadians living in rural communities tend to have poorer health status than those living in urban settings;29 for example, rural-dwelling Canadians are 30% more likely to have chronic back pain than their urban counterparts.30 Given the predominant generalist practice characteristics of rural physiotherapists, whether the unique needs of rural and remote residents are being met is unclear, especially of those who may benefit from a more specialized approach. Therefore, equating equitable access with availability of resources paints an inadequate picture of barriers to access.7

Future research should focus on determining whether there is a link between the distribution of health human resources and services and population health characteristics and needs. Also of interest is determining whether equitable access to PT services exists on the basis of location, cost, and wait times. A study has been initiated that will explore the distribution of physiotherapists in Saskatchewan in relation to population health characteristics and needs; this work will allow areas of need to be identified geographically and will help in advocating for equitable access to PT services.

Further research is required to identify changes in rural and urban physiotherapist characteristics over time in Saskatchewan, as well as relating these changes to populations' identifiable health needs. In addition, innovative models of PT service delivery, such as use of telehealth and other e-health technologies, should be explored and evaluated to determine where and how the urban–rural divide in access to PT can be narrowed. Relating physiotherapist characteristics and distribution to accessibility of services will ultimately help policymakers and other decision makers in developing strategies to facilitate more appropriate and equitable distribution and access to PT services.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, a cross-sectional study provides data from only a specific point in time; therefore, we cannot identify causal relationships between associated variables, nor can we evaluate changes in PT distribution over time.

Second, the majority of our data were collected from 2013 SCPT membership renewal forms completed by Saskatchewan physiotherapists. Because some of these forms were missing data, our multivariate analysis did not include all participants, which may have skewed the results. Similarly, if participants provided only one postal code and did not explicitly designate it as an employment location (i.e., 50 of 643; 7.8% of the total sample), it was coded as their primary place of employment. This may have resulted in misclassification bias because this group may have included respondents who listed their residential and not their employment postal code. Although we explored employment locations other than the primary location, only place of primary employment was included in the bivariate and multivariate analysis. Our mapping and multivariate results may, therefore, not be representative of all rural and urban locations in which PT services are delivered. Our analysis eliminated any physiotherapist who reported an employer outside of Saskatchewan and thus may have excluded those who are licensed in multiple provinces but still provide services in Saskatchewan. For this reason, our results may underestimate the distribution of rural and urban practising physiotherapists in Saskatchewan.

Finally, ethical concerns regarding confidentiality prevent us from reporting cell counts less than five, which means that we are unable to report the clinical practice characteristics and demographics of physiotherapists working in the northern Saskatchewan health regions (Keewatin Yatthé, Mamawetan Churchill River, and Athabasca) because so few physiotherapists work in these regions.

Conclusion

Equitable access to health care means that services are available and distributed on the basis of patients' needs.31 People who live in rural or remote locations have the greatest need for support in overcoming difficulties with accessing health care.3 This study identified the distribution, demographics, clinical practice characteristics, and professional engagement indicators of physiotherapists in Saskatchewan.

Urban and rural regions of Saskatchewan have a geographical imbalance in the distribution of physiotherapists relative to the distribution of the population. Rural physiotherapists are different from urban physiotherapists in that they are more likely to provide direct patient care, to provide care to patients of all ages, and to have a mixed caseload, and they are less likely to be members of SPA or CPA. These findings provide evidence that rural and urban physiotherapists have different practice and professional characteristics. The geographical distribution of physiotherapists relative to the population reinforces known disparities in access and delivery of PT services between urban and rural regions of Saskatchewan. These findings may help to guide future research toward health services and policies, both provincial and national, aimed at developing equitable access to PT services.

Our findings highlight differences between rural and urban physiotherapists—including client level, patient age, and overall caseload—that may have implications for provincial and national health human resource recruitment strategies and policies, as well as for advocacy for equitable access to PT services. Our findings also provide baseline data for future research to investigate methods of improving access to PT services and serve as a template for research and advocacy efforts with a national or international scope.

Key Messages

What is already known on this topic

The recruitment and retention of health care professionals to rural areas has been a long-standing problem in Saskatchewan as well as in other areas of Canada and the world. The distribution of physiotherapists in Saskatchewan is known to be unequal to both urban and rural population characteristics; however, the demographic and clinical professional practice characteristics of physiotherapists in Saskatchewan, and across Canada, remain largely unexamined.

What this study adds

Rural physiotherapists in Saskatchewan are more likely than their urban counterparts to practise in a more generalist capacity and less likely to be members of the Saskatchewan Physiotherapy Association or the Canadian Physiotherapy Association. This study provides a basis for future research investigating the use of and access to PT services in Saskatchewan. Its methods may be applied to mapping the distribution, demographics, and clinical practice characteristics of the PT profession on a national level, including an interprovincial comparison of PT distribution and population health needs.

References

- 1. Central Local Health Integration Network [homepage on the Internet]. A provisional definition of “equitable access” developed by the central LHIN's access and coordination panel. Markham (ON): Central Local Health Integration Network; c2007. [cited 2015 Apr 7]. Available from: http://www.centrallhin.on.ca/boardandgovernance/boardmeetings/~/media/sites/central/uploadedfiles/Home_Page/Board_of_Directors/Board_Meeting_Submenu/Item8.8bDefinitionofEquitableAccess-Oct-23-07.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2. Canada Health Act, 31 (1) and (2) of the Legislation Revision and Consolidation Act R.S.C., 1985, c. C-6 (1984)

- 3. Romanow RJ. Building on values: The future of health care in Canada: Final report. Saskatoon (SK): Commission on the Future of Health Care in Canada; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Physiotherapists in Canada, 2010 national and jurisdictional highlights and profiles. Ottawa: The Institute; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The concept of access: definition and relationship to consumer satisfaction. Med Care. 1981;19(2):127–40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198102000-00001. Medline:7206846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Russell DJ, Humphreys JS, Ward B, et al. Helping policy-makers address rural health access problems. Aust J Rural Health. 2013;21(2):61–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12023. Medline:23586567 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McLaughlin CG, Wyszewianski L. Access to care: remembering old lessons. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1441–3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12171. Medline:12546280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gulliford M, Morgan M, editors. Access to health care. New York: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dussault G, Franceschini MC. Not enough there, too many here: understanding geographical imbalances in the distribution of the health workforce. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4(1):12 http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-4-12. Medline:16729892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holyoke P, Verrier MC, Landry MD, et al. The distribution of physiotherapists in Ontario: understanding the market drivers. Physiother Can. 2012;64(4):329–37. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/ptc.2011-32. Medline:23997387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Norman KE, Booth R, Chisholm B, et al. Physiotherapists and physiotherapy student placements across regions in Ontario: a descriptive comparison. Physiother Can. 2013;65(1):64–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/ptc.2011-63. Medline:24381384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Physiotherapists in Canada, 2011 national and jurisdictional highlights. Ottawa: The Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13. MacDowell M, Glasser M, Fitts M, et al. A national view of rural health workforce issues in the USA. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(3):1531 Medline:20658893 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Canadian Institutes of Health Research [homepage on the Internet]. Ottawa: The Institutes; c2009. [cited 2014 Jun 3]. About knowledge translation [about 1 screen] Available from: http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/29418.html. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Saskatchewan Physiotherapists Association [homepage on the Internet]. Saskatoon (SK): The Association; c2014. [cited 2014 Jun 3]. About the SPA [about 1 screen] Available from: http://www.saskphysio.org/about-spa/about-our-association. [Google Scholar]

- 16. School of Physical Therapy University of Saskatchewan [homepage on the Internet]. Saskatoon (SK): The University; c2008. [cited 2014 Jun 3]. Communication with clinical sites [3 pages] Available from: http://www.medicine.usask.ca/pt/clinical-education/general-clinical-education-policies-and-procedures/Communication%20with%20Clinical%20Sites%20Policy%20Sept%202008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17. University of Saskatchewan Continuing Physical Therapy Education [homepage on the Internet]. About CPTE. Saskatoon (SK): The University; c2010. [cited 2015 Apr 7]. Available from: http://www.usask.ca/cpte/about/index.php [Google Scholar]

- 18. Du Plessis V, Beshiri R, Bollman RD, et al. Definitions of rural. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hosmer DW Jr, Lemeshow S. Applied logistic regression. New York: Wiley; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Field A. Discovering statistics using SPSS. 3rd ed. London: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cromley EK, McLafferty SL. GIS and public health. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Landry MD, Ricketts TC, Fraher E, et al. Physical therapy health human resource ratios: a comparative analysis of the United States and Canada. Phys Ther. 2009;89(2):149–61. http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20080075. Medline:19131399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fitzgerald K, Hudson L, Hornsby D. A study of allied health professionals in rural and remote Australia. Deakin (ACT): Services for Australian Rural and Remote Allied Health; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Demiris G. The diffusion of virtual communities in health care: concepts and challenges. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62(2):178–88. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2005.10.003. Medline:16406472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li LC, Grimshaw JM, Nielsen C, et al. Use of communities of practice in business and health care sectors: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):27 http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-27. Medline:19445723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Eysenbach G, Powell J, Englesakis M, et al. Health related virtual communities and electronic support groups: systematic review of the effects of online peer to peer interactions. BMJ. 2004;328(7449):1166 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1166. Medline:15142921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Playford D, Larson A, Wheatland B. Going country: rural student placement factors associated with future rural employment in nursing and allied health. Aust J Rural Health. 2006;14(1):14–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1584.2006.00745.x. Medline:16426427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Government of Saskatchewan [homepage on the Internet]. Regina (SK): Government of Saskatchewan; c2012. [cited 2014 Jun 24]. Bursaries 2014–2015 Available from: http://www.health.gov.sk.ca/bursaries-current-year [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wielandt PM, Taylor E. Understanding rural practice: implications for occupational therapy education in Canada. Rural Remote Health. 2010;10(3):1488 Medline:20858017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bath B, Trask C, McCrosky J, et al. A biopsychosocial profile of adult Canadians with and without chronic back disorders: a population-based analysis of the 2009–2010 Canadian Community Health Surveys. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:919621 http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/919621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Aday LA, Andersen R. A framework for the study of access to medical care. Health Serv Res. 1974;9(3):208–20. Medline:4436074 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]