Abstract

A summary of results from the solid samples run on our compact 1 MV AMS system over its 13.5 years of operation is presented. On average 7065 samples per year were measured with that average dropping to 3278 samples per year following the deployment of our liquid sample capability. Although the dynamic range of our spectrometer is 4.5 orders in magnitude, most of the measured graphitic samples had 14C/C concentrations between 0.1 and 1 modern. The measurements of our ANU sucrose standard followed a Gaussian distribution with an average of 1.5082 ± 0.0134 modern. The LLNL biomedical AMS program supported many different types of experiments, however, the large majority of samples measured were derived from animal model systems. We have transitioned all of our biomedical AMS measurements to the recently installed 250 kV SSAMS instrument with good agreement compared in measured 14C/C isotopic ratios between sample splits. Finally, we present results from replacement of argon stripping gas with helium in the SSAMS with a 22% improvement in ion transmission through the accelerator and high-energy analyzing magnet.

Keywords: accelerator mass spectrometry, SSAMS, graphite, biomedical AMS, 14C

INTRODUCTION

Purchased in 1999, the LLNL 1-MV spectrometer was one of the first of the new smaller AMS systems and was designed to serve our biomedical research program[1]. This system occupied approximately 20% of the footprint, offered simplified operation and maintenance and, hence, a lower cost of operation over our larger 10-MV FN tandem accelerator. The system was configured with a copy of LLNL's high-output Cs sputter ion source coupled to an NEC 3SDH-1 tandem accelerator and analysis beamline. Routine operation for the analysis of 14C from graphite targets, prepared from biomedical samples, began in April 2001. Analysis throughput was approximately 100 samples per 8-hour day, achieving 3-5% precision of the relative standard error of the mean of 3-10 measurements, on samples containing carbon isotope concentrations typically between 10−14 to 10−10 14C/C. Routine 3H-AMS analysis capability was enabled in 2007 with the addition of a second ion source and injection beam line. This second ion source is a heavily modified NEC MCGSNICS and was designed to ionize both solid and gaseous targets[2]. The injection beamline was configured to allow either the simultaneous measurement of 3H/1H ratios from solid TiH2 targets or the measurement of 14C/12C from solid graphite or CO2 samples[3]. The gas-ionization capabilities of this ion source were not fully exploited until the installation of a moving wire interface in 2012[4]. This interface enables the analysis of small liquid samples, either as discrete microliter-sized drops or directly coupled to the output of an HPLC[5]. We are further expanding our Liquid Sample AMS capabilities by building two more copies of our moving wire interface for deployment on a recently installed 250 kV SSAMS. This new system has replaced our 1-MV compact AMS for the analysis of 14C in biomedical samples.

This manuscript presents a summary of the solid samples analyzed by the 1-MV AMS system and presents initial characterization data of our recently installed Single Stage Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (SSAMS) system.

SOLID SAMPLE ANALYSIS

Figure 1 plots the yearly totals of solid targets for 14C-AMS, prepared as graphite[6], and 3H-AMS, prepared as TiH2. Also shown are the major instrumentation developments in the year they were deployed. Since routine operations began in 2001, 87,551 solid samples have been measured, with graphite targets representing the overwhelming majority (>98%). Most of these samples arose from research projects that were supported through our National Institutes of Health funded Research Resource on Biomedical Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (https://bioams.llnl.gov). In general, the spectrometer was operated 2-3 days per week for approximately 8-9 hours a day. We had flexibility to modify operations, depending on the number of samples awaiting measurement as the spectrometer sat idle most other times. The significant drop in yearly totals after 2011 can be traced to the completion of several projects that generated many samples, as well as an increase in the use of the moving wire interface to measure liquid samples directly. Operation of the 1-MV system for the measurement of biomedical samples ceased on November 1, 2014 as we have successfully transitioned over to the recently installed SSAMS.

Figure 1.

Yearly totals for all solid samples measured on the 1 MV AMS system since routine operations began in 2001 through final “decommissioning for bio” in 2014. Samples were measured as either graphite for 14C-AMS or TiH2 for 3H-AMS. Also shown in the plot is the year in which major technological innovations were deployed.

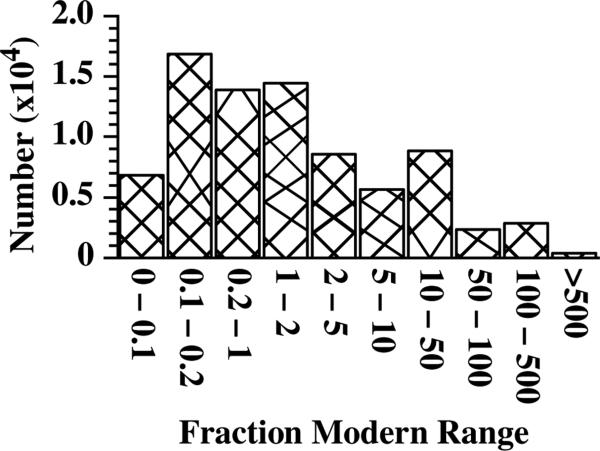

Figure 2 plots the fraction modern data for all graphitic samples (excluding standards) measured on the 1 MV BioAMS spectrometer. Samples with 14C/C concentrations below 0.1 modern were typically background materials or aerosol monitors which are admixtures of iron powder and fullerene soot packed into sample holders and deployed in laboratories and other workspaces to assess for any potential contamination from volatile compounds containing 14C[7]. Samples with 14C/C concentrations between 0.1 and 0.2 modern were typically aliquots of our carbon carrier samples. The routine preparation of graphitic targets from potentially highly labelled biomedical samples requires a minimum sample size of 0.5 mg carbon. Small samples, such as fractions collected from a high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system are bulked up with the addition of 1 μl of tributyrin (1,3-Di(butanoyloxy)propan-2-yl butanoate), which provides 0.6 mg carbon to the sample. The proper analysis of these HPLC fractions or other small samples requires the measurement of these carbon carrier samples[8]. The number of samples in this fraction modern bin is indicative of the large number of samples that were processed with the addition of carrier carbon. The 14C/C concentrations of the individual HPLC fractions or other small samples, such as isolated DNA or proteins, often fell into the next bin of 0.2 to 1 modern. Similarly, unlabeled controls for samples that provided sufficient carbon for analysis would have fraction moderns between 1 and 2. The ideal range for bioAMS samples in terms of measurement throughput and contamination control falls between 1 and 100 modern. Above this level, corrections for data acquisition dead times begin to get less reliable, as well as increasing concerns regarding the potential for laboratory contamination with 14C.

Figure 2.

Distribution of fraction modern results for all measured graphitic samples, excluding primary standards. Nearly half (47%) of all these samples had a fraction modern of 1 modern or less.

Biochemical AMS samples were typically measured to 3-5% precision, with the exception of standards, which were measured to 1% precision. Our most common standard used was ANU sucrose. Figure 3 shows a histogram plot of the results from 5097 samples of our ANU sucrose standards that provided acceptable ion currents measured on the 1-MV AMS spectrometer over the years of operation. Also plotted is a Gaussian fit, using a Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm, of the data (chi-squared = 0.0241). The average fraction modern and 1-sigma standard deviation of the data is 1.5082 ± 0.0134, which agrees with the average and 1-sigma deviation of the Gauss fit, 1.5078 ± 0.0105. Our data agrees with the consensus value of 1.5081 ± 0.0020, as published by Currie and Polach, 1980[9].

Figure 3.

Fraction modern distribution of nearly 5100 ANU sucrose standard samples. The dashed line depicts the result of a Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm fit as a Gaussian distribution.

Table I shows the sample type breakdown for graphite samples measured on the 1-MV AMS system along with examples of the type of studies conducted. The most common sample type we measured is that derive from animal tissue samples; either an organ, plasma or excreta. Such samples are crucial to understanding the distribution and kinetics of a toxin or therapeutic. In addition to measuring the entire homogenate, we may also isolate DNA or proteins to assess chemical binding through the formation of adducts. The isolation of metabolites is primarily accomplished by the use of biochemical separatory instrumentation, such as high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Often the entire chromatogram is collected as fractions, generating, on average, 30 individual samples. However, if there is interest in a few metabolites, only fractions around the metabolite(s) of interest may be collected and converted to graphite, significantly reducing the total number of samples submitted for analysis.

Table I.

Distribution of sample types prepared for analysis on the 1-MV AMS system, along with examples of the typical studies conducted.

| Sample Type | (%) | Example Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Nonhuman tissue sample or extract | 22 | Mass balance, biodistribution |

| Nonhuman DNA or protein isolate | 16 | Toxicology; DNA/protein adduct binding |

| Nonhuman HPLC fraction | 16 | Model system metabolism |

| Human tissue sample or extract | 10 | Pharmacokinetics, bioavailability |

| Human sample HPLC fraction | 8 | Human metabolism |

| Cell culture extract | 7 | Pathway analysis, binding studies |

| Swipes, aerosol monitors | 13 | Contamination checks |

| Methods development | 7 | Backgrounds, test solutions |

| Other | 1 | Soils, gases, plants, etc. |

Plasma is the most common type of human sample that we have processed, followed by excreta although, in a few instances, we have analyzed samples obtained through a biopsy. These experiments primarily investigate the pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of test compounds, either drugs, toxicants or nutrients. While the strength of AMS is in the capability to assess effects from small realistic exposures in humans, animal models are still relied upon for much of the work done through the bioAMS Research Resource at LLNL.

In addition to human and animal studies, we processed samples derived from cell cultures, from basic eukaryotes to human cell lines. Such studies need to be carefully assessed for the suitability in using AMS for 14C detection, for in general, one is not limited, based on ethical grounds, to the amount of radiation or chemical dose that may be used. However, in instances where the dose must be limited to prevent perturbation of cellular metabolism or cell culture volumes must be limited, AMS offered the only detection method available. Most often, cells were processed to separate specific organelles or intracellular metabolites, although whole cells were sometimes analyzed.

All swipes sent to CAMS were measured on the 1-MV AMS system after processing through our bioAMS sample processing laboratory. We often requested swipes from new collaborators to assess their laboratories prior to beginning any low dose experiments. Additionally, swipes were requested following a contamination event either to determine the source of contamination or to assess the effectiveness of cleanup efforts. This assessment was also extremely important for new investigators working with natural abundance 14C who were moving into a recently refurbished laboratory, as large scale laboratory equipment, such as fume hoods and benches, tend to be recycled and their history is often unknown. Also, buildings have may have an unknown history of past radiocarbon use and there could be existing 14C “hot spots” that could lead to future contamination events.

We exclude from this table the several thousand human samples collected and measured from our “bomb pulse biology” investigations of cell turnover. The extremely small sample size and higher precision requirements made them more amenable for processing in the CAMS natural 14C sample preparation laboratory and measurement on the larger 10 MV FN tandem[10].

BIODECK

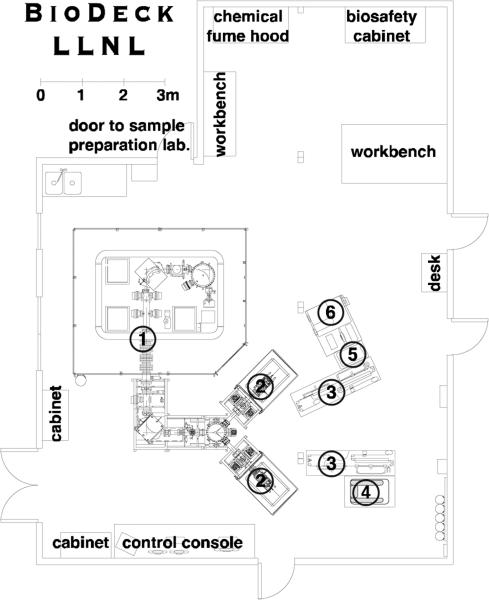

In April 2014, we completed the installation of a 250 kV SSAMS purchased from National Electrostatics Corporation[11]. Figure 4 shows a schematic of our newly christened “BioDeck” laboratory, which is configured with a 250 kV SSAMS with two MCGSNICS gas-accepting ion sources, each with a copy of our moving wire interface for the analysis of small liquid samples. This system has been placed next to our biomedical sample preparation laboratories to better connect the biomedical researchers to the spectrometer. Importantly, this system has been placed in a laboratory with Biosafety Level 2 controls[12], enabling the handling and direct analysis of human tissue samples.

Figure 4.

A schematic representation of our newly constructed BioDeck laboratory consisting of a 250 kV SSAMS (1) with two gas-accepting MCGSNICS cesium sputter ion sources (2), and two moving wire interface benches for the analysis of small liquid samples (3). One bench is configured with a Hamilton NIMBUS liquid handling robot (4) while the other is configured with a Waters Corporation H-Class UPLC (5) and a Waters Corporation Xevo G2XS QTof/Tof mass spectrometer (6).

Our initial commissioning of this system consisted, in part, in the preparation of duplicate graphite aliquots from the same sample with one measured on each spectrometer. Figure 5 shows the results of 193 samples. Good agreement over three orders in dynamic range is observed, with the most significant differences observed at the lowest fraction modern values. However, ion output is approximately 3-4 times lower, significantly reducing sample throughput. Further work will focus on improving ion currents and assessing background levels.

Figure 5.

Fraction modern results for separate graphitic samples prepared from the same material and measured on both the 1 MV AMS system and our recently installed SSAMS. Error bars are smaller than the data points. The solid line represents y=x. Good agreement is seen over three orders in magnitude, with the largest discrepancies observed from samples with the lowest 14C/C concentration.

We compared the effect of stripping gas on molecular ion breakup and ion transmission. Presented in Figure 6 is data where we varied the flow rate of either argon (top) or helium (bottom) gas into the stripper canal. The measurement from the vacuum gauge above the gas entrance was used as a proxy for stripper gas thickness. In both plots, the closed circles are the results of 10-second measurements of 14C/13C isotope ratios from a graphitized sample of ANU sucrose. As expected, at lower stripper gas densities, the 14C/13C ratio is artificially high due to incomplete molecular ion disassociation. As the gas density increases, this ratio decreases and eventually levels out to the true value of the sample. For both gases, the final ratio of the ANU sucrose sample is the same, however, that final ratio is achieved at a lower pressure using helium as it is using argon as the stripper gas.

Figure 6.

Variation in 14C/13C (“disassociation”; •) and 12Che/12Cle (“transmission”; +) ratios with respect to different stripper gas concentrations. The top plot shows the results in which argon was used as the stripping gas medium while the bottom used helium gas. The stripper pressure, which is a proxy for the stripper gas thickness, is the value as recorded by the gauge, which is calibrated for N2 gas, located above the entrance of the stripper canal.

Also plotted in the two plots are measurements of the 12C ratio as measured in the off axis Faraday cups either after the high-energy analyzing magnet (12Che) or after the low energy injection magnet (12Cle). The 12Che/12Cle isotope ratio gives a measure of the transmission through the acceleration tube. Here the benefits of helium gas over argon gas are clearly seen with the ion transmission approximately 22% greater using the lighter gas. However, achieving sufficient molecular ion destruction requires a significantly greater amount of helium than it does using argon. We flow He at approximately 7.5 sccm/min while Ar was flowed at 0.7 sccm/min. Additionally, we found that the helium bottle must be placed onto the high voltage platform of the SSAMS to prevent electrical discharge along the helium gas line to ground. Despite its higher consumption rate, helium gas will be regularly used for future measurements as it enables greater ion transmission while providing the same level of interfering molecular isobar destruction as argon gas.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

We have transitioned all of our 14C measurements from the 1 MV system to our new 250 kV SSAMS system. The 1 MV system is presently undergoing modifications in which the hybrid source will be connected directly to the low energy injection magnet, effectively removing the LLNL ion source and 45° ESA. Initially, a TDOC will be connected to the hybrid source and the CO2 produced by this instrument will be measured directly from natural 14C abundance environmental samples for carbon cycle studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Work performed at the Research Resource for Biomedical AMS, which is operated at LLNL under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy under contract DE-AC52-07NA27344, is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS), Biomedical Technology Research Resources (BTRR) under grant number 8P41GM103483.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ognibene TJ, Bench G, Brown TA, Peaslee GF, Vogel JS. A new accelerator mass spectrometry system for C-14-quantification of biochemical samples. Int. J. Mass Spectrom. 2002;218:255–264. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ognibene TJ, Salazar GA. Installation of hybrid ion source on the 1-MV LLNL BioAMS spectrometer. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B. 2013;294:311–314. doi: 10.1016/j.nimb.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ognibene TJ, Bench G, Brown TA, Vogel JS. Ion-optics calculations and preliminary precision estimates of the gas-capable ion source for the 1-MV LLNL BioAMS spectrometer. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B. 2007;259:100–105. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas AT, Stewart BJ, Ognibene TJ, Turteltaub KW, Bench G. Directly Coupled High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Measurement of Chemically Modified Protein and Peptides. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:3644–3650. doi: 10.1021/ac303609n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas AT, Ognibene T, Daley P, Turteltaub K, Radousky H, Bench G. Ultrahigh Efficiency Moving Wire Combustion Interface for Online Coupling of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Anal. Chem. 2011;83:9413–9417. doi: 10.1021/ac202013s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ognibene TJ, Bench G, Vogel JS, Peaslee GF, Murov S. A high-throughput method for the conversion of CO2 obtained from biochemical samples to graphite in septa-sealed vials for quantification of C-14 via accelerator mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2003;75:2192–2196. doi: 10.1021/ac026334j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchholz BA, Freeman S, Haack KW, Vogel JS. Tips and traps in the C-14 bio-AMS preparation laboratory. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B. 2000;172:404–408. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogel JS, Love AH. Quantitating isotopic molecular labels with accelerator mass spectrometry. Biol. Mass Spectrom. 2005;402:402–422. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)02013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Currie LA, Polach HA. Exploratory Analysis of the International Radiocarbon Cross- Calibration Data: Consensus Values and Inter-Laboratory Error. Radiocarbon. 1980;22:933–935. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falso MJS, Buchholz BA. Bomb pulse biology. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B. 2013;294:666–670. doi: 10.1016/j.nimb.2012.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klody GM, Schroeder JB, Norton GA, Loger RL, Kitchen RL, Sundquist ML. New results for single stage low energy carbon AMS. Nucl. Instrum. Meth. B. 2005;240:463–467. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chosewood LC, Wilson DE. In: Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories (BMBL) 5th Edition P.H.S. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health, editor. Government Printing Office; 2009. p. 415. [Google Scholar]