SUMMARY

Purpose

To assess the impact of a voluntary withdrawal of over-the-counter cough and cold medications (OTC CCMs) labeled for children under age 2 years on pediatric ingestions reported to the American Association of Poison Control Centers.

Methods

Trend analysis of OTC CCMs ingestions in children under the age 6 years resulting from therapeutic errors or unintentional poisonings for 27 months before (pre-) and 15 months after (post-) the October 2007 voluntary withdrawal was conducted. The rates and outcome severity were examined.

Results

The mean annual rate of therapeutic errors involving OTC CCMs post-withdrawal, in children less than 2-years of age, 45.2/100 000 (95%CI 30.7–66.6) was 54% of the rate pre-withdrawal, 83.8/100 000 (95%CI 67.6–104.0). The decrease was statistically significant p < 0.02. In this age group, there was no difference in the frequency of severe outcomes resulting from therapeutic errors post-withdrawal. There was no significant difference in unintentional poisoning rates post-withdrawal 82.1/100 000 (66.0–102.2) vs. pre-withdrawal 98.3/100 000 (84.4–114.3) (p < 0.21) in children less than 2-years of age. There were no significant reductions in rates of therapeutic errors and unintentional poisonings in children ages 2–5 years, who were not targeted by the withdrawal.

Conclusions

A significant decrease in annual rates of therapeutic errors in children under 2-years reported to Poison Centers followed the voluntary withdrawal of OTC CCMs for children under age 2-years. Concerns that withdrawal of pediatric medications would paradoxically increase poisonings from parents giving products intended for older age groups to young children are not supported.

Keywords: cough and cold medications, pediatric, poisoning, therapeutic error

INTRODUCTION

Over-the-counter (OTC) cough and cold medications (CCMs) include various combinations of antihistamines, decongestants, antitussives, expectorants, and analgesics. From 1999 to 2006, as many as 10% of children in the United States used these products each week, with the highest use in children ages 2–5 followed by children under age 2 years.1 The use of over-the-counter cough and cold medications (OTC CCMs) in young children is being scrutinized due to lack of evidence supporting the efficacy of these medications as well as reports of significant associated adverse effects, including death.2–5

In October 2007, pharmaceutical manufacturers voluntarily withdrew OTC CCMs labeled for use in children under the age of 2 years.6 The withdrawal was followed by a recommendation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), in January 2008, against the use of these products in this age group.7 Additionally, the manufacturers announced that they would voluntarily re-label all other pediatric OTC CCMs by replacing `ask a doctor before using in children under 2 years of age' with `do not use in children under 2 years of age'.8

The FDA is currently reviewing whether to recommend further restrictions on the labeling for OTC CCMs. Some agency and industry leaders have expressed concern that additional limits on marketing might paradoxically increase harm, if parents were to give excessive doses of products intended for older children or adults to small children.9

Poison center data can be used to evaluate childhood poisonings, including therapeutic errors and unintentional poisonings.10–12 This study assessed the number and severity of pediatric ingestions of OTC CCMs reported to the American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCCs) before and after the October 2007 withdrawal of these products marketed for children under the age of 2 years. To examine whether the withdrawal had an impact outside the target population, data on children 2–5 years were also evaluated. Lack of availability of OTC CCMs on the market should result in decreased availability and limited accessibility in households. The primary hypothesis is that decreased availability of OTC CCMs in households will reduce the number of therapeutic errors and unintentional poisonings both inside and outside the population targeted by the withdrawal. The secondary hypothesis is that the severity of outcomes associated with therapeutic errors involving OTC CCMs in children under 2 years will increase as parents treat these children with products intended for older children.

METHODS

The AAPCC National Poison Data System (NPDS), which covers the entire U.S. population, was analyzed for cases of pediatric ingestions of OTC CCMs. Data from 1 July 2005 to 31 December 2008 were included. The pre-withdrawal period was 1 July 2005–31 September 2007 (27 months) and the post-withdrawal period was 1 October 2007–31 December 2008 (15 months). For secular comparison, the total number of therapeutic errors reported to AAPCC NPDS in these age groups during the same timeframe was obtained. The University of Maryland-Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that the study did not require IRB review.

Data collected on cases include patient demographics, substance(s), reason for exposure, clinical effects, treatment, and outcome. Cases are calls to poison centers from multiple sources including the public, health care providers, and medical examiners, with the majority from the public. Case information is collected in real time, no retroactive data reclassification occurs. Children younger than 6 years of age were selected because this group corresponds to a database breakpoint. NPDS was queried for oral combination OTC CCMs because these products were the objects of the withdrawal. Cases coded as unintentional general or therapeutic error only were included. NPDS uses the term unintentional general for accidental exposures and these ingestions are referred to as `unintentional poisonings' in this study. NPDS uses the term `therapeutic error' for unintentional deviation from a proper therapeutic regimen that results in wrong dose, drug, route, or administration to the wrong person. More information on the reporting process, data fields, and population characterization of the AAPCC NPDS database are explained elsewhere.13

Poison centers follow all cases to completion and record as precise an outcome as possible. The outcomes are based on clinical effects using the following NPDS coding classification: no effect, minor effect (mild signs or symptoms which resolved rapidly), moderate effect (signs or symptoms that were more pronounced, usually requiring treatment), major effect (signs or symptoms that were life-threatening or resulted in significant residual disability), or death. Cases not followed to a known medical outcome or lost to follow-up are classified by one of following three definitions: not followed—judged as nontoxic exposure, not followed—minimal clinical effects possible, or unable to follow—judged as potentially toxic exposure.

Data were received from AAPCC NPDS for years 2005 through 2008 in Microsoft 2003 Access format. Each record in the dataset represents an individual case. Using Crystal Reports 2008, data were extracted and records were grouped using the following criteria: age (<2 or 2–5 years), reason (therapeutic error or unintentional poisoning), quarterly date range (i.e. 3 month intervals) and outcome. Total case counts were determined. Rates per 100 000 per 3-months by age group and type of poisoning were calculated using U.S. census data for the first month of each quarter as the denominator. U.S. Census Bureau data were accessed at http://www.census.gov/popest/national/asrh/2007-nat-res.html. Annual rates are reported as number of cases per 100 000 person-years with 95% confidence intervals. Mean rates pre- and post-withdrawal periods were calculated using a quasi-Poisson regression. (Poisson regression could not be used as the data demonstrated over-dispersion) Initial models were adjusted for period (pre- vs. post-withdrawal) and month to account for seasonal variation in poisoning. Month was not significant in any model, made little difference in the results, and was not included in the models reported below. Distribution of outcomes was analyzed using χ2-square. All reported p-values are two-sided. Analyses were performed with R 2.10.0 and SigmaStat 3.1.

RESULTS

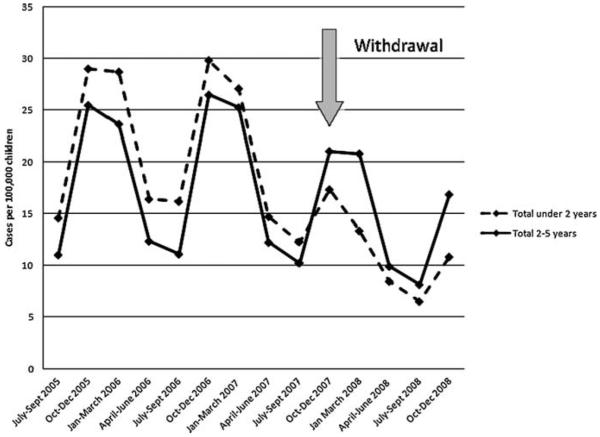

The mean annual rate of therapeutic errors involving OTC CCMs post-withdrawal, in children less than two-years of age, 45.2/100 000 (95%CI 30.7–66.6) was 54% of the rate pre-withdrawal, 83.8/100 000 (95%CI 67.6–104.0). The decrease was statistically significant p < 0.02. There was no significant difference in therapeutic errors for children 2–5 years of age, post-withdrawal rate 61.4/100 000 (42.2–89.4) vs. pre-withdrawal 70.2/100 000 (53.9–91.3), p < 0.58. For comparison, rates of therapeutic errors involving drugs/products not affected by the withdrawal remained constant at approximately 5% of total exposures reported to poison centers in children under 2 years during the pre- and post-withdrawal periods (not shown). Figure 1 illustrates the rates of therapeutic errors in three month intervals in children under 2 and 2–5 years, demonstrating the abrupt decline in rates following the withdrawal in children under 2 years.

Figure 1.

Rates of therapeutic errors involving over-the-counter cough and cold medications in children younger than 6 years of age, in quarterly intervals

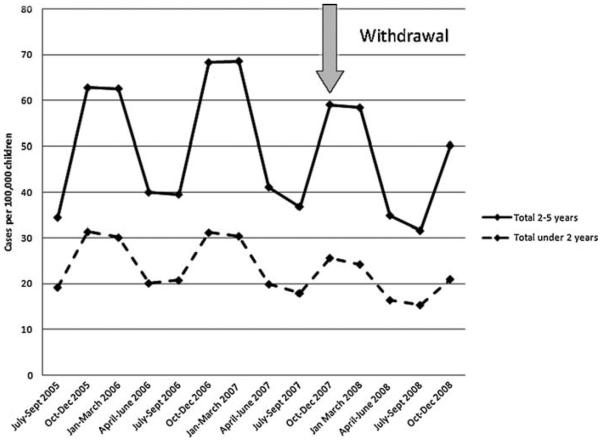

There were no significant differences in unintentional poisoning rates pre- and post-withdrawal in children less than 2-years of age or 2–5 years of age, rates post-withdrawal 82.1/100 000 (66.0–102.2) vs. pre-withdrawal 98.3/100 000 (84.4–114.3), p < 0.21 in younger children and pre-withdrawal 187.2/100 000 (145.1–241.5) vs. 201.8/100 000 (167.8–242.6) post-withdrawal, p < 0.65 respectively. Figure 2 illustrates the rates of unintentional poisonings per 3 months in children under 2 and 2–5 years.

Figure 2.

Rates of unintentional poisonings involving over-the-counter cough and cold medications in children younger than 6 years of age, in quarterly intervals

Comparing the pre-withdrawal with post-withdrawal period, there was a statistically significant difference in distribution of outcomes from therapeutic errors in children under 2 years (p < 0.001). An overall decrease in outcome severity was reported which was primarily driven by an increase in children with `no effect'. There was no difference in the frequency of severe outcomes. There were two deaths associated with therapeutic errors, one in the pre-withdrawal and one in the post-withdrawal periods. Both deaths occurred in children under 1 year of age.

DISCUSSION

Poison center data are a useful tool for evaluating pediatric exposures, especially exposures to OTC CCMs and lend themselves well to longitudinal analyses of these types of exposures. Annually AAPCC NPDS reports on 1.2 million exposures in children under the age of 6 years including approximately 1 million unintentional poisonings and 70 000 therapeutic errors.13,14 Prior to the withdrawal 4% of unintentional poisonings and 28% of therapeutic errors reported to AAPCC NPDS in children under 6 years of age involved OTC CCMs.14

The primary research hypothesis was that October 2007 withdrawal of pediatric OTC CCMs would reduce the number of therapeutic errors and unintentional poisonings reported to the AAPCC in children inside and outside the target population. The reasons for this across-the-board hypothesis is that the withdrawal might lead parents to question the use of these products in all their young children, not just children under 2 years of age. Also, the relative absence of these products from the household could decrease unintentional poisonings in both age groups.

A significant reduction in rates of therapeutic errors reported to AAPCC NPDS followed the withdrawal of OTC CCMs in children under 2 years of age. Figure 1 illustrates that the major decline in rates started in the fourth quarter of 2007, coinciding with October 2007 withdrawal. This reduction occurred as the rates of therapeutic errors involving all other products remained unchanged in these young children. These data challenge assertions that the withdrawal of these specific pediatric formulations would lead more parents to administer products intended for older populations to their younger children leading to more therapeutic errors.

This decline was likely due to the removal of products explicitly intended for this age group, as they seem to temporally coincide. Alternatively, rates of therapeutic errors in children under 2 years of age may have declined for other reasons. Publicity regarding the dangers of using OTC CCMs in young children might make parents reticent to call the poison center. Parents with newly limited options may have turned to medications intended for older age groups, without reporting this to a poison center. However, opposite behaviors have been observed as poison center call volume is reported to increase when a product recall, withdrawal or threat is involved.13,15–17

According to the CDC, the 2007–2008 flu season was more severe than the previous 3 years; it started mid-December 2007 and ended mid-May 2008, coinciding with the post-withdrawal period in this study.18 The significant decrease in rates of therapeutic errors involving OTC CCMs during a period of severe flu make these findings even more compelling.

No significant reduction in rates of unintentional poisonings from OTC CCMs was found in children under 2 years of age. In addition, no significant reduction in rates of therapeutic errors and unintentional poisonings were found in children age 2–5 years. These findings suggest that the withdrawal may not have influenced errors associated with parental administration of OTC CCMs to 2–5 year olds. They also suggest that availability/accessibility remained generally unchanged, as unintentional poisonings continued to occur with similar frequency in both age groups. These data are contrary to the research hypothesis and illustrate clearly that the targeted withdrawal had a targeted impact, without repercussions in other age groups or for other types of exposures. Regulatory agencies should consider these findings as they review placing further restrictions on products, especially OTC products.

Figures 1 and 2 both illustrate well the seasonal variability in rates of OTC CCMs exposures over time. Both figures show peak rates during winter months and nadir during the summer months. The seasonal variability reassures us that the data are correct.

The secondary research hypothesis was that the severity of outcomes associated with therapeutic errors involving OTC CCMs would increase as parents treat young children with products intended for older age groups. Comparing the pre- to the post-withdrawal periods, there was no difference in the frequency of serious outcomes from therapeutic errors in children under 2 years of age. These data address the concerns that administration of OTC CCMs intended for older populations to younger children would result in more emergency department visits, more hospitalizations, more acute care and ultimately worse outcomes. Industry concerns that restrictions on these products would lead to more harm appear unfounded.

A limitation of this study is the fact that reporting to poison centers is voluntary, introducing a possible reporting or selection bias. Evaluation of outcome severity is limited since not all cases are followed to a known outcome.

CONCLUSION

A significant drop in annual rates of therapeutic errors in children under the age of 2 years followed the voluntary withdrawal of OTC CCMs intended for this age group. Concerns that withdrawal of pediatric medications would paradoxically increase poisonings from parents giving products intended for older age groups to young children are not supported.

KEY POINTS

There is a lack of evidence supporting the efficacy of over-the-counter cough and cold medications (OTC CCMs) in young children. Additionally, there are reports of significant associated adverse effects, including death.

In October 2007, OTC CCMs labeled for use in children under 2 years of age were voluntarily withdrawn. This withdrawal raised concerns that parents with newly limited options would administer products intended for older children or adults to young children resulting in more therapeutic errors and more severe outcomes.

Rates of therapeutic errors involving OTC CCMs in children under age 2 years reported to poison centers decreased 54% after the voluntary withdrawal.

Frequency of severe outcomes resulting from therapeutic errors in children under age 2 years remained unchanged after the withdrawal.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Larry Gonzales, BS for his assistance with data analysis and Julie Spangler, MS for her assistance with preparing the figures. Both are affiliated with the Maryland Poison Center at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The American Association of Poison Control Centers (AAPCC; hppt://www.aapcc.org/) maintains the national database of information logged by the U.S. Poison Control Centers (PCCs). Case records in this database are from self-reported calls: they reflect only information provided when the public or healthcare professionals report an actual or potential exposure to a substance (e.g., an ingestion, inhalation, or topical exposure, etc.), or request information/educational materials. Exposures do not necessarily represent a poisoning or overdose. The AAPCC is not able to completely verify the accuracy of every report made to member centers. Additional exposures may go unreported to PCCs and data referenced from the AAPCC should not be construed to represent the complete incidence of national exposures to any substance(s).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES The authors have no financial disclosures.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vernacchio L, Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Mitchell AA. Cough and cold medication use by US children, 1999–2006: results for the Slone survey. Pediatrics. 2008;122(2):e323–e329. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0498. DOI:10.1542/peds.2008-0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Drugs Use of codeine- and dextromethorphan-containing cough remedies in children. Pediatrics. 1997;99(6):918–920. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.6.918. DOI:10.1542/peds.99.6.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang AB, Glomb WB. Guidelines for evaluating chronic cough in pediatrics: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1 Suppl):260S–283S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.260S. DOI:10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.260S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Infant deaths associated with cough and cold medications–two states, 2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56(1):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.FDA . Nonprescription Drug Advisory Committee Meeting: Cold, Cough, Allergy, Bronchodilator, Antiasthmatic Drug Products for the Over-the-counter Human Use (Memorandum) FDA, Division of Drug Risk Evaluation; Rockville: [Accessed on 16 January 2009]. 2007. p. 29. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/Drug-Safety/PublicHealthAdvisories/ucm051282.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Consumer Healthcare Products Association . Makers of OTC cough and cold medicines announce voluntary withdrawal of oral infant medicines. Washington, DC: [Accessed on 23 December 2008]. http://www.chpa-info.org/10_11_07.OralInfantMedicines.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 7.FDA . Public Health Advisory: nonprescription cough and cold medicine use in children. FDA CDER; Rockville: [Accessed on 23 December 2008]. 2008. http://www.fda.gov/Cder/drug/advisory/cough_cold_2008.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Consumer Healthcare Products Association [Accessed on 29 April 2009];Pediatric oral cough and cold medicines. http://www.chpa-info.org/media/resources/r_4519.pdf#search=%22pediatric%22.

- 9.FDA Over the counter cough and cold medications for pediatric use; notice of public hearing. Fed Regist. 2008;73(165):50033–50036. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tenenbein M. Unit-dose packaging of iron supplements and reduction of iron poisoning in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:557–560. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.6.557. DOI:10.1001/archpedi.159.6.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benson BE, Spyker DA, Troutman WG, Watson WA. TESS-based dose-response using pediatric clonidine exposures. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2006;213(2):145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.10.009. DOI:10.1016/j.taap.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Litovitz T, Manoguerra A. Comparison of pediatric poisoning hazards: an analysis of 3.8 million exposure incidents. A report from the American Association of Poison Control Centers. Pediatrics. 1992;89:999–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, Green JL, Rumack BH, Giffin SL. 2008 Annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 26th Annual report. Clin Toxicol. 2009;47:911–1084. doi: 10.3109/15563650903438566. DOI:10.3109/15563650903438566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR, Jr, Green JL, Rumack BH, Heard SE. 2006 annual report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS) Clin Toxicol. 2007;45:815–917. doi: 10.1080/15563650701754763. DOI:10.1080/15563650701754763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mrvos R, Walters D, Krenzelok EP. The media's influence on a poison center's call volume. Vet Human Toxicol. 1999;41(5):329–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.LoVecchio F, Katz K, Watts Pitera A. Media influence on poison center volume after 11 September 2001. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2004;19(2):185. doi: 10.1017/s1049023x00001722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Acute respiratory illness linked to use of aerosol leather conditioner—Oregon, December 1992. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1993;41(52–53):965–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Flu season summary (30 September 2007–17 May 2008) Atlanta: [Accessed on 26 April 2009]. http://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/qa/season.htm. [Google Scholar]