Abstract

The ElderSmile clinical program was initiated in northern Manhattan in 2006. ElderSmile is a comprehensive community-based program offering education, screening and treatment services for seniors in impoverished communities. Originally focused on oral health, ElderSmile was expanded in 2010 to include diabetes and hypertension education and screening. More than 1,000 elders have participated in the expanded program to date. Quantitative and qualitative findings support a role for dental professionals in screening for these primary care sensitive conditions.

Recent U.S. national estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicate that 29.1 million people, or 9.3 percent of the population, have diabetes. Of those with diabetes, roughly one-quarter or 8 million people are undiagnosed.1 In addition to severe complications with general health and metabolism, diabetes may have a marked impact on the oral cavity, leading to xerostomia, coronal and root caries and altered tooth eruption.2 Moreover, diabetes is an established risk factor for periodontal disease.2 Finally, emerging evidence has demonstrated a link between diabetes and tooth loss, which is especially concerning for older adults, as poor dentition can negatively impact both quality of life3 and nutritional status.4

With regard to the scientific evidence from the U.S., a published analysis of 2003-2004 National Health Examination and Nutrition Survey (NHANES) data revealed that compared to adults aged 50 and older (older adults) without diabetes, older adults with diabetes had higher numbers of missing teeth and were more than twice as likely to be edentulous.5 Similarly, using a population-based sample of Rhode Island adults, middle-aged persons with diabetes were more likely to have missing teeth and to be edentulous than persons without diabetes.6 Evidence also exists in the international literature that diabetes is associated with more tooth loss and poorer periodontal health.7-10 Further, a recent Korean study found that the relationship between diabetes and tooth loss was stronger at older ages.10

Because the scientific evidence suggests a bidirectional relationship between diabetes and periodontal disease, studies have also evaluated the oral manifestations of periodontal disease in people with diabetes. For example, in a sample of persons with previously undiagnosed diabetes, it was found that persons with newly diagnosed prediabetes had higher numbers of missing teeth and higher percentages of sites with bleeding on probing and deep periodontal pockets when compared with healthy individuals.11 Moreover, all periodontal parameters, including numbers of missing teeth, were significantly related to duration of diabetes.11 Thus, poor periodontal health may aid in predicting diabetes status. In a second study with a sample of patients at risk for developing diabetes, it was found that having four or more missing teeth or 26 percent of teeth with deep pockets correctly identified more than 70 percent of people with prediabetes or diabetes; the addition of a glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) test increased the percentage of true positives to nearly 90 percent.12

The ElderSmile Clinical Program

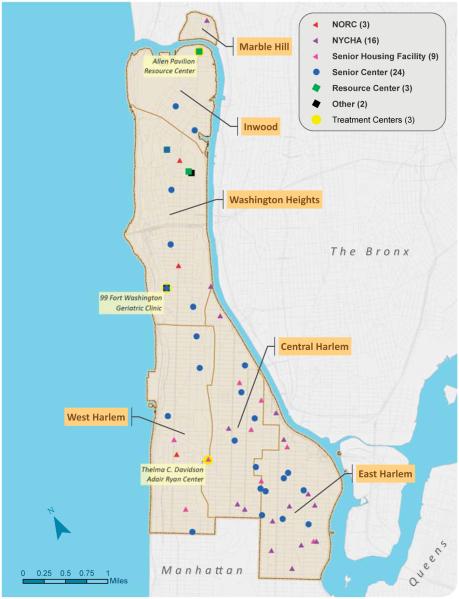

In 2006, the Columbia University College of Dental Medicine and its partners instituted the ElderSmile clinical program in the largely impoverished communities of Harlem and Washington Heights/Inwood in New York City to respond to the unmet need for oral health care in the older adult population (see the FIGURE for the current locations of program activities).13 Societal changes, including the aging of the U.S. population and the lack of routine dental service coverage under Medicare, had left many seniors unable to afford dental care.14 The long-term goal of the ElderSmile program is to improve access to and delivery of oral health care for seniors, both locally and more broadly. Details of the community-based oral health promotion activities, demonstrations of oral hygiene techniques and oral health examinations are provided elsewhere.13 Initial quantitative program results indicated substantial unmet dental needs in this largely Hispanic and African American elderly population.15,16 Moreover, many program participants were suspected of suffering from undiagnosed and untreated chronic health conditions when they presented for follow-up dental treatment at affiliated sites.

FIGURE.

Locations of the program activities of the ElderSmile network of the Columbia University College of Dental Medicine, which are largely centered in the northern Manhattan communities of Washington Heights/Inwood, Central Harlem and East Harlem, New York, as of October 2013.

This led to an expansion of the ElderSmile program in 2010 to integrate screening for diabetes and hypertension into its community-based oral health activities.17 Among the key findings from this program expansion were that racial/ethnic minority seniors were willing to be screened for primary care sensitive conditions by dental professionals.17 In addition, a high level of unrecognized disease was found, namely, 7.8 percent and 24.6 percent of ElderSmile participants had positive screening results for previously undiagnosed diabetes and hypertension, respectively.17 Accordingly, there is an important role for dental professionals to play in screening for primary care sensitive conditions and referring patients to primary health care providers for definitive diagnosis and treatment. In this way, dental teams may serve as trusted access points to facilitate diagnosis and treatment for chronic medical conditions. With tailoring to meet local needs, the ElderSmile program may represent a place-based model18 for oral and general health screening that works to address contextual and community-based factors that shape health, especially if policies to support the integration of public health, medical and dental services are realized.19

A Social Science Approach to Improve Oral Health Equity

As part of an NIH-funded study to understand the factors that serve as barriers to oral health and oral health care among seniors in northern Manhattan, semi-structured qualitative interviews20 were conducted with 16 key informants. The key informants were selected because they were individuals who work closely with older adults in senior centers and other naturally occurring retirement communities (NORCs) in northern Manhattan. Nearly all of the key informants were full-time senior center/NORC staff who served as senior center/NORC directors, activity directors, case managers or other staff who worked with older adults in the senior centers/NORCs. As such, they all spent extensive time interacting with older adults to determine the types of recreational, social and health care services that were of interest to the older adult populations they serve.

Providing social, educational and health-related activities and services is central to the mission of the senior centers.

To increase participation rates, interviews were conducted in the senior centers at times convenient for each key informant. The interviews lasted approximately one hour, were digitally recorded and later transcribed for analysis. One of the objectives of this study was to obtain insights from these key informants about whether they believed seniors would be receptive to the integration of general and oral health screening. To address this objective, the questions in the interviews explored the types of health-related programs that were currently offered to older adults in the senior centers, the relative importance of oral health as compared to hypertension and diabetes screening and whether seniors would be receptive to the integration of hypertension and diabetes screening into oral health services. Questions in the interview guide were designed and revised with feedback from the entire study team, including qualitative researchers, researchers who focus on the northern Manhattan community and ElderSmile dentists and staff who have firsthand knowledge and interactions with the key informants, their language and their understanding of dental care issues. After completing the first interview, additional revisions were made to further increase clarity for the participants and ensure the desired information was elicited. For the majority of questions, the interviewer sought to obtain specific examples of ideas or instances that the key informants had heard from the seniors they interacted with at their centers. In addition, key informants offered suggestions based on their experiences working with older adults. The complete interviews were read and responses on these topics were systematically extracted and examined to identify common themes in their responses. Below, we provide quotes that are representative of the key informants’ views on these issues.

Existing Health Care Services Available in Senior Centers

Providing social, educational and health-related activities and services is central to the mission of the senior centers. During the interviews, the center and activity directors of the senior centers and NORCs consistently reported that they partner with a large number of local hospitals and medical and nursing schools to provide health-related screenings and educational services. For example, a female African American director of a senior center in West Harlem told us about the services they provide to their primarily African American senior clients:

Participant (P): Harlem hospital comes in. They used to come in once a month to do diabetes, blood pressure screenings and flu shots during the season. What happened is they are short on staff and we were getting so few people (coming to the senior center). It just worked out that now they’re coming once every other month.

Although every senior center and NORC reported being able to offer blood pressure and blood sugar screenings, dental screenings were less frequently offered. For example, a Latina key informant who works as a peer worker in a largely Latino-serving senior center in East Harlem told us:

Interviewer (I): What are some of the health-related activities? Are there any kinds of health-related activities that are offered at the senior center?

Participant (P): We do get someone from Mount Sinai (hospital) once in a while to check blood pressure because we have a lot of seniors with high blood pressure. So they come and they check, just to make sure that their pressure is okay. We have most of the insurance companies come over to speak to the seniors about their health. We make sure that everyone knows that you have to have a flu shot. Because that’s important to them.

I: Have you ever had any kind of oral health, either educational or services, come in? Any kind of dental or oral health activities?

P: Not that I recall. But I’m only here three days a week. I don’t think we’ve had anything about oral health, which is very important.

Several of the senior center staff commented that oral health was a topic that they had not thought to offer to seniors, but that the interview had increased their awareness of the topic and they would be willing to invite the ElderSmile program to come to their centers. For example, the Latina director of another senior center in East Harlem that serves the Latino seniors in that area told us:

P: This material based on oral health, it hit me that we don’t really do much for that. I believe I had one — I’ve been here a year and a couple months. I think once we had a workshop about oral health. It’s something that I don’t know if I should reach out to more organizations that are specifically aimed to teach seniors this, or if more dentists should be reaching out to this population to educate them a little bit more about oral health.

However, for the key informants whose senior center had participated in the ElderSmile program activities, they were highly enthusiastic about the program and felt that the seniors were as well. For example, the Latina manager of a NORC that serves an ethnically diverse population of seniors in Washington Heights told us:

P: We are fortunate that we have this relationship with ElderSmile, which is great. Because when I worked elsewhere, I had to work with the local hospital to bring in someone to do oral screenings.

I: Is your impression that oral health and the importance of oral health is something that the seniors appreciate or see as needed or valuable?

P: Well, I think that when we bring it here, certainly, they very much appreciate it, because now we’re facilitating access. They don’t have to venture out. There are those who have their own relationship with their own dentist and don’t need us to bring in the resource. But when we bring in the resource, we do find that we have a good turnout. Especially, I find that having the combination of the education piece, in addition to an actual dentist seeing them, is really important.

Perceived Importance of Hypertension and Glucose Monitoring Relative to Oral Health Care

One of the most consistent reports from key informants was that seniors view monitoring their blood pressure and blood sugar as far more important than oral health care. Indeed, nearly all key informants reported that certain older adults felt that they could do without regular oral health care and could even live without teeth. For example, a Latina key informant who worked as the activities coordinator for a senior center that serves a mixed group of Latino and African American seniors in West Harlem reported that although half of the seniors explicitly seek oral health care, the other half do not, simply because it is something that they feel they can live without. She reported:

I: How important is oral health to most of the seniors you serve here?

P: Half of my seniors, they see it as important, but half of the other ones, they don’t care.

I: How often do you think most of your seniors go to the dentist?

P: Half of my seniors go twice a year. The other ones, I don’t think they go at all.

I: You mentioned that you have Harlem Hospital come in and do diabetes screenings and blood pressure screenings. Do you think the seniors see that as more important than their dental health?

P: Yes.

I: Why do you think that is?

P: They think they can live without teeth, but their health is more important for them.

Participants reported a variety of reasons why they thought seniors viewed oral health care as relatively unimportant in comparison to blood pressure and blood sugar monitoring. The key informants often reported that seniors viewed blood pressure and blood sugar monitoring as important because they believed ignoring one’s blood pressure and blood sugar could have potentially lethal consequences. Therefore, they regularly accepted or even sought out opportunities to have their blood pressure and blood sugar checked. In contrast, many reported that seniors viewed oral health care as something they could easily postpone or do without altogether. For example, a Latina key informant who coordinates the activities at a NORC that predominantly serves Latino seniors in Washington Heights told us:

I: Do the seniors see that as something that’s important?

P: Oh yes, very.

I: Why do you think that is?

P: I think that because there’s such a high concentration of seniors around this area who have diabetes and hypertension — I feel that our seniors are really on top of that. They really know that they need to take care of it because many times they go through episodes. If you don’t take care of your high blood pressure, you know you will end up in the hospital. That happens to a lot of seniors. Clients who have diabetes know that they’re going to have to go to the hospital, too. That’s not something you can just live with or take lightly, like a dental appointment. I can say, “Oh I could spend a year without going to the dentist. I’m fine.” Not with high blood pressure and diabetes or something like that.

I: So they see that as more important than going to the dentist?

P: I think so. I see that, yeah.

Similar views were also reported by a Latina key informant who works with a diverse group of seniors in a NORC in Washington Heights. Specifically, she suggested that seniors recognized that the day-to-day fluctuations in blood pressure and blood sugar required regular monitoring. In contrast, seniors believed oral health care was less important and therefore was not regularly monitored unless there was a critical oral health problem that needed to be addressed. She told us:

P: I think that if anything, I think that will probably be one of the top problems, that there is not consistent follow-up. … You may let it fall by the wayside. You have other important events, your medical care list, and your this, and your heart and your that. That’s the one [dental care] that you say, “You know what? I can push this one off.” Then over time, you don’t go. … I think because their blood pressure fluctuates day to day, they’re very mindful. Diabetes, the sugars, knowing your A1Cs, whatever it is. Sugars fluctuate. … They’re always mindful of their pressure, their sugar levels. I think with dental care, again, unless it’s something that’s right there and really bothering them or chronic, they may push it to the side and not be as concerned about it.

Other participants reported that the lack of perceived importance of oral health care might be reflective of a general lack of knowledge about the importance of oral health vis-a-vis overall health. Indeed, a Caucasian female senior center director who worked with a large Latino population in Washington Heights reported that this lack of perceived importance of oral health on overall health was not just an issue for seniors, but for most people. As such, most people, including seniors, view oral health care as less important than blood pressure and blood sugar monitoring. She reported:

I: I know you mentioned that you have services come in terms of their blood sugar and their blood pressure. Do you think the seniors see that as important and maybe more important than their oral health?

P: I don’t think that most people, much less seniors, understand how much you can tell about somebody’s overall health from the mouth. I don’t think it’s a senior-specific issue. I think it’s a lack of understanding of many about the mouth’s place in the body.

I: In terms of the seniors, do they see blood pressure, blood sugar as maybe a more important thing for them to take care of or have checked?

P: I just think it gets more focus, so it’s important because they get a lot of talk about it. … It’s not on their radar as a must-do thing.

I: So it’s just perceived importance.

P: Yeah. It just doesn’t have that importance.

A common reason suggested by our participants for why seniors view oral health care as less important than blood pressure and blood sugar monitoring was because of the greater attention that hypertension and diabetes receive as serious health conditions. As noted earlier, all of the senior centers and NORCs offered routine screening for hypertension and diabetes, but oral health screenings were less frequent. For example, an African American female participant who directs a large NORC that serves a predominantly African American senior population in Central Harlem reported that the difference in importance was because of the additional attention that blood pressure and blood sugar monitoring get relative to oral health care. She told us:

I: Do they see the blood sugar and the blood pressure check as more important than having their teeth or gums checked?

P: Yes.

I: Why do you think that is?

P: Because that’s the way it’s been supported. That’s the way it’s been presented. Even if you are employed and you get insurance — insurances normally don’t give you proper dental coverage. What message is that sending to people? It’s not something that’s just for seniors. I think it happens through life. They’ve been conditioned. They’ve learned that this is something that they can put off because they’ve done it for a long time.

Perceived Acceptability of Glucose and Hypertension Screening by Dentists

Based on these consistent reports that seniors viewed blood pressure and blood sugar monitoring as important and regularly accepted opportunities to have them checked, we asked the participants whether they thought seniors would be interested in or accepting of a dentist providing these health screening services as part of a regular dental care visit. Many of our participants thought that the addition of these screenings to a dental visit would be very attractive to seniors. For example, the African American female director of a senior center serving largely African American seniors in West Harlem told us:

I: If a dentist were to also do a blood pressure check and a blood sugar check as part of their dental cleaning or dental exam, do you think that is something that the seniors would like?

P: Absolutely! They love having those screenings.

I: Why do you think that is?

P: People just want to know they are okay. Especially when they get up in age. Before anything gets really bad. I think it gives them a sense of comfort.

I: Do you think having those additional screenings as part of their dental screening would make them more likely to go to the dentist?

P: I think so.

I: Why do you think that?

P: Well, because not only would they get the things they are used to getting done, but now they would be getting something additional that’s also good for them. I think they would be willing to go for it.

When we asked participants why they thought seniors would be interested in dentists offering these added services, they reported a number of different reasons. Some participants thought that seniors, especially those with mobility or travel concerns, would particularly like the opportunity to receive multiple services at one time, in a single location, to save them additional trips. For example, a Latina key informant who works with a primarily Latino population of seniors living in a NORC in Washington Heights told us:

I: If the dentists out in the community were to do a blood pressure and a blood sugar check as part of their visit, do you think that is something that the seniors would like?

P: Yes. I think so.

I: Why do you think that is?

P: They would come for three things at once. I see that as very important to them because when Harlem Hospital comes, they’re like, “Oh, good. I could do this and I could do that.” There’s two things they could do when they come. Sometimes we even have vision. Sometimes they’re doing three things at once. They have the blood pressure, the diabetes and the vision. They see that they could come here and do three things at once.

I: So if they could have dental as well?

P: Yes, I think they’d definitely like it.

I: Do you think that would make them more likely to go to the dentist?

P: Yes, I think so.

I: Why do you think that is?

P: I think they see that as very important. Like I said, if you have a couple of things they could do at once, right away they would be like, “Oh, I could do three things?” I think it’s definitely something that they would like.

Another Latina key informant working with a diverse group of seniors in a NORC in Washington Heights also reported that she thought the “three-in-one” services would motivate seniors to go to the dentist, but she also thought it would help seniors understand that oral health and physical health were intertwined. She told us:

I: Do you think that would be something that would motivate the seniors to go to the dentist more?

P: I think they may be more receptive to a model like that because it’s a one-shot deal, three-in-one versus go to the doctor, go to this, go to that. That might actually serve to motivate them more to go. Especially to correlate the health care because I think right now they see it as separate. They don’t see it as related to their overall well-being. They do understand the effects of bad teeth, but they don’t see how it could also affect their health overall. I think that needs to be really emphasized to people.

Similar thoughts were reported by another key informant, an African American woman who directs a NORC serving African American seniors in Central Harlem, who felt that it would help seniors to understand that oral health is important, not just general health. She told us:

I: If a dentist in the community were to offer a blood pressure and a blood sugar check as part of their regular dental visit, do you think that would be something that the seniors would like?

P: Yes. That’s interesting. I think that if you include the dental check with other screens, then you would begin to change the thinking about the importance of good oral health.

Another reason participants thought seniors would very much like to receive blood pressure and blood sugar screenings as part of their regular dental visits is because they thought that inclusion of these screenings for free (or at least without an additional copay and a separate visit) would be particularly attractive to seniors on a fixed income. For example, a Latina key informant who directs a senior center in East Harlem that serves largely Latino seniors reported how seniors loved to get free blood pressure screenings and other free gifts. She thought this would increase the likelihood of seniors going to the dentist, and told us:

P: If you want people to go to the dentist, especially seniors, give them something for free. Give them a toothbrush or a little mini toothpaste because that will get their attention. They know that if they sit down and talk to you they’re going get a gift out of it. Blood pressure screenings, they love it because it’s free.

I: Do you think the inclusion of blood pressure and blood sugar screenings would make it more likely or less likely for them to go to the dentist?

P: To go to the dentist’s office? I mean, if it is included in the regular check I don’t think they’ll mind. Because they’re like, “Oh, I get one more thing just for coming to the dentist.” I don’t think they’ll have a problem with it.

Similar reports of how additional services would serve as an incentive to get them to visit the dentist more were reported by several participants. For example, an African American woman who directs a senior center in West Harlem serving a primarily Latino group of seniors reported:

I: What would you offer to try to get them to go to the dentist?

P: Well, seniors like incentives. They like to get things. They like to get something free. Perhaps if they offered something free. Maybe that will help them come in.

I: If the dentist were to offer blood pressure and blood sugar checks, do you think that would help encourage them to go to the dentist more often?

P: They might. They might say, “Oh, well my dentist, I know he’s going to check my blood sugar, he’s going do my pressure. That might be useful.”

Discussion

The ElderSmile clinical program successfully incorporated education, screening and referral for diabetes and hypertension into its service delivery offerings. Quantitative findings previously reported and qualitative findings reported here support a role for dental professionals in screening for these primary care sensitive conditions. Among ElderSmile participants, there were many with high HbA1c levels and blood pressure readings that had no previous diagnosis by a physician of diabetes or hypertension, as well as many with high readings that were previously diagnosed. Findings from these qualitative data include that senior center/NORC staff who work with seniors in northern Manhattan believe that there will be high interest among seniors in having the dental team provide screening and monitoring for primary care sensitive conditions. They also believe that providing these services could motivate more seniors to visit the dentist. Linking primary care and oral health care together in accessible locations can identify seniors in need of better monitoring and treatment for both, and promote a more holistic view of their health and well-being.

Linking primary care and oral health care together in accessible locations can identify seniors in need of better monitoring and treatment for both.

Although few dental practices have integrated routine diabetes and hypertension screenings and monitoring into their practices, there is evidence that this may be advantageous from a variety of perspectives. First, improved diagnosis and control of diabetes may be achieved through implementation of blood glucose testing in community dental practices.21 Second, receipt of dental care may reduce diabetes-specific health care utilization.22 Third, screening for hypertension before dental procedures is not only essential to patient safety, but may also result in economic benefits to the health care system.23 A number of models have been proposed,24,25 even as state-based scope of practice laws and public and private insurance reimbursement policies remain to be worked out. Indeed, surveys of dental practices have found that the majority of dentists believe it is important to conduct chairside screening for diabetes and hypertension, view it as worth routine implementation and did not perceive insurance coverage or cost to be significant barriers.21,26 Feasibility trials have documented that dentists in general and specialty dental practices can conduct screenings.21,27 Furthermore, as dental schools and large dental clinics implement and bill Medicaid for the meaningful use incentives available for utilizing electronic health records, more dentists will gain confidence in performing primary care screening chairside.28

The qualitative data presented here from key informants who provide services to older adults in senior centers provide additional streams of evidence about the importance, acceptability and desirability of integrating diabetes and hypertension screening and monitoring into oral health care. It was the majority view of our participants that older adults deem oral health care to be less important than screening and monitoring for blood pressure and blood sugar. Accordingly, many participants also believed that older adults view dental visits as care they can delay or do without. Together, these findings — that older adults infrequently seek oral health care and view it as less important than general health care — demand creative and pragmatic social marketing strategies for better ensuring that older adults gain the oral health care they desperately need.29

Importantly, our qualitative findings suggest several potential avenues for increasing the receipt of oral health care by older adults. Many of our key informants believed that combining diabetes and hypertension screening and monitoring into oral health care would not only be highly acceptable to older adults, but would also make it more likely that they would obtain needed oral health care. Further, they offered several suggestions as to why they thought integrated health care services would be attractive to older adults, detailed next.

First, many participants believed that combined services would allow older adults to accomplish a variety of health care goals in a single visit, thereby avoiding travel to multiple offices to access each service separately. This may be particularly advantageous for seniors who have mobility difficulties.

Second, participants voiced the belief that many older adults living on a fixed income would be particularly attracted to receiving additional services for “free,” and that such additional free services would act as an incentive for obtaining oral health care. While such additional care services are not free to the provider and must currently be billed to an insurance carrier, the trend in health care is to move toward reimbursing for outcomes, not services.

Finally, participants also felt that bundling oral and general health care services together by providing them at a single site would have the benefit of increasing awareness among older adults of the connection between oral and general health. As such, it would likely serve, in the long run, to increase the perceived importance of oral health among older adults and thereby lead to better overall health for individuals and populations.

These qualitative data are limited in that they were provided by key informants who work with older adults, and therefore may not reflect the perspectives of older adults themselves. Nevertheless, these participants provide social, educational and health-related services to a largely low-income, racial/ethnic minority population of older adults. Accordingly, they were able to offer valuable feedback regarding their own views on what motivated older adults to attend the services and programs provided in their own senior centers. Likewise, these findings do not take into account the perspective of dental providers regarding their concerns about integrating general health services into their dental practices. Although formative research has explored the views of both dentists and patients in general,21,26 more implementation science needs to be conducted to understand how best to incorporate primary care screening at chairside into the diverse array of existing dental practices.

Conclusion

Taken together, these qualitative findings offer preliminary evidence that the integration of diabetes and hypertension screening and monitoring into routine oral health care would be both acceptable and attractive for older adults. This integration of care holds the potential to identify undiagnosed or unmanaged primary care sensitive conditions, while providing incentives and rationales for seeking ongoing preventive oral health care, a combination that may ultimately lead to better general and oral health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation and The Legacy Foundation, which provided major funding for the diabetes and hypertension educational and screening components of the ElderSmile program. The authors were supported in the research, analysis and writing of this research report by the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research of the National Institutes of Health through the project, “Integrating Social and Systems Science Approaches to Promote Oral Health Equity” (grant R01-DE023072). The authors thank Susan Kum for preparing the ElderSmile map shown in the figure.

Biographies

Stephen Marshall, DDS, MPH, is a dentist with public health training who has dedicated his career to the design and implementation of community-based programs for underserved populations including children and older adults.

Conflict of Interest

Disclosure: None reported.

Eric W. Schrimshaw, PhD, is a social/health psychologist who uses mixed-methods research to understand the influence of social relationships, support, stigma and disclosure on health behaviors and well-being.

Conflict of Interest

Disclosure: None reported.

Sara S. Metcalf, PhD, is a health geographer and systems scientist whose research models policies and social behaviors that promote community health, oral health equity and urban sustainability.

Conflict of Interest

Disclosure: None reported.

Ariel Port Greenblatt, DMD, MPH, is interested in using policy and practice to promote oral health equity across the life course.

Conflict of Interest

Disclosure: None reported.

Leydis De La Cruz, MA, has extensive expertise in community-based oral health programming for underserved populations, including racial/ethnic minority children and older adults.

Conflict of Interest

Disclosure: None reported.

Carol Kunzel, PhD, is a social-behavioral scientist with particular interests in dental community health, access to oral health care, dentist-patient relations and the translation of research findings into practice.

Conflict of Interest

Disclosure: None reported.

Mary E. Northridge, PhD, MPH, is a social epidemiologist devoted to utilizing a range of scientific and participatory approaches for advancing oral health equity at the local, state and national levels.

Conflict of Interest

Disclosure: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Diabetes Statistics Report: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States, 2014. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Atlanta: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamster IB, Kunzel C, Lalla E. Diabetes mellitus and oral health care: Time for the next step. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143(3):208–210. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang DL, Chan KC, Young BA. Poor oral health and quality of life in older U.S. adults with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(10):1782–1788. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iwasaki M, Taylor GW, Manz MC, et al. Oral health status: relationship to nutrient and food intake among 80-year-old Japanese adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2014;42(5):441–450. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel MH, Kumar JV, Moss ME. Diabetes and tooth loss: An analysis of data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2004. J Am Dent Assoc. 2013;144(5):478–485. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2013.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jiang Y, Okoro CA, Oh J, Fuller DL. Sociodemographic and health-related risk factors associated with tooth loss among adults in Rhode Island. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E45. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.110285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaur G, Holtfreter B, Rathmann W, Schwahn C, Wallaschofski H, Schipf S, Nauck M, Kocher T. Association between type 1 and type 2 diabetes with periodontal disease and tooth loss. J Clin Periodontol. 2009;36:765–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2009.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demmer RT, Holtfreter B, Desvarieux M, et al. The influence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes on periodontal disease progression: Prospective results from the Study of Health in Pomerania (SHIP) Diabetes Care. 2012;35(10):2036–2042. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim EK, Lee SG, Choi YH, et al. Association between diabetes-related factors and clinical periodontal parameters in type-2 diabetes mellitus. BMC Oral Health. 2013;13:64. doi: 10.1186/1472-6831-13-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung HY, Kim YG, Jin MU, Cho JH, Lee JM. Relationship of tooth mortality and implant treatment in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in Korean adults. J Adv Prosthodont. 2013;5(1):51–7. doi: 10.4047/jap.2013.5.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamster IB, Cheng B, Burkett S, Lalla E. Periodontal findings in individuals with newly identified prediabetes or diabetes mellitus. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:1055–1060. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lalla E, Cheng B, Kunzel C, Burkett S, Lamster IB. Dental findings and identification of undiagnosed hyperglycemia. J Dent Res. 2013;92(10):888–92. doi: 10.1177/0022034513502791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marshall S, Northridge ME, De La Cruz LD, Vaughan RD, O’Neil-Dunne J, Lamster IB. ElderSmile: A comprehensive approach to improving oral health for seniors. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):595–599. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamster IB. Oral health care services for older adults: A looming crisis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):699–702. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Northridge ME, Ue FV, Borrell LN, De La Cruz LD, Chakraborty B, Bodnar S, Marshall S, Lamster IB. Tooth loss and dental caries in community-dwelling older adults in northern Manhattan. Gerodontology. 2012;29(2):e464–e473. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2011.00502.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Northridge ME, Chakraborty B, Kunzel C, Metcalf S, Marshall S, Lamster IB. What contributes to self-rated oral health among community-dwelling older adults? Findings from the ElderSmile program. J Public Health Dent. 2012;72(3):235–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2012.00313.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall SE, Cheng B, Northridge ME, Kunzel C, Huang C, Lamster IB. Integrating oral and general health screening at senior centers for minority elders. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(6):1022–1025. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amaro H. The action is upstream: Place-based approaches for achieving population health and health equity. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):964. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Northridge ME, Yu C, Chakraborty B, Port A, Mark J, Golembeski C, Cheng B, Kunzel C, Metcalf SS, Marshall SE, Lamster IB. A community-based oral public health approach to promote health equity. Am J Public Health. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302562. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merton RK, Fiske M, Kendall PL. The Focused Interview: A Manual of Problems and Procedures. 2nd Free Press; New York: [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barasch A, Safford MM, Qvist V, Palmore R, Gesko D, Gilbert GG. Dental Practice-Based Research Network Collaborative Group. Random blood glucose testing in dental practice: A community-based feasibility study from The Dental Practice-Based Research Network. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143(3):262–269. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosen DA, Pihlstrom DJ, Snyder JJ, Shuster E. Assessing the association between receipt of dental care, diabetes control measures and health care utilization. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143(1):20–30. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nasseh K, Greenberg B, Vujicic M, Glick M. The effect of chairside chronic disease screenings by oral health professionals on health care costs. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(4):744–750. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamster IB, Eaves K. A model for dental practice in the 21st century. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1825–1830. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Northridge ME, Glick M, Metcalf SS, Shelley D. Public health support for the health home model. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(10):1818–1820. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenberg BL, Glick M, Frantsve-Hawley J, Kantor ML. Dentists’ attitudes toward chairside screening for medical conditions. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(1):52–62. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Genco RJ, Schifferle RE, Dunford RG, Falkner KL, Hsu WC, Balukjian J. Screening for diabetes mellitus in dental practices: A field trial. J Am Dent Assoc. 2014;145(1):57–64. doi: 10.14219/jada.2013.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kalenderian E, Walji M, Ramoni RB. “Meaningful use” of EHR in dental school clinics: How to benefit from the U.S. HITECH Act’s financial and quality improvement incentives. J Dent Educ. 2013;77(4):401–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Griffin SO, Jones JA, Brunson D, Griffin PM, Bailey WD. Burden of oral disease among older adults and implications for public health priorities. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(3):411–418. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]