Abstract

The aim of the present study was to examine the mediational effect of masculine gender role stress on the relation between adherence to dimensions of a hegemonic masculinity and male-to-female intimate partner physical aggression. Men’s history of heavy episodic drinking was also examined as a moderator of the proposed mediation effect. A sample of 392 heterosexual men from the southeastern United States who had been in an intimate relationship within the past year completed measures of hegemonic masculine norms (i.e., status, toughness, and antifemininity), masculine gender role stress, alcohol use patterns, and intimate partner physical aggression. Results indicated that the indirect effects of adherence to the antifemininity and toughness norms on physical aggression toward female intimate partners via masculine gender role stress were significant and marginal, respectively. A significant indirect effect of status was not detected. Moreover, subsequent analyses revealed that the indirect effects of antifemininity and toughness were significant only among men with a history of heavy episodic drinking. These findings suggest that heavy episodic drinking exacerbates a gender-relevant stress pathway for intimate partner aggression among men who adhere to specific norms of masculinity. Overall, results suggest that the proximal effect of heavy episodic drinking focuses men’s attention on gender-based schemas associated with antifemininity and toughness, which facilitates partner-directed aggression as a means to demonstrate these aspects of their masculinity. Implications for the intersection between men’s adherence to specific norms of hegemonic masculinity, cognitive appraisal of gender relevant situations, and characteristic patterns of alcohol consumption are discussed.

Keywords: Hegemonic Masculine Norms, Masculine Gender Role Stress, Alcohol, Domestic Violence

Introduction

A wealth of research has identified men’s adherence to a hegemonic masculinity as an important determinant of intimate partner aggression (for a review, see Moore and Stuart 2005). However, surprisingly absent from this literature are investigations of the extent to which men’s heavy alcohol use may affect these relations. This is remarkable given the established interrelationships among masculinity, alcohol use, and intimate partner aggression in North American samples (Iwamoto, Corbin, Lejuez, and MacPherson, 2014; Leonard 2005; McCreary, Newcomb, and Sadava 1999; Towns, Parker, and Chase 2012; Uy, Massoth, and Gottdiener 2014). Although variability exists across countries, extant literature drawn from myriad countries indicates that alcohol consumption is positively associated with the perpetration of aggression (World Health Organization 2007). Thus, understanding how alcohol use may affect the relation between masculinity and intimate partner aggression has broad implications. To address this gap in the literature, the present study proposes a theoretically-based model that simultaneously examines (1) masculine gender role stress as a mediator of the link between men’s endorsement of hegemonic masculine norms and their perpetration of physical aggression toward female intimate partners, and (2) heavy episodic drinking as a moderator of this mediational path. To examine these objectives, we analyzed self-report data from heterosexual men in the United States who had been in an intimate relationship within the past year using negative binomial regression, which has been shown to effectively handle non-linear count data that is common in violence research. These aims reflect an innovative integration of the masculinity and alcohol literatures to explain one mechanism by which men’s gender role adherence is associated with their perpetration of physical aggression toward their female intimate partners. As such, the present study represents an important step toward the development of an evidence base upon which future research and practice can seek to reduce intimate partner aggression.

The following sections will first review theory pertinent to the construction and demonstration of hegemonic masculinity and empirical support for these interrelationships. This review will conclude by applying a prominent theory of alcohol-related aggression (Alcohol Myopia Theory; Steele and Josephs 1990) to explain how heavy episodic drinking patterns influence links between men’s adherence to hegemonic masculinity, masculine gender role stress, and their perpetration of physical aggression toward their female intimate partners. Unless otherwise noted, this review includes studies from samples in the United States.

Hegemonic Masculinity and Gender Role Stress as Risk Factors for Partner Violence

It is well established that risk factors for intimate partner aggression operate across multiple ecological levels (Heise 1998; O’Leary, Smith Slep, and O’Leary 2007). Among the myriad determinants of intimate partner aggression identified in U.S. samples, masculinity has received significant attention (Moore and Stuart 2005; Wong, Steinfeldt, Speight, and Hickman 2010). Much of this work has conceptualized masculinity as a unidimensional construct to which men show individual variability. However, theorists have argued that multiple “masculinities” and dimensions of these masculinities exist, each of which are differentially associated with aggression (for a review, see Connell 2005). To this end, pertinent theory suggests that male-to-female aggression is often a product of socialization pressures to adhere to a hegemonic masculinity (O’Neil, Helms, Gable, David, and Wrightsman 1986) that legitimizes patriarchy and dominance over women (Connell and Messerschmidt 2005). In turn, adherence to specific dimensions of hegemonic masculinity reflects the degree to which men internalize and express cultural beliefs associated with various hegemonic masculine norms (Good, Borst, and Wallace 1994). Pertinent to heterosexual relationships, examples of individual-level demonstrations of such internalized beliefs include men’s maintenance of dominance, power, and control over women (Eisler 1995; Messerschmidt 1997; Pleck 1995), fear of femininity and emotional expression (O’Neil et al. 1986), and physical and emotional toughness (David and Brannon 1976).

These examples correspond nicely with a tripartite conceptualization of hegemonic masculinity put forth by Thompson and Pleck (1986), who identified three fundamental and distinct dimensions of hegemonic masculinity to which men vary in their adherence. These include: (a) status, which reflects men’s belief that they must gain the respect from others (b) toughness, which reflects men’s belief that they must appear aggressive and physically and emotionally strong, and (c) antifemininity, which reflects men’s belief that they should avoid stereotypically feminine behaviors. Extant literature indicates that when these and related norms are examined directly, they are positively associated with men’s self-report of generalized aggressive behavior (Thomas and Levant 2012), anger and hostility (Jakupcak, Tull, and Roemer 2005; McDermott, Schwartz, and Trevathan-Minnis 2012; Sinn 1997), and the perpetration of sexual (Locke and Mahalik 2005; Smith, Parrott, Swartout, and Tharp 2015; Truman, Tokar, and Fischer 1996; Zurbriggen 2000) and physical (Jakupcak, Lisak, and Roemer 2002; Santana, Raj, Decker, La Marche, and Silverman 2006) aggression toward female intimate partners. Nevertheless, literature on the putative dimensions of masculinity which facilitate men’s intimate partner aggression is still emerging; moreover, relevant moderating and mediating variables which explain this association have received limited attention.

Scholars posit that men’s adherence to various hegemonic masculine norms portends a risk for the perpetration of physical aggression toward intimate partners due to their experience of masculine gender role stress within contexts that challenge adherence to these norms, including intimate partner conflict situations (Eisler 1995; Moore and Stuart 2005; O’Neil and Harway 1997; Pleck 1995). Masculine gender role stress (Eisler and Skidmore 1987) is defined as the tendency to cognitively appraise gender relevant situations as threatening or stressful. These situations include gender relevant conflict or situations that require defense of personal and societal standards of a more hegemonic masculinity (Copenhaver, Lash, and Eisler 2000; Eisler and Skidmore 1987; Eisler, Franchina, Moore, Honeycutt, and Rhatigan 2000; Eisler, Skidmore, and Ward 1988; Lash, Eisler, and Schulnian 1990). Specific to intimate relationships, men who consistently exhibit these biased appraisal processes are more likely to feel threatened, use verbal aggression, experience negative affect (e.g., anger, anxiety), and attribute negative intent to female intimate partners during gender-relevant conflict situations (Franchina, Eisler, and Moore 2001; Moore and Stuart 2004). Not surprisingly, results across numerous studies support masculine gender role stress as a robust predictor of men’s perpetration of physical aggression toward female intimate partners (for a review, see Moore and Stuart 2005). Pertinent to the present study, extant research indicates that men’s adherence to hegemonic masculine norms is linked to their perpetration of physical aggression toward female intimate partners among those who also endorse higher, relative to lower, levels of masculine gender role stress (Cohn and Zeichner 2006; Jacupcak et al. 2002).

However, to our knowledge, research has yet to examine masculine gender role stress as a mechanism by which men’s adherence to hegemonic masculinity is associated with the perpetration of physical aggression toward their female partners. This is surprising for at least two reasons. First, masculine gender role stress has been conceptualized as a stable, experiential consequence of rigid hegemonic masculine norm adherence that is expressed in response to gender relevant situations (Jakupcak, Salters, Gratz, and Roemer 2003). Second, research indicates that men who endorse hegemonic masculine norms also report a global fear of emotion (Jakupcak et al. 2005; Jakupcak et al. 2003). Because masculine gender role stress has been shown to mediate the link between such fear and men’s perpetration of physical aggression toward their female intimate partners (Jakupcak et al. 2002), a similar mechanism is plausible for hegemonic masculine norms. This mechanism is consistent with extant literature which identifies cognitive processing biases as a risk factor for non-alcohol related (Eckhardt, Samper, Suhr, and Holtzworth-Munroe 2012; Persampiere, Poole, and Murphy 2014; Sippel and Marshall 2011) and alcohol-related intimate partner physical aggression (for a review, see Clements and Schumacher, 2010).

Heavy Episodic Drinking as a Risk Factor for Intimate Partner Physical Aggression

Recent work on the general aggression model (for a review, see Anderson and Bushman 2002) offers a framework which explains how co-occurring characteristics of the individual and situational context differentially facilitate physical aggression toward intimate partners (DeWall, Anderson, and Bushman 2011). Based on this model, factors that interfere with self-regulatory processes, such as alcohol consumption, are most likely to disrupt an individual’s appraisal of the situation and thus increase the likelihood of physical aggression toward intimates. To this end, the most prominent theories of alcohol-related aggression suggest that alcohol interferes with important self-regulatory processes by decreasing fear responses (Ito, Miller, and Pollock 1996; Pihl, Peterson, and Lau 1993), increasing physiological and psychological arousal (Giancola and Zeichner 1997; Graham, Wells, and West 1997), and disrupting higher-order cognitive functioning involved in the perception of cues and the regulation of behavior (Giancola 2004; Hull 1981; Pernanen 1976; Steele and Josephs 1990; Taylor and Leonard 1983).

One example of a self-regulatory risk factor for intimate partner aggression is men’s heavy episodic drinking, which has been observed in samples from the United States (Heyman, O’Leary, and Jouriles 1995; Leonard and Jacob 1997) as well as developed countries in North America, South America, Europe, the Middle East, New Zealand, and Asia (Hines and Straus 2007). Heavy episodic drinkers, relative to non-heavy episodic drinkers, experience a range of disruptions in self-regulatory processes such as poorer inhibitory control (Marczinski, Combs, and Fillmore 2007) and decision-making abilities (Goudriaan, Grekin, and Sher 2007). Importantly, men who consume high quantities of alcohol per drinking occasion are more likely to be intoxicated across time and contexts, relative to men who do not consume high quantities of alcohol per drinking occasion. As such, they possess a greater risk for alcohol-related disruption of self-regulatory processes during intimate partner conflict. To this end, a meta-analysis identified that, relative to other forms of alcohol consumption (e.g., frequency of drinking occasions), measures of heavy episodic drinking (e.g., binge drinking, heavy drinking) are the most robust predictors of physical aggression toward intimate partners (Foran and O’Leary 2008). Laboratory based studies similarly indicate that men who are heavy drinkers are at a greater risk for alcohol’s acute aggression-promoting effects (Parrott and Giancola 2006).

The association between heavy drinking and aggression may be explained by the most prominent and empirically supported model of alcohol-related aggression, Alcohol Myopia Theory (Steele and Josephs 1990). This theory posits that the pharmacological properties of alcohol facilitate aggression by narrowing attentional focus onto the most salient cues in an individual’s environment. By impairing attentional capacity, alcohol causes individuals to attend to environmental cues which are most salient and easiest to process. In intimate conflict situations, the cues which tend to be most salient are those which instigate aggression (e.g., provocation from an intimate partner), whereas the cues which tend to less salient are those which inhibit aggression (e.g., legal implications). As a result, heavy episodic drinking is likely to facilitate intimate partner aggression by narrowing an individual’s attention on provocative or threatening cues in the environment rather than non-provocative, inhibitory cues.

Theoretical Integration

Pertinent theory suggests that men who adhere to norms of hegemonic masculinity will perpetrate more physical aggression toward their intimate partners because they tend to appraise intimate partner conflict as threatening to their rigid masculine identity. However, in keeping with Alcohol Myopia Theory, this effect will be moderated by heavy drinking in as much as heavy drinkers are more likely to be intoxicated across contexts, including situations that involve intimate partner conflict and gender-relevant threats. Specifically, because heavy episodic drinkers will tend to be intoxicated during intimate conflict, they are hypothesized to allocate their attention such that they perceive and process only the most salient cues in their environment (e.g., provocation, appraisal of gender-relevant threat) to the exclusion of less salient inhibitory cues (e.g., non-aggressive norms that prohibit intimate partner aggression). In contrast, because non-heavy drinkers will tend to be sober during intimate conflict, they should retain the ability to focus attention on both instigatory and inhibitory cues in their environment.

The Present Study

The present investigation provides the first theory-based test of (1) masculine gender role stress as a mediator of the link between men’s endorsement of hegemonic masculine norms and their perpetration of physical aggression toward female intimate partners, and (2) heavy episodic drinking as a moderator of this mediational path. Hypothesis 1 posited that masculine gender role stress would mediate the association between men’s adherence to hegemonic masculine norms (i.e., status, toughness, and antifemininity) and their perpetration of physical aggression toward female intimate partners. Hypothesis 2 posited that these indirect effects would be stronger among men who evidenced a pattern of heavy episodic drinking relative to men who did not evidence a pattern of heavy drinking. Given that a paucity of literature has examined the independent correlations between adherence to specific traditional gender norms and men’s perpetration of physical aggression toward female partners, the proposed theory-based pathway and hypotheses were advanced for all three norms.

To test these predictions, negative binomial regression was utilized, which is an approach based on the Poisson distribution that is appropriate for non-linear data common in violence research (Atkins and Gallop 2007; Hilbe 2011; Swartout, Thompson, Koss, & Su in press). To test Hypothesis 1, (1) masculine gender role stress was regressed onto status, toughness, or antifemininity while controlling for the remaining two norms, (2) intimate partner physical aggression was regressed onto status, toughness, or antifemininity and masculine gender role stress while controlling for the other two norms, and (3) indirect effects of each norm on intimate partner physical aggression via masculine gender role stress were estimated. To test Hypothesis 2, (1) intimate partner physical aggression was regressed onto status, toughness, or antifemininity (while controlling for the other two norms), masculine gender role stress, heavy episodic drinking, and the Masculine Gender Role Stress X Heavy Episodic Drinking interaction term, (2) masculine gender role stress was regressed onto status, toughness, or antifemininity while controlling for the other two norms, and (3) the conditional indirect effect of a given male role norm on intimate partner aggression via masculine gender role stress was estimated. Each model was computed three times to test separately the effects of men’s adherence to each norm.

Method

This study utilized archival data drawn from the first phase of a larger two phase investigation on the effects of alcohol on aggression in men. This first phase involved the completion of a questionnaire battery, whereas the second phase involved an alcohol administration laboratory protocol. Thus, all participants who presented to the laboratory reported alcohol consumption during the past year (see below) and denied past or present drug or alcohol-related problems. The present hypotheses are novel, and the analytic plan was developed specifically to address these aims.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were 488 heterosexual male drinkers between the ages of 21 and 35 who were recruited from the metro-Atlanta community between 2009 and 2012 through Internet advertisements and local newspapers for a study “examining effects of alcohol on behavior.” Respondents were initially screened by telephone to confirm consumption of at least three alcoholic beverages per occasion at least twice per month as well as the absence of alcohol-related problems; non-drinkers were excluded. Eligible participants were then scheduled for an appointment at the laboratory. Upon arrival to the laboratory, 55 participants reported that they had not been in an intimate relationship during the past year, 32 men self-identified as non-heterosexual or did not report an exclusively heterosexual pattern of arousal or behavioral experiences on the Kinsey Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale (Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin 1948), and nine did not complete the questionnaire battery in its entirety. This resulted in a final sample 392 men who had been in a heterosexual relationship in the past year (see Table 1 for demographic characteristics). Men reported consuming an average of 4.67 (SD = 2.91) alcoholic drinks per drinking day approximately 2.27 (SD = 1.56) days per week. Eighty-three percent of participants reported the consumption of five or more drinks on at least one occasion during the past year. The sample’s demographic characteristics are consistent with samples utilized in extant literature upon which the present hypotheses are based. However, it is not assumed that the present hypotheses generalize across countries and cultures. All participants received $10 per hour for their participation. The university’s Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Table 1.

Sample Means (SD) and Percentages (Count) for Demographic Characteristics

| Age | 24.44 (2.69, range = 21–32) |

| Education Level | 14.62 (2.41) |

| Annual Income | $25,421 ($19,528) |

| Race | |

| White | 26.5% (104) |

| African American | 60% (236) |

| Multiracial | 9% (35) |

| Asian American | 3% (11) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | .5% (2) |

| Refused to Answer | 1% (4) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 5% (18) |

| Non-Hispanic or Non-Latino | 94% (369) |

| Refused to Answer | 1% (5) |

| Relationship Status | |

| Single, Never Married | 93% (366) |

| Married | 4% (17) |

| Divorced | 2% (6) |

| Separated | 1% (3) |

n = 392.

Measures

Demographic from

The self-report form obtained information such as age, years of education, self-identified sexual orientation, race, and relationship status.

Kinsey Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale (Kinsey et al. 1948)

A modified version of this scale was used to measure prior sexual arousal and experience on a scale ranging from exclusively heterosexual to exclusively homosexual. As previously noted, participants who did not report an exclusively heterosexual pattern of arousal and behavioral experiences were excluded from analyses.

Male Role Norms Scale (Thompson and Pleck 1986)

This 26-item Likert-type scale measures men’s endorsement of three fundamental dimensions of hegemonic masculine ideology: Status (e.g., “A man always deserves the respect of his wife and children”), Toughness (e.g., “In some kinds of situations a man should be ready to use his fists, even if his wife or his girlfriend would object”), and Antifemininity (e.g., “It bothers me when a man does something that I consider ‘feminine’”). Participants rate items on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Items from each subscale are summed, with higher scores reflecting a greater adherence to these norms of hegemonic masculinity. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses have supported this tri-dimensional factor structure (Sinn 1997; Thompson and Pleck 1986). These subscales have good reliability, with alpha coefficients ranging from .74 and .81 in standardization samples (Thompson and Pleck 1986), which was consistent with the present sample (Status: α = .80, Toughness: α = .73, Antifemininity: α = .77).

Masculine Gender Role Stress Scale (Eisler and Skidmore 1987)

This 40-item Likert-type scale measures the degree to which gender relevant situations are cognitively appraised as stressful or threatening. Participants rate items on a scale from 0 (not stressful) to 5 (extremely stressful). These 40 items are then summed, with higher scores indicating more trait masculine gender role stress. For example, items ask participants to rate how much stress they would feel in situations such as “letting a woman control the situation” or “having your lover say she is not satisfied.” This scale has been found to be independent of measures of masculinity and beliefs about the masculine gender role (Eisler and Skidmore 1987; Eisler et al. 1988). Standardization data indicate alpha reliability coefficients that exceed .90, which was consistent with the present sample (α = .93).

Heavy episodic drinking

Participants’ alcohol use during the past year was measured using the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s (NIAAA 2003) recommended set of six alcohol consumption questions. The question, “During the last 12 months, how often did you have five or more drinks containing any kind of alcohol in within a two-hour period?” was used to assess men’s report of past year heavy episodic drinking. A categorical range of responses from “1 to 2 days in the past year” to “every day” was provided (e.g., 2 to 3 days a month, one day a week, etc.). In accordance with the guidelines put forth by NIAAA, total heavy drinking days in the past year were generated. For example, if a participant endorsed heavy episodic drinking one day per week, their total heavy drinking days would be 52. As necessary, the average frequency of a response range (e.g., “2.5” for 2 to 3 times per month) was used to generate total heavy drinking days in the past year (e.g., 30). This strategy reliably assesses the number of days drinking at high levels over a specific period of time (for a review, see Sobell and Sobell 1995).

Conflict Tactics Scale – Revised (CTS-2; Straus, Hamby, Bony-McCoy, and Sugarman 1996)

The CTS-2 was used to measure men’s physical aggression perpetration toward a female intimate partner. The CTS-2 is 78-item self-report instrument that measures a range of events that occur during disagreements within intimate relationships. The current study used the 12-item Physical Assault subscale to assess the frequency of men’s physical assault perpetration during the past 12 months. Responses may range from 0 (never) to 6 (more than 20 times). The one-year frequency of physical assault is calculated by adding the midpoints of the score range for each item to form a total score. For example, if a participant indicates an item response of “3–5” times in the past year, his score would be a “4.” This method of scoring the CTS-2 permits examination of the frequency of different physically aggressive acts within the past year. An alpha reliability of .61 was obtained in the present sample, which is lower than reported in the CTS-2 authors’ standardization sample (α = .86).

Procedure

Upon arrival to the laboratory, participants were greeted by an experimenter, lead to a private experimental room, and provided informed consent. Participants then completed a questionnaire battery consisting of a demographic form, the NIAAA-recommended questions to assess alcohol use during the past year, and measures that assessed adherence to hegemonic masculine norms, masculine gender role stress, and the perpetration of intimate partner physical aggression within the past year, respectively. Participants completed these measures on a computer using MediaLab 2006 software (Jarvis 2006). The experimenter provided instructions on how to operate MediaLab, and was available to answer any questions during the session. Additional questionnaires were also completed, but are unrelated to the current study and thus not reported here. Prior to data collection, a fixed administration order of the questionnaires was randomly predetermined. All participants completed questionnaires in this fixed order. After completing the questionnaire battery, the experimenter debriefed participants and paid them for their time.

Results

Analytic Plan

Preliminary results revealed extreme non-normality of perpetration of intimate partner physical aggression (M = 6.45; SD = 11.07; skewness = 3.42; kurtosis = 16.40). As such, traditional OLS regression analyses, which assume normal distribution of residuals, were deemed inappropriate. Thus, negative binomial regression was employed, given that intimate partner physical aggression was highly skewed and overdispersed (Atkins and Gallop 2007, Hilbe 2011). Analyses were performed using Mplus v 7.3 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2010). As recommended by Hilbe (2011), maximum likelihood estimation was utilized. Results are reported as incidence rate ratios (IRR; i.e., exponentiated coefficients) and may be interpreted as the factor change in intimate partner physical aggression for each unit increase in the predictor variable.

Descriptives

Means, standard deviations, and ranges for pertinent study variables are presented in Table 2 along with their correlations. Means for participants’ self-reported adherence to the status, toughness, and antifemininity norms as well as masculine gender role stress were consistent with prior research with community-based samples (Parrott, Peterson, and Bakeman 2011). Participants reported heavy episodic drinking an average of 44 days during the past year (i.e., once every 8 days) and physical assault toward their female intimate partner an average of 6 times during the past year. The associations between heavy episodic drinking and the toughness and antifemininity norms of hegemonic masculinity and masculine gender role stress were small and not significant. The remaining correlations were all significant (p < .05). Seven of the 15 correlations were over .25, indicating mostly moderately sized associations (Cohen 1988). Variables were assessed for normality and collinearity. With the exception of a positive skew in participants’ self-reported frequency of intimate partner physical aggression perpetration, all variables were reasonably distributed (i.e., skew < 1.96 times its standard error). Tests for multicollinearity indicated acceptable levels for all predictor variables (all VIFs < 1.73).

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Intercorrelations for Key Variables

| Descriptives | Correlations | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| Variable | Scale Endpoints | M | SD | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. |

| 1. Status | 1–7 | 5.17 | 0.97 | — | .50** | .32** | .26** | .13* | .12* |

| 2. Toughness | 1–7 | 4.59 | 1.06 | — | — | .58** | .46** | .08 | .28** |

| 3. Antifemininity | 1–7 | 3.54 | 1.20 | — | — | — | .52** | .06 | .17** |

| 4. MGRS | 0–5 | 1.92 | 0.84 | — | — | — | — | −.01 | .22** |

| 5. HED | 0–365 | 44.62 | 2.90 | — | — | — | — | — | .13* |

| 6. IPPA | 0–240 | 6.45 | 11.07 | — | — | — | — | — | — |

Note. n = 392. Status = men’s belief that they must gain the respect from others; Toughness = men’s belief that they must appear aggressive and physically and emotionally strong; Antifemininity = men’s belief that they should avoid stereotypically feminine behaviors; MGRS = Masculine Gender Role Stress; HED = Heavy Episodic Drinking (i.e., number of days within past year consuming 5+ drinks within a two hour period); IPPA = Intimate partner physical aggression (i.e., number of physically aggressive behaviors reported in the past year); To aid in interpretability, per item means and standard deviations are reported for Status, Toughness, Antifemininity (0 = low adherence to norm, 7 high adherence to norm), and MGRS (0 = cognitively appraise gender relevant situations as not stressful, 5 = cognitively appraise gender relevant situations as extremely stressful);

p = < .01 and

p < .05.

Test of Mediation

Hypothesis 1 posited that masculine gender role stress would mediate the association between men’s adherence to hegemonic masculine norms (i.e., status, toughness, and antifemininity) and their perpetration of physical aggression toward female intimate partners. The proposed simple mediation models were tested using negative binomial regression models. In each model, (1) masculine gender role stress was regressed onto status, toughness, or antifemininity while controlling for the remaining two norms (i.e., the mediator variable model) and (2) intimate partner physical aggression was regressed onto status, toughness, or antifemininity and masculine gender role stress while controlling for the other two norms (i.e., the dependent variable model). Given the age range in the present study, these analyses were repeated with age entered in as a covariate and the pattern of effects described below did not change. Additionally, the indirect effects of each male role norm on intimate partner physical aggression via masculine gender role stress were estimated using the delta method specified by the IND command in Mplus. This analysis was employed three times to analyze separately the effects of men’s adherence to each norm of hegemonic masculinity on their perpetration of physical aggression toward their female intimate partners via masculine gender role stress.

Mediator variable models detected significant effects for adherence to the toughness (IRR = 1.24, p < .001) and antifemininity (IRR = 1.47, p < .001) norms but not the status norm (IRR = 1.03, p = .537). These results indicated that men’s beliefs that they must appear aggressive and physically and emotionally strong and that they should avoid stereotypically feminine behaviors were independently and positively associated with higher levels of masculine gender role stress.

Dependent variable models indicated that masculine gender role stress was significantly and positively associated with intimate partner physical aggression (IRR = 1.01, p = .031). In addition, these models detected a significant and positive direct effect of adherence to the toughness (IRR = 1.52, p < .001) and antifemininity norm (IRR = 1.24, p = .003) on intimate partner physical aggression. No such effects were detected for adherence to the status (IRR = 1.12, p = .514) norm.

Tests of indirect effects of adherence to each male norm on intimate partner physical aggression via masculine gender role stress indicated a significant indirect effect of antifemininity (IRR = 1.01, p = .038) and a marginal indirect effect of toughness (IRR = 1.01, p = .060). The indirect effect of status was not significant (IRR = 1.00, p = .552).

Test of Moderated Mediation

Hypothesis 2 posited that these indirect effects would be stronger among men who evidenced a pattern of heavy episodic drinking relative to men who did not evidence a pattern of heavy episodic drinking. To test this hypothesis, three separate negative binomial regressions were conducted using Preacher, Rucker, and Hayes’ (2007) Model 3 Mplus code for testing moderated mediation. Specifically, in each model (1) masculine gender role stress was regressed onto status, toughness, antifemininity while controlling for the other two norms (i.e., the mediator variable model), and (2) intimate partner physical aggression was regressed onto status, toughness, antifemininity while controlling for the other two norms, masculine gender role stress, heavy episodic drinking, and the Masculine Gender Role Stress X Heavy Episodic Drinking interaction term (i.e., the dependent variable model). Given the age range in the present study, these analyses were repeated with age entered in as a covariate and the pattern of effects described below did not change. Additionally, the conditional indirect effect of each male role norm on intimate partner physical aggression through masculine gender role stress at high (+1SD) and low (−1SD) levels of heavy episodic drinking was estimated using the delta method specified by the IND command in Mplus. The two male role norms not being examined were included as covariates in the mediator and dependent variable models. As such, results for all three models are equivalent, with the exception of the conditional indirect effects.

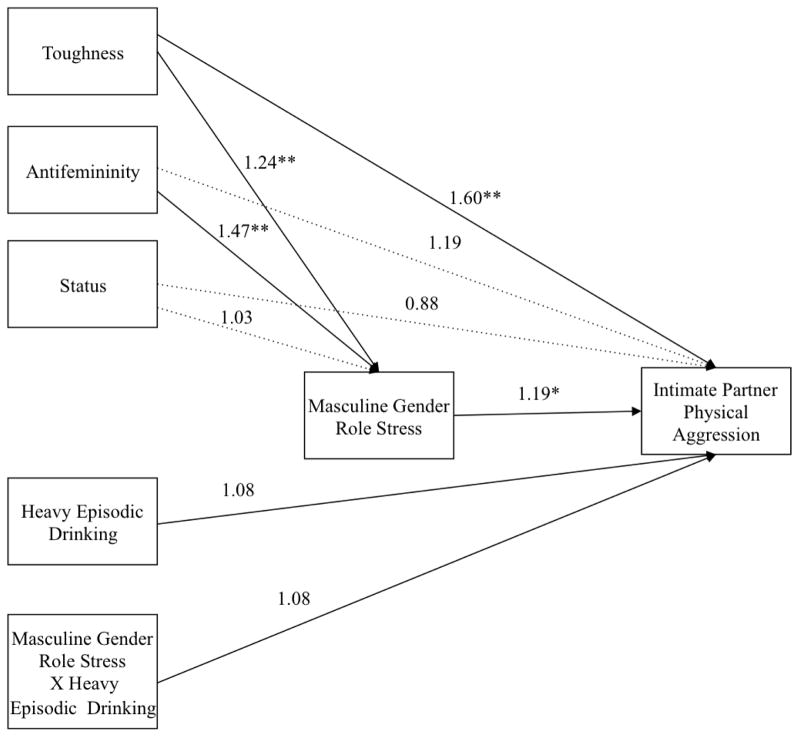

Figure 1 depicts results from the dependent variable model. Adherence to the toughness norm (IRR = 1.60; p < .001), but not status (IRR = 0.88; p =.217) or antifemininity (IRR = 1.19; p = .834) norms, was significantly and positively associated with intimate partner physical aggression. Additionally, the effect of masculine gender role stress (IRR = 1.19; p = .042) was significantly and positively associated with intimate partner physical aggression. The effects of heavy episodic drinking (IRR = 1.08; p = .144) and the Masculine Gender Role Stress X Heavy Episodic Drinking interaction (IRR = 1.08; p = .144) on intimate partner physical aggression were not significant. Results from mediator variable models indicated that adherence to the toughness (IRR = 1.24; p < .001) and antifemininity norms (IRR = 1.47; p < .001), but not status norm (IRR = 1.03; p = .496), were significantly and positively associated with masculine gender role stress.

Figure 1.

Final moderated mediation model predicting men’s perpetration in intimate partner physical aggression. Note: Estimates are incidence rate rates. *p < .05; **p < .001. Non-significant paths are dotted.

Results indicated that the indirect effect of toughness and antifemininity, but not status, on intimate partner physical aggression via masculine gender role stress was conditional upon men’s level of heavy episodic drinking (see Table 3). Specifically, in line with the hypothesized model, masculine gender role stress mediated the effect of (1) toughness on intimate partner physical aggression among men who endorsed high heavy episodic drinking (IRR = 1.05; p = .035) but not among men who endorsed low heavy episodic drinking (IRR = 1.02; p = .326). Similarly, masculine gender role stress mediated the effect of antifemininity on intimate partner physical aggression among men who endorsed high heavy episodic drinking (IRR = 1.10; p = .016) but not among men who endorsed low heavy episodic drinking (IRR = 1.04; p = .314).

Table 3.

Conditional Indirect Effect of Status, Toughness, and Antifemininity on Intimate Partner Physical Aggression via Masculine Gender Role Stress at High and Low Levels of Heavy Episodic Drinking (HED)

| Status

|

Toughness

|

Antifemininity

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | Z Statistic | IRR | B | SE | Z Statistic | IRR | B | SE | Z Statistic | IRR | |

| Low HED | .003 | .01 | .57 | 1.00 | .02 | .02 | .98 | 1.02 | .04 | .04 | 1.01 | 1.04 |

| High HED | .01 | .01 | .66 | 1.01 | .05 | .03 | 2.11* | 1.05 | .10 | .04 | 2.40* | 1.10 |

Note: IRR = Incidence rate ratio.

p < .05.

Discussion

The present study advances a theory-based pathway through which men’s heavy episodic drinking moderates associations between norms of hegemonic masculinity (i.e., status, toughness, and antifemininity), masculine gender role stress, and their perpetration of physical aggression toward female intimate partners. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, results indicate that adherence to the toughness and antifemininity norms, but not the status norm, is indirectly and positively associated with the perpetration of physical aggression toward female intimate partners via masculine gender role stress. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, results demonstrate that masculine gender role stress mediates these indirect effects only among men who engage in heavy episodic drinking.

Taken together, these findings add to the current alcohol-related aggression and masculinity-based literatures in two key ways. First, to our knowledge, the present study is the first to support a theory-based pathway wherein men’s appraisal of hypothetical threats to masculinity mediates the link between their adherence to hegemonic masculine norms and their perpetration of physical aggression toward female intimate partners. Relevant theory suggests that masculine gender role stress is an experiential consequence of rigid adherence to hegemonic masculine norms (Jacupcak et al. 2003); however, previous studies only examined masculine gender role stress as a moderator of the relation between gender norm adherence and aggressive behavior (Cohn and Zeichner 2006; Jacupcak et al. 2002).

Second, the present study is the first to show that men’s heavy episodic drinking moderates this process. This finding is consistent with existing research that identifies heavy episodic drinking as one of the most robust distal predictors of physical aggression toward intimate partners (Foran and O’Leary 2008). It is also consistent with research which shows that heavy drinking men who tend to appraise hypothetical threats to masculinity as stressful are particularly likely to experience anger activation (Copenhaver et al. 2000) and are more susceptible to drink heavily in response to situational triggers such as negative emotions and conflict (Lash, Copenhaver, and Eisler 1998).

Overall, support for the hypothesized moderated-mediation pathway suggests a parsimonious framework for understanding why the cognitive foundation of the gender role stress mechanism is vulnerable to the proximal effects of heavy drinking. In particular, the general aggression model suggests that the activation of gender-based schemas during couples’ conflict is associatively linked to affect- and arousal-based internal routes to intimate partner aggression. These biased schemas represent a self-regularly risk factor. In accordance with Alcohol Myopia Theory, heavy episodic drinkers likely disproportionately allocate their attention in accordance with these biased, gender-based schemas, which increases the likelihood of aggressive behavior. Indeed, the relation between masculine gender role stress and perpetration of physical aggression toward female intimate partners was not significant among non-heavy drinking men. However, among heavy drinking men, this association was positive and significant.

These findings suggest that for heavy drinking men, who are more likely to consume alcohol prior to intimate partner conflict situations relative to non-heavy drinking men, alcohol’s pharmacological impact on cognitive processing facilitates attention toward salient, provocative stimuli. In addition, these data suggest that toughness- and antifemininity-based aggression may function as one way through which men are able to “demonstrate” or reaffirm these aspects of their masculinity. Such a demonstration would reinforce men’s hegemonic construction of masculinity by maintaining an appearance as aggressive, physically strong, and antifeminine. Importantly, it is unclear why there was no such mediation effect of masculine gender role stress for the relation between the status norm of hegemonic masculinity and intimate partner physical aggression. Given the present study was the first to test this theory-based model, future research might replicate the present study’s findings and also examine other factors that might account for links between these norms and intimate partner physical aggression.

Limitations of the Present Study

Several limitations warrant attention in future research. First, men’s perpetration of physical aggression toward female intimate partners was measured via self-report. As a result, there is no way of knowing whether men (1) experienced threats to specific components of their hegemonic masculine identity and appraised those masculinity threats as stressful prior to their perpetration of physical aggression, or (2) were intoxicated during the time of the assault. Future research that seeks to temporally link men’s cognitive appraisal of masculinity threats with alcohol-facilitated intimate partner aggression would benefit from utilizing daily-diary (Testa and Derrick 2014) or laboratory-based methods (Eckhardt, Parrott, and Sprunger, in press) in order to more precisely assess the event-based link between these variables. Such methods allow for a more accurate examination of how, and under what circumstances, proximal alcohol-related effects influence these biased schemas among men who believe that they must meet specific gender-based standards. Related to this issue, it is important to emphasize that the Masculine Gender Role Stress Scale does not assess participants’ actual exposure to the potentially stressful gender-relevant situations to which men’s appraisals are assessed. Thus, future studies that examine this construct would be strengthened via the assessment of men’s actual exposure to these situations. Additionally, experimental studies could assess the independent and interactive effects of exposure to specific gender-relevant situations and alcohol intoxication on actual appraisal biases. For instance, as would be expected given the present findings, men who report high dispositional masculine gender role stress and are intoxicated should evidence the strongest biases in their appraisals of intimate conflict as threatening. In turn, the extent to which men’s tendency to evidence these biased appraisals should be positively related to intimate partner physical aggression.

Second, the internal consistency of the CTS-2 Physical Assault scale was low (α = .61). Because many studies that use the CTS-2 do not report this statistic, it is difficult to place accurately our low alpha in the context of related literature. However, Koss and colleagues (2007) also observed low internal consistency in another widely used behavioral rating scale in the aggression literature, the Revised Sexual Experiences Survey, and concluded that a low alpha does not weaken the validity of the measure. They argued that the computation of internal consistency is appropriate when assuming that a single underlying construct causes the acts of aggression assessed by the measure (i.e., a latent measurement model); however, it is not relevant when assuming that items do not correlate with one another (i.e., an induced measurement model). Indeed, a frequent use of the CTS-2 is to assess the frequency of behaviors that are likely to vary within each individual depending on a variety of factors and thus are not expected to be caused by a single latent construct. As such, the observed internal consistency for the CTS-2 Physical Assault scale likely does not weaken the validity of the scale or the present findings.

Third, assessment of study constructs was limited in scope. Future research would benefit from the examination of proximal and distal alcohol variables (e.g., acute alcohol intoxication, drinking pattern histories), myriad norms of hegemonic masculinity, and distinct forms of intimate partner aggression (e.g., physical, sexual, psychological) as measured by different methods (e.g., self-report, partner self-report). Importantly, efforts to bridge and inform bi-directionally laboratory- and survey-based research will advance the integration of the masculinity-based and alcohol-related aggression literatures. Fourth, the present sample is limited in its generalizability. Of particular note, the present sample was comprised largely of at-risk drinking men, which was defined as the consumption of five or more drinks on at least one occasion during the past year (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 2010). Because findings cannot be generalized to non-drinking or low risk drinking men, future research that utilizes sampling methods which overcome this limitation are needed to provide the ideal test of the proposed model. Finally, only men who self-identified as heterosexual were included. Thus, it is unclear the extent to which these findings apply to male-male intimate relationships. In particular, it is reasonable to suggest that constructs unique to non-heterosexual men such as internalized homophobia or felt stigma (Herek and McLemore 2013) contribute to a different cultural context which could change the interrelationships reported herein.

Conclusion

The present study reflects one of the few attempts to integrate alcohol-related and masculinity-based aggression literatures to inform the prediction of aggression toward intimate partners. Findings add to the current literature base by suggesting that men’s appraisal of hypothetical treats to masculinity mediates the association between their endorsement of the toughness and antifemininity norms and subsequent intimate partner physical aggression. And, of particular importance, results highlight alcohol’s role as a moderator of this gender role stress mechanism. While additional work must establish the temporal association between these variables, the present findings support interventions which challenge men’s gender-biased appraisals of conflict in intimate relationships and their beliefs regarding adherence to hegemonic masculinity more generally. Overall, these data represent a first step toward understanding how and when intimate partner aggression may function to reaffirm specific dimensions of hegemonic masculinity.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant R01-AA-015445 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism awarded to Dominic J. Parrott.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Research involving Human Participants and/or Animals: This study was approved by the corresponding author’s institutional IRB.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all research participants.

References

- Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. Human aggression. Annual Review Psychology. 2002;53:27–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins DC, Gallop RJ. Rethinking how family researchers model infrequent outcomes: A tutorial on count regression and zero-inflated models. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:726–735. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements K, Schumacher JA. Perceptual biases in social cognition as potential moderators of the relationship between alcohol and intimate partner violence: A review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2010;15:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2010.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn A, Zeichner A. Effects of masculine identity and gender role stress on aggression in men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2006;7:179–190. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.7.4.179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW. Masculinities. 2. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW, Messerschmidt JW. Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender and Society. 2005;19:829–859. doi: 10.1177/0891243205278639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver MM, Lash SJ, Eisler RM. Masculine gender-role stress, anger, and male intimate abusiveness: Implications for men’s relationships. Sex Roles. 2000;42:405–414. doi: 10.1023/A:1007050305387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- David DS, Brannon R. The male sex role: Our culture’s blueprint for manhood, what it’s done for us lately. In: David DS, Brannon R, editors. The forty-nine percent majority: The male sex role. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1976. pp. 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- DeWall C, Anderson CA, Bushman BJ. The general aggression model: Theoretical extensions to violence. Psychology of Violence. 2011;1:245–258. doi: 10.1037/a0023842. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI, Parrott DJ, Sprunger J. Mechanisms of alcohol-facilitated intimate partner violence. Violence Against Women. doi: 10.1177/1077801215589376. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckhardt CI, Samper R, Suhr L, Holtzworth-Munroe A. Implicit attitudes toward violence among male perpetrators of intimate partner violence: A preliminary investigation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27:471–491. doi: 10.1177/0886260511421677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM. The relationship between masculine gender role stress and men’s health risk: The validation of a construct. In: Levant RF, Pollack WS, editors. A new psychology of men. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1995. pp. 207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM, Skidmore JR. Masculine gender role stress: Scale development and component factors in the appraisal of stressful situations. Behavior Modification. 1987;11:123–136. doi: 10.1177/01454455870112001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM, Franchina JJ, Moore TM, Honeycutt HG, Rhatigan DL. Masculine gender role stress and intimate abuse: Effects of gender relevance of conflict situations on men’s attributions and affective responses. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2000;1:30–36. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.1.1.30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisler RM, Skidmore JR, Ward CH. Masculine gender-role stress: Predictor of anger, anxiety, and health-risk behaviors. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52:133–141. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foran HM, O’Leary K. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:1222–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchina JJ, Eisler RM, Moore TM. Masculine gender role stress and intimate abuse: Effects of masculine gender relevance of dating situations and female threat on men’s attributions and affective responses. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2001;2:34–41. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.2.1.34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR. Executive functioning and alcohol-related aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:541–555. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giancola PR, Zeichner A. The biphasic effects of alcohol on human physical aggression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:598. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.106.4.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Good GE, Borst TS, Wallace DL. Masculinity research: A review and critique. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 1994;3:3–14. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goudriaan AE, Grekin ER, Sher KJ. Decision making and binge drinking: A longitudinal study. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2007;31:928–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00378.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham K, Wells S, West P. Framework for applying explanations of alcohol-related aggression to naturally occurring aggressive behavior. Contemporary Drug Problems. 1997;24:625–666. [Google Scholar]

- Heise L. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4:262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek G, McLemore K. Sexual prejudice. Annual Review of Psychology. 2013;63:309–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman RE, O’Leary K, Jouriles EN. Alcohol and aggressive personality styles: Potentiators of serious physical aggression against wives? Journal of Family Psychology. 1995;9:44–57. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.9.1.44. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbe JM. Negative binomial regression. 2. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hines DA, Straus MA. Binge drinking and violence against dating partners: The mediating effect of antisocial traits and behaviors in a multinational perspective. Aggressive Behavior. 2007;33:441–457. doi: 10.1002/ab.20196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull J. A self-awareness model of the causes and effects of alcohol consumption. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1981;90:586–600. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.90.6.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito TA, Miller N, Pollock VE. Alcohol and aggression: A meta-analysis on the moderating effects of inhibitory cues, triggering events, and self-focused attention. Psychological Bulletin. 1996;120:60–82. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.120.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto DK, Corbin W, Lejuez C, MacPherson L. College men and alcohol use: Positive alcohol expectancies as a mediator between distinct masculine norms and alcohol use. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2014;15:29–39. doi: 10.1037/a0031594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Lisak D, Roemer L. The role of masculine ideology and masculine gender role stress in men’s perpetration of relationship violence. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2002;3:97–106. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.3.2.97. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Salters K, Gratz KL, Roemer L. Masculinity and emotionality: An investigation of men’s primary and secondary emotional responding. Sex Roles. 2003;49:111–120. doi: 10.1023/A:1024452728902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Tull MT, Roemer L. Masculinity, shame, and fear of emotions as predictors of men’s expressions of anger and hostility. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2005;6:275–284. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.6.4.275. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis BG. MediaLab (Version 2006.1.41) [Computer Software] New York, NY: Empirisoft Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE. Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, White J. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:357–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00385.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lash SJ, Copenhaver MM, Eisler RM. Masculine gender role stress and substance abuse among substance dependent males. Journal of Gender, Culture and Health. 1998;3:183–191. doi: 10.1023/A:1023293206690. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lash SJ, Eisler RM, Schulnian RS. Cardiovascular reactivity to stress in men effects of masculine gender role stress appraisal and masculine performance challenge. Behavior Modification. 1990;14:3–20. doi: 10.1177/01454455900141001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE. Alcohol and intimate partner violence: when can we say that heavy drinking is a contributing cause of violence? Addiction. 2005;100:422–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.00994.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard KE, Jacob T. Sequential interactions among episodic and steady alcoholics and their wives. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11:18–25. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.11.1.18. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Locke BD, Mahalik JR. Examining masculinity norms, problem drinking, and athletic involvement as predictors of sexual aggression in college men. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2005;52:279–283. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marczinski CA, Combs SW, Fillmore MT. Increased sensitivity to the disinhibiting effects of alcohol in binge drinkers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:346–354. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott RC, Schwartz JP, Trevathan-Minnis M. Predicting men’s anger management: Relationships with gender role journey and entitlement. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2012;13:49–64. doi: 10.1037/a0022689. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCreary DR, Newcomb MD, Sadava SW. The male role, alcohol use, and alcohol problems: A structural modeling examination in adult women and men. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1999;46:109–124. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.46.1.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt JW. Crime as structured action: Gender race, class, and crime in the making. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Stuart GL. Effects of masculine gender role stress on men’s cognitive, affective, physiological, and aggressive responses to intimate conflict situations. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2004;5:132–142. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.5.2.132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Stuart GL. A review of the literature on masculinity and partner violence. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2005;6:46–61. doi: 10.1037/1524-9220.6.1.46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. National Council on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism recommended sets of alcohol consumption questions. 2003 Retrieved from: http://www.niaaa.nih.gov/research/guidelines-and-resources/recommended-alcohol-questions.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Rethinking drinking: Alcohol and your health. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health U.S Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. Retrieved from: http://rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/default.asp. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary K, Smith Slep AM, O’Leary SG. Multivariate models of men’s and women’s partner aggression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:752–764. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil JM, Harway M. A multivariate model explaining men’s violence toward women. Violence Against Women. 1997;3:182–203. doi: 10.1177/1077801297003002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil JM, Helms BJ, Gable RK, David L, Wrightsman LS. Gender-Role Conflict Scale: College men’s fear of femininity. Sex Roles. 1986;14:335–350. doi: 10.1007/BF00287583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott DJ, Giancola PR. The effect of past-year heavy drinking on alcohol-related aggression. Journal on Studies of Alcohol. 2006;67:122–130. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrott DJ, Peterson JL, Bakeman R. Determinants of aggression toward sexual minorities in a community sample. Psychology of Violence. 2011;1:41–52. doi: 10.1037/a0021581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pernanen K. Alcohol and crimes of violence. In: Kissin B, Begleiter H, editors. The biology of alcoholism: Social aspects of alcoholism. New York: Plenum Press; 1976. pp. 351–444. [Google Scholar]

- Persampiere J, Poole G, Murphy CM. Neuropsychological correlates of anger, hostility, and relationship-relevant distortions in thinking among partner violent men. Journal of Family Violence. 2014;29:625–641. doi: 10.1007/s10896-014-9614-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pihl RO, Peterson JB, Lau MA. A biosocial model of the alcohol-aggression relationship. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1993;11:128–139. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1993.s11.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH. The gender role strain paradigm: An update. In: Levant RF, Pollack WS, editors. A new psychology of men. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1995. pp. 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana MC, Raj A, Decker MR, La Marche A, Silverman JG. Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83:575–585. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9061-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinn JS. The predictive and discriminant validity of masculinity ideology. Journal of Research in Personality. 1997;31:117–135. doi: 10.1006/jrpe.1997.2172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sippel LM, Marshall AD. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, intimate partner violence perpetration, and the mediating role of shame processing bias. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2011;25:903–910. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith RM, Parrott DJ, Swartout KM, Tharp A. Deconstructing hegemonic masculinity: The roles of antifemininity, subordination to women, and sexual dominance in men’s perpetration of sexual aggression. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2015;16:160–169. doi: 10.1037/a0035956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Alcohol consumption measures. In: Allen JP, Columbus M, editors. Assessing Alcohol Problems: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 1995. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: Its prized and dangerous effects. American Psychologist. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi: 10.1177/019251396017003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swartout KM, Thompson MP, Koss MP, Su N. What is the best way to analyze less frequent forms of violence? The case of sexual aggression. Psychology of Violence. doi: 10.1037/a0038316. In press. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SP, Leonard KE. Alcohol and human aggression. In: Geen RG, Donnerstein EI, editors. Aggression: Theoretical and Empirical Reviews. New York: Academic Press; 1983. pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Derrick JL. A daily process examination of the temporal association between alcohol use and verbal and physical aggression in community couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:127–138. doi: 10.1037/a0032988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KD, Levant RF. Does the endorsement of traditional masculinity ideology moderate the relationship between exposure to violent video games and aggression? Journal of Men’s Studies. 2012;20:47–56. doi: 10.3149/jms.2001.47. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson E, Pleck J. The structure of male role norms. American Behavioral Scientist. 1986;29:531–543. doi: 10.1177/000276486029005003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Towns AJ, Parker C, Chase P. Constructions of masculinity in alcohol advertising: Implications for the prevention of domestic violence. Addiction Research and Theory. 2012;20:389–401. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2011.648973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Truman DM, Tokar DM, Fischer AR. Dimensions of masculinity: Relations to date rape supportive attitudes and sexual aggression in dating situations. Journal of Counseling and Development. 1996;74:555–562. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6676.1996.tb02292.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uy PJ, Massoth NA, Gottdiener WH. Rethinking male drinking: Traditional masculine ideologies, gender-role conflict, and drinking motives. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2014;15:121–128. doi: 10.1037/a0032239. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Y, Steinfeldt JA, Speight QL, Hickman SJ. Content analysis of Psychology of Men and Masculinity (2000–2008) Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2010;11:170–181. doi: 10.1037/a0019133. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO expert committee on problems related to alcohol consumption (2nd Report) 2007 Retrieved from http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/expert_committee_alcohol_trs944.pdf?ua=1. [PubMed]

- Zurbriggen EL. Social motives and cognitive power–sex associations: Predictors of aggressive sexual behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;78:559–581. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.3.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]