Progress in elucidating the complex pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has led to a much deeper understanding of the mechanisms involved in maintaining intestinal homeostasis in response to a broad range of environmental factors.1,2 These efforts have helped to reveal the genetic underpinnings of the environmentally responsive pathways involved and the manner in which they maintain or perturb the complex relationships that exist between the most outermost boundaries of the host that reside at the epithelial interface and that exists between the commensal microbiota in the lumen and the abluminal components of the host immune systems.1,3–5 These studies have revealed a number of interrelated, genetically defined, pathways critical for intestinal homeostasis, that if defective increase the risk for perturbed inflammatory responses and development of chronic inflammation as seen in IBD in the setting of relevant environmental stressors that intersect with and overwhelm normal homeostatic control mechanisms.6,7

One such pathway that has been shown recently to impose genetic risk for development of both forms of IBD (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) is associated with proper regulation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) as revealed by genetic polymorphisms in XBP1 (which is activated by inositol requiring enzyme 1 or IRE1 and functions as a transcription factor),8 ORMDL3 (orsomucoid related molecule domain containing protein like-3, which regulates the uptake of cytosolic Ca++ into the endoplasmic reticulum [ER]),9 and AGR2 (anterior gradient gene related protein 2; an ER chaperone involved in protein folding).10 The UPR is a core pathway that allows the cell to manage the folding of proteins in the ER and ultimately their secretion.11 The ER is an organelle that plays a critical role in protein folding and it is estimated that the ER supports the biosynthesis of approximately one third of all cellular proteins in a typical eukaryotic cell.11 As a consequence, cells that are highly secretory such as intestinal epithelial cells (IEC; especially Paneth and goblet cells), pancreatic acinar cells, pancreatic endocrine cells, hepatocytes, and salivary gland epithelial cells, as well as hematopoietic cells (including macrophages, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, plasma cells, and CD8+ T cells) are highly dependent upon the UPR for both elicitation of their relevant biologic functions and ability to survive the stresses that arise in association with carrying out these duties.8,12–16

The UPR is activated by the accumulation of misfolded proteins within the ER, which are sensed by 1 of several ER-associated transmembrane proteins and affiliated ER-resident chaperones such as glucose-regulated protein 78 (grp78).11 The accumulation of misfolded proteins within the ER is expected to occur as a consequence of primary factors (genetic mutations that directly affect the structure of a protein, the ER environment as revealed by the calcium content, oxidative state and protein quality control machinery, or the signaling molecules that regulate the UPR) and secondary factors (tissue injury and the associated hypoxia, inflammation, and nutrient access).17,18 Once activated, these ER sensors are capable of activating or inducing the expression of transcription factors that control the expression of adaptive factors that enhance the ability of the cell to withstand ER stress through up-regulation of proteins involved in the generation of additional ER membranes through induction of lipid biosynthesis, protein folding and degradation, halting additional protein translation, and, when unresolved, cellular “suicide” through the induction of programmed cell death.11 It is also notable that the UPR is connected closely to autophagy,19,20 another fundamental cellular pathway that is genetically linked to Crohn’s disease as revealed by polymorphisms in ATG16L1 (autophagy related gene 16 like-1 protein),21,22 IRGM (immunity-related GTPase family M protein),23,24 and LRRK2 (leucinerich repeat kinase 2),25 which when induced functions in the removal of incapacitated organelles or proteins. As such, autophagy is able to assist the UPR and in doing so participates in the alleviation of ER stress.

Studies in mice with selective deletion of Xbp1 in IEC have recently shown that the UPR is especially important to the function and survival of Paneth cells.8 Loss of XBP1 expression selectively within the IEC leads sequentially to decreased Paneth cell function and hypersensitivity to cytokine and microbial stimulation and, finally, Paneth cell death by apoptosis in association with spontaneous enteritis.8 The Paneth cell resides at the base of intestinal crypts of the small intestine and is estimated to be the most long-lived (~30 days) and highly secretory IEC type with an extremely developed ER that is involved in delivering antimicrobial peptides (eg, the α-defensins, human defensin-5 and -6) into the lumen and regulating crypt stem cell function.26–28 The Paneth cell is increasingly recognized to be of critical importance to both intestinal homeostasis and the pathogenesis of IBD because Paneth cell loss is associated with dysbiosis and increased adherence of the commensal microbiota to the epithelium29 and a number of pathways such as the UPR (XBP1),8 autophagy (ATG16L1),30,31 IEC differentiation (TCF4),32 and intracellular pattern recognition and microbial sensing (NOD2)33 are associated with genetic risk for IBD and likely do so, at least in part, through their effects on Paneth cells.

It is therefore of interest that Grootjans et al34 in this issue of GASTROENTEROLOGY elegantly show that ischemia– reperfusion (I/R) injury of the human jejunum exhibits its earliest and most significant effect on the epithelium and in particular the Paneth cell. It is well known that the epithelium is the intestinal cell type most susceptible to ischemia, but these studies now show that among the four lineages of IECs that arise from the common stem cell (goblet cell, enteroendocrine cell, absorptive IEC, and Paneth cell), it is the distinctly secretory Paneth cell which is most susceptible to I/R injury. In this study, Grootjans et al studied 30 patients who were undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy for other indications. In a very innovative clinical procedure, they induced ischemia on a 6-cm segment of jejunum for either 30, 45, or 60 minutes followed by either 0, 30, or 120 minutes of reperfusion. Interestingly, through their experimental framework, they were able to show that increasing durations of ischemia, more so than the length of time associated with reperfusion, was associated with increased activation of the UPR as revealed by increased spliced XBP1 (the transcriptionally active form of XBP1 as a consequence of IRE1 endoribonuclease activity on unspliced XBP1) and grp78 (the ER chaperone that senses the presence of unfolded proteins and is a transcriptional target of the UPR).34 In addition, the authors showed that prolonged ischemia beyond 30 minutes leads to profound activation of the UPR and apoptosis (as shown by increased CHOP, which is a transcriptional target of the UPR that promotes apoptosis and activated caspase-3 and TUNEL staining as evidence of active apoptosis) and shedding of Paneth cells into the intestinal lumen.34

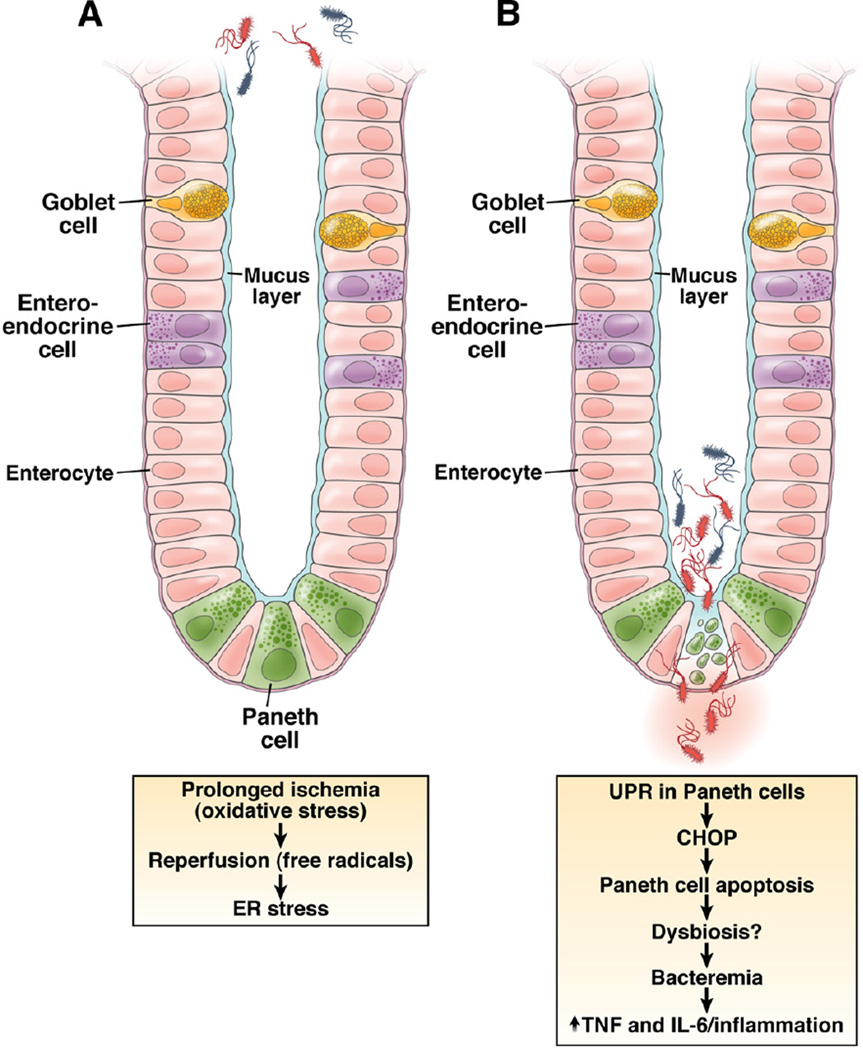

The degree of Paneth cell apoptosis was directly and strongly correlated with the ratio of spliced XPB1 (XBP1s):unspliced XBP1 (XBP1u), supporting a direct relationship between ER stress and Paneth cell death. This was confirmed in a similar experimental arrangement in rats, which showed that I/R was associated with ER stress in Paneth cells and their death by programmed cell death.34 Although not shown in the human clinical protocol, another experimental grouping in rats showed that Paneth cell loss was specifically associated with increased bacterial translocation into mesenteric lymph nodes, spleen, and liver.34 Specifically, disruption of villous epithelial cells without affecting Paneth cells, as induced by hemorrhagic shock, was associated with bacteremia. However, bacteremia was substantially increased upon additional functional depletion of Paneth cells as achieved by the zinc chelator dithizone (Figure 1).34 These studies are consistent with emerging evidence that Paneth cell antimicrobial function is important in preventing bacterial adherence to27 and translocation across33 the epithelium, including that associated with abnormal XBP1 function.8

Figure 1.

Effect of I/R injury on intestinal epithelium.

The studies by Grootjans et al highlight the increasing evidence for an important link between I/R injury, classic activators of the UPR such as depletion of oxygen and nutrient supply, as well as I/R injury of many types of tissues. Studies of I/R injury of cardiomyocytes, for example, have shown a critical role for XBP1 and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), an ER-resident protein like IRE1 involved in inducing the UPR, in protecting from the ER stress, which is induced.35 Thus, it can be imagined that the genetic composition of the host is an important component in the susceptibility to I/R induced injury and consequently bacteremia through effects on Paneth cell function. Given the common occurrence of hypoxia in general36 and I/R as a component of numerous clinical conditions, the observations contained herein are of broad importance and relevance.

These studies also call attention to the potential role of ischemia in the pathogenesis of IBD. It has been postulated that low levels of ischemia at the microvasculature level may play an important adjuvant role in the development of IBD36 and, as shown here, potentially through affecting Paneth cell function. Indeed, the study by Grootjans et al fits wells into the mounting evidence in support of the importance of Paneth cells in the maintenance of intestinal homeostasis and the pathogenesis of IBD.34 These studies demonstrate directly in a human model, as revealed by I/R injury, the special role that the UPR plays in Paneth cell survival with its broad implications for a wide range of clinical problems. Future studies thus need to be directed at understanding the intracellular pathways that link the UPR to Paneth cell function and loss to protect and preserve this cell type, which is now linked with an increasingly diverse group of clinical conditions.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors’ laboratories are supported by NIH RO1 grants DK44319, DK51362, DK53056, and DK08819 (R.S.B.), T32 DK07533-21A1 (R.S.B.), and P30 DK034854 (Harvard Digestive Diseases Center), European Research Council under the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ ERC Grant agreement n° 260961 (A.K.), the Austrian Science Fund and Ministry of Science P21530 (A.K.) and START Y446 (A.K.), Innsbruck Medical University (MFI 2007-407, A.K.), and the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre (A.K.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Contributor Information

Arthur Kaser, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom and, Department of Medicine II, Innsbruck Medical University, Innsbruck, Austria.

Michal Tomczak, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Richard S. Blumberg, Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts

References

- 1.Kaser A, Zeissig S, Blumberg RS. Inflammatory bowel disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:573–621. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham C, Cho JH. Inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2066–2078. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Round JL, Mazmanian SK. The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:313–323. doi: 10.1038/nri2515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Limbergen J, Wilson DC, Satsangi J. The genetics of Crohn’s disease. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2009;10:89–116. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082908-150013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garrett WS, Gordon JI, Glimcher LH. Homeostasis and inflammation in the intestine. Cell. 2010;140:859–870. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anderson CA, Massey DC, Barrett JC, et al. Investigation of Crohn’s disease risk loci in ulcerative colitis further defines their molecular relationship. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:523e3–529e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaser A, Blumberg RS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the intestinal epithelium and inflammatory bowel disease. Semin Immunol. 2009;21:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaser A, Lee AH, Franke A, et al. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008;134:743–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGovern DP, Gardet A, Torkvist L, et al. Genome-wide association identifies multiple ulcerative colitis susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:332–337. doi: 10.1038/ng.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao F, Edwards R, Dizon D, et al. Disruption of Paneth and goblet cell homeostasis and increased endoplasmic reticulum stress in Agr2-/- mice. Dev Biol. 2010;338:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ron D, Walter P. Signal integration in the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee AH, Chu GC, Iwakoshi NN, et al. XBP-1 is required for biogenesis of cellular secretory machinery of exocrine glands. EMBO J. 2005;24:4368–4380. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwakoshi NN, Pypaert M, Glimcher LH. The transcription factor XBP-1 is essential for the development and survival of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2267–2275. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brunsing R, Omori SA, Weber F, et al. B- and T-cell development both involve activity of the unfolded protein response pathway. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17954–17961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee AH, Scapa EF, Cohen DE, et al. Regulation of hepatic lipogenesis by the transcription factor XBP1. Science. 2008;320:1492–1496. doi: 10.1126/science.1158042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinon F, Chen X, Lee AH, et al. TLR activation of the transcription factor XBP1 regulates innate immune responses in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:411–418. doi: 10.1038/ni.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaser A, Blumberg RS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and intestinal inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2010;3:11–16. doi: 10.1038/mi.2009.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Todd DJ, Lee AH, Glimcher LH. The endoplasmic reticulum stress response in immunity and autoimmunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:663–674. doi: 10.1038/nri2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaser A, Martinez-Naves E, Blumberg RS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: implications for inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:318–326. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32833a9ff1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hampe J, Franke A, Rosenstiel P, et al. A genome-wide association scan of nonsynonymous SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for Crohn disease in ATG16L1. Nat Genet. 2007;39:207–211. doi: 10.1038/ng1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rioux JD, Xavier RJ, Taylor KD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:596–604. doi: 10.1038/ng2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3,000 shared controls. Nature. 2007;447:661–678. doi: 10.1038/nature05911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parkes M, Barrett JC, Prescott NJ, et al. Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn’s disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2007;39:830–832. doi: 10.1038/ng2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barrett JC, Hansoul S, Nicolae DL, et al. Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:955–962. doi: 10.1038/NG.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snippert HJ, van der Flier LG, Sato T, et al. Intestinal crypt homeostasis results from neutral competition between symmetrically dividing Lgr5 stem cells. Cell. 2010;143:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaishnava S, Behrendt CL, Ismail AS, et al. Paneth cells directly sense gut commensals and maintain homeostasis at the intestinal host-microbial interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20858–20863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808723105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ayabe T, Satchell DP, Wilson CL, et al. Secretion of microbicidal alpha-defensins by intestinal Paneth cells in response to bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:113–118. doi: 10.1038/77783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salzman NH, Hung K, Haribhai D, et al. Enteric defensins are essential regulators of intestinal microbial ecology. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:76–83. doi: 10.1038/ni.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cadwell K, Liu JY, Brown SL, et al. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature. 2008;456:259–263. doi: 10.1038/nature07416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cadwell K, Patel KK, Maloney NS, et al. Virus-plus-susceptibility gene interaction determines Crohn’s disease gene Atg16L1 phenotypes in intestine. Cell. 2010;141:1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wehkamp J, Wang G, Kubler I, et al. The Paneth cell alpha-defensin deficiency of ileal Crohn’s disease is linked to Wnt/Tcf-4. J Immunol. 2007;179:3109–3118. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.5.3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kobayashi KS, Chamaillard M, Ogura Y, et al. Nod2-dependent regulation of innate and adaptive immunity in the intestinal tract. Science. 2005;307:731–734. doi: 10.1126/science.1104911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grootjans J, Hodin CM, de Haan J–J, et al. Level of activation of the unfolded protein response correlates with Paneth cell apoptosis in human small intestine exposed to ischemia/reperfusion. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:529–539. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doroudgar S, Thuerauf DJ, Marcinko MC, et al. Ischemia activates the ATF6 branch of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29735–29745. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.018036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colgan SP, Taylor CT. Hypoxia: an alarm signal during intestinal inflammation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;7:281–287. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]