Abstract

We identified a functional single strand origin of replication (sso) in the integrative and conjugative element ICEBs1 of Bacillus subtilis. Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs, also known as conjugative transposons) are DNA elements typically found integrated into a bacterial chromosome where they are transmitted to daughter cells by chromosomal replication and cell division. Under certain conditions, ICEs become activated and excise from the host chromosome and can transfer to neighboring cells via the element-encoded conjugation machinery. Activated ICEBs1 undergoes autonomous rolling circle replication that is needed for the maintenance of the excised element in growing and dividing cells. Rolling circle replication, used by many plasmids and phages, generates single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). In many cases, the presence of an sso enhances the conversion of the ssDNA to double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) by enabling priming of synthesis of the second DNA strand. We initially identified sso1 in ICEBs1 based on sequence similarity to the sso of an RCR plasmid. Several functional assays confirmed Sso activity. Genetic analyses indicated that ICEBs1 uses sso1 and at least one other region for second strand DNA synthesis. We found that Sso activity was important for two key aspects of the ICEBs1 lifecycle: 1) maintenance of the plasmid form of ICEBs1 in cells after excision from the chromosome, and 2) stable acquisition of ICEBs1 following transfer to a new host. We identified sequences similar to known plasmid sso's in several other ICEs. Together, our results indicate that many other ICEs contain at least one single strand origin of replication, that these ICEs likely undergo autonomous replication, and that replication contributes to the stability and spread of these elements.

Author Summary

Mobile genetic elements facilitate movement of genes, including those conferring antibiotic resistance and other traits, between bacteria. Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs) are a large family of mobile genetic elements that are typically found integrated in the chromosome of their host bacterium. Under certain conditions (e.g., DNA damage, high cell density, stationary phase) an ICE excises from the host chromosome to form a circle. A linear single strand of ICE DNA can be transferred to an appropriate recipient through the ICE-encoded conjugation machinery. In addition, following excision from the chromosome, at least some (perhaps most) ICEs undergo autonomous rolling circle replication, a mechanism used by many plasmids and phages. Rolling circle replication generates single-stranded DNA (ssDNA). We found that ICEBs1, from Bacillus subtilis, contains at least two regions that enable conversion of ssDNA to double-stranded DNA. At least one of these regions functions as an sso (single strand origin of replication). ICEBs1 Sso activity was important for the ability of transferred ICEBs1 to be acquired by recipients and for the ability of ICEBs1 to replicate autonomously after excising from its host’s chromosome. We identified putative sso's in several other ICEs, indicating that Sso activity is likely important for the replication, stability and spread of these elements.

Introduction

Horizontal gene transfer, the ability of cells to acquire DNA from exogenous sources, is a driving force in bacterial evolution, facilitating the movement of genes conferring antibiotic resistance, pathogenicity, and other traits [1]. Conjugation, a form of horizontal gene transfer, is the contact-dependent transfer of DNA from a donor to a recipient, generating a transconjugant. During conjugation, the DNA to be transferred is processed and protein machinery in the donor mediates transfer to the recipient. The proteins involved in DNA processing and conjugation are encoded by a conjugative element.

Integrative and conjugative elements (ICEs, also called conjugative transposons), appear to be more prevalent than conjugative plasmids [2]. The conjugation machinery (a type IV secretion system) encoded by ICEs is homologous to that of conjugative plasmids, and much of what is known about the mechanisms of transfer have come from studies of conjugative plasmids [3,4]. The defining feature of ICEs that distinguish them from conjugative plasmids is that ICEs are typically found integrated into a host chromosome and are passively propagated during chromosomal replication and cell division.

ICEBs1 from Bacillus subtilis (Fig 1) is an integrative and conjugative element that is easily manipulated and can be activated in the vast majority of cells in a population [5–10]. Like most other ICEs, ICEBs1 resides integrated in the host chromosome and most of its genes are repressed [5,11,12]. ICEBs1 gene expression is induced in response to DNA damage during the RecA-dependent SOS response and following production of the cell- sensory protein RapI [5,6,13]. DNA damage and RapI independently cause proteolytic cleavage of the ICEBs1 repressor ImmR [13], leading to de-repression of ICEBs1 gene expression and production of proteins needed for excision and transfer. Excision from the chromosome results in the formation of a circular plasmid form of ICEBs1. If appropriate recipients are present, the ICEBs1-encoded conjugation machinery can mediate transfer, presumably of linear single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) from host (donor) to recipient, generating a transconjugant. ICEBs1 then integrates into the chromosome of the transconjugant. ICEBs1 can be induced in >90% of cells in a population simply by overexpression of the regulator rapI [5,6].

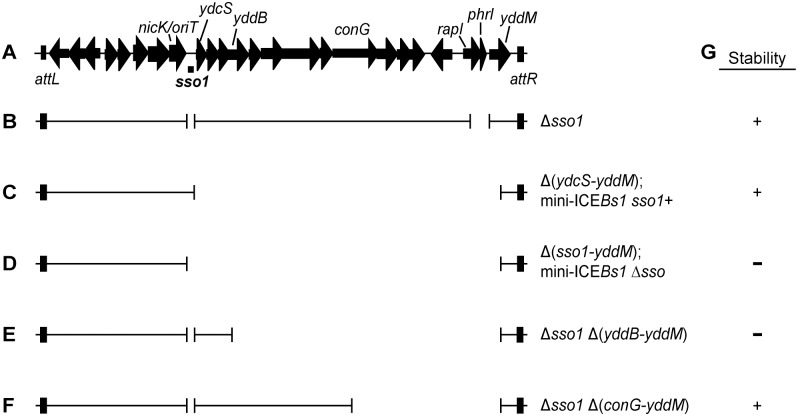

Fig 1. Map of ICEBs1 and mutants.

(A) Map of ICEBs1. A map of the genes and some of the sites in the ~20 kb ICEBs1 is shown, not precisely to scale. The location of sso1, between nicK and ydcS, is indicated underneath the map of ICEBs1. This is the ~200 bp sequence that is similar to the sso of pTA1060 (Fig 2). The 418 bp fragment that was cloned to test for sso activity extends ~100 bp upstream and downstream of the region shown. Arrows indicate open reading frames and the direction of transcription. The black rectangles at the ends of ICEBs1 represent the flanking 60 bp repeats attL and attR that contain the site-specific recombination sites required for excision of the element from the chromosome. (B-F) Schematics of ICEBs1 mutants used to test sso function. Thin lines indicate the regions of ICEBs1 present and gaps correspond to deleted regions. Except for the markerless Δsso1 allele, all deletions also contain an insertion of a kan cassette (not included in the figure). Strains containing these ICEBs1 mutants are listed in Table 1. (B) The Δsso1 markerless deletion is denoted by the gap surrounding sso1. The larger gap near the right end indicates deletion of rapI-phrI and insertion of kan (not included in the figure). (C-D) Schematics of mini-ICEBs1 mutants that are missing all genes and most sequences downstream of sso1. (C) contains sso1; (D) missing sso1. (E-F) Schematics of Δsso1 ICEBs1 mutants that are also missing sequences between yddB and yddM (E) or conG and yddM (F). Deletion endpoints are described in Materials and Methods. (G) Summary of the results from experiments measuring stability of the ICEBs1 mutants after induction in dividing host cells and in transconjugants. + indicates stable; − indicates decreased stability.

The proteins that transfer ICEs are homologous to those that transfer conjugative plasmids, including the F plasmid from Escherichia coli [14] and pCF10 from Enterococcus faecalis [4]. Prior to transfer, a relaxase nicks one DNA strand at the origin of transfer (oriT) and becomes covalently attached to the 5' end. Based on analogy to the F and Ti plasmids, the DNA is unwound after nicking and the nicked ssDNA with the attached relaxase is transferred to the recipient [15–18]. Once in a recipient (now a transconjugant), the relaxase attached to the transferred linear ssDNA is believed to catalyze the circularization (ligation) of ssDNA with the concomitant release of the relaxase [19–21]. Conversion of this circular ssDNA to dsDNA in the transconjugant should be needed for efficient integration into the chromosome of the new host because the substrate for the ICE recombinase (integrase) is typically dsDNA [22]. Also, following the same rationale, it is likely that integration of the ICE back into the host chromosome from which it originally excised requires that the ICE be double-stranded.

The nicking and unwinding of conjugative DNA for transfer is similar to the early events in rolling circle replication (RCR) used by many plasmids and phages [reviewed in 23]. RCR plasmids encode a relaxase that binds a plasmid region called the double strand origin (dso) and nicks a single DNA strand (the leading strand). Following association of a helicase and the replication machinery, leading strand DNA replication proceeds from the free 3’ end using the circular (un-nicked) strand as template. Once the complement of the circular strand is synthesized, the relaxase catalyzes the release of two circular DNA species: one dsDNA circle, and one ssDNA circle.

The circular ssDNA is converted to dsDNA, typically using an RNA primer to a region of the circular ssDNA. Priming of the ssDNA circle allows DNA polymerase to synthesize the complementary strand, followed by joining of the free DNA ends by host DNA ligase [23]. Three general mechanisms for initiation of RNA primer synthesis for RCR and conjugative plasmid complementary strand synthesis have been described: 1) recruitment of host RNA polymerase; 2) recruitment of host primase; and 3) use of a plasmid-encoded primase [3,24,25]. Recruitment of the host RNA polymerase or primase typically requires a region of the plasmid that is revealed and active only when single-stranded (that is, after nicking and unwinding by helicase). This region is referred to as a single strand origin of replication (sso) and has been defined for many plasmids and phages that replicate by the rolling circle mechanism [24]. Sso activity also contributes to plasmid stability [26–29]. Here, we use "sso" to indicate a DNA sequence that is orientation-specific and promotes second strand synthesis of elements that use rolling circle replication.

Virtually nothing is known about how the transferred ssDNA of ICEBs1, or any other ICE, is converted to dsDNA. During conjugation, the form of ICEBs1 DNA that is transferred to recipients is likely ssDNA with an attached relaxase [7,8], analogous to conjugative transfer of other elements [15–17]. Furthermore, when activated in host cells, ICEBs1 replicates autonomously by the rolling circle mechanism and this replication is required for stability of the excised element in a population of growing cells [30]. It is not known how dsDNA is synthesized from the ssDNA that is generated during rolling circle replication of ICEBs1 in host cells.

We postulated that ICEBs1 has an efficient mechanism for converting ssDNA to dsDNA, both during rolling circle replication of ICEBs1 in host cells and following conjugative transfer of ssDNA to recipients (that is, in transconjugants). Since the ICEBs1 relaxase does not appear to have a primase domain, we postulated that ICEBs1 might have a functional sso. We identified a single strand origin of replication in ICEBs1, which we named sso1. sso1 is similar to the sso's of several characterized plasmids. We found that sso1 was sufficient to correct replication defects in a plasmid that uses rolling circle replication and that otherwise did not have an sso, indicating that sso1 was functional. Analyses of an sso1 mutant of ICEBs1 indicated that there is at least one other region in ICEBs1 that is able to promote second strand synthesis. Our results indicate that Sso function in ICEBs1 was important for the stable acquisition of ICEBs1 by transconjugants and for maintenance of ICEBs1 following excision in host cells. These findings highlight the importance of autonomous replication in the ICE lifecycle and likely extend to many, and perhaps most, functional ICEs.

Results

Identification of a putative single strand origin of replication in ICEBs1

We searched [31] ICEBs1 for sequences that are similar to known sso's from plasmids that replicate in B. subtilis by rolling circle replication. We found that an intergenic region in ICEBs1 immediately downstream of nicK (the gene for relaxase) is 76% identical to the sso of B. subtilis RCR plasmid pTA1060 [32,33] (Figs 1A and 2). This sequence in ICEBs1 is also similar to the sso's of related RCR plasmids pBAA1, pTA1015, and pTA1040 [33] (Fig 2). Experiments described below demonstrate that this region of ICEBs1 functions as an sso. Therefore, we named it sso1.

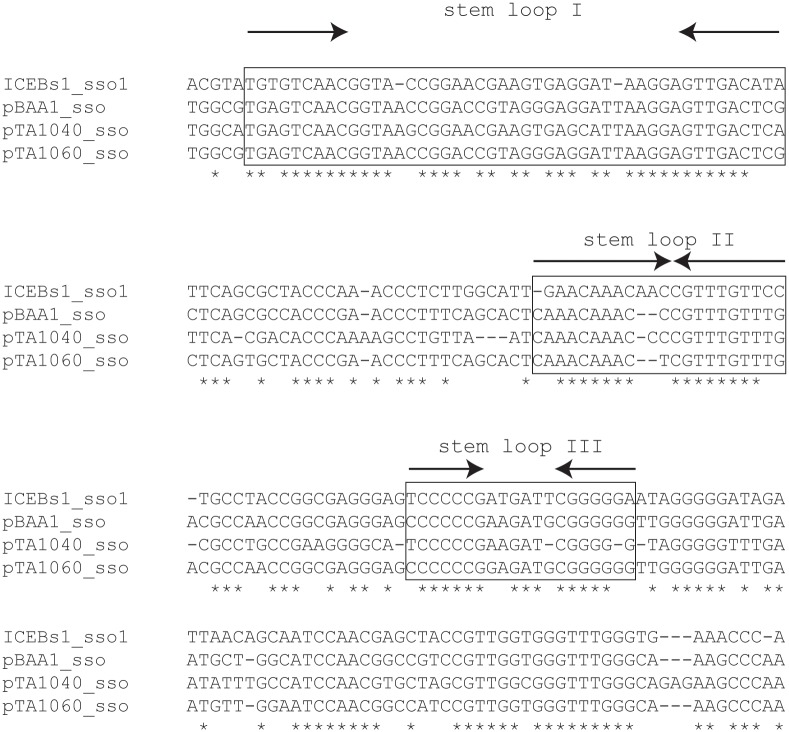

Fig 2. A region of ICEBs1 (sso1) is similar to sso's from RCR plasmids.

ICEBs1 sso1 is similar to the sso's of B. subtilis RCR plasmids pBAA1, pTA1040 (NCBI accession NC_001764.1, position 5109–5307) and pTA1060 (accession NC_001766, position 6349–6549) [32,33]. sso sequences were compared with the multiple sequence alignment algorithm T-COFFEE [34]. Asterisks indicate nucleotides that are identical in all four sso's. Horizontal dashes correspond to gaps. The boxed regions are predicted to form stem loop structures when single-stranded and are important for pBAA1 sso activity [35]. Single-stranded ICEBs1 sso1 is also predicted to form the three stem loops important for pBAA1 sso activity as determined by the ssDNA folding prediction program Mfold [36]. The arrows indicate predicted stems (inverted repeats) of stem-loop structures.

ICEBs1 sso1 contained conserved features known to be important for pBAA1 sso activity. Functional studies of the pBAA1 sso defined three stem-loop structures that were important for activity [35]. Single-stranded ICEBs1 sso1 was predicted to form three stem-loop structures that were similar to those of pBAA1 on the levels of sequence and secondary structure (Fig 2). Based on these analyses, we predicted that sso1 was functional.

Single strand origins are known to increase the stability of RCR plasmids. They also cause a reduction in the amount of ssDNA that accumulates from RCR plasmids. We tested the ability of sso1 from ICEBs1 to function as an sso using four different assays, one assay for stability of an RCR plasmid and three types of assays for ssDNA.

sso1 from ICEBs1 increases the stability of the RCR plasmid pHP13

pHP13 is an sso-deficient RCR plasmid that replicates in B. subtilis [37]. pHP13 and other sso-deficient RCR plasmids are relatively unstable and lost from the population without selection for the antibiotic to which the plasmid confers resistance. However, the plasmids are stabilized if they contain a functional sso [e.g., in 26,38].

We found that sso1 increased the stability of pHP13. We cloned a 418 bp region containing the putative ICEBs1 sso1 into pHP13, generating pHP13sso1 (pCJ44), and compared stability of plasmids with and without the putative ICEBs1 sso1. A single colony of B. subtilis cells containing either pHP13 or pHP13sso1 (strains CMJ77 and CMJ78, respectively; Table 1) was inoculated into rich (LB) liquid medium containing 2.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol to select for each plasmid. Exponentially growing cultures were diluted ~1/50 in antibiotic-free LB medium. Cultures were diluted as needed in non-selective medium to maintain exponential growth. After approximately 20 generations of growth, cells were plated on antibiotic-free LB agar. Individual colonies were picked and tested for growth on selective (antibiotic-containing) and non-selective agar plates to calculate the percentage of antibiotic-resistant (plasmid-containing) clones. Approximately 11% (43/400) of the colonies tested had lost pHP13. In contrast, only 0.5% (2/400) of the colonies tested had lost pHP13sso1.

Table 1. Bacillus subtilis strains used.

| Strain | Relevant genotype 1 (reference) |

|---|---|

| IRN342 | Δ(rapI-phrI)342::kan [5] |

| CAL85 | ICEBs1 0 str-84 [5] |

| CAL874 | Δ(rapI-phrI)342::kan, amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) spc}[30] |

| CMJ77 | ICEBs1 0, pHP13 (cat mls) |

| CMJ78 | ICEBs1 0, pCJ44 (pHP13sso1 cat mls) |

| CMJ102 | ICEBs1 0, pCJ45 (pHP13sso1R cat mls) |

| CMJ118 | ICEBs1 0, lacA::{(PrpsF-rpsF-ssb-mgfpmut2) tet} |

| CMJ129 | ICEBs10, pHP13, lacA::{(PrpsF-rpsF-ssb-mgfpmut2) tet} |

| CMJ130 | ICEBs1 0, pCJ44 (pHP13sso1), lacA::{(PrpsF-rpsF-ssb-mgfpmut2) tet} |

| CMJ131 | ICEBs1 0, pCJ45 (pHP13sso1R), lacA::{(PrpsF-rpsF-ssb-mgfpmut2) tet} |

| LDW21 | Δ(rapI-phrI)342::kan, amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) spc} |

| LDW22 | Δsso1-13, Δ(rapI-phrI)342::kan, amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) spc} |

| LDW50 | Δsso1-13, Δ(conG-yddM)39::kan, amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) cat}, thrC325::{(ICEBs1-311 ΔattR::tet) mls} |

| LDW52 | Δsso1-13, Δ(yddB-yddM)41::kan, amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) cat}, thrC325::{(ICEBs1-311 ΔattR::tet) mls} |

| LDW87 | Δsso1-13, Δ(conG-yddM)39::kan, amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) spc} |

| LDW89 | Δsso1-13, Δ(yddB-yddM)41::kan, amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) spc} |

| LDW129 | Δ(ydcS-yddM)93::kan, amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) spc}, thrC325::{(ICEBs1-311 ΔattR::tet) mls} |

| LDW131 | Δ(ydcS-yddM)93::kan, amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) spc} |

| LDW179 | Δ(sso1-yddM)177::kan, amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) spc}, thrC325::{(ICEBs1-311 ΔattR::tet) mls} |

| LDW180 | Δ(sso1-yddM)177::kan, amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) spc} |

We found that this activity of sso1 was orientation-specific. pHP13 containing sso1 in the reverse orientation, pHP13sso1R, (pCJ45) (strain CMJ102) was not stabilized. After approximately 20 generations of non-selective growth, 13% (13/100) of colonies tested had lost pHP13sso1R. These measurements of stability of pHP13 and derivatives are consistent with previous reports analyzing the stability of pHP13 and its sso+ parent plasmid pTA1060 [39]. Our results are most consistent with the notion that the fragment from ICEBs1 cloned into pHP13 functions as an sso. However, our results might also indicate that the cloned sequence could function as a partitioning site, or increase plasmid copy number, or somehow stabilize the plasmid by a mechanism separate from a possible function as an sso.

Visualization of sso1 activity in live, individual cells

To further test the function of sso1 from ICEBs1, we visualized ssDNA in living cells using a fusion of the B. subtilis single strand DNA binding protein (Ssb) to green fluorescent protein (Ssb-GFP). Cells contained either no plasmid, pHP13, pHP13sso1, or pHP13sso1R. We measured the intensity and area of the Ssb-GFP foci and calculated the percentage of cells containing at least one large intense focus (Materials and Methods). Under the growth conditions used, virtually all plasmid-free cells contained at least one focus of Ssb-GFP (Fig 3A), most likely associated with replication forks, as described previously [40,41]. Of these plasmid-free cells with foci of Ssb-GFP, approximately 5% (344 total cells observed) contained a large bright focus (evaluated using ImageJ with defined intensities described in Materials and Methods).

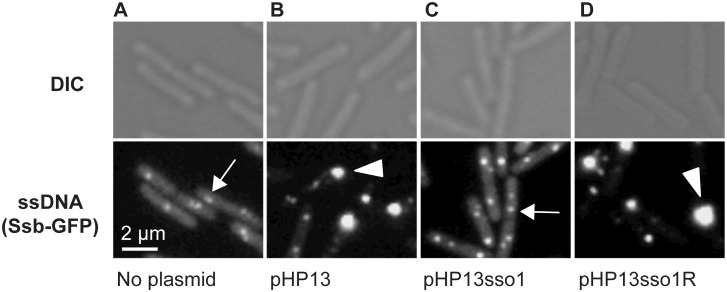

Fig 3. Visualization of Sso function in living cells.

All cells expressed Ssb-GFP, which binds to ssDNA. Top and bottom panels are images from differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence microscopy, respectively. Representative images are shown. (A) no plasmid, strain CMJ118. The small foci of Ssb-GFP are likely located at the replication forks [40]. One focus of Ssb-GFP is indicated with an arrow. (B) pHP13 (no sso), strain CMJ129. Large foci of Ssb-GFP foci were observed in cells that contain pHP13, a plasmid that replicates by a rolling circle mechanism but does not contain an sso. An arrowhead marks one large focus, indicating that Ssb-GFP likely bound to pHP13 ssDNA. (C) pHP13sso1, strain CMJ130. Cells containing pHP13sso1 did not have as many large foci of Ssb-GFP as those in panel B. An arrow indicates a small focus similar to those observed in cells with no plasmid (panel A). (D) pHP13sso1R, strain CMJ131. Cells containing pHP13 with ICEBs1 sso1 cloned in the reverse orientation had large foci of Ssb-GFP, indicating the accumulation of ssDNA. An arrowhead highlights a large focus, similar to the large foci observed in cells with pHP13 (no sso) (panel B).

In contrast to the plasmid-free cells, approximately 38% of cells (of 830 total cells observed) containing pHP13 (no sso) had a large bright focus of Ssb-GFP (Fig 3B) in addition to the smaller foci found in plasmid-free cells. Like the plasmid-free cells, only ~4% of cells (521 total cells counted) containing pHP13sso1 had large foci of Ssb-GFP (Fig 3C). This is consistent with the expectation that there should be less ssDNA in cells with the plasmid with an sso. In contrast, approximately 45% of cells (of 939 total cells counted) containing pHP13sso1R had a large focus of Ssb-GFP (Fig 3D). Based on these results we suggest that the large foci were due to the accumulation of pHP13 ssDNA bound by Ssb-GFP, that ICEBs1 sso1 reduces accumulation of single-stranded plasmid DNA, and that the function of sso1 is orientation specific.

sso1 decreases binding of Ssb-GFP to plasmid DNA

We verified that Ssb-GFP was bound to plasmid DNA using chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR). We crosslinked protein and DNA using formaldehyde, immunoprecipitated Ssb-GFP with anti-GFP antibodies, and measured plasmid DNA in the immunoprecipitates with PCR primers specific to part of pHP13 (Materials and Methods). We found that the relative amount of plasmid DNA associated with Ssb-GFP was 25-30-fold greater in cells containing pHP13 (no sso) than that in cells containing pHP13sso1 (Fig 4A). This activity of sso1 was also orientation specific as the amount of pHP13sso1R DNA associated with Ssb-GFP was similar to that of pHP13 (without an sso). The inserts did not significantly alter the relative quantity of plasmid DNA in medium containing antibiotic (Fig 4B), consistent with previous analyses of pHP13-derived plasmids [39].

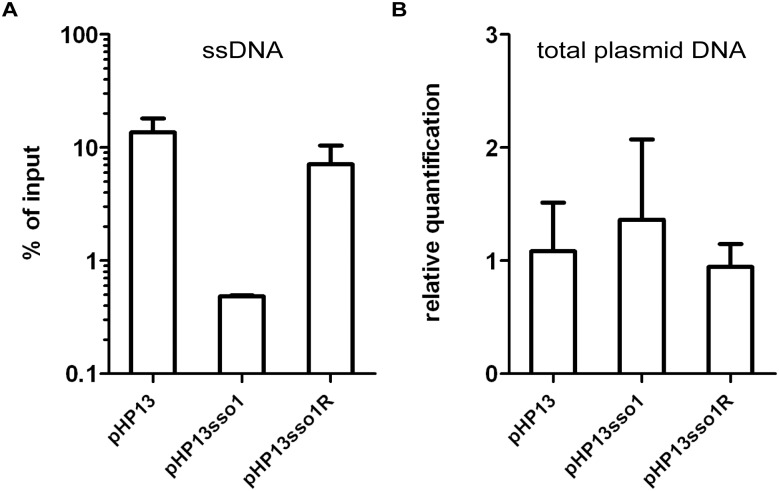

Fig 4. The amount of plasmid DNA associated with Ssb-GFP was decreased in the plasmid with sso1.

We measured the relative amount of plasmid DNA associated with Ssb-GFP (A) and the relative amount of total plasmid (B), for plasmids with and without sso1. Strains containing the indicated plasmid were: CMJ129 (pHP13); CMJ130 (pHP13sso1); and CMJ131 (pHP13sso1R). (A) Association of plasmid DNA with Ssb-GFP was measured by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with polyclonal anti-GFP followed by qPCR with primers to detect cat in pHP13. The plasmid qPCR signal from immunoprecipitated DNA was normalized to the qPCR signal in pre-immunoprecipitation lysates (% of input) [42]. Data are from one representative experiment of 6 independent experiments. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of technical triplicates. (B) Relative quantification of plasmid DNA was determined by qPCR. Plasmid abundance (pHP13 cat) was normalized to a control chromosomal locus (ydbT), and the abundance of pHP13sso1 and pHP13sso1R was normalized relative to pHP13. Data are averages from 5 independent experiments ± standard deviation.

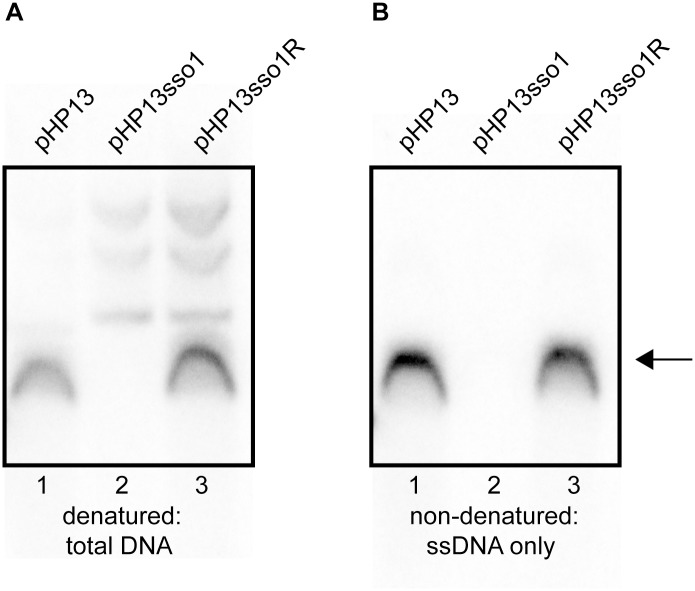

sso1 reduces the proportion of single-stranded plasmid DNA

To further test the function of sso1, we used Southern blots to compare the amounts of single and double-stranded plasmid DNA in cells containing pHP13, pHP13sso1, and pHP13sso1R. An RCR plasmid without an sso generates a greater fraction of ssDNA than the same plasmid with a functional sso [29] The approach to distinguish dsDNA and ssDNA is to compare two Southern blots, one in which the DNA is denatured, and the second in which the DNA is not denatured, prior to transfer from gel to membrane. Both dsDNA and ssDNA are detected in the blot that was denatured whereas only ssDNA is detected in the blot that was not denatured. The probe used to detect the plasmids was a 32P-labeled ~1 kb DNA fragment complementary to cat in pHP13. The probe was labeled on the strand complementary to the template strand for second strand (sso1-driven) synthesis.

We detected plasmid DNA in Southern blots with DNA that had been denatured prior to transfer to membranes (Fig 5A). There was one major DNA species from cells containing pHP13 (Fig 5A, lane 1) or pHP13sso1R (Fig 5A, lane 3). This species was not detectable in cells containing pHP13sso1 (Fig 5A, lane 2). However, slower-migrating DNA bands were detected from pHP13sso1-containing cells (Fig 5A, lane 2).

Fig 5. Southern blot analysis demonstrates that sso1 decreases the amount of plasmid ssDNA.

The relative amounts of plasmid DNA were determined for the indicated plasmids. Strains containing the plasmids were: CMJ77 (pHP13); CMJ78 (pHP13sso1); and CMJ102 (pHP13sso1R). The probe was 32P-labeled ssDNA from cat in pHP13 (Materials and Methods). The arrow to the right indicates single-stranded plasmid DNA. All three plasmids produced slower-migrating bands that were only detected when DNA was denatured, although these bands are faint for pHP13 in the exposure and experiment shown. Similar results were obtained in at least three independent experiments. (A) DNA on the filters was denatured and then probed for plasmid sequences. DNA that was either double-stranded or single-stranded before blotting is detected. (B) DNA on the filter was not denatured. In this blot, only DNA that was single-stranded before transfer to the filter is detected. ssDNA from pHP13sso1 was not readily detected in the Southern blots, but was detected in the ChIP-qPCR experiments with Ssb-GFP (Fig 4). This is likely due to amplification from PCR in the ChIP experiments.

To measure single-stranded plasmid DNA, we probed DNA that had not been denatured before transfer. As expected, cells containing pHP13 had readily detectable levels of single-stranded plasmid DNA (Fig 5B, lane 1). This band corresponded to the major band observed in the denaturing blot (Fig 5A, lane 1). In contrast, cells containing pHP13sso1 had barely detectable levels of single-stranded plasmid DNA (Fig 5B, lane 2), consistent with a drop in the proportion of ssDNA of the plasmid with the sso. pHP13sso1 plasmid DNA was detectable under denaturing conditions (Fig 5A, lane 2), demonstrating that the low signal of pHP13sso1 ssDNA was not due to lack of plasmid DNA in the sample. The effect of sso1 on ssDNA content was orientation specific as cells with pHP13sso1R had single-stranded plasmid (Fig 5B, lane 3), comparable to that detected in the denaturing blot (Fig 5A, lane 3).

These data indicate that ICEBs1 sso1, when present on pHP13, reduced accumulation of the ssDNA replication intermediate of pHP13. The findings are consistent with the analyses of Ssb-GFP foci and association with plasmid DNA. Based on this combination of data, we conclude that sso1 from ICEBs1 is a functional single strand origin of replication that enables second strand DNA synthesis to an RCR plasmid in an orientation-specific manner.

Deletion of sso1 in ICEBs1 and an additional region that is redundant with sso1

To test the function of sso1 in the context of ICEBs1, we constructed a deletion of sso1 (Fig 1B, Δsso1) and measured conjugation efficiency. Disappointingly, the conjugation frequency of ICEBs1 Δsso1 was indistinguishable from that of ICEBs1 sso1+ (~1% transconjugants per donor for both ICEBs1 Δsso1 and ICEBs1 sso1+). This result could indicate that sso1 does not function during ICEBs1 conjugation, or that there is at least one other way to convert ssDNA to dsDNA in transconjugants.

If there are other regions of ICEBs1 that provide the ability to synthesize the second strand of DNA, then removal of such regions should uncover a phenotype for sso1 in ICEBs1. We found that removal of ICEBs1 DNA from ydcS to yddM (Fig 1) revealed the role of sso1 in the ICEBs1 life cycle. We made two versions of this deletion derivative of ICEBs1, one with and one without sso1, referred to as mini-ICEBs1 sso1+ (Fig 1C) and mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1 (Fig 1D). These mini-ICEBs1's contain the known regulatory elements in the left end (Fig 1A), the origin of transfer (oriT) and ICEBs1 genes needed for nicking and replication, and genes and sites needed for excision and integration. The mini-ICEBs1 is functional for excision and can transfer to recipient cells using transfer functions provided in trans from a derivative of ICEBs1 that cannot excise or transfer [6]. Experiments described below (summarized in Fig 1G) indicate that single strand origin function is important for both stable acquisition by transconjugants and for maintenance in host cells following excision from the chromosome.

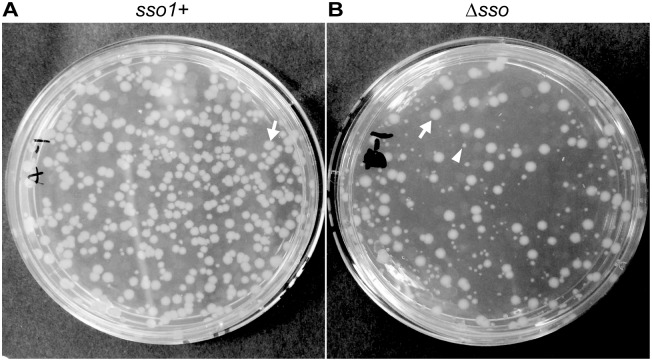

sso1 contributes to stable acquisition of ICEBs1 by transconjugants

We tested the ability of mini-ICEBs1 sso1+ and mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1 to be stably acquired by recipients in conjugation. We mated mini-ICEBs1 sso1+ (encoding kanamycin resistance) into a wild type recipient (streptomycin resistant), selecting for resistance to kanamycin and streptomycin. Donor cells also contained a derivative of ICEBs1 integrated at thrC that is able to provide conjugation functions, but that is unable to excise and transfer [6]. In these experiments, the mini-ICEBs1 is mobilized by the transfer machinery encoded by the non-excisable element at thrC. Recombination between the element at thrC and the mini-ICEBs1 would result in loss of kan from the mini-ICEBs1 and would not yield kanamycin-resistant transconjugants.

The conjugation (mobilization) efficiency of mini-ICEBs1 sso1+ was ~0.2% transconjugants per donor. Transconjugants on selective medium produced normal looking colonies (Fig 6A) that stably maintained kanamycin resistance even after propagation under non-selective conditions. We picked 50 transconjugants, streaked each on nonselective plates (LB agar, no antibiotic) to single colonies, and then picked a single colony from each isolate and restreaked, testing for resistance to kanamycin (LB agar with kanamycin). Each isolate tested (50/50) was still resistant to kanamycin. These results indicate that mini-ICEBs1 sso1+ is transferred and stably maintained in the transconjugants, analogous to the properties of wild type ICEBs1.

Fig 6. sso1 contributes to stable acquisition of ICEBs1 by recipients.

Mini-ICEBs1 with (A; strain LDW129) or without (B; strain LDW179) sso1 was crossed into recipients (strain CAL85) by conjugation. Transconjugants were selected on solid medium containing streptomycin and kanamycin. The conjugation frequency (~0.2%) is about one tenth that for wild type ICEBs1. The non-excisable element at thrC is a substrate for nicking and RCR [30,43] and produces relaxosome complexes that we suspect compete with and reduce the efficiency of transfer of the mini-ICEBs1. In addition, nicking and replication from non-excisable elements kills donor cells [43]. (A) Transconjugants that acquired mini-ICEBs1 sso1+ grew as relatively uniform, normal looking colonies. Transconjugants (including those that initially grew smaller than normal) were resistant to kanamycin after propagation under non-selective conditions, indicating that ICEBs1 was stably acquired (as described in the text). (B) Transconjugants that acquired mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1 produced at least two types of colonies, large and small. An arrow marks one large (normal) colony, and an arrowhead indicates one small colony. Most small colonies were unstable. That is, after propagation without selection, cells derived from small colonies were no longer resistant to kanamycin, indicating that ICEBs1 was not stably acquired (as described in the text).

Results with donor cells containing mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1 (strain LDW179) were different from those containing mini-ICEBs1 sso1+. The apparent conjugation (mobilization) efficiency was similar to that for mini-ICEBs1 sso1+, ~0.3% transconjugants per donor. However, there were at least two types of colonies, large and small, on the original plates (LB with kanamycin and streptomycin) selective for transconjugants (Fig 6B). The large colonies were similar in appearance to the transconjugants from mini-ICEBs1 sso1+ (Fig 6A).

In contrast to the transconjugants with the mini-ICEBs1 sso1+, many of the transconjugants receiving mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1 appeared to be unable to stably retain this element. That is, these transconjugants were no longer resistant to kanamycin after growth under non-selective conditions. We picked all the transconjugants (153) from an LB agar plate containing kanamycin and streptomycin, streaked for single colonies on non-selective plates (LB agar without antibiotics), and then tested a single colony from each of these for resistance to kanamycin. Of the 153 isolates tested, 86 (56%) were sensitive and 67 (46%) were resistant to kanamycin. Usually, but not always, the small colonies generated cells that were sensitive to kanamycin and had apparently lost mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1. The larger colonies typically generated cells that were resistant to kanamycin, indicting the stable presence of mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1. These results indicate that the mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1 was unstable in >50% of the transconjugants.

We postulate that the mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1 is unstable in the small colonies because it is unable to integrate before the initial transconjugants grow and divide. Furthermore, we postulate that there was some conversion of ssDNA to dsDNA independent of sso1 such that there was integration in some of the transconjugants. In addition, it seems likely that the initial kanamycin resistance of the transconjugants was due to expression of the kanamycin resistance gene (kan), and presumably the gene must be double-stranded to be efficiently transcribed. If this is true, it implies that integration takes time and that there is considerable cell growth and division before the mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1 can integrate. It is also possible, although we believe unlikely, that the mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1 is not converted to dsDNA. In this case, there is some other mechanism for the transconjugants to be initially resistant to kanamycin and for integration of single-stranded ICEBs1 DNA, perhaps by a relaxase- [19] or integrase- [44,45] mediated recombination event.

Our results indicate that the conversion of ICE ssDNA to dsDNA in transconjugants is important for the stable acquisition of the element. The initial molecular events in the recipient likely include entry of the linear single-stranded ICE DNA with the relaxase covalently attached to the 5' end, followed by relaxase-mediated circularization of the ssDNA. The presence of sso1 on this circular ssDNA likely enables efficient synthesis of a primer for second strand DNA synthesis. In the absence of sso1, second strand synthesis is likely less efficient, leading to loss of ICEBs1 from many of the cells. ICEs that are transferred by a type IV secretion system are all thought to enter the recipient as linear ssDNA with an attached relaxase [4]. If true, then an efficient mechanism for priming second strand DNA synthesis is likely to be critical for the stable propagation and spread of these elements.

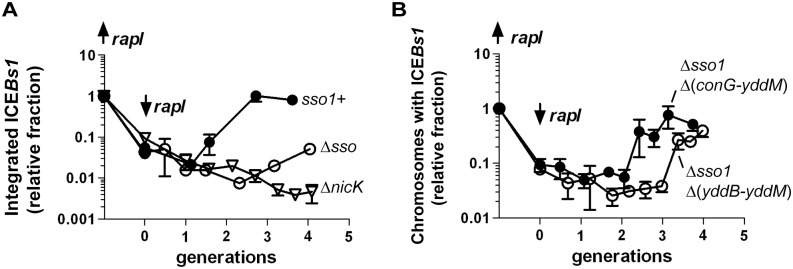

sso1 contributes to stability and replication of ICEBs1 in host cells following excision

After induction of ICEBs1 gene expression and excision from the chromosome, it takes several generations to reestablish repression and for re-integration into the chromosome [30]. Therefore, after excision from the chromosome, autonomous replication of ICEBs1 is required for its stability in host cells during growth and cell division [30].

We tested the contribution of sso1 to the stability of ICEBs1 in host cells following excision from the chromosome. We induced gene expression and excision of mini-ICEBs1 sso1+, mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1, and replication-defective ICEBs1 ΔnicK by expressing rapI from a xylose-inducible promoter (Pxyl-rapI). By two hours after expression of rapI, all three derivatives of ICEBs1 had excised normally as indicated by a >90% decrease in attL, the junction between the left end of ICEBs1 and chromosomal sequences (Fig 7A). At that time (two hours post-induction, 0 generations in Fig 7), rapI expression was repressed by removing xylose and adding glucose. We then monitored the kinetics of reintegration of mini-ICEBs1 sso1+, mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1, and ICEBs1 ΔnicK into the host chromosome using qPCR to monitor the formation of attL. If the plasmid form of the element cannot replicate, then we expect a decrease in the proportion of cells that contain an integrated element (a decrease in formation of attL) compared to that in cells with an element that can replicate. After ~4 generations (6 hours of rapI repression), mini-ICEBs1 sso1+ had reintegrated into the chromosome in ~80% of cells (assuming 100% integration before induction of ICEBs1 gene expression). In contrast, mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1 had reintegrated in ~5% of the cells (Fig 7A). This amount of integration was significantly less than that of mini-ICEBs1 sso1+, but greater than that of ICEBs1 ΔnicK (Fig 7A), indicating that mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1 is inefficiently maintained in dividing host cells but that it is more stable than the ICEBs1 mutant that is completely unable to replicate.

Fig 7. Sso activity is important for maintenance of ICEBs1 after excision in growing cells.

The relative fraction of cells with ICEBs1 integrated in its attachment site in the chromosome is plotted versus the number of generations after repression of Pxyl-rapI. Cells were grown in defined minimal medium with arabinose as carbon source. Xylose was added during mid-exponential phase to induce expression of Pxyl-rapI (origin on y-axis; up rapI), thereby causing induction and excision of ICEBs1. In all cases, ≥90% of cells had ICEBs1 excised from the chromosome two hours after induction of Pxyl-rapI. Two hours after addition of xylose, cells were pelleted and resuspended in glucose to repress expression of Pxyl-rapI (time = 0 generations; down rapI). Samples were taken for determination of the relative fraction of cells with ICEBs1 integrated in the chromosome generating attL, the junction between chromosomal sequences and ICEBs1. Data presented are from one representative experiment of at least three independent experiments. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of technical triplicates. (A) Data for mini-ICEBs1 with (sso1+; filled circles; strain LDW131) or without (Δsso; open circles; strain LDW180) sso1. ΔnicK (open triangles; strain CAL1215) is an ICEBs1 mutant that is unable to replicate autonomously and is lost from the population of cells after excision from the chromosome and continued cell growth and division [30]. (B) Data are for the indicated deletion derivatives of ICEBs1, both missing sso1 and the indicated regions: Δsso1 Δ(conG-yddM) (filled circles; strain LDW87) and the derivative missing a bit more of ICEBs1, Δsso1 Δ(yddB-yddM) (open circles; strain LDW89). Maps of the ICEBs1 mutants are in Fig 1.

We also determined the fraction of colony forming units (CFUs) that were kanamycin-resistant after four generations of growth. Cells were plated non-selectively (without antibiotic) and then individual colonies picked and tested for resistance to kanamycin. Since each of the ICEBs1 derivatives contains kan, this should be a good indication of stable integration of ICEBs1. Consistent with qPCR results, mini-ICEBs1 sso1+ was present in >95% (36/37) of cells (CFUs, plated at generation = 4) as judged by resistance to kanamycin. In contrast, <5% of cells (1/25) plated after 4 generations contained mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1. That is, only one of the 25 colonies tested had robust growth on kanamycin. Of the 24 cells that did not form robust colonies, 12 did not have any detectable growth, and 12 grew poorly on kanamycin. Since ICEBs1 DNA must presumably be double-stranded in order to integrate into the chromosome by Int-mediated site-specific recombination, and based on the results above showing that sso1 functions as a single strand origin of replication in a plasmid (pHP13), the simplest model is that sso1 also functions as a single strand origin of replication in the mini-ICEBs1, and in ICEBs1.

ICEBs1 DNA between yddB and conG is functionally redundant with sso1

Results presented above indicate that, in the context of mini-ICEBs1, sso1 has a function and causes a phenotype. However, in the context of an intact ICEBs1, loss of sso1 caused little if any detectable phenotype. Together, these results indicate that there is a region downstream of sso1 in ICEBs1 that somehow enables synthesis of the second strand of DNA. We used derivatives of ICEBs1 with different amounts of DNA downstream from sso1 to determine the location of at least one of these regions.

We found that the region between yddB and conG (Fig 1A) was at least partly functionally redundant with sso1. We compared the deletion derivative ICEBs1 Δsso1 Δ(yddB-yddM) that is missing sso1 and sequences from yddB through yddM (Fig 1E) to ICEBs1 Δsso1 Δ(conG-yddM) that is missing sso1 and sequences from conG through yddM and contains the sequences from yddB through conG (Fig 1F). As above, we measured the ability of these elements to function in conjugation and to reintegrate in host cells following induction of gene expression and excision.

Stability in transconjugants

We compared transconjugants that acquired ICEBs1 Δsso1 Δ(conG-yddM) (containing ICEBs1 DNA from yddB-conG; Fig 1F) to those that acquired ICEBs1 Δsso1 Δ(yddB-yddM) (containing ICEBs1 DNA upstream from ydcS-yddB; Fig 1E). Transconjugants that acquired ICEBs1 Δsso1 Δ(conG-yddM) were stable and produced relatively uniform colonies. In contrast, transconjugants that acquired ICEBs1 Δsso1 Δ(yddB-yddM) (Fig 1E) were unstable and colonies were heterogeneous, similar to transconjugants acquiring mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1. Transconjugants acquiring each ICEBs1 mutant were picked, purified non-selectively, and then tested for resistance to kanamycin, indicative of the presence of the mutant ICEBs1. The ICEBs1 Δsso1 derivative that contained DNA through part of conG {ICEBs1 Δsso1 Δ(conG-yddM)} was stably acquired. None of the 72 transconjugants tested had lost resistance to kanamycin after passage non-selectively. In contrast, 21 of 115 transconjugants tested that had initially acquired ICEBs1 Δsso1 Δ(yddB-yddM) were sensitive to kanamycin after passage non-selectively. That is, 18% had not stably maintained this mutant version of ICEBs1. This mutant appeared more stable than the mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1, but was less stable than the ICEBs1 Δsso1 that contains sequences from yddB-conG.

Stability in hosts following excision

We also tested the ability of each of these mutant versions of ICEBs1 to reintegrate in host cells following excision. ICEBs1 Δsso1 Δ(conG-yddM) (containing yddB-conG) was relatively stable as determined by qPCR (Fig 7B). In addition, ~94% of cells (50/53) were resistant to kanamycin four generations after repression of rapI (induction of rapI was used to induce ICEBs1 gene expression and excision). In contrast, integration of ICEBs1 Δsso1 Δ(yddB-yddM) was delayed relative to that of ICEBs1 Δsso1 Δ(conG-yddM) (containing yddB-conG) (Fig 7B). In addition, by four generations after repression of rapI, fewer than half of the cells (15/34) were resistant to kanamycin, indicating that only ~44% of the cells had stably integrated this mutant ICEBs1. Based on these results we infer that one or more regions between yddB and conG likely enables the conversion of ICEBs1 from ssDNA to dsDNA, a function at least partly redundant with that of sso1.

We tested for Sso activity in this region by cloning DNA encompassing yddB to conG, and smaller fragments between ydcS and conG, into pHP13 (lacks an sso). None of the fragments tested had a functional sso; that is, none of the regions tested enhanced second strand synthesis or stability of pHP13. Thus, this region functions differently than sso1. It is possible that this region functions as an sso only in context of oriT and ICEBs1 and not in pHP13, perhaps by requiring another region in ICEBs1 for function. It is also possible that an ICEBs1 gene product is needed for this region to enable second strand synthesis. We have not further explored these possibilities.

Single strand origins in other ICEs

Our results indicate that sso1 in ICEBs1 is functional. Based on the life cycle of ICEs, it seems likely that many (most) other functional ICEs also have at least one region capable of functioning as an Sso. Although there is relatively little sequence similarity between sso's from different plasmids and other RCR elements [24], we found that the sso of the RCR plasmid pC194 [46] from Staphylococcus aureus is identical to a region in several different ICEs from clinical isolates of Streptococcus pneumonia (Table 2). In addition, we found that an ICE from Mycoplasma fermentans has a region similar to the sso from the plasmid pT181 from S. aureus [47] and an ICE from Streptococcus suis has a region similar to the sso from the plasmid pUB110 from S. aureus [48]. The simplest notion is that each of these sequences functions as an sso for the cognate ICE.

Table 2. ICEs with regions identical or similar to known single strand origins from plasmids.

| ICE a | organism | Accession# b | plasmid c | % Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tn5253 | S. pneumoniae DP1322/BM6001 | EU351020.1 | pC194 | 100% |

| Tn1311 | S. pneumoniae SpnF21 | FN667862.2 | pC194 | 100% |

| ICE6094 | S. pneumoniae Pn19 | FR670347 | pC194 | 100% |

| ICESpn11930 | S. pneumoniae 11930 | FR671403 | pC194 | 100% |

| ICESp23FST81 | S. pneumoniae Sp264 | FM211187 | pC194 | 100% |

| ICEF-II | Mycoplasma fermentans PG18 | AY168957 | pT181 | 68% |

| ICESsu(BM407)2 | Streptococcus suis BM407 | FM252032 | pUB110 | 78% |

aICEs with regions similar to known single strand origins in RCR plasmids were identified using searches with BLASTN [80]. Tn5253 and Tn1311 were identified by BLASTN against the NCBI nucleotide collection database. All other ICEs were identified using WU-BLAST 2.0 against the ICEberg v1.0 ICE nucleotide sequence database [81].

bAccession numbers refer to the nucleotide sequence files in GenBank.

In contrast to the examples of sequence similarity (identity) described above, the function of an sso likely depends on its structure in addition to or instead of its primary sequence. For example, replacement of the sso of pBAA1 with a different primary sequence that retained secondary structure resulted in a functional sso [35]. Identification of sso's in other ICEs will likely require a combination of analyses of sequence and predicted structures and direct functional tests.

Discussion

We identified sso1, a functional single strand origin of replication in ICEBs1. sso1 was cloned into pHP13, a plasmid without an sso, and sso1 increased pHP13 stability. Furthermore, sso1 decreased accumulation of pHP13 ssDNA. Live cell imaging and ChIP-PCR experiments with Ssb-GFP indicated that there was less ssDNA from pHP13sso1 than from pHP13. Results from Southern blotting also revealed that the presence of sso1 in pHP13 caused a decrease in the amount of pHP13 ssDNA. Together, these results demonstrate that sso1 from ICEBs1 is a functional single strand origin of replication.

Genetic analyses of ICEBs1 showed that loss of sso1 and an additional region between yddB and conG led to significant defects in ICEBs1 physiology consistent with impaired replication. Specifically, deletion of these regions significantly decreased maintenance of the plasmid form of ICEBs1, thereby affecting 1) stability of ICEBs1 in host cells during growth and cell division; and 2) stable acquisition of ICEBs1 by transconjugants. Based on this functional redundancy, the simplest interpretation is that the region between yydB and conG somehow contributes to second strand synthesis, although it is currently not known how.

Sso function in ICE biology

RCR plasmids and ICEs share many functional properties. Like ICEBs1 [30] and members of the SXT/R391 family from Gram-negative bacteria [49], other ICEs may be capable of autonomous replication via a rolling circle mechanism {[30,49] and references therein}. In addition, the ICEBs1 oriT and its conjugative relaxase NicK also serve as double-stranded origin and a replicative relaxase, respectively, supporting autonomous rolling circle replication. Furthermore, some RCR plasmid replicative relaxases can serve as conjugative relaxases [50]. We have now shown an additional similarity between RCR plasmids and ICEs: the importance of Sso activity in stability of the element.

Functional ICEs appear to have a conserved lifecycle. Therefore, we suspect many other ICEs contain a single strand origin of replication to support both autonomous ICE replication in host cells and stable establishment in transconjugants. Preliminary bioinformatic analyses revealed that several ICEs contain sequences with high identity to characterized sso's from RCR plasmids (Table 2). These findings support the notion that many ICEs likely undergo autonomous rolling circle replication. We propose that they use oriT as a dso, the conjugative relaxase as a replicative relaxase, and an sso for second strand synthesis following conjugative transfer to a new host and during autonomous replication in the original host.

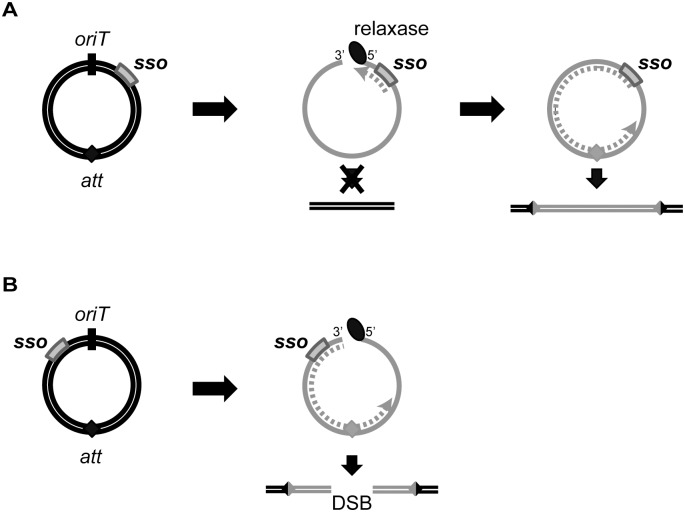

The location of sso1 relative to oriT

The location of sso1 relative to oriT in ICEBs1 could increase the probability of successful chromosome re-integration. sso1 in ICEBs1 is downstream of oriT, the double-stranded origin of replication (dso). In contrast, the sso in most RCR plasmids is upstream of the dso [23], although there are some exceptions [e.g., 28]. The positioning of an sso upstream of the dso in plasmids ensures that the sso is not single-stranded (and thus active) until leading strand synthesis from the dso is almost complete. However, the location of ICEBs1 sso1 relative to oriT ensures that the attachment site in the circular ICEBs1 (attICE, previously referred to as attP) is not double-stranded (and thus a substrate for site-specific recombination into the chromosome) until ligation and recircularization at the nic site (in oriT) occurs. Initiation of second strand synthesis from an sso upstream of oriT could result in replication of attICE before recircularization, and integration could result in a double-strand break in the chromosome (Fig 8). Thus, the location of sso's in ICEs may be an adaptation to the ICE lifecycle to prevent premature integration and possible damage to the host.

Fig 8. Model of ICE integration with an sso downstream (A) and upstream (B) of oriT.

For all ICEs, excision from the chromosome yields a dsDNA circle (concentric black circles) with an origin of transfer (oriT, black slash mark) and the attachment site, att (filled diamond). Prior to conjugation, relaxase (black oval) nicks at oriT and covalently attaches to the 5’ end. The relaxase, attached to ssDNA (gray solid line) containing the sso (gray rectangle), is transferred to recipients. In the transconjugant, the relaxase catalyzes strand ligation and formation of a ssDNA circle [reviewed in 21]. Based on known mechanisms of site-specific recombination, the att site must be double-stranded in order for the ICE to integrate into the recipient chromosome (parallel black lines). If the att site becomes dsDNA before the nicked DNA is recircularized, and if this incomplete ICE were to integrate into the chromosome, then a double strand break in the chromosome would be created. (A) The sso in an ICE is downstream from oriT. Second strand synthesis (dotted gray line) cannot proceed through oriT until the linear DNA becomes circularized. Once the att site in ICE becomes double-stranded, site-specific recombination into the chromosome can occur, and the product will be a fully integrated element with an intact genome. B) The sso in an ICE is upstream from oriT. Second strand synthesis (gray dotted line) can occur on the linear DNA, and it is possible that the att site becomes double-stranded before the ICE circularizes. If this form of ICE is capable of undergoing site-specific recombination, then integration of this linear dsDNA into the chromosome will yield a double-stranded break (DSB).

Mechanisms of second strand synthesis

RCR plasmids and conjugative plasmids have evolved multiple strategies to initiate second strand synthesis [3,24]. The F plasmid of E. coli and many RCR plasmids from Gram positives contain an sso that, when single-stranded, produces a folded structure that is recognized as a promoter by the host RNA polymerase. Transcription initiates and a short RNA serves as a primer for DNA replication [51–55]. Some plasmids (from both Gram negative and positive bacteria) contain sites that recruit the host primase DnaG, and these sites are important for plasmid replication [25,38]. The mobilizable plasmid ColE1 contains a primosome assembly site that is thought to be involved in priming of the transferred strand [3,56]. The sso of RCR plasmid pWV01 is RNA polymerase-dependent in B. subtilis [27] but has RNA polymerase-independent priming activity in Lactococcus lactis. This RNA polymerase-independent priming requires a region of the sso similar to the primosome assembly site in the phage ø174 [27]. Lastly, several conjugative or mobilizable plasmids from Gram negative bacteria encode a primase that can synthesize RNA primers on the transferred ssDNA [57,58], and primase activity can be important for conjugative transfer [59–61]. The plasmids RSF1010 and R1162 each have a primase that recognizes the plasmid origin of replication (oriV) [62,63]. The primases of ColIb and RP4 can prime a variety of ssDNA templates [58] and appear to have general primase activity that is not specific to their cognate plasmid [57,64].

sso-independent second strand synthesis

Despite the loss of regions that contribute to second strand DNA synthesis in ICEBs1, limited or inefficient second strand synthesis most likely occurs. Inefficient second strand synthesis also occurs in many RCR plasmids that are missing an sso. Plasmids without an sso can be maintained in cells and some are even used as cloning vectors [for example, 37,65]. Although the mechanisms for this sso-independent second strand synthesis are not known, one possibility is that RNA fragments that can hybridize to ssDNA could serve as primers for DNA replication. Even though elements that use rolling circle replication can function without an sso, any element with an sso, and thus an efficient mechanism for priming and completing second strand synthesis, should have a significant evolutionary advantage over elements lacking this function. We suspect that the RCR plasmids and ICEs use similar mechanisms to prime second strand synthesis when there is not an sso.

Possible functions for multiple means of second strand synthesis in ICEBs1

Based on our results, we conclude that ICEBs1 has at least two mechanisms for efficient second strand synthesis, one of which utilizes sso1. We postulate that these multiple mechanisms might increase propagation of ICEBs1 under different conditions in B. subtilis and perhaps broaden its ability to function in other hosts. For example, there might be growth stages or conditions in which use of one mechanism is inefficient. In this case, the presence of a second mechanism for second strand synthesis could allow for more efficient propagation of ICEBs1.

We also suspect that multiple modes of initiating second strand synthesis could enable ICEBs1 to transfer and propagate efficiently to multiple hosts. For example, whereas sso1 works efficiently in B. subtilis, it might not work efficiently in another organism, and a different mechanism for initiating second strand synthesis could enable spread and maintenance of ICEBs1 in such hosts. Some sso's are known to function in only one or a few host species, and host specificity is determined, in part, by the strength of host-specific RNA polymerase-sso interactions and/or the presence of other host factors [23,54]. For example, RCR plasmid pMV158 contains two sso's that are functionally redundant in Streptoccus pneumoniae. However, deletion of one of the sso's, ssoU, decreases conjugative transfer of pMV158 from S. pneumoniae to Enterrococcus faecalis by 300-1000-fold [28,66]. The conjugative module from pMV158 composed of its cognate MobM relaxase, oriT and two sso’s is widely conserved in plasmids from several Gram positive species [66]. Similarly, the primases of conjugative plasmids ColIb and RP4 are important for conjugation into some species but disposable for conjugation into others, indicating that second strand synthesis mechanisms differ between hosts [3]. We speculate that many ICEs might have two different regions that allow for conversion of ssDNA to dsDNA, perhaps enabling stable acquisition by and maintenance in different host species and thereby broadening the ICE host range.

Materials and Methods

Strains and alleles

B. subtilis strains were derived from JH642 (pheA1 trpC2) [67,68] and are listed in Table 1. Most were constructed by natural transformation. Conjugation experiments utilized recipient CAL85 that is cured of ICEBs1 (ICEBs1 0) and is resistant to streptomycin (str-84) [5]. To induce ICEBs1 gene expression in host cells, rapI was overexpressed from amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) spc} [9] or amyE::{(Pxyl-rapI) cat} [43]. Pxyl is a xylose-inducible promoter that is also repressed in the presence of glucose [69]. Construction of the non-excisable ICEBs1 in thrC325::{(ICEBs1-311 ΔattR::tet) mls}) has been described previously [7].

Most ICEBs1 derivatives contained kan, conferring resistance to kanamycin. The Δ(rapI-phrI)342::kan allele in LDW21 and LDW22 has been described [5]. The Δ(conG-yddM)39::kan and Δ(yddB-yddM)41::kan mutations have the same endpoints as alleles described previously [7]. Plasmids pCAL316 and pCAL317 containing kan and ~1 kb of DNA flanking the deletion were linearized and transformed into the ICEBs1 markerless Δsso1 mutant (Δsso1-13) to generate ICEBs1 Δsso1-13 with Δ(conG-yddM)39::kan and Δ(yddB-yddM)41::kan, respectively. PCR was used to confirm the mutations in ICEBs1 and verify that they were produced by double crossover recombination.

Δsso1-13 is a 194-nucleotide markerless deletion that fuses the 43rd and 238th nucleotides of the intergenic region between nicK and ydcS. Two 1.5 kb DNA fragments containing DNA flanking the deletion site were PCR amplified. The two fragments were fused and inserted into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of pCAL1422 (a plasmid that contains E. coli lacZ) [8] via isothermal assembly [70]. The isothermal assembly product was integrated by single crossover into B. subtilis strain IRN342 (ICEBs1 Δ(rapI-phrI)342::kan) [5]. Transformants were screened for loss of lacZ, indicating loss of the integrated plasmid, and PCR was used to identify a Δsso1 (LDW22) and wild type (LDW21) clone.

Mini-ICEBs1 sso1+ {ΔICEBs1-93 Δ(ydcS-yddM)93::kan} and mini-ICEBs1 Δsso1 {ΔICEBs1-177 Δ(sso1-yddM)177::kan} are large deletion-insertions that leave the left and right ends of ICEBs1 intact. Both deletions contain a kanamycin resistance gene that interrupts part of yddM as previously described [6]. The Δ(ydcS-yddM)93::kan deletion-insertion begins 19 bp upstream of ydcS. The Δ(sso1-yddM)177::kan deletion-insertion begins 6 bp downstream of nicK. Splice-overlap-extension PCR [71] was used to fuse a ~1 kb fragment of genomic DNA upstream of the deletion endpoint to a DNA fragment containing kan and the kan-yddM junction amplified from ΔICEBs1-205 [6].

We constructed two pHP13 derivatives to test sso1 function. Both plasmids contain sso1 (based on conservation to the Sso of plasmid pTA1060) and additional flanking sequence from ICEBs1. We used PCR to amplify a 418 bp fragment of ICEBs1 from 78 bp upstream of the 3' end of nicK to the first 76 bp of ydcS, including sso1 (Fig 1). The PCR product was ligated into the lacZ alpha complementation region of pHP13 [37,39] (NCBI accession DQ297764.1) with the multiple cloning sites, between the BamHI and EcoRI sites (pCJ44) or SalI and EcoRI sites (pCJ45). pCJ44 contains sso1 in a functional orientation and pCJ45 contains sso1 in the reverse orientation (sso1R), relative to the direction of leading strand DNA synthesis [37].

The ssb-mgfpmut2 fusion is driven by the rpsF promoter and inserted by double crossover at lacA, as described previously [40]. Strains with this fusion also contain wild type ssb at the normal chromosomal location.

Media and growth conditions

Bacillus subtilis cells were grown in LB or in MOPs-buffered S750 defined minimal medium [72]. ICEBs1-containing strains were grown in minimal medium containing arabinose (1% w/v) as the carbon source, and ICEBs1 gene expression was induced by the addition of xylose (1% w/v) to induce expression of Pxyl-rapI. Cells containing pHP13-derived plasmids were grown in liquid medium containing 2.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol to select for maintenance of the plasmid. Chloramphenicol was omitted from the growth medium when testing for maintenance of pHP13-derived plasmids as described in the text. Antibiotics were otherwise used at the following concentrations: kanamycin (5 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml), spectinomycin (100 μg/ml), tetracycline (10 μg/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and a combination of erythoromycin (0.5 μg/ml) and lincomycin (12.5 μg/ml) to select for macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin (mls) resistance.

Conjugation assays

Conjugation experiments were performed essentially as described [5,6]. Briefly, donor and recipient cells were grown in defined minimum medium containing 1% arabinose. Xylose (1%) was added to donors to induce expression of Pxyl-rapI, causing induction of ICEBs1 gene expression and excision. After two hours of growth in the presence of xylose, equal numbers of donor and recipient cells were mixed and collected by vacuum filtration on a nitrocellulose filter. Filters were incubated at 37°C for 3 hours on 1.5% agar plates containing 1X Spizizen’s salts (2 g/l (NH4)SO4, 14 g/l K2HPO4, 6 g/l KH2PO4, 1 g/l Na3 citrate-2H2O, 0.2 g/l MgSO4-7H20) [73]. Cells were washed from the filters, diluted and plated on LB agar containing streptomycin and kanamycin to select for transconjugants. Donor cell concentration was determined at the time of cell mixing (after growth in xylose for two hours) by plating donor cells on LB agar containing kanamycin. Conjugation efficiency was calculated as the ratio of transconjugants per donor.

Live cell fluorescence microscopy

Microscopy was performed essentially as described [74,75]. Briefly, mid-exponential phase cells were placed on pads of 1% agarose. Images were taken on a Nikon E800 microscope equipped with Hamatsu CCD camera and 100X DIC objective. Chroma filter set 41012 was used for GFP. The contrast and brightness of fluorescent images were initially processed using Improvision Openlabs 4.0 Software.

We measured the intensity and area of Ssb-GFP foci using ImageJ (http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). A high (conservative) global threshold was applied to every image to separate intense Ssb-GFP foci (pixel intensity ≥ 200, 8-bit image) from background. The area of each intense Ssb-GFP focus was measured using the automatic particle analysis tool. We then analyzed the distribution of the area of each focus, and used 4 pixels as a cutoff for a “large” focus (4 pixels was the third quartile for intense foci in control strain CMJ118). Finally, we counted the number of cells in the DIC image, and calculated the number of cells with at least one large, intense focus.

Southern blots

Mid-exponential phase cultures were fixed in an equal volume of ice-cold methanol. Cells were washed in NE buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) and lysed in NE buffer containing 0.5 mg/ml lysozyme for 30 min at 37°C. Sarcosyl (1% final, Sigma) and proteinase K (90 μg/ml final, Qiagen) were added, and the suspension was incubated for 20 min at 70°C. Equal volumes of phenol and chloroform were added, and the suspension was vortexed vigorously. Following centrifugation, the aqueous layer was removed and total nucleic acids were precipitated from the aqueous layer by addition of 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate and 2.5 volumes of ice-cold ethanol. The precipitate was washed once with 70% ethanol and resuspended in ddH2O overnight at room temperature.

Equal amounts of nucleic acid (~40 μg per sample) were separated on two 0.8% agarose gels. Following electrophoresis, one of the gels was soaked in an alkaline solution (0.5 M NaOH, 1.5 M NaCl) for 30 min to denature the DNA. Both gels were also soaked in neutralization buffer (2.5 M NaCl, 0.5 M Tris HCl) for 30 min. DNA was transferred to nicrocellulose membranes (Whatman) by capillary transfer, essentially as described [76]. DNA was then fixed by baking the membranes for 2 hours at 80°C. Prior to probing, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in rotating tubes containing prehybridzation buffer with formamide [76].

We used 32P-labeled probe to detect plasmid DNA. Primer CLO377 (5’-AGCACCCATT AGTTCAACAA ACG-3’, complementary to part of cat on pHP13) was end-labeled with (gamma-32P)-ATP (Perkin-Elmer) using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). Labeled oligonucleotides were separated from unincorporated ATP using Centri-Spin 10 spin columns (Princeton Separations). A region of cat from pHP13 was PCR amplified using labeled CLO377 and unlabeled primer oLW39 (5’-AGTCATTAGG CCTATCTGAC AATTCC-3’), thereby producing dsDNA with one strand labeled. The PCR product was separated from excess primers using the Qiagen PCR Purification Kit and diluted in hybridization buffer [76]. The PCR product was denatured by boiling for 1 min and immediately put on ice. Equal amounts of probe were applied to each blot (denatured and non-denatured). Membranes and probe were incubated overnight at 37°C in rotating tubes containing hybridization buffer. Excess probe was removed from the membranes by serially washing in 2X—0.1X SSC and 0.5%- 0.1% SDS. The 32P-labeled DNA was detected using a Typhoon FLA 9500 phosphorimager.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP-qPCR was used to measure the association of Ssb-GFP with pHP13-derived plasmid DNA and was carried out essentially as described [77,78]. Briefly, DNA-protein complexes were crosslinked with formaldehyde. Ssb-GFP was immunoprecipitated with rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP antibodies (Covance). qPCR was used to determine the relative amount of plasmid DNA that was bound to Ssb-GFP [42]. We used primers specific to the cat gene in the pHP13 backbone to amplify DNA in both immunoprecipitates and in pre-immunoprecipitation lysates (representing the total input DNA). Values from immunoprecipitates were normalized to those of total input DNA (% of input) [42].

We also determined the amount of total plasmid in each strain relative to control strain CMJ129 using the ΔΔCp method [79]. DNA was amplified from pre-immunoprecipitated lysates, and values obtained for plasmid gene cat were normalized to chromosomal locus ydbT. Primers to cat were oLW104 (5’-GCGACGGAGA GTTAGGTTAT TGG-3’) and oLW107 (5’-TTGAAGTCAT TCTTTACAGG AGTCC-3’). Primers to ydbT were described [8].

Integration of ICEBs1

We used qPCR to determine if ICEBs1 was integrated into the chromosomes of transconjugants. We measured attL, the junction between the chromosome and the left end of ICEBs1 and attB, the chromosomal attachment site without ICEBs1 using primer pairs specific for each region [5,30].

We also used qPCR to measure reintegration of ICEBs1 into the chromosome of cells from which it originally excised. In these experiments, host cells with ICEBs1 integrated in the chromosome at attB were grown in defined minimal medium with 1% arabinose. Expression of Pxyl-rapI was induced with 1% xylose, causing induction of ICEBs1 gene expression and excision. After two hours of growth, cells were pelleted and resuspended (to an OD600 of 0.05) in minimal medium with 1% glucose (and no xylose) to repress expression of Pxyl-rapI and eventually restore repression of ICEBs1 gene expression. DNA was extracted at various times after repression of Pxyl-rapI from 1–2 ml of cell culture using the Qiagen DNEasy tissue kit protocol for Gram-positive bacteria.

We determined the amount of reintegrated ICEBs1 relative to uninduced cells (before expression of Pxyl-rapI) using the ΔΔCp method [79]. ICEBs1 reintegration was determined by quantifying the amount of attL, the junction between the chromosome and the left end of ICEBs1 [30], relative to the amount of the nearby chromosomal locus ydbT. Values were normalized to uninduced cells in which ICEBs1 is integrated in a single copy in the chromosome.

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Laub and S. Bell for useful discussions and C. Lee and M. Viswanathan for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

Research reported here is based on work supported, in part, by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01GM050895 to ADG. LDW was supported, in part, by the NIGMS Pre-Doctoral Training Grant, T32GM007287. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Frost LS, Leplae R, Summers AO, Toussaint A (2005) Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 3: 722–732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guglielmini J, Quintais L, Garcillan-Barcia MP, de la Cruz F, Rocha EP (2011) The repertoire of ICE in prokaryotes underscores the unity, diversity, and ubiquity of conjugation. PLoS Genet 7: e1002222 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilkins B, Lanka E (1993) DNA Processing and Replication during Plasmid Transfer between Gram-Negative Bacteria In: Clewell DB, editor. Bacterial Conjugation: Springer; US: pp. 105–136. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alvarez-Martinez CE, Christie PJ (2009) Biological diversity of prokaryotic type IV secretion systems. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73: 775–808. 10.1128/MMBR.00023-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Auchtung JM, Lee CA, Monson RE, Lehman AP, Grossman AD (2005) Regulation of a Bacillus subtilis mobile genetic element by intercellular signaling and the global DNA damage response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 12554–12559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lee CA, Auchtung JM, Monson RE, Grossman AD (2007) Identification and characterization of int (integrase), xis (excisionase) and chromosomal attachment sites of the integrative and conjugative element ICEBs1 of Bacillus subtilis . Mol Microbiol 66: 1356–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lee CA, Grossman AD (2007) Identification of the origin of transfer (oriT) and DNA relaxase required for conjugation of the integrative and conjugative element ICEBs1 of Bacillus subtilis . J Bacteriol 189: 7254–7261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thomas J, Lee CA, Grossman AD (2013) A conserved helicase processivity factor is needed for conjugation and replication of an integrative and conjugative element. PLoS Genet 9: e103198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Berkmen MB, Lee CA, Loveday EK, Grossman AD (2010) Polar positioning of a conjugation protein from the integrative and conjugative element ICEBs1 of Bacillus subtilis . J Bacteriol 192: 38–45. 10.1128/JB.00860-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeWitt T, Grossman AD (2014) The bifunctional cell wall hydrolase CwlT is needed for conjugation of the integrative and conjugative element ICEBs1 in Bacillus subtilis and B. anthracis . J Bacteriol 196: 1588–1596. 10.1128/JB.00012-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burrus V, Pavlovic G, Decaris B, Guedon G (2002) The ICESt1 element of Streptococcus thermophilus belongs to a large family of integrative and conjugative elements that exchange modules and change their specificity of integration. Plasmid 48: 77–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Auchtung JM, Lee CA, Garrison KL, Grossman AD (2007) Identification and characterization of the immunity repressor (ImmR) that controls the mobile genetic element ICEBs1 of Bacillus subtilis . Mol Microbiol 64: 1515–1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bose B, Auchtung JM, Lee CA, Grossman AD (2008) A conserved anti-repressor controls horizontal gene transfer by proteolysis. Mol Microbiol 70: 570–582. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06414.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lawley TD, Klimke WA, Gubbins MJ, Frost LS (2003) F factor conjugation is a true type IV secretion system. FEMS Microbiol Lett 224: 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ohki M, Tomizawa J (1968) Asymmetric transfer of DNA strands in bacterial conjugation. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 33: 651–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yusibov VM, Steck TR, Gupta V, Gelvin SB (1994) Association of single-stranded transferred DNA from Agrobacterium tumefaciens with tobacco cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 2994–2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tinland B, Hohn B, Puchta H (1994) Agrobacterium tumefaciens transfers single-stranded transferred DNA (T-DNA) into the plant cell nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91: 8000–8004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Willetts N, Wilkins B (1984) Processing of plasmid DNA during bacterial conjugation. Microbiol Rev 48: 24–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Draper O, Cesar CE, Machon C, de la Cruz F, Llosa M (2005) Site-specific recombinase and integrase activities of a conjugative relaxase in recipient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102: 16385–16390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lanka E, Wilkins BM (1995) DNA processing reactions in bacterial conjugation. Annu Rev Biochem 64: 141–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chandler M, de la Cruz F, Dyda F, Hickman AB, Moncalian G, et al. (2013) Breaking and joining single-stranded DNA: the HUH endonuclease superfamily. Nat Rev Microbiol 11: 525–538. 10.1038/nrmicro3067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rajeev L, Malanowska K, Gardner JF (2009) Challenging a paradigm: the role of DNA homology in tyrosine recombinase reactions. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73: 300–309. 10.1128/MMBR.00038-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Khan SA (2005) Plasmid rolling-circle replication: highlights of two decades of research. Plasmid 53: 126–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Khan SA (1997) Rolling-circle replication of bacterial plasmids. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 61: 442–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Masai H, Arai K (1996) Mechanisms of primer RNA synthesis and D-loop/R-loop-dependent DNA replication in Escherichia coli . Biochimie 78: 1109–1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meijer WJ, van der Lelie D, Venema G, Bron S (1995) Effects of the generation of single-stranded DNA on the maintenance of plasmid pMV158 and derivatives in different Bacillus subtilis strains. Plasmid 33: 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Seegers JF, Zhao AC, Meijer WJ, Khan SA, Venema G, et al. (1995) Structural and functional analysis of the single-strand origin of replication from the lactococcal plasmid pWV01. Mol Gen Genet 249: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lorenzo-Diaz F, Espinosa M (2009) Lagging-strand DNA replication origins are required for conjugal transfer of the promiscuous plasmid pMV158. J Bacteriol 191: 720–727. 10.1128/JB.01257-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gruss AD, Ross HF, Novick RP (1987) Functional analysis of a palindromic sequence required for normal replication of several staphylococcal plasmids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84: 2165–2169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee CA, Babic A, Grossman AD (2010) Autonomous plasmid-like replication of a conjugative transposon. Mol Microbiol 75: 268–279. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06985.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, et al. (1997) Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 3389–3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Uozumi T, Ozaki A, Beppu T, Arima K (1980) New cryptic plasmid of Bacillus subtilis and restriction analysis of other plasmids found by general screening. J Bacteriol 142: 315–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Meijer WJ, Wisman GB, Terpstra P, Thorsted PB, Thomas CM, et al. (1998) Rolling-circle plasmids from Bacillus subtilis: complete nucleotide sequences and analyses of genes of pTA1015, pTA1040, pTA1050 and pTA1060, and comparisons with related plasmids from gram-positive bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Rev 21: 337–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Notredame C, Higgins DG, Heringa J (2000) T-Coffee: A novel method for fast and accurate multiple sequence alignment. J Mol Biol 302: 205–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Seery L, Devine KM (1993) Analysis of features contributing to activity of the single-stranded origin of Bacillus plasmid pBAA1. J Bacteriol 175: 1988–1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zuker M (2003) Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Research 31: 3406–3415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Haima P, Bron S, Venema G (1987) The effect of restriction on shotgun cloning and plasmid stability in Bacillus subtilis Marburg. Mol Gen Genet 209: 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bruand C, Ehrlich SD, Janniere L (1995) Primosome assembly site in Bacillus subtilis . EMBO J 14: 2642–2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bron S, Meijer W, Holsappel S, Haima P (1991) Plasmid instability and molecular cloning in Bacillus subtilis . Res Microbiol 142: 875–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Berkmen MB, Grossman AD (2006) Spatial and temporal organization of the Bacillus subtilis replication cycle. Mol Microbiol 62: 57–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Wagner JK, Marquis KA, Rudner DZ (2009) SirA enforces diploidy by inhibiting the replication initiator DnaA during spore formation in Bacillus subtilis . Mol Microbiol 73: 963–974. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06825.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]