Abstract

Prepartying is often associated with increased alcohol consumption and negative alcohol-related consequences among college students. General drinking motives are often only weakly related to preparty alcohol use, and few studies have examined the associations between preparty-specific drinking motives and alcohol-related consequences that occur during or after a preparty event. The current study utilizes event-level data to address this gap in the literature by examining the relationship between four types of preparty motives (prepartying to relax or loosen up, to increase control over alcohol use, to meet a dating partner, and to address concerns that alcohol may not be available later) and alcohol consequences as a function of gender. Participants (N = 952) reported on their most recent preparty event in the past month. After controlling for general drinking motives, all four preparty motives predicted greater event-level consequences for both males and females. Further, prepartying to increase control over alcohol consumed was associated with greater consequences for males as compared to females. The findings are consistent with research suggesting that preparty specific motives may further our understanding of prepartying outcomes over and above the use of general drinking motive measures.

Keywords: Preparty, Pregame, College students, Alcohol consequences, Motives

1. Introduction

Prepartying (also called pregaming, pre-loading, or pre-drinking) is defined as the “consumption of alcohol prior to attending an event or activity (e.g., party, bar, concert) at which more alcohol may be consumed” (Pedersen & LaBrie, 2007, p. 2). Over 75% of college drinkers report engaging in this activity (DeJong, DeRicco, & Schneider, 2010; Pedersen & LaBrie, 2007) and students who preparty consume more alcohol and experience a greater number of negative alcohol-related consequences than students who do not preparty (Borsari et al., 2007; Hummer, Napper, Ehret, & LaBrie, 2013; Kenney, Hummer, & LaBrie, 2010; LaBrie & Pedersen, 2008; Pedersen & LaBrie, 2007). Research exploring why students preparty could help further our understanding of this high-risk pattern of alcohol use and inform interventions aimed at reducing negative outcomes.

1.1 Drinking and Preparty Motives

Drinking motives (e.g., social, coping, enhancement and conformity motives; Cooper, 1994; Cooper, Russell, Skinner, & Windle, 1992) are important predictors of alcohol use and negative consequences and have been found to mediate the relationship between psychosocial antecedents (e.g., expectancies, impulsivity) and drinking outcomes (Read, Wood, Kahler, Maddock, & Palfai, 2003). Although there is a large body of research supporting the utility of these general drinking motives, there is also growing recognition that more context specific drinking motives may be beneficial for understanding drinking behavior in high-risk situations (Bachrach, Merrill, Bytschkow, & Read, 2012; Johnson & Sheets, 2004; LaBrie, Hummer, Pedersen, & Chithambo, 2012). With respect to prepartying, studies suggest that general drinking motives are often unrelated to, or only weakly correlated with preparty drinking outcomes (Pedersen & LaBrie, 2007; Read, Merrill, & Bytschkow, 2010; Zamboanga et al., 2011). Further, students commonly report prepartying for reasons not captured by measures of general drinking motives (e.g., saving money or getting buzzed prior to going out; Pedersen, LaBrie, & Kilmer, 2009; Read et al., 2003). In a study examining the role of both general and preparty specific motives, preparty specific motives predicted preparty quantity and frequency after controlling for general drinking motives (Bachrach et al., 2012). These findings suggest that there may be unique reasons for prepartying that are not captured by measures of general drinking motives. In addition to omitting context specific reasons for drinking, measures of general drinking motives may also include content that is less relevant to prepartying. Bachrach and colleagues (2012) posit that preparty behavior may be motivated more by a desire to enhance positive affect than elevate negative affect, and therefore general coping motives may be less relevant to the preparty context.

In addition to research comparing the role of general and specific preparty motives, researchers have begun to explore the relationship between different preparty specific motives and preparty outcomes. Preparty motives related to interpersonal enhancement (e.g., loosen up), situational control (e.g., controlling type of alcohol consumed), intimate pursuit (e.g., increasing one’s likelihood of meeting a dating partner), and barriers to consumption (e.g., not being able to obtain alcohol later) all appear to be positively related to quantity of alcohol consumed and frequency of prepartying (LaBrie et al., 2012). Relatively little research has examined the relationship between preparty motives and negative consequences of drinking. In a path model, Bachrach and colleagues (2012) found that prepartying either to have fun or for instrumental reasons was indirectly related to drinking consequences through greater frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption when prepartying. In contrast, prepartying to ease social situations was not related to alcohol consumption, but was directly related to greater alcohol-related consequences. While these findings indicate that preparty motives may be directly and indirectly related to consequences, this study examined global alcohol consequences experienced during a one-month period. Research examining consequences specific to prepartying would help further elucidate the relationship between drinking motives and negative consequences.

1.2 Gender Differences in Motives and Prepartying

While male college students have traditionally been found to drink more and experience greater alcohol-related consequences than female students (for review see Ham & Hope, 2003), research on gender differences in preparty behaviors is less clear. Some research indicates similar rates of prepartying, levels of alcohol consumption during prepartying, BACs on days when prepartying occurred, and experiences of alcohol-related negative consequences for males and females (Hummer et al., 2013; LaBrie & Pedersen, 2008; Pedersen & LaBrie, 2007; Reed et al., 2011). Some of these same studies and others have also found evidence that in comparison to females, males preparty more often (Bachrach et al., 2012), reach higher BACs when prepartying (Hummer et al., 2013), and drink more on days when prepartying occurred (LaBrie & Pedersen, 2008; Pedersen & LaBrie, 2007). There is also research to suggest that there may be gender differences in preparty motives. Pederson, LaBrie, and Kilmer (2009) found that males are more likely than females to report prepartying in order to meet members of the opposite sex, facilitate opportunities to have sex, and enjoy sporting and other events. In another study, males reported having significantly higher levels of social motives for prepartying than females (Kuntsche & Labhart, 2013). In terms of alcohol-related consequences, stronger enhancement motives were predictive of more consequences among males, whereas stronger coping motives were predictive of more consequences among females (Kuntsche & Labhart, 2013).

Research examining general drinking motives suggests that gender moderates the relationship between drinking motives and preparty drinking outcomes. For example, Pederson and LaBrie (2007) examined the relationship between general drinking motives and preparty frequency. While all four general drinking motives (e.g., social, enhancement, coping, and conformity) were positively correlated with prepartying frequency for males, only social and enhancement motives were positively correlated to preparty frequency for females. In contrast, a study of young adults in Switzerland found that the general drinking motive of conformity was associated with greater prepartying for females, but not males (Kuntsche & Labhart, 2013). Further, with respect to alcohol-related consequences, enhancement motives were a stronger predictor among males, whereas coping motives were a stronger predictor among females. These conflicting results may represent differences in culture or study design (Kuntsche & Labhart, 2013). Studies utilizing measures of preparty specific motives instead of general motives could help clarify possible gender differences in the relationship between motives and preparty alcohol-related consequences. If gender differences exist, interventions could be tailored to male and female students in order to more effectively reduce negative outcomes associated with prepartying.

1.3 Current Study

The present study extends previous research by examining the unique relationship between preparty specific motives (e.g., interpersonal enhancement, situational control, intimate pursuit, and barriers to consumption) and alcohol-related consequences that occurred during or after a preparty event after controlling for general drinking motives. While past research examining this relationship has employed global measures of alcohol consequences (Bachrach et al., 2012), the current study reexamined event-level data described by Hummer and colleagues (2013) in order to explore more specifically whether preparty drinking motives are associated with negative outcomes experienced during or after a preparty event. This event-level approach has previously been used to examine how the specific context of prepartying contributes to alcohol use and consequences (Borsari et al., 2007; LaBrie & Pedersen, 2008) and could shed light on motivational factors that increase the negative outcomes associated with prepartying specifically.

Based on prior research (Bachrach et al., 2012), we predict that preparty motives associated with interpersonal enhancement will be more strongly associated with negative alcohol-related consequences than other preparty motives. The present study extends past research by examining the potential moderating effect of gender on the relationship between preparty motives and preparty negative consequences. Given the conflicting results from past research examining gender differences in the relationship between general motives and preparty outcomes, the current study aims to help clarify this relationship by utilizing a preparty specific measure of drinking motives.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Participants were undergraduate college students (N = 952) from two west coast universities (a large public university and a medium-sized private university) who were recruited to take part in a larger alcohol intervention study designed to examine the efficacy of a norms based intervention for students reporting heavy episodic drinking (4/5 drinks in a row for women/men). Data used in the current study comes from baseline surveys completed prior to any alcohol intervention. The majority of the sample were female (64.0%), and the average age was 20.1 years. The sample racial composition was 67.4% White, 12.4% Asian, 2.6% African-American, 12.1% Multiracial, and 5.5% identified as another race. Additionally, 12% of participants reported that they were Hispanic/Latino(a). Participants reported consuming, on average, 11.6 drinks per week.

2.2 Procedure

A total of 6,000 students were invited to take part in the study via e-mail (3,000 students from each of the two universities and stratified across class year). After providing consent, participants completed an online screening survey (N = 2,767). Students who reported engaging in heavy episodic drinking at least once in the past month were invited to complete an additional baseline survey (N = 1,494). Participants who did not complete the baseline survey (N = 386) or who reported that they had not prepartied in the last 30 days (N = 156) were excluded from the current analyses (final sample, N = 952). Students received a nominal cash stipend for their participation. All procedures were approved by the respective universities’ Institutional Review Board.

2.3 Measures

2.3.1 General drinking motives

General drinking motives were assessed using the 20-item Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ-R; Cooper, 1994). The DMQ assesses four general drinking motives: Social motives (α = .89; five items, e.g., “To be sociable”), Enhancement motives (α = .87; five items, e.g., “To get high”), Coping motives (α = .87; five items, e.g., “To forget your worries”), and Conformity motives (α = .90; five items, e.g., “To be liked”). Students report how often that had drank for each of the 20 reasons in the past 30 days (almost never/never [1] to almost always/always [5]).

2.3.2 Preparty motives

Preparty motives were evaluated using the Preparty Motives Inventory (PMI; LaBrie et al., 2012). Each of the four subscales demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability: Interpersonal Enhancement (IE, six items; α = .75), Situational Control (SC, four items; α = .88), Intimate Pursuit (IP, three items; α = .82), and Barriers to Consumption (BC, three items; α = .77). Participants were presented with the list of 16 reasons for prepartying and were asked to consider how often they personally prepartied for each reason. Example items include: (1) “To pump myself up to go out” (IE item), (2) “So I don’t have to drink at the place where I am going” (SC item), (3) “To meet a potential dating partner once I go out” (IP item), and (4) “Because I am underage and cannot purchase alcohol at the destination venue” (BC item). The response options were: (1) Almost Never / Never, (2) Some of the Time, (3) Half of the Time, (4) Most of the Time, and (5) Almost Always / Always. Sum composites for each of the four subscales were calculated.

2.3.3. Negative alcohol-related consequences

A modified version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (B-YAACQ; Kahler, Strong, & Read, 2005) was used to evaluate event-specific alcohol-related consequences (see Hummer et al., 2013 for further information). Seven of the original 24 B-YAACQ items that were not relevant at the event-level (e.g. “I have been overweight because of drinking”) were excluded from the measure. Participants indicated whether they had experienced the remaining 17 alcohol-related consequences during the last occasion when they had pre-partied, the last occasion when they drank but did not preparty, on both these occasions, or on neither of these occasions. Responses were recoded into a single dummy variable to indicate whether the participant had experienced a consequence during their last preparty event (Yes = 1, No = 0). The measure included items such as “I found it difficult to limit how much I drank” and “I took foolish risks.” Responses were summed to create a measure of total number of alcohol-related consequences experienced during or immediately after the preparty event (α = .81).

2.4 Analytic Plan

To examine gender differences in preparty motives and alcohol consequences, t tests were performed. Next, Pearson’s correlation coefficients were used to examine the bivariate relationships among each of the four types of preparty motives (i.e., IE, SC, BC, IP) and alcohol-related consequences. Finally, a series of three-step hierarchical multiple regressions were conducted to examine whether: (1) each preparty motive significantly predicted preparty consequences after controlling for general drinking motives (e.g., social, enhancement, coping, and conformity), and (2) whether gender moderated the relationship between each preparty motive and alcohol-related consequences. To aid in interpretation of the results, separate models were examined for each preparty motive. General drinking motives were entered at Step 1. At Step 2, a preparty motive and gender (0 = female, 1 = male) were entered. At Step 3, the interaction term involving the respective preparty motive and gender was entered.

3. Results

The means and standard deviations for preparty motives for males and females are presented in Table 1. Significant differences in SC, BC and IP preparty motives were observed for male and female drinkers. Females scored higher on measures of situational control, t(950) = 5.39, p < .001, d = .36, and barriers to consumption than males, t(950) = 2.89, p < .01, d = .20. In contrast, males reported higher levels of prepartying for intimate pursuit motives, t(950) = 8.05, p < .001, d = .54. There were no significant gender differences in reports of prepartying for interpersonal enhancement reasons. For both genders, alcohol-related consequences were positively correlated with all four preparty motives (Table 2). There were no gender differences with respect to race or age. Male students reported consuming more drinks on the day they prepartied (M = 8.99, SD = 3.86) than females (M = 6.34, SD = 2.61), t(949) = 12.56, p < .001, d = .85 (see Hummer et al., 2013 for further details).

Table 1.

Summary of Sample Size, Means and Standard Deviations for Preparty Motives among Males and Females

| Male | Female | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 343) |

(n = 609) |

|||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | t(950) | Cohen’s d |

| IE | 3.00 | 0.99 | 2.97 | 1.01 | 0.53 | .03 |

| SC | 2.10 | 0.85 | 2.44 | 1.00 | −5.39*** | .36 |

| IP | 1.98 | 1.02 | 1.52 | 0.75 | 8.05*** | .54 |

| BC | 2.44 | 1.04 | 2.66 | 1.17 | −2.89** | .20 |

Note. IE = interpersonal enhancement preparty motive; SC = situational control preparty motive; BC = barriers to consumption preparty motive; IP = intimate pursuit preparty motive.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 2.

Correlations for Alcohol-Related Consequences and Preparty Motives for Males and Females

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Consequences | — | .35*** | .17*** | .37*** | .23*** |

| 2. | IE | .24*** | — | .35*** | .48*** | .44*** |

| 3. | SC | .26*** | .25*** | — | .22*** | .52*** |

| 4. | IP | .38*** | .57*** | .29*** | — | .30*** |

| 5. | BC | .28*** | .41*** | .48*** | .34*** | — |

Note. Correlation data for male participants is below the diagonal, data for female participants is above the diagonal. IE = interpersonal enhancement preparty motive; SC = situational control preparty motive; BC = barriers to consumption preparty motive; IP = intimate pursuit preparty motive.

p < .01.

p < .001

3.1 Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses

The results of the hierarchical multiple regression models are presented in Table 3. In terms of general drinking motives at Step 1, Drinking to cope (b = .99, p < .001) and to conform (b = .89, p < .001) were associated with greater preparty alcohol consequences. In contrast, drinking for social (b = .30, p = .06) and enhancement (b = .24, p = .11) motives were not. Further, after controlling for general drinking motives, IE preparty motives (b = .76, p <.001), SC preparty motives (b = .58, p < .001), IP preparty motives (b = 1.26, p < .001), and BC preparty motives (b = .52, p < .001) were associated with greater alcohol-related preparty consequences.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Model Predicting Alcohol-Related Consequences from General Drinking Motives, Preparty Motives, and Gender

| Preparty Motive | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Enhancement |

Situational Control | Barriers to Consumption |

Intimate Pursuit | |||||||||

| Predictor | ΔR2 | Step 3 B | SE | Δ R2 | Step 3 B | SE | Δ R2 | Step 3 B | SE | Δ R2 | Step 3 B | SE |

| Step 1: General Drinking Motives | .14*** | .14*** | .14*** | .14*** | ||||||||

| DMQ Social | .04 | .16 | .27 | .16 | .24 | .16 | .18 | .16 | ||||

| DMQ Coping | .84*** | .15 | .90*** | .15 | .89*** | .15 | .80*** | .15 | ||||

| DMQ Enhancement | .19 | .15 | .25 | .15 | .17 | .15 | .14 | .14 | ||||

| DMQ Conformity | .77*** | .18 | .87*** | .18 | .89*** | .18 | .67*** | .17 | ||||

| Step 2: Main Effects | .03*** | .02*** | .02*** | .07*** | ||||||||

| Preparty motive | .55** | .20 | .96*** | .23 | .57** | .19 | 1.08*** | .19 | ||||

| Gender | −.79 | .76 | 1.20 | .64 | .27 | .61 | .13 | .52 | ||||

| Step 3: Interaction | .00 | .004* | .00 | .00 | ||||||||

| Preparty Motive × Gender | .33 | .24 | −.54* | .27 | -.08 | .22 | .36 | .26 | ||||

| Multiple R2 | .18 | .17 | .16 | .21 | ||||||||

| Model F | 28.53*** | 26.77*** | 26.52*** | 36.22*** | ||||||||

Note. Regression coefficients and standard errors are reported for the final step of the regression.

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

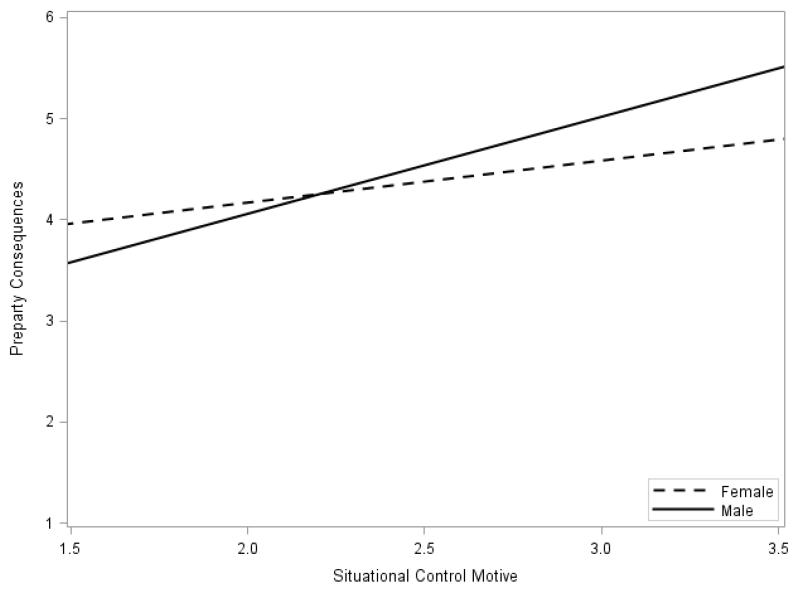

Gender did not moderate the relationship between IE (b = .33, p = .17), IP (b = .36, p = .17), or BC (b = −.08, p = .74) motives and consequences. Gender differences emerged for the relationship between SC Motives and consequences (b = −.54, p = .043). This interaction was decomposed using simple slopes analyses (Aiken & West, 1991), with slopes evaluated at values corresponding to male and female (Figure 1). For both males (b = .96, p < .001) and females (b = .42, p = .005) SC motives were associated with greater consequences; however, there was a stronger positive relationship between SC motives and consequences for male students.

Figure 1.

Effect of Situational Control (SC) motives on preparty consequences moderated by gender, controlling for general drinking motives. Values of SC motives range from the 10th to the 90th percentile in the current sample.

4. Discussion

The current findings support the unique risk-enhancing role of context specific preparty motives and advance the limited research examining the global link between preparty-specific motives and risk (Bachrach et al., 2012) using event-level data. After controlling for general drinking motives, all four preparty motives independently predicted greater preparty-related consequences among males and females reporting past month heavy episodic drinking. Further, findings revealed gender differences in students’ reasons for prepartying. Although men and women experienced a similar level of preparty-related consequences (see Hummer et al., 2013), stronger endorsement of SC motives was related to increased consequences among men. These results highlight the importance of addressing students’ context-specific motivations for prepartying as well as potential gender discrepancies in order to reduce preparty-related harms.

4.1 Preparty Motives by Gender

Among both men and women, the most commonly endorsed motive for prepartying was interpersonal enhancement and least endorsed motive was intimate pursuit. Women in this sample were more likely to endorse situational control and barriers to consumption than men. These findings may reflect women’s motivations to protect themselves while drinking (e.g., “So I don’t have to worry about whether someone has tampered with the drinks at a party” (Delva et al., 2004; Walters, Roudsari, Vader, & Harris, 2007). Consistent with past research (Pedersen et al., 2009), males were more likely than females to report prepartying in order to meet a potential dating partner or to hook up. This finding is concerning given that hookups associated with heavy drinking contexts increase the likelihood of casual sexual behaviors with unfamiliar partners, sexual coercion, and regrettable sexual encounters (LaBrie, Hummer, Ghaidarov, Lac, & Kenney, 2014; Paul & Hayes, 2002). Students may benefit from campaigns that inform them about the risks of using alcohol to meet a potential sexual partner or the sexual-based motivations of other students.

Gender moderated the relationship between SC motives and alcohol consequences. Although women more strongly endorsed SC motives overall, men who did endorse higher (as opposed to lower) SC motives faced increased risk for alcohol-related negative consequences over the course of the evening. SC motives place emphasis on reaching a desired level of intoxication at the preparty event in case drinks are difficult to secure at the next destination (e.g., “So I don’t have to drink at the place where I’m going.”). It is possible that in their attempt to avoid inconveniences of drinking at post-preparty destinations, men endorsing SC preparty motives engage in rapid and excessive drinking while prepartying that puts them at heightened risk for high BALs and associated consequences. In contrast, women may be more inclined than men to employ situational control strategies to avoid unwanted negative consequences (e.g., “So I don’t have to worry about whether someone has tampered with the drinks at the party”), and therefore may be less motivated to become heavily intoxicated.

Although limited, past research utilizing general drinking motives shows that gender may moderate the relationship between enhancement motives and consequences, with males who endorse enhancement motives more likely than females to experience negative consequences (Kuntsche & Labhart, 2013). Specific to preparty risk, however, the influence of IE, IP, or BC preparty motives do not appear to differ as a function of gender, thus indicating that for both males and females prepartying for a range of reasons is associated with greater consequences. In light of existing research that has found conflicting moderating effects of gender with respect to the general drinking motives-prepartying behavior link (Kuntsche & Labhart, 2013; Pedersen & LaBrie, 2007), studies utilizing measures specific to prepartying motives may help clarify the role of gender in prepartying risk outcomes. If gender differences are found, interventions could be tailored to male and female students to more effectively reduce preparty consequences.

4.2 General Drinking Motives

The findings also offer insight into the role of general drinking motives in preparty-related risk. Existing studies have found either nonsignificant relationships between drinking motives and prepartying alcohol use (Read et al., 2010; Zamboanga et al., 2011) or evidence that positive (social, enhancement) drinking motives predict prepartying (Bachrach et al., 2012; Pedersen & LaBrie, 2007). Although these studies suggest that prepartiers may be more motivated to enhance positive affect than reduce negative affect, in our sample, students reporting negative reinforcing reasons (coping, conformity), but not positive motives faced substantial risk for preparty-related alcohol consequences, over and above motives for prepartying specifically. These results, which may reflect our focus on preparty consequences rather than prepartying frequency, are consistent with studies showing that negative reinforcing motives (coping, conformity) for drinking are strong predictors of alcohol problems over and above drinking (Cooper, 1994; Delva et al., 2004; Kassel, Jackson, & Unrod, 2000). In contrast, social motives are generally found to be unrelated to alcohol consequences (Cooper, 1994; Merrill & Read, 2010; Walters et al., 2007) and enhancement motives are predictive of consequences only indirectly through heavy drinking (Cooper et al., 1992; Merrill & Read, 2010; Walters et al., 2007). Prepartying contexts appear to be especially risky for students endorsing coping or conformity motives for drinking who are already at heightened risk for problematic alcohol use. Future research is needed to determine the extent to which prepartying (vs. non-prepartying) contexts may exacerbate negative consequences for these student drinkers.

4.3 Implications

The findings of the current study provide important implications for researchers and practitioners interested in reducing the potential negative consequences of alcohol use among young adults. Given that the majority of college student drinkers report regularly engaging in the high-risk contexts of prepartying (Borsari et al., 2007; LaBrie et al., 2012; Pedersen & LaBrie, 2007), gaining a better understanding of students’ motivations for engaging in prepartying and associated negative consequences is particularly informative for targeted harm-reduction interventions. Interventions that address general drinking motives may fail to capture the most proximal and significant predictors of alcohol-related consequences. Rather, psychoeducational interventions that enable students to discuss their reasons for prepartying and connect these to consequences that they may experience may motivate behavior change. Further, providing students with risk reduction strategies may enable them to more safely partake in the social drinking culture on college campuses.

Although more research is needed to better understand how distinct preparty motivations may differentially influence men’s and women’s preparty behaviors and consequences, the current results indicate that situational control preparty motives may be particularly risky for men. Therefore, educating males about the biphasic effects of alcohol and providing them with strategies that may encourage them to drink at a slower pace while prepartying (e.g., bringing beverage of choice to post-preparty destination) may be particularly important.

4.4 Limitations

The current study has a number of limitations. The sample was restricted to students reporting heavy episodic drinking. Given the high prevalence rates of prepartying among college student drinkers, future research should examine the relationship between preparty motives and alcohol-related consequences among a broader sample of college student drinkers. Further, while drinking motives are postulated to predict alcohol use and associated consequences (Cooper, 1994), prospective data assessing multiple time points would help further elucidate the relationship between preparty motives and alcohol consequences. While the current study adds to a limited research utilizing event-level data to explore prepartying (Hummer et al., 2013; Zamboanga et al., 2013), more research is needed employing this approach to examine the context of drinking during prepartying and motives associated with a specific drinking occasion. For example, it is possible that preparty motives vary by occasion, and therefore event-level data for both preparty motives and consequences would be beneficial. Supplementing event-level approaches with more general, less context-specific forms of large data collection may provide a fuller understanding of patterns of behaviors and outcomes related to preparty motives and related consequences.

4.5 Conclusions

The results from the current study add to the literature on preparty risk by exploring the link between preparty-specific motives and negative alcohol-related consequences in a sample of heavy drinking college students. Moreover, the current work highlights gender differences in the relationship between preparty motives and associated consequences. Prepartying is a serious concern on college campuses, and the current study demonstrates that researchers interested in understanding risk factors for alcohol problems more generally, and preparty consequences more specifically, should address students’ motivations for prepartying.

Highlights.

Preparty motives independently predict preparty alcohol-related consequences

Prepartying to control drinking was related to more consequences for males

Negative, but not positive, general motives predicted preparty consequences

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Sources

This research was supported in part by grants 1R21AA021870-01 and T32 AA007459 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism at the National Institutes of Health. Support for Dr. Napper was provided by ABMRF/The Foundation for Alcohol Research. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAAA or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Lucy Napper, Shannon Kenney, Kevin Montes, Leslie Lewis, and Joseph LaBrie have each contributed significantly to the preparation of the manuscript. Specifically, Dr. Napper drafted and edited all sections of the manuscript and performed the statistical analyses. Dr. Kenney drafted the Discussion. Dr. Montes drafted the Introduction. Leslie Lewis drafted the Methods and assisted with the literature review. Dr. LaBrie oversaw the data collection and contributed to editing the manuscript in its entirety.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage Publications, Inc.; Thousand Oaks, CA, US: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach RL, Merrill JE, Bytschkow K, Read JP. Development and initial validation of a measure of motives for pregaming in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:1038–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.013. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Boyle KE, Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, Tevyaw TO, Kahler CW. Drinking before drinking: Pregaming and drinking games in madated students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2694–2705. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.003. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4:123–132. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.4.2.123. [Google Scholar]

- DeJong W, DeRicco B, Schneider SK. Pregaming: An exploratory study of strategic drinking by college students in Pennsylvania. Journal of American College Health. 2010;58:307–316. doi: 10.1080/07448480903380300. doi: 10.1080/07448480903380300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delva J, Smith MP, Howell RL, Harrison DF, Wilke D, Jackson DL. A study of the relationship between protective behaviors and drinking consequences among undergraduate college students. Journal of American College Health. 2004;53(1):19–27. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.1.19-27. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.1.19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Hope DA. College students and problematic drinking: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology. 2003;23:719–759. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00071-0. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummer JF, Napper LE, Ehret PE, LaBrie JW. Event-specific risk and ecological factors associated with prepartying among heavier drinking college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:1620–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.09.014. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TJ, Sheets VL. Measuring college students’ motives for playing drinking games. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18(2):91–99. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.91. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000171940.95813.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Jackson SI, Unrod M. Generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation and problem drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(2):332–340. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenney SR, Hummer JF, LaBrie JW. An examination of prepartying and drinking game playing during high school and their impact on alcohol-related risk upon entrance into college. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:999–1011. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9473-1. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9473-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Labhart F. Drinking motives moderate the impact of pre-drinking on heavy drinking on a given evening and related adverse consequences—an event-level study. Addiction. 2013;108:1747–1755. doi: 10.1111/add.12253. doi: 10.1111/add.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Ghaidarov TM, Lac A, Kenney SR. Hooking up in the college context: The event-level effects of alcohol use and partner familiarity on hookup behaviors and contentment. Journal of Sex Research. 2014;51:62–73. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.714010. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.714010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Pedersen ER, Chithambo T. Measuring college students’ motives behind prepartying drinking: Development and validation of the prepartying motivations inventory. Addictive Behaviors. 2012;37:962–969. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.003. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Pedersen ER. Prepartying promotes heightened risk in the college environment: An event-level report. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:955–959. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.02.011. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:705–711. doi: 10.1037/a0020135. doi: 10.1037/a0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul EL, Hayes KA. The casualties of “casual” sex: A qualitative exploration of the phenomenology of college students’ hookups. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2002;19:639–661. doi: 10.1177/0265407502195006. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, LaBrie JW. Partying before the party: Examining prepartying behavior among college students. Journal of American College Health. 2007;56:237–245. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.3.237-246. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.3.237-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, LaBrie JW, Kilmer JR. Before you slip into the night, you’ll want something to drink: Exploring the reasons for prepartying behavior among college student drinkers. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2009;30:354–363. doi: 10.1080/01612840802422623. doi: 10.1080/01612840802422623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill JE, Bytschkow K. Before the party starts: Risk factors and reasons for “pregaming” in college students. Journal of American College Health. 2010;58:461–472. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540523. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17(1):13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MB, Clapp JD, Weber M, Trim R, Lange J, Shillington AM. Predictors of partying prior to bar attendance and subsequent BrAC. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(12):1341–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.029. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Roudsari BS, Vader AM, Harris TR. Correlates of protective behavior utilization among heavy-drinking college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(11):2633–2644. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.022. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL, Borsari B, Ham LS, Olthuis JV, Van Tyne K, Casner HG. Pregaming in high school students: Relevance to risky drinking practices, alcohol cognitions, and the social drinking context. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25(2):340–345. doi: 10.1037/a0022252. doi: 10.1037/A0022252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL, Casner HG, Olthuis JV, Borsari B, Ham LS, Bersamin M, Pedersen E. Knowing where they’re going: Destination-specific pregaming behaviors in a multiethnic sample of college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;69:383–396. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21928. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]