Abstract

Background

The age at which heart failure develops varies widely between countries and drug tolerance and outcomes also vary by age. We have examined the efficacy and safety of LCZ696 according to age in the Prospective comparison of angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and Morbidity in Heart Failure trial (PARADIGM-HF).

Methods

In PARADIGM-HF, 8399 patients aged 18–96 years and in New York Heart Association functional class II–IV with an LVEF ≤40% were randomized to either enalapril or LCZ696. We examined the pre-specified efficacy and safety outcomes according to age category (years): <55 (n = 1624), 55–64 (n = 2655), 65–74 (n = 2557), and ≥75 (n = 1563).

Findings

The rate (per 100 patient-years) of the primary outcome of cardiovascular (CV) death or heart failure hospitalization (HFH) increased from 13.4 to 14.8 across the age categories. The LCZ696:enalapril hazard ratio (HR) was <1.0 in all categories (P for interaction between age category and treatment = 0.94) with an overall HR of 0.80 (0.73, 0.87), P < 0.001. The findings for HFH were similar for CV and all-cause mortality and the age category by treatment interactions were not significant. The pre-specified safety outcomes of hypotension, renal impairment and hyperkalaemia increased in both treatment groups with age, although the differences between treatment (more hypotension but less renal impairment and hyperkalaemia with LCZ696) were consistent across age categories.

Interpretation

LCZ696 was more beneficial than enalapril across the spectrum of age in PARADIGM-HF with a favourable benefit–risk profile in all age groups.

Keywords: Heart failure, Neprilysin, Receptors, Angiotensin, Age

Introduction

The age at which heart failure develops varies widely between countries.1–4 Although characteristically considered a condition of the elderly in Western Europe and North America, patients with heart failure in other regions of the world such as Asia and Latin America are often much younger.1–4 This is one reason why the average age of patients with heart failure in large international trials is typically a decade or more younger than in clinical practice in the northern hemisphere. Trial exclusion criteria based on comorbidity and other factors may also lead to fewer elderly than younger patients being enrolled in trials.1–4

Understandably, however, physicians who treat older individuals want to know about the efficacy and tolerability of new treatments in their patients. For this reason, we have conducted an analysis of outcomes in the Prospective comparison of angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and morbidity in Heart Failure trial (PARADIGM-HF) according to age PARADIGM-HF randomized 8399 patients aged 18–96 years in 47 countries to treatment with enalapril 10 mg twice daily or the ARNI LCZ696 (sacubitril-valsartan) 200 mg twice daily.5–7

Methods

The design and primary results of the PARADIGM-HF trial have been previously described.5–7 The Ethics Committee of each of the 1043 participating institutions (in 47 countries) approved the protocol, and all patients gave written, informed consent.

Study patients

Patients had New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II–IV symptoms, an ejection fraction ≤40% (changed to ≤35% by amendment), and a plasma B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) ≥150 pg/mL [or N-terminal pro-BNP (NTproBNP) ≥600 pg/mL]. Patients who had been hospitalized for heart failure within 12 months were eligible with a lower natriuretic peptide concentration (BNP ≥100 pg/mL or NTproBNP ≥400 pg/mL). Patients were required to be taking an ACE inhibitor or ARB in a dose equivalent to enalapril 10 mg daily for at least 4 weeks before screening, along with a stable dose of a β-blocker (unless contraindicated or not tolerated) and a mineralocorticoid antagonist (if indicated). The exclusion criteria included history of intolerance of ACE inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, symptomatic hypotension (or a systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg at screening/<95 mmHg at randomization), an estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <30 mL/min/1.73 m2, a serum potassium concentration >5.2 mmol/L at screening (>5.4 mmol/L at randomization) and a history of angioedema.

Study procedures

On trial entry, existing treatment with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker was stopped, but other treatments for heart failure were continued. Patients first received enalapril 10 mg twice daily for 2 weeks (single-blind) and then LCZ696 (single-blind) for an additional 4–6 weeks, initially at 100 mg twice daily and then 200 mg twice daily. Patients tolerating both drugs at target doses were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to double-blind treatment with either enalapril 10 mg twice daily or LCZ696 200 mg twice daily. LCZ696 200 mg twice daily delivers the equivalent of valsartan 160 mg twice daily and significant and sustained neprilysin inhibition.

Study outcomes

The primary outcome was a composite of death from cardiovascular (CV) causes or a first hospitalization for heart failure. The secondary outcomes were the time to death from any cause, the change from baseline to 8 months in the clinical summary score on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) (on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating fewer symptoms and physical limitations associated with heart failure),8 the time to a new onset of atrial fibrillation, and the time to the first occurrence of a decline in renal function (which was defined as end-stage renal disease or a decrease in eGFR of ≥50% or a decrease of >30 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 from randomization to <60 mL per minute per 1.73 m2); there were too few patients with new onset atrial fibrillation and decline in renal function for meaningful analysis by age category. Safety outcomes included hypotension, elevation of serum creatinine, hyperkalaemia, cough and angioedema, as previously reported.6

Statistical analysis

The trial was designed to recruit ∼8000 patients and continue until 2410 patients experienced either a first hospitalization for heart failure or CV death (primary outcome) during which time it was expected that 1229 patients would experience CV death. However, an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Board recommended early termination of the study (∼50 months after the first patient was randomized) when the boundary for overwhelming benefit for both CV mortality and the primary outcome had been crossed.

In the present study, patients were divided into four arbitrary age categories: (i) <55 years, (ii) 55–64 years, (iii) 65–74 years, and (iv) ≥75 years. The primary composite outcome, its components and all-cause mortality were analysed for each category, as was study-drug toleration and safety. The effect of LCZ696 compared with enalapril on each outcome across the spectrum of age was examined in a Cox regression model. Age was modelled as a continuous variable. A fractional polynomial was constructed of age and entered into the model as an interaction term with treatment.9 The results of the interaction were displayed graphically using the mfpi command in STATA.10 The interaction between age and treatment on the occurrence of the pre-specified safety outcomes was tested in a logistic regression model with an interaction term between age and treatment. We also examined a sex by treatment interaction and an age by treatment by sex interaction. The proportion with a 5 point fall on the KCCQ questionnaire at 8 months was examined in a logistic regression model with an interaction term between age and treatment. The effect of region and differences in baseline characteristics was examined by adjustment of the model in sensitivity analysis as well as a region by age by treatment interaction. All analyses were conducted using STATA version 12.1 (College Station, TX, USA) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall, 8399 patients aged 18–96 years were validly randomized. The mean (median) age was 63.8 (64) years. Table 1 shows the number and proportion of patients in the different age categories analysed. There were 1563 (18.6%) patients aged ≥75 years, 587 (7.0%) aged ≥80 years, and 121 (1.44%) aged ≥85 years.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and treatment according to age category

| <55 years (n = 1624) | 55–64 years (n = 2655) | 65–74 years (n = 2557) | ≥75 years (n = 1563) | P for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46.7 ± 6.7 | 59.94 ± 2.9 | 69.3 ± 2.9 | 79.1 ± 3.5 | |

| Female, N (%) | 321 (19.8%) | 500 (18.8%) | 584 (22.8%) | 427 (27.3%) | <0.001 |

| Race, N (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| White | 703 (43.3%) | 1714 (64.6%) | 1879 (73.5%) | 1248 (79.8%) | |

| Black | 168 (10.3%) | 141 (5.3%) | 87 (3.4%) | 32 (2.0%) | |

| Asian | 544 (33.5%) | 507 (19.1%) | 339 (13.3%) | 119 (7.6%) | |

| Other | 209 (12.9%) | 293 (11.0%) | 252 (9.9%) | 164 (10.5%) | |

| Region, N (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| North America | 102 (6.3%) | 180 (6.8%) | 197 (7.7%) | 123 (7.9%) | |

| Latin America | 315 (19.4%) | 453 (17.1%) | 421 (16.5%) | 244 (15.6%) | |

| Western Europe and Other | 261 (16.1%) | 561 (21.1%) | 678 (26.5%) | 551 (35.3%) | |

| Central Europe | 411 (25.3%) | 959 (36.1%) | 928 (36.3%) | 528 (33.8%) | |

| Asia-Pacific | 535 (32.9%) | 502 (18.9%) | 333 (13.0%) | 11 (7.5%) | |

| SBP (mmHg) | 117 ± 15 | 121 ± 15 | 122 ± 15 | 125 ± 16 | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 75 ± 11 | 74 ± 10 | 73 ± 10 | 72 ± 10 | <0.001 |

| HR (bpm) | 75 ± 12 | 73 ± 12 | 71 ± 12 | 71 ± 11 | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29 ± 6.5 | 28.52 ± 5.68 | 28 ± 5 | 27 ± 4 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.03 ± 0.3 | 1.10 ± 0.28 | 1.15 ± 0.30 | 1.22 ± 0.32 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 91.4 ± 24.3 | 96.9 ± 24.8 | 101.9 ± 26.1 | 107.4 ± 28.2 | <0.001 |

| Estimated GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 80.2 ± 23.2 | 70.2 ± 18.4 | 63.4 ± 17.1 | 57.5 ± 16.0 | <0.001 |

| Median BNP (IQR) (pg/mL) | 246 [138, 530] | 252 [152, 474] | 246 [155, 444] | 266 [168, 467] | 0.023 |

| Median NTproBNP (IQR) (pg/mL) | 1410 [795, 2925] | 1491 [836, 3007] | 1646 [926, 3183] | 2000 [1133, 3958] | <0.001 |

| Ischaemic aetiology N (%) | 683 (42.1%) | 1587 (59.8%) | 1673 (65.4%) | 1093 (69.9%) | <0.001 |

| Ejection fraction (%) | 27.70 ± 6.34 | 29.29 ± 6.14 | 29.95 ± 6.18 | 30.92 ± 5.83 | <0.001 |

| NYHA Class N (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| I | 111 (6.8%) | 129 (4.9%) | 98 (3.8%) | 51 (3.3%) | |

| II | 1212 (74.8%) | 1901 (71.6%) | 1798 (70.5%) | 1008 (64.7%) | |

| III | 290 (17.9%) | 603 (22.7%) | 637 (25.0%) | 488 (31.3%) | |

| IV | 8 (0.5%) | 21 (0.8%) | 19 (0.7%) | 12 (0.8%) | |

| KCCQ CSS median (IQR) | 82 [66,94] | 81 [65,93] | 81 [64,92] | 75 [58, 88] | <0.001 |

| Medical history | |||||

| Hypertension, N (%) | 899 (55.4%) | 1884 (71.0%) | 1903 (74.4%) | 1254 (80.2%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, N (%) | 442 (27.2%) | 1008 (38.0%) | 921 (36.0%) | 536 (34.3%) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, N (%) | 347 (21.4%) | 868 (32.7%) | 1083 (42.4%) | 793 (50.7%) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization for heart failure, N (%) | 1079 (66.4%) | 1716 (64.6%) | 1561 (61.1%) | 918 (58.7%) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction, N (%) | 468 (28.8%) | 1177 (44.3%) | 1238 (48.4%) | 751 (48.1%) | <0.001 |

| Stroke, N (%) | 85 (5.2%) | 223 (8.4%) | 243 (9.5%) | 174 (11.1%) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery bypass surgery, N (%) | 137 (8.4%) | 385 (14.5%) | 473 (18.5%) | 308 (19.7%) | <0.001 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention, N (%) | 247 (15.2%) | 629 (23.7%) | 597 (23.4%) | 328 (21.0%) | 0.001 |

| Treatment | |||||

| ACE inhibitor, N (%) | 1282 (78.9%) | 2073 (78.1%) | 2002 (78.3%) | 1175 (75.2%) | 0.023 |

| ARB, N (%) | 341 (21.0%) | 588 (22.1%) | 566 (22.1%) | 397 (25.4%) | 0.003 |

| Diuretic, N (%) | 1300 (80.1%) | 2131 (80.3%) | 2031 (79.4%) | 1276 (81.6%) | 0.47 |

| Digoxin, N (%) | 627 (38.6%) | 780 (29.4%) | 718 (28.1%) | 414 (26.5%) | <0.001 |

| β-Blocker, N (%) | 1520 (93.6%) | 2493 (93.9%) | 2370 (92.7%) | 1428 (91.4%) | 0.003 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, N (%) | 1051 (64.7%) | 1570 (59.1%) | 1376 (53.8%) | 674 (43.1%) | <0.001 |

| Oral anticoagulant, N (%) | 367 (22.6%) | 832 (31.3%) | 905 (35.4%) | 581 (37.2%) | <0.001 |

| Antiplatelet agent, N (%) | 849 (52.3%) | 1540 (58.0%) | 1459 (57.1%) | 888 (56.8%) | 0.033 |

| Lipid-lowering agent, N (%) | 718 (44.2%) | 1551 (58.4%) | 1546 (60.5%) | 914 (58.5%) | <0.001 |

| Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, N (%) | 174 (10.7%) | 416 (15.7%) | 455 (17.8%) | 198 (12.7%) | 0.02 |

| Cardiac resynchronization therapy, N (%) | 68 (4.2%) | 173 (6.5%) | 219 (8.6%) | 114 (7.3%) | <0.001 |

Patient characteristics

Compared with younger patients, those that were older were more often female, white and enrolled in Western Europe and North America. Older patients also had higher systolic blood pressure, creatinine, and natriuretic peptide levels, as well as a higher average ejection fraction (Table 1 and Supplementary material online). Older patients were more likely to be in NYHA functional class III/IV than I/II and to have comorbidity. Median KCCQ score was similar (81–82) in the age groups <55, 55–64, and 65–74 years but was significantly lower (75), i.e. worse in patients ≥75 years. With respect to background treatment for heart failure, pre-trial ACE inhibitor/ARB, β-blocker and diuretic therapy was similar across age categories. Use of a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist and digoxin decreased with increasing age, whereas the opposite pattern was seen for oral anticoagulant therapy.

Dose of study drug

The mean daily dose of enalapril was 19.0 mg (SD 2.8 mg), 19.0 mg (2.7 mg), 18.9 mg (2.8 mg), and 18.5 mg (3.4 mg) in those aged <55, 55–64, 65–74, and ≥75 years , respectively (P for trend <0.001). In the same age groups, the mean dose of LCZ696 was 377 mg (61 mg), 381 mg (52 mg), 371 mg (69 mg), and 367 mg (70 mg), respectively (P for trend <0.001).

Primary composite outcome

The unadjusted incidence of the primary composite outcome of CV death or hospitalization for heart failure according to age is shown in Table 2 and Figure 1A. The incidence of this endpoint in the enalapril (control) group did not vary greatly across the age categories up to 65–74 years but was somewhat higher in those aged 75 years or above.

Table 2.

Clinical outcomes according to age category

| <55 years (n = 1624) |

55–64 years (n = 2655) |

65–74 years (n = 2557) |

≥75 years (n = 1563) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Enalapril (n = 786) | LCZ696 (n = 838) | Enalapril (n = 1382) | LCZ696 (n = 1273) | Enalapril (n = 1265) | LCZ696 (n = 1292) | Enalapril (n = 779) | LCZ696 (n = 784) |

| CV death or HF hosp. | ||||||||

| No. ratea | 204 13.4 (11.7, 15.3) |

178 10.4 (9.0, 12.0) |

352 12.5 (11.3, 13.9) |

253 9.6 (8.5, 10.8) |

329 12.7 (11.4, 14.2) |

275 10.1 (8.9, 11.3) |

232 14.8 (13.0, 16.8) |

208 12.7 (11.1, 14.6) |

| HRb | 0.78 (0.64, 0.96) | 0.76 (0.65, 0.90) | 0.80 (0.68, 0.93) | 0.86 (0.72, 1.04) | ||||

| CV death | ||||||||

| No. ratea | 127 7.7 (6.5, 9.2) |

117 6.4 (5.4, 7.7) |

199 6.4 (5.6, 7.4) |

144 5.1 (4.4, 6.0) |

210 7.5 (6.6, 8.6) |

163 5.5 (4.8, 6.5) |

157 9.2 (7.9, 10.8) |

134 7.7 (6.5, 9.1) |

| HRb | 0.84 (0.65, 1.08) | 0.79 (0.64, 0.98) | 0.74 (0.60, 0.90) | 0.84 (0.67, 1.06) | ||||

| HF Hosp. | ||||||||

| No. ratea | 112 7.3 (6.1, 8.8) |

93 5.4 (4.4, 6.6) |

223 7.9 (7.0, 9.0) |

156 5.9 (45.1, 6.9) |

188 7.3 (6.3, 8.4) |

169 6.2 (5.3, 7.2) |

135 8.6 (7.3, 10.2) |

119 7.3 (6.1, 8.7) |

| HRa | 0.75 (0.57, 0.98) | 0.74 (0.61, 0.91) | 0.86 (0.70, 1.06) | 0.85 (0.66, 1.09) | ||||

| All-cause death | ||||||||

| No. ratea | 148 9.0 (7.6, 10.5) |

131 7.2 (6.1, 8.6) |

231 7.5 (6.6, 8.5) |

183 6.5 (5.6, 7.5) |

251 9.0 (7.9, 10.2) |

215 7.3 (6.4, 8.4) |

205 12.0 (10.5, 13.8) |

182 10.5 (9.0, 12.1) |

| HRb | 0.80 (0.64, 1.02) | 0.87 (0.72, 1.06) | 0.81 (0.68, 0.97) | 0.87 (0.71, 1.07) | ||||

CV, cardiovascular; HF, heart failure; HR, hazard ratio.

aRate per 100 patient-years (95% CI). bHazard ratio (95% CI).

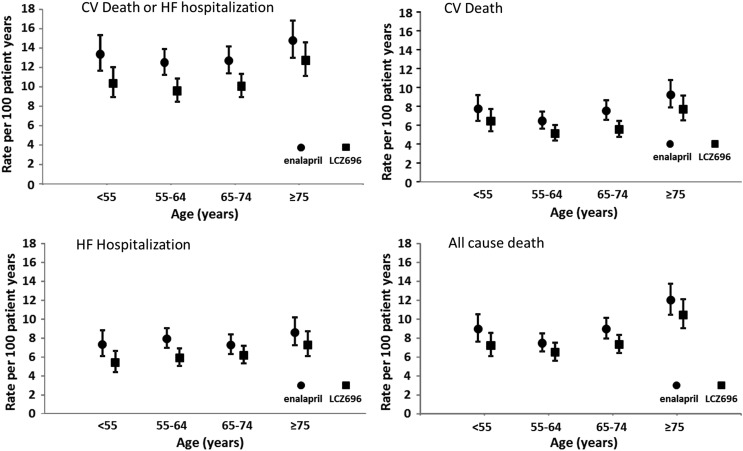

Figure 1.

Clinical outcomes of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization, cardiovascular death, heart failure hospitalization, and all-cause mortality by age category and treatment group. Rates are expressed as a rate per 100 patient-years of treatment (error bars are 95% confidence intervals).

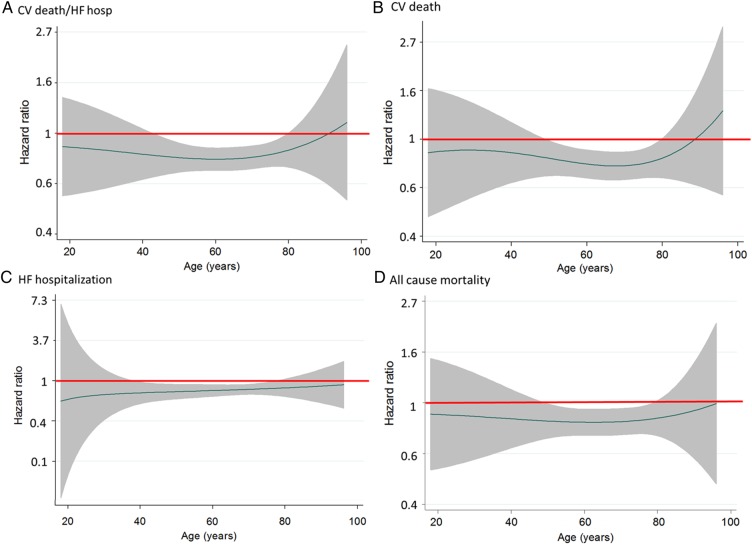

The hazard ratio (HR), i.e. the effect of LCZ696 compared with enalapril on the primary outcome, was consistent across the spectrum of age (Table 2 and Figure 2A), with a P-value for interaction of 0.94.

Figure 2.

LCZ696 to enalapril hazard ratio (line) and 95% confidence intervals (shaded area) for clinical outcomes [cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization (A), cardiovascular death (B), heart failure hospitalization (C), and all-cause mortality (D)] according to age. A hazard ratio of 1.0 is indicated by the solid horizontal line. A hazard ratio of <1.0 favours LCZ696.

Cardiovascular death

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1B, the rate of CV death in the enalapril group was relatively high in the youngest age category (<55 years). In the remainder of the patients, the rate increased stepwise with age.

The effect of LCZ696 compared with enalapril was consistent across the spectrum of age (Table 2 and Figure 2B). Although the HR was over 1 at the oldest ages, the 95% CI was wide and the P-value for interaction was not significant (P = 0.92).

Heart failure hospitalization

The rate of heart failure hospitalization in the enalapril group did not vary substantially across age categories (Table 2 and Figure 1C), except possibly in the oldest patients.

The effect of LCZ696 compared with enalapril was consistent across all age groups, including in the most elderly patients (Table 2 and Figure 2C) (P-value for interaction = 0.81).

All-cause mortality

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 1D, the rate of death from any cause was relatively high in the youngest patients (aged <55 years). In the remaining age categories, the rate of death increased with increasing age.

The effect of LCZ696 compared with enalapril was consistent across the spectrum of age (Table 2 and Figure 2D; P-value for interaction 0.99).

Effect of LCZ696 compared with enalapril with age as a continuous variable

Figure 2 shows the effect of LCZ696 compared with enalapril graphically for the four outcomes described earlier using fractional polynomial analysis. These graphs show the HR for LCZ696 vs. enalapril at each age, i.e. with age treated as a continuous variable. The polynomial allows for the possibility of a non-linear effect of treatment by age to be modelled. Consistent with the categorical analysis, risk in the LCZ696 group was lower than in the enalapril group across the age spectrum, except for CV mortality (and the composite of CV mortality or heart failure hospitalization) in the most elderly, although, as shown, the 95% confidence intervals were wide. The relationship was also generally flat indicating that the magnitude of the effect of LCZ696 on each outcome was similar across the spectrum of age. This finding was also observed even after adjusting for differences in baseline characteristics. No interaction was found between treatment and sex or between treatment, age, and sex.

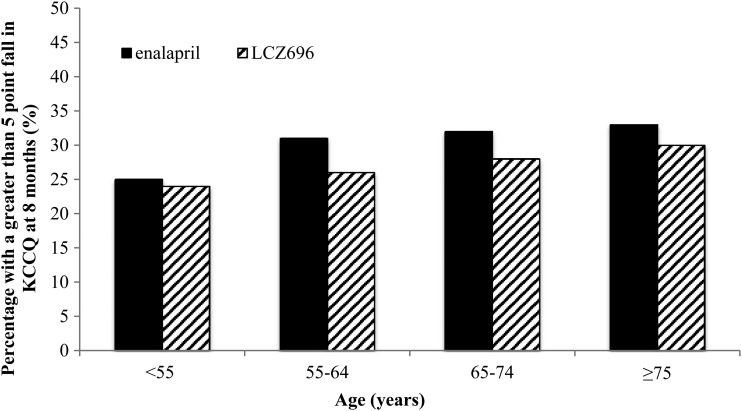

Change in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire score at 8 months

The proportion of patients with a fall in KCCQ score of five points or more (i.e. a clinically meaningful deterioration) was smaller in those treated with LCZ696 compared with patients treated with enalapril, as shown in Figure 3. This benefit of LCZ696 over enalapril in preventing worsening of KCCQ was consistent across the age groups (P-value for interaction = 0.90). The interaction was still not statistically significant after adjusting for differences in baseline characteristics (P for interaction = 0.67). We also found no interaction between age, treatment, and region on KCCQ score (P for interaction = 0.44).

Figure 3.

Proportion of patients with a five-point or greater fall (deterioration) in Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire at 8 months by age category and treatment.

Pre-specified safety assessments

Table 3 shows the occurrence of the pre-specified adverse events of interest according to age category. Generally, adverse effects became more common with increasing age, although the absolute increase in most of these was modest across the age categories. The most common pre-specified safety outcome was symptomatic hypotension which was reported in 7.6% of those aged <55 years and 11.9% of those aged ≥75 years in the enalapril group; the respective proportions in the LCZ696 groups were 11.5 and 17.7%. However, few of these patients discontinued study drug because of hypotension. There was no interaction between age and treatment on the rate of hypotension or any of the other adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation.

Table 3.

Pre-specified safety assessments

| <55 years (n = 1624) |

55–64 years (n = 2655) |

65–74 years (n = 2557) |

≥75 years (n = 1563) |

P-value+ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enalapril | LCZ696 | Enalapril | LCZ696 | Enalapril | LCZ696 | Enalapril | LCZ696 | ||

| Hypotension | |||||||||

| Symptomatic hypotension | 60 (7.6) | 96 (11.5) | 111 (8.0) | 158 (12.4) | 124 (9.8) | 195 (15.1) | 93 (11.9) | 139 (17.7) | 0.95 |

| Symptomatic hypotension with SBP <90 mmHg | 12 (1.5) | 24 (2.9) | 12 (0.9) | 33 (2.6) | 21 (1.7) | 32 (2.5) | 14 (1.8) | 23 (2.9) | 0.77 |

| Leading to discontinuation | 3 (0.4) | 5 (0.6) | 7 (0.5) | 5 (0.4) | 9 (0.7) | 12 (0.9) | 10 (1.3) | 14 (1.8) | 0.94 |

| Renal impairment, N (%) | |||||||||

| Serum creatinine ≥2.5 mg/dL | 20 (2.6) | 10 (1.2) | 48 (3.5) | 34 (2.7) | 74 (5.9) | 62 (4.8) | 46 (5.9) | 33 (4.2) | 0.49 |

| Serum creatinine ≥3.0 mg/dL | 12 (1.5) | 5 (0.6) | 27 (2.0) | 18 (1.4) | 28 (2.2) | 26 (2.0) | 16 (2.1) | 14 (1.8) | 0.28 |

| Leading to discontinuation | 9 (1.1) | 9 (1.1) | 14 (1.0) | 4 (0.3) | 20 (1.6) | 11 (0.9) | 16 (2.1) | 5 (0.6) | 0.10 |

| Hyperkalaemia, N (%) | |||||||||

| Serum potassium >5.5 mmol/L | 89 (11.4) | 97 (11.7) | 254 (18.5) | 220 (17.4) | 232 (18.4) | 218 (16.9) | 152 (19.5) | 139 (17.7) | 0.70 |

| Serum potassium >6.0 mmol/L | 23 (2.9) | 28 (3.4) | 82 (6.0) | 57 (4.5) | 75 (6.0) | 58 (4.5) | 56 (7.2) | 38 (4.8) | 0.17 |

| Leading to discontinuation | 0 (0) | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 8 (0.6) | 3 (0.2) | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.5) | 0.97 |

| Cough, N (%) | |||||||||

| Any cough | 137 (17.4) | 106 (12.6) | 198 (14.3) | 130 (10.2) | 167 (13.2) | 161 (12.5) | 99 (12.7) | 77 (9.8) | 0.58 |

| Leading to discontinuation | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 14 (1.0) | 4 (0.3) | 7 (0.6) | 3 (0.2) | 5 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 0.73 |

| Angioedema (adjudicated) | |||||||||

| No treatment/antihistamines only | 2 (0.3%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 3 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 5 (0.4%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0.20 |

| Catecholamines/corticosteroids without hospitalization | 1 (0.1%) | 2 (0.2%) | 2 (0.1%) | 3 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.58 |

| Hospitalized/no airway compromise | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.52 |

| Airway compromise | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | – |

| Any adverse event leading to study-drug discontinuation, N (%) | 16 (2.0%) | 14 (1.7%) | 35 (2.5%) | 14 (1.1%) | 43 (3.4%) | 29 (2.2%) | 35 (4.5%) | 22 (2.8%) | 0.85 |

+P-value for interaction.

Discussion

A larger number of patients with a broader range of ages were included in PARADIGM-HF than in any previous trial in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. We found that patient characteristics varied substantially by age, as in past trials.11–14 Although the rate of death and heart failure hospitalization increased with age, this gradient was not as pronounced in PARADIGM-HF as in prior trials.11–14 The benefit of LCZ696, over enalapril, was similar across the age categories examined.

Older patients, as expected, differed from their younger counterparts in many ways.11–21 As previously demonstrated, older individuals were more often women, although we did not find any interaction between treatment and sex or treatment and sex and age. Older patients had more comorbidities, higher average ejection fraction but worse NYHA functional class. They were also more likely to have an ischaemic aetiology. In addition to these differences we found older patients to have higher natriuretic peptide concentrations, presumably reflecting the higher prevalence of renal dysfunction and atrial fibrillation in these individuals (and despite their higher average ejection fraction).

The large number of countries which participated in PARADIGM-HF also meant that interactions between age, geographic region, and race/ethnicity were apparent. Non-white individuals and patients from Latin America, the Asia-Pacific region, and Central/Eastern Europe were more common in the younger age categories compared with the older ones. These findings are consistent with the global epidemiology of heart failure which shows heart failure often occurs at a younger age in countries outside Western Europe and North America where it is a condition that afflicts mainly the elderly.1

A perhaps more surprising findings of the present analyses was the relatively shallow gradient in event rates, especially heart failure hospitalization, across the age categories studied. The gradient was most marked for death from any cause and steeper than for CV mortality, i.e. our findings showed, by inference, that the greatest age-related difference was in non-CV death. Furthermore, although the crude event rates were somewhat higher in the ≥75 year age group than in younger patients, the difference did not seem to be as large as in prior trials.11–14 These two observations suggest that in well-treated patients such as those in PARADIGM-HF, effective disease-modifying drugs may have attenuated the age-related gradient in CV events that was prominent in historical studies. Despite differences in baseline characteristics and crude mortality, there was no difference in the effect of LCZ696 vs. enalapril on outcomes across the range of age after adjusting for the baseline differences.

The median KCCQ clinical summary score was only notably lower in the oldest age group (compared with the younger age categories), showing that differences in health-related quality of life, like those for hospitalization and mortality, did not become marked until the age of 75 years or older.

From a treatment perspective, the most important finding was that the benefit of LCZ696 over enalapril was consistent across the age categories studied, although in the analysis of age as a continuous variable there was some uncertainty about fatal outcomes in the most elderly patients because of the modest number of patients age 85 years or older (n = 121). However, even in very elderly patients the effect of LCZ696 on heart failure hospitalization seemed qualitatively and quantitatively similar to its effect in younger patients. This finding is consistent with many but not all12 prior analyses of treatment effect by age, although some of these have been truncated by an upper inclusion age-limit or the enrolment few elderly patients in the trials concerned.12–14,22–24

The effect of treatment on the KCCQ according to age has not been reported previously and in PARADIGM-HF, as with other outcomes, LCZ696 was superior to enalapril across the age-range examined in preventing deterioration in this measure of health-related quality of life, even in the most elderly group.

As anticipated from prior studies, treatment intolerance increased with increasing age (with the exception of angioedema), although the gradient was modest and the difference between LCZ696 and enalapril persisted across age categories. Overall, it is clear that the benefit–risk profile of LCZ696 compared with enalapril remained favourable across the broad spectrum of age studied. Despite this consistent finding with multiple drug treatments in heart failure, there is ample evidence that older patients with heart failure are often under-treated with therapies that reduce mortality and morbidity.25–30

As with any study, this one has some limitations. This is a retrospective analysis and the age-categories are arbitrary (although commonly used and clinically meaningful). We enrolled a relatively small number of the most elderly patients. The number of African-American patients was also relatively small. The safety and adverse event data must be interpreted in the light of the trial design with an enalapril and LCZ696 active run-in period.

In summary, our analyses showed that LCZ696 was more beneficial than enalapril across the broad spectrum of age studied in PARADIGM-HF and that intolerance of LCZ696 leading to treatment withdrawal was uncommon, even in elderly individuals.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Funding

PARADIGM-HF (ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT 01035255) was funded by Novartis. Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by the University of Glasgow.

Conflict of interest: P.S.J., M.F., E.B.L., C.-H.C., M.N.-K., A.R., A.S.D., J.L.R., S.D.S., K.S., M.R.Z. and M.P. have consulted for Novartis. A.R.R., M.P.L. and V.C.S. are employees of Novartis. C.-H.C. is on the speaker's bureau of Novartis. M.R.Z. and K.S. have received honoraria from Novartis for sponsored lectures. J.J.V.M.s. employer, the University of Glasgow, was/is being paid for his time spent as Executive Committee member/co-chair of PARADIGM-HF. An immediate family member of M.N.-K. received research support from Novartis, and her institution received institutional fees from Novartis.

References

- 1.Callender T, Woodward M, Roth G, Farzadfar F, Lemarie JC, Gicquel S, Atherton J, Rahimzadeh S, Ghaziani M, Shaikh M, Bennett D, Patel A, Lam CS, Sliwa K, Barretto A, Siswanto BB, Diaz A, Herpin D, Krum H, Eliasz T, Forbes A, Kiszely A, Khosla R, Petrinic T, Praveen D, Shrivastava R, Xin D, MacMahon S, McMurray J, Rahimi K. Heart failure care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maggioni AP, Dahlström U, Filippatos G, Chioncel O, Leiro MC, Drozdz J, Fruhwald F, Gullestad L, Logeart D, Metra M, Parissis J, Persson H, Ponikowski P, Rauchhaus M, Voors A, Nielsen OW, Zannad F, Tavazzi L, Heart Failure Association of ESC (HFA). EURObservational Research Programme: the heart failure pilot survey (ESC-HF pilot). Eur J Heart Fail 2010;12:1076–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krim SR, Vivo RP, Krim NR, Qian F, Cox M, Ventura H, Hernandez AF, Bhatt DL, Fonarow GC. Racial/Ethnic differences in B-type natriuretic peptide levels and their association with care and outcomes among patients hospitalized with heart failure: findings from Get with the Guidelines-Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail 2013;1:345–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAlister FA, Bakal JA, Kaul P, Quan H, Blackadar R, Johnstone D, Ezekowitz J. Changes in heart failure outcomes after a province-wide change in health service provision a natural experiment in Alberta, Canada. Circ Heart Fail 2013;6:76–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau J, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR, PARADIGM-HF Committees and Investigators. Dual angiotensin receptor and neprilysin inhibition as an alternative to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in patients with chronic systolic heart failure: rationale for and design of the Prospective comparison of ARNI with ACEI to Determine Impact on Global Mortality and morbidity in Heart Failure trial (PARADIGM-HF). Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:1062–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR, PARADIGM-HF Investigators and Committees. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014;371:993–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Packer M, McMurray JJ, Desai AS, Gong J, Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi V, Solomon SD, Swedberg K, Zile MR, Andersen K, Arango JL, Arnold M, Belohlavek J, Böhm M, Boytsov SA, Burgess LJ, Cabrera W, Calvo C, Chen CH, Dukat A, Duarte YC, Erglis A, Fu M, Gomez EA, Gonzàlez-Medina A, Hagege AA, Huang J, Katova TM, Kiatchoosakun S, Kim KS, Kozan O, Llamas EA, Martinez F, Merkely B, Mendoza I, Mosterd A, Negrusz-Kawecka M, Peuhkurinen K, Ramires F, Refsgaard J, Rosenthal A, Senni M, Sibulo AS, Cardoso JS, Squire IB, Starling RC, Teerlink JR, Vanhaecke J, Vinereanu D, Wong RC. Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibition compared with enalapril on the risk of clinical progression in surviving patients with heart failure. Circulation 2015;131:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green CP, Porter CB, Bresnahan DR, Spertus JA. Development and evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: a new health status measure for heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;35:1245–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royston P, Sauerbrei W. A new approach to modelling interactions between treatment and continuous covariates in clinical trials by using fractional polynomials. Stat Med 2004;23:2509–2525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Royston P, Sauerbrei W. Two techniques for investigating interactions between treatment and continuous covariates in clinical trials. Stata J 2009;9:230–251. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen-Solal A, McMurray JJ, Swedberg K, Pfeffer MA, Puu M, Solomon SD, Michelson EL, Yusuf S, Granger CB, CHARM Investigators. Benefits and safety of candesartan treatment in heart failure are independent of age: insights from the Candesartan in Heart failure – Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity programme. Eur Heart J 2008;29:3022–3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tavazzi L, Swedberg K, Komajda M, Böhm M, Borer JS, Lainscak M, Ford I, SHIFT Investigators. Efficacy and safety of ivabradine in chronic heart failure across the age spectrum: insights from the SHIFT study. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:1296–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrie MC, Berry C, Stewart S, McMurray JJ. Failing ageing hearts. Eur Heart J 2001;22:1978–1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rich MW, McSherry F, Williford WO, Yusuf S, Digitalis Investigation Group. Effect of age on mortality, hospitalizations and response to digoxin in patients with heart failure: the DIG study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;38:806–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmström A, Sigurjonsdottir R, Edner M, Jonsson A, Dahlström U, Fu ML. Increased comorbidities in heart failure patients ≥ 85 years but declined from >90 years: data from the Swedish Heart Failure Registry. Int J Cardiol 2013;167:2747–2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lazzarini V, Mentz RJ, Fiuzat M, Metra M, O'Connor CM. Heart failure in elderly patients: distinctive features and unresolved issues. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:717–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rich MW. Pharmacotherapy of heart failure in the elderly: adverse events. Heart Fail Rev 2012;17:589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Metra M, Dei Cas L, Massie BM. Treatment of heart failure in the elderly: never say it's too late. Eur Heart J 2009;30:391–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mogensen UM, Ersbøll M, Andersen M, Andersson C, Hassager C, Torp-Pedersen C, Gustafsson F, Køber L. Clinical characteristics and major comorbidities in heart failure patients more than 85 years of age compared with younger age groups. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:1216–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cherubini A, Oristrell J, Pla X, Ruggiero C, Ferretti R, Diestre G, Clarfield AM, Crome P, Hertogh C, Lesauskaite V, Prada GI, Szczerbinska K, Topinkova E, Sinclair-Cohen J, Edbrooke D, Mills GH. The persistent exclusion of older patients from ongoing clinical trials regarding heart failure. Arch Intern Med 2011;171:550–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komajda M, Hanon O, Hochadel M, Lopez-Sendon JL, Follath F, Ponikowski P, Harjola VP, Drexler H, Dickstein K, Tavazzi L, Nieminen M. Contemporary management of octogenarians hospitalized for heart failure in Europe: Euro Heart Failure Survey II. Eur Heart J 2009;30:478–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dulin BR, Haas SJ, Abraham WT, Krum H. Do elderly systolic heart failure patients benefit from beta blockers to the same extent as the non-elderly? Meta-analysis of >12,000 patients in large-scale clinical trials. Am J Cardiol 2005;95:896–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wikstrand J, Wedel H, Castagno D, McMurray JJ. The large-scale placebo-controlled beta-blocker studies in systolic heart failure revisited: results from CIBIS-II, COPERNICUS and SENIORS-SHF compared with stratified subsets from MERIT-HF. J Intern Med 2014;275:134–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eschalier R, McMurray JJ, Swedberg K, van Veldhuisen DJ, Krum H, Pocock SJ, Shi H, Vincent J, Rossignol P, Zannad F, Pitt B, EMPHASIS-HF Investigators. Safety and efficacy of eplerenone in patients at high risk for hyperkalemia and/or worsening renal function: analyses of the EMPHASIS-HF study subgroups (Eplerenone in Mild Patients Hospitalization and Survival Study in Heart Failure). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1585–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Massie BM, Armstrong PW, Cleland JG, Horowitz JD, Packer M, Poole-Wilson PA, Rydén L. Toleration of high doses of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with chronic heart failure: results from the ATLAS trial. The Assessment of Treatment with Lisinopril and Survival. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kostis JB, Shelton B, Gosselin G, Goulet C, Hood WB, Jr, Kohn RM, Kubo SH, Schron E, Weiss MB, Willis PW, 3rd, Young JB, Probstfield J. Adverse effects of enalapril in the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD). SOLVD Investigators. Am Heart J 1996;131:350–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Man JP, Jugdutt BI. Systolic heart failure in the elderly: optimizing medical management. Heart Fail Rev 2012;17:563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arif SA, Mergenhagen KA, Del Carpio RO, Ho C. Treatment of systolic heart failure in the elderly: an evidence-based review. Ann Pharmacother 2010;44:1604–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rich MW. Heart failure in older adults. Med Clin North Am 2006;90:863–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forman DE, Ahmed A, Fleg JL. Heart failure in very old adults. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2013;10:387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]