Abstract

Background

Participation in physical play/leisure (PPP) is an important therapy goal of children with motor impairments. Evidence for interventions promoting PPP in these children is scarce. The first step is to identify modifiable, clinically meaningful predictors of PPP for targeting by interventions.

Objective

The study objective was to identify, in children with motor impairments, body function and structure, activity, environmental, and personal factors related to PPP and modifiable by therapists.

Design

This was a mixed-methods, intervention development study. The World Health Organization framework International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health was used.

Methods

Participants were children (6–8 years old) with motor impairments, mobilizing independently with or without equipment and seen by physical therapists or occupational therapists in 6 regions in the United Kingdom, and their parents. Self-reported PPP was assessed with the Children's Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment. Modifiable-factor data were collected with therapists' observations, parent questionnaires, and child-friendly interviews. The Children's Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment, therapist, and parent data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and linear regression. Interview data were analyzed for emerging themes.

Results

Children's (n=195) PPP (X=18 times per week, interquartile range=11–25) was mainly ‘recreational’ (eg, pretend play, playing with pets) rather than ‘active physical’ (eg, riding a bike/scooter). Parents (n=152) reported positive beliefs about children's PPP but various levels of family PPP. Therapists reported 23 unique impairments (eg, muscle tone), 16 activity limitations (eg, walking), and 3 personal factors (eg, child's PPP confidence). Children interviewed (n=17) reported a strong preference for active play but indicated that adults regulated their PPP. Family PPP and impairment in the child's movement-related body structures explained 18% of the variation in PPP. Family PPP explained most of the variation.

Limitations

It is likely that the study had a degree of self-selection bias, and caution must be taken in generalizing the results to children whose parents have less positive views about PPP.

Conclusions

The results converge with wider literature about the child's social context as a PPP intervention target. In addition, the results question therapists' observations in explaining PPP.

Participation in physical play/leisure (PPP) is one of the main ways for children to engage with the world; is important for children's long-term physical, cognitive, and social development; and is central to their health and quality of life.1–3 Participation in physical play/leisure is one of the main ways to reduce the risk of long-term health and social difficulties in children with motor impairments4,5 and is an important intervention outcome for these children.

Participation in physical play/leisure outcomes in children are typically addressed by physical therapists and occupational therapists. There is currently no evidence of the effectiveness of physical therapy or occupational therapy interventions in increasing PPP in children with motor impairments.6,7 Overall, there is a general lack of evidence about effective ways to increase physical activity in children, and the development of effective interventions is recognized as a top priority for children's PPP research internationally.8

The development of effective interventions requires evidence about modifiable factors likely to be causally related to the outcome.9,10 Physical therapy and related therapy research to date has largely been underpinned by an assumption that fundamental, ‘gross motor’ movement skills are a prerequisite for physical participation.1,6,* Although there is some empirical evidence for a relationship between fundamental movement skills and PPP,11–14 recent studies have questioned the strength of this relationship.15–17 International developments in the way in which children's participation is conceptualized3 also have prompted attention to factors (environmental and personal factors) beyond the child's body structure and function and skills.

Recent studies have identified broad clusters of potentially modifiable environmental and personal factors related to PPP (eg, clusters such as family activity orientation,12 resources at home,18 and the child's activity enjoyment12). However, evidence at this broad cluster level cannot be directly used for clinical practice or to develop interventions promoting PPP because it is not at a level of detail (‘granularity’) that would enable the selection of intervention techniques. For example, ‘family activity orientation’ covers a range of factors, such as ‘family interests’ and ‘amount of family participation,’ that are likely to require different intervention techniques. Evidence about broad clusters is beneficial for narrowing the field of investigation, but choosing the most relevant intervention techniques requires further specificity around the key factors.10 Specificity at the level that is relevant to clinical practice would enable the selection of intervention techniques that are applicable to clinical practice and thus would facilitate the transfer of intervention techniques to actual practice and an improvement in children's PPP.

The aim of the present study was to identify potentially modifiable, specific factors—across body function and structure, activity, environmental, and personal factors—related to PPP in children (6–8 years old) with motor impairments. The focus was on identifying factors at a level of detail that is relevant to clinical practice.

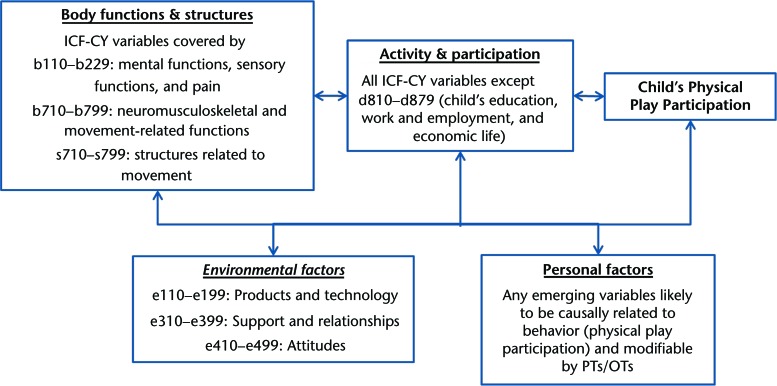

The World Health Organization framework International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY)3 is a conceptual framework commonly used for investigating participation in children. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) provides common, multidisciplinary terminology for coding and describing components related to health. It provides labels and definitions for a range of variables within the components ‘activity and participation,’ ‘body functions and structures’ (BFS), and ‘environmental factors.’3 These labels and definitions can be used to systematically code data about variables under domains such as ‘functions of the joints and bones’ and ‘muscle functions.’ Among them, the 3 components cover 54 domains, each domain further covering several variables. The ICF also includes the component ‘personal factors’ but does not identify variables within this component.

In the present study, the ICF-CY was used to provide common terminology for naming and describing factors associated with PPP. The ICF-CY was further strengthened by conceptualizing participation as ‘behavior in context’19,20—that is, as “doing stuff in life situations”—and by using constructs from evidence-based behavior change theories to code personal factors.19,20

For feasibility, only ICF variables relevant to the study aim were considered. Variables were considered relevant if they were likely to be causally related to children's PPP and modifiable within the scope of health care service–based physical therapy or occupational therapy. These criteria were used to define the initial structure of eligible factors (Fig. 1); judgments about likely causality and modifiability were made by the research team on the basis of input from the advisory team. Health condition (ie, diagnosis) was not considered to be an eligible factor because diagnosis is unlikely to be modifiable by therapists and is unlikely to explain significant additional variations in participation in children with motor impairments.21

Figure 1.

Initial structure of eligible modifiable factors, displayed in relation to each component of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY). Excluded factors were related to, for example, voice, speech, and digestive and reproductive functions; the natural environment; and systems and policies. OTs=occupational therapists, PTs=physical therapists.

Method

Design

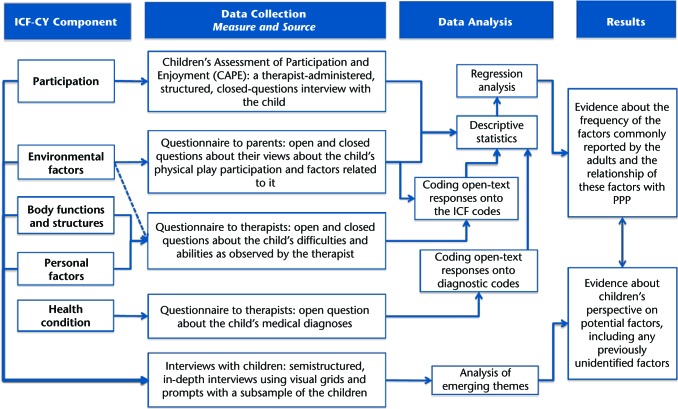

This was a mixed-methods (QUANT + qual) intervention development10 study.22 Figure 2 outlines the design. The primary outcome was children's self-reported PPP in the preceding 4 months. ‘Physical’ was defined as a pursuit of any intensity, structured or informal, that involved bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles and that required energy expenditure.23 ‘Play/leisure’ was broadly considered to be any freely chosen pursuit, outside the school curriculum, that engaged the child.

Figure 2.

Summary of the mixed-methods design used for data collection and analysis. ICF=International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health; PPP=participation in physical play/leisure.

The 2 key ethical principles for the project were that children have a right to make a contribution and a right to be safe from harm and that it is the responsibility of researchers to actively empower children to participate or to express a wish not to participate on their own terms. Written informed consent was sought from the parents, but the emphasis was on ongoing assent from the children.22

Population and Sampling

Participants were identified and recruited through 6 children's physical therapy or occupational therapy services (or both) in the National Health Service in the United Kingdom (England and Scotland). All children seen for an appointment during the data collection period (from May 2011 to July 2012) and their parents were invited to participate if the following criteria were met: the child had at least one problem in body structure or function (eg, muscle tone, body awareness), as identified by a pediatrician or a therapist; the child could mobilize independently, with or without equipment; and the child was 6 to 8 years old at the time of collection of the primary outcome data. The noncategorical approach to sampling (ie, use of functional rather than diagnostic criteria) reflected the realities of the children and clinical practice and thus supported external validity.24,25

Materials

Data about children's PPP frequency were collected with 20 PPP items (Tab. 1) from the Children's Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE).26 Only items that met the study definition of physical play/leisure were used. Standard CAPE prompt cards and response options (Tab. 1) were used; these prompt cards and response options have been previously validated in the study population. The CAPE allows specification of participation in terms of its behavioral dimensions (the ‘TACT’ principle), thereby improving measurement27: target (the child), action (participation in the 20 physical play/leisure items), context (the child's life outside the school curriculum), and time line (past 4 months).

Table 1.

CAPE Items Used in the Study, Guidance to Therapists, and Response Optionsa

CAPE=Children's Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment.

b N/A=not applicable.

c As described in the CAPE manual.26 Recr=recreational, Phys=active physical, Skill=skill-based, Soc=social.

d General guidance was also provided that a child could record only 1 response (1/20) for all activities carried out on virtual reality devices.

In addition, mapping with visual grids28 that consisted of representations of various participation contexts, free drawing, and story construction were used to conduct child-friendly, semistructured, face-to-face interviews (N. Kolehmainen, PhD, C. Missiuna, PhD, C. Owen, MSc; May 2011–July 2012; unpublished data).22

BFS.

Therapists provided a list of each child's difficulties (problem list) on the basis of their observations and standardized assessments. This process allowed the emergence of any eligible BFS variables (Fig. 1) without preset boundaries, enabled data collection at a level of specificity that corresponded to therapists' routine practice and clinical reasoning, and was feasible to use because therapists routinely assess and document children's difficulties.29

Environment.

The child interviews and therapist problem lists allowed for the reporting of environmental factors. In addition, for each participating child, a parent was invited to complete a questionnaire as a proxy for their child; the parent provided a report of physical environmental factors; provided a self-report on family support and relationships available to the child; and provided a self-report on parent goals, beliefs, and motivations related to the child's PPP (labeled ‘attitudes’ in the ICF-CY) (the full list of constructs and items is given in eAppendix A). Items for physical environment and support and relationships were generated from existing literature by identifying issues previously proposed to relate to PPP. Items for goals, beliefs, and motivation were generated by identifying issues from the literature; mapping the issues onto psychological constructs related to health behaviors; and using the standard item stems for these constructs as questionnaire items, as recommended in the literature.30,31 A pilot study of the questionnaire was done with 4 parent and clinician advisors, after which 3 items (e1152, e4500, and e165; eAppendix A) were added; these were perceived to be important by the advisors and were present in the literature but had been previously excluded because their modifiability was uncertain. Minor modifications also were made to the wording of the items.

Personal factors.

The child interviews, therapist problem lists, and open-ended parent questionnaire items all allowed the reporting of personal factors. Therapists reported the child's month and year of birth and the date of PPP data collection; these data were used to calculate the child's age.

Activity and participation other than PPP.

The child interviews, therapist problem lists, and parent responses all allowed the reporting of other activity and participation factors. Specific data about the child's mobility (“uses equipment to mobilize—yes/no”) and learning (“there are no concerns/some concerns/established delay”) were collected from the therapists.

Health condition/diagnosis.

Therapists reported the child's confirmed medical diagnoses in response to an open question.

Procedure

Therapists recruited the children; administered the CAPE and collected the problem list data; handed out parent questionnaires and collected them when complete; placed each child's data, including the parent questionnaire, in a sealed envelope; and obtained consent for passing the data to the research team. The data passed to the research team were thus anonymized, with the exception of return slips, which parents and children used to request further contact and provide their contact details. The slips were separated from the data, and no link between them remained. The lead researcher (N.K.) trained the therapists in the study procedures; supported the therapists throughout data collection; managed the overall recruitment and data flow; and conducted the child-friendly interviews, including the consent and assent procedures related to these. The interviews took place at the child's home or school and were audio recorded verbatim and later transcribed.

Data Analysis and Synthesis

The data consisted of ordinal and continuous numerical data and textual data. The approaches to analyses matched the data and the purpose for which they were collected (Fig. 2). The analyses involved 5 steps. First, child interview transcripts were analyzed with inductive thematic analysis,32–34 which allowed exploration of the issues in both depth and breadth. Two researchers (N.K. and C.M.) independently familiarized themselves with the data and identified themes and subthemes.33 In between coding cycles, researchers critically discussed and developed the themes and relationships between them. It was acknowledged that children may be susceptible to perceived expectations about the ‘right’ answer; thus, themes that emerged from direct responses to the interviewer's questions were treated with more caution than themes spontaneously raised by the children. NVivo version 10 (QSR International [Americas] Inc, Burlington, Massachusetts) was used for data management.

Second, data transformation35 was used to convert therapist and parent textual data (but not child interview transcripts) into binary data. The BFS, activity and participation, and environmental factor data were transformed by use of the recommended ICF coding procedures36 (the codes used are given in eAppendix A). The personal factor data were transformed by use of an existing list37 and related behavior change theories. Health condition data were transformed by use of diagnostic summary categories developed in consultation with a senior pediatrician (details are given in eAppendix A). The frequencies of the variables in the sample were established, and variables with 5 or fewer data points were excluded to reduce the chance of finding correlations that were not real and to avoid potential multicollinearity problems, given the number of variables being statistically tested. Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Washington) was used for data management and analysis at this step and the next step.

Third, 4 senior therapists active in research independently reviewed the list of variables from step 2 and judged whether the variables were plausibly causally related to PPP and modifiable by therapists. A variable was excluded from further analyses if at least 3 of the judges reported that the variable was unlikely to be causal or if at least 3 of the judges reported that the variable was unlikely to be modifiable.

Fourth, all numerical (including transformed) data were described by use of the median and interquartile range (continuous and ordinal data) or proportions (binary data). Two PPP scores were calculated: PPP intensity and estimated PPP activities per week. The PPP intensity score was the standard CAPE mean score and was the sum of scores for the 20 activity items divided by the total number of items.26 The PPP intensity can be used as an outcome for a regression analysis but does not lend itself easily to descriptive comparisons of patterns between people. The score for estimated PPP activities per week was an adjusted mean score devised for the present study and took into account the fact that the CAPE response options were categorical, not continuous. The estimated PPP activities per week were used in addition to the standard method to further facilitate the interpretation of the results. Figure A1 in eAppendix A provides further details about the 2 methods used to calculate each set of scores.

From the aggregate parent data, factors with a 25th quartile value of less than 5 were considered to have scope for improvement and were included in further analyses; factors with a 25th quartile value of greater than or equal to 5 were excluded. IBM SPSS Statistics version 21 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York) was used for data management and analysis at this step and the next step.

Fifth, relationships between PPP intensity and the factors from steps 3 and 4 were explored by use of univariate linear regression. Any variables that were significant at a P value of ≤.2 were included in a multiple linear regression model; this less stringent criterion value was used to minimize the rate of false-negative results. As recommended in the literature,38,39 coefficients, confidence intervals, and P values were reported for the regression results.

Three primary modes of quality assurance were used throughout. Coverage and understanding of the issues were deepened by complementing (ie, enhancing, illustrating, and clarifying) the findings from one source and mode of data collection with the findings from another and by expanding (ie, widening) the breadth and range of inquiry by drawing on one source of data to follow up and extend the findings from another.40 Alternative themes, divergent patterns, and rival explanations were actively and systematically searched through regular critiquing among members of the research team.41 The emerging results were presented at 3 different times during the analyses to a range of critical peers (n=106), including therapists, parents, medical doctors, education and social work professionals, behavioral and clinical scientists, and leisure instructors, who acted as debriefers, provided analytical probing, challenged assumptions that were taken for granted, and critiqued the plausibility of the emergent hypotheses.42

Sample Size

The sample size was determined by use of a combination of the requirements for multiple regression analysis and feasibility. Detailed sample size calculation and the related justification have been published as part of the protocol.22 On the basis of regression analysis with 29 independent variables and the larger of 104 + m or 50 + 8 × m, where m is the number of independent variables,43 the minimum sample size required was estimated to be 282 children. The feasibility estimate was 288. On the basis of these data, the target sample size for quantitative data collection was approximately 280 children. The target sample size for the interviews was 25; this value was based on feasibility and the maximum number of children likely to be required for clusters of issues (‘strong themes’) to emerge.

Role of the Funding Source

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council (ref: G0902129). Professor McKee and Professor Ramsay are funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates. The authors accept full responsibility for the article. Funders were not involved in the conduct of the study or preparation of the article.

Results

Complete CAPE and therapists' observations were returned for 44% (195/444) of the invited children, and complete parent questionnaires were returned for 78% (152/195) of these. Forty-six percent of the children (89/195) or their parents expressed willingness to be further contacted for an interview. After 17 child interviews, the 2 researchers analyzing the interview transcripts agreed that no new themes were emerging; thus, no more interviews were conducted.

As determined from the therapist data, the majority of the participating children were new referrals (60%); moved independently, without equipment (93.6%); and had a range of impairments and activity limitations (the full list is given in eAppendix B). More than one-third (37.5%) of the included children were affected by problems in learning. For most, there was no confirmed medical diagnosis (60%). For those for whom there was a diagnosis, the most common diagnostic categories were ‘cerebral palsy’ (n=17) and ‘developmental coordination disorder/hypermobility syndrome’ (n=14).

Children's PPP

The median children's PPP intensity across all participants was 2.2 (interquartile range=1.7–2.6); this value corresponds to ‘twice per month’ on the CAPE response scale. The CAPE intensity score masked the children's tendency to participate in some activities more than others; for example, it was common for a child to participate in imaginary play daily but not to participate in many of the other activities (see below and eAppendix B); averaging the daily PPP for 1 activity over the 20 activities resulted in low overall PPP intensity scores. This issue becomes clearer when the score for the estimated activities per week is considered; when this score was considered, the median children's PPP was 18 times per week (interquartile range=11–25).

Five of the 6 most common activities were ‘recreational’ (pretend play, playing with pets, going for a walk, playing games, and playing at a playground). The only ‘active physical’ activity was riding a bike/scooter (the full list is given in eAppendix B). A child's PPP was not related to the child's diagnosis, problems in learning, or use of equipment in a univariate analysis.

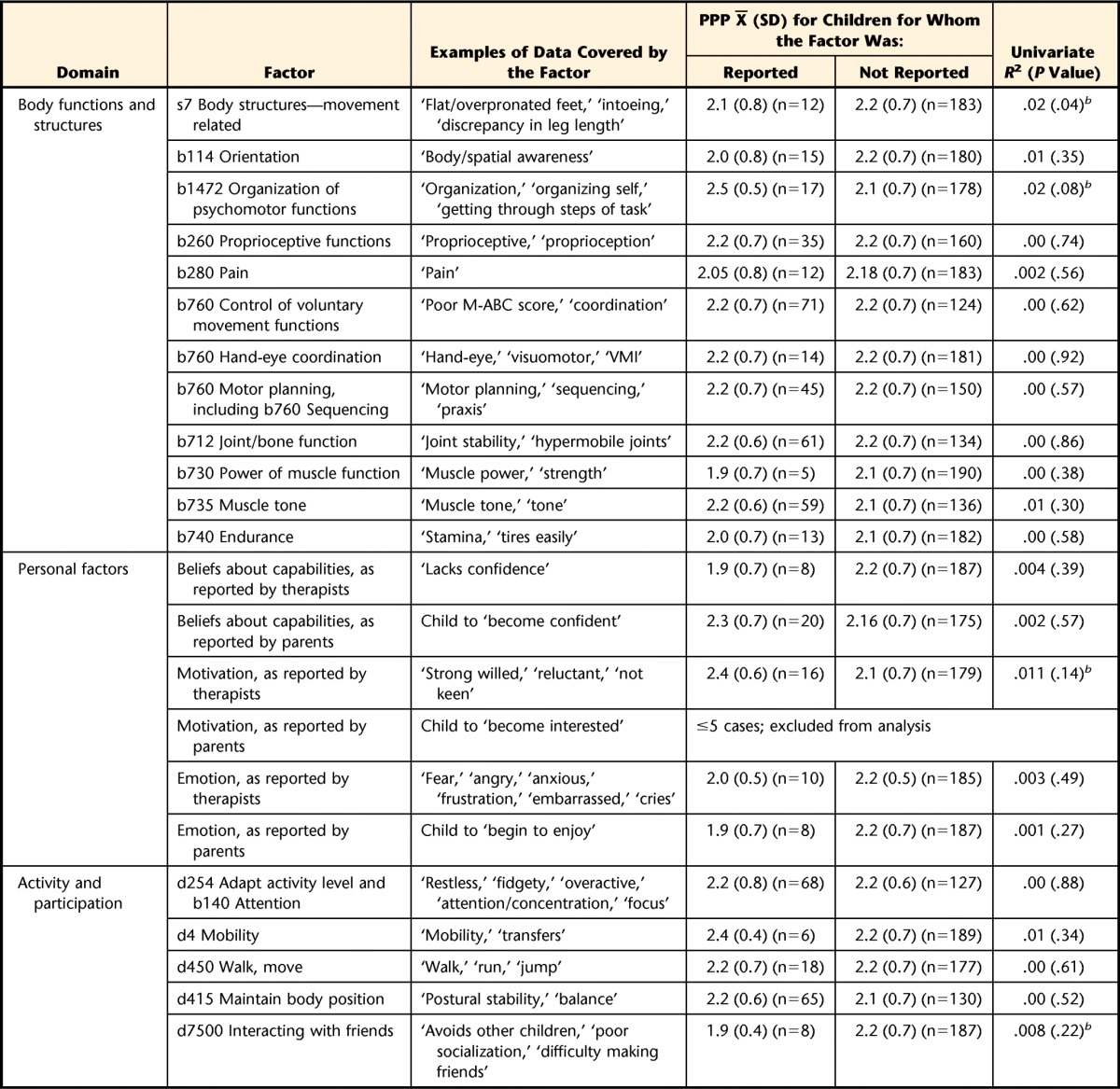

BFS Factors

Therapists reported impairments across 23 BFS factors. Four factors were excluded because they were reported for fewer than 5 children. Of the remaining factors, 14 were judged to be plausibly causally related to PPP and modifiable by therapists (eAppendix B). Two of these (‘body structures—movement related’ and ‘organization of psychomotor functions’) explained significant variations in PPP in a univariate analysis (Tab. 2).

Table 2.

Responses for ICF-CY Body Functions and Structures Domain, Personal Factor Domain, and Activity and Participation Domain Other Than PPPa

ICF-CY=International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth; PPP=participation in physical play/leisure; M-ABC=Movement Assessment Battery for Children; VMI=Test of Visual Motor Integration.

b The factor met the criteria for inclusion in multiple regression analyses (ie, significant at ≤.2, rounded half up to 2 decimal points).

Of the 76 parents who reported a PPP goal for their child (see below), 14 also reported a parallel BFS goal. Most of the BFS goals were related to the control of voluntary movements (n=6) and attention (n=3). Body function and structure factors did not emerge as a theme from the interviews with the children, including children with significant physical disabilities (Kohlemainen et al, unpublished data).

Environmental Factors

Parents reported that they viewed their child's PPP as important and had positive beliefs about the consequences of PPP for their child (with the exception of beliefs about PPP placing the child at risk of harm or injury), their child's ability to participate in physical play/leisure, and the time available for their child to participate in physical play/leisure (Tab. 3). Parents also reported high self-efficacy in choosing suitable activities for their child, verbally encouraging their child's PPP, and engaging in the activities with their child (Tab. 3). Half of the parents (76/152) spontaneously named one or more PPP goals for their child, such as “ride a bike” and “swim and play with others.” These parents also reported other environment-related goals (n=31), especially goals related to the child's relationships with peers (n=23). There was no difference in PPP intensity between the children whose parents named a PPP goal and the children whose parents did not name a PPP goal (mean PPP intensities of 2.1 [SD=0.7] and 2.2 [SD=0.7], respectively). Eleven of the parent-reported factors met the criterion for having scope for change; 5 of these explained significant variations in PPP in a univariate analysis (Tab. 3).

Table 3.

Responses for ICF-CY Environmental Domaina

ICF-CY=International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth; IQR=interquartile range; PPP=participation in physical play/leisure.

b The factor met the criterion for having scope for change (ie, 25th quartile of <5).

c The factor met the criteria for inclusion in multiple regression analyses (ie, significant at ≤.2, rounded half up to 2 decimal places).

In the child interview data, 2 of the 4 main themes were related to environment. The first theme, ‘places, activities, and people,’ described the context of children's participation and included descriptions of family homes, grandparents' houses, and parks and beaches; playing and riding a bike; and parents, siblings, other adults, and friends. Within this theme, children consistently described 2 specific factors as directly influencing PPP: people with authority and these people's judgments about the weather. For example, child 10 stated the following:

My dad or my mum definitely [decide what we do]. They decide, let's say if it's half rainy, they, we go to the tree house place just for a few minutes and then we go for a walk but if it's not raining we can go to the playground or stay in the tree place for a long time.

The second theme, ‘rules, norms, and routines,’ consisted of descriptions of a range of rules, norms, and routines that the children perceived as structuring PPP; this theme was a strong theme across all 17 transcripts. Characteristic of the children's expression of the rules, norms, and routines were sequences or interlinked “if, then” statements, such as “if it is Saturday, then we go to the park,” that formed complex regulative structures. For example, child 4 stated the following:

[At school, if it's] lunchtime you are allowed [to go to the fields] but the problem is if it's raining then you're not allowed to go on field, you go on bottom playground instead, but when you're on the field then you're not allowed on the bottom playground.

Across all therapists, environmental barriers were reported for fewer than 5 children. The small number of data points precluded further analyses of these data.

Personal Factors

Therapists reported that the children experienced problems in 3 personal factors: confidence, emotion, and motivation (Tab. 2). Of the 76 parents who reported PPP goals for their child, 28 also reported parallel goals related to the child's personal factors: confidence (n=18), emotion (n=7), and motivation (n=3). All 3 factors were judged to be plausibly causally related to PPP and modifiable by therapists (eAppendix B). Motivation, as reported by therapists, was related to PPP in the univariate analysis (Tab. 2).

In the child interview data, 2 of the 4 main themes were related to personal factors. The first theme, ‘play, imagination, and fantasy,’ consisted of the children describing play and playfulness as a way to make activities interesting, fun, and intriguing; to follow their interests rather than comply with the existing rules and norms; and to challenge boundaries, either physically or imaginatively. For example, child 5 stated the following (narrating a story he was imagining):

I said, “Dad, can we go to the beach?” “No, son, it's not, no we are never going to the beach again.” [The son] knows the plan for him to do it; he knows a plan for him to get to the beach [even when it is not allowed]. And then he says “Oh look a bike.” [The story continues with an elaborate imagined escape on the bike and a chase by the Dad with police involvement.]

The last of the 4 themes, ‘scary and too hard,’ consisted of children describing how challenging the norms and doing things outside the usual rules also could be perceived as risky and could be scary. For example, child 1 stated the following:

I was allowed to go up in [a cherry picker] and touch the roof…. I was quite scared.

Other Activity and Participation Factors

Therapists reported activity limitations across 12 other activity and participation factors. Four were judged likely to be causally related to PPP and modifiable by therapists (eAppendix B); 1 (interacting with friends) was related to PPP in a univariate analysis (Tab. 2).

Responses on parent questionnaires also included other activities (primarily related to self-care), and child interviews included descriptions of, for example, work and being at school. The responses did not convey a sense of these competing with or directly relating to PPP; these data were not included in further analyses.

PPP and BFS Factors, Environmental Factors, and Personal Factors

The intensity of PPP and the 9 factors identified in univariate analyses were entered into a regression model. Seven variables—child's organization of psychomotor functions, child having friends for PPP, child's ability to interact with friends, parent's PPP behavior, parent's belief about PPP placing the child at risk of harm, parent's self-efficacy about overcoming barriers to PPP, and child's motivation for PPP—no longer explained a significant amount of variation and were removed from the model. The 2 remaining variables—body structures (movement related) and all family members' PPP behavior—explained 16% (adjusted R2) of the variation in PPP intensity (Tab. 4). For PPP intensity as the outcome, the presence of a problem in the child's body structures (movement related) was associated with an increase of 0.51 (95% confidence interval=0.11, 0.91; P=.013), and increased parental agreement that all family members participated in physical play/leisure was associated with an increase of 0.14 (95% confidence interval=0.05, 0.23; P=.002).

Table 4.

Variation Explained in PPP Intensity by ICF-CY BFS, Env, PF, and Other APa

PPP=participation in physical play/leisure; ICF-CY=International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth; BFS=body functions and structures factor; Env=environmental factor; PF=personal factor; Other AP=other activity and participation factor.

b Significant at a P value of less than .05, rounded to 3 decimal places.

Further exploration of the data, with estimated activities per week instead of PPP intensity as the outcome, replicated the result of all family members' PPP behavior explaining a significant amount of variation but did not replicate body structures (movement related) being a significant factor and did not result in any of the other factors being significant. In this model, parental agreement that all family members participated in physical play/leisure was positively associated with estimated activities per week in child PPP (1.83; 95% confidence interval=0.53, 3.14; P=.006). The variable body structures (movement related) was not associated with the outcome.

Discussion

In the present study, an integrated therapeutic-behavioral framework was used to investigate PPP in 6- to 8-year-old children with motor impairments for the purpose of generating evidence to guide the development of an intervention to increase PPP. The study consistently showed that parent-reported family members' PPP behavior was the strongest factor explaining variations in children's PPP. Therapists reported family PPP or other environmental factors for fewer than 5 children, indicating that they rarely focused on these factors; instead, they focused on the child's impairments and basic motor activities. Parents reported generally positive beliefs in relation to their child's PPP. Children indicated that social environmental factors, particularly the rules and ways of doing things as established by adults, were a key factor in PPP. In addition to this consistent finding, the study also showed a statistical relationship between the presence of problems in body structures and increased participation. This finding was likely to be a function of the study sample. The children with body structure problems were reported to have specific musculoskeletal impairments (eg, flat feet or a discrepancy in leg length) and may not have had other, more general motor impairments. It is plausible that children with specific musculoskeletal impairments experience fewer participation restrictions than children with more global motor impairments, resulting in a positive relationship between musculoskeletal impairments and fewer participation restrictions in the present study.

The present study involved sampling across multiple sites and settings and the use of data sources and collection methods that closely resembled clinical therapy practice in the United Kingdom. This approach provided strong external validity and applicability of the results. However, this approach also made it impossible to standardize therapist responses for the purpose of assessing internal validity and reliability. The primary outcome was assessed with an established measure validated for the study population, and the measures for collecting parent data were designed on the basis of established methods from behavioral science. The child interviews were built on methods from other, similar studies, and established methods of quality assurance were applied to the analysis of the collected data. Whole-population sampling was used, and recruitment was closely monitored to identify and address any issues. However, it is likely that the study had a degree of self-selection bias, and caution must be taken in generalizing the results to other populations, including children whose parents have less positive views about PPP. The number of children recruited was below the target sample size; however, the number of variables entered in the regression analysis was also smaller than allowed for in the sample size estimation.

In contrast to previous studies,44,45 the present study did not reveal relationships among the child's general mobility, cognitive level, and participation. This result may be explained by differences in the sample; studies that have revealed such relationships typically have focused primarily on children with cerebral palsy and thus potentially have included children with more significant cognitive impairments and mobility limitations. The types of activities also may partially explain the difference; in the present study, the use of a broad definition of physical play meant less emphasis on formal, skills-based activities known to be more difficult for children with motor impairments.

Parents' positive beliefs about PPP did not relate to children's PPP behavior; this finding closely mirrors the results in mainstream physical activity literature. Studies consistently have shown a weak relationship between positive beliefs about and motivation to engage in physical activity and actual physical activity behavior.46 These data suggest that in the design of interventions for increasing PPP, postmotivational factors targeted at behavioral regulation (eg, presence of well-specified PPP goals, plans for achieving these goals, support for coping with unexpected barriers, and establishment of supportive PPP routines) are likely to be more important than techniques targeted at changing beliefs or increasing motivation.47,48

To our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate whether a child's problems identified and reported by therapists in their daily routine practice relate to participation outcomes for the child. The results indicate that there may be poor correspondence between therapist-identified problems and children's PPP. These results require replication in other studies, possibly with a more standardized checklist. The data about therapists' observations in the present study could be used as the initial list of items for developing such a checklist.

The results of the present study provide evidence from multiple perspectives about the key factors that therapists, families, and scientists should consider when aiming to increase PPP in children with motor impairments. The results support the views that children's participation is related to the activity orientation of the family (as opposed to only the parent or the child) and that family is the key unit of analysis. The results indicate that therapists should broaden the scope of factors considered at assessment, especially to include family PPP behavior. Findings from the children themselves further suggest that family PPP behavior affecting children may be guided by established rules and ways of doing things and that the rules may be identified by listening to family members' descriptions of their activities (eg, “if, then” statements such as “if it is Saturday, then we usually go to the park”). Identification of the rules and routines would provide an avenue for intervention by enabling the family and the therapist to integrate PPP behaviors into existing routines, to facilitate changes to routines that inhibit PPP, or both. The results concur with wider physical activity literature indicating that interventions to increase PPP need to encompass postmotivational factors and actual PPP behavior; it is not sufficient to focus on beliefs (eg, whether PPP is viewed as valuable) and motivation.46–48

To our knowledge, this is the first study in which behavioral and therapeutic approaches have been applied, together and systematically, to the study of participation in children with disabilities. Further work is needed to understand family PPP behavior and its relationship to child PPP; continuing to combine these 2 approaches is likely to be advantageous for such investigations. Designing an intervention to increase PPP is likely to benefit from evidence and theory about behavioral approaches, including behavior change interventions for physical activity. Our next step will be to investigate the transferability of evidence-based techniques from behavior change interventions for physical activity to use in therapy interventions for children with motor impairments.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Dr Kolehmainen proposed the research idea and refined it further with all coauthors. Dr Kolehmainen, Professor Ramsay, Professor McKee, Professor Missiuna, and Professor Francis developed the research design. Dr Kolehmainen led the writing of the manuscript; all other coauthors provided critical comments throughout the manuscript. Dr Kolehmainen collected and analyzed all data; the coauthors provided expertise on the methods (Professor Ramsay, Professor McKee, and Professor Francis) and the topic content (Professor Missiuna, Ms Owen, and Professor Francis). Professor Missiuna also analyzed the child interviews. Dr Kolehmainen led fund procurement, project management, and institutional liaisons. All authors provided consultation (including review of manuscript before submission).

The authors thank the therapists for supporting data collection; the child and parent advisors for contributing to the data collection materials and interpretation of the results; Ms Heather Angilley (Mid-Yorkshire NHS), Ms Jennifer McAnuff (Leeds NHS), and Dr Olaf Verschuren (de Hoogstraat Revalidatie) for clinical expertise; Dr Marjolijn Ketelaar (de Hoogstraat Revalidatie) and Professors Peter Rosenbaum (McMaster University), Allan Colver (Newcastle University), and Marie Johnston (University of Aberdeen) for scientific advice; and Dr Nora Fayed (McMaster University) and Dr Olaf Kraus de Camargo (McMaster University) for advice on the use of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth.

The study was approved by a National Health Service Research Ethics Committee (ref: 11/S0801/2).

The study was funded by the UK Medical Research Council (ref: G0902129). Professor McKee and Professor Ramsay are funded by the Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health Directorates.

In this report, double quotation marks are used to indicate a direct quotation from the study data, and single quotation marks are used to indicate a technical usage of a term or a set of words. For example, “to ride a bike” is a wording from the data, whereas ‘rule, norms, and routines’ is a wording used as a technical concept (label) for a meta-theme.

References

- 1. Zwicker J, Harris S, Klassen A. Quality of life domains affected in children with developmental coordination disorder: a systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2013;39:562–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Powrie B, Kolehmainen N, Turpin M, et al. The meaning of leisure for children and young people with physical disabilities: a systematic evidence synthesis of qualitative studies. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2015. May 4 [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.12788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health—Children and Youth Version (ICF-CY). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Poulsen A, Ziviani JM, Johnson H, Cuskelly M. Loneliness and life satisfaction of boys with developmental coordination disorder: the impact of leisure participation and perceived freedom in leisure. Hum Mov Sci. 2008;27:325–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cantell M, Crawford S, Doyle-Parker P. Physical fitness and health indices in children, adolescents and adults with high or low motor competence. Hum Mov Sci. 2008;27:344–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Novak I, McIntyre S, Morgan C, et al. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: state of the evidence. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55:885–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Martin L, Baker R, Harvey A. A systematic review of common physiotherapy interventions in school-aged children with cerebral palsy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2010;30:294–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gillis L, Tomkinson G, Olds T, et al. Research priorities for child and adolescent physical activity and sedentary behaviours: an international perspective using a twin-panel Delphi procedure. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2013;10:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. A Framework for Development and Evaluation of RCTs for Complex Interventions to Improve Health. London, United Kingdom: Medical Research Council; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Craig P, Dieppe P, MacInture S, et al. Developing and Evaluating Complex Interventions: New Guidance. London, United Kingdom: Medical Research Council; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Green D, Lingam R, Mattocks C, et al. The risk of reduced physical activity in children with probable developmental coordination disorder: a prospective longitudinal study. Res Dev Disabil. 2010;32:1332–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Palisano R, Orlin M, Chiarello L, et al. Determinants of intensity of participation in leisure and recreational activities by youth with cerebral palsy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:1468–1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Wely L, Becher J, Balemans A, Dallmeijer A. Ambulatory activity of children with cerebral palsy: which characteristics are important? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54:436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Longo E, Badia M, Orgaz B. Patterns and predictors of participation in leisure activities outside of school in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34:266–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bjornson KF, Zhou C, Stevenson R, Christakis DA. Capacity to participation in cerebral palsy: evidence of an indirect path via performance. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:2365–2372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fisher A, Reilly JJ, Kelly LA, et al. Fundamental movement skills and habitual physical activity in young children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37:684–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ziviani J, Poulsen A, Hansen C. Movement skills proficiency and physical activity: a case for Engaging and Coaching for Health (EACH)—Child. Aust Occup Ther J. 2009;56:259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Colver A, Thyen U, Arnaud C, et al. Association between participation in life situations of children with cerebral palsy and their physical, social, and attitudinal environment: a cross-sectional multicenter European study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:2154–2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fisher K, Johnston M. Experimental manipulation of perceived control and its effects on disability. Psychol Health. 1996;11:657–669. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnston M, Bonetti D, Joice S, et al. Recovery from disability after stroke as a target for a behavioural intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:1117–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Law M, Finkelman S, Hurley P, et al. Participation of children with physical disabilities: relationships with diagnosis, physical function and demographic variables. Scand J Rehabil. 2004;11:156–162. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kolehmainen N, Francis JJ, Ramsay CR, et al. Participation in physical play and leisure: developing a theory- and evidence-based intervention for children with motor impairments. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. World Health Organization. Physical activity. Updated February 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/topics/physical_activity/en/ Accessed May 21, 2015.

- 24. Perrin EC, Newacheck P, Pless IB, et al. Issues involved in the definition and classification of chronic health conditions. Pediatrics. 1993;91:787–793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stein R, Jessop D. A noncategorical approach to chronic childhood illness. Public Health Rep. 1982;97:354–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. King G, Law M, King S, et al. The Children's Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment (CAPE) and the Preferences for Activities of Children (PAC). San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fishbein M. Attitude and the prediction of behaviour. In: Fishbein M, ed. Readings in Attitude Theory and Measurement. New York, NY: Wiley; 1967:477–492. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Thomas N, O'Kane C. The ethics of participatory research with children. Children & Society. 1998;12:336–348. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kolehmainen N, MacLennan G, Francis JJ, Duncan EA. Clinicians' caseload management behaviours as explanatory factors in patients' length of time on caseloads: a predictive multilevel study in paediatric community occupational therapy. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Godin G, Kok G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. Am J Health Promot. 1996;11:87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Francis JJ, Eccles MP, Johnston M, et al. Constructing Questionnaires Based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour: A Manual for Health Services Researchers. Newcastle Upon Tyne, United Kingdom: Centre for Health Services Research; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Miles MB, Huberman AA. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gibbs GR. Analyzing Qualitative Data. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Method Approaches. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cieza A, Brockow T, Ewert T, et al. Linking health-status measurements to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. J Rehabil Med. 2002;34:205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Geyh S, Peter C, Müller R, et al. The personal factors of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health in the literature: a systematic review and content analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2011;33:1089–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hoenig JM, Heisey DM. The abuse of power: the pervasive fallacy of power calculations for data analysis. Am Stat. 2001;55:19–24. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Colegrave N, Ruxton G. Confidence intervals are a more useful complement to nonsignificant tests than are power calculations. Behav Ecol. 2003;14:446–450. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Greene JC, Caracelli VJ, Graham WF. Toward a conceptual framework for mixed-method evaluation designs. Educ Eval Policy Anal. 1989;11:255–274. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lincoln YS, Guba EA. Naturalistic Inquiry. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. 4th ed Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Majnemer A, Shevell M, Law M, et al. Participation and enjoyment of leisure activities in school-aged children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2008;50:751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shikako-Thomas K, Majnemer A, Law M, Lach L. Determinants of participation in leisure activities in children and youth with cerebral palsy: systematic review. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2008;28:155–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rhodes RE, Dickau L. Experimental evidence for the intention-behavior relationship in the physical activity domain: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2012;31:724–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sniehotta F. Towards a theory of intentional behaviour change: plans, planning and self-regulation. Br J Health Psychol. 2009;14:261–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Greaves CJ, Sheppard KE, Abraham C, et al. Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.