Abstract

Background

Exercise is recommended for people with an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (AECOPD), yet there is little information to guide safe and effective mobilization and exercise for these patients.

Objectives

The purpose of this study was to develop a clinical decision-making tool to guide health care professionals in the assessment, prescription, monitoring, and progression of mobilization and therapeutic exercise for patients with AECOPD.

Design and Methods

A 3-round interdisciplinary Delphi panel identified and selected items based on a preselected consensus of 80%. These items were summarized in a paper-based tool titled Mobilization in Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (AECOPD-Mob). Focus groups and questionnaires were subsequently used to conduct a sensibility evaluation of the tool.

Results

Nine researchers, 13 clinicians, and 7 individuals with COPD identified and approved 110 parameters for safe and effective exercise in AECOPD. These parameters were grouped into 5 categories: (1) “What to Assess Prior to Mobilization,” (2) “When to Consider Not Mobilizing or to Discontinue Mobilization,” (3) “What to Monitor During Mobilization for Patient Safety,” (4) “How to Progress Mobilization to Enhance Effectiveness,” and (5) “What to Confirm Prior to Discharge.” The tool was evaluated in 4 focus groups of 18 health care professionals, 90% of whom reported the tool was easy to use, was concise, and would guide a health care professional who is new to the acute care setting and working with patients with AECOPD.

Limitations

The tool was developed based on published evidence and expert opinion, so the applicability of the items to patients in all settings cannot be guaranteed. The Delphi panel consisted of health care professionals from Canada, so items may not be generalizable to other jurisdictions.

Conclusions

The AECOPD-Mob provides practical and concise information on safe and effective exercise for the AECOPD population for use by the new graduate or novice acute care practitioner.

The majority of individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) experience at least one acute exacerbation of COPD (AECOPD) per year; many have multiple exacerbations.1 Many of these exacerbations require hospitalization, often with long lengths of stay.2 A common feature of AECOPD and subsequent hospitalization is profoundly reduced physical activity levels, which increases the risk of readmission and mortality.3 Pitta et al4 assessed physical activity in hospitalized patients with AECOPD and estimated that the majority of waking time was spent sitting or lying down, whereas less than 15 minutes per day was spent walking. Total time spent walking was less than 20 minutes per day 1 month post-AECOPD. Deterioration in physical function is a well-recognized sequela of hospitalization,5 and inactivity associated with bed rest can significantly affect muscle function and morphology. After 5 days of hospitalization for an AECOPD, quadriceps muscle peak torque decreases by 5% of the predicted value.6 Moreover, a 10-day period of inactivity can reduce quadriceps femoris muscle mass by 13%.7

Exercise and pulmonary rehabilitation during or shortly after an AECOPD have been shown to improve functional exercise capacity and quality of life and reduce the risk of readmission.8 Despite these benefits and strong recommendations for use in the acute care setting,9 structured inpatient exercise or activity programs with exercise-related outcome measures are not routinely implemented in acute care.10 One reason may be the lack of information on the optimal elements of the intervention. Nurses, physical therapists, and other health care professionals are tasked with the objective to improve a patient's mobility in preparation for discharge, yet there is little information to guide the health care professional on the key parameters to ensure exercise that is effective at increasing physical outcome measures while being safe to undertake for the patient and staff. Referrals for physical therapy consults regarding exercise for the hospitalized patient with AECOPD may state “activity as tolerated,” which could result in an overly conservative approach to exercise prescription for these patients.

In response to a request for further information from physical therapy clinicians and the Physiotherapy Association of British Columbia to guide their practice with patients with AECOPD, the purpose of this study was to develop an evidence-informed clinical decision-making tool that provides the necessary information to guide health care professionals in the assessment, prescription, monitoring, and progression of exercise and activity for hospitalized patients with AECOPD.

Method

Study Team

The study team consisted of 5 physical therapists (including practicing therapists and a physical therapy knowledge broker), 1 nurse, and 1 physician from universities and health authorities in the provinces of British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Ontario. A knowledge broker is an intermediary who bridges the gap between research evidence and clinical practice. Acting as a catalyst and “boundary spanner,” the knowledge broker links researchers, clinicians, and decision makers to facilitate the creation or synthesis, translation, dissemination, implementation, and adoption of evidence to inform practice.11 In British Columbia, funding from the University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine, the provincial physical therapy professional association, and 2 teaching hospital research institutes supports a physical therapy knowledge broker position (held by Ms Hoens) to facilitate the knowledge translation of many physical therapy–related projects. This facilitation includes participating in research projects, continuing professional development, development of clinical decision-making support tools, and other activities to enhance evidence-informed clinical practice of physical therapists in the province.

The team also was supported by representatives from the Physiotherapy Association of British Columbia and the COPD Canada Patient Network. Two master of physical therapy student research groups participated in data collection and analysis for both the Delphi panel and the focus groups.

Study Design

We utilized an integrated knowledge translation approach to develop the clinical decision-making tool. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research defines integrated knowledge translation as research where “potential knowledge users are engaged throughout the research process. This approach should produce research findings that are more likely to be directly relevant to and used by knowledge users.”12(p1) For this study, the integrated knowledge translation approach involved: (1) having clinicians, researchers, and patients as part of the study team; (2) developing the tool by conducting a systematic review of the literature (published in 201213) and convening a Delphi panel composed of expert clinicians, researchers, and patients with COPD; and (3) receiving feedback on the tool from a multidisciplinary group of clinicians.

Identification of Participants for Delphi Panel

The Delphi method is a technique that obtains information from a group in a structured manner while providing anonymity for the individual responses.14 This method uses questionnaires to gain specific information about a topic. Further rounds of questionnaires confirm the answers given, request additional responses, and determine the ranking or obtain consensus about the accuracy or use of the given responses. The communication is anonymous, which reduces the likelihood of confrontation or swaying of group opinion by a persuasive individual. This approach results in controlled feedback to create results that are less influenced by personal biases and confrontation, as responses are collective and anonymous.15

Three categories of stakeholders (clinicians, academicians, and patients) were recruited to create an interdisciplinary Delphi panel that could provide robust and varied perspectives. Clinicians were frontline health care providers, including physical therapists, physicians, registered nurses, and respiratory therapists. Clinicians were required to have 3 years of experience working with patients with AECOPD and to be currently involved in the care of these patients. Physical therapy and respiratory therapy practice leaders, nursing patient care coordinators, unit managers, and physician team leaders from urban and community hospital settings were contacted to refer colleagues to participate in the study. Academicians were identified on university websites and were recruited if they were a physical therapist, respiratory therapist, physician, or nursing faculty member currently teaching or conducting research on COPD or respiratory disease at a Canadian university. Patients were recruited via Canadian groups for patients with COPD, including the COPD Canada Patient Network, and had a self-reported diagnosis of COPD with an acute exacerbation within the previous 2 years. All study participants were proficient in English and had access to a computer with Internet and email.

The Delphi panel targeted sample size was 20 participants, based on previous studies of this type.16 Therefore, we aimed to recruit 25 participants, anticipating a 25% dropout rate between round 1 and round 3. Participants were recruited from western, eastern, and Atlantic provinces in Canada and from metropolitan, urban, and rural settings. Each participant provided written informed consent.

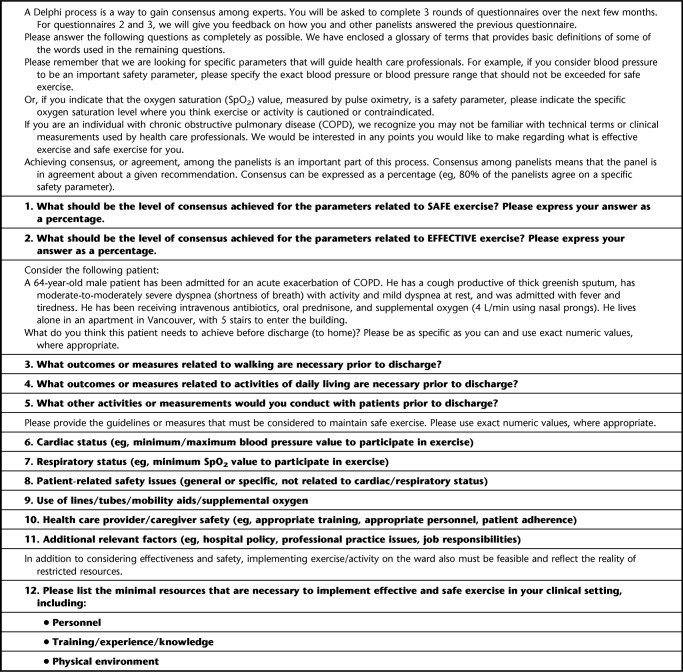

Round 1: parameter identification.

For round 1, questionnaires were distributed via a Web survey (Verint-Enterprise Feedback Management Canada, Quebec, Canada) to all panelists. The round 1 questionnaire is presented in Appendix 1. The questionnaires included a clinical case scenario representing a typical patient hospitalized with AECOPD. Operational definitions for terms used in the questionnaire also were provided. The questionnaire was reviewed by 3 physical therapists, who provided feedback on clarity and relevance of questions. In round 1, panelists were asked to consider the case scenario if necessary and then list the parameters and thresholds for safe and effective exercise in hospitalized patients with an AECOPD. Panelists were requested to complete the questionnaire within a 3-week period, with an email reminder sent 1 week prior to the deadline. We also asked panelists for the level of consensus required among panelists for an item to be included in the tool.

Round 1 responses were summarized in a frequency table to identify duplicate answers. Responses also were revised to normalize terminology. This process was completed independently by 3 research assistants. Two other research assistants reviewed the 3 tables and independently consolidated and classified the items to create lists of potential responses and terms that defined safe or effective exercise parameters for AECOPD. Finally, another research assistant combined the 2 lists to produce a final list to be sent to experts for round 2 of the Delphi process.

Round 2: agreement of items and classifications.

Panelists were given the list of consolidated responses and were asked if the list adequately included and characterized their responses from round 1. Experts were able to add or change responses and were requested to complete round 2 within 2 weeks.

Round 3: rating of statements.

The full list of items from round 2 was reviewed again to eliminate duplicates, and items were placed into 5 main care categories: (1) “What to Assess Prior to Mobilization,” (2) “When to Consider Not Mobilizing or to Discontinue Mobilization,” (3) “What to Monitor During Mobilization for Patient Safety,” (4) “What to Monitor and How to Progress Mobilization to Enhance Effectiveness,” and (5) “What to Confirm Prior to Discharge.” Any item could be categorized into more than one category. We then asked each panelist to decide if each item was high priority (yes/no) and whether it was feasible in a typical acute care hospital setting (yes/no). Panelists also could suggest a different categorization or make comments regarding any of the items.

Development of the Tool and Focus Group Evaluation

Using the items developed from the Delphi panel together with the knowledge of exercise in AECOPD from our systematic review,13 we created the Mobilization in Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (AECOPD-Mob) clinical decision-making tool. We utilized the format of another successful tool (Safe Prescription of Mobilizing Patients in Acute Care Settings [SAFEMOB], available at http://www.physio-pedia.com/SAFEMOB) developed by the Physiotherapy Association of British Columbia and members of our research team. The tool is organized into 5 main sections, which correspond to the 5 categories of care identified from the Delphi panel. These sections have different colors, with the details provided as bullet points. Some sections provide general points, such as “– (assess need for) mechanical lifts, poles, transfer belts…” in the section “What to Assess Prior to Mobilization,” whereas other sections provide specific parameters, such as “heart rate less than 40” in the section “When to Consider Not Mobilizing or to Discontinue Mobilization.” The AECOPD-Mob also has an appendix that describes in further detail specific exercises that can be prescribed to patients based on the assessment and rating of their current level of mobility. The tool is organized to enable a clinician to access the key information to prescribe safe and effective therapeutic exercise, specific to the current status of the patient.

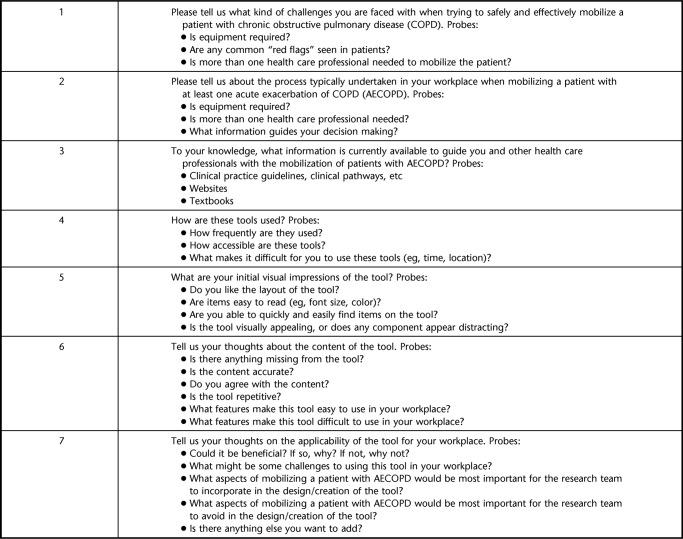

We then conducted interdisciplinary focus groups of health care professionals from 4 acute care hospitals in metropolitan Vancouver, British Columbia. To be considered for the focus groups, clinicians had to have 3 years of experience caring for individuals with COPD and had to be actively providing AECOPD care in an acute care hospital. Each focus group participant received in advance a copy of the systematic review and the draft clinical decision-making tool and attended a 60- to 90-minute facilitated focus group session that used a series of questions (Appendix 2) to guide the discussion. Participants also completed a demographic and tool sensibility questionnaire as per the methodology from Rowe and Oxman,17 which asked 12 questions on the layout, comprehensiveness, ease of use, and desirability of the tool. Respondents indicated their answer on a 7-point Likert scale (1=disagree, 4=neutral, and 7=agree on the scale). Focus group discussions were transcribed verbatim, and key themes regarding strengths and weaknesses of the tool and suggested revisions were summarized.

Role of the Funding Source

A grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR No: 226908) funded the study.

Results

Delphi Panel Participants

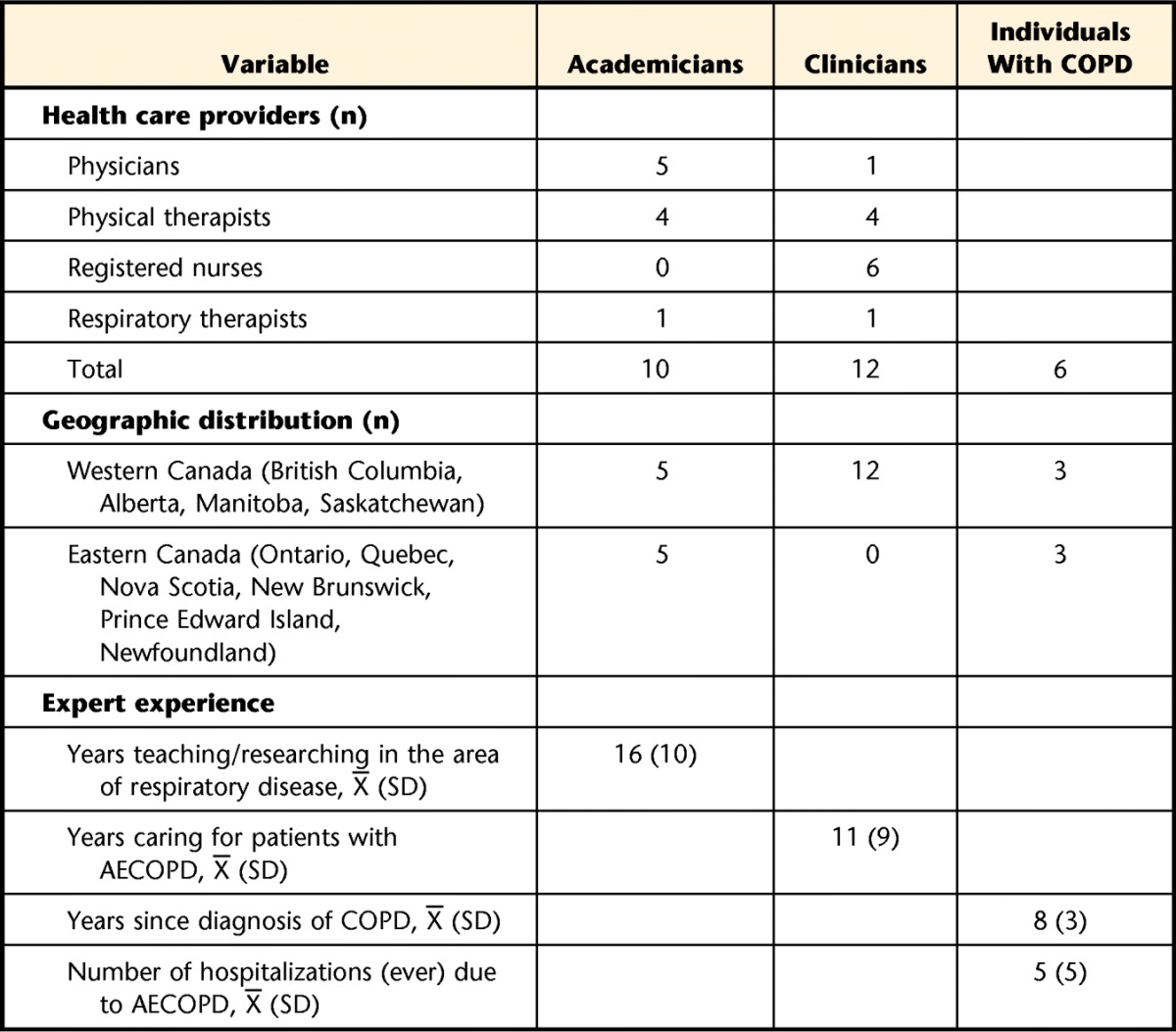

A letter of initial contact was sent to 139 potential panelists (57 academicians, 56 clinicians, and 26 individuals with COPD). Of these, 33 panelists provided written informed consent to participate. One clinician panelist did not meet the inclusion criteria on further discussion, and 3 individuals with COPD withdrew due to health reasons, leaving 29 participants (9 academicians, 13 clinicians, and 7 individuals with COPD) for the Delphi panel. One patient dropped out after receiving the questionnaire. Twenty panelists were from western Canada, and 8 panelists were from eastern Canada. Table 1 describes the characteristics of the 28 Delphi panel members for round 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Delphi Panel Participantsa

COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, AECOPD=acute exacerbation of COPD.

Round 1

The panelists provided more than 1,000 responses to the questions regarding the parameters for safe and effective exercise for hospitalized patients with COPD. The panel also decided that an 80% consensus was needed to retain a given item. After duplicate items were removed, 265 unique parameters were identified. Panelists provided parameters related to signs and symptoms of safety at rest and during exercise, outcome measures to be used to ensure exercise effectiveness, and items to consider when assessing if the patient is ready for discharge from the acute care setting. Panelists also provided details on the necessary training and experience of the health care professional; the required equipment and other resources to initiate exercise and monitor and progress the patient; and the educational needs of the patient. One patient and one clinician participant requested to drop out of the study after round 1.

Rounds 2 and 3

For round 2, the summarized list of 265 items was sent to the remaining 26 panelists, who confirmed the list of items and made further comments regarding the existing items. No additional items were added. For round 3, the 265 items were sent back to the 26 panelists after being placed into the 5 categories, with an additional question of feasibility. The round 3 questionnaire was returned by 20 participants (2 academicians, 3 clinicians, and 1 patient panelist did not return their questionnaire).

The round 3 panelists identified 110 items that achieved 80% consensus for inclusion in the tool. These items were used, along with information gained from our systematic review, to create the initial draft of the AECOPD-Mob clinical decision-making tool.

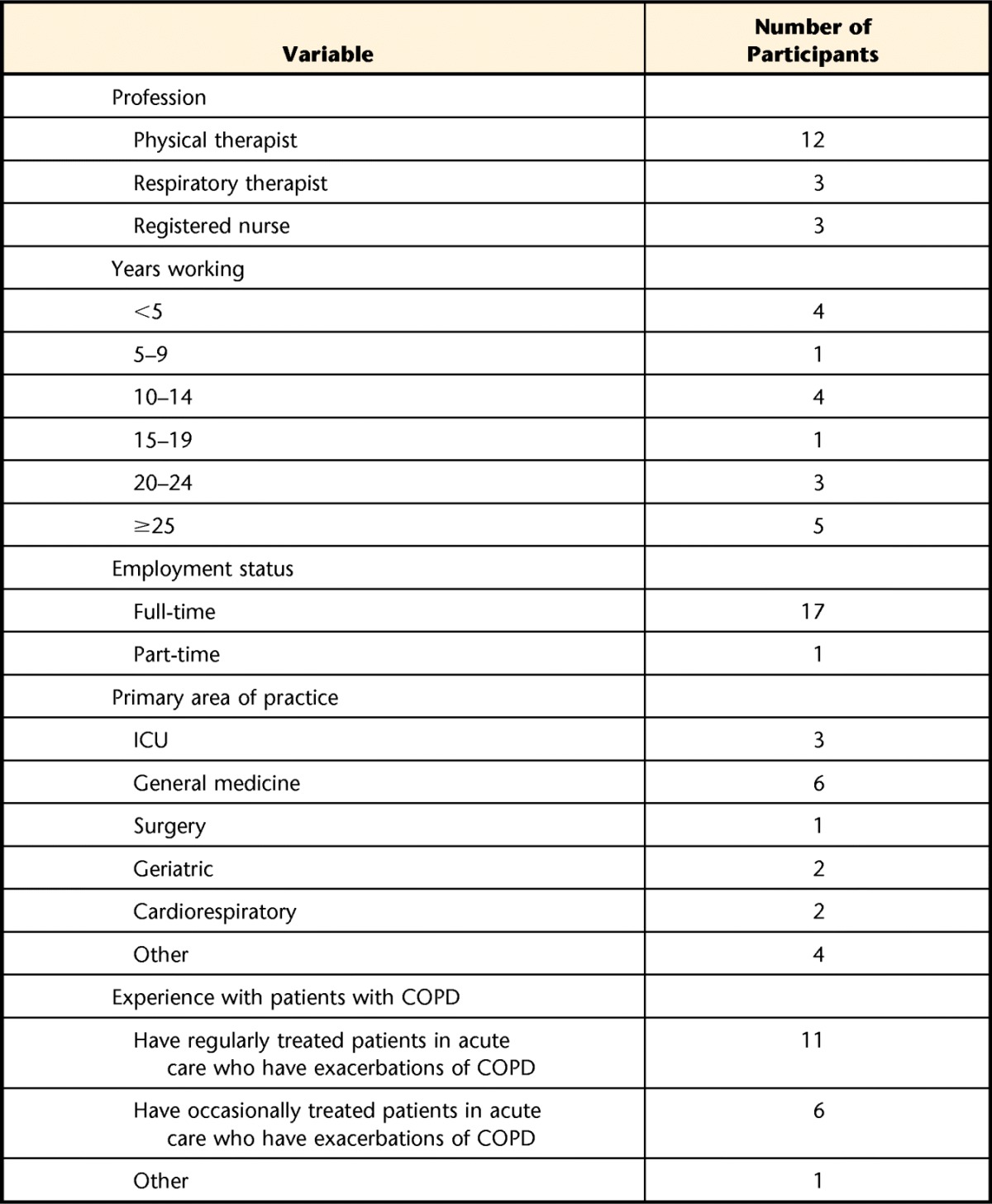

Focus Group Participants

Eighteen health care professionals (12 physical therapists, 3 nurses, and 3 respiratory therapists) participated in 1 of 4 focus groups conducted at acute care hospitals in metropolitan Vancouver. A minimum of 3 to a maximum of 7 health care professionals were in attendance at any one session. Each focus group member provided written informed consent. The characteristics of the focus group participants are described in Table 2. The majority of participants had 10 or more years of work experience in a variety of hospital areas, including general medicine, intensive care, and cardiorespiratory hospital wards.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Focus Group Participantsa

COPD=chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ICU=intensive care unit.

The focus group satisfaction questionnaire results indicated an overall high level of acceptance, with more than 90% of the participants scoring 5 or more on the questions: “I find this tool provides important information I need to safely and effectively mobilize a patient with AECOPD,” “I feel this tool can be applied to a wide range of patients with AECOPD,” “The wording and terminology are easy to understand,” “I feel this tool is comprehensive,” and “I feel this tool would be helpful.” Only 53% of the focus group scored 5 or more for the statement “The font size is appropriate and easy to read,” and 79% scored 5 or more for the statement “The overall length of the document is appropriate.” The panelists discussed the processes they undertook to mobilize their patients with AECOPD in terms of resources, decision making, and support from their team members. Overall, the focus group panelists stated there were few resources that summarize the parameters for safe and effective exercise in AECOPD, especially for the new graduate or health care professional without experience in respiratory acute care settings. They also discussed the challenges they faced when mobilizing these patients. The key strengths and weaknesses of the tool were identified, and the panelists made several suggestions for improvement, including removing redundant information, adding clarification regarding oxygen delivery and anticoagulant values, increasing the font size, removing drug names, and providing multiple ways to deliver the information (eg, posters, smartphone applications, and continuing professional development opportunities). Based on the feedback of the focus groups, the final version of the clinical decision-making tool was created. The final version of the clinical decision-making tool AECOPD-MOB is available at the following website: http://www.prrl.rehab.med.ubc.ca.

Discussion

We utilized an integrated knowledge translation approach to develop a clinical decision-making tool that details the parameters of safe and effective activity and exercise for hospitalized patients with an acute exacerbation of COPD. Informed by our recently published systematic review,13 we created a tool based on extensive input via a formalized Delphi panel consisting of patients and clinicians and researchers in physical therapy, medicine, nursing, and respiratory therapy, followed by focus groups of practicing health care professionals. The information provided enabled the development of a tool that does not focus on exercise prescription alone but comprises the following key elements: assessment, safety, monitoring, progression, and discharge. Although many of the items may be self-evident to experienced practitioners in acute care, they would be helpful to recently graduated physical therapy, nursing, or respiratory therapy health professionals. To date, there are no recognized guidelines that detail specific exercise or activity programs for hospitalized patients with AECOPD.

In 2011, Puhan et al8 published a Cochrane review examining the benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with a recent exacerbation of COPD. This review summarized the findings of 9 trials that provided in-hospital or postdischarge rehabilitation. The meta-analyses demonstrated that pulmonary rehabilitation in the peri-exacerbation period resulted in statistically and clinically significant improvements in 6-minute walk distance and reduced the risk of hospital readmission. However, a wide variety of interventions were studied. Exercise included strength training and continuous and interval aerobic training on a variety of modalities but with inconsistent reporting of the duration, intensity, and progression of exercise. Although this variability of exercise could be interpreted positively (ie, a variety of exercise protocols result in benefit), it would be difficult for the hospital-based health care professional to implement an inpatient program based solely on the information provided in the Cochrane review or in individual papers or guidelines. In the absence of specific recommendations, health care professionals must rely on clinical judgment and experience that could result in underutilization of exercise as a therapeutic intervention.

The tool also may guide practice patterns by reminding health care professionals about the need for and importance of progression of exercise, outcome measures, and discharge planning considerations. Harth et al10 investigated the practice patterns of Canadian physical therapists who assess and treat hospitalized patients with AECOPD. They reported that although objective measures of respiratory impairment (eg, oxygen saturation, chest radiographs, palpation) were used by physical therapists, standardized measures of mobility (eg, Six-Minute Walk Test) and patient-report outcome measures (eg, dyspnea, quality of life) were rarely used. The AECOPD-Mob provides information on both objective and patient-report measures of respiratory, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal impairment and disability. The inclusion of points to guide discharge planning is particularly important. Smith et al18 reported that physical therapists have an important role in discharge planning in acute care. In their study, they found that patients from acute care settings (including medical, surgical, neurology, and trauma/orthopedic services) were 2.9 times more likely to be readmitted when the therapists' discharge recommendations were not followed or when the recommended follow-up care was not available. The items related to discharge planning provide reminders to physical therapists and other health care professionals about AECOPD-related discharge planning, including pulmonary rehabilitation referral, teaching regarding home oxygen, and postdischarge exercise and activity.

This tool may be especially beneficial to new graduates or those without experience in acute care environments. Roskell and Cross19 reported that one third of physical therapy graduates felt less competent to treat patients with cardiorespiratory problems compared with other patient populations. Reeve et al20 also noted that many new graduates consider cardiorespiratory acute care “intimidating.” Acute care of patients with respiratory conditions occurs in hospital environments that are dynamic and extremely complex. Physical therapists and other health care professionals must access, synthesize, and analyze a wide variety of data from multiple sources to develop the care plan for their patients.21 The complexity of this task may be overwhelming for new graduates or health care professionals new to the acute care setting. The decision-making tool is not meant to be prescriptive or provide a “recipe approach” to safe and effective exercise for patients with AECOPD but rather is meant to guide, validate, or remind health care professionals about the necessary components for evidence-based care.

Strengths and Limitations

A key strength of this study was the use of the Delphi method by a panel comprising physical therapists, nurses, respiratory therapists, physicians, and patients to inform the clinical decision-making tool development. This approach enabled us to identify many multidisciplinary aspects of COPD care. The geographical representation of the panelists also ensured that we did not focus on practice patterns unique to a particular region. Nevertheless, we did focus our tool to address practice in Canadian hospital settings. Although we expect that the elements of safe and effective prescription of exercise will translate to other acute care hospital settings, there may be features of the Canadian health care system that are not representative of other jurisdictions. In addition, we were unable to conduct focus groups throughout Canada to gain further feedback on the tool due to resource and time limitations. However, implementation and evaluation of the tool will enable further feedback and tool refinement.

We used an integrated knowledge translation approach to identify the best evidence related to mobilization and exercise in AECOPD, incorporate the expert opinion of a multidisciplinary Delphi panel, and gain feedback from health care professionals via focus groups. Using this approach, we developed a clinical decision-making tool designed to inform and guide health care professionals in the safe and effective prescription of exercise for hospitalized patients with COPD. This tool will provide new graduates or novice acute care practitioners with the necessary information to provide safe and effective exercise and mobility care for their patients.

Appendix 1.

Appendix 1.

Round 1 Questionnairea

a The round 1 questionnaire may not be used or reproduced without written permission from the authors.

Appendix 2.

Appendix 2.

Focus Group Questionsa

a The round 2 questionnaire may not be used or reproduced without written permission from the authors.

Footnotes

Dr Camp, Dr Reid, Mr Chung, Dr Brooks, Dr Goodridge, Dr Marciniuk, and Ms Hoens provided concept/idea/research design. Dr Camp, Mr Chung, Dr Goodridge, Dr Reid, and Ms Hoens provided writing. Dr Camp, Ms Kirkham, and Ms Hoens provided data collection. Dr Camp, Dr Reid, Ms Kirkham, Mr Chung, and Ms Hoens provided data analysis. Dr Camp and Ms Hoens provided project management and institutional liaisons. Dr Camp, Dr Reid, and Ms Hoens provided fund procurement. Dr Camp, Mr Chung, and Ms Hoens provided participants and facilities/equipment. Ms Kirkham provided administrative support. Dr Reid, Mr Chung, Ms Kirkham, Dr Brooks, Dr Marciniuk, and Ms Hoens provided consultation (including review of manuscript before submission).

The authors acknowledge Christen Chan, Cristiane Yamabayashi, and Andrea Neufeld and master of physical therapy students Colin Beattie, Paramjot Bakshi, Tae il Yoon, Debbie Kan, Kayla Comstock, Lauren Courtice, Kira Frew, Monica Jochlin, and Mallory White, who assisted with data collection and analysis of the Delphi panel first-round data and the facilitation and analysis of the focus groups' data. The authors also acknowledge the Physiotherapy Association of British Columbia and the COPD Canada Patient Network for their support of this study and for assistance in recruiting panel participants.

Dr Camp is a Michael Smith Foundation of Health Research Scholar.

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Providence Health Research Institute/University of British Columbia Research Ethics Board (UBC H10-01134) and the Fraser Health Authority (2013-110).

A grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR No: 226908) funded the study.

References

- 1. Mittmann N, Kuramoto L, Seung SJ, et al. The cost of moderate and severe COPD exacerbations to the Canadian healthcare system. Respir Med. 2008;102:413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Camp PG, Chaudhry M, Platt H, et al. The sex factor: epidemiology and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in British Columbia. Can Respir J. 2008;15:417–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garcia-Aymerich J, Farrero E, Félez MA, et al. Risk factors of readmission to hospital for a COPD exacerbation: a prospective study. Thorax. 2003;58:100–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pitta F, Troosters T, Probst VS, et al. Physical activity and hospitalization for exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2006;129:536–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hirsch CH, Sommers L, Olsen A, et al. The natural history of functional morbidity in hospitalized older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:1296–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spruit MA, Gosselink R, Troosters T, et al. Muscle force during an acute exacerbation in hospitalised patients with COPD and its relationship with CXCL8 and IGF-I. Thorax. 2003;58:752–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kortebein P, Ferrando A, Lombeida J, et al. Effect of 10 days of bed rest on skeletal muscle in healthy older adults. JAMA. 2007;297:1772–1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Puhan MA, Gimeno-Santos E, Scharplatz M, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;10:CD005305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Marciniuk DD, Brooks D, Butcher S, et al. Optimizing pulmonary rehabilitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease—practical issues: a Canadian Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Can Respir J. 2010;17:159–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Harth L, Stuart J, Montgomery C, et al. Physical therapy practice patterns in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Can Respir J. 2009;16:86–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoens AM, Li LC. The knowledge broker's “fit” in the world of knowledge translation. Physiother Can. 2014;66:223–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Guide to Knowledge Translation Planning at CIHR: Integrated and End-of-Grant Approaches. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Institutes of Health Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reid WD, Yamabayashi C, Goodridge D, et al. Exercise prescription for hospitalized people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and comorbidities: a synthesis of systematic reviews. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:297–320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Powell C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. J Adv Nurs. 2003;41:376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Okoli C, Pawlowski SD. The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inform Manage. 2004;42:15–29. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Enloe LJ, Shields RK, Smith K, et al. Total hip and knee replacement treatment programs: a report using consensus. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;23:3–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rowe BH, Oxman AD. An assessment of the sensibility of a quality-of-life instrument. Am J Emerg Med. 1993;11:374–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smith BA, Fields CJ, Fernandez N. Physical therapists make accurate and appropriate discharge recommendations for patients who are acutely ill. Phys Ther. 2010;90:693–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roskell C, Cross V. Student perceptions of cardio-respiratory physiotherapy. Physiotherapy. 2003;89:2–12. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Reeve J, Skinner M, Lee A, et al. Investigating factors influencing 4th-year physiotherapy students' opinions of cardiorespiratory physiotherapy as a career path. Physiother Theory Pract. 2012;28:391–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Masley PM, Havrilko CL, Mahnensmith MR, et al. Physical therapist practice in the acute care setting: a qualitative study. Phys Ther. 2011;91:906–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]