Abstract

Gibberellins (GAs) are considered potentially important regulators of cell elongation and expansion in plants. Carrot undergoes significant alteration in organ size during its growth and development. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying gibberellin accumulation and perception during carrot growth and development remain unclear. In this study, five stages of carrot growth and development were investigated using morphological and anatomical structural techniques. Gibberellin levels in leaf, petiole, and taproot tissues were also investigated for all five stages. Gibberellin levels in the roots initially increased and then decreased, but these levels were lower than those in the petioles and leaves. Genes involved in gibberellin biosynthesis and signaling were identified from the carrotDB, and their expression was analyzed. All of the genes were evidently responsive to carrot growth and development, and some of them showed tissue-specific expression. The results suggested that gibberellin level may play a vital role in carrot elongation and expansion. The relative transcription levels of gibberellin pathway-related genes may be the main cause of the different bioactive GAs levels, thus exerting influences on gibberellin perception and signals. Carrot growth and development may be regulated by modification of the genes involved in gibberellin biosynthesis, catabolism, and perception.

Introduction

Plant growth and development is a complex process that involves differentiation and morphogenesis. Hormonal regulation is recognized as a key process in plant growth and development1. For example, gibberellins (GAs) are phytohormones that play essential roles in plant growth and developmental stages, including seed germination, flowering, sex expression, and leaf and fruit senescence2,3. It has been reported that GA-mediated plant growth is mainly achieved by promoting cell elongation in plants4. Further studies indicate that GAs also regulate cell production to control plant growth5. Inadvertently, GA was first discovered in the fungus Gibberella fujikuroi 6. To date, more than 100 GAs have been identified in plants, fungi, and bacteria; however, only a few GAs exhibit biological activities. GA1, GA3, GA4, and GA7 are the major bioactive GAs; other GAs are non-bioactive and act as precursors of the bioactive forms7. To understand the roles of GAs in plant growth and development, researchers should investigate the regulation and response of GAs in plants.

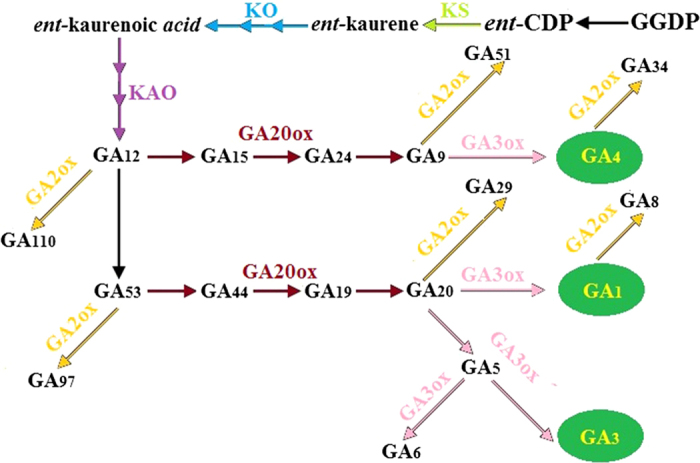

In higher plants, GAs originate from geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP), which is synthesized from isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP)8. GGPP is then converted into ent-kaurene by ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase (CPS) and ent-kaurene synthase (KS). Ent-kaurene is oxidized to GA12-aldehyde, a precursor of all GAs. Finally, GA12-aldehyde is then transformed into various GAs in a process catalyzed by GA20-oxidase (GA20ox), GA3-oxidase (GA3ox), GA2-oxidase (GA2ox), and other enzymes9,10 (Figure 1). Biochemical, molecular, and genetic studies have shown that genes that encode the enzymes in this pathway are essential for GA accumulation and plant growth11–13. The downregulation of the StGA3ox genes in potato alters GA content and affects plant and tuber growth14. Similarly, PsGA3ox1 transgene expression exhibits higher GA1 levels and alters GA biosynthesis and catabolism gene expression as well as plant phenotype15. Gibberellin metabolism, stem growth, and biomass production in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) either increase or decrease when AtGA20ox or AtGA2ox is overexpressed16. Thus, the genes involved in GA biosynthesis and catabolism should be identified to better control GA accumulation and plant growth.

Figure 1.

Proposed pathway for gibberellin (GA) biosynthesis in plants.

Hormone-mediated control of plant growth and development involves both synthesis and response17. DELLA proteins are major inhibitors of plant growth and development18. A bioactive GA binds to a GA receptor, namely, GIBBERELLIN INSENSITIVE DWARF1 (GID1), and forms a GA-GID1 complex; as a result, the degradation of DELLAs is triggered19,20. This mechanism is also called de-repression of GA. Further studies on Arabidopsis and rice have found that a specific ubiquitin E3 ligase complex (SCFSLY1/GID2) is required for this process21. In recent years, positive and negative factors of GA signaling were identified in higher plants22. SLEEPY1 (SLY1), GAMYB, and PICKLE act as positive regulators of gibberellin signaling23,24. Negative regulators of gibberellin signaling include SHORT INTERNODE (SHI), SPINDLY (SPY), and other proteins25,26. Chitin-inducible gibberellin-responsive protein (CIGR) may be involved in GA-mediated phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of DELLAs27.

Carrot (Daucus carota L.), an Apiaceae plant, is commonly consumed worldwide for its nutritional value28. Carrot has also been the focus of many studies aimed at investigating the molecular biology of plants29–31. GA is essential for carrot somatic embryogenesis and is believed to play important roles in stem elongation, root growth, and flower initiation in carrot32–36. However, GA biosynthesis and response in carrot remain unclear. The regulation of GA biosynthesis and response may also differ among organs in the carrot. Thus, GA-mediated plant growth and development in carrot should be studied. Our work aimed to investigate GA metabolism and signaling during carrot growth and development. We attempted to gain more insight into GA biosynthesis and response in carrot. The results from this study also provide useful information for GA-mediated plant growth and development.

Materials and methods

Plant material and growth conditions

The seeds of D. carota L. cv. ‘Kurodagosun’ were cultivated in an artificial chamber at the Nanjing Agricultural University (32°02′N, 118°50′E). The plants were grown at 25°C for 16 h during the daytime followed by 18°C for 8 h in the dark. Samples were collected at 25, 42, 60, 75, and 90 days after sowing (DAS). Morphological characteristics and age were considered to verify the developmental stages. To ensure the accuracy of biochemical and molecular research, whole carrot taproot was collected at each developmental stage. For upper ground tissues, petioles and leaves from whole carrot plants were separately harvested at each developmental stage. The samples of whole taproot, petioles, and leaves were ground in a mortar. The samples were then randomly divided into two groups for GA determination and RNA isolation. Three biological replicates were performed at each collection time point.

Anatomical structure analysis

To examine the growth status of each plant, we investigated the changes in cell structure during carrot growth and development. Fresh samples were cut into small pieces and immediately stored in phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) with 2.5% glutaraldehyde. The slices were dehydrated with ethanol and then treated with epoxy propane. Subsequently, the samples were soaked and embedded in Spurr resin37. A Leica ultramicrotome (Germany) was used to cut the samples into thin sections (∼1 μm), which were stained with 0.5 % methyl violet for 10 min. Then, the slices were observed and then photographed under a Leica DMLS microscope (Germany).

Assay of bioactive GA levels

Samples were ground in a mortar with 10 mL of 80% methanol extraction solution containing 1 mM butylated hydroxytoluene. The extract was incubated at 4°C for 4 h and centrifuged at 3500g for 10 min. Supernatants were then filtered through Chromoseq C18 columns. Efflux was collected and dried with N2. Residues were dissolved in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution containing 0.1 % (v/v) Tween 20 and 0.1 % (w/v) gelatin (pH 7.5). The endogenous levels of bioactive GAs were then determined using an indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described38–40.

Total RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Total RNA was isolated from carrot roots, petioles, and leaves at different stages using an RNAsimple Total RNA Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA quality and concentration was then assessed by gel electrophoresis and the use of a One-Drop spectrophotometer. To eliminate contaminating genomic DNA, we treated total RNA with gDNA Eraser for 2 min at 42°C (TaKaRa, Dalian, China).cDNA was synthesized using PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The cDNA was then diluted 10 times for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis.

Gene expression analysis by quantitative real-time PCR

To identify the genes involved in GA biosynthesis and response in carrot, GA-related genes of Arabidopsis and other plant species were aligned with the sequences in carrotDB, a genomic and transcriptomic database for carrot, which was built by our group (Lab of Apiaceae Plant Genetics and Germplasm Enhancement, http://apiaceae.njau.edu.cn/carrotdb/index.php)29 (Figure S1–S29). Primers used for qRT-PCR were designed with Primer Premier 6 software (Tables 1 and 2). qRT-PCR was performed using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). Each reaction contained 2 μL of diluted cDNA strand, 10 μL of SYBR Premix Ex Taq, 7.4 μL of deionized water, and 0.4 μL of each primer, accumulating a final volume of 20 μL. PCR was strictly performed according to the following standards: 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s and 60°C for 30 s. The experiments were repeated with three independent samples, and the results were normalized against the carrot reference gene, namely, DcActin31. Data from DcGA2ox2 in carrot root at 22 DAS were selected as calibrators for gene expression analysis.

Table 1. Description of pathway-related genes and primers of genes used for qRT-PCR.

| Name | Gene ID | Primer sequences (forward/reverse) |

|---|---|---|

| DcKS | ID49567 | GCGATGGGATGTTGGCGAAGAA/CCGATTGGTGAACTCTGATTGTTGTC |

| DcKO | ID32899 | ATGGTCGCAACAAGTGATTATGATGAG/TCTCTGTTATTACGATGTCGCTTCTGA |

| DcKAO1 | ID50166 | CACAAGCGGCTGAGACGATTAACA/TTCGACCACTTATCCAATGCAGACTT |

| DcKAO2 | ID21746 | AAGAAGAGGAAGAAGATGAGTGATGGT/TCGTATCCTGCAATAACAAGACTGACA |

| DcGA20ox1 | ID43121 | AACCTAATATCGGATGCTCACAAGTCT/AGGTGGATGAGGTCTTCTTAGTAGAGT |

| DcGA20ox2 | ID18860 | AACACCAGAGAAGAACCAGAGTAACAT/GCCTGCCATGACTATGAAGGATGAA |

| DcGA20ox3 | ID44911 | CTTGGTATAGGTCCGTCGTATCTTAGG/ATGTAGGATCACAATGAGGTCCAGTTC |

| DcGA3ox1 | ID40044 | GGAAGAAATGGGATGGGTCACTGT/CCGTTGGTTAGTATGTGGAGCAGAT |

| DcGA3ox2 | ID17101 | AGACTCCCTGCTGCTCACCATTT/CCGATGCTCCTTCTCACTCACGAT |

| DcGA2ox1 | ID44237 | TGTTGATGACTGCCTACAGGTAATGAC/CATGAGTGAAGTTGATGGTGCAATCTT |

| DcGA2ox2 | ID47688 | ACTTATAATCAGAGCCTGCGAAGAACA/GGAAGGATTGGCGTCAAGTAAGAGAT |

| DcGA2ox3 | ID47590 | GCCGTTGATAGCGACCTAATGTTC/CCGTTGGATCTCAAGATGGTGAAGA |

| DcGA2ox4 | ID30452 | TTCAGTTCCAGCAGACCAAGACTC/GCTTGAGCAGTGAAGGCAATGG |

| DcGA2ox5 | ID34042 | TAACCAGCAGTCCCGAATCTCCAT/AAGCGTCCAGAATACACAGCCTTC |

| DcActin | ID41767 | CGGTATTGTGTTGGACTCTGGTGAT/CAGCAAGGTCAAGACGGAGTATGG |

Table 2. Description of selected genes related to gibberellin perception and primers of genes for qRT-PCR.

| Name | Gene ID | Primer sequences (forward/reverse) |

|---|---|---|

| DcGID1a | ID427505 | GCAGCGGAATCAGGAATTGAAGTG/ATGCTCTCCAATACCAATCTCTGTCTC |

| DcGID1b | ID427507 | ATGCTTCGCCGTCCTGATGG/GCTGACCTATAAACACGATTGAGAAG |

| DcGID1c | ID427506 | AACATGCTTCGCCGTCCTGATG/GAACTGCGTTGGGAGGGACTTTG |

| DcDELLA1 | ID48205 | GTCGGATCTTGATGCTTCTATGCTTGA/TTGCTCCACAACCGTGACAATCTC |

| DcDELLA2 | ID31936 | CCTTCGCAGGATAACACGGATCATT/CCACAGCAACCATCACCTTCTCAA |

| DcDELLA3 | ID43703 | TTGAGCGACACGAGACACTGACT/GAGGTAGCAATAAGCGAGCGAGTG |

| DcSLY1 | ID28764 | GATAATTTCGCCGACAATTTCGCTGAT/GCCGTCTTGTTCCACTGCTTGT |

| DcCIGR | ID15901 | CGATAGATGTTAGCCTGCCGAGAG/CTCCAACTTGTAATGCTCCGAGTAAGA |

| DcPICKLE1 | ID46539 | ATGTCCAACTGCTGCTGCTGATAG/TTCCACTTCACAAGATACTGCTTCACA |

| DcPICKLE2 | ID48322 | AAGCGAGCTAGAACGAAGACAACC/CGATGGACTGAGTGAGATGAGATGAC |

| DcSPY | ID47859 | TGGAGAGTTGGAGTCTGCTATCACT/AATATGCCACGCCTTGGTTAATATCG |

| DcGAMYB | ID43195 | ACTATTCCAGCCAGTTGACTTCTCCT/GCGTCGTCTAATGAACTTCCACTAACA |

| DcSHI1 | ID460846 | GCCATTCAGCAGCCACTTAATCTC/AAGCATTGAGCGGAGTTGGATAGA |

| DcSHI2 | ID460843 | GGCAACCAAGCGAAGAAGGATTGTATA/CCAAGAATGTTCACCTGCTGTCTCT |

| DcSHI3 | ID34142 | CAACCTGGTCTCGGATCACTCAAG/CCGCAGTCCTGACAGCTTATGG |

Statistical analysis

Differences in the GA levels during carrot development were detected using Duncan’s multiple-range test at a 0.05 probability level.

Results

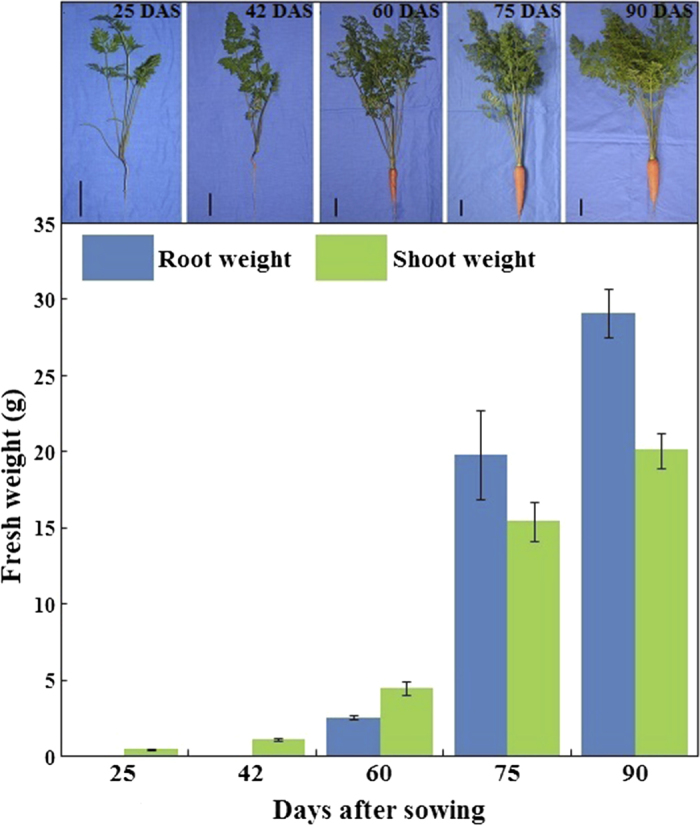

Plant growth analysis

Over the course of growth and development, carrot tissues were harvested at 25, 42, 60, 75, and 90 DAS, respectively (Figure 2). The developmental stages were identified by age and growth indices. The root was white, and the fresh weight of the root was less than that of the shoot at 25 DAS. Up to 42 DAS, the root surface appeared orange, and the root, together with the petioles, was evidently elongated. Root weight and diameter significantly increased between 42 and 60 DAS. Subsequently, the root continued to enlarge, and the root became heavier than the shoot. However, root length presented no evident change (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Description of root weight and shoot weight during carrot growth and development. Carrot samples at 25, 42, 60, 75, and 90 days after sowing were harvested. Black lines in the lower left corner of each plant represent 3 cm in that pixel, whereas error bars represent standard deviation among three independent replicates. Data are the mean ± SD of three replicates.

Structural changes in the roots, petioles, and leaves

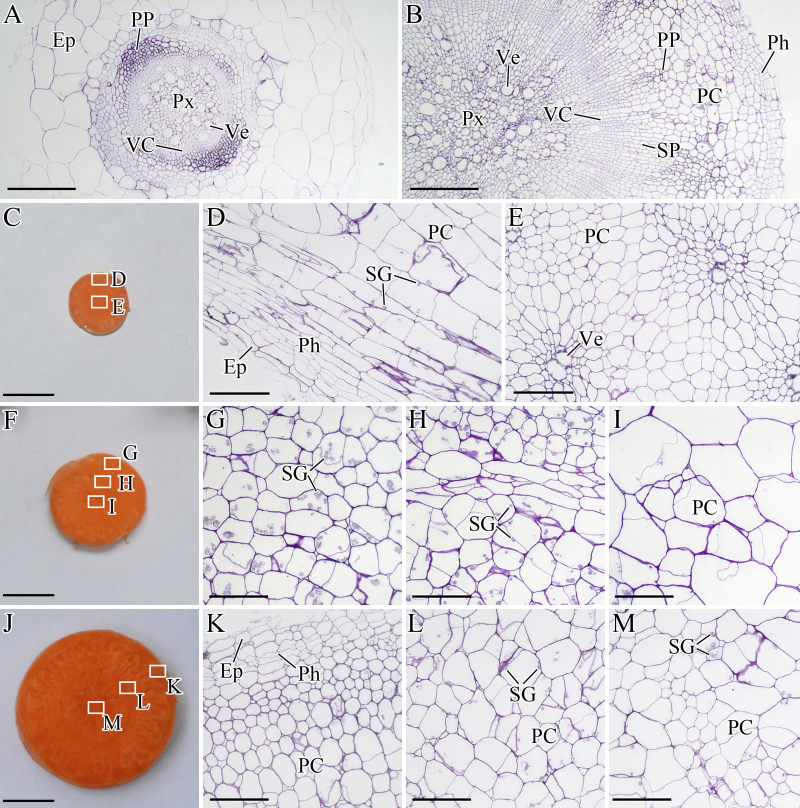

In the roots

At 25 DAS, the root was white, and the vascular cambium (VC) located between primary phloem (PP) and protoxylem (Px) did not show evident thickness (Figure 3A). At 42 DAS, the root surface appeared orange, and VC differentiated outward and inward, forming the secondary phloem (SP) and the secondary xylem (SX), respectively (Figure 3B). Subsequently, the root continued to enlarge (Figure 3C, F, and J).

Figure 3.

Structural changes in the roots during carrot growth and development. The roots were harvested at 25 (A), 42 (B), 60 (C, D, and E), 75 (F, G, H, and I), and 90 (J, K, L, and M) days after sowing. Epidermis (Ep), parenchymalcell (PC), phellogen (Ph), primary phloem (PP), protoxylem (Px), starch granule (SG), secondary phloem (SP), vascular cambium (VC), and vessel (Ve) are marked in the figure. Scale bars in A, B, D, E, G, H, I, K, L, and M are 100 μm in length, whereas bars in C, F, and J are 1 cm in length.

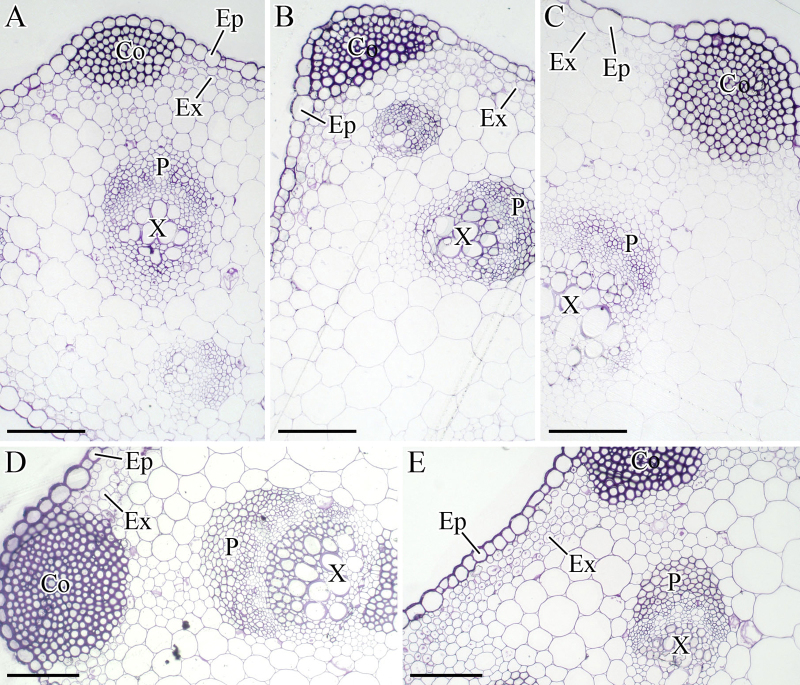

In the petioles

The collenchyma (Co), which provides structural support for carrot growth, was very conspicuous under the microscope (Figure 4). As the plant grew, regions of Co, phloem (P), and xylem(X) were evidently enlarged, suggesting that constant thickness developed in the petioles.

Figure 4.

Structural changes in the petioles during carrot growth and development. The petioles were harvested at 25 (A), 42 (B), 60 (C), 75 (D), and 90 (E) days after sowing. Collenchyma (Co), epidermis (Ep), exodermis (Ex), phloem (P), and xylem (X) were marked in the figure. Scale bars in A, B, C, D, and E are 100 μm in length.

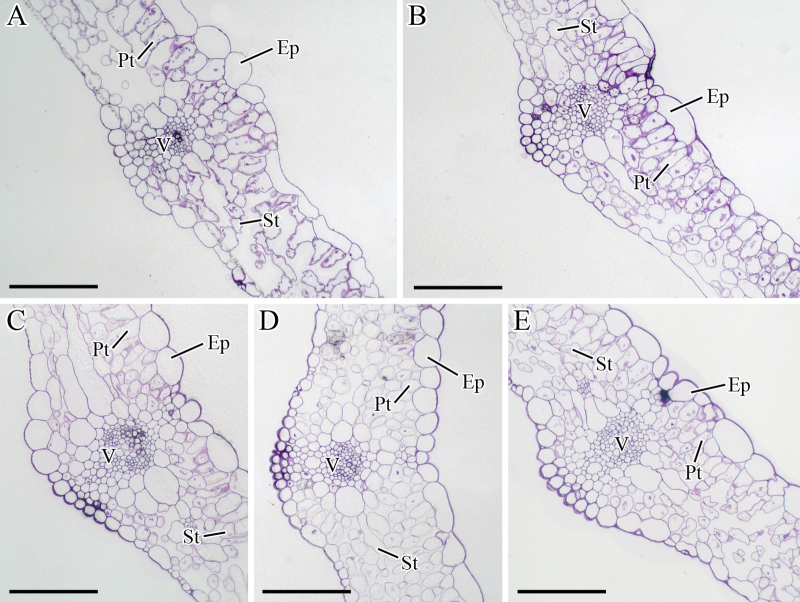

In the leaves

At 25 DAS, the numbers of palisade and spongy cells were limited, and the cell arrangement was disordered (Figure 5A). Subsequently, the leaves expanded, and the cells in the palisade tissue (Pt) and spongy tissue (St) were compactly arranged (Figure 5B–E).

Figure 5.

Structural changes in the leaves during carrot growth and development. The leaves were harvested at 25 (A), 42 (B), 60 (C), 75 (D), and 90 (E) days after sowing. Epidermis (Ep), palisade tissue (Pt), spongy tissue (St), and vascular (V) were marked in figure. Scale bars in A, B, C, D, and E are 100 μm in length.

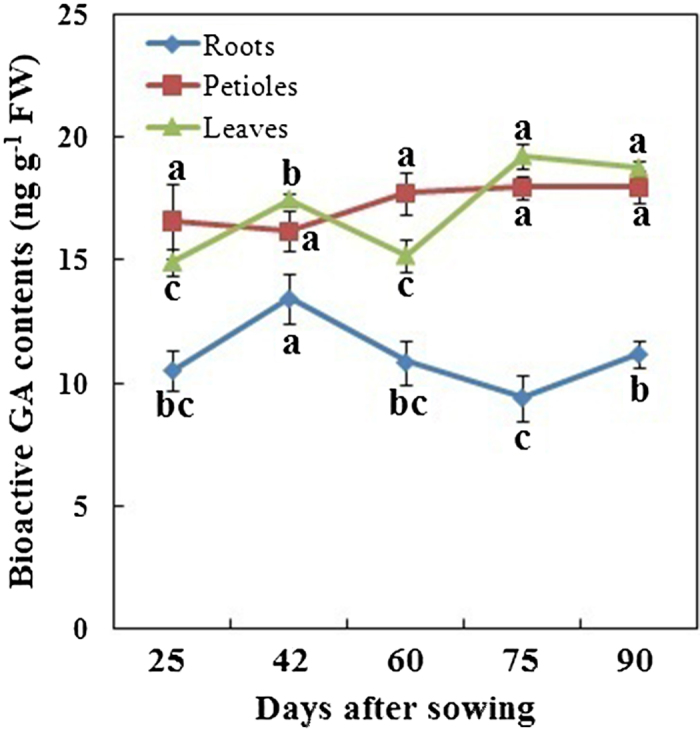

Changes in bioactive GAs

The levels of bioactive GAs (GA1, GA3, GA4, and GA7) were analyzed in the roots, petioles, and leaves during carrot growth and development (Figure 6). For each plant, the bioactive GA contents in the leaves and petioles were higher than those in the roots. During carrot growth, the highest GA levels in the roots were observed at 42 DAS; this level subsequently decreased. However, GA levels in the petioles slightly changed, and the GA levels in the leaves relatively fluctuated.

Figure 6.

Bioactive GAs levels in different tissues during carrot growth and development. Error bars represent the standard deviation among three independent replicates. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three replicates. Different lowercase letters represent significant differences at P <0.05.

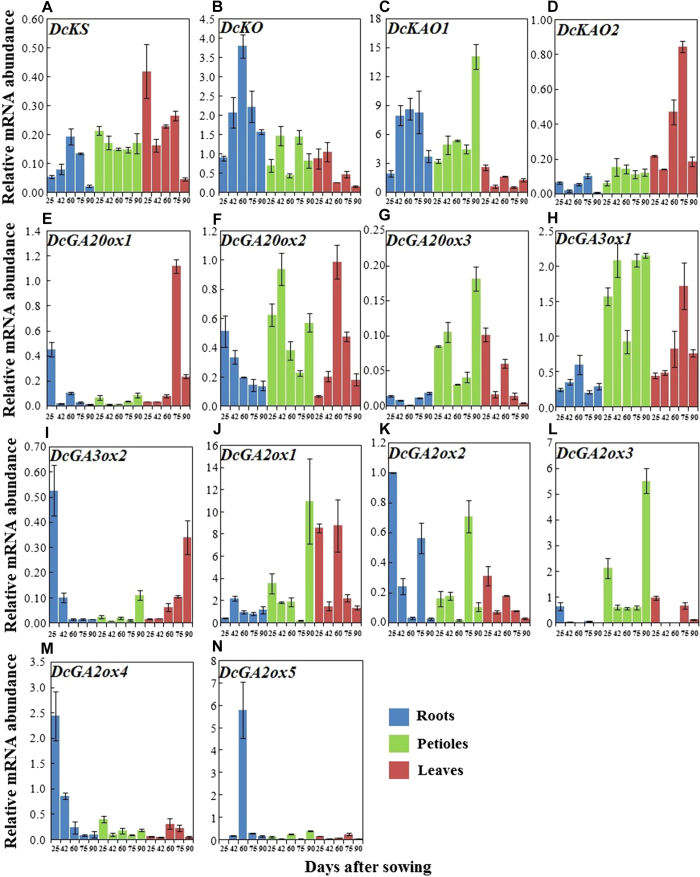

Expression profiles of genes in the GA biosynthetic pathway during carrot growth and development

DcKS, DcKO, DcKAO1, DcKAO2, DcGA20ox1, DcGA20ox2, DcGA20ox3, DcGA3ox1, DcGA3ox2, DcGA2ox1, DcGA2ox2, DcGA2ox3, DcGA2ox4, and DcGA2ox5 were identified from our database. These genes were then selected for qRT-PCR to investigate their expression levels. Biosynthetic pathway-related genes were evidently regulated by carrot growth and development (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

qRT-PCR analysis of genes involved in GA biosynthesis in different tissues during carrot growth and development. Error bars represent the standard deviation among three independent replicates. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three replicates.

In the roots, transcript levels of DcKS, DcKO, DcKAO1, DcGA3ox1, and DcGA2ox5 exhibited a similar pattern, in which an initial increase and a subsequent decrease were observed. In contrast, the mRNA level of DcGA20ox3 initially decreased and then increased. The mRNA levels of DcKAO2, DcGA20ox1, DcGA2ox2, and DcGA2ox3 initially decreased then increased and finally decreased again. Conversely, the mRNA level of DcGA2ox1 showed completely opposite results. However, DcGA20ox2, DcGA3ox2, and DcGA2ox4 constantly decreased over the course of the experiment. In the petioles and leaves, biosynthetic pathway-related genes were also significantly regulated by growth and development.

For the same plant, the expression levels of these genes differed in different tissues. For example, the mRNA levels of DcKAO2 and DcGA3ox1 in the roots were lower than those in the petioles or leaves, whereas DcKO showed the highest level in the roots during carrot growth and development (Figure 7).

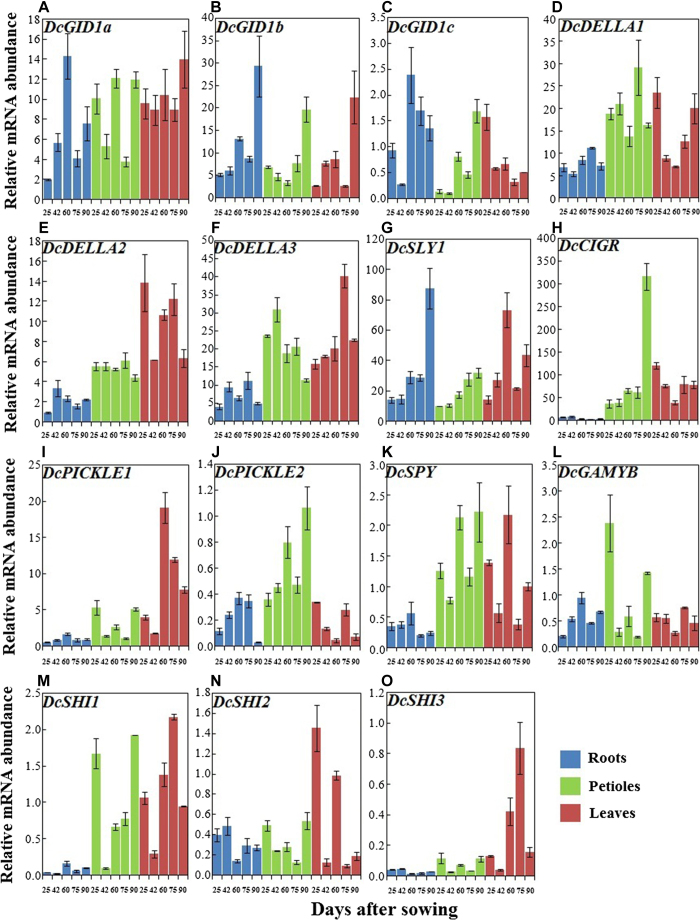

Expression profiles of GA-responsive genes during carrot growth and development

GA perception and subsequent signal transduction are essential for GA functions during plant growth. Thus, GA receptors should be identified to further increase our understanding of the GA signaling pathway. The genes involved in GA response, namely, GID1a, GID1b, GID1c, DcDELLA1, DcDELLA2, DcDELLA3, DcSLY1, DcCIGR, DcPICKLE1, DcPICKLE2, DcSPY, DcGAMYB, DcSHI1, DcSHI2, and DcSHI3 showed marked changes in mRNA levels during plant growth (Figure 8). In the roots, the transcript levels of DcGID1b and DcSLY1 were higher at 90 DAS and lower at 25 and 42 DAS. DcCIGR, DcSHI2, and DcSHI3 showed high expression at 25 and 42 DAS and consistently low expression at the last three time points. DcGID1a, DcGID1c, DcCIGR, DcPICKLE1, DcPICKLE2, DcSPY, DcGAMYB, and DcSHI1 were highly expressed at 60 DAS, whereas transcription of DcDELLA1 was highest at 75 DAS. In the petioles, transcription of DcDELLA3 was highest at 40 DAS. DcGID1b, DcGID1c, DcSLY1, DcCIGR, DcPICKLE2, DcSPY, and DcSHI1 showed high expression at 90 DAS. In the leaves, DcGID1c, DcDELLA1, DcDELLA2, DcCIGR, DcCIGR, DcPICKLE2, and DcSHI2 exhibited the highest mRNA abundance at 25DAS, whereas DcGID1a and DcGID1b showed high expression at 90 DAS.

Figure 8.

qRT-PCR analysis of genes involved in GA response in different tissues during carrot growth and development. Error bars represent standard deviation among three independent replicates. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD of three replicates.

For the same plant, some genes, including DcDELLA1, DcDELLA2, DcDELLA3, DcCIGR, DcPICKLE1, DcSPY, DcSHI1, and DcSHI3, showed the lowest expression in the roots across all growth stages. However, expression patterns of other genes in different tissues may change during plant growth. DcGID1a, DcGID1b, DcDELLA1, DcDELLA2, DcDELLA3, DcSLY1, and DcCIGR were expressed at higher levels than other genes (Figure 8).

Discussion

Hormonal regulation is essential for plant growth and development41,42. Several classes of hormones have been identified, which are ascribed to growth regulation43. Among these hormones, GAs usually promote cell elongation44. Carrot, a root vegetable, is commonly consumed worldwide for its nutritional value. Carrot undergoes significant alterations in its tissues during plant growth. Our previous work suggested that some GA-related genes are differentially expressed at different carrot root developmental stages, indicating that GAs may play important roles in carrot root development29,45. Thus, GA accumulation and its potential role in carrot should be further investigated.

Carrot growth and structural development

In this study, marked elongation and differentiation was observed at 42 DAS, suggesting that this time point may be crucial for root development. Root enlargement can be attributed to the continuous differentiation of VC. A 42-day-old carrot may also be active in pigment accumulation because the root surface first appeared orange during this time46,47. The petiole, as a transport organ, was elongated and thickened during plant growth (Figure 4). The leaves also evidently expanded (Figure 5). Therefore, we aimed to investigate whether GAs are implicated in these processes and to determine the response of carrots to GAs.

GA content and functions

Our results found that the levels of bioactive GAs were higher in the leaves and petioles than in other parts (Figure 6). These findings indicated that GA biosynthesis and catabolism might be tissue-specific48. Previous studies have suggested that GAs are the major promoters of cell elongation49–51. In the current work, the existence of GAs in different tissues may provide constant stimuli for structure formation and development (Figures 3, 4, 5)52. In the roots, the highest levels of bioactive GAs were observed at 42 DAS when an enlargement occurred at the same time (Figure 3). Thus, GAs may play important roles in cell proliferation in carrot growth and development, which is consistent with the results reported by Ubeda-Tomás and colleagues5.

GA biosynthesis and catabolism

GAs are present in all tissues and are essential for carrot growth. However, our results found that GA levels may differ in various carrot tissues. GA levels were also significantly altered during carrot growth. Thus, GA production and regulation should be understood. In this study, the expression levels of 14 genes involved in GA biosynthesis were studied during carrot growth and development. All of these genes responded to the growth stages, thereby eliciting evident influence on the GA levels. However, the expression patterns were incompletely consistent with the GA levels possibly because of the feedback mechanisms of GAs53–55. Other hormones may also play vital roles in GA biosynthesis and metabolism, indicating a complex mechanism of GA biosynthesis and catabolism56,57. DcKAO2, DcGA3ox1, and DcGA2ox3 also showed tissue-specific expression patterns. This interesting observation may partly explain the different GA levels in the different tissues.

GA response and regulators

GA perception and signaling transduction are also important for GA-mediated plant growth and development. A GA-GID1-DELLA signaling module has been extensively described21,58. A total of 15 receptors or acting components in this module were investigated using qRT-PCR during carrot growth. These genes were evidently regulated by carrot growth and development, and this result indicated that this module is also present in carrot.

The transcripts of DcDELLA1, DcDELLA2, DcDELLA3, DcCIGR, DcPICKLE1, DcSPY, DcSHI1, and DcSHI3 were higher in the petioles and leaves than in the roots. This observation was consistent with the GA levels among different tissues, which indirectly suggested that bioactive GAs are produced at their site of action59,60.

Interestingly, genes encoding DELLAs in the current study were expressed at high levels. Two main factors support this finding. First, high DcDELLA transcript levels suggested that DELLAs may be the main restraints in plant growth61,62. Second, DELLA homeostasis could balance or relieve the cues induced by GAs or other hormones63, thereby stabilizing plant growth.

Conclusions

The morphological and anatomical structure of roots, petioles, and leaves were significantly altered during carrot plant growth. GAs may play important roles in the elongation and expansion of carrot tissues. The relative transcript levels of pathway-related genes may be the main cause for the different levels of bioactive GAs, therefore exerting influences on gibberellin perception and signals. Carrot growth and development may be regulated by modification of the genes involved in gibberellin biosynthesis, catabolism, and perception.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: Ai-Sheng Xiong and Guang-Long Wang. Performed the experiments: Guang-Long Wang, Fei Xiong, Feng Que, Zhi-Sheng Xu, and Feng Wang. Analyzed the data: Guang-Long Wang. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: Ai-Sheng Xiong. Wrote the paper: Guang-Long Wang. Revised the paper: Guang-Long Wang and Ai-Sheng Xiong. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by the following: New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-11-0670); Jiangsu Natural Science Foundation (BK20130027); the Open Project of State Key Laboratory of Crop Genetics and Germplasm Enhancement (ZW2014007); and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ordaz-Ortiz JJ, Foukaraki S, Terry LA. Assessing temporal flux of plant hormones in stored processing potatoes using high definition accurate mass spectrometry. Hort Res 2015; 2: 15002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Qin L, Lee S, Fu X, Richards DE, Cao D et al. Gibberellin regulates Arabidopsis floral development via suppression of DELLA protein function. Development 2004; 131: 1055–1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, Hanada A, Yamauchi Y, Kuwahara A, Kamiya Y, Yamaguchi S. Gibberellin biosynthesis and response during Arabidopsis seed germination. Plant Cell 2003; 15: 1591– 1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inada S, Shimmen T. Regulation of elongation growth by gibberellin in root segments of Lemna minor. Plant Cell Physiol 2000; 41: 932–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ubeda-Tomás S, Federici F, Casimiro I, Beemster GTS, Bhalerao R, Swarup R et al. Gibberellin signaling in the endodermis controls Arabidopsis root meristem size. Curr Biol 2009; 19: 1194–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P, Phillips AL, Rojas MC, Carrera E, Tudzynski B. Gibberellin biosynthesis in plants and fungi: a case of convergent evolution? J Plant Growth Regul 2001; 20: 319–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S. Gibberellin metabolism and its regulation. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2008; 59: 225–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P, Phillips AL. Gibberellin metabolism: new insights revealed by the genes. Trends Plant Sci 2000; 5: 523–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song J, Guo B, Song F, Peng H, Yao Y, Zhang Y et al. Genome-wide identification of gibberellins metabolic enzyme genes and expression profiling analysis during seed germination in maize. Gene 2011; 482: 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedden P, Proebsting WM. Genetic analysis of gibberellin biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 1999; 119: 365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sharkawy I, Sherif S, El Kayal W, Mahboob A, Abubaker K, Ravindran P et al. Characterization of gibberellin-signalling elements during plum fruit ontogeny defines the essentiality of gibberellin in fruit development. Plant Mol Biol 2014; 84: 399–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozga JA, Reinecke DM, Ayele BT, Ngo P, Nadeau C, Wickramarathna AD. Developmental and hormonal regulation of gibberellin biosynthesis and catabolism in pea fruit. Plant Physiol 2009; 150: 448–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regnault T, Davière JM, Heintz D, Lange T, Achard P. The gibberellin biosynthetic genes AtKAO1 and AtKAO2 have overlapping roles throughout Arabidopsis development. Plant J 2014; 80: 462–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumeliotis E, Kloosterman B, Oortwijn M, Lange T, Visser RGF, Bachem CWB. Down regulation of StGA3ox genes in potato results in altered GA content and affect plant and tuber growth characteristics. J Plant Physiol 2013; 170: 1228–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinecke DM, Wickramarathna AD, Ozga JA, Kurepin LV, Jin AL, Good AG et al. Gibberellin 3-oxidase gene expression patterns influence gibberellin biosynthesis, growth, and development in pea. Plant Physiol 2013; 163: 929–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biemelt S, Tschiersch H, Sonnewald U. Impact of altered gibberellin metabolism on biomass accumulation, lignin biosynthesis, and photosynthesis in transgenic tobacco plants. Plant Physiol 2004; 135: 254–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima M, Shimada A, Takashi Y, Kim YC, Park SH, Ueguchi-Tanaka M et al. Identification and characterization of Arabidopsis gibberellin receptors. Plant J 2006; 46: 880–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q, Wang W, Guo X, Yue J, Huang Y, Xu X et al. Arabidopsis DELLA protein degradation is controlled by a type-one protein phosphatase, TOPP4. PLoS Genet 2014; 10: e1004464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Giraldo C, Hu J, Urbez C, Gomez MD, Sun TP, Perez-Amador MA. Role of the gibberellin receptors GID1 during fruit-set in Arabidopsis. Plant J 2014; 79: 1020–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukazawa J, Teramura H, Murakoshi S, Nasuno K, Nishida N, Ito T et al. DELLAs function as coactivators of GAI-ASSOCIATED FACTOR1 in regulation of gibberellin homeostasis and signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2014; 26: 2920–2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TP. Gibberellin-GID1-DELLA: a pivotal regulatory module for plant growth and development. Plant Physiol 2010; 154: 567–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TP, Gubler F. Molecular mechanism of gibberellin signaling in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2004; 55: 197–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogas J, Cheng JC, Sung ZR, Somerville C. Cellular differentiation regulated by gibberellin in the Arabidopsis thaliana pickle mutant. Science 1997; 277: 91–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis KM, Thomas SG, Soule JD, Strader LC, Zale JM, Sun TP et al. The Arabidopsis SLEEPY1gene encodes a putative F-box subunit of an SCF E3 ubiquitin ligase. Plant Cell 2003; 15: 1120–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain SM, Tseng TS, Thornton TM, Gopalraj M, Olszewski NE. SPINDLY is a nuclear-localized repressor of gibberellin signal transduction expressed throughout the plant. Plant Physiol 2002; 129: 605–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridborg I, Kuusk S, Moritz T, Sundberg E. The Arabidopsis dwarf mutant shi exhibits reduced gibberellin responses conferred by overexpression of a new putative zinc finger protein. Plant Cell 1999; 11: 1019–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day RB, Tanabe S, Koshioka M, Mitsui T, Itoh H, Ueguchi-Tanaka M et al. Two rice GRAS family genes responsive to N-acetylchitooligosaccharide elicitor are induced by phytoactive gibberellins: evidence for cross-talk between elicitor and gibberellin signaling in rice cells. Plant Mol Biol 2004; 54: 261–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luby CH, Maeda HA, Goldman IL. Genetic and phenological variation of tocochromanol (vitamin E) content in wild (Daucus carota L. var. carota) and domesticated carrot (D. carota L. var. sativa). Hort Res 2014; 1: 14015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu ZS, Tan HW, Wang F, Hou XL, Xiong AS. CarrotDB: a genomic and transcriptomic database for carrot. Database 2014; 2014: bau096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu ZS, Huang Y, Wang F, Song X, Wang GL, Xiong AS. Transcript profiling of structural genes involved in cyanidin-based anthocyanin biosynthesis between purple and non-purple carrot (Daucus carota L.) cultivars reveals distinct patterns. BMC Plant Biol 2014; 14: 262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TianC JiangQ, Wang F, Wang GL, Xu ZS, Xiong AS. Selection of suitable reference genes for qPCR normalization under abiotic stresses and hormone stimuli in carrot leaves. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0117569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuji Y, Kuriyama K. Involvement of gibberellin and cytokinin in the formation of embryogenic cell clumps in carrot (Daucus carota). J Plant Physiol 2003; 160: 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiller LK, Kelly WC, Powell LE. Temperature interactions with growth regulators and endogenous gibberellin-like activity during seedstalk elongation in carrots. Plant Physiol 1979; 63: 1055–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currah IE, Thomas TH. Vegetable plant part relationships. III. Modification of carrot (Daucus carota L.) root and shoot weights by gibberellic acid and daminozide. Ann Bot 1979; 43: 501–511. [Google Scholar]

- McKee JMT, Morris GEL. Effects of gibberellic acid and chlormequat chloride on the proportion of phloem and xylem parenchyma in the storage root of carrot (Daucus carota L.). Plant Growth Regul 1986; 4: 203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwhof M. Effect of gibberellic acid on bolting and flowering of carrot (Daucus carota L.). Sci Hort 1984; 24: 211–219. [Google Scholar]

- Spurr AR. A low-viscosity epoxy resin embedding medium for electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Res 1969; 26: 31–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YM, Xu CN, Wang BM, Jia JZ. Effects of plant growth regulators on secondary wall thickening of cotton fibres. Plant Growth Regul 2001; 35: 233–237. [Google Scholar]

- Teng N, Wang J, Chen T, Wu X, Wang Y, Lin J. Elevated CO2 induces physiological, biochemical and structural changes in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 2006; 172: 92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S, Gao F, Cao X, Chen M, Ye G, Wei C et al. The rice dwarf virus P2 protein interacts with ent-kaurene oxidases in vivo, leading to reduced biosynthesis of gibberellins and rice dwarf symptoms. Plant Physiol 2005; 139: 1935–1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang YC, Reid MS, Jiang CZ. Controlling plant architecture by manipulation of gibberellic acid signalling in petunia. Hort Res 2014; 1: 14061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gapper NE, Giovannoni JJ, Watkins CB. Understanding development and ripening of fruit crops in an ‘omics’ era. Hort Res 2014; 1: 14034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santner A, Estelle M. Recent advances and emerging trends in plant hormone signalling. Nature 2009; 459: 1071–1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depuydt S, Hardtke CS. Hormone signaling crosstalk in plant growth regulation. Curr Biol 2011; 21: R365–R373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GL, Jia XL, Xu ZS, Wang F, Xiong AS. Sequencing, assembly, annotation, and gene expression: novel insights into the hormonal control of carrot root development revealed by a high-throughput transcriptome. Mol Genet Genomics 2015; 1: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telias A, Hoover E, Rother D. Plant and environmental factors influencing the pattern of pigment accumulation in ‘Honeycrisp’ apple peels using a novel color analyzer software tool. HortScience 2008; 43: 1441–1445. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Uribe L, Guzman I, Rajapakse W, Richins RD, O’Connell MA. Carotenoid accumulation in orange-pigmented Capsicum annuum fruit, regulated at multiple levels. J Exp Bot 2012; 63: 517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau CD, Ozga JA, Kurepin LV, Jin A, Pharis RP, Reinecke DM. Tissue-specific regulation of gibberellin biosynthesis in developing pea seeds. Plant Physiol 2011; 156: 897–912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lucas M, Daviere JM, Rodriguez-Falcon M, Pontin M, Iglesias-Pedraz JM, Lorrain S et al. A molecular framework for light and gibberellin control of cell elongation. Nature 2008; 451: 480–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowling RJ, Harberd NP. Gibberellins control Arabidopsis hypocotyl growth via regulation of cellular elongation. J Exp Bot 1999; 50: 1351–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Ayano M, Kani T, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Kitaoka T, Kuroha T et al. Gibberellin biosynthesis and signal transduction is essential for internode elongation in deepwater rice. Plant Cell Environ 2014; 37: 2313–2324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelissen H, Rymen B, Jikumaru Y, Demuynck K, Van Lijsebettens M, Kamiya Y et al. A local maximum in gibberellin levels regulates maize leaf growth by spatial control of cell division. Curr Biol 2012; 22: 1183–1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleet CM, Yamaguchi S, Hanada A, Kawaide H, David CJ, Kamiya Y et al. Overexpression of AtCPS and AtKS in Arabidopsis confers increased ent-Kaurene production but no increase in bioactive gibberellins. Plant Physiol 2003; 132: 830–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SG, Phillips AL, Hedden P. Molecular cloning and functional expression of gibberellin 2-oxidases, multifunctional enzymes involved in gibberellin deactivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1999; 96: 4698–4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S, Smith MW, Brown RGS, Kamiya Y, Sun TP. Phytochrome regulation and differential expression of gibberellin 3β-hydroxylase genes in germinating Arabidopsis seeds. Plant Cell 1998; 10: 2115–2126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszewski N, Sun TP, Gubler F. Gibberellin signaling: biosynthesis, catabolism, and response pathways. Plant Cell 2002; 14: S61–S80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouquin T, Meier C, Foster R, Nielsen ME, Mundy J. Control of specific gene expression by gibberellin and brassinosteroid. Plant Physiol 2001; 127: 450–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun TP. The molecular mechanism and evolution of the GA–GID1–DELLA signaling module in plants. Curr Biol 2011; 21: R338–R345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone AL, Chang CW, Krol E, Sun TP. Developmental regulation of the gibberellin biosynthetic gene GA1 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 1997; 12: 9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko M, Itoh H, Inukai Y, Sakamoto T, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Ashikari M et al. Where do gibberellin biosynthesis and gibberellin signaling occur in rice plants? Plant J 2003; 35: 104–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard P, Vriezen WH, Van Der Straeten D, Harberd NP. Ethylene regulates Arabidopsis development via the modulation of DELLA protein growth repressor function. Plant Cell 2003; 15: 2816–2825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achard P, Genschik P. Releasing the brakes of plant growth: how GAs shutdown DELLA proteins. J Exp Bot 2009; 60: 1085–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZL, Ogawa M, Fleet CM, Zentella R, Hu J, Heo JO et al. Scarecrow-like 3 promotes gibberellin signaling by antagonizing master growth repressor DELLA in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108: 2160–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.