Abstract

Context:

A rare presentation of hypothalamic tumors in infants and young children is profound emaciation and generalized loss of sc adipose tissue, also known as “diencephalic syndrome.” Similar loss of sc fat can be observed in children with acquired generalized lipodystrophy or congenital generalized lipodystrophy. Precise diagnosis may be challenging early in the course of the disease, especially in the absence of metabolic abnormalities.

Case Description:

We report three males who presented with poor weight gain and generalized loss of sc fat at birth to 3 years of age consistent with generalized lipodystrophy, with subsequent development of pilocytic astrocytoma. Two of them had hypothalamic tumors, and one had a multicentric tumor with a large right parietal mass. Our patients are unique because the onset of lipodystrophy occurred 2.5 to 7.3 years before the diagnosis of brain tumor, and all of them gained body fat or weight after surgical removal and/or chemotherapy. One patient had hepatosplenomegaly and impaired glucose tolerance, and another patient had severe hyperglycemia and hypertriglyceridemia during the course of the disease. Two patients presented with central precocious puberty and advanced bone age at the chronological age of 6 years.

Conclusions:

It is likely that pilocytic astrocytoma may induce generalized lipodystrophy by paraneoplastic antiadipocyte antibody formation or by excessive hormones or cytokine secretion resulting in excess lipolysis from adipocytes. We conclude that young children presenting with idiopathic acquired generalized lipodystrophy or atypical congenital generalized lipodystrophy, with or without metabolic abnormalities, should prompt investigation for brain tumors.

A rare presentation of hypothalamic tumors in infants and young children is profound emaciation and generalized loss of sc fat, with either normal or slightly diminished energy intake, also known as “diencephalic syndrome.” It is commonly associated with low-grade gliomas but can occur with other tumors (1–7). Similar loss of sc fat can be observed during childhood in rare patients with acquired generalized lipodystrophy (AGL) or congenital generalized lipodystrophy (CGL). Precise diagnosis therefore may be challenging early in the course of the disease. We report three cases who presented initially with AGL or CGL but subsequently developed pilocytic astrocytomas.

Case Reports

The protocol was approved by Institutional Review Board at UT Southwestern, Dallas, Texas. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents of the patients.

Case 1

This Caucasian male from the United States stopped gaining weight at about 5 months of age, despite good appetite, and developed prominent musculature with sc fat loss. At 10 months, his weight was 8 kg (15th percentile) and length was 73.6 cm (73rd percentile). He had generalized loss of sc fat, sparing the palms and soles (Figure 1A), 4-cm hepatomegaly, 3-cm splenomegaly, and normal metabolic profile (Table 1).

Figure 1.

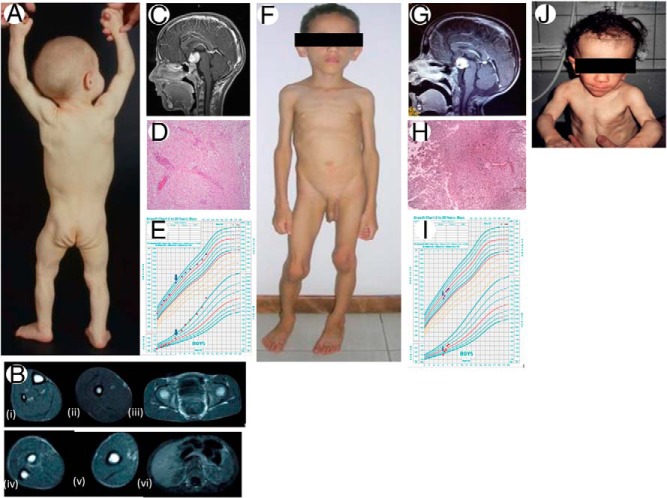

Clinical features and magnetic resonance images (MRIs), pathology of brain tumors, and growth patterns of our patients. A, Posterior view of case 1 at age 10 months showing generalized lack of body fat and prominent muscularity. B, Axial T-1-weighted MRIs of case 1 at 4½ years of age showing complete absence of sc fat from the calf (i); thigh (ii); buttocks and pelvis (iii); forearm (iv); arm (v); and absence of sc and visceral fat from abdomen (vi). Bone marrow fat appears normal. C, Sagittal view of T-1-weighted MRI brain of case 1 at 6 years and 10 months of age showing a 2.7 × 2.9 × 2.2-cm hypothalamic chiasmatic mass. D, Photomicrograph (hematoxylin and eosin; magnification, ×100) of brain tumor of case 1 showing mildly cellular neoplasm composed of bland-appearing glial cells embedded in a fibrillary and myxoid background consistent with pilocytic astrocytoma WHO grade 1. Many tumor cells show clear cytoplasm. Other cells show cytoplasmic processes that are often bipolar. Scattered blood vessels show hyalinized walls and perivascular lymphocytes. E, Growth chart for case 1. The blue arrows depict age of resection of pilocytic astrocytoma. Patient had significant weight gain after the resection of the tumor. F, Anterior view of case 2 at 4 years of age showing generalized absence of sc fat, muscularity, and protuberant abdomen. G, Sagittal view of T-1-weighted MRI brain of case 2 at 5.5 years of age showing a 2.6 × 2.4 × 1.9-cm solid lesion in the optic chiasmatic region. H, Photomicrograph (hematoxylin and eosin; magnification, ×100) of brain tumor of case 2 showing pilocytic astrocytoma WHO grade 1. The center and upper right quadrant shows dense and compact background with greater cellularity and hyalinized vessels surrounded by areas of a less dense fibrillar material and lower cellularity. I, Growth chart for case 2. The arrows depict age at initiation of chemotherapy for treatment of pilocytic astrocytoma. The patient had significant weight gain after treatment of tumor with chemotherapy. J, Anterior view of case 3 at age 15 months. There is complete absence of sc fat and extreme muscularity.

Table 1.

Metabolic Variables in Our Patients

| Variable | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 10 mo | 5.5 y | 13 mo | |

| Fasting blood glucose, mg/dL | 94 | 70 | 91 | 70–99 |

| Hemoglobin A1c, mmol/mol | 32.2 | NA | 16.7 | <38.8 |

| Fasting insulin, μIU/mL | NA | 2 | 2.6 | 2.0–19.6 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 124 | 125 | 112 | <170 |

| LDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 64 | 68 | 73 | <110 |

| HDL-cholesterol, mg/dL | 35 | 49 | 19 | 38–76 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL | 123 | 39 | 159 | 35–130 |

| AST, IU/L | 30 | 30 | NA | 10–42 |

| ALT, IU/L | 26 | 16 | NA | 10–40 |

Abbreviations: LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; NA, not available.

At 4.5 years of age, he had impaired oral glucose tolerance, with a 2-hour postprandial glucose of 166 mg/dL. His total body fat estimated by dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry scan was 11.7% (normal mean ± SD using version 12.1 software for 3- to 5-y-old boys, n = 84, 27.0 ± 6.1%) (8). His full body magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed generalized loss of sc fat (Figure 1B) without any evidence of brain tumor. At 6 years of age, early Tanner stage 2 pubic hair and testes were noted. His bone age was advanced to 10 years. Serum T (288 ng/dL), LH (1.51 mIU/mL), and FSH (1.21 mIU/mL) were consistent with central precocious puberty. A brain MRI showed a hypothalamic chiasmatic 2.7 × 2.9 × 2.2-cm mass (Figure 1C). The mass was surgically removed, histopathology showed pilocytic astrocytoma (World Health Organization [WHO] grade I) (Figure 1D), and chemotherapy with carboplatin and vincristine was initiated. The patient did well and gained weight, from 22.4 to 40 kg, over a 2-year period (Figure 1E). His pubertal progression ceased with GnRH analog treatment, which was continued until age 11 years.

Case 2

This Caucasian male from Brazil, born to consanguineous parents with a weight of 3.18 kg and a length of 48 cm, began to have poor weight gain and generalized loss of sc fat at age 3 years despite good appetite (Figure 1F). At age 5.5 years, his weight was 14.5 kg (<3rd percentile), and height was 108 cm (25th percentile). He had coarse scalp hair, but no acanthosis nigricans or hepatomegaly. His metabolic profile was normal (Table 1).

A diagnosis of idiopathic AGL was considered; however, a brain MRI at age 5.5 years showed a 2.6 × 2.4 × 1.9-cm solid lesion in the optic chiasmatic region (Figure 1G). Tumor biopsy showed a pilocytic astrocytoma, WHO grade I (Figure 1H). Chemotherapy with vincristine + carboplatin + cyclophosphamide was initiated at 6 years of age, and the patient gained weight, from 15 to 22 kg, over the next year (Figure 1I). At 6.3 years, enlargement of the penis, deepening of the voice, and axillary hair were noted. He had pubertal T (380 ng/dL), LH (8.7 mIU/mL), and FSH (3.6 mIU/mL). He was started on GnRH analog at 6.6 years of age with cessation of pubertal progression. MRI at age 7 years showed a reduction in tumor size to 1.8 × 1.0 × 1.4 cm. At 8 years, on GnRH analog treatment and chemotherapy, he has complete remission of lipodystrophy based on clinical examination and no neurological deficit.

Case 3

This 15-year-old Caucasian male from Germany had generalized lipodystrophy at birth (9), along with hypertonia, umbilical hernia, single palmar crease, delayed closure of fontanelle, and triangular face with prominent nose and chin (Figure 1J). He also had short stature and cardiomyopathy and later developed joint contractures and mild mental retardation. He had markedly elevated blood glucose of approximately 300 mg/dL and triglycerides of approximately 2000 mg/dL, lactic acidosis, and a low leptin level (0.01 ng/mL). Hepatic ultrasound revealed steatosis. His initial brain MRI showed no evidence of brain tumor. Genotyping for known CGL loci, AGPAT2, BSCL2, CAV1, and PTRF was negative.

He was treated with medium chain triglyceride containing oil in infancy and a low-fat diet thereafter. Blood glucose values have been normal, but he has mildly low high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and elevated triglyceride (Table 1). At age 7.3 years, the patient developed a progressive left side paralysis. Brain MRI showed a 6 × 7 × 6-cm right parietal mass and small lesions in the right cerebellum and globus pallidus. Biopsy of the right parietal mass revealed pilocytic astrocytoma, WHO grade I, and the mass was surgically removed. The patient had relapses at ages 8.5 and 10 years, respectively, requiring repeat resections. The pathology showed anaplastic astrocytoma with the second relapse, and he was treated with radiotherapy and temozolomide. He started puberty at age 11 years with FSH and LH levels being 4.44 and 0.54 mIU/mL, respectively. A whole-body MRI at age 11.5 years showed a slight increase of sc, orbital, and intra-abdominal fat, which had been absent in the neonatal period.

Discussion

Diencephalic syndrome was first described by Russell (7) in five children with hypothalamic astrocytoma who presented with profound emaciation, initial growth acceleration, locomotor overactivity, and euphoria. Since then, it is considered a rare cause of failure to thrive below age 2 years (3, 5, 10, 11). Older children with similar brain tumors instead develop obesity, precocious puberty, and diabetes insipidus (1–4, 10). However, impaired glucose tolerance, diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia, and hepatosplenomegaly have not been reported in patients with diencephalic syndrome (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical Features of Diencephalic Syndrome and Our Patients

| Clinical Features | Diencephalic Syndrome | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at onset of fat loss | <2 y | 5 mo | 3 y | At birth |

| Age at diagnosis, y | <2 | 6 | 5.5 | 7.3 |

| Generalized loss of sc fat | + | + | + | + |

| Emaciation | + | − | − | − |

| Prominent musculature | − | + | + | + |

| Appetite | ↓ | ↑ | N | N |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | − | + | − | +a |

| Precocious puberty | − | + | + | − |

| Dyslipidemia | − | − | − | +b |

| Glucose intolerance | − | + | − | +b |

| Reversal of symptoms with therapy | Unknown | + | + | + |

Abbreviations: N, normal; −, absent; +, present.

Hepatic steatosis in neonatal period noted on ultrasound.

Dyslipidemia and hyperglycemia in neonatal period, diet controlled later.

Our patients are clearly distinct from those with diencephalic syndrome because they presented with clinical features of idiopathic AGL and atypical CGL, such as increased appetite, hepatosplenomegaly, and glucose intolerance in case 1 and severe hypertriglyceridemia and hyperglycemia in case 3. Only case 2 did not have any metabolic derangements. None of our patients had emaciation or euphoria, and all three had prominent musculature on examination (Table 2). Cases 1 and 2 were also atypical to present with central precocious puberty and advanced bone age. Interestingly, all three patients had the onset of lipodystrophy many years (2.5–7.3 y) before the diagnosis of brain tumors. The same histopathology, ie, pilocytic astrocytoma, WHO grade I, in all three patients, and the fact that all of them had reversal of lipodystrophy phenotype after surgical removal and/or chemotherapy for the tumor point to some etiological relationship between generalized lipodystrophy and tumors. All three patients are coincidentally males; however, similar loss of fat should be expected in females with pilocytic astrocytoma.

We hypothesize that the pilocytic astrocytomas induce generalized lipodystrophy in a paraneoplastic fashion either by formation of antiadipocyte autoantibodies that can induce cytotoxicity or by secretion of hormones/cytokines that induce excessive lipolysis from adipocytes; both mechanisms result in loss of adipocytes. Both of the hypotheses are consistent with regain of body weight and fat after reduction of tumor burden. We conclude that the diagnosis of brain tumor should be considered in young children presenting with generalized and severe unexplained loss of sc fat with or without metabolic abnormalities.

Acknowledgments

We thank Claudia Quittner, RN, for her help in the evaluation of case 1.

This work was supported in part by Grants R01-DK54387 and R01-DK105448 from the National Institutes of Health and by the Southwestern Medical Foundation.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Footnotes

- AGL

- acquired generalized lipodystrophy

- CGL

- congenital generalized lipodystrophy

- MRI

- magnetic resonance imaging.

References

- 1. Addy DP, Hudson FP. Diencephalic syndrome of infantile emaciation. Analysis of literature and report of further 3 cases. Arch Dis Child. 1972;47(253):338–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Danziger J, Bloch S. Hypothalamic tumours presenting as the diencephalic syndrome. Clin Radiol. 1974;25(1):153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Burr IM, Slonim AE, Danish RK, Gadoth N, Butler IJ. Diencephalic syndrome revisited. J Pediatr. 1976;88(3):439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fleischman A, Brue C, Poussaint TY, et al. Diencephalic syndrome: a cause of failure to thrive and a model of partial growth hormone resistance. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):e742–e748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Waga S, Shimizu T, Sakakura M. Diencephalic syndrome of emaciation (Russell's syndrome). Surg Neurol. 1982;17(2):141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Salmon MA. Russell's diencephalic syndrome of early childhood. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiat. 1972;35(2):196–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Russell A. A diencephalic syndrome of emaciation in infancy and childhood. British Paediatric Association: proceedings of the twenty-second general meeting. Arch Dis Child. 1951;26(127):274. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shypailo RJ, Butte NF, Ellis KJ. DXA: can it be used as a criterion reference for body fat measurements in children? Obesity. 2008;16(2):457–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fischer P, Möller P, Bindl L, et al. Induction of adipocyte differentiation by a thiazolidinedione in cultured, subepidermal, fibroblast-like cells of an infant with congenital generalized lipodystrophy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(5):2384–2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Poussaint TY, Barnes PD, Nichols K, et al. Diencephalic syndrome: clinical features and imaging findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(8):1499–1505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hoffmann A, Gebhardt U, Sterkenburg AS, Warmuth-Metz M, Müller HL. Diencephalic syndrome in childhood craniopharyngioma–results of German multicenter studies on 485 long-term survivors of childhood craniopharyngioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(11):3972–3977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]