Abstract

Context:

GLIS3 (GLI-similar 3) is a member of the GLI-similar zinc finger protein family encoding for a nuclear protein with 5 C2H2-type zinc finger domains. The protein is expressed early in embryogenesis and plays a critical role as both a repressor and activator of transcription. Human GLIS3 mutations are extremely rare.

Objective:

The purpose of this article was determine the phenotypic presentation of 12 patients with a variety of GLIS3 mutations.

Methods:

GLIS3 gene mutations were sought by PCR amplification and sequence analysis of exons 1 to 11. Clinical information was provided by the referring clinicians and subsequently using a questionnaire circulated to gain further information.

Results:

We report the first case of a patient with a compound heterozygous mutation in GLIS3 who did not present with congenital hypothyroidism. All patients presented with neonatal diabetes with a range of insulin sensitivities. Thyroid disease varied among patients. Hepatic and renal disease was common with liver dysfunction ranging from hepatitis to cirrhosis; cystic dysplasia was the most common renal manifestation. We describe new presenting features in patients with GLIS3 mutations, including craniosynostosis, hiatus hernia, atrial septal defect, splenic cyst, and choanal atresia and confirm further cases with sensorineural deafness and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

Conclusion:

We report new findings within the GLIS3 phenotype, further extending the spectrum of abnormalities associated with GLIS3 mutations and providing novel insights into the role of GLIS3 in human physiological development. All but 2 of the patients within our cohort are still alive, and we describe the first patient to live to adulthood with a GLIS3 mutation, suggesting that even patients with a severe GLIS3 phenotype may have a longer life expectancy than originally described.

Permanent neonatal diabetes (PND) and congenital hypothyroidism can result from a number of genetic mutations. Mutations in KCNJ11 and ABCC8 genes, encoding the Kir6.2 and SUR1 subunits of the pancreatic ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channel involved in regulation of insulin secretion, account for about half of cases of PND (1). Mutations in the INS gene leading to the disruption of insulin synthesis also result in PND (2). Further possible candidate genes for PND include GCK, PDX1, GATA6, NEUROD1, NEUROG3, NKX2-2, IER3IP, PTF1A, HNF1B, RFX6, and MNX. Syndromes that incorporate PND include immunodysregulation polyendocrinopathy enteropathy X-linked syndrome (FOXP3), Wolcott-Rallison syndrome (EIF2AK3), and pancreatic agenesis (PDX1, PTF1A, GATA6, and GATA4) (1, 3). Mutations in TSHR, PAX8, NKX2-1, FOXE1, and NKX2-5 lead to congenital structural thyroid abnormalities, and thyroid dyshormonogenesis derives from mutations in DUOX2, SLC5A5, TG, TPO, and DEHAL1 (4). Mutations in GLIS3 (Gli-similar 3) result in the concomitant presentation of PND and congenital hypothyroidism. GLIS3, a member of the GLI-similar zinc finger protein family encoding for a nuclear protein with 5 C2H2-type zinc finger domains, maps to chromosome 9p24.3-p23 (OMIM 610192) (5). The protein is expressed early in embryogenesis and plays a critical role as both a repressor and activator of transcription (5, 6). It is specifically involved in the development of pancreatic β-cells, the thyroid, eye, liver, and kidney although tissue expression occurs to a lesser extent in the heart, skeletal muscle, stomach, brain, adrenal gland, and bone (7, 8). In 2003, Taha et al (9) described a consanguineous Saudi Arabian family in which 2 of 4 siblings had PND associated with intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), congenital hypothyroidism, facial anomalies, congenital glaucoma, hepatic fibrosis, and polycystic kidneys, described as neonatal diabetes and hypothyroidism (NDH) syndrome (9). A third child from that family consequently died of the same condition (10). Genome-wide linkage analysis and sequencing of candidate genes performed on this family by Senee et al (8) in 2006 identified a homozygous frameshift mutation (c.1873dupC, previously reported as 2067insC) in the GLIS3 gene, which is likely to result in transcript degradation by nonsense mediated decay (6). Both children with this mutation died in infancy. Senee et al (8) described 2 further families with mutations in GLIS3. The first harbored a homozygous 426-kb deletion, which encompassed the SLC1A1 gene and part of GLIS3. The affected offspring in the other family carried a homozygous 149-kb deletion that included a portion of GLIS3 as well; the region common to both deletions mapped to the known start codon of GLIS3. Patients in these 2 families presented a milder phenotype. Variations in the GLIS3 phenotype have been attributed to the tissue-specific expression of variable-length transcripts derived from the 11-exon GLIS3 gene. The absence of pancreatic and thyroid GLIS3 transcripts in the 2 families with deletions resulted in neonatal diabetes and hypothyroidism and the absence of an eye-specific transcript in 1 family resulted in congenital glaucoma. The absence of renal and hepatic abnormalities was attributed to the unaltered expression of liver- and kidney-specific transcripts. More recently, an extended phenotype associated with mutations in GLIS3 has been reported, including skeletal abnormalities and exocrine pancreatic dysfunction (11). Given the rarity of this condition, further information relating genotype to phenotypic manifestation is required.

We describe a case series of 12 patients with mutations in GLIS3, providing additional insight into the clinical features associated with this rare condition.

Subjects and Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki principles with informed parental consent given on behalf of children. Clinical information was provided by the referring clinicians via a neonatal diabetes request form (available at www.diabetesgenes.org), from clinical notes, and subsequently by using a questionnaire circulated to referring clinicians to gain further information.

Genetic analysis

GLIS3 gene mutations were sought by PCR amplification (primer sequences are available on request) and sequence analysis of exons 1 to 11 by comparison with the reference sequence NM_001042413. Exon 1 is noncoding (the 5′ untranslated), and the start codon is located within exon 2.

The effect of coding variants on the protein was investigated in silico using the bioinformatic tool Alamut (Interactive Biosoftware). When PCR amplification failed, suggesting a homozygous deletion, parental samples were investigated by real-time quantitative PCR on an ABI 7900 system (TaqMan assay with SYBR Green detection), and the copy number of exons 1 to 11 was determined by the 2−ΔΔCt method.

Patients 1 and 10 were analyzed for all of the known neonatal diabetes genes using a targeted next-generation assay (12). Mutations identified by this assay were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Results

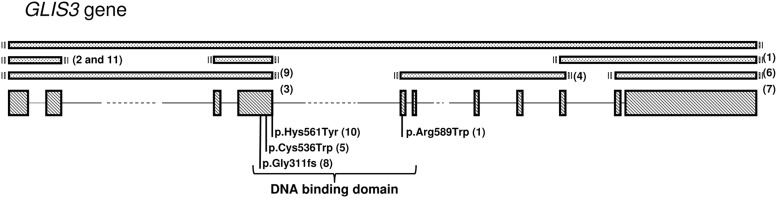

Table 1 describes the nucleotide and predicted protein changes of the GLIS3 mutations identified in our case series. Deletions of ≥1 of the 11 exons of GLIS3 were observed in most patients. Patients 1, 5, and 10 harbor missense mutations (p.Arg589Trp, p.Cys536Trp, and p.His561Tyr, respectively), affecting highly conserved amino acids located in the DNA binding domain and so are likely to be pathogenic, thus severely affecting the function of the GLIS3 protein. Patient 1 is the first patient reported to be a compound heterozygote for 2 mutations in GLIS3 (a deletion and a missense mutation). Patients 3a and 3b are siblings. Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of GLIS3, showing the mutations described in our patient population.

Table 1.

Mutations and Nucleotide Changes Relating to Mutations in GLIS3

| Patient No. | Exon | Mutation | Nucleotide Change | Previously Published | In Silico Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | p.Arg589Trp/exons 1–11 del | c.1765C>T/c.-?_2793+?del | No | Pathogenic/pathogenic |

| 2 | 1–2 | Exons 1–2 del/exons 1–2 del | c.-?_388+?del/c.-?_388+?del | Yes7 | Pathogenic |

| 3a | 1–4 | Exons 1–4 del/exons 1–4 del | c.-?_1710+?del/c.-?_1710+?del | Yes7 | Pathogenic |

| 3b | 1–4 | Exons 1–4 del/exons 1–4 del | c.-?_1710+?del/c.-?_1710+?del | No | Pathogenic |

| 4 | 5–9 | Exons 5–9 del/exons 5–9 del | c.1711-?_2473+?del/c.1711-?_2473+?del | Yes6 | Pathogenic |

| 5 | 4 | p.Cys536Trp/Cys536Trp | c.1608C>G/c.1608C>G | Yes6 | Pathogenic |

| 6 | 9–11 | Exons 9–11 del/exons 9–11 del | c.2298-?_2657+?del/c.2298-?_2657+?del | No | Pathogenic |

| 7 | 10–11 | Exons 10–11 del/exons 10–11 del | c.2474-?_2793+?del/c.2474-?_2793+?del | No | Pathogenic |

| 8 | 4 | p.Gly311Alafs/p.Gly311Alafs | c.932delG/c.932delG | No | Pathogenic |

| 9 | 3–4 | Exons 3–4 del/exons 3–4 del | c.389-?_c.1710+?del/c.389-?_c.1710+?del | No | Pathogenic |

| 10 | 4 | p.His561Tyr/p.His561Tyr | c.1681C>T/c.1681C>T | No | Pathogenic |

| 11 | 1–2 | Exons 1–2 del/exons 1–2 del | c.-?_388+?del/c.-?_388+?del | No | Pathogenic |

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the GLIS3 gene. The diagonal boxes represent the exons. The bracket indicates the region encoding the zinc-finger DNA binding domain. Mutation positions are indicated under the gene. Deletions are represented as dotted boxes. The patient number for each mutation/deletion is indicated in parentheses.

The clinical features of all of the patients are summarized in Table 2. All but 2 of the patients in our case series remain alive to date, and patient 1 is the first patient with a GLIS3 mutation to survive into adulthood (aged 36 years). Patient 6 died from liver failure with marked portal hypertension and esophageal variceal bleeding, and patient 9 died of overwhelming measles sepsis and multiorgan failure at 6 months of age. Nine patients in our cohort were born to parents who were first cousins. Patient 3, who was born to apparently not related parents was described previously by Dimitri et al (11). In this case series, we describe another child with a GLIS3 mutation born to Caucasian parents who are not related (patient 1) and the sibling of patient 3a (patient 3b). A homozygous deletion was confirmed in patient 6; however, consanguinity was denied by the patient's parents.

Table 2.

Clinical Features Presenting in Patients With GLIS3 Mutations

| Patient No. | Exon | Birth Weight, g | IUGRa | Gestation, wk | Ethnicity | Sex | Consanguineous | Age of Onset of PNDb | Congenital Hypothyroidism | Liver Disease | Kidney Disease | Exocrine Pancreatic Disease | Congenital Glaucoma | Skeletal Disease | Developmental Delay | Facial Dysmorphism | Other Features | Alive | Current Age, y |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 2750 | No | 39 | Caucasian | Female | No | 30 h | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Choanal atresia, hiatus hernia | Yes | 36 y |

| 2 | 1–2 | 1170 | Yes | 35 | Bangladeshi | Female | Yes | 3 d | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 6.3 y |

| 3a | 1–4 | 1430 | Yes | 35 | Caucasian | Male | No | 4 d | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Bilateral sensorineural deafness, PDA, pancreatic cyst | Yes | 6.02 y |

| 3b | 1–4 | 2020 | Yes | 38 | Caucasian | Male | No | 2 d | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Pancreatic cysts, splenic cyst, bilateral sensorineural deafness | Yes | 20 mo |

| 4 | 5–9 | 1750 | Yes | 34 | Arab | Female | Yes | 2 d | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4.7 y |

| 5 | 4 | 2050 | Yes | 39 | Arab | Male | Yes | 5 d | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | 6.8 y |

| 6 | 9–11 | 1530 | Yes | 37 | African-American | Female | Unknown | 7 d | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | 6.0 y |

| 7 | 10–11 | 1235 | Yes | 36 | Yemeni | Female | Yes | 3 d | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3 y |

| 8 | 4 | 1860 | Yes | 39 | Pakistani | Female | Yes | 24 h | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Right sensorineural deafness | Yes | 2.5 y |

| 9 | 3–4 | 1520 | No | 30 | Turkish | Male | Yes | 21 d | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No, died at 6 mo of age | NA |

| 10 | 4 | 973 | Yes | 31 | Kurdish | Male | Yes | 31 d | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Patent ductus arteriosus | Yes | 4.5 y |

| 11 | 1–2 | 1730 | Yes | 39 | Arab | Male | Yes | 19 d | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Ostium secundum ASD | Yes | 7 mo |

Abbreviations: ASD, atrial septal defect; NA, not applicable; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus.

Birth weight <10th centile for gestational age.

Permanent neonatal diabetes.

PND was the only consistent feature of all of our patients with GLIS3 mutations. Age at diagnosis ranged from birth to 23 days. All patients were insulin treated. Patients were initially treated with insulin at 0.4 to 2.0 U/kg/24 h (patient 4 required 2.0 U/kg/24 h), demonstrating a range of insulin sensitivities. Patient 11 had high insulin sensitivity, leading to recurrent hypoglycemic episodes with very small doses of insulin. Others had labile blood glucose (patients 3a and 3b), and one patient clinically demonstrates insulin resistance, particularly during periods of illness (patient 2). In the first year of life, this patient required 0.5 to 0.7 U/kg of insulin per day. However, during times of intercurrent illness, doses of insulin at 3 to 4 times her normal requirement were required to achieve normoglycemia. Despite erratic blood glucose control with periods of insulin resistance, her glycosylated hemoglobin at 1 year of age was 7.8% (62.0 mmol/mol).

Apart from patient 1, all patients had with congenital hypothyroidism. This is a cardinal feature of the NDH syndrome described previously in all patients with GLIS3 mutations(8, 9). Although congenital hypothyroidism presented during the first week of life in all patients, the patterns of thyroid disease were variable. Patients 2, 3a, and 3b had elevated TSH levels that were resistant to treatment with thyroxine as described previously (11). Similarly, patients 7 and 11 had very high TSH levels that did not reduce to normal limits with levothyroxine therapy despite normalizing of free T4. In these 3 patients, the thyroid anatomy was normal on ultrasonography. In contrast, patient 4 presented with congenital hypothyroidism due to athyreosis and responded to levothyroxine at a starting dose of 28 μg/kg/d. In patients 5 and 8, thyroid ultrasonography was not performed. However, their initial levothyroxine requirements were 24 and 15 μg/kg/d, respectively. Patient 8 had fluctuating levels of TSH (20–30 mIU/L) in the first year of life despite normal levels of free T4, which have since normalized. Patients 6 and 10 had normal thyroid anatomy on ultrasonography, and in comparison with other patients with GLIS3 mutations, TSH responded appropriately to conventional doses of levothyroxine with an appropriate increase in the levothyroxine dose with age. Notably, the postmortem examination of the thyroid gland in patient 6 demonstrated a paucity of colloid as well as extensive perifollicular and interstitial fibrosis, explaining the need for thyroxine despite apparently normal thyroid anatomy on ultrasonography.

Liver disease was documented in 7 of our 12 patients. The hepatic dysfunction presented concomitantly with renal abnormalities and ranged from hepatitis (patients 3b and 4) to hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis (patients 2, 3a, 6, 7, 9, and 10). Nine patients have anatomical kidney changes. Of these, 7 children showed variable renal cystic dysplasia ranging from an isolated cyst observed in patient 10 and bilateral calyceal calcification in patient 11 to extensive cystic renal dysplasia (patients 2, 3a, 3b, 4, and 9) (Figure 2). Patient 7 lacks renal corticomedullary differentiation, and renal ultrasonography in patient 6 demonstrated bilateral renal enlargement with no cystic changes.

Figure 2.

Extensive renal cystic dysplasia in patient 2 with a mutation in GLIS3 at 5 months of age.

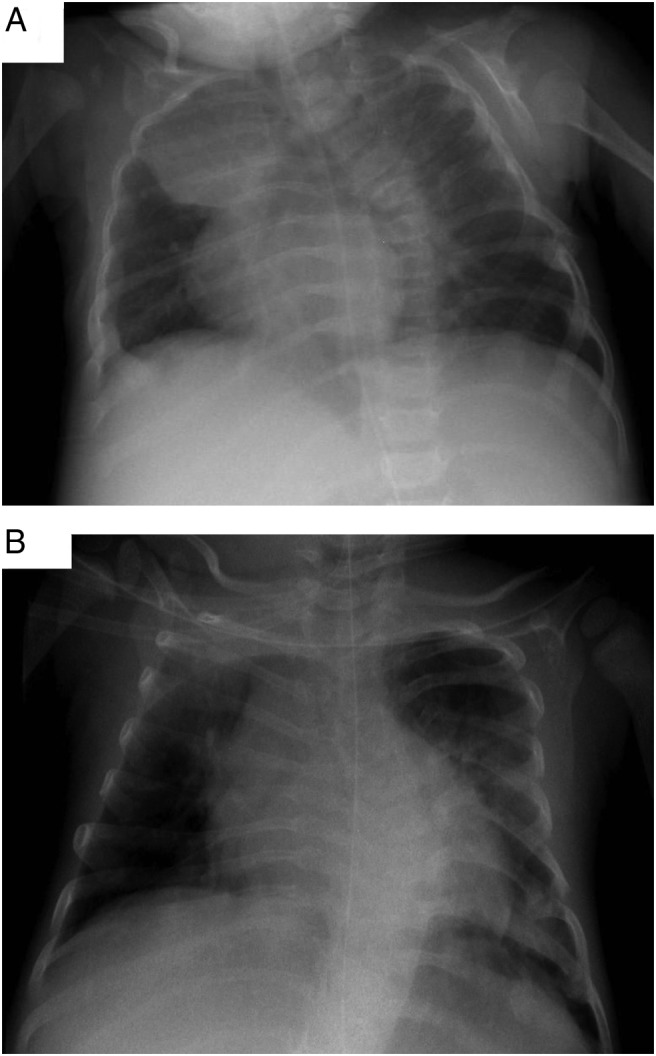

Patient 2 was the first patient to be described with skeletal manifestations due to a mutation in GLIS3. She presented with osteopenia, significantly delayed rib fracture healing, and a marked thoracolumbar scoliosis (Figure 3, A and B). At 4 months of age, the PTH level was 62.6 ng/L (11–35 ng/L) with a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level of 34.6 nmol/L (50–90 nmol/L). Serum calcium and phosphate and bone alkaline phosphatase concentrations measured 2.56 mmol/L (2.13–2.72 mmol/L), 2.27 mmol/L (1.10–2.40 mmol/L), and 297.3 mmol/L (9–28 mmol/L), respectively. Despite normalization of the PTH and vitamin D levels after treatment with ergocalciferol and calcium, the patient sustained a further rib fracture on the left side (11). Patient 5 was also reported to have skeletal abnormalities with prominent right sixth and seventh ribs but normal bone biochemistry. Patient 6 is the first patient with a mutation in GLIS3 to have sagittal craniosynostosis requiring surgical intervention. This patient initially manifested with mild hypocalcemia in the second month of life (7.8 mg/dL; normal range, 8.7–10.1 mg/dL), which subsequently normalized without treatment. Patient 8 was osteopenic by 6 months and despite vitamin D supplementation, her 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 level was 33.5 nmol/L at 6 weeks of age. Adjusted serum calcium in this patient was 2.0 mmol/L in the first week of life and subsequently normalized to 2.5 mmol/L by 12 days of age without calcium replacement. Alkaline phosphatase peaked at 3 months to 2100 U/L but had normalized by 2 years of age. No fractures were identified in patient 8.

Figure 3.

A, Anteroposterior chest x-ray of patient 2 performed on day 101 demonstrating thoracolumbar scoliosis and left rib fractures located on ribs 7, 8, and 9. B, Anteroposterior chest x-rays performed on day 412 demonstrating worsening thoracolumbar scoliosis and persistence of callus formation in left ribs 7, 8 and 9 with a new fracture at left rib 6.

Malabsorption due to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency as demonstrated by low fecal elastase was a feature in patients 2, 3a, 3b, and 7 in our case series. These 4 patients have been treated with pancreatic enzyme supplementation. We report the first patient with a GLIS3 mutation to present with a splenic cyst (patient 3b).

Developmental delay and IUGR were common features in our patient cohort. Only 4 of 12 of our patients had congenital glaucoma although there was no clear relationship between the ocular presentation and the GLIS3 exon affected as suggested by Senee et al (8).

Congenital cardiac defects in patients with GLIS3 mutations have not been described previously. Patient 11 had an ostium secundum defect. It is likely that the patent ductus arteriosus observed in patients 3a and 10 was due to prematurity rather than to an abnormality in GLIS3 function. Patient 1 is the first patient with a GLIS3 mutation to present with choanal atresia. Before this study, only 1 patient had been described with sensorineural deafness (patient 3a) and a deletion of exons 1 to 4 of GLIS3 (11). Patient 3b (sibling of patient 3a) also presented with bilateral sensorineural deafness; we now report a second patient of Pakistani origin (patient 8) with a frameshift mutation in exon 4 of GLIS3 who had sensorineural deafness. Of the patients who presented with dysmorphic features, consistent features included low-set ears, epicanthic folds, a flat nasal bridge, and a long philtrum with a thin upper lip.

Discussion

The variability in phenotype observed between our patients and others (8) has been attributed to the differential expression of multiple GLIS3 transcripts. Two major transcripts, 7.5 kb and smaller (0.8–2.0 kb), have been described previously; the 7.5-kb transcript is strongly expressed in pancreas, thyroid, and kidney with smaller transcripts predominantly expressed in liver, kidney, heart, and skeletal muscle (8). Thus, mutations in GLIS3 have the potential to cause widespread disruption. Previously described severely affected individuals with mutations in GLIS3 appear to have total loss of function of the gene (8). For severely affected patients with deletions, it is likely that the mutated transcripts undergo nonsense-mediated decay and little or no protein is produced. Patient 1 is the first patient described with biallelic GLIS3 mutations, who does not have congenital hypothyroidism, and she has a milder phenotype than other patients in the cohort. She is a compound heterozygote for a whole-gene deletion and a missense mutation in exon 5 (p.Arg589Trp). We thus speculate that the missense mutation may be a hypomorphic change resulting in a mutated protein possessing some residual function.

The cardinal feature in all our patients was the diagnosis of neonatal diabetes in the first weeks of life, and the concomitant presence of IUGR may reflect significant intrauterine insulin deficiency. GLIS3 plays a key role in pancreatic development, particularly in the embryogenesis of β-cells, which explains why our patients and others with GLIS3 mutations to date have presented with PND (11). GLIS3 interacts with key regulatory genes in pancreatic embryogenesis including ONECUT1 and NEUROGENIN3 (NEUROG3) (13–15). GLIS3 expression also persists beyond the embryonic period, promoting β-cell proliferation and regulating insulin gene expression through binding to GLI-RE on the INS gene (16). Therefore, the variation in insulin sensitivities among patients (and mutations) may relate to the impact of the mutation on the nuclear localization, GLI-binding element activity, transactivation, pancreatic development, subsequent β-cell proliferation, and remnant endogenous insulin production. In humans, GLIS3 has been identified as a susceptibility locus for the risk of type 1 and 2 diabetes (17, 18). The significant insulin requirements observed during periods of illness in our more severely affected patients may also suggest a possible role of GLIS3 on the end-organ response to insulin, possibly at the level of the insulin receptor. However, a large difference in insulin sensitivities was observed in patients with the same mutation in our cohort (patients 2 and 11). This finding suggests that other genetic factors might influence the insulin response in these patients. Initially, the abnormalities in the pancreas in patients with GLIS3 mutations were thought to be limited to β-cells. However, GLIS3 transcripts are highly expressed not only in pancreatic β-cells but also to a lesser degree in pancreatic acini. The presence of exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in patients 2, 3a, 3b, and 7 in our series suggests that exocrine pancreatic involvement may be more extensive than previously described (8). The presence of pancreatic cystic changes in patients 3a and 3b supports the previous observations that GLIS3 is important in the development and maintenance of pancreatic ducts (15).

The spectrum of structural thyroid abnormalities including athyreosis, glandular hypoplasia, and normal thyroid anatomy with lack of normalization of TSH after therapy with thyroxine in infancy demonstrates a broad range of thyroid dysfunction resulting from mutations within the same gene. A recent postmortem examination in patient 6 demonstrated a paucity of colloid as well as extensive perifollicular and interstitial fibrosis despite initially normal thyroid ultrasonography. No explanation for this variation has been offered to date although a similar phenotypic variability is also observed in patients with mutations in PAX8 and NKX2-1 (TTF1/NK2 homeobox-1 or thyroid transcription factor 1), involved in thyroid cell differentiation and proliferation and subsequent expression of genes encoding for thyroglobulin, thyroid peroxidase, thyrotropin receptor, and the sodium-iodide symporter (19–21). However, despite these phenotypic similarities, there is no evidence for conserved GLI transcription binding sites in the PAX8, NKX2-1, or TSHR flanking gene sequences. Further in vitro work is required to determine whether GLIS3 works upstream of genes in pathways regulating thyroid development, hormonogenesis, and the end organ response to T4. The failure of suppression of TSH after thyroxine supplementation in some patients suggests an additional thyroid hormone resistance. Further work is required to understand the role of GLIS3 in thyroid hormone activity.

As described previously in patients with GLIS3 mutations (8), most of our patients presented renal parenchymal disease, primarily renal cystic dysplasia. However, some patients with mutations in GLIS3 did not develop renal disease. Whereas the variation in renal manifestations may be mutation related, out of 3 related patients with a homozygous insertion (2067insC) leading to a frameshift and likely degradation of the transcript reported by Senee et al (8), only 2 had renal cystic dysplasia. Similarly, the manifestations of hepatic disease varied among patients. GLIS3 contains 29 known putative transcription start sites across the 11-exon gene, resulting in variable length transcripts. Larger (7.5 kb) and smaller (0.8–2.0 kb) transcripts are expressed in the kidney and smaller (0.8–2.0 kb) transcripts are expressed in the liver (8). The variable presentation of hepatic and renal disease therefore may be related to the relative qualitative and quantitative expression of tissue transcripts and the encoded proteins in individual patients or alternatively to the variation in the expression of regulatory transcripts.

Most patients described to date with GLIS3 mutations also present dysmorphic features (8). In our cohort, dysmorphic features were seen in 9 of the 12 patients. GLIS3 is expressed during embryonic face development, which may help in part to explain the dysmorphic facial features observed in these patients (5). Congenital glaucoma was observed in patients 6, 7, 10, and 11 in our cohort. In mouse models, Glis3 is expressed in a dynamic pattern during eye development, initially in the dorsal optic vesicle and subsequently in the lens and the retina, which supports the presentation of glaucoma in our patients and previous patients with GLIS3 mutations (5). However, from our cohort we were unable to ascribe a specific exon relating to the eye disease.

Skeletal manifestations were first described in 2011 (11) in a patient with a GLIS3 mutation presenting multiple rib fractures with persistence of callus formation and scoliosis associated with a deletion in exons 1 to 2. The persistence of callus formation suggests a defect in bone remodeling either due to dysfunctional osteoblast signaling to osteoclasts or reduced osteoclastic bone reabsorption. Milder skeletal abnormalities (prominence of the left ribs) were observed in patient 5 (Table 1), who carries a missense mutation in GLIS3, and osteopenia in patient 7, who also has a missense mutation in exon 4. Patient 6 presented with craniosynostosis, which is a novel presentation in the GLIS3 phenotype. Recent evidence suggests a role of GLIS3 in osteoblast differentiation by the up-regulation of fibroblast growth factor 18 (FGF18) (7, 22). A reduction in or absence of FGF18 results in delayed bone mineralization due to diminished osteoblast terminal differentiation and proliferation. The expression of GLIS3 and WW domain containing transcription regulator 1 (WWTR1) overlaps in the kidney, and mutations in both genes result in renal cystic dysplasia with a high glomerular cystic load (23, 24). Similarly, WWTR1 and GLIS3 have a stimulatory role in osteogenesis while inhibiting adipogenesis (7). WWTR1 interacts with GLIS3 to enhance its transcriptional activity by acting as a coactivator. The C terminus of GLIS3 is fundamental for this action (24). Thus, GLIS3 mutations that affect the C-terminal domain abolish the interaction between these genes, which may in part explain the concomitant renal and skeletal manifestations seen in human GLIS3 mutations.

We previously reported the first patient with a GLIS3 mutation to present with sensorineural deafness (patient 3a) (11). We now report this finding in the sibling of patient 3a (patient 3b) and in another unrelated child (patient 8) with a frameshift mutation at exon 4. This mutation will introduce a premature stop codon, and the subsequent transcript will be degraded in a similar way to deletions in GLIS3. Because this mutation functionally has an effect to similar to that of deletions, we are unable to associate the hearing defect with a specific exon although exon 4 is affected in all 3 patients. For patients severely affected by GLIS3 mutations, developmental delay and learning difficulties are common features. GLIS3 is known to be expressed in brain tissue during embryogenesis, but there is little evidence to date connecting GLIS3 with brain development. Only 1 study to date, using genome-wide association studies of cerebrospinal fluid tau levels to identify risk variants for Alzheimer disease, has identified GLIS3 as a significant locus for the development of Alzheimer disease (25). Further work in this area is required to understand how GLIS3 may alter cerebral embryogenesis and maturation.

In one of our families (patient 2) and in a family reported by Senee et al (8), the deletion also encompassed the gene encoding the neuronal/epithelial high-affinity glutamate transporter SLC1A1 (solute carrier family 1). SLC1A1 is principally expressed in neurons, kidney, and small intestine. Mutations in SLC1A1 are thought to cause dicarboxylic aminoaciduria (26) and have been associated with psychiatric disorders including psychosis, obsessive compulsive disorder, and neuronal degeneration (27, 28).

We have presented an extended spectrum of clinical features in relation to patients with mutations in the GLIS3 gene. Our current study has focused on the clinical manifestations of patients with these mutations, and further in vitro work is required to test the GLIS3 missense variants functionally in biological models.

In summary, patients presenting with mutations in GLIS3 characteristically present with neonatal diabetes with variable insulin sensitivity and congenital hypothyroidism due to a range of underlying causes. Although mutations in GLIS3 are more common in consanguineous pedigrees, we report 2 patients from apparently unrelated parents with GLIS3 mutations. We also report the first patient with compound heterozygous mutations in GLIS3 with preservation of thyroid function, who is also the first patient reported with a GLIS3 mutation to survive into adulthood. Hepatic and renal disease is common in the patients in our cohort, but the presentation is variable. We report new findings within the GLIS3 phenotype including cardiac disease, hiatus hernia, sagittal craniosynostosis, splenic cystic change, and choanal atresia, further extending the spectrum of abnormalities associated with GLIS3 mutations and providing novel insights into the role of GLIS3 in human physiological development. We report further patients presenting with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and sensorineural deafness. All but 2 of the patients in our cohort are still alive, suggesting that even patients with a severe GLIS3 phenotype may have a longer life expectancy than originally described.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust. A.T.H. and S.E. are Wellcome Trust Senior Investigators and A.T.H. is an National Institute for Health Research Senior Investigator. The views expressed are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- FGF18

- fibroblast growth factor

- IUGR

- intrauterine growth retardation

- NDH

- neonatal diabetes and hypothyroidism

- PND

- permanent neonatal diabetes

- WWTR1

- WW domain containing transcription regulator 1.

References

- 1. Polak M, Cave H. Neonatal diabetes mellitus: a disease linked to multiple mechanisms. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Edghill EL, Flanagan SE, Patch AM, et al. Insulin mutation screening in 1,044 patients with diabetes: mutations in the INS gene are a common cause of neonatal diabetes but a rare cause of diabetes diagnosed in childhood or adulthood. Diabetes. 2008;57:1034–1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Franco E, Flanagan SE, Houghton JAL, Lano-Allen H, Mackay DJG, Temple IK, et al. Genomic testing in neonatal diabetes: a new paradigm. Lancet. In press. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Szinnai G. Clinical genetics of congenital hypothyroidism. Endocr Dev. 2014;26:60–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim YS, Nakanishi G, Lewandoski M, Jetten AM. GLIS3, a novel member of the GLIS subfamily of Krüppel-like zinc finger proteins with repressor and activation functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:5513–5525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Beak JY, Kang HS, Kim YS, Jetten AM. Functional analysis of the zinc finger and activation domains of Glis3 and mutant Glis3 (NDH1). Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;3:1690–1702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beak JY, Kang HS, Kim YS, Jetten AM. Krüppel-like zinc finger protein Glis3 promotes osteoblast differentiation by regulating FGF18 expression. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1234–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Senée V, Chelala C, Duchatelet S, et al. Mutations in GLIS3 are responsible for a rare syndrome with neonatal diabetes mellitus and congenital hypothyroidism. Nat Genet. 2006;38:682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taha D, Barbar M, Kanaan H, Williamson Balfe J. Neonatal diabetes mellitus, congenital hypothyroidism, hepatic fibrosis, polycystic kidneys, and congenital glaucoma: a new autosomal recessive syndrome? Am J Med Genet A. 2003;122A:269–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Habeb AM, Al-Magamsi MS, Eid IM, et al. Incidence, genetics, and clinical phenotype of permanent neonatal diabetes mellitus in northwest Saudi Arabia. Pediatr Diabetes. 2012;13:499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dimitri P, Warner JT, Minton JA, et al. Novel GLIS3 mutations demonstrate an extended multisystem phenotype. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164:437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ellard S, Lango Allen H, De Franco E, et al. Improved genetic testing for monogenic diabetes using targeted next-generation sequencing. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1958–1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kim YS, Kang HS, Takeda Y, et al. Glis3 regulates neurogenin 3 expression in pancreatic β-cells and interacts with its activator, Hnf6. Mol Cells. 2012;34:193–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Poll AV, Pierreux CE, Lokmane L, et al. A vHNF1/TCF2-HNF6 cascade regulates the transcription factor network that controls generation of pancreatic precursor cells. Diabetes. 2006;55:61–69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kang HS, Kim YS, ZeRuth G, et al. Transcription factor Glis3, a novel critical player in the regulation of pancreatic β-cell development and insulin gene expression. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:6366–6379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yang Y, Chang BH, Chan L. Sustained expression of the transcription factor GLIS3 is required for normal β cell function in adults. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5:92–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Santin I, Eizirik DL. Candidate genes for type 1 diabetes modulate pancreatic islet inflammation and β-cell apoptosis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15(suppl 3):71–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cho YS, Chen CH, Hu C, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies eight new loci for type 2 diabetes in east Asians. Nat Genet. 2012;44:67–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Macchia PE, Lapi P, Krude H, et al. PAX8 mutations associated with congenital hypothyroidism caused by thyroid dysgenesis. Nat Genet. 1998;19:83–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Sanctis L, Corrias A, Romagnolo D, et al. Familial PAX8 small deletion (c.989_992delACCC) associated with extreme phenotype variability. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5669–5674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Carré A, Szinnai G, Castanet M, et al. Five new TTF1/NKX2.1 mutations in brain-lung-thyroid syndrome: rescue by PAX8 synergism in one case. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2266–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Liu Z, Xu J, Colvin JS, Ornitz DM. Coordination of chondrogenesis and osteogenesis by fibroblast growth factor 18. Genes Dev. 2002;16:859–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hashimoto H, Miyamoto R, Watanabe N, et al. Polycystic kidney disease in the medaka (Oryzias latipes) pc mutant caused by a mutation in the Gli-Similar3 (glis3) gene. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kang HS, Beak JY, Kim YS, Herbert R, Jetten AM. Glis3 is associated with primary cilia and Wwtr1/TAZ and implicated in polycystic kidney disease. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:2556–2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cruchaga C, Kauwe JS, Harari O, et al. GWAS of cerebrospinal fluid tau levels identifies risk variants for Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 2013;78:256–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bailey CG, Ryan RM, Thoeng AD, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in the glutamate transporter SLC1A1 cause human dicarboxylic aminoaciduria. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:446–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Arnold PD, Sicard T, Burroughs E, Richter MA, Kennedy JL. Glutamate transporter gene SLC1A1 associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:769–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Myles-Worsley M, Tiobech J, Browning SR, et al. Deletion at the SLC1A1 glutamate transporter gene co-segregates with schizophrenia and bipolar schizoaffective disorder in a 5-generation family. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2013;162B:87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]