Abstract

Background:

Nurse prescribing is a practice that has evolved and will continue to evolve in response to emerging trends, particularly in primary care. The goal of this study was to describe the trends and patterns in medication prescription to adults 65 years of age or older in Ontario by nurse practitioners over a 10-year period.

Methods:

We conducted a population-based descriptive retrospective cohort study. All nurse practitioners registered in the Corporate Provider Database between Jan. 1, 2000, and Dec. 31, 2010, were identified. We identified actively prescribing nurse practitioners through linkage of dispensed medications to people aged 65 years or older from the Ontario Drug Benefit database. For comparison, all prescription medications dispensed by family physicians to a similar group were identified. Geographic location was determined based on site of nurse practitioner practice.

Results:

The number and proportion of actively prescribing nurse practitioners prescribing to older adults increased during the study period, from 44/340 (12.9%) to 888/1423 (62.4%). The number and proportion of medications dispensed for chronic conditions by nurse practitioners increased: in 2010, 9 of the 10 top medications dispensed were for chronic conditions. There was substantial variation in the proportion of nurse practitioners dispensing medication to older adults across provincial Local Health Integration Networks.

Interpretation:

Prescribing by nurse practitioners to older adults, particularly of medications related to chronic conditions, increased between 2000 and 2010. The integration of nurse practitioners into primary care has not been consistent across the province and has not occurred in relation to population changes and perhaps population needs.

Nurse prescribing is a health care practice that has evolved and will continue to evolve in response to emerging changes to the health care system and concerns about access, costs and quality. The number of countries in which nurses legally prescribe medication is growing and is expected to increase.1,2 Although the defining criteria for prescribing practices by nurses vary, 2 models are generally described.1 The first model is the independent nurse prescriber, in which the nurse is responsible for the clinical assessment, diagnosis and medical treatment within a regulated scope of practice. Independent nurse prescribers can prescribe from a limited formulary containing a list of medications or from an open formulary, with or without restriction of selected classes of medications, depending on the jurisdiction within which the individual practises. The second model is supplementary nurse prescribing, in which the nurse in partnership with an independent prescriber (i.e., physician), after initial assessment and diagnosis, may prescribe medication, usually from a limited formulary. Our knowledge of the patterns and impact of nurse prescribing is limited but growing.3-5 Studies examining nurse prescribing have tended to be disease specific6-10 and have used a variety of non-population-based research designs. Findings from these limited studies generally support nurse prescribing as an effective health care practice.

This study focuses on independent nurse practitioners. In the province of Ontario, nurse practitioners are registered nurses with additional clinical, including pharmacological, education who collaborate with physicians and other health care providers in the provision of care and are able to assess, order diagnostic tests, diagnose, prescribe medication and manage patient health conditions within their legal scope of practice.11 The role of the nurse practitioner in primary practice has evolved predominantly in response to the needs of the populations served and directions established by the provincial and territorial ministries.4,12 In December 2009, Bill 179, the Regulated Health Professions Statute Law Amendment Act, was passed in Ontario amending 26 health statutes, including the Nursing Act, 1991, and the Regulated Health Professionals Act, 1991. New authorizations allowed nurse practitioners to broadly prescribe medications based on their knowledge, competencies and practice setting. This specific regulatory change, which became effective Oct. 1, 2011, eliminated the previous allowable list of drugs (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/3/3/E299/suppl/DC1).

The objective of this study was to describe nurse practitioners' patterns of prescribing to adults 65 years of age or older in Ontario over a 10-year period preceding the recent change in prescriptive practice and to provide a platform for ongoing evaluation of nurse practitioners' contribution to primary health care, specifically, prescribing patterns before and leading up to the 2011 regulatory change.

Methods

Study design and data sources

We conducted a population-based, retrospective cohort study to examine the prescribing patterns of nurse practitioners providing care to older adults between 2000 and 2010. We used 4 administrative health databases: the Corporate Provider Database, which is derived from the list of health care professionals registered with each respective licensing college, for demographic and practice information for all nurse practitioners and physicians with an Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) billing number; the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences Physician Database to identify family physicians and link the physician's encrypted unique identifier to prescriptions dispensed to older adults (≥ 65 years) covered under Ontario's Drug Benefit program; the Ontario Drug Benefit database for detailed information on all outpatient prescriptions covered by the provincial drug formulary; and the Registered Persons Database for basic demographic information for all residents who had ever received an Ontario health card number. These databases are held securely in a linked, de-identified form at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences in Toronto and were examined at a satellite unit located at Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario.

Study cohorts

We identified all nurse practitioners who were registered between Jan. 1, 2000, and Dec. 31, 2010, and had an OHIP billing number in the Corporate Provider database. Medications prescribed by nurse practitioners in Ontario were, historically, outlined in a list of drugs found in Regulation 275/94 of the Nursing Act, 1991. In 2008, the list was amended to add 24 additional drugs. We determined a nurse practitioner's eligibility to prescribe in a given year using OHIP eligibility start and end dates. We identified the health region (Local Health Integration Network) where the nurse practitioner practised each year using the postal code of his or her practice site at the start of each year. To account for the influence of changes in population demographics over time, as well as changes in drug availability, marketing and formulary coverage during the study period, we identified a cohort of family physicians using a similar approach.

Prescription medications

We identified all medications in the Ontario Drug Benefit database prescribed by a member of the nurse practitioner or family physician cohort and dispensed to older adults during the study period. The patient's age at dispensation date was obtained through record linkage with the Registered Persons Database. As such, only patients 65 years or older and only prescriptions with a valid Ontario health care number were included in the analysis. We categorized drugs on the basis of their pharmacologic and therapeutic class, as well as whether they were indicated for an acute (i.e., episodic treatment) or chronic (i.e., chronic treatment) condition. The categorization of drugs used for both acute and chronic conditions (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) was based on the proportion of prescriptions written for a short (< 30 d) versus long (≥ 30 d) duration of use. With this approach, acetaminophen, NSAIDs, proton pump inhibitors and stool softeners were categorized as chronic medications in this older population, since the majority of prescriptions were for 30 days or longer.

Statistical analysis

The nurse practitioner cohort was described with respect to the number of nurse practitioners newly registered each year, age at registration and the proportion who had at least 1 prescription filled by a patient 65 years or older within their first year of practice (an indicator of "active" prescribing). To examine geographic variation in the prevalence of prescribing to older adults over time, we identified the number of nurse practitioners per 10 000 residents who had at least 1 prescription filled each year by a patient 65 years of age or older within each of Ontario's 14 health regions. As well, to assess whether changes in the prevalence of nurse-practitioner prescribers were due to changes in population demographics, we compared the change in the proportion of older adults living within each health region during the study period to that of nurse practitioners prescribing to older adults within the same health region. The proportions of medications prescribed and dispensed each year to older adults for each therapeutic class were identified and ranked according to their frequency of use. All analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc.).

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Health Services Research Ethics Board at Queen's University, Kingston, Ont.

Results

Over the 10-year study period, the number of nurse practitioners registered and the proportion who had prescribed a medication to patients 65 years or older increased (Table 1). In 2000, 44 (12.9%) of 340 registered nurse practitioners actively prescribed to older adults within their first year of licensure, as compared with 888 (62.4%) of 1423 eligible nurse practitioners in 2010.

Table 1: Characteristics of nurse practitioners registered in Ontario between 2000 and 2010.

| Year | No. newly registered | Age at registration, yr, mean ± SD | Age range, yr | Total no. registered | No. (%) with ≥ 1 prescription dispensed to older adults* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 65 | 40.3 ± 6.5 | 26-58 | 340 | 44 | (12.9) |

| 2001 | 50 | 40.9 ± 7.6 | 27-60 | 389 | 71 | (18.2) |

| 2002 | 40 | 41.1 ± 7.0 | 27-55 | 429 | 79 | (18.4) |

| 2003 | 87 | 40.7 ± 7.4 | 27-56 | 516 | 89 | (17.2) |

| 2004 | 56 | 41.0 ± 7.6 | 28-59 | 572 | 119 | (20.8) |

| 2005 | 55 | 39.9 ± 7.8 | 27-55 | 627 | 192 | (30.6) |

| 2006 | 75 | 39.0 ± 8.0 | 26-57 | 702 | 275 | (39.2) |

| 2007 | 162 | 40.0 ± 9.0 | 26-64 | 863 | 399 | (46.2) |

| 2008 | 156 | 39.6 ± 8.3 | 25-59 | 1019 | 536 | (52.6) |

| 2009 | 234 | 40.0 ± 8.8 | 25-63 | 1252 | 694 | (55.4) |

| 2010 | 171 | 38.6 ± 9.4 | 26-61 | 1423 | 888 | (62.4) |

Note: SD = standard deviation. *People aged 65 years or older.

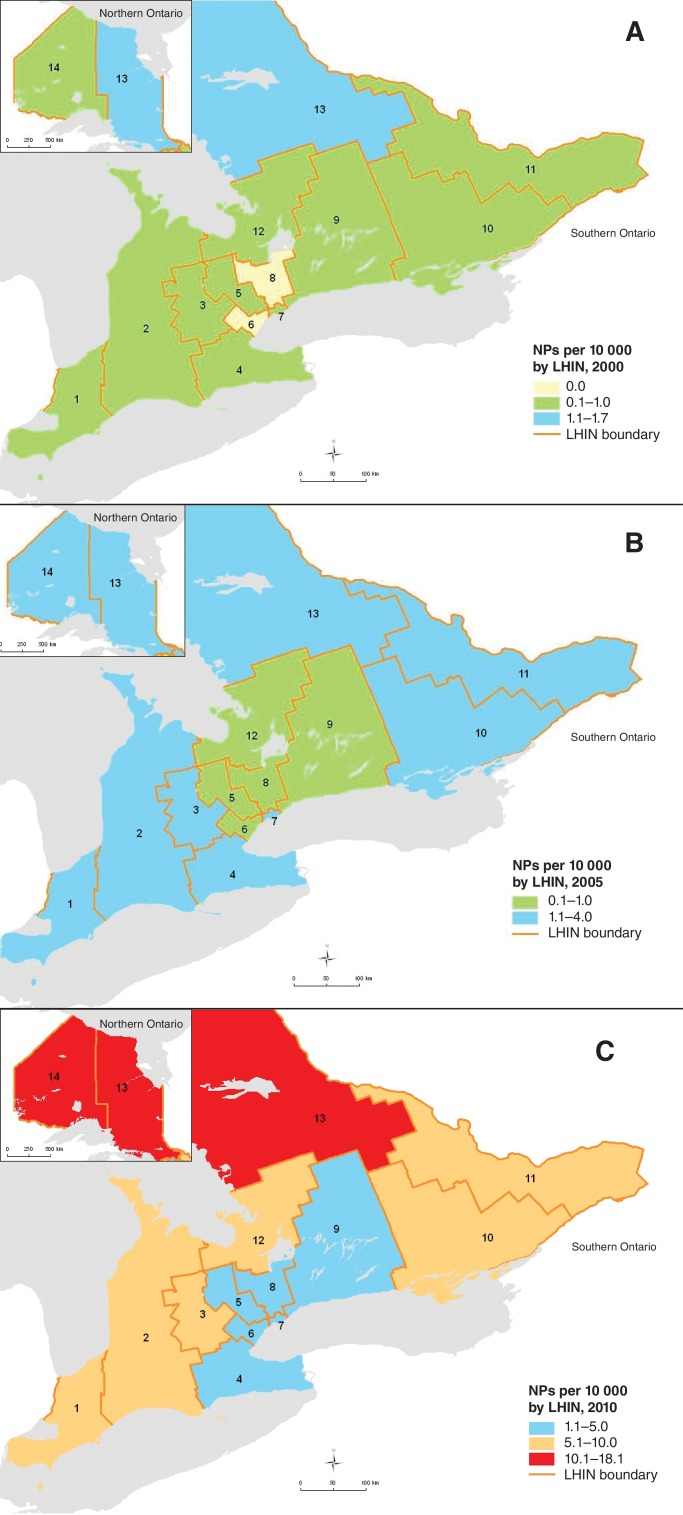

The number of nurse practitioners actively prescribing increased over the 10 years in all health regions (Figure 1). In 2000, the highest number of active prescribers was in the North East Ontario health region, and the lowest number was in the Central and Central West health regions; a similar pattern was noted in 2010. The differential increase in the prevalence of actively prescribing nurse practitioners across health regions was not solely attributable to an aging population within individual regions, as indicated in Table 2. For example, in the North East health region, the percentage increase in older adults was 18.2% over the 10 years, whereas the proportion of nurse practitioners prescribing to this age group decreased by 15.9% during the same period. The Mississauga health region had the largest increase in older adults (53.2%), but only a modest increase in the proportion of nurse practitioners prescribing to this age group (2.5%).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of nurse practitioners (NPs) actively prescribing in 2000 (A), 2005 (B) and 2010 (C) according to the Local Health Integration Network (LHIN) of their practice site. Maps were created by Dr. Peter Gozdyra, Institute of Clinical Evaluative Sciences, Toronto, using ArcGIS 10.2.

Table 2: Change in the proportion of older adults and in prevalence of nurse practitioners prescribing to older adults between 2000 and 2010, by health region .

| Health region | Change in proportion of older adults, % | Change in proportion of nurse practitioners prescribing to older adults, % |

|---|---|---|

| Erie St. Clair | 13.9 | -0.8 |

| South West | 17.3 | 1.0 |

| Waterloo Wellington | 26.4 | 5.2 |

| Hamilton Niagara Haldimand Brant | 19.3 | -0.7 |

| Central West | 41.2 | -2.7 |

| Mississauga Halton | 53.2 | 2.5 |

| Toronto Central | 6.3 | -5.6 |

| Central | 37.0 | 2.6 |

| Central East | 20.1 | 3.2 |

| South East | 22.0 | 3.4 |

| Champlain | 21.7 | 1.4 |

| North Simcoe Muskoka | 41.5 | 3.9 |

| North East | 18.2 | -15.9 |

| North West | 5.9 | 4.6 |

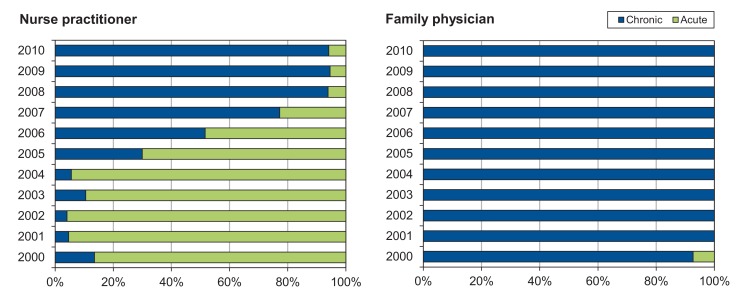

Nurse practitioners' prescribing pattern changed over the study period (Figure 2). Before 2006, nurse practitioners predominantly prescribed medications for acute conditions; by 2010, this trend was reversed, with 9 of the 10 most frequently dispensed medications being for chronic conditions. In contrast, family physicians consistently prescribed a higher proportion of medications for chronic conditions throughout the study period. By 2010, 8 of the top 10 most frequently prescribed medications were the same for nurse practitioners and family physicians (Table 3). The only differences were that family physicians prescribed serotonin inhibitors and benzodiazepines and nurse practitioners prescribed laxatives and bisphosphonates; nurse practitioners were not regulated to prescribe benzodiazepines during the study period.

Figure 2.

Prescribing patterns of nurse practitioners and family physicians for top 10 medications prescribed for acute and chronic indications, 2000-2010.

Table 3: Top 10 medications dispensed to older adults by nurse practitioners (NPs) and family physicians (FPs) in 2000, 2005 and 2010.

| Rank | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP (%) | FP (%) | NP (%) | FP (%) | NP (%) | FP (%) | |||||||||

| 1 | Sulf/tmp* | (22.8) | ACEI* | (6.1) | Fungicides* | (9.6) | Diuretics† | (6.7) | Statins† | (9.2) | Statins† | (7.4) | ||

| 2 | Penicillins* | (12.3) | Benzodiazepine derivatives* | (6.0) | Nonsystemic corticosteroids* | (7.7) | ACEIs† | (6.5) | ACEIs† | (6.5) | PPIs† | (5.6) | ||

| 3 | Nonsystemic corticosteroids* | (11.1) | Diuretics* | (5.5) | Laxatives* | (6.8) | Statins† | (5.9) | Diuretics† | (6.4) | Diuretics† | (5.6) | ||

| 4 | NSAIDs* | (7.7) | CCBs* | (4.9) | Diuretics* | (5.1) | CCBs† | (4.9) | PPIs† | (5.2) | ACEIs† | (5.2) | ||

| 5 | Fungicides* | (7.1) | Beta-blockers* | (4.0) | Miscellaneous local anti-infectives* | (5.1) | Beta-blockers† | (4.8) | Beta-blockers† | (4.8) | CCBs† | (4.7) | ||

| 6 | Antibiotics* | (5.5) | Statins* | (3.8) | Macrolides* | (5.0) | PPIs† | (4.4) | CCBs† | (4.7) | Beta-blockers† | (4.7) | ||

| 7 | Urinary anti-infectives* | (5.2) | NSAIDs† | (3.7) | Analgesics, simple† | (3.8) | Benzodiazepine derivatives† | (4.2) | OHAs† | (4.6) | OHAs† | (4.2) | ||

| 8 | Laxatives* | (4.0) | OHAs† | (3.6) | ACEIs† | (3.8) | OHAs† | (3.9) | Antithyroids, hypothyroidism† | (3.4) | Antithyroids, hypothyroidism† | (3.2) | ||

| 9 | Analgesics, simple† | (3.4) | Histamine H2 receptor antagonists* | (3.5) | Sulf/tmp* | (3.7) | Antithyroids, hypothyroidism* | (3.3) | Laxatives* | (3.0) | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors* | (3.1) | ||

| 10 | Metronidazole* | (3.1) | Narcotics, opiate agonists† | (3.3) | Stool softeners† | (3.5) | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors† | (2.9) | Bisphosphonates† | (3.0) | Benzodiazepine derivatives† | (3.0) | ||

| % of all pre-scriptions | 82 | 45 | 54 | 48 | 51 | 47 | ||||||||

Note: ACEI = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; CCB = calcium-channel blockers; FP = family physician; NP = nurse practitioner; NSAID = nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; OHA = oral antiglycemics; PPI = proton pump inhibitors; sulf/tmp = sulfonamides, trimethoprim and combination. *Medication for acute conditions. †Medication for chronic conditions.

Interpretation

Between 2000 and 2010 the number of nurse practitioners prescribing medications to older adults in Ontario increased markedly. The prescribing pattern also changed substantially during this period, from prescribing of medications predominantly for episodic illness (i.e., acute indications) to prescribing of medications for chronic illnesses, a practice that is similar to that of family physicians. Although the number of nurse practitioners has increased substantially in the province, important differences in the number of practising nurse practitioners across health regions persist, with the northern regions having the highest proportion of nurse practitioners and the central regions having the lowest proportion per capita. Interestingly, the percentage change of nurse practitioners actively prescribing within each health region was not in line with the change in proportion of older adults within the region.

The increase in the actual number of nurse practitioners followed logically the introduction of educational programs for nurse practitioners across Canada, specifically the Ontario Primary Health Care Nurse Practitioner Program (a collaboration of 9 universities). Ongoing primary and community health care reform, such as the introduction of Family Health Teams - teams with budgetary support for nurse practitioners - has supported the integration of nurse practitioners into primary care practices. The largest proportion of nurse practitioners was in the northern regions of the province, regions supposedly less well served by family physicians. The slow uptake of nurse practitioners within the Central West and Toronto Central health regions is an interesting trend and may reflect the slower uptake of primary health care reform strategies within these regions. Currently, of the approximately 200 provincial Family Health Teams, only 38 are located in the Central West and Toronto Centre health regions, regions with the largest population base. Furthermore, as evident from these findings, the percentage increase (or decrease) of nurse practitioners within a region was not aligned with changes in the aging population. Of particular concern is the increasing number of older adults residing in the central region and the limited increase in nurse practitioners and, as well, the decrease in the proportion of nurse practitioners per population in the northeast region. Although nurse practitioners are successfully completing the provincial educational programs, their integration into the health care system appears to be driven more by available resources (i.e., Family Health Teams and community health centres) than by population needs.

Nurse practitioners' prescribing patterns changed across the 10 years and became similar to those of family physicians. The shift to prescribing of medications for chronic conditions does not appear to be attributable to underlying trends in population demographics, as evidenced by the corresponding prescribing trends of family physicians. These study findings extend those of other non-population-based studies that have compared the prescribing patterns of independent or supplementary role nurse practitioners with those of physicians or physician assistants,7,13-15 and they clearly show that nurse practitioners are prescribing in accordance with their role. With the regulatory change introduced in the fall of 2011 and the discontinuation of a restrictive formulary list for prescribing by nurse practitioners, the prescribing patterns of family physicians and nurse practitioners are likely to remain similar, but this would require further validation when this regulatory change is fully integrated into practice. The growing number of older adults with increasingly complex medication protocols for disease conditions, along with the desire to focus care in the primary care setting and the limited availability of health care resources, will challenge primary health care professionals to optimize their respective roles and contributions to care. Recent innovative interdisciplinary models of care in which the nurse practitioner (or nurse) assumes a major role in the care of patients with complex chronic conditions are promising.16-20 However, the care of older patients with multiple chronic conditions is complex and challenging,21,22 and the risk of medication error is associated with increasing age, serious health conditions, multiple medications and multiple transfers between community and hospital care.23,24 This will raise interesting challenges and opportunities for nurse practitioners, family physicians and the health care teams in which they work.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is its population base and the ability to capture most medications dispensed to older adults in Ontario by nurse practitioners with prescribing privileges and family physicians. We were able to capture baseline patterns, before substantial primary health care reform around 2005, and across the 10-year study period. More importantly, these data will enable us to ascertain the impact of the 2011 provincial regulatory change in prescribing privileges and future health care reform.

The data did not include detailed information on patient clinical characteristics or health-related outcomes; this will be the focus for further study. As well, we were unable to determine the practice setting of nurse practitioners. However, this limitation does not influence the interpretation of the results, because we analyzed medications dispensed, not prescribed, which predominantly identifies ambulatory or primary care practices.

Conclusion

The study findings clearly show the growth in numbers of nurse practitioners and the number and types of medications prescribed between 2000 and 2010. Nurse practitioners are an integral and important component of the primary health care system and play a major role in the care of older people with chronic conditions. However, the findings also show that the integration of nurse practitioners has not been consistent across the province and has not occurred in relation to population changes and perhaps population needs.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this article, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/3/3/E299/suppl/DC1. See related CMAJ commentary at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.150913

Appendix

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Senate Advisory Research Council, Queen's University, as well as by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. We thank Peter Gozdyra, ICES, for preparing the spatial map, and Brogan Inc., Ottawa, for use of its Drug Product and Therapeutic Class Database. The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care is intended or should be inferred.

References

- 1.Kroezen M, van Dijk L, Groenewegen PP, et al. Nurse prescribing of medicines in Western European and Anglo-Saxon countries: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:127. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kroezen M, Francke AL, Groenewegen PP, et al. Nurse prescribing of medicines in Western European and Anglo-Saxon countries: a survey on forces, conditions and jurisdictional control. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:1002–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Connell E, Creedon R, McCarthy G, et al. An evaluation of nurse prescribing. Part 2: a literature review. Br J Nurs. 2009;18:1398–402. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2009.18.22.45570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiCenso A, Auffrey L, Bryant-Lukosius D, et al. Primary health care nurse practitioners in Canada. Contemp Nurse. 2007;26:104–15. doi: 10.5172/conu.2007.26.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.History of the NP role development in Ontario. Toronto: Nurse Practitioners' Association of Ontario; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai CL, Sullivan AF, Ginde AA, et al. Quality of emergency care provided by physician assistants and nurse practitioners in acute asthma. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:485–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.01.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladd E. The use of antibiotics for viral upper respiratory tract infections: an analysis of nurse practitioner and physician prescribing practices in ambulatory care, 1997-2001. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2005;17:416–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2005.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stenner K, Carey N, Courtenay M. Nurse prescribing in dermatology: doctors' and non-prescribing nurses' views. J Adv Nurs. 2009;65:851–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis K, Drennan V. Evaluating nurse prescribing behaviour using constipation as a case study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2007;13:243–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-172X.2007.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Creedon R, Weathers E. The impact of nurse prescribing on patients with osteoarthritis. Br J Community Nurs. 2011;16:393–8. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2011.16.8.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian nurse practitioner core competency framework. Ottawa: Canadian Nurses Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidani S, Irvine D, Dicenso A. Implementation of the primary care nurse practitioner role in Ontario. Can J Nurs Leadersh. 2000;13:13–9. doi: 10.12927/cjnl.2000.16302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cipher DJ, Hooker RS, Guerra P. Prescribing trends by nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the United States. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2006;18:291–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2006.00133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooker RS, Cipher DJ. Physician assistant and nurse practitioner prescribing: 1997-2002. J Rural Health. 2005;21:355–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenz ER, Mundinger MO, Hopkins SC, et al. Diabetes care processes and outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians. Diabetes Educ. 2002;28:590–8. doi: 10.1177/014572170202800413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman EA, Grothaus LC, Sandhu N, et al. Chronic care clinics: a randomized controlled trial of a new model of primary care for frail older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:775–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb03832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lenaghan E, Holland R, Brooks A. Home-based medication review in a high risk elderly population in primary care - the POLYMED randomised controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2007;36:292–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Muntinga ME, Hoogendijk EO, van Leeuwen KM, et al. Implementing the chronic care model for frail older adults in the Netherlands: study protocol of ACT (frail older adults: care in transition). BMC Geriatr. 2012;12:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-12-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tracy CS, Bell SH, Nickell LA, et al. The IMPACT clinic: innovative model of interprofessional primary care for elderly patients with complex health care needs. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:e148–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boult C, Reider L, Leff B, et al. The effect of guided care teams on the use of health services: results from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:460–6. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005;294:716–24. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.6.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Upshur RE, Tracy S. Chronicity and complexity: Is what's good for the diseases always good for the patients? Can Fam Physician. 2008;54:1655–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Obreli Neto PR, Nobili A, de Lyra DPJ, et al. Incidence and predictors of adverse drug reactions caused by drug-drug interactions in elderly outpatients: a prospective cohort study. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2012;15:332–43. doi: 10.18433/j3cc86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koper D, Kamenski G, Flamm M, et al. Frequency of medication errors in primary care patients with polypharmacy. Fam Pract. 2013;30:313–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cms070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.