Abstract

A variety of surgical procedures are utilized for management of ankle osteoarthritis. The most common etiology in patients with ankle osteoarthritis is post-traumatic often resulting in asymmetric ankle osteoarthritis with concomitant valgus or varus deformity. A substantial part of tibiotalar joint is often preserved, therefore, in appropriate patients, joint-preserving surgery holds the potential to be a superior treatment option than joint-sacrificing procedures including total ankle replacement or ankle arthrodesis. This review is designed to describe indications and contraindications for single-stage supramalleolar realignment surgery. Complications associated with this type of surgery and postoperative outcome are highlighted using recent literature.

Keywords: Supramalleolar osteotomy, Ankle realignment surgery, Asymmetric ankle osteoarthritis, Indications and contraindications for supramalleolar osteotomy, Intra- and postoperative complications, Clinical outcome following supramalleolar osteotomy

Introduction

Majority of the patients who present with painful end-stage ankle osteoarthritis have had previous osseous injuries or repetitive ligamentous traumas in the past [1–3]. Around 80 % of all cases undergoing surgical treatment of ankle osteoarthritis have post-traumatic etiology [1, 3]. In patients with post-traumatic ankle osteoarthritis, the degenerative changes are often asymmetric resulting in concomitant valgus or varus deformity [4, 5•]. With deformity, a substantial part of the tibiotalar joint can remain preserved; therefore, a joint-sacrificing procedure may not be the most appropriate treatment option in this patient cohort. A joint-preserving procedure (Table 1) should be considered in younger and active patients with asymmetric ankle osteoarthritis.

Table 1.

Different treatment options in patients with ankle osteoarthritis including 2 major groups: joint-preserving and joint-sacrificing procedures

| Procedure | Indications |

|---|---|

| Joint-preserving procedures | |

| Arthroscopy/arthrotomy debridement [6, 7] | • Ankle symptoms from specific joint conditionsa |

| • Anterior ankle impingement | |

| • Early-stage ankle osteoarthritis with intact joint spacea | |

| • Posterior tibial osteophytes; posterior impingement symptoms | |

| • As an adjunctive treatmentb | |

| • Patients with advanced-stage ankle osteoarthritis with joint space narrowing, combined with ankle distraction procedurec | |

| Distraction arthroplasty [8, 9] | • Patients with mid-stage or advanced-stage ankle osteoarthritis with relatively congruent tibiotalar joint surface and well-preserved ankle joint mobility |

| • Younger patients (younger than 50 years) with post-traumatic ankle osteoarthritis | |

| • Partial avascular necrosis of the talus | |

| Osteochondral ankle joint resurfacing [10] | • Primary symptomatic osteochondral lesions generally after failed arthroscopic curettage and debridement. |

| Corrective osteotomies [11•, 12, 13] | • see the text |

| Joint-sacrificing procedures | |

| Total ankle replacement [14–16] | • End-stage ankle osteoarthritis |

| • Salvage procedure in patients with failed primary total ankle replacement | |

| • Salvage procedure in patients with nonunion or malunion of previous ankle arthrodesis | |

| Ankle fusion [17] | • End-stage ankle osteoarthritis |

| • Patients with neurological disorders including poliomyelitis, Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, cerebral paralysis (stroke), Charcot arthropathy etc. | |

| • Salvage procedure in patients with failed primary total ankle replacement | |

| • Patients with severe rigid equinus contracture secondary to compartment syndrome of leg | |

aAthritic disorders that primarily involve synovium of the tibiotalar joint including rheumatoid arthritis, localized pigmented villonodular synovitis, and hemophilic arthropathy [7]

b(eg, before the application of external fixator in the same surgical setting (one-stage procedure) to remove inflamed synovium, unstable cartilage, loose bodies, fibrotic tissue, osteophytes causing impingement [7]

cDebridement of fibrotic tissue and impinging osteophytes in order to improve the ankle dorsiflexion [9]

This review aims to discuss indications and contraindications for supramalleolar osteotomies. Furthermore, complications associated with this type of joint-preserving surgery reported in the current literature are reviewed. Finally, this review is designed to provide clinical outcome in patients who underwent realignment surgery because of asymmetric ankle osteoarthritis.

Historical Perspective on Supramalleolar Osteotomy

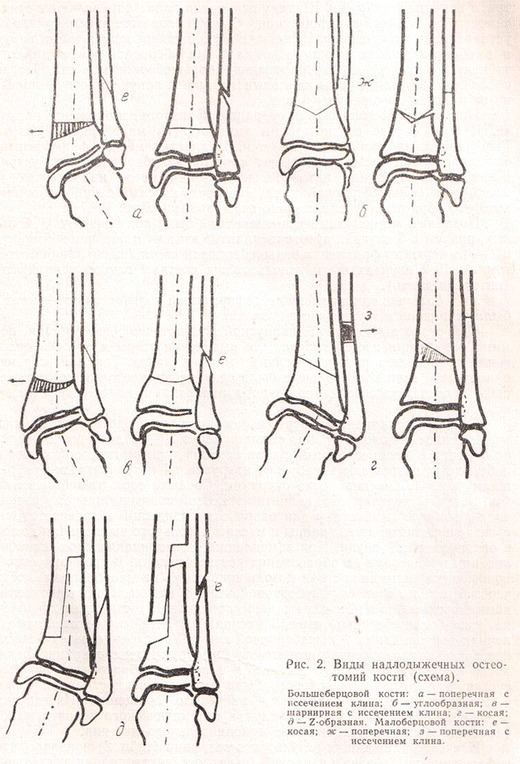

In most review articles [18–22] detailing historical perspective on supramalleolar osteotomy, the study by Takakura et al [23•] is identified as the first clinical study to systematically report outcomes in patients who underwent supramalleolar osteotomy. Indeed, Japanese colleagues from Nara Medical University definitely belong to pioneers on this orthopedic field and substantially influenced the work of many foot and ankle surgeons by their publication entitled “Low tibial osteotomy for osteoarthritis of the ankle. Results of a new operation in 18 patients.” Takakura’s contribution in this area is profound and has had a large influence on the field. Careful review does show that 1 year before this publication, Pearce et al [24] from St Thomas’ Hospital in London, England, published their results of supramalleolar tibial osteotomy performed in 6 patients with hemophilic ankle arthropathy. Furthermore, a literature search using PubMed database with the following keyword “supramalleolar osteotomy” revealed the earliest publication entitled “Надлодыжечные остеотомии у детей и подростков” (“Supramalleolar osteotomies in children and adolescents”) published by Dzakhov and Kurochkin from Leningrad (currently Sankt Petersburg), Russia in 1966 [25]. The authors presented their results in 59 patients who underwent supramalleolar realignment osteotomy between 1936 and 1964. The authors described different types of supramalleolar osteotomies performed in their hospital (Fig. 1). The authors stated that the main indications for supramalleolar osteotomies are deformities in frontal plane of more than 8°–10° and/or rotational deformities of more than 20° without lateral or medial instability of the ankle joint. Furthermore, the authors concluded that undercorrection of the underlying deformity is a substantial predictor of procedure failure resulting in recurrent supramalleolar deformity [25].

Fig. 1.

Different types of supramalleolar osteotomies performed 59 children and adolescent as published by Dzakhov and Kurochkin in 1966 [25]

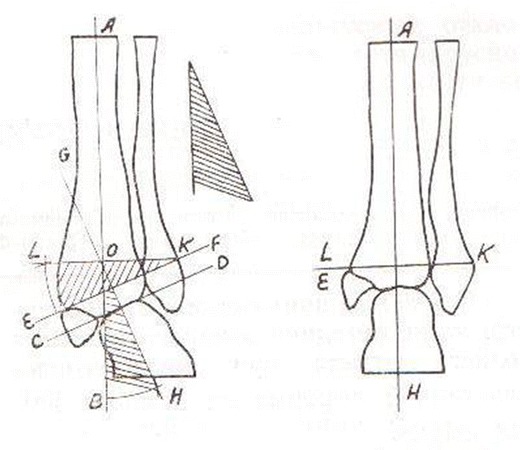

Another early article on supramalleolar osteotomy was published by Barskii and Semenov from Kujbyshev, Russia in 1979 [26]. In their publication entitled “Методика надлодыжечной остеотомии при неправильно сросшихся переломах лодыжек” (“Methods of the supramalleolar osteotomy in ununited fractures of the malleoli”), the authors described in detail their surgical technique and preoperative planning of medial closing-wedge supramalleolar osteotomy (Fig. 2). Realignment surgery was performed in 10 patients with post-traumatic supramalleolar deformities. The authors obtained encouraging results with full function of the ankle joint in 5 patients and with some functional restrictions in other 5 patients at the follow-up between 2 and 6 years [26].

Fig. 2.

Preoperative planning of supramalleolar medial closing-wedge osteotomy as described by Barskii and Semenov in 1979 [26]

When we look deeper we find that even in the 1930s orthopedic surgeons were confronted with treatment of post-traumatic deformities above the ankle joint. Speed and Boyd presented their treatment algorithm of malunited fractures about the ankle joint at the Annual Meeting of the American Orthopedic Association in Philadelphia in 1935. One year later, they published a clinical study including 50 realignment surgeries in patients with post-traumatic deformities [27]. The authors divided malunions above the ankle joint in 2 main groups: following the bimalleolar fracture (Pott’s type) and following the trimalleolar fracture (Cotton’s type). The authors identified 3 crucial aims of supramalleolar realignment surgical procedures: (1) restoration of appropriate weight-bearing alignment of the leg; (2) restoration of the appropriate alignment of articulating surfaced of the tibiotalar joint; and (3) restoration of physiologic and pain free range of motion of the tibiotalar joint.

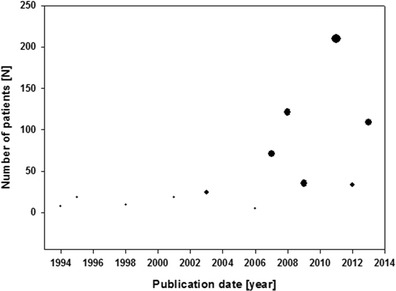

Since Takakura’s report, in the last 2 decades increasing number of clinical studies highlighting functional outcomes in patients who underwent supramalleolar osteotomies have been published (Fig. 3). They consistently show good short-term and mid-term results for pain relief, functional improvement, and return to sports and recreation activities. In the meantime, the clinical studies are not limited only to simple description of supramalleolar osteotomies and their postoperative clinical and radiographic results. Detailed treatment algorithms considering all concomitant pathologies have been described for patient with valgus deformity [13, 28], varus deformity [12, 29], or peritalar instability [30, 31].

Fig. 3.

Number of patients in clinical studies addressing functional outcomes in patients with supramalleolar realignment surgery (Circle size correlates with the number of studies published in the year, range from 1 to 4)

Indications and Contraindications

The major indication for supramalleolar osteotomy is the asymmetric ankle osteoarthritis with concomitant supramalleolar valgus or varus deformity with a partially preserved tibiotalar joint (Table 2). Post-traumatic ankle osteoarthritis is the most common etiology in patients with end-stage ankle osteoarthritis [1, 3]. Horisberger et al [4] analyzed the cohort including 257 consecutive patients with end-stage post-traumatic ankle osteoarthritis. The mean tibiotalar alignment was 88.8° with a range between 63° and 110°. In 49 % of all cases, a substantial varus malalignment was observed with 10 % of all patients having the varus alignment of more than 10°; 50 % and 1 % of all patients had a normal or valgus alignment, respectively [4]. There is no evidence-based literature addressing the limits of degree and extension of degenerative changes in the tibiotalar joint. General recommendations are at least 50 % preserved tibiotalar joint surface [28, 41, 47–49]. In patients with isolated osteochondral lesions of the medial or lateral compartment of the tibiotalar joint with concomitant supramalleolar valgus or varus deformity, supramalleolar osteotomies should be performed before chondral or osteochondral reconstruction of local ankle degeneration [10, 50, 51].

Table 2.

Etiology of ankle osteoarthritis as indication for supramalleolar realignment surgery in patients with asymmetric ankle osteoarthritis (modified and updated from Barg et al [32], Ankle osteoarthritis–etiology, diagnostics, and classification, 2013)

| Author(s) | Year | Patients | Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cheng et al [33] | 2001 | Primary (12) and post-traumatic (6) OA with varus deformity | SM medial opening-wedge OT with fibular OT (18) |

| Colin et al [34•] | 2014 | Post-traumatic (52) OA with varus deformity | SM medial opening-wedge OT (40), SM lateral closing-wedge OT (5), intra-articular medial opening wedge OT (7), fibula OT in 14 cases |

| Colin et al [35] | 2014 | Post-traumatic OA with varus (62) or valgus (21) deformity | lateral closing-wedge OT (41), medial opening-wedge OT (21), medial closing-wedge OT (12), lateral opening-wedge OT (9) |

| Ellington and Myerson [36] | 2013 | Secondary (9) OA with ball and socket ankle | SM medial closing-wedge OT (9) |

| Gessmann et al [37] | 2009 | Post-traumatic (8) OA, malunited ankle arthrodesis (1) | six-axis deformity correction using Taylor spatial frame external fixator (9) |

| Harstall et al [38] | 2007 | Post-traumatic (8) OA, post childhood osteomyelitis (1) | SM lateral closing-wedge OT (9) |

| Hintermann et al [39] | 2011 | Post-traumatic (48) OA | medial closing-wedge OT (45), lateral opening-wedge OT in combination with intra-articular OT (3) |

| Knupp et al [40] | 2012 | Secondary (14) OA (overcorrected clubfoot) with valgus deformity | SM medial closing-wedge OT (14) |

| Lee et al [41] | 2011 | Primary (8) and post-traumatic (ligamentous) (8) OA with varus deformity | SM medial opening-wedge OT with fibular OT (16) |

| Neumann et al [42] | 2007 | Primary (18), post-traumatic (7), and secondary OA because of clubfoot deformity with varus deformity (2) | SM lateral closing-wedge OT (27) |

| Pagenstert et al [43] | 2007 | Post-traumatic (35) OA with varus (13) or valgus (22) deformity | Medial closing-wedge OT (18), medial opening-wedge OT (7), lateral closing-wedge OT (4), others (6) |

| Pagenstert et al [28] | 2009 | Post-traumatic (22) OA with valgus deformity | SM medial closing-wedge OT (22) |

| Pearce et al [24] | 1994 | Secondary (7) OA (hemophilic arthropathy) with valgus deformity | SM medial closing-wedge OT (7) |

| Stamatis et al [44] | 2003 | Primary (5) OA with valgus (1) or varus (4) deformity, secondary (3) OA with valgus deformity, post-traumatic (5) OA with valgus (2) or varus (3) deformity | SM medial closing-wedge OT (8), SM medial opening-wedge OT (5) |

| Takakura et al [23•] | 1995 | Primary (idiopathic) OA with varus deformity (18) | SM medial opening-wedge OT (18) |

| Takakura et al [45] | 1998 | Post-traumatic varus deformity (9) | SM medial opening-wedge OT (9) |

| Tanaka et al [46] | 2006 | OA with varus deformity (26) | SM medial opening-wedge OT with oblique fibular OT (9) |

OA osteoarthritis, OT osteotomy, SM supramalleolar, SMOT supramalleolar osteotomy

Patients with end-stage ankle osteoarthritis requiring a joint-sacrificing procedure— total ankle replacement or ankle arthrodesis—supramalleolar osteotomies may help to improve the biomechanical axis of the lower leg. Clinical and biomechanical studies have demonstrated that alignment and position of prosthesis components may affect biomechanical properties of the replaced ankle and clinical outcomes including range of motion [52–55].

The general contraindications for realignment surgery include acute or chronic infections with or without osteomyelitis, severe vascular or neurologic deficiency, and neuropathic disorders (eg, Charcot arthropathy). Specific contraindication for supramalleolar osteotomies is end-stage ankle osteoarthritis with involvement of entire tibiotalar joint including medial, central, and lateral compartments. Noncompliant patients should also not be considered for this type of surgery because of postoperative rehabilitation: disregard of postoperative nonweight-bearing may lead to fixation implant failure with consequent nonunion at the site of the osteotomy.

Relative contraindications for realignment surgery include impaired bone quality, especially in patients with long-term steroid medication, severe osteoporosis, and rheumatoid disease. An advanced age is another relative contraindication, however, there is no evidence-based literature identifying the age limit. Smoking is also a relative contraindication for supramalleolar osteotomies because of possibly increased rate of osteotomy nonunion [56].

Preoperative Planning

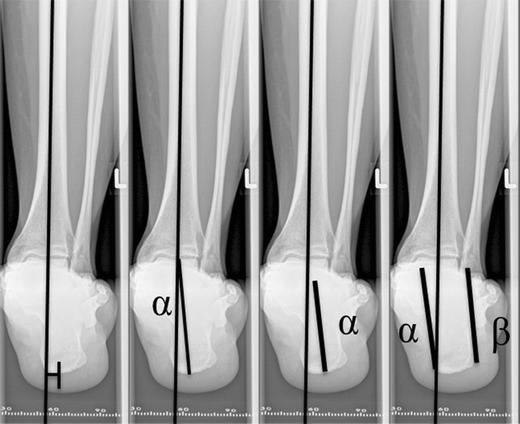

In all patients with ankle osteoarthritis with or without concomitant deformities, we use series of standardized weight-bearing radiographs including a lateral and dorsoplantar view of the foot and anteroposterior view of the ankle, and the hindfoot alignment view [57] (Fig. 4). In patients with additional deformities around the knee joint, whole leg radiographs should additionally be performed.

Fig. 4.

Standard weight-bearing radiographs of foot and ankle including (from left to right) mortise view of the ankle, lateral and dorsoplantar views of the foot, and special hindfoot alignment view

If available, single photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT-CT) may be performed for exact assessment of localization and biological activity of degenerative changes in tibiotalar joint but also in adjacent joints [58, 59].

The medial distal tibial angle is crucial to assess the supramalleolar alignment and to quantify the valgus or varus deformity. It has been measured as 92.4° ± 3.1° (range 84°–100°) and as 93.3° ± 3.2° (range 88°–100°) in radiographic and cadaver studies, respectively [60, 61]. The inframalleolar alignment should be measured using the hindfoot alignment view [57]. There are different methods how to quantify inframalleolar alignment (Fig. 5) including distance and angle between the longitudinal tibial axis and the lowest point of tuber calcanei [57], angle between the longitudinal tibial axis and calcaneal axis [62], and angles between the longitudinal tibial axis and osseous contours of calcaneus [63].

Fig. 5.

Assessment of inframalleolar alignment using the special hindfoot alignment view: A, tuber calcanei distance; B, tuber calcanei angle; C, calcaneal (subtalar joint) axis angle; and D, osseous contours of calcaneus angles

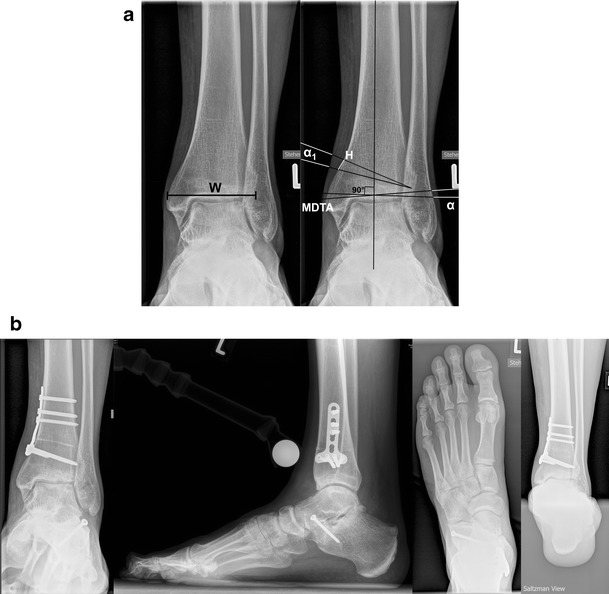

The degree of supramalleolar correction should be planned carefully before the surgery. In theory, for some deformities, a well-designed and executed single osteotomy with realignment can be used to correct all aspects of deformity [64]. However ,for coronal plane malalignments, we find it more reliable to use the following calculation to determine the height of the wedge (H) to be removed (for closing-wedge osteotomy) or widening of osteotomy (H) (for opening-wedge osteotomy): H = tan α1 × W, where α1 is the amount of deformity with the desired overcorrection and W is the width of the distal tibia adjusted for magnification artifact (Fig. 6) [11•, 40, 66].

Fig. 6.

A, Preoperative weight bearing mortise view used for the planning of supramalleolar medial closing-wedge osteotomy (the same patient from the Fig. 4). W width of the distal part of the tibia (in this case 54 mm), α supramalleolar valgus deformity (in this case 5.5°), MDTA medial distal tibial angle [65] (in this case 95.5°), α1 amount of valgus deformity with desired overcorrection (in this case 5.5° + 2° = 7.5°), H height of the wedge to be removed (in this case tan 7.5° × 54 mm = 7 mm). B, Supramalleolar valgus deformity was addressed by supramalleolar medial-closing wedge osteotomy and pes planovalgus et abductus deformity by lateral lengthening osteotomy of calcaneus

Clinical Results Following Supramalleolar Osteotomies

Pearce et al [24] reported their results of supramalleolar varus osteotomy in 6 patients (7 ankles) with secondary valgus ankle osteoarthritis because of severe hemophilia. In all patients, a supramalleolar correction between 10° and 15° was performed by medial closing-wedge osteotomy that was fixed by a single staple. All osteotomies healed within 6 weeks. At the mean follow-up of 9.3 years, a substantial pain relief and functional improvement was observed in all patients. There were no restriction of daily living activities [24].

Takakura et al [23•] presented their midterm results of 18 consecutive patients who underwent medial opening-wedge osteotomy because of asymmetric varus ankle osteoarthritis between 1981 and 1991. There was delayed union in 4 ankles, however, osseous healing completed in all ankles within 6 months. At the latest follow-up of a mean of 6.8 years, all patients experienced substantial pain relief and better ability to walk. The range of motion of operated ankles remained comparable to preoperative status. The authors stated that this type of surgery was still rarely indicated in their clinic representing only 1.5 % of the 1170 foot and ankle surgeries performed during the same time period [23•]. The same authors presented 3 years later additional results of 9 patients [45]. At a mean follow-up of 7.3 years, majority of patients reported excellent or good postoperative results. There were no cases of nonunion in this patient cohort [45]. In 2006, Tanaka et al [46] presented their results in 25 female patients (26 ankles) who underwent medial opening-wedge osteotomy with oblique fibular osteotomy. In all patients, an autograft from the iliac crest or tibia was used. The majority of all patients (19 of 26 ankles) showed excellent or good clinical results at the mean follow-up of 8.3 years (range 2.3–11.9 years). The clinical scores for pain, walking, and activities of daily living significantly improved, however, there was no improvement in postoperative range of motion. In 4 ankles, delayed union at the site of the osteotomy was observed, which was resolved by bone grafting. In 4 ankles, a substantial progression of ankle osteoarthritis resulted in poor outcome. In 2 patients, ankle arthrodesis was performed; another 2 patients were treated conservatively with intraarticular injections of hyaluronic acid [46]. Poorer results were found in patients who had involvement of the superior medial joint space than the medial gutter alone.

Cheng et al [33] performed medial opening-wedge osteotomy with oblique osteotomy of the fibula in 18 ankles. The indication for realignment surgery was post-traumatic and primary osteoarthritis in 6 and 12 ankles, respectively. At the latest follow-up of 4.0 years, the average functional score improved significantly from 49.6 preoperatively to 88.5 postoperatively.

Stamatis et al [44] reported their results of supramalleolar osteotomies in 12 patients (13 ankles) with a supramalleolar deformity of at least 10° with concomitant pain and with or without degenerative changes of the tibiotalar joint. In all patients, medial closing-wedge or medial opening-wedge was performed in 7 and 5 patients, respectively. All supramalleolar osteotomies healed at an average time of 14 weeks without time difference between 2 groups with closing-wedge and opening-wedge procedure. At the latest follow-up of 2.8 years, the average American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) hindfoot score significantly improved from 53.8 ± 19.3 preoperatively to 87.0 ± 10.1 postoperatively. All patients experience substantial pain relief as assessed using AOFAS pain subscale (from 14.6 ± 10.5 preoperatively to 32.3 ± 5.9 postoperatively). In all ankles, no evidence of progression of the degenerative changes in the last follow-up radiographs was observed [44].

Harstall et al [38] performed lateral closing-wedge osteotomy in 9 patients with asymmetric varus ankle osteoarthritis and reported their results at the mean follow-up of 4.7 years. There were no intra- or postoperative complications in this patient cohort. All patients experienced significant pain relief (pain score from 16 ± 8.8 preoperatively to 30 ± 7.1 postoperatively) and functional improvement (AOFAS hindfoot score from 48 ± 16.0 preoperatively to 74 ± 11.7 postoperatively). The hindfoot alignment (tibial-ankle surface angle) improved from 6.9° ± 3.8° varus preoperatively to 0.6° ± 1.9° valgus postoperatively. At the final follow-up in two patients, a substantial progression of ankle osteoarthritis was observed requiring ankle arthrodesis in one patient 16 months after initial realignment surgery [38].

Neumann et al [42] described in their surgical technique article the supramalleolar lateral closing-wedge osteotomy in detail. The main indication in their patient cohort including 27 patients was varus asymmetric deformity with concomitant deformity of at least 15°. The mean preoperative varus deformity was 27° with a range between 17° and 46°. The mean postoperative hindfoot alignment was 6° of varus with a range between 0° and 13°. The majority of all patients (21 patients) were very satisfied with postoperative results at the 6-month follow-up [42].

Pagenstert et al [43] described detailed treatment algorithm of realignment surgery as alternative treatment in patients with varus or valgus ankle osteoarthritis. In total, 35 consecutive patients were included into this clinical and radiographic study with a mean follow-up of 5 years. Most patients experienced a significant pain relief by an average of 4 points on a visual analog scale; 10 patients were completely pain free and 18 patients had moderate pain with visual analog scale between 2 and 4. The AOFAS hindfoot scale significantly improved from 38.5 ± 17.2 preoperatively to 85.4 ± 12.4 postoperatively. The average ankle range of motion also significantly improved from 32.8° ± 14.0° preoperatively to 37.7° ± 9.4° postoperatively. Revision surgery was necessary in 10 ankles including 3 conversions to total ankle replacement [43].

Hintermann et al [67] described their treatment algorithm in patients with supramalleolar deformities. The presented patient cohort included 74 consecutive patients who underwent supramalleolar osteotomies between 1995 and 2006. At the mean follow-up of 4.1 years, the AOFAS hindfoot score significantly improved from 29 preoperatively to 84 postoperatively. The majority of all patients (64 ankles) were satisfied or very satisfied with postoperative results.

Gessmann et al [37] used the Taylor spatial frame external fixator for correction of complex supramalleolar deformities in 9 patients between 2003 and 2007. The indication for realignment surgery was malunion of supramalleolar fractures and malunion after ankle arthrodesis in 6 and 3 patients, respectively. The mean preoperative angular deformity was 30°, in 5 patients tibia lengthening between 10 and 40 mm was performed additionally. At the mean follow-up of 1.9 years, anatomic restoration of the hindfoot alignment was achieved in all patients [37].

Hintermann et al [39] performed a prospective study to address the clinical and radiographic outcome of supramalleolar osteotomies in 48 consecutive patients with malunited pronation-external rotation fractures of the ankle. In 45 patients, a medial closing-wedge osteotomy was performed. In 3 patients, a lateral opening-wedge osteotomy was necessary. In 19 patients, inframalleolar osteotomy of the calcaneus was performed additionally for complete realignment of the hindfoot. All patients were followed clinically and radiographically at a mean follow-up of 7.1 years. At the latest follow-up, 41 patients were pain free; in other cases, visual analog scale varied between 1 and 4. The majority of patients could return to their former professional and sports activities. Analysis of the pre- and postoperative radiologic evidence of osteoarthritis revealed that there was no evidence of osteoarthritis progression in 30 patients, 14 patients showed slight progression, and 3 patients had considerable degenerative changes of the ankle [39].

Knupp et al [5•] presented a detailed classification of supramalleolar deformities based on clinical findings in 92 consecutive patients (94 ankles), who underwent supramalleolar osteotomy for asymmetric ankle osteoarthritis between 1996 and 2008. Based on described classification, authors presented their treatment algorithm considering additional surgical procedures including inframalleolar realignment procedures and soft tissue reconstruction procedures. The mean follow-up was 3.6 years in this prospective clinical and radiographic study. All osteotomies healed within 12 weeks postoperatively. There were no cases of nonunion or malunion with consecutive secondary loss of correction. Clinical scores including AOFAS hindfoot score and visual analog score significantly improved. In patients with preoperative mid-stage ankle osteoarthritis, a reduction of radiologic signs of degenerative changes has been achieved. Ten ankles had to be converted to total ankle replacement or ankle arthrodesis. Following ankle osteoarthritis types were found to have tendencies towards worse outcomes or failures: type I valgus ankles with fibular malalignment; type III varus ankles, and patients with concomitant ankle joint instability [5•].

Lee et al [41] reported their results in 16 ankles treated with supramalleolar osteotomy combined with fibula osteotomy because of moderate medial ankle osteoarthritis. At the mean follow-up of 2.3 years, substantial functional improvement including AOFAS hindfoot score was observed. The degree of degenerative changes in the tibiotalar joint was assessed using Takakura classification system, which has been improved from 2.9 ± 0.7 preoperatively to 2.3 ± 1.1 postoperatively. All radiographic parameters also improved significantly after realignment surgery. The authors have identified that the supramalleolar osteotomy has the best clinical outcome in patients with moderate talar tilt (less than 7.3°) and neutral or varus heel alignment [41].

Knupp et al [40] reported their results of realignment surgery in 14 patients treated between 2002 and 2009 because of overcorrected clubfoot deformity. All osteotomies healed within 8 weeks without any loss of correction. The mean follow-up was 4.2 years. The hindfoot alignment substantially improved as assessed by using of mean tibial articular surface angle (from 96.6° ± 4.0° to 88.4° ± 3.6°) and tibiotalar angle (from 101.1° ± 6.4° to 92.2° ± 4.5°). All patients experienced significant pain relief (visual analog scale from 4.1 ± 1.7 to 2.2 ± 1.5) and functional improvement (AOFAS hindfoot score from 51.6 ± 12.3 to 77.8 ± 11.8). Overall, 5, 7, and 2 patients were very satisfied, satisfied, and satisfied with reservation, respectively [40].

Mann et al [68] described a novel surgical technique of intraarticular medial opening-wedge osteotomy for the treatment of intraarticular varus ankle osteoarthritis with concomitant instability—so called plafond-plasty. The surgical technique includes an osteotomy, which is performed not above, as the supramalleolar osteotomy, nor below the ankle, as the inframalleolar calcaneus osteotomies, but intraarticular at the level of the deformity with regard to the center of rotation and angulation (CORA). This may help to avoid a secondary translational deformity as, eg, in patients with supramalleolar osteotomy, when the osteotomy is not performed exactly at the level of CORA. Six osteotomies were stabilized with screws alone; in other 13 ankles, a combined stabilization with plane and screws was performed. In 18 of 19 patients, the lateral ligamental reconstruction was performed at the time of the index surgery. Nineteen consecutive patients were followed clinically and radiographically for a mean of 4.9 years. The pre- and postoperative radiographic parameters including tibial ankle surface and tibial lateral surface angles were comparable. The varus ankle tilt significantly improved from 18° preoperatively to 10° postoperatively. All patients experienced functional improvement with pre- and postoperative AOFAS hindfoot scores of 46 and 78 points, respectively. Two patients underwent total ankle replacement at 30 and 48 months, and two other patients underwent ankle arthrodesis at 7 and 36 months. In all 4 patients, the indication for joint-sacrificing conversion was progressive pain, in 2 patients with ankle arthrodesis substantial progression of ankle osteoarthritis. The majority of all patients (15 ankles) were either satisfied or very satisfied with functional outcome of this procedure [68].

Barg et al [47] reported a consecutive series of 42 patients with asymmetric post-traumatic ankle osteoarthritis. Twenty-six patients had a valgus deformity, which was treated by medial closing-wedge osteotomy. Eleven patients with a varus deformity were treated by medial opening-wedge or lateral closing-wedge osteotomy in 11 and 5 ankles, respectively. All supramalleolar osteotomies healed within 4 months. In all patients, a substantial pain reduction was observed [47].

Ellington and Myerson [36] presented their treatment algorithm in adult patients with ball and socket ankle joint with a concomitant talonavicular tarsal coalition. In total, 13 patients with a minimum follow-up of 2.5 years were included into this retrospective study. In 9 of 13 patients, medial closing-wedge osteotomy was performed in combination with calcaneal osteotomy (n = 4), fibular osteotomy (n = 5), and medial cuneiform osteotomy (n = 3). There were no nonunions in the supramalleolar osteotomy group. The AOFAS hindfoot score significantly improved from 30.1 preoperatively to 77.6 postoperatively. The arthritis grade remained unchanged in 4 patients and worsened in 5 patients by 1 grade. In 1 patient, an ankle arthrodesis was performed 7 years after initial realignment surgery because of progressive pain. In another patient, a below-knee amputation was necessary 3 years after index surgery because of progressive pain and osteoarthritis [36].

Very recently, Colin et al [34•] performed a comparative study to address the effect of supramalleolar osteotomy and total ankle replacement on talar position in patients with varus ankle osteoarthritis. In total, 104 ankles were included in this prospective study, 52 of which were treated with supramalleolar osteotomy and 52 with total ankle replacement. The underlying supramalleolar varus deformity was corrected by medial opening-wedge, lateral closing-wedge, and intraarticular medial opening-wedge osteotomy in 40, 5, and 7 patients, respectively. The hindfoot alignment was improved in both groups, however, in the osteotomy group the talar tilt angle was not fully corrected and the talometatarsal I angle remained unchanged [34•].

Complications Associated with Supramalleolar Osteotomies

There are no clinical studies up to date specifically addressing complications associated with supramalleolar osteotomies. In general, in review articles about this type of surgery complications are reported as rare in patients who underwent supramalleolar osteotomies [18, 19, 22]. Postoperative complications associated with supramalleolar osteotomies reported in published clinical studies are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Complications in patients with supramalleolar osteotomies: current literature review (modified and updated from Barg et al [11•], Supramalleolar osteotomies for degenerative joint disease of the ankle joint: indication, technique and results, 2013)

| Study | LoE | Patients | Surgical technique | Complications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best and Daniels (2006) [69] | V | 4 (5 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT (5) | None |

| Cheng et al (2001) [33] | IV | 18 (18 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT with oblique OT of the fibula (18) | Late infection (1; 5.6 %), implant failure with delayed union (2; 11.1 %) |

| Colin et al (2014) [34•] | III | 52 (52 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT (40), lateral closing-wedge OT (5), intra-articular medial opening-wedge OT (7) | None |

| Colin et al (2014) [35] | IV | 83 (83 ankles) | Lateral closing-wedge OT (41), medial opening-wedge OT (21), medial closing-wedge OT (12), lateral opening-wedge OT (9) | Impingement (1; 1.2 %), scar dehiscence (1; 1.2 %), overcorrection (1; 1.2 %), progression of ankle OA (1; 1.2 %), nonunion (1; 1.2 %), septic nonunion (1; 1.2 %), sepsis (1; 1.2 %) |

| Ellington and Myerson (2013) [36] | III | 9 (9 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (9) | Progression of ankle OA requiring ankle arthrodesis (1; 11.1 %) and below-knee amputation (1; 11.1 %) |

| Gessmann et al (2009) [37] | IV | 9 (9 ankles) | Six-axis deformity correction using Taylor spatial frame external fixator (9) | Superficial pin site infections (2; 22.2 %), delayed union (2; 22.2 %) |

| Harstall et al (2007) [38] | IV | 9 (9 ankles) | Lateral closing-wedge OT (9) | Progression of ankle OA requiring ankle arthrodesis (1; 11.1 %) |

| Hintermann et al (2008) [67] | IV | 74 (74 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (38), medial opening-wedge OT (8), lateral closing-wedge OT (11), others (17) | Progression of ankle OA requiring TAR (2; 2.7 %), unmanageable ankle instability requiring ankle arthrodesis (1; 1.4 %) |

| Hintermann et al (2011) [39] | IV | 48 (48 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (45), lateral opening-wedge OT in combination with intra-articular OT (3) | Delayed wound healing (3; 6.3 %), delayed osseous union (2; 4.2 %), persistent valgus malalignment because of undercorrection (2; 4.2 %), subsequent TAR because of progressive OA (1; 2.1 %) |

| Horn et al (2011) [70] | IV | 52 (52 ankles) | Six-axis deformity correction using circular external Ilizarov fixation (52) | Superficial pin site infections (27; 51.9 %), cellulitis requiring i.v. antibiotics (4; 7.7 %), osteomyelitis requiring surgical debridement (1; 1.9 %), nonunion (3; 5.8 %), septic ankle arthritis requiring arthrotomy and debridement (2; 3.8 %), subsequent ankle arthrodesis because of recurrence of pain (3; 5.8 %) |

| Knupp et al (2008) [29] | IV | 12 (12 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT or lateral closing-wedge OT (12) | None |

| Knupp et al (2009) [71] | IV | 12 (12 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT (7), lateral closing-wedge OT (5) | None |

| Knupp et al (2011) [5•] | II | 92 (94 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (61), lateral closing-wedge OT or medial opening-wedge OT (33) | Superficial wound healing problems (5; 5.3 %), deep infection requiring surgical debridement (1; 1.1 %), reconstruction of anterior tibial tendon because of laceration (1; 1.1 %), painful neuroma of the saphenous nerve (2; 2.1 %), progression of ankle OA requiring TAR (9; 9.6 %) or ankle arthrodesis (1; 1.1 %) |

| Knupp et al (2012) [40] | IV | 14 (14 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (14) | Superficial wound healing problems (2; 14.3 %), progression of flatfoot deformity (2; 14.3 %) with persisting medial pain requiring medial displacement calcaneus osteotomy (1; 7.1 %) |

| Lee and Cho (2009) [72] | V | n.a. | Oblique medial opening-wedge OT without fibular OT for varus deformity | None |

| Lee et al (2011) [41] | IV | 16 (16 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT with fibular OT (16) | Persisting/progressive talar tilt ≥9.5° (4; 25.0 %), lateral subfibular pain (4; 25.0 %) |

| Mann et al (2012) [68] | IV | 19 (19 ankles) | Intra-articular medial opening-wedge OT (plafond-plasty) (19) | Progression of ankle OA requiring TAR (2; 10.5 %) or ankle arthrodesis (2; 10.5 %) |

| Neumann et al (2007) [42] | IV | 27 (27 ankles) | Lateral closing-wedge OT (27) | Progression of ankle OA requiring TAR (3; 11.1 %) or ankle arthrodesis (3; 11.1 %) |

| Pagenstert et al (2007) [43] | IV | 35 (35 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (18), medial opening-wedge OT (7), lateral closing-wedge OT (4), others (6) | Progression of ankle OA requiring TAR (3; 8.6 %), recurrent deformity (2; 5.7 %), nonunion requiring grafting (1; 2.9 %), superficial wound infection requiring debridement (1; 2.9 %), delayed wound healing (1; 2.9 %), deep vein thrombosis (1; 2.9 %) |

| Pagenstert et al (2008) [49] | II | 35 (35 ankles) | n.a. | Progression of ankle OA requiring TAR (3; 8.6 %), nonunion (2; 5.7 %), recurrent deformity (2; 5.7 %), wound healing problems (2; 5.7 %), painful hardware requiring implant removal (7; 20.0 %) |

| Pagenstert et al (2009) [28] | IV | 14 (14 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (14) | Progression of ankle OA requiring TAR (2; 14.3 %), nonunion requiring grafting (1; 7.1 %), deformity undercorrection requiring revision surgery (1; 7.1 %) |

| Pearce et al (1994) [24] | IV | 6 (7 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (7) | None |

| Stamatis et al (2003) [44] | IV | 12 (13 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (7), medial opening-wedge OT (6) | Delayed union requiring bone grafting (1; 7.7 %), decreased ankle ROM (3; 23.1 %), superficial infection (1; 7.7 %) |

| Takakura et al (1995) [23•] | IV | 18 (18 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT with oblique fibula OT (18) | Delayed union (4; 22.2 %), undercorrection (2; 11.1 %) |

| Takakura et al (1998) [45] | IV | 9 (9 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT with oblique fibula OT (9) | Delayed union (1; 11.1 %), decreases ROM (6; 66.7 %), persisting medial pain (2; 22.2 %) |

| Tanaka et al (2006) [46] | IV | 25 (26 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT with oblique fibular OT (26) | Delayed union requiring bone grafting (4; 15.4 %); progression of ankle OA (4; 15.4 %) requiring ankle arthrodesis (2; 7.7 %) |

i.v. intravenous, LoE level of evidence, OA osteoarthritis, OT osteotomy, n.a. not available, ROM range of motion, TAR total ankle replacement.

Intraoperatively, injuries of neurovascular injuries and tendons may occur. However, exact incidence of intraoperative complications is not known. Furthermore, exact knowledge of surgical approach anatomy and protection of soft tissue including tendons using Hohmann hooks may help to avoid the intraoperative complications.

Wound healing problems and infections are reported to have an incidence up to 22 % in the current literature. Early superficial infections may be resolved by i.v. application of antibiotics. In patients with deep infection surgical debridement and irrigation are necessary to treat infection. In some cases hardware removal and temporary stabilization with external fixator should be performed.

Malunion or nonunion at the supramalleolar osteotomy site is another major complication with an incidence up to 22 % in the current literature. This type of postoperative complication may have different reasons. First, surgical technique that breaches the opposite cortex may result in substantially decreased initial stability of the osteotomy. In such cases, we recommend stabilization of the opposite cortex using a stable plate through the same or if necessary additional incision. Second, nonanatomical reduction of the osteotomy may lead to secondary displacement of the osteotomy. Third, disregard of postoperative rehabilitation with nonweightbearing (eg, noncompliant patients) may lead to hardware failure with consecutive loss of correction resulting in malunion or non-union of the osteotomy. In the current literature, there is little comparative evidence of surgical technique, use of autograft or allograft, or type of osteotomy fixation as a possible risk factor for osseous nonunion in patients who underwent supramalleolar osteotomy (Table 4). Stamatis et al [44] performed supramalleolar osteotomy in patients with supramalleolar varus or valgus deformity. The authors performed 7 medial closing-wedge osteotomies and 6 medial opening-wedge osteotomies. The mean time until osseous healing was 10.6 ± 5.2 weeks (range, 6–22 weeks) and 18.2 ± 9.8 weeks (range, 10–36 weeks) in patients with closing-wedge and opening-wedge osteotomy, respectively. However, this study did not specifically address the comparison of 2 osteotomy types; therefore, it is not clear whether the difference in osseous union time is free of bias (eg, risk factors etc.) [44]. It remains controversial, which type of osteotomy should be performed in patients with supramalleolar varus deformity: lateral closing-wedge osteotomy or medial opening-wedge osteotomy. The medial approach is easier to perform, however, in patient with preoperative varus deformity of more than 10°, an appropriate correction often cannot be achieved with a tibial osteotomy alone because the fibula may restrict the degree of supramalleolar correction [5•, 11, 29].

Table 4.

Surgical technique, use of graft, osteotomy fixation, and osseous union in patients with supramalleolar osteotomies: current literature review.

| Study | Patients | Surgical technique | Graft | Osteotomy fixation | Osseous union |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barg et al (2013) [47] | 42 (42 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (26), medial opening-wedge OT (11), lateral closing-wedge OT (5) | No bone graft for closing-wedge OT, allograft of autograft harvested from the ipsilateral iliac crest (11) | T-shaped 3.5-mm locking compression plate | All osteotomies healed within of 16 wk |

| Cheng et al (2001) [33] | 18 (18 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT with oblique OT of the fibula (18) | Cancellous bone autograft (18) | AO plate (18) | Delayed union with implant failure in 2 patients |

| Colin et al (2014) [35] | 83 (83 ankles) | Lateral closing-wedge OT (41), medial opening-wedge OT (21), medial closing-wedge OT (12), lateral opening-wedge OT (9) | Tricortical iliac autograft in all opening-wedge OT (20) | staple fixation | Mean time to osseous union was 11 wk (8–24), 2 patients with nonunion, there was no significant difference in the time until union in relation the type of OT |

| Harstall et al (2007) [38] | 9 (9 ankles) | Lateral closing-wedge OT (9) | No bone graft | two short plates: 2-hole and 3-hole third-tubular plate (9) | Mean time to osseous union was 9.8 ± 3.1 wk (6–14) |

| Hintermann et al (2011) [39] | 48 (48 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (45), lateral opening-wedge OT in combination with intra-articular OT (3) | No bone graft for closing-wedge OT, wedge-shaped allograft in opening-wedge OT (3) | 2.7-mm plate and screws | In all but 2 patients osteotomies healed after 9.6 wk (8–18), 2 patients with delayed union after 24 and 28 wk |

| Knupp et al (2011) [5•] | 92 (94 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (61), lateral closing-wedge OT or medial opening-wedge OT (33) | Human cancellous allograft (33) | Rigid plate fixation with locking screws (94) | All osteotomies healed within 12 wk |

| Lee and Cho (2009) [72] | n.a. | Medial opening-wedge OT without fibular OT | Cancellous bone allograft | Single opening wedge plate | None |

| Lee et al (2011) [41] | 16 (16 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT with fibular OT (16) | Autogenous iliac crest bone graft or allograft | 7-hole dynamic compression plate | n.a. |

| Mann et al (2012) [68] | 19 (19 ankles) | Intra-articular medial opening-wedge OT (plafond-plasty) (19) | Allograft cancellous bone chips (19) | 3 cannulated screws inserted perpendicular to the tibia (first 6 cases), locking plate (subsequent 13 cases) | n.a. |

| Pagenstert et al (2007) [43] | 35 (35 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (18), medial opening-wedge OT (7), lateral closing-wedge OT (4), others (6) | No bone graft for closing-wedge OT, allograft (4), autograft (5; harvested by Dwyer closing wedge calcaneus OT in 4 patients and iliac crest in 1 patient) | Cervical plate, blade plate, or 3.5-mm AO plate with interlocking screws | Nonunion in 2 patients requiring grafting and re-fixation |

| Stamatis et al (2003) | 12 (13 ankles) | Medial closing-wedge OT (7), medial opening-wedge OT (6) | No bone graft for closing-wedge OT, structural allograft alone (1) or in combination with autograft from the tibial tubercle (5) in medial opening-wedge OT | Periarticular titanium plane with at least 3 screws in the distal segment (12), cervical spine plate (1) | Mean time to osseous union was 10.6 ± 5.2 wk (6–22) and 18.2 ± 9.8 wk (10–36) in patients with medial closing-wedge and opening-wedge OT, respectively, delayed union after 36 wk requiring bone grafting in 1 patient with medial opening-wedge OT |

| Takakura et al (1995) [23•] | 18 (18 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT with oblique fibula OT (18) | Autograft from the iliac crest or from the tibia near the osteotomy site (18) | 4- or 5-hole plate | delayed union in 4 patients, but all osteotomies united within 6 mo |

| Takakura et al (1998) [45] | 9 (9 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT with oblique fibula OT (9) | Autograft from iliac cresta (9) | AO plate (1), 2–4 Kirschner wires (8) | delayed union after 25 wk in 1 patient |

| Tanaka et al (2006) [46] | 25 (26 ankles) | Medial opening-wedge OT with oblique fibular OT (26) | Autograft from the iliac crest or from the tibia (18) | 4- or 5-hole AO narrow plate or 6- or 8-hole form plate | All but 4 osteotomies healed from 7–3 wk after surgery, in 4 ankles with delayed union after 6 mo bone grafting was performed |

AO Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen, n.a. not available, OA osteoarthritis, OT osteotomy

aThe height of the bone graft averaged 12.4 ± 4.0 mm; the width, 24.6 ± 2.9 mm; the depth, 11.8 ± 3.3 mm

The progression of degenerative osteoarthritis of the tibiotalar joint in patients who underwent supramalleolar osteotomy is reported in the current literature to be up to 25 % in the current literature. In such cases, painful progressive ankle osteoarthritis should be treated by ankle arthrodesis or total ankle replacement.

Conclusions

Supramalleolar realignment surgery as a treatment option in patients with beginning or midstage ankle coronal plane malalignment has become increasingly more commonly done in the last two decades. Clinical studies consistently show good clinical results, efficient postoperative correction of underlying hindfoot deformity, and acceptable patient satisfaction. Supramalleolar realignment surgery firmly belongs to surgical armamentarium of orthopedic foot and ankle surgeons. This type of surgery should be considered as an alternative treatment option in patients with beginning or midstage asymmetric ankle osteoarthritis with concomitant valgus or varus deformity. However, the appropriate choice of the “ideal” patient for this surgery and recognition and analysis of all contraindications for this procedure is not simple and comes from experience and prudent patient selection. Each candidate for supramalleolar realignment surgery needs a careful and individual clinical and radiographic assessment [32]. The underlying osseous deformity and its origin should be recognized and degree of deformity should be quantified preoperatively. Also, all concomitant problems including ligamentous instability, additional deformities (eg, around the knee joint), and/or ligament instability need to be addressed if supramalleolar realignment surgery is planned.

Furthermore, as simple it sounds—the supramalleolar osteotomies should be performed for correction of supramalleolar deformities. In patients with concomitant inframalleolar deformities, additional surgical procedures are needed to achieve the appropriate alignment of the hindfoot, especially subtalar joint position and mobility need to be considered when doing these procedures. If necessary, corrective subtalar arthrodesis (in patients with substantial subtalar osteoarthritis) or corrective osteotomies of calcaneus (lateral lengthening calcaneal osteotomy or medial sliding calcaneus osteotomy in patients with valgus deformity or calcaneal Dwyer osteotomy or lateral sliding osteotomies in patients with varus deformity) should be performed to restore the inframalleolar alignment of the hindfoot.

Promising short- and midterm results have been reported in patients who underwent supramalleolar realignment surgery. Further long-term studies are needed to identify significant risk factors for progression of ankle osteoarthritis which may result in failure of realignment surgery requiring total ankle replacement or ankle arthrodesis. Improved biomechanical studies should be performed to highlight the effect of supramalleolar osteotomies on ankle biomechanics and kinematics.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Anatoly Baranetskij, MD and Gleb Korobushkin, MD for sending the original publications by Dzakhov et al and Barskii et al.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

Alexej Barg declares that he has no conflict of interest. Dr. Saltzman reports personal fees from Zimmer, personal fees from Tornier, personal fees from Wright medical, personal fees from Smith and Newphews.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

- 1.Saltzman CL, Salamon ML, Blanchard GM, et al. Epidemiology of ankle arthritis: report of a consecutive series of 639 patients from a tertiary orthopaedic center. Iowa Orthop J. 2005;25:44–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valderrabano V, Hintermann B, Horisberger M, et al. Ligamentous posttraumatic ankle osteoarthritis. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(4):612–20. doi: 10.1177/0363546505281813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valderrabano V, Horisberger M, Russell I, et al. Etiology of ankle osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(7):1800–6. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0543-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horisberger M, Valderrabano V, Hintermann B. Posttraumatic ankle osteoarthritis after ankle-related fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23(1):60–7. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31818915d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.•.Knupp M, Stufkens SA, Bolliger L, et al. Classification and treatment of supramalleolar deformities. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32:1023–31. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2011.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Sekyi-Otu A. Arthroscopic debridement for the osteoarthritic ankle. Arthroscopy. 1995;11(4):433–6. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(95)90197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phisitkul P, Tennant JN, Amendola A. Is there any value to arthroscopic debridement of ankle osteoarthritis and impingement? Foot Ankle Clin. 2013;18(3):449–58. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barg A, Amendola A, Beaman DN, et al. Ankle joint distraction arthroplasty: why and how? Foot Ankle Clin. 2013;18(3):459–70. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saltzman CL, Hillis SL, Stolley MP, et al. Motion versus fixed distraction of the joint in the treatment of ankle osteoarthritis: a prospective randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(11):961–70. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiewiorski M, Barg A, Valderrabano V. Chondral and osteochondral reconstruction of local ankle degeneration. Foot Ankle Clin. 2013;18(3):543–54. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.•.Barg A, Pagenstert GI, Horisberger M, et al. Supramalleolar osteotomies for degenerative joint disease of the ankle joint: indication, technique and results. Int Orthop. 2013;37:1683–95. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2030-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Myerson MS, Zide JR. Management of varus ankle osteoarthritis with joint-preserving osteotomy. Foot Ankle Clin. 2013;18(3):471–80. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valderrabano V, Paul J, Horisberger M, et al. Joint-preserving surgery of valgus ankle osteoarthritis. Foot Ankle Clin. 2013;18(3):481–502. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saltzman CL. Perspective on total ankle replacement. Foot Ankle Clin. 2000;5(4):761–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saltzman CL, Mann RA, Ahrens JE, et al. Prospective controlled trial of STAR total ankle replacement versus ankle fusion: initial results. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(7):579–96. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2009.0579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valderrabano V, Pagenstert GI, Muller AM, et al. Mobile- and fixed-bearing total ankle prostheses: is there really a difference? Foot Ankle Clin. 2012;17(4):565–85. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nihal A, Gellman RE, Embil JM, et al. Ankle arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;14(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker AS, Myerson MS. The indications and technique of supramalleolar osteotomy. Foot Ankle Clin. 2009;14(3):549–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benthien RA, Myerson MS. Supramalleolar osteotomy for ankle deformity and arthritis. Foot Ankle Clin. 2004;9(3):475–87. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knupp M, Bolliger L, Hintermann B. Treatment of posttraumatic varus ankle deformity with supramalleolar osteotomy. Foot Ankle Clin. 2012;17(1):95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stamatis ED, Myerson MS. Supramalleolar osteotomy: indications and technique. Foot Ankle Clin. 2003;8(2):317–33. doi: 10.1016/S1083-7515(03)00018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swords MP, Nemec S. Osteotomy for salvage of the arthritic ankle. Foot Ankle Clin. 2007;12(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.•.Takakura Y, Tanaka Y, Kumai T, et al. Low tibial osteotomy for osteoarthritis of the ankle. Results of a new operation in 18 patients. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1995;77(1):50–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pearce MS, Smith MA, Savidge GF. Supramalleolar tibial osteotomy for haemophilic arthropathy of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 1994;76(6):947–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dzakhov SD, Kurochkin I. Supramalleolar osteotomies in children and adolescents. Ortop Travmatol Protez. 1966;27(12):41–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barskii AV, Semenov NP. Methods of the supramalleolar osteotomy in ununited fractures of the malleoli. Ortop Travmatol Protez. 1979;7:54–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Speed JS, Boyd HB. Operative reconstruction of malunited fractures about the ankle joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1936;18(2):270–86. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pagenstert G, Knupp M, Valderrabano V, et al. Realignment surgery for valgus ankle osteoarthritis. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2009;21(1):77–87. doi: 10.1007/s00064-009-1607-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knupp M, Pagenstert G, Valderrabano V, et al. Osteotomies in varus malalignment of the ankle. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2008;20(3):262–73. doi: 10.1007/s00064-008-1308-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hintermann B, Knupp M, Barg A. Joint-preserving surgery of asymmetric ankle osteoarthritis with peritalar instability. Foot Ankle Clin. 2013;18(3):503–16. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hintermann B, Knupp M, Barg A. Peritalar instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(5):450–4. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barg A, Pagenstert GI, Hugle T, et al. Ankle osteoarthritis: etiology, diagnostics, and classification. Foot Ankle Clin. 2013;18(3):411–26. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng YM, Huang PJ, Hong SH, et al. Low tibial osteotomy for moderate ankle arthritis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2001;121(6):355–8. doi: 10.1007/s004020000243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.•.Colin F, Bolliger L, Horn LT, et al. Effect of supramalleolar osteotomy and total ankle replacement on talar position in the varus osteoarthritic ankle: a comparative study. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35(5):445–52. doi: 10.1177/1071100713519779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colin F, Gaudot F, Odri G, et al. Supramalleolar osteotomy: techniques, indications and outcomes in a series of 83 cases. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(4):413–8. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ellington JK, Myerson MS. Surgical correction of the ball and socket ankle joint in the adult associated with a talonavicular tarsal coalition. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34(10):1381–8. doi: 10.1177/1071100713488762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gessmann J, Seybold D, Baecker H, et al. Correction of supramalleolar deformities with the Taylor spatial frame. Z Orthop Unfall. 2009;147(3):314–20. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harstall R, Lehmann O, Krause F, et al. Supramalleolar lateral closing wedge osteotomy for the treatment of varus ankle arthrosis. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28(5):542–8. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hintermann B, Barg A, Knupp M. Corrective supramalleolar osteotomy for malunited pronation-external rotation fractures of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2011;93(10):1367–72. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B10.26944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knupp M, Barg A, Bolliger L, et al. Reconstructive surgery for overcorrected clubfoot in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(15):e1101–7. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee WC, Moon JS, Lee K, et al. Indications for supramalleolar osteotomy in patients with ankle osteoarthritis and varus deformity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(13):1243–8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neumann HW, Lieske S, Schenk K. Supramalleolar, subtractive valgus osteotomy of the tibia in the management of ankle joint degeneration with varus deformity. Oper Orthop Traumatol. 2007;19(5–6):511–26. doi: 10.1007/s00064-007-1025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pagenstert GI, Hintermann B, Barg A, et al. Realignment surgery as alternative treatment of varus and valgus ankle osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;462:156–68. doi: 10.1097/BLO.0b013e318124a462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stamatis ED, Cooper PS, Myerson MS. Supramalleolar osteotomy for the treatment of distal tibial angular deformities and arthritis of the ankle joint. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24(10):754–64. doi: 10.1177/107110070302401004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Takakura Y, Takaoka T, Tanaka Y, et al. Results of opening-wedge osteotomy for the treatment of a post-traumatic varus deformity of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80(2):213–8. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199802000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tanaka Y, Takakura Y, Hayashi K, et al. Low tibial osteotomy for varus-type osteoarthritis of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2006;88(7):909–13. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B7.17325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barg A, Paul J, Pagenstert GI, et al. Supramalleolar osteotomies for ankle osteoarthritis. Tech Foot Ankle. 2013;12:138–46. doi: 10.1097/BTF.0b013e31829337b8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gloyer M, Barg A, Horisberger M, et al. Sprunggelenknahe osteotomien bei valgus- nd varusarthrose. Fuss Sprungg. 2013;11:186–95. doi: 10.1016/j.fuspru.2013.09.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pagenstert G, Leumann A, Hintermann B, et al. Sports and recreation activity of varus and valgus ankle osteoarthritis before and after realignment surgery. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29(10):985–93. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2008.0985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Valderrabano V, Miska M, Leumann A, et al. Reconstruction of osteochondral lesions of the talus with autologous spongiosa grafts and autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(3):519–27. doi: 10.1177/0363546513476671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wiewiorski M, Barg A, Valderrabano V. Autologous matrix-induced chondrogenesis in osteochondral lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Clin. 2013;18(1):151–8. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2012.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Barg A, Elsner A, Anderson AE, et al. The effect of three-component total ankle replacement malalignment on clinical outcome: pain relief and functional outcome in 317 consecutive patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(21):1969–78. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cenni F, Leardini A, Cheli A, et al. Position of the prosthesis components in total ankle replacement and the effect on motion at the replaced joint. Int Orthop. 2012;36(3):571–8. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1323-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Espinosa N, Walti M, Favre P, et al. Misalignment of total ankle components can induce high joint contact pressures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(5):1179–87. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.00287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tochigi Y, Rudert MJ, Brown TD, et al. The effect of accuracy of implantation on range of movement of the Scandinavian Total Ankle Replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2005;87(5):736–40. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B5.14872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lee JJ, Patel R, Biermann JS, et al. The musculoskeletal effects of cigarette smoking. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(9):850–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saltzman CL, el Khoury GY. The hindfoot alignment view. Foot Ankle Int. 1995;16(9):572–6. doi: 10.1177/107110079501600911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Knupp M, Pagenstert GI, Barg A, et al. SPECT-CT compared with conventional imaging modalities for the assessment of the varus and valgus malaligned hindfoot. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(11):1461–6. doi: 10.1002/jor.20922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pagenstert GI, Barg A, Leumann AG, et al. SPECT-CT imaging in degenerative joint disease of the foot and ankle. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) 2009;91(9):1191–6. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B9.22570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Inman VT. The joints of the ankle. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Knupp M, Ledermann H, Magerkurth O, et al. The surgical tibiotalar angle: a radiologic study. Foot Ankle Int. 2005;26(9):713–6. doi: 10.1177/107110070502600909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cobey JC. Posterior roentgenogram of the foot. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;118:202–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Donovan A, Rosenberg ZS. Extra-articular lateral hindfoot impingement with posterior tibial tendon tear: MRI correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193(3):672–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.08.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sangeorzan BP, Judd RP, Sangeorzan BJ. Mathematical analysis of single-cut osteotomy for complex long bone deformity. J Biomech. 1989;22(11–12):1271–8. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(89)90230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stufkens SA, Barg A, Bolliger L, et al. Measurement of the medial distal tibial angle. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32:288–93. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2011.0288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Warnock KM, Johnson BD, Wright JB, et al. Calculation of the opening wedge for a low tibial osteotomy. Foot Ankle Int. 2004;25(11):778–82. doi: 10.1177/107110070402501104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hintermann B, Knupp M, Barg A. Osteotomies of the distal tibia and hindfoot for ankle realignment. Orthopade. 2008;37(3):212–3. doi: 10.1007/s00132-008-1214-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mann HA, Filippi J, Myerson MS. Intra-articular opening medial tibial wedge osteotomy (plafond-plasty) for the treatment of intra-articular varus ankle arthritis and instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33(4):255–61. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Best A, Daniels TR. Supramalleolar tibial osteotomy secured with the Puddu plate. Orthopedics. 2006;29(6):537–40. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20060601-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Horn DM, Fragomen AT, Rozbruch SR. Supramalleolar osteotomy using circular external fixation with six-axis deformity correction of the distal tibia. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(10):986–93. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2011.0986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Knupp M, Stufkens SA, Pagenstert GI, et al. Supramalleolar osteotomy for tibiotalar varus malalignment. Tech Foot Ankle. 2009;8:17–23. doi: 10.1097/BTF.0b013e31818ee7b4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee KB, Cho YJ. Oblique supramalleolar opening wedge osteotomy without fibular osteotomy for varus deformity of the ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30(6):565–7. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2009.0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]