Abstract

Aberrant signaling of the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK (MAP kinase) pathway driven by the mutant kinase BRAFV600E, as a result of the BRAFT1799A mutation, plays a fundamental role in thyroid tumorigenesis. This study investigated the therapeutic potential of a BRAFV600E-selective inhibitor, PLX4032 (RG7204), for thyroid cancer by examining its effects on the MAP kinase signaling and proliferation of 10 thyroid cancer cell lines with wild-type BRAF or BRAFT1799A mutation. We found that PLX4032 could effectively inhibit the MAP kinase signaling, as reflected by the suppression of ERK phosphorylation, in cells harboring the BRAFT1799A mutation. PLX4032 also showed a potent and BRAF mutation-selective inhibition of cell proliferation in a concentration-dependent manner. PLX4032 displayed low IC50 values (0.115– 1.156 μM) in BRAFV600E mutant cells, in contrast with wild-type BRAF cells that showed resistance to the inhibitor with high IC50 values (56.674–1349.788 μM). Interestingly, cells with Ras mutations were also sensitive to PLX4032, albeit moderately. Thus, this study has confirmed that the BRAFT1799A mutation confers cancer cells sensitivity to PLX4032 and demonstrated its specific potential as an effective and BRAFT1799A mutation-selective therapeutic agent for thyroid cancer.

Keywords: Thyroid cancer, PLX4032, RG7204, BRAF mutation, BRAF inhibitor, Genetic-dependent therapy

1. Introduction

Thyroid cancer is a common endocrine malignancy, which has seen a rapid rise in incidence in recent years, with 44,670 new cases and 1690 deaths estimated for the year 2010 in the United States [1]. Follicular epithelial cell-derived thyroid cancer histologically consists mainly of papillary thyroid cancer (PTC), follicular thyroid cancer (FTC), and anaplastic thyroid cancer (ATC) [2]. PTC is the most common type of thyroid cancer, accounting for 80% of all thyroid cancers. ATC is relatively uncommon but is a rapidly aggressive and lethal cancer. Although PTC, as a differentiated cancer, is usually curable in most patients with current surgical and radioiodine treatments, many cases of patients with this cancer fail these standard treatments. Therefore, new treatments are needed for patients currently with incurable thyroid cancer.

Among different thyroid cancers, the BRAFT1799A mutation is exclusively found in PTC and ATC, occurring in 45% of cases of the former and 25% of cases of the latter [3]. This mutation leads to an amino acid change from valine to glutamic acid in position 600 of the BRAF protein kinase, resulting in the constitutively activated BRAFV600E mutant. BRAFV600E causes constant activation of the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway (MAP kinase pathway). MAP kinase pathway normally regulates a variety of molecular and cellular functions, including cell proliferation and growth. By over-activating this pathway, BRAFV600E plays an important role in the pathogenesis and aggressiveness of thyroid cancer [4,5]. Thus, BRAF has become a popular target in the pursuit of new treatments for thyroid cancers [6].

BRAF inhibitors that were developed to selectively target BRAFV600E for treatment of human cancers have recently received particular attention [7]. These BRAFV600E-selective inhibitors are small-molecule ATP-competitive kinase inhibitors. They were shown to potently inhibit melanoma cells harboring the BRAFT1799A mutation, much less so in melanoma cells harboring the wild-type BRAF gene [8,9]. Recent clinical studies reported exciting results on the therapeutic effects of BRAFV600E-selective inhibitors in melanoma, as exemplified by PLX4032 [10,11]. Given the common occurrence of BRAFT1799A mutation in thyroid cancer, it is expected that these inhibitors may also be effective drugs to treat patients with thyroid cancer harboring this mutation. In this study, we investigated the therapeutic potential of PLX4032 for thyroid cancer by examining its BRAFT1799A mutation-dependent inhibition of the MAP kinase pathway and the proliferation of thyroid cancer cells.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell cultures

Ten human thyroid cancer cell lines were used in this study, including OCUT1 originally from Dr. Naoyoshi Onoda (Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka, Japan); C643, Hth7, Hth74, and SW1736 from Dr. N.E. Heldin (University of Uppsala, Uppsala, Sweden); FTC133 from Dr. Georg Brabant (University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom); K1 from Dr. David Wynford-Thomas (University of Wales College of Medicine, Cardiff, United Kingdom); KAT18 from Dr. Kenneth B. Ain (University of Kentucky Medical Center, Lexington, KY); WRO-82-1 from Dr. G.J.F. Juillard (University of California-Los Angeles School of Medicine, Los Angeles, CA); and BCPAP from Dr. Massimo Santoro (University of Federico II, Naples, Italy). These cells could be divided into three groups: Group I – OCUT1, SW1736, K1, and BCPAP harboring the BRAFT1799A mutation; Group II – FTC133, KAT18, Hth74, and WRO harboring neither BRAF mutation nor Ras mutations; and Group III – C643 and Hth7 harboring Ras mutations. Except for FTC133, these cells were normally cultured and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium at 37 °C and 5% CO2, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 5% sodium pyruvate, 5% MEM nonessential amino acids, and 5% penicillin streptomycin. FTC133 cells were cultured in DMEM/HAM’S F-12 medium instead. When cells were treated with PLX4032 (Plexxikon Inc., Berkeley, CA 94710), 5% FBS was used in the medium instead of 10%.

2.2. Western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer containing 1% phenylmethylsul-fonyl fluoride, 1% protease inhibitor cocktail, and 1% sodium orthovanadate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Cell lysates were kept on ice during the procedure and proteins were quantified using a spectrophotometer. Protein samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 10% acrylamide, followed by transfer onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscata-way, NJ). The PVDF membranes were then blotted with primary antibodies anti-phospho-ERK (sc-7383), anti-ERK1 (sc-94), or anti-Actin (sc-1616-R) (all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Membranes were subsequently washed with PBS-T and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit (sc-2204) or anti-mouse (sc-2005) secondary antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Signals were visualized using a chemilucent enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

2.3. Cell proliferation assay

Thyroid cancer cells grown in attachment to flask wall were freed by trypsin-EDTA treatment and resuspended in culture medium containing 10% FBS. An aliquot of 800 cells was transferred and seeded onto wells in triplicates on 96-well plates. During a 5-day treatment, cells were treated with 7 different concentrations of the BRAFV600E-selective inhibitor PLX4032, including 0, 0.01, 0.03, 0.10, 0.30, 1.00, and 3.00 μM under standard culture conditions. The culture medium containing the inhibitor at the required concentrations was replenished daily. During the treatment with PLX4032, medium was changed to contain 5% FBS, instead of 10%.

Cell proliferation was measured using the colorimetric 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Briefly, after 5 days of treatment with PLX4032, 10 μL of 5 mg/mL MTT agent (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA) was added to cells with a 4-h incubation. This was followed by an overnight incubation with 100 μL of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate solution. This led to the creation of purple crystals in the mitochondria of cells, which were then dissolved in the medium. Spectrophotometry was performed to measure the absorbance at the test wavelength of 570 nm and the reference wavelength of 670 nm. Relative cell growth was reflected by the intensity of the purple color. IC50 values of PLX4032 were calculated for each cell line using a computer program based on the classical Reed-Muench method [12].

3. Results

3.1. BRAFT1799A-dependent inhibition of the MAP kinase pathway signaling by the BRAFV600E inhibitor PLX4032

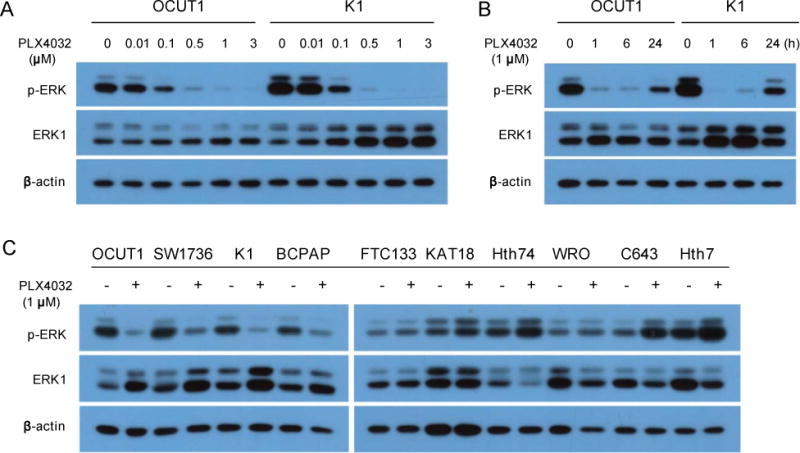

Phosphorylation of ERK is a key step down stream of BRAF and MEK in the signaling of the MAP kinase pathway and is widely used as a measure of the signaling activity of this pathway. We therefore examined the effect of the BRAFV600E inhibitor PLX4032 on the phosphorylation of ERK (p-ERK) in thyroid cancer cell lines. As shown in Fig 1A in both OCUT1 and K1 cells, which harbored the BRAFT1799A mutation, PLX4032 potently inhibited p-ERK; significant inhibition was seen at 0.1 μM and nearly complete inhibition was seen at 0.5 μM. This effect of PLX4032, as shown in Fig 1B, was quick; complete inhibition occurred within 1 h after the addition of the inhibitor and significant inhibition remained at 24 h. As shown in Fig 1C, p-ERK in the BRAF mutation-harboring SW1736 and BCPAP cells was also inhibited by PLX4032. In the BRAF mutation-negative cells, including FTC133, KAT18, Hth74, and WRO cells, PLX4032 did not show significant effect on p-ERK. PLX4032 paradoxically had a stimulatory effect on p-ERK in C643 and Hth7 cells that harbored Ras mutations (Fig 1C). This paradoxical activation of MAP kinase pathway by PLX4032 was consistent with the finding of similar stimulatory effects of BRAFV600E inhibitors on the MAP kinase pathway in other cancer cells harboring Ras mutations, which was hypothesized to be due to Ras activity-facilitated transactivation of RAF dimers [13].

Fig. 1.

Effects of the BRAFV600E inhibitor PLX4032 on ERK phosphorylation in thyroid cancer cells. (A) Concentration-dependent responses of PLX4032 in OCUT1 and K1 cells. Cells were treated with PLX4032 at the indicated concentrations for 6 h in culture medium containing 5% FBS. Cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies specific to phospho-ERK (p-ERK), ERK1, and β-actin. ERK1 and β-actin were analyzed simultaneously for quality control of proteins. (B) Time-dependent response of the effects of PLX4032 in OCUT1 and K1 cells. Cells were treated with PLX4032 at 1 μM for the indicated times and Western blotting assay was performed as in Fig 1 A. (C) Effects of PLX4032 on p-ERK in the remaining thyroid cancer cells. Cells were treated with PLX4032 at 1 μM for 24 h. Western blotting assay was performed as in Fig 1A.

3.2. BRAFT1799A-dependent inhibition of the proliferation of thyroid cancer cells by the BRAFV600E inhibitor PLX4032

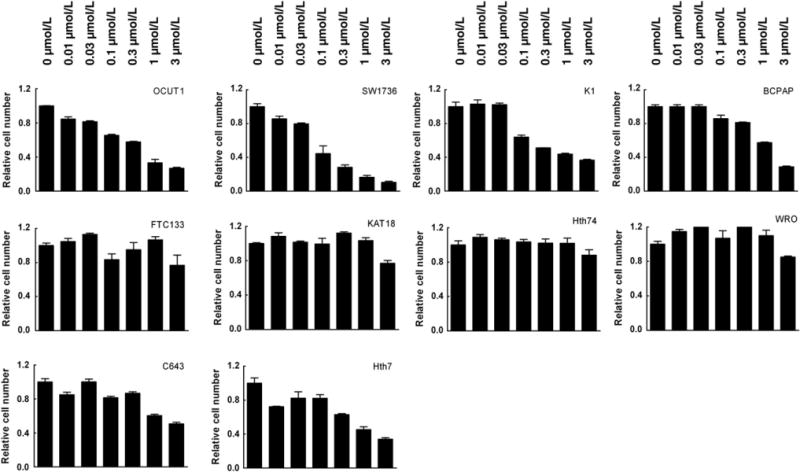

As the BRAFV600E inhibitor PLX4032 could effectively inhibit the signaling of the MAP kinase pathway in BRAFT1799A cells, as presented above, we next examined the effects of this drug on the proliferation of thyroid cancer cells. As shown in Fig 2, thyroid cancer cell lines OCUT1, SW1736, K1, and BCPAP that harbored the BRAF-T1799A mutation were effectively inhibited by PLX4032 in a dose-dependent manner. This inhibition was very potent as reflected by low IC50 values, ranging from 0.1149 to 1.156 μM (Table 1). For comparison, we tested the thyroid cancer cells that did not have BRAFT1799A mutation, including FTC133, KAT18, Hth74, and WRO cells. As shown in Fig 2, these cells resisted the inhibition by PLX4032. This resistance was well reflected by high IC50 values in these cells, ranging from 56.674 to 1349.788 μM (Table 1). We also tested C643 and Hth7 cells that did not harbor the BRAFT1799A mutation but harbored Ras mutations. As shown in Fig 2, these two cells showed much better responses to PLX4032 than the cells (FTC133, KAT18, and WRO) that did not harbor BRAF or Ras mutations. This was also reflected by the much lower IC50 values in the former cells than the latter cells (Table 1). The mechanism for the differential effects of PLX4032 on cell proliferation (Fig 2 and Table 1) and ERK phosphorylation (Fig 1) in Ras mutation-harboring cells is not clear. However, the responses of the two Ras mutation-harboring cells to PLX4032 were relatively modest compared with the cells harboring the BRAFT1799A mutation, with IC50 values in the former being several times to 25 times higher than the latter (Table 1).

Fig. 2.

BRAFT1799A mutation-dependent inhibition of thyroid cancer cells by the BRAFV600E inhibitor PLX4032. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of PLX4032 for 5 days with the drug replenished daily by changing the culture medium containing 5% FBS. MTT assay of cell proliferation was performed at the end of the 5-day treatment Cells in the upper row harbor the BRAFT1799A mutation, cells in the lower row harbor Ras mutations, and cells in the middle row are wild-type, harboring neither BRAF nor Ras mutations. The values on the y-axis represent the relative cell growth rate, with control growth (in the absence of the drug) being defined as 1.

Table 1.

Mutation status of thyroid cancer cell lines and their sensitivities to the BRAFV600E inhibitor PLX4032 – IC50 Values.

| Cell Lines | Genetic Alterations | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| OCUT1 | BRAF(V600E+/−) | 0.410 |

| SW1736 | BRAF(V600E+/−) | 0.115 |

| K1 | BRAF(V600E+/−) | 0.827 |

| BCPAP | BRAF(V600E+/+) | 1.156 |

| FTC133 | – | 56.674 |

| KAT18 | – | 541.660 |

| Hth74 | – | 1349.788 |

| WRO | – | 943.728 |

| C643 | HRAS(G13R+/−) | 2.896 |

| Hth7 | NRAS(Q61R+/−) | 0.973 |

+/−, heterozygous mutation; +/+, homozygous mutation.

4. Discussion

Genetic-based cancer therapy targeting specific mutations has become an increasingly recognized effective therapeutic strategy for many human cancers [14–16], including thyroid cancer [17]. Given the common occurrence of the BRAFT1799A mutation and its important oncogenic role in thyroid cancer pathogenesis and aggressiveness [4,5], in this study, we tested the hypothesis that inhibitors of BRAFV600E, the resulting BRAF mutant of the BRAFT1799A mutation, might be particularly effective in inhibiting thyroid cancer cells harboring the BRAFT1799A mutation and may thus be used for BRAF mutation-targeted therapy for thyroid cancer. We found that, in comparison with thyroid cancer cells harboring the wild-type BRAF gene, thyroid cancer cells harboring the BRAFT1799A mutation responded far more effectively to the BRAFV600E inhibitor PLX4032 in the inhibition of the signaling of the MAP kinase pathway. Correspondingly, proliferation of thyroid cancer cells harboring the BRAF mutation was more potently and efficaciously inhibited by PLX4032 with much lower IC50 values, in nano molar to low micro molar ranges, in striking contrast with cells harboring no mutations. These data sufficiently and effectively demonstrated a high BRAFT1799A mutation-selective sensitivity of thyroid cancer cells to PLX4032, consistent with its expected function as a BRAFV600E-selective BRAF inhibitor. Our results are very similar to the findings reported recently on the effects of BRAFV600E inhibitors on melanoma cells [8,9]. The results in this study on the BRAFT1799A-dependent effects of PLX4032 are also consistent with the results in a recent study by Salerno et al. on PLX4032 in thyroid cancer cells [18]. This study included a number of different thyroid cancer cell lines than the Salerno et al. study [18] and still showed the BRAFT1799A dependency of PLX4032, further demonstrating the BRAFT1799A-dependent therapeutic potential of BRAFV600E inhibitors for thyroid cancer.

In this study, the two Ras mutation-harboring cells, C643 and Hth7, showed less sensitivity to PLX4032 than BRAFT1799A mutation-harboring cells (OCUT1, SW1736, K1, and BCPAP). But the response was more potent than the wild-type cells – cells without BRAF mutation or Ras mutations (FTC133, KAT18, Hth74, and WRO). This seems to be somewhat different than the conclusion on PLX4032 in these two cells in the Salerno et al. study [18], in which the authors stated that these Ras mutation-harboring cells did not respond to PLX4032. On closer examination of the Salerno et al. study [18], however, it is clear that at a concentration of around 0.5 μM at four days of treatment, PLX4032 did show a visible inhibitory effect on the Ras mutation-harboring cells; at the highest concentration −1.0 μM used in the Salerno et al. study [18], PLX4032 had a further inhibitory effect on these cells. These results, in fact, seemed to be consistent with the findings in this study at similar drug concentrations (Fig 2). In this study, at the additional concentration point of 3.0 μM, PLX4032 caused a further inhibition, with relatively low IC50 values calculated for these two Ras mutation-harboring cells (Table 1). The inhibition in these cells by PLX4032 did not seem to be attributable to a non-specific effect as this inhibition was not as significant in the wild-type cells (FTC133, KAT18, Hth74, and WRO) at the same drug concentrations, particularly at 0.30 and 1.00 μM (Fig 2). It is noticeable that the treatment duration of cells with PLX4032 in the Salerno et al. study [18] was 4 days, while our drug treatment duration was longer (5 days). This may be a reason that we observed a more remarkable inhibition of the two Ras mutation-harboring cells by PLX4032, particularly at concentration points 0.30, 1.00, and 3.00 μM(Fig 2). It has been reported that melanoma cells and other cancer cells harboring Ras mutations did not respond to BRAFV600E inhibitors [9,13]. It would be interesting to investigate the molecular mechanisms to explain why proliferation of some of the thyroid cancer cells harboring Ras mutations could be inhibited by PLX4032, albeit relatively modestly.

In summary, this study demonstrates that the BRAFv600E-selective inhibitor PLX4032 can selectively inhibit thyroid cancer cells that harbor the BRAFT1799A mutation. Both qualitative and quantitative data support the high effectiveness and potency of PLX4032 in inhibiting thyroid cancer cells harboring the BRAFT1799A mutation. Thus, the BRAFT1799A mutation confers thyroid cancer cells a significant sensitivity to PLX4032. Together with previous studies, this study provides strong implications for a therapeutic opportunity for PLX4032 as an effective drug for currently incurable types of PTC and ATC that harbor the BRAFT1799A mutation. Given the recent strong clinical data that demonstrated remarkable therapeutic effects of BRAFV600E inhibitors in melanoma patients [10,11 ], the present preclinical study supports the pursuit of a clinical trial on PLX4032 in thyroid cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

We thank Plexxikon Inc. (Berkeley, CA) for providing us PLX4032. We also thank Drs. Heldin N.E., Ain K.B., Onoda N., Wynford-Thomas D., Brabant G., and Juillard G.J. for kindly providing us the accessibility to the cell lines used in this study. Mr. Ermal Bojdani and Ms. Barbara Jewett are also greatly appreciated for their help and support. This study was supported by a grant from the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute to B. Trink.

References

- 1.Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Ruhl J, Howlader N, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Cronin K, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK, editors. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2007. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2010. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007/, based on November 2009 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hundahl SA, Fleming ID, Fremgen AM, Menck HR. A National Cancer Data Base report on 53, 856 cases of thyroid carcinoma treated in the U.S., 1985–1995. Cancer. 1998;83:2638–2648. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981215)83:12<2638::aid-cncr31>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xing M. BRAF mutation in thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2005;12:245–262. doi: 10.1677/erc.1.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xing M. BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid cancer: pathogenic role, molecular bases, and clinical implications. Endocr Rev. 2007:742–762. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang KT, Lee CH. BRAF mutation in papillary thyroid carcinoma: pathogenic role and clinical implications. J Chin Med Assoc. 2010;73:113–128. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(10)70025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li HF, Chen Y, Rao SS, Chen XM, Liu HC, Qin JH, Tang WF, Yue-Wang, Zhou X, Lu T. Recent advances in the research and development of B-Raf inhibitors. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:1618–1634. doi: 10.2174/092986710791111242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smalley KS. PLX-4032, a small-molecule B-Raf inhibitor for the potential treatment of malignant melanoma. Curr Opin Invest Drugs. 2010;11:699–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tsai J, Lee JT, Wang W, Zhang J, Cho H, Mamo S, Bremer R, Gillette S, Kong J, Haass NK, Sproesser K, Li L, Smalley KS, Fong D, Zhu YL, Marimuthu A, Nguyen H, Lam B, Liu J, Cheung I, Rice J, Suzuki Y, Luu C, Settachatgul C, Shellooe R, Cantwell J, Kim SH, Schlessinger J, Zhang KY, West BL, Powell B, Habets G, Zhang C, Ibrahim PN, Hirth P, Artis DR, Herlyn M, Bollag G. Discovery of a selective inhibitor of oncogenic B-Raf kinase with potent antimelanoma activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3041–3046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711741105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joseph EW, Pratilas CA, Poulikakos PI, Tadi M, Wang W, Taylor BS, Halilovic E, Persaud Y, Xing F, Viale A, Tsai J, Chapman PB, Bollag G, Solit DB, Rosen N. The RAF inhibitor PLX4032 inhibits ERK signaling and tumor cell proliferation in a V600E BRAF-selective manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:14903–14908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008990107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flaherty KT, Puzanov I, Kim KB, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Sosman JA, O’Dwyer PJ, Lee RJ, Grippo JF, Nolop K, Chapman PB. Inhibition of mutated, activated BRAF in metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:809–819. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bollag G, Hirth P, Tsai J, Zhang J, Ibrahim PN, Cho H, Spevak W, Zhang C, Zhang Y, Habets G, Burton EA, Wong B, Tsang G, West BL, Powell B, Shellooe R, Marimuthu A, Nguyen H, Zhang KY, Artis DR, Schlessinger J, Su F, Higgins B, Iyer R, D’Andrea K, Koehler A, Stumm M, Lin PS, Lee RJ, Grippo J, Puzanov I, Kim KB, Ribas A, McArthur GA, Sosman JA, Chapman PB, Flaherty KT, Xu X, Nathanson KL, Nolop K. Clinical efficacy of a RAF inhibitor needs broad target blockade in BRAF-mutant melanoma. Nature. 2010;467(7315):596–599. doi: 10.1038/nature09454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welkos S, O’Brien A. Determination of median lethal and infectious doses in animal model systems. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:29–39. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Poulikakos PI, Zhang C, Bollag G, Shokat KM, Rosen N. RAF inhibitors transactivate RAF dimers and ERK signalling in cells with wild-type BRAF. Nature. 2010;464(7287):427–430. doi: 10.1038/nature08902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casado E, De Castro J, Belda-Iniesta C, Cejas P, Feliu J, Sereno M, González-Barón M. Molecular markers in colorectal cancer: genetic bases for a customised treatment. Clin Transl Oncol. 2007;9:549–554. doi: 10.1007/s12094-007-0102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang DZ, Kumar V, Ma Y, Li K, Kopetz S. Individualized therapies in colorectal cancer: KRAS as a marker for response to EGFR-targeted therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 2009;2:18. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-2-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heist RS, Christiani D. EGFR-targeted therapies in lung cancer: predictors of response and toxicity. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:59–68. doi: 10.2217/14622416.10.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xing M. Genetic-targeted therapy of thyroid cancer: a real promise. Thyroid. 2009;19:805–809. doi: 10.1089/thy.2009.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salerno P, De Falco V, Tamburrino A, Nappi TC, Vecchio G, Schweppe RE, Bollag G, Santoro M, Salvatore G. Cytostatic activity of adenosine triphosphate-competitive kinase inhibitors in BRAF mutant thyroid carcinoma cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:450–455. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]