Introduction

Genetic cancer risk assessment has an integral role in helping patients understand their hereditary risk, facilitates their decisions about genetic testing, and often aids in their management (1-8). Ovarian cancer, the leading cause of death from gynecologic cancer, has one of the highest fractions attributable to inherited risks compared to other common solid tumors (9). Genetic testing is now available for many genes responsible for hereditary ovarian cancer, including BRCA1 and BRCA2 which are estimated to account for approximately 15% of ovarian cancer cases (9-13) and Lynch syndrome implicated in 2% of cases (14). New sequencing approaches are identifying germ-line mutations in many other genes implicated in an additional 6% of ovarian cases, including BARD1, BRIP1, CHEK2, MRE11A, NBN, RAD50, MSH6, PALB2, RAD50, RAD51C, and TP53 (13).

Research suggests genetic testing be considered for all women with high-grade epithelial tumors or any serous ovarian cancer (10, 11, 15-17). The Society of Gynecologic Oncologists (SGO) endorses referral of these high-risk patients (2), whereas current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend that all women with epithelial ovarian cancer be referred for genetic counseling (18). However, physicians continue to under-refer and women to under-use genetic services (10, 16), which has generated research aimed at increasing patients’ use of risk assessment (19-24). Medical providers have an important role in referring cancer patients who might benefit the most from genetic assessment, but little is known about their patient selection and referral (25). Reported barriers to physicians’ referral for cancer genetics evaluation include limited hereditary cancer knowledge, lack of awareness of the availability of genetic services, physician training and the absence of anti-discrimination legislation (25, 26). The efficacy of interventions to increase medical providers’ referral has yet to be demonstrated.

Our primary objective was to increase the frequency of physician referrals for genetic counseling for HBOC and Lynch syndromes for women newly diagnosed with epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube (FT), and primary peritoneal (PP) cancer by implementing a systematically generated electronic referral focused on referral of patients deemed high risk according to the SGO guidelines. Within this paper, subsequence reference to ovarian, FT and PR cancers will be noted as ovarian cancer.

Materials and Methods

Following approval from the University of Minnesota's Institutional Review Board, retrospective chart review using ICD-9 codes identified 495 patients with epithelial ovarian cancer who were newly diagnosed, in remission or recurrent and seen by one of seven gynecologic oncologists from April 30, 2007 to April 30, 2009 in the Women's Cancer Center (WCC) at the University of Minnesota. The ICD-9 codes used for identification included 183.0 (malignant neoplasm of ovary), 183.2 (malignant neoplasm of fallopian tube), 158.8 (malignant neoplasm of specified parts of the peritoneum), V10.43 (personal history of malignant neoplasm of ovary). The gynecologic oncologists in the WCC do not directly order genetic testing, but refer patients for genetic counseling. Prior to the intervention, a hand-completed order was given to the genetic counselor in the clinic. A genetic counselor had been integrated into the WCC three years prior to the study based on oncologists’ knowledge about and value of genetic counseling. Such integration has been noted to result in more systematic referral, thereby increasing referrals (27).

On April 30, 2008, a referral form was introduced within the electronic medical record (EMR) (intervention) allowing oncologists to systematically refer patients directly to the Family Genetics Cancer Clinic for counseling. This form represents a one-page summary of SGO genetic referral guidelines for ovarian cancer in a checklist format which is automatically electronically forwarded when completed to the Cancer Genetics Clinic (Figure 1). No administrative cost was incurred in implementing this form. Date of the genetic counseling referral was defined as the date referral was discussed and documented in the EMR or the date of the electronic referral. Genetic counseling was defined as the date of the initial counseling visit. Data on patients seen during the time period before the intervention was initiated on April 30, 2007 and censored on April 30, 2008; a patient in the before intervention group only counted as being referred if she was referred prior to April 30, 2008. The data on patients seen after the intervention were censored on April 30, 2009. Subsequent referral outcome was followed in the EMR for all patients for a minimum of three years (through July 31, 2012).

Figure 1.

Electronic medical record genetic counseling referral form (intervention).

Additional EMR data collected included home zip code (to calculate distance from clinic), cancer diagnosis (ovarian and FT/PP), age at diagnosis, cancer stage (I-IV), tumor histology, personal/family cancer history, treating gynecologic oncologist and time since oncologist's fellowship (<10 years/≥10 years). A genetic counselor (A.L) reviewed personal/family cancer history, identified risk for a BRCA1, BRCA2, or Lynch syndrome, and placed patients in one of six familial cancer-risk categories: high, significant, potentially significant, insignificant, no family history of cancer, no information. Risk-stratification was based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines at the time of the study. For purposes of analysis, high and significant categories were combined.

All values are reported as percentages and mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless otherwise noted. The primary analysis compared patients seen before and after the implementation of the electronic genetic counseling referral form (intervention). Chi-squared tests and Fisher's exact tests were used as appropriate for categorical variables and t-tests were used for continuous variables.

A multiple logistic regression model was used to calculate the odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the likelihood of a referral for genetic counseling associated with the variables above. Because this was exploratory in nature, an optimal model was selected using backwards selection, keeping variables with p-values<0.10. P-values <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2.

Results

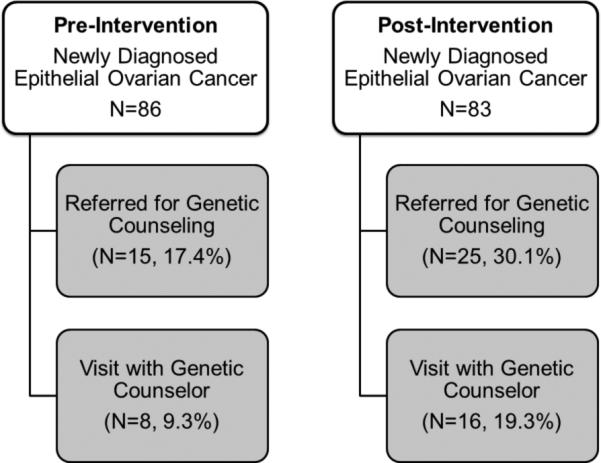

We included only the 169 (34%) ovarian cancer patients who were newly diagnosed during the study period (Figure 2). A summary of patient characteristics and descriptive statistics is available in Table 1. The mean age of the 169 eligible patients at diagnosis was 61.0 ± 12.7 years (range, 19-93).

Figure 2.

Summary of Patient Flow before and after intervention.

Table 1.

Characteristics for all newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients before and after intervention and factors predicting genetic referral (n=169).

| Overall | Before Intervention | After Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | P-value | |

| TOTAL | 169 | 86 | 50.89 | 83 | 49.11 | ||

| Genetic Referral | 0.053 | ||||||

| Yes | 40 | 23.67 | 15 | 17.44 | 25 | 30.12 | |

| No | 129 | 76.33 | 71 | 82.56 | 58 | 69.88 | |

| Region | 0.598 | ||||||

| Within 60 miles of Clinic | 89 | 52.66 | 47 | 54.65 | 42 | 50.60 | |

| Outside 60 miles of Clinic | 80 | 47.34 | 39 | 45.35 | 41 | 49.40 | |

| Cancer Stage | 0.257 | ||||||

| I | 26 | 15.38 | 9 | 10.47 | 17 | 20.48 | |

| II | 18 | 10.65 | 8 | 9.30 | 10 | 12.05 | |

| III | 76 | 44.97 | 43 | 50.00 | 33 | 39.76 | |

| IV | 37 | 21.89 | 18 | 20.93 | 19 | 22.89 | |

| Missing | 12 | 7.10 | 8 | 9.30 | 4 | 4.82 | |

| Primary Cancer Site | 0.103 | ||||||

| Ovarian | 136 | 80.47 | 65 | 75.58 | 71 | 85.54 | |

| FT/PP/Other | 33 | 19.53 | 21 | 24.42 | 12 | 14.46 | |

| Histology | 0.386 | ||||||

| Serous | 105 | 62.1 | 56 | 65.1 | 49 | 59.0 | |

| Endometrioid | 17 | 10.1 | 6 | 7.0 | 11 | 13.3 | |

| Other/Missing | 47 | 27.8 | 24 | 27.9 | 23 | 27.7 | |

| Previous Cancer Diagnosis | 0.569 | ||||||

| Yes | 26 | 15.38 | 14 | 16.28 | 12 | 14.46 | |

| No | 142 | 84.02 | 72 | 83.72 | 70 | 84.34 | |

| Unknown/Missing | 1 | 0.59 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 1.20 | |

| Family History Documented in Chart | 0.027 | ||||||

| Yes | 164 | 97.04 | 86 | 100.00 | 78 | 93.98 | |

| No | 5 | 2.96 | 0 | 0.00 | 5 | 6.02 | |

| Hereditary Risk of Cancer | 0.215 | ||||||

| High/Significant Risk | 44 | 26.04 | 24 | 27.91 | 20 | 24.10 | |

| Potentially Significant Risk | 44 | 26.04 | 21 | 24.42 | 23 | 27.71 | |

| Insignificant Risk | 36 | 21.30 | 19 | 22.09 | 17 | 20.48 | |

| No family history of cancer | 40 | 23.67 | 22 | 25.58 | 18 | 21.69 | |

| Unknown | 5 | 2.96 | 0 | 0.00 | 5 | 6.02 | |

| Doctor–Years from Fellowship | 0.864 | ||||||

| <10 years | 115 | 68.05 | 58 | 67.44 | 57 | 68.67 | |

| ≥10 years | 54 | 31.95 | 28 | 32.56 | 26 | 31.33 | |

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis | 168 | 61.1 (12.7) | 86 | 60.3 (12.9) | 83 | 62.0 (12.5) | 0.397 |

After the intervention, more patients were referred for genetic counseling (17% before vs. 30% after; p=0.053). Factors best predicting patient referral for genetic counseling included the intervention (p=0.009), hereditary risk of cancer (p<0.0001), and residing in the metro area (Table 2, p=0.006).

Table 2.

Multivariate Prediction of Patient Referral for Genetic Counseling among those with available family history (n=164).

| Variable | N | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Period | 0.009 | ||

| Before Intervention | 86 | 1.00 | |

| After Intervention | 78 | 3.32 (1.35, 8.17) | |

| Hereditary Risk of Cancer | <0.0001 | ||

| No significant history | 40 | 1.0 | |

| Insignificant history | 36 | 2.05 (0.31, 13.58) | |

| Potentially significant history | 44 | 7.21 (1.42, 36.52) | |

| High/significant risk | 44 | 34.40 (6.75, 175.42) | |

| Region | 0.006 | ||

| Outside 60 miles of Clinic | 76 | 1.00 | |

| Within 60 miles of Clinic | 88 | 3.59 (1.44, 8.96) |

Characteristics and descriptive statistics of referred patients pre- and post-intervention are in Table 3. Most referred patients lived in the metropolitan area (70%), had stage III-IV disease (58%), ovarian cancer (90%), were ≥50 years old at diagnosis (75%), did not have a prior cancer (73%), were at significant-to-high hereditary risk (88%), and saw a doctor <10 years from fellowship (68%). Among those referred, 60% saw a genetic counselor, 8 pre- and 16 post-intervention. None of the demographic and clinical characteristics considered differed pre/post intervention or between those who did/did not see a genetic counselor (data not shown).

Table 3.

Characteristics for newly diagnosed ovarian cancer patients before and after intervention among those referred for genetic counseling (n=40).

| Overall | Before Intervention | After Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | P-value | |

| TOTAL | 40 | 15 | 37.50 | 25 | 62.50 | ||

| Genetic Counselor Seen | 0.505 | ||||||

| Yes | 24 | 60.00 | 8 | 53.33 | 16 | 64.00 | |

| No | 16 | 40.00 | 7 | 46.67 | 9 | 36.00 | |

| Region | 0.152 | ||||||

| Within 60 miles of Clinic | 28 | 70.00 | 13 | 86.67 | 15 | 60.00 | |

| Outside 60 miles of Clinic | 12 | 30.00 | 2 | 13.33 | 10 | 40.00 | |

| Cancer Stage | 0.932 | ||||||

| I | 13 | 32.50 | 4 | 26.67 | 9 | 36.00 | |

| II | 4 | 10.00 | 2 | 13.33 | 2 | 8.00 | |

| III | 15 | 37.50 | 6 | 40.00 | 9 | 36.00 | |

| IV | 8 | 20.00 | 3 | 20.00 | 5 | 20.00 | |

| Histology | 0.514 | ||||||

| Serous | 27 | 67.5 | 11 | 73.3 | 16 | 64.0 | |

| Endometrioid | 3 | 7.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 12.0 | |

| Other/Missing | 10 | 25.0 | 4 | 26.7 | 6 | 24.0 | |

| Primary Cancer Site | 0.623 | ||||||

| Ovarian | 36 | 90.00 | 13 | 86.67 | 23 | 92.00 | |

| FT, PP, Other | 4 | 10.00 | 2 | 13.33 | 2 | 8.00 | |

| Age at Diagnosis | 0.715 | ||||||

| <50 years old | 10 | 25.00 | 3 | 20.00 | 7 | 28.00 | |

| ≥50 years old | 30 | 75.00 | 12 | 80.00 | 18 | 72.00 | |

| Previous Cancer Diagnosis | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 11 | 27.50 | 4 | 26.67 | 7 | 28.00 | |

| No | 29 | 72.50 | 11 | 73.33 | 18 | 72.00 | |

| Family history documented in chart | 1.00 | ||||||

| Yes | 40 | 100.00 | 15 | 100.00 | 25 | 100.00 | |

| No | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Hereditary Risk of Cancer | 0.580 | ||||||

| High/significant Risk | 24 | 60.00 | 9 | 60.00 | 15 | 60.00 | |

| Potentially Significant Risk | 11 | 27.50 | 5 | 33.33 | 6 | 24.00 | |

| Insignificant Risk | 3 | 7.50 | 0 | 0.00 | 3 | 12.00 | |

| No family history of cancer | 2 | 5.00 | 1 | 6.67 | 1 | 4.00 | |

| Doctor – Years from Fellowship | 0.931 | ||||||

| <10 years | 27 | 67.50 | 10 | 66.67 | 17 | 68.00 | |

| ≥10 years | 13 | 32.50 | 5 | 33.33 | 8 | 32.00 | |

To directly assess the effectiveness of the intervention, we looked at the rates of referral among the three indicators for risk-referral in our population as identified by the intervention/SGO guidelines: patients diagnosed at less than 50 years old (n=27), a previous cancer diagnosis (n=26) or high-risk family cancer history (n=44). We also looked at serous histology (n=105), an indicator suggested by many researchers. Prior to the intervention, 38% of patients with high-risk family cancer history were referred for genetic counseling whereas 75% were referred after the intervention (p=0.017). Among patients with a previous cancer diagnosis, 29% were referred before and 58% after the intervention (p=0.233). There was also an increase in the proportion of patients diagnosed at less than 50 years old being referred (23% vs. 50%; p=0.237) and an increase in the proportion of patients with serous histology being referred (41% vs. 59%; p=0.128).

Discussion

A stream-lined genetic counseling referral process prompted increased referral by oncologists for risk assessment of women newly diagnosed with ovarian cancer. In this fee-for-service clinic, in the one year prior to the intervention providers as a group were recording 100% of patients’ family histories and demonstrated an average provider group referral rate of 17% of newly diagnosed patients. The year following introduction of an electronic referral form the referral rate increased to 30% and an individual patient was over three times more likely to be referred.

The intended intervention outcome, increasing referrals, is valuable to the extent it represents identifying women at increased cancer risk for whom referral for genetic assessment might provide the most benefit. Our intervention significantly increased referral of women in increased-risk families, an indicator widely used for genetic testing. Diagnosis of ovarian cancer before age 50, a cancer diagnosis prior to ovarian cancer, and serous histology are also indicators for risk-assessment and while post-intervention referrals for these women increased, it was not statistically significant, possibly due to the small sample size.

In this study, referral rates pre-intervention (17%) were higher than rates reported in earlier studies. This is possibly due to the oncologists’ knowledge about and access to genetic counseling, the lack of both which have been cited as barriers to physician referral (25), and to improved referral practices based on changing referral guidelines. For example, in 2001 Culver et al. (21) reported an 11% referral rate for genetic services by oncologists treating a variety of hereditary cancers; as many as 76% were interested in referring but reported many barriers.

We found that patients living greater than 60 miles from the clinic (a proxy for urban vs. rural residence in our population) were less likely to be referred. Living in rural areas has been described as a patient-related barrier to risk assessment, purportedly reflecting lack of service access away from cancer centers (1). Women living in urban vs. rural settings notably have fewer negative cancer attitudes (28) and might be more comfortable asking about cancer genetics. Patients’ asking about and appearing interested in genetic services predicts its use by physicians (26, 27). Besides rural residency, other physician referral barriers in this setting may have included timing, with some oncologists preferring to wait until treatment has been completed. Additionally, historical barriers include patients’ concerns about cost of services, fear of results negatively affecting them or family members, and/or knowing family members disapprove of genetic services for cancer risk (29, 30).

In our study, 40% of those referred did not see a genetic counselor. A patient's decision not to pursue a referral is a personal choice (19). Both patient and physician awareness of uptake barriers, however, might prevent unnecessary deterrents to counseling and improve overall uptake of genetic services (20). While outside the focus of this study, other research suggests prominent reasons at-risk cancer patients decline genetic services include not seeing such services as beneficial, the emotional impact on self or family, family objections, concern over health insurability, cost, lower education level and time commitment (21, 22, 29). Many women with ovarian cancer also prefer meeting with a genetic counselor after completing chemotherapy (31). In the United States, the cost for BRCA1/2 mutation testing usually ranges from several hundred to several thousand dollars. Insurance policies vary with regard to whether or not the cost is covered (32).

In the future, the availability of treatment-focused genetic testing (TFGT) for women with ovarian cancer may increase provider referral rates for counseling/testing and women's uptake. Preliminary studies suggest women with ovarian cancer perceive a range of advantages associated with TFGT, including the potential for individualized treatment and greater information on which to base treatment decisions (33). The growing availability of lower cost genetic testing in the United States with its accompanying promise of personalized genomic information (34) and celebrity public disclosures of cancer genetic testing results, including Angelina Jolie, additionally may influence patient uptake for at-risk women (35). However, barriers to medical decisions for both providers and patients regarding cancer genetics and genetic services are likely to continue, influenced by nuanced considerations associated with individualized risk factors; personal, emotional and practical considerations; and family and educational issues.

Results should be interpreted in light of study limitations. This was not a randomized trial and our results might reflect a difference in the patient population pre- and post-intervention that we did not measure or a change in referral over time independent of the intervention. The study was conducted in an academic setting with only newly diagnosed patients included, representing neither a cross section of providers nor of at-risk women. Providers in other settings might not have access to an EMR, genetic services, or feel qualified to recommend testing (25, 26), all barriers to applying our intervention. While there are no standard recommended guidelines regarding timing of referral for genetic risk assessment for women with ovarian cancer, some providers also might not recommend genetic counseling until more time has elapsed since diagnosis concerned genetic testing may add too much additional stress (36, 37). Others, however, such as Daniels et al., (2009) advocate for referral at the time of initial diagnosis and treatment given the often poor prognosis (38). It is important that future research of provider referral rates include women from diverse backgrounds, community settings, and points-in-treatment.

We have demonstrated that a computer-based intervention appears to be a low riskcost, potentially high reward approach to increasing provider referral rates. These results offer evidence of the efficacy of system interventions targeting providers to significantly increase genetic referrals which, in turn, may lead to improved cancer genetic risk assessment. Further study is needed to develop methods for increasing referral rates in an ovarian cancer population, as current recommendations suggest that all women with epithelial ovarian cancer should be considered for genetic counseling (18).

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by NIH grant P30 CA77598 utilizing the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Core shared resource of the Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota and by the by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR000114.

REFERENCES

- 1.Weitzel JN, Blazer KR, Macdonald DJ, et al. Genetics, genomics, and cancer risk assessment: State of the Art and Future Directions in the Era of Personalized Medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011 doi: 10.3322/caac.20128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lancaster JM, Powell CB, Kauff ND, et al. Society of Gynecologic Oncologists Education Committee statement on risk assessment for inherited gynecologic cancer predispositions. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:159–62. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botkin JR, Smith KR, Croyle RT, et al. Genetic testing for a BRCA1 mutation: prophylactic surgery and screening behavior in women 2 years post testing. American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2003;118A:201–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meiser B, Tucker K, Friedlander M, et al. Genetic counselling and testing for inherited gene mutations in newly diagnosed patients with breast cancer: a review of the existing literature and a proposed research agenda. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:216. doi: 10.1186/bcr2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pieterse AH, Ausems MG, Van Dulmen AM, et al. Initial cancer genetic counseling consultation: change in counselees' cognitions and anxiety, and association with addressing their needs and preferences. American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2005;137:27–35. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zon RT, Goss E, Vogel VG, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement: the role of the oncologist in cancer prevention and risk assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:986–93. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robson ME, Storm CD, Weitzel J, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update: genetic and genomic testing for cancer susceptibility. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:893–901. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheuer L, Kauff N, Robson M, et al. Outcome of preventive surgery and screening for breast and ovarian cancer in BRCA mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1260–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prat J, Ribe A, Gallardo A. Hereditary ovarian cancer. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:861–70. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alsop K, Fereday S, Meldrum C, et al. BRCA Mutation Frequency and Patterns of Treatment Response in BRCA Mutation-Positive Women With Ovarian Cancer: A Report From the Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2654–63. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.8545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pal T, Permuth-Wey J, Betts JA, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for a large proportion of ovarian carcinoma cases. Cancer. 2005;104:2807–16. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE, et al. Prevalence and penetrance of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population series of 649 women with ovarian cancer. American journal of human genetics. 2001;68:700–10. doi: 10.1086/318787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh T, Casadei S, Lee MK, et al. Mutations in 12 genes for inherited ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal carcinoma identified by massively parallel sequencing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:18032–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115052108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malander S, Rambech E, Kristoffersson U, et al. The contribution of the hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome to the development of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;101:238–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gilks CB, Prat J. Ovarian carcinoma pathology and genetics: recent advances. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:1213–23. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Metcalfe KA, Fan I, McLaughlin J, et al. Uptake of clinical genetic testing for ovarian cancer in Ontario: a population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trainer AH, Meiser B, Watts K, et al. Moving toward personalized medicine: treatment-focused genetic testing of women newly diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20:704–16. doi: 10.1111/igc.0b013e3181dbd1a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NCCN Guidelines Panel National Comprehensive Cancer Network, editor. Genetic/Familial High-Risk Assessment: Breast and Ovarian. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Neill SC, White DB, Sanderson SC, et al. The feasibility of online genetic testing for lung cancer susceptibility: uptake of a web-based protocol and decision outcomes. Genet Med. 2008;10:121–30. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815f8e06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasparian NA, Butow PN, Meiser B, Mann GJ. High- and average-risk individuals' beliefs about, and perceptions of, malignant melanoma: an Australian perspective. Psycho-oncology. 2008;17:270–9. doi: 10.1002/pon.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Culver J, Burke W, Yasui Y, et al. Participation in breast cancer genetic counseling: the influence of educational level, ethnic background, and risk perception. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2001;10:215–31. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geer KP, Ropka ME, Cohn WF, et al. Factors influencing patients' decisions to decline cancer genetic counseling services. J Genet Couns. 2001;10:25–40. doi: 10.1023/a:1009451213035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahm AK, Sukhanova A, Ellis J, Mouchawar J. Increasing utilization of cancer genetic counseling services using a patient navigator model. J Genet Couns. 2007;16:171–7. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meropol NJ, Daly MB, Vig HS, et al. Delivery of Internet-based cancer genetic counselling services to patients' homes: a feasibility study. Journal of telemedicine and telecare. 2011;17:36–40. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2010.100116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brandt R, Ali Z, Sabel A, et al. Cancer genetics evaluation: barriers to and improvements for referral. Genetic testing. 2008;12:9–12. doi: 10.1089/gte.2007.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wideroff L, Vadaparampil ST, Greene MH, et al. Hereditary breast/ovarian and colorectal cancer genetics knowledge in a national sample of US physicians. J Med Genet. 2005;42:749–55. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.030296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer LA, Anderson ME, Lacour RA, et al. Evaluating women with ovarian cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations: missed opportunities. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:945–52. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181da08d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bryant H, Mah Z. Breast cancer screening attitudes and behaviors of rural and urban women. Preventive medicine. 1992;21:405–18. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(92)90050-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlich-Bakker KJ, ten Kroode HF, Warlam-Rodenhuis CC, et al. Barriers to participating in genetic counseling and BRCA testing during primary treatment for breast cancer. Genet Med. 2007;9:766–77. doi: 10.1097/gim.0b013e318159a318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bunn JY, Bosompra K, Ashikaga T, et al. Factors influencing intention to obtain a genetic test for colon cancer risk: a population-based study. Preventive medicine. 2002;34:567–77. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Novetsky AP, Smith K, Babb SA, et al. Timing of referral for genetic counseling and genetic testing in patients with ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:1016–21. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e3182994365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Cancer Institute . BRCA1 and BRCA2: Cancer Risk and Genetic Testing. National Cancer Institute FactSheet; 2014. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/Risk/BRCA: National Cancer Institute. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meiser B, Gleeson M, Kasparian N, et al. There is no decision to make: experiences and attitudes toward treatment-focused genetic testing among women diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124:153–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guttmacher AE, McGuire AL, Ponder B, Stefansson K. Personalized genomic information: preparing for the future of genetic medicine. Nature reviews Genetics. 2010;11:161–5. doi: 10.1038/nrg2735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borzekowski DL, Guan Y, Smith KC, et al. The Angelina effect: immediate reach, grasp, and impact of going public. Genet Med. 2013 doi: 10.1038/gim.2013.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ardern-Jones A, Kenen R, Eeles R. Too much, too soon? Patients and health professionals' views concerning the impact of genetic testing at the time of breast cancer diagnosis in women under the age of 40. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2005;14:272–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2005.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lobb E, Hallowel N, Barlow-Stewart K, Suthers G. Determining the genetic status of women newly diagnosed with breast cancer prior to treatment decision: an ethical challenge. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:437. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Daniels MS, Urbauer DL, Stanley JL, et al. Timing of BRCA1/BRCA2 genetic testing in women with ovarian cancer. Genet Med. 2009;11:624–8. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181ab2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]