Abstract

Background

Published data suggest that diabetes influences survival of patients with lung cancer. The anti-cancer effect of metformin confounds this association. We sought to study the association of diabetes and metformin with survival in patients undergoing resection of stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Methods

Pathologic stage I NSCLC patients undergoing anatomic resection from 2002 to 2011 were studied. A diagnosis of diabetes and diabetic medication use were identified through records. Univariate and multivariate analyses examined the association of diabetes and metformin usage with overall survival (OS).

Results

409 eligible patients were included in the analysis – excluding patients with neoadjuvant therapy, more than one lung cancer, or resection less than lobectomy. 71 (17.4%) patients were diabetics and 41 (10.0%) used metformin. With a median follow up of 44 months, univariate analysis demonstrates that diabetes had no effect on OS (P=0.75); however, metformin use was associated with improved OS (median survival not reached vs. 60 months; P=0.02). Metformin use remained an important predictor of good survival in multivariate analysis (HR=3.08; P<0.01) after adjusting for age, gender, pathologic stage, histology and smoking status.

Conclusion

Metformin use rather than diabetes is associated with improved long-term survival in Stage I NSCLC patients.

Keywords: Diabetes Mellitus, Lung cancer, Metformin, Survival

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) constitutes almost 85% cases of lung cancer with a poor overall 5 year survival of 16% [1]. Although only a small fraction of NSCLC cases are diagnosed in the early stages, it is this subgroup that is considered eminently curable by complete surgical resection. Unfortunately, in spite of diagnosis at an early stage and complete surgical resection, approximately one third of stage I cases develop a recurrence, [2,3] usually in the first five years. While chemotherapy improves outcomes in NSCLC greater than stage I, adjuvant therapy of stage I cancer has no clear role. In fact, the Lung Adjuvant Cisplatin Evaluation (LACE) meta-analysis suggests that adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy may increase the hazard for death in patients with stage IA disease [4]. One might hypothesize that selective administration of adjuvant therapy to patients at high risk of recurrence may lead to better outcomes. As a result, identification of prognostic factors may help deliver such “personalized therapy”.

Over the last few years, a number of studies have examined the molecular characteristics of patient tumors to prognosticate NSCLC. Analysis of gene expression, microRNA expression, epigenetic variations and mutational analyses are increasingly useful for the prognostication of NSCLC [5–8]. Refinements of histopathologic examination can be used to augment prognostic systems [9]. At the same time, a large proportion of patients with NSCLC have chronic conditions such as diabetes and are exposed to drugs with potential anti-cancer effects such as COX2 inhibitors and “statins”, which may influence cancer related clinical outcomes. Recent studies suggest that diabetes mellitus (DM) and metformin may affect cancer incidence and mortality [10,11]. Additionally, the potential anti-neoplastic role of the biguanide oral hypoglycemic agent metformin may confound possible associations between DM and survival of patients with NSCLC [12]. Previous studies examining this association used population-based databases with inherent limitations in the ability to accurately identify early stage patients. In this study, we sought to examine the interaction of diabetes and metformin on survival in early stage surgically treated NSCLC patients using a well annotated institutional tumor registry, billing records, and pharmacy records.

Methods

The Tumor Registry of our National Cancer Institute (NCI) Designated Comprehensive Cancer Center was queried for pathologic stage I (AJCC 6th edition) NSCLC patients undergoing anatomic resection (lobectomy or greater) between 2002–2011 in this IRB-approved study. Exclusion criteria included patients with more than one lung cancer, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or with resections less than a lobectomy. These criteria were selected in order to minimize confounding by variables that can impact the relationship between survival and diabetes/metformin. For example, it is possible that patients with more than one lung cancer may have stage misclassification [13]. Similarly, it was not reasonable to include patients with potentially more extensive disease down-staged to stage I as a result of neoadjuvant chemotherapy [14]. Billing data were used to identify diabetics and pharmacy records were used to identify anti-diabetic medications self-reported during physician and nurse interviews and from medication reconciliation information prepared during each patient encounter. Patients were categorized according to metformin use (yes or no). Patients using combination anti-diabetic agents that included metformin were also classified as metformin users. Univariate analyses using the Kaplan-Meier method examined the association of overall survival (OS) with diabetes and/or metformin use. Multivariate Cox Regression analyses examined survival associations controlling for age, gender, histology (squamous cell cancer, adenocarcinoma, and others), stage (IA and IB) and smoking (current, former, and never smokers). A p-value of 0.05 was used as a cutoff for statistical significance. All analyses were performed using SPSS 15.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc.).

Results

In 3393 consecutive NSCLC cases examined over this time period, 638 patients had pathologic stage I disease. A total of 409 patients remained eligible for analysis after exclusion for neoadjuvant therapy, more than one lung cancer, or with resection less than lobectomy. Among eligible patients, 91.7% were Caucasian, 57.9% were female, 9% were never smokers, 63.3% were pathologic stage IA, 59.7% had adenocarcinoma, and 2% underwent a pneumonectomy (Table 1). In the eligible cohort, 71 (17.4%) were diabetics and 41 (10.0%) used metformin. As higher proportion of metformin users were taking insulin as compared to non-metformin users (24.4% vs. 1.6%; p <0.001) (Table 1) but this is not unexpected considering that non-metformin users were mostly non-diabetics. Table 1 showing the comparison of both groups shows that a higher fraction of metformin users were alive at the time of last follow-up as compared to the non-metformin users (82.9% vs. 60.6%; p<0.005).

Table 1.

Patient Demographics (N=409); A significantly higher proportion of metformin users were on insulin and were alive at the last follow up. SqCC-Squamous Cell Carcinoma.

| Variable | Non-Metformin user | Metformin user | Overall | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Number | 368 (90%) | 41 (10%) | 409 (100%) | |

|

| ||||

| Age (Mean ± SD); Range | 68.3 ± 10.3; 21–93 | 71.0 ± 8.8; 45–85 | 68.5 ± 10.2; 21–93 | 0.131 |

|

| ||||

| Gender-Male | 157 (42.7%) | 15 (36.6%) | 172 (42.1%) | 0.455 |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| White | 340 (92.4%) | 35 (85.4%) | 375 (91.7%) | |

| Others | 28 (7.6%) | 6 (14.6%) | 34 (8.3%) | 0.122 |

|

| ||||

| Smoking | ||||

| Current | 157 (42.7%) | 12 (29.3%) | 169 (41.3%) | |

| Previous | 179 (48.6%) | 24 (58.5%) | 203 (49.6%) | 0.243 |

| Never | 32 (8.7%) | 5 (12.2%) | 37 (9%) | |

|

| ||||

| Surgery | ||||

| Lobectomy | 360 (97.8%) | 41 (100%) | 401 (98%) | |

| Pneumonectomy | 8 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (2.0%) | 0.688 |

|

| ||||

| Histology | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 224 (60.9%) | 20 (48.8%) | 244 (59.7%) | |

| SqCC | 108 (29.3%) | 16 (39%) | 124 (30.3%) | 0.323 |

| Others | 36 (9.8%) | 5 (12.2%) | 41 (10%) | |

|

| ||||

| Pathologic stage | ||||

| IA | 231 (62.8%) | 28 (68.3%) | 259 (63.3%) | |

| IB | 137 (37.2%) | 13 (31.7%) | 150 (36.7%) | 0.487 |

|

| ||||

| Insulin use | ||||

| Yes | 6 (1.6%) | 10 (24.4%) | 16 (3.9%) | |

| No | 362 (98.4%) | 31 (75.6%) | 393 (96%) | <0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Alive at last follow up | ||||

| Yes | 223 (60.6%) | 34 (82.9%) | 257 (62.8%) | |

| No | 145 (39.4%) | 7 (17.1%) | 152 (37.2%) | 0.005 |

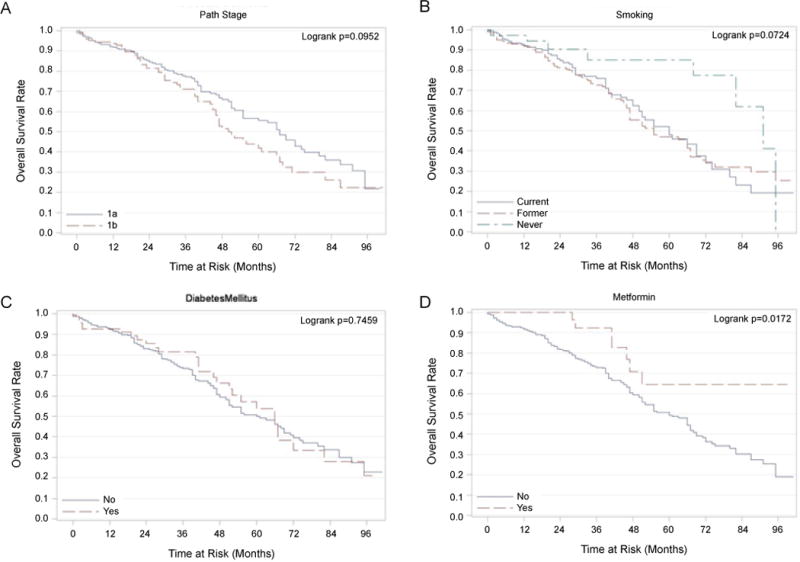

Among 409 eligible patients, 257 patients were alive at last follow up. Univariate analysis did not reveal a statistically significant relationship between OS and gender (p=0.81), but a non-significant trend was noted for inferior survival in Stage IB patients (p=0.09; Figure 1A). Never smokers had a trend for improved OS vs. current or former smokers (median survival of 91 months vs. 60 and 55 months respectively; p = 0.07; Figure 1B). Patients with squamous cell cancer had a poorer survival than those with adenocarcinoma (55 months vs. 66 months respectively; p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier Plots of Overall Survival (OS) Rates. Panel A-Kaplan-Meier plot of overall survival with stage (IA and IB). Panel B-Kaplan-Meier plot showing a trend toward better survival of never smokers compared to current/former smokers (P=0.07). Panel C-Kaplan-Meier plot showing no difference in OS in patients with and without DM. Panel D-Kaplan-Meier plot showing significantly better OS in patients on metformin compared to those not on metformin (P=0.02).

On univariate analysis, there was no statistically significant association between diabetes mellitus and OS (p=0.75; Figure 1C); however, patients using metformin had significantly better survival than those not using metformin (median survival not reached vs. 60 months; p=0.02; Figure 1D). After adjusting for age, gender, race, diabetes mellitus, smoking status, histology, pathological stage and insulin use, multivariate analysis demonstrated that metformin use improved overall survival (HR 3.08, p<0.01, Table 2 and Figure 2). In order to examine if this result was driven primarily by poor outcomes in diabetic patients not on metformin, the overall survival of diabetic patients not on metformin (n=35) was compared with non-diabetic patients not on metformin (n=333). This comparison was not statistically significant (p=0.147); diabetic patients not on metformin had a median survival of 55 months (95% CI: 35–75 months) compared to non-diabetic patients not on metformin who had a median survival of 61 months (95% CI: 50–72 months).

Table 2.

Factors associated with overall survival in multivariate model. Higher hazard ratio (HR) denotes increased risk of death. SqCC: Squamous cell cancer, AdenoCa: Adenocarcinoma.

| Variable | Reference | P-value | HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| No Metformin | Metformin | 0.009 | 3.08 (1.32–7.19) |

|

| |||

| Age | 0.004 | 1.03 (1.01–1.05) | |

|

| |||

| Gender: Female | Male | 0.665 | 1.08 (0.77–1.50) |

|

| |||

| Race: Other | White | 0.529 | 1.21 (0.67–2.2) |

|

| |||

| Diabetes: No | Diabetes | 0.293 | 0.78 (0.48–1.25) |

|

| |||

| Smoking: Current | Smoking: Previous | 0.58 | 1.13 (0.79–1.62) |

|

| |||

| Smoking: Never | Smoking: Previous | 0.028 | 0.44 (0.21–0.92) |

| Histology: AdenoCa | Histology: SqCC | 0.036 | 0.68 (0.48–0.98) |

| Histology: Other | Histology: SqCC | 0.158 | 0.64 (0.35–1.19) |

| Path stage: IA | Path stage: IB | 0.224 | 0.81 (0.58–1.14) |

| Insulin: No use | Insulin: Use | 0.918 | 1.05 (0.393–2.82) |

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier plot showing significantly better OS in patients on metformin after controlling for the effect of age, gender, race, stage, smoking and histology.

Discussion

Diabetes mellitus is a widespread chronic condition commonly seen in lung cancer patients. A recent analysis of 11,190 patients with Stage I–II NSCLC from Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) reports a high prevalence of DM (26.6%) [15]. Conversely, the diagnosis of diabetes may be associated with a higher incidence of lung cancer. A recent meta-analysis of 97 studies comprising 820,900 people reports a moderate association of lung cancer death with a diagnosis of DM (Hazards Ratio 1.27; 95% CI: 1.13–1.43) [10]. Despite its prevalence, the association of DM with outcomes in lung cancer has only recently gained attention and the results of investigations studying are largely inconclusive. A Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program database study along with several others report a worse overall outcome in diabetic patients with lung cancer, including tumor recurrence [15,16]. Conversely, some studies support improved survival in patients of lung cancer with DM [17,18]. A recent analysis of registry data from Norway with 1067 lung cancer including 77 cases with DM, reports a lower mortality in lung cancer patients with DM [18]. Similarly, Hanbali and colleagues report that DM is associated with lower rate of metastasis in 566 patients with NSCLC; however, this did not translate into lower mortality [19]. Several others show no association between DM and NSCLC outcome [20,21]. From a mechanistic viewpoint, research shows conflicting effects of DM on tumor progression as well. On one hand, pathways mediated by high levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factors may be responsible for fostering cancer progression and may lead to worse outcomes [22]. On the other hand, it has been hypothesized that the vascular changes due to diabetic microangiopathy may hamper spread of neoplastic cells and thereby protect against metastases [23].

The divergence of results between different studies may be due to differences in patient selection and/or potential confounding anti-neoplastic effects of medical management using metformin. Metformin belongs to the biguanide class of oral hypoglycemic agents that decrease hepatic glucose production and improve insulin action. Metformin is a first-line oral drug used in the treatment of DM. Several lines of evidence suggest that metformin has antineoplastic activity in lung cancer. Epidemiologic reports show a reduced rate of incidental cancers in diabetic patients on metformin [24,25]. A recent study from Taiwan reports a higher incidence of gastrointestinal cancer in patients with DM, and metformin reduces this incidence to normal or below normal levels [26]. Recent meta-analyses conclude that use of metformin in diabetic patients is associated with a lower risk of cancer [27]. Similarly, a recent study did not show any association between DM and increased risk of lung cancer, but instead showed a reduction in lung cancer risk with the use of anti-diabetic medications [28]. In terms of outcomes after incidence of cancer, Currie et al. demonstrated that diabetic patients with incidental cancers (including lung) have a worse prognosis than non-diabetics; however, metformin use results in improved survival when compared with diabetics treated using other drugs and compared with non-diabetics [29]. Another study showed that diabetic patients with lung cancer who are exposed to metformin prior to diagnosis seem to have a lower probability of presenting with metastatic disease and a higher probability of improved survival [30]. A recent retrospective study concludes that metformin use improves chemotherapy outcomes and survival in diabetic patients with stage II–IV NSCLC [31]. These epidemiologic and clinical observations are supported by pre-clinical experimental data as well. For example, animal studies show that metformin prevents tobacco-induced carcinogenesis in mice by reducing lung tumor burden by >50% [32]. Also, metformin enhances the anti-proliferative effects of chemotherapeutic agents on several tumor cell lines including lung cancer cell lines [33].

Several mechanisms of action for metformin’s anti-neoplastic activity have been investigated and are discussed well in recent reviews [34–38]. One potential mechanism of action is a metformin-induced reduction in the high levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factors, which have been implicated in promoting cancer development and progression [22]. Metformin also activates 5′ adenosine monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase, which inhibits protein synthesis and neoplastic cell proliferation [35]. In addition, metformin may also exert antineoplastic effect by inhibiting the Phosphoionisitide-3 kinase/Protein kinase B/mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway in cancers cells, which is responsible for cellular growth and proliferation. Several others mechanisms of metformin’s anti-cancer effect also include modification of tumor milieu with reduced inflammation, induction of apoptosis, decrease in epidermal growth factor (EGFR) receptor levels, reduction of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation, and modulation of several other proteins in cancer progression including Src, p53, cyclin D1, and surviving [34–36,38].

Our finding that use of metformin is associated with improved survival in patients with stage I NSCLC adds to the growing body of literature that suggests a potential beneficial role of metformin in lung cancer survival. To our knowledge, this is the first study of metformin on lung cancer focused on a relatively uniform cohort of patients with early stage NSCLC without treatment using modalities other than surgery. This prevents confounding by potential effect-modifications or interactions between metformin and chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy. However, there are several limitations of this study. The retrospective nature of this study using medical records limits interpretation of results due to attendant and misclassification bias. This risk is mitigated in part by the fact that most patients undergoing thoracic surgery are evaluated with routine laboratory blood work during their preoperative workup, which should improve detection of DM. In addition, this study is limited by the lack of data evaluating relationships between glucose control and its effect on cancer outcome as a potential confounder. Also, no longitudinal assessment of metformin use is done. Along with possible confounding with concomitant influence of other agents such as sulfonylureas or statins, this lack of data limits the strength of conclusions that can be drawn. In addition, no data evaluating time to recurrence are available for analysis in this study.

Despite these limitations, our study suggests that metformin use rather than diabetes improves survival in patients with Stage I NSCLC. With the potential anti-cancer effects of metformin in vitro, this commonly used drug warrants consideration as an adjuvant therapy for early stage NSCLC. Findings from this retrospective study should be validated using additional cohorts and support consideration of metformin use in a prospective study.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

This work was supported by Roswell Park Cancer Institute and National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant #P30 CA016056.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

None of the authors have any conflict of interest or financial interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.20138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelsey CR, Marks LB, Hollis D, Hubbs JL, Ready NE, et al. Local recurrence after surgery for early stage lung cancer: an 11-year experience with 975 patients. Cancer. 2009;115:5218–5227. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Starnes SL, Pathrose P, Wang J, Succop P, Morris JC, et al. Clinical and molecular predictors of recurrence in stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:1606–1612. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pignon JP, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV, Douillard JY, Shepherd FA, et al. Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3552–3559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.9030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen G, Kim S, Taylor JM, Wang Z, Lee O, et al. Development and validation of a quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction classifier for lung cancer prognosis. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1481–1487. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822918bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patnaik SK, Kannisto E, Knudsen S, Yendamuri S. Evaluation of microRNA expression profiles that may predict recurrence of localized stage I non-small cell lung cancer after surgical resection. Cancer Res. 2010;70:36–45. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vallböhmer D, Brabender J, Yang D, Schneider PM, Metzger R, et al. DNA methyltransferases messenger RNA expression and aberrant methylation of CpG islands in non-small-cell lung cancer: association and prognostic value. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;8:39–44. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2006.n.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scoccianti C, Vesin A, Martel G, Olivier M, Brambilla E, et al. Prognostic value of TP53, KRAS and EGFR mutations in nonsmall cell lung cancer: the EUELC cohort. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:177–184. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00097311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, Nicholson AG, Geisinger KR, et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/American thoracic society/European respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–285. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Seshasai SR, Kaptoge S, Thompson A, Di Angelantonio E, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting glucose, and risk of cause-specific death. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:829–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1008862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Noto H1, Goto A, Tsujimoto T, Noda M. Cancer risk in diabetic patients treated with metformin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, Bergenstal RM, Gapstur SM, et al. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:207–221. doi: 10.3322/caac.20078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nair A, Klusmann MJ, Jogeesvaran KH, Grubnic S, Green SJ, et al. Revisions to the TNM staging of non-small cell lung cancer: rationale, clinicoradiologic implications, and persistent limitations. Radiographics. 2011;31:215–238. doi: 10.1148/rg.311105039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trodella L, Granone P, Valente S, Margaritora S, Macis G, et al. Neoadjuvant concurrent radiochemotherapy in locally advanced (IIIA–IIIB) non-small-cell lung cancer: long-term results according to downstaging. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:389–398. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang Y, Mauldin P, Ebeling M, Hulsey T, Camp ER, et al. Effect of metabolic syndrome and its components on survival in patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e17510. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varlotto J, Medford-Davis LN, Recht A, Flickinger J, Schaefer E, et al. Confirmation of the role of diabetes in the local recurrence of surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;75:381–390. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Giorgio R, Barbara G, Cecconi A, Corinaldesi R, Mancini AM. Diabetes is associated with longer survival rates in patients with malignant tumors. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2217. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hatlen P, Grønberg BH, Langhammer A, Carlsen SM, Amundsen T. Prolonged survival in patients with lung cancer with diabetes mellitus. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1810–1817. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31822a75be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanbali A, Al-Khasawneh K, Cole-Johnson C, Divine G, Ali H. Protective effect of diabetes against metastasis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:513. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.5.513-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tammemagi CM, Neslund-Dudas C, Simoff M, Kvale P. Impact of comorbidity on lung cancer survival. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:792–802. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satoh H, Ishikawa H, Kurishima K, Ohtsuka M, Sekizawa K. Diabetes is not associated with longer survival in patients with lung cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:485. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallagher EJ, LeRoith D. Minireview: IGF, Insulin, and Cancer. Endocrinology. 2011;152:2546–2551. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nerlich AG, Hagedorn HG, Böheim M, Schleicher ED. Patients with diabetes-induced microangiopathy show a reduced frequency of carcinomas. In Vivo. 1998;12:667–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans JM, Donnelly LA, Emslie-Smith AM, Alessi DR, Morris AD. Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in diabetic patients. BMJ. 2005;330:1304–1305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38415.708634.F7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Libby G, Donnelly LA, Donnan PT, Alessi DR, Morris AD, et al. New users of metformin are at low risk of incident cancer: a cohort study among people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1620–1625. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MS, Hsu CC, Wahlqvist ML, Tsai HN, Chang YH, et al. Type 2 diabetes increases and metformin reduces total, colorectal, liver and pancreatic cancer incidences in Taiwanese: a representative population prospective cohort study of 800,000 individuals. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soranna D, Scotti L, Zambon A, Bosetti C, Grassi G, et al. Cancer risk associated with use of metformin and sulfonylurea in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2012;17:813–822. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai SW, Liao KF, Chen PC, Tsai PY, Hsieh DP, et al. Antidiabetes drugs correlate with decreased risk of lung cancer: a population-based observation in Taiwan. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13:143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Currie CJ, Poole CD, Jenkins-Jones S, Gale EA, Johnson JA, et al. Mortality after incident cancer in people with and without type 2 diabetes: impact of metformin on survival. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:299–304. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mazzone PJ, Rai H, Beukemann M, Xu M, Jain A, et al. The effect of metformin and thiazolidinedione use on lung cancer in diabetics. BMC Cancer. 2012;12:410. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan BX, Yao WX, Ge J, Peng XC, Du XB, et al. Prognostic influence of metformin as first-line chemotherapy for advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cancer. 2011;117:5103–5111. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Memmott RM, Mercado JR, Maier CR, Kawabata S, Fox SD, et al. Metformin prevents tobacco carcinogen-induced lung tumorigenesis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3:1066–1076. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iliopoulos D, Hirsch HA, Struhl K. Metformin decreases the dose of chemotherapy for prolonging tumor remission in mouse xenografts involving multiple cancer cell types. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3196–3201. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dowling RJ, Goodwin PJ, Stambolic V. Understanding the benefit of metformin use in cancer treatment. BMC Med. 2011;9:33. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aljada A, Mousa SA. Metformin and neoplasia: implications and indications. Pharmacol Ther. 2012;133:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bost F, Sahra IB, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Tanti JF. Metformin and cancer therapy. Curr Opin Oncol. 2012;24:103–108. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32834d8155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Del Barco S, Vazquez-Martin A, Cufí S, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Bosch-Barrera J, et al. Metformin: multi-faceted protection against cancer. Oncotarget. 2011;2:896–917. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martin-Castillo B, Vazquez-Martin A, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Menendez JA. Metformin and cancer: doses, mechanisms and the dandelion and hormetic phenomena. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:1057–1064. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.6.10994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]