Abstract

Mon1 is an evolutionarily conserved protein involved in the conversion of Rab5 positive early endosomes to late endosomes through the recruitment of Rab7. We have identified a role for Drosophila Mon1 in regulating glutamate receptor levels at the larval neuromuscular junction. We generated mutants in Dmon1 through P-element excision. These mutants are short-lived with strong motor defects. At the synapse, the mutants show altered bouton morphology with several small supernumerary or satellite boutons surrounding a mature bouton; a significant increase in expression of GluRIIA and reduced expression of Bruchpilot. Neuronal knockdown of Dmon1 is sufficient to increase GluRIIA levels, suggesting its involvement in a presynaptic mechanism that regulates postsynaptic receptor levels. Ultrastructural analysis of mutant synapses reveals significantly smaller synaptic vesicles. Overexpression of vglut suppresses the defects in synaptic morphology and also downregulates GluRIIA levels in Dmon1 mutants, suggesting that homeostatic mechanisms are not affected in these mutants. We propose that DMon1 is part of a presynaptically regulated transsynaptic mechanism that regulates GluRIIA levels at the larval neuromuscular junction.

Keywords: Drosophila, Rabs, Mon1, synapse, GluRIIA

SYNAPTIC strength is tightly modulated through expression of presynaptic and postsynaptic proteins. The regulation occurs at the level of transcription, translation, or degradation via the ubiquitin–proteosome and lysosomal pathways (DiAntonio et al. 2001; Dobie and Craig 2007; Fernandez-Monreal et al. 2012). The larval neuromuscular junction (NMJ) in Drosophila is glutamatergic and serves as an excellent system to study regulation of receptor levels—one of the key factors underlying synaptic strength and functional plasticity.

During development, expression of the glutamate receptor subunits, including GluRIIA, is regulated by Lola—a BTB Zn-finger domain transcription factor in an activity-dependent manner (Fukui et al. 2012). The abundance of the receptor at the synapse is sensitive to presynaptic inputs and is subject to translational control by RNA binding proteins and microRNAs (Sigrist et al. 2000, 2003; Menon et al. 2004; Heckscher et al. 2007; Karr et al. 2009; Menon et al. 2009). The precise mechanism that controls this regulation is not clear. In addition, the role of endocytic pathways in regulating glutamate receptor levels through trafficking to and from the synapse, as well as the molecular pathways governing protein turnover are still poorly understood.

Endocytic vesicles carrying cell surface proteins such as signaling molecules, cellular organelles, and engulfed pathogens sort their cargo such that they are either recycled or targeted to the lysosome for degradation. The trafficking of these vesicles, through fusion with appropriate membrane compartments, is regulated by Rab GTPases—a family of small G-proteins. Mon1 was first identified in yeast as a protein, which in complex with CCZ1, regulates all fusion events to the lysosome (Wang et al. 2002, 2003). Subsequent studies in Caenorhabditis elegans identified SAND-1/Mon1 as an effector of Rab5, and as a factor essential for recruitment of Rab7, highlighting its role in the conversion of Rab5 positive early endosome to Rab7 containing late endosome (Poteryaev et al. 2007; Kinchen and Ravichandran 2010; Poteryaev et al. 2010). Consistent with these studies, loss of Mon1 in Drosophila is shown to result in enlarged endosomes and loss of endosomal Rab7, implying a role for DMon1 in the recruitment of Rab7 (Yousefian et al. 2013).

We are interested in pathways that regulate synaptic function for their implication in motor neuron disease (Ratnaparkhi et al. 2008). We isolated a mutation in Mon1 while screening for P-element excisions in the neighboring gene pog. A striking phenotype observed in these mutants was their inability to walk or climb normally. The presence of a strong motor defect implied impaired neuronal or muscle dysfunction that prompted us to examine these mutants in greater detail.

In this study, we describe a role for Drosophila Mon1 (Dmon1) in regulating GluRIIA expression at the NMJ. Dmon1 mutants show multiple synaptic phenotypes. A striking phenotype among these is the huge increase in postsynaptic GluRIIA levels. The increase in receptor levels appears to be posttranscriptional, suggestive of control at the level or translation, trafficking, or protein degradation. We show that neuronal knockdown of Dmon1 is sufficient to phenocopy the GluRIIA phenotype, indicating the involvement of a presynaptic mechanism in regulating receptor levels. We find that Dmon1 mutants have smaller neurotransmitter vesicles, and overexpression of the vesicular glutamate transporter (vglut) suppresses the synaptic morphology and GluRIIA phenotype in Dmon1 mutants. Our results thus suggest a novel role for DMon1 in regulating GluRIIA levels, which we hypothesize may, in part, be via a mechanism linked to neurotransmitter release.

Materials and Methods

Generation and mapping of Mon1 mutants

The mutants Dmon1Δ181 and Dmon1Δ129 were generated by excising the pUAST-Rab21::YFP insertion (Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center) using standard genetic methods. Δ181 and Δ129 failed to complement each other and deficiency lines Df (2L) 9062, Df (2L) 6010, and Df(2L)8012, which span the genomic locus, but showed complementation to mRpS2EY10086 (Mathew et al. 2009), suggesting that the deletion does not extend to mRpS2.

Molecular mapping was carried out using PCR on genomic DNA isolated from homozygous third instar mutant larvae identified using second chromosome GFP balancers. To map the deletion, the entire region spanning genes Dmon1 and pog was analyzed by PCR.

Primers 11926_2F and primer 31660_Ex2R (Figure 1A, gray arrows) amplified a 850-bp product with Δ181 (2128 bases in wild type). This was cloned and sequenced to determine the breakpoints of the deletion. In Δ129 mutants, primers 3F in CG11926 and Int1_R2 in CG31660/pog (Figure 1A, red arrows) amplified a 550-bp band instead of the expected 2.4 kb. The pog primer sequences used for mapping include: Ex 31660_1F, ACTGGTGCTGGCCGACCGCTC; Ex31660_2R, AACCGACAGATACACGAGCATT; Intron1, F1AATGCTCGTGTATCTGTCGGTT; Intron1 F2, TGCCAGCATCAGGCTATCAAG; and Intron1 R2, CTTGATAGCCTGATGCTGGCA. Dmon1 primers used for deletion mapping and RT-PCR are: 11926_1F, ATGGAAGTAGAGCAGACGTCAGT; 11926_ 2F, AGCACGACAGTCTGTGGCAGG; 11926_ 3F, ATCTGCATGCGCATGTCTCGTAC; and 11926_ 4F, GAAACCATGCCACATTCTAAGCTT. The reverse primers were complementary to forward primers. Primers used for quantitative PCR include: RP49_forward, GACGCTTCAAGGGACAGTATC; RP49_reverse, AAACGCGGTTCTGCATGAG; GluRIIA_forward, CGCACCTTCACTCTGATCTATG; and GluRIIA_reverse, CTGTCTCCTTCCACAATATCCG.

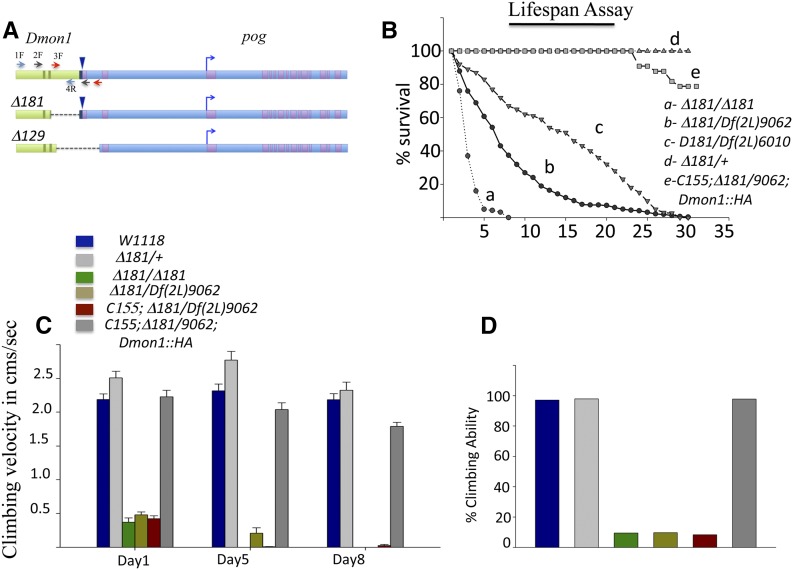

Figure 1.

Characterization of Dmon1 mutants. (A) Genomic region spanning CG11926/Dmon1 (light green) and CG31660/pog (light blue). A blue arrowhead marks the site of insertion of the excised pUASt-YFP.Rab21. Deletions generated for line Δ181 and Δ129 are marked. (B) Lifespan defect in Dmon1 mutants. Dmon1Δ181 flies (a, n = 91) do not survive beyond 10 days while Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 (b, n = 316) and Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)6010 (c, n = 259), have half-lives of ∼7 and 18 days, respectively. Expression of UAS-Dmon1::HA in Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 using C155-GAL4 rescues the lifespan defect in Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L9062) flies (e, n = 33) to near controls (Dmon1Δ181/+, d, n = 50). (C) Climbing speed of wild type and Dmon1 mutants. w1118 and Dmon1Δ181/+ flies show comparable climbing speeds on day 1 and on day 8. Dmon1Δ181, Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062, and C155; Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 in contrast, are poor climbers (P < 0.001). Panneuronal expression of UAS-Dmon1::HA in Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 rescues the climbing defect. Error bars represent standard error. (D) Climbing ability of w1118 and Dmon1 mutants. W1118, Dmon1Δ181/+ (97.95%) and rescue flies show robust climbing ability. Less than 10% of Dmon1Δ181, Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062, and C155-GAL4; Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 are able to climb.

Drosophila stocks and fly husbandry

All stocks were reared on regular corn flour medium. The following fly stocks were used: pUAST-Rab21::YFP (no. 23242), Df(2L)9062, and Df(2L)6010 were from the Bloomington Stock Center; Dmon1 RNAi line (GD38600) was obtained from the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Center (VDRC); UAS-dvglut and Sp/Cyo,wglacZ; UAS-mon1::HA were kind gifts from A. DiAntonio, Washington University, and T. Klein, University of Dusseldorf, respectively. Except where stated, all experiments were carried out at 25°.

Behavioral assays

Life span assays were carried out at 25°. The flies were monitored every day and transferred to fresh medium every other day. Measurement of climbing speed was carried out as described previously for spastin mutants (Sherwood et al. 2004). Individually maintained, control and mutant flies were evaluated for climbing at 24–26 hr, 120 hr (day 5), and 192 hr (day 8) posteclosion. Each individual animal was subjected to three trials and the speed was calculated as the average of all three trials. Climbing ability was calculated by scoring for the number of flies that climbed 6 cm in 5 sec.

Immunohistochemistry and image analysis

Wandering third instar larvae were dissected in PBS and fixed with Bouins fixative (15 min). The following antibodies were used: anti-FasciclinII or mAb1D4 (1:15 or 1:25, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB); mAbnc82 (1:50, DSHB); anti-GluRIIA/mAb8B4D2 (1:200, ascites; DSHB); anti-HRP (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich); anti-Rab5 [1:200 (for Figure 5) and 1:500, AbCam]; anti-HA (1:200, Sigma, no. 9658); anti-Rab7 (1:100) (Chinchore et al. 2009); and anti-GluRIIB and anti-vGlut (1:2000 and 1:500, gift from A. DiAntonio and Herman Aberle respectively). For anti-GluRIIB staining, animals were fixed for 1 min in Bouins fixative. For anti-Rab5 and anti-Rab7, animals were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Confocal imaging was carried out on a Zeiss 710 imaging system at Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER). All confocal images were taken using a 63× objective (N.A. = 1.4).

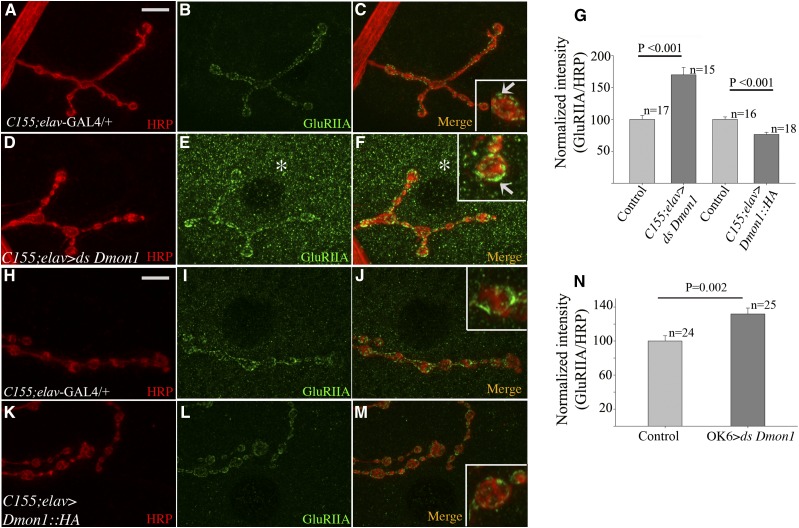

Figure 5.

Loss of neuronal Dmon1 increases GluRIIA levels at synaptic and extrasynaptic sites. (A–C and H–J) Control (C155-Gal4/+; elav-GAL4/+) synapse at muscle 4 immunostained with anti-HRP (red) and anti-GluRIIA (green). (D–F) Presynaptic knockdown of Dmon1 increases intensity of GluRIIA staining at the NMJ (F, arrow in inset). Increase in extrasynaptic GluRIIA punctae is observed (E and F, asterisk). (G) Normalized GluRIIA:HRP intensity for Dmon1 RNAi and UAS-Dmon1::HA animals. RNAi animals show a 70% increase in intensity. (K–M) Neuronal overexpression of Dmon1:HA leads to decrease in intensity of GluRIIA (L, inset in M) by 24% (G). (N) A 32% increase in GluRIIA expression was observed in OK6-GAL4 > UAS-Dmon1RNAi animals. Error bars represent SEM.

Image analysis and fluorescence intensity measurements were carried out using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, NIH, Bethesda). Quantititation of GluRIIA and GluRIIB levels was carried out using the method described previously in Menon et al. (2009). The average gray value per synapse was determined by measuring the intensity of three individual boutons. In each case, the measured values were normalized to the background intensity for the same area. Since the mutants show significant GluRIIA staining in muscles, a region of the nucleus or regions free of GluRIIA staining was chosen for background normalization.

Analysis of the size and intensity of Brp punctae was carried out as described in Dickman et al. (2006). Briefly, three times the background was subtracted from the image and the resulting image was duplicated. One duplicate image was converted to binary and segmented using the watershed algorithm. Puncta size was measured from the segmented binary image using the “analyze particles” tool in ImageJ and intensity using the “redirect” option referring to the nonbinary image in the “set measurements” option. Control and experimental larvae used for quantitation were processed simultaneously for immunostaining. A master mix of the antibodies at appropriate dilutions was made prior to addition to individual tubes. Imaging was carried out under identical confocal settings. Figures were assembled using Adobe Photoshop CS4 and PowerPoint. Statistical analysis (Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA for Figure 4) was carried out using Sigma Plot 10. The 3D volume rendering of the bouton for Figure 7 was carried out using IMARIS software at IISER.

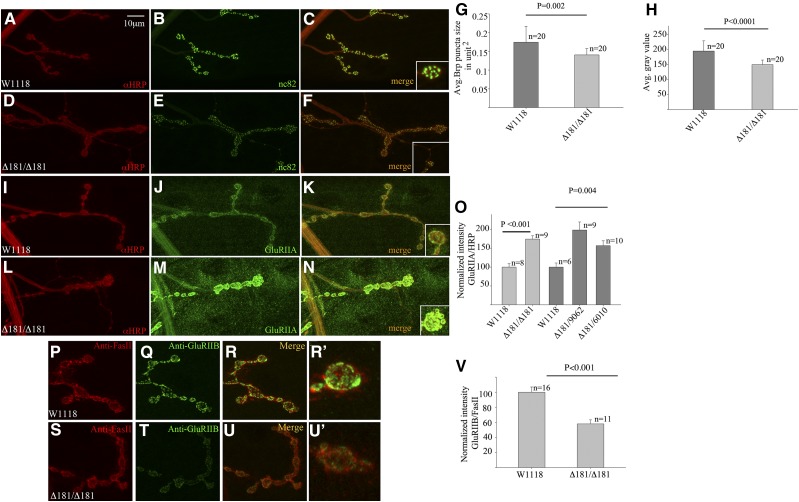

Figure 4.

Expression levels of Brp and GluRIIA are altered in Dmon1Δ181 mutants. (A–F) Synapse at muscle 4 stained with anti-HRP (red) and mAb nc82 (anti-Brp, green) in w1118 animal (A–C) and homozygous Dmon1Δ181 mutant (D–F). Intensity of Brp staining is low (inset in F). (G) Size of nc82 postive puncta in Dmon1Δ181 mutants is 17.6% smaller than wild type (P = 0.002). (H) Intensity of nc82 puncta in Dmon1Δ181 mutants is 23% less compared to wild type. (I–N) NMJ at muscle 4 stained with anti-HRP (red) and GluRIIA (green). (I–K) w1118 synapse. (L–N) Homozygous Dmon1Δ181. Elevated GluRIIA expression is seen at the synapse and muscles. (O) Quantification of GluRIIA intensity normalized to HRP. Homozygous Dmon1Δ181 mutants show a 74% increase in intensity compared to wild type. Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)6010 and Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 animals show a 56% and 98% increase, respectively. Error bars represent SEM. (P–U) NMJ at muscle 4 immunostained with anti-FasII (red) and anti-GluRIIB (green). (P–R and R′) w1118 synapse. (S–U and U′) Dmon1Δ181 mutant. GluRIIB expression is reduced. (V) Quantification of GluRIIB intensity normalized to anti-FasII. Dmon1Δ181 mutants show a 42% decrease in GluRIIB compared to wild type. Error bars represent SEM.

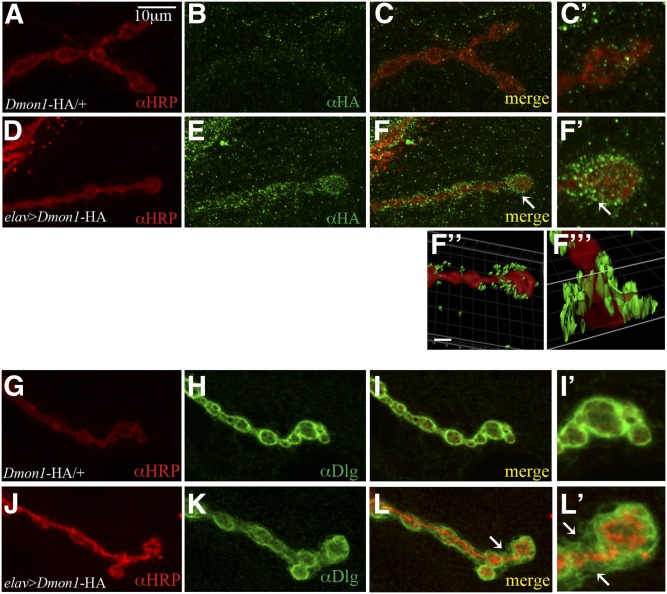

Figure 7.

DMon1 localization is perisynaptic. (A–C and C′). Control animal (UAS-Dmon1::HA/+) stained with anti-HRP (red) and anti-HA antibody (green). A few green puncta are seen in the background (C and C′). (D–F) elav-GAL4 > UAS-Dmon1::HA animal. HA positive puncta are seen surrounding the bouton (F and F′). A 3D volume rendering of the image and its cross-section shows HA positive puncta to be surrounding the bouton (F′′ and F′′′). (G–I) Anti-HRP (red) and anti-Dlg (green) staining in control (UAS-Dmon1::HA/+) and elav-GAL4 > UAS-Dmon1::HA (J–L) animals. Note the diffuse Dlg staining in elav-GAL4 > UAS-Dmon1::HA (K, L, and L′).

TEM analysis

Wild-type and mutant third instar larvae were processed for electron microscopy as described (Ratnaparkhi et al. 2008). Briefly, the larvae were dissected in PBS and fixed for 2 hr with 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.12 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). Samples were postfixed with 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.12 M sodium cacodylate with rotation. Staining with 2% uranyl acetate was carried out en bloc for at least 1 hr. The samples were washed, dehydrated using an ethanol series, and embedded in araldite resin. Analysis was carried out on a FEI Tecnai G2 spirit, 120 Kv transmission electron microscope. Type 1b boutons from segments A2 and A3 were imaged and used for analysis. Electron micrographs were analyzed using ImageJ. A total of 200 vesicles from 10 boutons (wild type, four animals) and 100 vesicles from 7 boutons (three animals) were used for quantitation. In most cases, vesicles near active zones were chosen for analysis.

Real-time PCR

Third instar larvae were dissected in PBS and RNA was isolated from body wall muscles of the larvae using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. An equal amount of RNA from W1118 (control) and Δ181 larvae was used for cDNA synthesis. Real-time PCR was performed for rp49 and GluRIIA with SYBR green mix (Kappa Biosystem) on an Eppendorf RealPlex2. The fold change was calculated using 2−Δ(ΔCT).

Data availability

Supplemental information present in Figure S1, Figure S2, and Figure S3.

Results

Dmon1 mutants have lifespan and motor defects

We generated and identified a mutation in Dmon1 through imprecise excision of pUASt-YFP::Rab21 located at the 3′ end of Dmon1 and 5′ upstream of its neighbor pog. Two of the putative excision lines Δ129 and Δ181 failed to complement the deficiencies spanning the locus. Molecular mapping using PCR revealed the excision in Δ129 to span the 3′ end of Dmon1 and 5′ end of pog. The deletion in Δ181 was restricted to Dmon1, extending from position 4851580 in the second intron to 4852858—5 bases upstream of the transcription start site of CG31660 (Figure 1A). Details of the excision and molecular mapping are described in Materials and Methods. RT-PCR analysis of Δ181 showed that these mutants express a truncated transcript corresponding to residues 1–248 of the protein sequence. A full-length transcript was not detected in the mutants—a result consistent with the molecular nature of the mutation (Supporting Information, Figure S1, C and D). Using RT-PCR, we also confirmed that the deletion in Δ181 does not affect expression of the neighboring pog gene (Figure S1E).

Homozygous Dmon1Δ181 mutants die throughout development and during eclosion. The escaper adults are weak and usually die within 7 days. We measured the life span of Dmon1Δ181 mutants as homozygotes and in combination with the deficiencies that span the locus. Homozygous Dmon1Δ181 mutants show a severe lifespan defect: 50% of the animals survive <5 days. In case of Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 and Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)6010, the half-life of the animals was approximately 7 and 18 days, respectively (Figure 1B). Expression of a HA-tagged Dmon1 (UAS-Dmon1::HA) using the pan-neuronal driver C155-GAL4, rescued the life span defect in Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 mutants (Figure 1B), indicating that lethality and reduced life span were due to loss of Dmon1.

Dmon1 mutants that eclose are slow and unable to climb. We quantified this defect by measuring the climbing speed and climbing ability of Dmon1Δ181 and Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 mutant animals 24 hr posteclosion. Wild-type and Dmon1Δ181/+ animals did not show any significant difference in their average climbing speed [2.18 ± 0.48 (n = 34) sec vs. 2.5 ± 0.66 (n = 48) sec, respectively]. No significant change in speed was observed on day 5 [2.32 ± 0.58 (n = 34) vs. 2.77 ± 0.88 (n = 46) cm/sec, respectively] and day 8 [2.18 ± 0.51 (n = 34) vs. 2.32 ± 0.58 (n = 25), respectively] either. In contrast, the climbing speed of homozygous Dmon1Δ181, Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062, and C155-GAL4; Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 animals was significantly lower on day 1 [0.37 ± 0.28 (n = 21), 0.47 ± 0.23 (n = 31), and 0.42 ± 0.27 (n = 36) cm/sec, respectively; P < 0.001]. Pan-neuronal expression of Dmon1::HA in Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 rescued this defect: the average climbing speed of these animals (C155-GAL4; Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062; UAS-Dmon1::HA) was comparable to wild type [2.23 ± 0.64 cm/sec, (n = 44) (Figure 1C) even though a small decrease in speed was observed on day 5 (2.03 ± 0.64 cm/sec, (n = 42)] and day 8 [1.79 ± 0.38 cm/sec, (n = 39)]. We measured climbing ability of the mutants by calculating the percentage of flies able to climb 6 cm in 5 sec. In wild-type and Dmon1Δ181/+ animals, >97% and 98% of the flies, respectively, were able to climb this distance in the specified time, whereas <10% of Dmon1Δ181, Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062, and C155-GAL4;Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 animals showed robust climbing ability (Figure 1D). Neuronal expression of Mon1::HA using C155-GAL4 restored climbing ability to wild-type levels (98%, Figure 1D). Thus, despite the difference in severity of lifespan between homozygous Dmon1Δ181 and Dmon1Δ181/deficiency animals, there seemed to be little difference in their motor abilities. Dmon1Δ181 mutants express a truncated transcript that encodes the longin domain. The longin domain of Mon1 is known to form homodimers with itself and heterodimers with the longin domain of its partner protein, CCZ1. It is possible that formation of nonfunctional dimers in Dmon1Δ181 contributes to the increased serverity in lifespan (Nordmann et al. 2010).

Dmon1 mutants show accumulation of Rab5 positive endosomes:

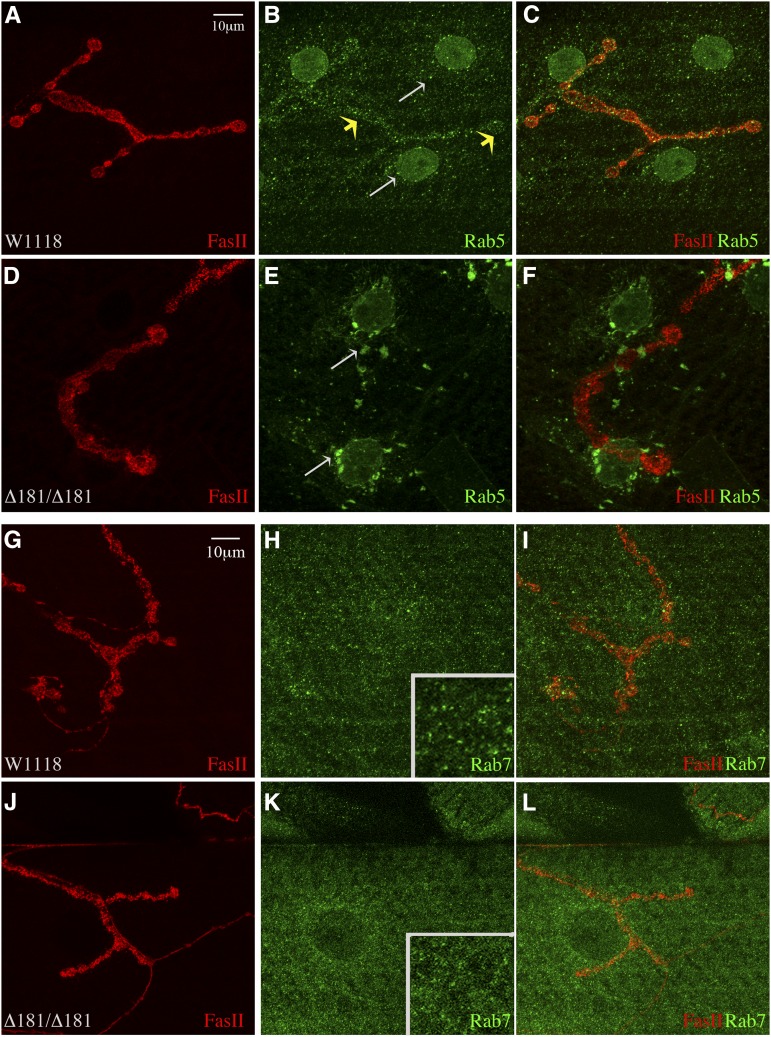

In Drosophila and C. elegans loss of Mon1/SAND1 leads to accumulation of Rab5. These mutants also fail to recruit Rab7 onto endosomes (Poteryaev et al. 2007, 2010; Kinchen and Ravichandran 2010). To determine if homozygous Dmon1Δ181 mutants exhibit a similar phenotype, we immunostained larval fillets for Rab5. In wild-type animals, small Rab5 positive puncta were seen distributed over the muscle (Figure 2, B and C, white arrows in B) and in the presynaptic regions (Figure 2, B and C, yellow arrows). In comparison, Dmon1Δ181 mutants showed large scattered aggregates of Rab5, representing enlarged endosomes (Figure 2, E and F, arrows). Similar Rab5 positive puncta were also seen in Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 and Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)6010 animals albeit smaller in size compared to Dmon1Δ181 (data not shown). Similar to Rab5, expression of Rab7 in muscles appeared punctate in wild-type larvae, suggesting vesicular localization (Figure 2H, inset); however, in Dmon1Δ181 mutants, Rab7 staining appeared more diffuse, suggesting that localization, but not expression, of this protein is likely to be affected (Figure 2K, inset). These results are consistent with the previous observations made in Drosophila and C. elegans, thus validating our loss-of-function allele (Kinchen and Ravichandran 2010; Yousefian et al. 2013).

Figure 2.

Altered Rab5 and Rab7 staining observed in Dmon1Δ181 mutants. (A–C) Muscle 4 synapse of w1118 stained with FasII (red) and anti-Rab5 (green). Small Rab5 positive puncta are seen in the presynaptic terminal (yellow arrows) and in muscles (white arrows). (D–F) Dmon1Δ181mutant. Rab5 positive aggregates are seen in the muscle and perinuclear regions (arrows in E). (G–L) NMJ at muscle 4 stained with FasII (red) and anti-Rab7 (green). (G–I) Small intense Rab7 punctae are present distributed over the muscle (H and inset) in w1118. In Dmon1Δ181 animals (J–L), Rab7 staining appears more diffuse than punctate (K and inset).

Dmon1Δ181 mutants exhibit altered synaptic morphology at the NMJ:

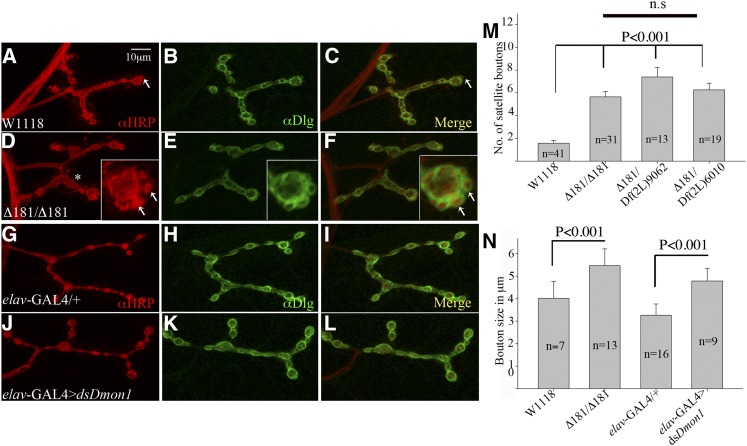

The strong motor defect in Dmon1Δ181 led us to examine the mutants for possible synaptic defects. A distinct change in synaptic morphology was observed at the neuromuscular junction in third instar larvae: most often, the boutons appeared large and surrounded by smaller supernumerary boutons (Figure 3, D–F, arrows in inset). At times, the boutons appeared odd shaped, indicating fusion of two adjacent boutons (Figure 3D, asterisk). Bouton size in mutant synapses was measured and compared to wild type by calculating the average diameter of boutons per synapse. In Dmon1Δ181 mutants the average bouton size was significantly larger (3N; 5.46 ± 0.74 μm, P < 0.001) than wild type (3N; 4.016 ± 0.75 μm). Despite the difference in size, we did not observe any significant difference in bouton number between the two genotypes [10.87 ± 3.46 (wild type) and 12 ± 3.7 (Dmon1Δ181)].

Figure 3.

Dmon1 mutants show altered synaptic morphology. A muscle 4 synapse. (A–C) w1118 and (D–F) Dmon1Δ181 mutant immunostained with anti-HRP (red) and anti-Dlg (green). Arrow in A and C shows a satellite bouton sometimes seen in wild type. (B and C) Dlg staining seen as a tight ring around the presynapse. (D) Dmon1Δ181 mutants show larger, sometimes odd-shaped boutons (asterisk). Small satellite boutons are seen surrounding larger boutons (insets in D–F, arrows). (E and F) Dlg staining is unaltered in the mutants (E and F). (G–I) elav-GAL4/+ and (J–L) elav-GAL4 > UAS-dsDmon1 animals immunostained with anti-HRP (red) and anti-Dlg (green). Expression of dsDmon1 results in bigger boutons (J). (M) Quantitation of satellite bouton number. Average number per synapse observed in w1118 is 1.61 ± 1.66 (wild type, n = 41). Dmon1Δ181, Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062, and Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)6010 animals show 5.6 ± 2.57, 7.38 ± 3.01, and 6.26 ± 2.51 satellite boutons per synapse, respectively (P < 0.001). (N) Quantitation of bouton size in wild type and Dmon1 mutants. The average bouton diameter (5.46 ± 0.74 μm) in Dmon1Δ181 animals is significantly larger than in wild type (4.01 ± 0.75 μm). Expression of dsDmon1 in neurons results in larger boutons (4.78 ± 0.55 μm) compared to controls (3.26 ± 0.49 μm). Error bars represent SD.

The number of satellite boutons was also scored in these mutants. Dmon1Δ181 animals showed a 250% increase in satellite boutons (5.6 ± 2.57 in Dmon1Δ181 vs. 1.61 ± 1.66 in wild type). A similar increase was observed in Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 (7.38 ± 3.01, 360%) and Dmon1Δ181/Df (2L)6010 animals (6.26 ± 2.51, 290%), confirming that the phenotype is indeed due to loss of Dmon1 (Figure 3M).

Neuronal knockdown of Dmon1 using RNAi also led to an increase in bouton size (Figure 3, J–L) with the average size being 4.78 ± 0.55 μm (P < 0.001) compared to 3.26 ± 0.49 μm in control animals (Figure 3N). However, unlike Dmon1Δ181, satellite boutons were not observed in these animals, suggesting that neuronal knockdown of Dmon1 alone may not be sufficient to give rise to the phenotype.

Expression of synaptic proteins Bruchpilot, GluRIIA, and GluRIIB is altered in Dmon1Δ181 mutants:

Mutations in trafficking genes are known to affect synaptic growth and neurotransmission (Littleton and Bellen 1995; Sanyal and Ramaswami 2002; Sweeney and Davis 2002; Dermaut et al. 2005). To further characterize the synaptic phenotype in Dmon1 mutants, expression of presynaptic and postsynaptic markers was examined using immunostaining. Bruchpilot (Brp; mAb nc82) is a core protein involved in the assembly of active zones at the presynapse (Wagh et al. 2006). Wild-type synapses showed strong punctate expression of Brp (Figure 4, A–C, inset in C). In homozygous Dmon1Δ181 mutants, a significant decrease in size (17.6%) and intensity (23%) of these puncta was observed (Figure 4, D–H).

Next, we checked if glutamate receptor levels at postsynaptic densities were altered in Dmon1Δ181 mutants. Synapses at the larval neuromuscular junction are glutamatergic. The postsynaptic ionotropic glutamate receptor consists of four subunits. Of these, subunits GluRIIC, GluRIID, and GluRIIE are invariant, with the fourth subunit being either GluRIIA or GluRIIB. Thus, two classes of glutamate receptor clusters are present at the synapse: those containing GluRIIA and others with GluRIIB (Marrus and DiAntonio 2004; Marrus et al. 2004). Interestingly, the mutants showed a strong increase in the intensity of GluRIIA staining (Figure 4, L–N, inset in N). GluRIIA positive puncta were also seen in the muscle or extrasynaptic sites (Figure 4M). We measured the increase in fluorescence intensity by calculating the average gray value of GluRIIA normalized to HRP (Menon et al. 2004). In Dmon1Δ181 and Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)6010 mutants, the increase in intensity was ∼74% and 56%, respectively, while Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 animals showed a 98% increase in GluRIIA intensity (Figure 4O).

The levels of GluRIIA and GluRIIB are reciprocally regulated at the synapse: an increase in GluRIIA leads to a decrease in GluRIIB (Petersen et al. 1997; DiAntonio et al. 1999; Sigrist et al. 2002; DiAntonio and Hicke 2004). We therefore checked Dmon1 mutants for expression of GluRIIB to determine if the mutation affected both GluR subunits. Consistent with the reciprocal regulation of these receptor subunits, homozygous Dmon1Δ181 mutants showed a distinct decrease in the intensity of GluRIIB at the synapse and absence of any extrasynaptic expression of the protein (Figure 4, S–U and U′). We measured the decrease in fluorescence intensity of GluRIIB normalized to FasciclinII, whose level seemed comparable between wild-type and mutant animals. Dmon1Δ181 mutants showed a 42% decrease in the intensity of GluRIIB, indicating the increase in receptor levels to be specific to GluRIIA, and that the mechanism controlling the homeostasis between GluRIIA and GluRIIB is unaffected.

We checked whether the increase in GluRIIA is due transcriptional up-regulation of the gene, by carrying out quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR. Interestingly, we did not observe any significant difference in transcript levels between wild-type and Dmon1Δ181 animals. The calculated average fold difference was 1 and 0.89 ± 0.22 (P = 0.47), respectively, suggesting that the specific increase in GluRIIA levels in the mutants is likely to be largely due to loss of posttranscriptional regulation.

Loss of neuronal Dmon1 is sufficient to alter the level of GluRIIA:

Next, to determine the relative contribution of the pre- and postsynaptic compartments to the GluRIIA phenotype, RNAi was used to down-regulate Dmon1 in neurons and muscles. Compared to wild type (Figure 5, A–C, arrow in inset), expression of Dmon1 dsRNA using C155-GAL4; elav-GAL4 line—a line carrying two copies of the panneuronal GAL4—resulted in a 70% increase in fluorescence intensity of GluRIIA (Figure 5, E–G) while a 32% increase was seen upon knockdown using the motor neuron-specific OK6-GAL4 (Figure 5N). In both experiments, an increase in GluRIIA positive extrasynaptic punctae was also observed. These results thus suggest that loss of Dmon1 in the presynaptic compartment is sufficient to trigger postsynaptic increase in GluRIIA.

To determine if neuronal overexpression of Dmon1 has an opposite effect on GluRIIA levels, we overexpressed UAS-Dmon1::HA using the C155-GAL4; elav-GAL4 line. A 24% decrease in receptor levels was observed (Figure 5, G, L, and M). A decrease in receptor levels was also observed when the Dmon1 was overexpressed in the muscle (data not shown). This indicates that while loss of neuronal Dmon1 is sufficient to phenocopy the mutant GluRIIA phenotype, receptor levels can be modulated pre and postsynaptically by DMon1.

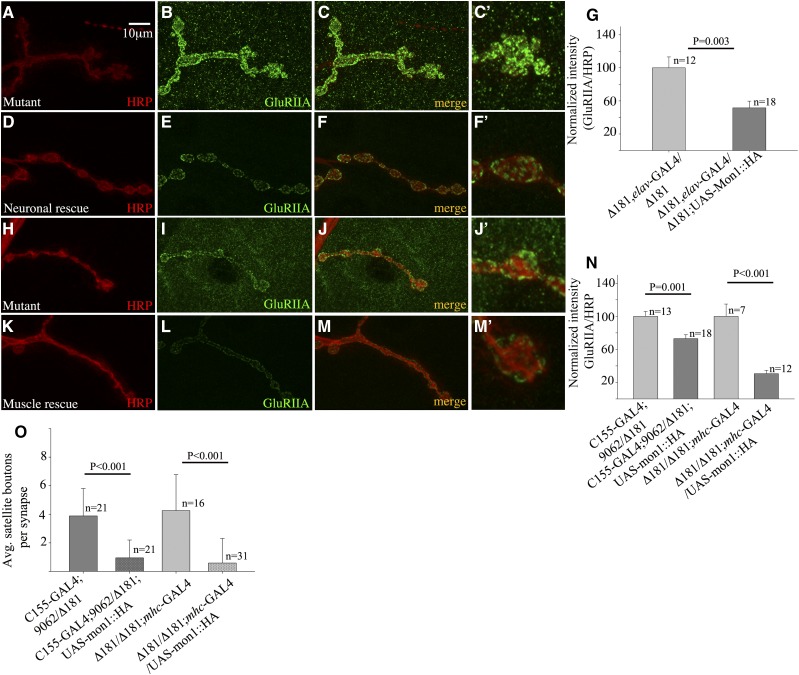

The synaptic phenotypes in Dmon1 mutants can be rescued by pre- and postsynaptic expression of Dmon1:

To further confirm that the increase in GluRIIA is indeed due to loss of Dmon1, we checked if expression of the gene in the mutants rescues the synaptic phenotype. We expressed UAS-Dmon1::HA presynaptically in homozygous Dmon1Δ181 and Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 larvae and examined the receptor levels in these animals. Compared to mutants (Dmon1Δ181, elav-GAL4/Dmon1Δ181; Figure 6, A–C and C′), “rescue” animals expressing UAS-Dmon1::HA, showed a 48% decrease in the intensity of GluRIIA (Figure 6, D–G). A significant decrease (27%) in GluRIIA levels was also observed in Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 mutants expressing Dmon1::HA (Figure 6N). Given the role of DMon1 in regulating endosomal trafficking it seemed possible that impaired cellular trafficking in the muscle might contribute to the increased accumulation of GluRIIA at the synapse. We therefore checked if postsynaptic expression of Dmon1 could rescue the GluRIIA phenotype. Expression of GluRIIA was significantly lowered in the “muscle-rescue” animals (Figure 6, K–M and M′). A near 70% decrease in the synaptic levels of GluRIIA was observed in these animals (0.12 ± 0.05 in rescue vs. 0.39 ± 0.15 in mutant control) (Figure 6N).

Figure 6.

Presynaptic and postsynaptic expression of Dmon1 rescues the GluRIIA phenotype in Dmon1 mutants. (A–C and C′) Control animal (Dmon1Δ181, elav-GAL4/Dmon1Δ181) with intense GluRIIA staining at the NMJ and muscles (C′). (D–F) Neuronal expression of Dmon1::HA in Dmon1Δ181 mutants rescues the GluRIIA phenotype (F and F′). (G) Normalized GluRIIA:HRP intensity. The intensity of GluRIIA is reduced by 48% in rescue animals. Error bars represent SEM. (N) Neuronal expression of UAS-Dmon1:HA in Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 leads to a 27% decrease in GluRIIA levels. Error bars represent SEM. (H–J and J′) Control (Dmon1Δ181/Dmon1Δ181; mhc-GAL4/+) synapse. HRP (red) and GluRIIA (green). (K–M and M′) Postsynaptic expression of Dmon1::HA in Dmon1Δ181 animals down-regulates GluRIIA expression. (N) Normalized GluRIIA:HRP intensity. A 70% decrease in intensity is observed in muscle-rescue animals. (O) Quantification of the satellite boutons. Fewer satellite boutons are observed in rescue animals. Error bars represent standard deviation (SD).

Interestingly, both presynaptic and postsynaptic expression of Dmon1 rescued the satellite bouton phenotype seen in the mutants (Figure 6O). Neuronal rescue of Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 led to a 75% decrease in the number of satellite boutons (3.76 ± 1.99 in mutant vs. 0.95 ± 1.24 in neuronal rescue). A comparable decrease (80%) was observed in mutants expressing Dmon1 postsynaptically (4.25 ± 2.51 in mutant “control” vs. 0.80 ± 1.6 in muscle rescue larvae) (Figure 6O). Together, these results indicate that the synaptic phenotypes in Dmon1 mutants is indeed due to loss of the gene, and both presynaptic as well as postsynaptic expression of the gene can rescue these defects.

DMon1 is secreted at the neuromuscular junction:

A study of the localization of Rabs in the ventral ganglion of third instar larvae suggests differential localization of each of these proteins (Chan et al. 2011). Components of the endocytic machinery are also present at the NMJ and regulate vesicle recycling and formation of active zone complexes (Wucherpfennig et al. 2003; Graf et al., 2009). To determine if DMon1 might play a role in any of the above processes, we sought to determine if the protein localizes to the synapse. We expressed UAS-Dmon1::HA in neurons and stained larval fillets using antibodies against the HA tag. In control (UAS-Dmon1::HA/+) animals, a few small puncta were seen dispersed around the area of the boutons (Figure 7, A–C and C′). Interestingly, in elav-GAL4>UAS-Dmon1::HA animals, strong HA positive puncta were observed surrounding the bouton (Figure 7, D–F and F′). The perisynaptic localization of Dmon1 was also observed when OK6-GAL4 was used to drive expression of UAS-Dmon1::HA. To visualize the localization of DMon::HA more clearly, a 3D rendering of the images were examined. As shown in Figure 7F′′ and F′′′, HA positive puncta were seen to be clearly surrounding the HRP positive presynaptic compartment. To further rule out possible staining artifacts caused by overexpression, localization of DMon1::HA was examined in Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 animals. Expression of DMon1::HA in a Dmon1 mutant background was also found to be perisynaptic, suggesting that the localization is unlikely to be an artifact caused by overexpression, although this needs to be tested more rigorously (Figure S3). We tried to determine if the localization of DMon1 is dependent on Rab11 since it is required for exosomal secretion (Raposo and Stoorvogel 2013). To do this, we coexpressed the tagged transgene with dominant negative Rab11 (DN-Rab11) in neurons. However, coexpression with DN-Rab11 led to widespread lethality, making it difficult evaluate this interaction.

We also examined anti-Dlg staining in animals overexpressing Dmon1. As opposed to the usual tight ring seen in control animals (Figure 7, G–I and I′), Dlg staining was found to be broad and diffuse in animals overexpressing Dmon1::HA (Figure 7, J–L and L′). These results suggest that DMon1 localizes to the synapse and is likely to be released from the presynaptic compartment.

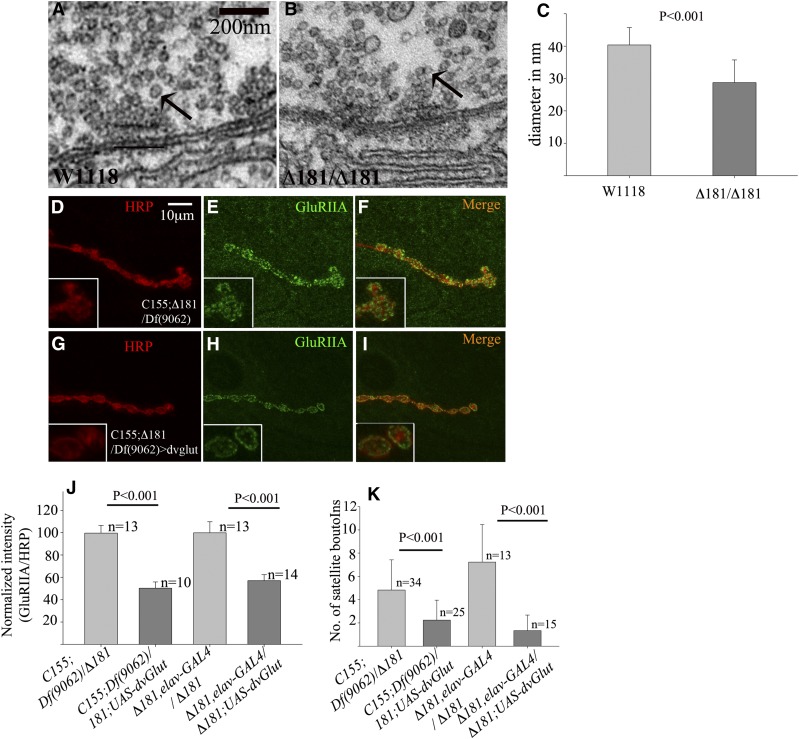

Neurotransmitter vesicle size is reduced in Dmon1 mutants:

Expression of GluRIIA is dependent on cell–cell contact between the nerve and muscle (Karr et al. 2009; Ganesan et al. 2011; Fukui et al. 2012). Further, homeostatic mechanisms regulate neurotransmitter release and postsynaptic receptor composition and density in response to presynaptic activity (Petersen et al. 1997; Davis et al. 1998; Schmid et al. 2008). To gain further insight into the possible cause of increased GluRIIA accumulation, we examined the ultrastructure of boutons from wild type and Dmon1Δ181 mutants. Interestingly, the mutants showed a distinct decrease in the size of synaptic vesicles (Figure 8, B and C). In wild type, the average vesicle diameter measured 40.35 ± 5.32 nm—a value comparable to what has been previously observed (Daniels et al. 2006); the mutants showed a 28.77% decrease in diameter with the average diameter being 28.74 ± 7 nm.

Figure 8.

Expression of dvglut in Dmon1 mutants suppresses the GluRIIA phenotype. (A and B) Electron micrograph of the active zone region of w1118 (A) and Dmon1Δ181 mutant (B) at identical magnification. Synaptic vesicles (arrows in A and B) are smaller in the mutants. (C) Average vesicle diameter in mutants (28.74 ± 7 nm) is 28.7% smaller than wild type (40.35 ± 5.32 nm). (D–I) Control (C155; Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062) and mutants overexpressing dvglut stained with HRP (red) and anti-GluRIIA (green). (G–I) Expression of UAS-dvGlut decreases GluRIIA levels in the mutant (I and inset). Bar in A, 10 μm. (J) Normalized GluRIIA:HRP intensity. Overexpression of dvglut leads to a 49% and 43% decrease in GluRIIA levels in C155-GAL4;Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 and Dmon1Δ181, elav-GAL4/Dmon1Δ181 animals, respectively. Error bars represent SEM. (K) Quantification of satellite bouton number in Dmon1 mutants and mutants overexpressing vglut. A significant decrease in satellite boutons is observed in the mutants.

One of the factors regulating vesicle size is dvglut, which encodes the vesicular glutamate transporter. Loss of dvglut leads to a decrease in size of synaptic vesicles while overexpression results in an increase in vesicle size and amplitude of spontaneous release (Daniels et al. 2004, 2006). We did not observe any significant change in vGlut/FasII ratios in Dmon1Δ181 (2.05 ± 0.67 in W1118 vs. 1.85 ± 0.72 in Dmon1Δ181). To determine if increasing glutamate release can down-regulate GluRIIA expression, we overexpressed dvglut in Dmon1 mutants and examined its effect on GluRIIA levels. Indeed, presynaptic overexpression of vglut in Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 animals resulted in a 49% decrease in postsynaptic GluRIIA levels and loss of extrasynaptic GluRIIA (Figure 8, G–I and J). A comparable decrease (43%) in receptor levels was observed when overexpression was carried out in a Dmon1Δ181 background (Figure 8J). Expression of vGlut also suppressed the satellite bouton phenotype in Dmon1 mutants (Figure 8K). A 50% decrease in satellite bouton number was observed in Dmon1Δ181/Df(2L)9062 animals [control (4.82 ± 2.6) vs. rescue (2.24 ± 1.71)] while a 80% decrease was observed in homozygous Dmon1Δ181 animals [mutant control (7.23 ± 3.21) vs. rescue (1.33 ± 1.34)]. This suggests that altered glutamate release in Dmon1 mutants could contribute to the increase in GluRIIA levels and postsynaptic homeostatic mechanisms are not affected in these mutants.

Discussion

Neurotransmitter release at the synapse is modulated by factors that control synaptic growth, synaptic vesicle recycling, and receptor turnover at postsynaptic sites (Sweeney and Davis 2002; Glodowski et al. 2007; Kim and Kandler 2010; Fernandes et al. 2014). Endolysosomal trafficking modulates the function of these factors and therefore plays an important role in regulating synaptic development and function. Intracellular trafficking is regulated by Rabs, which are small GTPases. These proteins control specific steps in the trafficking process. A clear understanding of the role of Rabs at the synapse is still nascent. Drosophila has 31 Rabs, and most of these are expressed in the nervous system (Chan et al. 2011). Rab5 and Rab7, present on early and late endosomes, respectively, are critical regulators of endolysosomal trafficking and loss of this regulation affects neuronal viability underscored by the fact that mutations in Rab7 are associated with neurodegeneration (Verhoeven et al. 2003). Rab5 along with Rab3 is present on synaptic vesicles, and both play a role in regulating neurotransmitter release (Fischer Von Mollard et al. 1994a,b; Sudhof 1995). In Drosophila, Rab3 is involved in the assembly of active zones by controlling the level of both Bruchpilot—a core active zone protein—and the calcium channels surrounding the active zone (Graf et al. 2009). In hippocampal and cortex neurons, Rab5 facilitates LTD through removal of AMPA receptors from the synapse (Brown et al. 2005; Zhong et al. 2008). In Drosophila, Rab5 regulates neurotransmission; it also functions to maintain synaptic vesicle size by preventing homotypic fusion (Shimizu et al. 2003; Wucherpfennig et al. 2003). Compared to Rab5 or Rab3, less is known about the roles of Rab7 at the synapse. In spinal cord motor neurons, Rab7 mediates sorting and retrograde transport of neurotrophin-carrying vesicles (Deinhardt et al. 2006). In Drosophila, tbc1D17—a known GAP for Rab7—affects GluRIIA levels (Lee et al. 2013); the effect of this on neurotransmission has not been evaluated. Excessive trafficking via the endolysosomal pathway also affects neurotransmission. This has been observed in mutants for tbc1D24—a GAP for Rab35. A high rate of turnover of synaptic vesicle proteins in these mutants is seen to increase neurotransmitter release (Uytterhoeven et al. 2011; Fernandes et al. 2014).

In this study we have examined the synaptic role of DMon1—a key regulator of endosomal maturation. Multiple synaptic phenotypes are found associated with Dmon1 loss of function, and one of these is altered synaptic morphology. Boutons in Dmon1 mutants are larger with more satellite or supernumerary boutons (Figure 3)—a phenotype strongly associated with endocytic mutants (Dickman et al. 2006). Formation of satellite boutons is thought to occur due to loss of bouton maturation, with the initial step of bouton budding being controlled postsynaptically and the maturation step being regulated presynaptically (Lee and Wu 2010). Supporting this, a recent study shows that miniature neurotransmission is required for bouton maturation (Choi et al. 2014). The presence of excess satellite boutons in Dmon1 mutants suggests that the number of “miniature” events is likely to be affected in these mutants. The fact that we can rescue this phenotype upon expression of vGlut supports this possibility (Figure 8). However, this does not fit with the observed decrease in size and intensity of Brp positive puncta in these mutants. Active zones with low or nonfunctional Brp are known to be more strongly associated with increased spontaneous neurotransmission (Melom et al. 2013; Peled et al. 2014). Considering the involvement of postsynaptic signaling in initiating satellite bouton formation, we think altered neurotransmission possibly together with impaired postsynaptic or retrograde signaling, contributes to the altered synaptic morphology in Dmon1 mutants. This may also explain why we fail to observe satellite boutons in neuronal RNAi animals.

A striking phenotype associated with loss of Dmon1 is the increase in GluRIIA levels (Figure 4). This phenotype seems presynaptic in origin since neuronal loss of Dmon1 is sufficient to increase GluRIIA levels (Figure 5). Is the increase in GluRIIA due to trafficking defects in the neuron? This seems unlikely for the following reasons: First, it has been shown that although neuronal overexpression of wild-type and dominant negative Rab5 alters evoked response in a reciprocal manner, there is no change in synaptic morphology, glutamate receptor localization and density, or change in synaptic vesicle size (Wucherpfennig et al. 2003). The role of Rab7 at the synapse is less clear. In a recent study, loss of tbc1D15-17, which functions as a GAP for Rab7, was shown to increase GluRIIA levels at the synapse. Selective knockdown of the gene in muscles, and not neurons, was seen to increase GluRIIA levels, indicating that the function of the gene is primarily postsynaptic (Lee et al. 2013). These data are not consistent with our results from neuronal knockdown of Dmon1, suggesting that the presynaptic role of Dmon1 in regulating GluRIIA levels is likely to be independent of Rab5 and Rab7 and therefore novel.

Our experiments to evaluate the postsynaptic role of Dmon1 have been less clear. Although we see a modest increase in GluRIIA levels upon knockdown in muscles, the increase is not always significant when compared to controls (data not shown). However, the fact that muscle expression of Dmon1 can rescue the GluRIIA phenotype in the mutant (Figure 6) suggests that it is likely to be one of the players in regulating GluRIIA postsynaptically. Further, it is to be noted, that while overexpression of vGlut leads to down-regulation of the receptor at the synapse (Figure 8), the receptors do not seem to get trapped in the muscle, suggesting that multiple pathways are likely to be involved in regulating receptor turnover in the muscle, and the DMon1–Rab7-mediated pathway may be just one of them.

How might neuronal Dmon1 regulate receptor expression? One possibility is that the increase in receptor levels is a postsynaptic homeostatic response to defects in neurotransmission, given that Dmon1∆181 mutants have smaller synaptic vesicles. However, in dvglut mutants, presence of smaller synaptic vesicles does not lead to any change in GluRIIA levels, given that receptors at the synapse are generally expressed at saturating levels (Daniels et al. 2006). Therefore, it seems unlikely that the increase in GluRIIA is part of a homeostatic response, although one cannot rule this out completely. The other possibility is that DMon1 is part of a transsynaptic signaling mechanism that regulates GluRIIA levels in a post-transcriptional manner. The observation that presynaptically expressed DMon1 localizes to postsynaptic regions (Figure 7) and our results from neuronal RNAi and rescue experiments support this possibility. The involvement of transsynaptic signaling in regulating synaptic growth and function has been demonstrated in the case of signaling molecules such as Ephrins, Wingless, and Syt4 (Contractor et al. 2002; Korkut and Budnik 2009; Korkut et al. 2013). In Drosophila, both Wingless and Syt4 are released by the presynaptic terminal via exosomes to mediate their effects in the postsynaptic compartment. We hypothesize that DMon1 released from the boutons either directly regulates GluRIIA levels or facilitates the release of an unknown factor required to maintain receptor levels. The function of DMon1 in the muscle is likely to be more consistent with its role in cellular trafficking and may mediate one of the pathways regulating GluRIIA turnover. These possibilities will need to be tested to gain a mechanistic understanding of receptor regulation by Dmon1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Thomas Klein, Jahan Forough Yousefian, Hermann Aberle and Aaron DiAntonio for antibodies and fly reagents; Gaiti Hasan, L. S. Shashidhara, and Richa Rikhy for helpful discussions; Girish Deshpande for critical comments; the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center and the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Centre for fly stocks; the Bloomington Drosophila Genome Research Center for cDNA clones; the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research (IISER) for use of the microscopy facility; and National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Bangalore, and Centre for Cellular and Molecular Platforms (C-CAMP), Bangalore, for help with the TEM facility. This work was supported by funds from the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India (GOI), Agharkar Research Institute (ARI), Pune, to A.R.; Wellcome Trust DBT Indian Alliance (WT-DBT-IA) to G.S.R.; intramural funds from IISER to G.S.R.; Council of Industrial and Scientific Research, GOI, a Senior Research Fellowship to S.D.; and a fellowship from the University Grants Commission, GOI to Kumari Shweta. G.S.R. is a WT-DBT-IA Intermediate Fellow. Author contributions: A.R. conceived and designed the experiments; A.R., S.D., A.B., K.S., and P.S. performed the experiments; A.R., G.S.R., S.D., A.B., K.S. and P.S. analyzed the data; and A.R. and G.S.R. wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: I. Hariharan

Supporting information is available online at www.genetics.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1534/genetics.115.177402/-/DC1.

Literature Cited

- Brown T. C., Tran I. C., Backos D. S., Esteban J. A., 2005. NMDA receptor-dependent activation of the small GTPase Rab5 drives the removal of synaptic AMPA receptors during hippocampal LTD. Neuron 45: 81–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan C. C., Scoggin S., Wang D., Cherry S., Dembo T., et al. , 2011. Systematic discovery of Rab GTPases with synaptic functions in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 21: 1704–1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinchore Y., Mitra A., Dolph P. J., 2009. Accumulation of rhodopsin in late endosomes triggers photoreceptor cell degeneration. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi B. J., Imlach W. L., Jiao W., Wolfram V., Wu Y., et al. , 2014. Miniature neurotransmission regulates Drosophila synaptic structural maturation. Neuron 82: 618–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contractor A., Rogers C., Maron C., Henkemeyer M., Swanson G. T., et al. , 2002. Trans-synaptic Eph receptor-ephrin signaling in hippocampal mossy fiber LTP. Science 296: 1864–1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels R. W., Collins C. A., Gelfand M. V., Dant J., Brooks E. S., et al. , 2004. Increased expression of the Drosophila vesicular glutamate transporter leads to excess glutamate release and a compensatory decrease in quantal content. J. Neurosci. 24: 10466–10474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniels R. W., Collins C. A., Chen K., Gelfand M. V., Featherstone D. E., et al. , 2006. A single vesicular glutamate transporter is sufficient to fill a synaptic vesicle. Neuron 49: 11–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis G. W., DiAntonio A., Petersen S. A., Goodman C. S., 1998. Postsynaptic PKA controls quantal size and reveals a retrograde signal that regulates presynaptic transmitter release in Drosophila. Neuron 20: 305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deinhardt K., Salinas S., Verastegui C., Watson R., Worth D., et al. , 2006. Rab5 and Rab7 control endocytic sorting along the axonal retrograde transport pathway. Neuron 52: 293–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermaut B., Norga K. K., Kania A., Verstreken P., Pan H., et al. , 2005. Aberrant lysosomal carbohydrate storage accompanies endocytic defects and neurodegeneration in Drosophila benchwarmer. J. Cell Biol. 170: 127–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiAntonio A., Hicke L., 2004. Ubiquitin-dependent regulation of the synapse. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27: 223–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiAntonio A., Petersen S. A., Heckmann M., Goodman C. S., 1999. Glutamate receptor expression regulates quantal size and quantal content at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci. 19: 3023–3032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiAntonio A., Haghighi A. P., Portman S. L., Lee J. D., Amaranto A. M., et al. , 2001. Ubiquitination-dependent mechanisms regulate synaptic growth and function. Nature 412: 449–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman D. K., Lu Z., Meinertzhagen I. A., Schwarz T. L., 2006. Altered synaptic development and active zone spacing in endocytosis mutants. Curr. Biol. 16: 591–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobie F., Craig A. M., 2007. A fight for neurotransmission: SCRAPPER trashes RIM. Cell 130: 775–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes A. C., Uytterhoeven V., Kuenen S., Wang Y. C., Slabbaert J. R., et al. , 2014. Reduced synaptic vesicle protein degradation at lysosomes curbs TBC1D24/sky-induced neurodegeneration. J. Cell Biol. 207: 453–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Monreal M., Brown T. C., Royo M., Esteban J. A., 2012. The balance between receptor recycling and trafficking toward lysosomes determines synaptic strength during long-term depression. J. Neurosci. 32: 13200–13205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer von Mollard G., Stahl B., Li C., Sudhof T. C., Jahn R., 1994a Rab proteins in regulated exocytosis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 19: 164–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer von Mollard G., Stahl B., Walch-Solimena C., Takei K., Daniels L., et al. , 1994b Localization of Rab5 to synaptic vesicles identifies endosomal intermediate in synaptic vesicle recycling pathway. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 65: 319–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui A., Inaki M., Tonoe G., Hamatani H., Homma M., et al. , 2012. Lola regulates glutamate receptor expression at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Biol. Open 1: 362–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan S., Karr J. E., Featherstone D. E., 2011. Drosophila glutamate receptor mRNA expression and mRNP particles. RNA Biol. 8: 771–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glodowski D. R., Chen C. C., Schaefer H., Grant B. D., Rongo C., 2007. RAB-10 regulates glutamate receptor recycling in a cholesterol-dependent endocytosis pathway. Mol. Biol. Cell 18: 4387–4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf E. R., Daniels R. W., Burgess R. W., Schwarz T. L., DiAntonio A., 2009. Rab3 dynamically controls protein composition at active zones. Neuron 64: 663–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckscher E. S., Fetter R. D., Marek K. W., Albin S. D., Davis G. W., 2007. NF-kappaB, IkappaB, and IRAK control glutamate receptor density at the Drosophila NMJ. Neuron 55: 859–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karr J., Vagin V., Chen K., Ganesan S., Olenkina O., et al. , 2009. Regulation of glutamate receptor subunit availability by microRNAs. J. Cell Biol. 185: 685–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G., Kandler K., 2010. Synaptic changes underlying the strengthening of GABA/glycinergic connections in the developing lateral superior olive. Neuroscience 171: 924–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinchen J. M., Ravichandran K. S., 2010. Identification of two evolutionarily conserved genes regulating processing of engulfed apoptotic cells. Nature 464: 778–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkut C., Budnik V., 2009. WNTs tune up the neuromuscular junction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10: 627–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkut C., Li Y., Koles K., Brewer C., Ashley J., et al. , 2013. Regulation of postsynaptic retrograde signaling by presynaptic exosome release. Neuron 77: 1039–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. J., Jang S., Nahm M., Yoon J. H., Lee S., 2013. Tbc1d15-17 regulates synaptic development at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Mol. Cells. 36: 163–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Wu C. F., 2010. Orchestration of stepwise synaptic growth by K+ and Ca2+ channels in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 30: 15821–15833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton J. T., Bellen H. J., 1995. Presynaptic proteins involved in exocytosis in Drosophila melanogaster: a genetic analysis. Invert. Neurosci. 1: 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrus S. B., DiAntonio A., 2004. Preferential localization of glutamate receptors opposite sites of high presynaptic release. Curr. Biol. 14: 924–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrus S. B., Portman S. L., Allen M. J., Moffat K. G., DiAntonio A., 2004. Differential localization of glutamate receptor subunits at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci. 24: 1406–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew S. J., Kerridge S., Leptin M., 2009. A small genomic region containing several loci required for gastrulation in Drosophila. PLoS One 4: e7437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melom J. E., Akbergenova Y., Gavornik J. P., Littleton J. T., 2013. Spontaneous and evoked release are independently regulated at individual active zones. J. Neurosci. 33: 17253–17263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon K. P., Sanyal S., Habara Y., Sanchez R., Wharton R. P., et al. , 2004. The translational repressor Pumilio regulates presynaptic morphology and controls postsynaptic accumulation of translation factor eIF-4E. Neuron 44: 663–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon K. P., Andrews S., Murthy M., Gavis E. R., Zinn K., 2009. The translational repressors Nanos and Pumilio have divergent effects on presynaptic terminal growth and postsynaptic glutamate receptor subunit composition. J. Neurosci. 29: 5558–5572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordmann M., Cabrera M., Perz A., Brocker C., Ostrowicz C., et al. , 2010. The Mon1-Ccz1 complex is the GEF of the late endosomal Rab7 homolog Ypt7. Curr. Biol. 20: 1654–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peled E. S., Newman Z. L., Isacoff E. Y., 2014. Evoked and spontaneous transmission favored by distinct sets of synapses. Curr. Biol. 24: 484–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen S. A., Fetter R. D., Noordermeer J. N., Goodman C. S., DiAntonio A., 1997. Genetic analysis of glutamate receptors in Drosophila reveals a retrograde signal regulating presynaptic transmitter release. Neuron 19: 1237–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteryaev D., Fares H., Bowerman B., Spang A., 2007. Caenorhabditis elegans SAND-1 is essential for RAB-7 function in endosomal traffic. EMBO J. 26: 301–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poteryaev D., Datta S., Ackema K., Zerial M., Spang A., 2010. Identification of the switch in early-to-late endosome transition. Cell 141: 497–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G., Stoorvogel W., 2013. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 200: 373–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnaparkhi A., Lawless G. M., Schweizer F. E., Golshani P., Jackson G. R., 2008. A Drosophila model of ALS: human ALS-associated mutation in VAP33A suggests a dominant negative mechanism. PLoS One 3: e2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal S., Ramaswami M., 2002. Spinsters, synaptic defects, and amaurotic idiocy. Neuron 36: 335–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid A., Hallermann S., Kittel R. J., Khorramshahi O., Frolich A. M., et al. , 2008. Activity-dependent site-specific changes of glutamate receptor composition in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 11: 659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwood N. T., Sun Q., Xue M., Zhang B., Zinn K., 2004. Drosophila spastin regulates synaptic microtubule networks and is required for normal motor function. PLoS Biol. 2: e429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu H., Kawamura S., Ozaki K., 2003. An essential role of Rab5 in uniformity of synaptic vesicle size. J. Cell Sci. 116: 3583–3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist S. J., Thiel P. R., Reiff D. F., Lachance P. E., Lasko P., et al. , 2000. Postsynaptic translation affects the efficacy and morphology of neuromuscular junctions. Nature 405: 1062–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist S. J., Thiel P. R., Reiff D. F., Schuster C. M., 2002. The postsynaptic glutamate receptor subunit DGluR-IIA mediates long-term plasticity in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 22: 7362–7372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigrist S. J., Reiff D. F., Thiel P. R., Steinert J. R., Schuster C. M., 2003. Experience-dependent strengthening of Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. J. Neurosci. 23: 6546–6556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudhof T. C., 1995. The synaptic vesicle cycle: a cascade of protein-protein interactions. Nature 375: 645–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney S. T., Davis G. W., 2002. Unrestricted synaptic growth in spinster-a late endosomal protein implicated in TGF-beta-mediated synaptic growth regulation. Neuron 36: 403–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uytterhoeven V., Kuenen S., Kasprowicz J., Miskiewicz K., Verstreken P., 2011. Loss of skywalker reveals synaptic endosomes as sorting stations for synaptic vesicle proteins. Cell 145: 117–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeven K., De Jonghe P., Coen K., Verpoorten N., Auer-Grumbach M., et al. , 2003. Mutations in the small GTP-ase late endosomal protein RAB7 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2B neuropathy. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72: 722–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagh D. A., Rasse T. M., Asan E., Hofbauer A., Schwenkert I., et al. , 2006. Bruchpilot, a protein with homology to ELKS/CAST, is required for structural integrity and function of synaptic active zones in Drosophila. Neuron 49: 833–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. W., Stromhaug P. E., Shima J., Klionsky D. J., 2002. The Ccz1-Mon1 protein complex is required for the late step of multiple vacuole delivery pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 47917–47927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. W., Stromhaug P. E., Kauffman E. J., Weisman L. S., Klionsky D. J., 2003. Yeast homotypic vacuole fusion requires the Ccz1-Mon1 complex during the tethering/docking stage. J. Cell Biol. 163: 973–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wucherpfennig T., Wilsch-Brauninger M., Gonzalez-Gaitan M., 2003. Role of Drosophila Rab5 during endosomal trafficking at the synapse and evoked neurotransmitter release. J. Cell Biol. 161: 609–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yousefian J., Troost T., Grawe F., Sasamura T., Fortini M., et al. , 2013. Dmon1 controls recruitment of Rab7 to maturing endosomes in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 126: 1583–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong P., Liu W., Gu Z., Yan Z., 2008. Serotonin facilitates long-term depression induction in prefrontal cortex via p38 MAPK/Rab5-mediated enhancement of AMPA receptor internalization. J. Physiol. 586: 4465–4479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Supplemental information present in Figure S1, Figure S2, and Figure S3.