Abstract

Childhood aggression-disruptiveness, chronic peer rejection, and deviant friendships were examined as predictors of early-adolescent rule breaking behaviors. Using a sample of 383 children (193 girls and 190 boys) who were followed from ages 6 to 14, peer rejection trajectories were identified and incorporated into a series of alternative models to assess how chronic peer rejection and deviant friendships mediate the association between stable childhood aggression-disruptiveness and early-adolescent rule breaking. There were multiple mediated pathways to rule breaking that included both behavioral and relational risk factors and findings were consistent for boys and girls. Results have implications for better understanding the influence of multiple social processes in the continuity of antisocial behaviors from middle childhood to early adolescence.

Research on children’s antisocial behavior (ASB) reveals that distinguishing its forms may have important conceptual implications pertaining to its development over time and etiology (Tremblay, 2010). In regards to its development, certain forms of ASB are more likely to be manifested at distinct developmental periods. During childhood, aggression and disruptiveness (AD) tend to be more frequent (Tremblay, 2010). In contrast, non-aggressive rule-breaking behaviors (RB) including vandalism, theft, alcohol and drug use and other status offenses (e.g., truancy, staying out late at night, and running away from home) tend to become more prevalent in adolescence (Burt, 2012; Stanger, Achenbach, & Verhulst, 1997; van Lier, Vitaro, Barker, Hoot, & Tremblay, 2009). A longitudinal study by van Lier et al. (2009) which examined the developmental trajectories of children’s aggressive and non-aggressive RB behaviors (i.e., vandalism, theft and substance use) from ages 10 to 15 found support for this premise. These investigators found that children with high physical aggression trajectories were highly aggressive in age 10 and maintained this behavioral style through age 15. In contrast, children who engaged in RB had a trajectory that exhibited a sharp increase during this age period. That is, they had low levels of RB at age 10 and showed a considerable increase in these behaviors which peaked around ages 14 to 15.

Thus, although it is possible that some children begin to engage in RB before adolescence, these behaviors tend to occur infrequently among younger children for several reasons. First, RB tends to require greater cognitive capacities than AD which are typically not attained until late childhood or early adolescence (Burt, 2012). Second, early adolescents spend more time in unsupervised settings with peers, and experience a social context characterized by relational processes which afford greater opportunities and pressures to engage in RB. More specifically, investigators have postulated that two forms of adverse peer relational processes—peer rejection and having deviant friends—increase the risk for RB (Patterson et al., 1989; Vitaro, Pedersen, & Brendgen, 2007). However, controversy and debate remains about: (a) how these forms of adverse peer relationships impact the development of RB, (b) how early behavioral risks (i.e., childhood AD) develop into adolescent RB, and (c) the priority (i.e., relative importance of) and means by which these relational versus behavioral risks contribute to RB. Some of this controversy pertains to whether behavioral changes from AD to RB reflect developmentally salient or age-appropriate manifestations of an underlying and stable antisocial behavioral style (i.e., a stable individual characteristic; see Moffitt, 1993) or whether these changes result from maladaptive socialization experiences that children experience amongst peers, or both.

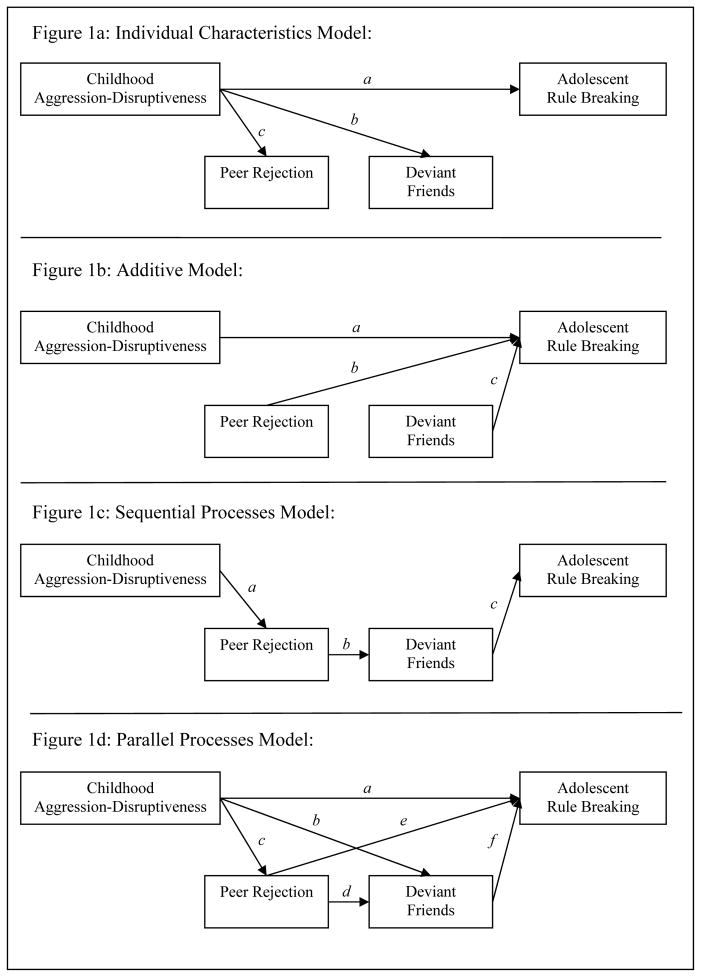

The purpose of this study is to address these controversies by evaluating alternative models that explain how childhood adverse peer relations (i.e., peer rejection and deviant friends) and AD are predictive of early-adolescent RB. In the following sections, the implications of four alternative theoretical models are considered. These models are referred to as: 1) the individual characteristics model, 2) the additive model, 3) the sequential processes model and 4) the parallel processes model.

Individual Characteristics Model

The primary premise of the individual characteristics model (see Vitaro, Tremblay, Kerr, Pagani, & Bukowski, 1997; also termed “incidental” model; see Parker & Asher, 1987) is that some children possess a stable antisocial disposition that, behaviorally, varies in its expression as they mature (age-dependent manifestations; e.g., AD in childhood and RB in adolescence; see Moffitt, 1993). Thus, this model’s predictive implications (see Figure 1a) are that once early and stable AD is taken into account (path a in Figure 1a), childhood peer relational difficulties add little or nothing to the prediction of adolescent RB. In other words, peer relational difficulties are seen as consequences of children’s AD (paths b and c) but are not causes of RB (Woodward & Fergusson, 1999). This perspective does not assume that friends socialize each other to become more deviant (i.e., deviant socialization hypothesis) but rather construes these relationships only in terms of selection processes (i.e., behavioral homophily drives selection, but does not promote increased deviance).

Figure 1.

Conceptual models depicting alternative pathways from early aggression-disruptiveness to adolescent rule breaking behaviors and the role of peer relational difficulties (i.e., peer rejection and deviant friends).

Additive Model

This model originates from a child and environment perspective (see Ladd, 2003) and implies that children’s behavioral propensities and peer relations jointly influence adjustment. It assumes that risks for maladjustment increase as children experience the cumulative effects of multiple and/or sustained risk factors (Ladd, 2006). Predictive implications for this model are that childhood AD, peer rejection and deviant friendships contribute to RB (paths a, b, and c in Figure 1b), and the effects of each risk factor are distinct relative to those of the others. Thus, this model differs from the individual characteristics model in two important respects. First, it incorporates the deviant socialization hypothesis; children who affiliate with deviant peers are less likely to experience prosocial forms of socialization within normative peer groups and more likely to participate in friendships that encourage RB. Deviant friends not only reinforce each other’s existing ASB but also foster (e.g., model) new and different types of ASB (e.g., RB), a process referred to as deviancy training (Dishion, Spracklen, Andrews, & Patterson, 1996). Second, the additive model assumes that peer rejection contributes to the formation of RB and does so in a way that cannot be explained by children’s AD or deviant friendships. For instance, childhood peer rejection can engender maladaptive emotional and cognitive processes, such as feelings of resentment towards others, perceived exclusion, marginalization and alienation, perceptions of social disconnectedness and a lack of belongingness—all of which may be risk factors for later RB (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Coie, 2004; Parker & Asher, 1987).

Sequential Processes Model

This model, the earliest forms of which were proposed by Patterson et al. (1989), holds that childhood AD is not directly linked with adolescent RB, but rather depends on maladaptive socialization experiences that occur within children’s deviant peer groups. It is postulated that childhood risk factors influence later RB behaviors through a sequence of mediated relations (hence the term “sequential processes”), the form of which is as follows: childhood AD → peer rejection → deviant friends → adolescent RB (paths a, b, and c in Figure 1c). Three notable premises differentiate this model from the individual characteristics and additive models. First, rather than predicting adolescent RB behaviors directly, early AD is hypothesized to lead to peer rejection. Second, the maladaptive relational experiences related to peer rejection are seen as fostering the development of another maladaptive form of relationship (i.e., forming friendships with deviant peers). The logic underlying this supposition is that because rejected children have limited opportunities to form friendships with non-rejected children they seek friendships among those with similar behavioral propensities and social status and are more likely to affiliate with deviant peers (Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, & Skinner, 1991). Third, peer rejection is not seen as an inert (as in the individual characteristics model) or a direct influence on adolescent RB (as in the additive model). Rather, peer rejection’s link with RB is indirect such that it increases the likelihood that children form deviant friendships (Patterson et al., 2000).

Parallel Processes Model

This model was initially proposed by Hay et al. (2004) as an expansion of the sequential processes and additive models. It more completely accounts for the multiple complementary pathways from childhood AD to adolescent RB and there are several premises that differentiate it from the other models. First, this model stipulates a mediated pathway from early AD to peer rejection which in turn directly predicts adolescent RB (paths c and e in Figure 1d). This pathway implies that childhood peer rejection contributes to the development of adolescent RB beyond its role in promoting deviant friendships. That is, not only are rejected children more likely to form deviant friendships, but rejection also increases the risk for RB in unique ways that cannot be accounted for by the deviant socialization processes that occur among deviant friends. Second, this model stipulates a mediated pathway from early AD to deviant friends which in turn predicts adolescent RB (paths b and f). This pathway implies that children with early AD are more likely to form friendships with deviant peers even if they are not rejected by normative peers. Considering the role of behavioral homophily in the formation of children’s friendships, it is plausible that aggressive children may select other deviant children as friends whether or not they are rejected from more normative peer groups. Taken together, these two pathways imply that peer relational adversities function in complementary (i.e., parallel) ways to predict adolescent RB rather than only in a sequential manner (hence the term “parallel processes”). In addition to these two indirect pathways, this model also accounts for the sequential peer-processes pathway (paths c, d and f) and for the direct relation between AD and RB (path a).

Current State of Evidence

Many investigators have examined parts of these models; however, rarely have they tested them in their entirety using prospective longitudinal designs that span from childhood to adolescence. Among the few investigations that have used prospective longitudinal designs, findings have been inconsistent. For instance, Laird et al. (2001) and Sturaro et al. (2011) found that peer rejection (but not deviant friends) mediated the association between early externalizing problems and later externalizing problems (consisting of both aggressive and non-aggressive forms of ASB). Vitaro et al. (2007) found support for a sequential peer process for violent delinquency in adolescence (i.e., early disruptive behaviors → peer rejection → friends’ disruptiveness → violent delinquency); however, peer rejection was not directly associated with violent delinquency and the sequential process pathway was not found when they examined adolescent substance use as the outcome measure (instead of violent delinquency). Snyder et al. (2008) found that deviancy training mediated the association between early conduct problems and subsequent covert, but not overt, conduct problems; however, these investigators did not examine deviant friendships per se. In all of these investigations earlier ASB continued to predict subsequent ASB, even after accounting for mediating peer processes.

Collectively, results from these investigations reveal inconsistencies pertaining to the means by which adverse peer relations were predictive of ASB, and whether the influence of peer rejection, compared to deviant friendships, would have a more detrimental effect. Moreover, because it is not possible to ascertain whether these inconsistencies resulted from developmental and methodological differences (i.e., the developmental period and specific forms of ASB under examination), it is difficult to make direct comparisons across these studies. Considering the empirical evidence collectively, there is some empirical support for each of the pathways stipulated in the parallel processes model, and compared to the alternative models discussed, it more completely accounts for the multiple complementary pathways to adolescent ASB that have been identified in prior investigations. However, it still remains unclear which of these alternative models is most likely to be supported in terms of early-adolescent RB.

The Impact of Chronic Peer Rejection

In regards to some of the inconsistencies about how adverse peer processes are associated with ASB, it is plausible that peer rejection’s impact on adolescent RB may be stronger and more consistent when it operates as a sustained (chronic) rather than a transient or temporally-situated risk factor. A chronic stress perspective (Lin & Ensel, 1989) suggests that longer exposures to risk factors increase resultant maladjustment. Although more widely utilized in health related research, we posit that this perspective applies to the peer context, particularly when gauging the effects of a harsh social context—that is, one marked by persistent adverse peer relational difficulties (see Ladd & Burgess, 2001; Ladd, Herald-Brown, & Reiser, 2008). As a risk factor, chronic rejection can be conceptualized as a prolonged exposure to the same processes that previously have been attributed to peer rejection. Children who are chronically rejected over multiple years are less likely to experience prosocial forms of socialization compared to children who are moderately or transiently rejected and the individual risks associated with peer rejection are more likely to be enduring and detrimental.

A small but growing body of evidence supports the premise that the effects of chronic rejection exceed those of transient rejection (Dodge et al., 2003; Ladd et al., 2008). However, these investigations have focused on the detrimental effects of peer rejection during middle and late childhood, and there remains a need for additional research which explores the potential long-term adverse effects of chronic (childhood) peer rejection on adolescent maladjustment. Considering that early adolescence is a developmental period in which children are becoming increasingly reliant on peers, children who are chronically rejected through childhood and have persistently problematic relationships with peers, may also be at greater risk for adolescent RB.

The Moderating Role of Gender in the Developmental Pathways to Rule Breaking

Extant evidence paints an unclear picture of how, and if, gender moderates the pathways to adolescent RB and the specific role of peer-relational adversities. Conceptually, it is plausible that the associations between adverse peer relations—and deviant friends in particular—and adolescent RB may be more pronounced for girls than for boys. To the extent that girls have more intimate friendships and place more emphasis on social connectedness and interrelatedness, their deviant friendships may be more influential in terms of their own ASB (see Werner & Crick, 2004). Alternatively, since children tend to affiliate more with same-sex peers and boys, on average, have higher rates of ASB than girls, boys who affiliate with more antisocial peers are at greater risk for experiencing gains in their own ASB (van Lier et al., 2005). In contrast to these arguments and findings, other investigators (Laird et al., 2001; Vitaro et al., 2007) have not found gender differences and instead have reported comparable relations between early peer relational adversities and later ASB. In light of these mixed findings, there remains a need to examine potential gender differences in these pathways and whether peer adversities have a differential role in predicting RB for boys and girls.

Aims and Hypotheses

The purpose of this research was to expand and refine knowledge about the role of childhood peer relational adversities in the developmental continuity of children’s ASB. To be specific, prospective linkages were examined among early AD in childhood, chronic peer rejection, participation in deviant friendships during early adolescence, and RB in early adolescence. Three central aims were pursued: Aim 1 was to identify trajectories of peer rejection and to assess whether a subgroup of children experienced chronic and stable forms of peer rejection across the grade school years. We hypothesized that several subgroups would be identified including a group of children who were chronically rejected across this developmental period, at least one group with more transient experiences of peer rejection (e.g., moderate-, increasing-, or decreasing-trajectories), and a group with stable low levels of peer rejection.

After identifying children’s peer rejection trajectories, the corresponding subgroups were utilized to address the study’s second aim: Aim 2 consisted of testing four alternative models (i.e., individual characteristics, additive, sequential and parallel processes models) with the primary goal of determining which of these models most adequately explained how AD and peer relational difficulties predicted RB. Although some empirical support was anticipated for each model, nested model comparisons were performed to compare models in order to determine the best fitting model which was then evaluated to draw conclusions about how adverse peer relations are associated with RB and to empirically assess the following hypotheses.

First, it was expected that children who were chronically rejected (assuming this group was identified in Aim 1) would be at greater risk for adolescent RB. This association was hypothesized to be part of a mediated process in which childhood AD would predict chronic peer rejection, which in turn would predict adolescent RB (Hypothesis 1). A second mediated effect was hypothesized in which childhood AD would be associated with having more deviant friends, which in turn would both be associated with adolescent RB (Hypothesis 2). In addition to these two mediated pathways, a sequential pathway to RB was hypothesized in which children who were rejected would have more deviant friends (i.e., childhood AD → peer rejection → deviant friends → adolescent RB; Hypothesis 3). It was also hypothesized that there would continue to be a significant direct effect from childhood AD to RB (Hypothesis 4), even after accounting for mediating peer processes.

These four hypotheses collectively reflect the multiple alternative pathways to adolescent RB. If the results conformed to these hypotheses, then greater support would be obtained for the parallel processes model as compared to the alternatives. Because this study was interested in the effects of early AD, chronic childhood peer rejection and early-adolescent deviant friendships on early-adolescent RB, it is important to recognize that these models are unidirectional in that they are assuming one temporal direction of effects and it was not possible to assess bi-directional or transactional processes among these variables. To ensure that the hypothesized predictive associations between early AD, adverse peer relations, and adolescent RB could not be explained by other confounding factors (i.e., third variable effects), a series of control variables were included in each of the four alternative models. These covariates accounted for the effects of several family risk factors identified by other investigators (e.g., Woodward & Fergusson, 1999): socioeconomic status (SES), family mobility, parental divorce, single parent household, and young maternal age. In addition to these family risks, children’s early verbal ability was also included as a covariate (Snyder et al., 2008).

Aim 3 of this study was to assess whether there were gender differences in the pathways to early adolescent RB. To achieve this aim, the final derived model (i.e., best fitting model from Aim 2) was analyzed again, this time using multiple-group analyses to compare differences between boys and girls. Considering the inconsistent gender differences reported in other studies, it was difficult to specify hypotheses about the potential moderating impact of gender. However, by using multiple-group modeling techniques, a series of nested models were compared to empirically address this aim.

Method

Participants

Data for this study came from a larger longitudinal project of children’s social, emotional and academic development. Participants were 383 children (193 girls and 190 boys) who were followed from kindergarten to grade 8 (Mage = 5.5 in fall of kindergarten and 13.9 in spring of grade 8). Families were initially recruited prior to their child’s enrollment in kindergarten classrooms in participating school districts, and 95% consented to participate. Before participant recruitment began, consent was first obtained from school administrators from multiple school districts in the Midwestern United States. School districts were selected which served students from diverse backgrounds and to proportionately represent this locales’ population in terms of geographic, racial and socioeconomic characteristics. The sample contained nearly equal proportions of families from urban, suburban, or rural Midwestern communities. The median total household income at the outset of the study was between $30,001 to $40,000 (24.5% low income, i.e., below $20,000; 38.7% middle income or higher, i.e., over $50,001). Children were primarily Caucasian (77.8%) and African American (17.8%), as well as a small percentage of Hispanic, biracial and other backgrounds (4.4%).

Procedure

This study utilized multi-informant data based on teacher-, parent-, self- and peer-reports. Teachers completed questionnaires on the participating child’s AD (in kindergarten and grade 1) and RB (in grade 8). Parents provided demographic information about their child and completed questionnaires about their child’s RB. Participants reported about their deviant friendships (in grade 7) and their own RB (in grade 8). Participants’ classmates provided peer nomination data to assess peer rejection (six waves from grades 1 thru 6). Over the course of this project, participants became increasingly dispersed across classrooms and school districts. When children changed schools, permission was sought from administrators and teachers to extend the project into their respective schools, and after these consents were obtained, the parents of project children’s classmates were contacted and asked to provide consent for their child’s participation (90% participation; number of classmates ranged from 1,834 to 3,454 across grades).

Measures

Aggression-disruptiveness (AD)

Teachers completed the entire Teacher Report Form (TRF) and the 25-item Aggressive behaviors subscale was used (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Teachers rated each item on a 3-point Likert-type scale (0 = “not true” to 2 = “very true or often true”). This measure assessed multiple forms of overtly aggressive (e.g., “Threatens people,” “Physically attacks people,” and “Gets in many fights”), disruptive/oppositional (e.g., “Argues a lot,” “Disobedient at school”, “Disturbs other pupils”) and dysregulated (e.g., “Easily jealous,” “Screams a lot,” and “Temper tantrums or hot temper”) behaviors. An AD subscale was computed by summing the ratings from the 25 items (see Table 1 for means and standard deviations). This measure was collected during three assessment periods (fall and spring of kindergarten and spring of grade 1; αs ranged from .94 to .96) and children’s AD was fairly stable across these two years (rs ranged from .61 to .79). The three AD measures were used as the indicators to estimate a latent factor which measured children’s early stable AD.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations and Bivariate Correlations for All Observed Variables in Structural Models

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Aggression (TR-KF) | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. Aggression (TR-KS) | .79** | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Aggression (TR-G1) | .61** | .63** | |||||||||||||||

| 4. Moderate rejection | .08 | .10 | .07 | ||||||||||||||

| 5. High rejection | .41** | .41** | .40** | −.27** | |||||||||||||

| 6. Rule breaking (TR-G8) | .21** | .23** | .23** | .10 | .22** | ||||||||||||

| 7. Rule breaking (PR-G8) | .28** | .28** | .20** | .06 | .24** | .55** | |||||||||||

| 8. Rule breaking (SR-G8) | .10* | .17** | .18** | −.01 | .13** | .42** | .35** | ||||||||||

| 9. Deviant friends (RB-G7) | .17** | .20** | .19** | .18** | .04 | .37** | .29** | .49** | |||||||||

| 10. Deviant friends (Sub-G7) | .05 | .10* | .08 | .10 | .04 | .33** | .23** | .46** | .76** | ||||||||

| 11. Deviant friends (Sch-G7) | .16** | .19** | .13** | .13** | .02 | .30** | .26** | .40** | .78** | .63** | |||||||

| 12. Verbal ability (KF) | −.17** | −18** | −13** | −.11* | −.11* | −.18** | −12* | −07 | −.18** | −.06 | −.15** | ||||||

| 13. Socioeconomic index | −.26** | −.27** | −.26** | −.07 | −.22** | −.22** | −.26** | −.18** | −.19** | −.15** | −.22** | .35** | |||||

| 14. Parental divorce | .04 | .00 | .01 | .15** | .02 | .03 | .04 | −.05 | .05 | .07 | .08 | −.11* | −.16** | ||||

| 15. Single parent household | .34** | .36** | .29** | .09 | .13** | .19** | .11* | .08 | .17** | .02 | .20** | −.24** | −.29** | −.15** | |||

| 16. Maternal age | .21** | .26** | .13** | .02 | .12* | .06 | .05 | .13* | .07 | −.02 | .07 | −.18** | −.17** | .00 | .29** | ||

| 17. Family mobility | .07 | .05 | .03 | .13** | .01 | .13* | .11* | .02 | .12* | .10 | .11* | −.10 | −.17** | .07 | .24** | .16** | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| M (Girls) | 3.38 | 4.13 | 3.47 | 0.29 | 0.11 | 1.47 | 1.34 | 2.68 | 1.73 | 1.62 | 1.95 | 107.44 | 57.22 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 2.53 |

| SD (Girls) | 5.37 | 6.69 | 6.68 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 2.44 | 2.04 | 2.64 | 0.75 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 16.28 | 20.65 | 0.33 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 1.71 |

| M (Boys) | 7.34 | 9.08 | 7.47 | 0.41 | 0.27 | 2.26 | 1.76 | 3.07 | 1.87 | 1.59 | 2.26 | 107.31 | 53.10 | 0.13 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 2.95 |

| SD (Boys) | 9.29 | 10.96 | 9.87 | 0.41 | 0.40 | 2.99 | 2.06 | 2.88 | 0.73 | 0.81 | 0.92 | 16.10 | 20.27 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.28 | 1.94 |

| M (Total) | 5.34 | 6.59 | 5.45 | 0.35 | 0.19 | 1.84 | 1.54 | 2.88 | 1.80 | 1.61 | 2.10 | 107.37 | 55.21 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 2.74 |

| SD (Total) | 7.83 | 9.39 | 8.64 | 0.40 | 0.35 | 2.75 | 2.05 | 2.76 | 0.74 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 16.14 | 20.54 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.27 | 1.84 |

Note. TR = teacher report; KF = kindergarten (fall semester); KS = kindergarten (spring semester); G = grade; PR = parent report; SR = self report; RB = rule breaking subscale; Sub = substance use subscale; Sch = school conduct problems subscale;

p < .05;

p < .01;

Peer rejection

Children were provided with a roster of their classmates and were asked to nominate up to three classmates that they least liked (“Kids who you don’t like to hang out with [play with] at school”). In earlier grades (i.e., grades 1 and 2) a felt board containing classmates’ pictures was used instead of a class roster, and respondents nominated classmates during individual interviews. In later grades (grades 3 to 6), children worked independently during classroom wide administrations that were facilitated by a team of trained research staff. Studies have found that peer nominations of rejection yield reliable and valid data with both younger and older children (see Cillessen & Bukowski, 2000). The total number of nominations each child received was standardized within classrooms to adjust for differences in the number of nominators. One-year stability coefficients ranged from r = .46 to r = .62.

Deviant friends

An adapted version of the Risky Behaviors of Peers (Eccles & Barber, 1990) self-report scale was used in the spring of grade 7. Children were asked to report about their friends’ behaviors using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = “none” to 5 = “almost all”). Confirmatory factor analyses supported a three factor measurement model (χ2 [86] = 251.99, p < .001, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .04, CFI = .95). The three factors (subscales) consisted of: substance use (e.g., “got drunk?” and “used inhalants, marijuana or other drugs?”; 5 items, α = .89), RB behaviors (e.g., “stole something worth more than $50?” and “suggested that you do something that was against the law?”; 7 items, α = .86), and school conduct problems (e.g., “skipped a day of school?” and “got suspended from school?”; 4 items, α = .74). Subscale mean scores were computed from the respective items and used as the indicators for a latent factor.

Rule breaking (RB) behaviors

Non-aggressive RB behaviors were assessed in grade 8 using multi-informant data collected from children, parents and teachers. Children completed the entire Youth Self Report (YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and responded to items using a 3-point Likert-type scale (0 = “not true” to 2 = “very true or often true”). A 10-item version of the Rule Breaking subscale from the YSR was used. The original subscale included 11 items; however, one item was removed (“I hang around with kids who get in trouble”) as this item was more reflective of having deviant friends than a child’s own RB. A RB subscale was computed by summing the ratings from the 10 items (α = .75). Item level analyses were performed to assess the nature and amount of RB within this normative sample. Although less serious forms of RB such as lying and cheating (30.2%) and swearing (56.5%) were more pervasive, a smaller but significant proportion of children reported more serious forms of RB such as stealing outside the home (8.9%), using alcohol or drugs (10.9%), and setting fires (11.5%). Thus, children with the highest scores on this measure engaged in multiple forms of RB that varied in severity. Rates of RB reported within this sample were comparable to those reported in other normative community samples (see Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), and the Rule Breaking subscale was used which included similar items and response options as the YSR (the same item was removed as in the YSR). The CBCL included an additional item about vandalism, not included on the YSR. A RB subscale was computed by summing the 11 items (α = .71). Teachers completed the TRF and a 7-item version of the RB subscale was used. Items and response options were comparable to the YSR/CBCL, with the exception of several items which were less relevant for teachers. A RB subscale was computed by summing the 7 items (α = .79).

The multi-informant measures of RB were moderately correlated (rs = .35 to .55) and a RB latent factor was estimated by using the self-, parent-, and teacher-reported RB subscales as the three indicators. Although it appeared that parents and teachers tended to underreport RB compared to children’s self-reports, a multi-informant measure of RB was used for several reasons. First, all three measures are well validated, reliable, and widely used in developmental research (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Second, a multi-informant measure reduced concerns about shared method variance. Third, there is evidence that aggregated multi-informant latent measures have greater predictive validity than single informant measures (van Dulmen & Egeland, 2011). Fourth, each reporter has a unique perspective and aggregating across informants may provide a more holistic assessment of children’s behaviors within the different contexts that they mostly spend their time during this age period.

Control variables

Family socioeconomic status was measured using socioeconomic index scores, a measure that is based on a family’s employment and occupational status with scores around 50 assigned to typical middle-class occupations (median = 49.14; range = 0 to 97.16; see Entwisle & Astone, 1994). Family mobility was assessed by the number of times the child had moved or changed homes. Parental divorce and living in a single parent household were assessed by computing dummy coded variables (0 = no, 1 = yes). Maternal age was also computed as a dummy coded variable which assessed the mother’s age at the time her child was born (i.e., whether the mother was 20 years old or younger; 0 = no, 1 = yes). Finally, children’s verbal ability was assessed using standardized scores from the validated and reliable Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Revised (PPVT–R; Dunn & Dunn, 1981) which was administered to each child in the fall of kindergarten.

Data Analysis Plan

Analyses were performed using Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010). First, growth mixture modeling was performed to identify subgroups of children with similar developmental trajectories of peer rejection from grades 1 to 6. Then structural equation modeling was used to examine each of the hypothesized alternative models. For each model, model fit was evaluated according to the standard established by Hu and Bentler (1999) such that models with SRMR < .08, RMSEA < .06, and CFI > .95 were considered to have adequate fit. After identifying the hypothesized model that best fit the observed data, multiple-group analyses were performed to test for gender differences.

Results

Missing Data Analyses

Given the longitudinal nature of this study, missing data increased with the passage of time and ranged from 1.2% in grade 1 to 11.9% in grade 8 (4.4% of all data were missing). Attrition was minimal throughout the study such that 4.2% of children (n = 16) had dropped out of the study by grade 7 and 2.1% (n = 8) in grade 8. In order to include the entire sample in this study and not remove any cases due to missing data or dropout, full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used. A series of univariate t-test comparisons were performed to assess some of the possible causes of missingness and to determine whether the likelihood of dropping out from the study was associated with children’s demographic characteristics (gender, race, socioeconomic status) or with AD (in kindergarten and grade 1). None of these t-tests were near statistical significance, indicating trivial differences between children who dropped out and those who remained in the study in terms of race, gender, socioeconomic status, or AD.

Peer Rejection Trajectories Across the Early Grade-School Years

Growth mixture modeling was used to identify groups of children with heterogeneous peer rejection trajectories. A series of models (i.e., 1- thru 5-classes) were specified that included intercept, slope and quadratic parameters which assessed the growth rates in peer rejection from grades 1 to 6. To evaluate models with varying numbers of classes, several criteria were considered and fit indices are reported in Table 2. Methodologists have recommended the use of a combination of multiple information criteria (e.g., AIC, BIC, and sample-size adjusted BIC referred to as SABIC), and variants of the likelihood ratio test (e.g., Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test; LMR-LRT) as a means of determining the optimal model (Ram & Grimm, 2009; Tofighi & Enders, 2008). Models with smaller AIC, BIC, and SABIC values indicate better solutions. A significant p value on the LMR-LRT indicates that a model with k classes has better fit to the observed data than a model with k – 1 classes. An additional means of assessing different models is based on classification accuracy (i.e., entropy and class assignment probabilities; values closer to 1 indicating that individuals were more precisely classified; see Ram & Grimm, 2009).

Table 2.

Model Fit Indices and Class Proportions for Peer Rejection Trajectories Models

| Model | LogL | AIC | BIC | SABIC | LMR-LRT | Entropy | Percent of children in each class (and average class assignment probabilities)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||||

| 1 Class | −2966.37 | 5940.74 | 5956.53 | 5943.84 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 Class | −2388.29 | 4794.58 | 4830.12 | 4801.56 | 1118.55** | 0.89 | 57.0(.97) | 43.0(.97) | - | - | - |

| 3 Class | −2314.50 | 4657.01 | 4712.28 | 4667.86 | 142.78* | 0.79 | 47.5(.93) | 34.2(.88) | 18.3(.92) | - | - |

| 4 Class | −2285.96 | 4609.91 | 4684.93 | 4624.64 | 55.24* | 0.79 | 16.7(.79) | 40.2(.87) | 35.8(.93) | 7.3(.89) | - |

| 5 Class | −2266.77 | 4581.54 | 4676.29 | 4600.14 | 37.13* | 0.82 | 15.9(.76) | 36.8(.86) | 4.4(.84) | 35.8(.94) | 7.1(.91) |

Note. LogL = Loglikelihood, AIC = Akaike information criteria, BIC = Bayesian information criteria, SABIC = Sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criteria; LMR-LRT = Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test.

p < .05,

p < .01

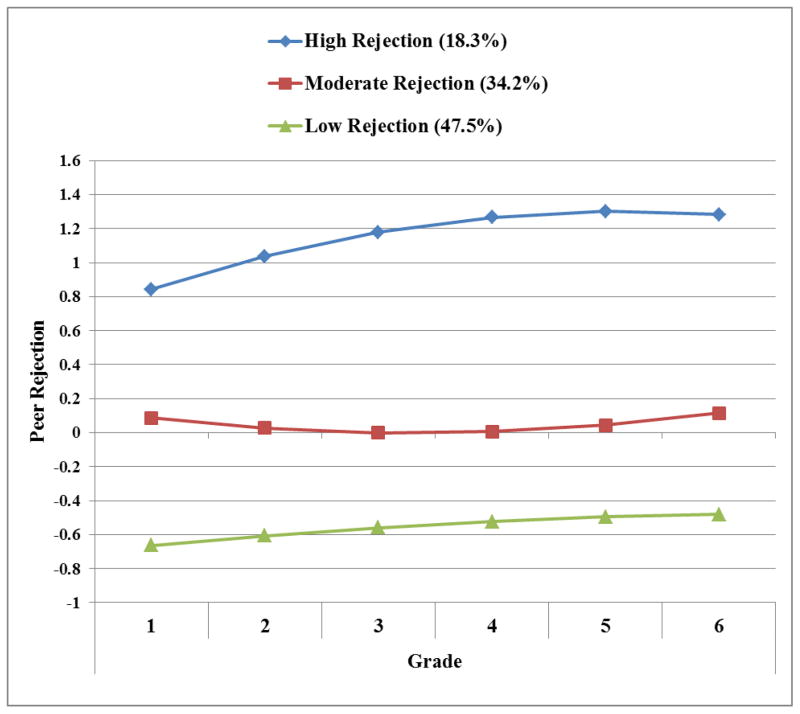

In consideration of these criteria, the 3-class model appeared to be the optimal solution (see Figure 2). Although the 4- and 5-class models had lower AIC, BIC, and SABIC values than the 3-class model, the relative improvement in these fit indices was small compared to the 1- and 2-class models. Moreover, additional classes beyond those identified in the 3-class model seemed to be substantively and qualitatively similar to other classes identified in the 3-class model. The 3-class model consisted of 18.3% of children in a high and increasing trajectory (labeled the high peer rejection group; HPR), 34.2% in a moderate and stable trajectory (moderate peer rejection group; MPR), and 47.5% had a low and stable trajectory (low peer rejection group; LPR). For interpretive purposes, it is important to note that these trajectories were estimated using standardized scores (to adjust for differences in the number of nominators per classroom). Based on this scaling, children in the HPR group were, on average, about 1 standard deviation higher in terms of the number of negative nominations they received compared to children with MPR. The MPR group tended to be about ‘average’ in comparison to their classmates in terms of the number of rejection nominations they received (i.e., their trajectory was close to zero over time), and the LPR group received few rejection nominations (i.e., −.5 to −.7 standard deviations below the mean).

Figure 2.

Estimated peer rejection trajectories from grade 1 to grade 6.

Because peer rejection scores were standardized by classroom, it was also important to further assess the validity of these trajectory groups and the extent to which children were actually rejected. Hypothetically, if children were in classrooms in which peer rejection was rare, standardizing by classroom could ‘inflate’ their peer rejection scores. To examine this possible issue, children’s trajectory class memberships from the growth mixture models were compared to the total number of rejection nominations they received from grades 1 to 6. ANOVA results indicated significant differences between the three groups (MLPR = 6.59, MMPR = 16.09, MHPR = 36.29, F = 478.41, p < .001). In terms of yearly assessments, the LPR group received on average between .72 and 1.50 rejection nominations per assessment, MPR between 2.37 and 2.92 nominations, and HPR between 5.40 and 6.71 nominations (Fs = 95.32 to 201.39, ps < .001). Thus, results based on using the raw frequencies of peer rejection nominations validate the findings of the growth mixture models and imply that children in distinct peer rejection trajectory classes experienced significantly different amounts of peer rejection.

Pathways from Early Aggressive-Disruptive Behaviors to Adolescent Rule Breaking

Alternative model comparisons

Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations) and bivariate correlations for the observed indicators included in the alternative structural models are presented in Table 1. For MPR and HPR, probability estimates (i.e., likelihood a child was classified into that particular class) were extracted from the growth mixture model and used as the indicators in the structural models. The six covariates (i.e., socioeconomic status, family mobility, parental divorce, single parent household, maternal age and child verbal ability) were used as control variables in each of the alternative models (i.e., by regressing AD, MPR, HPR, deviant friends and RB on each of the covariates).

First, the individual characteristics model was specified (χ2 [77] = 205.35, p < .001, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .07, CFI = .93) which measured the effects of childhood AD on peer rejection, deviant friends and adolescent RB (i.e., 4 paths; AD → MPR/HPR/deviant friends/RB). Second, the additive model was specified (χ2 [77] = 228.35, p < .001, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .06, CFI = .92) which measured the effects of childhood AD, peer rejection, and deviant friends on adolescent RB (i.e., 4 paths; AD/MPR/HPR/deviant friends → RB). Third, the sequential processes model was specified (χ2 [76] = 155.80, p < .001, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .05, CFI = .96) which measured the indirect effects of early AD on adolescent RB via children’s peer relational difficulties (i.e., 5 paths; AD → MPR/HPR → deviant friends → RB). Fourth, the parallel processes model was specified (χ2 [72] = 129.80, p < .001, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .04, CFI = .97) which included nine hypothesized paths (AD → MPR/HPR/Deviant Friends/RB; MPR/HPR → deviant friends/RB; Deviant Friends → RB). Model comparisons (i.e., Δχ2 tests) assessed whether there were statistically significant differences between models. Because the individual characteristics, additive, and sequential processes models were more parsimonious models that were nested within the parallel processes model, each of these models was compared to the latter. The parallel processes model had better fit than the individual characteristics (Δχ2 = 75.54, df = 5, p < .001), additive (Δχ2 = 98.55, df = 5, p < .001), and sequential processes (Δχ2 = 25.99, df = 4, p < .001) models. Thus, the parallel processes model had adequate overall model fit, and better fit than the alternative models.

Gender differences

Gender differences in the parallel processes model were assessed by examining a series of multiple-group models. First, a gender invariant model was specified in which the hypothesized path estimates and means were constrained to be equal for girls and boys. This model did not appear to have adequate model fit (χ2 [215] = 409.03, p < .001, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .09, CFI = .89. Second, a partially constrained model was specified in which the means were unconstrained, but the path estimates were constrained. This model assessed whether there were gender differences in the variable means, and the improvement in model fit indicated this was the case (χ2 [204] = 348.77, p < .001, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .07, CFI = .92; Δχ2 = 60.26, df = 11, p < .001). Third, an unconstrained model was specified in which the path estimates and variable means were unconstrained between groups (χ2 [195] = 334.12, p < .001, RMSEA = .06, SRMR = .07, CFI = .92). This model was compared with the partially constrained model to assess whether there were gender differences in the path estimates. Allowing the path estimates to be estimated freely for boys and girls did not improve model fit (Δχ2 = 14.66, df = 9, p = .10), indicating the partially constrained model was more parsimonious. Considering that the path estimates did not significantly vary across gender, follow-up analyses were performed on only the variable means to determine more specifically which variables differed by gender. These analyses indicated there were gender differences in early AD (Δχ2 = 27.47, df = 1, p < .001), MPR (Δχ2 = 14.89, df = 1, p < .001), and HPR (Δχ2 = 16.09, df = 1, p < .001), but not deviant friends (Δχ2 = .17, df = 1, p = .67) or RB (Δχ2 = .65, df = 1, p = .42). Thus, although there were gender differences in mean levels of AD and peer rejection, the strength of associations (i.e., path estimates) among variables did not differ between girls and boys.

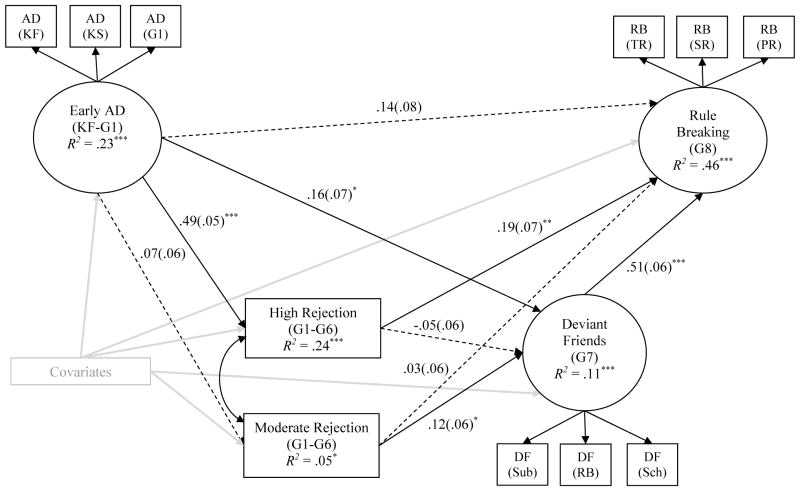

Final model

Collectively, the results indicated that the parallel processes model had better fit compared to the alternative models and gender did not moderate the hypothesized associations tested in this model. In all, the parallel processes model accounted for nearly half of the variance in early-adolescent RB (R2 = .46, p < .001) and five of the nine hypothesized effects were statistically significant (see Figure 3). To be specific, early AD significantly predicted HPR and having deviant friends, both of which in turn predicted RB and MPR significantly predicted deviant friends. Moreover, of the six covariates included in this model, four were significantly associated with at least one of the endogenous variables (note that these path estimates are not shown in Figure 3 to simplify the presentation of results). More specifically, socioeconomic status was significantly negatively associated with AD (B = −.19, p < .01), and RB (B = −.15, p < .05). Parental divorce was associated with MPR (B = .15, p < .01), and being in a single parent household and low maternal age were positively associated with early AD (B = .32, p < .001, and B = .14, p < .01, respectively).

Figure 3.

Path diagram for the final model. Standardized path coefficients (and standard errors) for each path are shown above. Path estimates for the six covariates (i.e., socioeconomic status, family mobility, parental divorce, single parent household, maternal age, and verbal ability) are represented by the gray arrows but are not shown in this figure to simplify the presentation of results. Dashed lines represent estimated paths that were non-significant at p < .05. AD = aggression-disruptiveness; KF = kindergarten (fall); KS = kindergarten (spring); G = grade; RB = rule breaking; TR = teacher report; SR = self report; PR = parent report; DF = deviant friends; Sub = substance use; Sch = school conduct problems; *p ≤ .05; **p ≤ .01; ***p ≤ .001.

Mediation tests

In addition to the direct effects between variables (shown in Figure 3), the final model was also used to test for statistical mediation (indirect) effects among multiple variables. To this end, the Model Indirect command in Mplus was used and estimates for indirect effects were computed along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI). If the 95% CI did not include zero, there was empirical support for mediation (see MacKinnon, 2008). Two of the hypothesized mediated effects from early AD to adolescent RB were statistically significant. First, the mediated effect from AD to RB via HPR was statistically significant (B = .09, 95% CI [.03, .16]). Second, the mediated effect from AD to RB via deviant friends was also statistically significant (B = .08, 95% CI [.01, .16]). However, the mediated effects from early AD to RB, via peer rejection and deviant friends (i.e., sequential processes), were not statistically significant (AD → MPR → deviant friends → RB; B = .00, 95% CI [.00, .01]; and AD → HPR → deviant friends → RB; B = −.01, 95% CI [−.04, .02]). A proportion mediated effect size measure (see MacKinnon, 2008) was computed which indicated that HPR and deviant friends accounted for approximately 57% of the total effect from AD on RB. An additional mediated effect was specified post-hoc to test whether MPR was associated with RB via its association with deviant friends, and this effect was significant (i.e., MPR → deviant friends → RB; B = .06, 95% CI [.01, .12]). Collectively, these results provided greater empirical support for parallel peer-processes, and there was partial support for a sequential peer processes pathway; however, this latter effect was not associated with early AD, as hypothesized, and only associated with MPR.

Discussion

The results of this study contribute to existing developmental research on the role of adverse peer relations in the continuity of children’s ASB. The strongest support was obtained for a parallel processes model, implying that there are multiple pathways to early-adolescent RB behaviors, and both of the peer relational processes that were examined contributed in unique ways to the continuity from childhood AD to early-adolescent RB. More specifically, early stable AD put children at risk for being chronically rejected and having deviant friends, and these relational risks independently contributed to RB. Collectively, the pathways specified in the parallel processes model explained nearly half of the variance in RB and findings were similar across gender.

Trajectories of Peer Rejection

The first aim of this study was to examine developmental trajectories of peer rejection during the grade school years. Towards this end, a latent class growth curve modeling methodology was used. Although this methodology is exploratory, researchers have recommended this approach over more traditional categorization methods (e.g., using cutoff scores) as it is better suited for handling longitudinal data and has fewer drawbacks (e.g., it does not rely on an arbitrary cutoff score and more adequately accounts for classification errors; see Giang & Graham, 2008; Ram & Grimm, 2009). Using this approach, about 18.3% of children were consistently nominated by their peers as being disliked (i.e., highly rejected; HPR) and 34.2% experienced moderate levels of peer rejection across this time period (MPR). The latter group represented children who were consistently disliked by some of their peers, but were not as pervasively disliked by peers as children in the HPR group. Because it has been rare for investigators to examine the development of peer rejection across the entire grade school period, it was not possible to directly compare these findings with other studies. Additional research is warranted to determine whether these findings would be replicated in other samples.

The findings that a subgroup of children are chronically highly rejected is consistent with existing theoretical perspectives as well as empirical evidence gleaned from examining stability coefficients of peer rejection reported in other investigations (e.g., Leflot, van Lier, Verschueren, Onghena, & Colpin, 2011; Sturaro et al., 2011). Over time, children are likely to form a reputation within their peer group that is maintained, even as they enter new grade levels (see Hymel, Wagner, & Butler, 1990), contributing to the stability of their social status and standing amongst peers. Children’s behavioral styles also reinforce their social status. Investigators who have examined transactional processes across childhood have found that children who are rejected are likely to continue to engage in aggressive behaviors which then subsequently lead to gains in peer rejection over time (Leflot et al., 2011; Sturaro et al., 2011). Given that one of our aims was to examine chronic forms of peer rejection across childhood, it was not possible to explicitly test for transactional processes between AD and peer rejection within the hypothesized models. However, transactional processes may contribute to high and persistent levels of peer rejection that are initially the result of early AD.

Whereas being highly rejected was predicted by early AD, this was not the case for MPR. This finding suggests that children with MPR are disliked by peers for reasons other than having an aggressive-disruptive behavioral style. Although the results imply that these peer rejection trajectory groups may be qualitatively distinct, there is a need for additional research to examine the differential behavioral and social antecedents of these groups. Such research may provide insights into the factors that distinguish why some children experience HPR and others MPR.

Pathways from Early Aggressive-Disruptive Behaviors to Adolescent Rule Breaking

The second aim of this study was to examine four alternative models which assessed how children’s adverse peer relations—chronic peer rejection and deviant friendships—contribute to the continuity of ASB, in which childhood AD was predictive of early-adolescent RB. Among the four alternative models that were assessed, the parallel processes model was found to be the best fitting model. The findings from the parallel processes model identified three distinct pathways to adolescent RB.

In the first pathway, children with early AD were more likely to experience persistently high levels of peer rejection (HPR) which in turn predicted adolescent RB (Hypothesis 1). This pathway was empirically supported by a statistically significant mediation effect. These results provide support for the chronic stress perspective according to which longer and more severe exposure to a risk factor increases the likelihood that it will forecast later maladjustment (Lin & Ensel, 1989). These findings are also consistent with theoretical perspectives which suggest that children’s early AD promotes an adverse social environment which then contributes to the continuity of their ASB (Patterson et al., 1989). Many aggressive children exhibit social cognitive deficits and are emotionally dysregulated, a combination of risk factors that engender hostile and coercive relationships with peers, resulting in peer rejection. In turn, the combination of having an aggressive-disruptive behavioral style and being severely rejected is particularly detrimental for children’s adjustment (Ladd, 2006). The subsequent rejection that results from these behaviors exacerbates children’s maladaptive cognitions and hinders their ability to form relationships that would foster the development of more adaptive social cognitions and prosocial behaviors which would reduce the risk for RB (Coie, 2004).

In contrast to HPR, moderate experiences of peer rejection were not strongly associated with early AD, and not directly related to adolescent RB. Compared to children who were highly rejected, those who were moderately rejected likely had fewer conflicts with children in their normative peer groups, and thus greater access to social opportunities that promote prosocial behaviors and deter RB. Indeed, the second mediated pathway from MPR → deviant friends → RB implies that moderate experiences of peer rejection are primarily detrimental for the development of adolescent RB when they result in the formation of deviant friendships. Thus, for moderately rejected children, the tendency to form deviant friendships appeared to be a more proximal determinant of their RB, whereas for chronically rejected children, it was the combination of their aggressive behavioral styles and subsequent severe rejection that led to RB.

In the third pathway, children with early AD were more likely to affiliate with deviant friends, which in turn predicted RB (Hypothesis 2). This pathway was empirically supported by a statistically significant mediation effect. This mediated pathway was consistent with prior research that has examined selection and socialization processes in relation to the development of ASB and suggests that both of these processes play a role. More specifically, the link from early AD to deviant friends is consistent with a selection perspective in that children are more likely to choose friends with similar antisocial behavioral styles. The association between having deviant friends and early-adolescent RB was consistent with a deviant socialization perspective in that having deviant friends predicted higher levels of RB that were not explained by children’s earlier AD. One implication of this pathway is that deviant friends provide a social context for children who have a tendency for ASB (i.e., early AD) to learn and model different forms of ASB (i.e., RB; Patterson et al., 1989; Patterson et al., 2000).

Contrary to expectations, and in contrast to MPR, HPR was not associated with having deviant friends (Hypothesis 3). Although the theoretical reasoning for the peer rejection-deviant peers link (i.e., the sequential processes model) appears plausible (Patterson et al., 1989), the empirical evidence has been more equivocal. Some investigators have found support for this association (e.g., Vitaro et al., 2007); however, others have not (e.g., Barnow, Lucht, & Freyberger, 2005; Laird et al., 2001; Sturaro et al., 2011). Based on the findings of this study, one explanation could be that children’s early AD is a stronger predictor of having deviant friendships than being highly rejected. Stated differently, once early AD is taken into account, the link between being highly rejected and having deviant friends is incidental. Although this interpretation is consistent with the findings of the parallel processes model and for HPR, it is insufficient when examining the findings between MPR and deviant friends. This relation, which was not preceded by early AD, implies that children who are not highly aggressive, but yet are moderately rejected by their normative peers, may seek out more antisocial peers among whom they are more readily accepted. Children who feel marginalized from their more normative peer groups and affiliate with deviant peers are less likely to experience prosocial forms of socialization that deter RB and instead affiliate with deviant peers who encourage it. Thus, the findings are consistent with the premise that, for children who are highly aggressive, it is the tendency for behavioral homophily (i.e., choosing friends based on similarities in AD), and not HPR, that drives their likelihood to form deviant friendships, and for those who are not highly aggressive, it is the experience of being moderately rejected that increases the risk for having deviant friends.

In addition to these three mediated pathways, a direct effect from AD to RB was also hypothesized (Hypothesis 4). After accounting for the mediating effects of adverse peer processes, this hypothesis was not substantiated. Although it was unexpected that the peer adversities measured in this study fully mediated the association between AD and RB, these findings attest to the pivotal role that children’s social experiences play in the development of early-adolescent RB.

The final aim of this study was to examine if gender moderated the effects of the individual path estimates and whether there are alternative pathways to RB for boys and girls. Based on the multiple-group comparisons that were made, gender differences in the paths were not statistically significant. The absence of gender differences is consistent with other studies that have examined the role of peer rejection and deviant friends on adolescent ASB (Laird et al., 2001; Vitaro et al., 2007). Although the hypothesized relations among these variables did not differ by gender, boys had higher levels of early AD, and were more likely than girls to be in the MPR and HPR groups; however, there were not significant mean differences in deviant friends or RB. These findings are consistent with the premise that boys tend to be more physically aggressive than girls, but there are smaller gender differences in non-aggressive forms of ASB such as RB that become more prevalent in adolescence (Tremblay, 2010). Taken together, these findings imply that although girls exhibit fewer childhood behavioral and relational risk factors than boys, these factors are nonetheless as problematic for their RB as they are for boys.

It is also important to note that these predictive associations were over and above the effects of (i.e., controlling for) a range of potentially confounding variables. By accounting for both child and family risk factors including low verbal ability, socioeconomic status, parental divorce, having a single parent, young maternal age, and family mobility, it was possible to more confidently rule out the notion that other ‘third’ variables were driving the associations between the hypothesized effects. Moreover, that several of the family risk factors assessed (i.e., socioeconomic status, single parent households, and young maternal age) were associated with early AD is consistent with the premise that stressful and adverse family conditions increase the risk for children’s early behavioral problems (Patterson et al., 1989).

Collectively, the findings of this study contribute to research on the developmental continuity of children’s ASB and elucidate the means by which adverse peer processes are associated with subsequent RB. In all, more than half of the total effect from AD to RB was explained by the cumulative effect of two mediating peer processes (i.e., HPR and deviant friends). Whereas these two peer processes have often been viewed as being developmentally sequential, the findings obtained for the parallel processes model indicate that these social processes have a complementary and additive effect on RB. Although the sequential processes perspective is conceptually attractive because it provides a more parsimonious explanation for how childhood AD subsequently leads to early-adolescent RB, the parallel processes model reveals a more complex explanation for how these processes unfold over time.

Limitations and Future Directions

In several ways the greater complexity of the parallel processes model is more consistent with other investigations which recognize the heterogeneity of children’s social experiences and the premise that there are multiple social processes which are co-occurring within children’s peer milieus (Snyder et al., 2008). This heterogeneity may also have implications related to how children’s peer relations could potentially influence the discontinuity of ASB. One direction for future research would be to examine other social processes, and in particular the role of prosocial and positive peer influence processes and how they may potentially buffer the long term effects of childhood AD on subsequent RB.

Moreover, the multiple pathways identified in the final model may also have implications pertaining to the heterogeneity of early AD and the differential associations it has on children’s social adjustment. There is a growing body of evidence which suggests that aggressive children are not a homogenous group and vary in their social skills, emotion regulation, and social cognitions (Vitaro & Brendgen, 2005). Although it was not possible to directly assess this heterogeneity in early AD within this study, this could serve as an important direction for future research that may provide additional insights into the multiple pathways from early AD to adolescent RB and how early AD is associated with both severe and persistent experiences of peer rejection as well as having deviant friends. Indeed, the underlying micro-social mechanisms that coincide with these two peer processes are quite distinct and it is plausible that the behavioral repertoire that aggressive children utilize impacts the peer adversities that they experience. For instance, investigators have found that some aggressive children are not rejected by peers but rather have high levels of popularity (e.g., see de Bruyn & Cillessen, 2006 for a discussion of populistic antisocial adolescents). Furthermore, whereas some aggressive children (i.e., those who are rejected) tend to be marginalized and have more peripheral roles within their peer groups, others (those who are more socially skilled or popular) tend to have more central roles (Bagwell, Coie, Terry, & Lochman, 2000). For children who act aggressively, it is plausible that their social position within their peer group and the degree to which their aggression is either positively rewarded (i.e., associated with popularity) or reprimanded (i.e., associated with peer rejection) may contribute to the diverging pathways to RB.

Further research is also needed which more specifically examines whether AD and RB have distinct etiologies. Considering the developmental timing of AD and RB, it is plausible that these factors are associated with at least partially distinct causal mechanisms that occur at different developmental stages. Whereas most forms of AD are present in early childhood, most forms of RB become more salient in late childhood and adolescence (see Burt 2012, Tremblay, 2010). Thus, in light of the findings reported in this study, it is plausible that childhood peer relational adversities have a more salient etiological role in the onset of RB than AD.

The alternative models tested in this study were intended to assess several hypothesized prospective linkages among temporally sequential variables. Although temporal precedence of variables is a requirement to demonstrate causality, these analyses were nonetheless correlational in nature, therefore causality cannot be proven. Several alternative models were tested; however, there are other potential models that could have also been examined that were beyond the scope of this study. For instance, by examining the effects of chronic peer rejection, it was not possible to examine bidirectional or transactional processes that may be occurring over shorter time intervals (see Leflot et al., 2011; Sturaro et al., 2011).

To reduce concerns that the associations among variables were the result of other potential confounding effects, several control variables were included in the analyses. Among these covariates, several family risk factors including socioeconomic status, single parent household, divorce and young maternal age were significantly associated with other variables; however, it is possible that there were other confounding effects that were not assessed. For instance, there may have been other parenting and familial processes (e.g., parental supervision and monitoring) that also contribute to RB beyond the effects of the family risk variables that were directly controlled.

Another limitation was that deviant friends were measured using self-reports. Thus, it is possible that children’s perceptions of their friends’ behaviors are not the same as their friends’ actual behaviors. By measuring RB using a multi-informant measure it was possible to reduce shared method variance between these two constructs, but nonetheless, it would have been preferable to use a multi-informant measure of deviant friends. It was also not possible to examine the effects of deviant friends during the early grade school years. Deviant peers may contribute to the development of ASB as soon as children enter formal schooling (Snyder et al., 2005; 2008) and well before early adolescence, the time period deviant friends were examined in this study. However, investigators have also suggested that deviant peers may play a more central role in the development of ASB as children get older (Sturaro et al., 2011).

Finally, it is important to note that these analyses were performed on a normative community sample with relatively low rates of AD and RB. Thus, the extent to which these results would replicate or generalize to more at-risk samples with higher rates of ASB is unclear. It is plausible that in social contexts in which aggressive behaviors are more socially acceptable, AD would be less strongly associated with peer rejection.

Conclusion

This study contributes to research on how children’s peer adversities are related to the developmental continuity in ASB. Findings imply that early behavioral risks contribute to differential social experiences and processes during childhood that place certain children at greater risk for engaging in adolescent RB. More specifically, for girls and boys, early AD predicted both HPR and having deviant friends, which in turn predicted early-adolescent RB, consistent with the parallel processes model. Moreover, once these proximal peer processes were taken into account, there was no longer a direct association between AD and RB. There was also some support for a sequential pathway in that moderately rejected children had more deviant friends in early adolescence which in turn predicted RB.

Acknowledgments

This investigation was conducted as part of the Pathways Project, a larger longitudinal investigation of children’s social/psychological/scholastic adjustment in school contexts that is supported by the National Institutes of Health (1-RO1MH-49223, 2-RO1MH-49223, R01HD-045906 to Gary W. Ladd). Special appreciation is expressed to all the children and parents who made this study possible, and to members of the Pathways Project for assistance with data collection. We acknowledge Dr. Marilyn Thompson and Dr. Natalie Wilkens for their feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms and profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington, VT: Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bagwell CL, Coie JD, Terry RA, Lochman JE. Peer clique participation in middle childhood: Associations with sociometric status and gender. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2000;46:280–305. [Google Scholar]

- Barnow S, Lucht M, Freyberger HJ. Correlates of aggressive and delinquent conduct problems in adolescence. Aggressive Behavior. 2005;31:24–39. doi: 10.1002/ab.20033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological bulletin. 1995;117:497. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA. How do we optimally conceptualize the heterogeneity within antisocial behavior? An argument for aggressive versus non-aggressive behavioral dimensions. Clinical psychology review. 2012;32:263–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cillessen AHN, Bukowski WM, editors. New Directions for Child Development, No 88. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000. Recent advances in the measurement of acceptance and rejection in the peer system. [Google Scholar]

- Coie JD. The impact of negative social experiences on the development of antisocial behavior. In: Kupersmidt JB, Dodge KA, editors. Children’s peer relations: From development to intervention. Washington, DC: APA; 2004. pp. 243–267. [Google Scholar]

- de Bruyn EH, Cillessen AHN. Popularity in early adolescence: Prosocial and antisocial subtypes. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21:607–627. doi: 10.1177/0743558406293966. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, Skinner ML. Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27:172–180. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.27.1.172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Spracklen KM, Andrews DW, Patterson GR. Deviancy training in male adolescent friendships. Behavior Therapy. 1996;27:373–390. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(96)80023-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Lansford JE, Burks VS, Bates JE, Pettit GS, Fontaine R, Price JM. Peer rejection and social information-processing factors in the development of aggressive behavior problems in children. Child Development. 2003;74:374–393. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.7402004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn LM, Dunn LM. Manual for the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test – Revised. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles J, Barber B. Unpublished measure. University of Michigan; 1990. The risky behavior scale. [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, Astone NM. Some practical guidelines for measuring youth’s race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Child Development. 1994;65:1521–1540. doi: 10.2307/1131278. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giang MT, Graham S. Using latent class analysis to identify aggressors and victims of peer harassment. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34:203–213. doi: 10.1002/ab.20233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay DF, Payne A, Chadwick A. Peer relations in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:84–108. doi: 10.1046/j.0021-9630.2003.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hymel S, Wagner E, Butler L. Reputational bias: View from the peer group. In: Asher SR, Coie JD, editors. Peer rejection in childhood. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1990. pp. 156–188. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Probing the adaptive significance of children’s behavior and relationships in the school context: A child by environment perspective. In: Kail R, editor. Advances in Child Behavior and Development. Vol. 31. New York: Wiley; 2003. pp. 43–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW. Peer rejection, aggressive or withdrawn behavior, and psychological maladjustment from ages 5 to 12: An examination of four predictive models. Child Development. 2006;77:822–846. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Burgess KB. Do relational risks and protective factors moderate the linkages between childhood aggression and early psychological and school adjustment? Child Development. 2001;72:1579–1601. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd GW, Herald-Brown SL, Reiser M. Does chronic classroom peer rejection predict the development of children’s classroom participation during the grade school years? Child Development. 2008;79:1001–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, Jordan KY, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Peer rejection in childhood, involvement with antisocial peers in early adolescence, and the development of externalizing behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:337–354. doi: 10.1017/S0954579401002085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leflot G, van Lier PAC, Verschueren K, Onghena P, Colpin H. Transactional associations among teacher support, peer social preference, and child externalizing behavior: A four-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2011;40:87–99. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.533409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin N, Ensel WM. Life stress and health: Stressors and resources. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:382–399. doi: 10.2307/2095612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Erlbaum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life course persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100:674–701. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.100.4.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Asher SR. Peer relations and later personal adjustment: Are low-accepted children “at risk”? Psychological Bulletin. 1987;102:357–389. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.102.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, DeBaryshe BD, Ramsey E. A developmental perspective on antisocial behavior. American Psychologist. 1989;44:329–335. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.2.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Dishion TJ, Yoerger K. Adolescent growth in new forms of problem behavior: Macro- and micro-peer dynamics. Prevention Science. 2000;1:3–13. doi: 10.1023/A:1010019915400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram N, Grimm KJ. Growth mixture modeling: A method for identifying differences in longitudinal change among unobserved groups. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2009;33:565–576. doi: 10.1177/0165025409343765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Schrepferman L, McEachern A, Barner S, Provines J, Johnson K. Peer deviancy training and peer coercion–rejection: Dual processes associated with early onset conduct problem. Child Development. 2008;79:252–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder J, Schrepferman LM, Oeser J, Patterson G, Stoolmiller M, Johnson K, et al. Peer deviancy training and affiliation with deviant peers in young children: Occurrence and contribution to early onset conduct problems. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:397–413. doi: 10.1017/S0954579405050194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanger C, Achenbach TA, Verhulst FC. Accelerated longitudinal comparisons of aggressive versus delinquent syndromes. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:43–58. doi: 10.1017/S0954579497001053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturaro C, van Lier PAC, Cuijpers P, Koot HM. The role of peer relationships in the development of early school-age externalizing problems. Child Development. 2011;82:758–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, Enders CK. Identifying the correct number of classes in a growth mixture models. In: Hancock GR, Samuelsen KM, editors. Advances in latent variable mixture models. Greenwich, CT: Information Age; 2008. pp. 317–341. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay RE. Developmental origins of disruptive behaviour problems: The ‘original sin’ hypothesis, epigenetics and their consequences for prevention. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:341–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02211.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dulmen MHM, Egeland B. Analyzing multiple informant data on child and adolescent behavior problems: Predictive validity and comparison of aggregation procedures. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2011;35:84–92. doi: 10.1177/0165025410392112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Lier PAC, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Koot HM, Tremblay RE. Developmental links between trajectories of physical violence, vandalism, theft and alcohol-drug use from childhood to adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:481–492. doi: 10.1007/s10802-008-9289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lier PAC, Vitaro F, Wanner B, Vuijk P, Crijnen AAM. Gender differences in the developmental links between antisocial behavior, friends’ antisocial behavior and peer rejection in childhood: results from two cultures. Child Development. 2005;76:841–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitaro F, Brendgen M. Proactive and reactive aggression: A developmental perspective. In: Tremblay RE, Hartup WW, Archer J, editors. Development of aggression. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 178–201. [Google Scholar]