Abstract

To improve the efficacy of radiotherapy (RTx), there is a growing interest in combining RTx with drugs that inhibit angiogenesis, i.e., the process of neo-vessel formation out of preexisting capillaries. A frequently used drug to inhibit angiogenesis is sunitinib (Sutent, SU11248), a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor that is currently FDA approved for the treatment of several cancer types. The current review presents an overview of the preclinical studies and clinical trials that combined sunitinib with RTx. We discuss the findings from preclinical and clinical observations with a focus on dose scheduling and commonly reported toxicities. In addition, the effects of combination therapy on tumor response and patient survival are described. Finally, the lessons learned from preclinical and clinical studies are summarized and opportunities and pitfalls for future clinical trials are presented.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10456-015-9476-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Radiotherapy, Angiogenesis, Sunitinib, Combination therapy, Cancer

Introduction

Radiotherapy (RTx) is effective against many tumor types and is used for curative and palliative purposes. Consequently, more than half of the cancer patients receive RTx [1, 2]. Despite improvements in the efficacy of this treatment modality, there are still a considerable number of patients who show tumor recurrence [1, 3]. To enhance the clinical benefit of RTx, the current research often aims to combine RTx with other treatment modalities, including angiogenesis inhibitors.

Angiogenesis is the process by which new blood vessels are formed out of preexisting vessels, and it is considered as one of the hallmarks of cancer [4]. In most tumors, an imbalance between pro- and anti-angiogenic factors exists due to tissue hypoxia. This imbalance induces the growth of an abnormally structured and leaky tumor vasculature [5]. Consequently, tissue oxygenation remains inadequate which not only causes continuous stimulation of angiogenesis but also interferes with RTx. Angiostatic drugs have been developed to counteract the imbalance between angioregulatory factors. Several of these drugs were shown to transiently induce vascular normalization in preclinical models [5]. Accordingly, the tumor perfusion briefly improved which was shown to increase the efficacy of RTx [6–8]. Whether this also occurs in human tumors is still under investigation.

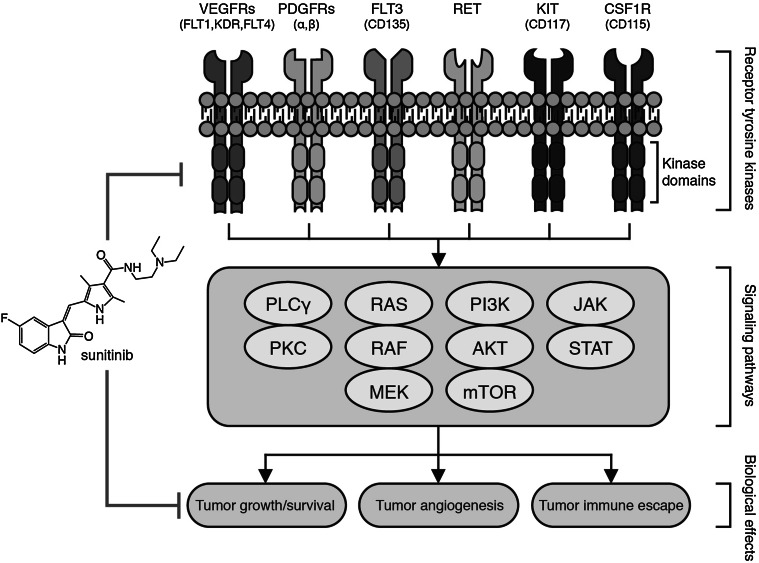

In the last two decades, combinations of RTx with different angiostatic drugs have been evaluated [6, 9–11]. One of the frequently used drugs is sunitinib (Sutent, SU11248), a receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) that targets multiple receptors, including vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR)-1, 2 and 3, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) α and β, stem cell growth factor (c-KIT), fms-like tyrosine kinase receptor 3 (FLT-3), neurotropic factor receptor (RET) and colony-stimulating factor (CSF-1R) [12, 13]. Binding these receptors results in the inhibition of multiple signaling pathways that are key in the growth and survival of different tumor cells as well as of endothelial cell, i.e., the cells that align a blood vessel (Fig. 1) (for excellent reviews, see [12, 14]). As a result, sunitinib acts as an effective inhibitor of tumor growth, as demonstrated in variety of xenograft tumor models. In patients, sunitinib is approved for the treatment of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) and imatinib-resistant gastrointestinal stromal tumors. To gain better insight into the applicability of this combination therapy, we evaluated the preclinical and clinical studies that combined sunitinib with RTx (for method of the literature searches, see supplementary data). We discuss the similarities and discrepancies between preclinical and clinical observations with a focus on dose scheduling and commonly reported toxicities. In addition, the effects on tumor response and patient survival are described. Finally, the opportunities and pitfalls for future clinical trials are presented.

Fig. 1.

Schematic overview of the main receptor tyrosine kinases, the downstream signaling pathways, and biological processes that are targeted by sunitinib

Preclinical assessment of combining RTx with sunitinib

The effects of sunitinib monotherapy on angiogenesis and tumor growth are well studied and understood [12]. The effects of sunitinib in combination with RTx are less well studied, but it has been demonstrated that sunitinib given to endothelial cells (EC) before RTx enhances the apoptotic cell fraction [15, 16]. On the other hand, El Kaffas et al. [17] did not observe an enhanced effect on apoptosis. In fact, they observed that EC apoptosis was reduced when sunitinib was combined with high-dose RTx (up to 16 Gy). These discrepancies are most likely due to differences in dose scheduling emphasizing that dosing of radiation and sunitinib are important for their effects on EC apoptosis.

In tumor cells, it is generally observed that the combination therapy enhances apoptosis and reduces clonogenic survival. For example, in 4T1 breast cancer cells, the combination resulted in an increase in caspase-mediated apoptosis, while both treatments alone had no significant effect [18]. In two pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines (MiaPaCa2 and Panc-1), sunitinib combined with RTx decreased the activation of the Akt and Erk pathway and reduced the clonogenic survival [11]. Obviously, the responsiveness to the combination therapy depends on the presence of the receptors that are inhibited by sunitinib. This was illustrated in a study using prostate cancer cell lines lacking the target receptors in which the combination of sunitinib and RTx did not alter the clonogenic survival compared to RTx alone. The presence of at least one of the target receptors already resulted in decreased clonogenic survival during combination therapy [19]. Collectively, in vitro studies show that when combined with irradiation, sunitinib can enhance apoptosis and reduce cell survival in endothelial and tumor cells. These effects only occur when the treated cells express target receptors for sunitinib and during proper dose scheduling of both treatment modalities.

An important rationale to combine sunitinib with RTx was the observation that sunitinib can transiently improve tumor perfusion by normalizing the tumor vasculature. During this so-called normalization window, tissue oxygenation is increased which improves the efficacy of RTx. For example, dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI analysis in a xenograft mouse model of kidney cancer revealed that improved tumor perfusion occurred after 3 days of sunitinib treatment. Applying RTx at day 3 while sunitinib treatment was continued for another 2 weeks appeared to further reduce tumor weights compared to either treatment alone although [20]. In a xenograft mouse model of squamous cell carcinoma, increased tumor oxygenation was observed after 4 days of sunitinib treatment. Applying RTx at day 4 resulted in a synergistically prolonged tumor growth delay as compared to sunitinib or RTx alone [21]. While these findings indicate that administration of sunitinib before RTx can improve therapeutic outcome due to vessel normalization, it has also been shown that simultaneous (concurrent) administration has beneficial effects on tumor growth inhibition. For example, in two studies using different xenograft models of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma, synergistic interactions on tumor growth delay were observed after concurrent treatment [11]. This could not be attributed to vascular normalization since a follow-up study using DCE-MRI showed that a decrease in K(trans), i.e., reduced tissue perfusion, could predict the anti-tumor effect of the combination therapy [22]. Together with observations in other xenograft models [18, 23, 24], these findings show that also concurrent sunitinib can effectively reduce tumor growth. Most likely, this is related to the increased apoptosis of EC and tumor cells as observed in the in vitro studies.

Interestingly, in a xenograft prostate cancer model, the application of sunitinib after RTx is more beneficial regarding tumor growth delay compared to concurrent sunitinib [19]. This has also been described in xenograft models of Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) [15] and colorectal carcinoma (HT29) [25]. The mechanisms behind the beneficial effect of sunitinib treatment during or after RTx are still not fully understood but appear to be distinct from vessel normalization. A possible explanation might again be the increased apoptosis as well as the induction of cell cycle arrest and senescence by sunitinib [26]. In addition, it is also known that RTx can increase the expression of vascular growth factors, such as VEGF, thereby inducing a vascular rebound effect and tumor regrowth [27–29]. Several of these growth factors activate signaling via receptors that are inhibited by sunitinib. Consequently, sunitinib given after RTx could counteract this rebound and thus prevent tumor regrowth.

Finally, an emerging concept that might contribute to the enhanced anti-tumor effect of the combination therapy involves the immune system. While describing the mechanisms and cells involved in this response is outside the scope of the current review, both sunitinib and RTx have been shown to affect many of the cellular players involved in modulation of the immune response in the tumor microenvironment [30–37]. Consequently, it is likely that the combination of both treatment modalities influences the anti-tumor immune response. However, further research is needed to elucidate their interaction, to determine the impact of different treatment schedules and to identify which immune cells are involved.

In summary, preclinical studies show the feasibility of combining sunitinib with RTx for cancer treatment. This involves different mechanisms, including vascular normalization, modulation of cell growth and apoptosis, as well as the alterations of the immune response. A major challenge will be to translate these preclinical findings into clinically relevant treatment protocols.

Lessons learned from combining radiotherapy with sunitinib in the clinic

Instigated by the promising results of preclinical research, several phase I and II clinical studies have been performed to assess the feasibility of combining sunitinib with RTx in cancer patients (Table 1). It should be noted that while the preclinical research aimed to elucidate the optimal scheduling, i.e., sunitinib either before, during, or after RTx, this has not been properly addressed in clinical trials. The latter studies focused more on feasibility and toxicity of the combination therapy, and in most studies, sunitinib was applied before and during RTx. Furthermore, in several studies, sunitinib maintenance therapy was an option for patients who well tolerated sunitinib treatment. Here, we focus on the two main schedules of sunitinib treatment in combination with RTx, i.e., a 6-week cycle (4 weeks on and 2 weeks off) and continuous administration.

Table 1.

Clinical trials that evaluated the combination of RTx with sunitinib

| Phase | Cancer type | Number of patients | Sunitinib | Radiotherapy | Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (/day) | 6-week cycle/continuously | Before/concurrent/after (B/C/A) radiotherapy | Maintenance of sunitinib | Type | Dose | ||||

| 1 | Oligometastases | 21 | 25–37.5–50 mg | 6-week cycle | B/C | Yes: 10 patients | IGRT | 40–50 Gy/10 fractions | [42] |

| 2 | Oligometastases | 25 | 37.5 mg | 6-week cycle | B/C | Yes: 9 patients | IGRT | 50 Gy/10 fractions | [43] |

| 2 | mRCC | 106a | 50 mg | 6-week cycle | C | Yes | SRS | Median 20 Gy per lesion | [46] |

| 2 | mRCC | 22 | 50 mg | 6-week cycle | C | No | Hypofractionated radiotherapy | Median 40 Gy/8 fractions | [47] |

| Case report | mRCC | 50 mg | 6-week cycle | A | Yes: dose reduction to 25 mg | Unkn | 40 Gy/15 fractions | [48] | |

| Case report | mRCC | 50 mg | 6-week cycle | B/C/A | Yes: dose reduction to 37.5 mg | Unkn | 20 Gy/10 fractions | [49] | |

| Case report | mRCC | 50 mg | 6-week cycle | A | Thoracic radiotherapy | Unkn | [50] | ||

| Case report | mRCC | 50 mg | 6-week cycle | A | WBRT | 37.5 Gy/15 fractions | [51] | ||

| Case report | m ccRCC | 50 mg | 6-week cycle | B/A | Palliative radiotherapy | Unkn | [53] | ||

| 1 | Prostate cancer | 17 | 12.5–25–37.5 mg | Continuously | B/C/A | No | External-beam IMRT | 75.6 Gy/42 fractions | [56] |

| 1 | Primary CNS/mCNS tumors | 15 | 37.5 mg | Continuously | C | Yes: 7 patients | WBRT or partial brain RT | 14–70 Gy (1.8–3.5 Gy/fraction) | [64] |

| 1/2 | STS | 32 | 50–37.5–25 mg | Continuously | B/C | No | External-beam RT | 50.4 Gy/28 fractions | [63] |

| 1 | Recurrent HGG | 11 | 37.5 mg | Continuously | C | Yes: 6 patients | Hypofractionated stereotactic RT | 30–42 Gy (2.5–3.75 Gy/fraction) | [58] |

| 2 | HCC | 23 | 25 mg | Continuously | B/C/A | Yes: 13 patients | Helical tomotherapy | Median 52.5 Gy/15 fractions | [57] |

| 2 | Non-resectable glioblastoma | 12 | 37.5 mg | Continuously | B/C | No | Partial brain RT | 60 Gy in 30 fractions | [61] |

| Case report | m ccRCC | Unkn | Unkn | B/A | Yes | SBRT | 60 Gy/5 fractions | [52] | |

m metastatic, RCC renal cell carcinoma, ccRCC clear cell renal cell carcinoma, CNS central nervous system, STS soft tissue sarcoma, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, IGRT image-guided radiation therapy, SRS stereotactic radiosurgery, WBRT whole-brain radiation therapy, IMRT intensity-modulated radiation therapy, SBRT stereotactic body radiation therapy

a45 patients sunitinib, 61 patients sorafenib

Radiotherapy in combination with 6-week cycle sunitinib treatment

The standard administration of sunitinib is in 6-week treatment cycles with 4 weeks of 50 mg/day sunitinib and 2 weeks no treatment [12, 38]. This schedule is generally well tolerated and would allow patients to recover from the potential bone marrow toxicities [12]. The most commonly reported non-hematological adverse effects are gastrointestinal toxicities, fatigue, anorexia, hypertension, skin discoloration, and the hand-foot syndrome. Hematological toxicities include neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, and leucopenia [38–41]. In general, these adverse effects are manageable and reversible.

Toxicity

The main concern when combining sunitinib with RTx in patients is the possible potentiation of the frequency and severity of side effects. To address this, Kao et al. performed a dose-escalation analysis of sunitinib both before and during RTx. At the maximum tolerated dose (MTD), i.e., 10 × 5 Gy IGRT and 37.5 mg sunitinib/day, primarily grade 3 hematological toxicities were observed which were not reported as dose-limiting toxicities (DLT). Interestingly, the patients who did experience DLT had been pretreated with chemotherapy and received RTx for their liver metastases. They therefore excluded patients with liver metastasis >6 cm for their follow-up phase II trials. Although it was stated that sunitinib did not enhanced RTx toxicities, they observed that RTx enhances the hematological grade 3/4 toxicities of sunitinib [42]. In the follow-up phase II trial, the most common grade 3 side effects were again hematological, while bleeding and liver function abnormalities occurred once. Although no grade 4 side effects were observed [43], the incidence of the side effects was higher compared to studies that evaluated RTx alone [44, 45]. Relatively mild toxicity profiles, including anemia and thrombocytopenia, were also reported in two phase II trials in patients with mRCC [46, 47]. Interestingly, the side effects were not potentiated by the combination. These differences are possibly related to the tumor type or to the different RTx doses and schedules that were applied. In addition, the duration of the sunitinib treatment, i.e., single cycle versus multiple cycles, might have been of influence. For example, in two case reports in which patients received additional cycles after RTx, the patients needed dose reduction due to intolerable side effects [48, 49].

Despite the encouraging toxicity profiles, some severe toxicities incidentally occur. Tong et al. [43] reported a grade 5 gastrointestinal hemorrhage and a fatal bronchobiliary fistula, possibly related to treatment. The latter was also described in a case report in a patient who received sunitinib after thoracic RTx for a subcarinal metastasis of renal cell carcinoma [50]. Staehler et al. reported that a patient who was still on treatment with sunitinib 3 months after stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) experienced a fatal cerebral bleeding [47]. Concerns about combining RTx with sunitinib for brain metastasis in RCC have been raised in a case report in which a patient received sunitinib after whole-brain radiotherapy [51]. Altogether, these findings show that the combination therapy is generally well tolerated, but severe complications can occur incidentally.

Clinical benefit

While the clinical benefit of the combination therapy has not been properly evaluated, the results from the phase I/II trials are encouraging. In patients with oligometastases, Kao et al. [42] reported complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) in 59 % of patients. Stable disease (SD) was reached in 28 % of the patients, while progressive disease (PD) occurred in the remaining patients. These response rates were favorable compared to systemic therapy alone [42]. This trial was followed by a phase II trial in a comparable patient group with 2-year follow-up [43]. The 18-month local control was 75 %, and distant control of 52 %. The median time until progression was 9.5 months, and at the end of the study, 18 patients were alive, 11 of whom without disease [43]. Encouraging results were also observed in patients with mRCC who received either sunitinib combined with single-fraction SRS [46] or high-dose hypofractionated RTx [47]. It was stated that these results were not explained by the single therapies alone which is supported by several case reports that described the beneficial effects of this combination therapy in patients with mRCC [48, 49, 52, 53]. Together, these findings demonstrate that the combination of sunitinib and RTx might induce clinical responses in different tumor types. However, a phase III clinical trial is required in order to draw firm conclusions.

Overall, the toxicities of the concurrent combination of RTx and sunitinib administered in 6-week cycles appears to depend on the duration and dose of sunitinib treatment, on the concurrent dose of RTx, but also on previous chemoradiation and type of metastases, e.g., liver or brain. Nevertheless, the combination therapy is generally well tolerated and appears to result in encouraging anti-tumor and clinical responses in a diverse range of tumors. All this warrants additional studies to further establish the clinical benefit of the combination therapy and to address the importance of dose scheduling on treatment efficacy and toxicity.

Radiotherapy in combination with continuous sunitinib treatment

The disadvantage of interrupting the sunitinib treatment is that it potentially allows proliferation of tumor cells between the cycles. For this reason, continuous dosing of monotherapy sunitinib has also been tested. For this, the daily dose of sunitinib was reduced to 37.5 mg/day. This regimen is also well tolerated, with a similar toxicity profile compared to the 4 weeks on and 2 weeks off schedule [12, 54, 55].

Toxicity

Similar to the studies using a 6-week cycle treatment, the trials combining continuous sunitinib with RTx have carefully evaluated the toxicity profile. In patients with localized high-risk prostate cancer, the safe dose of continuous sunitinib in combination with external-beam RTx was determined at 25 mg/day, at which one out of six patients developed a DLT (grade 3 fatigue). The most common side effects were fatigue, neutropenia, anemia, and hypertension [56]. In a phase II study including patients with locally advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), similar common and manageable side effects were reported when continuous sunitinib treatment (25 mg/day) was combined with RTx [57]. This relatively mild toxicity profile is interesting, since all patients received RTx on the liver and, as stated before, liver irradiation appeared to be an important factor decreasing the tolerability of the sunitinib dose [42]. Possibly, the lower dose of sunitinib and the different schedules underlie the differences in the side effects. However, other factors such as tumor type and dosing of RTx could also have contributed, warranting further research.

In a phase I study in patients with primary and metastatic central nervous system malignancies, the combination of concurrent sunitinib (37.5 mg/day) and cranial RTx mainly induced manageable toxicity. The incidence and severity of the toxicities were independent of type and dose of the RTx [58]. Since the toxicity rate of the combination treatment was slightly higher compared to studies in which patients only received cranial RTx, addition of sunitinib appeared to enhance the side effects [59, 60]. In a pilot study with recurrent high-grade glioma patients, 90 % experienced grade 1/2 toxicity (mainly hematological), while only one patient had a DLT (grade 4, oral ulcer) [58]. In a following phase II study with 12 newly diagnosed, non-resectable glioblastoma patients, again the most frequently reported side effects were grade 1/2, although some grade 3 toxicities were reported [61]. However, since only two patients received the combined therapy, this should be evaluated as sunitinib monotherapy. With this in mind, sunitinib treatment was stated to be well tolerated but did not result in anti-tumor responses [61]. Comparable results were found in glioma patients who received continuous sunitinib as monotherapy prior to RTx and/or chemotherapy [62].

In contrast to the mild toxicities described so far, a phase I/II study in patients with soft tissue sarcoma was closed prematurely due to DLT when sunitinib was combined with RTx [63]. Seven patients had received 50 mg daily for 2 weeks before RTx, followed by 25 mg daily during RTx. Dose-limiting toxicities were observed in four patients (grade 3/4). Subsequently, the starting dose of sunitinib was reduced to 37.5 mg daily, followed by 37.5 mg daily during RTx. The next two patients showed DLTs (grade 3), which led to premature closure of the study. Because of the lack of clinical benefit and the majority of patients showing DLTs, the schedule and dosing of sunitinib and RTx was not recommended in this patient group [63].

Altogether, continuous dosing of sunitinib combined with RTx is generally well tolerated, although due to toxicities, a lower daily dose for sunitinib is usually required as compared to the 6-week cycle. Furthermore, for specific tumor types, this combination is not recommended as it will induce DLT and does not improve patient outcome.

Clinical benefit

Similar to the 6-week cycle treatment, the phase I/II trials that combine continuous sunitinib with RTx show encouraging results. A study in prostate cancer patients with a median follow-up of 19.6 months showed a median post-treatment PSA of <0.1 ng/ml. Only two out of 17 patients showed treatment failure [56]. The suggestion of clinical benefit was also reported in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma [58] as well as in patients with primary and metastatic central nervous system malignancies [64]. In the latter study, the 6-month PFS was higher compared to studies that applied cranial RTx alone for patients with brain metastasis [65, 66]. Promising clinical responses were also observed in a study with locally advanced HCC patients [57]. Interestingly, several patients continued sunitinib treatment until disease progression. The median time to progression in these patients was 10 months compared to 4 months in those who did not receive maintenance sunitinib [57]. This observation corresponds with results described in preclinical studies, where maintenance therapy was the main factor contributing to tumor growth reduction [19, 26, 67].

While several studies indicated a potential benefit of the combination therapy, less promising responses were reported in a phase II study with glioblastoma patients in which sunitinib was started 8 weeks before RTx [61]. Only 41.7 % of patients completed the 8 weeks of sunitinib prior to RTx due to tumor progression and neurological deterioration. Furthermore, none of the patients was alive after 1 year [61]. A lack of additional clinical benefit was also observed in a phase I/II study with soft tissue sarcoma patients [63].

Together, these studies demonstrate that—similar to 6-week cycle treatment—continuous sunitinib treatment combined with RTx can induce clinical responses. Also in line with 6-week cycle treatment, the response appears to depend on the tumor type and dose scheduling. Interestingly, it is suggested that mainly the maintenance sunitinib treatment contributes to better and longer disease responses.

Future prospects: lessons to be learned

The results of the preclinical research and clinical trials have provided valuable insights into the feasibility to combine sunitinib with RTx. Furthermore, several clinical trials are ongoing (Table 2) that will further address the clinical applicability of this combination therapy. Especially with regard to dose scheduling and toxicity lessons have to be learned. Although the combination therapy appears to be well tolerated, the MTD of sunitinib depends on the scheduling that is used. Compared to the common dose for sunitinib monotherapy, i.e., 50 mg/day, the combination with RTx requires dose reductions to 37.5 mg/day in case of a 6-week cycle treatment and 25 mg/day for continuous administration [42, 43, 56, 57]. While such dose reductions generally resulted in lower toxicity rates [42, 47], there are still concerns regarding rare but severe side effects, such as perforations in the gastrointestinal tract or severe hemorrhages. Interestingly, it has been described in case reports that dose reductions do not affect tumor responses [48, 49], possibly because sunitinib is known to accumulate in the tumor [25]. This is also supported by our recent preclinical study in which sunitinib dose reductions of 50 % did not affect the tumor growth delay in combination with RTx [67]. Dose reduction of sunitinib would not only reduce the severity and frequency of side effects, but also lower the financial burden on the healthcare system [68]. Therefore, future research should further resolve whether low-dose sunitinib treatment, i.e., dosing below the MTD, would affect the response rates in patients. Measurements of tumor perfusion during treatment could be of value to get better insight into the dose–response relationship. Regarding this, an ongoing phase I study (Table 2, NCT01308034) performs DCE-ultrasonography (DCE-US) after start of sunitinib to measure neo-angiogenesis. These data can provide valuable insights into the dose-dependent intra-tumoral effects of sunitinib on perfusion and angiogenesis.

Table 2.

Ongoing clinical trials

| NCT number + status | Phase | Cancer type | Sunitinib | Radiotherapy | Neo/adjuvant (N/A) to surgery | Additional drug therapy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (/day) | Cycle/continuously | Before/concurrent/after (B/C/A) radiotherapy | Maintenance of sunitinib | Type | Dose | |||||

| NCT01498835 unknown | 1 | LA or recurrent STS | 25–37.5 mg | Continuously | B/C | No | IMRT | 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions | N | – |

| NCT01308034 recruiting | 1 | Non-resectable non-GIST sarcoma | 25–37.5–50 mg | Continuously | C | No | Unkn | Daily fractions over 6 weeks | – | – |

| NCT00437372 completed | 1b | HNC, pelvic cancer, CNS tumors, thoracic neoplasms | Unkn | Unkn | C | No | EBRT | 5 Fractions/week over max 8 weeks | – | – |

| NCT00906360 terminated | 1 | LA or recurrent HNSCC | Unkn | Continuously | C | No | 3D-CRT | Daily fractions over 7–9 weeks | – | Cetuximab |

| NCT00981890 recruiting | 1 | Brain metastases | Unkn | Continuously | B/C/A | Yes | SRS | 1 Fraction | – | – |

| NCT00463060 unknown | 1/2 | Oligometastatic disease | Unkn | Unkn | C | Unkn | Unkn | Unkn | – | – |

| NCT00631527 completed | 1 | High risk and LA Prostate cancer | ≥12.5 mg | Continuously | B/C | No | Unkn | 5 fractions/week over max 8 weeks | – | Hormone therapy |

| NCT00734851 ongoing, not recruiting | 2 | Prostate cancer | 37.5 mg | 2 weeks on, 1 week off | B | No | EBRT | 66 Gy over 6–7 weeks | – | Docetaxel prednisone |

| NCT00400114 ongoing, not recruiting | 2 | Resectable esophageal cancer | 12.5–50 mg | Unkn | A | Yes | Unkn | 50 Gy over 4–9 weeks | A | Irinotecan, cisplatin |

| NCT00570908 terminated | 2 | CNS metastases from breast cancer | 37.5 mg | Unkn | A | Yes | WBRT | 30 Gy in 10 fractions | – | Capecitabine |

| NCT01100177 completed | 2 | Newly diagnosed GBM | 37.5 mg | Continuously | B/C/A | Yes | Unkn | 60 Gy in 30 fractions | – | – |

| NCT02019576 recruiting | 2 | m ccRCC | First-line systemic dose | 6-week cycle | C | Yes | SRT | 15–60 Gy in 1–8 fractions | – | – |

GBM glioblastoma, STS soft tissue sarcoma, HNC head and neck cancer, HNSCC head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, LA locally advanced, m* metastatic, ccRCC clear cell renal cell carcinoma, CNS central nervous system, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, 3D three dimensional, CRT conformal radiation therapy, SRT stereotactic radiation therapy, EBRT external-beam radiation therapy, IGRT image-guided radiation therapy, SRS stereotactic radiosurgery, WBRT whole-brain radiation therapy, IMRT intensity-modulated radiation therapy, SBRT stereotactic body radiation therapy, Unkn unknown, – not applied

Another important lesson to be learned concerns the proper scheduling of both treatment modalities. Sunitinib treatment is often applied several weeks before RTx. This might be beneficial since sunitinib treatment has been shown to induce transient vascular normalization in preclinical models, resulting in improved tumor oxygenation [20, 21, 69]. However, evidence for such a response in patients should be addressed by future trials, for example with perfusion measurements using DCE-MRI [70–72] or by hypoxia imaging techniques such as FMISO PET [73, 74]. On the other hand, in the preclinical models, vascular normalization occurs rapidly after the start of treatment and lasts for only a few days. This suggests that even when vascular normalization occurs in the clinical setting, the window of opportunity has already passed when sunitinib treatment is given for several weeks prior to RTx. This is supported by a study of Lewin et al. [63] where DCE-MRI and FAZA-PET/CT analyses showed decreased tumor perfusion and increased tumor hypoxia after 2 weeks of sunitinib.

While the clinical benefit of sunitinib treatment prior to RTx is still unclear, there is ample preclinical evidence supporting a beneficial role of sunitinib maintenance therapy after RTx [15, 19, 57]. The mechanisms responsible for this are poorly understood but appear to be distinct from vessel normalization. Possibly, sunitinib counteracts the vascular rebound effect induced by RTx or improves the anti-tumor immune response. Unraveling these mechanisms requires further research. Furthermore, most clinical trials in which patients received maintenance sunitinib did not report on differences in tumor response rates or survival compared to patients who did not continue sunitinib treatment [42, 43, 46, 64]. This provides an opportunity for future research, and several ongoing studies have included sunitinib treatment after RTx (Table 2). These studies might give more insight into the potentially favorable effect of sunitinib maintenance therapy.

Another unexplored area in scheduling is the interaction between both treatment modalities when sunitinib has been part of a previous treatment regime. It has not been established whether RTx can be applied safely after long-term sunitinib treatment, whether sunitinib treatment has to be discontinued, or whether continuation improves tumor outcome. It has been shown in mRCC patients that discontinuation of sunitinib rapidly results in an angiogenic rebound [75]. Whether this happens in other tumor types as well and how this affects the efficacy and toxicity of subsequent RTx should be further addressed.

Of note, while the current review is focused on combining sunitinib with RTx, many of the future challenges reported here for sunitinib, also apply to other angiogenesis inhibitors. Differences in dose scheduling, type of drug, and tumor type will influence the therapeutic efficacy [76]. For example, the combination of bevacizumab (anti-VEGF antibody) and RTx can induce encouraging response rates [77, 78] or increased toxicity without any response [79, 80]. Similar divergent responses have been described for the combination of RTx with sorafenib, a TKI that targets several angiogenesis-related proteins, including VEGFR, PDGFR, and Raf kinases [81–83]. Unraveling the similarities and differences when combining angiostatic drugs with RTx requires a more systematic preclinical and clinical approach including, for example, imaging techniques to measure perfusion and early tumor responses [84].

In conclusion, the combination of sunitinib and RTx is a promising treatment strategy which deserves further preclinical and clinical investigation. Given the observed increased side effects of this combination therapy, research should focus on determining the maximum effective dose of sunitinib as well as on deciphering the optimal treatment schedules of the combination therapy. With all the lessons learned and lessons to be learned, the translation of the insights from phase I/II clinical trials into clinical phase III trials will reveal whether this combination therapy is really beneficial and could be implemented in daily clinical practice.

Electronic supplementary material

Footnotes

Esther A. Kleibeuker and Matthijs A. ten Hooven have contributed equally to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Bernier J, Hall EJ, Giaccia A. Radiation oncology: a century of achievements. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:737–747. doi: 10.1038/nrc1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delaney G, Jacob S, Featherstone C, Barton M. The role of radiotherapy in cancer treatment: estimating optimal utilization from a review of evidence-based clinical guidelines. Cancer. 2005;104:1129–1137. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Begg AC, Stewart FA, Vens C. Strategies to improve radiotherapy with targeted drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:239–253. doi: 10.1038/nrc3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jain RK. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dings RP, Loren M, Heun H, McNiel E, Griffioen AW, Mayo KH, Griffin RJ. Scheduling of radiation with angiogenesis inhibitors anginex and avastin improves therapeutic outcome via vessel normalization. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3395–3402. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Winkler F, Kozin SV, Tong RT, Chae SS, Booth MF, Garkavtsev I, Xu L, et al. Kinetics of vascular normalization by VEGFR2 blockade governs brain tumor response to radiation: role of oxygenation, angiopoietin-1, and matrix metalloproteinases. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGee MC, Hamner JB, Williams RF, Rosati SF, Sims TL, Ng CY, Gaber MW, et al. Improved intratumoral oxygenation through vascular normalization increases glioma sensitivity to ionizing radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;76:1537–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorski DH, Mauceri HJ, Salloum RM, Gately S, Hellman S, Beckett MA, Sukhatme VP, et al. Potentiation of the antitumor effect of ionizing radiation by brief concomitant exposures to angiostatin. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5686–5689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zips D, Krause M, Hessel F, Westphal J, Bruchner K, Eicheler W, Dorfler A, et al. Experimental study on different combination schedules of VEGF-receptor inhibitor PTK787/ZK222584 and fractionated irradiation. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3869–3876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuneo KC, Geng L, Fu A, Orton D, Hallahan DE, Chakravarthy AB. SU11248 (sunitinib) sensitizes pancreatic cancer to the cytotoxic effects of ionizing radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:873–879. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.02.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faivre S, Demetri G, Sargent W, Raymond E. Molecular basis for sunitinib efficacy and future clinical development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:734–745. doi: 10.1038/nrd2380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mendel DB, Laird AD, Xin X, Louie SG, Christensen JG, Li G, Schreck RE, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel tyrosine kinase inhibitor targeting vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor receptors: determination of a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:327–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aparicio-Gallego G, Blanco M, Figueroa A, Garcia-Campelo R, Valladares-Ayerbes M, Grande-Pulido E, Anton-Aparicio L. New insights into molecular mechanisms of sunitinib-associated side effects. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:2215–2223. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schueneman AJ, Himmelfarb E, Geng L, Tan J, Donnelly E, Mendel D, McMahon G, et al. SU11248 maintenance therapy prevents tumor regrowth after fractionated irradiation of murine tumor models. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4009–4016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang HP, Takayama K, Su B, Jiao XD, Li R, Wang JJ. Effect of sunitinib combined with ionizing radiation on endothelial cells. J Radiat Res. 2011;52:1–8. doi: 10.1269/jrr.10013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.El Kaffas A, Al-Mahrouki A, Tran WT, Giles A, Czarnota GJ (2013) Sunitinib effects on the radiation response of endothelial and breast tumor cells. Microvasc Res [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Zwolak P, Jasinski P, Terai K, Gallus NJ, Ericson ME, Clohisy DR, Dudek AZ. Addition of receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor to radiation increases tumour control in an orthotopic murine model of breast cancer metastasis in bone. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2506–2517. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brooks C, Sheu T, Bridges K, Mason K, Kuban D, Mathew P, Meyn R. Preclinical evaluation of sunitinib, a multi-tyrosine kinase inhibitor, as a radiosensitizer for human prostate cancer. Radiat Oncol. 2012;7:154. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-7-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hillman GG, Singh-Gupta V, Al-Bashir AK, Yunker CK, Joiner MC, Sarkar FH, Abrams J, et al. Monitoring sunitinib-induced vascular effects to optimize radiotherapy combined with soy isoflavones in murine xenograft tumor. Transl Oncol. 2011;4:110–121. doi: 10.1593/tlo.10274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsumoto S, Batra S, Saito K, Yasui H, Choudhuri R, Gadisetti C, Subramanian S et al (2011) Anti-angiogenic agent sunitinib transiently increases tumor oxygenation and suppresses cycling hypoxia. Cancer Res [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Casneuf VF, Delrue L, van Damme N, Demetter P, Robert P, Corot C, Duyck P, et al. Noninvasive monitoring of therapy-induced microvascular changes in a pancreatic cancer model using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with P846, a new low-diffusible gadolinium-based contrast agent. Radiat Res. 2011;175:10–20. doi: 10.1667/RR2068.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bozec A, Sudaka A, Toussan N, Fischel JL, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Milano G. Combination of sunitinib, cetuximab and irradiation in an orthotopic head and neck cancer model. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:1703–1707. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yoon SS, Stangenberg L, Lee YJ, Rothrock C, Dreyfuss JM, Baek KH, Waterman PR, et al. Efficacy of sunitinib and radiotherapy in genetically engineered mouse model of soft-tissue sarcoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74:1207–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Gotink KJ, Broxterman HJ, Labots M, de Haas RR, Dekker H, Honeywell RJ, Rudek MA, et al. Lysosomal sequestration of sunitinib: a novel mechanism of drug resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:7337–7346. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu Y, Xu L, Zhang J, Hu X, Liu Y, Yin H, Lv T, et al. Sunitinib induces cellular senescence via p53/Dec1 activation in renal cell carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci. 2013;104:1052–1061. doi: 10.1111/cas.12176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dalrymple SL, Becker RE, Zhou H, DeWeese TL, Isaacs JT. Tasquinimod prevents the angiogenic rebound induced by fractionated radiation resulting in an enhanced therapeutic response of prostate cancer xenografts. Prostate. 2012;72:638–648. doi: 10.1002/pros.21467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hou H, Lariviere JP, Demidenko E, Gladstone D, Swartz H, Khan N. Repeated tumor pO(2) measurements by multi-site EPR oximetry as a prognostic marker for enhanced therapeutic efficacy of fractionated radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2009;91:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2008.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park JS, Qiao L, Su ZZ, Hinman D, Willoughby K, McKinstry R, Yacoub A, et al. Ionizing radiation modulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression through multiple mitogen activated protein kinase dependent pathways. Oncogene. 2001;20:3266–3280. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bose A, Taylor JL, Alber S, Watkins SC, Garcia JA, Rini BI, Ko JS, et al. Sunitinib facilitates the activation and recruitment of therapeutic anti-tumor immunity in concert with specific vaccination. Int J Cancer. 2011;129:2158–2170. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dirkx AE, Oude Egbrink MG, Castermans K, van der Schaft DW, Thijssen VL, Dings RP, Kwee L, et al. Anti-angiogenesis therapy can overcome endothelial cell anergy and promote leukocyte-endothelium interactions and infiltration in tumors. FASEB J. 2006;20:621–630. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4493com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shrimali RK, Yu Z, Theoret MR, Chinnasamy D, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA. Antiangiogenic agents can increase lymphocyte infiltration into tumor and enhance the effectiveness of adoptive immunotherapy of cancer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:6171–6180. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huang H, Langenkamp E, Georganaki M, Loskog A, Fuchs PF, Dieterich LC, Kreuger J, et al. VEGF suppresses T-lymphocyte infiltration in the tumor microenvironment through inhibition of NF-kappaB-induced endothelial activation. FASEB J. 2015;29:227–238. doi: 10.1096/fj.14-250985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shahabi V, Postow MA, Tuck D, Wolchok JD. Immune-priming of the tumor microenvironment by radiotherapy: rationale for combination with immunotherapy to improve anticancer efficacy. Am J Clin Oncol. 2015;38:90–97. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3182868ec8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharma A, Bode B, Wenger RH, Lehmann K, Sartori AA, Moch H, Knuth A, et al. γ-Radiation promotes immunological recognition of cancer cells through increased expression of cancer-testis antigens in vitro and in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burnette BC, Liang H, Lee Y, Chlewicki L, Khodarev NN, Weichselbaum RR, Fu YX, et al. The efficacy of radiotherapy relies upon induction of type I interferon-dependent innate and adaptive immunity. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2488–2496. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dewan MZ, Galloway AE, Kawashima N, Dewyngaert JK, Babb JS, Formenti SC, Demaria S. Fractionated but not single-dose radiotherapy induces an immune-mediated abscopal effect when combined with anti-CTLA-4 antibody. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5379–5388. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Faivre S, Delbaldo C, Vera K, Robert C, Lozahic S, Lassau N, Bello C, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetic, and antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel oral multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:25–35. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, Oudard S, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:115–124. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa065044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Redman BG, Hudes GR, Wilding G, Figlin RA, Ginsberg MS, et al. Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:16–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, Blackstein ME, Shah MH, Verweij J, McArthur G, et al. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69446-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kao J, Packer S, Vu HL, Schwartz ME, Sung MW, Stock RG, Lo YC, et al. Phase 1 study of concurrent sunitinib and image-guided radiotherapy followed by maintenance sunitinib for patients with oligometastases: acute toxicity and preliminary response. Cancer. 2009;115:3571–3580. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tong CC, Ko EC, Sung MW, Cesaretti JA, Stock RG, Packer SH, Forsythe K, et al. Phase II trial of concurrent sunitinib and image-guided radiotherapy for oligometastases. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milano MT, Katz AW, Muhs AG, Philip A, Buchholz DJ, Schell MC, Okunieff P. A prospective pilot study of curative-intent stereotactic body radiation therapy in patients with 5 or fewer oligometastatic lesions. Cancer. 2008;112:650–658. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Salama JK, Chmura SJ, Mehta N, Yenice KM, Stadler WM, Vokes EE, Haraf DJ, et al. An initial report of a radiation dose-escalation trial in patients with one to five sites of metastatic disease. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5255–5259. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Staehler M, Haseke N, Nuhn P, Tullmann C, Karl A, Siebels M, Stief CG, et al. Simultaneous anti-angiogenic therapy and single-fraction radiosurgery in clinically relevant metastases from renal cell carcinoma. BJU Int. 2011;108:673–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Staehler M, Haseke N, Stadler T, Nuhn P, Roosen A, Stief CG, Wilkowski R. Feasibility and effects of high-dose hypofractionated radiation therapy and simultaneous multi-kinase inhibition with sunitinib in progressive metastatic renal cell cancer. Urol Oncol. 2012;30:290–293. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Choi YR, Han HS, Lee OJ, Lim SN, Kim MJ, Yeon MH, Jeon HJ, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma in a supraclavicular lymph node with no known primary: a case report. Cancer Res Treat. 2012;44:215–218. doi: 10.4143/crt.2012.44.3.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hird AE, Chow E, Ehrlich L, Probyn L, Sinclair E, Yip D, Ko YJ. Rapid improvement in pain and functional level in a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1156–1161. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.9846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basille D, Andrejak M, Bentayeb H, Kanaan M, Fournier C, Lecuyer E, Boutemy M, et al. Bronchial fistula associated with sunitinib in a patient previously treated with radiation therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:383–386. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kelly PJ, Weiss SE, Sher DJ, Perez-Atayde AR, Dal Cin P, Choueiri TK. Sunitinib-induced pseudoprogression after whole-brain radiotherapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:e433–e435. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Straka C, Kim DW, Timmerman RD, Pedrosa I, Jacobs C, Brugarolas J. Ablation of a site of progression with stereotactic body radiation therapy extends sunitinib treatment from 14 to 22 months. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e401–e403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.7455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Venton G, Ducournau A, Gross E, Lechevallier E, Rochwerger A, Curvale G, Zink JV, et al. Complete pathological response after sequential therapy with sunitinib and radiotherapy for metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:701–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Escudier B, Roigas J, Gillessen S, Harmenberg U, Srinivas S, Mulder SF, Fountzilas G, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib administered in a continuous once-daily dosing regimen in patients with cytokine-refractory metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4068–4075. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.5476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.George S, Blay JY, Casali PG, le Cesne A, Stephenson P, Deprimo SE, Harmon CS, et al. Clinical evaluation of continuous daily dosing of sunitinib malate in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after imatinib failure. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1959–1968. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corn PG, Song DY, Heath E, Maier J, Meyn R, Kuban D, DePetrillo TA, et al. Sunitinib plus androgen deprivation and radiation therapy for patients with localized high-risk prostate cancer: results from a multi-institutional phase 1 study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;86:540–545. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chi KH, Liao CS, Chang CC, Ko HL, Tsang YW, Yang KC, Mehta MP. Angiogenic blockade and radiotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.07.1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wuthrick EJ, Curran WJ, Jr, Camphausen K, Lin A, Glass J, Evans J, Andrews DW, et al. A pilot study of hypofractionated stereotactic radiation therapy and sunitinib in previously irradiated patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90:369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mehta MP, Rodrigus P, Terhaard CH, Rao A, Suh J, Roa W, Souhami L, et al. Survival and neurologic outcomes in a randomized trial of motexafin gadolinium and whole-brain radiation therapy in brain metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2529–2536. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Andrews DW, Scott CB, Sperduto PW, Flanders AE, Gaspar LE, Schell MC, Werner-Wasik M, et al. Whole brain radiation therapy with or without stereotactic radiosurgery boost for patients with one to three brain metastases: phase III results of the RTOG 9508 randomised trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1665–1672. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Balana C, Gil MJ, Perez P, Reynes G, Gallego O, Ribalta T, Capellades J et al (2014) Sunitinib administered prior to radiotherapy in patients with non-resectable glioblastoma: results of a phase II study. Target Oncol [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Neyns B, Sadones J, Chaskis C, Dujardin M, Everaert H, Lv S, Duerinck J, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib malate in patients with recurrent high-grade glioma. J Neurooncol. 2011;103:491–501. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0402-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lewin J, Khamly KK, Young RJ, Mitchell C, Hicks RJ, Toner GC, Ngan SY, et al. A phase Ib/II translational study of sunitinib with neoadjuvant radiotherapy in soft-tissue sarcoma. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:2254–2261. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wuthrick EJ, Kamrava M, Curran WJ, Jr, Werner-Wasik M, Camphausen KA, Hyslop T, Axelrod R, et al. A phase 1b trial of the combination of the antiangiogenic agent sunitinib and radiation therapy for patients with primary and metastatic central nervous system malignancies. Cancer. 2011;117:5548–5559. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Khuntia D, Brown P, Li J, Mehta MP. Whole-brain radiotherapy in the management of brain metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1295–1304. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.6185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gaspar L, Scott C, Rotman M, Asbell S, Phillips T, Wasserman T, McKenna WG, et al. Recursive partitioning analysis (RPA) of prognostic factors in three Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) brain metastases trials. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;37:745–751. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(96)00619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kleibeuker EA, Ten Hooven MA, Castricum KC, Honeywell R, Griffioen AW, Verheul HM, Slotman BJ et al (2015) Optimal treatment scheduling of ionizing radiation and sunitinib improves the antitumor activity and allows dose reduction. Cancer Med (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Hagiwara M, Hackshaw MD, Oster G. Economic burden of selected adverse events in patients aged ≥65 years with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Med Econ. 2013;16:1300–1306. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.838570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Czabanka M, Vinci M, Heppner F, Ullrich A, Vajkoczy P. Effects of sunitinib on tumor hemodynamics and delivery of chemotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:1293–1300. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nathan P, Zweifel M, Padhani AR, Koh DM, Ng M, Collins DJ, Harris A, et al. Phase I trial of combretastatin A4 phosphate (CA4P) in combination with bevacizumab in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3428–3439. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yopp AC, Schwartz LH, Kemeny N, Gultekin DH, Gonen M, Bamboat Z, Shia J, et al. Antiangiogenic therapy for primary liver cancer: correlation of changes in dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with tissue hypoxia markers and clinical response. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2192–2199. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1570-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Machiels JP, Henry S, Zanetta S, Kaminsky MC, Michoux N, Rommel D, Schmitz S, et al. Phase II study of sunitinib in recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: GORTEC 2006-01. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:21–28. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.8584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hugonnet F, Fournier L, Medioni J, Smadja C, Hindie E, Huchet V, Itti E, et al. Metastatic renal cell carcinoma: relationship between initial metastasis hypoxia, change after 1 month’s sunitinib, and therapeutic response: an 18F-fluoromisonidazole PET/CT study. J Nucl Med. 2011;52:1048–1055. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.084517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Murakami M, Zhao S, Zhao Y, Chowdhury NF, Yu W, Nishijima K, Takiguchi M, et al. Evaluation of changes in the tumor microenvironment after sorafenib therapy by sequential histology and 18F-fluoromisonidazole hypoxia imaging in renal cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2012;41:1593–1600. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Griffioen AW, Mans LA, de Graaf AM, Nowak-Sliwinska P, de Hoog CL, de Jong TA, Vyth-Dreese FA, et al. Rapid angiogenesis onset after discontinuation of sunitinib treatment of renal cell carcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3961–3971. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kleibeuker EA, Griffioen AW, Verheul HM, Slotman BJ, Thijssen VL. Combining angiogenesis inhibition and radiotherapy: a double-edged sword. Drug Resist Updat. 2012;15:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Blaszkowsky LS, Ryan DP, Szymonifka J, Borger DR, Zhu AX, Clark JW, Kwak EL, et al. Phase I/II study of neoadjuvant bevacizumab, erlotinib and 5-fluorouracil with concurrent external beam radiation therapy in locally advanced rectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:121–126. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kambadakone A, Yoon SS, Kim TM, Karl DL, Duda DG, DeLaney TF, Sahani DV. CT perfusion as an imaging biomarker in monitoring response to neoadjuvant bevacizumab and radiation in soft-tissue sarcomas: comparison with tumor morphology, circulating and tumor biomarkers, and gene expression. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:W11–W18. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.12412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sadahiro S, Suzuki T, Tanaka A, Okada K, Saito G, Kamijo A, Akiba T, et al. Phase II study of preoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy with S-1 plus bevacizumab for locally advanced resectable rectal adenocarcinoma. Oncology. 2015;88:49–56. doi: 10.1159/000367972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chinot OL, Wick W, Mason W, Henriksson R, Saran F, Nishikawa R, Carpentier AF, et al. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy-temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:709–722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meyer JM, Perlewitz KS, Hayden JB, Doung YC, Hung AY, Vetto JT, Pommier RF, et al. Phase I trial of preoperative chemoradiation plus sorafenib for high-risk extremity soft tissue sarcomas with dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI correlates. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:6902–6911. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hottinger AF, Aissa AB, Espeli V, Squiban D, Dunkel N, Vargas MI, Hundsberger T, et al. Phase I study of sorafenib combined with radiation therapy and temozolomide as first-line treatment of high-grade glioma. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:2655–2661. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen SW, Lin LC, Kuo YC, Liang JA, Kuo CC, Chiou JF. Phase 2 study of combined sorafenib and radiation therapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;88:1041–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jalali S, Chung C, Foltz W, Burrell K, Singh S, Hill R, Zadeh G. MRI biomarkers identify the differential response of glioblastoma multiforme to anti-angiogenic therapy. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:868–879. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.