Abstract

A rapid expansion of trade liberalization in Thailand during the 1990s raised a critical question for policy transparency from various stakeholders. Particular attention was paid to a bilateral trade negotiation between Thailand and USA concerned with the impact of the ‘Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Rights (TRIPS) plus’ provisions on access to medicines. Other trade liberalization effects on health were also concerning health actors. In response, a number of interagency committees were established to engage with trade negotiations. In this respect, Thailand is often cited as a positive example of a country that has proactively sought, and achieved, trade and health policy coherence. This article investigates this relationship in more depth and suggests lessons for wider study and application of global health diplomacy (GHD). This study involved semi-structured interviews with 20 people involved in trade-related health negotiations, together with observation of 9 meetings concerning trade-related health issues. Capacity to engage with trade negotiations appears to have been developed by health actors through several stages; starting from the Individual (I) understanding of trade effects on health, through Nodes (N) that establish the mechanisms to enhance health interests, Networks (N) to advocate for health within these negotiations, and an Enabling environment (E) to retain health officials and further strengthen their capacities to deal with trade-related health issues. This INNE model seems to have worked well in Thailand. However, other contextual factors are also significant. This article suggests that, in building capacity in GHD, it is essential to educate both health and non-health actors on global health issues and to use a combination of formal and informal mechanisms to participate in GHD. And in developing sustainable capacity in GHD, it requires long term commitment and strong leadership from both health and non-health sectors.

Keywords: Capacity, diplomacy, Thailand, trade

Introduction

‘Global health diplomacy’ (GHD) has been increasingly discussed in the global health literature by scholars in recent years (Kickbusch et al. 2007; Fidler 2009; Lee and Smith 2011). Although the definition of GHD is contested, there appears to be some consensus that GHD involves negotiation processes by which state and non-state actors interact concerning issues at the nexus of health and foreign policy; these may be in the use of health to serve foreign policy goals or foreign policy to serve health goals (Drager and Fidler 2007; Fidler 2009; Kickbusch 2011; Lee and Smith 2011; Kevany 2014). Within this broad definition, this article is primarily concerned with GHD as it applies to trade issues, although it is recognized that there are wider aspects of GHD such as those concerning security, international relations and donor prestige of global health programmes. It is also primarily concerned with how trade affects health, and less concerned with how health issues and diplomacy may impact on these other areas, such as security or investment. There is a work emerging linking foreign policy and GHD (Kevany 2014) more generally. The interesting development in this work is making explicit the diplomatic and foreign policy criteria (e.g. neutrality, visibility, sustainability, geostrategic considerations, accountability, effectiveness) for global health programmes to achieve GHD.

For a country to engage successfully in GHD, capacity is required in two areas: (1) health agencies require the resources and ability to interact with the wider diplomatic system and (2) the diplomatic organization within a country requires an understanding and willingness to reflect health concerns within their wider diplomatic remit that is often focused on trade and security. To some extent these two areas of capacity can be developed simultaneously and in a complementary manner if systems are in place to encourage dialogue between health and other agencies. Although there has been discussion of how such capacity may be developed at the supra-national level (Chan et al. 2008; Smith et al. 2009), the core of diplomatic activity remains at the national level, and thus such capacity within the nation state remains critical to GHD.

In this respect, Thailand provides an interesting case study. Literature on trade and health often cites Thailand as a leader in policy coherence between trade and health (World Health Organization and World Trade Organization 2002; Blouin 2007; Helble et al. 2008; Smith et al. 2009). This is because people tend to see the superficial, but the full picture is more rounded, nuanced and informative to developments in GHD. This study explores the relationship between trade and health spheres in more depth.

Conflicting interests between trade and health sectors first became evident here some 30 years ago, when Thailand prohibited cigarettes imported from the USA on the grounds that they contained hazardous substances that were more harmful than those substances found in Thai cigarettes. The World Trade Organization ruled in 1989 that Thailand’s action in prohibiting US cigarettes on this basis was not scientifically justified, as Thailand had failed to provide convincing scientific evidence to validate its claim (Crettol and Gavin 1990; World Health Organization and World Trade Organization 2002). This case stimulated interest in the impact that international trade negotiation, and attendant agreements, could have on health outcomes. In the 1990s, Thailand experienced an expansion of trade liberalization (e.g. Thailand–Australia Free Trade Agreement, Japan–Thailand Economic Partnership Agreement, and Thailand–United States Free Trade Agreement) which created tensions between government departments, and between government and civil society organizations (CSOs), suggesting that policy was driven by ‘vague foreign policy goals’, and was not transparent (Sally 2005). As part of this expansion, the negotiation of a bilateral trade agreement between Thailand and the USA was a major wake-up call for the health community, as the USA demanded that Thailand commits to strong intellectual-property protection (‘TRIPS-plus’) (Hunton and Williams 2003). This commitment sought to limit the government’s ability to issue compulsory licenses, one of the primary exemptions in the TRIPS agreement to improve access to medicines (IHPP and WHO 2007; Kessomboon et al. 2010). In response, the Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) established a number of inter-agency committees (with representatives from government and non-governmental agencies) in 1998 to develop an understanding of health-related trade issues and engage with the trade negotiation processes to address health concerns (Pachanee and Wibulpolprasert 2004; Ministry of Public Health 2008a).

There have been several further related activities. The MOPH built a network, together with universities, the Ministry of Commerce and funding bodies, to develop ‘a research framework on trade in health services’ in 2003 (Pachanee and Wibulpolprasert 2004). By 2007, the new national constitution for Thailand stipulated that the government was to provide trade information to the public, have public consultations and parliamentary approval before engaging in trade negotiations with other countries (Royal Thai Government 2007). The Ministry of Commerce was made responsible for national trade policy development and mandated to have stakeholder consultations before participating in trade negotiation processes. As a consequence of these developments, the preparation processes for trade negotiations involved a wider degree of concerned agencies, including those representing health interests. The prior movements by the MOPH had allowed the development of significant capacity in the health sector and among CSOs to be able to participate actively in consultations from a health perspective (Pachanee and Wibulpolprasert 2004). The National Health Assembly (NHA), established in 2008, for example, has become a specific forum to bring actors together to discuss health issues arising from wider policies, including those related to trade, and at the global level, Thai representatives have been successful in tabling a resolution on ‘International trade and health’ at the World Health Assembly in 2006 (Tangcharoensathien 2010).

With the increased emphasis on trade negotiations by those within the broader health field, the experience of health engagement by Thailand with other interested parties before, during and after specific diplomatic activities related to trade negotiations, holds potential lessons for wider engagement at the national level, and in developing capacity more broadly in GHD.

Methodology

This article utilizes three information sources: a review of key literature, interviews with key stakeholders and non-participant observation during related international meetings on trade-related health negotiations.

With respect to interviews with key stakeholders, 20 interviews with those who engaged in the process of trade-related health negotiations were conducted in Thailand during November 2010–February 2011. Due to the sensitive nature of the issue, many respondents asked not to be identified in this article. Respondents were from state, non-state and intergovernmental organizations; seven from MOPH, one from Health Systems Research Institute (HSRI), three from Ministry of Commerce, two from Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), one from Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board, one from a private hospital, one from business, one from an academic institution, one from a non-governmental organization (NGO) and two from international governmental organizations. This sample was determined by their roles within the process of trade-related health negotiations. Once interviews were underway, respondents were asked for suggestions of further people to interview. Towards the end of the interview process, it was felt that new issues were not being raised, leading the authors to some confidence that key issues have been uncovered.

The interviews were semi-structured, with questions following organically according to responses being made and information being shared, but were set to cover several broad topic areas: actors in trade negotiations, health actors engagement trade negotiations, networking among the actors and evaluation of health engagement in trade negotiations. Most interviews were conducted in the Thai language and were recorded with respondents’ permission. All recordings were transcribed and translated by the first author.

The final source of information was from the observed discussions of health-related trade issues at the meetings held during November 2010–February 2011. The first author observed nine meetings as an observer without engaging with the meeting; the 63rd meeting of the Committee on Coordinating Services (CCS), 25th Meeting of the Healthcare Services Sectoral Working Group (HSSWG), Public Consultation on 8th Package of (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services (AFAS), 3rd National Health Assembly, Stakeholder consultation on 8th Package of AFAS, 3rd Meeting of National Commission on International Trade and Health Study, Meeting of the Committee on Global Health and International Trade, 64th Meeting of the CCS and 26th Meeting of the HSSWG.

Information from above sources was analysed using the ‘Framework Approach’ developed by Ritchie and Spencer (1994), through five steps: familiarization of data, identifying a thematic framework based on study objectives, indexing the data, charting the data and mapping and interpretation of the findings (Ritchie and Spencer 1994). The analysis from each source was then triangulated to generate a holistic picture concerning the development of capacity for GHD within Thailand, and in particular: (1) the key actors involved in capacity building; (2) the model used by Thailand for capacity development and (3) key aspects related to the process of capacity development.

Thailand’s key actors in health and trade

There are a number of institutional actors in Thailand that have a potential stake in issues relating to health and trade. These actors can be divided into two groups: health actors and trade actors, both align with two subgroups: state and non-state (Box 1).

Box 1 Actor in trade-related health negotiations.

| Actors | Agencies | Responsibilities | Concerns about |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health | |||

| State | |||

| MOPH | Health promotion, disease control and prevention, treatment, and health rehabilitation | Access to medicines, brain drain of medical doctors | |

| HSRI | Health systems research management | Brain drain of medical doctors | |

| NHCO | Healthy public policy development | Population’s wellbeing | |

| ThaiHealth | Health promotion with focusing on a reduction of health risk factors | Prevalence of tobacco and alcohol consumption | |

| NHSO | Manage a national health insurance scheme | Access to quality health services | |

| Health professional councils | Regulate and control the practice of health practitioners | Migration of health professionals | |

| Non-state | |||

| PHA | Protect and enhance mutual benefits of private hospitals | Market access/business opportunity | |

| CSOs | Advocate for vulnerable groups | Access to medicines and brain drain of medical doctors | |

| Trade | |||

| State | |||

| CIERP | International economic relations policy | Trade competition and economic growth | |

| DTN | Formulate trade policy and establish the framework for trade negotiations | Trade competition and economic growth | |

| MFA | Promote interaction with the global community | Strengthen trade diplomacy | |

| NESAC | Advise the Prime Minister and cabinet on social and economic issues | Impact on social and economic problems | |

| Non-state | |||

| JSCCIB | Advocate for business opportunity | Business opportunity | |

KEY MESSAGES.

Trade liberalization, especially its effects on price and access to medicines, has been at the core of GHD.

Thailand is often cited as a positive example of a country that has achieved considerable trade and health policy coherence through, and as part of, GHD.

Core lessons are for health actors to build their capacity over time, starting from the individual (I) to understand trade effects on health, the node (N) to establish the mechanisms to enhance health interests, the network (N) to advocate for health, and the enabling environment (E) to retain health officials and strengthen their capacities.

This INNE model seems to have worked well in Thailand.

State health actors

The MOPH is the core national health agency responsible for disease prevention, health promotion and health protection. Other key health-related players include: the HSRI, an autonomous state agency, which aims to achieve ‘better knowledge management for better health systems’1; and the National Health Commission Office (NHCO), an autonomous health agency mandated to support public participation in building healthy public policies and to organize the NHA; the health professional councils (e.g. Thai Medical Council, Dental Practitioner Council and Nursing Council) who work under MOPH supervision and have a role in regulating and controlling health practitioners and their practices; the Thai Health Promotion Foundation (ThaiHealth), an autonomous organization responsible for promoting public health with focusing on a reduction of health risk factors2; the National Health Security Office (NHSO), a semi-autonomous body established in 2002 to manage a national health insurance scheme.

Non-state health actors

The CSOs, particularly the National Health Foundation (NHF), Health Promotion Institute, the Human Right Commission, FTA watch, Drug Study Group, HIV/AID Patients’ Network, AIDS Access and Foundation for Consumers (FFC), are the key players in trade policymaking process. The Private Hospital Association (PHA), established to protect and enhance the mutual benefits of private hospitals, is also actively involved in such process.

State trade actors

Of the state trade actors, the most critical are: the Committee on International Economic Relations Policy (CIERP), composed of policy elites3 from economic ministries who play a crucial role in directing trade liberalization policy, and appoint negotiator teams for all trade negotiations; the National Economic and Social Advisory Council (NESAC), a public agency that plays an advisory role to the cabinet regarding social and economic issues; the Department of Trade Negotiations (DTN) under the Ministry of Commerce (MOC), who have a role in drafting the frameworks for all trade negotiations and, since 2007, mandated to hold consultations with all concerned stakeholders to develop the framework for negotiations and propose it to the Parliament for approval (Talerngsri and Vonkhorporn 2005); the MFA, which was tasked with leading bilateral trade negotiations with the United States4 and Japan5, and plays a facilitating role to oversee whether agreements require parliamentary approval6; the parliament, which plays a role in reviewing the framework of trade negotiations and approves it before and after negotiations with trading partners.

Non-state trade actors

The Joint Standing Committee on Commerce, Industry, and Banking (JSCCIB), composed of the Thai Chamber of Commerce (TCC), Federation of Thai Industries (FTI) and Thai Banker’s Association (TBA), has been frequently consulted by the government during the process of trade liberalization policy formulation and trade negotiations (Pibulsonggram 2004; Peamsilpakulchorn 2006).

The dominant actors are the CIERP and DTN from the trade side, and MOPH from the health side (Pachanee and Wibulpolprasert 2004; Talerngsri and Vonkhorporn 2005). The ultimate responsibility lies with the MOC who will sign trade agreements, but other agencies have considerable influence in determining the outcome of negotiations. For example, if the USA wanted Thailand to agree with ‘data exclusivity’ and ‘patent checking’ before drug registration, these are within the ‘state power’ remit of the MOPH. In this respect, one may broadly categorize trade organizations as concerned with advancing the trade liberalization policies of Thailand, and the MOPH representing the major concerns of the health community of the potential negative impact of trade liberalization. A senior advisor to the MOPH stated that ‘MOPH was interested in trade liberalization policy since the Uruguay round as they were convinced that TRIPS would affect access to affordable medicines. We acted seriously against the amendment of the patent act from the late 1980s to early 1990s. We (MOPH) sent our staff to join the Doha negotiation on TRIPS. We did not want to open our health market through any trade agreements …’7 An anonymous MFA official stated that: ‘the MOPH may be concerned with the brain drain from trade liberalization …’8 ‘the ministry was concerned with the negative impact of trade liberalization on the health system, thus engaging in the process of trade negotiations to minimize that impact …’9 The ministry thus works with other actors like academia, CSOs and NHCO to advance health interests, and is generally perceived to be an active actor, having a good understanding of the health impact of trade. 10

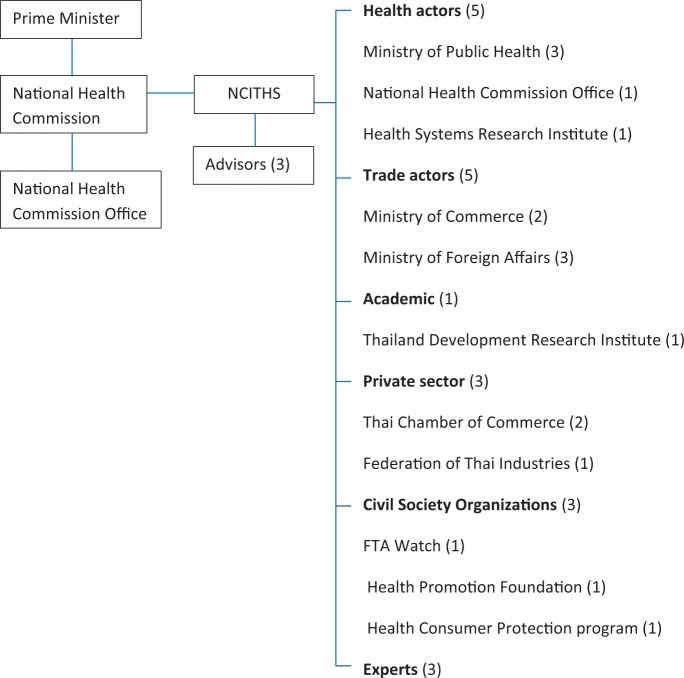

The NHCO has become involved in the process of trade negotiations since the NHA resolution on ‘Public participation in free trade negotiation processes’ came into existence in 2008. It also takes a secretarial role for the new interagency committee established by the National Health Commission (NHC), chaired by the Prime Minister; ‘the National Commission on International Trade and Health Study’ (NCITHS). This commission is a ‘strong commission’, in the sense that it is appointed by the Prime Minister. Nevertheless, consensus building by the commission on trade in alcohol and tobacco products for instance remains to be achieved (National Commission on International Trade and Health Study 2010a,b; 2011): ‘the commission members (especially representatives from private sector and civil society) have different perspectives on trade in harmful products… it is very challenging for the commission to achieve consensus on these issues’.11 Other health actors, such as HSRI and ThaiHealth, have neither power nor legitimacy to take part in the process of trade negotiations, but create a coalition of interested parties and work closely with MOPH and NHCO.

Actors engaged with the process of trade negotiations clearly do not do so on an equal basis. The level of their engagement and influence in such a process depends especially on three factors: (1) power to influence decision making; (2) legitimacy to be involved and (3) urgency in resolving the issue. These factors are often used to differentiate actors and to assess the level of their influence in the decision-making processes (Mitchell et al. 1997). The MOC, possessing all of these factors, would be considered to be the most powerful actor in any trade-related health policy development process.

The INNE model for capacity building

Trade issues initiated action by the MOPH to develop capacity for engaging with trade negotiations where there were felt to be significant health issues. This development of capacity was based on the United Nations Development Programme INNE Model (UNDP 1997). This model covers four aspects of capacity building: Individual, Node, Network and Enabling environment.

Individual capacity (I)

The MOPH initially established the ‘International Health (IH) Scholar Program’ in 1998 to build up individual capacity on global health issues. Scholars were recruited from ministries, universities and NGOs. They undertake on-the-job training, under close mentorship and work on global and regional health issues. They prepare a national position on their assigned agendas in consultation with concerned domestic stakeholders and senior mentors, and participate in meetings concerning these issues in a variety of fora, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. In the last five World Health Assemblies, the Thai delegation (more than 50 each year) out numbered far bigger countries such as the USA and Japan, and Thailand used the forum of the WHO Executive Board and the WHA especially for ‘real-world’ capacity development in GHD. Scholars are encouraged to build coalitions with ‘like-minded’ countries who have similar interests on particular global health agendas and pursue similar goals. Debriefings after the meetings include discussion of the downstream process and steps in implementing the decision or resolutions. These activities provide the scholars opportunity to enhance their technical, negotiation and communication skills and, critically, ‘allows scholars to build up their courage to speak up and negotiate at the international meetings’.12

Node (N) or organization

The MOPH then established the semi-autonomous International Health Policy Program (IHPP) in 2000 to be a hub for capacity building on global health issues and GHD, with a mission to ‘conduct policy relevant research and get research into policy and practice’.13 IHPP fellows are trained through apprenticeships with senior researchers prior to formal academic (Masters/PhD) training. A number of nodes or key organizations were also established to accommodate the trained researchers. A recent node is the International Trade and Health Programme established in mid-2010 as a collaborative programme between MOPH, WHO, HSRI, NHSO, NHCO and ThaiHealth, whose goal is to ‘build up and strengthen individuals and institutional capacities in order to generate evidence-based policy decisions and coherence policies between international trade and health for the positive health outcomes of the population’ (IHPP 2010). This programme has become the technical secretariat of the NCITHS (National Commission on International Trade and Health Study 2010,b). ‘The Programme generates evidence (of trade effects on health) to support NCITHS’s making decisions and also for health negotiators to use in trade negotiations’.14

Network (N)

The IHPP and MOPH have collaborations with both domestic and external institutions to exchange and share knowledge. The ‘research framework on trade in health services’ introduced in 2003 was a collaboration of MOPH, academics, research funding bodies and the private sector (Pachanee and Wibulpolprasert 2004). The Thailand Research Fund (TRF) also granted financial support to the ‘WTO Watch’ project15 to develop knowledge on WTO and its rules in order to provide concrete information for establishing the national position at the Doha Development Round of negotiations. The FTA Digest website16 was further supported by the TRF to educate the public on the implication of WTO agreements and report the progress of international trade negotiations. More broadly, Thailand was instrumental in the establishment of ‘GHD.Net’, an international network concerned with the application of GHD (GHD-NET 2009).

There is also an informal network of collaborations among health policy makers, health researchers, trade officers, trade negotiators, foreign policy officers, academic institutions, trade policy funding agencies, private sector and CSOs. The importance of the informal network is discussed in more detail later.

Enabling environment (E)

The enabling environment covers institutional, sociopolitical, economic, and environmental contexts; many of which are beyond the MOPH’s official remit. However, the Ministry has an official mandate to provide financial and non-financial incentives, establish organizations to accommodate health experts, and establish the Prince Mahidol Award Conference (Ministry of Public Health 2010) as a venue for domestic scholars to engage in a global health policy and build a network with international health experts.17 ‘This forum allows us (MOPH) to bring our scholars and partners to link more with the world.’18 It is also the case that often issues generate public support (e.g. access to medicines) and public media attention, which may be useful in domestic support for the approach taken to an issue in broader GHD.

Establishing the process of health engagement in wider diplomacy

To complement capacity building of individual health officials and organizations, a variety of other mechanisms are used by MOPH to get health concerns on the trade negotiation agenda: institutional mechanisms, interagency committees and working groups, the NHC and NHA and informal processes.

Institutional mechanisms

The administrative structure of ministries in Thailand is founded on hierarchy and authority, with co-ordination among ministries undertaken through institutional arrangements. This leads to the common problem of co-ordination and engagement.

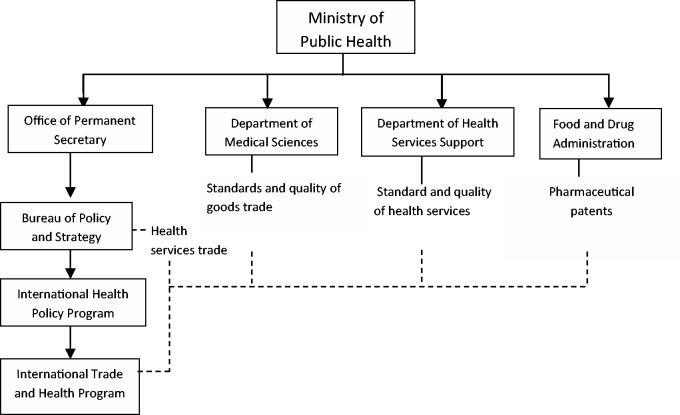

For instance, the Food and Drug Administration is concerned with trade-related food or drug issues, the Department of Health Service Support (DHSS) trade in health-related services, Department of Medical Sciences (DMSc) Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT)/Sanitary and Phytosanitary measures (SPS), Department of Disease Control (DDC) and Bureau of Policy and Strategy (BPS) for trade-related health services under the AFAS (Figure 1). As the health inspector general of the MOPH states, ‘In my perspective, the bureaucratic system has long, cumbersome procedures which are not suitable for the present working environment’.19

Figure 1.

Structure of MOPH agencies responsible for trade and health issues

The structure of the MOPH agencies, outlined in Figure 1, contributes to a lack of oversight and coherence between those concerned with trade issues affecting health. The MOPH does not have a single office to cover all health related trade issues, but tasks a particular health-related issue office to a respective office (Figure 1) that shares a rather defensive view of trade. This prevents the ministry to get the ‘best deal’ from trade in both a defensive and offensive manner as required. For example, there is a limited potential to join up and/or trade-off policies between areas, such as may be required in the case of medical tourism and health worker migration, where there are debates about the extent to which increased foreign patients stimulates the rural-to-urban health worker migration, or conversely could be a strategy to reduce international migration of Thai health workers.

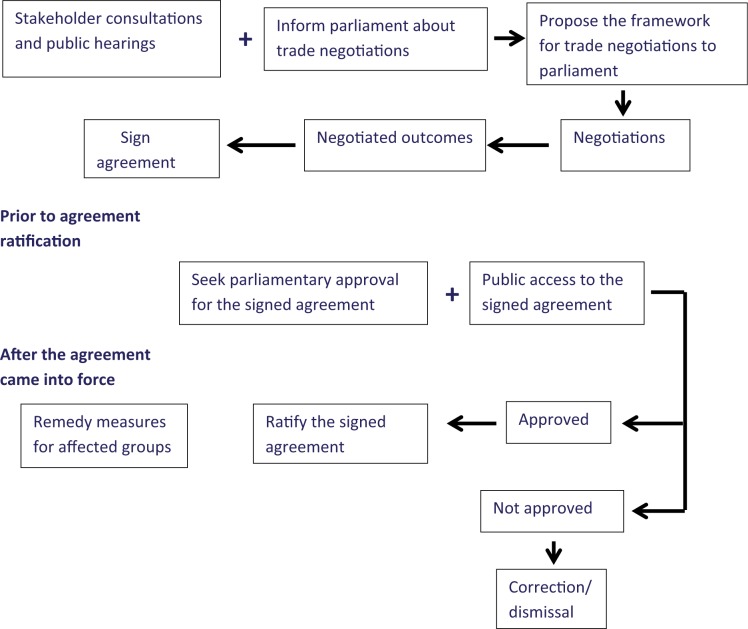

In this respect, an important feature of the Thai system for GHD is Article 190 of the 2007 Constitution, which mandates the DTN to make the process of trade negotiations transparent to the public (Royal Thai Government 2007). Prior to trade negotiations with other countries, DTN is required to consult concerned stakeholders, organize public hearings and submit the framework for negotiations to parliament for approval. After negotiations conclude, the signed agreements are open for public access before being submitted to parliament for approval (Figure 2) (Vonkhorporn 2010). Concerned stakeholders are thus able to voice their concerns through both public consultations and public hearings. This unusually open process for policymaking has enabled the MOPH, and others, to engage with MOC through these consultations.

Figure 2.

Preparatory process for trade negotiations in Thailand. Source: Vonkhorporn (2010)

Interagency co-operation

Partly in response to the ‘bureaucratic system’, in 1998 the MOPH established a number of inter-agency committees, especially the ‘Ministerial Committee on Health Impact from International Trade’, with their subcommittees for TRIPS, SPS, TBT and General Agreement on Trade in Services, to discuss and manage health issues arising from trade negotiations and to co-ordinate with the Ministry of Commerce and Ministry of Industry.

For example, during 2004–2006, the MOPH engaged in the negotiation processes under the Thai–US FTA. A working group to study the impact of the TRIPS-Plus provision found that it would have a significant impact on the cost of medicines and delay generic drug accessibility. Their findings were presented to MOC senior officials for inclusion in the framework for negotiations (IHPP 2007). This strong evidence-based movement delayed the conclusion of the negotiation (which was eventually suspended in 2006 due to the coup détat) (Ahearn and Morrison 2006).

As another example, in 2009 the NHC, chaired by the Prime Minister, appointed the National Commission on International Trade and Health Study, composed of key stakeholders (Figure 3). Its main responsibility is to offer policy recommendations on health-related trade issues to the Prime Minister (National Health Commission 2009). It is noteworthy that this committee is chaired by a senior member of the Thai Chamber of Commerce, who is also the Vice President of the NHA.

Figure 3.

Composition of the national commission on trade and health appointed by the Prime Minister. Source: National Health Commission (2009)

Of course, the development of these interagency committees and working groups is ad hoc, and it is not clear how productive (or generalizable) it was (Pachanee and Wibulpolprasert 2004). Although stakeholders are represented, often appointed members send junior staff, and one senior advisor to MOPH felt that ‘The committees could not be regarded as productive’.20 An academic also felt that the interagency committees did not offer a strong health position for negotiators.21 These committees also face challenges in how to ensure their recommendations reach policy makers.22 Nonetheless, this approach can be valuable in increasing understanding and awareness of trade and health among agencies, and create friendships among officers (see section later on Informal mechanisms).

NHC and NHA

The annual NHA convened by the NHC under the 2007 National Health Act allows stakeholders to participate in discussions on the development of national health policy. Topics are proposed by stakeholders, based on its urgency and health impact (National Health Commission Office 2008). Trade and health issues have received high attention since the first NHA in 2008. The resolution resulting from this meeting—‘Public participation in free trade negotiation processes’—was endorsed and came into force in 2009. At the third NHA in 2010, the agenda included ‘Prevention of the negative impact of trade liberalization on health and society’ (National Health Commission Office 2010).

The NHA is a promising forum for stakeholders, particularly civil society, to discuss issues and find resolutions (National Health Commission Office 2008). A senior MOPH official stated that ‘the NHA is one of the mechanisms that can solve the complex (health) issues that require multi-sectoral collaboration’.23 However, NHAs have become dominated by representatives from CSOs, with most public agencies not vocal.24 ‘The assembly should take a soft approach, different viewpoints should also be acknowledged; otherwise, those whose voices are not heard would hesitate to join the next NHA.’25 A similar concern was also expressed by the Director of Bureau of Multilateral Trade Negotiations, who urged health actors to approach DTN softly with strong evidence and a clear health policy.26

Nevertheless, NHA resolutions are endorsed by the cabinet and Prime Minister and have come into force for relevant authorities. For example, the resolution concerning the ‘Medical Hub Policy’, e.g. impacts on investment, as the Board of Investment is required not to grant tax exemption for those investing in health services for commercial purpose (Sarnsamak 2011).

Informal mechanisms

A more informal mechanism of health engagement with trade exists in personal relationships and networks. The former MOPH Permanent Secretary and Public Health Minister emphasized that ‘in Thai culture, personal relationships are very important … if we depend only on the formal co-ordinating mechanism among the ministries we cannot work fast or that efficiently … we need to build the networks with both international and local partners who have mutual interests with us … we also need to build a coalition with CSOs to help us move on the complex issues …’27

The MOPH started to support CSOs for health development in 1990 (Ministry of Public Health 2008a). ‘We granted financial support to CSOs as well as educated them so that they can help us mobilize public movement outside (the ministry) … we have a network with them but not that strong, having some conflict sometimes, but not much … we foster trust with each other…’28 For example, the MOPH supported the role of NGOs at the Conference of the Party (COP) of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which is the governing body of the FCTC composed of 177 parties.29 During the second session of the Conference (COP 2) held in Bangkok in 2007, MOPH representatives lobbied other parties to vote for a Thai health NGO (Health Promotion Institute) to chair the Bureau and to be President of the third session of the Conference (COP 3) held in South Africa in 2008. At the same meeting, another tobacco expert from ASH (Action on Tobacco and Health) was appointed as the chief Thai delegate. It is not unusual that the government appoints NGOs to represent the country at a global health negotiating body.30 In the Thai delegations to the WHA, for example, there are also leaders from NGOs, private sector and even mass media. Indeed, some senior MOPH staff are also members or leaders of NGOs themselves.

Such activities are also the case at the international level. The WHA resolutions31 related to trade issues, for example, were tabled and chaired by Thailand. A senior advisor to MOPH stated that ‘we need to move at the global health forum such as the WHA to have resolutions on pressing issues so that we can use them as references for health movements at a domestic level’.32 One good example is to successfully push for an operative paragraph in a WHA resolution to request the Director General of the World Health Organization to support member states in implementing TRIPS flexibilities to achieve better access to essential medicines. This allowed WHO/Headquarters to form an expert team to assess the Thai compulsory license system and provide excellent technical advice as well as social support, and a joint publication by WHO, UNAIDS and United Nations Development Program (UNDP) to support developing countries to implement TRIPS flexibilities (UNAIDS 2011).

These informal mechanisms are also important to bring health concerns onto the agenda of trade negotiations. The Director of the Bureau of Multilateral Trade Negotiations suggested that the ‘MOPH needs to make friends with the secretariat of the negotiator team’.33 In addition, building informal relationships at two levels—working and institutional relationships—is essential,34 as is building capacity for non-health actors if they are to advocate for better health: ‘there is a need to build capacity for both health actors and trade actors on global health’.35 A staff exchange programme between MOC and MOPH was also suggested to promote mutual understanding among the ministries.36

Overall, the processes of health engagement with trade negotiations have both strengths and weaknesses. The institutional mechanisms are essential, but slow to implement and in their operation due to hierarchies of governmental administration with involvement of several decision makers, thus not sufficient to advocate for health goals alone. The interagency committees help increase the understanding of trade and health among health and non-health actors, but most are ad hoc and lack the constant and consistent participation of their members. So far, interagency committees, including the NCITHS, have not had a great impact on the trade policy agenda. The NHA is successful in terms of enabling the broad array of actors from health and non-health sectors to participate in discussion around NHA resolutions. However, not all resolutions concerning trade and health have been accepted by trade actors,37 and may thus be seen as unsuccessful in terms of policy implementation, even if they may have been successful in terms of policy process. It is also the case that informal mechanisms appear to help foster trust amongst actors, but assessment of their impact on policy coherence is unclear. This study refutes the literature citing that Thailand is a country that has achieved trade and health policy coherence. However, it confirms that the country has established important co-ordinating mechanisms between trade and health agencies to communicate a health position for trade considerations, which has influenced the process to some degree over recent years. Perhaps the most significant, visible, improvement coming from the Thai case is the investment in constant capacity development of health actors in understanding the linkages between trade and health, and the MOPH improving its own mechanisms to better engage with the trade negotiation process.

Conclusion

The ability to engage in successful GHD begins at the national level, with capacity for health agencies to influence the wider domestic trade agenda, and for other agencies to appreciate the health implications of wider agreements. Given that power within diplomacy more generally resides with those beyond the health community, then it becomes de facto the responsibility of the health community to initiate this. As this article illustrates, it is important in this respect for countries to consider four complementary elements for developing capacity in GHD: (1) the power and legitimacy of the relevant actors; (2) the ability of the actors to perform GHD activities; (3) formal structures for interaction and negotiation and (4) informal networks and relationships between those involved in different agencies.

This article has analysed how one country—Thailand—has sought to develop capacity to engage in GHD. Although this active development is perhaps an exception, it serves well to provide lessons, of which there are three most notables. First, it is essential to develop capacity for both health and non-health actors. These actors all need to understand the health impact of non-health policies, and vice versa, and to integrate assessment of these impacts, if they are going to have informed dialogue and health issues be better reflected in trade negotiations. Second, mechanisms for interaction among relevant agencies may benefit from combining both the institutionalized and the ad hoc. Third, an informal network is always essential in building the trust upon which collaboration—especially cross-sector—is based.

It is worth noting that countries should also seek to share experience and capacity with likeminded others. Certainly, the capacity developed in Thailand was also used to assist other South-East Asia Region (SEAR) Member States in developing and strengthening capacity of their health and related professionals. For instance, the Thai MOPH, in collaboration with the WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia, and the ThaiHealth Global Link Initiative Program, organized the first regional training course on global health in May 2010, covering issues debated at the 63rd World Health Assembly. The course is now to be conducted in SEAR Member States on a rotation basis prior to WHA and other global health meetings every year (SEARO WHO 2010).

In sum, developing sustainable capacity requires long-term commitment and strong leadership. The activities in Thailand have been going for more than 20 years. These activities are based on a comprehensive strategy, which includes consideration of the individual, nodes, networks and enabling environment (INNE). Attempts at creating policy coherence are done under several inter-ministerial mechanisms, created by the trade ministry as well as the health ministry. The promulgation of the new constitution, in 2007, which requires parliamentary approval of trade negotiation frameworks, and the promulgation of the National Health Act in 2007, has allowed a national mechanism for multi-stakeholder public policy dialogue and development. This provides a good sociopolitical foundation, but requires capacity in GHD to be continually nourished and further strengthened to ensure that future challenges of increasing trade liberalization, such as through the establishment of the ASEAN Community, may be adequately addressed.

Funding

This work was supported by the Rockefeller Foundation (2010 DSN 30).

Ethics Clearance

This research received ethics approval from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Suwit Wibulpolprasert for his comments on the initial draft of this article and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments to improve this article.

Footnotes

3 Ministers from economic ministries, including ministries of commerce, foreign affairs, finance, and agriculture and co-operatives.

4 During year 2004–2006.

5 During year 2004–2007.

6 Article 190 of the National Constitution states any treaty that has an extensive impact on national economic and social stability is required approval of the National Assembly.

7 Interview with Dr Suwit Wibulpolprasert, a senior advisor (on disease control) to MOPH on 16 November 2010.

8 Interview with an anonymous MFA official on 15 December 2010.

9 Interview with an anonymous academic on 7 January 2011.

10 Interview with Ms Chutima Bunyapraphasara, a trade inspector general of MOC on 11 February 2011.

11 Interview with Mrs Sirina Pavarolavidya, the Chair of the NCITHS on 9 February 2011.

12 Interview with Dr Suwit Wibulpolprasert, a senior advisor (on disease control) to MOPH on 16 November 2010.

14 Interview with Dr Suwit Wibulpolprasert, a senior advisor (on disease control) to MOPH on 16 November 2010.

15 A 5-year project during 2003–2007 (www.thailandwto.org).

17 TRIPS flexibilities and access to medicines discussed at 2007 PMAC, Implication of international trade and trade agreements on primary health care discussed at 2008 PMAC, Foreign policy and global health discussed at 2009 PMAC and Trade in health services and impact on HRH discussed at 2011 PMAC.

18 Interview with Dr Suwit Wibulpolprasert, a senior advisor (on disease control) to MOPH on 16 November 2010.

19 Interview with Dr Songyot Chaichana, a health inspector general of MOPH on 30 December 2010.

20 Interview with Dr Suwit Wibulpolprasert, a senior advisor (on disease control) to MOPH on 16 November 2010.

21 Interview with an anonymous academic on 7 January 2011.

22 Interview with Dr William Aldis, the then WHO Representative to Thailand on 21 December 2010.

23 Interview with Dr Viroj Tangcharoensathien, a senior advisor (on health economics) to MOPH on 27 December 2010.

24 Observation at the 3rd NHA held in Bangkok during 15–17 November 2010.

25 Interview with an anonymous medical doctor on 22 December 2010.

26 Interview with Ms Pimchanok Vonkhorporn, Director of Bureau of Multilateral trade negotiations on 22 December 2010.

27 Interview with Dr Mongkol Na Songkhla, the then former Minister of Public Health on 19 November 2010.

28 Interview with Dr Suwit Wibulpolprasert, a senior advisor (on disease control) to MOPH on 16 November 2010.

30 Interview with Dr Suwit Wibulpolprasert, a senior advisor (on disease control) to MOPH on 16 November 2010.

31 WHA 59.26 International trade and health.

32 Interview with Dr Suwit Wibulpolprasert, a senior advisor (on disease control) to MOPH on 16 November 2010.

33 Interview with Dr Suwit Wibulpolprasert, a senior advisor (on disease control) to MOPH on 16 November 2010.

34 Interview with Dr. William Aldis, the then WHO Representative to Thailand on 21 December 2010.

35 Interview with an anonymous intergovernmental organization representative on 11 January 2011.

36 Interview with an anonymous MFA official on 15 December 2010.

37 Observation at the focus group meeting on a feasibility of using the Health Impact Assessment (HIA) on trade liberalization held by the NHCO in Bangkok on 31 August 2011.

References

- Ahearn RJ, Morrison WM. U.S.-Thailand Free Trade Agreement Negotiations. Washington, DC: The Library of Congress; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blouin C. Trade policy and health: from conflicting interests to policy coherence. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2007;85:169–73. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.037143. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2636226/, accessed 10 October 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan M, Støre JG, Kouchner K. Foreign policy and global public health: working together towards common goals. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2008;86 doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.056002. 498, 10.2471/BLT.08.056002. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/7/08-056002/en/, accessed 14 June 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crettol C, Gavin C. 1990 Thailand—restrictions on importation of and internal taxes on cigarettes, a GATT decision—November 7, 1990. http://www.cptech.org/ip/health/country/gatt-thai.html, accessed 9 March 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Drager N, Fidler D. Foreign policy, trade and health: at the cutting edge of global health diplomacy. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2007 doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.041079. 85:162. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/3/07-041079/en/, accessed 15 June 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler D. 2009 Background paper on developing a research agenda for the Bellagio meeting #1, 23–26 March 2009. Globalization, Trade and Health Working Papers Series, World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Global Health Diplomacy Network (GHD-NET) 2009 http://www.ghd-net.org/, accessed 15 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Helble M, Mok EA, Kessomboon N. Policy coherence between trade and health through national institutional arrangements: studies of Colombia and Thailand. Harvard Health Policy Review. 2008;9:100–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hunton Williams LLP. Thailand-US FTA: A Roadmap to Negotiations. Washington, DC: The Strategic International Business Practice of Hunton & Williams LLP; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- International Health Policy Program (IHPP), WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. Impact Assessment of TRIPS Plus Provisions on Health Expenditure and Access to Medicines. New Delhi: WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- International Health Policy Program (IHPP), International Trade and Health Programme. Framework on Strategic Development Towards Policy Coherence Between International Trade And Health, 2011–2015. Nonthaburi: International Health Policy Programme, Ministry of Public Health, and Health Systems Research Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kessomboon N, Limpananont J, Kulsomboon V, et al. Impact on access to medicines from TRIPS-Plus: a case study of Thai-US FTA. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health. 2010;41:667–77. http://www.tm.mahidol.ac.th/seameo/2010-41-3/23-4785.pdf, accessed 15 June 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevany S. Global health diplomacy, 'smart power', and the new world order. Global Public Health: An International Journal for Research, Policy and Practice. 2014;9:787–807. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.921219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch I. Global health diplomacy: how foreign policy can influence health. BMJ. 2011;342:d3154. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3154. http://graduateinstitute.ch/files/live/sites/iheid/files/sites/globalhealth/shared/1894/Publications/global%20health%20diplomacy_how%20foreign%20policy%20can%20influence%20health_bmj.d3154.full.pdf, accessed 15 June 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kickbusch I, Silberschmidt G, Buss P. Global health diplomacy: the need for new perspectives, strategic approaches and skills in global health. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2007;85:230–2. doi: 10.2471/BLT.06.039222. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/85/3/06-039222/en/, accessed 15 June 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Smith RD. What is ‘global health diplomacy'? A conceptual review. Global Health Governance. 2011 5. http://summit.sfu.ca/item/10865, accessed 15 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Health. Thailand Health Profile 2005–2007. Nonthaburi: Bureau of Policy and Strategy, Ministry of Public Health; 2008a. http://www.moph.go.th/ops/thp/thp/en/index.php,accessed 10 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Health. Trade Liberalisation: Its Adverse Impacts on Our Borderless Health Problems. 2008b. Speech of the Deputy of Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Public Health addressed at the 9th Session of the ASEAN Health Minister Meeting in Philippines in 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Health. Thailand Health Profile 2551–2553. 2010. Nonthaburi: Bureau of Policy and Strategy, Ministry of Public Health. http://www.moph.go.th/ops/thp/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=176&Itemid=2, accessed 10 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R, Agle BR, Wood DJ. Toward a theory of stakeholder identification and salience: defining the principle of who and what really counts. Academy of Management Review. 1997;22:853–86. [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on International Trade and Health Study. Report of the 1st Meeting of the National Commission on International Trade and Health Study 2010. Nonthaburi: National Health Commission Office; 2010a. [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on International Trade and Health Study. Report of the 2nd Meeting of the National Commission on International Trade and Health Study 2010. Nonthaburi: National Health Commission Office; 2010b. [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on International Trade and Health Study. Report of the 3rd Meeting of the National Commission on International Trade and Health Study. Nonthaburi: National Health Commission Office; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission. Appointment of the National Commission on International Trade and Health Study 2009. Nonthaburi: National Health Commission Office; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission Office. Birth of Health Assembly: Crystallization of Learning Towards Wellbeing. Nonthaburi: Sangsue Co. Ltd; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- National Health Commission Office. Agenda for Thursday, December 16. On Site Newsletter. 2010;2:1. [Google Scholar]

- Pachanee C, Wibulpolprasert S. Interregional Workshop on Trade and Health. New Delhi: 2004. Policy coherence between health related trade and health system development in Thailand. WHO/SEARO. [Google Scholar]

- Peamsilpakulchorn P. The domestic politics of Thailand's bilateral free trade agreement policy. International Public Policy Review. 2006;2:74–102. [Google Scholar]

- Pibulsonggram N. Process and progress of Thailand-US FTA negotiations. 2004 Bangkok. http://www.thaifta.com/english/ftaus_process.pdf, accessed 10 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A, Robert GB, editors. Analyzing Qualitative Data. London: Routledge; 1994. pp. 173–94. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Thai Government. 2007 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand B.E. 2550 (2007). http://www.isaanlawyers.com/constitution%20thailand%202007%20-%202550.pdf, accessed 20 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sally R. Thailand's new FTAs and its trade policies post-Asian crisis: an assessment. International Conference ‘From WTO to Bilateral FTAs’. 2005 Bangkok. [Google Scholar]

- Sarnsamak P. BOI, NHC aim to cut ill effects of medical hub scheme. The Nation. 2011 : Bangkok 3 February 2011. http://www.nationmultimedia.com/2011/02/03/national/BOI-NHC-aim-to-cut-ill-effects-of-medical-hub-sche-30147817.html, accessed 13 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- SEARO WHO. Capacity Building of Member States on Global Health. New Delhi: WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith RD, Lee K, Drager N. Trade and health: an agenda for action. Lancet. 2009;373:768–73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61780-8. http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(08)61780-8/fulltext, accessed 15 June 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talerngsri P, Vonkhorporn P. Trade policy in Thailand: pursuing a dual track approach. ASEAN Economic Bulletin. 2005;22:15. http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/25773844?uid=3739136&uid=2129&uid=2&uid=70&uid=4&sid=21104308662323, accessed 15 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tangcharoensathien V. Global Health Diplomacy: Executive Education Training Course. Beijing: Chinese Ministry of Health and the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health; 2010. How does Thailand cooperate at the national level for global health? [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS, UNDP, WHO. Policy brief. Using the TRIPS Flexibilities to Improve Access to Treatment. 2011 http://content.undp.org/go/cms-service/stream/asset/?asset_id=3259398. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Capacity Development. New York: United Nations Development Programme; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Vonkhorporn P. International Trade and Health. Nonthaburi: International Health Policy Programme, Ministry of Public Health; 2010. International trade and health systems. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization and World Trade Organization. WTO agreements and public health: a joint study by the WHO and the WTO secretariat. Geneva: World Health Organization and World Trade Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]