Abstract

Background Artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) has been the first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria in Cameroon since 2004 and Nigeria since 2005, though many febrile patients receive less effective antimalarials. Patients often rely on providers to select treatment, and interventions are needed to improve providers’ practice and encourage them to adhere to clinical guidelines.

Methods Providers’ adherence to malaria treatment guidelines was examined using data collected in Cameroon and Nigeria at public and mission facilities, pharmacies and drug stores. Providers’ choice of antimalarial was investigated separately for each country. Multilevel logistic regression was used to determine whether providers were more likely to choose ACT if they knew it was the first-line antimalarial. Multiple imputation was used to impute missing data that arose when linking exit survey responses to details of the provider responsible for selecting treatment.

Results There was a gap between providers’ knowledge and their practice in both countries, as providers’ decision to supply ACT was not significantly associated with knowledge of the first-line antimalarial. Providers were, however, more likely to supply ACT if it was the type of antimalarial they prefer. Other factors were country-specific, and indicated providers can be influenced by what they perceived their patients prefer or could afford, as well as information about their symptoms, previous treatment, the type of outlet and availability of ACT.

Conclusions Public health interventions to improve the treatment of uncomplicated malaria should strive to change what providers prefer, rather than focus on what they know. Interventions to improve adherence to malaria treatment guidelines should emphasize that ACT is the recommended antimalarial, and it should be used for all patients with uncomplicated malaria. Interventions should also be tailored to the local setting, as there were differences between the two countries in providers’ choice of antimalarial, and who or what influenced their practice.

Keywords: Cameroon, malaria, multilevel analysis, multiple imputation, Nigeria, provider practice

KEY MESSAGES.

Providers’ choice of antimalarial was not determined by their knowledge of the malaria treatment guidelines.

Providers make treatment decisions based on their preference, attributes of the patient and resources available.

Strategies to disseminate clinical guidelines need to identify mechanisms that change preference and practice in the local setting.

Introduction

Clinical guidelines are systematically developed statements to assist providers’ decision making on the appropriate care for specific clinical conditions (Field et al. 1992). By establishing common standards for diagnosis and treatment, they are central to efforts to improve the quality of health care and can expedite the introduction of new health technologies (Cabana et al. 1999; Woolf et al. 2012). Each year governments invest considerable resources in the development and distribution of clinical guidelines to ensure providers have access to the latest scientific evidence. Despite these efforts, there are challenges translating evidence into practice and patients often receive substandard care (Grol and Grimshaw 2003). Moreover, several studies on the performance of health care providers have identified a knowledge–practice gap, which suggests that public health interventions to disseminate clinical guidelines may not be sufficient to change providers’ practice (Das et al. 2008; Leonard and Masatu 2010).

Over the past decade, national malaria treatment policies have been revised in all African countries to establish artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) as the first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria. However, uptake of ACT has been slow in some countries and studies undertaken in Cameroon and Nigeria in 2009, 4 years after ACT became the recommended first-line treatment, showed that many patients treated for malaria did not receive an ACT (Mangham et al. 2011; 2012). The situation in southeast Nigeria was of particular concern as only 22% of febrile patients seeking treatment at primary health centres, pharmacies and drugs stores received an ACT (Mangham et al. 2011). These studies also showed that providers were routinely responsible for the choice of treatment at the public and mission facilities and advised on treatment in more than one-third of cases at pharmacies and drug stores (Mangham et al. 2011; 2012).

Interventions to improve malaria diagnosis and treatment have traditionally focused on ensuring providers are informed about policy changes and have used training and job aids to improve their knowledge of the clinical guidelines (Smith et al. 2009). However, evidence from intervention and cross-sectional studies show access to in-service training, guidelines and job aids often have a limited effect in changing providers’ practice (Rowe et al. 2000, 2003; Zurovac et al. 2004, 2005; Osterholt et al. 2006; Zurovac et al. 2008a,b; Smith et al. 2009).

It is timely to explore the relationship between providers’ practice in treating uncomplicated malaria and their knowledge of the clinical guidelines, as malaria treatment guidelines undergo further revision to advise on the use of malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and dissemination strategies are being developed. Moreover, early evidence suggests that malaria RDTs will only be cost-effective if providers adhere to the malaria treatment guidelines: testing before treatment should reduce the number of febrile patients consuming antimalarials that they do not need, but this requires providers to adhere to the test results when making treatment decisions (Lubell et al. 2008).

In this article, we examine providers’ adherence to malaria treatment guidelines at public and mission facilities, pharmacies and drug stores in urban and rural areas of Cameroon and Nigeria prior to the introduction of malaria RDTs. We investigate what influences providers’ choice of antimalarial, and assess whether providers were more likely to select an ACT if they knew it was the first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria. This exploratory analysis was undertaken to generate hypotheses and guide the design of interventions to support the roll-out of malaria RDTs with updated clinical guidelines. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the interventions are being evaluated in cluster-randomized trials at selected sites in Cameroon and Nigeria (Wiseman et al. 2012a,b).

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted at public and mission health facilities, pharmacies and drug stores (henceforth referred to collectively as outlets) in urban and rural areas of Cameroon and Nigeria, where cluster-randomized trials would be conducted to evaluate interventions to support the introduction of malaria RDTs (Wiseman et al. 2012a,b). In Cameroon, the two sites were Yaoundé in the Centre region, which is urban and predominantly French speaking, and Bamenda and seven rural districts in the northwest region where English and pidgin-English are widely spoken. In Nigeria, both sites were in Enugu State and included urban communities in Enugu, and rural communities in Udi.

Malaria is endemic in all four sites and occurs throughout the year. At the time the study was conducted, the national malaria treatment guidelines in both countries advised that malaria should be suspected in all patients presenting with a fever or history of fever, patients should be tested prior to treatment where malaria testing was available, but in the absence of a confirmed diagnosis presumptive treatment for uncomplicated malaria was recommended (Ministry of Health of the Federal Republic of Nigeria 2005; Ministry of Public Health of the Republic of Cameroon 2008). ACT was the first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria (in all patients except pregnant women), and was typically more expensive than other types of antimalarial. In all outlets patients pay for the treatment they receive, though there were exemptions for children under five and pregnant women attending public facilities.

In Cameroon and Nigeria, malaria is routinely treated using antimalarials obtained at primary care facilities, outpatient departments, pharmacies and drug stores. In the public and mission facilities in Cameroon, malaria cases are treated by doctors, nurses and pharmacists, and some facilities have a laboratory technician able to conduct malaria microscopy (Mangham et al. 2012). In Enugu State, malaria is often treated in primary health centres and health posts that do not offer malaria testing and are staffed by nurses, and health extension workers (Mangham et al. 2011). Medicine retailers were present in all study sites. In both countries, pharmacies are legally required to have a trained pharmacist in order to sell prescription-only and over-the-counter medicines, and they are more prevalent in urban areas. Drug stores, also known as patent medicine dealers, are formally recognized in the Nigerian health system and staff are eligible to sell over-the-counter medicines (including antimalarials) without any specific qualifications or training (Uzochukwu et al. 2009). In Cameroon, drug stores operate under a business licence in the Anglophone regions (which includes the northwest region) and are staffed by providers with no or few health qualifications (Hughes et al. 2012).

Survey sampling and activities

Stratified cluster surveys were conducted with patients and caregivers exiting health facilities, pharmacies and drug stores and with providers working at these outlets between July and December 2009. Sample size calculations were undertaken separately for each country and sought to determine the proportion of febrile patients seeking treatment that were supplied an ACT, with a given level of precision (Mangham et al. 2011, 2012). The sampling, conducted in March–May 2009, was based on an enumeration of outlets that regularly dispense antimalarials in the study sites. The enumeration was undertaken for the study and involved fieldworkers locating all outlets that were operating in each study site and recording the name, type and global positioning system (GPS) co-ordinates of each. In each country, two-stage sampling was used: first to randomly select communities, having stratified by study site, and second to select outlets that dispense antimalarials. In both countries, all public primary care facilities were included and pharmacies and drug stores were randomly selected with probability proportionate to their number in the local community. In Cameroon, all district hospitals and mission facilities in the selected communities were also included because they were also an important source of treatment in Yaoundé and Bamenda.

Questionnaires were developed and pre-tested at outlets that were not included in the survey. The exit questionnaire collected data about the patient, previous treatment seeking, the consultation or interaction with the health care provider and the treatment prescribed and received. Individuals were eligible to complete the exit survey if they reported seeking treatment for a fever, either for themselves or another (who may or may not be present), the patient had no signs of severe malaria, and they gave informed written consent. Providers were surveyed to collect data on pre-service and in-service training, their knowledge of the national treatment guidelines, and their preference for treating patients with symptoms of uncomplicated malaria. All providers that prescribed or dispensed antimalarials, were available at the time of the survey, and gave informed written consent were eligible to participate. In addition, one provider at each outlet completed a questionnaire which asked about the services and medicines available and the procurement of antimalarials. All questionnaires were individually administered by trained fieldworkers working under the supervision of site co-ordinators. Data were double-entered and verified using Microsoft Access 2007 (Microsoft Inc., Redmond Washington) and data entry errors were corrected to ensure consistency with the original form.

Data sources

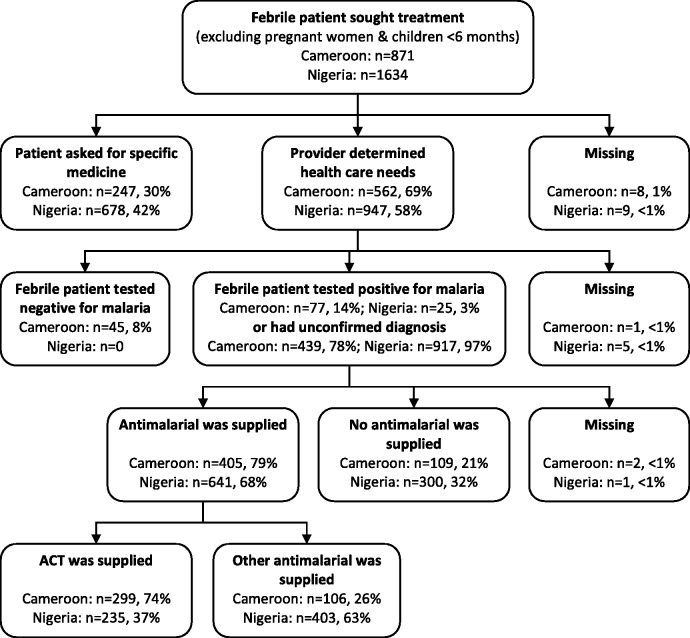

Providers’ choice of antimalarial was investigated using patient exit and provider survey data from Cameroon and Nigeria. Data analysis was undertaken separately for each country. Exit survey responses that fulfilled the following criteria were included: (1) the patient or caregiver reported seeking treatment for a fever; (2) the patient was not pregnant or under 6 months of age; (3) the patient or caregiver did not request a specific medicine; (4) the patient had a presumptive or confirmed malaria diagnosis (i.e. patients with a negative malaria test result were excluded) and (5) an antimalarial was prescribed or received (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of patients and caregivers that sought for febrile illness at public and mission facilities, pharmacies and drug stores in Cameroon and Nigeria.

Multilevel logistic regressions were used to investigate what factors influenced providers’ choice of antimalarial. The dependent variable was a binary outcome that indicates whether or not the provider supplied an ACT (coded 1 if an ACT was prescribed or received, and 0 otherwise). This variable was derived from multiple questions about all medicines that were prescribed or received whilst at the health facility, pharmacy or drug store. Specifically, patients were asked if they had received a prescription and if so, the fieldworker asked to see the prescription so information could be recorded about the brand and dose of medicines prescribed. Similarly, patients were asked what medicines they had received whilst at the facility, including any medicines consumed during the consultation. Fieldworkers recorded the brand and dose of the medicines received, where possible, by copying information about the brand and dose of the medicines they were shown. Information about the brand of medicines prescribed and received was used to construct a variable indicating whether the patient had been prescribed or received an antimalarial (yes/no) and whether the antimalarial was an ACT (yes/no).

A theory-driven approach to model building was adopted. Explanatory variables hypothesized to predict provider practice included attributes of the provider, the patient, their interaction, and also the outlet in which the interaction took place (Supplementary Appendix Table S1). The explanatory variables were selected for inclusion in the econometric model with reference to economic literature on agency theory, new institutional economics and behavioural economics (Arrow 1963; Rabin 1998; Williamson 2000). To investigate the relationship between providers’ knowledge and practice, the following provider attributes were included: whether providers knew an ACT was the recommended first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria; their access to national malaria treatment guidelines; whether they had attended in-service training on malaria in the past 3 years; their highest level of pre-service health training; whether they state ACT to be best treatment for uncomplicated malaria; and whether they report ACT is the type of antimalarial their patients most often request. The last two were included because there may be a difference between providers’ knowledge of the malaria treatment guidelines, the type of antimalarial they state they prefer, and the type of antimalarial they perceive their patients prefer.

It was also assumed that providers may select treatment based on the attributes of the patient or information obtained during the interaction. The explanatory variables included the following patient attributes: gender; age; household wealth (relative to others who sought treatment); the education of the patient or caregiver; whether treatment was sought within 2 days of the onset of fever; and whether previous treatment had been sought for this illness episode, including whether an antimalarial had been taken. In addition, relevant aspects of the provider–patient interaction were: whether the patient was examined; had a presumptive or confirmed malaria diagnosis; and whether the provider was told that the patient had diarrhoea or had been vomiting (as these symptoms may affect the suitability of different medicines).

Attributes of the outlet may also have some bearing on the treatment supplied, as contextual factors may constrain the providers’ choice of treatment. Outlet attributes included in the model were: outlet type; availability of ACT; whether antimalarials were received from a drug company representative (whose promotional activities may be a source of information or influence); and whether the outlet was in an urban or rural community.

Relational databases

To investigate the relationship between providers’ knowledge and practice, it was necessary to prepare a database that linked patient exit responses (1) to information about the outlet and (2) to the individual provider that was responsible for selecting treatment. The outlet at which the exit survey was conducted was known for all patients. Patients and caregivers were asked to describe all the providers that were involved in supplying care, and fieldworkers recorded the unique code that identified each provider. When care was supplied by a single provider then it was straightforward to link the patient and provider data if the provider had completed the survey. When care was supplied by two or more providers and the cadre of all providers was known, then it was assumed the more senior provider decided which treatment to supply. For example, if care was supplied by a registered nurse and a pharmacy attendant, we assume the pharmacy attendant dispensed the type of antimalarial prescribed by the registered nurse. In the remaining cases, it was not possible to identify the individual provider, and therefore data on provider attributes were missing.

Econometric analysis

The econometric analysis involved multiple imputation and multilevel logistic regression (van Buuren 2010; Carpenter and Kenward 2013). There were almost complete data on patient, and outlet attributes, though up to 26% of cases were missing provider attributes due to challenges linking the databases (Supplementary Appendix Table S1). The missing data were binary or categorical responses and were non-monotone. The proportion of missing provider data was disproportionately greater at public and mission facilities in Cameroon, where ACT was available, and at outlets located in urban communities. Thus, the missing data were presumed to be conditional on attributes of the outlet, which is known as ‘missing at random’ (MAR) in the statistical literature (Sterne et al. 2009).

Given the scale of missing data and suggested missingness mechanism, multiple imputation using chained equations was appropriate since analysis using only complete cases may be biased (White and Carlin 2010). Multiple imputation is a statistical technique for dealing with data ‘missing at random’ and is recommended when more than 10% of observations would be excluded in a complete-case analysis (Burton and Altman 2004). Multiple imputation allows for uncertainty about the missing data by generating multiple copies of datasets in which missing values are replaced by imputed values, and then uses standard statistical methods to estimate the model of interest using the imputed datasets (Sterne et al. 2009). Multiple imputation methods should respect the data structure; ignoring the data hierarchy can lead to bias because the variance of the imputation distribution would be underestimated (Goldstein et al. 2009). REALCOM-IMPUTE is statistical software that enables multiple imputation for a two-level model and fits the specified imputation model using Markov Chain Monte Carlo methods (Carpenter et al. 2011).

The linked patient–provider data have a hierarchical structure, as patients may be clustered by provider and by outlet. For computational reasons it was not possible to take into account all possible levels, and a two-level model was specified with patients and provider attributes at level 1, and outlet attributes at level 2. Outlet was defined as the level 2 identifier to reflect the sampling strategy, the amount of clustering expected at this level, and because it was known for every observation (while it was not always possible to identify which provider supplied treatment).

For a two-level logistic regression, the dependent variable ωij is defined as the probability that the antimalarial supplied is an ACT for patient i from outlet j, and [] is the log odds that the antimalarial supplied is an ACT. The econometric model for the providers’ choice of antimalarial was specified as:

where α was the intercept; Vij were attributes of the provider supplying an antimalarial to patient i at outlet j; Pij were attributes of patient i receiving an antimalarial at outlet j; Fj were attributes of outlet j; β, λ and θ were the parameters associated with the explanatory variables; εij and uj were the residuals at levels 1 and 2, respectively, and capture unobserved variation, measurement and specification errors. The statistical significance was measured using the Wald test, and P values are reported along with 95% confidence intervals. Multicollinearity amongst the explanatory variables was assessed in the complete cases using the variance inflation factor. We used the Ramsey RESET test to check for misspecification of the regression model (Rice 2000). This is a general test for problems associated with functional form and can identify errors associated with omitted variable bias, measurement error and simultaneity bias if they lead to nonlinearity in the relationship between the dependent and explanatory variables (Jones 2007). The models were also estimated without the explanatory variable for providers’ stated preference to investigate simultaneity bias that would arise if providers’ preference over alternative antimalarials was determined at the same time they acquired knowledge of the recommended treatment. The proportion of the total variance that was attributable to the outlet level of the model was estimated using the variance partition coefficient (VPC) (Hox 2010). The VPC is similar to the intracluster correlation, though used when the dependent variable is discrete, and calculated as:

where τ2 is the variance at level 2 and the variance at level 1 is the variance of the standard logistic distribution (π2/3 = 3.29). Larger values of the VPC (0 < VPC < 1) indicate that the level has greater potential to influence the value of the dependent variable (Hox 2010).

Two-level logistic regressions were estimated using adaptive quadrature to approximate the marginal likelihood by numerical integration in Stata 12.1 (StataCorp 2009). The model was initially estimated with data from each country using listwise deletion, and therefore used only those cases that were complete and have no missing data (also known as complete cases). The model was subsequently estimated using data from 50 imputations generated by two-level multiple imputation using chained equations completed using Stata 12.1 and REALCOM-IMPUTE with a burn-in of 2000 and 500 further updates between each imputation (White et al. 2011). To avoid bias the imputation model used all variables that were included the analysis model (White et al. 2011).

Results

Description of the sample

The linked patient–provider database contained data on 2451 cases of febrile illness that sought treatment at public and mission health facilities and medicine retailers, with 871 cases from Cameroon and 1634 from Nigeria (Figure 1). Almost all outlets and individuals approached were willing to participate in the study: in Cameroon 11 outlets (5%), 10 providers (2%) and 31 (3%) patients refused, while in Nigeria all outlets and providers gave consent but 31 patients (2%) refused (Mangham et al. 2011, 2012). The provider was presumed to be responsible for diagnosis and treatment when the patient or caregiver reported that they did not ask for a specific medicine. There were 516 patients in Cameroon and 942 patients in Nigeria eligible for malaria treatment, based on either a symptomatic or confirmed diagnosis (having excluded cases which requested a specific medicine and 45 patients from Cameroon that tested negative for malaria). Of the eligible patients, 405 (79%) patients in Cameroon and 641 (68%) patients in Nigeria were supplied an antimalarial. In Cameroon, providers often chose to supply ACT, (74% of antimalarials supplied), though quinine either as a tablet or injection was also common (21%) (Table 1). However, in Nigeria providers regularly supplied sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine (40%) as well as ACT (37%), and other alternatives included artesunate monotherapy (11%) and chloroquine (10%).

Table 1.

Providers’ choice of antimalarial, by country and type of outlet

| Type of antimalarial | Cameroon (N = 405) |

Nigeria (N = 641) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public |

Mission |

Pharmacy |

Drug store |

Public |

Pharmacy |

Drug store |

||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| N = 202 | N = 80 | N = 52 | N = 71 | N = 123 | N = 323 | N = 318 | ||||||||

| Artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) | 164 | 81.2 | 52 | 65.0 | 51 | 98.1 | 32 | 45.1 | 158 | 48.9 | 24 | 40.0 | 53 | 20.5 |

| Amodiaquine | – | – | – | – | – | – | 5 | 7.0 | 4 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Artesunate monotherapy | 3 | 1.5 | 2 | 2.5 | – | – | – | – | 30 | 9.3 | 10 | 16.7 | 29 | 11.2 |

| Chloroquine | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1.4 | 16 | 5.0 | – | – | 51 | 19.8 |

| Halofantrine | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.4 |

| Quinine | 35 | 17.3 | 22 | 27.5 | – | – | 28 | 39.4 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 1.7 | – | – |

| Sulphadoxine–pyrimethamine (SP) | – | – | 4 | 5.0 | 1 | 1.9 | 5 | 7.0 | 111 | 34.4 | 23 | 38.3 | 123 | 47.7 |

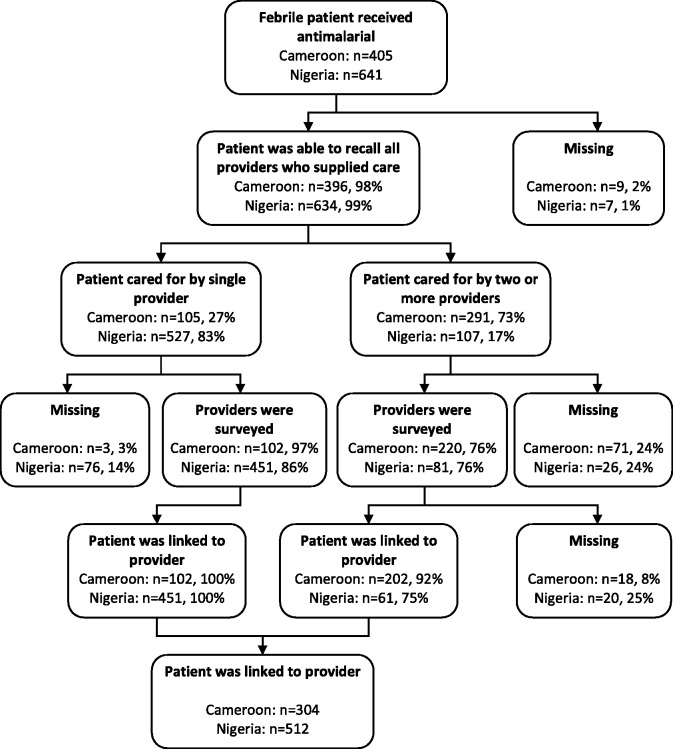

Linking patients to the provider that supplied treatment

Across the two countries 1046 patients were supplied an antimalarial (Figure 2). Almost all patients and caregivers were able to describe the providers they interacted with whilst at the public or mission health facility, pharmacy or drug store (396/405 in Cameroon and 634/641 in Nigeria). In Nigeria most cases (527/641) involved interactions with a single provider, while in Cameroon the majority of cases (291/405) involved interaction with two or more providers. It was possible to link the patient to details about the provider in 75% of cases (304/405) in Cameroon and 80% of cases (512/641) in Nigeria (Figure 2). In the remaining cases, the provider’s details were unknown because the respondent was unable to recall one or more of the providers who supplied care (9 in Cameroon and 7 in Nigeria); care was supplied by one or more providers who did not complete the survey (74 in Cameroon and 102 in Nigeria); or patients received care from multiple providers of the same cadre (18 in Cameroon and 20 in Nigeria).

Figure 2.

Flow chart showing how patients were linked to providers.

Provider, outlet and patient attributes

The febrile patients were linked to 119 providers working at 105 outlets in Cameroon and 107 providers working at 93 outlets in Nigeria (Table 2). Approximately two-thirds of these providers accurately reported ACT was the first-line treatment for uncomplicated malaria, with better knowledge of the recommended treatment reported among providers working at public facilities. In Cameroon, 90% of providers at public facilities knew ACT was recommended compared to 65% at mission facilities, 50% at pharmacies and 45% at drug stores; while in Nigeria, 79% of providers at public facilities, 73% at pharmacies and 36% at drug stores accurately reported ACT was the recommended first-line treatment. Providers’ access to malaria treatment guidelines and training also differed by country and type of outlet, with providers at public and mission health facilities more likely to report having access to the national malaria treatment guidelines than those working at pharmacies and drug stores. Providers’ responses to survey questions on which type of antimalarial their patients usually ask for and which antimalarial is best for uncomplicated malaria also varied by setting. It was also interesting to note there were 20 providers in Cameroon and 21 providers in Nigeria who knew ACT was recommended but did not state it was their preferred treatment for uncomplicated malaria. Almost all pharmacies were located in urban communities. The majority of outlets had ACT available at the time of the survey, though there was considerable variation by type of outlet, ranging from 57% of the drug stores surveyed in Cameroon to 100% of the pharmacies surveyed in Nigeria.

Table 2.

Provider and outlet attributes, by country and type of outlet

| Attributes | Cameroon (N = 405) |

Nigeria (N = 641) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public |

Mission |

Pharmacy |

Drug store |

Public |

Pharmacy |

Drug store |

||||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Provider | N = 48 | N = 20 | N = 22 | N = 29 | N = 38 | N = 22 | N = 47 | |||||||

| Knew ACT was first-line antimalariala | 43 | 89.6 | 13 | 65.0 | 11 | 50.0 | 13 | 44.8 | 30 | 78.9 | 16 | 72.7 | 17 | 36.2 |

| Reports has access to malaria guidelinesa | 35 | 72.9 | 12 | 60.0 | 2 | 9.1 | 1 | 3.4 | 12 | 31.6 | 1 | 4.5 | 1 | 2.1 |

| Has attended malaria traininga | 23 | 47.9 | 5 | 25.0 | 6 | 27.3 | 1 | 3.4 | 12 | 31.6 | 4 | 18.2 | 14 | 29.8 |

| Pre-service trainingb | ||||||||||||||

| Doctor | 10 | 20.8 | 6 | 30.0 | – | – | – | – | 6 | 15.8 | – | – | – | – |

| Nurse or midwife | 25 | 52.1 | 5 | 25.0 | 3 | 13.6 | 3 | 10.3 | 5 | 13.2 | 2 | 9.1 | – | – |

| Pharmacist | 1 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 45.5 | 2 | 6.9 | – | – | 3 | 13.6 | – | – |

| Nurse assistant | 7 | 14.6 | 6 | 30.0 | 2 | 9.1 | 15 | 51.7 | – | – | – | – | – | |

| CHO or CHEW | – | – | – | – | 26 | 68.4 | 2 | 9.1 | 3 | 6.4 | ||||

| None (attendant or drug seller) | 5 | 10.4 | 3 | 15.0 | 7 | 31.8 | 9 | 31.0 | 1 | 2.6 | 15 | 68.2 | 44 | 93.6 |

| Reported patients usually ask for ACTa | 22 | 45.8 | 8 | 40.0 | 18 | 81.8 | 9 | 31.0 | 11 | 28.9 | 12 | 54.5 | 8 | 17.0 |

| Stated ACT was best antimalarial for uncomplicated malariaa | 38 | 79.2 | 9 | 45.0 | 15 | 68.2 | 23 | 79.3 | 22 | 57.9 | 19 | 86.4 | 24 | 51.1 |

| Knew ACT was the first-line antimalarial but did not state it was the best antimalarial | 9 | 18.8 | 6 | 30.0 | 4 | 18.2 | 1 | 3.4 | 11 | 28.9 | 3 | 13.6 | 7 | 14.9 |

| Outlet | N = 35 | N = 15 | N = 25 | N = 30 | N = 20 | N = 21 | N = 52 | |||||||

| Outlet had ACT in stock | 28 | 80.0 | 13 | 86.7 | 23 | 92.0 | 17 | 56.7 | 14 | 70.0 | 21 | 100.0 | 38 | 73.1 |

| Outlet receives antimalarials from drug company representativea | – | – | 1 | 4.0 | 2 | 6.7 | – | 12 | 57.1 | 9 | 17.3 | |||

| Urban/rural community | ||||||||||||||

| Urban | 13 | 37.1 | 9 | 60.0 | 24 | 96.0 | 17 | 56.7 | 12 | 60.0 | 20 | 95.2 | 31 | 59.6 |

| Rural | 22 | 62.9 | 6 | 40.0 | 1 | 4.0 | 13 | 43.3 | 8 | 40.0 | 1 | 4.8 | 21 | 40.4 |

aSome observations were missing (see Table 1).

bCategories differ by country. In Cameroon: Doctor; Nurse or Midwife; Pharmacist; Nurse Assistant; None (includes attendants). In Nigeria: Doctor; Nurse or Midwife; Pharmacist; Community Health Officer (CHO) or Community Health Extension Worker (CHEW); None (includes patent medicine dealers).

The characteristics of febrile patients who relied on the provider to select treatment and were supplied an antimalarial are shown in Table 3. The proportions by gender and age group were similar across the different types of outlet in Cameroon, though in Nigeria proportionately more children under five were treated at public facilities than at pharmacies and drug stores. In both countries, there was some variation in the education level of the person seeking treatment and household wealth, with individuals at pharmacies having higher levels of education and from wealthier quintiles. There were also notable differences in the patient–provider interaction, as patients at public and mission health facilities were more frequently examined. Presumptive diagnosis of malaria was the norm in all outlets, though 23% of patients at public and mission facilities in Cameroon had their malaria diagnosis confirmed by microscopy.

Table 3.

Patient Attributes by country and type of outlet

| Patient attributes | Cameroon (N = 405) |

Nigeria (N = 641) |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public |

Mission |

Pharmacy |

Drug store |

Public |

Pharmacy |

Drug store |

||||||||

| N | N | N | N | N | N | N | ||||||||

| N = 202 | N = 80 | N = 52 | N = 71 | N = 323 | N = 60 | N = 258 | ||||||||

| Patient’s gendera | ||||||||||||||

| Male | 100 | 49.5 | 33 | 41.3 | 27 | 51.9 | 32 | 45.1 | 141 | 43.7 | 32 | 53.3 | 129 | 50.0 |

| Female | 100 | 49.5 | 45 | 56.3 | 25 | 48.1 | 38 | 53.5 | 179 | 55.4 | 27 | 45.0 | 126 | 48.8 |

| Patient’s age groupa | ||||||||||||||

| Under 5 years | 61 | 30.2 | 19 | 23.8 | 15 | 28.8 | 16 | 22.5 | 122 | 37.8 | 7 | 11.7 | 32 | 12.4 |

| 5 years and over | 136 | 67.3 | 61 | 76.3 | 37 | 71.2 | 55 | 77.5 | 199 | 61.6 | 53 | 88.3 | 223 | 86.4 |

| Education of person who sought treatmenta | ||||||||||||||

| Tertiary | 15 | 7.4 | 14 | 17.5 | 18 | 34.6 | 8 | 11.3 | 67 | 20.7 | 28 | 46.7 | 54 | 20.9 |

| Secondary | 86 | 42.6 | 29 | 36.3 | 22 | 42.3 | 29 | 40.8 | 150 | 46.4 | 26 | 43.3 | 119 | 46.1 |

| None or primary | 98 | 48.5 | 37 | 46.3 | 11 | 21.2 | 33 | 46.5 | 93 | 28.8 | 5 | 8.3 | 80 | 31.0 |

| Patients’ wealth quintile (relative to other patients) | ||||||||||||||

| Least poor | 21 | 10.4 | 9 | 11.3 | 19 | 36.5 | 5 | 7.0 | 46 | 14.2 | 19 | 31.7 | 25 | 9.7 |

| Fourth | 24 | 11.9 | 21 | 26.3 | 12 | 23.1 | 9 | 12.7 | 48 | 14.9 | 18 | 30.0 | 50 | 19.4 |

| Third | 40 | 19.8 | 18 | 22.5 | 11 | 21.2 | 13 | 18.3 | 72 | 22.3 | 9 | 15.0 | 55 | 21.3 |

| Second | 44 | 21.8 | 13 | 16.3 | 7 | 13.5 | 26 | 36.6 | 82 | 25.4 | 11 | 18.3 | 56 | 21.7 |

| Poorest | 73 | 36.1 | 19 | 23.8 | 3 | 5.8 | 18 | 25.4 | 75 | 23.2 | 3 | 5.0 | 72 | 27.9 |

| Treatment was sought within 2 days | 69 | 34.2 | 24 | 30.0 | 32 | 61.5 | 36 | 50.7 | 131 | 40.6 | 40 | 66.7 | 164 | 63.6 |

| First time treatment was sought | 125 | 61.9 | 39 | 48.8 | 39 | 75.0 | 57 | 80.3 | 220 | 68.1 | 48 | 80.0 | 194 | 75.2 |

| Patient had previously taken an antimalarial | 19 | 9.4 | 20 | 25.0 | 6 | 11.5 | 4 | 5.6 | 34 | 10.5 | 4 | 6.7 | 14 | 5.4 |

| Provider was told patient had diarrhoea or been vomiting | 27 | 13.4 | 14 | 17.5 | 4 | 7.7 | 3 | 4.2 | 70 | 21.7 | 13 | 21.7 | 41 | 15.9 |

| Patient was examined by provider | 175 | 86.6 | 73 | 91.3 | 14 | 26.9 | 21 | 29.6 | 228 | 70.6 | 7 | 11.7 | 39 | 15.1 |

| Patient reported malaria was confirmed | 47 | 23.3 | 18 | 22.5 | 2 | 3.8 | – | – | 16 | 5.0 | – | – | – | – |

aSome observations were missing (see Table 1).

Factors influencing the providers’ decision to supply ACT

The relationship between providers’ knowledge of the malaria treatment guidelines and their decision to supply ACT was examined in Cameroon and in Nigeria using univariable and multivariable models (Tables 4 and 5). Analysis was conducted using complete cases and once missing data had been imputed. The specification of the multivariable models was assessed: the results for Ramsey RESET tests were not significant and there was no evidence of multicollinearity. The variable for providers’ stated preference was included in the final model since there was no evidence of simultaneity bias. Also likelihood ratio tests indicated model fit was significantly better when providers’ stated preference was included. Multivariable models without the variable for providers’ stated preference are available (Supplementary Tables Appendices S2 and S3).

Table 4.

Factors associated with providers’ decision to supply ACT in Cameroon

| Complete cases |

Multiple imputation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 304 | 281 | 405 | 405 | ||||

| Number of outlets | 91 |

84 |

105 |

105 |

||||

| Fixed effects | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Level 1: Patient–provider interaction | ||||||||

| Provider knew ACT is first-line antimalarial for uncomplicated malaria | 0.84 (0.33–2.13) | 0.709 | 0.39 (0.11–1.35) | 0.138 | 0.61 (0.28–1.33) | 0.216 | 0.39 (0.14–1.08) | 0.070 |

| Provider had access to malaria guidelines | 0.59 (0.20–1.80) | 0.354 | 1.00 (0.37–2.70) | 0.992 | ||||

| Provider had attended malaria training in past 3 years | 1.31 (0.46–3.74) | 0.608 | 1.73 (0.63–4.76) | 0.289 | ||||

| Provider’s pre-service | ||||||||

| Doctor | 0.91 (0.17–5.02) | 0.458 | 2.78 (0.53–14.46) | 0.092 | ||||

| Nurse/midwife | 0.41 (0.10–1.72) | 1.06 (0.26–4.36) | ||||||

| Pharmacist | 0.53 (0.03–9.36) | 0.21 (0.03–1.65) | ||||||

| Nurse assistant | 1.32 (0.33–5.28) | 2.90 (0.70–11.98) | ||||||

| None (attendant/drug seller) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Provider stated patients usually ask for ACT | 2.60 (0.92–7.31) | 0.070 | 2.36 (0.92–6.06) | 0.075 | ||||

| Provider stated ACT was best antimalarial for uncomplicated malaria | 3.55 (1.28–9.88) | 0.015 | 2.80 (1.14–6.89) | 0.025 | ||||

| Patient was male | 1.00 (0.47–2.12) | 0.996 | 1.06 (0.56–1.99) | 0.856 | ||||

| Patient was under 5 years of age | 1.87 (0.72–4.77) | 0.191 | 1.45 (0.67–3.13) | 0.345 | ||||

| Education of person seeking treatment | ||||||||

| Tertiary | 0.42 (0.10–1.87) | 0.490 | 0.67 (0.21–2.19) | 0.733 | ||||

| Secondary | 0.68 (0.27–1.70) | 0.77 (0.36–1.65) | ||||||

| None or primary | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Patient’s wealth quintile | ||||||||

| Least Poor | 3.63 (0.68–19.51) | 0.279 | 2.62 (0.64–10.71) | 0.048 | ||||

| Fourth | 6.31 (1.23–32.20) | 6.46 (1.73–24.13) | ||||||

| Third | 1.77 (0.53–5.86) | 1.63 (0.58–4.60) | ||||||

| Second | 1.68 (0.63–4.50) | 1.10 (0.45–2.69) | ||||||

| Poorest | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Treatment was sought within 2 days | 1.22 (0.53–2.82) | 0.635 | 1.02 (0.51–2.05) | 0.956 | ||||

| First time treatment was sought | 0.24 (0.07–0.79) | 0.019 | 0.41 (0.17–1.02) | 0.056 | ||||

| Patient had previously taken an antimalarial | 0.08 (0.02–0.39) | 0.002 | 0.22 (0.07–0.64) | 0.005 | ||||

| Provider was told patient has diarrhoea or been vomiting | 1.07 (0.33–3.47) | 0.908 | 0.77 (0.28–2.08) | 0.603 | ||||

| Patient was examined by provider | 0.90 (0.33–2.45) | 0.839 | 1.08 (0.43–2.72) | 0.872 | ||||

| Patient had a confirmed malaria diagnosis | 0.33 (0.12–0.91) | 0.032 | 0.31 (0.13–0.74) | 0.008 | ||||

| Level 2: Outlet | ||||||||

| Type of outlet | ||||||||

| Public | 22.46 (3.86–130.69) | 0.002 | 7.38 (1.53–35.57) | <0.001 | ||||

| Mission | 7.69 (1.16–50.80) | 2.23 (0.45–11.08) | ||||||

| Pharmacy | 72.63 (3.84–1372.3) | 203.38 (13.10–3156.3) | ||||||

| Drug store | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Outlet had ACT in stock | 1.85 (0.67–5.13) | 0.238 | 2.15 (0.74–6.26) | 0.160 | ||||

| Outlet usually receives antimalarial from drug company representative | 1.75 (0.15–19.81) | 0.650 | 1.43 (0.10–20.52) | 0.791 | ||||

| Outlet was in an urban community | 0.69 (0.25–1.88) | 0.470 | 0.70 (0.26–1.87) | 0.481 | ||||

| Constant | 4.16 (1.76–9.87) | 0.001 | 0.73 (0.10–5.18) | 0.753 | 5.47 (2.63–11.37) | <0.001 | 0.38 (0.06–2.32) | 0.296 |

| Random effects | ||||||||

| Residual SD | 1.42 (0.91–2.21) | 0.77 (0.23–2.58) | 1.37 (0.92–2.04) | 1.12 (0.67–1.86) | ||||

| VPC | 0.38 | 0.15 | 0.36 | 0.28 | ||||

SD, Standard Deviation.

Table 5.

Factors associated with providers’ decision to supply ACT in Nigeria

| Complete cases |

Multiple imputation |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 473 | 423 | 641 | 641 | ||||

| Number of outlets | 73 |

71 |

93 |

93 |

||||

| Fixed effects | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value |

| Level 1: patient–provider interaction | ||||||||

| Provider knew ACT is first-line antimalarial for uncomplicated malaria | 1.66 (0.70–3.90) | 0.247 | 1.08 (0.44–2.66) | 0.869 | 1.69 (0.76–3.75) | 0.196 | 1.08 (0.50–2.33) | 0.851 |

| Provider had access to malaria guidelines | 0.83 (0.25–2.76) | 0.761 | 1.54 (0.57–4.18) | 0.392 | ||||

| Provider had attended malaria training in past 3 years | 0.66 (0.29–1.49) | 0.316 | 0.69 (0.33–1.46) | 0.332 | ||||

| Provider’s pre-service training | ||||||||

| Doctor or nurse/midwife or pharmacista | 2.18 (0.39–12.22) | 0.453 | 1.75 (0.41–7.48) | 0.717 | ||||

| CHO or CHEW | 2.66 (0.58–12.16) | 1.62 (0.41–6.34) | ||||||

| None (attendant/drug seller) | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Provider stated patients usually ask for ACT | 1.41 (0.29–1.49) | 0.458 | 1.38 (0.62–3.07) | 0.429 | ||||

| Provider stated ACT was best antimalarial for uncomplicated malaria | 2.54 (0.92–7.00) | 0.071 | 2.54 (1.02–6.32) | 0.044 | ||||

| Patient was male | 1.61 (0.92–2.82) | 0.093 | 1.85 (1.19–2.89) | 0.007 | ||||

| Patient was under 5 years of age | 3.84 (1.91–7.73) | <0.001 | 2.67 (1.54–4.63) | <0.001 | ||||

| Education of person seeking treatment | ||||||||

| Tertiary | 0.91 (0.37–2.26) | 0.903 | 1.37 (0.67–2.78) | 0.643 | ||||

| Secondary | 0.84 (0.39–1.80) | 1.08 (0.60–1.96) | ||||||

| None or primary | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Patient’s wealth quintile | ||||||||

| Least Poor | 1.35 (0.40–4.62) | 0.951 | 1.39 (0.54–3.60) | 0.962 | ||||

| Fourth | 1.40 (0.43–4.58) | 1.32 (0.54–3.25) | ||||||

| Third | 1.57 (0.52–4.80) | 1.30 (0.55–3.09) | ||||||

| Second | 1.36 (0.64–3.45) | 1.30 (0.62–2.73) | ||||||

| Poorest | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Treatment was sought within 2 days | 1.75 (0.91–3.39) | 0.095 | 1.45 (0.87–2.40) | 0.151 | ||||

| First time treatment was sought | 0.56 (0.25–1.25) | 0.155 | 0.49 (0.26–0.90) | 0.023 | ||||

| Patient had previously taken an antimalarial | 1.80 (0.59–5.51) | 0.300 | 1.01 (0.43–2.41) | 0.976 | ||||

| Provider was told patient has diarrhoea or been vomiting | 2.39 (1.18–4.82) | 0.015 | 2.36 (1.38–4.04) | 0.002 | ||||

| Patient was examined by provider | 1.06 (0.49–2.27) | 0.885 | 1.29 (0.71–2.35) | 0.408 | ||||

| Patient had a confirmed malaria diagnosis | 0.06 (0.00–0.79) | 0.033 | 0.23 (0.05–1.04) | 0.057 | ||||

| Level 2: outlet | ||||||||

| Type of outlet | ||||||||

| Public | 2.83 (0.51–15.80) | 0.380 | 2.22 (0.50–9.94) | 0.558 | ||||

| Pharmacy | 0.78 (0.13–4.51) | 1.25 (0.36–4.33) | ||||||

| Drug store | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Outlet had ACT in stock | 3.24 (1.05–9.96) | 0.040 | 3.25 (1.30–8.14) | 0.012 | ||||

| Outlet usually receives antimalarial from drug company representative | 1.93 (0.44–8.55) | 0.386 | 1.04 (0.34–3.14) | 0.947 | ||||

| Outlet was in an urban community | 1.70 (0.50–5.72) | 0.393 | 1.49 (0.54–4.09) | 0.442 | ||||

| Constant | 0.21 (0.10–0.46) | <0.001 | 0.01 (0.00–0.06) | <0.001 | 0.23 (0.12–0.45) | <0.001 | 0.02 (0.00–0.06) | <0.001 |

| Random effects | ||||||||

| Residual SD | 1.73 (1.23–2.42) | 1.06 (0.65–1.73) | 1.68 (1.25–2.25) | 0.99 (0.66–1.48) | ||||

| VPC | 0.48 | 0.26 | 0.46 | 0.23 | ||||

aCategories were grouped for the analysis since there were few observations in each category and all these grades have received formal pre-service training.

There was no evidence of a relationship between providers’ knowledge and practice in the univariable analysis in either Cameroon or Nigeria. However, the multivariable models identified several attributes of providers, patients and outlets that were significant predictors of providers supplying an ACT (at the 10% level of significance). Providers in both countries were more than twice as likely to supply ACT if they reported ACT was the best type of antimalarial for uncomplicated malaria (Odds ratio (OR) = 2.80, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.14–6.89, P = 0.025 in Cameroon and OR = 2.54, 95% CI = 1.02–6.32, P = 0.044 in Nigeria). In Nigeria, this was the only provider attribute that had a significant effect. In Cameroon, however, there was also evidence that providers were more likely to select ACT if they had reported it was the type of antimalarial that their patients most often request (OR = 2.36, 95% CI = 0.92–6.06, P = 0.075). In addition, once missing data had been imputed the results suggest that pre-service training may have some bearing on their choice (P = 0.092), and knowledge of the malaria treatment guidelines may adversely affect their decision to supply an ACT (OR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.14–1.08, P = 0.070).

Providers’ choice of antimalarial was related to several patient attributes, though there were notable differences between the two countries. In Cameroon, providers were less likely to supply an ACT if the patient had previously taken an antimalarial (OR = 0.22, 95% CI = 0.17–0.64, P = 0.005) or had their diagnosis confirmed using microscopy (OR = 0.031, 95% CI = 0.13–0.74, P = 0.008). Also, once missing data had been imputed there was also some evidence that those from wealthier quintiles were more likely to receive an ACT (P = 0.048). In Nigeria, there was strong evidence that providers were more likely to supply ACT to patients under 5 years of age (OR = 2.67, 95% CI = 1.54–4.63, P ≤ 0.001) and to male patients (OR = 1.85, 95% CI = 1.19–2.89, P = 0.007), though wealth was not significant. The results also indicate that providers in Nigeria were more likely to supply ACT when told the patient had diarrhoea or had been vomiting (OR = 2.36, 95% CI = 1.38–4.04, P = 0.002), though less likely to supply an ACT if it was the first time treatment was sought for the illness episode (OR = 0.49, 95% CI = 0.26–0.90, P = 0.023). As in Cameroon, patients with a confirmed malaria diagnosis were less likely to receive an ACT (OR = 0.23, 95% CI = 0.05–1.04, P = 0.057); however, it is important to recognize that only 2% of all patients in Nigeria had their diagnosis confirmed by a malaria test.

In both countries, providers’ decision to supply an ACT was correlated with attributes of the outlet. In Cameroon, patients were more likely to receive an ACT if treatment was sought at a pharmacy or public facility (P < 0.001), while in Nigeria providers were three times more likely to supply ACT if it was in stock (OR = 3.25, 95% CI = 1.30–8.14, P = 0.012). Finally, having controlled for a wide range of provider, outlet and patient attributes, the VPC indicates that a substantial proportion of the remaining heterogeneity can be attributed to unobserved outlet-level factors.

Discussion

The analysis focused on the relationship between providers’ knowledge and practice, and was motivated by a need to design interventions to support the introduction of malaria RDTs in Cameroon and Nigeria. There was no evidence from either country that a provider’s decision to supply ACT was determined by their knowledge of the national malaria treatment guidelines. There was, however, significant evidence from both countries that providers were more likely to supply ACT if they reported it was the best treatment for uncomplicated malaria (Cameroon OR = 2.80, 95% CI = 1.14–6.89, P = 0.025; Nigeria OR = 2.54 95% CI = 1.02–6.32, P = 0.044). This positive association between providers’ stated and revealed preferences highlights the importance of designing interventions that strive to change what providers think and believe to be appropriate, not only enhance what they know.

The results also showed that having access to a copy of the clinical guidelines and access to malaria training was not sufficient to ensure appropriate treatment. This also demonstrates that conventional methods to disseminate clinical guidelines are likely to have a limited effect on providers’ practice in the study sites. Evidence from similar studies at public and mission facilities elsewhere in Africa have mixed results: prescribing practices were predicted by the providers’ access to in-service training, guidelines or wall charts in Benin and Kenya (Rowe et al. 2003; Zurovac et al. 2004, 2008a), though not in Central African Republic, Malawi, Uganda and Zambia, (Rowe et al. 2000, 2003; Zurovac et al. 2005, 2008b; Osterholt et al. 2006.).

There was evidence from both countries that providers’ choice of treatment can depend on their patients, though which factors were statistically significant differed by setting. It was interesting to find providers in Cameroon who reported their patients prefer ACT were more likely to supply it. There was also evidence to suggest the relative wealth of the patient may be a predictor of receiving an ACT. These findings were consistent with views expressed during focus group discussions, in which providers from public and mission facilities in the Cameroon study sites explained how their practice would depend on what they perceive their patients want from the consultation and can afford (Chandler et al. 2012).

Patient attributes were also relevant in Nigeria, where providers’ decision to supply ACT was significantly associated with the patient’s age and gender. Age was also found to be a significant predictor in other studies, with providers more likely to supply ACT to children than adults (Zurovac et al. 2008a,b). In-depth interviews conducted at public health centres in Kenya described how providers who were concerned about stock-outs would reserve ACT for young children and patients with more severe symptoms (Wasunna et al. 2008). In contrast to similar studies, gender was shown to be an important predictor of the treatment supplied and further research on this would be valuable. Although we cannot comment on the relative severity of febrile illness among the patients in our sample, it was intriguing to find providers were less likely to supply ACT to patients seeking treatment for the first time or with a confirmed diagnosis. Given the small number of patients that reported having a positive malaria test, we are cautious about drawing conclusions on the choice of antimalarial following a confirmed diagnosis, though note that the test-positive patients not supplied ACT were treated with an antimalarial recommended for severe malaria, and these cases were clustered in 14 public and mission facilities in Cameroon and 3 public facilities in Nigeria. We were also unable to investigate whether timing or length of the consultation were important, which were significant predictors some studies (Rowe et al. 2003; Zurovac et al. 2004, 2005; Osterholt et al. 2006).

Contextual factors were also associated with providers’ practice, and as there were substantial differences between the two countries, the findings highlight the importance of understanding the local context when designing public health interventions. It was not surprising that providers were more likely to supply ACT if it was in stock, though having ACT available was not a prerequisite and providers could prescribe ACT and advise it should be obtained elsewhere. It should also be noted that the exit survey would not have captured any cases where the provider recommended ACT and the patient or caregiver opted for an alternative. Furthermore, given the extent to which variation in providers’ practice was attributed to unobserved outlet-level factors, it would be interesting to conduct further research to explore how the institutional environment can influence providers’ practice.

Before concluding some limitations are acknowledged. While several factors significantly predicted whether a provider supplied an ACT, it is possible others were not identified because the sample size was restricted to a subset of exit survey respondents who did not request a specific medicine, had a presumptive or confirmed malaria diagnosis, and were supplied an antimalarial. Also, two assumptions were made to prepare the data for analysis: the more senior cadre selected treatment if patients were seen by more than one provider, and data were MAR. The first assumption was based on the process of care that we observed at many health outlets: junior staff record signs and symptoms and direct patients to the relevant senior health worker for a consultation, treatment is prescribed during the consultation, and prescribed medicines are obtained from a pharmacy attendant. At pharmacies and drug stores the process is less structured, though where a pharmacist and a sales attendant were involved we observed the pharmacist giving advice and recommending medicines, while the attendant administered the retail transaction. The second assumption that data were MAR was critical to the multiple imputation. The observed pattern of missingness was consistent with our expectation that provider attributes were more likely to be missing at larger outlets and in urban communities. We acknowledge, however, that it is not possible to determine whether data were MAR, as defined in the statistical literature (White et al. 2011). Similarly, since the missing data can never be known, we cannot ascertain whether differences between the complete case and multiple imputation results, such as those observed in Cameroon for the effect of pre-service training and knowledge, arise because the complete cases are biased, because multiple imputation depends on the MAR assumption, or because of the specification of the imputation model (White et al. 2011).

Conclusions

As governments prepare to introduce malaria RDTs in public and private sectors, clinical guidelines will be updated to include guidance on the new type of diagnostic test and dissemination strategies will be developed. The introduction of RDTs, with revised guidelines, presents an opportunity to improve providers’ practice, not only by increasing the proportion of patients that are tested prior to treatment, but also the proportion of patients that receive the recommended treatment. The results of this investigation suggest that conventional public health interventions that ensure providers have access to the guidelines, and know the treatment algorithm will not be enough to change providers’ practice. The findings highlight that public health interventions to improve the treatment of uncomplicated malaria should strive to change what providers prefer, rather than focus on what they know. In developing interventions, the differences between the two countries highlight the need to understand the local context, as providers’ treatment decisions may depend on what they perceive their patients prefer or can afford as well as information about their symptoms or previous treatment seeking. In addition, the findings suggest it will be important to emphasize that the treatment algorithm should not depend on patient attributes, such as age or wealth, and that ACT is suitable for patients with a confirmed malaria diagnosis, unless they have symptoms of severe malaria or are pregnant. Finally, it should be recognized that working environment can constrain providers’ practice, and providers can only adhere to clinical guidelines if essential medicines and supplies are available.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at HEAPOL online.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all patients and providers who participated in this study and colleagues involved in survey design and implementation.

Funding

The research was supported by the ACT Consortium, which is funded through a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- Arrow K. Uncertainty and the welfare economics of medical care. American Economic Review. 1963;53:941–71. [Google Scholar]

- Burton A, Altman D. Missing covariate data within cancer prognostic studies: a review of current reporting and proposed guidelines. British Journal of Cancer. 2004;91:4–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabana M, Rand C, Rowe N, et al. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282:1458–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.15.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter J, Goldstein H, Kenward M. REALCOM-IMPUTE software for multilevel multiple imputation with mixed response types. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45:5. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter J, Kenward M. Multiple Imputation and its Application. Chichester: Wiley; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler C, Mangham L, Njei A, et al. ‘As a clinician, you are not managing lab results, you are managing the patient’: How the enactment of malaria at health facilities in Cameroon compares with new WHO guidelines for the use of malaria tests. Social Science & Medicine, 2012;74:1528–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das J, Hammer J, Leonard K. The quality of medical advice in low-income countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2008;22:93–114. doi: 10.1257/jep.22.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Lohr K IOM Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Guidelines for Clinical Practice: From Development to Use. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H, Carpenter J, Kenward M, Levin K. Multilevel models with multivariate mixed response types. Statistical Modelling. 2009;9:173–97. [Google Scholar]

- Grol R, Grimshaw J. From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet. 2003;362:1225–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox J. Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications. New York: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes R, Chandler C, Mangham L, Mbacham W. Providing health care in northeast Cameroon: perspectives of medicine sellers. Health Policy and Planning. 2013;28:636–646. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A. Applied Econometrics for Health Economists. A Practical Guide. 2nd. Oxford: Office of Health Economics; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard K, Masatu M. Using the Hawthorne effect to examine the gap between a doctor's best possible practice and actual performance. Journal of Development Economics. 2010;93:226–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lubell Y, Reyburn H, Mbakilwa H, et al. The impact of response to the results of diagnostic tests for malaria: cost-benefit analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:202–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39395.696065.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangham L, Cundill B, Ezeoke O, et al. Treatment of uncomplicated malaria at public health facilities and medicine retailers in south-eastern Nigeria. Malaria Journal, 2011;10:155. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangham L, Cundill B, Achonduh O, et al. Malaria prevalence and treatment of febrile patients attending health facilities in Cameroon. Tropical Medicine and International Health, 2012;17:330–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health of the Federal Republic of Nigeria. National Antimalarial Treatment Policy. Abuja: Ministry of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Public Health of the Republic of Cameroon. Guidelines for the Management of Malaria in Cameroon. Yaounde: Ministry of Public Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Osterholt D, Rowe A, Hamel M, et al. Predictors of treatment error for children with uncomplicated malaria seen as outpatients in Blantyre district, Malawi. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2006;11:1147–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01666.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabin M. Pscyhology and economics. Journal of Economic Literature. 1998;36:11–46. [Google Scholar]

- Rice N. Binomial Regression. In: Leyland A, Goldstein H, editors. Multilevel Modelling of Health Statistics. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe A, Hamel M, Flanders D, et al. Predictors of correct treatment of children with fever seen at outpatient health facilities in the Central African Republic. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;151:1029–91. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe A, Onikpo F, Lama M, Deming M. Risk and protective factors for two types of error in the treatment of children with fever at outpatient health facilities in Benin. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;32:296–303. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith L, Jones C, Meek S, Webster J. Review: provider practice and user behavior interventions to improve prompt and effective treatment of malaria: do we know what works? American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2009;80:326–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Longitudinal-Data/Panel-Data Reference Manual Release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne J, White I, Carlin JB, et al. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009;338:b2393. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uzochukwu B, Onwujekwe O, Soludo E, Nkoli E, Uguru N. The District Health System in Enugu State, Nigeria: An Analysis of Policy Development and Implementation. Enugu, Nigeria: Consortium for Research on Equitable Health Systems; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren S. Multiple Imputation of Multilevel Models. In: Hox J, Roberts J, editors. Handbook of Advanced Multivel Analysis. New York: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wasunna B, Zurovac D, Goodman C, Snow R. Why don’t health workers prescribe ACT? A qualitative study of factors affecting the prescription of artemether-lumefantrine. Malaria Journal. 2008;7:53. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White I, Carlin J. Bias and efficiency of multiple imputation compared with complete-case analysis for missing covariate values. Statistics in Medicine. 2010;29:2920–31. doi: 10.1002/sim.3944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White I, Royston P, Wood A. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Statistics in Medicine. 2011;30:377–99. doi: 10.1002/sim.4067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson O. The New Institutional Economics: taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature. 2000;38:595–613. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman V, Ezeoke O, Nwala E, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of provider and community interventions to improve the treatment of uncomplicated malaria in Nigeria: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012a;13:81. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman V, Mangham L, Cundill B, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of provider interventions to improve health worker practice in providing treatment for uncomplicated malaria in Cameroon: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012b;13:4. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf S, Schunemann H, Eccles M, Grimshaw J, Shekelle P. Developing clinical practice guidelines: types of evidence and outcomes; values and economics, synthesis, grading and presentation and deriving recommendations. Implementation Science. 2012;7:61. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurovac D, Ndhlovu M, Rowe A, et al. Treatment of paediatric malaria during a period of drug transition to artemether-lumefantrine in Zambia: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2005;331:734. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurovac D, Njogu J, Akhwale W, Hamer D, Snow R. Translation of artemether-lumefantrine treatment policy into paediatric clinical practice: an early experience from Kenya. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2008a;13:99–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01980.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurovac D, Rowe A, Ochola S, et al. Predictors of the quality of health worker treatment practices for uncomplicated malaria at government health facilities in Kenya. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;33:1080–91. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurovac D, Tibenderana J, Nankabirwa J, et al. Malaria case-management under artemether-lumefantrine treatment policy in Uganda. Malaria Journal. 2008b;7:181. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.