Summary

Replication stress activates the Mec1ATR and Rad53 kinases. Rad53 phosphorylates nuclear pores to counteract gene gating, thus preventing aberrant transitions at forks approaching transcribed genes. Here, we show that Rrm3 and Pif1, DNA helicases assisting fork progression across pausing sites, are detrimental in rad53 mutants experiencing replication stress. Rrm3 and Pif1 ablations rescue cell lethality, chromosome fragmentation, replisome-fork dissociation, fork reversal, and processing in rad53 cells. Through phosphorylation, Rad53 regulates Rrm3 and Pif1; phospho-mimicking rrm3 mutants ameliorate rad53 phenotypes following replication stress without affecting replication across pausing elements under normal conditions. Hence, the Mec1-Rad53 axis protects fork stability by regulating nuclear pores and DNA helicases. We propose that following replication stress, forks stall in an asymmetric conformation by inhibiting Rrm3 and Pif1, thus impeding lagging strand extension and preventing fork reversal; conversely, under unperturbed conditions, the peculiar conformation of forks encountering pausing sites would depend on active Rrm3 and Pif1.

Graphical Abstract

Highlights

-

•

Rrm3 and Pif1 promote fork reversal and ssDNA gaps at stalled forks in rad53 cells

-

•

Rrm3 and Pif1 associate with stalled DNA replication forks

-

•

Rad53 phosphorylates Rrm3 and Pif1 at stalled forks

-

•

Rrm3 and Pif1 promote chromosome fragility in hydroxyurea-treated rad53 cells

Rossi et al. show that the DNA helicases Rrm3 and Pif1 associate with stalled DNA replication forks and undergo Rad53-mediated phosphorylation. The authors suggest that Rrm3 and Pif1 promote fork reversal, fork stalling, and chromosome fragility in rad53 defective cells under replication stress.

Introduction

Replication forks pause at specific sites under unperturbed conditions (Deshpande and Newlon, 1996). Fork stalling occurs in response to intra-S DNA damage or DNA synthesis inhibition. Hydroxyurea (HU) causes deoxi-nucleotides triphosphate (dNTPs) deprivation (Krakoff et al., 1968), fork stalling, and activation of the Mec1ATR and Rad53 kinases that protect stalled fork stability (Branzei and Foiani, 2009). The mec1 and rad53 mutants exhibit accumulation of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) and chromosome fragmentation under replication stress (Cha and Kleckner, 2002; Feng et al., 2006; Hashash et al., 2011). rad53 mutants treated with HU undergo fork collapse and accumulation of hemi-replicated, gapped, and reversed forks (Sogo et al., 2002). The Mec1-Rad53 axis has also been implicated in controlling replisome-fork association (Cobb et al., 2005; Lucca et al., 2004) in response to replication stress, although this aspect has been challenged (De Piccoli et al., 2012). Following HU treatments, human Chk1 (with functionally similar to Rad53) prevents aberrant origin firing, apoptosis, and fork processing by the Mus81/Eme1 nuclease and the Rqh1 DNA helicase, which promote chromosome breakages (Doe et al., 2002; Forment et al., 2011; Syljuåsen et al., 2005). In S. pombe, Cds1Rad53 prevents unscheduled Mus81/Eme1-mediated fork processing (Froget et al., 2008) and targets Dna2 to counteract fork reversal (Hu et al., 2012). Downregulation of ATR under replication stress causes fragile site expression (Casper et al., 2002) and chromosome fragmentation through a SMARCAL1/SLX4-dependent process (Couch et al., 2013). It has been found that ATR prevents RPA exhaustion under replication stress to avoid catastrophic events at forks (Toledo et al., 2013). While in the yeasts S. cerevisiae and S. pombe fork reversal has been related to pathological events (Hu et al., 2012; Lopes et al., 2006), studies in mammalian cell lines have suggested that reversed forks may assist replication restart (Berti et al., 2013; Zellweger et al., 2015). The protective role of Rad53 against replication stress relies on its serine/threonine kinase activity (Sun et al., 1996). Following HU treatment, Rad53 increases the dNTP pool by phosphorylating Sml1 and Crt1 (Huang et al., 1998; Zhao and Rothstein, 2002), prevents late origin firing through the phosphorylation of Sld3 and Dbf4 (Zegerman and Diffley, 2010), and counteracts dangerous topological transitions at transcribed loci by phosphorylating the Mlp1 nucleoporin (Bermejo et al., 2011). Pif1 and Rrm3 in S. cerevisiae and Pfh1 in S. pombe are 5′-to-3′-directed DNA helicases, which assist DNA replication fork progression in unperturbed conditions across different pausing elements, such as rDNA, tRNA, telomeres, centromeres, HML/HMR loci, inactive origins, RNA polymerase II (Pol II)-transcribed genes, and G quadruplexes (Bochman et al., 2010; Ivessa et al., 2000, 2003; Paeschke et al., 2011, 2013; Sabouri et al., 2012). Rrm3 removes bulky non-nucleosomal DNA-protein complexes ahead of replication forks while it seems less essential for fork progression across pausing sites containing RNA Pol II-transcribed elements (Azvolinsky et al., 2009; Ivessa et al., 2003). Pif1 unwinds problematic DNA structures (Paeschke et al., 2011, 2013). Pfh1 assists fork progression across pausing elements containing non-nucleosomal DNA-protein complexes and RNA polymerase I-, II-, and III-transcribed elements (Sabouri et al., 2012). Rrm3 moves with the fork in unperturbed conditions and interacts with DNA polymerase ε (Pol ε), PCNA, and Orc5 (Azvolinsky et al., 2006; Matsuda et al., 2007; Schmidt et al., 2002). Pif1 unwinds Okazaki fragments, which cannot be processed by the RAD27/FEN1 endonuclease in the so-called alternative pathway of Okazaki fragment processing, which involves Dna2 (Budd et al., 2006; Pike et al., 2009, 2010; Rossi et al., 2008). Pif1 generates lethal overloads of toxic long 5′ DNA flaps on the lagging strand in dna2 mutants (Budd et al., 2006) and is responsible for unscheduled unwinding activities of uncapped telomeres in cdc13 mutants (Dewar and Lydall, 2010).

Here, we show that Rrm3 and Pif1 associate with stalled forks and undergo Rad53-dependent hyper-phosphorylation under replication stress. Their ablations suppress fork collapse, chromosome fragmentation, and cell lethality in rad53 cells under replication stress. Phospho-mimicking rrm3 alleles alleviate the HU sensitivity of rad53 mutants while they are proficient in assisting fork progression under normal conditions. We propose that Rad53 inhibits Rrm3 and Pif1 by phosphorylation in response to replication stress to prevent fork reversal, chromosome fragmentation, and genome instability.

Results

Rrm3 and Pif1 Associate with Forks following Replication Stress

We used chromatin immunoprecipitation on chip (ChIP-chip) (Bermejo et al., 2009a, 2009b), to investigate whether Rrm3 and Pif1 associated with forks in the presence of HU in a Rad53-dependent manner. We used ssDNA-bromodeoxyuridine immunoprecipitation on chip (BrdU-chip) to visualize DNA synthesis at the genome level (Bermejo et al., 2009b; Katou et al., 2003). All strains used in this study are listed in Table S1.

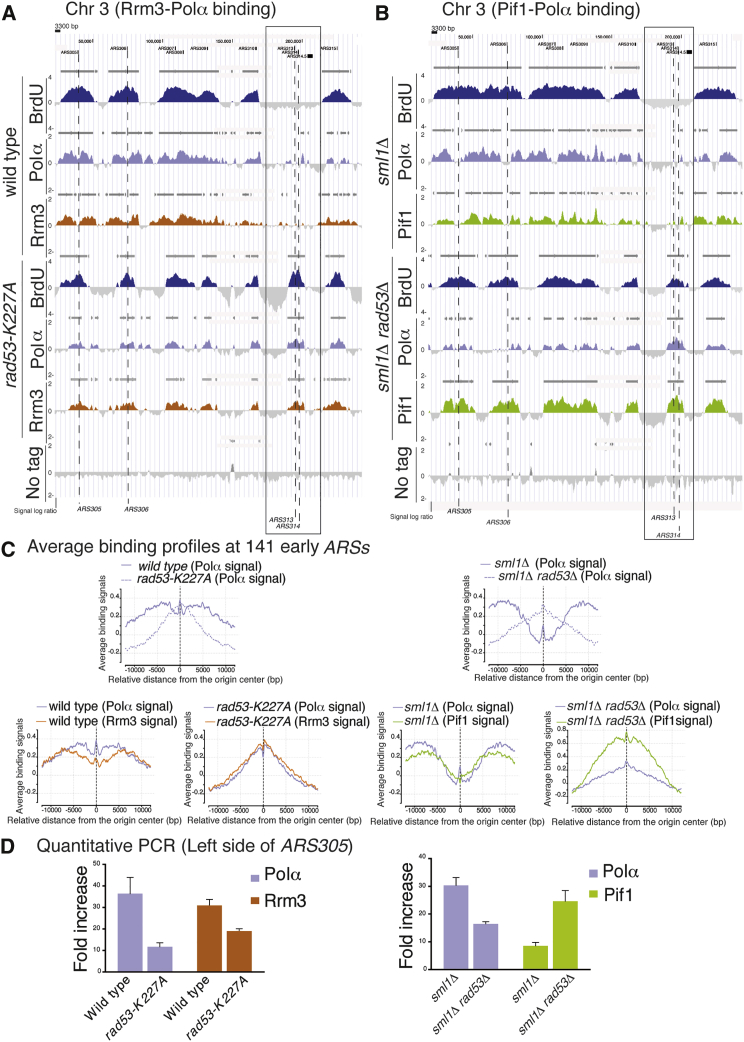

Wild-type (WT) and rad53-K227A strains carrying Rrm3-Myc or Polα-Myc (Figure 1A) and sml1Δ and sml1Δ rad53Δ strains carrying Pif1-FLAG or Polα-FLAG (Figures 1B and S1A) were released from G1 into 150 mM HU for 90 min. The Polα clusters co-localized with the boundaries of the BrdU peaks, generated by forks emanating from active origins (Figures 1A and 1B). The average binding signals of Polα clusters at 141 early ARSs (Figure 1C) showed a bimodal distribution in WT cells due to forks moving away from the origin point; conversely, in rad53 cells, the binding signals were more centered on the origin point due to impaired fork progression. We consistently noticed that the Polα signal intensity was reduced in rad53 mutants compared to WT cells (Figures 1A–1C and S1B). We confirmed this observation by quantitative ChIP-qPCR (Figure 1D). This observation is consistent with what was previously shown (Lucca et al., 2004) and likely reflects the extensive fork collapse, typical of HU-treated rad53 cells (Lopes et al., 2001). Checkpoint mutants exhibit unscheduled firing of late and dormant origins (Santocanale and Diffley, 1998; Shirahige et al., 1998). Specifically, in rad53 mutants, late and dormant origins exhibited Polα clusters, which co-localized with Rrm3 and Pif1 binding sites (Figures 1A, 1B. and S1C). The average signals of Rrm3 and Pif1 clusters at the 141 early ARSs showed that both proteins paralleled the Polα distributions in WT and rad53 cells (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

Rrm3 and Pif1 Associate with the Forks under Replication Stress

(A) Rrm3-13Myc (red) and Polα-9Myc (light blue) binding profiles were determined in strains CY11360, CY12425, CY12927, and CY12698 released from G1 into 150 mM HU for 90 min. Dashed black lines indicate early (ARS305 and ARS306) and dormant (ARS313 and ARS314) origins. Dark gray horizontal bars above the binding profiles indicate the significant binding clusters. A black scale bar indicates the distance corresponding to 3,300 bp on the chromosome III (Chr 3) map.

(B) Same as in (A), with Pif1 (green) and Polα (light blue) binding profiles determined in strains CY13074, CY13073, CY13284, and CY13282.

(A and B) BrdU-chip profiles were determined in strains CY12512, CY12527, CY12488, and CY12493. Statistical analysis of profile overlaps is described in Experimental Procedures. The y axis shows the signal log2 immunoprecipitation (IP)/supernatant ratios, which express enrichments in the IP fractions and are related to the magnitude of protein-DNA bindings or BrdU incorporations in the reported Chr 3 region.

(C) The profiles in the graphs express the average of the ChIP-chip binding signals for the indicated proteins in a window of 24 kb centered on each of the 141 early active DNA replication origins in the indicated genetic backgrounds (see Experimental Procedures).

(D) The magnitude of Polα, Rrm3, and Pif1 binding was determined in the experiments shown in (A) and (B) by quantitative ChIP-qPCR in the indicated genetic backgrounds on the left side of the ARS305 (see Experimental Procedures).

See also Figure S1.

However, although the intensity of the Rrm3 clusters resembled the one of Polα in rad53 mutants, the intensity of Pif1 clusters was higher in the absence of Rad53. These observations were confirmed by quantitative ChIP-qPCR (Figure 1D) and suggest that Rrm3 progressively dissociates from the forks and that rad53 mutants accumulate Pif1-dependent replication intermediates at stalled forks. The Rrm3 and Pif1 distributions paralleled the ones of Polα at those dormant and late origins, which specifically fired in rad53 cells (Figures 1A, 1B, and S1C).

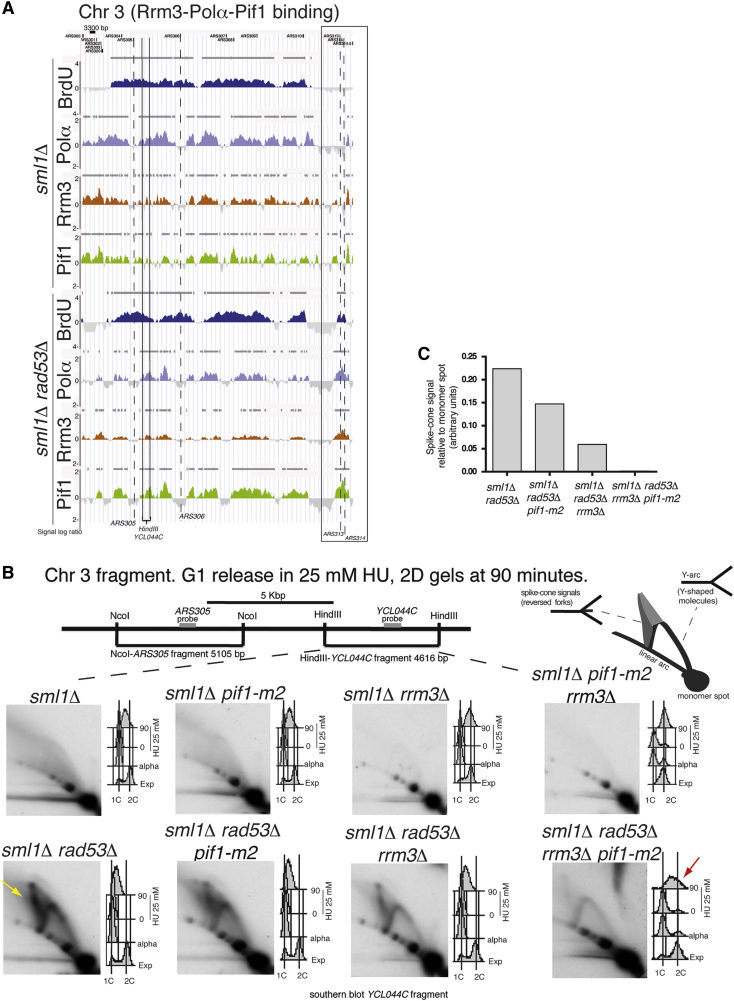

We analyzed the Polα-Flag, Rrm3-Myc, and Pif1-Flag genomic clusters in WT and rad53 mutants treated with 25 mM HU (Figure 2A). Under these conditions, forks in rad53 cells do not collapse soon after origin firing but rather progress further, until they encounter replication risk elements (such as replication slow zones [RSZs]), where they promote fragile site expression (Cha and Kleckner, 2002; Hashash et al., 2011). The sml1Δ and sml1Δ rad53Δ strains were released from G1 into HU for 45 min (Figure 2A). As expected, the BrdU clusters extended outside the ARS305 locus in both sml1Δ and sml1Δ rad53Δ mutants, but their progression was impaired in rad53 mutants. Moreover, the dormant origins ARS313 and ARS314 specifically fired in rad53 but not in WT cells (Figure 2A). While in sml1 cells the Rrm3-Myc, Pif1-Flag, and Polα-Flag clusters, originating from the right forks of ARS305, almost completely passed through the HindIII-YCL044C flanking locus (positioned around 5 kb from the ARS305 origin), in sml1Δ rad53Δ, most forks were still localized within the YCL044C-containing fragment (Figure 2A). Hence, Rrm3 and Pif1 remained associated to the slow-moving forks, typical of rad53 mutants treated with low HU concentrations.

Figure 2.

Fork Abnormalities in rad53 Mutants Treated with HU Depend on Rrm3 and Pif1

(A) Polα-Flag (light blue), Rrm3-13Myc (red), and Pif1-Flag (green) binding profiles were determined in strains CY13284, CY13282, CY12470, CY12422, CY13074, and CY13073 following release from G1 into 25 mM HU for 45 min. BrdU-chip profiles were determined in strains CY12488 and CY12493. Dashed black lines and gray bars indicate origins and significant clusters, respectively, as in Figure 1A. The position of the HindIII-YCL044C restriction fragment is shown on the ChIP-chip maps. Chr 3, chromosome III.

(B) 2D gel analysis after in vivo psoralen crosslinking on the HindIII-YCL044C fragment in strains CY12445, CY13331, CY12448, CY13334, CY12443, CY13339, CY12460, and CY13342, released from G1 into 25 mM HU for 90 min. FACS profiles showing the cellular DNA content during the experiments and schematic representation of the 2D signals are shown. The yellow arrow indicates the spike or cone signal corresponding to aberrant DNA intermediates accumulating in HU in the absence of RAD53, while the red arrow indicates the cell-cycle progression in the quadruple mutant sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ pif1-m2.

(C) The intensity of the spike or cone signals detected in the 2D gels of (B) was normalized against the intensity of their monomer spots and reported into the histogram (a.u.) for the indicated strains.

See also Figure S2.

Altogether, these observations suggest that, under replication stress, Rrm3 and Pif1 likely associate with the replisome, the fork, or both and that this association is not lost in rad53 mutants.

Fork Abnormalities in rad53 Mutants Depend on Rrm3 and Pif1

We investigated whether Rrm3 and Pif1 influenced the fate of the forks in rad53 cells following replication stress. We ablated RRM3 and the PIF1 nuclear form (by using the pif1-m2 allele, which retains the mitochondrial function of Pif1) (Schulz and Zakian, 1994), in sml1Δ and sml1Δ rad53Δ strains. The two sets of strains—sml1Δ, sml1Δ pif1-m2, sml1Δ rrm3Δ, sml1Δ pif1-m2 rrm3Δ and sml1Δ rad53Δ, sml1Δ rad53Δ pif1-m2, sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ, sml1Δ rad53Δ pif1-m2 rrm3Δ—were released from G1 into 25 mM HU for 90 min and analyzed by neutral-neutral 2D gels after in vivo chromatin psoralen crosslinking (Liberi et al., 2006) (Figure 2B). Under these conditions, the sml1 set of strains reached near-2C DNA content even in the presence of HU. Conversely, within the sml1 rad53 set of strains, only sml1Δ rad53Δ pif1-m2 rrm3Δ cells almost completed replication by 90 min (Figure 2B, red arrow). When we analyzed by 2D gel in the sml1 strains the YCL044C locus 90 min after G1 release, we failed to visualize replication intermediates, as most forks had already passed through that genomic fragment (Figures 2A and 2B). Conversely, sml1Δ rad53Δ cells exhibited a strong signal by 2D gel, characterized by the presence of large Ys, cruciform structures, and a cone signal (Figure 2B, yellow arrow). The cruciform structures and the cone signal have been related to aberrant replication events because of the absence of Rad53 (Lopes et al., 2001). The sml1Δ rad53Δ pif1-m2 and sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ cells showed a reduction of the aberrant structures compared to sml1Δ rad53Δ mutants (Figures 2B and 2C). In sml1Δ rad53Δ pif1-m2 rrm3Δ mutants, not only the replication intermediates were less abundant due to fork movement outside the YCL044C locus, but the relative amount of aberrant structures was reduced compared to sml1Δ rad53Δ cells (Figures 2B and 2C). To confirm this observation, we analyzed early time points in sml1Δ rad53Δ and sml1Δ rad53Δ pif1-m2 rrm3Δ mutants and found that the aberrant fork structures were under-represented throughout the kinetic in the quadruple mutant sml1Δ rad53Δ pif1-m2 rrm3Δ (Figure S2A). Hence, Rrm3 and Pif1 are detrimental to fork movement in rad53 mutants treated with HU. Moreover, in rad53 mutants, the aberrant accumulation of cruciform intermediates and their derivatives migrating in the cone signal (Lopes et al., 2001) depended on Rrm3 and Pif1. Based on these conclusions, the expectation would be that ablation of RRM3 and PIF1 in a rad53 background should restore replisome movement even at higher HU concentrations. We found that in cells released from G1 into 150 mM HU for 60 min, Polα immediately collapsed close to the firing point of ARS305 in rad53 mutants, as shown by the short ChIP-chip clusters, while in sml1Δ rad53Δ pif1-m2 rrm3Δ cells, Polα covered larger genomic regions as a result of replisome movement (Figure S2B).

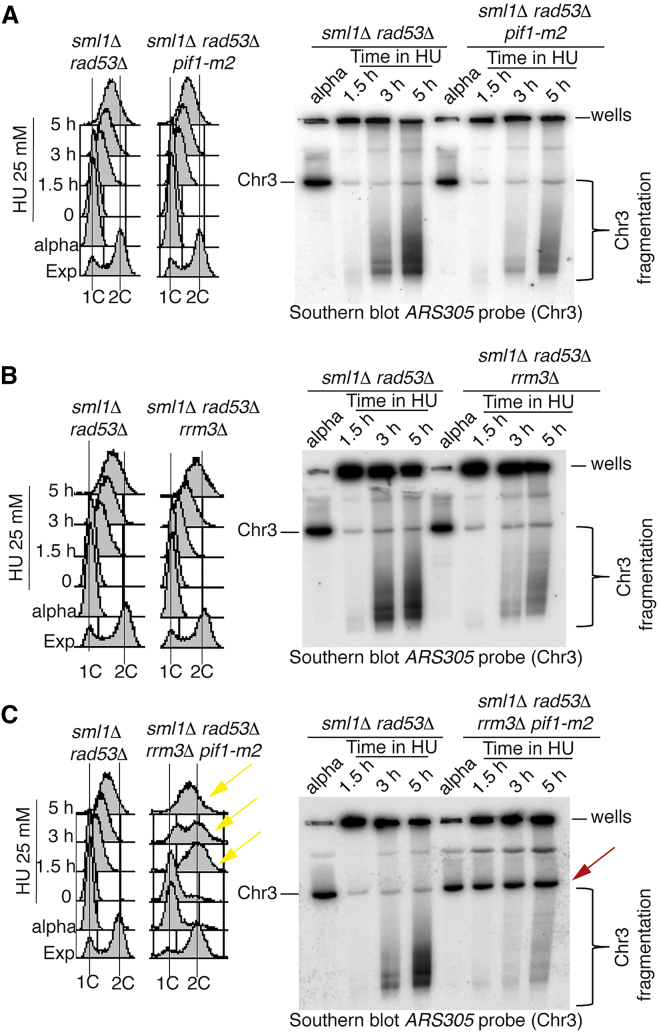

Rrm3 and Pif1 Promote Chromosome Fragility and Cell Lethality in rad53 Mutants Exposed to Replication Stress

In the HU-treated quadruple mutant sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ pif1-m2, the fork defects caused by RAD53 ablation were significantly reduced; therefore, we investigated whether Rrm3, Pif1, or both contributed to the chromosome fragmentation, typical of rad53 cells exposed to low HU doses (Hashash et al., 2011). The sml1Δ rad53Δ, sml1Δ rad53Δ pif1-m2, sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ and sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ pif1-m2 strains were released from G1 into 25 mM HU and analyzed by pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) and Southern blotting at the indicated time points (Figure 3). The G1 chromosomes entered into the PFGE gel, while replicating chromosomes in HU-arrested cells were retained into the wells (Figure 3). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis showed that while pif1-m2 and rrm3Δ mutations slightly influenced the bulk of DNA synthesis, in an sml1Δ rad53Δ background, the combination of pif1-m2 and rrm3Δ mutations allowed sml1Δ rad53Δ cells to complete replication and progress through mitosis into the next cell cycle (Figures 3A–3C). Using PFGE, we found that in sml1Δ rad53Δ cells, most of chromosome III migrated in the gel in G1-arrested cells, while it was retained in the wells at 1.5 hr in HU. At 3 and 5 hr in HU, massive chromosome fragmentation appeared (Figures 3A–3C). The pif1-m2 or rrm3Δ mutations partially suppressed chromosome fragmentation in sml1Δ rad53Δ cells (Figures 3A, 3B, and S3A). The suppression of double-stranded break (DSB) accumulation was higher when both pif1-m2 and rrm3Δ mutations were introduced in the sml1Δ rad53Δ background and, concomitantly, chromosomes III migrated in the gel with minimal fragmentation (Figures 3C and S3A). We failed to detect chromosome III fragmentation in a sml1Δ WT RAD53 background carrying the pif1-m2, rrm3Δ, or pif1-m2 rrm3Δ mutations (data not shown). To address whether the metaphase to anaphase transition influenced chromosome fragmentation, we performed analogous experiments in the presence of nocodazole (which blocks cells in metaphase) and obtained similar results (Figure S3B). Ablations of PIF1 and RRM3 suppressed chromosome fragmentation in HU-treated rad53 cells even when SML1 was deleted and Rrn1 was overexpressed (Figure S3C). Because SML1 deletion and Rrn1 overexpression increase dNTP levels of at least 10-fold (Poli et al., 2012), this observation rules out that dNTP levels influence the mechanism of suppression.

Figure 3.

RRM3 and PIF1 Ablations Suppress Replication Stress-Induced Chromosome Fragility in rad53 Mutants

(A–C) PFGE and Southern blotting analysis of chromosome III (Chr 3) using an ARS305 recognizing probe in strains CY12443, CY13339, CY12460, and CY13342 at the indicated time points after a G1 release into 25 mM HU. The black line and the black bracket indicate, respectively, the migration position of the entire Chr 3 and the region of the gel in which chromosome fragmentation is detectable. The position of the wells is indicated.

(C) The red arrow in indicates Chr 3, which re-enters into the gel in the presence of HU in the sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ pif1-m2 cells. Yellow arrows indicate cell-cycle progression into mitosis in the quadruple mutant sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ pif1-m2. FACS profiles are shown.

See also Figure S3.

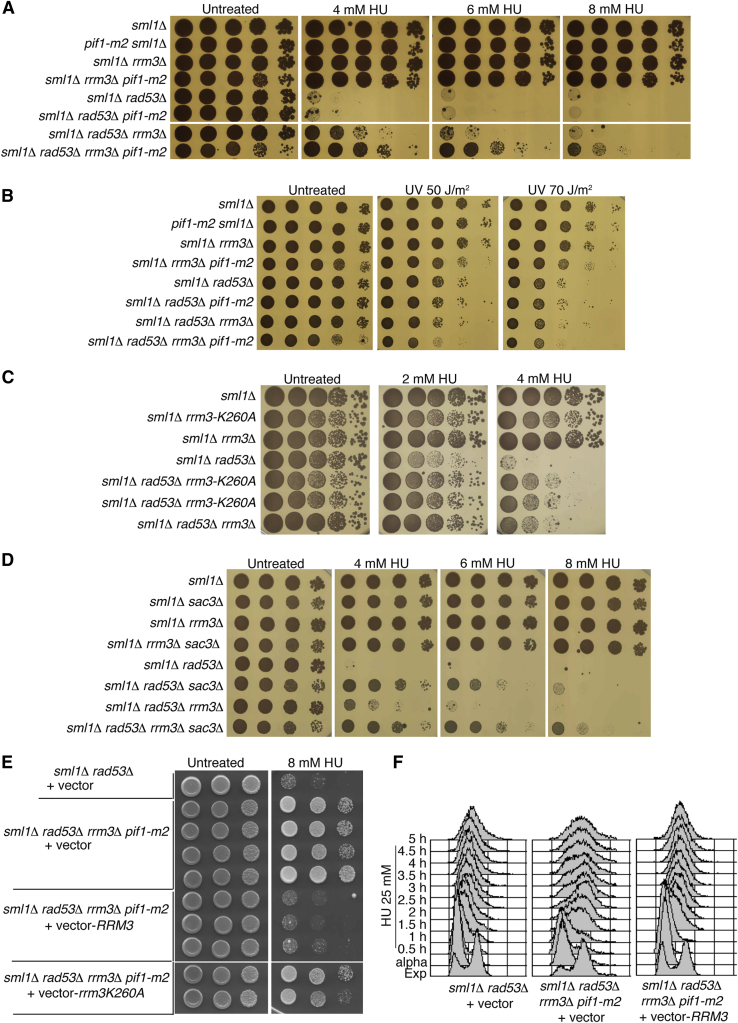

We conclude that Pif1 and Rrm3 are detrimental to the integrity of replicating chromosomes in the absence of Rad53 following replication stress. These observations imply that Pif1 and Rrm3 should also be detrimental for the viability of rad53 cells in HU. We found that the pif1-m2 mutation alone did not influence rad53 viability in HU (Figure 4A). Conversely, RRM3 deletion partially rescued the HU sensitivity of rad53 mutants, and this suppression was enhanced when both pif1-m2 and rrm3Δ mutations were present (Figures 4A, S4A, and S4B). Hence, the pif1-m2 allele exerts its suppression potential only when RRM3 is ablated. The suppression effect of pif1-m2 and rrm3Δ was specific for replication stress induced by dNTP deprivation, because they did not influence rad53 viability following UV-induced DNA damage (Figure 4B). Moreover, the helicase-dead rrm3-K260A mutation suppressed the rad53 HU sensitivity to the same extent as RRM3 deletion, implying that the detrimental effect of Rrm3 in a rad53 mutant background depends on Rrm3 activity (Figure 4C). It has been shown that gene gating defective mutants partially suppress the HU sensitivity of rad53 cells (Bermejo et al., 2011). We combined rrm3Δ with sac3Δ (altered in gene gating) and found that the suppression capability of these mutations was additive in a rad53 background, suggesting that rrm3Δ and sac3Δ influence the viability of HU-treated rad53 cells through different mechanisms (Figure 4D). To rule out that suppression of HU sensitivity caused by the combination of pif1-m2 and rrm3Δ mutations with RAD53 deletion was due to other unknown mutations, we complemented the quadruple mutant strain sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ pif1-m2 used in Figures 2B, 3C, 4A, 4B, and S2A with a centromeric plasmid carrying either the WT RRM3 gene or the helicase-dead allele rrm3-K260A (Ivessa et al., 2002). We found that suppression of HU sensitivity in the sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ pif1-m2 strain was abolished only when the WT RRM3 gene was present (Figure 4E). When we expressed Rrm3 in the sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ pif1-m2 strain, the replication block caused by the absence of RAD53 and the presence of HU was restored, demonstrating that the capability of the sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ pif1-m2 strain to replicate in 25 mM HU (Figure 3C) was due to the absence of Rrm3 (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Rrm3 and Pif1 Are Detrimental in rad53 Mutants under Replication Stress

(A) HU sensitivity at the indicated dosages was determined by drop assay in strains CY12445, CY13331, CY12448, CY13334, CY12443, CY13339, CY12460, and CY13342.

(B) Same as in (A) but, after cell deposition, the plates were irradiated with the indicated UV dosages (expressed in J/m2).

(C) HU sensitivity was determined as in (A) but with strains CY12867, CY13173, CY12448, CY12865, CY13172, CY13174, and CY12460.

(D) HU sensitivity was determined as in (A) but with strains CY12445, CY12682, CY12448, CY12690, CY12674, CY12681, CY12460, and CY12689.

(E) HU sensitivity was determined as in (A) for strains CY12443 and CY13342, transformed with the indicated plasmids YCplac111 (empty vector), YCplac111-RRM3, or YCplac111-rrm3-K260A expressing either the WT form of Rrm3 or the helicase-dead mutant allele rrm3-K260A (Ivessa et al., 2002).

(F) The strains CY12443 (transformed with YCplac111) and CY13342 (transformed with either YCplac111 or YCplac111-RRM3) were arrested in G1 and released in 25 mM of HU. The cellular DNA content was determined by FACS analysis at the indicated time points.

See also Figure S4.

Rrm3 and Pif1 Are Phosphorylated in a Rad53-Dependent Manner following Replication Stress

Pif1 is phosphorylated in HU-treated cells (Makovets and Blackburn, 2009). We investigated whether Pif1, and eventually Rrm3, were phosphorylated under replication stress in a checkpoint-dependent manner. Rrm3-Myc and Pif1-Flag sml1Δ strains were released from G1 into 150 mM HU. Samples were analyzed by western blotting using phospho-tag gels to maximize the mobility shifts due to phosphorylation (Kinoshita et al., 2006). Both Rrm3 and Pif1 exhibited mobility shifts, between 30 and 45 min following the release into HU (Figures 5A and 5B). We then addressed whether the HU-induced phosphorylation events were dependent on Rad53. Rrm3-Myc and Pif1-Flag sml1Δ and sml1Δ rad53Δ strains were treated under the same conditions, and samples were taken after 90 min from the G1 release in HU (Figure 5C). We found that the mobility shifts of Rrm3 and Pif1 were abolished in the absence of Rad53. Hence, both Rrm3 and Pif1 are regulated through phosphorylation in a Rad53-dependent manner under replication stress, but these phosphorylation events are unlikely to control their bindings to forks (Figures 1A and 1B).

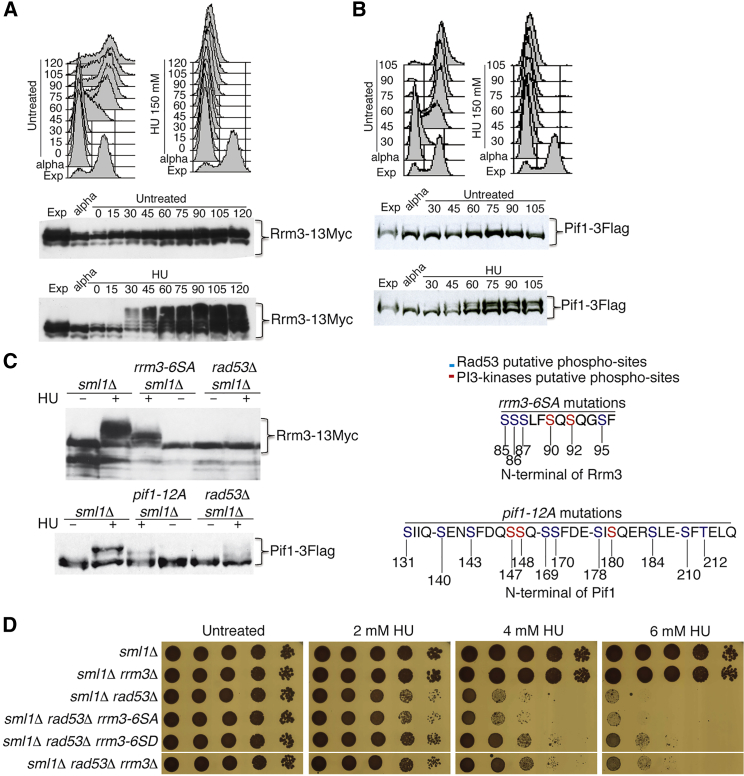

Figure 5.

Rad53-Dependent Rrm3 and Pif1 Hyper-phosphorylation and Characterization of Phospho-mimicking rrm3-6SD and pif1-12D Alleles

(A) The strain CY11360 was arrested in G1 and released in the presence or absence of 150 mM HU. HU-induced hyper-phosphorylation of Rrm3-13Myc was visualized by western blotting using phospho-tag gels and anti-myc antibodies at the indicated time points. FACS profiles are shown.

(B) Same as in (A), but HU-induced hyper-phosphorylation of Pif1-6His-3Flag was analyzed in strain CY13074.

(C) The RAD53 genetic dependence of the HU-induced Rrm3 and Pif1 hyper-phosphorylations and the phosphorylation state of the rrm3-6SA and pif1-12A mutant proteins were analyzed at 90 min from G1 release into 150 mM HU in strains CY12867, CY12953, CY12865, CY13074, CY13664, and CY13073. The Rrm3 and Pif1 protein sequences with the putative phosphorylation sites for PI3 kinases (red) or Rad53 (blue), substituted to alanine in the rrm3-6SA and pif1-12A phospho-deficient alleles or to aspartate in the corresponding phospho-mimicking alleles, are shown.

(D) HU sensitivity was determined by drop assay at the indicated HU dosages in strains CY12867, CY12448, CY12865, CY12960, CY12850, and CY12460.

See also Figures S5–S7.

We then identified in the N terminus of Rrm3 six serines clustered in a sequence of 12 amino acids, which represented potential consensus motives for Rad53 and Mec1 (Figure 5C) (Smolka et al., 2007). Mutagenesis of the six serines to alanine or aspartic residues gave rise, respectively, to the phospho-defective rrm3-6SA or the phospho-mimicking rrm3-6SD alleles. In the rrm3-6SA mutant, the HU-induced and Rad53-dependent hyper-phosphorylated isoforms of Rrm3 were significantly reduced (Figure 5C). The protein levels of the products encoded by the rrm3-6SA and rrm3-6SD mutated genes were comparable with the ones of WT RRM3 (Figure S5A). By comparing rrm3-6SA and rrm3-6SD mutant strains with rrm3Δ or WT RRM3 cells, we found that the phospho-sites mutants did not exhibit any histone H2A or Rad53 hyper-phosphorylation when grown under unperturbed conditions (Figure S5A). Moreover, they did not show massive fork slow down at the replication fork barrier (RFB) at rDNA and at the tRNAA locus, which are typical Rrm3-dependent pausing sites (Figures S5B and S5C) (Ivessa et al., 2000, 2003). Finally, we analyzed fork pausing at the tRNAA gene in sml1Δ, sml1Δ rad53Δ, and sml1Δ rrm3Δ cells growing under normal conditions or following a 90 min treatment in 25 mM of HU (Figure S5D). We found that in both conditions, sml1Δ rrm3Δ cells were the only ones accumulating pausing signals at the tRNAA gene locus. Hence, Rad53 and Rad53-mediated Rrm3 and Pif1 phosphorylation do not seem to influence replication across natural pausing sites. We then combined the rrm3 phospho-site mutations with the deletion of RAD53 and found that while the rrm3-6SD allele was able to rescue the HU sensitivity of rad53 cells to the same extent as RRM3 deletion, the rrm3-6SA mutation did not influence rad53 viability in the presence of HU (Figure 5D).

We identified a region in the N terminus of Pif1 (Figure 5C, amino acids 131–212), in which 11 serine residues and 1 threonine represented putative Rad53 and Mec1 phosphorylation sites (Smolka et al., 2007). Mutagenesis of these 12 residues to alanine or aspartic acid gave rise to the pif1-12A and pif1-12D mutant alleles (Figure 5C). These mutations did not affect Pif1 protein levels, did not influence the length of the telomeres (a typical phenotype of pif1-m2 cells [Schulz and Zakian, 1994]), and did not increase the frequency of petite cells (a read out of mitochondrial dysfunctions) (Figures S6A and S6B and data not shown). The pif1-12A phospho-deficient allele reduced the HU-induced and Rad53-dependent hyper-phosphorylated isoforms of Pif1 (Figure 5C). We combined the pif1-12A or pif1-12D alleles in RRM3, rrm3-6SA, and rrm3-6SD strains carrying two integrated copies of the galactose-inducible rad53-D339A dominant-negative allele (Pellicioli et al., 1999). Following rad53-D339A overexpression, pif1-12A, rrm3-6SA, or pif1-12D mutations alone did not influence cell survival in the presence of HU. Conversely, rrm3-6SD or the combination rrm3-6SD pif1-12D was able to suppress rad53 HU sensitivity (Figure S7). The double phospho-mimicking rrm3-6SD pif1-12D mutant did not exhibit much better survival of HU compared to rrm3-6SD alone (Figure S7), likely because the phospho-mimicking mutations in PIF1 did not fully resemble a constitutively phosphorylated gene product. Altogether, these observations suggest that Rad53 negatively regulates Rrm3 and Pif1 through phosphorylation and that this regulatory process counteracts toxic events mediated by Rrm3 and Pif1 at stalled forks.

Rrm3 and Pif1 Promote Fork Reversal in Checkpoint-Defective Cells Exposed to Replication Stress

We used psoralen crosslinking followed by electron microscopy (EM) (Neelsen et al., 2014) to visualize the fate of replication intermediates in sml1Δ rad53Δ and sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ pif1-m2 mutant cells. We analyzed 165 forks in sml1Δ rad53Δ and found abnormal replication structures as previously described (Sogo et al., 2002). In particular, 41% were resected forks, in either hemi-replicated or gapped conformation, and contained extensive ssDNA regions (Figures 6A–6C and 6F); 10% were reversed forks (Figures 6D–6F); and 7% were broken forks (Figures 6E and 6F). We then analyzed 155 forks in sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ pif1-m2 cells and found that 28% were resected forks, 2% were reversed forks, and 2% were broken forks (Figure 6F). We also found that while the length of the ssDNA gaps in sml1Δ rad53Δ cells at fork branching points was distributed around 800 nt, in sml1Δ rad53Δ rrm3Δ pif1-m2 mutants, the gaps were significantly shorter (Figure 6G). We conclude that Rrm3 and Pif1 contribute to the accumulation of resected and reversed forks in checkpoint-defective cells.

Figure 6.

Rrm3 and Pif1 Contribute to Fork Abnormalities in rad53 Cells Treated with HU

(A–E) Representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) pictures of in vivo psoralen crosslinked DNA replication forks with different structural features (hemi-replicated forks, gapped forks, reversed forks, and broken forks), isolated from strains CY12443 and CY13342 at 90 min from G1 release into 150 mM HU.

(F) A plot representing the means of the percentages and SDs of the DNA replication fork structures found in two independent experiments. At least 80 DNA replication forks were analyzed for each experiment. The number of samples (molecules) in the dataset is 165 forks for CY12443 and 155 forks for CY13342.

(G) Distributions of the length of the ssDNA gaps measured at the fork branching points in the two strains. The ssDNA data representation is as follows (box plot): center line, median; box limits, 10th and 90th percentiles; whiskers, 1st and 99th percentiles; black dots, outliers. ∗ p < 0.05 by two-tailed t test. Means of the percentages of gapped forks identified in the two strains in the two independent experiments are reported. The orange arrows indicate the structural features of the reversed forks and the distribution of these replication intermediates in the indicated genetic backgrounds. The 200 nm scale bars are reported in black in each TEM picture.

Discussion

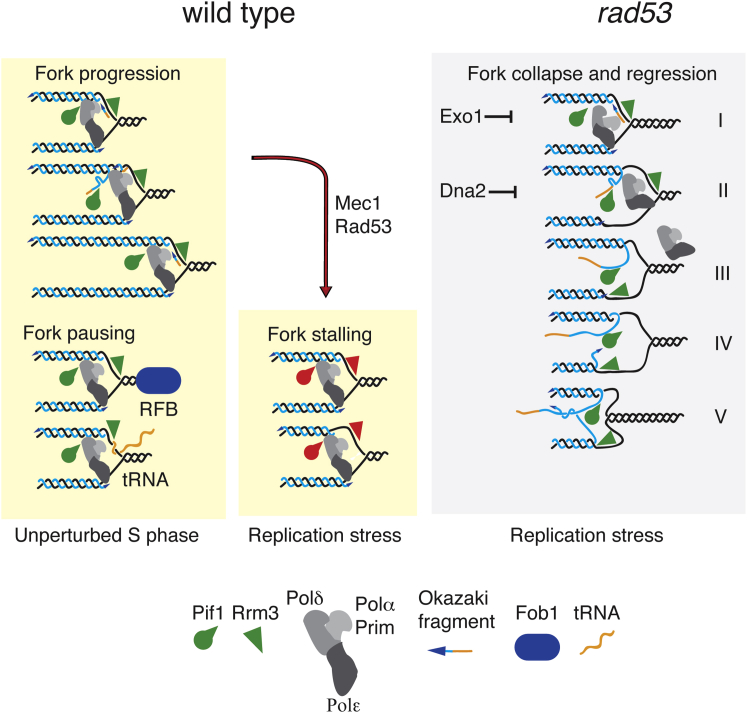

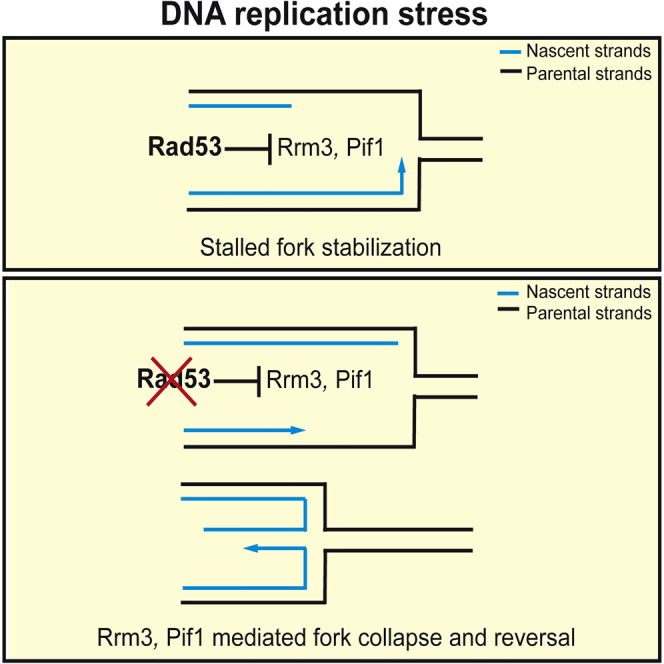

We showed that, following replication stress, the Mec1-Rad53 axis negatively regulates the activity of Rrm3 and Pif1 helicases at stalled forks and that RRM3 and PIF1 ablations ameliorate checkpoint mutants, which cannot recover from HU-induced fork stalling. Our observations do not exclude that other replication factors contribute to prevent aberrant transitions at HU-induced stalled forks. Previous observations showed that both helicases assist fork progression across replication pausing elements during the unperturbed S phase. Rrm3 and Pif1 have 5′-to-3′ DNA helicase activities. Based on the polarity of the helicase activity (Bochman et al., 2010) and on its interaction with PCNA (Schmidt et al., 2002), Rrm3 may travel on the lagging strand to facilitate Okazaki fragment synthesis. However, because Rrm3 interacts also with Pol ε (Azvolinsky et al., 2006), it cannot be ruled out that at least a fraction of Rrm3 may counteract DNA synthesis on the leading strand, perhaps to promote occasional backtracking of the replisome or Pol ε-mediated proofreading (Johnson et al., 2015). S. pombe Pfh1 assists fork progression across pausing elements containing both non-nucleosomal DNA-protein complexes and transcribed regions (Sabouri et al., 2012), whereas S. cerevisiae Pif1 has been involved in resolving stable intra-molecular DNA structures such as G4 quadruplexes (Paeschke et al., 2011, 2013), facilitating Okazaki fragment processing by generating long flaps (Pike et al., 2009; Rossi et al., 2008), and preventing their intra-molecular annealing (Pike et al., 2010). Accordingly, Rrm3 and Pfh1 ablations cause extensive pausing at fork barriers and transcribed regions, and Pif1 depletion affects replication across G4 quadruplex regions and Okazaki fragment processing (Fachinetti et al., 2010; Ivessa et al., 2000, 2003; Paeschke et al., 2013; Pike et al., 2009; Sabouri et al., 2012). Pif1 activity also leads to the deleterious formation of long 5′ flaps during Okazaki fragment processing in the absence of Dna2 (Budd et al., 2006; Rossi et al., 2008). Given that both Rrm3 and Pif1 have been implicated in assisting lagging strand synthesis, a logical expectation is that a Rad53-mediated inhibition of Rrm3 and Pif1 helicase activities would preferentially affect the polymerization of the lagging strand (Figure 7). This asymmetric stalled fork configuration with advanced leading strand and stable replisome- or helicase-fork complexes may facilitate, in some way, fork restart following HU removal and checkpoint deactivation. Accordingly, in WT cells, forks stalled by HU exhibited an asymmetric accumulation of approximately 100 nt of ssDNA at the fork branching point (Sogo et al., 2002).

Figure 7.

Model of the Rad53-Dependent Regulation of Rrm3 and Pif1 at Stalled Replication Forks

In unperturbed conditions, fork progression is assisted by Rrm3 and Pif1, particularly at pausing sites where they facilitate lagging strand synthesis. The presence of proteinaceous fork barriers like Fob1 or pausing elements like tRNAs in a head-on conformation would prevent fork pausing with an advanced lagging strand conformation. Hence, Rrm3 and Pif1 would retain their enzymatic activities to promote fork advance across the pausing sites. In the presence of HU, Rad53 inhibits Rrm3 and Pif1 on the lagging strand, leading to a stalled replication fork with an asymmetric configuration with an advanced leading strand. In HU-treated rad53 cells, the unscheduled activities of Rrm3 and Pif1 at the stalled forks may promote fork reversal through a multistep process.

Step 1 would require the combined action of active Rrm3 and DNA primase to form an asymmetric stalled fork with the lagging strand protruding.

In step 2, the last Okazaki fragment would form a flap, thus generating a potential substrate for Pif1.

In step 3, the template strands would re-anneal at the fork branching point. The re-annealing of the template strands behind the branching point of the fork might allow Rrm3 to jump from the lagging template to the leading template and promote replisome dissociation. It is also possible that a fraction of Rrm3 is already pre-assembled at the leading template.

In step 4, while Pif1 would elongate the flaps, Rrm3 may dissociate the leading chain from the template, thus facilitating the annealing of the two nascent chains to form a reversed fork.

In step 5, reversed forks may branch migrate because of the combined action of Rrm3 and Pif1.

In checkpoint mutants, Rrm3 would remain unphosphorylated and active, generating a fork configuration opposite the one of WT cell, in which the lagging strand would be more elongated than the leading one. The described scenario is consistent with the finding that when forks stall, lagging strand-bound PCNA is unloaded in a Mec1- and Rad53-dependent manner (Yu et al., 2014). A stalled fork with a protruding lagging strand might be the ideal context to trigger the formation of chicken foot-like structures at forks: if the last Okazaki fragment is processed through the generation of a flap, then the template strands at the fork branching point would have enough space to re-anneal together, thus leading to the formation of a cruciform DNA structure in which the lagging flap is in a reversed conformation. Similar structures have been visualized in checkpoint-defective cells (Sogo et al., 2002) and may facilitate the formation of reversed forks by engaging the nascent leading strands into pairing with the lagging flaps.

The model described in Figure 7 implies that Rrm3 plays a pivotal role in fork reversal while Pif1 plays a minor role. In the absence of Pif1, it is expected that a fraction of reversed forks would still form, while it would be difficult to envisage fork reversal formation in the absence of both Rrm3 and Pif1. We found that in the absence of Rrm3, a fraction of Pif1-dependent cruciform structures still accumulate at forks in rad53 mutants (Figure 2B). Fork reversal may still occur, although less efficiently, due to unscheduled RNA priming followed by Pif1-dependent flap elongation. Several papers analyzed the in vitro activities of Pif1 helicases on DNA replication fork-like structures (Boulé and Zakian, 2007; George et al., 2009; Ramanagoudr-Bhojappa et al., 2014). The reported results are consistent with the model proposed here.

Exo1 and Dna2 have been shown to counteract fork reversal (Cotta-Ramusino et al., 2005; Hu et al., 2012). Both Exo1 and DNA2 have been implicated in lagging strand synthesis (Budd and Campbell, 1997; Budd et al., 1995; Tishkoff et al., 1997). According to the model described earlier, Exo1 may counteract fork reversal by resecting the lagging strand (Cotta-Ramusino et al., 2005), while Cds1 may prevent fork reversal by promoting a Dna2-dependent cleavage of regressed nascent strands (Hu et al., 2012). Our data, together with the observations in S. pombe (Hu et al., 2012), further suggest that fork reversal in response to replication stress represents a pathological event caused by checkpoint defects. However, in certain mammalian cell lines, fork reversal has been implicated in replication restart mechanisms under conditions causing replication stress (Berti et al., 2013; Zellweger et al., 2015).

The lagging strand replication machinery is only one of the checkpoint targets influencing stalled fork integrity. The checkpoint-mediated regulation of the gene gating apparatus represents another key event to prevent aberrant topological transitions leading to fork reversal (Bermejo et al., 2011). Moreover, in higher eukaryotes, the ATR-mediated regulation of SMARCAL1 in response to replication stress has been shown to prevent SMARCAL1-mediated fork remodeling and SLX4-dependent chromosome fragmentation (Couch et al., 2013).

Our findings suggest that in WT cells, the leading protruding configuration of stalled forks would protect them from fork reversal. Rrm3 and Pif1 have been identified as key mediators of replication fork progression across the Fob1-dependent RFB at the rDNA array (Ivessa et al., 2000) and across tRNA genes (Ivessa et al., 2003). The checkpoint kinases do not seem to control fork stability at the RFB (Calzada et al., 2005) and the tRNAA loci, raising the possibility that the context of natural pausing is different from that of HU-induced fork stalling. Indeed, it has been shown that at the RFB, forks stall in a nearly symmetric conformation with only 3 nt protruding in the lagging strand (Gruber et al., 2000). One possibility is that Fob1, by obstructing the migration of the fork branching point, has been evolutionarily selected to avoid a fork pausing configuration dependent on the checkpoint. Hence, forks encountering the Fob1 proteinaceous blockage would pause without having to inactivate Rrm3 and Pif1 (Figure 7). Along the same lines, tRNAs transcription in a head-on conformation with the approaching forks would specifically interfere with the lagging strands, and again, forks would pause without the need to inactivate Rrm3 and Pif1 (Figure 7).

Replication fork defects and chromosome fragmentation are thought to cause cell lethality in rad53 mutants under replication stress. RAD53 deleted cells accumulate fork defects long before chromosome fragmentation can be detected (Figures 2 and 3). One possibility is that in checkpoint-defective cells, the unscheduled activities of Rrm3 and Pif1 may cause a massive collapse of those forks arising from early origins. The firing of late and dormant origins, which is also typical of checkpoint mutants, might partially compensate for the aborted early replicons, but it may also lead to unscheduled clashes with transcription units in a head-on conformation. At certain genomic loci, this may cause chromosome fragility, particularly in a context in which transcription units are still tethered to the nuclear envelope (Bermejo et al., 2011). Genomic loci causing DNA replication slow down accumulate DSBs in checkpoint-defective cells (Cha and Kleckner, 2002; Hashash et al., 2011). Hence, the aberrant events at early replicons may be a pre-requisite for the subsequent chromosome fragmentation at RSZs.

Experimental Procedures

ChIP-chip and BrdU-chip experiments were performed and protein-DNA binding profiles and BrdU profiles were generated as described (Bermejo et al., 2009a, 2009b; Katou et al., 2003). The 2D gel electrophoresis was conducted on genomic DNA after sodium azide fixation and in vivo psoralen crosslinking as described (Liberi et al., 2006). PFGE analysis was performed as described (Giannattasio et al., 2010). Supplemental Experimental Procedures are available as Supplemental Information.

Author Contributions

S.E.R. and A.A. executed the experiments. W.C. analyzed the microarray data. M.F. wrote the paper and provided financial support and scientific advice. M.G. conceived and supervised the project, designed and executed the experiments, analyzed the data, and contributed to the writing of the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Zakian (Princeton University) for helpful discussions and Rrm3 expressing plasmids (Ivessa et al., 2002). We thank E. Blackburn (University of California) and S. Makovets (University of Edinburgh) (Makovets and Blackburn, 2009) for Pif1 plasmids. We also thank G. Liberi (CNR), D. Branzei (IFOM), and J. Niska (IFOM), for helpful discussions and S. Minardi (IFOM) for technological support. A.A. is supported by an AIRC fellowship. The work was supported by grants from AIRC, Telethon-Italy, and the European Commission to M.F.

Published: September 24, 2015

Footnotes

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, seven figures, and one table and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2015.08.073.

Contributor Information

Marco Foiani, Email: marco.foiani@ifom.eu.

Michele Giannattasio, Email: michele.giannattasio@ifom.eu.

Accession Numbers

The accession number for the experimental data reported in this paper is GEO: GSE68214.

Supplemental Information

References

- Azvolinsky A., Dunaway S., Torres J.Z., Bessler J.B., Zakian V.A. The S. cerevisiae Rrm3p DNA helicase moves with the replication fork and affects replication of all yeast chromosomes. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3104–3116. doi: 10.1101/gad.1478906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azvolinsky A., Giresi P.G., Lieb J.D., Zakian V.A. Highly transcribed RNA polymerase II genes are impediments to replication fork progression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. 2009;34:722–734. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermejo R., Capra T., Gonzalez-Huici V., Fachinetti D., Cocito A., Natoli G., Katou Y., Mori H., Kurokawa K., Shirahige K., Foiani M. Genome-organizing factors Top2 and Hmo1 prevent chromosome fragility at sites of S phase transcription. Cell. 2009;138:870–884. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermejo R., Katou Y.M., Shirahige K., Foiani M. ChIP-on-chip analysis of DNA topoisomerases. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009;582:103–118. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-340-4_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermejo R., Capra T., Jossen R., Colosio A., Frattini C., Carotenuto W., Cocito A., Doksani Y., Klein H., Gómez-González B. The replication checkpoint protects fork stability by releasing transcribed genes from nuclear pores. Cell. 2011;146:233–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berti M., Ray Chaudhuri A., Thangavel S., Gomathinayagam S., Kenig S., Vujanovic M., Odreman F., Glatter T., Graziano S., Mendoza-Maldonado R. Human RECQ1 promotes restart of replication forks reversed by DNA topoisomerase I inhibition. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:347–354. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochman M.L., Sabouri N., Zakian V.A. Unwinding the functions of the Pif1 family helicases. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2010;9:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulé J.B., Zakian V.A. The yeast Pif1p DNA helicase preferentially unwinds RNA DNA substrates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5809–5818. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzei D., Foiani M. The checkpoint response to replication stress. DNA Repair (Amst.) 2009;8:1038–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd M.E., Campbell J.L. A yeast replicative helicase, Dna2 helicase, interacts with yeast FEN-1 nuclease in carrying out its essential function. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:2136–2142. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd M.E., Choe W.C., Campbell J.L. DNA2 encodes a DNA helicase essential for replication of eukaryotic chromosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:26766–26769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd M.E., Reis C.C., Smith S., Myung K., Campbell J.L. Evidence suggesting that Pif1 helicase functions in DNA replication with the Dna2 helicase/nuclease and DNA polymerase delta. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:2490–2500. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2490-2500.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calzada A., Hodgson B., Kanemaki M., Bueno A., Labib K. Molecular anatomy and regulation of a stable replisome at a paused eukaryotic DNA replication fork. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1905–1919. doi: 10.1101/gad.337205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper A.M., Nghiem P., Arlt M.F., Glover T.W. ATR regulates fragile site stability. Cell. 2002;111:779–789. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha R.S., Kleckner N. ATR homolog Mec1 promotes fork progression, thus averting breaks in replication slow zones. Science. 2002;297:602–606. doi: 10.1126/science.1071398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb J.A., Schleker T., Rojas V., Bjergbaek L., Tercero J.A., Gasser S.M. Replisome instability, fork collapse, and gross chromosomal rearrangements arise synergistically from Mec1 kinase and RecQ helicase mutations. Genes Dev. 2005;19:3055–3069. doi: 10.1101/gad.361805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotta-Ramusino C., Fachinetti D., Lucca C., Doksani Y., Lopes M., Sogo J., Foiani M. Exo1 processes stalled replication forks and counteracts fork reversal in checkpoint-defective cells. Mol. Cell. 2005;17:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch F.B., Bansbach C.E., Driscoll R., Luzwick J.W., Glick G.G., Bétous R., Carroll C.M., Jung S.Y., Qin J., Cimprich K.A., Cortez D. ATR phosphorylates SMARCAL1 to prevent replication fork collapse. Genes Dev. 2013;27:1610–1623. doi: 10.1101/gad.214080.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Piccoli G., Katou Y., Itoh T., Nakato R., Shirahige K., Labib K. Replisome stability at defective DNA replication forks is independent of S phase checkpoint kinases. Mol. Cell. 2012;45:696–704. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande A.M., Newlon C.S. DNA replication fork pause sites dependent on transcription. Science. 1996;272:1030–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewar J.M., Lydall D. Pif1- and Exo1-dependent nucleases coordinate checkpoint activation following telomere uncapping. EMBO J. 2010;29:4020–4034. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe C.L., Ahn J.S., Dixon J., Whitby M.C. Mus81-Eme1 and Rqh1 involvement in processing stalled and collapsed replication forks. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:32753–32759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fachinetti D., Bermejo R., Cocito A., Minardi S., Katou Y., Kanoh Y., Shirahige K., Azvolinsky A., Zakian V.A., Foiani M. Replication termination at eukaryotic chromosomes is mediated by Top2 and occurs at genomic loci containing pausing elements. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:595–605. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng W., Collingwood D., Boeck M.E., Fox L.A., Alvino G.M., Fangman W.L., Raghuraman M.K., Brewer B.J. Genomic mapping of single-stranded DNA in hydroxyurea-challenged yeasts identifies origins of replication. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:148–155. doi: 10.1038/ncb1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forment J.V., Blasius M., Guerini I., Jackson S.P. Structure-specific DNA endonuclease Mus81/Eme1 generates DNA damage caused by Chk1 inactivation. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23517. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froget B., Blaisonneau J., Lambert S., Baldacci G. Cleavage of stalled forks by fission yeast Mus81/Eme1 in absence of DNA replication checkpoint. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:445–456. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George T., Wen Q., Griffiths R., Ganesh A., Meuth M., Sanders C.M. Human Pif1 helicase unwinds synthetic DNA structures resembling stalled DNA replication forks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:6491–6502. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannattasio M., Follonier C., Tourrière H., Puddu F., Lazzaro F., Pasero P., Lopes M., Plevani P., Muzi-Falconi M. Exo1 competes with repair synthesis, converts NER intermediates to long ssDNA gaps, and promotes checkpoint activation. Mol. Cell. 2010;40:50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber M., Wellinger R.E., Sogo J.M. Architecture of the replication fork stalled at the 3′ end of yeast ribosomal genes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:5777–5787. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5777-5787.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashash N., Johnson A.L., Cha R.S. Regulation of fragile sites expression in budding yeast by MEC1, RRM3 and hydroxyurea. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:181–185. doi: 10.1242/jcs.077313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Sun L., Shen F., Chen Y., Hua Y., Liu Y., Zhang M., Hu Y., Wang Q., Xu W. The intra-S phase checkpoint targets Dna2 to prevent stalled replication forks from reversing. Cell. 2012;149:1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Zhou Z., Elledge S.J. The DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways induce transcription by inhibition of the Crt1 repressor. Cell. 1998;94:595–605. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivessa A.S., Zhou J.Q., Zakian V.A. The Saccharomyces Pif1p DNA helicase and the highly related Rrm3p have opposite effects on replication fork progression in ribosomal DNA. Cell. 2000;100:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80683-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivessa A.S., Zhou J.Q., Schulz V.P., Monson E.K., Zakian V.A. Saccharomyces Rrm3p, a 5′ to 3′ DNA helicase that promotes replication fork progression through telomeric and subtelomeric DNA. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1383–1396. doi: 10.1101/gad.982902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivessa A.S., Lenzmeier B.A., Bessler J.B., Goudsouzian L.K., Schnakenberg S.L., Zakian V.A. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae helicase Rrm3p facilitates replication past nonhistone protein-DNA complexes. Mol. Cell. 2003;12:1525–1536. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00456-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R.E., Klassen R., Prakash L., Prakash S. A major role of DNA polymerase δ in replication of both the leading and lagging DNA strands. Mol. Cell. 2015;59:163–175. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katou Y., Kanoh Y., Bando M., Noguchi H., Tanaka H., Ashikari T., Sugimoto K., Shirahige K. S-phase checkpoint proteins Tof1 and Mrc1 form a stable replication-pausing complex. Nature. 2003;424:1078–1083. doi: 10.1038/nature01900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita E., Kinoshita-Kikuta E., Takiyama K., Koike T. Phosphate-binding tag, a new tool to visualize phosphorylated proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;5:749–757. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500024-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakoff I.H., Brown N.C., Reichard P. Inhibition of ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase by hydroxyurea. Cancer Res. 1968;28:1559–1565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberi G., Cotta-Ramusino C., Lopes M., Sogo J., Conti C., Bensimon A., Foiani M. Methods to study replication fork collapse in budding yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2006;409:442–462. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)09026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes M., Cotta-Ramusino C., Pellicioli A., Liberi G., Plevani P., Muzi-Falconi M., Newlon C.S., Foiani M. The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature. 2001;412:557–561. doi: 10.1038/35087613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes M., Foiani M., Sogo J.M. Multiple mechanisms control chromosome integrity after replication fork uncoupling and restart at irreparable UV lesions. Mol. Cell. 2006;21:15–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucca C., Vanoli F., Cotta-Ramusino C., Pellicioli A., Liberi G., Haber J., Foiani M. Checkpoint-mediated control of replisome-fork association and signalling in response to replication pausing. Oncogene. 2004;23:1206–1213. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makovets S., Blackburn E.H. DNA damage signalling prevents deleterious telomere addition at DNA breaks. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009;11:1383–1386. doi: 10.1038/ncb1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda K., Makise M., Sueyasu Y., Takehara M., Asano T., Mizushima T. Yeast two-hybrid analysis of the origin recognition complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: interaction between subunits and identification of binding proteins. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007;7:1263–1269. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neelsen K.J., Chaudhuri A.R., Follonier C., Herrador R., Lopes M. Visualization and interpretation of eukaryotic DNA replication intermediates in vivo by electron microscopy. Methods Mol. Biol. 2014;1094:177–208. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-706-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paeschke K., Capra J.A., Zakian V.A. DNA replication through G-quadruplex motifs is promoted by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pif1 DNA helicase. Cell. 2011;145:678–691. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paeschke K., Bochman M.L., Garcia P.D., Cejka P., Friedman K.L., Kowalczykowski S.C., Zakian V.A. Pif1 family helicases suppress genome instability at G-quadruplex motifs. Nature. 2013;497:458–462. doi: 10.1038/nature12149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicioli A., Lucca C., Liberi G., Marini F., Lopes M., Plevani P., Romano A., Di Fiore P.P., Foiani M. Activation of Rad53 kinase in response to DNA damage and its effect in modulating phosphorylation of the lagging strand DNA polymerase. EMBO J. 1999;18:6561–6572. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike J.E., Burgers P.M., Campbell J.L., Bambara R.A. Pif1 helicase lengthens some Okazaki fragment flaps necessitating Dna2 nuclease/helicase action in the two-nuclease processing pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:25170–25180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.023325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pike J.E., Henry R.A., Burgers P.M., Campbell J.L., Bambara R.A. An alternative pathway for Okazaki fragment processing: resolution of fold-back flaps by Pif1 helicase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:41712–41723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.146894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli J., Tsaponina O., Crabbé L., Keszthelyi A., Pantesco V., Chabes A., Lengronne A., Pasero P. dNTP pools determine fork progression and origin usage under replication stress. EMBO J. 2012;31:883–894. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanagoudr-Bhojappa R., Byrd A.K., Dahl C., Raney K.D. Yeast Pif1 accelerates annealing of complementary DNA strands. Biochemistry. 2014;53:7659–7669. doi: 10.1021/bi500746v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M.L., Pike J.E., Wang W., Burgers P.M., Campbell J.L., Bambara R.A. Pif1 helicase directs eukaryotic Okazaki fragments toward the two-nuclease cleavage pathway for primer removal. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:27483–27493. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804550200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabouri N., McDonald K.R., Webb C.J., Cristea I.M., Zakian V.A. DNA replication through hard-to-replicate sites, including both highly transcribed RNA Pol II and Pol III genes, requires the S. pombe Pfh1 helicase. Genes Dev. 2012;26:581–593. doi: 10.1101/gad.184697.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santocanale C., Diffley J.F. A Mec1- and Rad53-dependent checkpoint controls late-firing origins of DNA replication. Nature. 1998;395:615–618. doi: 10.1038/27001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt K.H., Derry K.L., Kolodner R.D. Saccharomyces cerevisiae RRM3, a 5′ to 3′ DNA helicase, physically interacts with proliferating cell nuclear antigen. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:45331–45337. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207263200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz V.P., Zakian V.A. The Saccharomyces PIF1 DNA helicase inhibits telomere elongation and de novo telomere formation. Cell. 1994;76:145–155. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirahige K., Hori Y., Shiraishi K., Yamashita M., Takahashi K., Obuse C., Tsurimoto T., Yoshikawa H. Regulation of DNA-replication origins during cell-cycle progression. Nature. 1998;395:618–621. doi: 10.1038/27007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smolka M.B., Albuquerque C.P., Chen S.H., Zhou H. Proteome-wide identification of in vivo targets of DNA damage checkpoint kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:10364–10369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701622104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sogo J.M., Lopes M., Foiani M. Fork reversal and ssDNA accumulation at stalled replication forks owing to checkpoint defects. Science. 2002;297:599–602. doi: 10.1126/science.1074023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z., Fay D.S., Marini F., Foiani M., Stern D.F. Spk1/Rad53 is regulated by Mec1-dependent protein phosphorylation in DNA replication and damage checkpoint pathways. Genes Dev. 1996;10:395–406. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syljuåsen R.G., Sørensen C.S., Hansen L.T., Fugger K., Lundin C., Johansson F., Helleday T., Sehested M., Lukas J., Bartek J. Inhibition of human Chk1 causes increased initiation of DNA replication, phosphorylation of ATR targets, and DNA breakage. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:3553–3562. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.9.3553-3562.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tishkoff D.X., Boerger A.L., Bertrand P., Filosi N., Gaida G.M., Kane M.F., Kolodner R.D. Identification and characterization of Saccharomyces cerevisiae EXO1, a gene encoding an exonuclease that interacts with MSH2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:7487–7492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo L.I., Altmeyer M., Rask M.B., Lukas C., Larsen D.H., Povlsen L.K., Bekker-Jensen S., Mailand N., Bartek J., Lukas J. ATR prohibits replication catastrophe by preventing global exhaustion of RPA. Cell. 2013;155:1088–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C., Gan H., Han J., Zhou Z.X., Jia S., Chabes A., Farrugia G., Ordog T., Zhang Z. Strand-specific analysis shows protein binding at replication forks and PCNA unloading from lagging strands when forks stall. Mol. Cell. 2014;56:551–563. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegerman P., Diffley J.F. Checkpoint-dependent inhibition of DNA replication initiation by Sld3 and Dbf4 phosphorylation. Nature. 2010;467:474–478. doi: 10.1038/nature09373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zellweger R., Dalcher D., Mutreja K., Berti M., Schmid J.A., Herrador R., Vindigni A., Lopes M. Rad51-mediated replication fork reversal is a global response to genotoxic treatments in human cells. J. Cell Biol. 2015;208:563–579. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201406099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Rothstein R. The Dun1 checkpoint kinase phosphorylates and regulates the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor Sml1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3746–3751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062502299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.