Abstract

We determined the effect of p53 activation on de novo protein synthesis using quantitative proteomics (pulsed stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture/pSILAC) in the colorectal cancer cell line SW480. This was combined with mRNA and noncoding RNA expression analyses by next generation sequencing (RNA-, miR-Seq). Furthermore, genome-wide DNA binding of p53 was analyzed by chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP-Seq). Thereby, we identified differentially regulated proteins (542 up, 569 down), mRNAs (1258 up, 415 down), miRNAs (111 up, 95 down) and lncRNAs (270 up, 123 down). Changes in protein and mRNA expression levels showed a positive correlation (r = 0.50, p < 0.0001). In total, we detected 133 direct p53 target genes that were differentially expressed and displayed p53 occupancy in the vicinity of their promoter. More transcriptionally induced genes displayed occupied p53 binding sites (4.3% mRNAs, 7.2% miRNAs, 6.3% lncRNAs, 5.9% proteins) than repressed genes (2.4% mRNAs, 3.2% miRNAs, 0.8% lncRNAs, 1.9% proteins), suggesting indirect mechanisms of repression. Around 50% of the down-regulated proteins displayed seed-matching sequences of p53-induced miRNAs in the corresponding 3′-UTRs. Moreover, proteins repressed by p53 significantly overlapped with those previously shown to be repressed by miR-34a. We confirmed up-regulation of the novel direct p53 target genes LINC01021, MDFI, ST14 and miR-486 and showed that ectopic LINC01021 expression inhibits proliferation in SW480 cells. Furthermore, KLF12, HMGB1 and CIT mRNAs were confirmed as direct targets of the p53-induced miR-34a, miR-205 and miR-486–5p, respectively. In line with the loss of p53 function during tumor progression, elevated expression of KLF12, HMGB1 and CIT was detected in advanced stages of cancer. In conclusion, the integration of multiple omics methods allowed the comprehensive identification of direct and indirect effectors of p53 that provide new insights and leads into the mechanisms of p53-mediated tumor suppression.

The p53 gene encodes a tumor-suppressive protein, which is activated by DNA damage, but also by other types of cellular stress (1). p53 functions as a transcription factor that regulates the expression of numerous genes, which mediate cell cycle arrest, senescence and apoptosis, or suppress epithelial–mesenchymal-transition (EMT)1 and metastasis (2–4). p53 is mutated in at least 50% of human cancers with ∼80% of the mutations located in its DNA binding domain (5, 6). Furthermore, p53's function may be repressed in tumors by binding to viral proteins or mutations in genes directly or indirectly controlling its degradation like MDM2 or p14ARF. In normal cells, p53 is barely detectable. After DNA damage, p53 is modified post-translationally via multiple enzymes, which leads to its stabilization (7). Subsequently, p53 binds as a tetramer to a consensus DNA-sequence consisting of two RRRCWWGYYY palindromes separated by a 0–13 base pair spacer (8, 9). One of the major outcomes of p53 binding to its response elements is the recruitment of histone methyltransferases and/or acetyltransferases, which mediate promoter opening and transcriptional initiation by RNA polymerase II (10). Different direct and indirect mechanisms how p53 mediates transcriptional repression have been described (reviewed in (11, 12)): repressive p53 response elements (REs) can overlap with binding sites for activating TFs or p53 can recruit repressive chromatin-modifying factors, such as histone deacetylases (HDACs) (11). Many of the described repressive p53 REs deviate in their sequence from activating p53 binding sites (12–14). However, a recent study also reports a consensus motif for repressed p53 targets that perfectly fits to the classical p53 motif (15). In addition, p53 is able to indirectly mediate repression by sequestering transcriptional activators or activating genes like CDKN1A/p21, which down-regulates the activity of E2Fs (11, 16). Furthermore, indirect repression can be mediated via noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), such as microRNAs (miRNAs) or long ncRNAs (lncRNAs). Interestingly, those different mechanisms of gene repression by p53 are not mutually exclusive. For example, c-Myc is transcriptionally repressed by direct binding of p53 to its promoter and post-transcriptionally via the p53-induced miRNA-145 (17, 18).

miRNAs are ncRNA molecules of 20–25 nucleotides that post-transcriptionally regulate gene expression by binding to partially complementary sites (so-called seed-matching sites) in the 3′-untranslated regions (3′-UTRs) of target mRNAs. Mature miRNAs are processed from an RNA hairpin and because both strands can be used for posttranscriptional gene silencing, they are referred to as miR-x-5p or −3p. Alternatively, the miRNA strand that is preferentially discarded is referred to as miRNA star strand or miRNA*. miRNAs down-regulate protein expression by promoting mRNA decay and/or translational repression (19, 20). Because more than 60% of all human mRNAs are miRNA targets, this mechanism of post-transcriptional gene regulation is of particular importance (21).

The miR-34 gene family, miR-34a and mir-34b/c, was the first miRNA family that was shown to be directly induced by p53 (22–26). Subsequently, a large number of miR-34a targets has been identified and validated (27). Recently, we have shown in a genome-wide screen using a combined pSILAC and microarray approach that miR-34a directly represses multiple mRNA targets that mediate G1 arrest and apoptosis, and suppress EMT/metastasis, Wnt signaling, and glycolysis (28). In particular, we have shown that p53-induced miR-34a reverses EMT via repression of SNAIL (29, 30), ZNF281 (31) or IL6R (32). Apart from the miR-34 family several other miRNAs, such as miR-145, miR-192, −194, −215, or miR-200c and −141, are directly induced by p53 and suppress important targets, thereby mediating the tumor-suppressive function of p53 (reviewed in (33)). Moreover, p53 enhances miRNA processing by interacting with the microprocessor component Drosha (34).

The pulsed stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (pSILAC) method (35, 36) used here allows to analyze the de novo protein synthesis by metabolic pulse labeling of cells using two different heavy isotopic forms of arginine and lysine and to monitor modest changes in miRNA-mediated regulations of proteins with long half-lives.

Our results indicate that p53 indirectly down-regulates several pro-tumorigenic target genes by direct and indirect transcriptional activation of miRNAs. In addition, we provide a comprehensive catalogue of p53-regulated proteins, mRNAs, miRNAs, and lncRNAs that will promote further studies of the p53-regulated transcriptional network.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture and Conditional Expression

The colorectal cancer cell line SW480 was cultured in DMEM medium with 10% FCS (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany), penicillin/streptomycin (10 units/ml) and 5% CO2. The episomal pRTR and pRTR-p53-VSV vectors employed here have been described previously (29, 37). Polyclonal cell pools for conditional expression were generated by transfection of pRTR vectors using Fugene6 (Roche, Penzberg, Germany) and selection in 2 μg/ml Puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Seetze, Germany) for 10 days. DOX (Sigma-Aldrich) was used at a final concentration of 100 ng/ml. Cells were treated with 20 μm Etoposide and 10 μm Nutlin (Sigma-Aldrich).

FACS Analysis

2 × 105 Cells were seeded per 6-well-plate and cultured with and without DOX for the indicated periods of time. To control the transfection efficiency, cells transfected with a pRTR-vector were trypsinized, washed and resuspended in PBS. Subsequently, the percentage of GFP-positive cells in 10,000 cells per sample was analyzed using a C6 Flow Cytometry instrument (Accuri/BD, Heidelberg, Germany). For cell-cycle analysis, cells were trypsinized, washed once in PBS and fixed in 70% EtOH overnight at −20 °C. The next day cells were washed with PBS and stained with 400 μl propidium iodide staining solution (37 °C, 30 min). Data from 10,000 cells were collected by FACS analysis.

Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysis was performed using RIPA lysis buffer (50 mm Tris/HCl, pH 8.0, 250 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecylsulfate, complete mini protease inhibitor tablets (Roche)). Lysates were sonicated and centrifuged at 16,060 g for 15 min at 4 °C. 100 μg of whole cell lysate per lane were separated using 12% SDS-acrylamide gels and transferred on Immobilon PVDF membranes (Millipore/Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). Antibodies detecting VSV (V4888, Sigma-Aldrich), p21 (Ab-11, Clone CP74, NeoMarkers) and β-actin (A2066, Sigma-Aldrich) were used.

RNA Isolation and qPCR Analysis

Total RNA was prepared with the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer′s protocol. cDNA was generated from 1 μg of total RNA per sample using anchored oligo(dT) primers (Verso cDNA Kit, Thermo Scientific, Dreieich, Germany). qPCR was performed by using the LightCycler 480 (Roche) and the Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany) as described previously (38). Only primer pairs resulting in a single peak in the melting curve analysis were used. Oligonucleotides used for qPCR are listed in supplemental Table S1.

miRNAs were isolated using the High Pure miRNA Isolation Kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer′s protocol. For detection of mature miR-34a, RNA was reverse transcribed using the miRCURY LNA Universal RT microRNA PCR-Kit (Exiqon, Vedbaeck, Germany) and qPCR was performed with the SYBR Green master mix provided using Exiqon LNA-Primer. Signals were normalized to U6. For detection of mature miR-486–5p and miR-205, cDNA was generated using the TaqMan MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems), qPCR was performed using the TaqMan Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and values were normalized to RNU48. For miR-486–5p detection, RNA had to be preamplified using the TaqMan PreAmp Master Mix (Applied Biosystems).

Real-time Impedance Measurement

Determinations of cellular impedance as a measure of cell proliferation were performed as described previously (39). Twenty-four hours after seeding, DOX was added to the respective wells. To validate the results of the impedance measurement, the cells were simultaneously seeded in triplicates into a 96-well plate and the number of living cells was counted using trypan blue after 96 h.

Generation of Reporter Constructs

The p53 binding site upstream of the host gene of miR-486–5p was PCR-amplified from genomic DNA of human diploid fibroblasts (primers are listed in supplemental Table S1) and ligated into the pBV-Luc vector upstream of a minimal promoter driving luciferase expression. The shortened versions of the 3′-UTRs of the human KLF12, HMGB1, and CIT mRNAs containing the respective miRNA binding sites were PCR-amplified from SW480 cDNA. The resulting 3′-UTR fragments were cloned into the shuttle vector pGEM-T-Easy (Promega, Mannheim, Germany). Subsequently, the respective 3′-UTRs were cloned into the pGL3-control-MCS (40) and verified by sequencing. Oligonucleotides used for cloning and mutagenesis are listed in supplemental Table S1.

Luciferase Assays

For reporter assays, SW480 cells were seeded in 12-well format at 5 × 104 cells/well and transfected with 100 ng of the pBV-Luc vector containing the p53 binding site of the gene encoding miR-486–5p, 20 ng of Renilla reporter plasmid as a normalization control, and 500 ng of pcDNA-p53-VSV or the empty vector control pcDNA-VSV using Fugene6 (Promega).

For 3′-UTR-reporter assays, 3 × 104 H1299 cells were seeded in a 12-well format, transfected the next day with 100 ng pGL3, 20 ng Renilla reporter plasmid as a normalization control and 25 nm pre-miRNA (Ambion; pre-miR-34a: PM11030, pre-miR-205 PM11015, pre-miR-486–5p: PM10546, pre-miR negative control #1) using Hiperfect (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). After 48 h the luciferase assay was performed using the Dual Luciferase Reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer′s protocol. Fluorescence intensities were measured with an Orion II luminometer in a 96-well format and analyzed with the SIMPLICITY software package (Berthold, Pforzheim, Germany).

miR-Seq Analysis

Total RNA from SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV and SW480/pRTR cells was isolated using the Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Darmstadt, Germany) following the manufacturer's protocol. 10 μg of the total RNA were run on a 12% Urea-PAGE (National Diagnostics, Hessle, Great Britain) to purify the small RNA fractions of each sample. Gel pieces were isolated corresponding to a size of about 15–30 nt and the contained RNA was collected by crushing the gel, elution overnight in elution buffer (300 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA) and precipitation with 2.5 volumes of 100% ethanol. The small RNA fraction was solved in 12 μl of RNase-free water and 10 μl were used for the generation of a small RNA library. Cloning was performed as described before (41). In short, an adenylated adapter was ligated to the 3′ end of the RNA by a truncated T4 RNA Ligase 2 (42), followed by the ligation of the 5′ adapter by T4 RNA Ligase 1 (NEB, Ipswich, Massachusetts). After reverse-transcription with a specific primer, the cDNA was amplified by PCR. The correct PCR product was gel-purified, eluted in elution buffer, precipitated and solved in water. The quality of the libraries was assessed by qPCR and Bioanalyzer measurements. Libraries were sequenced on a HiScan by the KFB (Kompetenzzentrum für fluoreszente Bioanalytik, Regensburg, Germany) in a 1 × 45 bp run. Oligonucleotides/adapters used are listed in supplemental Table S1. Fastq files were processed with an in-house pipeline consisting of adapter trimming, read alignment, read counting and normalization. Adapters were trimmed by computing a suffix-prefix alignment of each read against the Illumina 3′ adapter sequence. Trimmed reads were then aligned to the reference genome (hg19) using bowtie 0.12.7 (43) allowing for up to 2 mismatches. All best matches were retained and multi-mapping reads were equally divided among all mapping sites. To compute miRNA read counts all reads mapping to annotated mature miRNA positions (according to mirbase v16 (44)) were considered. At their 3′ end, a tolerance of ± 3 bp was allowed, but no tolerance at their 5′ end. Normalization was performed by fitting a robust linear model to the quantile-quantile plot of log miRNA counts and taking the offset as normalization factor. The miR-Seq data can be accessed in the GEO database using the accession number GSE67181.

RNA-Seq Analysis

3 × 105 SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV as well as SW480/pRTR were seeded on 10 cm plates and total RNA was isolated after 48 h DOX treatment. Total RNA was isolated using the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche) and its quality was determined with a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Oberhaching, Germany). Library preparation was done using an RNA-Seq Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer′s instructions and sequenced on a HiSeq 2000 (Illumina).

101-nt sequence reads from SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV and SW480/pRTR cells were aligned separately in a three-step mapping procedure described recently (45) using the short read alignment program Bowtie (version 0.12.7) (43). In step 1, reads were aligned to pre-rRNA sequences (18S, 5.8S, 28S, and spacer regions). In step 2, the remaining unmapped reads were aligned to Ensembl transcripts (ENSEMBL version 60), with the exclusion of pseudogenes and haplotypes. Finally, in step 3, reads that could not be aligned to known transcripts were aligned to the human reference genome (hg19). Reads that could be mapped equally well to more than one location were discarded. Bowtie was configured for all three steps in the following way: The first 60 nucleotides were chosen as the seed region. Three mismatches were allowed in the seed and 10 mismatches in the overall alignment.

Expression levels of Ensembl genes were determined using the rpkm (number of reads per kilobase of gene per million mapped reads) measure (46). Only reads mapped to an exon or exon-exon junction were included in the number of reads mapped to a gene. Log2 fold changes between the two samples (SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV and SW480/pRTR cells) were calculated from gene rpkm values and used to define induced (log2 fold change ≥ 1) and repressed (log2 fold change ≤ −1) genes. The RNA-Seq data can be accessed in the GEO database using the accession number GSE67109.

ChIP-Seq Analysis

SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV and SW480/pRTR were treated with DOX for 16 h before cross-linking to induce ectopic expression of p53. Cross-linking was performed with 1% formaldehyde (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and stopped after 5 mins by adding glycine at a final concentration of 0.125 m. Cells were harvested with SDS buffer (50 mm Tris pH 8.1, 0.5% SDS, 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA), pelleted and resuspended in IP buffer (2/3 SDS buffer and 1/3 Triton dilution buffer (100 mm Tris-HCl pH 8.6, 100 mm NaCl, 5 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, 0.2% NaN3, 5.0% Triton X-100)). Chromatin was sheared by sonication to generate DNA fragments with an average size of 500 bp. Preclearing and incubation with a polyclonal, VSV-specific antibody (V4888, Sigma-Aldrich) or IgG control (M7023, Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 h was performed as previously described (22). Washing and reversal of cross-linking was performed as described (47). The immunoprecipitated DNA-fragments were quantified using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Libraries were generated using a ChIP-Seq Sample Prep Kit (Illumina Part # 11257047) according to the manufacturer′s instructions and sequenced on a HiSeq 2000 (Illumina). 101-nt sequence reads were aligned separately for the two samples (SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV and SW480/pRTR cells) with the same three-step mapping procedure as for RNA-Seq analysis. Peaks were identified using MACS (version 1.4.2) (48) with default parameters. The output of MACS contains the genomic start and stop coordinates for every called peak, as well as the coordinate of the peak maximum (denoted as peak summit). For every called peak, the Ensembl gene with minimum distance between peak summit and respective transcription start site was determined. The ChIP-Seq data can be accessed in the GEO database using the accession number GSE67108.

qChIP Analysis

qChIP analysis was performed as described above and previously (37). The polyclonal VSV-specific antibody (V4888, Sigma-Aldrich) and an IgG control (M7023, Sigma-Aldrich) were used. Immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by qRT-PCR and the enrichment was displayed as percentage of the input for each condition (47). Oligonucleotides used for qChIP are listed in supplemental Table S1.

Analysis of Sequence Motifs

Genomic sequences ± 250 bp around the called peak summits were extracted for every peak with an associated gene within 20 kbp from the peak summit. If the peak start or end was less than 250 bp away from the summit, the extracted sequence started or ended with the peak start or end, respectively. MEME (version 4.7.0) (49) was applied on the generated sequences in order to discover p53 binding site motifs. The default parameter settings were used. The maximum number of motifs to find was set to 3. This step was repeated separately for sequences of peaks associated with induced and repressed genes, respectively. SpaMo (version 4.7.0) (50) was used to search for enriched transcription factor binding motifs located in direct proximity to the best predicted motif by MEME. The input of SpaMo were peak sequences, the output of the MEME run and the JASPAR core database (51) as source for secondary motifs. All other parameters were set to default.

pSILAC: Sample Preparation

pSILAC was performed as described previously (28). In brief, 5 × 105 SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV cells were seeded on 10 cm dishes and grown in light DMEM supplemented with light l-arginine (84 mg/l) and l-lysine (40 mg/l), 10% dialyzed FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin. After p53 induction for 16 h with 100 ng/ml DOX, cells were shifted to heavy SILAC medium (84 mg/l 13C6 15N4-l-arginine and 40 mg/l 13C6 15N2-l-lysine). The noninduced control samples were shifted to medium-heavy media (84 mg/l 13C6-l-arginine, 40 mg/l 2H4-l-lysine). To minimize arginine-to-proline conversion, the light, medium-heavy and heavy medium was supplemented with 100 mg/l of unlabeled proline. All reagents (DMEM, dialyzed FBS and amino acids) were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (Tewksbury, MA).

After 24 h, cells were harvested with urea buffer (30 mm Tris base, 7 m urea, 2 m thiourea, pH 8.5). In total, six independent pSILAC analyses were performed, including two with a label-swap, and subjected to further proteomic analysis.

pSILAC: Gel Electrophoresis and Tryptic Digestion of Proteins

Following cell lysis, proteins (30 μg per replicate) were separated by SDS-PAGE using 4–12% NuPage Bis-Tris gradient gels (Life Technologies) and visualized by colloidal Coomassie Brilliant Blue. Gel lanes were cut into 20 slices. Proteins were subjected to in-gel digestion using trypsin and prepared for LC-MS/MS analyses as described (52).

pSILAC: Mass Spectrometric Analyses

LC/MS analyses were performed using an UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano HPLC system (Thermo Scientific) and an Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Peptide mixtures were washed and preconcentrated for 5 min on a 5 mm × 0.3 mm PepMapTM C18 μ-precolumn (Thermo Scientific) followed by separation on a 50 cm × 75 μm C18 reversed-phase nano LC column (Acclaim PepMapTM RSLC column; 2 μm particle size; 100 Å pore size; Thermo Scientific) at a temperature of 40 °C using a 45 min linear gradient ranging from 4 to 36% (v/v) acetonitrile [ACN; in 0.1% (v/v) formic acid] followed by 36 to 82% (v/v) ACN in 5 min and 5 min at 82% ACN at a flow rate of 250 nl/min. The mass spectrometer was operated using a Nanospray Flex ion source with stainless steel emitters (Thermo Scientific) and externally calibrated using standard compounds. Full MS scans (m/z 370 - 1,700) were acquired in the orbitrap at a resolution of 60,000 (at m/z 400) with an automatic gain control (AGC) of 1 × 106 ions and a maximum fill time of 200 ms. Up to 25 of the most intense multiple charged precursor ions above a signal threshold of 2500 were fragmented by collision-induced dissociation in the linear ion trap at a normalized collision energy of 35%, an activation q of 0.25, an activation time of 10 ms, an AGC of 5 × 103 ions, and a maximum fill time of 150 ms. The dynamic exclusion time for previously fragmented precursor ions was 45 s.

pSILAC: Mass Spectrometric Data Analysis

Mass spectrometric raw data were processed with Andromeda/Max-Quant (version 1.3.0.5) (53, 54). Peaklists of MS/MS spectra were generated by MaxQuant using default settings and searched against the organism-specific UniProt human protein database including protein isoforms (version 2013_04; 88,656 entries) (55) and the set of common contaminants provided by MaxQuant. The MaxQuant search was restricted to human proteins because all experiments were performed with the human cell line SW480. Database searches were performed with tryptic specificity allowing two missed cleavages, mass tolerances of 20 ppm for the first, 6 ppm for the main search of precursor ions and 0.5 Da for fragment ions; oxidation of methionine and acetylation of protein N termini as variable modification; carbamidomethylation of cysteine as fixed modification. A false discovery rate of 1% calculated as described previously (53) was applied for filtering both the peptide identifications and the list of proteins. For protein identification, at least one unique peptide with a minimum length of seven amino acids was required. Proteins identified by the same set of peptides were combined to a single protein group by MaxQuant. SILAC-based relative protein quantification was based on unique peptides, Arg6 and Lys4 as medium-heavy (M) and Arg10 and Lys8 as heavy (H) labels. The variability of individual protein abundance ratios was calculated by MaxQuant and is the standard deviation of the natural logarithms of all peptide ratios used to determine the protein ratio multiplied by 100 (53). Only proteins quantified in at least two biological replicates were included in the subsequent statistical analysis. Protein abundance ratios reported as induced/noninduced (H/M or M/H) and normalized to the median of the respective replicate by MaxQuant to account for systematic deviations such as mixing errors were log2-transformed and the mean log2 ratios were calculated across all replicates with valid values for individual protein groups. A one-sample student's t test (unpaired, two-tailed) was performed comparing the log2-transformed abundance ratio (in replicates) to the value of 0 to determine whether a protein group showed a significant regulation (p value ≤ 0.05). Reproducibility of the results was further assessed by correlating log2 ratios and computing p values as described before, but for pairs of replicates (see supplemental Fig. S1). In nine out of 15 pairwise comparisons between all six replicates, a set of proteins appeared to be down-regulated in one replicate but unregulated in the other. In order to account for this effect, proteins exhibiting log2 fold changes ≤ −0.3 or ≥ 0.3 with a p value ≤ 0.05 across all replicates but showing p values > 0.3 in more than half of the pairwise comparisons of replicates indicative of a heterogeneous regulation were separately marked in the list of candidates (class II hits in supplemental Table S2A; marked with an asterisk (*) in Fig. 5, supplemental Tables S3, S4, S5, S18, S19). Further information about protein and peptide identifications and quantification are provided in supplemental Tables S2B and S2C.

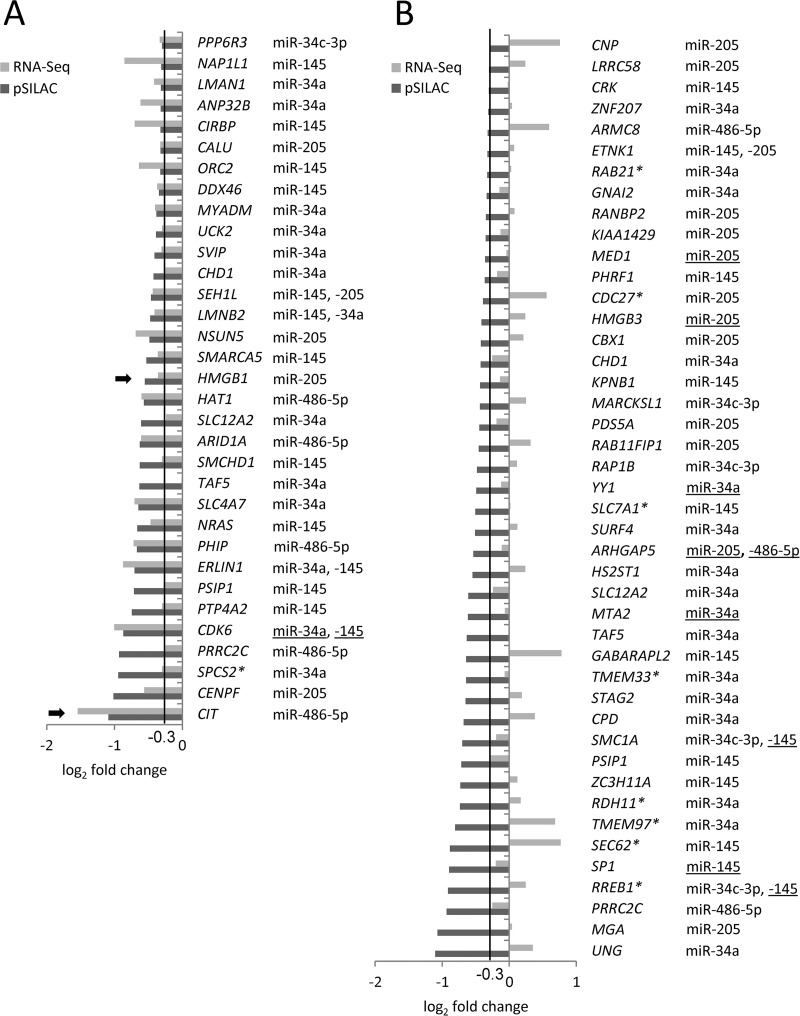

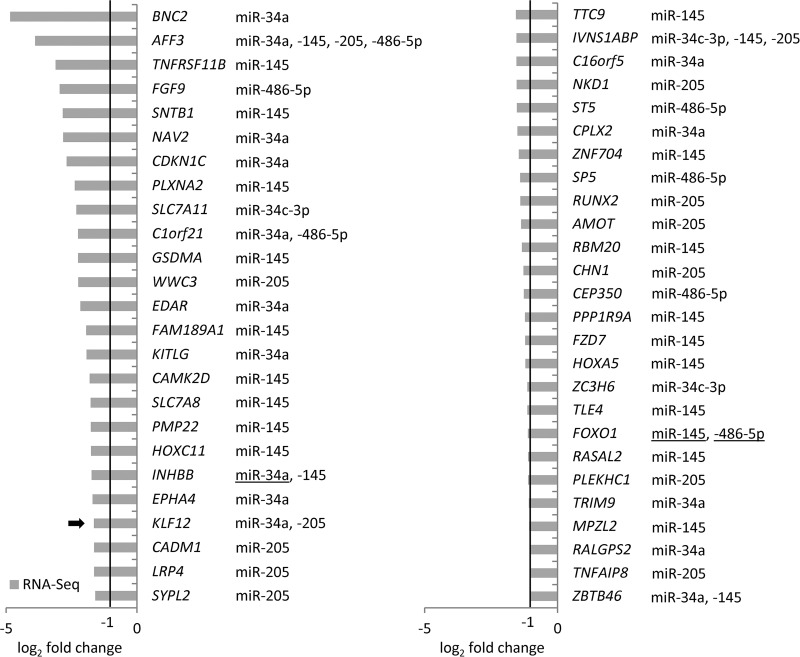

Fig. 5.

Putative targets of miRNAs directly induced by p53 with down-regulated mRNA- and de novo protein synthesis or reduced de novo protein synthesis only. Predicted miRNA targets with (A) down-regulated mRNA- and de novo protein synthesis, (B) reduced de novo protein synthesis only are displayed. Known miRNA targets are underlined and targets experimentally validated in this study are marked with a black arrow. Proteins that showed a heterogeneous distribution of fold changes in independent experiments (class II candidates, see Experimental procedures) are marked with an asterisk (*).

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the PRIDE partner repository (56) with the data set identifier PXD001976.

Web-based Expression Analysis and Algorithms

The Oncomine tool (57) was used to analyze the differential mRNA expression of HMGB1, KLF12 and CIT in human cancer data sets. The threshold for the p value and fold change was set to 0.05 and 1.5, respectively. The PROGgene online tool (58) was used to analyze the clinical significance of the target gene set HMGB1, KLF12, and CIT. To analyze overall and metastasis free survival, the colorectal cancer data sets GSE15736 and GSE11121 were used, respectively. MiRNA target prediction of directly up-regulated miRNAs was performed combining the results from the public databases TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org) and Pictar (http://pictar.mdc-berlin.de) (59, 60). Only conserved target sites were considered for further analysis. A KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of differentially up- and down-regulated mRNAs and proteins was perfomed using the DAVID bioinformatics database (61, 62). To visualize p53 occupancy, the ChIP-Seq data were uploaded in wig-format to the UCSC genome browser (63). The TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) database (64) was used for differential mRNA expression analyses in different tumor stages in the colorectal cancer data set (n = 424).

Statistical Analysis

A Student′s t test (unpaired, two-tailed) was used to determine significant differences between two groups of samples (applied for qPCR-, qChIP-, cell cycle-, and cell counting analyses, luciferase reporter assays and for differential gene expression analyses using TCGA). The Oncomine database provides a p value calculated with an independent, two-sample, one-tailed Welch′s t test. For KEGG pathway analyses the Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p value was considered. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied to calculate the significance of cumulative distribution analyses. For correlation analyses, a Pearson′s correlation was applied. p values < 0.05 were considered as significant (*: p < 0.05; **: p < 0.01; ***: p < 0.001).

RESULTS

NGS and pSILAC Analyses After p53 Activation

We studied the effect of p53 activation on the expression of proteins, mRNAs and ncRNAs as well as genome-wide DNA-binding by p53. For this purpose, we employed a recently described, episomal pRTR vector system that allows DOX-inducible expression of the introduced cDNA (29, 37). SW480 CRC cells were transfected with pRTR-p53-VSV vectors and after selection for 2 weeks, stable cell pools were obtained. As a control, an SW480 cell pool harboring a pRTR vector only expressing GFP was generated. 95.7% and 85.2% of the cells in the SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV and SW480/pRTR pools, respectively, were positive for GFP-expression 48 h after addition of DOX (supplemental Fig. S2A). SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV cells showed a prominent induction of p53 expression after addition of DOX and the p53 target p21 was up-regulated (supplemental Fig. S2B). Moreover, p53 activation resulted in a 20% increase in the G1-phase and a minor increase in the sub-G1-phase (supplemental Fig. S2C). In addition, the adoption of a flat and enlarged cell shape indicated a p53-induced cell cycle arrest (supplemental Fig. S2D).

Next, we performed miRNA-, RNA- and ChIP-Seq as well as pSILAC analyses (Fig. 1; supplemental Fig. S2E). For the miR-Seq as well as for the ChIP-Seq analyses, a short period of 16 h of p53 activation was chosen in order to preferentially identify directly regulated miRNAs. For RNA-Seq and pSILAC, late time-points of 48 and 40 h, respectively, were selected in order to allow the identification of mRNAs and proteins down-regulated by p53-induced miRNAs. The NGS analyses resulted in 13 to 42 million reads per library (supplemental Fig. S2E). The pSILAC analysis identified 67,090 peptides (60,911 unique sequences) derived from about 5,000 proteins.

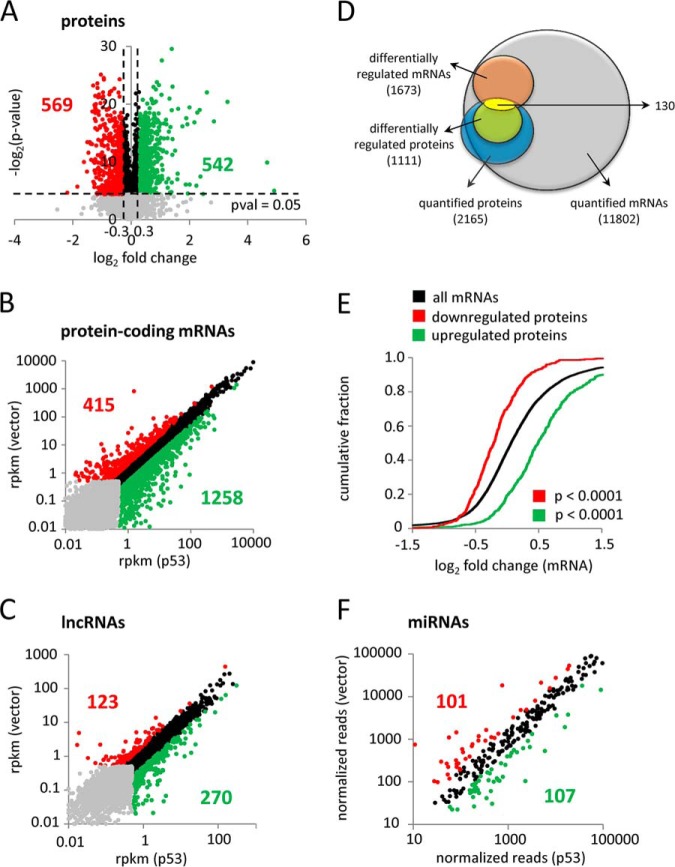

Fig. 1.

Differential protein, mRNA, lncRNA and miRNA regulation by p53. SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV were subjected to pSILAC, mRNA- and miRNA-Seq analyses after 48, 40 and 16 h DOX treatment, respectively. A, Volcano plot classification of proteins quantified in pSILAC experiments. Log-transformed p values (-log2) are plotted against the mean log2 of the corresponding pSILAC abundance ratios (induced/noninduced) of proteins quantified in at least two out of six replicates. Significantly regulated proteins with a log2 fold change ≥ 0.3 are indicated in green, with a log2 fold change ≤ -0.3 are marked in red and with 0.3 > log2 fold change > −0.3 in black. Proteins with a p value > 0.05 are represented by gray dots. B, C, rpkm scatter plot depicting expression changes of protein-coding mRNAs (B) and lncRNAs (C) detected by RNA-Seq. Transcripts with an rpkm < 0.5 in both conditions are shown in gray. Transcripts with a log2 fold change ≥ 1 are shown in green, with a log2 fold change ≤ −1 in red and with 1 > log2 fold change > −1 in black. D, Venn diagram displaying the overlap between quantified mRNAs (with an rpkm ≥ 0.5 in at least one condition) (shown in gray) and proteins (with a p value < 0.05) (shown in blue) and differentially regulated mRNAs (log2 fold change ≤ −1 or ≥ 1) (shown in orange) and proteins (log2 fold change ≤ −0.3 or ≥ 0.3) (shown in green). Genes differentially expressed on the mRNA level and the level of de novo protein synthesis are indicated in yellow. E, Cumulative distribution plot displaying changes in mRNA expression of up- and down-regulated proteins compared with the normal distribution of all mRNAs detected by RNA-Seq after activation of p53. F, Normalized read count scatter plot depicting expression changes of mature miRNAs. miRNAs with a log2 fold change ≥ 1 are shown in green, with a log2 fold change ≤ −1 in red and with 1 > log2 fold change > −1 in black.

pSILAC analysis of protein expression after p53 activation

Our pSILAC analysis resulted in the identification of 5,126 proteins and the quantification of 4,692 proteins in at least two out of six replicates (including two replicates with a label swap; for a complete list of identified proteins, see supplemental Table S2A). Only those proteins that were identified by peptide hits in at least two replicates (n = 2) with a p value ≤ 0.05 were considered for further analysis. In order to include moderate effects by p53-induced miRNAs, which were expected because of the previously observed moderate regulation of de novo protein synthesis after ectopic miRNA expression (28, 35), we applied a low-stringency cutoff of ≤ −0.3 or ≥ 0.3 log2 fold changes in protein expression. Based on these criteria, we determined 542 up- and 569 down-regulated proteins (Fig. 1A). The top 50 down- and 50 up-regulated proteins (all log2 fold changes > 1) are listed in supplemental Tables S3A and 3B, respectively.

A KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the set of proteins involved in DNA replication (p = 1.14E-28) and cell cycle regulation (p = 9.59E-14) was highly enriched among the down-regulated proteins (supplemental Table S4). Almost all members of the mini-chromosome maintenance (MCM) family, catalytic subunits of different DNA polymerases (POLA, POLE, POLD) and members of the replication factor C (RFC) family, which are involved in the initiation of eukaryotic DNA replication, were significantly down-regulated. In addition, known protumorigenic factors involved in cell cycle regulation, such as TTK (65), BIRC5 (66), CDK1 (67), and CDK6, CDC20 (68), CCNB1 (69) and BUB1B, were also significantly down-regulated. Among the up-regulated proteins, factors involved in the p53 signaling pathway (p = 6.86E-03) were significantly enriched, including several proteins encoded by known p53 target genes, such as BAX, CDKN1A, DDB2, SERPINE1, TIGAR, or TP53I3 (70) (supplemental Table S5). Surprisingly, we detected an increase in proteins involved in glycolysis and the TCA cycle, which was however less significant than the afore mentioned enriched KEGG groups DNA replication, cell cycle or p53 signaling pathway. Because the KEGG pathway analysis does not take into account the extent of expression changes in de novo protein synthesis, it is possible that significantly enriched KEGG groups include proteins that are above the chosen cutoff for differential expression (-0.3 ≥ log2 fold change ≥ 0.3) but only show relatively weak expression changes. Therefore it is not clear, whether the observed up- or down-regulation of enzymes associated with specific, over-represented KEGG categories actually leads to the activation of these pathways. Indeed, a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) for the differentially regulated proteins detected by pSILAC revealed that those proteins assigned to the KEGG pathway categories glycolysis and TCA cycle display a relatively weak induction when compared with the log2 fold changes of those proteins in the category p53 signaling pathway (data not shown).

RNA-Seq Analysis of Differential RNA Expression after p53 Activation

In total, 20,397 protein-coding mRNAs were identified by RNA-Seq (Fig. 1B). 11,801 showed robust expression levels (rpkm ≥ 0.5 in at least one condition) and were considered for further analysis. Among these, 415 were down-regulated (log2 fold change ≤ −1), whereas 1258 showed a significant up-regulation (log2 fold change ≥ 1) (Fig. 1B, for a complete list of RNAs see supplemental Table S6). The top 50 down- (all log2 fold change ≤ −3.30) and 50 up-regulated (all log2 fold change ≥ 5.36) mRNAs are shown in supplemental Tables S7A and S7B, respectively. A KEGG pathway analysis of the down-regulated mRNAs revealed down-regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway (p = 9.26E-03) (supplemental Table S8A). As expected, components of the p53 signaling pathway were enriched among the up-regulated mRNAs (p = 7.81E-04), including known p53 target genes, such as CDKN1A, MDM2, TP53I3, SERPINEB5, ZMAT3, or SERPINE1 (70) (supplemental Table S8B).

Next, we analyzed the expression of lncRNAs (including long intergenic noncoding (linc) RNAs, antisense RNAs and transcribed pseudogenes), which were also detected by RNA-Seq (Fig. 1C). Of the 4,608 detected lncRNAs, 1719 showed robust expression levels (rpkm ≥ 0.5 in at least one condition) and were considered for further analysis. Out of these, 270 showed induced (log2 fold change ≥ 1) and 123 repressed expression (log2 fold change ≤ −1). The top 50 down- (all log2 fold change ≤ −1.57) and 50 up-regulated (all log2 fold change ≥ 2.95) lncRNAs are shown in supplemental Tables S9A and S9B, respectively.

Next, we determined the overlap between the RNA-seq and pSILAC results and found that nearly all (93%) of the quantified proteins were also detected on RNA-level (Fig. 1D). Moreover, we determined that a subset of 130 genes was differentially regulated on both, the mRNA- and de novo protein synthesis-level. When we applied a low-stringency cutoff (-0.3 ≥ log2 fold change ≥ 0.3) for differential mRNA regulation the number of differentially regulated mRNAs that also display differential de novo protein synthesis increased from 130 to 636 (data not shown).

A cumulative distribution analysis of differentially expressed proteins showed a similar regulation on the mRNA level (p < 0.0001), substantiating a positive correlation between p53-induced changes in mRNA expression and de novo protein synthesis (Fig. 1E).

miR-Seq Analysis after p53 Activation

Next, we used miR-Seq to determine miRNA expression after activation of p53 for 16 h. ∼70 and ∼80% of the reads obtained from small RNAs isolated from SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV and SW480/pRTR cells, respectively, could be assigned to 21–22 nucleotide long miRNAs (supplemental Fig. S3A, S3B). In total, 411 different miRNAs were detected: 107 miRNAs were up-regulated (log2 fold change ≥ 1), whereas 101 were down-regulated (log2 fold change ≤ −1) by p53 (Fig. 1F). The top 50 up- (all log2 fold change ≥ 5.64) and 50 down-regulated (almost all log2 fold change ≤ −4.67) miRNAs are listed in supplemental Tables S10A and S10B, respectively (for a complete list of miRNAs see supplemental Table S11). As expected, we detected the induction of several, tumor-suppressive miRNAs known to be encoded by direct p53 target genes, such as miR-34a (22–26), miR-205 (71), members of the miR-200 family (miR-141/-141* and miR-200c/200c*) (72), as well as the miR-192 family (miR-192, −194 and −215) (73, 74) and miR-145 (17). Interestingly, several, putatively tumor-supressive miRNAs not previously linked to p53 were induced after p53 activation: e.g. miR-486–5p (75), miR-1266 (76) or miR-218 (77). Furthermore, we identified oncogenic factors among the down-regulated miRNAs, such as miR-25 and miR-92a (78) and the miRNA family miR-221/222, which is known to promote EMT (79).

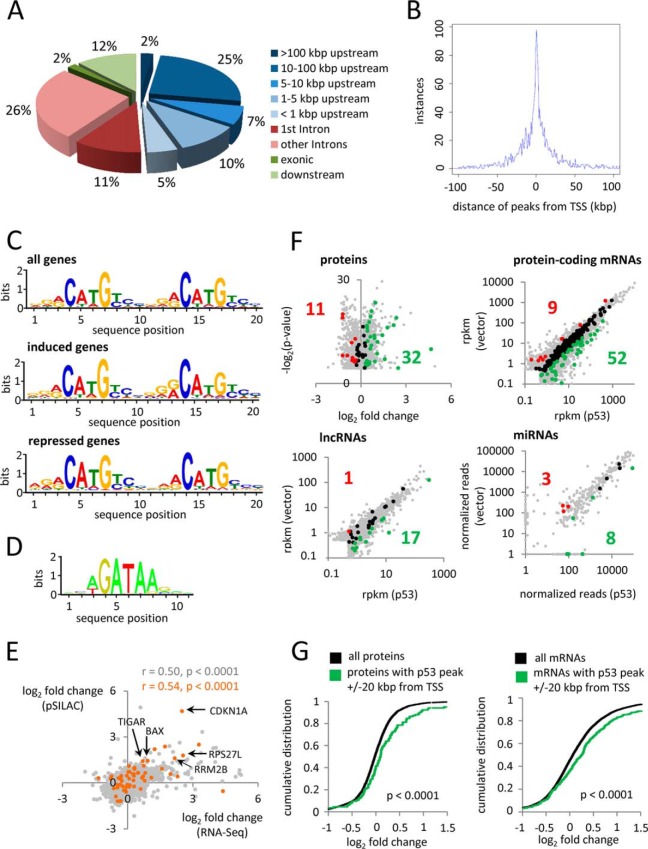

Genome-wide Mapping of p53 DNA-Binding

Next, DNA was isolated 16 h after addition of DOX by VSV-antibody mediated ChIP from SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV and, as a control, SW480/pRTR cells and subjected to NGS. In total, we identified 1827 ChIP-signals in the p53-inducible SW480 cell line of which 97% (1,771 signals) colocalized with a predicted p53 binding sequence (supplemental Table S12). 22% of the ChIP-signals with p53 binding sites were located in a region < 10 kbp from a transcription start site (TSS) and 27% were located > 10 kbp upstream of a TSS (Fig. 2A). 39% of the ChIP-signals with p53 binding site were found in intragenic regions and 12% were located downstream of genes. The ChIP signals that localized in a region within 100 kbp up- and down-stream from a TSS were centered around the TSS (Fig. 2B). When p53-derived ChIP signals 20 kbp up- and downstream of transcriptional start sites were analyzed for enriched binding motifs using MEME (49), the identified motif was identical to the previously described p53 consensus site (8, 9) and only minor differences between the motifs associated with p53-induced and -repressed genes were observed (Fig. 2C), which is in accordance with previous findings (15, 80). The motif associated with repressed genes showed a preference for A (instead of G) at position 1, 11, and 12, and a preference for C (instead of T) at position 18. However, the changes were restricted to the flanking sequences. A search for neighboring binding motifs of other transcription factors in the vicinity of the detected p53 ChIP-signals (± 250 bp) revealed an enrichment for the consensus motif WGATAR (W = A/T, R = A/G) of the GATA1 transcription factor that was present in 29% of the up-regulated genes harboring a p53 binding site (Fig. 2D). Therefore, it is possible that GATA factors and p53 cooperate in gene regulation.

Fig. 2.

Genome-wide analysis of p53 occupancy. ChIP-Seq analysis was performed with a VSV-specific antibody 16 h after addition of DOX to SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV and SW480/pRTR. A, Localization of called ChIP-peaks obtained after p53-ChIP in SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV. B, Distribution of p53-derived ChIP-Seq peaks 100 kbp up- and downstream of the TSS. C, MEME analyses of p53-derived ChIP-peaks in SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV (± 20 kbp of the corresponding TSS) associated with all genes, induced (log2 fc ≥ 1) and repressed (log2 fc ≤ −1) genes according to RNA-Seq. D, Enrichment of the GATA1 DNA binding motif in the vicinity of p53 ChIP-signals of induced genes detected by SpaMo. E, Scatter plot correlating changes in de novo protein synthesis of all differentially regulated proteins with the corresponding mRNA fold changes after induction of p53 (marked in gray). Molecules showing p53 occupancy near the respective gene promoter are indicated in orange. The respective Pearson correlation coefficient and statistical significance are indicated. F, Proteins, protein-coding mRNAs, lncRNAs and miRNAs that have an occupied p53 binding site within ± 20 kbp of the TSS of their host gene are shown in colors or black as described under Fig. 1. Molecules without promoter-proximal p53 binding are shown in gray. G, Cumulative distribution plot displaying expression changes of (left) p53-occupied, protein-coding genes compared with the normal distribution of all detected proteins as detected by pSILAC, (right) p53-occupied, mRNA-coding genes compared with the normal distribution of all detected mRNAs as detected by RNA-Seq.

By using the presence of a ChIP-Seq signal located in a region ± 20 kbp from the corresponding gene promoter as a criterion, we determined that changes in de novo protein synthesis of proteins showing p53 binding near the respective gene promoter positively correlated with the respective changes in mRNA abundance (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2E). Compared with the correlation of changes in de novo protein synthesis of all differentially regulated proteins to the respective mRNA fold changes (r = 0.50), the Pearson correlation coefficient was higher for direct p53 targets (r = 0.54), including several known p53-regulated target genes, such as CDKN1A, TIGAR or BAX. Among the differentially regulated candidates, we identified 43 putative direct targets via analysis of de novo protein synthesis (32 induced, 11 repressed) and 61 via differential mRNA expression (52 induced, 9 repressed) (Fig. 2F, for further details see supplemental Table S13 and S14). Among the putative direct targets, 14 genes were coregulated on the level of mRNA expression and de novo protein synthesis (marked in gray in supplemental Table S13 and S14). These results indicate that only 2.4% (1.9%) of the down-regulated mRNAs (proteins) showed a p53 ChIP-signal in a region of ± 20 kbp from the corresponding gene promoter, whereas 4.3% (5.8%) of the up-regulated mRNAs (proteins) displayed p53 binding near their corresponding gene TSS. A cumulative distribution analysis of those proteins/mRNAs showing a p53 peak in a region of ± 20 kbp from their corresponding gene promoter plotted against all detected proteins/mRNAs confirmed that genes bound by p53 are preferentially up-regulated (p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2G). These results indicate that a large number of the genes repressed by p53 are not regulated by direct p53 binding, but rather indirectly, e.g. by miRNA-mediated repression or because of secondary consequences of p53 activation.

In addition, we found 18 differentially expressed lncRNAs showing p53 binding near their corresponding gene TSS (Fig. 2F; for further details see supplemental Table S15). 17 induced lncRNAs (6.3% of all induced lncRNAs) displayed p53 chromatin occupancy in a ± 20 kbp region surrounding the corresponding gene TSS, whereas only one repressed lncRNA (0.8% of all down-regulated lncRNAs) showed p53 binding at the respective gene promoter. The previously described p53-induced lncRNA TP53TG1 (81, 82), but none of the other described lncRNAs regulated by p53, was among the p53-induced lncRNAs. Notably, we detected the lncRNA RP3–510D11.2 that is transcribed in the opposite direction from the previously described promoter of the p53 target gene miR-34a (22) to be induced and directly bound by p53 at the respective gene promoter (supplemental Fig. S4).

Next, we determined whether p53 binds in the vicinity of TSSs of genes encoding miRNAs (according to miRStart (83)) (Fig. 2F). Among the up-regulated miRNAs, miR-34a, miR-205, miR-34–3p, miR-1293, miR-145, miR-486–5p, miR-143, and miR-641 showed p53 binding near their corresponding gene promoter (7.2% of all differentially up-regulated miRNAs) (Fig. 2E, supplemental Table S16A). In addition, genes encoding the down-regulated miRNAs miR-3191, miR-3928 and miR-1908 displayed p53 binding (3.2% of all differentially down-regulated miRNAs) (Fig. 2F, supplemental Table S16B). Therefore, only a minor fraction of the detected differential miRNA regulations may be directly mediated by p53.

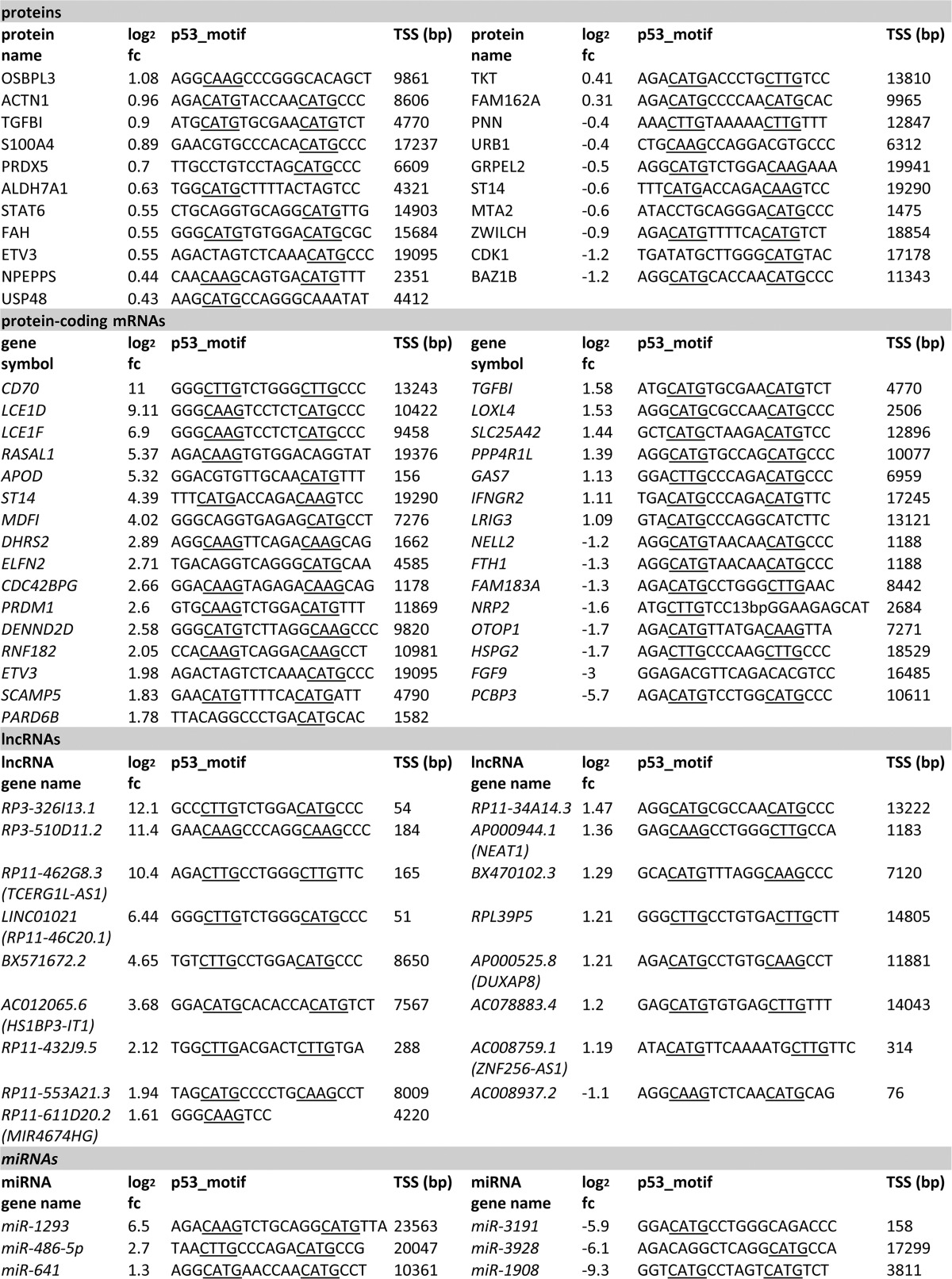

Identification and Confirmation of Novel Putative p53 Target Genes

Next, we compared the differentially regulated mRNAs and proteins with a p53 binding site in a region ± 20 kbp from the TSS of the corresponding gene with recent genome-wide studies of p53-mediated gene regulation (15, 80, 84, 85) (supplemental Figs. S5, S6, S7, S8). Thereby, we confirmed that 52 putative direct p53 targets, with 31 targets being identified by RNA-Seq and 21 by pSILAC, have not been characterized as p53 targets previously (Table I, for further information see supplemental Tables S17A and S17B, respectively). Interestingly, three of these novel p53 targets were identified by both approaches: ETV3, ST14 and TGFBI. In addition, we identified 17 differentially regulated lncRNAs and 6 differentially regulated miRNAs with p53 binding near their TSS that were not previously described as directly regulated by p53 (Table I, for further information see supplemental Tables S15 and S16, respectively).

Table I. Novel p53 target genes identified by RNA-Seq, pSILAC and ChIP-Seq. The table indicates 21 new direct p53 targets identified by pSILAC, 31 targets identified by RNA-Seq, 17 new p53-regulated lncRNAs identified by RNA-Seq (if available, the ENSEMBL gene name for the corresponding ENSEMBL gene ID is indicated) and six new p53-regulated miRNAs identified by miRNA-Seq in combination with ChIP-Seq. The log2 fold change of the respective target, the sequence of the p53 binding motif and its distance from the TSS (bp) are indicated.

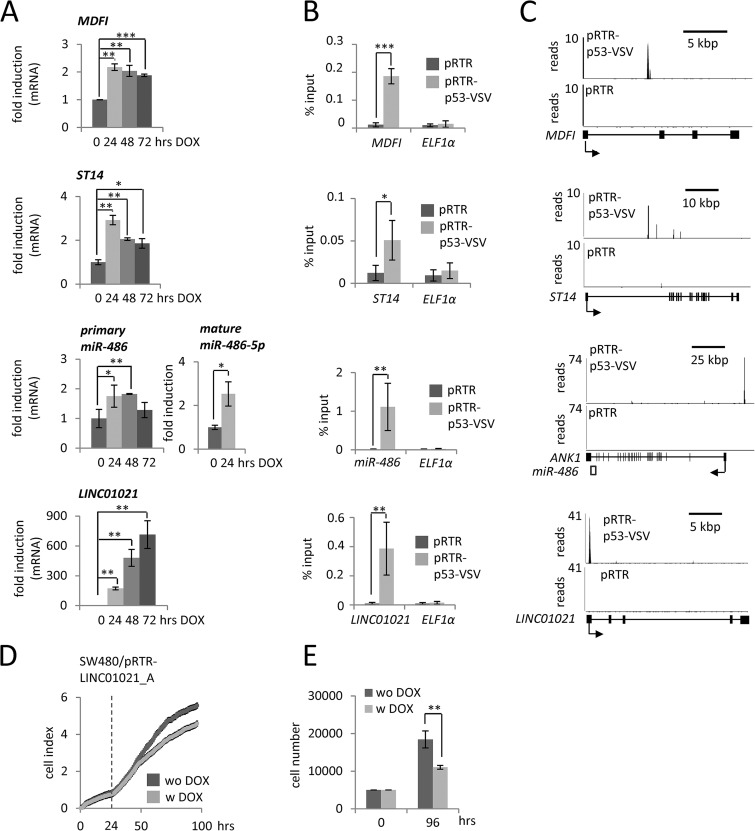

Subsequently, we used independent methods to confirm novel direct p53 targets. We could demonstrate the up-regulation of MDFI, ST14, LINC01021 (RP11–46C20.1), and miR-486 after ectopic p53-expression in the DOX-inducible cell line SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, MDFI, ST14 and LINC01021 showed an up-regulation after Nutlin-treatment in HCT116 p53+/+ but not in HCT116 p53−/− cells (supplemental Fig. S9A). Therefore, their up-regulation is p53-dependent. In addition, we confirmed p53 occupancy by qChIP analysis for MDFI, ST14, LINC01021, and miR-486 (Fig. 3B). These results were in line with the ChIP-Seq results as illustrated in Fig. 3C. A reporter assay showed that the isolated p53 binding site upstream of the miR-486 host gene ANK1 is indeed responsive to p53, providing further evidence for the direct regulation of miR-486–5p by p53 (supplemental Fig. S10A). Moreover, the induction of primary and mature miR-34a and miR-205 by p53 was confirmed by qPCR. In contrast to a previously identified p53 RE 1 kbp upstream of the gene encoding miR-205 (71), we validated a p53 binding site ∼17 kbp upstream of the miR-205 TSS (supplemental Fig. S10B–S10D). Because of its exceptionally pronounced induction after p53-activation, we further analyzed LINC01021. According to the ENSEMBL genome browser, the LINC01021 locus encodes six alternatively spliced transcripts (supplemental Fig. S9B). We introduced the longest transcript, LINC01021_A, into the DOX-inducible pRTR-vector and subsequently confirmed its prominent induction after treatment with DOX in SW480/pRTR-LINC01021_A cells (supplemental Fig. S9C). Notably, ectopic LINC01021_A expression after addition of DOX resulted in decreased proliferation as determined by realtime impedance measurement and cell counting (Fig. 3D, 3E), whereas addition of DOX had no effect on SW480/pRTR cells (supplemental Fig. S9D, S9E).

Fig. 3.

Exemplary validation of newly identified p53 target genes. A, qPCR analyses of MDFI, ST14, LINC01021 and miR-486 expression in SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV cells after addition of DOX for the indicated periods of time. B, qChIP validation of p53 occupancy at the MDFI, ST14, LINC01021 and miR-486 promoters in SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV after 16 h of DOX treatment and subsequent VSV-ChIP. C, p53-VSV-derived ChIP-Seq results are displayed using the UCSC genome browser. D, SW480/pRTR-LINC01021_A cell pools were subjected to impedance measurement. Twenty-four hours after seeding, DOX was added as indicated by the dotted line. E, Cell counting using trypan blue exclusion. Results in (A), (B), (D), and (E) represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

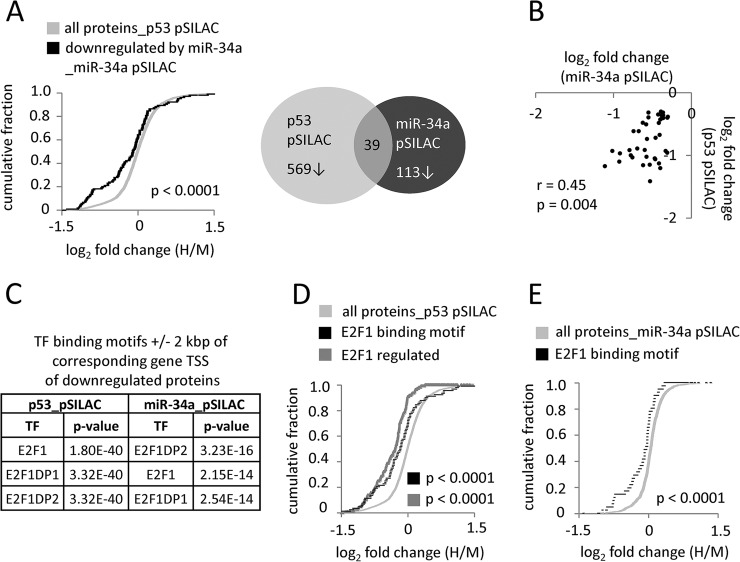

Comparison of p53 and miR-34a Effects on De Novo Protein Synthesis

Recently, we performed a proteome-wide analysis of miR-34a targets in the colorectal cancer cell line SW480 using the pSILAC method (28). When we compared the sets of down-regulated proteins from both analyses, a significant overlap was detected (Fig. 4A): Almost 35% of the proteins down-regulated in the miR-34a pSILAC analysis were also down-regulated after ectopic expression of p53 and the log2 fold changes of those coregulated proteins showed a significant, positive correlation (Fig. 4B, for a list of the coregulated proteins see supplemental Table S18A). Interestingly, almost all members of the MCM protein family, which mediate initiation of DNA replication, were among the coregulated proteins. Among these were only four direct miR-34a targets: MTA2, SURF4, TMEM109 and UCK2 (indicated with bold letters in supplemental Table S18A). Therefore, we determined whether the proteins down-regulated after p53 and miR-34a expression harbor common transcription factor binding motifs in a region ±2 kbp from the corresponding gene promoter using the Molecular signatures database (MSigDB) (86, 87) (Fig. 4C–4E). Interestingly, we found that the binding motif for the transcription factor E2F1 was significantly enriched among down-regulated proteins in both pSILAC-data sets (Fig. 4C, supplemental Table S18B), but not among the up-regulated proteins (data not shown). A cumulative distribution analysis of proteins with an E2F1 binding motif near their corresponding TSS (±2 kbp) revealed significantly decreased protein expression (p < 0.0001) when compared with the normal distribution of all proteins detected in the p53 pSILAC analysis (Fig. 4D). Using a data set of experimentally validated E2F1 regulated genes further supported this finding (Fig. 4D). It is known that E2F transcription factors are targeted by miR-34a (40, 88–90). Indeed, a cumulative distribution analysis of proteins with an E2F1 binding motif near their corresponding gene TSS (±2 kbp) revealed significantly decreased de novo protein synthesis (p < 0.0001) when compared with the normal distribution of all proteins detected in the miR-34a pSILAC approach (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, almost all members of the MCM protein family, that are known E2F target genes (91–94), were among the proteins coregulated by miR-34a and p53 (supplemental Table S18A). Therefore, it is possible that miR-34a indirectly contributes to a p53-induced cell cycle arrest by targeting E2F and thereby E2F target genes.

Fig. 4.

Overlap between changes in de novo protein synthesis after p53- or miR-34a-induction. A, Left: Cumulative distribution plot displaying p53-induced changes in de novo protein synthesis of 113 proteins down-regulated after induction of miR-34a compared with the normal distribution of all detected proteins (28). Right: Venn diagram displaying the overlap between proteins down-regulated (log2 fold change ≤ −0.3) after ectopic p53 and miR-34a expression. B, Scatter plot displaying the correlation of changes in de novo protein synthesis between proteins down-regulated by p53 and miR-34a. The Pearson correlation coefficient and statistical significance are indicated. C, Enrichment of E2F1, E2F1DP1 and E2FDP2 binding motifs in the promoters of genes encoding proteins down-regulated by p53 and miR-34a. pSILAC data sets were analyzed with the Molecular Signature database (MSigDB) at http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp. TF = transcription factor. D, Cumulative distribution plot displaying the p53-induced changes in de novo protein synthesis of proteins with E2F1 binding motifs in their gene promoters (in black) compared with the normal distribution of all detected proteins (in light grey). p53-induced changes in de novo protein synthesis of proteins positively regulated by E2F1 are displayed in dark grey. E, Cumulative distribution plot displaying miR-34a-induced changes in de novo protein synthesis of proteins with E2F1 binding motifs in their gene promoters compared with the normal distribution of all detected proteins. The E2F1 data sets V$E2F_Q6 (141) and E2F1_UP.V1_UP (142) for (D) and V$E2F1_Q3_01 for (E) were obtained at MSigDB.

miRNA-mediated Repression by p53

To assess the effect of miRNA-mediated repression after activation of p53, we performed a scan for targets of the p53-induced miRNAs (log2 fold change ≥ 1) among the differentially down-regulated proteins and mRNAs identified in this study by using a combination of the TargetScan and Pictar (59, 60) target prediction algorithms. Thereby, 284 predicted targets of the p53-induced microRNAs were identified among the down-regulated proteins (log2 fold change ≤ −0.3; pval ≤ 0.05) (supplemental Table S19). 37% (105) of these targets were also down-regulated on the mRNA level. In addition, we detected 203 putative targets that were regulated on mRNA-level only (supplemental Table S20). A KEGG pathway analysis of the 284 predicted targets using DAVID (61, 62) revealed a significant over-representation of miRNA-targets involved in DNA replication (p = 9.40E-07) and cell cycle progression (p = 6.80E-04), indicating that induction of miRNAs may contribute to inhibition of these processes by p53 (data not shown). Subsequently, we focused on the targets of the miRNAs miR-34a, -34c-3p, -145, -205, and -486–5p, which are directly induced by p53. Out of 77 putative miRNA targets with reduced de novo protein synthesis, 33 were repressed on both, the protein- and mRNA-level and 44 only on the level of de novo protein synthesis (Fig. 5A, 5B). In addition, we identified 51 repressed putative miRNA target mRNAs for which the corresponding protein could not be detected by pSILAC (Fig. 6). Among the identified targets, several were already shown to be regulated by one or several of the studied miRNAs, such as the miR-34a targets CDK6, MTA2, and YY1 (28) (underlined in Fig. 5, 6). None of the predicted conserved targets showed p53 enrichment in the ChIP-Seq analysis in the vicinity (± 20 kbp) of the respective gene promoter except for MTA2. Because MTA2 is a known target of miR-34a (28), this indicates that additional direct transcriptional repression by p53 may augment the miRNA-mediated down-regulation of this gene by a coherent feed forward regulation (95).

Fig. 6.

Putative targets of miRNAs directly induced by p53 with down-regulation of mRNA expression. Predicted miRNA targets are shown that are down-regulated only on the mRNA level. Known miRNA targets are underlined.

These results indicate that p53 indirectly down-regulates many genes on mRNA- and/or protein-level by inducing miRNAs on a genome-wide scale. Part of the miRNA-mediated repression is presumably mediated by enhanced mRNA degradation. However, ∼60% of the conserved miRNA targets are presumably not repressed on the mRNA level, but only on the level of de novo protein synthesis, indicating that miRNA-mediated translational repression may represent an important regulatory mechanism employed by p53.

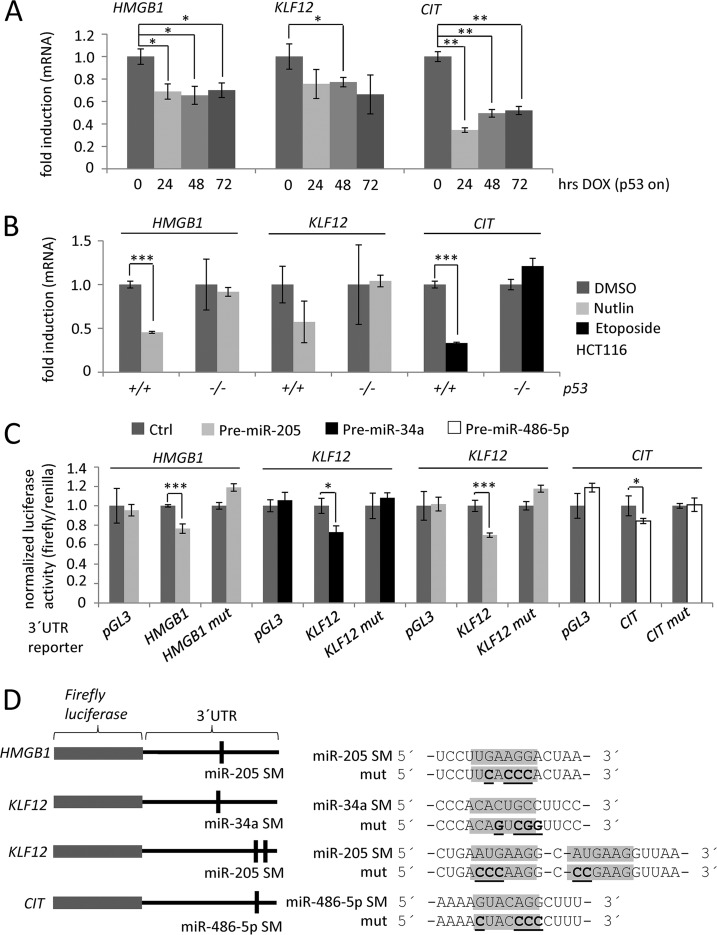

p53-Induced miRNAs Regulate Putative Prognostic Markers

Next, we focused on three factors that displayed down-regulation by p53, were putative targets of p53-induced miRNAs and had previously reported cancer-relevant functions. HMGB1, which was down-regulated on the mRNA level and showed reduced de novo protein synthesis after p53 induction (Fig. 5A), has a predicted conserved seed-match (SM) for miR-205 in its 3′-UTR (supplemental Fig. S11A) and a published SM for miR-34c-3p and miR-34a (96). KLF12 also showed a prominent down-regulation on mRNA-level (Fig. 6) and has predicted conserved SM for miR-34a and miR-205 (supplemental Fig. S11B). The citron rho-interacting serine/threonine kinase (CIT), which was also down-regulated on the mRNA level and showed reduced de novo protein synthesis (Fig. 5A), is a predicted target of the newly identified p53-regulated miRNA miR-486–5p (supplemental Fig. S11C). Down-regulation of HMGB1, KLF12, and CIT expression by p53 was confirmed on the mRNA level in SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV cells (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, all three genes were down-regulated after treatment with Nutlin or Etoposide in HCT116 p53+/+ but not in HCT116 p53−/− cells (Fig. 7B). Therefore, their repression by DNA-damage is p53-dependent. To confirm direct miRNA-mediated down-regulation of KLF12, HMGB1 and CIT, dual reporter assays were performed (Fig. 7C). 3′-UTR-reporters of KLF12, HMGB1, and CIT displayed a significant repression after cotransfection with the matching miRNA. Mutation of the seed-matching sequences in the 3′-UTRs abolished the miRNA-mediated repression in all cases (Fig. 7C, 7D). Therefore, the three selected miRNA targets represent direct targets of p53-induced miRNAs.

Fig. 7.

Validation of p53- and miRNA-mediated down-regulation. qPCR analysis of the indicated mRNAs after (A) addition of DOX to SW480/pRTR-p53-VSV cells for the indicated periods of time, (B) after treatment of HCT116 p53+/+ and p53−/− cells with Nutlin or Etoposide for 48 h. C, Dual reporter assays of H1299 cells cotransfected with the indicated miRNA mimics or controls and the indicated 3′-UTR constructs. D, Details of the mutant 3′-UTR reporter constructs. SM = seed-match. Results in (A), (B), and (C) represent the mean ± S.D. (n = 3).

We then asked whether up-regulation of any of the three miRNA targets occurs during tumor progression using expression data from collections of patient-derived tumor samples in the databases Oncomine (57), TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) (64) and PROGgene (58). Analysis of the Oncomine database (57) showed a significant up-regulation of HMGB1 in tumor versus normal tissue in 15 out of 20 different tumor entities, such as colon, pancreatic, prostate and invasive breast carcinoma (supplemental Fig. S12). Similarly, KLF12 was up-regulated in different tumor types, such as pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, invasive breast carcinoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, melanoma, T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and teratoma (supplemental Fig. S13A–S13F). When expression data of 424 colorectal tumors from TCGA were analyzed, a significant increase in KLF12 mRNA expression in those cases showing metastasis to distant organs (M1) compared with those without distant metastasis (M0) was detected (supplemental Fig. S13G). KLF12 mRNA expression was also significantly elevated in tumors with nodal status N2 compared with N0 and in advanced tumor stage IV versus tumor stage I. Furthermore, CIT mRNA expression was elevated in several tumor entities, such as colon, lung, breast, pancreas and gastric cancer (supplemental Fig. S14A–S14E). Interestingly, patients showing decreased expression of HMGB1, KLF12, and CIT had an increased overall and metastasis-free survival in two different colorectal cancer patient cohorts (supplemental Fig. S15A, S15B). In summary, these results suggest that HMGB1, KLF12 and CIT may represent clinically relevant prognostic markers. Moreover, the serine/threonine kinase CIT represents an interesting candidate for tumor therapeutic approaches, because its activity may be inhibited by small molecules.

DISCUSSION

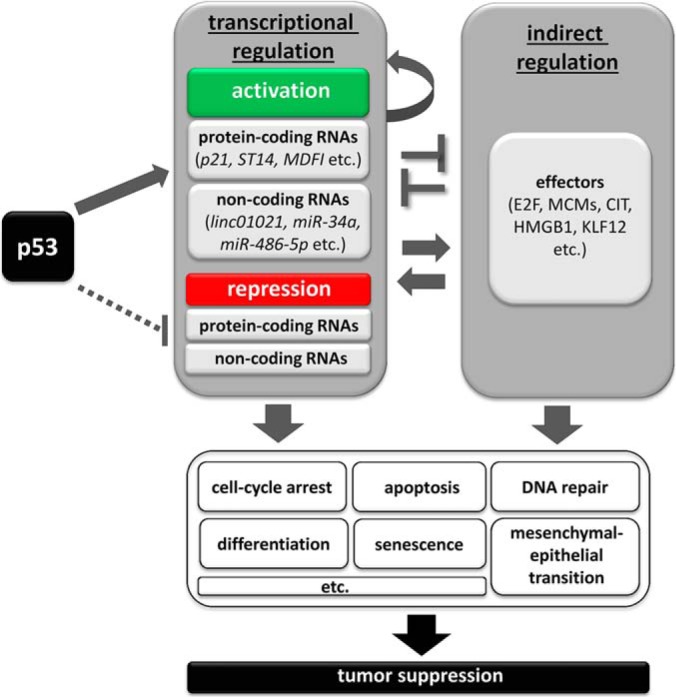

Here we demonstrate in a genome-wide screen combining pSILAC with RNA-, miRNA- and ChIP-sequencing that p53 mediates transcriptional and/or translational repression of numerous genes by directly inducing several miRNAs (summarized in Fig. 8). We found that the majority of the down-regulated genes show no promoter-proximal p53 binding, which indicates that they must be regulated via indirect, for example miRNA-mediated mechanisms. In fact, others and we have provided several examples of miRNA-mediated gene repression by p53 (2). By directly inducing miR-34a, p53 down-regulates genes with oncogenic functions like SNAIL (29, 72) or ZNF281 (31), thereby inducing MET (mesenchymal-epithelial transition). Furthermore, the transcriptional repression by p53 involves a combination of different mechanisms as we could show in this study for the known miR-34a target MTA2 (28). Apart from the miRNA-mediated repression by miR-34a, MTA2 also shows p53 occupancy in the vicinity of its transcriptional start site that may additionally mediate its repression. This indicates that the different mechanisms for p53-mediated repression are not mutually exclusive. This is also in accordance with previous studies showing that c-Myc is repressed by direct transcriptional repression by p53 as well as by miRNA-mediated mechanisms of the p53-induced miRNA miR-145 (17, 18).

Fig. 8.

Schematic model of effector pathways that mediate tumor suppression by p53. Upon activation, p53 regulates the transcription of mRNAs that encode proteins and/or non-coding RNAs, such as miRNAs and lncRNAs. p53 mainly acts as a transcriptional activator and to a minor extent as a transcriptional repressor. In addition, p53 indirectly regulates numerous effectors, for example E2F or MCM complex components via its direct target genes, such as p21 and miR-34a. Moreover, there is extensive crosstalk between direct and indirect p53 targets. The differential expression of direct and indirect p53 targets leads to the induction of specific cellular processes, such as cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, or mesenchymal–epithelial transition, which suppress mediate tumor progression.

Several genome-wide screens have been conducted in the past to identify p53-regulated gene expression (15, 80, 84, 85, 97–99). Similar to our results, more induced than repressed genes displayed promoter-proximal p53 binding (15, 80, 85, 99). In addition, the p53 binding motif associated with up- and down-regulated target genes only showed minor differences (15). Nikulenkov and colleagues proposed the following two different mechanisms of p53-mediated repression: The transcription factors E2F and IRF cooperate with p53 to mediate gene repression and p53 interferes with STAT3-mediated activation of genes by occupying overlapping binding sites at several promoters (15). Another study showed that distal enhancer activity might be important for p53-mediated repression in mouse embryonic stem cells (100). This shows that in addition to direct binding of p53 to p53 REs, many other indirect mechanisms are relevant for p53-mediated gene repression (reviewed in (11)). Our results demonstrate that the consensus binding motif of the GATA1 transcription factor is present in a significant number of promoters of genes bond and up-regulated by p53. Transcription factors of the GATA family activate and repress transcription of their targets and are known to have both, oncogenic and tumor-suppressive functions (reviewed in (101)). GATA1, for example, is known to control erythroid-specific genes but has also been observed to control cellular proliferation by silencing the proto-oncogenes Kit, Myc, and Myb during erythroid maturation (102–104). However, GATA1 may interact with the transactivation domain of p53 to inhibit p53′s function (105) and activate the expression of the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-xL in erythroid cells (106). Furthermore, the GATA1 motif is enriched near p53 REs in response to genotoxic stress (84). In addition, GATA3 has opposing functions that seem to be highly context-dependent. It partly reverses EMT in a breast cancer cell line by inducing E-cadherin and inhibiting N-cadherin and vimentin (107), but may indirectly increase the expression of Myc (108).

In our study we confirmed several p53 target genes that were already described to be directly regulated by p53, such as CDKN1A, BAX, DDB2, RPS27L, RRM2B, or SERPINE1. However, some known p53 target genes were not detected in our study. Because p53 target genes have different expression kinetics (109, 110), some direct targets might not have been detected at the specific time point selected in this study. Moreover, pSILAC might not detect all cellular proteins because insufficient labeling with Arg and Lys misses certain proteins. Recently, miR-205 was described as a p53-induced miRNA in a breast cancer cell line and a p53 RE 1 kbp upstream of the pre-miR genomic sequence was suggested (71). Here, we identifed a p53 binding sequence 17 kbp upstream of the miR-205 host gene in the colorectal cancer cell line SW480 and validated p53 occupancy at this motif. In addition, we identified miR-486 as a direct p53-induced target gene. This potentially tumor-suppressive miRNA has been shown to target the stem cell marker OLFM4 in gastric cancer (111) and ARHGAP5, a protumorigenic member of the RhoGAP family, in lung cancer (75), thereby negatively regulating tumor progression. The majority of miRNA-encoding genes with p53 binding in the vicinity of the promoter were induced, similarly to protein-coding genes and those coding for lncRNAs. We identified several putatively p53-regulated lncRNAs and determined an anti-proliferative effect of the newly identified p53 target LINC01021. The lncRNA lnc-H6PD-1, which is transcribed from the miR-34a promoter but in the opposite direction, was induced after p53 activation. This type of regulation is similar to the recently identified lincRNA-p21, which is located upstream of the p53 target gene p21/CDKN1A (112). Several studies suggest that lncRNAs have an important function in tumorigenesis (113). A recent genome-wide analysis unveiled a p53-specific lncRNA tumor suppressor signature in a colorectal cancer cell line (114). However, there is only a minimal overlap with our results, presumably because of different approaches and cell lines that were used. Interestingly, lncRNAs show a tissue- and tumor type-specific expression pattern, which may be advantageous for their use as biomarkers (115). For example, the lncRNAs PCA3 and HULC are used for the detection of prostate and hepatocellular carcinoma, respectively (116–118).

In addition, we characterized the citron rho-interacting serine/threonine kinase CIT as a target of the p53-induced miR-486–5p. It was shown before that knock-down of CIT in hepatocellular carcinoma cells significantly inhibits proliferation (119). Furthermore, CIT promotes cell growth in prostate cancer cells (120) and is overexpressed in ovarian carcinoma (121). In a recent study, CIT was shown to phosphorylate the GLI2 transcription factor, thereby activating a noncanonical hedgehog/GLI2 transcriptional program to promote breast cancer metastasis (122). Therefore, loss of p53-mediated suppression of CIT may promote tumor formation. Moreover, the serine/threonine kinase CIT is an attractive candidate for therapeutic inhibition by small molecules as previously shown for other serine/threonine kinases (123).

We also showed that HMGB1 is down-regulated by the p53-inducible miR-205. HMGB1 has been reported to fulfill important functions during cancer progression in many types of cancers, including colon, breast, lung or prostate cancer, by promoting invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, and inhibiting antitumor immunity (reviewed in (124, 125)) and represents a possible cancer therapeutic target (126). Uramoto et al. showed that p53 indirectly down-regulates HMGB1 expression by interacting with the transcription factor CTF2 (127). Furthermore, it has been shown that direct molecular interactions between HMGB1 and p53 regulates the balance between apoptosis and autophagy in colorectal cancer cells (128). In p53−/− cells, HMGB1 is required for autophagy and knockdown of HMGB1 results in increased apoptosis and decreased autophagy. Because autophagy is important for resistance to chemo- and radiation therapy, HMGB1 might represent an attractive therapeutic target in p53-deficient cells (129). Moreover, HMGB1 is down-regulated by the p53-inducible miR-200c in breast cancer cells (130) and by miR-34a in retinoblastoma cells (96). Here we provide an additional mechanism as to how HMGB1 expression may be down-regulated by p53 via miRNA-mediated mechanisms. In addition, the miRNA-34a/205 target KLF12 emerged as an interesting candidate for a use as a prognostic marker. Interestingly, ectopic expression of KLF12 promotes invasion, whereas its knockdown results in a growth arrest in human gastric cancer cells. Therefore, KLF12 may have oncogenic functions in gastric cancer progression (131).

Because p53 is inactivated late during colorectal cancer progression (132), increased expression of HMGB1, KLF12, and CIT in advanced tumor stages and/or in different tumor types in the TCGA and Oncomine databases is in accordance with our findings. It also suggests that miRNA replacement may be used as a therapeutic approach to treat advanced cancer in the future. Indeed, treatment with miR-34a mimics was successful in several preclinical studies (133–135) and has entered clinical phase I studies recently (136).

Several quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomic studies of p53-mediated regulations have been conducted previously (137–139). However, pSILAC was never applied to study de novo protein synthesis after p53 activation before. We have recently applied pSILAC after ectopic expression of miR-34a in colorectal cancer cells to comprehensively identify miR-34a-targets (28). As previously observed after miR-34a activation (28), changes in mRNA expression correlated with those in protein expression after p53 activation. Surprisingly, only four out of 36 putative miR-34a targets that were down-regulated in the miR-34a pSILAC screen were also identified as down-regulated proteins after p53 activation. This indicates that activation of p53 has numerous other effects on protein expression in addition to the activation of miR-34a. For example, p53 might induce competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) functioning as miRNA sponges, which may attenuate target repression by miR-34a (140). However, we found that a large number of the proteins down-regulated in the miR-34a pSILAC analysis were also down-regulated after ectopic expression of p53, including almost all members of the MCM protein family, which are important for the initiation of DNA replication. Interestingly, the E2F1 transcription factor binding motif was over-represented in the promoters of genes encoding the proteins down-regulated by both, miR-34a and p53. MCM proteins are induced by the E2F transcription factors, which are known targets of miR-34a (40, 88–90, 93). Taken together, this suggests that, in addition to p21-mediated suppression of E2F (16), miR-34a-mediated inhibition of the E2F pathway contributes to the cell cycle arrest induced by p53 via down-regulation of MCM proteins.

In conclusion, our results indicate that p53 indirectly down-regulates a large number of genes via the activation of miRNAs. The results add new insights into the p53-regulated network of gene expression. Furthermore, our results will promote further studies by providing numerous p53-regulated molecules and pathways that represent attractive candidates for biomarkers and/or therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Bert Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins Medical School, Baltimore) for providing cell lines and plasmids. We thank Bettina Knapp and Kurt Lobenwein for technical assistance in sample preparation and LC/MS analyses.

Footnotes

Author contributions: B.W. and H.H. designed research; S.H., F.D., S.O., A.D., and N.E. performed research; G.M. and B.W. contributed new reagents or analytic tools; S.H., M.K., F.D., S.O., T.B., F.E., A.D., N.E., C.C.F., G.M., R.Z., B.W., and H.H. analyzed data; S.H., M.K., and H.H. wrote the paper.

* This work was supported in the BW laboratory by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (TRR 130) and the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal & State Governments (EXC 294 BIOSS). The CCF group is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grants FR2938/1-1 and FR2938/1-2). FE and RZ are supported by BioSysNet and LMUexcellent. This study was supported by grants to HH from the DKTK (German Cancer Consortium), the GIF (German-Israeli-Science Foundation) and the Rudolf-Bartling-Foundation.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 to S15 and Tables S1 to S20.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1 to S15 and Tables S1 to S20.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- EMT

- epithelial–mesenchymal-transition

- BS

- binding site

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CRC

- colorectal cancer

- DOX

- doxycycline

- lncRNA

- long noncoding RNA

- miRNA

- microRNA

- SM

- seed-match

- ncRNA

- noncoding RNA

- NGS

- next generation sequencing

- pSILAC

- pulsed stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture

- RE

- response element

- TSS

- transcriptional start site

- UTR

- untranslated region.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vogelstein B., Lane D., Levine A. J. (2000) Surfing the p53 network. Nature 408, 307–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hermeking H. (2012) MicroRNAs in the p53 network: micromanagement of tumour suppression. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 613–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rokavec M., Li H., Jiang L., Hermeking H. (2014) The p53/microRNA connection in gastrointestinal cancer. Clin. Exp. Gastroenterol. 7, 395–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vousden K. H., Prives C. (2009) Blinded by the light: The growing complexity of p53. Cell 137, 413–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hollstein M., Sidransky D., Vogelstein B., Harris C. C. (1991) p53 mutations in human cancers. Science 253, 49–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Olivier M., Eeles R., Hollstein M., Khan M. A., Harris C. C., Hainaut P. (2002) The IARC TP53 database: new online mutation analysis and recommendations to users. Hum. Mutat. 19, 607–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bode A. M., Dong Z. (2004) Post-translational modification of p53 in tumorigenesis. Nat. Rev. 4, 793–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. el-Deiry W. S., Kern S. E., Pietenpol J. A., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1992) Definition of a consensus binding site for p53. Nat. Genet. 1, 45–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Funk W. D., Pak D. T., Karas R. H., Wright W. E., Shay J. W. (1992) A transcriptionally active DNA-binding site for human p53 protein complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 12, 2866–2871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Laptenko O., Prives C. (2006) Transcriptional regulation by p53: one protein, many possibilities. Cell Death Different. 13, 951–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rinn J. L., Huarte M. (2011) To repress or not to repress: this is the guardian's question. Trends Cell Biol. 21, 344–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang B., Xiao Z., Ko H. L., Ren E. C. (2010) The p53 response element and transcriptional repression. Cell Cycle 9, 870–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hoffman W. H., Biade S., Zilfou J. T., Chen J., Murphy M. (2002) Transcriptional repression of the anti-apoptotic survivin gene by wild type p53. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3247–3257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tokino T., Thiagalingam S., el-Deiry W. S., Waldman T., Kinzler K. W., Vogelstein B. (1994) p53 tagged sites from human genomic DNA. Human Mol. Gen. 3, 1537–1542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nikulenkov F., Spinnler C., Li H., Tonelli C., Shi Y., Turunen M., Kivioja T., Ignatiev I., Kel A., Taipale J., Selivanova G. (2012) Insights into p53 transcriptional function via genome-wide chromatin occupancy and gene expression analysis. Cell Death Different. 19, 1992–2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dimri G. P., Nakanishi M., Desprez P. Y., Smith J. R., Campisi J. (1996) Inhibition of E2F activity by the cyclin-dependent protein kinase inhibitor p21 in cells expressing or lacking a functional retinoblastoma protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 2987–2997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sachdeva M., Zhu S., Wu F., Wu H., Walia V., Kumar S., Elble R., Watabe K., Mo Y. Y. (2009) p53 represses c-Myc through induction of the tumor suppressor miR-145. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 3207–3212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ho J. S., Ma W., Mao D. Y., Benchimol S. (2005) p53-Dependent transcriptional repression of c-myc is required for G1 cell cycle arrest. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 7423–7431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bartel D. P. (2009) MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136, 215–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pillai R. S., Bhattacharyya S. N., Filipowicz W. (2007) Repression of protein synthesis by miRNAs: how many mechanisms? Trends Cell Biol. 17, 118–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]