Abstract

Retinoic acid signaling regulates several biological events, including myogenesis. We previously found that retinoic acid receptor γ (RARγ) agonist blocks heterotopic ossification, a pathological bone formation that mostly occurs in the skeletal muscle. Interestingly, RARγ agonist also weakened deterioration of muscle architecture adjacent to the heterotopic ossification lesion, suggesting that RARγ agonist may oppose skeletal muscle damage. To test this hypothesis, we generated a critical defect in the tibialis anterior muscle of 7-week-old mice with a cautery, treated them with RARγ agonist or vehicle corn oil, and examined the effects of RARγ agonist on muscle repair. The muscle defects were partially repaired with newly regenerating muscle cells, but also filled with adipose and fibrous scar tissue in both RARγ-treated and control groups. The fibrous or adipose area was smaller in RARγ agonist–treated mice than in the control. In addition, muscle repair was remarkably delayed in RARγ-null mice in both critical defect and cardiotoxin injury models. Furthermore, we found a rapid increase in retinoid signaling in lacerated muscle, as monitored by retinoid signaling reporter mice. Together, our results indicate that endogenous RARγ signaling is involved in muscle repair and that selective RARγ agonists may be beneficial to promote repair in various types of muscle injuries.

Skeletal muscles can be injured because of a variety of reasons, including overuse, trauma, infections, and loss of blood circulation. In general, skeletal muscles have adequate repair capacity and quickly recover to full functionality after minor injury. However, repair of severely damaged muscle is challenging and may not resolve completely, even after an extended period. This is especially true in elderly persons or in individuals with repetitive torn or ruptured muscle injury.1 As a consequence of incomplete repair, damaged muscles accumulate connective scar tissue, leading to tissue stiffness and future damage, and ultimately decreasing muscle functionality.2,3 Current therapies, such as massage, ultrasound,4 hyperbaric oxygen delivery, and pain relievers,5 are mostly palliative. Therefore, an effective treatment method needs to be developed. Several biological drugs, such as insulin-like growth factor-1 and myostatin inhibitors, which are potent inducers of myogenesis, are expected to improve muscle regeneration in systemic myopathies, including muscular dystrophy.6,7 These biological agents have been studied in clinical trials (eg, NCT01207908 for insulin-like growth factor-1) and may also facilitate muscle repair.8–10

Heterotopic ossification (HO) is a pathological bone formation that mostly occurs in the skeletal muscle. More than 10% of patients undergoing invasive surgeries11–13 and a staggering 65% of seriously wounded soldiers14 develop HO. Current treatment options are nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, steroids, or irradiation.3,15 These treatments are only partially effective and are accompanied by adverse effects. We have previously reported that retinoic acid receptor γ (RARγ) is the dominant RAR in the regulation of chondrogenesis and that pharmacological activation of RARγ effectively prevents HO.16 Interestingly, we have found that RARγ agonist not only blocks HO but also reduces deterioration of muscle tissue around HO, suggesting the potential role of RARγ in skeletal muscle damage.

Active vitamin A, retinoic acid (RA), has been known for decades to have profound effects on myogenesis.17,18 Most of its effects are mediated by nuclear RARs (α, β, and γ). On ligand binding, RAR forms a heterodimer with retinoid X receptors (α, β, and γ), binds to retinoic acid–responsive elements (RAREs), and regulates expression of target genes.19 In addition, RAR modulates other signaling pathways through protein-protein interactions, phosphorylation, and limiting availability of cofactors for other transcription factors.20 In the developing limb bud, RA plays an important role in recruiting muscle progenitor cells into the limb.21 Implantation of RA-soaked beads in the developing limb induces expression of muscle differentiation–related genes, such as Pax3, Myf-5, and myogenin, whereas application of citral, an inhibitor of RA signaling, down-regulates early myogenic genes.21 When undifferentiated limb bud mesenchymal cells are placed in culture, RA effectively blocks chondrogenesis and stimulated myogenesis.22 On the other hand, excess RA inhibits myogenic differentiation of limb bud cells or muscle precursor cells isolated from neonatal mice.23,24 Together, these observations indicate that RA has profound effects on myogenesis, and the level of the signaling activity must be tightly controlled. However, the specific roles of individual RAR isoforms on myogenesis have not been elucidated.

Our aim was to investigate the roles of RARs in skeletal muscle injury, and then to test whether RA or its derivatives can promote muscle repair and regeneration in vivo. The results indicate the importance of endogenous RARγ signaling in muscle repair and a potential therapeutic value of selective RARγ agonists for muscle injuries.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals

All experimental protocols involving the animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Jefferson Medical College and Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, PA). Adult 7-week-old female CD1 mice (Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were used for all experiments unless specified. For the induction of HO in mice, we used the mouse model of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) that carries a Cre-inducible constitutively active anaplastic lymphoma receptor tyrosine kinase (ALK)2Q207D mutant and enhanced green fluorescence protein.25 To induce HO, we injected 108 plaque-forming units/10 μL of Ad-Cre (Vector Biolabs, Malvern, PA) into the left tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of P7 ALK2Q207D mice to remove the floxed stop cassette and induce expression of mutant ALK2 gene (official name ACVR1) and then injected 10 μL of 0.3 mg cardiotoxin (C9759; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) to induce local inflammation in the limb.16 Retinoid signaling reporter mice [RARE-LacZ; (RARE-Hspa1b/lacZ)/12Jrt/J] were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME; stock number 008477).

RARγ-null mutant mice26 were kind gifts from Dr. Pierre Chambon (INSERM, Illkirch, France). Genotyping information for the mice listed above has been previously published.27

Cardiotoxin-Induced Muscle Injury Model

The TA muscle of 7-week-old mouse was surgically exposed after anesthesia by isoflurene inhalation, and 10 μL of 40 mmol/L cardiotoxin was injected into the center of the proximal 1/3 level in the TA muscle. The TA muscles were collected 2 weeks after injury, fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde, and subjected to histological analysis.

Critical Defect Muscle Injury Model

A round-shaped defect (1.5-mm diameter × 1.5-mm depth) was generated with thermal cautery (model 150I; Geiger Enterprises, Council Bluffs, IA) in a TA muscle of 7-week-old female CD1 mice. Mice were then randomly divided into two groups (six mice per group) and received either vehicle or retinoids three times by oral gavage. Unless indicated, mice received retinoids on days 5, 7, and 9 after surgery, and TA muscle tissues were collected 30 days after surgery and subjected to histological analysis.

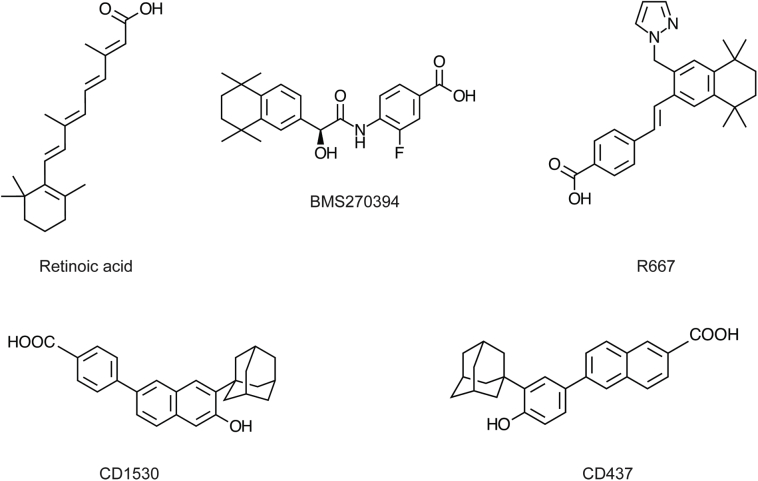

Retinoid Administration

Retinoic acid (all trans-retinoic acid, pan-RAR agonist, CAS 302-79-4) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (R2625). BMS270394 (RARγ agonist, CAS 262433-54-5)28 was obtained from Axon Medchem (Groningen, the Netherlands; Axon-1173). R667 (palovarotene, CAS410528-02-8)16,29 was synthesized at Atomax Chemicals (Shenzhen, China). NRX195183 (RARα agonist)30 was a kind gift from NuRx Pharmaceuticals (Irvine, CA). CD1530 (RARγ agonist, CAS 107430-66-0)31 and CD437 (RARγ agonist, CAS 125316-60-1)32 were purchased from Tocris Biosciences (Bristol, UK). The structure of NRX195183 has been shown previously16; structures of all other retinoids are shown in Supplemental Figure S1.

Stock solutions of retinoid were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (D2650; Sigma-Aldrich) and stored at −30°C under argon. Before administration, 30 μL of stock solution was mixed with 70 μL of corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich) for each dose, and delivered to mice by oral gavage. Vehicle control mice received 30 μL dimethyl sulfoxide plus 70 μL corn oil in the same manner. Control vehicle, R667, or CD1530 was administrated by oral gavage three times every other day starting at day 5 or day 8 after muscle injury surgery. This treatment regimen targets on the time point when granulation tissue actively grows and injured muscle tissues are actively remodeling. For the FOP mouse experiment, retinoid treatment was started 3 days after Ad-Cre/cardiotoxin injection. Mice received either vehicle or 4 mg/kg CD1530 every other day until the end of the experiment.

Histological Analysis

To analyze quality of muscle repair, we prepared serial transverse or longitudinal sections (8 μm thick) of TA muscles, and stained with Masson's trichrome, according to manufacturer's protocols (Sigma-HT15; Sigma-Aldrich). Images of sections every 100 μm were analyzed by Image-Pro software version 7.0 (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD). Masson's trichrome stains muscle, adipose, and fibrous tissues in red, white, and blue, respectively. The amount of pixels of each colored area within 9 × 9 grids (approximately 3 × 3 mm) that includes the original injured site was quantified separately. The artificial space that was generated during tissue processing was manually subtracted from the defined 9 × 9 grid area to define total area. The ratio of each tissue component (pixel)/the total area (pixel) was then calculated. To optimize the image analysis procedure, we first inspected all images, identified the most severely damaged region, and preliminarily analyzed injured sites in two different ranges: three sections covering a 200-μm distance [the section that has the most severely damaged region and two additional sections (100-μm apart from the first section)] and nine sections covering an 800-μm distance [the section that has the most severely damaged region and eight additional sections (every 100-μm apart from the first section)]. Either analysis condition (three and nine sections) provided similar results. Therefore, we analyzed three images (the most severely damaged area in the 200-μm range) per sample. To ensure objectivity of the experimental results, all image analysis was performed in a double-blinded manner (A.D.R., K.U., M.I.).

Immunostaining

After deparaffinization, slides were washed in phosphate-buffered saline and blocked in 10% goat serum in phosphate-buffered saline. Primary antibodies [anti-laminin 2, ALX-804-190 (Enzo Life Science, Farmingdale, NY), 1:250; anti-osteocalcin, M173 (Takara, Otsu, Japan), 1:500] were applied overnight at 4°C. The secondary antibodies were applied for 1 hour and followed by counterstaining with 0.2 μg/mL of DAPI in phosphate-buffered saline for 10 minutes. Primary antibodies were detected with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) and anti-rat Alexa Fluor 488–coupled secondary antibodies raised in goat (Molecular Probes, 1:500). To detect phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8, slides were treated in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 90°C for 10 minutes, blocked in 10% goat serum, and then incubated with anti-pSmad1/5/8 antibody (number 9511S; Cell Signaling, Danvars, MA; 1:200 in 1% goat serum) for overnight at 4°C. After washing, immunoreactivity was detected by the ImmPACT Novared Kit (model SK-4805; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Real-Time PCR

Injured TA muscle tissues were collected and soaked in the RNAlater solution (AM7020 Ambion; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The total RNA was reverse transcribed using an RT first-strand kit (330401; Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The quantification of target gene mRNA was performed by real-time PCR using SYBR Green (Life Technologies). The primer sequences are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Primer Sequences Used in This Study

| Gene | Primer sequences | Product size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

|

RARA (NM_009024) |

F: 5′-GAAAAAGAAGAAAGAGGCACCCAAGC-3′ R: 5′-AGGTCAATGTCCAGGGAGACTCGTTG-3′ |

183 |

|

RARB (NM_011243) |

F: 5′-AATGCTGGCTTCGGTCCTCTGACT-3′ R: 5′-GCTTGCTGGGTCGTCGTTTTCTAATG-3′ |

217 |

|

RARG (NM_011244) |

F: 5′-ATGGATGACACCGAGACTGGGCTACT-3′ R: 5′-CCTTTCTGCTCCCTTAGTGCTGATGC-3′ |

222 |

|

RXRA (NM_011305) |

F: 5′-CTATGGGGTATACAGTTGTGAGGG-3′ R: 5′-AGAATCTTCTCTACAGGCATGTCC-3′ |

270 |

|

RXRB (NM_001205214) |

F: 5′-CGTGATAACAAAGACTGTACAGTGG-3′ R: 5′-GATGTTAGTCACTGGGTCATTTGG-3′ |

294 |

|

RXRG (NM_001159731) |

F: 5′-AAAGATCTCATCTACACCTGTCGG-3′ R: 5′-GAGGGTGAAAAGTTGCTTATCTGC-3′ |

336 |

|

Aldh1a1 (NM_013467) |

F: 5′-GCGTGGTAAACATTGTCCCTGGTTA-3′ R: 5′-GGGGTCAGAGGATTTCCAAGAACATA-3′ |

363 |

|

Aldh1a2 (NM_009022) |

F: 5′-AATCCAGCCACAGGAGAGCAAGTG-3′ R: 5′-CACGGTGTTACCACAGCACAATGC-3′ |

446 |

|

Aldh1a3 (NM_053080) |

F: 5′-AAGAGCAGGTCTACGGGGAGTTTGTG-3′ R: 5′-GCTTTGTCCAGGTTTTTGGTGAACAC-3′ |

384 |

|

Cyp26a1 (NM_007811) |

F: 5′-GCACAAGCAGCGAAAGAAGGTGATT-3′ R: 5′-GGAAGAGAGAAGAGATTGCGGGTCA-3′ |

278 |

|

Cyp26b1 (NM_001177713) |

F: 5′-GGCAATCTTTTTCCTCTCTCTCTTCG-3′ R: 5′-AACCAGTGACCAGTCTCTCCGATGAG-3′ |

385 |

|

Crabp1 (NM_013496) |

F: 5′-GCCAAGACGGGGATCAGTTCTACA-3′ R: 5′-CGCCAAATGTCAGGATTAGCTCATC-3′ |

239 |

|

Crabp2 (NM_007759) |

F: 5′-TCTAAAGAGAAAGCCACCTTGCTGC-3′ R: 5′-CGTCATCTGCTGTCATTGTCAGGAT-3′ |

413 |

F, forward; R, reverse.

LacZ Staining

β-Galactosidase (LacZ) activity in the TA muscles of RARE-LacZ mice was detected by Specialty Media βGal Staining kits (Millipore, Billerica, MA). We followed the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical significance of all experiments was determined by two-way factorial analysis of variance, followed by Bonferroni post hoc multiple comparison tests (Prism 5; GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

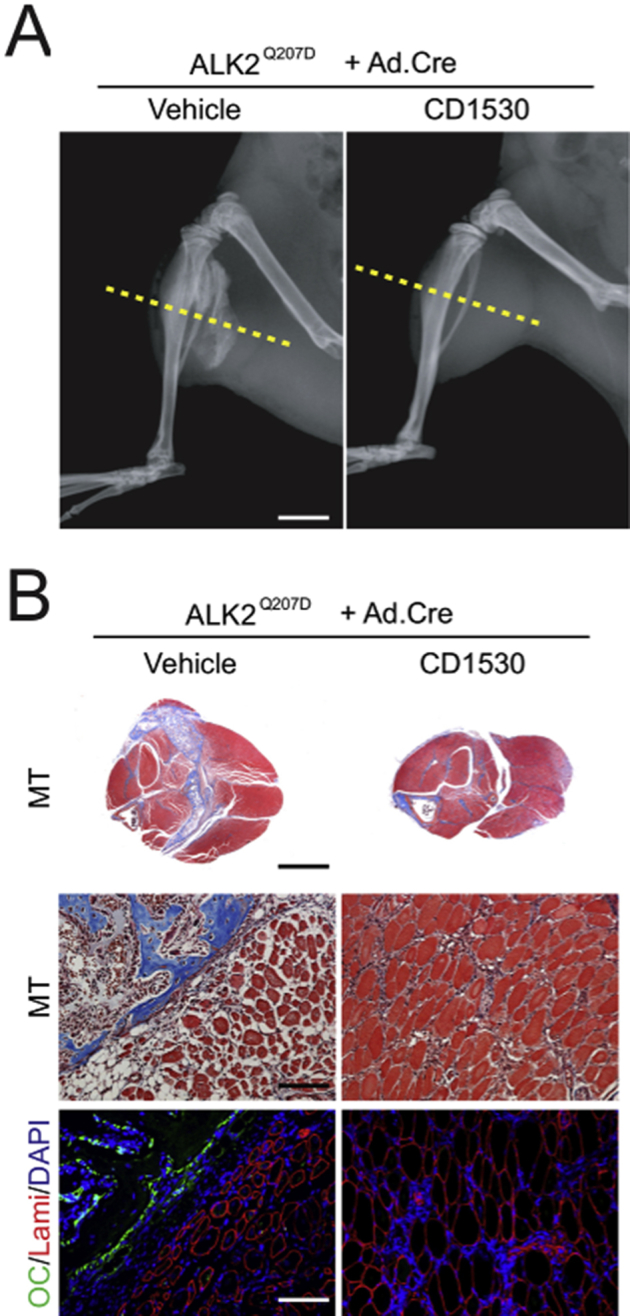

Selective RARγ Agonist Inhibits Deterioration of Skeletal Muscle in FOP Model Mice

We have recently reported that among the retinoid agonists, selective RARγ agonists block HO in several different HO mouse models, including the FOP model.16 In the FOP mouse model, vehicle-treated mice showed disturbance of the limb motility within a few weeks after HO induction, and X-ray analysis revealed massive HO formation (Supplemental Figure S2A). In contrast, limb movement of RARγ agonist (CD1530) treated mice was normal, and the X-ray image of their hind limbs had little or no evidence of HO (Supplemental Figure S2A). When we examined histology of HO in these mice, we observed that the skeletal muscle around HO lesion heavily deteriorated in vehicle-treated mice (Supplemental Figure S2B). In the RARγ agonist-treated group, disorganization of skeletal muscle tissue was much milder, although not completely normal (Supplemental Figure S2B). Parallel sections stained with anti-laminin antibody to outline the periphery of muscle fibers clearly showed differences in diameter of the muscle fiber and fiber integrity between vehicle-treated and RARγ agonist–treated samples (Supplemental Figure S2B). There are at least two potential mechanisms by which RARγ agonist benefits skeletal muscle. First, RARγ agonist might indirectly prevent muscle degeneration by blocking HO because HO disturbs motion of the limb, leading to atrophy of skeletal muscle. Second, RARγ might directly affect skeletal muscle cells and/or other supporting cells in the muscle and have a beneficial action on repair of skeletal muscle damage caused by HO formation. We tested the latter possibility in the following experiments.

RARγ Agonist Promotes Repair of Severely Wounded Skeletal Muscle

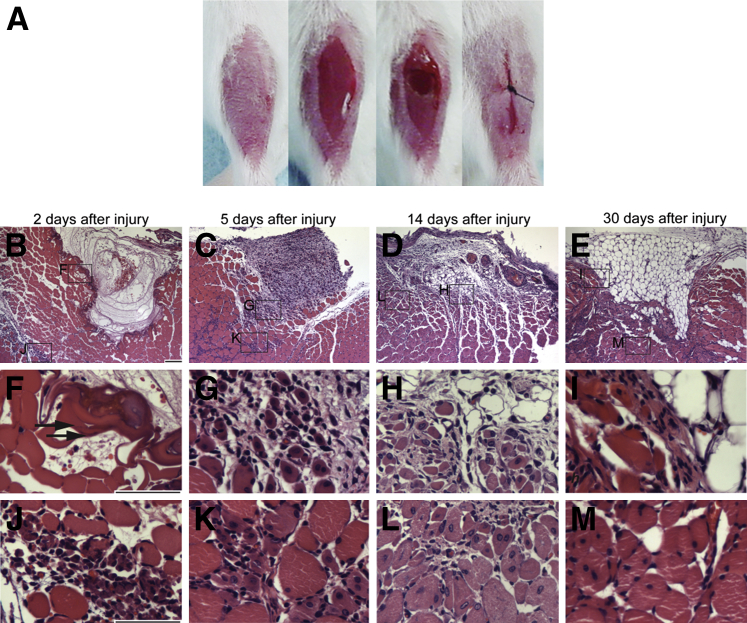

To determine whether RARγ agonist promotes repair of injured skeletal muscle, we developed a critical muscle defect model. By using a thermal cautery, we generated a round-shaped defect (approximately 1.5-mm diameter with 1.5-mm depth) in the TA muscle (Figure 1A). We collected injured muscle tissues at different time points after surgery and analyzed histology (Figure 1, B–M). Two days after injury, the defect was filled with exudate and blood cells (Figure 1B). The periphery of the defect was intensely stained with hematoxylin and eosin, presumably because of coagulation of proteins caused by burn injury (Figure 1F). Some muscle fibers around the defect were necrotic because they have no nuclei and typical sarcomere structure (Figure 1F). Infiltration of inflammatory cells, including leukocyte and plasma cells, was also noted (Figure 1J). Five days after surgery, the defect was filled with granulation tissue (Figure 1C). Inflammatory cell infiltration was spread between muscle fibers (Figure 1, G and K). Fourteen days after surgery, the defect was filled with a mixture of granulation and adipose tissues (Figure 1D). Immature muscle fibers appeared as characterized by presence of central nuclei (Figure 1, H and L), indicating the muscle tissue was actively remodeling and regenerating. Thirty days after surgery, the defect was mostly filled with adipose tissue (Figure 1E). Fibrous tissue was observed around the defect (Figure 1I), and immature muscle fibers were still evident (Figure 1M). At the same time point, Masson's trichrome staining of longitudinal sections showed that muscle damage was widespread and expanded along muscle fibers (Supplemental Figure S3, A–D). The defect was not restored completely for at least 2 months in three of three samples (Supplemental Figure S3E), indicating that this injury model is a critical defect model.

Figure 1.

Critical defect muscle injury model. A: Macro images of surgical procedure for critical muscle defect injury. Tibialis anterior (TA) muscle was exposed after removal of hair and skin incision. A round defect (1.5 × 1.5 mm) was then generated by a thermal cautery, and the skin was closed by suture. B–M: Histology of injured muscle after surgery. Transverse sections of injured TA muscles were prepared 2 (B, F, and J), 5 (C, G, and K), 14 (D, H, and L), and 30 (E, I, and M) days after surgery and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. F–M: Magnified images of the boxed areas in B–E. Arrows in F indicate coagulated area. Scale bars: 100 μm (B–E); 50 μm (F–M).

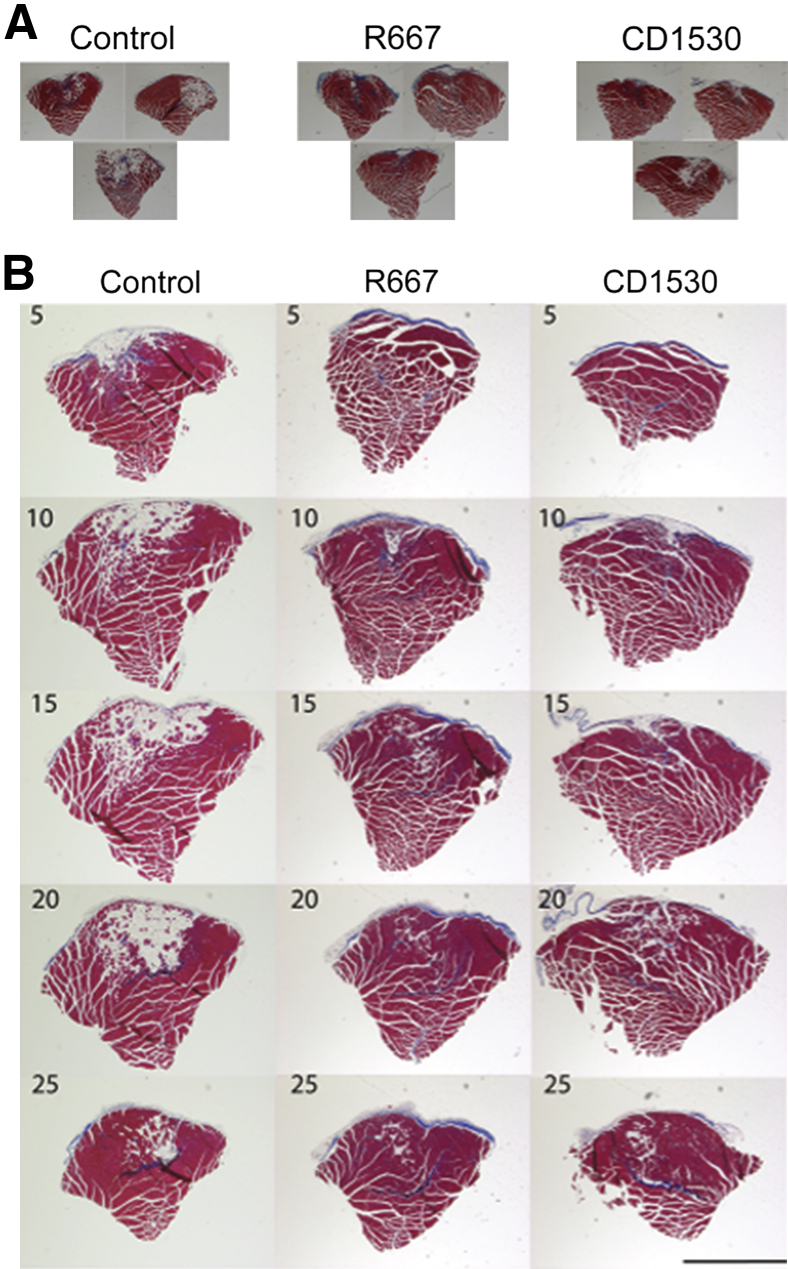

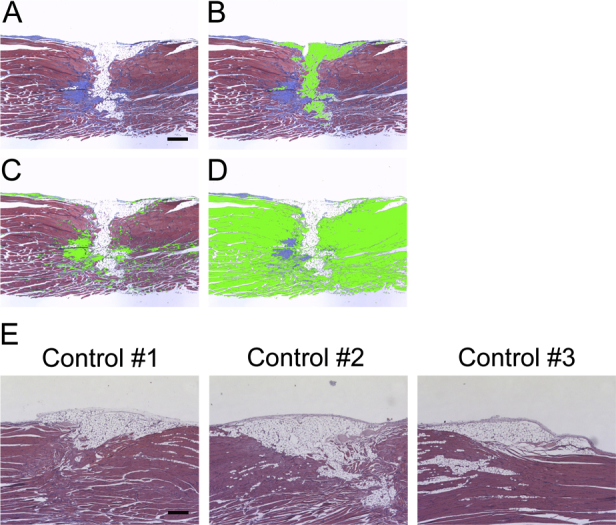

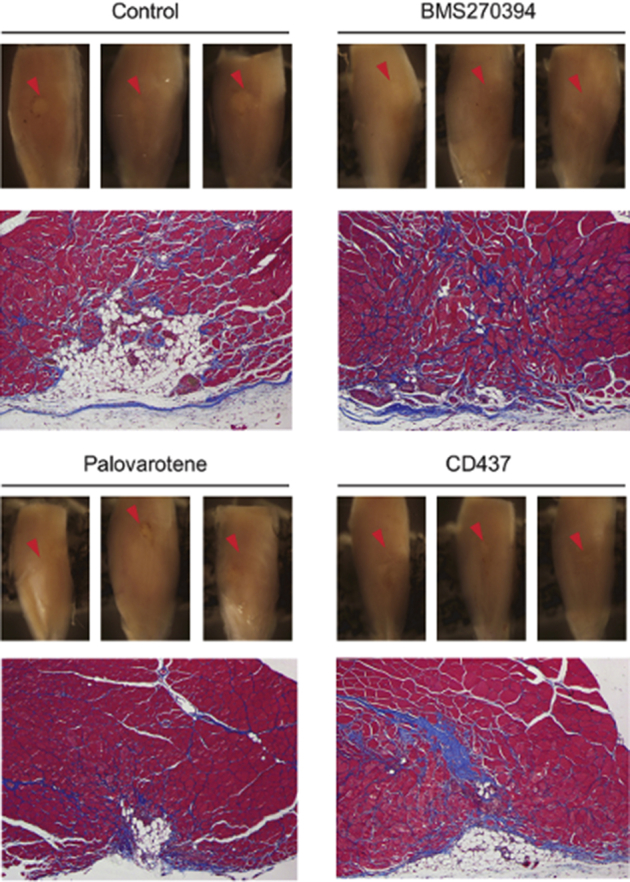

We used this experimental muscle injury model and examined the effects of selective RARγ agonists. We generated critical muscle injury in 7-week-old mice, randomly divided into three groups (six mice per group) and then treated with control vehicle, R667, or CD1530 by oral gavage at days 5, 7, and 9 after operation. This treatment regimen targets on the time point when granulation tissue grows and injured tissue is actively remodeling (Figure 1). Both R667 and CD1350 are RARγ agonists that have different back structures (Supplemental Figure S1). TA muscles were harvested 30 days after injury, fixed, and processed for histological analysis. Figure 2A shows the representative transverse sections of TA muscles (three independent samples per group) that contain the center portion of the initial defects. In the control, the defect region was largely replaced by adipose and fibrous tissues. In R667- or CD1530-treated groups, the initial defect region was still identifiable, but the average size of fibrous or adipose tissue looked smaller than those in control. Inspection of serial transverse sections revealed that extension of muscle degeneration area along the longitudinal axis of the muscle and such expansion was less in RARγ-agonist–treated groups (Figure 2B). By using the same injury model, we further examined the effects of additional selective RARγ agonists that have different backbone structures (Supplemental Figure S1). Operated on mice were treated with vehicle (control), R667, BMS270394, or CD437 on days 5, 7, and 9, and then analyzed 30 days after surgery (Supplemental Figure S4). The initial defect region in the control TA muscles was clearly visible as a demarcated scar, and the histology showed that the region is largely occupied by adipose tissue. In contrast, the scar tissue in the operated on region in all three RARγ agonist–treated groups was smaller and sometimes not visible in the macro images (Supplemental Figure S4). Because multiple RARγ agonists with different structures exhibit similar effects, we conclude that the promotion of muscle repair is mediated by RARγ.

Figure 2.

The effects of retinoic acid receptor γ (RARγ) agonists on muscle repair in a critical defect muscle injury model. Critical defect muscle injury surgery was performed in 7-week-old female CD1 mice (six mice per group). Mice were then randomly divided and treated with vehicle, 4 mg/kg per gavage CD1530, or 4 mg/kg per gavage R667 on days 5, 7, and 9 after surgery. Muscle tissues were collected from vehicle (Control)-, R667-, and CD1530-treated mice 30 days after critical defect injury surgery. A: Representative images of transverse sections of muscles. Images that contain the largest defect were determined by visual inspection of serial sections. Three independent samples from three separated mice per group are shown. B: Representative serial transverse sections (every five slides) of muscles. The number in the upper corner indicates slide number. The interval of every five slides is approximately 1 mm. The muscle defects were mostly replaced with the mixture of fibrous and adipose tissues. The area occupied with fibrous or adipose tissue was smaller in the RARγ agonist-treated sample than that of control. We repeated the experiments three times and obtained similar results. Scale bar = 1 mm (B).

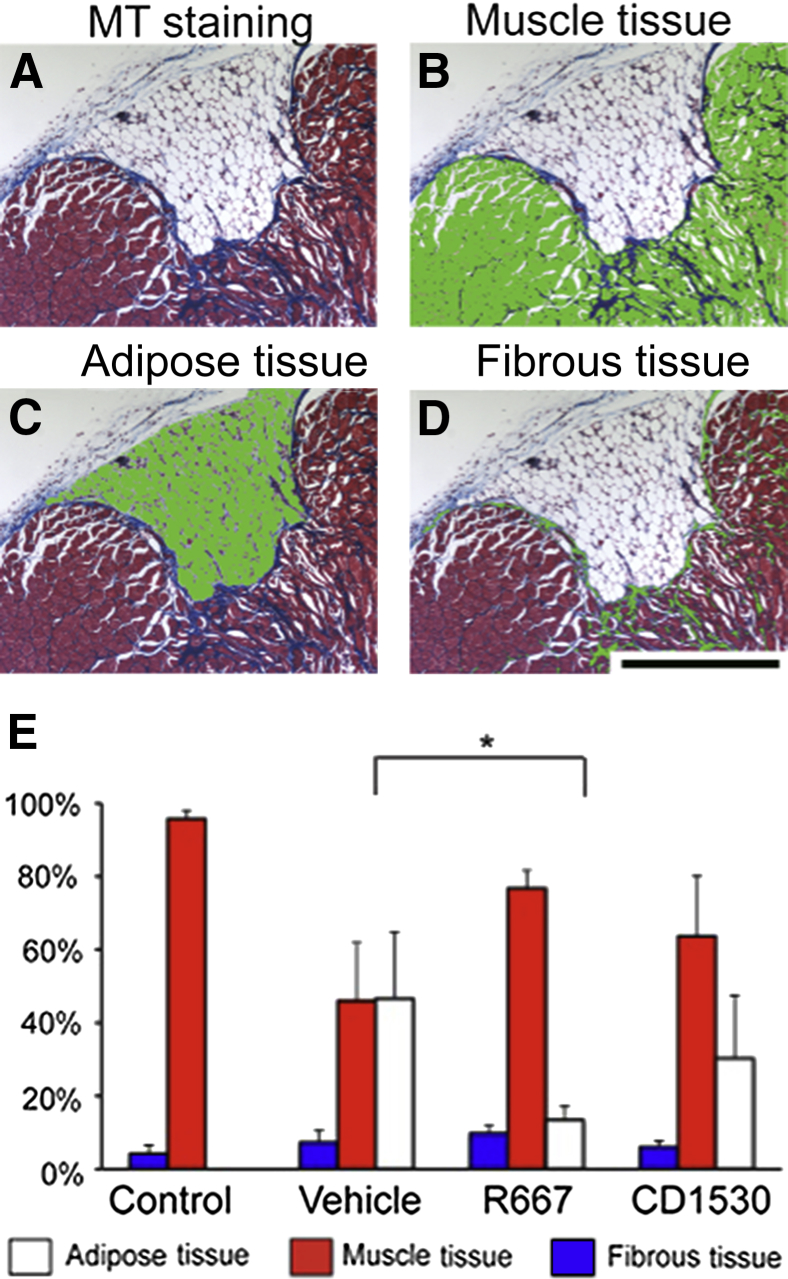

To quantify the results, we performed histological image analysis. Masson's trichrome staining stained muscle, adipose, and fibrous tissues in different colors (Figure 3A). We selected each color, manually removed artificial space that was generated during the tissue processing, and measured number of pixels per defined area using Image-Pro version 7.0 (Figure 3, B–D). The composition of adipose, muscle, and fibrous tissues among uninjured, vehicle-treated control, and RARγ agonist–treated groups was compared (Figure 3E). Uninjured muscle tissue was composed of nearly 95% muscle fibers and a small percentage of adipose and fibrous tissues. The vehicle-treated group contained approximately 45% of adipose tissue and 10% of fibrous tissue. The tissue composition of the RARγ agonist–treated sample was not the same as that of uninjured muscle, but the ratio of adipose tissue was 15% and significantly lower in the R667 group, and 30% in the CD1530 group (Figure 3E). The results indicate that RARγ agonist treatment improves the quality of muscle repair.

Figure 3.

Histological analysis of injured muscles treated with retinoic acid receptor γ agonists. Muscles collected from vehicle (Control)-, R667-, and CD1530-treated mice in Figure 2 were subjected to Masson's trichrome staining, followed by histological analysis. A: Image of Masson's trichrome (MT) staining. Muscle, adipose, and fibrous tissues were stained in red, white, and blue, respectively. B–D: Muscle (B), adipose (C), and fibrous (D) tissues were separately selected using Image-Pro software version 7.0. Each tissue was highlighted in green. E: Composition of adipose, muscle, and fibrous tissues in uninjured muscle (Control) or injured muscles treated with vehicle (Vehicle), CD1530, or R667. We analyzed three transverse sections covering the most severely damaged region (200-μm distance) and obtained an average value of composition for each sample. Uninjured control muscle (five mice per group) and injured muscles (six mice per group) were analyzed. Values are means ± SD (E). ∗P < 0.05. Scale bar = 0.5 mm (A–D).

The Effects of Other Retinoids on Muscle Repair in the Skeletal Muscle Injury Model

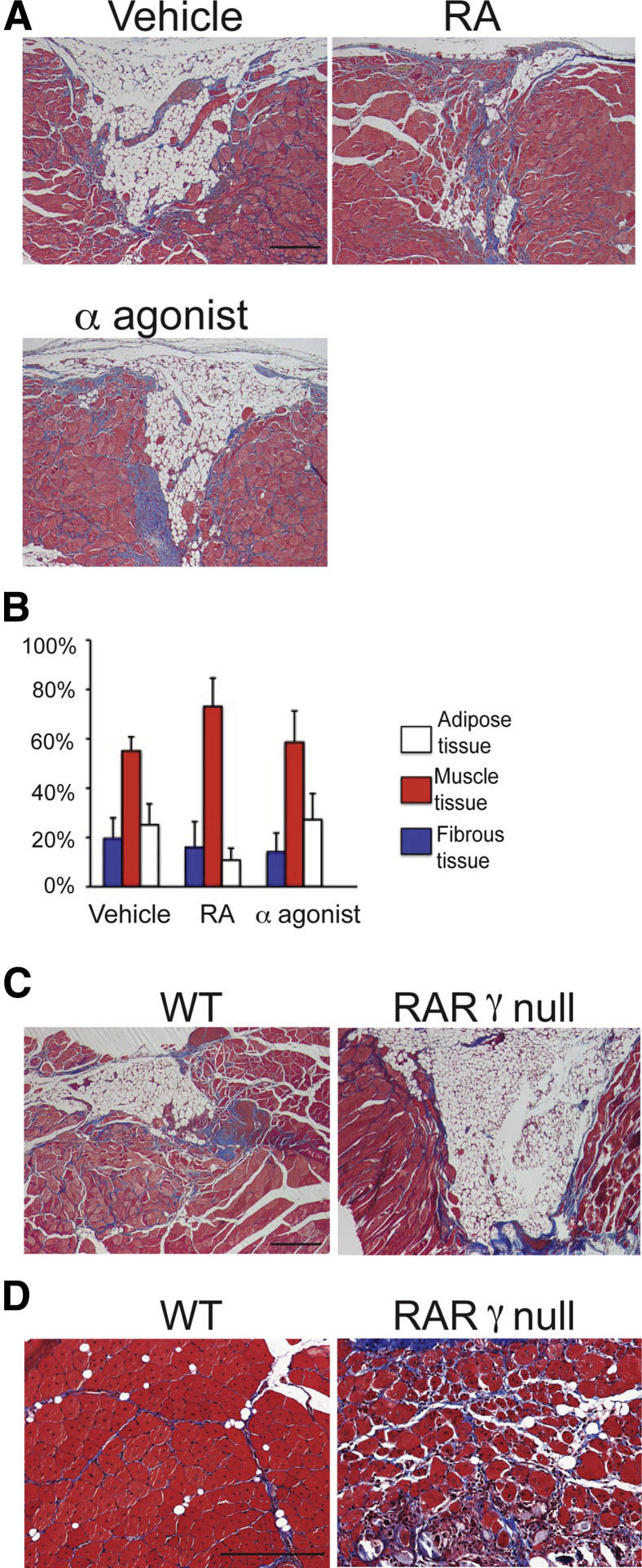

To test the specificity of RARγ signaling to the muscle repair, we examined the effects of RA and RARα agonist NRX195138 using the same muscle injury model. RA showed improvement of muscle repair in some mice (Figure 4A), whereas RARα agonist did not stimulate the repair at all (Figure 4A). Histological analysis revealed that both RA and RARα agonist did not significantly change the composition of muscle, adipose, and fibrous tissues in the injured site (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

The effects of retinoic acid (RA) and RA receptor α (RARα) agonist on muscle repair. A and B: Critical defect muscle injury surgery was performed in 7-week-old female CD1 mice (four mice per group). Mice were then randomly divided and treated with vehicle, 4 mg/kg per gavage RA, or 12 mg/kg per gavage RARα agonist (NRX195183) on days 5, 7, and 9 after surgery. A: Injured tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of vehicle, RA, and RARα agonist groups were harvested 30 days after injury and stained with Masson's trichrome. B: Compositions of adipose, muscle, and fibrous tissues were analyzed. C: Critical defect muscle injury surgery was performed in wild-type (WT) and RARγ-null mice. Sections of injured muscles were prepared 30 days after surgery and stained with Masson's trichrome. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments. D: WT and RARγ-null mice (three mice per group) received cardiotoxin injection in TA muscles. Sections of TA muscles were prepared 2 weeks after injection and stained with Masson's trichrome. Muscle repair process was remarkably delayed in RARγ-null mice. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments. Values are means ± SD of four samples (B). n = 3 (C). Scale bars: 0.5 mm (A, C, and D).

To verify the contribution of RARγ signaling in skeletal muscle repair, we injured TA muscles of wild-type (WT) or RARγ-null mice using the critical injury model or the cardiotoxin injection model. In the critical defect injury model, we observed reduction of the initial defect in the WT mice, whereas the size of the initial defect was largely unchanged in the RARγ-null mice (Figure 4C). In the cardiotoxin injury model, the damaged area in the WT mice was fully restored by immature muscle myofibers that had central nuclei in 2 weeks (Figure 4D). In contrast, the repair process was delayed in RARγ-null mice, as evident by the persistence of granulation tissue (Figure 4D).

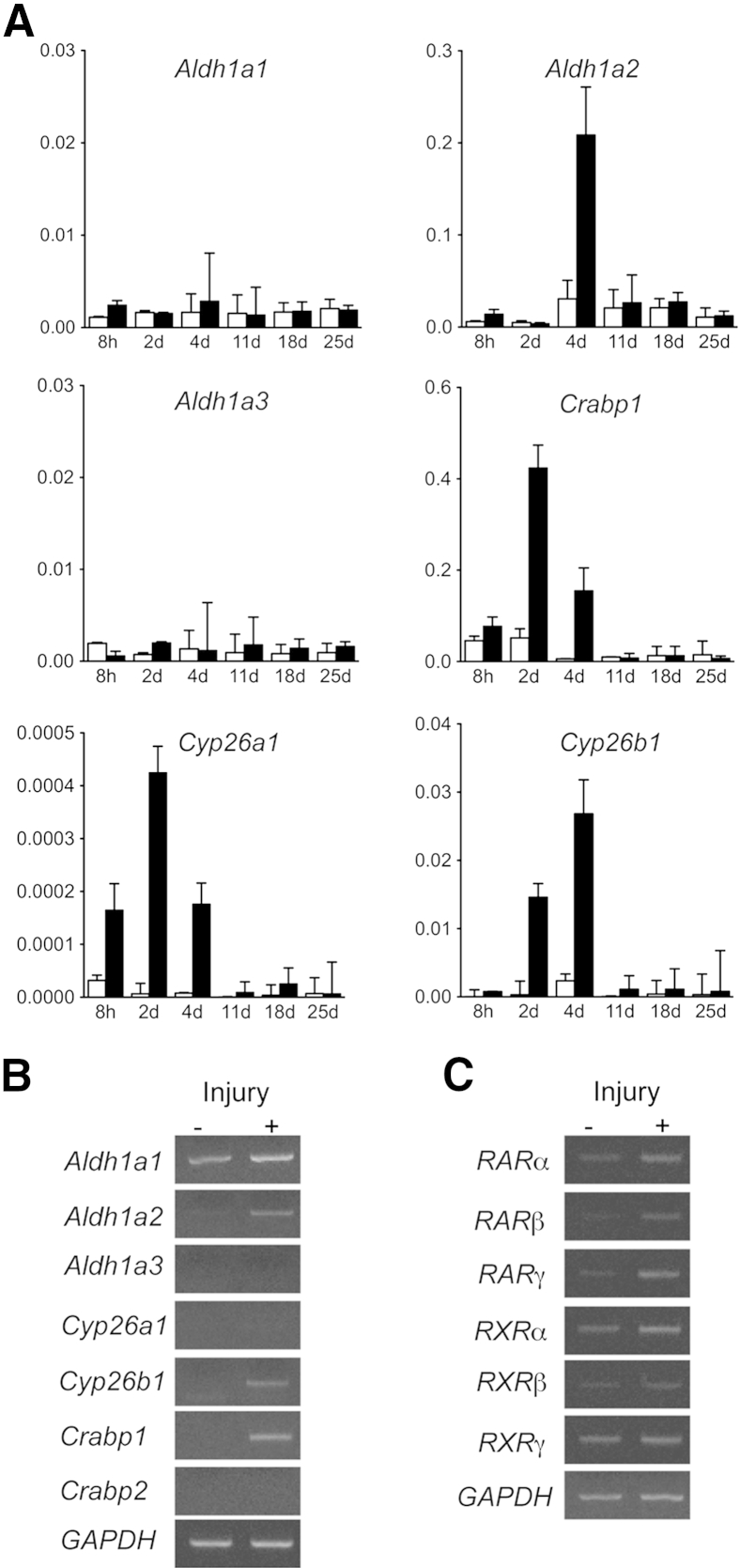

Involvement of Retinoid Signaling in Muscle Repair

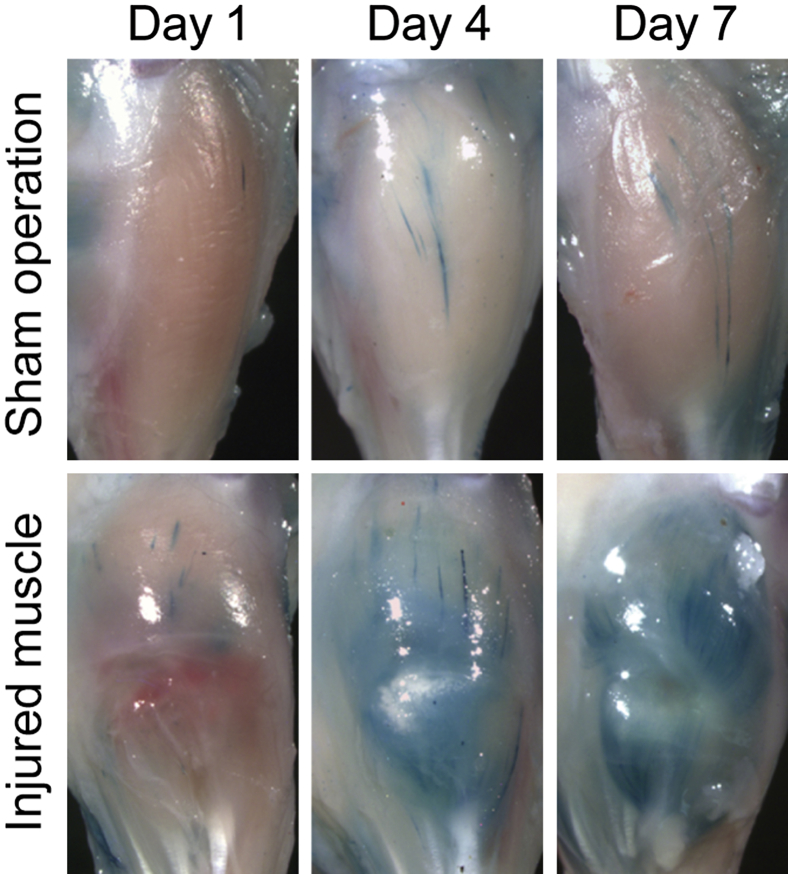

In the last set of experiments, we examined if retinoid signaling is active during the muscle repair process. We made an incision in the TA muscle in retinoid signaling reporter mice (RARE-LacZ mice)33 and monitored the LacZ reporter activity after muscle injury (Figure 5). In the sham-operated on mice that received skin incision but no muscle injury, we barely detected LacZ activity. In the injured muscle, LacZ activity was not detected 1 day after surgery, but was markedly up-regulated 4 and 7 days after surgery. A blue streak observed on day 4 in the sham-operated on group was probably because of the damage accidentally generated at the time of skin incision. We also collected injured and control muscle tissues after muscle injury and analyzed expressions of retinoid metabolism-related genes: Aldh1a1, Aldh1a2, and Aldh1a3 genes encode enzymes required for biosynthesis of RA; Crabp1 encodes an RA binding protein; and Cyp26a1 and Cyp26b1 encode enzymes that metabolize RA. In the sham-operated on group, expression levels of these genes were low and did not change through the experiment. In the injured muscle, we first detected up-regulation of Crabp1, Cyp26a1, and Cyp26b1, and then observed an increase in Aldh1a2 gene expression. The results indicate that local RA metabolism is activated at the early stage of the muscle repair process. The specificity of primers used in real-time quantitative PCR was confirmed by regular PCR (Figure 6, A and B). We also analyzed expression of RARs and retinoid X receptors. The results showed that gene expression of RARs, but not retinoid X receptors, was up-regulated in injured muscle tissue 4 days after surgery (Figure 6C).

Figure 5.

Up-regulation of local retinoid signaling after muscle injury. Lacerated muscle injury surgery (injured muscle) or sham surgery (only skin incision, sham operation) was performed in RARE-LacZ mice (three mice per group), as described previously.34 Muscles were collected 1, 4, and 7 days after surgery and subjected to LacZ staining. Similar results were obtained in all three mice.

Figure 6.

Gene expression of retinoic acid metabolism–related molecules and receptors in injured and intact skeletal muscle. Lacerated muscle injury surgery (injury+, black column) or sham surgery (only skin incision, injury−, white column) was performed in 7-week-old CD1 mice (four mice per group). Muscles were harvested 8 hours and 2, 4, 11, 18, or 25 days after surgery (A) or 4 days after surgery (B and C). Total RNAs were prepared from the muscles, reverse transcribed, and subjected to real-time PCR (A) or conventional PCR (B and C). A: Changes of gene expression of retinoic acid (RA) metabolism–related enzymes after muscle injury. Graph shows relative expression levels of indicated genes to sham-operated on sample: Aldh1a1, Aldh1a2, and Aldh1a3 encode enzymes for RA biosynthesis; Crabp1 encodes an RA-binding protein; Cyp26a1 and Cyp26b1 encode enzymes that metabolize RA. B: PCR products generated with the primers that were used for real-time PCR. The results indicate specificity of these primers. C: PCR analysis of gene expression of RA receptors (RARs) in uninjured (injury−) and injured muscle (injury+). Values are means ± SD of four samples (A). d, days; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; h, hours; RXR, retinoid X receptor.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated the role of retinoid signaling in the muscle repair process and demonstrated that the selective RARγ agonist promotes muscle repair in the critical defect muscle injury model. We also observed that skeletal muscle regeneration was markedly delayed in RARγ-null mice compared with WT mice. To our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating that pharmacological activation of RARγ promotes repair of injured skeletal muscle.

The results obtained from the analysis of RARE-LacZ mice revealed that local retinoid signaling is barely detectable in the intact TA muscle tissue but remarkably increased 4 days after injury (Figure 6). In parallel experiments, we examined retinoid-metabolism–related gene expression and observed up-regulation of Cyp26a1 and Cyp26b1 in the first 4 days after injury, followed by an increase of Aldh1a2 gene expression (Figure 6). The results indicate that local retinoid signaling is initially down-regulated after muscle injury and then up-regulated. The treatment regimen in this study targets on the time point when granulation tissue grows, injured muscle tissues are remodeling and regenerating (Figure 1), and injured muscle tissues show a high activity of retinoid signaling (Figure 5). We still do not know whether RARγ agonists stimulate muscle repair when administrated at earlier or later stages. In the future, it is important to study the efficacy of RARγ agonists on muscle repair at different time points, monitoring changes in retinoid signaling precisely.

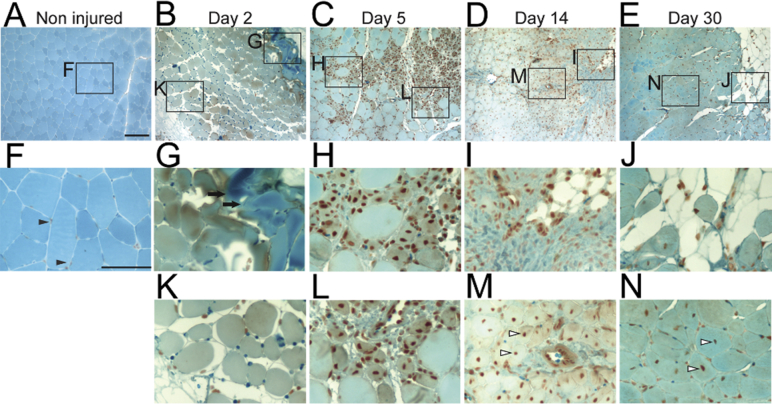

It has been shown that bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) expression increases after muscle injury.35,36 We also observed an increase in BMP signaling in injured muscle tissue, as determined by immunohistochemical staining with anti-pSmad 1,5,8 antibody (Supplemental Figure S5): a few satellite cells were pSmad1,5,8 positive in intact TA muscle, as previously reported.37 The number of satellite cells and infiltrated inflammatory cells positive to pSmad1,5,8 remarkably increased by day 5 after surgery and gradually decreased over time; and pSmad1,5,8-positive immature muscle cells were evident 14 and 30 days after surgery. Thus, both retinoid and BMP signaling are greatly changing during muscle repair.

Several reports have shown the biological antagonism between RA and BMP,38–40 and we have reported that RARγ, in particular, inhibits canonical BMP receptor signaling by decreasing Smad phosphorylation.16,41 From this standpoint, we think the biphasic change of local retinoid signaling may be suitable for muscle repair. The initial down-regulation of local retinoid signaling would reduce interference on BMP action by retinoid and facilitate proliferation of muscle progenitor cells.36 In addition, up-regulation of BMP signaling would facilitate recruitment of inflammatory cells that are required for tissue repair in general.42,43 On the other hand, higher RA signal is favorable for muscle cell differentiation, as shown in multiple reports.44–46 In addition, RARγ signaling has been reported to suppress adipogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stromal cells.47 Such an effect might also be a part of the mechanism for the improvement of the quality of muscle repair. Furthermore, RARγ signaling may be antagonizing BMP signaling in injured muscles, which would reduce the risk of HO in muscle.

As mentioned earlier, RARγ regulates cell function through regulation of target genes and modulation of other signaling pathways, including BMP and Wnt signaling.40,41 Because these signaling pathways are all essential for cellular function, it is difficult to clarify the entire mechanism of RARγ action and to define the relative contribution of each mechanism during muscle repair. More comprehensive approaches will be required to understand RARγ action at the cellular level; the proteomics approach might be useful to identify RARγ-interacting proteins, and RNA sequencing and chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing will be required to identify RARγ target genes.

RARγ agonists are small hydrophobic molecules and have several advantages over biological agents. As long as the compounds are protected from light and oxygen, RARγ agonists are stable, and the cost of production may be relatively low. Similar to steroids, they can be administered orally, in a tablet form, or locally, in an ointment form. One RARγ agonist, R667, has been tested in the phase 2 clinical trial for the treatment of the chronic lung disease, emphysema; therefore, drug safety is not an issue for this compound. Moving toward clinical trial, we have to thoroughly characterize the mechanism of action of RARγ in skeletal muscle and also optimize the treatment regimen. The efficacy of the drug should also be confirmed in large animals. Nevertheless, we believe that selective RARγ agonists will be effective drugs for the treatment of severe muscle injury and degeneration.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Kengo Shimono (Okayama University Graduate School of Medicine, Dentistry and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Okayama, Japan) for providing protocols and technical advice for experimental muscle injury models; and Drs. Pierre Chambon and Norbert Ghyselinck (INSERM, Illkirch Cedex, France) for providing retinoic acid receptor γ–null mice.

M.I. directed the project. A.D.R. and M.I. wrote the manuscript. A.D.R. and K.U. performed mouse operation and treatments and gene expression analysis. C.L. and R.B. analyzed histology. E.R.B. provided expertise on muscle biology. All authors analyzed data.

Footnotes

Supported by The Muscular Dystrophy Association grant MDA255541 and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, NIH, grant AR056837.

Disclosures: M.I. received compensation from Clementia Pharmaceutical Company for consulting services. M.I. is one of the inventors named on a related patent application “Composition and Method for Muscle Repair and Regeneration” (application 20140303223). Thomas Jefferson University, the author's former institute, has licensed this technology to Clementia. M.I. received a share of royalty payments from Thomas Jefferson University. NRX195183 was provided by NuRx Pharmaceuticals (Irvine, CA).

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.05.007.

Supplemental Data

Supplemental Figure S1.

Chemical structures of retinoids used in this study.

Supplemental Figure S2.

Retinoic acid receptor γ (RARγ) agonists block fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP)–like heterotopic ossification and skeletal muscle deterioration. A: X-ray images of hind legs of FOP-like model mice 1 month after induction of mutant activin receptor (ALK2Q207D) treated with vehicle or 4 mg/kg per gavage of RARγ agonist CD1530. Massive heterotopic ossification (HO) forms in control vehicle–treated mice but not in RARγ-treated mice. B: Transverse sections at the indicated level (yellow lines in A) in the X-ray images were stained with Masson's trichrome (MT). Skeletal muscle tissue severely distorts around HO in the vehicle-treated control mice, whereas deterioration of muscle tissues is much milder in the RARγ-treated group. Parallel sections (OC/Lami/DAPI) were stained for osteocalcin (OC; green), laminin (Lami; red), and nucleus (DAPI; blue). Scale bars: 5 mm (B, top panels); 250 μm (B, middle and bottom panels).

Supplemental Figure S3.

Histology of longitudinal sections of injured muscles after critical defect muscle injury. Critical defect muscle injury surgery was performed in 8-week-old CD1 mice. Injured muscles were harvested 30 days (A–D) or 60 days (E) after surgery. A–D: Longitudinal sections of injured muscles were stained with Masson's trichrome. Muscle, adipose, and fibrous tissues were stained in red, white, and blue, respectively. Muscle (B), adipose (C), and fibrous (D) tissues were separately selected using Image-Pro software version 7.0. Each tissue was highlighted in green. E: Longitudinal sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The initial defect regions are not fully repaired even after 2 months in three independent samples (controls 1 to 3). Scale bars: 0.1 mm (A–E).

Supplemental Figure S4.

The effects of various retinoic acid receptor γ (RARγ) agonists on muscle repair. Critical defect muscle injury surgery was performed in 7-week-old female CD1 mice. Mice were then randomly divided and treated with vehicle or selective RARγ agonists (BMS270394; 4 mg/kg per gavage), R667 (palovarotene; 4 mg/kg per gavage), and CD437 (4 mg/kg per gavage) on days 8, 10, and 12 after surgery. Muscle tissues were collected from vehicle (control), R667-treated, and CD1530-treated mice 30 days after critical defect injury surgery. Macro views of three independent samples (top panels) and representative Masson's trichome staining image of the transverse section (bottom panels) are shown in each group. The muscle injury sites are clearly visible as whitish spots in control, whereas the defect sites of RARγ agonist–treated samples are less apparent. n = 3.

Supplemental Figure S5.

Changes in distribution of phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 during muscle repair in the critical defect muscle injury model. Critical defect muscle injury surgery was performed in 8-week-old CD1 mice. Transverse sections of uninjured muscles (A and F) and injured muscles harvested 2 (B, G, and K), 5 (C, H, and L), 14 (D, I, and M), and 30 (E, J, and N) days after surgery were stained with anti–phospho-Smad1/5/8. F–N are magnified images of the indicated areas in A–E. Arrowheads in F indicate phospho-Smad1/5/8–positive satellite cells. Arrows in G indicate coagulated area. Arrowheads in M and N indicate phospho-Smad1/5/8–positive immature muscle fibers with central nuclei. Scale bars: 100 mm (A–E); 50 mm (F–N).

References

- 1.Close G.L., Kayani A., Vasilaki A., McArdle A. Skeletal muscle damage with exercise and aging. Sports Med. 2005;35:413–427. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200535050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aarimaa V., Rantanen J., Heikkila J., Helttula I., Orava S. Rupture of the pectoralis major muscle. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1256–1262. doi: 10.1177/0363546503261137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCarthy E.F., Sundaram M. Heterotopic ossification: a review. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:609–619. doi: 10.1007/s00256-005-0958-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rantanen J., Thorsson O., Wollmer P., Hurme T., Kalimo H. Effects of therapeutic ultrasound on the regeneration of skeletal myofibers after experimental muscle injury. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:54–59. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270011701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almekinders L.C. Anti-inflammatory treatment of muscular injuries in sport: an update of recent studies. Sports Med. 1999;28:383–388. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199928060-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song Y.H., Song J.L., Delafontaine P., Godard M.P. The therapeutic potential of IGF-I in skeletal muscle repair. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2013;24:310–319. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Musaro A., Giacinti C., Borsellino G., Dobrowolny G., Pelosi L., Cairns L., Ottolenghi S., Cossu G., Bernardi G., Battistini L., Molinaro M., Rosenthal N. Stem cell-mediated muscle regeneration is enhanced by local isoform of insulin-like growth factor 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1206–1210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0303792101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Musaro A., McCullagh K., Paul A., Houghton L., Dobrowolny G., Molinaro M., Barton E.R., Sweeney H.L., Rosenthal N. Localized Igf-1 transgene expression sustains hypertrophy and regeneration in senescent skeletal muscle. Nat Genet. 2001;27:195–200. doi: 10.1038/84839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelosi L., Giacinti C., Nardis C., Borsellino G., Rizzuto E., Nicoletti C., Wannenes F., Battistini L., Rosenthal N., Molinaro M., Musaro A. Local expression of IGF-1 accelerates muscle regeneration by rapidly modulating inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. FASEB J. 2007;21:1393–1402. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7690com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krivickas L.S., Walsh R., Amato A.A. Single muscle fiber contractile properties in adults with muscular dystrophy treated with MYO-029. Muscle Nerve. 2009;39:3–9. doi: 10.1002/mus.21200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chalmers J., Gray D.H., Rush J. Observations on the induction of bone in soft tissues. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1975;57:36–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garland D.E. A clinical perspective on common forms of acquired heterotopic ossification. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;(263):13–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilsson O.S., Persson P.E. Heterotopic bone formation after joint replacement. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:127–131. doi: 10.1097/00002281-199903000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forsberg J.A., Pepek J.M., Wagner S., Wilson K., Flint J., Andersen R.C., Tadaki D., Gage F.A., Stojadinovic A., Elster E.A. Heterotopic ossification in high-energy wartime extremity injuries: prevalence and risk factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1084–1091. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nauth A., Giles E., Potter B.K., Nesti L.J., O'Brien F.P., Bosse M.J., Anglen J.O., Mehta S., Ahn J., Miclau T., Schemitsch E.H. Heterotopic ossification in orthopaedic trauma. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26:684–688. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182724624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimono K., Tung W.E., Macolino C., Chi A.H., Didizian J.H., Mundy C., Chandraratna R.A., Mishina Y., Enomoto-Iwamoto M., Pacifici M., Iwamoto M. Potent inhibition of heterotopic ossification by nuclear retinoic acid receptor-gamma agonists. Nat Med. 2011;17:454–460. doi: 10.1038/nm.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan T., Liu J., Chu A., Wang L., Blais A., Skerjanc I.S. Retinoic acid enhances skeletal myogenesis in human embryonic stem cells by expanding the premyogenic progenitor population. Stem Cell Rev. 2012;8:482–493. doi: 10.1007/s12015-011-9284-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamade A., Deries M., Begemann G., Bally-Cuif L., Genet C., Sabatier F., Bonnieu A., Cousin X. Retinoic acid activates myogenesis in vivo through Fgf8 signalling. Dev Biol. 2006;289:127–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 2008;134:921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rochette-Egly C., Germain P. Dynamic and combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear retinoic acid receptors (RARs) Nucl Recept Signal. 2009;7:e005. doi: 10.1621/nrs.07005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reijntjes S., Francis-West P., Mankoo B.S. Retinoic acid is both necessary for and inhibits myogenic commitment and differentiation in the chick limb. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:125–134. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.082783sr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pacifici M., Cossu G., Molinaro M., Tato F. Vitamin A inhibits chondrogenesis but not myogenesis. Exp Cell Res. 1980;129:469–474. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(80)90517-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robson L.G., Kara T., Crawley A., Tickle C. Tissue and cellular patterning of the musculature in chick wings. Development. 1994;120:1265–1276. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.5.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao Y., Grieshammer U., Rosenthal N. Regulation of a muscle-specific transgene by retinoic acid. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:1345–1354. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.5.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukuda T., Scott G., Komatsu Y., Araya R., Kawano M., Ray M.K., Yamada M., Mishina Y. Generation of a mouse with conditionally activated signaling through the BMP receptor, ALK2. Genesis. 2006;44:159–167. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapellier B., Mark M., Garnier J.M., Dierich A., Chambon P., Ghyselinck N.B. A conditional floxed (loxP-flanked) allele for the retinoic acid receptor gamma (RARgamma) gene. Genesis. 2002;32:95–98. doi: 10.1002/gene.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams J.A., Kondo N., Okabe T., Takeshita N., Pilchak D.M., Koyama E., Ochiai T., Jensen D., Chu M.L., Kane M.A., Napoli J.L., Enomoto-Iwamoto M., Ghyselinck N., Chambon P., Pacifici M., Iwamoto M. Retinoic acid receptors are required for skeletal growth, matrix homeostasis and growth plate function in postnatal mouse. Dev Biol. 2009;328:315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klaholz B.P., Mitschler A., Belema M., Zusi C., Moras D. Enantiomer discrimination illustrated by high-resolution crystal structures of the human nuclear receptor hRARgamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6322–6327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brennan B.J., Brown A.B., Kolis S.J., Rutman O., Gooden C., Davies B.E. Effect of R667, a novel emphysema agent, on the pharmacokinetics of midazolam in healthy men. J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;46:222–228. doi: 10.1177/0091270005283836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimono K., Morrison T.N., Tung W.E., Chandraratna R.A., Williams J.A., Iwamoto M., Pacifici M. Inhibition of ectopic bone formation by a selective retinoic acid receptor alpha-agonist: a new therapy for heterotopic ossification? J Orthop Res. 2010;28:271–277. doi: 10.1002/jor.20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thacher S.M., Vasudevan J., Chandraratna R.A. Therapeutic applications for ligands of retinoid receptors. Curr Pharm Des. 2000;6:25–58. doi: 10.2174/1381612003401415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao X., Spanjaard R.A. The apoptotic action of the retinoid CD437/AHPN: diverse effects, common basis. J Biomed Sci. 2003;10:44–49. doi: 10.1007/BF02255996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossant J., Zirngibl R., Cado D., Shago M., Giguere V. Expression of a retinoic acid response element-hsplacZ transgene defines specific domains of transcriptional activity during mouse embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1333–1344. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.8.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menetrey J., Kasemkijwattana C., Fu F.H., Moreland M.S., Huard J. Suturing versus immobilization of a muscle laceration: a morphological and functional study in a mouse model. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:222–229. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270021801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clever J.L., Sakai Y., Wang R.A., Schneider D.B. Inefficient skeletal muscle repair in inhibitor of differentiation knockout mice suggests a crucial role for BMP signaling during adult muscle regeneration. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C1087–C1099. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00388.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedrichs M., Wirsdoerfer F., Flohe S.B., Schneider S., Wuelling M., Vortkamp A. BMP signaling balances proliferation and differentiation of muscle satellite cell descendants. BMC Cell Biol. 2011;12:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sartori R., Schirwis E., Blaauw B., Bortolanza S., Zhao J., Enzo E., Stantzou A., Mouisel E., Toniolo L., Ferry A., Stricker S., Goldberg A.L., Dupont S., Piccolo S., Amthor H., Sandri M. BMP signaling controls muscle mass. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1309–1318. doi: 10.1038/ng.2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weston A.D., Rosen V., Chandraratna R.A., Underhill T.M. Regulation of skeletal progenitor differentiation by the BMP and retinoid signaling pathways. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:679–690. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.4.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garnaas M.K., Cutting C.C., Meyers A., Kelsey P.B., Jr., Harris J.M., North T.E., Goessling W. Rargb regulates organ laterality in a zebrafish model of right atrial isomerism. Dev Biol. 2012;372:178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoffman L.M., Garcha K., Karamboulas K., Cowan M.F., Drysdale L.M., Horton W.A., Underhill T.M. BMP action in skeletogenesis involves attenuation of retinoid signaling. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:101–113. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheng N., Xie Z., Wang C., Bai G., Zhang K., Zhu Q., Song J., Guillemot F., Chen Y.G., Lin A., Jing N. Retinoic acid regulates bone morphogenic protein signal duration by promoting the degradation of phosphorylated Smad1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18886–18891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009244107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raida M., Heymann A.C., Gunther C., Niederwieser D. Role of bone morphogenetic protein 2 in the crosstalk between endothelial progenitor cells and mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Med. 2006;18:735–739. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.18.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fiedler J., Roderer G., Gunther K.P., Brenner R.E. BMP-2, BMP-4, and PDGF-bb stimulate chemotactic migration of primary human mesenchymal progenitor cells. J Cell Biochem. 2002;87:305–312. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mok G.F., Cardenas R., Anderton H., Campbell K.H., Sweetman D. Interactions between FGF18 and retinoic acid regulate differentiation of chick embryo limb myoblasts. Dev Biol. 2014;396:214–223. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yuan J., Tang Z., Yang S., Li K. CRABP2 promotes myoblast differentiation and is modulated by the transcription factors MyoD and Sp1 in C2C12 cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu G.H., Huang J., Bi Y., Su Y., Tang Y., He B.C., He Y., Luo J., Wang Y., Chen L., Zuo G.W., Jiang W., Luo Q., Shen J., Liu B., Zhang W.L., Shi Q., Zhang B.Q., Kang Q., Zhu J., Tian J., Luu H.H., Haydon R.C., Chen Y., He T.C. Activation of RXR and RAR signaling promotes myogenic differentiation of myoblastic C2C12 cells. Differentiation. 2009;78:195–204. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berry D.C., DeSantis D., Soltanian H., Croniger C.M., Noy N. Retinoic acid upregulates preadipocyte genes to block adipogenesis and suppress diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2012;61:1112–1121. doi: 10.2337/db11-1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]