Abstract

Remyelination within the central nervous system (CNS) most often is the result of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells differentiating into myelin-forming oligodendrocytes. In some cases, however, Schwann cells, the peripheral nervous system myelinating glia, are found remyelinating demyelinated regions of the CNS. The reason for this peripheral type of remyelination in the CNS and what governs it is unknown. Here, we used a conditional astrocytic phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 knockout mouse model to investigate the effect of abrogating astrocyte activation on remyelination after lysolecithin-induced demyelination of spinal cord white matter. We show that oligodendrocyte-mediated remyelination decreases and Schwann cell remyelination increases in lesioned knockout mice in comparison with lesioned controls. Our study shows that astrocyte activation plays a crucial role in the balance between Schwann cell and oligodendrocyte remyelination in the CNS, and provides further insight into remyelination of CNS axons by Schwann cells.

The adult mammalian central nervous system (CNS) is remarkably efficient at replacing myelin-forming cells after primary demyelination.1 This regenerative process is called remyelination. Although in most circumstances the new myelin-forming cells are oligodendrocytes, the myelinating cells of the CNS, it also has been well established in both experimental models and clinical disease that remyelination can be mediated by Schwann cells, the myelinating cells of the peripheral nervous system.2–8 New remyelinating oligodendrocytes are generated from a population of neural progenitor cells that are distributed widely throughout the adult CNS.9–11 These cells can be identified using a range of markers, of which two commonly used markers are Pdgfra and NG2, and generally are referred to as oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs).12 In the past, it was assumed that all Schwann cells engaged in remyelinating CNS axons were derived from peripheral nervous system Schwann cells, and entered the CNS through breaches in the astrocytic glia limitans.13,14 Although this is certainly a source of some CNS Schwann cells,10 transplantation15 and genetic fate mapping studies10 have shown that large numbers of CNS Schwann cells are derived from OPCs.

What remains unclear is how and why Schwann cell remyelination occurs within the CNS. Clues are provided by the anatomic features associated with areas of the CNS in which either oligodendrocyte or Schwann cell remyelination occurs. The most consistently observed feature is the astrocyte status: oligodendrocyte remyelination occurs in regions where astrocytes are present, restoring a complete CNS glial environment, whereas Schwann cell remyelination occurs where astrocytes are absent, resulting in patches of tissue that resemble the peripheral nervous system.16–19 Indeed, the extent of Schwann cell remyelination is directly proportional to the extent of astrocyte absence. This is seen most clearly when comparing the remyelination of ethidium bromide–induced spinal cord demyelination, in which there initially is extensive astrocyte loss and hence a high proportion of Schwann cell remyelination, with remyelination of lysolecithin-induced spinal cord demyelination, which is more sparing of astrocytes and hence has a smaller Schwann cell contribution to remyelination.20

The extent of Schwann cell remyelination has been manipulated experimentally using cell transplantation approaches, in which, for example, the extent of Schwann cell remyelination of ethidium bromide–induced spinal cord demyelination can be reduced by astrocyte transplantation.21,22 However, whether astrocyte responses play a physiological role in determining the balance of central versus peripheral types of remyelination has not been tested in experiments in which the endogenous astrocyte response is altered. In this study we took advantage of the central role of phosphorylation of the transcription factor signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) in the astrocyte response to CNS injury23 to address the hypothesis that the proportion of Schwann cell remyelination after experimental demyelination is dependent on astrocyte activation within the lesion. By using a conditional Cre-loxP approach we were able to specifically prevent Stat3 phosphorylation in astrocytes after focal toxin-induced demyelination. We showed that not only did this lead to a reduced astrocyte response, it also led to an impairment in OPC activation and resulted in an increased level of Schwann cell remyelination and a decreased level of oligodendrocyte remyelination, thereby showing a central role of astrocyte activation in determining the nature of CNS remyelination.

Materials and Methods

Animals

The astrocyte-specific phosphorylated Stat3 (pStat3) conditional knockout (CKO) mouse strain [glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-STAT3-CKO] on a C57BL6 background kindly was provided by Dr. Michael Sofroniew (University of California, Los Angeles, CA).23 Ablation of the activated form of Stat3 in astrocytes was achieved by conditional Cre-loxP recombination. In this strain, the Cre recombinase is expressed under the mouse GFAP promoter (GFAP-Cre). Recombination occurs at loxP sites flanking exon 22 (the phosphorylation site containing exon) of the Stat3 gene (Stat3fl/fl). As a result, phosphorylation of Stat3, crucial for its function, does not occur. Experimental animals were bred using homozygous Stat3fl/fl males and heterozygous Cre-expressing females (GFAP-Cre+/−:Statfl/fl). The resulting GFAP-STAT3-CKO mice showed normal development and were fertile. Both male and female mice were used in the experiments, with non–Cre-expressing littermates (Statfl/fl) used as controls. Experiments were performed in compliance with UK Home Office regulations and institutional guidelines.

Toxin-Induced Demyelination

Focal spinal cord demyelination was created as previously described.24 Briefly, 8- to 10-week-old mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and the spinal cord was exposed at the level of T12/T13 by removing the soft tissue between the vertebrae. One microliter of 1% l-α-lysophosphatidylcholine (lysolecithin; Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) in sterile saline was injected using a Hamilton syringe (Sigma-Aldrich) fitted with a fine glass tip into the ventral spinal cord white matter (Figure 1A). At designated time points after injection, mice were terminally anesthetized with an overdose of pentobarbital before being perfused transcardially with either 4% paraformaldehyde for immunohistochemistry or 4% glutaraldehyde for resin embedding and electron microscopy.

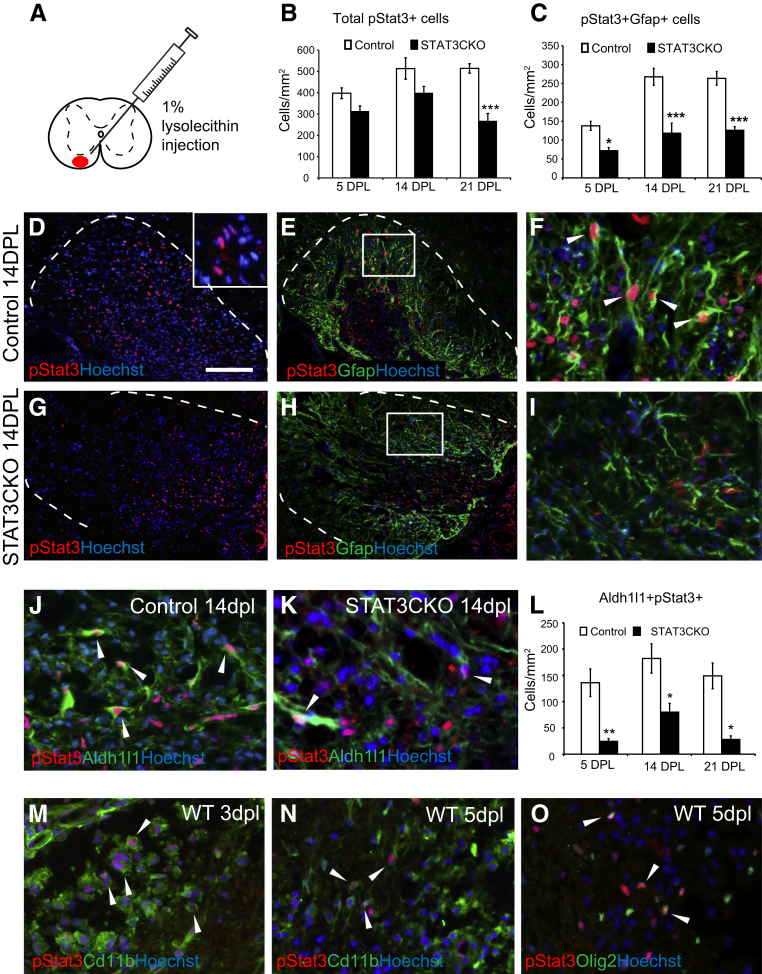

Figure 1.

Expression of phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (pStat3) after focal demyelination in spinal cord white matter is reduced in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) promoter-controlled conditional Stat3 knockout mice. A: Control and mutant animals were injected with lysolecithin to create a focal demyelination lesion. B and C: The quantification of the total numbers of pStat3+ (B) and pStat3/Gfap double-positive (C) cells in control and GFAP-STAT3-CKO lesions. D–I: Immunostaining of lesioned ventral spinal cord white matter at 14 days after lesion (dpl). D and G: Merged immunostaining for phosphorylated Stat3 (pStat3), and the nuclear dye Hoechst 33342. The dotted line marks the border of the demyelinated area, as demarcated by increased cellularity shown by Hoechst staining (inset in D). E and H: Co-labeling with pStat3 and astrocyte marker Gfap; boxed area in each image is magnified in panels F and I, respectively. J and K: Representative images show colocalization of an alternative astrocyte marker Aldh1l1 and pStat3 in demyelinated areas at 14 dpl, in control (J) and GFAP-STAT3-CKO (K) animals. L–O: Quantification is shown. pSTAT3 also is expressed in other types of cells, including CD11b+ macrophages/microglia (M and N) and Olig2+ oligodendrocyte lineage cells (O) within lesions. Means ± SEM are shown. Arrowheads (F, J, K, and M–O) indicate cells labeled with both markers. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Scale bars: 100 μm (D–I); 25 μm (J and K). WT, wild type.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on 12-μm–thick frozen sections. When required, heat-mediated antigen retrieval with 10 mmol/L sodium citrate buffer (pH 6) was performed before the standard protocol for indirect immunofluorescence staining. Briefly, slide-mounted sections were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4), and blocked with 5% normal donkey serum and 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections then were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. The following primary antibodies were used: Olig2 1:200 (Millipore, Watford, UK), CC1 1:100 (Apc; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA), ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1) 1:500 (Wako, Osaka, Japan), pStat3 (Tyr705) 1:100 (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 L1 (Aldh1l1) 1:100 (clone N103/39; Neuromab, Davis, CA). For Apc and Aldh1l1 staining on lesion sections, mouse-on-mouse blocking reagents (Vector Labs, Peterborough, UK) were used to reduce nonspecific background according to the manufacturer's instructions. Staining was visualized with Alexa Fluor–conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500; Invitrogen, Paisley, UK). The slides were counterstained with 0.1% Sudan Black (Sigma-Aldrich) to reduce background and show the lesion area, and subsequently were mounted in FluorSave Reagent (Calbiochem). The images were acquired using a Zeiss Axio Observer fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss GmbH, Jena, Germany).

In Situ Hybridization

In situ hybridization of digoxigenin-labeled complementary RNA probes for myelin protein zero and myelin proteolipid protein was performed as previously described.25 Briefly, sections were hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled complementary RNA probes at 65°C overnight and subjected to a standard wash protocol (50% formamide, 1× standard saline citrate, 0.1% Tween-20, 65°C, 3× 30 minutes) to remove nonspecific probe binding. The target bound probes were detected by alkaline phosphatase–conjugated antidigoxigenin antibody, and visualized as purple precipitate after incubation in NBT/BCIP solution according to the manufacturer's instructions (Roche, Lewes, UK). The slides were dehydrated with ascending concentration of ethanol, cleared with xylene, and mounted in dibutyl phthalate in xylene. Images were acquired with the Zeiss Axio Observer microscope.

Electron Microscopy

Animals were perfused with 4% glutaraldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.4 mmol/L CaCl2. The spinal cord was sliced coronally at 1-mm thickness and treated with 2% osmium tetroxide overnight before being subjected to a standard protocol for epoxy resin embedding.24 Lesions were localized on semithin 1-μm sections stained with toluidine blue. Ultrathin sections of the lesion site were cut onto copper grids and stained with uranyl acetate before being examined with an H-600 Transmission Electron Microscope (Hitachi Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

Quantification and Statistics

For each animal, three demyelinated lesion sections, separated by approximately 120 μm, were selected from within the central region of the lesion. For immunostaining, the outline of each lesion was defined based on the increase in cellularity inside the lesion, as visualized by Hoechst 33342 counterstain. For in situ hybridization, the outline was defined based on the lesioned tissue texture, using Zeiss AxioVision software version 4.8. The number of marker-positive cells inside the lesions was counted manually using ImageJ version 1.46r (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij), and normalized against the lesion area. The average of three sections was used for each lesioned animal. For each group, four to five animals were used. To compare differences between the control and experimental groups, a two-way analysis of variance followed by the Bonferroni post-test was used, and the threshold for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Expression of Phosphorylated Stat3 in Astrocytes Is Reduced in GFAP-STAT3-CKO Mice after Toxin-Induced CNS Demyelination

Phosphorylation of Stat3 is increased in multiple CNS cell types during injury.25–27 To verify this in our demyelination model we examined the expression of pStat3 in control, non–Cre-expressing lesioned and unlesioned mice, using a pStat3-specific antibody. To obtain a focal demyelinating lesion, animals were injected with 1% lysolecithin solution into the ventral spinal cord (Figure 1A). In normal unlesioned spinal cord, very few cells were found to express pStat3 (not shown). In contrast, there was a marked increase in pStat3 expression 5 days after lesion (dpl) (Figure 1B). The pStat3 levels remained increased at 14 and 21 dpl, albeit they were somewhat decreased compared with the expression at 5 dpl (Figure 1B). The staining was most intense within the nucleus (Figure 1D). pStat3+ cells included a variety of cell types, such as CD11b+ macrophages/microglia, Olig2+ oligodendrocyte lineage cells, and Gfap+ astrocytes (Figure 1, E, F, M–O).

Stat3 phosphorylation plays a key role in mediating astrocyte responses to CNS injury.23 To explore the astrocyte-specific role of pStat3 in lysolecithin-induced demyelination further, we used a conditional Stat3 knockout mouse model in which Cre recombinase was expressed under the GFAP promoter. The Cre recombinase excised the floxed Stat3 exon 22 containing the phosphorylation site (Tyr 705) involved in Stat3 activation,23 resulting in a mutant unable to phosphorylate Stat3 in astrocytes (GFAP-STAT3-CKO mice). We first investigated pStat3 expression in lesioned GFAP-STAT3-CKO mice. As expected, the number pStat3-expressing astrocytes, as examined by co-labeling with astrocyte markers Gfap (Figure 1, C–I) and aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (Aldh1l1)28 surrounding pStat3+ nuclei, was significantly lower in the mutants compared with controls (Figure 1, J–L).

Demyelination-associated Astrogliosis Is Reduced in GFAP-STAT3-CKO Mice

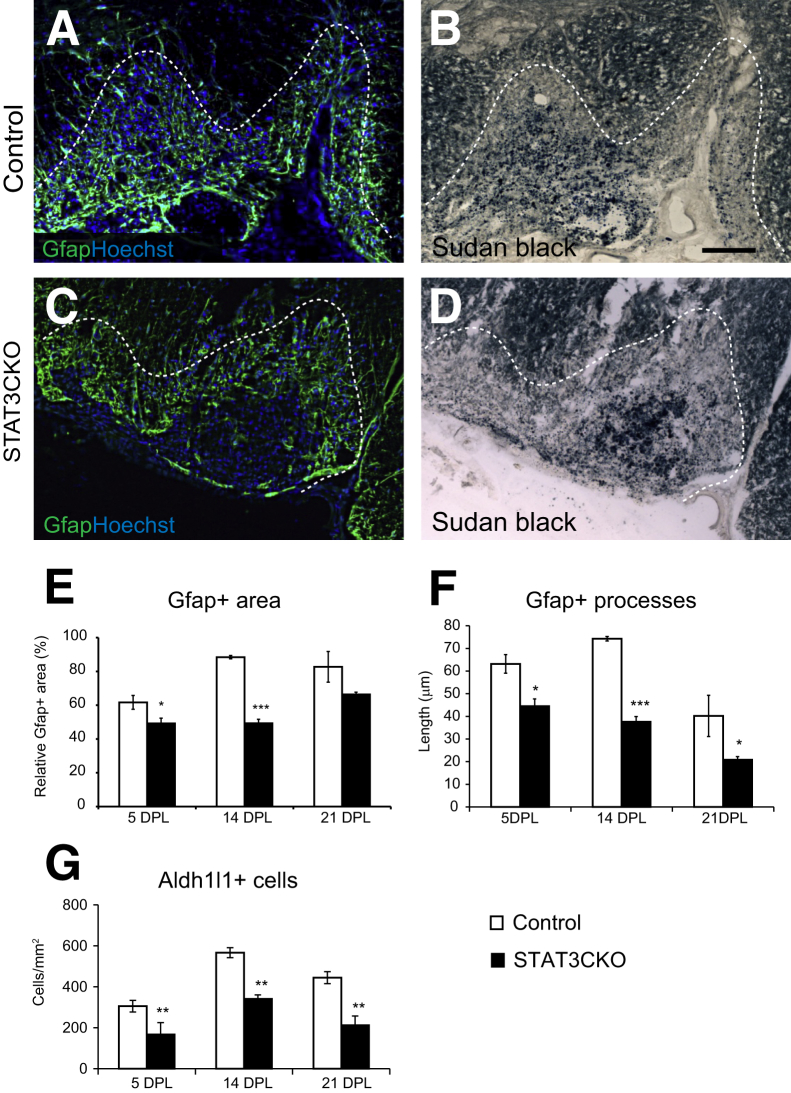

Lysolecithin demyelination is characterized by an abundance of astrocytes within the lesioned area (Figures 1, C–L, and 2, A–D). In control mice, we observed an increase in Gfap immunoreactivity within and beyond the demyelinated area (the latter was determined by the lipophilic dye Sudan Black) (Figure 2, A and B). An increase in Gfap expression also was seen in demyelinated areas of the spinal cord in GFAP-STAT3-CKO mice when compared with unlesioned tissue surrounding the lesioned areas (Figures 1H, and 2, C and D), although the intensity of the staining was lower than in control animals (not shown). Because Gfap staining localizes to astrocytic processes that often form a tangled mesh in injured tissue, rendering quantification of individual positive cells challenging, we instead compared the areas occupied by reactive astrocytes in control and GFAP-STAT3-CKO spinal cord lesions, as defined by a clear boundary of increased Gfap reactivity. We found the relative area of reactive astrocytes over total lesion area to be reduced in GFAP-STAT3-CKO mice at both 5 and 14 dpl and average lengths of astrocyte processes at all time points observed (Figure 2, E and F). This was verified by counting the number of Aldh1l1+ cells in the demyelinated areas, which showed a significant 40% to 60% reduction in GFAP-STAT3-CKO mice compared with controls at all three survival time points examined (Figure 2G).

Figure 2.

Astrocyte response to demyelination is attenuated in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)-CKO mice. A–D: Images illustrate areas of lysolecithin-induced demyelination in ventral spinal cord white matter at 14 days after lesion (dpl), immunolabeled for astrocyte marker Gfap and nucleus dye Hoechst 33342 (A and C), with lesion areas demarcated by counterstaining with Sudan Black (B and D). Graphs show the relative total area occupied by immunoreactive E–G: Gfap staining in demyelinated lesions (E) and the average length of astrocytic processes in control and GFAP-STAT3-CKO mice (F), and the number of astrocytes inside the lesion area identified by the astrocyte marker Aldh1l1 (G). Dotted lines mark the lesion boundaries. Means ± SEM are shown. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Scale bars = 100 μm (B, applies to all images).

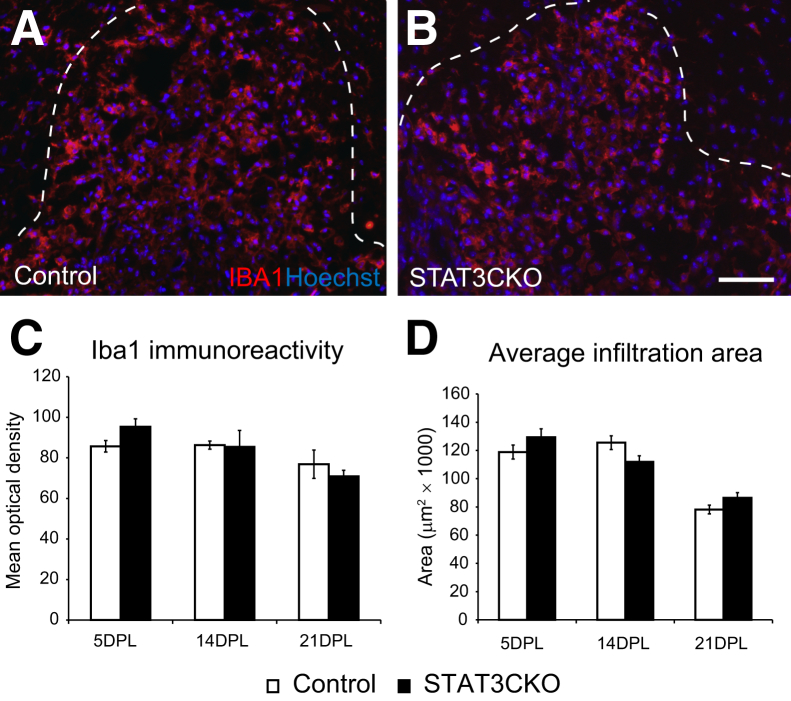

Reducing Stat3 Activation in Astrocytes Does Not Alter Macrophage Responses to Demyelination

Abrogation of Stat3 activation results in spread of inflammation after a spinal cord crush injury.23,29 To assess the influence of astrocytic Stat3 knockout in our demyelination model, we examined the microglia/macrophage response in GFAP-STAT3-CKO mice after demyelination by immunostaining for Iba1. Iba1+ cells were present at high density throughout the lesion (Figure 3). It was not feasible to quantify the microglia/macrophage cellular density because of the fused pattern of immunostaining in lesions, therefore we measured the normalized mean optical density to represent the extent of microglia/macrophage infiltration in the demyelinated area. There was no difference in either Iba1 intensity or the area of Iba1+ cell infiltration at all of the time points examined (Figure 3, C and D).

Figure 3.

Macrophage and microglia infiltration after demyelination in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)-CKO mice is similar to that in controls. The microglia/macrophages in the demyelinated area at 5 days after lesion (dpl) were visualized with antibody against macrophage/microglia marker ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba1) in control (A) and GFAP-STAT3-CKO (B) mice. C: Mean optical density was used to compare the Iba1 immunoreactivity between controls and mutants across time points. D: The average macrophage/microglia infiltration area at different survival times. Measurements were taken from transverse sections of the lesion that had the largest lesion area (identified by increased cellularity). Dotted lines mark the lesion boundaries. Means ± SEM are shown. Scale bar = 50 μm (B, applies to all images).

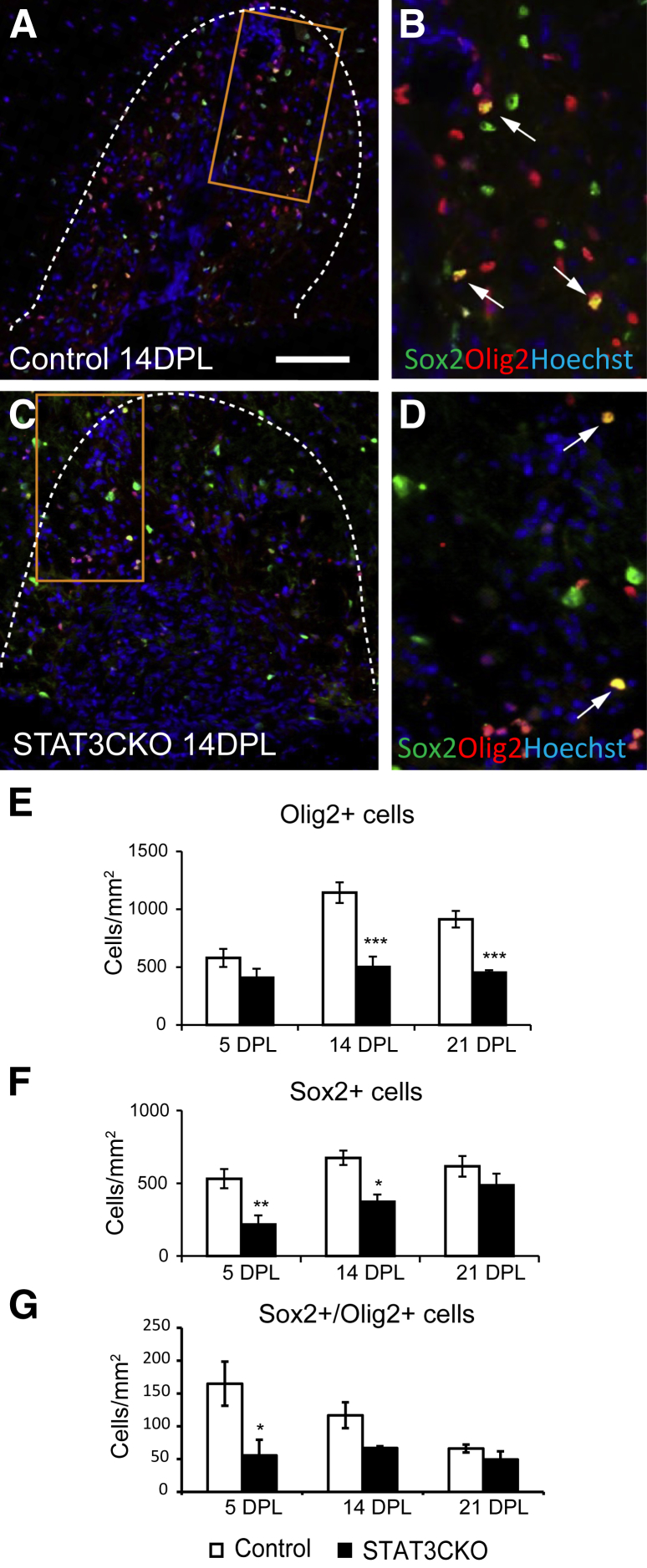

The Attenuated Astrocyte Response Reduces Oligodendrocyte Remyelination

Astrocytes are known to influence OPCs during CNS remyelination.21,30–32 We therefore assessed the impact of the conditional astrocytic pStat3 ablation on oligodendrocyte remyelination by comparing the distribution of oligodendrocyte lineage cells using different markers expressed at specific stages of lineage progression in control and mutant lesioned mice. In control animals, Olig2+ cell numbers increased at 5 dpl (when OPCs are recruited actively to the lesion), increased further at 14 dpl (when differentiation is ongoing), and remained high at 21 dpl (when remyelination is near completion) (Figure 4, A, B, and E). In GFAP-STAT3-CKO animals, the density of Olig2+ cells was comparable with controls at 5 dpl, but was reduced significantly at 14 and 21 dpl (Figure 4, C–E).

Figure 4.

The response of oligodendrocyte lineage cells to lysolecithin-induced spinal cord demyelination in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)-CKO mice. A–D: Demyelinated areas of ventral spinal cord lesions at 14 days after lesion (dpl) from control and GFAP-pSTAT3-CKO mice double-stained for oligodendrocyte lineage marker Olig2 and transcription factor Sox2, a marker for activated oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. B and D: Enlarged areas marked by an orange rectangle in panels A and C, respectively. E–G: Densities of single-labeled and co-labeled cells are compared. Dotted lines in A and C mark the areas of demyelination. Arrows indicate double-labeled cells. Dotted lines mark the lesion boundaries. Means ± SEM are shown. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Scale bar = 100 μm (A, applies to all images).

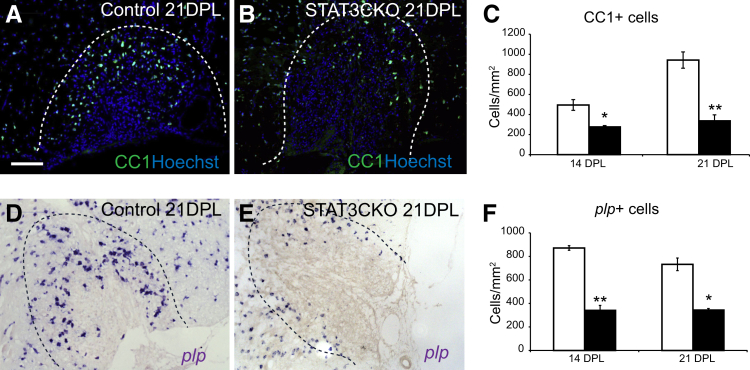

Increased expression of the transcription factor Sox2 is a marker of OPC activation (unpublished observations). The density of total Sox2+ cells and Sox2+/Olig2+ co-labeled cells in the demyelinated area were significantly lower in the GFAP-STAT3-CKO group compared with controls at 5 and 14 dpl, suggesting impaired OPC activation (Figure 4, F and G). There was also a reduction in Sox2+ cells that did not express Olig2, which are likely to be astrocytes, and this is consistent with the data in Figure 2G. The reduced density of Olig2+ and Olig2+/Sox2+ cells was mirrored by a reduced expression of the mature oligodendrocyte markers CC1 and myelin proteolipid protein at 14 and 21 dpl (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Oligodendrocyte remyelination is reduced in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)-CKO mice. Remyelination by oligodendrocytes in control and GFAP-pSTAT3-CKO mice at 14 and 21 days after lesion (dpl) was assessed by immunostaining for the differentiated oligodendrocyte marker CC1 (A and B) and in situ hybridization for proteolipid protein (plp) mRNA (D and E). Images show representative examples of demyelinated lesions at 21 dpl. C and F: The cell densities for each marker at selected survival times are compared. Dotted lines mark the lesion boundaries. Means ± SEM are shown. ∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗P < 0.001. Scale bar = 100 μm (A, applies to all images).

Attenuated Astrogliosis Increases Schwann Cell CNS Remyelination

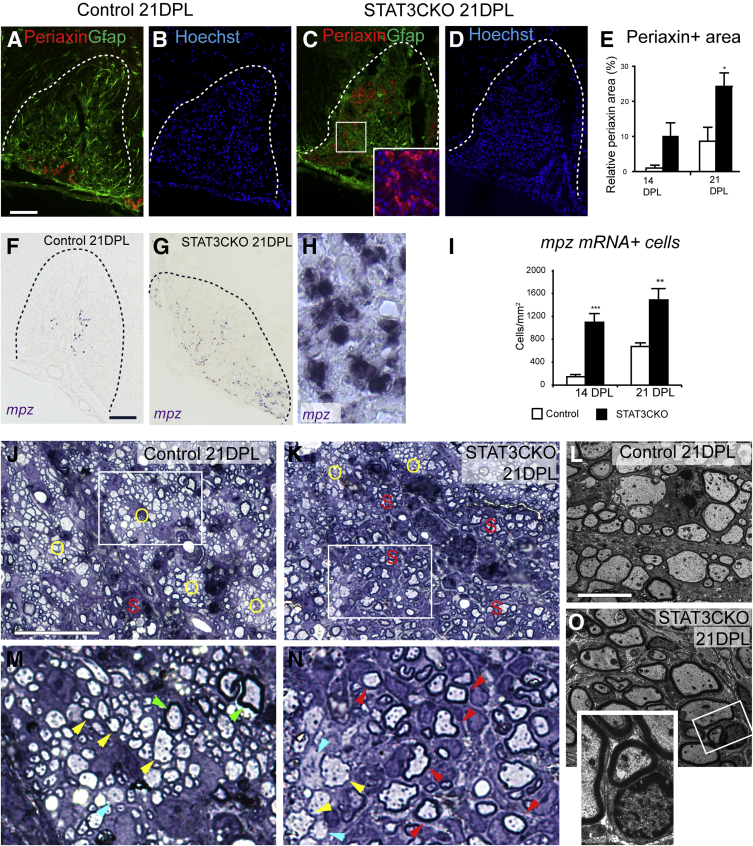

The mutual exclusivity of the presence of astrocytes and Schwann cell remyelination within the same region of repaired demyelinated lesions led us to reason that an attenuated astrocytic response could lead to increased Schwann cell remyelination in GFAP-STAT3-CKO mutants. Indeed, compared with lesioned controls, the GFAP-STAT3-CKO spinal cord white matter lesions showed increased areas of periaxin antigenicity and increased density of myelin protein zero mRNA expression at 14 and 21 dpl, indicating increased Schwann cell remyelination (Figure 6, A–I). The increased number of remyelinating Schwann cells was confirmed by analyzing semithin resin sections and performing electron microscopy, where Schwann cells could be recognized readily by their typical signet-ring morphology and relatively thicker myelin sheath (Figure 6, J–O). Notably, in the GFAP-STAT3-CKO lesions, Schwann cell remyelinated areas contained more demyelinated axons than oligodendrocyte remyelinated areas at all of the time points examined (Figure 6, M and N). Because toxin-induced demyelination invariably undergoes complete remyelination, it is likely that these few remaining demyelinated axons eventually will undergo remyelination.

Figure 6.

Schwann cell remyelination increases in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3)-CKO mice. Remyelinating Schwann cells from control and GFAP-STAT3-CKO mice at 21 days after lesion (dpl) were examined by periaxin immunostaining (A–D) and myelin protein zero (mpz) mRNA in situ hybridization (F–H). Dotted lines (A–D, F, and G) mark demyelinated areas. The inset in C shows magnified boxed area with periaxin and Hoechst 33342. E and I: Quantification of the relative area of positive periaxin immunofluorescence (E) and cells containing mpz mRNA (I). J and K: Semithin resin sections from control (J) and STAT3CKO (K) lesioned mice were stained with toluidine blue. Areas of oligodendrocyte remyelination are marked with the yellow letter O, and that of Schwann cells are marked with the red letter S. M and N: Enlarged boxed areas from panels J and K, respectively. L and O: Examples of axons remyelinated by oligodendrocytes are marked by yellow arrowheads; green arrowheads point to examples of axons that were not demyelinated, blue arrowheads indicate poorly remyelinated axons, and red arrowheads mark typical morphology of myelinating Schwann cells. These observations were verified further by electron microscopy with examples shown in control (L) and GFAP-STAT3-CKO (O) animals. Inset (O) shows an enlarged view of the boxed area, showing the typical structure of myelinating Schwann cells. Dotted lines mark the lesion boundaries. Means ± SEM are shown. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Scale bars: 100 μm (A–D, F, G, J–M); 5 μm (N and O).

Discussion

In this study, we used a transgenic conditional astrocytic pStat3 knockout model to show that altering astrocyte activation significantly influences the response to CNS demyelination injury. This model had been used previously to study astrogliosis and scar formation in spinal cord trauma.23 In accordance with this previous study, we found that abrogating astrocyte activation decreased the astrocytic response in the lesion. However, unlike in the trauma model, we found no effect of pStat3 manipulation in astrocytes on macrophage responses.29 Our study focused on remyelination and showed that oligodendrocyte remyelination was reduced and Schwann cell remyelination was increased in lesioned GFAP-STAT3-CKO mice. Our findings therefore constitute the first direct proof of the indispensable role of astrocyte activation in the balance between Schwann cell and oligodendrocyte remyelination in the CNS.

The intriguing phenomenon of Schwann cell remyelination within the CNS has been recognized for many decades; however, its mechanisms and functions remain obscure. It now is known, as a result of genetic fate mapping strategies, that contrary to the previously held belief, many of the Schwann cells that appear in the CNS are not immigrants from the peripheral nervous system but instead are derived from CNS progenitor cells.10 It also has been recognized that Schwann cell remyelination often occurs around blood vessels and within areas of damaged CNS from which astrocytes are absent.16,19,33 This observation has led to the hypothesis that the presence or absence of astrocytes determines if CNS progenitor cells support remyelination of demyelinated axons by becoming an oligodendrocyte or a Schwann cell. Our results clearly show a central role for astrocytes in determining the balance of central versus peripheral-type remyelination. It remains unclear how astrocytes exert this effect. One proposed hypothesis is that members of the bone morphogenetic protein family induce OPCs to become Schwann cells, and that this is prevented in the presence of astrocytes by astrocyte-derived inhibitors of bone morphogenetic protein signaling, with OPCs becoming oligodendrocytes instead. However, although there is some evidence that the fate of transplanted OPCs can be influenced by prior treatment in vitro with bone morphogenetic proteins,34,35 there is no compelling evidence for such mechanisms in vivo. Because the current STAT3 knockout takes place at the first appearance of GFAP expression during development, it is possible that there are long-term changes in the environment that contribute to the shift in remyelination type. However, if such changes do exist they would seem to be shown only after injury because phenotypic changes have not been identified in the absence of injury in either our study or in previous studies on astrocyte STAT3-null animals.23 Thus, exactly how OPCs become Schwann cells in the CNS in the absence of astrocytes remains to be fully explored.

What is the functional significance of Schwann cells myelinating CNS axons? There are two main functions of myelin: to allow rapid saltatory conduction and to help maintain axon health and integrity.36 It has been evident for many years that Schwann cell myelination restores saltatory conduction to demyelinated CNS axons, and from this perspective it appears to make no difference which type of myelin surrounds the axons.37,38 However, the relative effect of peripheral versus central-type myelin on axonal integrity is entirely unknown. Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes differ in a number of ways: they develop from different tissues, use different strategies to myelinate target axons, produce different extracellular components, and assemble molecularly distinct nodes and paranodes.39 Moreover, key differences have been shown in their metabolic relationships with the axons they ensheath.40 Therefore, it is possible that in the context of recovery from CNS demyelinating injury, Schwann cell CNS remyelination may have distinctive physiological advantages compared with oligodendrocyte remyelination, although this hypothesis remains to be tested. Certainly, in the context of immune-mediated damage directed against epitopes specific to oligodendrocytes and their myelin, one might imagine that the Schwann cell would be resistant to direct injury and therefore this form of remyelination might protect against subsequent oligodendrocyte-directed immune attack.

Our study has shown that a substantial reduction of pStat3-mediated astrocyte activation is a sufficient prerequisite to sway the remyelination process toward peripheral nervous system–type remyelination in the CNS. This evidence will help to elucidate further the development and function of peripheral-type CNS remyelination, which presents not only an intriguing biological phenomenon but also an interesting and unexplored therapeutic possibility.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael Sofroniew for providing the GFAP-STAT3-CKO mice, and Michael Peacock and Daniel Morrison for their help with electron microscopy.

Footnotes

Supported by grants (reference 941) from the UK Multiple Sclerosis Society, the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technology Development (CNPq)200993/2010-0 (G.M.d.C.) and 201797/2011-9, and Ciência Sem Fronteiras.

Disclosures: None declared.

Contributor Information

Chao Zhao, Email: cz213@cam.ac.uk.

Robin J.M. Franklin, Email: rjf1000@cam.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Franklin R.J.M., ffrench-Constant C. Remyelination in the CNS: from biology to therapy. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:839–855. doi: 10.1038/nrn2480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dusart I., Isacson O., Nothias F., Gumpel M., Peshanski M. Presence of Schwann cells in neurodegenerative lesions of the central nervous system. Neurosci Lett. 1989;105:246–250. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(89)90628-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felts P.A., Woolston A.M., Fernando H.B., Asquith S., Gregson N.A., Mizzi O.J., Smith K.J. Inflammation and primary demyelination induced by the intraspinal injection of lipopolysaccharide. Brain. 2005;128:1649–1666. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Itoyama Y., Webster H.D., Richardson E.P., Jr., Trapp B.D. Schwann cell remyelination of demyelinated axons in spinal cord multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol. 1983;14:339–346. doi: 10.1002/ana.410140313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder D.H., Valsamis M.P., Stone S.H., Raine C.S. Progressive demyelination and reparative phenomena in chronic experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1975;34:209–221. doi: 10.1097/00005072-197505000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncan I.D., Hoffman R.L. Schwann cell invasion of the central nervous system of the myelin mutants. J Anat. 1997;190:35–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1997.19010035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guest J.D., Hiester E.D., Bunge R.P. Demyelination and Schwann cell responses adjacent to injury epicenter cavities following chronic human spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol. 2005;192:384–393. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blakemore W.F. Remyelination by Schwann cells of axons demyelinated by intraspinal injection of 6-aminonicotinamide in the rat. J Neurocytol. 1975;4:745–757. doi: 10.1007/BF01181634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gensert J.M., Goldman J.E. Endogenous progenitors remyelinate demyelinated axons in the adult CNS. Neuron. 1997;19:197–203. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80359-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zawadzka M., Rivers L.E., Fancy S.P.J., Zhao C., Tripathi R., Jamen F., Young K., Goncharevich A., Pohl H., Rizzi M., Rowitch D.H., Kessaris N., Suter U., Richardson W.D., Franklin R.J.M. CNS-resident glial progenitor/stem cells produce Schwann cells as well as oligodendrocytes during repair of CNS demyelination. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:578–590. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tripathi R.B., Rivers L.E., Young K.M., Jamen F., Richardson W.D. NG2 glia generate new oligodendrocytes but few astrocytes in a murine experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis model of demyelinating disease. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16383–16390. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3411-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Richardson W.D., Young K.M., Tripathi R.B., McKenzie I. NG2-glia as multipotent neural stem cells: fact or fantasy? Neuron. 2011;70:661–673. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franklin R.J.M., Blakemore W.F. Requirements for Schwann cell migration within CNS environments: a viewpoint. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1993;11:641–649. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(93)90052-F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franklin R.J.M., Blakemore W.F. Reconstruction of the glia limitans by sub-arachnoid transplantation of astrocyte-enriched cultures. Microsc Res Tech. 1995;32:295–301. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070320404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keirstead H.S., Ben-Hur T., Rogister B., O'Leary M.T., Dubois-Dalcq M., Blakemore W.F. Polysialylated neural cell adhesion molecule-positive CNS precursors generate both oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells to remyelinate the CNS after transplantation. J Neurosci. 1999;19:7529–7536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-17-07529.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blakemore W.F. Invasion of Schwann cells into the spinal cord of the rat following local injections of lysolecithin. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1976;2:21–39. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodruff R.H., Franklin R.J.M. Demyelination and remyelination of the caudal cerebellar peduncle of adult rats following stereotaxic injections of lysolecithin, ethidium bromide and complement/anti-galactocerebroside: a comparative study. Glia. 1999;25:216–228. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(19990201)25:3<216::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Itoyama Y., Ohnishi A., Tateishi J., Kuroiwa Y., Webster H.D. Spinal cord multiple sclerosis lesions in Japanese patients: Schwann cell remyelination occurs in areas that lack glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) Acta Neuropathol. 1985;65:217–223. doi: 10.1007/BF00687001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talbott J.F., Loy D.N., Liu Y., Qiu M.S., Bunge M.B., Rao M.S., Whittemore S.R. Endogenous Nkx2.2(+)/Olig2(+) oligodendrocyte precursor cells fail to remyelinate the demyelinated adult rat spinal cord in the absence of astrocytes. Exp Neurol. 2005;192:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blakemore W.F., Franklin R.J.M. Remyelination in experimental models of toxin-induced demyelination. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;318:193–212. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-73677-6_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franklin R.J.M., Crang A.J., Blakemore W.F. Transplanted type-1 astrocytes facilitate repair of demyelinating lesions by host oligodendrocytes in adult rat spinal cord. J Neurocytol. 1991;20:420–430. doi: 10.1007/BF01355538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blakemore W.F., Gilson J.M., Crang A.J. The presence of astrocytes in areas of demyelination influences remyelination following transplantation of oligodendrocyte progenitors. Exp Neurol. 2003;184:955–963. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4886(03)00347-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herrmann J.E., Imura T., Song B., Qi J., Ao Y., Nguyen T.K., Korsak R.A., Takeda K., Akira S., Sofroniew M.V. STAT3 is a critical regulator of astrogliosis and scar formation after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2008;28:7231–7243. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1709-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao C., Fancy S.P.J., Ffrench-Constant C., Franklin R.J.M. Osteopontin is extensively expressed by macrophages following CNS demyelination but has a redundant role in remyelination. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;31:209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sriram K., Benkovic S.A., Hebert M.A., Miller D.B., O'Callaghan J.P. Induction of gp130-related cytokines and activation of JAK2/STAT3 pathway in astrocytes precedes up-regulation of glial fibrillary acidic protein in the 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine model of neurodegeneration: key signaling pathway for astrogliosis in vivo? J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19936–19947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Acarin L., Gonzalez B., Castellano B. STAT3 and NFkappaB activation precedes glial reactivity in the excitotoxically injured young cortex but not in the corresponding distal thalamic nuclei. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:151–163. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamauchi K., Osuka K., Takayasu M., Usuda N., Nakazawa A., Nakahara N., Yoshida M., Aoshima C., Hara M., Yoshida J. Activation of JAK/STAT signalling in neurons following spinal cord injury in mice. J Neurochem. 2006;96:1060–1070. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cahoy J.D., Emery B., Kaushal A., Foo L.C., Zamanian J.L., Christopherson K.S., Xing Y., Lubischer J.L., Krieg P.A., Krupenko S.A., Thompson W.J., Barres B.A. A transcriptome database for astrocytes, neurons, and oligodendrocytes: a new resource for understanding brain development and function. J Neurosci. 2008;28:264–278. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4178-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Faulkner J.R., Herrmann J.E., Woo M.J., Tansey K.E., Doan N.B., Sofroniew M.V. Reactive astrocytes protect tissue and preserve function after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2143–2155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3547-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Williams A., Piaton G., Lubetzki C. Astrocytes–friends or foes in multiple sclerosis? Glia. 2007;55:1300–1312. doi: 10.1002/glia.20546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Albrecht P.J., Murtie J.C., Ness J.K., Redwine J.M., Enterline J.R., Armstrong R.C., Levison S.W. Astrocytes produce CNTF during the remyelination phase of viral-induced spinal cord demyelination to stimulate FGF-2 production. Neurobiol Dis. 2003;13:89–101. doi: 10.1016/s0969-9961(03)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammond T.R., Gadea A., Dupree J., Kerninon C., Nait-Oumesmar B., Aguirre A., Gallo V. Astrocyte-derived endothelin-1 inhibits remyelination through notch activation. Neuron. 2014;81:588–602. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sim F.J., Zhao C., Li W.W., Lakatos A., Franklin R.J.M. Expression of the POU domain transcription factors SCIP/Oct-6 and Brn-2 is associated with Schwann cell but not oligodendrocyte remyelination of the CNS. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:669–682. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Talbott J.F., Cao Q., Enzmann G.U., Benton R.L., Achim V., Cheng X.X., Mills M.D., Rao M.S., Whittemore S.R. Schwann cell-like differentiation by adult oligodendrocyte precursor cells following engraftment into the demyelinated spinal cord is BMP-dependent. Glia. 2006;54:147–159. doi: 10.1002/glia.20369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crang A.J., Gilson J.M., Li W.W., Blakemore W.F. The remyelinating potential and in vitro differentiation of MOG-expressing oligodendrocyte precursors isolated from the adult rat CNS. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20:1445–1460. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nave K.A., Werner H.B. Myelination of the nervous system: mechanisms and functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:503–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100913-013101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith K.J., Blakemore W.F., McDonald W.I. Central remyelination restores secure conduction. Nature. 1979;280:395–396. doi: 10.1038/280395a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blight A.R., Young W. Central axons in injured cat spinal cord recover electrophysiological function following remyelination by Schwann cells. J Neurol Sci. 1989;91:15–34. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(89)90073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherman D.L., Brophy P.J. Mechanisms of axon ensheathment and myelin growth. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:683–690. doi: 10.1038/nrn1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Funfschilling U., Supplie L.M., Mahad D., Boretius S., Saab A.S., Edgar J., Brinkmann B.G., Kassmann C.M., Tzvetanova I.D., Mobius W., Diaz F., Meijer D., Suter U., Hamprecht B., Sereda M.W., Moraes C.T., Frahm J., Goebbels S., Nave K.A. Glycolytic oligodendrocytes maintain myelin and long-term axonal integrity. Nature. 2012;485:517–521. doi: 10.1038/nature11007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]