Abstract

Endothelial cell interactions with transitional matrix proteins, such as fibronectin, occur early during atherogenesis and regulate shear stress-induced endothelial cell activation. Multiple endothelial cell integrins bind transitional matrix proteins, including α5β1, αvβ3, and αvβ5. However, the role these integrins play in mediating shear stress-induced endothelial cell activation remains unclear. Therefore, we sought to elucidate which integrin heterodimers mediate shear stress-induced endothelial cell activation and early atherogenesis. We now show that inhibiting αvβ3 integrins (S247, siRNA), but not α5β1 or αvβ5, blunts shear stress-induced proinflammatory signaling (NF-κB, p21-activated kinase) and gene expression (ICAM1, VCAM1). Importantly, inhibiting αvβ3 did not affect cytokine-induced proinflammatory responses or inhibit all shear stress-induced signaling, because Akt, endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and extracellular regulated kinase activation remained intact. Furthermore, inhibiting αv integrins (S247), but not α5 (ATN-161), in atherosclerosis-prone apolipoprotein E knockout mice significantly reduced vascular remodeling after acute induction of disturbed flow. S247 treatment similarly reduced early diet-induced atherosclerotic plaque formation associated with both diminished inflammation (expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1, plaque macrophage content) and reduced smooth muscle incorporation. Inducible, endothelial cell-specific αv integrin deletion similarly blunted inflammation in models of disturbed flow and diet-induced atherogenesis but did not affect smooth muscle incorporation. Our studies identify αvβ3 as the primary integrin heterodimer mediating shear stress-induced proinflammatory responses and as a key contributor to early atherogenic inflammation.

Although traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis, such as hypercholesterolemia and hyperglycemia, are systemic throughout the circulation, atherosclerotic plaques form at discrete areas of the vasculature where vessel geometry results in altered hemodynamics.1,2 Endothelial cells respond to the frictional force generated by these flow patterns, termed shear stress, and convert them into intracellular biochemical signals that critically modulate endothelial cell function. In straight regions of arteries, shear stress generated by unidirectional, laminar flow promotes nitric oxide production and limits endothelial cell activation, consistent with the absence of atherosclerosis in these areas.1,2 In contrast, shear stress generated by disturbed flow patterns, such as those observed at sites of vessel branch points, bifurcations, and curvatures, results in endothelial cell activation with enhanced proinflammatory gene expression [intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM1), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM1)] and permeability.1,2

In addition to flow patterns, cell matrix interactions can also affect local endothelial cell activation. Endothelial cells typically reside on basement membrane proteins (ie, collagen IV and laminin), which resist endothelial cell activation and promote a quiescent phenotype.3–5 However, during early atherogenesis, the subendothelial matrix transitions into a fibronectin and fibrinogen-rich matrix.4,6 Cell culture models suggest that transitional matrix proteins enhance the endothelial proinflammatory response to multiple atherogenic risk factors, including both shear stress and oxidized low-density lipoprotein (oxLDL).4,7 Transitional matrix proteins enhance shear stress-induced endothelial cell activation by promoting p21-activated kinase 2 (PAK2) signaling, which activates the transcription NF-κB to drive proinflammatory gene expression (ie, ICAM1 and VCAM1).5,8 Limiting fibronectin deposition, either genetically or through peptide inhibitors, blunts endothelial proinflammatory signaling (PAK2, NF-κB) and gene expression both in models of acute disturbed flow-induced vascular inflammation (partial carotid ligation) and models of diet-induced spontaneous atherosclerosis.7,9,10

The integrin family of matrix receptors consists of 18 α and 8 β subunits that assemble into 24 different integrin heterodimers with distinct matrix-binding affinities and signaling properties.11 Fluid shear stress activates multiple endothelial cell integrins, including the collagen-binding integrin α2β1 and the transitional matrix-binding integrins α5β1 and αvβ3.12 Blocking the ligation of these transitional matrix-binding integrins by using fibronectin antibodies that mask the main integrin-binding sites significantly inhibits shear stress-induced proinflammatory responses.3,4,13 However, the specific role of these transitional matrix-binding integrins in shear stress-induced endothelial cell activation remains undefined. Both α5β1 and αvβ3 show enhanced expression in the endothelial layer overlying the atherosclerotic plaque,7,14 and both α5β1 and αvβ3 are implicated in endothelial NF-κB activation in other systems.7,15 Therefore, we sought to elucidate which integrin heterodimer regulates shear stress-induced endothelial cell activation and early atherogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Endothelial Cell Culture Flow Apparatus and Transfections

Human aortic endothelial cells [HAECs; purchased from Lonza (Baltimore, MD) at passage 3] were cultured in MCDB-131 that contained 10% fetal bovine serum, 60 μg/mL heparin, 24 μg/mL bovine brain extract, 10 U/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (GIBCO, Carlsbad, CA). HAECs were used between passages 6 through 10. To perform in vitro shear stress experiments, glass slides were coated with 10 μg/mL fibronectin with or without 10 μg/mL vitronectin overnight and blocked with 0.2% bovine serum albumen. HAECs were then plated onto the slides in low serum media (0.5% to 1% fetal bovine serum) and subjected to either laminar flow (12 dynes/cm2) or oscillatory flow (±0.5 dynes/cm2 superimposed with 1 dyne/cm2) by using parallel-plate flow apparatus with the environment maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 as previously described.8 HAECs at 70% confluence were transfected with siRNA oligos to α5, αv, β3, or β5 (SMARTpool; Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) by using Lipofectamine 2000 for 2.5 hours on two consecutive days.

Immunoblotting

Cell lysis and immunoblotting were performed as previously described.4 Lysates separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and membranes were blocked in 5% nonfat dry milk before addition of primary antibodies. Antibodies include rabbit anti–phospho-Akt Thr473, rabbit anti–phospho-endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) Ser1177, rabbit anti–phospho-eNOS Thr495, rabbit anti–phospho-extracellular regulated kinase (ERK1/2), rabbit anti–phospho-focal adhesion kinase (FAK) Tyr397, rabbit anti–glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, rabbit anti–ICAM-1, rabbit anti-integrin αv, rabbit anti-integrin β3, rabbit anti-integrin β5, rabbit anti–phospho–NF-κB (p65 subunit, Ser536), rabbit anti–NF-κB (p65), rabbit anti-PAK2 (Cell Signaling Technology Inc., Danvers, MA), goat anti-Akt, rabbit anti-ERK1/2, rabbit anti-FAK, rabbit anti-integrin α5, rabbit anti–VCAM-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti–phospho-eNOS Ser633 (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA), mouse anti-eNOS (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ), and rabbit anti–phospho-PAK (Ser141; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Densitometry was performed with ImageJ software version 1.45s (NIH, Bethesda, MD; http://imagej.nih.gov/ij).

Immunocytochemistry

Endothelial cells were fixed in formaldehyde, permeabilized, and stained for the NF-κB p65 subunit (dilution 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Staining was visualized with Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies on a TiU epifluorescence microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY), and images were collected with the CoolSNAP120 ES2 camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Cells were scored as positive or negative for nuclear NF-κB staining with 100 cells counted per condition for each experiment.

qPCR

mRNA isolated from tissues and cultured endothelial cells was extracted with TRIzol (Life Technologies, Inc., Carlsbad, CA). cDNA was synthesized with the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed with a Bio-Rad iCycler with the use of SYBR Green Master mix (Bio-Rad). Primers were designed with the online Primer3 software (http://biotools.umassmed.edu/bioapps/primer3_www.cgi) and then validated by sequencing the PCR products (Table 1). Results were expressed as fold change by using the 2ΔΔCT method.

Table 1.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR Primers

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Human | ||

| GAPDH | 5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′ | 5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′ |

| B2M | 5′-AGCATTCGGGCCGAGATGTCT-3′ | 5′-CTGCTGGATGACGTGAGTAAACCT−3′ |

| ITGA1 | 5′-GCCAACCCAAAAACAGAAC-3′ | 5′-CACAAGCCAGAAATCCTCCA-3′ |

| ITGA2 | 5′-GGATTTGTTTGGCTGACTGG-3′ | 5′-TGAAGGAGTGGGAACTTTGG-3′ |

| ITGA3 | 5′-CTTCAAACGGAACCAGAGGA-3′ | 5′-ATGCCAGACTCACCCATCAC-3′ |

| ITGA4 | 5′-TCCAGAGCCAAATCCAAGAG-3′ | 5′-GCCAGCCTTCCACATAACAT-3′ |

| ITGA5 | 5′-TAGTGCCTCCCTCACCATCT-3′ | 5′-TACCCCTCCCTTCTGCTTCT-3′ |

| ITGA6 | 5′-GATAAACTGCGTCCCATTCC-3′ | 5′-TCGTCTCCACATCCCTCTTT-3′ |

| ITGA7 | 5′-CCTTTGATGGTGATGGGAAA-3′ | 5′-CAGCAGGTCAGGGTATTGGT-3′ |

| ITGA8 | 5′-GATGGTGGTGTGTGACCTTG-3′ | 5′-TGCTGTCTGGATTGTCCTTG-3′ |

| ITGA9 | 5′-AAGGCATCGGCAAGGTTTAT-3′ | 5′-AGGGCTCCATTTCCTCTGTT-3′ |

| ITGA10 | 5′-GCTCAGATGGGACAAGAAGC-3′ | 5′-CCAGTGTTGGCTATGGAACC-3′ |

| ITGA11 | 5′-GAAGGGTGGAAGGAAAGGAG-3′ | 5′-GGGTCACTGGCGATGTATTT-3′ |

| ITGAV | 5′-TGGTCTTCGTTTCAGTGTGC-3′ | 5′-TCTCCTTGTGCTCCCAGTTT-3′ |

| ITGB1 | 5′-CTGATTGGCTGGAGGAATGT-3′ | 5′-TTTCTGGACAAGGTGAGCAA-3′ |

| ITGB2 | 5′-GGTCATCTGGAAGGCTCTGA-3′ | 5′-CACCAAGTGCTCCTAACTCTCA-3′ |

| ITGB3 | 5′-CCTCCTGTCCCTCATCCATA-3′ | 5′-TCCATCCTGGCACTTATTCC-3′ |

| ITGB4 | 5′-GGAGTGTGTCCGTGTGGATA-3′ | 5′-GGTGGTGTCAATCTGGGTCT-3′ |

| ITGB5 | 5′-CAGGTTACATCGGGGACAAC-3′ | 5′-ACGCAATCTCTCTTGGTGCT-3′ |

| ITGB6 | 5′-ATGGGGATTGAACTGCTTTG-3′ | 5′-AAGGTTTGCTGGGGTATCAC-3′ |

| ITGB7 | 5′-GTCGCAGCACAGAGTTTGAC-3′ | 5′-CCAGGAGGGAGTGAAGAGTG-3′ |

| ITGB8 | 5′-CGAGGAGTTTGTGTTTGTGG-3′ | 5′-CACTGAAGCATTGGCATCTG-3′ |

| VCAM1 | 5′-ATGAGGGGACCACATCTACG-3′ | 5′-CACCTGGATTCCTTTTTCCA-3′ |

| ICAM1 | 5′-TGTCCCCCTCAAAAGTCATC-3′ | 5′-TAGGCAACGGGGTCTCTATG-3′ |

| Mouse | ||

| B2m | 5′-TTCTGGTGCTTGTCTCACTGA-3′ | 5′-CAGTATGTTCGGCTTCCCATTC-3′ |

| Vcam1 | 5′-TCAAAGAAAGGGAGACTG-3′ | 5′-GCTGGAGAACTTCATTATC-3′ |

| Icam1 | 5′-GTGATGCTCAGGTATCCATCCA-3′ | 5′-CACAGTTCTCAAAGCACAGCG-3′ |

| Itga5 | 5′-CGTTGAGTCATTCGCCTCTGG-3′ | 5′-GTGCCCGCTCTTCCCTGTC-3′ |

| Itgav | 5′-TCCATTGTACCACTGGAGGA-3′ | 5′-TTTGACCTGCATGGAGCATA-3′ |

| Klf2 | 5′-AGAATGCACCTGAGCCTGCTAG-3′ | 5′-AATTTCCCCGAAAGCCTGC-3′ |

Animals and Tissue Harvest

The Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center-Shreveport Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal protocols, and all animals were cared for according to the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.16 Male Apoe−/− mice on the C57Bl/6J genetic background were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice that contained the αvfl/fl allele (a gift from Dr. Richard Hynes, MIT, Cambridge, MA) and mice that contained the vascular endothelial (VE)-cadherinCreERT2 transgene (a gift of Dr. Luisa Iruela-Arispe, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA), both on the C57Bl/6J background, were crossed with Apoe−/−.17,18

Genotype was determined by PCR reactions by using DNA isolated from tail snips and genotyping primers (Apoe forward common, 5′-GCCTAGCCGAGGGAGAGCCG-3′; Apoe wild-type reverse, 5′-GCCGCCCCGACTGCATCT-3′; Apoe mutant reverse, 5′-TGTGACTTGGGAGCTCTGCAGC-3′; ITGAV forward, 5′-TTCAGGACGGCACAAAGACCGTTG-3′; ITGAV reverse, 5′-CACAAATCAAGGATGACCAAACTGAG-3′; Cf, 5′-ACTGGGATCTTCGAACTCTTTGGAC-3′; Cr, 5′-GATGTTGGGGCACTGCTCATTCACC-3′; Cref, 5′-CCATCTGCCACCAGCCAG-3′; Crer, 5′-TCGCCATCTTCCAGCAGG-3′) as previously described.17

Male inducible epithelial cell (iEC)-αv knockout (KO) mice (Apoe−/−, VE-cadherinCreERT2tg/?, αvfl/fl) and iEC-Control (Apoe−/−, VE-cadherinCreERT2tg/?) mice were treated with 1 mg/kg tamoxifen i.p. (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) every other day for five total injections to induce Cre expression and αv excision. Eight- to 10-week-old mice were fed a high-fat, Western diet (TD 88137; Harlan-Teklad, Madison, WI) that contained 21% fat by weight (0.15% cholesterol and 19.5% casein without sodium cholate) for 8 weeks. Mice were then euthanized by pneumothorax under isoflurane anesthesia, and blood was collected. Total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (Wako Bioproducts, Richmond, VA), and triglycerides (Pointe Scientific, Canton MI) were analyzed with commercially available kits. LDL cholesterol was calculated with the Friedewald equation.

Hearts were then perfused with phosphate-buffered saline to remove residual blood from the circulation. The lungs were collected for enzymatic digestion and endothelial cell isolation by using magnetic beads coupled to ICAM2 antibodies (eBiosource, San Diego, CA).19 The left common carotid was collected for mRNA isolation by TRIzol flush as previously described.20 Briefly, carotids were cleaned of perivascular adipose tissue and flushed with 150 μL TRIzol from an insulin syringe. The remaining media/adventitia were then placed in 150 μL TRIzol and sonicated to lyze the tissue. Samples were then frozen until analysis by qPCR. The aortic root, aorta, and carotid sinus were excised, placed in 3.7% phosphate-buffered saline–buffered formaldehyde, and analyzed for plaque size and composition.

Surgical Procedures

After 4 weeks of feeding a Western diet to the Apoe−/− mice, Alzet (Cuperino, CA) pumps (Micro-Osmotic Pump, Model 1004) that contained either saline or 40 mg/kg/day S247 were implanted under isoflurane anesthesia (5% on induction; 2% for maintenance during surgery), and the Western diet feeding was resumed for an additional 4 weeks. To analyze endothelial activation by low flow, partial ligation of the left carotid artery was performed as previously described.20 Briefly, a 4- to 6-mm vertical incision on the skin was made, and blunt dissection was used to expose the left carotid artery. Subsequently, the external, internal, and occipital arteries were ligated with 7-0 silk suture. The incision was sutured and then closed with a small amount of tissue glue followed by suturing the incision. For the integrin inhibitor studies, mice were implanted with Alzet pumps (Micro-Osmotic pump, Model 1007D) that contained either saline or S247 immediately after the ligation or given 5 mg/kg ATN-161 three times per week by i.p. injection. At the start of surgery, a single injection of 0.1 mg/kg buprenorphine or 5 mg/kg carprofen was given, and recovery of the mice was monitored on a heating pad. All ultrasound measurements were taken with a VEVO 770 high-resolution in vivo microimaging ultrasound system with a 30-MHz mouse probe (VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada). Echocardiography was performed on the left and right carotid arteries 1 day after the partial ligation surgery. Mice were euthanized after 48 hours for mRNA analysis after TRIzol flush of the left and right carotid and after 7 days for immunohistochemical analysis of the left and right carotids excised for analysis.

Immunohistochemistry for Tissue

All tissue was fixed in 4% formaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5-μm sections. Immunohistochemistry and Russell-Movat Pentachrome staining was performed as previously described.7 Antibodies used for mouse tissues included rabbit anti–VCAM-1 (dilution 1:40 or 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), rat anti-Mac2 (dilution 1:10,000; Accurate Chemical, Westbury, NY), and mouse anti-smooth muscle actin (SMA; dilution 1:400; Sigma-Aldrich). Staining was visualized with Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies. Images were collected with the Photometrics CoolSNAP120 ES2 camera and the NIS Elements 3.00 by using SP5 imaging software.

Statistical Analysis

Data were tested for normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) and significance by using Prism software version 5.02 (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA). Data that passed the normality assumption were analyzed with t-test or two-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post-tests. Data that failed the normality assumption were analyzed with the nonparametric U-test and the Kruskal Wallis test with post hoc analysis. Data are expressed as means ± SEM. Differences were considered statistically significant at a value of P < 0.05.

Results

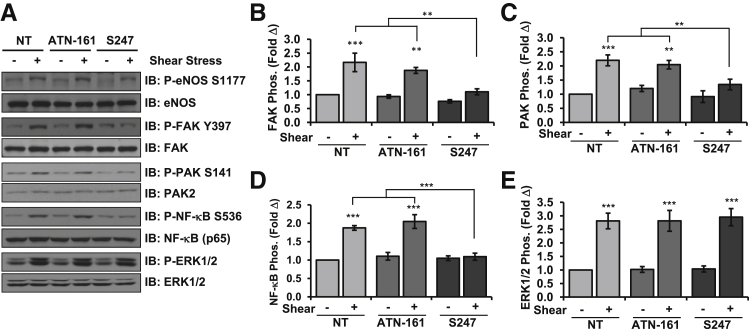

Although chronic exposure to laminar flow reduces inflammatory signaling,1 acute onset of laminar flow stimulates proinflammatory signaling pathways and ICAM-1/VCAM-1 expression similar to disturbed flow models. Therefore, we first sought to determine how individual transitional matrix integrins contribute to endothelial cell activation by acute onset of flow. Consistent with previous reports,21 qPCR analysis of HAECs indicated the expression of multiple transitional matrix-binding integrins, including the binding partners α5β1, αvβ3, and αvβ5 (Supplemental Figure S1). To test which of these transitional matrix-binding integrins mediate flow-induced endothelial cell activation, we used specific small-molecule inhibitors or competitive peptides to block integrin signaling. HAECs plated on the transitional matrix protein fibronectin were treated with either 50 μmol/L α5β1 signaling inhibitor ATN-1617 or 1 μmol/L αv inhibitor S247,22 and shear stress-induced signaling was assessed. Although an RGD peptidomimetic, S247 shows a 160-fold higher affinity for αvβ3 than for α5β1 and a 950-fold higher affinity for αvβ3 than for the platelet integrin αIIbβ3.22 Inhibiting αv integrins with S247 completely suppressed shear-induced activation of FAK (Figure 1, A and B), PAK2 (Figure 1, A and C), and NF-κB (Figure 1, A and D), whereas ATN-161 did not. In contrast, neither inhibitor affected shear stress-induced activation of ERK1/2 (Figure 1, A and E) or Akt (Supplemental Figure S2, A and B), and neither affected shear-induced eNOS Ser1177 phosphorylation (Figure 1A and Supplemental Figure S2C) or Thr495 dephosphorylation (Supplemental Figure S2, A and D). However, shear stress-induced eNOS phosphorylation on Ser633 showed significant reductions with S247 treatment but not ATN-161 (Supplemental Figure S2, A and E).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of αv but not α5 integrins blunts shear stress-induced NF-κB activation. A: Human aortic endothelial cells on fibronectin were treated with 50 μmol/L ATN-161 or 1 μmol/L S247 and exposed to acute onset of flow for 30 minutes. Activation of eNOS, FAK, PAK2, and NF-κB was assessed by Western blot analysis with phospho-specific antibodies and normalized to total protein levels. Representative blots are shown. Quantification of shear-induced activation of FAK (B), PAK2 (C), NF-κB (D), and ERK1/2 (E) is shown. n = 4 (B and E); n = 5 (C); n = 7 to 11 (D). ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ERK, extracellular regulated kinase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; IB, immunoblot; NT, no treatment; PAK2, p21-activated kinase 2.

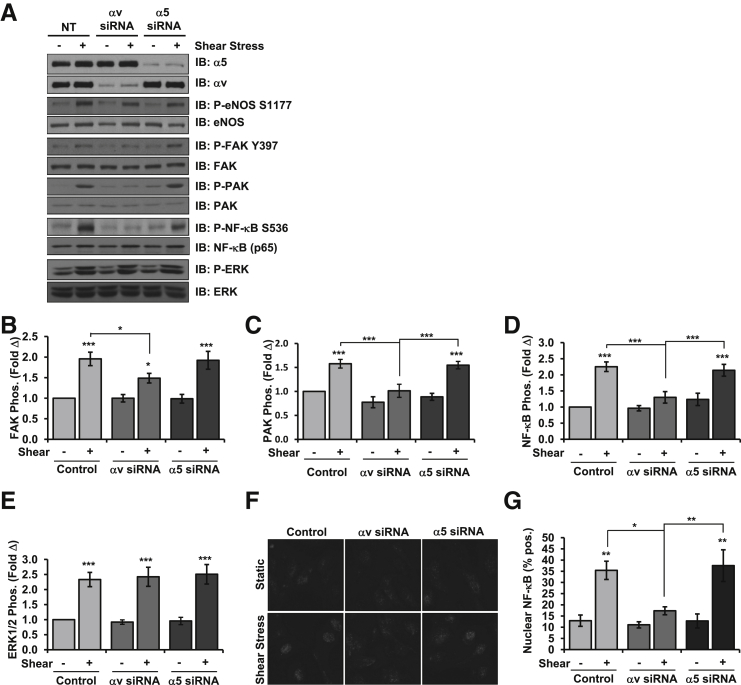

To confirm these results, endothelial cells were transfected with α5 and αv siRNA to selectively deplete these integrins. Knockdown efficiencies were similar with an approximately 80% knockdown of each integrin, and no compensation was observed after knockdown of either integrin (Supplemental Figure S3, A and B). Consistent with the integrin inhibitor studies, siRNA targeting integrin αv similarly prevented shear-induced activation of FAK (Figure 2, A and B), PAK (Figure 2, A and C), and NF-κB (Figure 2, A and D), whereas α5 siRNA did not. Integrin depletion did not prevent all shear stress responses, because shear stress induced a similar activation of ERK1/2 (Figure 2, A and E) and Akt (Supplemental Figure S3, A and C), as well as eNOS Ser1177 phosphorylation (Figure 2A and Supplemental Figure S3, A and D) and Thr495 dephosphorylation (Supplemental Figure S3, A and D), irrespective of integrin siRNA. Like the inhibitor studies, αv siRNA significantly reduced shear-induced eNOS phosphorylation on Ser633 (Supplemental Figure S3, A and F), confirming a role for this integrin in eNOS phosphorylation at this site. To further confirm altered proinflammatory NF-κB activation on αv depletion, we assessed NF-κB nuclear translocation by immunocytochemistry. Like NF-κB phosphorylation, depleting αv integrins blunted shear stress-induced NF-κB nuclear translocation, whereas α5 depletion did not (Figure 2, F and G). Taken together, these data indicate that αv integrins are the predominant integrin that mediate endothelial NF-κB activation after acute onset of shear stress.

Figure 2.

Selective knockdown of αv integrins blunts shear stress-induced NF-κB activation. A: HAECs were transfected with siRNA for α5 or αv integrins, plated on fibronectin, and exposed to acute onset of shear stress for 30 minutes. Integrin expression was determined by Western blot analysis and shear-induced activation of eNOS, FAK, PAK2, and NF-κB was assessed by Western blot analysis with phospho-specific antibodies and normalized to total protein levels. Representative blots are shown. Quantification of shear-induced activation of FAK (B), PAK2 (C), NF-κB (D), and ERK1/2 (E) is shown. F and G: HAECs were treated as in A–E, and NF-κB activation was determined by immunocytochemistry for NF-κB nuclear translocation. Representative micrographs are shown. F: Quantification of nuclear translocation as described in E. HAECs were scored for nuclear NF-κB staining, at least 100 cells were counted per condition for each experiment. n = 5 (B); n = 8 (C–E); n = 4 (F). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ERK, extracellular regulated kinase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; HAEC, human aortic endothelial cell; IB, immunoblot; NT, no treatment; PAK2, p21-activated kinase 2; Pos, positive.

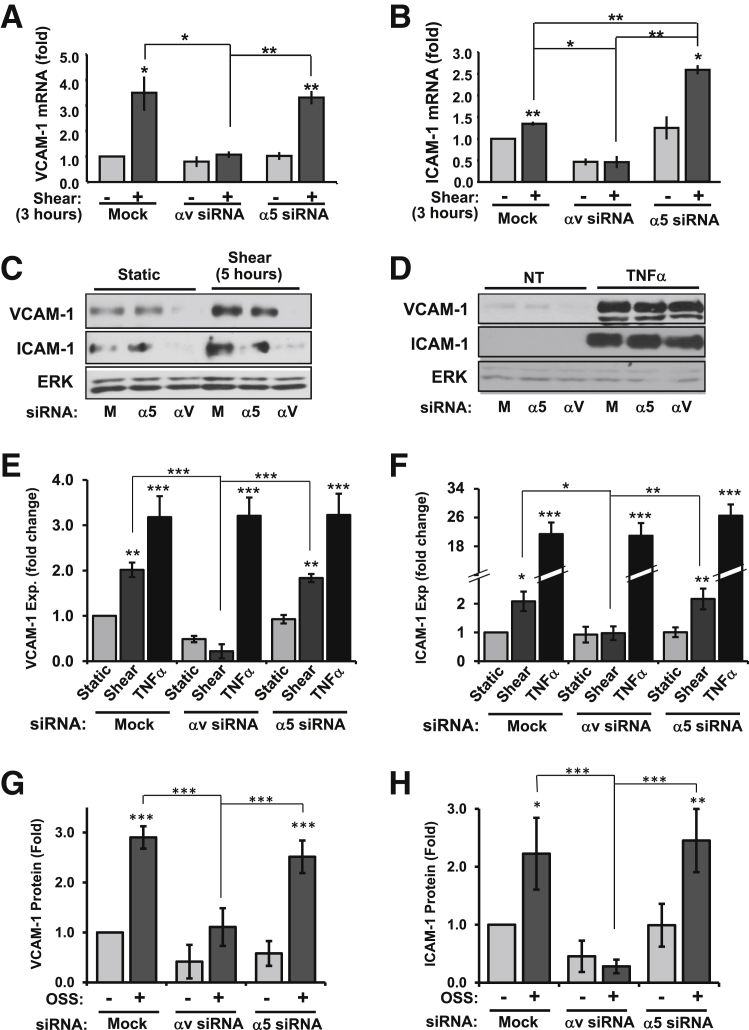

In addition to proinflammatory signaling, we measured shear stress-induced expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, the major adhesion molecules that mediate leukocyte firm adhesion. HAECs treated with α5 or αv siRNA were exposed to onset of shear stress for 3 hours, and ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 mRNA expression was assessed by qPCR. Consistent with αv integrin-dependent NF-κB activation, shear stress-induced VCAM-1 mRNA was completely inhibited by αv siRNA, whereas α5 siRNA did not affect VCAM-1 expression (Figure 3A). Although ICAM-1 expression showed a milder induction than VCAM-1, αv siRNA completely suppressed this induction and α5 siRNA actually enhanced this expression (Figure 3B). Shear stress-induced VCAM-1 (Figure 3, C and E) and ICAM-1 (Figure 3, C and F) protein expression showed similar inhibition by integrin αv knockdown but not α5 knockdown (Figure 3, C and D). Neither α5 siRNA nor αv siRNA affected tumor necrosis factor-α–induced VCAM-1 (Figure 3, D and E) and ICAM-1 expression (Figure 3, D and F), suggesting that αv integrin knockdown does not suppress endothelial cell activation in response to other proinflammatory stimuli.

Figure 3.

αv Integrin knockdown inhibits shear stress-induced ICAM-1/VCAM-1 expression. HAECs were transfected with siRNA for α5 or αv integrins, plated on fibronectin, and exposed to laminar shear stress for 3 hours. VCAM-1 (A) and ICAM-1 (B) mRNA was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR and normalized to β2-microglobulin expression. C–F: HAECs transfected with α5 or αv siRNA were plated on fibronectin and exposed to either laminar shear stress or 10 ng/mL TNFα for 5 hours. Cells were lyzed and analyzed for VCAM-1 (E) or ICAM-1 (F) expression by Western blot analysis. Representative blots are shown (C and D). G and H: HAECs transfected with α5 or αv siRNA were plated on fibronectin and exposed to OSS for 18 hours. Cells were lyzed and analyzed for VCAM-1 (G) or ICAM-1 (H) expression by Western blot analysis. n = 4 (B, G, and H); n = 4 to 7 (C and D). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. ERK, extracellular regulated kinase; Exp, expression; HAEC, human aortic endothelial cell; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; M, mock; NT, no treatment; OSS, oscillatory shear stress; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-α; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

Although acute onset of flow provides an easily reproducible model for shear stress signaling, endothelial cells at atherosclerosis-prone sites in vivo are chronically exposed to disturbed flow patterns. To determine whether integrin-specific signaling similarly regulates the chronic inflammation seen in disturbed flow models, α5 and αv knockdown HAECs were exposed to oscillatory shear stress (model of disturbed flow2,8) for 18 hours. Similar to the onset of flow, knockdown of αv integrins but not α5 integrins inhibited flow-induced VCAM-1 (Figure 3G) and ICAM-1 protein expression (Figure 3H). Taken together, these results identify αv integrins as the major mediators of flow-induced endothelial cell activation on fibronectin.

Although the present data implicate αv integrins in the proinflammatory response to flow, the specific heterodimer involved remains unknown. Because the αv subunit forms heterodimers with both β3 and β5 integrin subunits, we used siRNA to β3 and β5 to determine their individual roles. Although fibronectin can bind to both αvβ3 and αvβ5,23 both fibronectin and vitronectin were included in the subendothelial matrix to ensure both integrins had high-affinity ligands present. Knockdown of β3 integrins significantly blunted flow-induced NF-κB phosphorylation (Figure 4, A and B), whereas β5 knockdown did not. Furthermore, β3 knockdown reduced the expression of both VCAM-1 (Figure 4C) and ICAM-1 (Figure 4D) by acute onset of flow, whereas knockdown of β5 did not affect shear stress-induced expression of either protein. Consistent with this result, β3 but not β5 siRNA suppressed chronic oscillatory shear stress-induced VCAM-1 (Figure 4E) and ICAM-1 (Figure 4F) expression. Taken together, these data suggest that shear stress induces proinflammatory gene expression through αvβ3 integrin signaling.

Figure 4.

β3 siRNA limits shear-induced proinflammatory signaling and gene expression. A and B: HAECs were transfected with siRNA for β3 or β5 integrins, plated on a fibronectin and vitronectin matrix, and exposed to acute onset of flow for 30 minutes. NF-κB phosphorylation was determined by Western blot analysis. Representative images are shown. B: Quantification of NF-κB phosphorylation from A normalized to total NF-κB levels. HAECs treated as in A were exposed to laminar shear stress for 5 hours, and expression of VCAM-1 (C) and ICAM-1 (D) was determined by Western blot analysis. HAECs treated as in A were exposed to OSS for 18 hours and expression of VCAM-1 (E) and ICAM-1 (F) was determined by Western blot analysis. n = 4 (B–F). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. Exp, expression; HAEC, human aortic endothelial cell; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; M, mock; OSS, oscillatory shear stress; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

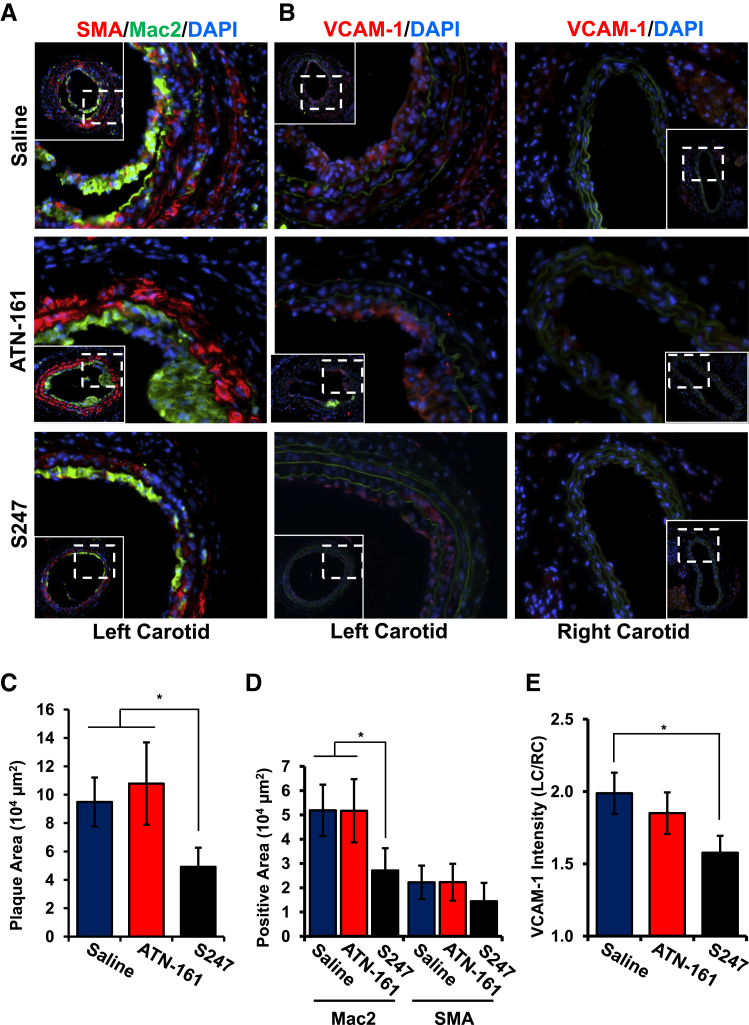

Because our in vitro data suggest that αv integrins, but not α5β1, mediate the proinflammatory effects of shear stress, we next tested whether inhibiting αv or α5 integrins affects inflammation in the partial carotid ligation model of disturbed flow-induced early atherogenic remodeling.20 Atherosclerosis-prone apolipoprotein E (ApoE) KO mice underwent partial ligation of the left carotid artery, resulting in the development of low, oscillatory flow in the common carotid artery. The right carotid, still exposed to uniform laminar flow, was used as a negative control. Immediately after ligation, mice were treated with 40 mg/kg per day αv integrin inhibitor S247 or vehicle control via Alzet osmotic minipump or were treated with 5 mg/kg α5β1 inhibitor ATN-161 (i.p. injection, every 3 days). After 7 days, disturbed flow-induced plaque formation in the left carotid, quantified as neointimal area, was significantly reduced by the S247 treatment but not the ATN-161 treatment (Figure 5, A and C). No plaque formation was detected in the right carotid artery in any of the mice regardless of treatment. The early plaques that form in this model are predominantly composed of macrophages (Mac2-positive), although smooth muscle (SMA-positive) recruitment was consistently observed (Figure 5A). Although ATN-161 did not affect plaque macrophage or smooth muscle area, S247 treatment significantly reduced plaque macrophage area and showed a trend toward reduced smooth muscle area, although this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 5D). To assess endothelial cell activation, we analyzed VCAM-1 expression by immunohistochemistry. In addition to endothelial VCAM-1 expression (Figure 5B), we observed VCAM-1 expression in the neointima and the medial layer underlying the plaque, consistent with previous reports.24 In congruence with our in vitro studies, S247 but not ATN-161 significantly reduced VCAM-1 staining throughout these vessels (Figure 5, B and E).

Figure 5.

S247 limits inflammation after partial carotid ligation in ApoE knockout mice. A and B: ApoE knockout mice underwent partial ligation of their left carotid artery and treatment with saline, ATN-161 (5 mg/kg every third day), or S247 (40 mg/kg per day). After 7 days, plaque area in the left carotid artery exposed to disturbed flow was determined by immunohistochemistry for Mac2 (green; A) and SMA (red; A) or VCAM-1 (B) by using nuclear staining (DAPI, blue) as a counterstain. Representative micrographs from serial sections are shown. C: Quantification of total plaque area. D: Quantification of Mac2-positive and SMA-positive area. E: VCAM-1 intensity in the left carotid artery was quantified and normalized to VCAM-1 in the right carotid artery exposed to laminar shear stress. n = 5 to 9 mice per group (A, B, and E). ∗P < 0.05. ApoE, apolipoprotein E; Mac2, macrophage; SMA, smooth muscle area; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

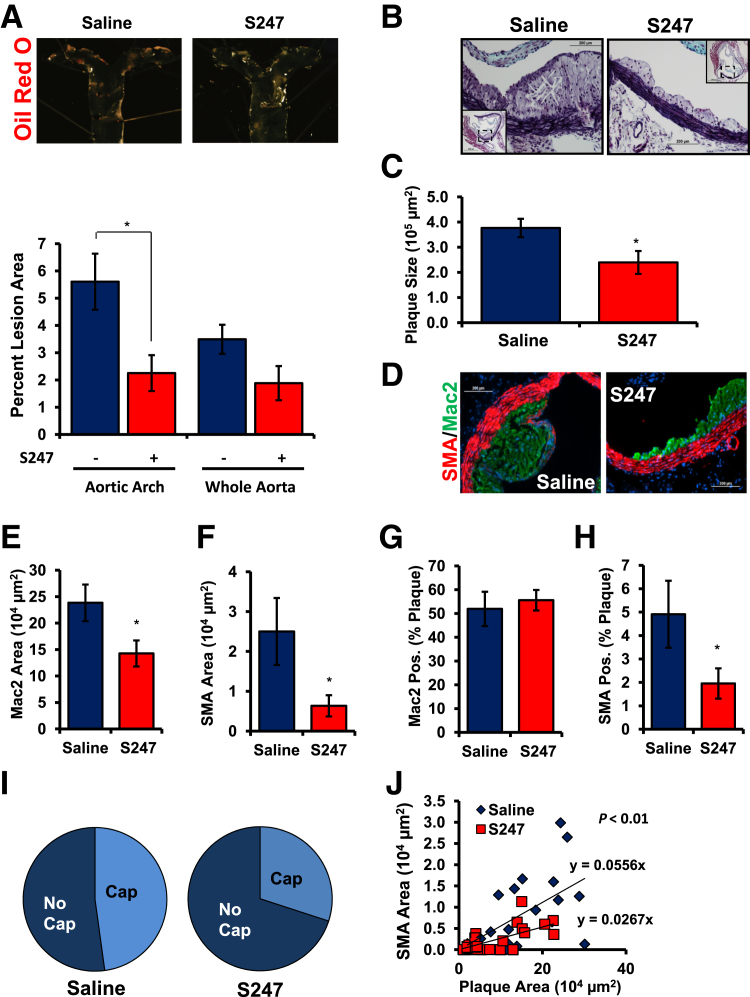

Although several studies have tested the role of αvβ3 inhibitors in atherosclerotic plaque formation, the models used (advanced atherosclerotic disease, vessel injury) limited their ability to assess effects on endothelial cell activation.25–27 To investigate whether S247 treatment similarly reduced spontaneous plaque formation at sites of disturbed flow, we stimulated atherosclerosis in male ApoE KO mice by feeding mice a high-fat, Western diet for 8 weeks during which time the mice were treated with either saline or 40 mg/kg/day S247 by osmotic mini-pump for the final 4 weeks. Atherosclerotic plaque formation was then assessed in the aorta, aortic root, and carotid sinus. S247 treatment did not affect total plasma cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, or triglyceride concentrations (Table 2), but significantly reduced Oil Red O-positive atherosclerotic plaques in the aortic arch with a trend for reduced plaque in the whole aorta (Figure 6A). S247 treatment similarly reduced total plaque area in the aortic root (Figure 6, B and C) and carotid sinus (Supplemental Figure S4, A and B). Taken together, these data suggest that inhibiting αv integrins blunts early plaque formation without affecting circulating atherosclerotic risk factors.

Table 2.

Plasma Lipids after S247 Treatment

| Lipid | Saline | S247 |

|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1015.1 ± 107.2 | 1089.6 ± 116.0 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 21.0 ± 2.6 | 25.6 ± 5.1 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 946.6 ± 94.7 | 1025.7 ± 147.8 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 236.9 ± 67.8 | 186.5 ± 50.7 |

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Figure 6.

S247 limits spontaneous atherosclerosis in Western diet-fed Apoe knockout mice. Apoe knockout mice were fed a high-fat, Western diet for 8 weeks and treated with saline or 40 mg/kg per day S247 for the final 4 weeks. A: Oil Red O staining of the aortic arch was performed to visualize plaque formation by en face imaging. Quantification of Oil Red O-positive areas in the aortic arch or whole aorta from the aortic cusp to renal branchpoints is shown. B and C: Analysis of atherosclerotic plaque area in the aortic root by Russell-Movat Pentachrome staining. Representative images are shown with insets of the entire vessel. Quantification of plaque cross-sectional area determined at multiple regions along the aortic root (C). D: Representative micrographs of plaques from the aortic root were analyzed for Mac2 area (green) and SMA (red), using nuclear staining (DAPI, blue) as a counterstain. E: Quantification of Mac2-positive area. F: Quantification of SMA-positive. Percentage of the atherosclerotic plaque that stained positive for either Mac2 (G) or SMA (H). I: Plaques were scored as either positive or negative for SMA-containing fibrous caps and the percent positive are shown with a pie graph. J: Scatter plots for the relation between SMA and plaque area. The slopes showing the relation between plaque size and SMA are shown. n = 5 mice per group. n = 23 to 30 plaques from 4 to 5 mice per condition (I). ∗P < 0.05. Original magnification: ×40 (B and C, main images); ×10 (insets). Mac2, macrophage; SMA, smooth muscle area.

We next determined whether S247 treatment altered the composition of the plaques that formed. Macrophage area (Mac2-positive) and smooth muscle area (SMA-positive) in plaques from the aortic root were determined by immunohistochemistry and quantified at multiple sites along each vessel. Plaques treated with S247 showed a significant reduction in both macrophage area (Figure 6, D and E) and smooth muscle area (Figure 6, D and F), consistent with diminished plaque size. Macrophages constitute the bulk of the plaque at this stage, and the percentage of plaque area positive for Mac2 did not change with the S247 treatment (Figure 6G), suggesting that reduced macrophage area likely drives the reduction in overall plaque size. Although smooth muscle cells make up a much lower proportion of the plaque at this stage, S247 treatment reduced the percentage of the plaque staining positive for SMA (Figure 6H). Consistent with these results, S247 treatment reduced the percentage of atherosclerotic plaques that showed SMA-positive fibrous caps (Figure 6I). Scatter plots showing the relation between plaque size and SMA-positive area (23 to 30 plaques from four to five mice per condition) suggest that the effect of S247 treatment on smooth muscle incorporation is not simply due to reduced plaque size, because the slope showing the relation between plaque area and SMA staining area is significantly reduced (P = 0.003) after S247 treatment (Figure 6J). Taken together, these data suggest that S247 treatment likely reduces plaque size by reducing both macrophage and smooth muscle content.

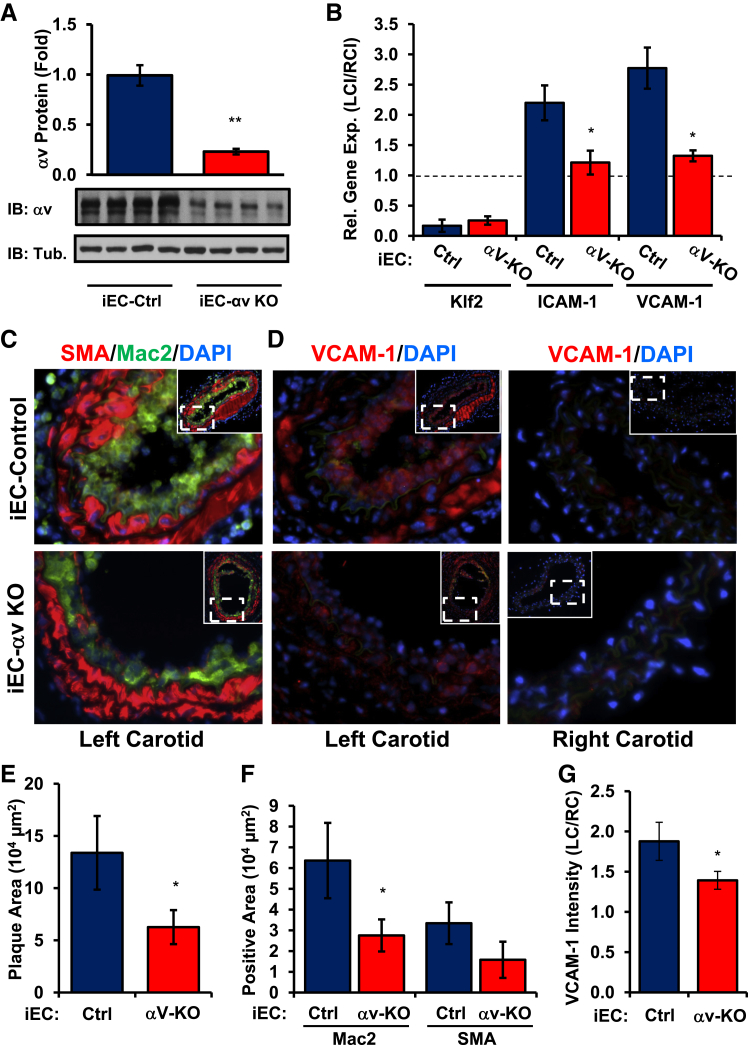

Because S247 likely affects atherogenic inflammation and vascular remodeling through effects on multiple cell types, we next sought to test the role of endothelial αv integrins directly. Apoe−/− mice that express the tamoxifen-inducible, endothelial cell-specific Cre transgene (Apoe−/−, VE-cadherinCreERT2tg/?; iEC-Control) were crossed with mice that contained a floxed αv integrin allele (Apoe−/−, VE-cadherinCreERT2tg/?, αvflox/flox; iEC-αv KO) to allow for tamoxifen-dependent deletion of αv in endothelial cells. Tamoxifen treatment significantly reduced αv mRNA in the intima of the common carotid in iEC-αv KO mice compared with iEC-Control mice (Supplemental Figure S4C), whereas medial/adventitial αv expression remained unaffected. To confirm αv protein depletion, endothelial cells were isolated from the mouse lung after tamoxifen treatment, and αv expression was assessed by Western blot analysis. Consistent with the mRNA data, endothelial cells isolated from tamoxifen-treated iEC-αv KO mice showed a significant reduction in αv protein expression compared with controls (Figure 7A).

Figure 7.

Reduced inflammation after partial carotid ligation in iEC-αv KO mice. A: After tamoxifen treatment, lung endothelial cells were isolated to analyze αv protein levels by Western blot analysis. B: iEC-Control and iEC-αv KO mice underwent partial carotid ligation, and the intimal mRNA was isolated after 48 hours. Expression of Klf2, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. C and D: After 7 days, plaque area in the left carotid artery was determined by immunohistochemistry for Mac2 (green, C) and SMA (red, C) or VCAM-1 (D) by using nuclear staining (DAPI, blue) as a counterstain. Representative micrographs from serial sections are shown. E: Quantification of total plaque area. F: Quantification of Mac2-positive and SMA-positive area. G: VCAM-1 intensity in the left carotid artery was quantified and normalized to VCAM-1 in the right carotid artery exposed to laminar shear stress. n = 4 mice per group (A), n = 5 mice per group (B–D and G). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. Original magnification: ×40 (C and D); ×10 (C and D, insets). Ctrl, control; IB, immunoblot; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; iEC, inducible epithelial cell; Klf2, Krüppel-like Factor 2; KO, knockout; LC, left carotid; Mac2, macrophage; RC, right carotid; SMA, smooth muscle area; Tub, tubulin; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

To assess the role of αv in the endothelial cell response to shear stress, iEC-Control and iEC-αv KO mice underwent partial carotid ligation surgery, and changes in endothelial mRNA expression (48 hours after ligation) and vessel remodeling (7 days after ligation) were determined. Consistent with our cell culture system, disturbed flow induced a greater than twofold induction of both ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 mRNA expression in iEC-Control mice, but iEC-αv KO mice showed no induction of either gene by disturbed flow (Figure 7B). Analysis 7 days after ligation indicated a significant reduction in plaque size in iEC-αv KO mice (Figure 7, C and E), associated with a reduction in macrophage area (Figure 7, C and F). Consistent with the mRNA analysis, iEC-αv KO mice showed a significant reduction in VCAM-1 staining in the left carotid compared with the right carotid control (Figure 7, D and G). However, this analysis was not limited to the endothelium and may result from an overall decrease in inflammation in the vessel wall after endothelial αv deletion.

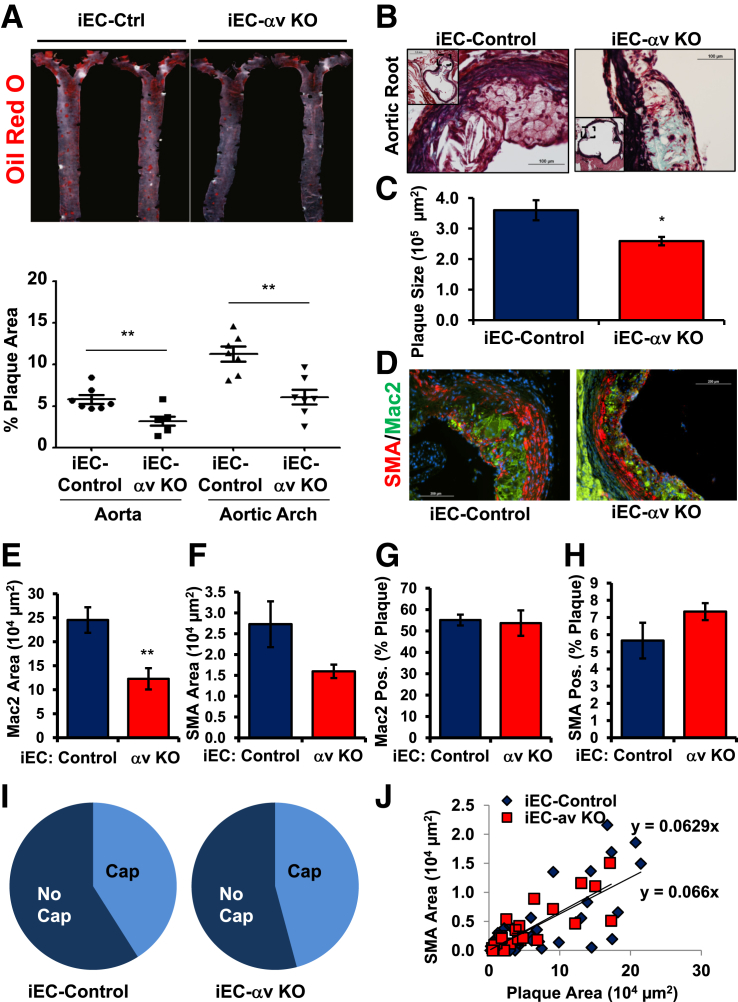

Atherosclerotic plaque formation in iEC-Control and iEC-αv KO mice was assessed after 8 weeks of Western diet feeding. Although total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein, and LDL cholesterol concentrations did not differ significantly between iEC-Control and iEC-αv KO mice (Table 3), plaque formation in the aorta (Figure 8A), aortic root (Figure 8, B and C), and the carotid sinus (Supplemental Figure S4, D and E) were all reduced in iEC-αv KO mice compared with iEC-Control mice. Like the S247 treatment, the reduction in plaque formation in iEC-αv KO mice was associated with reduced macrophage area (Figure 8, D and E) and a trend toward reduced smooth muscle area, although this did not reach statistical significance (Figure 8, D and F). Neither S247 treatment nor iEC-αv KO reduced the percentage of plaques positive for the macrophage marker Mac2 (Figures 6G and 8G), consistent with macrophage-dominant plaques at this stage. However, unlike the S247 treatment, iEC-αv KO mice showed no change in the percentage of plaque area positive for SMA (Figure 8H), the percentage of plaques positive for fibrous caps (Figure 8I), or the correlation between plaque size and smooth muscle area (Figure 8J), suggesting that endothelial αv integrins do not regulate smooth muscle incorporation into the plaque.

Table 3.

Plasma Lipids in iEC-αv KO Mice

| Lipid | iEC-control | iEC-αv KO |

|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 1309.8 ± 136.3 | 1255.3 ± 153.6 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 32.3 ± 2.9 | 32.8 ± 5.2 |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 1232.6 ± 131.5 | 1187.4 ± 148.2 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 224.7 ± 22.2 | 173.7 ± 25.3 |

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; iEC, inducible epithelial cell; KO, knockout; LDL, low-density lipoprotein.

Figure 8.

Endothelial αv deletion limits spontaneous atherosclerosis. iEC-Control and iEC-αv KO mice were treated with tamoxifen, and atherosclerosis was induced by Western diet feeding for 8 weeks. A: Oil Red O staining of the aortic arch was performed to visualize plaque formation by en face imaging. Quantification of Oil Red O-positive areas in the aortic arch or whole aorta from the aortic cusp to renal branchpoints is shown. B: Representative images show analysis of atherosclerotic plaque area in the aortic root by Russell-Movat Pentachrome staining. C: Quantification of plaque cross-sectional area determined at multiple regions along the aortic root. D: Representative micrographs of the plaques from the aortic root were analyzed for Mac2 (green) and SMA (red) areas, using nuclear staining (DAPI, blue) as a counterstain. E: Quantification of Mac2-positive area. F: Quantification of SMA-positive. Percentage of the atherosclerotic plaque staining positive for either Mac2 (G) or SMA (H). I: Plaques were scored as either positive or negative for SMA-containing fibrous caps and the percent positive is shown with a pie graph. J: Scatter plots for the relation between SMA and plaque area. The slopes show the relation between plaque size and smooth muscle. n = 7 mice per group; n = 24 to 39 plaques from 6 to 7 mice per condition (I and J). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. Original magnification: ×40 (main images); ×10 of the entire vessel (inset). iEC, inducible epithelial cell; KO, knockout; Mac2, macrophage; Pos, positive; SMA, smooth muscle area.

Discussion

Integrin signaling plays a well-characterized role in mechanotransduction, including the endothelial cell response to shear stress.1,2 Therefore, it is not surprising that changes in matrix composition significantly affect the endothelial cell response to shear stress through the activation of integrin-specific signaling. Although work from our laboratory and others have defined an important role for endothelial matrix remodeling in shear stress-induced endothelial activation4,7 and early atherogenesis,7,9,10 the role of specific integrins in mediating this response remained undefined. We now show that fibronectin deposition enhances the proinflammatory effects of shear stress, predominantly through the αvβ3 integrin. Both inhibitor studies (S247) and siRNA knockdown (αv, β3) experiments show that blocking signaling through αvβ3 prevents flow-induced NF-κB activation and proinflammatory gene expression (ICAM-1, VCAM-1). Inhibiting αvβ3 similarly blunted shear stress-induced activation of FAK and PAK, pathways known to mediate integrin-dependent NF-κB activation by shear.8,28 The requirement for αvβ3 is consistent between the responses to early onset of flow and those seen with chronic oscillatory flow, and αvβ3 is not required for tumor necrosis factor-α–induced proinflammatory gene expression, suggesting that αvβ3 inhibition does not regulate endothelial cell activation in response to all proinflammatory stimuli. We further show that inhibiting αv integrins, either with S247 or in the iEC-αv KO mice, significantly blunts inflammation in the partial carotid ligation model of oscillatory flow-induced vascular remodeling in vivo, whereas inhibiting α5 did not. iEC-αv KO mice and mice treated with S247 showed similarly reduced inflammation and plaque formation at sites of disturbed flow during diet-induced early atherogenesis. However, S247 treatment also blunted smooth muscle recruitment into the developing plaque.

Integrins function as classic mechanotransducers, coupling mechanical forces transmitted through the extracellular matrix to the activation of intracellular biochemical signals.1,2 However, shear stress stimulates integrin signaling indirectly by inducing inside-out integrin activation, enhancing their affinity for their matrix ligands, and stimulating ligation-dependent outside-in integrin signaling.12,29,30 Fibronectin-binding integrins mediate shear stress-induced endothelial alignment, permeability, and proinflammatory gene expression.4,13,30 In the present work, we build on this understanding by examining how specific integrins contribute to the endothelial response to shear stress. Inhibiting αvβ3 (S247, siRNA) blunted shear stress-induced NF-κB activation and activation of FAK and PAK, pathways previously shown to mediate shear-induced NF-κB activation.8,28 However, shear-induced activation of ERK1/2, AKT, and eNOS (Ser1177 phosphorylation, Thr495 dephosphorylation) remained intact, consistent with integrins mediating only a subset of shear-induced signaling responses. Inhibiting αv prevented shear stress-induced eNOS phosphorylation on Ser633; however, its functional significance remains unclear. Previous work in bovine aortic endothelial cells showed that fibronectin limits shear-induced eNOS activation,5 suggesting that matrix-specific signaling responses may differ between endothelial cell types and cell culture conditions. Although shear stress promotes both α5β1 activation and ligation,12 inhibition of α5β1 signaling (ATN-161, siRNA) did not affect any of the shear stress-induced signaling pathways tested. This stands in stark contrast to the endothelial response to oxLDL, which requires α5β1 but not αvβ3.7 Although the molecular mechanisms remain unknown, the differential requirement for α5β1 and αvβ3 in these two systems likely involves disparate activation of co-stimulatory pathways. Although these data suggest that α5β1 activation is dispensable for shear-induced signaling, we cannot exclude a role for α5β1 in shear stress-associated fibronectin matrix deposition or other shear stress-induced signaling responses beyond those tested herein.12

Although fibronectin-binding integrins are associated with endothelial NF-κB activation and proinflammatory gene expression in cell culture models,7,15,31 our data are the first to definitively link endothelial integrins to their inflammatory activation in vivo. This integrin-driven endothelial activation may contribute to several chronic inflammatory diseases. Polymorphisms in the genes encoding αv and β3 are linked to susceptibility to arthritis and childhood asthma, respectively,32,33 and inhibiting αvβ3 blunts NF-κB activation and inflammation in experimental colitis.34 Signaling through αvβ3 regulates inflammatory angiogenesis in multiple chronic inflammatory disease models.35,36 Although we show that inhibiting αv integrins reduces atherogenic inflammation both in the acute disturbed flow model and the spontaneous diet-induced atherosclerosis model, this effect is not likely to be due to antiangiogenic effects because intraplaque angiogenesis does not occur at this stage of early plaque development.37 Rather, this effect involves the local reduction in proinflammatory signaling, consistent with the reduction in endothelial ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 expression after αv inhibition in vivo. In addition, NF-κB promotes α5β1 and αvβ3 expression,38,39 suggesting that these integrins promote their own expression during inflammatory tissue remodeling.

Early atherogenesis involves coordinated vascular remodeling by multiple cell types. The deposition of transitional matrix proteins from the earliest stages of atherogenesis suggests that altered integrin signaling may affect multiple cellular processes during plaque formation.4 Although αvβ3 staining in human plaques localizes primarily to the endothelium and smooth muscle cells,14 plaque macrophages also express αvβ3, and oxLDL treatment enhances this expression.40 Macrophage αvβ3 mediates efficient efferocytosis,41 which limits necrotic core formation and becomes dysfunctional at later stages in plaque development. In addition, αvβ3 ligation reduces oxLDL uptake by down-regulating macrophage scavenger protein expression (CD36, SRA), suggesting that αvβ3 limits macrophage dysfunction in atherosclerosis.40 However, αvβ3 signaling also promotes macrophage NF-κB activation and proinflammatory cytokine expression (tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-1β) in cell culture models,42 although studies of β3-deficient macrophages are conflicting with both positive and negative effects on homing and proinflammatory gene expression described.43–45 Smooth muscle cell αvβ3 ligation promotes cell proliferation and migration under several experimental conditions and reduces oxLDL-induced apoptosis.46–48 Consistent with these results, β3 KO mice and animals treated with RGD peptide inhibitors show reduced neointimal smooth muscle content after injury-induced vascular remodeling.25,26 Our data show that αvβ3 inhibitors potently inhibit smooth muscle incorporation into early spontaneous atherosclerotic plaques, phenocopying the early reduction in plaque smooth muscle content observed after the deletion of plasma fibronectin.10 In contrast to αvβ3, expression of α5β1 is largely limited to plaque endothelial cells and macrophages, and inhibiting α5β1 limits early atherogenesis but does not prevent smooth muscle incorporation into early atherosclerotic plaques.7

These data illustrate an important role for αvβ3 integrin signaling in shear stress-induced endothelial cell activation and provide the first evidence that integrin signaling regulates endothelial activation in vivo. Specifically, inhibiting endothelial αv integrins limits inflammation during early atherosclerosis, whereas systemic treatment with αvβ3 inhibitors inhibits both inflammation and plaque smooth muscle recruitment. Although this effect of αv inhibition may destabilize the protective fibrous cap,49 it remains unknown whether integrin inhibitors will show similar effects on endothelial and smooth muscle phenotype in advanced atherosclerotic plaques. With multiple αvβ3 antagonists currently undergoing clinical trials for the treatment of psoriasis, arthritis, and cancer,50 the use of these agents in patients at risk of cardiovascular events should be carefully weighed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Carolyn Kelman, Donnie W. Owens, and the Compound Transfer program at Pfizer for S247 compound; Dr. Andrew Mazar (Northwestern University, Evanston, IL) for ATN-161 peptide; Dr. Hanjoong Jo for assistance and training for the partial carotid ligation procedure; Dr. Richard Hynes (MIT, Cambridge, MA) for αvflox/flox mice; and Dr. Luisa Iruela-Arispe (UCLA, Los Angeles, CA) for VE-cadherinCreERT2 transgenic mice.

Footnotes

Supported by the NIH grant R01 HL098435 (A.W.O.), Louisiana Board of Regents Superior Toxicology Fellowship LEQSF (2008–13)-FG-20 (A.Y.), American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship 14PRE18660003 (A.Y.), and American Heart Association Post-Doctoral Fellowship 12POST12030375 (J.C.).

J.C. and J.G. contributed equally to this work.

Disclosures: The αv integrin inhibitor S247 was provided by Pfizer.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.05.013.

Supplemental Data

Endothelial integrin expression. mRNA isolated from HAE cells was analyzed for expression of the integrin family of genes by quantitative real-time PCR, normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and expressed as relative percentage expression. n = 4 to 7. HAE, human aortic endothelial; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

Inhibition of αv but not α5 integrins blunts shear stress-induced NF-κB activation. A: Human aortic endothelial cells on fibronectin were treated with 50 μmol/L ATN-161 or 1 μmol/L S247 and exposed to acute onset of flow for 30 minutes. Activation of eNOS, FAK, AKT, PAK2, and NF-κB was assessed by Western blot analysis with phospho-specific antibodies and normalized to total protein levels. Representative blots are shown. Quantification of shear-induced activation of AKT (B), eNOS Ser1177 (C), eNOS Thr495 (D), and eNOS Ser633 (E) is shown. n = 4 (B–E). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ERK, extracellular regulated kinase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; IB, immunoblot; NT, no treatment; PAK2, p21-activated kinase 2.

Selective knockdown of αv integrins blunts shear stress-induced NF-κB activation. A: Human aortic endothelial cells were transfected with siRNA for α5 or αv integrins, plated on fibronectin, and exposed to acute onset of shear stress for 30 minutes. Integrin expression was determined by Western blot analysis, and shear-induced activation of eNOS, FAK, PAK2, and NF-κB was assessed by Western blot analysis with phospho-specific antibodies and normalized to total protein levels. Representative blots are shown. Quantification of shear-induced activation of α5 and αv expression (B), AKT (C), eNOS Ser1177 (D), eNOS Thr495 (E), and eNOS Ser633 (F). n = 5 (B–F). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ERK, extracellular regulated kinase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; IB, immunoblot; NT, no treatment; PAK2, p21-activated kinase 2.

Analysis of atherosclerotic plaque area in the carotid sinus by Russell-Movat Pentachrome staining. A: Representative images of the carotid sinus from mice treated with saline or S247 are shown with insets of the entire vessel. B: Quantification of plaque cross-sectional area determined at multiple regions along the sinus. C: After tamoxifen treatment, intimal and medial/Adv mRNA was collected from iEC-Control and iEC-αv KO mice and analyzed for αv expression. D: Representative images of the carotid sinus from iEC-Control and iEC-αv KO mice with insets of the entire vessel. E: Quantification of plaque cross-sectional area determined at multiple regions along the sinus. n = 5 mice per group (B); n = 6 to 7 mice per group (C and E). ∗P < 0.05. Original magnification: ×40 (A, main image; D); ×10 (insets). Adv, adventitial; Ctrl, control; iEC, inducible epithelial cell; KO, knockout.

References

- 1.Hahn C., Schwartz M.A. Mechanotransduction in vascular physiology and atherogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:53–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou J., Li Y.S., Chien S. Shear stress-initiated signaling and its regulation of endothelial function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2191–2198. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Funk S.D., Yurdagul A., Jr., Green J.M., Jhaveri K.A., Schwartz M.A., Orr A.W. Matrix-specific protein kinase A signaling regulates p21-activated kinase activation by flow in endothelial cells. Circ Res. 2010;106:1394–1403. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.210286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orr A.W., Sanders J.M., Bevard M., Coleman E., Sarembock I.J., Schwartz M.A. The subendothelial extracellular matrix modulates NF-kappaB activation by flow: a potential role in atherosclerosis. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:191–202. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yurdagul A., Jr., Chen J., Funk S.D., Albert P., Kevil C.G., Orr A.W. Altered nitric oxide production mediates matrix-specific PAK2 and NF-kappaB activation by flow. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:398–408. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-07-0513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feaver R.E., Gelfand B.D., Wang C., Schwartz M.A., Blackman B.R. Atheroprone hemodynamics regulate fibronectin deposition to create positive feedback that sustains endothelial inflammation. Circ Res. 2010;106:1703–1711. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.216283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yurdagul A., Jr., Green J., Albert P., McInnis M.C., Mazar A.P., Orr A.W. alpha5beta1 integrin signaling mediates oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced inflammation and early atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:1362–1373. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orr A.W., Hahn C., Blackman B.R., Schwartz M.A. p21-activated kinase signaling regulates oxidant-dependent NF-kappa B activation by flow. Circ Res. 2008;103:671–679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.182097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiang H.Y., Korshunov V.A., Serour A., Shi F., Sottile J. Fibronectin is an important regulator of flow-induced vascular remodeling. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1074–1079. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohwedder I., Montanez E., Beckmann K., Bengtsson E., Duner P., Nilsson J., Soehnlein O., Fassler R. Plasma fibronectin deficiency impedes atherosclerosis progression and fibrous cap formation. EMBO Mol Med. 2012;4:564–576. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201200237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hynes R.O. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orr A.W., Ginsberg M.H., Shattil S.J., Deckmyn H., Schwartz M.A. Matrix-specific suppression of integrin activation in shear stress signaling. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4686–4697. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-04-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tzima E., Del Pozo M.A., Kiosses W.B., Mohamed S.A., Li S., Chien S., Schwartz M.A. Activation of Rac1 by shear stress in endothelial cells mediates both cytoskeletal reorganization and effects on gene expression. EMBO J. 2002;21:6791–6800. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoshiga M., Alpers C.E., Smith L.L., Giachelli C.M., Schwartz S.M. Alpha-v beta-3 integrin expression in normal and atherosclerotic artery. Circ Res. 1995;77:1129–1135. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.6.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scatena M., Almeida M., Chaisson M.L., Fausto N., Nicosia R.F., Giachelli C.M. NF-kappaB mediates alphavbeta3 integrin-induced endothelial cell survival. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1083–1093. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals; National Research Council . National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2011. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals: Eighth Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lacy-Hulbert A., Smith A.M., Tissire H., Barry M., Crowley D., Bronson R.T., Roes J.T., Savill J.S., Hynes R.O. Ulcerative colitis and autoimmunity induced by loss of myeloid alphav integrins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15823–15828. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707421104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Monvoisin A., Alva J.A., Hofmann J.J., Zovein A.C., Lane T.F., Iruela-Arispe M.L. VE-cadherin-CreERT2 transgenic mouse: a model for inducible recombination in the endothelium. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:3413–3422. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobczak M., Dargatz J., Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M. Isolation and culture of pulmonary endothelial cells from neonatal mice. J Vis Exp. 2010;(46):2316. doi: 10.3791/2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nam D., Ni C.W., Rezvan A., Suo J., Budzyn K., Llanos A., Harrison D., Giddens D., Jo H. Partial carotid ligation is a model of acutely induced disturbed flow, leading to rapid endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:H1535–H1543. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00510.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Short S.M., Talbott G.A., Juliano R.L. Integrin-mediated signaling events in human endothelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:1969–1980. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.8.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shannon K.E., Keene J.L., Settle S.L., Duffin T.D., Nickols M.A., Westlin M., Schroeter S., Ruminski P.G., Griggs D.W. Anti-metastatic properties of RGD-peptidomimetic agents S137 and S247. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2004;21:129–138. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000024764.93092.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schiller H.B., Hermann M.R., Polleux J., Vignaud T., Zanivan S., Friedel C.C., Sun Z., Raducanu A., Gottschalk K.E., Thery M., Mann M., Fassler R. beta1- and alphav-class integrins cooperate to regulate myosin II during rigidity sensing of fibronectin-based microenvironments. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:625–636. doi: 10.1038/ncb2747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orr A.W., Hastings N.E., Blackman B.R., Wamhoff B.R. Complex regulation and function of the inflammatory smooth muscle cell phenotype in atherosclerosis. J Vasc Res. 2010;47:168–180. doi: 10.1159/000250095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuno H., Stassen J.M., Vermylen J., Deckmyn H. Inhibition of integrin function by a cyclic RGD-containing peptide prevents neointima formation. Circulation. 1994;90:2203–2206. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.5.2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Panchatcharam M., Miriyala S., Yang F., Leitges M., Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M., Quilliam L.A., Anaya P., Morris A.J., Smyth S.S. Enhanced proliferation and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells in response to vascular injury under hyperglycemic conditions is controlled by beta3 integrin signaling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:965–974. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maile L.A., Busby W.H., Nichols T.C., Bellinger D.A., Merricks E.P., Rowland M., Veluvolu U., Clemmons D.R. A monoclonal antibody against alphaVbeta3 integrin inhibits development of atherosclerotic lesions in diabetic pigs. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:18ra11. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petzold T., Orr A.W., Hahn C., Jhaveri K.A., Parsons J.T., Schwartz M.A. Focal adhesion kinase modulates activation of NF-kappaB by flow in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2009;297:C814–C822. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00226.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tzima E., Irani-Tehrani M., Kiosses W.B., Dejana E., Schultz D.A., Engelhardt B., Cao G., DeLisser H., Schwartz M.A. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature. 2005;437:426–431. doi: 10.1038/nature03952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tzima E., del Pozo M.A., Shattil S.J., Chien S., Schwartz M.A. Activation of integrins in endothelial cells by fluid shear stress mediates Rho-dependent cytoskeletal alignment. EMBO J. 2001;20:4639–4647. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.17.4639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhullar I.S., Li Y.S., Miao H., Zandi E., Kim M., Shyy J.Y., Chien S. Fluid shear stress activation of IkappaB kinase is integrin-dependent. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:30544–30549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.46.30544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollis-Moffatt J.E., Rowley K.A., Phipps-Green A.J., Merriman M.E., Dalbeth N., Gow P., Harrison A.A., Highton J., Jones P.B., Stamp L.K., Harrison P., Wordsworth B.P., Merriman T.R. The ITGAV rs3738919 variant and susceptibility to rheumatoid arthritis in four Caucasian sample sets. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R152. doi: 10.1186/ar2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiss L.A., Lester L.A., Gern J.E., Wolf R.L., Parry R., Lemanske R.F., Solway J., Ober C. Variation in ITGB3 is associated with asthma and sensitization to mold allergen in four populations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:67–73. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200411-1555OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aziz M.M., Ishihara S., Mishima Y., Oshima N., Moriyama I., Yuki T., Kadowaki Y., Rumi M.A., Amano Y., Kinoshita Y. MFG-E8 attenuates intestinal inflammation in murine experimental colitis by modulating osteopontin-dependent alphavbeta3 integrin signaling. J Immunol. 2009;182:7222–7232. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Creamer J.D., Barker J.N. Vascular proliferation and angiogenic factors in psoriasis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:6–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1995.tb01274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Storgard C.M., Stupack D.G., Jonczyk A., Goodman S.L., Fox R.I., Cheresh D.A. Decreased angiogenesis and arthritic disease in rabbits treated with an alphavbeta3 antagonist. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:47–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI3756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moulton K.S., Heller E., Konerding M.A., Flynn E., Palinski W., Folkman J. Angiogenesis inhibitors endostatin or TNP-470 reduce intimal neovascularization and plaque growth in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 1999;99:1726–1732. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.13.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cho S.O., Kim K.H., Yoon J.H., Kim H. Signaling for integrin alpha5/beta1 expression in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric epithelial AGS cells. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1090:298–304. doi: 10.1196/annals.1378.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li S., Wang X., Qiu J., Si Q., Wang H., Guo H., Sun R., Wu Q. Angiotensin II stimulates endothelial integrin beta3 expression via nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Exp Aging Res. 2006;32:47–60. doi: 10.1080/01902140500325049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Antonov A.S., Kolodgie F.D., Munn D.H., Gerrity R.G. Regulation of macrophage foam cell formation by alphaVbeta3 integrin: potential role in human atherosclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:247–258. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63293-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hanayama R., Tanaka M., Miwa K., Shinohara A., Iwamatsu A., Nagata S. Identification of a factor that links apoptotic cells to phagocytes. Nature. 2002;417:182–187. doi: 10.1038/417182a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antonov A.S., Antonova G.N., Munn D.H., Mivechi N., Lucas R., Catravas J.D., Verin A.D. alphaVbeta3 integrin regulates macrophage inflammatory responses via PI3 kinase/Akt-dependent NF-kappaB activation. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:469–476. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morgan E.A., Schneider J.G., Baroni T.E., Uluckan O., Heller E., Hurchla M.A., Deng H., Floyd D., Berdy A., Prior J.L., Piwnica-Worms D., Teitelbaum S.L., Ross F.P., Weilbaecher K.N. Dissection of platelet and myeloid cell defects by conditional targeting of the beta3-integrin subunit. FASEB J. 2010;24:1117–1127. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-138420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schneider J.G., Zhu Y., Coleman T., Semenkovich C.F. Macrophage beta3 integrin suppresses hyperlipidemia-induced inflammation by modulating TNFalpha expression. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:2699–2706. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang L., Dong Y., Cheng J., Du J. Role of integrin-beta3 protein in macrophage polarization and regeneration of injured muscle. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:6177–6186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.292649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brown S.L., Lundgren C.H., Nordt T., Fujii S. Stimulation of migration of human aortic smooth muscle cells by vitronectin: implications for atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:1815–1820. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.12.1815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sodhi C.P., Phadke S.A., Batlle D., Sahai A. Hypoxia stimulates osteopontin expression and proliferation of cultured vascular smooth muscle cells: potentiation by high glucose. Diabetes. 2001;50:1482–1490. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.6.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheng J., Zhang J., Merched A., Zhang L., Zhang P., Truong L., Boriek A.M., Du J. Mechanical stretch inhibits oxidized low density lipoprotein-induced apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells by up-regulating integrin alphavbeta3 and stablization of PINCH-1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:34268–34275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703115200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Libby P. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of the thrombotic complications of atherosclerosis. J Lipid Res. 2009;(50 Suppl):S352–S357. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800099-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kapp T.G., Rechenmacher F., Sobahi T.R., Kessler H. Integrin modulators: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2013;23:1273–1295. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2013.818133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Endothelial integrin expression. mRNA isolated from HAE cells was analyzed for expression of the integrin family of genes by quantitative real-time PCR, normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, and expressed as relative percentage expression. n = 4 to 7. HAE, human aortic endothelial; ICAM-1, intercellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1.

Inhibition of αv but not α5 integrins blunts shear stress-induced NF-κB activation. A: Human aortic endothelial cells on fibronectin were treated with 50 μmol/L ATN-161 or 1 μmol/L S247 and exposed to acute onset of flow for 30 minutes. Activation of eNOS, FAK, AKT, PAK2, and NF-κB was assessed by Western blot analysis with phospho-specific antibodies and normalized to total protein levels. Representative blots are shown. Quantification of shear-induced activation of AKT (B), eNOS Ser1177 (C), eNOS Thr495 (D), and eNOS Ser633 (E) is shown. n = 4 (B–E). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ERK, extracellular regulated kinase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; IB, immunoblot; NT, no treatment; PAK2, p21-activated kinase 2.

Selective knockdown of αv integrins blunts shear stress-induced NF-κB activation. A: Human aortic endothelial cells were transfected with siRNA for α5 or αv integrins, plated on fibronectin, and exposed to acute onset of shear stress for 30 minutes. Integrin expression was determined by Western blot analysis, and shear-induced activation of eNOS, FAK, PAK2, and NF-κB was assessed by Western blot analysis with phospho-specific antibodies and normalized to total protein levels. Representative blots are shown. Quantification of shear-induced activation of α5 and αv expression (B), AKT (C), eNOS Ser1177 (D), eNOS Thr495 (E), and eNOS Ser633 (F). n = 5 (B–F). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; ERK, extracellular regulated kinase; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; IB, immunoblot; NT, no treatment; PAK2, p21-activated kinase 2.

Analysis of atherosclerotic plaque area in the carotid sinus by Russell-Movat Pentachrome staining. A: Representative images of the carotid sinus from mice treated with saline or S247 are shown with insets of the entire vessel. B: Quantification of plaque cross-sectional area determined at multiple regions along the sinus. C: After tamoxifen treatment, intimal and medial/Adv mRNA was collected from iEC-Control and iEC-αv KO mice and analyzed for αv expression. D: Representative images of the carotid sinus from iEC-Control and iEC-αv KO mice with insets of the entire vessel. E: Quantification of plaque cross-sectional area determined at multiple regions along the sinus. n = 5 mice per group (B); n = 6 to 7 mice per group (C and E). ∗P < 0.05. Original magnification: ×40 (A, main image; D); ×10 (insets). Adv, adventitial; Ctrl, control; iEC, inducible epithelial cell; KO, knockout.