Abstract

The liver is a major organ for lipid synthesis and metabolism. Deficiency of lysosomal acid lipase (LAL; official name Lipa, encoded by Lipa) in mice (lal−/−) results in enlarged liver size due to neutral lipid storage in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells. To test the functional role of LAL in hepatocyte, hepatocyte-specific expression of human LAL (hLAL) in lal−/− mice was established by cross-breeding of liver-activated promoter (LAP)–driven tTA transgene and (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL transgene with lal−/− knockout (KO) (LAP-Tg/KO) triple mice. Hepatocyte-specific expression of hLAL in LAP-Tg/KO triple mice reduced the liver size to the normal level by decreasing lipid storage in both hepatocytes and Kupffer cells. hLAL expression reduced tumor-promoting myeloid-derived suppressive cells in the liver of lal−/− mice. As a result, B16 melanoma metastasis to the liver was almost completely blocked. Expression and secretion of multiple tumor-promoting cytokines or chemokines in the liver were also significantly reduced. Because hLAL is a secretory protein, lal−/− phenotypes in other compartments (eg, blood, spleen, and lung) also ameliorated, including systemic reduction of myeloid-derived suppressive cells, an increase in CD4+ and CD8+ T and B lymphocytes, and reduced B16 melanoma metastasis in the lung. These results support a concept that LAL in hepatocytes is a critical metabolic enzyme in controlling neutral lipid metabolism, liver homeostasis, immune response, and tumor metastasis.

Lysosomal acid lipase (LAL) (official name LIPA, encoded by LIPA) hydrolyzes cholesteryl esters (CEs) and triglycerides (TGs) in lysosomes. Mutation in LIPA results in Wolman disease (WD) as early infantile onset and CE storage disease (CESD) as late onset.1–3 Infants with WD have massive accumulations of CEs and TGs in the lysosomes of hepatocytes and Kupffer cells, as well as in macrophages throughout the viscera, which lead to liver failure, severe hepatosplenomegaly, steatorrhea, pulmonary fibrosis, and adrenal calcification.2 Patients with CESD have the major symptom of hepatomegaly with increased hepatic levels of CEs, which reveals microvesicular steatosis leading to fibrosis and cirrhosis in the liver and increases atherosclerosis and premature demise.4–6

An LAL knockout (KO) mouse model (lal−/−) resembles human CESD, and its biochemical and histopathologic phenotypes mimic human WD.7,8 The lal−/− mice are normal appearing at birth but develop liver enlargement by 1.5 months and have a grossly enlarged abdomen with hepatosplenomegaly and lymph node enlargement.7,8 One interesting character of lal−/− mice is a systemic expansion (including the liver) of CD11b+Ly6G+ cells, which are similar to myeloid-derived suppressive cells (MDSCs) in tumorigenesis.9–11 MDSCs influence the tissue microenvironment and contribute to local pathogenesis.7–13 In humans, increased CD14+CD16+ and CD14+CD33+ cells (human subsets of MDSCs) have been linked to heterozygote carriers of LAL mutations.14 Hepatocellular carcinoma has been linked to chronic inflammation with elevated MDSC counts.15–17

To better understand the physiologic role of LAL in hepatocytes and the link to clinical application, hepatocyte-specific expression of human LAL (hLAL) in lal−/− mice was achieved by crossbreeding a liver-activated promoter (LAP)–driven tTA transgene (LAP-tTA) and a (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL transgene (Tet off system) into lal−/− mice (LAP-Tg/KO mice). Histologic and tissue lipid analyses revealed a correction of lipid storage in the liver, spleen, and small intestine in doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO mice (hLAL induction turns on) compared with doxycycline-treated LAP-Tg/KO mice (hLAL induction turns off). Flow cytometry analyses revealed reduced tumor-promoting MDSCs in the liver of LAP-Tg/KO mice. Furthermore, hLAL overexpression in hepatocytes greatly reduced metastasis of B16 melanoma into the liver. These pathogenic phenotypes were associated with a decrease of inflammatory cytokine and chemokine levels. Together, these results indicate that hepatic LAL plays an important role in lipid metabolism, cytokine production, MDSCs influx into organs, and tumor metastasis in the liver.

Materials and Methods

Animal Care and Cell Lines

LAP-tTA/(TetO)7-CMV-hLAL; lal−/− (LAP-Tg/KO) triple mice of the FVB/N background was established by cross-breeding of LAP-tTA transgenic mice (Jackson's Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) with a previously generated (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL transgenic mice18 into lal−/− mice. This triple transgenic mouse model is hepatocyte-specific Tet-off expression of wild-type hLAL in lal−/− mice under the control of the LAP. All scientific protocols that involved the use of animals have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Indiana University School of Medicine and followed guidelines established by the Panel on Euthanasia of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Animals were housed in a secured animal facility at Indiana University School of Medicine. The murine B16 melanoma cell line (ATCC, Manassas, VA) was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, NY).

Characterization of Tissue Expression of the hLAL Transgene by RT-PCR

Total RNAs from the liver, lung, spleen, and bone marrow cells of wild-type, lal−/−, and LAP-Tg/KO triple mice or hepatocytes and Ly6G+ cells isolated from the liver were purified using a total RNA purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Ly6G+ cells from the liver were isolated by incubation with biotin-labeled anti-Ly6G+ antibody after liver perfusion, followed by incubation with anti-biotin immune-magnetic microbeads and magnetic-activated cell sorting technique according to the manufacturer's instruction (Miltenyi Biotech, Auburn, CA). cDNA was generated by a reverse transcription kit (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) from isolated total RNA. PCR amplification was used two different sets of primers for verification of hLAL expression. The first pair of primers cover different exons (exons 8 and 9) unique to the hLAL gene (forward primer, 5′-AGCCAGGCTGTTAAATTCCAAA-3′; reverse primer, 5′-GAATGCTCTCATGGAACACCAA-3′). The second pair of primers cover an exon (exon 9) that is unique to the hLAL gene and the Flag epitope coding sequence that is at the 3′ end of hLAL cDNA in the (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL vector, which is unique to the hLAL-Flag combination (forward primer, 5′-TGCAGTCTGGAGCGGGG-3′; reverse primer, 5′-TGTCATCGTCGTCCTTGTAGTCC-3′). The housekeeping gene β-actin (forward primer, 5′-ACCGTGAAAAGATGACCCAGAT-3′; reverse primer, 5′-GCCTGGATGGCTACGTACATG-3′) was used as an internal control. PCR were performed on Mastercycler (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany).

Western Blot Analysis of hLAL Protein Expression

Protein samples from the liver, lung, spleen, and bone marrow cells of wild-type, lal−/−, and LAP-Tg/KO mice were prepared in the Cell Lytic M mammalian cell lysis/extraction buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Protein samples were fractionated on a Novex 4% to 20% Tris-Glycine Mini Gel (Invitrogen). After protein transferred to the polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), the membrane was blotted with 5% nonfat dry milk in 1× phosphate-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween 80 and incubated with rabbit anti-LAL and anti-actin primary antibodies (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). After incubation with the secondary antibody that conjugated with horseradish peroxidase, proteins were visualized with chemiluminescent substrate under the ChemiDocTM MP Image System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Tissue Lipid Extraction and Determination of CE and TG Concentrations

Total tissue lipids were extracted from the liver and small intestine by the Folch method.19 Concentrations of CEs and TGs were determined as previously described.8,20

Oil Red-O Staining

Frozen tissue sections were prepared from the liver and intestine after a standard cryostat procedure. Tissue section slides were stained with Oil Red-O solution (0.5% in propylene glycol) in a 60°C oven for 10 minutes and placed in 85% propylene glycol for 1 minute; slides were counterstained in hematoxylin.

IHC Staining

Tissues from the liver, intestine, and lung were collected after mice were anesthetized. All tissues were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and dehydrated by a series of increasing ethanol concentrations, followed by paraffin embedding. Sections were stained with anti-Ki67 antibody, anti-LAL antibody, and anti-F4/80 antibody by the histologic core.

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Single-cell suspensions from the bone marrow, spleen, blood, liver, and lung were prepared and analyzed as previously described.9,10,21 Approximately 1 × 106 cells from various organs were blocked with FcR blocking antibodies in flow cytometry buffer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) followed by incubation with isotype control or surface specific primary antibodies. Anti-CD11b (M1/70) PE-Cyanine7, anti-Ly6G (RB6-8c5) allophycocyanin-eFluor 780, anti-CD4 fluorescein isothiocyanate, anti-CD8 phosphatidylethanolamine, and anti-B220 allophycocyanin were purchased from e-Biosciences (San Diego, CA). Cells were analyzed on a LSRII machine (BD Biosciences). Data were analyzed using the BD FACStation software (CellQuest Pro version 2.2.1, BD Biosciences). The total gated number of positive cells (approximately 30,000 events) was calculated as the percentage of total gated viable cells. Quadrants were assigned using isotype control monoclonal antibody.

Mouse Metastasis Models

For experimental metastasis, 5 × 105 B16 melanoma cells in 200 μL of phosphate-buffered saline were injected into the mice via tail vein. Two weeks after the injection, the mice were sacrificed, and the livers and lungs were harvested for examination of metastasis.

qPCR

Total RNAs were purified from livers or isolated hepatocytes using RNeasy Mini Kits according to the manufacturer's instruction (Qiagen). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qPCR) was performed as described previously.22 Relative gene expression levels were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCT method. Primers of mouse IL-6, mouse granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), mouse macrophage colony-stimulating factor, mouse tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, mouse IL-2, mouse IL-4, mouse IL-17, mouse interferon (IFN)-γ, mouse monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), mouse chemokine ligand (CCL)-3, mouse CCL4, mouse CCL5, mouse CXCL10, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase for qPCR were described previously.23,24

Cytokine Measurement by ELISA

The expression levels of IL-6, GM-CSF, MCP-1 (BD Biosciences), and CCL5 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) in the plasma and hepatocyte culture medium were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Mouse Hepatocyte Isolation

Hepatocytes were isolated from the mouse using two-step perfusion and digestion technique described previously.25,26 Briefly, the hepatic portal perfusion of the mouse liver with 37°C prewarmed solution A (0.5 mmol/L EGTA and 5 mmol/L HEPES in Hanks) was followed by digestion with 37°C prewarmed solution B (3.75 mmol/L CaCl2 and 0.05 mg/mL of collagenase H in L15) perfusion. The digested liver tissues were gently dispersed with tweezers, and hepatocytes were spun down and washed with 1× HEPES buffer. The cell pellets were resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline for flow cytometry. For tissue culture, isolated hepatocytes were resuspended in William's Medium E with 10% fetal bovine serum and cultured in 37°C. After 2 hours, cells were replaced with new medium and prepared for cytokine and chemokine analyses of mRNA and protein expression.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as means ± SD. Differences between the two treatment groups were compared with the t-test. When more than two groups were compared, one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Newman-Keul's multiple comparison test was used. Results were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05. All analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism software version 5.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Hepatocyte-Specific Expression of hLAL in lal−/− Mice

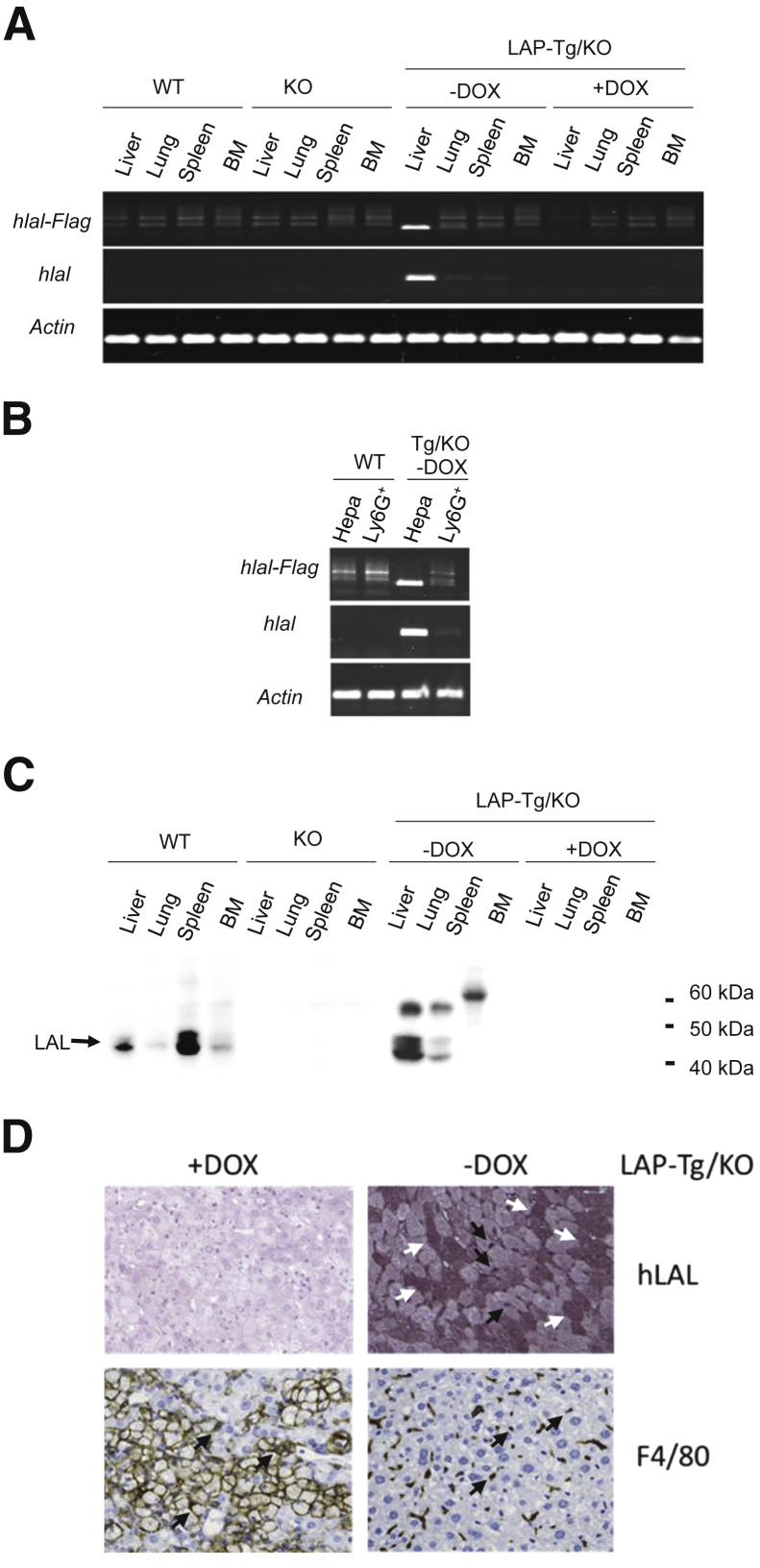

Specific expression of hLAL mRNA in the liver of doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice was confirmed by RT-PCR. Two sets of hLAL primers covering different ranges of hLAL cDNA were used to distinguish hLAL expression from endogenous murine LAL expression. One pair of primers covered exons 8 to 9 of hLAL (Figure 1, A and B), whereas another pair of primers covered exon 9 of hLAL and the Flag epitope coding sequence at the 3′ end of hLAL cDNA in the (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL vector, which is unique to the hLAL-Flag combination (Figure 1, A and B). As predicted, no hLAL mRNA expression was detected in the liver, lung, spleen, and bone marrow cells of wild-type, lal−/−, and doxycycline-treated (turned off) LAP-Tg/KO triple mice. When doxycycline was removed from this Tet-off system, hLAL mRNA expression was induced primarily in the liver of LAP-Tg/KO triple mice (Figure 1A). To further confirm hLAL mRNA expression in hepatocytes of the liver, hepatocyte and Ly6G+ myeloid cells were isolated from the liver of wild-type and doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO mice. Indeed, hLAL mRNA expression was detected in hepatocytes but not in Ly6G+ cells of LAP-Tg/KO triple mice. No detection was observed in hepatocyte and Ly6G+ cells of wild-type mice (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Human LAL (hLAL) expression in wild-type (WT), lal−/− (KO), and liver-activated promoter (LAP)–driven tTA transgene and (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL transgene with lal−/− (LAP-Tg/KO) triple mice. A: RT-PCR for hLAL mRNA expression in the liver, lung, spleen, and bone marrow (BM) of WT, KO, and LAP-Tg/KO triple mice treated with or without doxycycline (DOX). The housekeeping gene β-actin was used as an internal control. B: RT-PCR for hLAL mRNA expression in isolated primary hepatocytes and Ly6G+ cells from WT and LAP-Tg/KO triple mouse liver without DOX. The housekeeping gene β-actin was used as an internal control. C: Western blot analysis of LAL protein in the liver, lung, spleen, and bone marrow of WT, lal−/−(KO), and LAP-Tg/KO triple mice, treated or untreated with DOX. D: Immunohistochemical staining of hLAL and F4/80 in the livers of DOX-treated (+DOX) or DOX-untreated (–DOX) LAP-Tg/KO triple mice. White arrows indicate representative hepatocytes that express hLAL. Black arrows indicate the F4/80+ Kupffer cells that are also positive for hLAL. Without hLAL expression, there is accumulation of enlarged F4/80-positive storage cells in DOX-treated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice. Original magnification: ×200. Hepa, hepatocyte, Ly6G+, Ly6G+ cells from the liver (B).

Next, LAL protein expression was also evaluated. Because hLAL and murine LAL share 75% identity and 95% similarity at the peptide sequence level, our anti-LAL antibody recognizes both of them. In wild-type mice, expression of the LAL protein was detected in the liver, lung, spleen and bone marrow but was undetectable in KO mice (Figure 1C). In LAP-Tg/KO triple mice, expression of the hLAL protein was detected strongly in the liver and weakly in the lung and spleen of doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice but not in doxycycline-treated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice (Figure 1C). To further clarify the cellular specificity of hLAL protein in the liver, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of the liver sections with anti-LAL antibody and anti-F4/80 antibody were performed. The results revealed that approximately 50% of hepatocytes were positive for LAL antibody staining, and F4/80+ Kupffer cells were also positive for LAL staining (Figure 1D) in doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO mice. Because LAL is a secreted protein, the lack of hLAL mRNA expression for the detection of LAL protein in the lung and spleen of doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice is likely due to the uptake of LAL from the circulation system that is secreted from the liver. However, the possibility of uptake of LAL from circulation that is secreted from the liver needs to be further confirmed. The multiple forms of LAL protein were due to differential glycosylation as previously reported.27,28

Hepatocyte-Specific Expression of hLAL in lal−/− Mice Reduces Lipid Storage in Multiple Organs

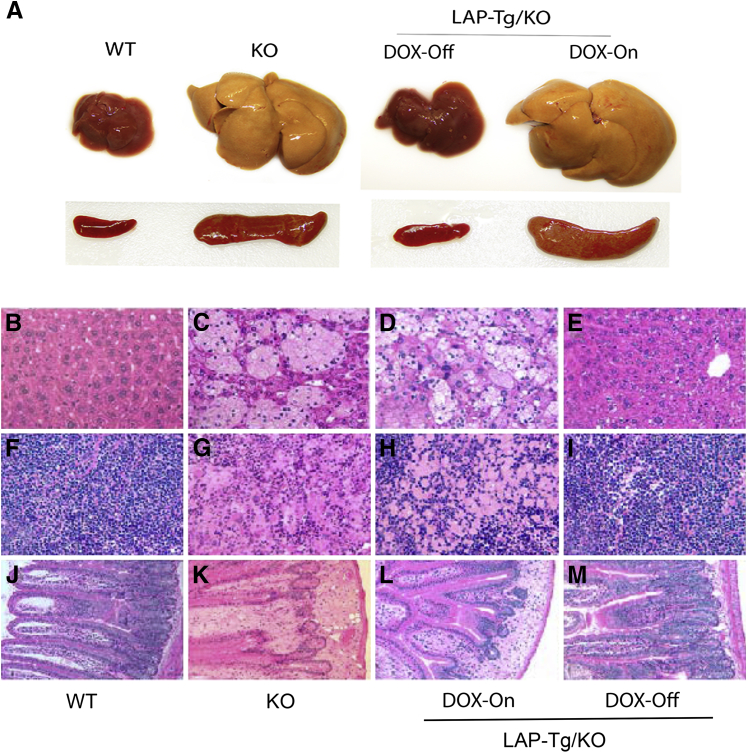

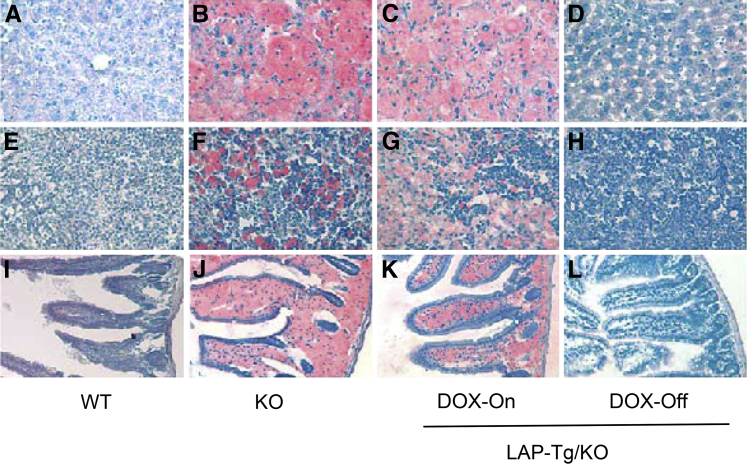

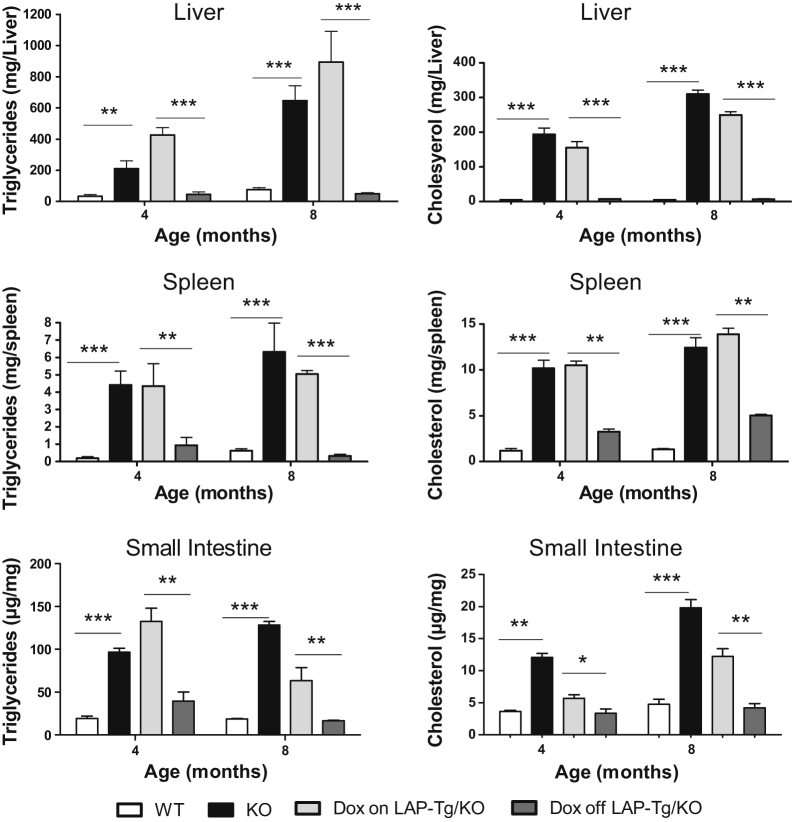

Hepatomegaly is the major symptom in patients with WD and CESD. Characterization of lal−/− mice revealed neutral lipid storage in both hepatocytes and Kupffer cells in the liver.7,8 In the tet-off LAP-Tg/KO system, both gross view and the histologic phenotypes of the liver, spleen, and small intestine in doxycycline-treated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice (for 7 months) were essentially similar to those in lal−/− mice (Figure 2, A, C, D, G, H, K, and L). Doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice, in which hLAL expression was induced, lacked lipid storage not only in hepatocytes but also in Kupffer cells (Figure 2E) similar to the wild-type liver (Figure 2B). The same observations were found in the spleen and small intestine (Figure 2, I and M), resembling those of wild-type mice (Figure 2, F and J). Neutral lipid staining by Oil Red-O revealed that doxycycline-treated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice have the similar level of neutral lipid storage in the liver, spleen, and small intestine compared with those of lal−/− mice (Figure 3, B, C, F, G, J, and K). Doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice had no lipid storage in the liver, spleen, or small intestine similar to those of wild-type mice (Figure 3, A, D, E, H, I, and L). Quantitative analyses of cholesterol and triglyceride tissue lipids in the liver, spleen, and small intestine further confirmed that lipid storage in lal−/− mice was completely cleaned up by hepatocyte expression of hLAL (Figure 4).

Figure 2.

Hepatic expression of hLAL in liver-activated promoter (LAP)–driven tTA transgene and (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL transgene with lal−/− (LAP-Tg/KO) mice corrects abnormality in the liver, spleen, and small intestine. A: Gross view of the liver and spleen of lal+/+ [wild-type (WT)], lal−/− (KO), and doxycycline-untreated (DOX-Off) and doxycycline-treated (DOX-On) LAP-Tg/KO mice. B–M: Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the liver, spleen, and small intestine paraffin sections from WT (B, F, and J), lal−/− (KO) (C, G, and K), DOX-ON (D, H, and L), and DOX-OFF (E, I, and M) LAP-Tg/KO mice. Original magnification: ×200 (B–M).

Figure 3.

Hepatic expression of human lysosomal acid lipase (hLAL) in liver-activated promoter (LAP)–driven tTA transgene and (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL transgene with lal−/− (LAP-Tg/KO) mice corrects neutral lipid storage in the liver, spleen, and small intestine. Oil Red-O staining of liver, spleen, and small intestine frozen sections from wild-type (WT) (A, E, and I), lal−/− (KO) (B, F, and J), doxycycline-treated (DOX-On) (C, G, and K), and doxycycline-untreated (DOX-Off) (D, H, and L) LAP-Tg/KO mice. Original magnification: ×200 (A–L).

Figure 4.

Quantitative analyses of cholesterol and triglycerides in the liver, spleen, and small intestine of human lysosomal acid lipase (hLAL) in liver-activated promoter (LAP)–driven tTA transgene and (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL transgene with lal−/− (LAP-Tg/KO) mice. Concentrations of cholesterol and triglycerides in the liver, spleen, and small intestine of hLAL in LAP-Tg/KO mice were determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data are expressed as means ± SEM from five mice in each group. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001. WT, wild type.

Hepatocyte-Specific Expression of hLAL in lal−/− Triple Mice Reduces B16 Melanoma Cell Metastasis

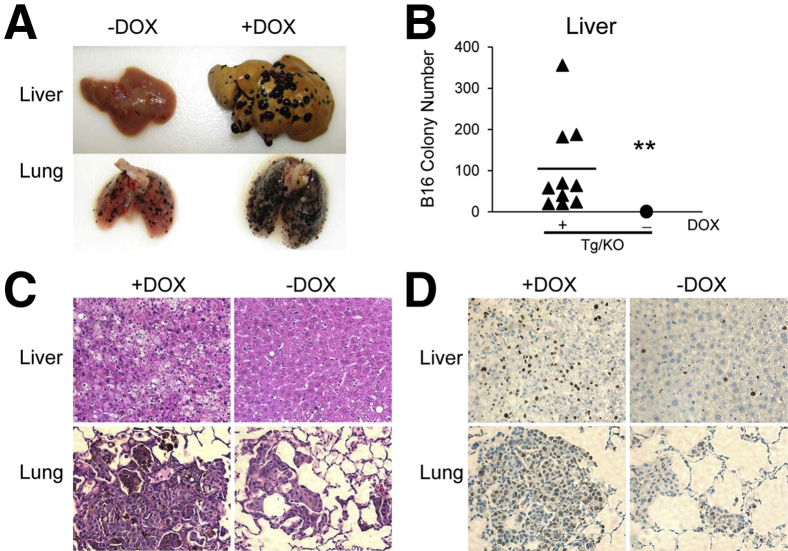

We recently reported that LAL deficiency facilitates inflammation-induced tumor progression and metastasis in the liver and lung.24 To evaluate the effects of hLAL in hepatocytes on tumor metastasis, B16 melanoma cells were injected into the tail veins of LAP-Tg/KO triple mice to assess the metastatic potential. Two weeks after injection, more B16 melanoma colonies were observed in the livers and lungs of doxycycline-treated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice compared with those in untreated mice with statistical significance (Figure 5, A and B). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and IHC staining of liver and lung sections revealed more neoplastic melanoma cells and Ki-67 positive proliferative cells in doxycycline-treated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice than those from untreated mice (Figure 5, C and D). Taken together, these observations suggest that hepatocyte-specific expression of hLAL in lal−/− mice reduced B16 melanoma cell metastasis.

Figure 5.

Hepatic expression of human lysosomal acid lipase (hLAL) in liver-activated promoter (LAP)–driven tTA transgene and (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL transgene with lal−/− (LAP-Tg/KO) mice reduces B16 melanoma metastasis. A: B16 melanoma cells (5 × 105) were intravenously injected into doxycycline-treated (+Dox) or doxycycline-untreated (–DOX) LAP-Tg/KO triple mice for 2 weeks. Metastasized B16 melanoma colonies in the liver and lung are shown. B: Quantitative analysis of B16 melanoma colonies in the livers of doxycycline-treated or doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice. C: Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining of liver and lung sections. D: Representative immunohistochemical staining of metastasized livers and lungs using anti-Ki67 antibody. n = 10 to 16 (A and B). ∗∗P < 0.01. Original magnification: ×200 (C and D).

Hepatocyte-Specific Expression of hLAL in lal−/− Triple Mice Decreases Abnormal Expansion of CD11b+ Ly6G+ Cells

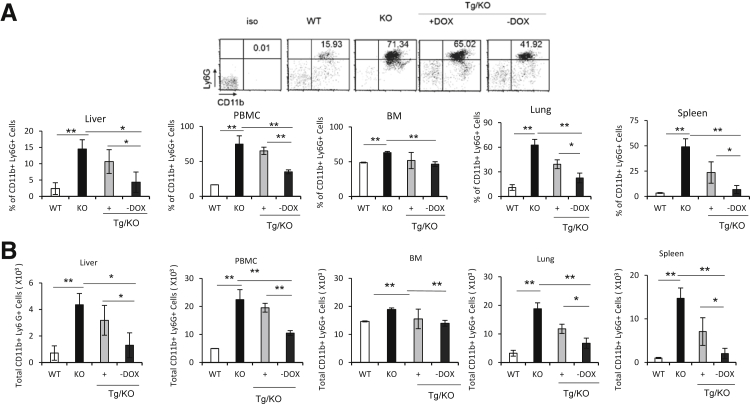

Previous studies have found that loss of LAL causes significant expansion of CD11b+Ly6G+ immature myeloid cells in multiple organs.10 When tested in the liver, this cell population was also markedly increased in lal−/− mice (Figure 6). To test whether hLAL expression in hepatocyte reversed this phenotype, the LAP-Tg/KO triple mice were treated with or without doxycycline for 6 to 7 months. Age-matched wild-type and lal−/− mice were used as controls. Cells from the bone marrow, blood, spleen, lung, and liver of four groups were isolated and stained with anti-CD11b and anti-Ly6G antibodies for flow cytometry analysis. In the liver, the percentage and total number of CD11b+Ly6G+ cells in doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice were decreased to the levels of wild-type mice (Figure 6, A and B). With doxycycline treatment, hLAL expression was shut down in LAP-Tg/KO hepatocytes, which led to CD11b+Ly6G+ cell expansion to the level observed in lal−/− mice. Because hLAL is a secretory enzyme, reduction of CD11b+Ly6G+ cell expansion was also observed in the blood, spleen, and lung but not in the bone marrow of doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice (Figure 6, A and B).

Figure 6.

Hepatic expression of human lysosomal acid lipase (hLAL) in liver-activated promoter (LAP)–driven tTA transgene and (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL transgene with lal−/− (LAP-Tg/KO) mice reduces CD11b+Ly6G+ cell expansion. The percentages (A) and total cell numbers (B) of CD11b+ Ly6G+ cells in the wild-type (WT), lal−/− (KO), doxycycline-treated (+DOX), or doxycycline-untreated (–DOX) LAP-Tg/KO liver, bone marrow (BM), blood [peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)], lung, and spleen (3 × 104). A representative dot plot of CD11b+Ly6G+ cells in the blood is shown. Data are expressed as means ± SD from four mice in each group. n = 4. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

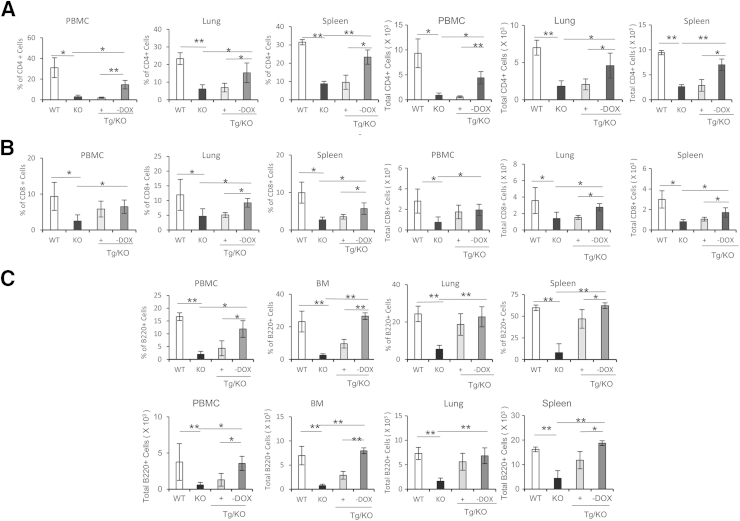

Hepatocyte-Specific Expression of hLAL in lal−/− Triple Mice Increases CD4+, CD8+, and B220+ Cells

CD11b+Ly6G+ cells are partially responsible for the decrease of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in lal−/− mice.9 It is intriguing to determine whether a decrease of CD11b+Ly6G+ cells in doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice leads to an increase of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. The CD4+ T-cell level was low in doxycycline-treated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice, which is similar to that of lal−/− mice. However, hLAL hepatocyte-specific expression increased CD4+ T cells in LAP-Tg/KO triple mice in the blood, lung, and spleen (Figure 7A). CD8+ T cells had a similar outcome in the lung and spleen but not in the blood (Figure 7B). The result for the B220+ B-cell population was similar to those observed in T-cell populations (Figure 7C). Because of the overlap and interference of strong autofluorescence from liver cells of lal−/− mice, the T-cell and B-cell levels in the liver were unable to be determined by flow cytometry.

Figure 7.

Hepatic expression of human lysosomal acid lipase (hLAL) in liver-activated promoter (LAP)–driven tTA transgene and (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL transgene with lal−/− (LAP-Tg/KO) mice increases CD4+, CD8+, and B220+ cells. The percentages and total cell numbers of CD4+ T cells (A), CD8+ T cells (B), and B220+ B cells (C) in the wild-type (WT), lal−/− (KO), doxycycline-treated (+DOX), or doxycycline-untreated (–DOX) LAP-Tg/KO bone marrow (BM), blood [peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)], lung, and spleen. Representative dot plots or histograms of CD4+, CD8+, and B220+ cells in the blood (PBMCs) are shown, respectively. Data are expressed as means ± SD from four mice in each group. n = 4. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01.

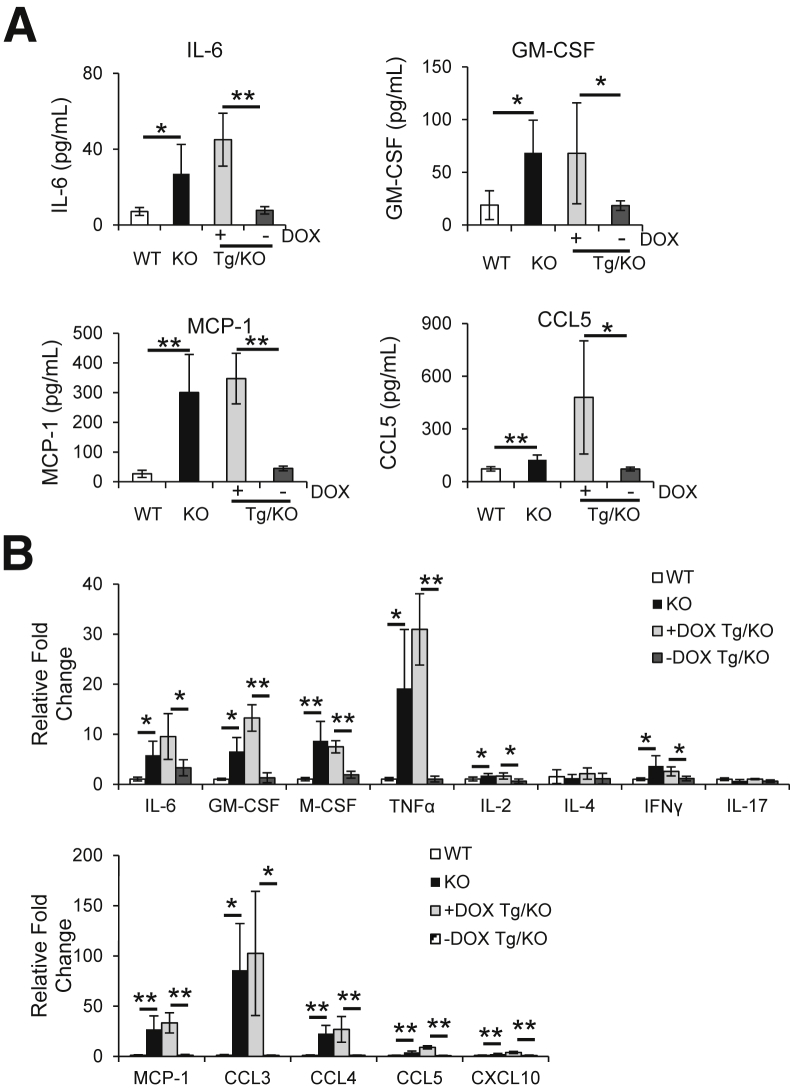

Hepatocyte-Specific Expression of hLAL in lal−/− Triple Mice Reduces Synthesis and Secretion of Tumor-Promoting Cytokines and Chemokines

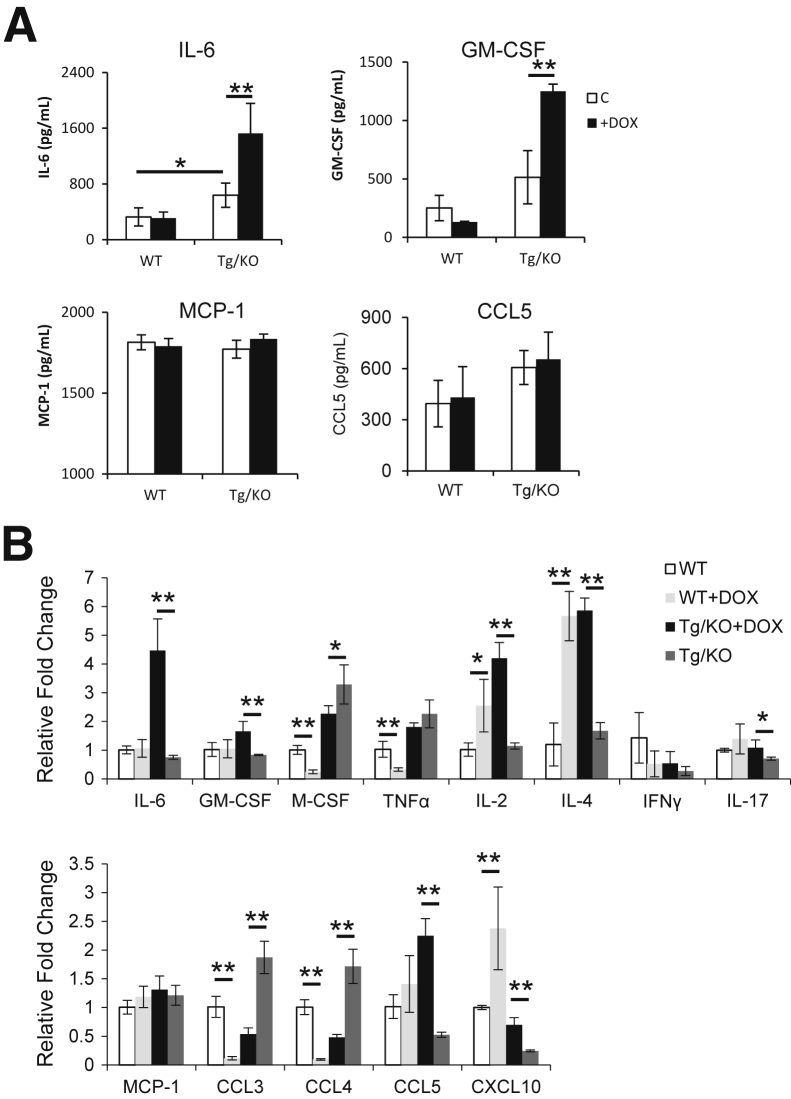

In addition to the changes of immune cells, cytokines and chemokines that are known to promote inflammation and tumorigenesis were measured in the blood plasma by ELISA. The plasma concentrations of IL-6, GM-CSF, MCP-1, and CCL5 were decreased in untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice compared with those in doxycycline-treated mice (Figure 8A). These cytokines and chemokines are important for MDSC accumulation and tumorigenesis.29,30 mRNA syntheses of these cytokines and chemokines in the liver were further investigated. mRNA levels of IL-6, GM-CSF, M-CSF, and TNF-α were significantly down-regulated in the liver of doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice, accompanied by reduced mRNA levels of T-cell–secreted lymphokines IL-2 and IFN-γ, and unchanged IL-4 and IL-17 levels (Figure 8B). In addition, mRNA syntheses of chemokines that have been reported to be involved in liver injury31 were markedly down-regulated in the livers of doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice, including MCP-1, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, and CXCL10. Therefore, reduced synthesis and secretion of cytokines and chemokines were, at least in part, responsible for the decreased metastasis in the lal−/− mice with hepatocyte-specific hLAL expression. These cytokines may or may not be synthesized and secreted by hepatocytes, which were tested below.

Figure 8.

Hepatic expression of human lysosomal acid lipase (hLAL) in liver-activated promoter (LAP)–driven tTA transgene and (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL transgene with lal−/− (LAP-Tg/KO) mice reduces synthesis and secretion of cytokines and chemokines. A: The concentrations of IL-6, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), and chemokine ligand (CCL)-5 in the plasma of doxycycline-treated (+DOX) or doxycycline-untreated (–DOX) lal+/+ [wild type (WT)], lal−/− (KO), and LAP-Tg/KO mice were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. B: Quantitative real-time PCR analyses of mRNA expression levels of cytokines and chemokines in the liver of lal+/+ (WT), lal−/− (KO), and +DOX or –DOX LAP-Tg/KO mice. The relative gene expression was normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA, and analysis was performed by the 2−ΔΔCT method. Data are expressed as means ± SD. n = 5 to 6 (A); n = 4 (B). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. IFNγ, interferon-γ; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-α.

In Vitro Doxycycline Treatment of Hepatocytes from Untreated LAP-Tg/KO Triple Mice Induces Synthesis and Secretion of Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines

To determine which of these tumor-promoting cytokines are secreted by hepatocytes of LAP-Tg/KO triple mice, hepatocytes were isolated from lal+/+ and doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice, followed by treatment with doxycycline in vitro for 5 days. The culture medium was harvested and cytokine levels were determined by ELISA. The concentrations of GM-CSF and IL-6 in the culture medium of doxycycline-treated LAP-Tg/KO hepatocytes were significantly increased, whereas MCP-1 and CCL5 did not change, compared with those from untreated hepatocytes (Figure 9A). This observation suggests that doxycycline-inducible hLAL off-expression in hepatocytes partially contributes to the increased concentrations of GM-CSF and IL-6 but not those of MCP-1 and CCL5. mRNA syntheses of these cytokines/chemokines in the hepatocytes were further investigated. mRNA levels of IL-6, GM-CSF, IL-2, IL-4, IL-17, CCL5, and CXCL10 were significantly up-regulated in the doxycycline-treated LAP-Tg/KO hepatocytes, accompanied by reduced mRNA levels of M-CSF, CCL3, and CCL4, and no change of TNF-α, IFN-γ, and MCP-1 (Figure 9B). The increased synthesis of IL-6, GM-CSF, IL-2, CCL5, and CXCL10 in doxycycline-treated LAP-Tg/KO hepatocytes was similar to that observed in the whole liver of doxycycline-treated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice, suggesting that the changes of these cytokines and chemokines syntheses were mainly contributed by hepatocytes, whereas the syntheses of other cytokines and chemokines were contributed by other cell types in the liver.

Figure 9.

In vitro doxycycline treatment of primary hepatocytes from untreated liver-activated promoter (LAP)–driven tTA transgene and (tetO)7-CMV-hLAL transgene with lal−/− (LAP-Tg/KO) triple mice induces synthesis and secretion of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Hepatocytes isolated from lal+/+ [wild type (WT)] and doxycycline-untreated LAP-Tg/KO triple mice were treated with doxycycline in vitro for 5 days. A: The concentrations of IL-6, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), and chemokine ligand (CCL)-5 in the culture medium were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. B: Quantitative real-time PCR analyses of mRNA expression levels of cytokines and chemokines in the isolated hepatocytes of lal+/+ (WT) and LAP-Tg/KO mice treated with or without doxycycline. The relative gene expression was normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mRNA, and analyses were performed by the 2−ΔΔCT method. Data are expressed as means ± SD. n = 4. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. IFNγ, interferon-γ; TNFα, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Discussion

There are two major cell populations in the liver, hepatocytes and Kupffer cells (macrophages), which work together to maintain liver homeostasis and function. Imbalance of neutral lipid metabolism controlled by LAL in these two cell populations contributes greatly to various liver diseases. Accumulation of neutral lipids (as evident by Oil Red-O staining) in lal−/− hepatocytes and myeloid cells results in major liver malformation with significantly enlarged yellowish mass, destruction of the anatomy structure (Figure 2), and massive MDSC infiltration (Figure 6).13 Two transgenic lines have been designed to evaluate the functional roles of LAL in hepatocytes versus myeloid cells.

We have previously established a myeloid-specific hLAL expression mouse model to rescue the myeloid LAL deficiency in c-fms-rtTA/(tetO)7-CMV-hLAL; lal−/− triple mice (named c-fms-Tg/KO mice).13 The myeloid cell-specific expression of hLAL in c-fms-Tg/KO mice has approximately 60% of the wild-type LAL activity level in the liver. The expression of hLAL in the myeloid cells mainly corrected the lipid storage in the Kupffer cells and only partially corrected the lipid storage in the liver and small intestine.13 The expression of hLAL in the myeloid cells reduced myeloid cell infiltration in the liver and other organs.11,13 Further characterization of c-fms-Tg/KO mice revealed that the myeloid expression of hLAL reverses the elevated level of MDSCs starting from the early developing stage of granular myeloid progenitor cells in the bone marrow. Myeloid expression of hLAL in c-fms-Tg/KO mice partially reversed inhibition of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell development in the thymus and maturation in the spleen.11

In comparison, this study found that hLAL-specific expression in the hepatocytes almost completely corrected liver malformation in LAP-Tg/KO mice (Figure 2) and myeloid cell infiltration (Figure 3, C, D, G, H, K, and L). Simultaneously, it reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines and the MDSC level (Figures 6, 8, and 9), which resulted in recovery of T-cell and B-cell populations in the liver (Figure 7). Interestingly, hLAL-specific expression in the hepatocytes reduced MDSCs and increased T-cell and B-cell populations in other organs as well (Figures 6 and 7). This observation indicates that hLAL made in the liver is secreted into the circulation system and affects distant organs. LAL deficiency in both residential hepatocytes and myeloid cells is responsible for liver disease formation. Notably, the mouse version and the human version of LAL are functionally interchangeable in animal models. These animal models (LAP-Tg/KO mice, c-fms-Tg/KO mice) with overexpression of human LAL will greatly benefit LAL human research.

In addition to WD and CESD, patients with mutations in the LAL gene have been reported to associate with liver carcinogenesis.32 When tested in the lal−/− mouse model, we have recently discovered that LAL deficiency–induced inflammation plays crucial roles at all stages of tumor development.24 In lal−/− mice, B16 melanoma metastasized in the liver and lung of allogeneic lal−/− mice, which was suppressed in allogeneic lal+/+ mice due to immune rejection. Interestingly and importantly, in addition to the immune suppressive function, we found that MDSCs from lal−/− mice alone directly stimulated B16 melanoma cell in vitro proliferation and in vivo growth and metastasis.24 Cytokines (ie, IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) from lal−/− MDSCs are required for B16 melanoma proliferation.24 In addition to MDSCs, it seems that hepatocytes were also responsible for production of tumor-promoting cytokines as found here. hLAL-specific expression in the hepatocytes reduced expression of tumor-promoting cytokines (Figures 8 and 9), as well as MDSCs (Figure 6). Taken together, both immune cells and tumor-promoting cytokines contribute to tumor growth and metastasis in allogeneic lal−/− mice. As a consequence, B16 melanoma metastasis was almost completely blocked in the liver of allogeneic LAP-Tg/KO mice, an indication of recovery of immune rejection to tumor cells. Importantly, reduction of B16 melanoma metastasis in the distant organ lung was also observed by hLAL-specific expression in the hepatocytes (Figure 5).

In summary, LAL in hepatocytes plays critical roles in maintaining liver homeostasis and function. The molecular mechanisms that mediate LAL functions in hepatocytes can be two-fold. First, the derivatives of free fatty acid metabolites serve as hormonal ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ). Activation of PPARγ by these ligands inhibits proinflammatory molecule (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) production33–35 and induces MDSC expansion.22 PPARγ ligand treatment improves the pathogenic phenotypes in the lungs of lal−/− mice.36 Second, Affymetrix GeneChip microarray analysis and Ingenuity Pathway Analysis identified the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) as a major signaling pathway in mediating lal−/− MDSCs malfunctions, including immunosuppression and tumor stimulation.37 Membrane trafficking causes mTOR to shuttle to lysosomes and regulate mTOR signaling.38,39 The role of PPARγ and mTOR pathways in mediating LAL functions needs to be explored further.

Acknowledgments

We thank Katlin L. Walls and Michele Klunk for animal maintenance and genotyping and editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants HL087001 (H.D.) and CA138759 and CA152099 (C.Y.).

Disclosures: None declared.

Contributor Information

Hong Du, Email: hongdu@iupui.edu.

Cong Yan, Email: coyan@iupui.edu.

References

- 1.Grabowski G.A., Du H., Charnas L. Lysosomal acid lipase deficiencies: the wolman disease/cholesteryl ester storage disease spectrum. In: Valle D., Voglstein B., Kinzler K.W., Antonarakis S.E., Ballabio A., editors. The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease (OMMBID) ed 9. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assmann G., Seedorf U. 8th Edition. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Diseases. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yan C., Du H. Lysosomal acid lipase is critical for myeloid-derived suppressive cell differentiation, development, and homeostasis. World J Immunol. 2014;4:42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beaudet A.L., Ferry G.D., Nichols B.L., Jr., Rosenberg H.S. Cholesterol ester storage disease: clinical, biochemical, and pathological studies. J Pediatr. 1977;90:910–914. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(77)80557-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein D.L., Hulkova H., Bialer M.G., Desnick R.J. Cholesteryl ester storage disease: review of the findings in 135 reported patients with an underdiagnosed disease. J Hepatol. 2013;58:1230–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fouchier S.W., Defesche J.C. Lysosomal acid lipase A and the hypercholesterolaemic phenotype. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2013;24:332–338. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e328361f6c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du H., Duanmu M., Witte D., Grabowski G.A. Targeted disruption of the mouse lysosomal acid lipase gene: long-term survival with massive cholesteryl ester and triglyceride storage. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1347–1354. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.9.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du H., Heur M., Duanmu M., Grabowski G.A., Hui D.Y., Witte D.P., Mishra J. Lysosomal acid lipase-deficient mice: depletion of white and brown fat, severe hepatosplenomegaly, and shortened life span. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:489–500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qu P., Du H., Wilkes D.S., Yan C. Critical roles of lysosomal acid lipase in T cell development and function. Am J Pathol. 2009;174:944–956. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.080562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qu P., Shelley W.C., Yoder M.C., Wu L., Du H., Yan C. Critical roles of lysosomal acid lipase in myelopoiesis. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:2394–2404. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qu P., Yan C., Blum J.S., Kapur R., Du H. Myeloid-specific expression of human lysosomal acid lipase corrects malformation and malfunction of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in lal-/- mice. J Immunol. 2011;187:3854–3866. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lian X., Yan C., Yang L., Xu Y., Du H. Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency causes respiratory inflammation and destruction in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;286:L801–L807. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00335.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yan C., Lian X., Li Y., Dai Y., White A., Qin Y., Li H., Hume D.A., Du H. Macrophage-specific expression of human lysosomal acid lipase corrects inflammation and pathogenic phenotypes in lal-/- mice. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:916–926. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.051327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rothe G., Stohr J., Fehringer P., Gasche C., Schmitz G. Altered mononuclear phagocyte differentiation associated with genetic defects of the lysosomal acid lipase. Atherosclerosis. 1997;130:215–221. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(97)06065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elinav E., Nowarski R., Thaiss C.A., Hu B., Jin C., Flavell R.A. Inflammation-induced cancer: crosstalk between tumors, immune cells and microorganisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:759–771. doi: 10.1038/nrc3611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berasain C., Castillo J., Perugorria M.J., Latasa M.U., Prieto J., Avila M.A. Inflammation and liver cancer: new molecular links: steroid enzymes and cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1155:206–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.03704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solito S., Marigo L., Pinton L., Damuzzo V., Mandruzzato S., Bronte V. Myeloid-derived suppressive cells heterogeneity in human cancers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1319:47–65. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y., Qin Y., Li H., Wu R., Yan C., Du H. Lysosomal acid lipase over-expression disrupts lamellar body genesis and alveolar structure in the lung. Int J Exp Pathol. 2007;88:427–436. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2007.00547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Folch J., Lees M., Sloane S.S. A simple method for isolation and purification of otal lipids from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;125:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du H., Schiavi S., Levine M., Mishra J., Heur M., Grabowski G.A. Enzyme therapy for lysosomal acid lipase deficiency in the mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:1639–1648. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.16.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qu P., Du H., Li Y., Yan C. Myeloid-specific expression of Api6/AIM/Sp alpha induces systemic inflammation and adenocarcinoma in the lung. J Immunol. 2009;182:1648–1659. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu L., Yan C., Czader M., Foreman O., Blum J.S., Kapur R., Du H. Inhibition of PPARgamma in myeloid-lineage cells induces systemic inflammation, immunosuppression, and tumorigenesis. Blood. 2012;119:115–126. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-363093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qu P., Du H., Wang X., Yan C. Matrix metalloproteinase 12 overexpression in lung epithelial cells plays a key role in emphysema to lung bronchioalveolar adenocarcinoma transition. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7252–7261. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao T., Du H., Ding X., Walls K., Yan C. Activation of mTOR pathway in myeloid-derived suppressor cells stimulates cancer cell proliferation and metastasis in lal mice. Oncogene. 2014;34:1938–1948. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klaunig J.E., Goldblatt P.J., Hinton D.E., Lipsky M.M., Chacko J., Trump B.F. Mouse liver cell culture. I. Hepatocyte isolation. In Vitro. 1981;17:913–925. doi: 10.1007/BF02618288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klaunig J.E., Goldblatt P.J., Hinton D.E., Lipsky M.M., Trump B.F. Mouse liver cell culture, II: primary culture. In Vitro. 1981;17:926–934. doi: 10.1007/BF02618289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sando G.N., Rosenbaum L.M. Human lysosomal acid lipase/cholesteryl ester hydrolase: purification and properties of the form secreted by fibroblasts in microcarrier culture. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:15186–15193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zschenker O., Bahr C., Hess U.F., Ameis D. Systematic mutagenesis of potential glycosylation sites of lysosomal acid lipase. J Biochem. 2005;137:387–394. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu L., Du H., Li Y., Qu P., Yan C. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3C) promotes myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion and immune suppression during lung tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2131–2141. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Balkwill F. Cancer and the chemokine network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:540–550. doi: 10.1038/nrc1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li K., Li N.L., Wei D., Pfeffer S.R., Fan M., Pfeffer L.M. Activation of chemokine and inflammatory cytokine response in hepatitis C virus-infected hepatocytes depends on Toll-like receptor 3 sensing of hepatitis C virus double-stranded RNA intermediates. Hepatology. 2012;55:666–675. doi: 10.1002/hep.24763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elleder M., Chlumska A., Hyanek J., Poupetova H., Ledvinova J., Maas S. Subclinical course of cholesteryl ester storage disease in an adult with hypercholesterolemia, accelerated atherosclerosis, and liver cancer. J Hepatol. 2000;32:528–534. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80407-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang C., Ting A.T., Seed B. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit production of monocyte inflammatory cytokines. Nature. 1998;391:82–86. doi: 10.1038/34184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ricote M., Li A.C., Willson T.M., Kelly C.J., Glass C.K. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is a negative regulator of macrophage activation. Nature. 1998;391:79–82. doi: 10.1038/34178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang A.C., Dai X., Luu B., Conrad D.J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma regulates airway epithelial cell activation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;24:688–693. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.24.6.4376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lian X., Yan C., Qin Y., Knox L., Li T., Du H. Neutral lipids and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-{gamma} control pulmonary gene expression and inflammation-triggered pathogenesis in lysosomal acid lipase knockout mice. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:813–821. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62053-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan C., Ding X., Dasgupta N., Wu L., Du H. Gene profile of myeloid-derived suppressive cells from the bone marrow of lysosomal acid lipase knock-out mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30701. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Korolchuk V.I., Saiki S., Lichtenberg M., Siddiqi F.H., Roberts E.A., Imarisio S., Jahreiss L., Sarkar S., Futter M., Menzies F.M., O'Kane C.J., Deretic V., Rubinsztein D.C. Lysosomal positioning coordinates cellular nutrient responses. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:453–460. doi: 10.1038/ncb2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zoncu R., Efeyan A., Sabatini D.M. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:21–35. doi: 10.1038/nrm3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]