Abstract

The first total synthesis of (+)-luteoalbusins A and B is described. Highly regio- and diastereoselective chemical transformations in our syntheses include a Friedel-Crafts C3-indole addition to a cyclotryptophan derived diketopiperazine, a late-stage diketopiperazine dihydroxylation and C11-sulfidation sequence, in addition to congener-specific polysulfane synthesis and cyclization to the corresponding epipolythiodiketopiperazine. We also report the cytoxicity of both alkaloids, and closely related derivatives, against A549, HeLa, HCT116 and MCF7 human cancer cell lines.

Graphical abstract

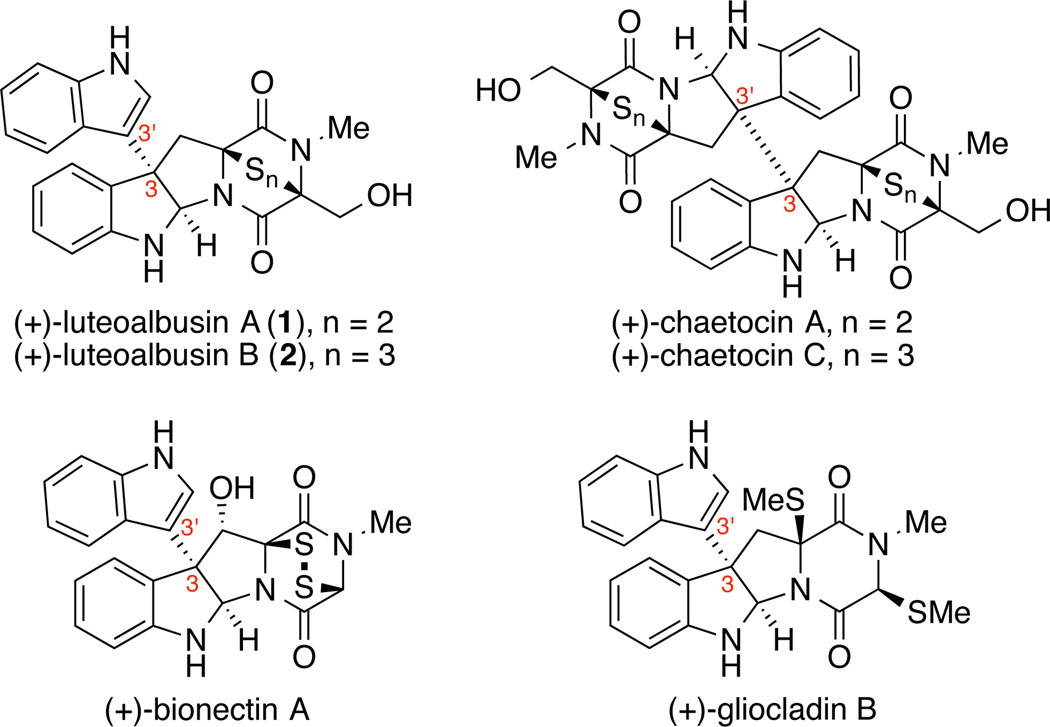

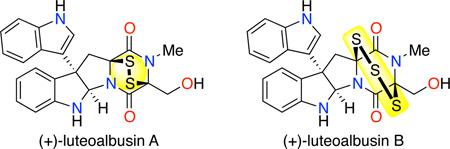

Epipolythiodiketopiperazine alkaloids represent a structurally complex and biologically active class of secondary fungal metabolites.1,2 Many members of this family of natural products share a cyclo-tryptophan core and an eponymous epipolythiodiketopiperazine (ETP) substructure (Figure 1). Notwithstanding these similarities, individual ETP alkaloids offer an array of structural variations including the nature of the substituent at the C3 quaternary carbon,3,4,5 the degree of oxidation of the core structure,4l,n the dipeptide constituting the diketopiperazine substructure, in addition to the nature and degree of sulfuration of the ETP structure.3n,4i,6 Access to complex ETPs via total synthesis requires efficient strategies and chemical transformations adaptable to this repertoire of structural diversity along with the respective challenges offered by each distinct combination. As part of our program focused on accessing structurally unique ETP alkaloids, we became interested in (+)-luteoalbusin A (1) and (+)-luteoalbusin B (2), recently discovered ETPs isolated from the marine fungi, Acrostalagmus luteoalbus SCSIO F457, by Wang and coworkers.7 These natural products contain a C3-(3'-indolyl) substituent and an ETP substructure, possessing a di or tri-sulfide bridge with a diketopiperazine composed of tryptophan and serine. These structural features of (+)-luteoalbusins A (1) and B (2) are shared in part with the related ETP alkaloids (+)-gliocladin B and (+)-chaetocins A and C (Figure 1) that were the subject of our prior investigations.3n,4i Herein, we report the first total syntheses of (+)- luteoalbusins A (1) and B (2) using a concise and unified approach as well as their cytotoxic activity against four human cancer cell lines.

Figure 1.

Representative ETP Alkaloids

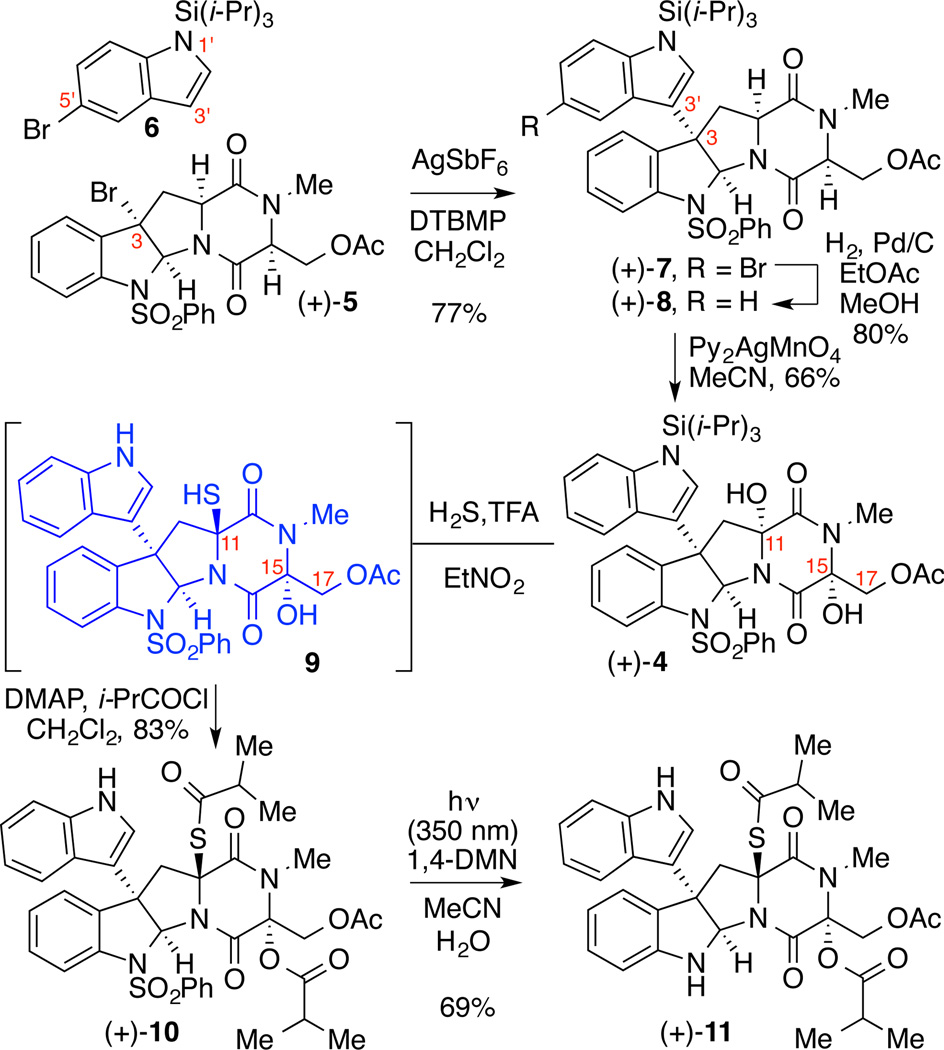

Our retrosynthetic analysis of these natural alkaloids is illustrated in Scheme 1. We envisioned having efficient access to both alkaloids from a versatile C11-thiolated diketopiperazine 3 via the application of our polysulfane cyclization chemistry to accurately introduce the disulfane and trisulfane substructures in the final stage of the synthesis.3n,6o The regio- and diastereoselective C11-sulfidation of the key dihydroxylated diketopiperazine (+)-4 was planned based on the faster expected rate of iminium ion formation at C11 vs. C15 due to the inductive electron withdrawing influence of the C17 acetate. Rapid access to the key intermediate (+)-4 was expected through introduction of the C3-indolyl substituent by Friedel-Crafts arylation4d followed by application of our diketopiperazine dihydroxylation chemistry.3l Tetracyclic diketopiperazine bromide (+)-5 is readily available in multigram scale as outlined in our synthesis of (+)-chaetocins A and C.3n

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic Analysis

Our unified synthesis of alkaloids (+)-1 and (+)-2 began with the silver-mediated Friedel-Crafts arylation of diketopiperazine (+)-5 (Scheme 2).8 Based on our earlier studies concerning the regioselective introduction of the C3-indolyl substructure, we employed the readily available 1-(triisopropylsilyl)-1H-indole (6) to provide the C3–C3' linkage, exclusively.4i Treatment of a solution of C3-bromo diketopiperazine (+)-5 in dichloromethane with indole derivative 6 and silver(I) hexafluoroantimonate in the presence of 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylpyridine (DTBMP) at 23 °C afforded the desired C3-indolylhexacycle (+)-7 in 77% yield. Exposure of C3-bromoindolyl diketopiperazine and palladium on carbon to an atmosphere of dihydrogen in ethyl acetate–methanol (2:3) at 23 °C gave C3-indolyl diketopiperazine (+)-8 in 80% yield. Consistent with our biogenetically inspired strategy for synthesis of ETP alkaloids,2f,3l further functionalization of the diketopiperazine substructure was addressed after construction of the hexacyclic core. Treatment of diketopiperazine (+)-8 in acetonitrile with bis(pyridine)silver(I) permanganate (Py2AgMnO4) provided the desired dihydroxylated diketopiperazine (+)-4 as a single diastereomer in 66% yield.3l,9 This oxidation reaction likely proceeds via a stereoretentive radical rebound mechanism with initial hydrogen atom abstraction, followed by trapping of the generated carbon centered radical.10 For the subsequent sulfidation of the C11 position, we have previously observed in related systems that non-nucleophilic solvents are necessary for the selective ionization of the C11 alcohol and trapping with an alkyl mercaptan.4n Furthermore, due to the inductive effect of the neighboring heteroatom at C17, the rate of ionization at the C15 position was anticipated to be decreased.3n Thus, exposure of diol (+)-4 to trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in hydrogen sulfide saturated nitroethane at 0 °C produced monothiol 9 with concomitant loss of the tri-iso-propylsilyl group at the N1' position. After concentrating the reaction mixture, the residue was treated with 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) and isobutyryl chloride in dichloromethane at 0 °C to generate the desired isobutyrylthioester (+)-10 in 83% yield over two steps. The isobutyrate groups at C11 and C15 served two purposes: Firstly, activation of the tertiary alcohol at C15 through esterification with isobutyryl chloride is required for the polysulfane cyclization step. Secondly, acylation of the C11 thiol was necessary to enhance the stability of the molecule for the photoinduced removal of the N1-benzenesulfonyl group.11 Thus, irradiation of benzenesulfonyl (+)-10 with light (350 nm) in the presence of 1,4-dimethoxynapthalene (1,4-DMN) in buffered aqueous ascorbic acid–acetonitrile solution afforded the desired key indoline (+)-11 in 69% yield.

Scheme 2.

Preparation of Key Intermediate (+)-11

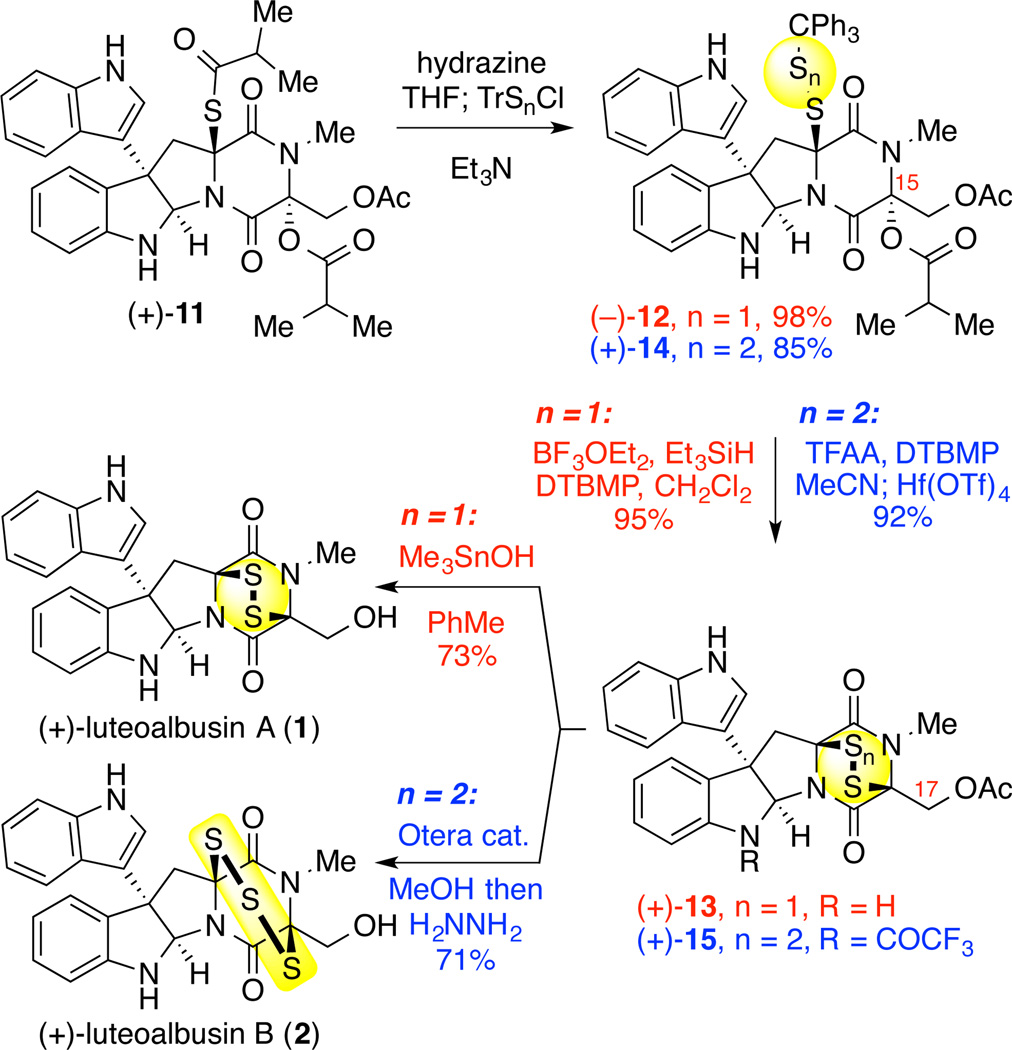

The final stages of our synthesis of (+)-luteoalbusin A (1) relied on selective hydrazinolysis of the thioisobutyryl group at C11 over the C15 isobutyrate by treatment with one equivalent of hydrazine in THF at 0 °C (Scheme 3). Subsequent exposure of the hemithioaminal 3 to triphenylmethanesulfenyl chloride (TrSCl) and triethylamine provided the desired mixed disulfide (−)-12 in 98% yield.3n Activation of the C15 isobutyrate group and subsequent cyclization of the disulfide with concomitant loss of the triphenylmethyl cation was accomplished through the treatment of disulfide (−)-12 with boron trifluoride diethyl etherate in dichloromethane at 23 °C to furnish (+)-luteoalbusin A acetate (13) in 95% yield. Unveiling of the C17 alcohol from acetate (+)-13 was achieved by utilizing trimethyltin hydroxide12 in toluene at 90 °C to afford (+)-luteoalbusin A (1) in 73% yield. All spectroscopic data for our synthetic sample of (+)-luteoalbusin A (1) are consistent with those reported by the Wang.7,8

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of (+)-Luteoalbusin A (1) and B (2)

The total synthesis of (+)-luteoalbusin B (2) also utilized the key intermediate thioisobutyrate (+)-11. Sequential treatment of thioisobutyrate (+)-11 with hydrazine, followed by the addition of chloro(triphenylmethyl)disulfane (TrSSCl)8 under basic conditions as described above produced the corresponding mixed trisulfide (+)-14 in 85% yield (Scheme 3).3n Notably, exposure of trisulfide (+)-14 to boron trifluoride diethyl etherate in dichloromethane resulted in decomposition of the substrate, an outcome likely caused by competing pathways involving the indoline nitrogen due to a decrease in the rate of cyclization relative to disulfide (−)-12.3n Based on this observation we reasoned that protection of the N1 indoline nitrogen of trisulfide (+)-14 as well as employing a solvent with higher dielectric constant might increase the cyclization efficiency. Thus, in situ acylation of the N1 indoline nitrogen of trisulfide (+)-14 with trifluoroacetic anhydride and DTBMP in acetonitrile, followed by the addition of boron trifluoride diethyletherate at 23 °C afforded the desired epitrithiodiketopiperazine (+)-15 in 43% yield.

Importantly, replacing boron trifluoride diethyletherate with hafnium trifluoromethanesulfonate as the Lewis acid additive further enhanced the cyclization of the trisulfide to provide epitrithiodiketopiperazine (+)-15 in 92% yield as a 1.6:1 mixture of epitrisulfide conformers (Scheme 3). Sequential C17-deacylation of luteoalbusin B derivative (+)-15 by mild methanolysis using Otera’s catalyst13 followed by N1-deacylation by hydrazinolysis3n afforded the first synthetic sample of (+)-luteoalbusin B (2) in 71% yield as a 4:1 mixture of epitrisulfide conformers. All spectroscopic data for our synthetic sample of (+)-luteoalbusin B (2) are consistent with those reported by the Wang.7,8

Epipolythiodiketopiperazine alkaloids are known to possess an impressive array of potent biological activities including anticancer,6o,q antiviral, and antibacterial properties.14 Earlier studies have linked the unique biological activity of these natural products to their polysulfide structures.14h,i Recently, we disclosed a comprehensive SAR study of a large collection of natural and synthetic ETP derivatives for cytotoxic activity against multiple human cancer cell lines.6o As part of our ongoing interest to evaluate the translational potential of ETPs, we examined synthetic (+)-luteoalbusins A (1) and B (2) as well as all novel synthetic intermediates described above prepared en route to both natural products for cytotoxic activity against human lung carcinoma (A549), cervical carcinoma (HeLa), colorectal carcinoma (HCT116) and breast carcinoma (MCF7) cell lines.8 Among all compounds tested, natural products (+)-1 and (+)-2 and acetylated derivatives (+)-13 and (+)-15, also possessing a bridged polysulfide, were found to exhibit significant anti-cancer activity (Table 1). Both natural alkaloids (+)-1 and (+)-2 displayed consistently high cytotoxicity across all cell lines tested. However, the C17 acetylated deriviatives ETP (+)-13 and ETP (+)-15 were found to be less potent relative to the (+)-luteoalbusins A (1) and B (2), respectively. The IC50 values for ETPs (+)-1, (+)-2, (+)-13, and (+)-15 across the four human cancer cell lines tested are listed in Table 1. Our results complement those reported by the Wang group.15

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity (IC50, µM) of (+)-Luteoalbusin A and B and related derivatives against A549, HeLa, HCT116 and MCF7 cancer cell lines8

| Compd | A549 | HeLa | HCT116 | MCF7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (+)-13 | 11.31 ± 2.54 | 5.50 ± 2.81 | 4.73 ± 4.34 | 5.17 ± 0.20 |

| (+)-15 | 11.02 ± 0.23 | 5.19 ± 2.05 | 5.11 ± 3.37 | 6.53 ± 0.84 |

| (+)-1 | 2.33 ± 0.59 | 1.00 ± 0.24 | 1.22 ± 1.02 | 0.86 ± 0.13 |

| (+)-2 | 0.91 ± 0.29 | 0.52 ± 0.15 | 0.58 ± 0.38 | 0.51 ± 0.14 |

We report the first total synthesis of (+)-luteoalbusins A (1) and B (2). This unified synthetic strategy was based on our versatile and biogenetically inspired2f late-stage functionalization of a complex diketopiperazine via an oxidation followed by sulfidation sequence to access the desired epidi- and epitrithiodiketopiperazines 1 and 2, respectively. Our synthesis relied on highly regioand diastereoselective chemical transformations including a Friedel-Crafts C3-indole addition to the readily available diketopiperazine (+)-5, dihydroxylation and C11-sulfidation of C3-(3'-indoyl)diketopiperazine (+)-8, and the use of a versatile thioisobutyrate (+)-11 as a substrate for congener-specific polysulfane synthesis and cyclization to access both (+)-luteoalbusins A (1) and B (2). We also report the cytoxicity of both alkaloids (+)-1 and 2 along with closely related ETPs (+)-13 and (+)-15 against A549, HeLa, HCT116 and MCF7 human cancer cell lines.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We are grateful for financial support from NIH-NIGMS (GM089732). T.C.A. acknowledges a National Science Foundation graduate fellowship. We acknowledge the NSF under CCI Center for selective C–H functionalization (CHE-1205646) for support of our diketopiperazine dihydroxylation chemistry. This work was supported in part by the Koch Institute Support (core) Grant P30-CA14051 from the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Experimental procedures and spectra data for all new compounds. The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI:

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Author Contributions

T.C.A. and J.N.P. have contributed equally to this manuscript.

REFERENCE

- 1.(a) Anthoni U, Christophersen C, Nielsen PH. Naturally Occurring Cyclotryptophans and Cyclotryptamines. In: Pelletier SW, editor. Alkaloids: Chemical and Biological Perspectives. Vol. 13. London: Pergamon; 1999. pp. 163–236. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hino T, Nakagawa M. Chemistry and Reactions of Cyclic Tautomers of Tryptamines and Tryptophans. In: Brossi A, editor. The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Pharmacology. Vol. 34. New York: Academic; 1989. pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Gardiner DM, Waring P, Howlett BJ. Microbiology. 2005;151:1021. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27847-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Patron NJ, Waller RF, Cozijnsen AJ, Straney DC, Gardiner DM, Nierman WC, Howlett BJ. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007;7:174. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Steven A, Overman LE. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:5488. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Huang R, Zhou X, Xu T, Yang X, Liu Y. Chem. Biodiversity. 2010;7:2809. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200900211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Iwasa E, Hamashima Y, Sodeoka M. Isr. J. Chem. 2011;51:420. [Google Scholar]; (f) Kim J, Movassaghi M. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015;48:1159. doi: 10.1021/ar500454v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.For selected synthesis of cyclotryptamines with C3sp3–C3'sp3 linkage, see: Hendrickson JB, Rees R, Göschke R. Proc. Chem. Soc. Lond. 1962;383 Hino T, Yamada S-I. Tetrahedron Lett. 1963;4:1757. Scott AI, McCapra F, Hall ES. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964;86:302. doi: 10.1021/ja01017a041. Fang C-L, Horne S, Taylor N, Rodrigo R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1994;116:9480. Overman LE, Paone D, Stearns BA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:7702. Somei M, Oshikiri N, Hasegawa M, Yamada F. Heterocycles. 1999;51:1237. Overman LE, Larrow JF, Stearns BA, Vance JM. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:213. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000103)39:1<213::aid-anie213>3.0.co;2-z. Ishikawa H, Takayama H, Aimi N. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:5637. Matsuda Y, Kitajima M, Takayama H. Heterocycles. 2005;65:1031. Movassaghi M, Schmidt M. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:3725. doi: 10.1002/anie.200700705. Movassaghi M, Schmidt M, Ashenhurst JA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:1485. doi: 10.1002/anie.200704960. Kim J, Ashenhurst JA, Movassaghi M. Science. 2009;324:238. doi: 10.1126/science.1170777. Iwasa E, Hamashima Y, Fujishira S, Higuchi E, Ito A, Yoshida M, Sodeoka M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:4078. doi: 10.1021/ja101280p. Kim J, Movassaghi M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14376. doi: 10.1021/ja106869s. Movassaghi M, Ahmad OK, Lathrop SA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:13002. doi: 10.1021/ja2057852. Lathrop SP, Movassaghi M. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:333–340. doi: 10.1039/C3SC52451E.

- 4.For selected synthesis of cyclotryptamines with C3sp3–C7'sp2 linkages, see: Overman LE, Peterson EA. Tetrahedron. 2003;59:6905. Kodanko JJ, Hiebert S, Peterson EA, Sung L, Overman LE, de Moura Linck V, Goerck GC, Amador TA, Leal MB, Elisabetsky E. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:7909. doi: 10.1021/jo7013643. Schammel AW, Boal BW, Zu L, Mesganaw T, Garg NK. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:4687. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.02.050. Kim J, Movassaghi M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;133:14940. doi: 10.1021/ja206743v. DeLorbe JE, Jabri SY, Mennen SM, Overman LE, Zhang FL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:6549. doi: 10.1021/ja201789v. Snell RH, Woodward RL, Willis MC. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:9116. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103864. Furst L, Narayanam JMR, Stephenson CR. J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:9655. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103145. Trost BM, Xie J, Siber JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:20611. doi: 10.1021/ja209244m. Boyer N, Movassaghi M. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:1798. doi: 10.1039/C2SC20270K. Zhu S, MacMillan DWC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:10815. doi: 10.1021/ja305100g. Kieffer ME, Chuang KV, Reisman SE. Chem. Sci. 2012;3:3170. doi: 10.1039/C2SC20914D. DeLorbe JE, Horne D, Jove R, Mennen SM, Nam S, Zhang FL, Overman LE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:4117. doi: 10.1021/ja400315y. Kieffer ME, Chuang KV, Reisman SE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:5557. doi: 10.1021/ja4023557. Coste A, Kim J, Adams TC, Movassaghi M. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:3191. doi: 10.1039/C3SC51150B.

- 5.For selected synthesis of cyclotryptamines with C3sp3–N1' linkages, see: Matsuda Y, Kitajima M, Takayama H. Org. Lett. 2008;10:125. doi: 10.1021/ol702637r. Newhouse T, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:10886. doi: 10.1021/ja8042307. Espejo VR, Rainier JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:12894. doi: 10.1021/ja8061908. Newhouse T, Lewis CA, Baran PS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:6360. doi: 10.1021/ja901573x. Espejo VR, Li X-B, Rainier JD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8282. doi: 10.1021/ja103428y. Pèrez-Balado C, de Lera AR. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2010;8:5179. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00531b.

- 6.For representative synthesis of epipolythiodiketopiperazines, see: Trown PW. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1968;33:402. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(68)90585-8. Hino T, Sato T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1971;12:3127. Poisel H, Schmidt U. Chem. Ber. 1971;104:1714. Öhler E, Tataruch F, Schmidt U. Chem. Ber. 1973;106:396. doi: 10.1002/cber.19731060205. Ottenheijm HCJ, Herscheid JDM, Kerkhoff GPC, Spande TF. J. Org. Chem. 1976;41:3433. doi: 10.1021/jo00883a024. Coffen DL, Katonak DA, Nelson NR, Sancilio FD. J. Org. Chem. 1977;42:948. doi: 10.1021/jo00426a004. Herscheid JDM, Nivard RJF, Tijhuis MW, Scholten HPH, Ottenheijm HCJJ. Org. Chem. 1980;45:1885. Williams RM, Rastetter WH. J. Org. Chem. 1980;45:2625. Aliev AE, Hilton ST, Motherwell WB, Selwood DL. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006;47:2387. Overman LE, Sato T. Org. Lett. 2007;9:5267. doi: 10.1021/ol702518t. Polaske NW, Dubey R, Nichol GS, Olenyuk B. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2009;20:2742. doi: 10.1016/j.tetasy.2009.10.037. Ruff BM, Zhong S, Nieger M, Bräse S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:935. doi: 10.1039/c2ob06663g. Nicolaou KC, Giguère D, Totokotsopoulos S, Sun Y-P. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:728. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107623. Codelli JA, Puchlopek AL, Reisman SE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:1930. doi: 10.1021/ja209354e. Boyer N, Morrison KC, Kim J, Hergenrother PJ, Movassaghi M. Chem. Sci. 2013;4:1646. doi: 10.1039/C3SC50174D. Takeuchi R, Shimokawa J, Fukuyama T. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:2003. Baumann M, Dieskau AP, Loertscher BM, Walton MC, Nam S, Xie J, Horne D, Overman LE. J. Chem. Sci. 2015;6:4451. doi: 10.1039/c5sc01536g.

- 7.Wang FZ, Huang Z, Shi X-F, Chen YC, Zhang WM, Tian XP, Li J, Zhang S. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:7265. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.08.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.See the Supporting Information for details.

- 9.Firouzabadi H, Vessal B, Naderi M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1978;23:1847. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strassner T, Houk KN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:7821. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamada T, Nishida A, Yonemitsu O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:140. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicolaou KC, Estrada AA, Zak M, Lee SH, Safina BS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:1378. doi: 10.1002/anie.200462207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otera J, Danoh N, Nozaki H. J. Org. Chem. 1991;56:5307. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Vigushin DM, Mirsaidi N, Brooke G, Sun C, Pace P, Inman L, Moody CJ, Coombes RC. Med. Oncol. 2004;21:21. doi: 10.1385/MO:21:1:21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Greiner D, Bonaldi T, Eskeland R, Roemer E, Imhof A. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005;1:143. doi: 10.1038/nchembio721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yanagihara M, Sasaki-Takahashi N, Sugahara T, Yamamoto S, Shinomi M, Yamashita I, Hayashida M, Yamanoha B, Numata A, Yamori T, Andoh T. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:816. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00117.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Zheng CJ, Kim CJ, Bae KS, Kim YH, Kim WG. J. Nat. Prod. 2006;69:1816. doi: 10.1021/np060348t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Isham CR, Tibodeau JD, Jin W, Xu R, Timm MM, Bible KC. Blood. 2007;109:2579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-027326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Cherrier T, Suzanne S, Redel L, Calao M, Marban C, Samah B, Mukerjee R, Schwartz C, Gras G, Sawaya BE, Zeichner SL, Aunis D, Van Lint C, Rohr O. Oncogene. 2009;28:3380. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Chen Y, Guo H, Du Z, Liu XZ, Che Y, Ye X. Cell Proliferation. 2009;42:838. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2009.00636.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Cook KM, Hilton ST, Mecinovic J, Motherwell WB, Figg WD, Schofield CJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;39:26831. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.009498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Isham CR, Tibodeau JD, Jin W, Timm MM, Bible KC. Blood. 2010;109:2579. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-027326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Jiana CS, Guo YW. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2011;9:728. doi: 10.2174/138955711796355276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Liu F, Liu Q, Yang D, Bollag WB, Roberston K, Wu P, Liu L. Cancer. Res. 2011;71:6807. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Yano K, Horinaka M, Yoshida T, Yasuda T, Taniguchi H, Goda AE, Wakada M, Yoshikawa S, Nakamura T, Kawauchi A, Miki T, Sakai T. Int. J. Oncol. 2011;38:365. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2010.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Chaib H, Nebbioso A, Prebet T, Castellano R, Garbit S, Restouin A, Vey N, Altucci L, Collette Y. Leukemia. 2012;26:662. doi: 10.1038/leu.2011.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Isham CR, Tibodeau JD, Bossou AR, Merchan JR, Bible KC. Br. J. Cancer. 2012;106:314. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (o) Takahashi M, Takemoto Y, Shimazu T, Kawasaki H, Tachibana M, Shinkai Y, Takagi M, Shin-ya K, Igarashi Y, Ito A, Yoshida MJ. Antibiot. 2012;65:263. doi: 10.1038/ja.2012.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.For comparison, alkaloids (+)-1 and (+)-2 were reported to have IC50 values of 0.23 ± 0.03 μM and 0.25 ± 0.00 μM, respectively, against MCF-7 cells.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.