Abstract

Background

The population of older people, as well as the number of dependent older people, is steadily increasing; those unable to live independently at home are being cared for in a range of settings. Practical training for nurses and auxiliary care staff has frequently been recommended as a way of improving oral health care for functionally dependent elderly. The aim was improve oral hygiene in institutionalized elderly in Bangalore city by educating their caregivers.

Methods

The study is a cluster randomized intervention trial with an elderly home as unit of randomization in which 7 out of 65 elderly homes were selected. Oral health knowledge of caregivers was assessed using a pre-tested pro forma and later oral-health education was provided to the caregivers of the study group. Oral hygiene status of elderly residents was assessed by levels of debris, plaque of dentate and denture plaque, and denture stomatitis of denture wearing residents, respectively. Oral-health education to the caregivers of control group was given at the end of six months

Results

There was significant improvement in oral-health knowledge of caregivers from the baseline and also a significant reduction of plaque score from baseline score of 3.17 ± 0.40 to 1.57 ± 0.35 post-intervention (p < .001), debris score 2.87 ± 0.22 to 1.49 ± 0.34 (p < .001), denture plaque score 3.15 ± 0.47 to 1.21 ± 0.27 (p < .001), and denture stomatitis score 1.43 ± 0.68 to 0.29 ± 0.53 (p < .001).

Conclusions

The result of the present study showed that there was a significant improvement in the oral-health knowledge among the caregivers and oral-hygiene status of the elderly residents.

Keywords: oral-health promotion, oral-health education, oral disease prevention, elderly people, caregivers

INTRODUCTION

The age distribution of the world’s population is changing. With advances in medicine and prolonged life expectancy, the proportion of older people will continue to rise worldwide. With increasing age, many people suffer sensory and motor impairments, which reduce the effectiveness of their performance of oral health care.(1)

Nurses are frequently unaware of the importance of oral health care within holistic care and are unable to carry it out. Psychological barriers to working in another person’s mouth are widespread among caregivers.(2) Practical training for nurses and auxiliary care staff has frequently been recommended as a way of improving oral health care for functionally dependent elderly.(2,3,4,5) Previous studies which were done on the elderly population in Bangalore city show that the oral health status is very poor among this group, and there is a need for some oral health programs.

Scientific Hypothesis

The scientific hypothesis of the present study is that oral health care education for caregivers would result in significant improvements in elderly residents’ oral health.

The objectives of the study were

To assess the knowledge of oral health among the caretakers

To assess the oral-hygiene practices, oral and denture-hygiene status of the elderl

To provide oral-health education to the caretakers

To evaluate the effectiveness of oral-health education through assessing the oral-hygiene status of the elderly

METHODS

Design of the Study

The study is a cluster randomized intervention trial with an institution as the unit of randomization. Research data were gathered at baseline and at six months after the start of the study. The study was supervised and monitored by two investigators, the first and second authors of this article. The study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (version 17c, 2004) and in accordance with the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO). Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board, The Oxford Dental College and Research Centre, Bangalore, India.

Sample size estimation: There are 65 homes for the elderly in Bangalore city, in which 1,536 elderly are residing (this information was collected from The Elders Helpline 1090, (a project of Bangalore city and Nightingales Medical Trust).

Based on the Plaque Index of previous studies, 80% of the statistical power and 95% confidence, the difference of the Plaque Index 0.6 (SD:1.2) which is equivalent to 20% improvement, values were extracted from the study reported by Frenkel et al 2001.(2) Sample size was estimated and the sample size required for the study was 150 per group. A random sample of seven homes for the elderly accommodating a total of 462 elderly residents in Bangalore city, India was selected.

The homes selected had elderly residents who were totally dependent on their caretakers for their personal- and oral-hygiene care and there was no previous history of an oral health education program. The study is a cluster randomized intervention trial with an institution as unit of randomization. A sample of seven homes were randomly allocated to an intervention or control group, out of which three homes were allotted as study group and four were allotted as control group, which met the required sample of 150 each. Keeping attrition in mind, an additional 10 residents were included. All the caretakers in the homes participated in the study. Once the manager of an institution agreed to participate by written informed consent, the institution was randomly allocated to either the study group or the control group.

Prior to the start of the study, the details of the study were explained to the elderly residents and a written informed consent was obtained from participating residents. To participate in the study, a resident should

be residing in the institution during the entire six-month period;

supply a written informed consent, undersigned by the resident or the resident’s legal representative;

have 10 or more natural teeth or have dentures; and

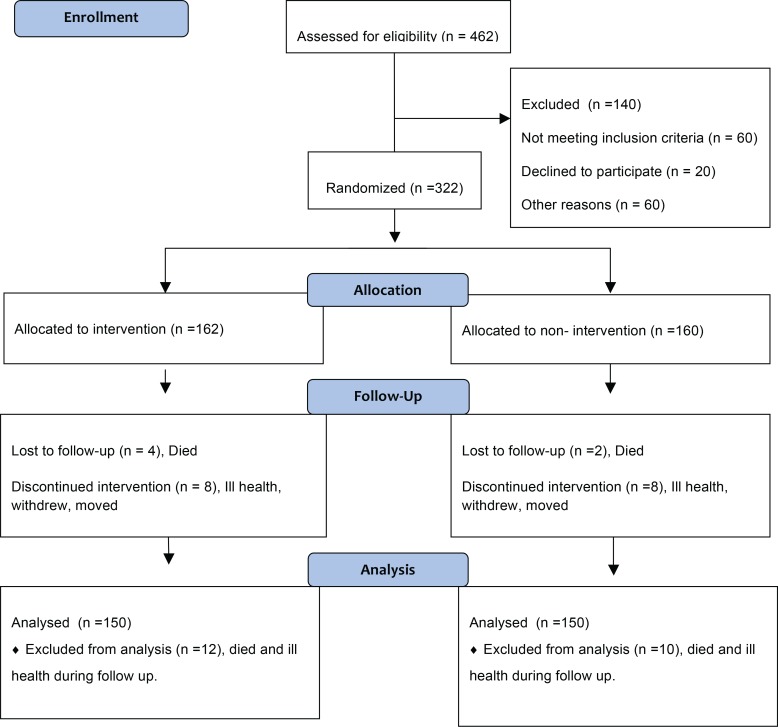

have the cognitive and physical condition required for undergoing an oral examination. Edentulous elderly residents without dentures were excluded from the study. Figure 1 shows the statistics relating to study enrollment, allocation, follow-up, and drop-outs.

FIGURE 1.

Study enrollment, allocation, follow-up and drop-outs

Data Collection

Oral-health knowledge among the caretakers was collected using a 15 item pro forma. Its respective psychometric properties (validity and reliability) were assessed as follows. Content validity was assessed by a panel of eight experts made up of staff members. The purpose was to depict those items with a high degree of agreement among experts. Aiken’s V was used to quantify the concordance between experts for each item; values higher than 0.92 were always obtained.

Education Material

The investigator gave a PowerPoint presentation on oral health to the caretakers. A health education CD and manual were also provided to the respective institutions.

Research data were gathered in the institutions of the intervention and the control groups. At baseline and at six months, an oral examination of the residents was carried out by a trained external examiner. The examiner carried out the data collection after exercising and calibrating the examination criteria and after determining their intra- and inter-examiners’ reliability in a pilot study. The examiner did not know whether an institution was allocated to the intervention or the control group. At baseline, a pro forma with details of every resident of the random sample was completed. The pre-tested pro forma was used to record, dental plaque, debris, denture plaque and denture stomatitis using the debris component of the Simplified Oral Hygiene Index (OHI-S),(7) the Turesky-Gilmore-Glickman modification of the Quigley Hein Plaque Index,(8) a denture plaque index (Addictive Index for Plaque Accumulation by Armbjornsen (as noted in the article by Augsburger et al.(9)), and a denture stomatitis/denture-induced stomatitis test (i.e., the palatal area was examined and denture stomatitis classified according to the method described by Budtz-Jorgensen et al.(6) In addition, oral-hygiene knowledge and practices among the elderly were collected using a questionnaire. The Barthel Index was used for assessing the level of dependency.(6)

Furthermore, at baseline and at six months, a questionnaire addressing the caretakers was completed, which included the knowledge of oral health among the caretakers. At baseline, oral-health education for the caretakers was provided using a PowerPoint presentation to the study group. Reinforcement of oral-health education to the caretakers of the study group was given after three months, and oral-health education was given to the caretakers of the control group at the end of six months. Finally, at the end of the study, a process evaluation was conducted in the institutions using the same proforma used at the baseline.

Statistical Analysis

A descriptive statistical analysis was carried out in the present study. Statistical software, namely SPSS 15.0 was used. Chi-square/Fisher Exact test was used to find the significance of study parameters on a categorical scale between two or more groups. A paired proportion test was used to find the significance of change in proportion from initial to final knowledge and practice assessment. A Student t-test (two-tailed, independent) was used to find the significance of study parameters on a continuous scale between two groups (inter-group analysis) on metric parameters. Significance was assessed at 5% level of significance.

RESULTS

In this study seven homes for the elderly were randomly selected for the study, of which three homes were allotted as the study group and four were allotted as the control group. The study group comprised 162 elderly residents and 38 caretakers and the control group comprised 160 elderly residents and 40 caretakers.

Table 1 shows the distribution of the caretakers according to age.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of caretakers according to age

| Age (yrs) | Study Group | Control Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| n | % | n | % | |

| 18–20 | 14 | 36.8 | 17 | 42.5 |

| 21–30 | 22 | 57.9 | 19 | 47.5 |

| 31–40 | 2 | 5.3 | 4 | 10.0 |

| Total | 38 | 100.0 | 40 | 100.0 |

| Mean ± SD | 22.32±3.88 | 22.70±5.01 | ||

Samples are age matched with p = .710.

Table 2 shows the distribution of the elderly residents based on their dentition status.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of elderly residents according to their dentition status

| Study Group | Control Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Dentate | 97 | 59.8 | 100 | 62.5 |

| Denture wearers | 65 | 40.2 | 60 | 37.5 |

| Total | 162 | 100.0 | 160 | 100.0 |

Table 3 shows the comparative evaluation of oral-health knowledge of caretakers in the study and control groups, and the intra-group comparative evaluation of oral-health knowledge of caretakers. The comparison showed that the oral-health knowledge of the caretakers was the same in both groups but there was a significant improvement in the oral-health knowledge of the caretakers of the study group post-intervention which was statistically significant

TABLE 3.

Comparative evaluation of oral-hygiene knowledge of caretakers in study and control group

| Statements On Knowledge | Group | Initial | Final | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Don’t know | p value | Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Don’t know | p-value | ||

| 1 | Study | 30 (78.9%) | 6 (15.8%) | 2 (5.3%) | .160 | 36 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0(0%) | .493 |

| Control | 36 (90%) | 4 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 35 (94.6%) | 2 (5.4%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| 2 | Study | 15 (39.5%) | 23 (60.5%) | 0 (0%) | .815 | 3 (8.3%) | 33 (91.7%) | 0 (0%) | <.001b |

| Control | 14 (35.0%) | 26 (65.0%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (32.4%) | 25 (67.5%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| 3 | Study | 7 (18.4%) | 28 (73.7%) | 3 (7.9%) | .271 | 0 (0%) | 30 (83.3%) | 6 (16.7%) | <.001b |

| Control | 8 (20.0%) | 32 (80.0%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (29.7%) | 26 (70.3%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| 4 | Study | 17 (44.7%) | 10 (26.3%) | 11 (28.9%) | .640 | 32 (88.9%) | 1 (2.8%) | 3 (8.3%) | .001b |

| Control | 21 (52.5%) | 11 (27.5%) | 8 (20%) | 19 (51.4%) | 10 (27%) | 8 (21.6%) | |||

| 5 | Study | 21 (55.3%) | 13 (34.2%) | 4 (10.5%) | .737 | 32 (88.9%) | 1 (2.8%) | 3 (8.3%) | <.001b |

| Control | 23 (57.5%) | 11 (27.5%) | 6 (15%) | 19 (51.4%) | 11 (29.7%) | 7 (18.9%) | |||

| 6 | Study | 25 (65.8%) | 4 (10.5%) | 9 (23.7%) | .295 | 30 (83.3%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (16.7%) | <.001b |

| Control | 20 (50.0%) | 9 (22.5%) | 11 (27.5%) | 11 (29.7%) | 14 (37.8%) | 12 (32.4%) | |||

| 7 | Study | 22 (57.9%) | 6 (15.8%) | 10 (26.3%) | .216 | 33 (91.7%) | 3 (8.3%) | 0 (0%) | .050a |

| Control | 24 (60.0%) | 11 (27.5%) | 5 (12.5%) | 26 (70.3%) | 8 (21.6%) | 3 (8.1%) | |||

| 8 | Study | 22 (57.9%) | 12 (31.6%) | 4 (10.5%) | .649 | 33 (91.7%) | 3 (8.3%) | 0 (0%) | .010a |

| Control | 23 (57.5%) | 15 (37.5%) | 2 (5.0%) | 24 (64.9%) | 13 (35.1%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| 9 | Study | 33 (86.8%) | 1 (2.6%) | 4 (10.5%) | .800 | 36 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | .248 |

| Control | 32 (80.0%) | 3 (7.5%) | 5 (12.5%) | 34 (91.9%) | 3 (8.1%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| 10 | Study | 17 (44.7%) | 10 (26.3%) | 11 (28.9%) | .880 | 34 (94.4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (5.6%) | <.001b |

| Control | 14 (35.0%) | 13 (32.5%) | 13 (32.5%) | 11 (29.8%) | 13 (35.1%) | 13 (35.1%) | |||

| 11 | Study | 19 (50%) | 11 (28.9%) | 8 (21.1%) | .345 | 0 (0%) | 34 (94.4%) | 2 (5.6%) | <.001b |

| Control | 25 (62.5%) | 11 (27.5%) | 4 (10%) | 21 (56.8%) | 11 (29.7%) | 5 (13.5%) | |||

| 12 | Study | 10 (26.3%) | 27 (71.1%) | 1 (2.6%) | .850 | 1 (2.8%) | 35 (97.2%) | 0 (0%) | <.001b |

| Control | 12 (30.0%) | 26 (65.0%) | 2 (5.0%) | 11 (29.7%) | 26 (70.3%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| 13 | Study | 29 (76.3%) | 1 (2.6%) | 8 (21.1%) | .203 | 36 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | .054a |

| Control | 30 (75.0%) | 5 (12.5%) | 5 (12.5%) | 32 (86.5%) | 5 (13.5%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| 14 | Study | 35 (92.1%) | 3 (7.9%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 | 36 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | .115 |

| Control | 36 (90%) | 4 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 33 (89.2%) | 4 (10.8%) | 0 (0%) | |||

| 15 | Study | 37 (97.4%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0 (0%) | .215 | 1 (2.8%) | 35 (97.2%) | 0 (0%) | <.001b |

| Control | 36 (90%) | 2 (5%) | 2 (5%) | 35 (94.6%) | 1 (2.7%) | 1 (2.7%) | |||

Significant.

Highly significant.

Table 4 shows the comparative evaluation of Debris Index of dentate elderly residents. There was no difference in the mean score of the study group and the control group at baseline (p < .724), and at the end of six months, the mean score was significantly less for the study group compared to the control group (p < .001**).

TABLE 4.

Comparative evaluation of Debris Index of dentate elderly residents

| Initial | Final | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study group | 2.87±0.22 | 1.49±0.34 | <.001a |

| Control group | 2.86±0.24 | 2.88±0.22 | .185 |

| p value | .724 | <.001a | - |

Highly significant.

Mean score of debris in the study group decreased at the end of six months. The difference was statistically significant (p < .001).

Table 5 shows the comparative evaluation of Plaque Index of dentate elderly residents. At the end of six months the mean score of Plaque Index was significantly less for the study group compared to the control group (p < .001).

TABLE 5.

Comparative evaluation of Plaque Index of dentate elderly residents

| Initial | Final | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study group | 3.17±0.40 | 1.57±0.35 | <.001a |

| Control group | 3.03±0.36 | 3.01±0.30 | .830 |

| p value | .009a | <.001a | - |

Highly significant.

Table 6 shows the comparative evaluation of denture plaque of denture wearing elderly residents. At the end of six months the mean score of denture plaque was significantly less for the study group compared to the control group (p < .001).

TABLE 6.

Comparative evaluation of denture plaque of denture-wearing elderly residents

| Initial | Final | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study group | 3.15±0.47 | 1.21±0.27 | <.001a |

| Control group | 2.85±0.54 | 2.83±0.43 | .956 |

| p value | 0.001a | <.001a | - |

Highly significant.

Table 7 shows the comparative evaluation of denture stomatitis of denture wearing elderly residents. At the end of six months the mean score of denture stomatitis was significantly less for the study group when compared to the control group (p < .001).

TABLE 7.

Comparative evaluation of denture stomatitis of denture-wearing elderly residents

| Initial | Final | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Study group | 1.43±0.68 | 0.29±0.53 | <.001b |

| Control group | 1.17±0.76 | 1.16±0.78 | .964 |

| p value | .036a | <.001b | - |

Significant.

Highly significant.

Table 8 shows the pro forma used for evaluating oral-health knowledge of caretakers.

TABLE 8.

Pro forma for evaluating oral-health knowledge of caretakers

| SLNO | Statements |

|---|---|

| 1 | Health of mouth is directly related to body |

| 2 | You can chew just as well with denture tooth as with your natural teeth |

| 3 | When gums bleed during brushing, its best to leave them alone |

| 4 | Older adults with dry mouth get more cavities |

| 5 | The most common cause of dry mouth is medication |

| 6 | Older adults with teeth need to use fluorides |

| 7 | Mouth rinsing are good alternative to daily tooth brushing |

| 8 | People with no teeth need to be seen by a dentist |

| 9 | Dentures should be removed for few hours every day |

| 10 | Dentures those don’t fit well can cause oral cancer |

| 11 | Its normal for residents to have pain and sores in their mouth |

| 12 | Residents who do not cooperate for daily mouth care are best left alone |

| 13 | Dental check-ups are as important as medical |

| 14 | Residents can lose their teeth if they remain dirty |

| 15 | As people get old they naturally lose their teeth |

DISCUSSION

The population of older people as well as the number of dependent older people is steadily increasing. Those unable to live independently at home are being cared for in a range of settings and varying degrees of dependency. These dependent elderly people residing at the old age homes are usually bedridden with compromised health conditions.

Old age is associated with being edentulous or partially edentulous. Epidemiological studies reveal that in general the oral health of elderly people is poor. Caries, periodontal disease, defective dentures and poor oral and denture hygiene are quite common. In addition, an association between poor oral health and adverse medical outcomes has been well documented. The intention of the current study was to evaluate whether an oral-health-education program to the caretakers would create positive and lasting effects in the residents’ oral health care and their oral hygiene status.

In the present study, the level of dependency was assessed using the Barthel Index, which is well adapted to evaluating the functional status of handicapped persons. This index provides an evaluation of the ability to perform basic daily living activities. With this index a total score of < 20 is considered as indicating complete dependence. In the present study the study population was completely dependent, with the mean score of 21.94 ± 8.76.

It was a condition of the ethical committee that all participating residents should give informed consent, and that no elderly resident should be coerced into taking part. This meant that elderly residents with severe cognitive impairment, who could neither understand what participation in the study would involve nor indicate their consent or refusal, had to be excluded. Elderly residents with neither natural teeth nor denture were not suitable for the study, where dental and denture hygiene was the principle outcome, and hence edentulous elderly residents without dentures were excluded.

The present study population comprised 322 functionally dependent elderly residents and 78 caretakers from seven randomly selected homes for the elderly. The participants were allotted to study and control groups respectively. The unit of randomization was the home, and cluster randomization was done. The pre-calibrated examiner who was not involved in the health-education program, carried out the clinical examinations. The use of a single calibrated examiner eliminated an important source of variation. The staffs from all the participating homes for the elderly were asked to conceal their group allocation from the examiner.

In the present study no statistical difference was seen between the age and gender distribution of the caretakers. There was no statistical difference seen between the mean age of the elderly residents but there was a significant difference for gender. In the present study two caretakers from the study group and three caretakers from the control group were lost to follow-up because they had left their jobs and ten elderly residents from the study group and seven elderly residents from the control group were lost to follow-up. This was because some elderly residents died and some were seriously ill, facts which did not permit for oral examinations.

Oral-Health Knowledge of Caretakers

In the present study oral-health-education intervention was given at baseline, and reinforcement was given at the end of three months. At baseline the knowledge of caretakers regarding oral health, importance of oral hygiene, denture care and denture hygiene, importance of dental check-ups was poor. Post-intervention, there was significant improvement in the oral-hygiene knowledge of the caretakers of the study group, whereas there was no improvement in the oral-hygiene knowledge of the caretakers of the control group. There was significant improvement in knowledge on importance of oral health and oral hygiene, use of fluorides, denture care and denture hygiene practices, management of dry mouth, and importance of regular dental check-ups. These results were similar to studies conducted by Paulsson et al.(11) Simons et al.(12) and Nicol et al.(13) These improvements reflected the effectiveness of the oral-health-education program. The present study shows that gain in the knowledge of oral health among caretakers was effective in decreasing the levels of oral diseases in elderly residents.

Oral Hygiene Practices and Oral Hygiene Status of Elderly Residents

In the present study significant improvement was seen in the oral-hygiene practices of the elderly residents in the study group after educating their caretakers. Nicol et al (13) showed similar results. A study by Simons et al.(12) showed contrary results. This change is mainly due to the impact of oral-health education for the caretakers.

Dental Plaque

In the present study the high baseline levels of dental plaque reflected the large proportion of elderly residents who could not or did not brush their teeth, and who did not receive assistance.

Post-intervention, the dental-plaque score significantly decreased in the study group Frenkel et al.(2) Isaksson et al. (14) Peltola et al.(15) and Kullberg et al (16) showed similar results, but these results were contrary to results from the study done by Simons et al.(12)

Debris Score

In the present study the debris score in the study group significantly decreased. These results were similar to those in a study done by Nicol et al.(13) and in contrast to the results from the study conducted by MacEntee et al.(17)

Denture Plaque

Previous studies have shown a significant relation between denture stomatitis and denture plaque, for example, Schou et al. (10) and Lindquist et al.(18) In the present study, the denture plaque score significantly decreased from baseline score. These results were similar to results from the studies by Frenkel et al.(2), Nicol et al.(13) and Peltola et al. (15) and in contrast with the results from the study conducted by Schou et al.(3) and Simons et al.(12)

Denture-Induced Stomatitis

The relationship between high denture plaque levels and diffuse erythema/papillary hyperplasia (i.e., Grade 2 and 3 denture-induced stomatitis) is well documented. The reduction in proportions of elderly residents exhibiting these grades of denture-induced stomatitis reflected the reductions in their denture plaque levels. There was significant reduction of the denture stomatitis score from baseline to post-intervention (p < .001). These results were similar to the results from the studied by Budtz Jorgensen et al.(6) Frenkel et al.(2) and Nicol et al.(13) and in contrast with the results from the study conducted by Schou et al.(3)

There was also a significant improvement in the frequency of cleaning and the usage of materials for cleaning which was reflected in the reductions in the denture plaque and denture stomatitis scores at post-intervention.

To the best of our knowledge and according to all the available data there was significant improvement in the oral-hygiene knowledge of the caretakers of the study group and also in parameters analysed for the elderly residents of the study group. Hence educating caretakers about oral health is very important.

This is of particular importance among the developing countries where economic resources are scarce and where the largest growth in the world’s elderly population is taking place. However it is recognized that within long-term care facilities, numerous problems mitigate against routine provision of oral health care and encourage neglect. Some of the reasons for neglect include the lack of a personal perception of oral-health problems by residents, the inability of residents to articulate a need, family members placing dental care as a low priority, long-term care staff placing patients dental care as a low priority, long-term care staff limitations such as heavy workloads, inadequate oral-hygiene practices, and difficulty in obtaining dental care. In the light of these difficulties it is pertinent to highlight certain groups in residential care where there is evidence of poor oral health and inadequate or restricted access to dental services.

CONCLUSION

The present study showed that the oral-health knowledge among the caretakers of the elderly residents was poor at baseline. At post-intervention there was a significant improvement in the oral-health knowledge among the caretakers and when the caretakers in turn educated the elderly residents, there was a statistically significant improvement in the oral-hygiene practices and oral-hygiene status of the elderly residents. In the present study the oral-health education provided to the caretakers was effective in improving the oral-hygiene status of the elderly residents.

RECOMMENDATIONS

There is a need to standardize assessments of the oral-health knowledge, attitudes, practices, and behaviour of caretakers.

There is a need for studies of longer duration to determine whether changes in oral-health behaviour are merely transient or are actually sustained following these interventions.

The results of the present study should be taken into consideration and caretakers of other homes for the elderly should receive oral-health education.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organisation; Improving oral health among older people. Accessed 12th November, 2011. Available from: http://www.who.int/oral_health/action/groups/en/index1.html. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frenkel HF, Harvey I, Newcombe RG. Improving oral health in institutionalised elderly people by educating caregivers: a randomised controlled trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2001;29(4):289–97. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2001.290408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schou L, Wight C, Clemson N, et al. Oral health promotion for institutionalised elderly. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1989;17(1):2–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb01815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vigild M. Evaluation of an oral health service for nursing home residents. Acta Odontol Scand. 1990;48(2):99–105. doi: 10.3109/00016359009005864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolaci AB, Tesini DA. Improvement in the oral hygiene of institutionalised mentally retarded individuals through training of direct care staff: a longitudinal study. Spec Care Dentist. 1982;2(5):217–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1982.tb00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budtz-Jorgensen E, Mojon P, Rentsch A, et al. Effects of an oral health program on the occurrence of oral candidosis in a long-term care facility. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28(2):141–49. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028002141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene JC, Vermillion JR. The simplified oral hygiene index. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68(1):7–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1964.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turesky S, Gilmore ND, Glickman I. Reduced plaque formation by the chloromethyl analogue of victamine C. J Periodontol. 1970;41(1):41–43. doi: 10.1902/jop.1970.41.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Augsburger RH, Elahi JM. Evaluation of seven proprietary denture cleansers. J Prosthet Dent. 1982;47(4):356–59. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(82)80079-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schou L, Wight C, Cumming C. Oral hygiene habits, denture plaque, presence of yeasts and stomatitis in institutionalised elderly in Lothian, Scotland. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1987;15(2):85–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1987.tb00488.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulsson G, Fridlund B, Holmén A, et al. Evaluation of an oral health education program for nursing personnel in special housing facilities for the elderly. Spec Care Dentist. 1998;18(6):234–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1998.tb01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simons D, Baker P, Jones B, et al. An evaluation of an oral health training programme for carers of the elderly in residential homes. Br Dent J. 2000;188(4):206–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicol R, Petrina Sweeney M, McHugh S, et al. Effectiveness of health care worker training on the oral health of elderly residents of nursing homes. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33(2):115–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isaksson R, Paulsson G, Fridlund B, et al. Evaluation of an oral health education program for nursing personnel in special housing facilities for the elderly. Part II: Clinical aspects. Spec Care Dentist. 2000;20(3):109–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2000.tb00012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peltola P, Vehkalahti MM, Simoila R. Effects of 11-month interventions on oral cleanliness among the long-term hospitalised elderly. Gerodontology. 2007;24(1):14–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2007.00147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kullberg E, Sjögren P, Forsell M, et al. Dental hygiene education for nursing staff in a nursing home for older people. J Adv Nursing. 2010;66(6):1273–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacEntee MI, Wyatt CC, Beattie BL, et al. Provision of mouth-care in long-term care facilities: an educational trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35(1):25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindquist L, Andrup B, Hedegard B. [Proteshygien II. Klinisk vadering av ett hygienprogram for patienter med protessto matitt] [in Swedish] Tandlaek artidningen. 1975;67:872–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]