Abstract

The popularity, demand, and increased federal and private funding for after-school programs have resulted in a marked increase in after-school programs over the past two decades. After-school programs are used to prevent adverse outcomes, decrease risks, or improve functioning with at-risk youth in several areas, including academic achievement, crime and behavioral problems, socio-emotional functioning, and school engagement and attendance; however, the evidence of effects of after-school programs remains equivocal. This systematic review and meta-analysis, following Campbell Collaboration guidelines, examined the effects of after-school programs on externalizing behaviors and school attendance with at-risk students. A systematic search for published and unpublished literature resulted in the inclusion of 24 studies. A total of 64 effect sizes (16 for attendance outcomes; 49 for externalizing behavior outcomes) extracted from 31 reports were included in the meta-analysis using robust variance estimation to handle dependencies among effect sizes. Mean effects were small and non-significant for attendance and externalizing behaviors. A moderate to large amount of heterogeneity was present; however, no moderator variable tested explained the variance between studies. Significant methodological shortcomings were identified across the corpus of studies included in this review. Implications for practice, policy and research are discussed.

Keywords: After-school programs, Attendance, Externalizing behaviors, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Over the past two decades, the number and types of after-school programs have increased substantially. Billions of private and public dollars are spent annually to operate approximately 50,000 public elementary school and additional middle and high school after-school programs across the United States (Parsad and Lewis 2009). After-school programs have developed into “a relatively new developmental context” (Shernoff and Vandell 2007, p. 892) and constitute a type of program that is identifiable as a specific type of program for at-risk youth, yet individual programs are quite heterogeneous (Halpern 1999). Today, after-school programs are structured programs supervised by adults and operate after school during the school year. Unlike extra-curricular activities that also often occur after school, such as sports or academic clubs, after-school programs are comprehensive programs offering an array of activities that may include play and socializing activities, academic enrichment and homework help, snacks, community service, sports, arts and crafts, music, and scouting (Halpern 2002; Vandell et al. 2005). In addition to after-school programs providing a range of activities, the goals and presumed benefits of after-school programs are also diverse. Goals of after-school programs range from providing supervision and reliable and safe childcare for youth during the after-school hours to alleviating many of society’s ills, including crime, the academic achievement gap, substance use, and other behavioral problems and academic shortcomings, particularly for racial/ethnic minority groups and low income students (Dynarski et al. 2004; Weisman et al. 2003; Welsh et al. 2002). In short, after-school programs receive strong support from various stakeholders based on their potentially wide-ranging and far-reaching benefits (Mahoney et al. 2009).

The increase in the number and types of after-school programs over the past decade can be attributed, at least partially, to increased support and spending on after-school programs by the U.S. government. Between 1998 and 2004, federal funding for after-school programs increased from $40 million to over $1 billion primarily due to increased funding from the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (Roth et al. 2010). In addition to a number of educational system changes, the No Child Left Behind Act sought to close the achievement gap through the creation of twentyfirst Century Community Learning Centers to provide academic enrichment during non-school hours primarily in high-poverty and low-performing schools (U.S. Department of Education 2011). The No Child Left Behind Act’s emphasis on high-poverty and low-performing schools concentrated after-school program funds towards at-risk children and youth.

At-risk populations are traditionally comprised of children and adolescents falling within a variety of categories, including low achievement in school or on standardized tests, attendance at a low-performing school, family characteristics such as low socioeconomic status or racial or ethnic minority, or engagement in high-risk behaviors such as truancy or substance use (Lauer et al. 2006). Participants of the twentyfirst Century Community Learning Centers, in particular, are 95 % minority (James-Burdumy et al. 2005). Additionally, roughly 90 % of the 70,000 students in New York participating in The After School Corporation after-school programming are from low-income and minority backgrounds (Welsh et al. 2002). While demand for after-school programs has been found to be higher among lower-income and minority families, substantial barriers, including cost, availability, and safe travel, prevent these households from accessing after-school programs relative to higher-income, Caucasian households (Afterschool Alliance 2014). Given these barriers, high-income adolescents are more likely than low-income adolescents to participate in organized activities (Mahoney et al. 2009). Although at-risk groups must confront extensive barriers to attend after-school programs, at-risk students may have more to gain from attending. In a review by (Lauer et al. 2006), students with low academic achievement prior to after-school participation made greater academic improvements than high-achieving students who also participated in after-school programming. The potential to benefit at-risk students disproportionately is crucial, given the current negative academic and behavioral outcomes facing at-risk adolescents, such as academic grades, substance use, gang involvement, and truancy (McKinsey and Company 2009; Bradshaw et al. 2013; Maynard et al. 2012), along with the negative adulthood outcomes, such as low income, poor health, and risk of incarceration, for individuals with low academic achievement (McKinsey and Company 2009).

While the primary purpose of twentyfirst Century Community Learning Center legislation was to enrich academic opportunities during after school hours with an aim to close the achievement gap, national, state, local, and private funding has also been directed to support after-school programs for a wide variety of non-academic aims (Mahoney et al. 2009). In a survey of twentyfirst Century Community Learning Center administrators, 66 % of administrators cited the provision of a “safe, supervised after-school environment” as a primary objective for their program in comparison to 50 % of administrators listing academic opportunities as a primary objective (Dynarski et al. 2004, p. 10). Additionally, while 85 % of centers offered homework assistance or academic activities to participants, nearly all of the programs (92 %) included a recreational component throughout the year (Dynarski et al. 2004). This trend can also be found for state-level initiatives. The state of California’s After School Safety and Education program, in particular, requires after-school programs to offer strong academic opportunities, but non-academic activities such as sports, arts, and general recreation were also offered by 92, 89, and 87 % of the programs, respectively (Huang et al. 2011). In fact, although California centers were more likely to have improved academic performance than attendance or behavior as a program goal, centers were more likely to meet school attendance and behavioral outcomes. Specifically, 93.6 % of centers set academic improvements as a goal, but only 15.4 % of centers met this goal. On the other hand, 68.0 % set school attendance as a center goal, with 27.8 % of centers meeting the stated goal. Additionally, 69.3 % of centers listed positive behavior change as a goal, with 19.8 % of centers meeting the stated goal (Huang et al. 2011).

The non-academic goals and activities of after-school programs potentially have important implications for youth developmental outcomes. Some after-school programs explicitly or implicitly aim to reduce crime, delinquency and other problematic behaviors in and out of school, decrease substance use, improve socio-emotional outcomes, and improve school engagement and attendance (Richards et al. 2004; Apsler 2009; Bohnert et al. 2009; Durlak et al. 2010). Factors contributing to the purpose of after-school programs extending beyond academic objectives to social and behavioral outcomes derive from research on juvenile crime and youth development. Studies finding a peak in juvenile crime during after-school hours provided rationale for the need for supervision and activities for youth after school to keep youth off the streets and provide positive activities and role models (Newman et al. 2000; Fox and Newman 1997). Moreover, research has found associations between both parental supervision and unstructured time after school to delinquent behavior, substance use, high-risk sexual behavior, risk-taking behaviors, and risk of victimization (Biglan et al. 1990; Gottfredson et al. 2001; Newman et al. 2000; Richardson et al. 1989). By providing a safe-haven and supervised time after school, teaching and promoting new skills, and offering opportunities for positive adult and peer interaction, after-school programs have the potential to curb juvenile crime and positively impact youth developmental outcomes both short and long-term. Public opinion reiterates the importance of after-school programs on behavioral outcomes for children and youth. In a survey of after-school program participants and programs, 73 % of parents and 83 % of participants agreed that after-school program attendance “can help reduce the likelihood that youth will engage in risky behaviors, such as commit a crime or use drugs, or become a teen parent” (Afterschool Alliance 2014, p. 11). Support for after-school programs cuts across political, ethnic, and racial lines, with 84 % of parents approving the use of public funds for after-school programs (Afterschool Alliance 2014).

There is significant public support and theoretical rationale for after-school programs to improve academic and behavioral outcomes; however, “the rapid growth of after-school programming resulted from lobbying and grass roots efforts and was not based on strong empirical findings” (Apsler 2009, p. 2). The influx of after-school programs appears to be “more of a social movement than a policy innovation” (Hollister 2003, p. 3). Indeed, after over a decade of funding from the No Child Left Behind Act and many other local and state initiatives to promote and sustain after-school programs, the extent to which after-school programs positively and significantly affect the wide variety of outcomes they aim to improve remains unclear.

Prior Reviews of After-School Programs

Several reviews (Fashola 1998; Scott-Little et al. 2002; Hollister 2003; Kane 2004; Simpkins et al. 2004; Apsler 2009; Roth et al. 2010) and three meta-analyses (Lauer et al. 2006; Zief et al. 2006; Durlak et al. 2010) have examined outcomes of after-school programs. Overall, prior reviews of after-school programs have yielded mixed and inconclusive findings of effects on various outcomes, but most have concurred that more rigorous evaluations of after-school programs are needed. While there have been several reviews conducted, they vary in regards to quality and rigor, the methods used to conduct the review and synthesize findings, the criteria for inclusion of studies, and the outcomes examined.

In a meta-analysis of after-school programs (Durlak et al. 2010) found an overall positive and statistically significant effect of after-school programs across all outcomes examined (d = 0.22, CI 0.16, 0.29). Positive and significant effects were found for child self-perceptions, school bonding, positive social behaviors, reduction in problem behaviors, achievement test scores, and school grades, but no significant effects on drug use and school attendance. They also examined several moderator variables and found support for moderation on four outcomes for programs that used specific practices (i.e., SAFE: sequenced, active, focused, and explicit) compared to those that did not use those practices. A systematic review and meta-analysis by (Zief et al. 2006) included five studies, researching the impact of after-school programs on a variety of socio-emotional, behavioral, and academic outcomes, and the extent to which access to after-school programs impacts student supervision and participation. The review found limited program impact on academic and behavioral outcomes and a small positive impact on instance of self-care. In (Kane 2004) review of the results of four after-school program evaluations, three of the four studies found no statistically significant effect on attendance, mixed effects on grades within and across studies, some evidence of improvement in homework completion, positive effects on parental engagement in school, and limited impact on child self-care. Scott-Little and colleagues (Scott-Little et al. 2002) concluded in their review of 23 studies that after-school programs appear to have positive impacts on participants, but the included studies lacked the type of research designs and information to allow for making causal inferences. Roth, Malone, and Brooks-Gunn (Roth et al. 2010) reviewed the extent to which the amount of participation impacts outcome levels across 35 programs. The review found little support that increased participation resulted in improved academic and behavior outcomes, but it did find after-school participation levels to decrease with age and more frequent attendees to have improved school attendance outcomes. (Apsler 2009) literature review of after-school programs examined the quality of after-school program research; the review found serious methodological flaws, such as inappropriate comparison groups, sporadic participant attendance, and high attrition, which limited conclusions that could be drawn from the included studies.

Three reviews (Fashola 1998; Hollister 2003; Lauer et al. 2006) examined the impact of after-school programs on outcomes for at-risk youth. (Fashola 1998) review across 34 studies inspected the effectiveness of programs and ease of replicability, again citing the need for more rigorous study designs to increase confidence in after-school program effectiveness. The review suggested multiple program components to increase program effectiveness. For the delivery of academic components, Fashola suggested the alignment of program curriculum with in-school curricula and for the lessons to be taught by qualified instructors, such as school teachers. Fashola also suggested the use of recreational and cultural components to enhance a variety of skills for children. Proper implementation of programs included staff training, structure, and constant evaluation. (Hollister 2003) review of after-school programs examined their impact on academic and risky behavior. Among the ten studies with more rigorous methodologies, some programs were found to be effective. Finally, (Lauer et al. 2006) review focused on the impact of out-of-school programs, including activities occurring during summer, before-school, and after-school, on the reading and math skills of at-risk youth. The review found small but significant impact on both reading and math achievement across studies, with those using one-on-one tutoring to have larger effect sizes. The review did not find a difference in impact associated with when the activity occurred.

Prior reviews of after-school programs have contributed to our understanding of after-school program research, but many are older reviews, have different foci, and are limited by the methods used to conduct and synthesize findings. This review aimed to extend and improve upon prior reviews in several ways. First, prior reviews have ranged in quality and methods employed to conduct the reviews. Many prior reviews were not transparent in their inclusion criteria (Fashola 1998; Hollister 2003; Simpkins et al. 2004; Apsler 2009) and lacked systematic searching (Fashola 1998; Scott-Little et al. 2002; Hollister 2003; Simpkins et al. 2004; Apsler 2009) and data extraction methods (Fashola 1998; Hollister 2003; Simpkins et al. 2004; Apsler 2009; Roth et al. 2010). The use of rigorous and transparent methods is equally important in research synthesis as it is for the conduct of primary research to produce reviews that minimize errors, mitigate bias in the review process, and reduce chance effects, leading to more valid and reliable results than traditional narrative reviews (Cooper and Hedges 1994; Pigott 2012). Literature reviews that do not rely on systematic and transparent methods for the search and selection of studies can result in a biased sample of included studies (Littell et al. 2008). Traditional reviews tend to rely on a haphazard process for searching and selecting studies, use of convenience samples that may have been cherry-picked by authors that confirm authors’ theories and biases, and could be biased due to other psychological and superficial factors that affect the review process (Cooper and Hedges 1994; Bushman and Wells 2001). Moreover, extraction of data from primary studies is difficult, and errors are common (Gozsche et al. 2007). Therefore, it is highly recommended that at least two reviewers extract data from studies to reduce errors in the process (Buscemi et al. 2006; Campbell Collaboration, 2014). Moreover, authors of traditional reviews rarely report the methods used to conduct the review; thus, it is not possible to duplicate the study or adequately assess the quality of the review and the reliability or validity of the findings. The aim of using systematic review methods is to increase the objectivity and transparency in conducting reviews, to find all studies that meet explicit criteria established a priori to reduce the risk of selection bias, and to employ explicit processes for coding included studies to reduce error and increase the reliability and validity of the results. This review aimed to improve upon prior reviews by employing systematic review methodology and using rigorous conduct and reporting standards established by the Campbell Collaboration (2014) to overcome important limitations found in many of the prior reviews.

In addition to the importance of conducting reviews using rigorous methods, assessing risk of bias of included studies is important to the validity of the results and the interpretation of the review findings. Only one prior review (Zief et al. 2006) systematically assessed study quality or risk of bias of the included studies. A synthesis of weak studies fraught with threats to internal validity will limit the extent to which one can use the findings to draw conclusions related to the effects of an intervention (Higgins et al. 2011). Selection bias, in particular, can lead to biased estimates of effects, yet few reviews attempted to mitigate this risk. Selection bias results from systematic differences between groups at the outset of a study and has been identified as a significant threat to the internal validity of after-school program intervention studies (Scott-Little et al. 2002; Hollister 2003; Apsler 2009). To reduce the risk of selection bias and ensure inclusion of studies meeting a minimal level of criteria for internal validity, systematic reviews and meta-analyses often exclude studies that do not employ experimental or quasi-experimental designs. Across previous reviews of after-school programs, two of the prior reviews required that included studies use a randomized experimental design (Hollister 2003; Zief et al. 2006). Three reviews required studies to use a comparison group; however, these reviews did not require that studies establish pre-test equivalence or control for pre-test differences (Scott-Little et al. 2002; Lauer et al. 2006; Durlak et al. 2010). Two of the prior reviews did not require the use of a comparison group (Fashola 1998; Simpkins et al. 2004), and two reviews did not report study design inclusion criteria (Apsler 2009; Roth et al. 2010).

Most prior reviews have also been limited to a narrative approach or have used a vote-counting method to synthesize included studies. Narrative reviews of research may have been appropriate when few studies were available; however, it becomes increasingly difficult to synthesize a vast amount of data narratively when there are more than a few studies (Glass et al. 1981). (Glass et al. 1981) suggest that “the findings of multiple studies should be regarded as a complex data set, no more comprehensible without statistical analysis than would be hundreds of data points in one study” (Glass et al. 1981, p. 12). Vote counting methods make determinations about whether an intervention was effective by counting the number of studies that report positive results, negative results, and null results. The vote counting method disregards sample size, relies on statistical significance, and does not take into account measures of the strength of the study findings, thus potentially leading to erroneous conclusions (Glass et al. 1981). Alternatively, meta-analysis represents program impacts in terms of effect size, rather than statistical significance, and provides information about the strength and importance of a relationship and the magnitude of the effects of the interventions. This review synthesizes outcomes using an advanced meta-analytic technique, robust variance estimation, to reduce bias and more precisely examine effects and differences between studies with more statistical power than examining studies individually (Hedges et al. 2010).

Finally, prior reviews of after-school programs are somewhat dated. The searches for studies in the two most recently published reviews were conducted seven years ago in 2007 (Durlak et al. 2010; Roth et al. 2010). A number of studies have been conducted since 2007; thus, it seems timely for an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of after-school programs to examine the extent to which the outcome research has advanced and the effects of after-school programs using contemporary studies and techniques.

Purpose of the Present Study

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to synthesize the available evidence on the effects of after-school programs with at-risk primary and secondary students on school attendance and externalizing behavior outcomes. While federal and state funding typically require an emphasis on academic outcomes for after-school programs, non-academic objectives are prevalent across programs and may be an under-emphasized consideration for youth development. Given the negative outcomes associated with at-risk students and the potential for after-school programs to serve this population disproportionately, this systematic review and meta-analysis specifically focused on after-school programs targeted toward at-risk students. This purpose of this review was to examine the effects of after-school programs on school attendance and externalizing behavioral outcomes with at-risk students. Additionally, we examined whether study, participant, or program characteristics were associated with the magnitude of effect of after-school programs.

Materials and Methods

Systematic review methodology was used for all aspects of the search, selection, and coding of studies. Meta-analysis was used to synthesize the effects of interventions quantitatively, and moderator analysis was conducted to examine potential moderating variables. We followed the Campbell Collaboration standards for the conduct of systematic reviews of interventions (Campbell Collaboration, 2014). The protocol and data extraction form developed a priori for this review are available from the authors.

Study Eligibility Criteria

Experimental and quasi-experimental studies examining the effects of an after-school program on school attendance or externalizing behaviors with at-risk primary or secondary students were included in this review. Studies must have used a comparison group (wait-list or no intervention, treatment as usual, or alternative interventions) and reported baseline measures of outcome variables or covariate adjusted posttest means to be included. Externalizing behavior outcomes were broadly defined as any acting out or problematic behavior, including but not limited to disruptive behavior, substance use, or delinquency. Student-, parent-, or teacher report measures and administrative school and court data were eligible for inclusion in this review.

Interventions included in this review were after-school programs defined as an organized program supervised by adults that occurred during after-school hours during the regular school year. To distinguish after-school programs from other content-specific or sports related extra-curricular activities, an after-school program must have offered more than one activity. This definition maintains consistency with criteria established by twentyfirst Century Community Learning Centers, which describes centers as helping students meet academic standards in math and reading while also offering “a broad array of enrichment activities that can complement their regular academic programs” (U.S. Department of Education 2014). The inclusion of programs offering more than one activity was also utilized in the review conducted by (Roth et al. 2010). Interventions that operated solely during the summer or occurred during school hours were excluded from this review. Interventions that were solely mentoring or tutoring were also excluded from this review as those types of programs, while often occurring after school, are not generally classified as an after-school program and have been synthesized as separate types of interventions (Ritter et al. 2009; DuBois et al. 2011; Tolan et al. 2013). If mentoring or tutoring was provided in addition to other activities and the study also met the other inclusion criteria, the study was included in the review. Study participants were children or youth in grades K-12 who were considered “at-risk” if meeting one of the following criteria: (1) performing below grade level or having low scores on academic achievement tests; (2) attending a low-performing or Title I school; (3) having characteristics associated with risk for lower academic achievement, such as low socioeconomic status, racial- or ethnic-minority background, single-parent family, limited English proficiency, or a victim of abuse or neglect; or (4) engaging in high-risk behavior, such as truancy, running away, substance use, or delinquency (adapted from Lauer et al. 2006). To be considered at-risk, at least 50 % of the participants in the sample must have met the at-risk criteria. Due to significant differences in educational systems around the world, this review was limited to studies conducted in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Ireland, and Australia.

Information Sources

Several sources were used to identify eligible published and unpublished studies between 1980 and May, 2014. Eight electronic databases were searched: Academic Search Premier, ERIC, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, PsychI-NFO, Social Sciences Citation Index, Social Services Abstracts, Social Work Abstracts, and Sociological Abstracts. Keyword searches within each electronic database included variations of “after-school program” and (evaluation OR treatment OR intervention OR outcome) to narrow the search field to evaluations of after-school programs. Electronic searches were originally conducted in 2012 and then updated in May 2014. The full search strategy for each electronic database is available in Online Resource 1 and from the authors. Potential reports were also sought by searching the following registers and internet sites: Harvard Family Research Project, National Center for School Engagement, National Dropout Prevention Center, National Institute on Out-of-School Time, OJJDP Model Programs Guide, and What Works Clearinghouse. Additionally, reference lists of prior reviews and articles identified during the search were hand-searched and experts were contacted via email for potentially relevant published and unpublished reports.

The inclusion of unpublished literature, in particular, is important to limit the risk of publication bias, “which refers to the tendency for studies lacking statistically significant effects to go unpublished” (Pigott et al. 2013, p. 1). Publication bias may be the result of journals choosing not to publish papers with non-significant primary outcomes (Hopewell et al. 2009) or study authors choosing not to submit the study for publication (Cooper et al. 1997). As found by (Pigott 2012) in a comparison of dissertations to their later published versions, non-significant outcomes were 30 % less likely to be in the published versions. Additionally, a review by (Hopewell et al. 2009) found studies with positive results to be published more frequently and more quickly than studies with negative results. To limit the risk of publication bias, locating unpublished literature for inclusion in systematic review is a crucial component of the search strategy as outlined by the Campbell Collaboration (2014). Although unpublished studies, such as dissertations, have not gone through the formal peer-review process, unpublished and published research have been found to be of similar quality (McLeod and Weisz 2004; Hopewell et al. 2007; Moyer et al. 2010).

Study Selection and Data Extraction

Titles and abstracts of the studies found through the search procedures were screened for relevance by one author. If there was any question as to the appropriateness of the study at this stage, the full text document was obtained and screened. Documents that were potentially eligible or relevant based on the abstract review were retrieved in full text and screened by one author using a screening instrument. Following initial screening, potentially eligible studies were further reviewed by two authors to determine final inclusion. Any discrepancies between authors were discussed and resolved through consensus, and when needed, a third author reviewed the study.

Studies that met inclusion criteria were coded using a coding instrument comprised of five sections: (1) source descriptors and study context; (2) sample descriptors; (3) intervention descriptors; (4) research methods and quality descriptors; and (5) effect size data. The data extraction instrument, available from the authors, was pilot tested by two authors and adjustments to the coding form were made. Two authors then independently coded all data related to moderator variables (i.e., study design, grade level, contact frequency, control treatment, program type, and program focus) and data used to calculate effect size. Initial inter-rater agreement was 95 % for the coding of moderator variables and 98 % for effect size data. Discrepancies between the two coders were discussed and resolved through consensus. Descriptive data related to study, sample, and intervention characteristics were coded by one author, with 20 % of the studies coded by a second author. Inter-rater agreement on descriptive items was 92.3 %. If data were missing from a study, every effort was made to contact the study author to request the missing data. We contacted 22 authors requesting additional information. Four authors did not respond to our request. Eleven authors were unable to send additional information due to data availability or time constraints. Seven authors sent additional information. Data from four of these authors were utilized in the meta-analysis, while information from three authors was still insufficient for the study to be included in the review.

Assessing Risk of Bias

The extent to which one can draw conclusions about the effects of interventions from a review depends on the extent to which the results from the included studies are valid (Higgins et al. 2011). A review based on studies with low internal validity, or a group of studies that vary in terms of internal validity, may result in biased estimates of effects and misinterpretation of the findings. Therefore, it is critical to assess all included studies for threats to internal validity. To examine the risk of bias of included studies, two review authors independently rated each included study using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. The risk of bias tool addresses five categories of bias (i.e., selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias) assessed using a domain-based evaluation tool in which assessment of risk is made separately for each domain in each included study, namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other sources of bias. All studies included in the review were rated on each domain as low, high, or unclear risk of bias. Initial agreement between coders on the Risk of Bias tool was 81 %. Coders reviewed the coding agreement, and discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus.

As discussed previously, selection bias results from systematic differences between groups at the outset of a study. When participants are not randomly assigned to condition, or when randomization procedures are incorrectly employed or compromised, systematic differences between the treatment and control groups may be present prior to treatment, which could account for the study’s findings rather than the intervention. Selection bias is assessed in the risk of bias tool by examining the method used to generate allocation sequence (i.e., sequence generation) and the method used to conceal allocation (i.e., allocation concealment). Performance bias, or the extent to which groups are treated systematically different from one another apart from the intervention, and detection bias, systematic differences in the way participants are assessed, are other sources of bias that can threaten internal validity. This can occur, for example, when the researchers who developed the intervention provide extra attention or care to the treatment group, perhaps inadvertently, because they are invested in the treatment group performing better. Thus, the knowledge of which intervention was received, rather than the intervention itself, may affect the outcomes. Blinding participants and personnel to group assignment can mitigate performance and detection bias. In the risk of bias tool, we rated the extent of risk based on whether participants and personnel were blinded to group assignment. Attrition bias, missing data resulting from participants dropping out of the study or other systematic reasons for missing or excluded data, can also impact internal validity of a study. Participants who drop out of a study, or for whom data are not available or excluded, may be systematically different from participants who remain in the study, thus increasing the possibility that effect estimates are biased. Reporting bias was the final form of bias assessed in this review. Reporting bias can occur when authors selectively report the outcomes, either by not reporting all outcomes measured, or reporting only subgroups of participants. Because analyses with statistically significant differences are more likely to be reported than non-significant differences, effects may be upwardly biased if studies are selectively reporting outcomes.

Statistical Procedures

Several statistical procedures were conducted following recommendations of (Pigott 2012). To begin, we calculated the standardized-mean difference, correcting for small-sample bias using Hedges g (Pigott 2012) for each outcome included in the review. To control for pre-test difference between the intervention and control conditions, we subtracted the pre-test effect size from the post-test effect size (Lipsey and Wilson 2001). The variance was calculated for each effect size, adjusting for the number of effect sizes in the study (Hedges et al. 2010).

An advanced meta-analytic technique, robust variance estimation, was used to synthesize the effect sizes. Unlike traditional meta-analysis, robust variance estimation allows for the inclusion and synthesis of all estimated effect sizes simultaneously (Hedges et al. 2010; Tanner-Smith and Tipton 2013). For example, the included study by (Hirsch et al. 2011) presented effect size information for 10 related externalizing behaviors. Robust variance estimation models each of the effect sizes, eliminating the need to average or select only one effect size per study. The result of the analysis is random-effects weighted average, similar to traditional syntheses, but including all available information. Of note, we chose to conduct separate meta-analyses for the attendance and behavioral outcomes, given their divergent latent nature.

Finally, we estimated the heterogeneity and attempted to model it. (Higgins and Thompson 2002) suggested the calculation of I2, which quantifies the amount of heterogeneity beyond sample differences. A moderate to large amount of heterogeneity, enough to conduct moderator analyses, is between 50–70 %. Given sufficient heterogeneity, we conducted moderator analyses; we limited the quantity of such tests to decrease the probability of spurious results (Polanin and Pigott 2014). In total, we used seven a priori determined variables: age (i.e., elementary, middle, or mixed), amount of program contact (i.e., weekly, 3–4 per week, or daily), control group type (i.e., wait list, treatment as usual, or alternative intervention), study design (i.e., random or non-random), program type (i.e., National or other), program focus (i.e., academic, non-academic, or mixed), and publication status (i.e., published or unpublished). We used the R package robumeta (Fisher and Tipton 2014) to conduct all analyses.

Results

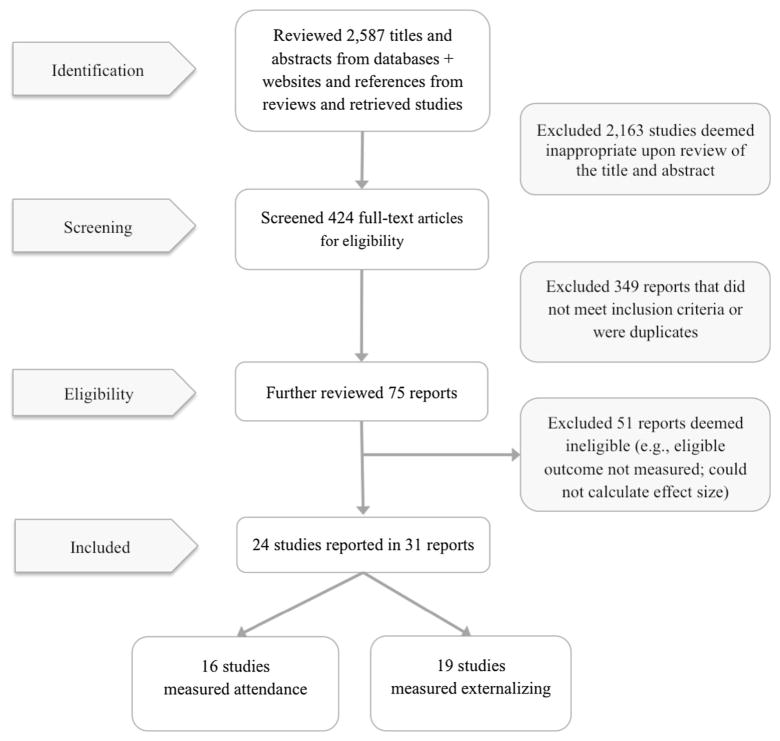

A total of 2,587 citations were retrieved from electronic searches of bibliographic databases, with additional citations reviewed from reference lists of prior reviews and studies and website searches. Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance and 2,163 were excluded due to being duplicates or deemed inappropriate. The full text of the remaining 424 reports was screened for eligibility, and 75 reports were further reviewed for final eligibility by two of the authors. Fifty-one reports were deemed ineligible, primarily due to not reporting an outcome of interest for this review (43 %), not reporting baseline data on the outcomes (24 %), not statistically controlling for pre-test differences between the treatment and control group (22 %), or not reporting enough data to calculate an effect size (20 %). Additional information on the excluded studies is available in Online Resource 2 and from the authors. Twenty-four studies reported in 31 reports were included in the review. Of the included studies, 16 studies with 16 effect sizes were included in the analysis of attendance outcomes, and 19 studies with 49 effect sizes were included in the analysis of externalizing behavior outcomes. See Fig. 1 for details regarding the search and selection process, and Table 1 for additional information regarding the included studies.

Fig. 1.

Study selection flow chart

Table 1.

Summary of included studies

| 1st Author (year) | Program name | At-risk identifier | Program type |

Program focus |

Weekly contacta |

N | Grade levelb |

Study designc |

Outcomes | Inclusion in past reviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arcaira et al. 2010 | Citizen schools | High minority, low-income | National | Academic | Not specified | 870 | 2 | QED | EB: Suspensions; AT: Attendance | None |

| Biggart et al. 2013 | Doodle Den | Low reading proficiency | Local | Academic | 4 | 621 | 1 | RCT | EB: Teacher reported ADHD Scale | None |

| Blumer and Werner-Wilson 2010 | Pathways | History of high-risk behavior, high minority | Local | Non academic | 4 | 37 | 4 | QED | EB: CAFAS | None |

| Foley and Eddins 2001 | Virtual Y | High % low income and minority | Local | Mixed | Not specified | 5,915 | 1 | QED | AT: Grade 4 attendance | Durlak et al. |

| Frazier et al. 2013 | Project NAFASI | High % minority and low income | Local | Non academic | 5 | 127 | 4 | QED | EB: Aggression | None |

| Gottfredson et al. 2010a | All Stars | High % minority | Local | Non academic | 4 | 447 | 2 | RCT | EB: Last month drug use, disruptive behavior, aggression, delinquency | None |

| Gottfredson et al. 2004 | Maryland after school community Grant | High % minority | Local | Non academic | 4 | 349 | 4 | QED | EB: Delinquency, rebellious, drug use | Durlak et al. |

| Hirsch et al. 2011 | After school matters | High % minority and low income | Local | Mixed | 4 | 535 | 3 | RCT | EB: Alcohol, drug use, risky intercourse, steal < $50, Steal > $50, suspension, sell drugs, carry weapon, fights gang activity; AT: attendance | None |

| James-Burdumy et al. 2005, 2007, 2008 | twentyfirst century community learning center | High % Minority | National | Not specified | 5 | 2,288 | 1 | RCT | EB: Suspensions; AT: Absences | Apsler Durlak et al. Roth et al. |

| James-Burdumy et al. 2005, 2008 | twentyfirst century community learning centers | High % Minority | National | Not specified | 4 | 3,831 | 2 | QED | EB: Student-reported disciplinary referrals, teacher reported discipline; AT: Absences | Apsler Durlak et al. Roth et al. |

| LaFrance et al. 2001 | Safe haven | High % minority and history of arrest | Local | Mixed | 5 | 241 | 4 | QED | AT: Attendance | None |

| Langberg et al. 2007 | Challenging Horizons | Low academic achievement | Local | Academic | 4 | 48 | 2 | RCT | EB: Parent CGI; Parent IRS; Teacher IRS | None |

| Le et al. 2011 | Roosevelt village center | High % minority | Local | Mixed | 5 | 338 | 2 | QED | EB: Truancy; delinquency; arrest | None |

| Molina et al. 2008 | Challenging horizons | ADHD diagnosis | Local | Non academic | 3 | 20 | 2 | RCT | EB: Parent-externalizing; Adolescent- delinquency, maladjustment | None |

| Nguyen 2007 | twentyfirst century community learning centers | Low academic achievement | National | Mixed | 4 | 28,169 | 4 | QED | EB: Disciplinary referrals, suspensions; AT: Absences | None |

| Oyserman et al. 2002 | School to Jobs | High % minority and low-income | Local | Non academic | 2 | 206 | 2 | QED | EB: Self-report referrals; AT: Attendance | Durlak et al. |

| Pastchal-Temple 2012 | twentyfirst century community learning centers | Low-income | National | Mixed | 3 | 66 | 2 | QED | EB: Disciplinary referrals; AT: Absences | None |

| Prenovost 2001 | After school learning and safe neighborhoods Partnership | High % minority, low-income, LEPd | Local | Mixed | 5 | 1,358 | 2 | QED | AT: Absences | Durlak et al. Lauer et al. Roth et al. |

| Schinke et al. 2000 | Boys and girls club | Low-income | National | Mixed | 5 | 188 | 4 | QED | EB: Behavioral incidences; AT: attendance | None |

| Sibley-Butler 2004 | Twentyfirst century Community learning centers | High % low-income and minority | National | Not specified | Not specified | 78 | 1 | QED | EB: Discipline referrals; AT: Attendance | None |

| Smeallie 1997 | Tutorial club | High % minority, academic failure | Local | Mixed | 3 | 62 | 2 | RCT | AT: Attendance | Lauer et al. |

| Tebes et al. 2007 | Positive youth Development collaborative | High % minority | Local | Non academic | Not specified | 304 | 4 | QED | EB: Alcohol, marijuana, other drug use | Durlak et al. |

| Weisman et al. 2003 | Maryland after school community Grant | High % minority | Local | Mixed | 4 | 1,068 | 4 | QED | EB: Rebellious behavior; delinquency; drug use; AT: days absent | Durlak et al. Zief et al. |

| Welsh et al. 2002 | The After school corporation | High % minority and low-income | Local | Not specified | 5 | 68,214 | 4 | QED | AT: Attendance | Lauer et al. Scott-Little et al. |

Weekly contact: 1 = less than weekly; 2 = weekly; 3 = 2 times per week; 4 = 3–4 times per week; 5 = 5 times per week

Grade level: 1 = elementary; 2 = middle; 3 = high; 4 = mix

QED quasi-experimental design, RCT randomized controlled trial

LEP limited english proficiency

Characteristics of Included Studies and Programs

Design

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. Seven of the studies were randomized controlled designs, while the majority (70.8 %) were quasi-experimental designs. Although the search was open to studies published as early as 1980, the majority of studies were published either between 2000 and 2009 (62.5 %) or 2010 and 2014 (33.3 %). Only one study published prior to 2000 was included in the review. While additional studies published between 1980 and 2000 met our inclusion criteria, many of these studies either lacked statistical controls or sufficient data to calculate effect sizes. Despite efforts to search for studies conducted in a broad geographical area, nearly all of the included studies (95.8 %) were conducted in the United States, with one study conducted in Ireland. The comparison condition for the majority (70.8 %) of the studies was no treatment or waitlist. Four of the studies compared the treatment condition to a comparison group that received another specific treatment, which included individual therapy (Blumer and Werner-Wilson 2010), Boys & Girls Clubs without enhanced educational activities (Schinke et al. 2000), an after-school program held at a local park without increased support for staff (Frazier et al. 2013), and an after-school program providing academic support and recreational activities (Tebes et al. 2007). Of the 24 studies included in this meta-analysis, nearly half (45.8 %) were found in the grey literature. The unpublished studies included five dissertations, theses, or Master’s research papers, one governmental report, and five reports published by non-governmental agencies. Sample sizes of the included studies varied, ranging from 20 to nearly 70,000 participants.

Table 2.

Study and sample characteristics

| Characteristic | N (%) | Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publication year | Mean agea | 11.7 | |

| 1990–1999 | 1 (4.2) | Free or reduced lunchb | 78.4 |

| 2000–2009 | 15 (62.5) | Percent malec | 52.5 |

| 2010–2014 | 8 (33.3) | Predominant race | |

| Grade level | Caucasian | 4 (16.7) | |

| Elementary | 4 (16.7) | African American | 11 (45.8) |

| Middle school | 10 (41.7) | Hispanic | 1 (4.2) |

| High school | 1 (4.2) | Asian | 1 (4.2) |

| Mixed | 9 (37.5) | Not reported | 7 (29.2) |

| Control group condition | Research design type | ||

| Nothing or waitlist | 17 (70.8) | Randomized controlled | 7 (29.2) |

| Treatment as usual | 3 (12.5) | Quasi-experimental | 17 (70.8) |

| Alternative treatment | 4 (16.7) | Publication type | |

| Sample size | Journal | 13 (54.2) | |

| 1–150 | 7 (29.2) | Dissertation or thesis | 5 (20.8) |

| 151–300 | 3 (12.5) | Government report | 1 (4.2) |

| 301–600 | 5 (20.8) | Other report | 5 (20.8) |

| 601 and greater | 9 (37.5) | Country | |

| At-risk identifierd | United States | 23 (95.8) | |

| Low-income | 10 (41.7) | Ireland | 1 (4.2) |

| High minority | 18 (75.0) | Australia | 0 (0.0) |

| Low-academic achievement | 4 (16.7) | Canada | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 4 (16.7) | United Kingdom | 0 (0.0) |

Reported in 12 studies

Reported in 10 studies

Reported in 22 studies

Categories not mutually exclusive

Participants

A total of 109,282 students participated in the studies. Included programs primarily targeted students in either middle school (41.7 %) or a mixture of grade levels (37.5 %). Although less than half of the studies reported the socio-economic status of participants, the studies reporting this characteristic showed that participants were overwhelmingly low-income. African American participants were the predominant race in 45.8 % of the studies. The samples were nearly evenly split between genders. Interventions were targeted toward participants who met one of the aforementioned criteria for at-risk. Across the studies, identifiers for an at-risk population included 75 % of studies comprised of high proportion ethnic or racial minority background, 42 % of studies with a high proportion of low-income households, and 17 % of studies comprised of students with low academic achievement. Four other studies were classified as at-risk for targeting students with a history of high risky behavior, history of arrest, ADHD diagnosis, and Limited English Proficiency. While studies classified as “high” in a risk category must have had at minimum 50 % of the participants falling within that category, the majority of studies met their at-risk identifier with a high proportion of the population. For example, studies with a high percent of students from an ethnic or racial minority background had samples wherein the percent of students who were non-white ranged from 70 to 100 %. For studies with a high percent of low-income students, the percent of students who were eligible for free or reduced lunch ranged from 85 to 100 % of participants. Although programs were limited to those targeting at-risk participants, no studies were excluded solely based on this criterion. Programs that did not target at-risk youth also failed to meet a number of other inclusion criteria.

Interventions

Table 3 summarizes the characteristics of the interventions for the included studies. Half (54.2 %) of the interventions were held in a school setting, with an additional 20.8 % of studies operated at a community-based organization. The remaining studies were either in a mixed setting (12.5 %) or it was not possible to determine the setting (12.5 %). While some interventions (12.5 %) were comprised entirely of academic components, the majority of interventions included either a mixture of academic and non-academic components (41.7 %) or all non-academic components (29.2 %). Although interventions were limited to those utilizing more than one activity, no studies were excluded solely based on this criteria. Interventions that did not use more than one activity also failed to meet a number of other inclusion criteria. Roughly half of the interventions followed a manual to implement either the entire program (29.2 %) or a portion of the treatment (25.0 %). The majority of the interventions were conducted locally (70.8 %), while the remaining interventions (29.2 %) were national programs. The interventions had considerable variety in the dosage and frequency of treatment. The mean number of treatment sessions was 116, with interventions most frequently meeting 3–4 (37.5 %) or 5 days (33.3 %) per week. The majority of treatment sessions lasted 3–3.59 h (41.7 %) per session.

Table 3.

Intervention characteristics

| Characteristic | N (%) | Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Settings | Number of treatment sessions | ||

| School | 13 (54.2) | 0–50 | 3 (12.5) |

| Community-based organization | 5 (20.8) | 51–100 | 3 (12.5) |

| Mixed | 3 (12.5) | 101–150 | 7 (29.2) |

| Unsure | 3 (12.5) | 151 and greater | 4 (16.7) |

| Program focus | Unsure | 7 (29.2) | |

| Academic | 3 (12.5) | Length of sessions | |

| Non-academic | 7 (29.2) | 1–1.59 h | 4 (16.7) |

| Mixed | 10 (41.7) | 2–2.59 h | 4 (16.7) |

| Unsure | 4 (16.7) | 3–3.59 h | 10 (41.7) |

| Manual used for intervention | 4 h and greater | 3 (12.5) | |

| No | 10 (41.7) | Unsure | 3 (12.5) |

| Yes, for entire program | 7 (29.2) | Weekly contact frequency | |

| Yes, for partial treatment | 6 (25.0) | Once | 1 (4.2) |

| Unsure | 1 (4.2) | Twice | 2 (8.3) |

| Program coverage | Three to Four | 9 (37.5) | |

| National | 7 (29.2) | Five | 8 (33.3) |

| Local | 17 (70.8) | Unsure | 4 (16.7) |

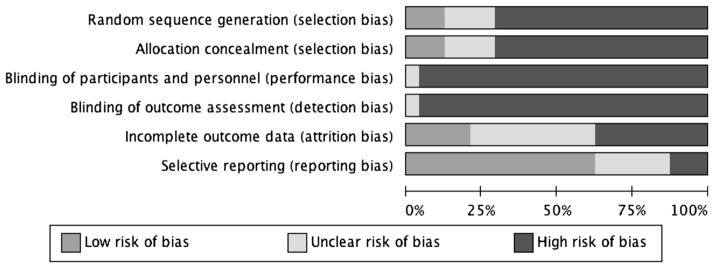

Risk of Bias of Included Studies

Overall, there was a high risk of bias across the included studies (see Fig. 2). Selection bias was rated as high risk in 17 (71 %) of the included studies, uncertain in four of the included studies, and low risk in two of the included studies. Only seven (29 %) of the included studies used randomization to assign students to the after-school program or control condition, with only three of these seven studies providing a clear description of their randomization procedure and only three providing information related to allocation concealment.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias across studies

In terms of performance and selection bias, only one study reported the use of blinding of participants or personnel and outcome assessment. Attrition bias was assessed as high risk in nine (38 %) of the included studies. These studies reported either high overall or differential attrition and did not use a missing data strategy; thus, the results may be biased and reflect differences between groups based on participant characteristics associated with dropping out of the study rather than the effects of the intervention. Three studies were assessed as low risk of attrition bias as they reported either low or no overall or differential attrition or used missing data strategies to perform the analysis with data from all participants assigned to condition. The remaining 10 studies were assessed as unclear risk as the studies did not clearly indicate the procedures used for the management of attrition or the attrition rates could not be reliably calculated. We assessed most studies (63 %) as low risk for reporting bias as the authors appeared to have reported the expected outcomes, three studies as high risk as there appeared to be selective or incomplete reporting of expected outcomes, and six studies as unclear risk of reporting bias. Risk of bias by study is found in Table 4.

Table 4.

Risk of bias summary table

| First Author (year) | Selection bias (randomization) | Selection bias (allocation) | Performance bias | Detection bias | Attrition bias | Reporting bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arcaira et al. 2010 | H | H | H | H | H | L |

| Biggart et al. 2013 | U | U | H | H | H | L |

| Blumer and Werner-Wilson 2010 | H | H | U | U | U | H |

| Foley and Eddins 2001 | H | H | H | H | H | H |

| Frazier et al. 2013 | H | H | H | H | U | L |

| Gottfredson et al. 2004 | H | H | H | H | H | L |

| Gottfredson et al. 2010a* | U | U | H | H | L | L |

| Hirsch et al. 2011 | L | L | H | H | H | U |

| James-Burdumy et al. 2005-elementary* | U | L | H | H | L | L |

| James-Burdumy et al. 2005-middle* | H | H | H | H | U | H |

| LaFrance et al. 2001 | H | H | H | H | U | U |

| Langberg et al. 2007 | L | L | H | H | U | L |

| Le et al. 2011 | H | H | H | H | U | L |

| Molina et al. 2008 | U | U | H | H | H | U |

| Nguyen 2007 | H | H | H | H | U | U |

| Oyserman et al. 2002 | H | H | H | H | U | U |

| Pastchal-Temple 2012 | H | H | H | H | L | L |

| Prenovost 2001 | H | H | H | H | L | L |

| Schinke et al. 2000 | H | H | H | H | L | L |

| Sibley-Butler 2004 | H | H | H | H | U | L |

| Smeallie 1997 | L | U | H | H | H | L |

| Tebes et al. 2007 | H | H | H | H | H | L |

| Weisman et al. 2003 | H | H | H | H | H | L |

| Welsh et al. 2002* | H | H | H | H | U | U |

H high risk of bias, L low risk of bias, U unclear risk of bias

Indicates multiple reports per study

Effects of Interventions

Attendance

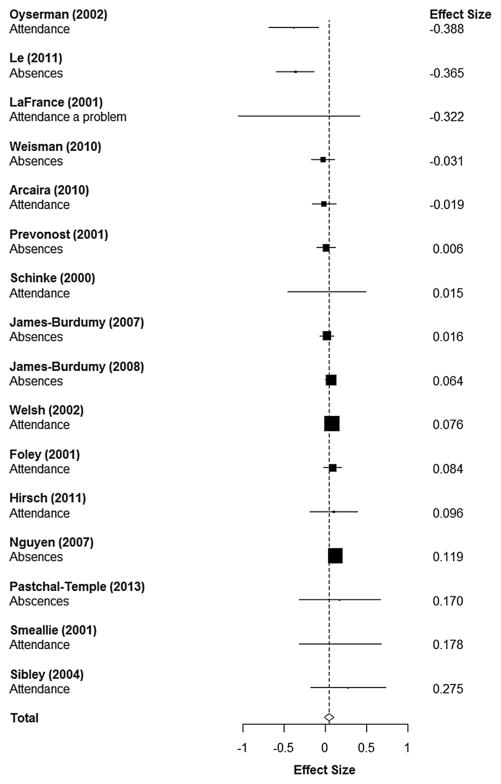

A total of 16 studies, including 16 effect sizes, were synthesized to capture the effects of the interventions on students’ attendance. Figure 3 depicts a forest plot of the effect sizes for attendance outcomes. Half of the studies used a measure of total attendance in school, while the other half assessed the number of absences from school. We transformed the effect sizes so that a positive effect size indicated greater attendance. The results of the synthesis indicated a very small, non-statistically significant treatment effect (g = 0.04, 95 % CI −0.02, 0.10). The homogeneity analysis indicated a moderate degree of heterogeneity (τ2 = .002, I2 = 66.67 %). Given sufficient heterogeneity, we conducted a series of moderator analyses. Only five analyses were conducted because the focus variable did not include sufficient variability (i.e., all but one study used a mixed approach). As presented in Table 5, the results of the moderator analyses did not reveal significant differences (p > .05).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot for attendance effect sizes

Table 5.

Moderator analyses

| Moderator | Attendance

|

Behavior

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | ES (SE) | 95 % CI | k | ES (SE) | 95 % CI | |

| Age | ||||||

| Elementary | 3 | .06 (.04) | −.27, .38 | 3 | .07 (.12) | −.47, .62 |

| Middle | 7 | −.02 (.06) | −.20, .17 | 17 | .14 (.06) | −.01, .30 |

| Mixed | 5 | .07 (.03) | −.06, .21 | 19 | .15 (.26) | −.52, .83 |

| Contact | ||||||

| Weekly | 2 | −.22 (.26) | −3.49, 3.05 | 4 | .25 (.11) | −1.17, 1.67 |

| 3–4x/Week | 4 | .07 (.04) | −.06, .20 | 26 | .02 (.06) | −.13, .17 |

| Daily | 7 | −.01 (.05) | −.15, .15 | 13 | .21 (.26) | −.54, .95 |

| Control type | ||||||

| Wait list | 13 | .01 (.03) | −.05, .08 | 27 | .07 (.04) | −.04, .16 |

| TAU | 2 | .06 (.11) | −.15, .27 | 13 | .81 (.67) | −2.92, 1.77 |

| Alternative | 8 | −.19 (.37) | −2.16, 1.79 | |||

| Design | ||||||

| Random | 3 | .04 (.04) | −.30, .37 | 22 | .07 (.09) | −.23, .36 |

| Non-random | 13 | .04 (.03) | −.03, .11 | 27 | .14 (.11) | −.10, .38 |

| Program type | ||||||

| Local/regional | 9 | −.01 (.05) | −.14, .12 | 40 | .04 (.07) | −.11, .19 |

| National | 7 | .06 (.03) | −.02, .14 | 9 | .19 (.15) | −.19, .56 |

| Focus | ||||||

| Academic | 5 | .20 (.07) | −.40, .75 | |||

| Non-academic | 11 | −.04 (.26) | −1.04, .97 | |||

| Mixed | 32 | .11 (.12) | −.16, .38 | |||

| Publication | ||||||

| Published | 6 | .08 (.02) | .02, .14 | 34 | .14 (.06) | −.04, .32 |

| Unpublished | 10 | −.10 (.06) | −.24, .05 | 15 | .12 (.12) | −.15, .39 |

k Number of effect sizes, Focus moderator eliminated from the analysis for attendance outcomes due to missingness

TAU Treatment as usual, None of the moderator analyses revealed significant differences (p < .05)

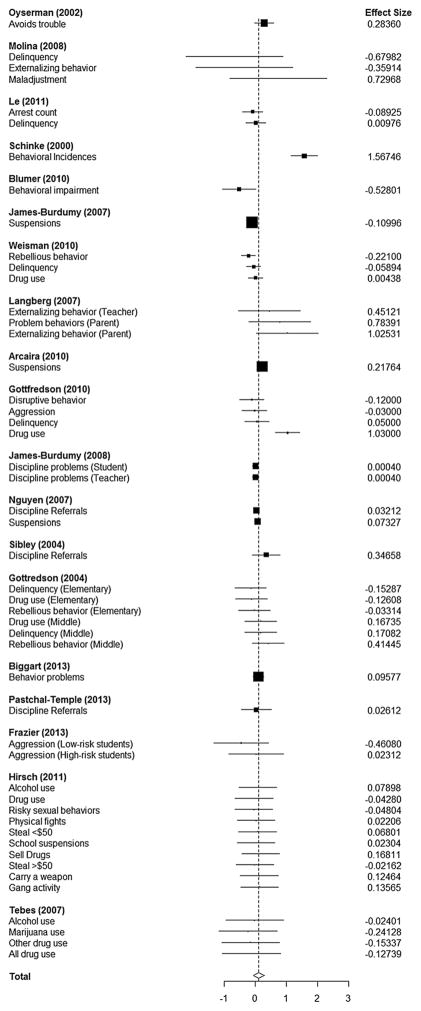

Externalizing Behaviors

Sixteen studies, including 49 effect sizes, were synthesized to capture effects of interventions on externalizing behavior (mean n of effect sizes = 2.58, Min = 1, Max = 10). Figure 4 depicts a forest plot of the effect sizes for externalizing behavior outcomes. The majority of externalizing behaviors included in this review were self-reported (65 %). Additional reporters included teachers (6 %), program staff (6 %), and parents (6 %). School administrative data were also utilized for the collection of 14 % of externalizing behavior outcomes. The reporter for one externalizing behavior outcome was unknown. Most of the effect sizes measured disruptive behavior or delinquency (n = 39, 79.6 %) and the rest measured substance use (n = 10, 20.4 %). We chose to pool all measures of externalizing behaviors rather than separate drug or alcohol usage from other externalizing behaviors to allow for greater statistical power and because moderator analysis indicated no significant differences in effects of interventions between substance use and other externalizing behavior outcomes (t = 0.84, p = 0.47). All effect sizes were transformed so that a positive effect size indicated a positive treatment effect (i.e., reduction in problematic behavior). The results of the meta-analysis indicated a small, non-significant effect (g = 0.11, 95 % CI −0.05, 0.28). The homogeneity analysis indicated a high degree of heterogeneity (τ2 = .03, I2 = 79.74 %). As such, we conducted moderator analyses using all seven variables. Results of the moderator analyses did not reveal significant differences (p > .05; see Table 5).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot for externalizing behavior effect sizes

Discussion

Despite the popularity of after-school programs and the substantial resources being funneled into after-school programs across the United States, surprisingly few rigorous evaluations have been conducted to examine effects of after-school programs on behavior and school attendance outcomes. A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to quantify and synthesize the effects of after-school programs on externalizing behavior and school attendance and to provide an up-to-date review of a growing research base. A comprehensive search for published and unpublished literature resulted in the inclusion of 24 after-school program intervention studies, 14 of which have not been included in prior reviews. Sixteen of the included studies measured school attendance, and 19 studies measured externalizing behaviors. Overall, the after-school programs included in this review were found to have small and non-significant effects on externalizing behavior and school attendance outcomes. On average, students participating in after-school programs did not demonstrate improved behavior or school attendance compared to their comparison group peers. These results contradict (Durlak et al. 2010) findings of significant effects on problem behaviors [ES 0.19, CI (0.10, 0.27)], but corroborate Durlak and colleagues’ findings of non-significant effects on drug use and school attendance, and (Zief et al. 2006) findings of no effects on behavior and school attendance. Prior narrative reviews have reported promising but tentative conclusions about the effects of after-school programs on behavior (Redd et al. 2002; Scott-Little et al. 2002), while also stating that further research was needed.

For school attendance, the evidence from this review converges with prior quantitative and narrative reviews. Simply, after-school programs have not demonstrated significant effects on school attendance (Zief et al. 2006; Durlak et al. 2010). Although 16 studies in the current review measured school attendance, few specified increasing school attendance as a primary goal of the after-school program or explicated a theory of change connecting the mechanisms of the after-school program to school attendance. For those that did describe a theory of change linking after-school program characteristics with school attendance outcomes, mechanisms identified included increasing youth’s sense of belonging and perception of the instrumental value of education (Hirsch et al. 2011), while also increasing youth’s sense of their own vision of their future and creating a more explicit academic self, connecting current action and future goals, and giving youth practice and skills needed to engage and put forth effort in school (which includes attendance; Oyserman et al. 2002). If school attendance truly is a goal of after-school programs, then it is important for after-school programs to state that explicitly as a goal and develop their programs to affect school attendance using a theory of change to drive program elements that would likely impact school attendance outcomes. Simply implementing an after-school program with hopes that it will have positive impacts on a number of outcomes without building in specific mechanisms to impact those outcomes is likely to fail.

Similar to findings related to effects on attendance, the present review’s findings point to non-statistically significant effects of after-school programs on externalizing behavior. Although the present results support findings of (Zief et al. 2006) review, the conclusions offered by other prior reviews regarding the effects of after-school programs on behavioral outcomes have been more positive (Scott-Little et al. 2002; Durlak et al. 2010). The contrast between our findings and the more positive findings from prior reviews likely stems from several factors. We included substance use measures in the construct of externalizing behaviors whereas (Durlak et al. 2010) separated substance use, for which they found no significant effect, from other externalizing behaviors. Also, Durlak and colleagues estimated an effect size of zero for all outcomes when the primary study authors reported the result as non-significant and did not report enough data to calculate a true effect size. Imputing a single value for an effect size may lead to biased results and is only adequate for rejecting the null hypothesis (Lipsey and Wilson 2001). Imputing zero for studies that report non-significant results is not recommended as it artificially decreases the variability of the variables. Underestimating the variance is particularly problematic for answering questions related to magnitude of the mean effect, moderators of effects, and heterogeneity of studies (Pigott 1994). Durlak and colleagues, furthermore, did not adjust for pre-test differences in all cases and did not require that studies control for pre-test differences or demonstrate pre-test equivalence. This is problematic because, although all included studies in Durlak et al.’s review used a comparison group, 65 % of the included studies were quasi-experiments and thus potentially suffered from selection bias. Without adjusting for baseline differences, the effects could be over- or under-estimated. Any of these procedures could have resulted in a bias of the effect size estimates and could explain the difference in the meta-analytic results between the two reviews. Finally, the current review included different studies than the Durlak review based on slightly different inclusion criteria and more recent search for studies.

Unlike attendance outcomes, more attention has been paid to empirical evidence of youth development and delinquency and theories of change connecting after-school programs to externalizing behavior outcomes. Gottfredson, Cross, and colleagues discussed routine activity theory and social control theory in their after-school program intervention studies (see Cross et al. 2009; Gottfredson et al. 2007, 2010b, 2010c, 2004). By providing adult supervision and structured activities, after-school programs have the potential to reduce delinquency (Cross et al. 2009, p. 394). (Cross et al. 2009) noted, however, that the potential for after-school programs to impact externalizing behavior positively through increased supervision is more complicated than one might expect. Evidence from our included studies suggested that attendance at after-school programs is poor or sporadic, and those most at-risk may be less likely to attend. Furthermore, (James-Burdumy et al. 2005) did not find after-school programs to increase supervision for youth. Instead, their findings suggested that participants would have been supervised had they not attended the after-school program (James-Burdumy et al. 2005).

Prior reviews and primary research suggest that program and participant characteristics may moderate effects of after-school programs, such as program quality and characteristics (Simpkins et al. 2004; Lauer et al. 2006; Durlak et al. 2010), while others have found no support for moderating variables (Roth et al. 2010). Although theory and research suggest several possible moderators of effects of after-school programs on youth outcomes, the heterogeneity of programs included in this review and the relatively poor reporting related to specific elements and staffing of the included after-school programs made it difficult to parse out differential effects across programs related to program or participant characteristics. Overall, evidence related to moderators and mediators of after-school program impacts is sparse and poorly developed. Future research of after-school programs could include testing of moderators and mediators in the evaluation design to improve our understanding of whether after-school programs are more or less effective based on program or participant characteristics.

In addition to findings of effects, another important finding of this review is related to the quality of evidence and the extent to which the findings are valid. All of the included studies had a number of methodological flaws that threaten the internal validity of the studies. The vast majority of the studies were rated high risk for selection bias, performance bias, and detection bias. Relatively few studies employed randomization, and those that did randomize participants rarely reported the methods by which they performed randomization. In all, results from this review and the conclusions that can be drawn about the effects of after-school programs are limited by the quality and rigor of the included studies. However, it is clear from this and prior reviews that the rigor of after-school program research must be improved.

Recommendations and Directions for Future Research

Although past after-school program reviews have consistently suggested improvements in the rigor of after-school program research, limited progress has been made. Our included studies displayed a high risk of bias within and across studies, impairing the extent to which we can draw conclusions about the effects of after-school programs on attendance and externalizing behaviors. However, since 2007, when prior reviews concluded their search (Durlak et al. 2010; Roth et al. 2010), more after-school program studies have used randomization. Indeed, 44 % of the included studies in this review published after 2007 used randomization procedures to assign students to condition, while only 20 % of studies published before or during 2007 assigned students randomly. This trend is encouraging, but must be maintained, and researchers must attend to other potential risks of bias, including minimizing performance and attrition bias, which were problematic in the studies included in this review. Randomization is the best approach to mitigating threats to internal validity; however, randomly assigning participants to condition is not always possible. When randomization is not possible, researchers could use more rigorous quasi-experimental designs, such as using propensity score matching, regression continuity design, or other design elements that could mitigate specific threats to internal validity that are often present in non-randomized studies (Shadish et al. 2002).

In addition to using more rigorous study designs and minimizing and mitigating potential bias, it is important for studies to measure and report variables that may moderate effects of after-school programs. Some reviews and individual studies have identified potential moderators of after-school programs and other types of organized youth activities, such as study quality and characteristics of the program (i.e., length, intensity, presence of specific components; Bohnert et al. 2010). To further examine these variables in a meta-analysis, the data on moderator variables need to be consistently measured and reported. We recommend for future studies that researchers measure and report key participant, intervention, and implementation characteristics that may moderate program outcomes. Although (Durlak et al. 2010) review called for the reporting of participant demographic information such as socio-economic status, race, and gender, this information continues to be underreported. In particular, socio-economic status, as measured by eligibility for free or reduced lunch, was reported in less than half of our included studies. Both demographic and participation information is important, however, to understand whether after-school programs may be more effective for some youth than others.

Furthermore, greater attention must be given to the program characteristics and mechanisms by which after-school programs may impact youth or with which effects may be associated. Research has found after-school program studies lack well-defined theories of change and intervention procedures, have poor utilization of treatment manuals, provide limited training and supervision for implementers, and infrequently measure fidelity (Maynard et al. 2013). While (Durlak et al. 2010) review found an impact of specific program practices on youth outcomes, many of the studies included in this review did not report this information to code with any degree of reliability. This lack of attention to intervention processes and implementation impedes our ability to examine program characteristics that may impact the effectiveness of after-school programs. Future studies could be improved by explicating a theory of change and reporting and measuring treatment procedures and fidelity.

Limitations

While this review improves upon and extends prior reviews of effects of after-school programs in a number of ways, the findings of this review must be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. Statistical power, particularly for the attendance outcome, could be low thereby inhibiting the ability to detect effects. Power analyses for robust variance estimation analyses are still being developed; thus, it is difficult to know for certain. We also suspect that outcome reporting bias may be an issue in after-school program intervention research as it has been found to be problematic in education research (Pigott et al. 2013). We only included studies that reported attendance or externalizing outcomes with sufficient data to calculate an effect size; however, researchers could have measured these outcomes but chose not to report them if they were not significant, thus potentially inflating the effects of after-school programs reported in this meta-analysis. Additionally, the review did not examine all outcomes for which after-school programs have been suggested to impact; thus, the results cannot be generalized to draw conclusions about the effect of after-school programs beyond the outcomes examined in this study. We were also limited in the number and types of moderators that we could examine in this study due to the lack of statistical power. Moreover, due to insufficient reporting of moderator variables in many of the studies included in this review, it was not possible to extract the data for potential moderator variables that may have been of interest. Also, because selection bias is problematic in after-school program intervention research, we limited studies included in this review to those that provided pre-test data of the outcomes of interest or adjusted for pre-test on the outcome, so we could control for selection bias to some extent. Although unlikely, we could have introduced review level selection bias by excluding studies that did not provide pre-test data or adjust for baseline differences. Despite our broad search and attempt to find studies in other countries, only one included study was conducted outside the United States; thus, the results of this review cannot be generalized to programs outside the United States. This review was also limited by the studies included in this review. Most of the studies lacked rigor and internal validity of the studies was compromised, thus limiting the causal inferences that could be drawn from the studies and the conclusions that can be made from this review.

Conclusion

After-school programs in the United States receive overwhelming positive support and significant resources; however, this review found a lack of evidence of effects of after-school programs on school attendance and externalizing behaviors for at-risk primary and secondary students. Moreover, methodological flaws and high risk of bias on most of the domains assessed in this review were found across included studies, which is consistent with findings from past reviews of after-school programs. Given these findings, a reconsideration of the purpose of after-school programs and the way after-school programs are designed, implemented, and evaluated seems warranted. After-school programs are expected to affect numerous outcomes, but attempt to do so without being intentional in the program elements and mechanisms they implement by using empirical evidence or theories of change in program design to affect those outcomes. It is clear that if our priority is to spend limited resources to provide supervision and activities for youth after school, we should also be investing in studying and implementing programs and program elements that are effective and grounded in empirical evidence and theory. Improving the design of the programs as well as the evaluations of after-school programs to examine specific elements and contexts that may affect outcomes could provide valuable information to realize the potential of after-school programs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for support from the Meadows Center for Preventing Educational Risk, the Greater Texas Foundation, the Institute of Education Sciences (Grants R324A100022, R324B080008, and R305B100016) and from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P50 HD052117). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the supporting entities.

Biographies

Kristen P. Kremer is a Doctoral Student at Saint Louis University. She received her masters in Social Work from Saint Louis University. Her major research interests include school engagement, academic achievement, cognitive development, youth violence, and research with at-risk students.

Brandy R. Maynard is an Assistant Professor at Saint Louis University and co-chair of the Social Welfare Coordinating Group of the Campbell Collaboration. She received her doctorate in Social Work from Loyola University Chicago. Her major research interests include the etiology and developmental course of academic risk and externalizing behavior problems; evidence-based practice and knowledge translation; and research synthesis and meta-analysis.

Joshua R. Polanin is an Institute of Education Sciences Post Doctoral Fellow at the Peabody Research Institute at Vanderbilt University and the Managing Editor of the Campbell Collaboration Methods Group. He received his doctorate in Education Research Methodology from Loyola University Chicago. His major research interests include systematic review and meta-analytic methods, prevention science, predictive modelling using statistical programs, bullying and disruptive behaviors, and academic achievement.