The National Resident Matching Program (the “Match”) was established in 1952 by medical students with the intent of establishing a predetermined date on which positions are made available to a pool of applicants.1 In 2014, nearly 30 000 first and second postgraduate year positions were made available through the Match. For US medical school seniors, geographic location was the top-ranking factor (93%) in selecting a program.2

The residency interview process that precedes the completion of the Match ranking list is an expensive and elaborate endeavor. Application fees and travel and accommodation costs can add up quickly, and they usually are not covered by financial aid. In addition, residency programs have their own recruiting costs and spend considerable time in preparation, requiring faculty to spend time away from clinical duties. The use of videoconference interviews for residency and fellowship programs (in various medical or surgical disciplines) has been associated with positive feedback from candidates,3,4 cost savings for candidates,4–8 and increased time efficiency.7,8 All of these support the incorporation of video technology into the interview process.

The internal medicine residency program directors at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona decided to follow in the footsteps of these pioneering programs and pilot our own videoconference interviews for the 2014 Match. Although videoconference interviewing is common in other settings, such as the business world,9 staff in these residency programs did not have any prior expertise. Based only on our experience with such programs as Skype (Microsoft Corp), we implemented a video interview process and quickly learned that attention to small, seemingly simple, details made a marked difference in the quality of the interview.

We offered videoconference interviews to 12 candidates, and 8 accepted. Candidates were selected for the videoconference interview if (1) their application met our criteria for an in-person interview, and (2) they were unable to attend (typically due to scheduling constraints). During an in-person interview, a candidate meets individually with 2 faculty members for 30 minutes each and the program director for 15 minutes. For our videoconference interviews, each candidate was interviewed by a panel (the program director, the associate program director, and 2 chief residents) for a total of 30 minutes. An option was given for scheduling interviews on 1 of 3 half-days, which included at least 1 morning and 1 afternoon option to accommodate time zone differences. Ultimately, 2 to 3 candidates were interviewed on each half-day. The panel remained in the room for the entire 30-minute videoconference.

Before the videoconference, interviewers compiled a list of preferred questions. These draft questions were reviewed and consolidated to avoid duplication and ensure that the highest-impact questions were asked. Each interviewer on a panel asked 1 to 2 questions and 1 standardized question. This standardized question was part of our interview process for all candidates, including those who interviewed in person.

In the more successful interviews, candidates were dressed in attire appropriate for an on-site interview and positioned the camera directly at eye level. They appeared to maintain eye contact and seemed completely engaged throughout the interview. These candidates also appeared to have reviewed the online program information and were prepared with questions. In contrast, in a less successful interview, the applicant positioned the camera such that he was looking downward and swiveled nervously in a wheeled chair.

The clear benefit of video interviewing for a residency or fellowship program is the ability to engage and interview candidates who are not able to participate in an on-site interview due to time or resource constraints. We assured every candidate who participated in a videoconference interview that they would be considered equally in the ranking process. We met some excellent candidates in the process of video interviewing, and we ranked 2 of the 8 in a position to match. Ultimately, we did not match any of our video-interviewed candidates.

One drawback to video interviewing is that candidates do not get to see the campus on the day of the interview. Daram et al3 reported that drawbacks to a fellowship interview by videoconference included a lack of interaction with fellows and faculty, as well as an inability to gain detailed knowledge about the city, the program, and the institution. To partially remedy this situation, we created a virtual tour of the campus that includes commentary by the chief residents. The candidates were given access to this video, as well as several electronic informational brochures to review before their interviews. Specific program information allowed a candidate to ask focused questions during the video interview. We also provided the candidates with resident contact information, so that they could ask additional questions directly to residents in our program. Still, our ability to convey the positive aspects of our program and institution likely were limited by the 30-minute interview format.

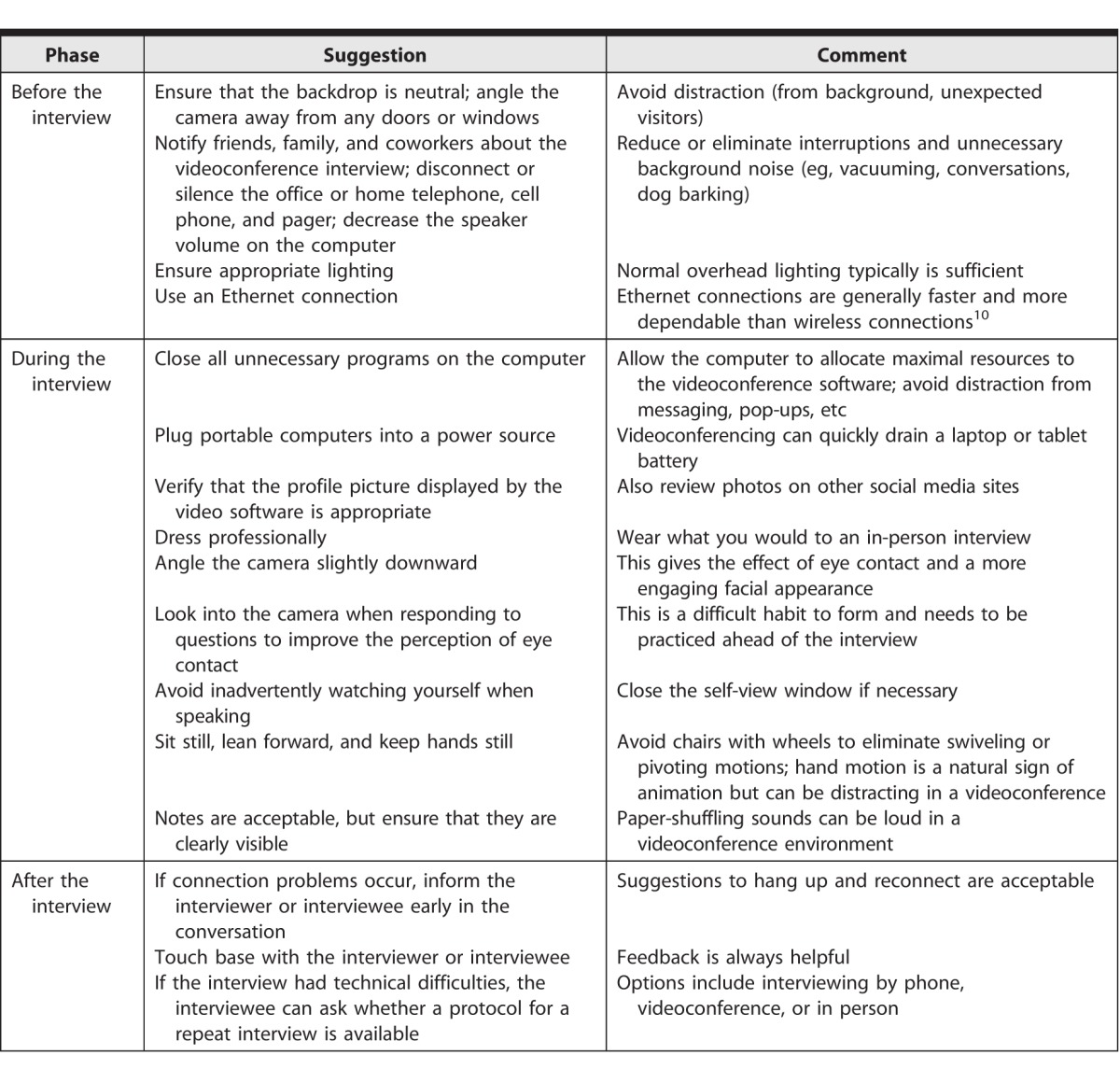

Our program leadership is still reviewing the experience with video-based interviews. We have learned a great deal through our initial experiences, and have summarized our videoconference interviewing tips for success (table).

TABLE.

Tips for Improving the Videoconference Interview

After the interviews, candidates were sent an anonymous electronic survey about their experience, and 6 responded with positive and valuable feedback. All candidates thought the electronic program materials were beneficial, with 4 indicating that the materials answered most of their questions. Suggestions included providing a resident-composed frequently asked questions (FAQ) document, and more information regarding tracks and fellowship opportunities. Only 1 candidate thought the video quality was poor during the interview; the remaining candidates had no difficulties with the technology. Three respondents thought the 30-minute time frame was sufficient; the other 3 indicated they would have preferred a longer interview or more time for questions. A total of 5 candidates thought the interview was sufficient to allow them to make a ranking decision, and all 6 said they would consider ranking a program in which they participated only in a videoconference interview.

Overall, we had a positive experience because we met with eligible candidates who otherwise would not have been able to interview. Therefore, we plan to offer these interviews again and likely will increase the number of available appointments. Based on the feedback we received, we will keep our program's informational materials viewable over a longer period of time, create an FAQ document from our residents, enhance the video tour of our facilities, and include a tip sheet for video-based interviews.

Footnotes

Kathryn Williams, MB, BCh, BAO, is Instructor of Medicine, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Arizona; Juliana M. Kling, MD, MPH, is Senior Associate Consultant, Division of Women's Health Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale; Helene R. Labonte, DO, is Consultant, Division of Community Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale; and Janis E. Blair, MD, is Consultant, Division of Infectious Diseases, Mayo Clinic Hospital, Phoenix.

References

- 1.National Resident Matching Program. The Match: what is the match? 2015 http://www.nrmp.org/about. Accessed April 20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Data Release and Research Committee, National Resident Matching Program. Results of the 2013 NRMP applicant survey by preferred specialty and applicant type. Washington, DC: National Resident Matching Program; 2013. 2015. http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/applicantresultsbyspecialty2013.pdf. Accessed April 20. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daram SR, Wu R, Tang SJ. Interview from anywhere: feasibility and utility of web-based videoconference interviews in the gastroenterology fellowship selection process. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(2):155–159. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasadhika S, Altenbernd T, Ober RR, Harvey EM, Miller JM. Residency interview video conferencing. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(2):426–426.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tiller D, O'Mara D, Rothnie I, Dunn S, Lee L, Roberts C. Internet-based multiple mini-interviews for candidate selection for graduate entry programmes. Med Educ. 2013;47(8):801–810. doi: 10.1111/medu.12224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melendez MM, Dobryansky M, Alizadeh K. Live online video interviews dramatically improve the plastic surgery residency application process. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(1):240e–241e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182550411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edje L, Miller C, Kiefer J, Oram D. Using skype as an alternative for residency selection interviews. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):503–505. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-12-00152.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shah SK, Arora S, Skipper B, Kalishman S, Timm TC, Smith AY. Randomized evaluation of a web based interview process for urology resident selection. J Urol. 2012;187(4):1380–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kennedy JL. 21st century video interview. In: Kennedy JL, editor. Job Interviews for Dummies. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons; 2012. pp. 39–50. In. ed. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzalez D. Wi-Fi (wireless) vs. ethernet: which one should you use? 2015 http://dagonzalez.hubpages.com/hub/Wi-fi-vs-Ethernet. Accessed April 20. [Google Scholar]