Abstract

Background

Resident physicians provide much of the clinical teaching for medical students during their clerkship rotations, but often receive no formal preparation or structure for teaching and mentoring students.

Objective

We sought to evaluate a medical student mentoring program (MSMP) for students during their obstetrics and gynecology clerkship at a midwestern teaching hospital during the 2013–2014 academic year.

Methods

A senior resident physician was assigned 1 to 2 medical students for a 6-week rotation. Students were provided MSMP information during clerkship orientation; residents were given information on MSMP requirements and were randomly assigned to students. We surveyed students and residents about their experience with the MSMP.

Results

Of 49 eligible medical students, 43 (88%) completed postsurveys. All students reported not having a mentoring program on other clerkships. Postclerkship, students indicated that they would participate in the MSMP again (32 of 38, 84%), and felt that having a mentor on other clerkships (30 of 36, 83%) would be beneficial. Students reported receiving educational (20 of 41, 49%) and procedural (33 of 41, 80%) instruction, personal development feedback (23 of 41, 56%), and career advice (14 of 41, 34%) from resident mentors. Out of a total of 45 possible surveys by residents, 17 (38%) were completed. Residents did not feel burdened by students (14 of 17, 82%), and all responded that they would participate in the MSMP again.

Conclusions

Feedback from medical students suggests that a mentoring program during clerkships may provide potential benefits for their careers and in 1-on-1 instruction.

What was known and gap

Much of medical student education during clinical clerkships is provided by residents; students report that the transition to clerkship can be challenging.

What is new

A medical student mentoring program assigned students to senior residents. Students reported receiving instruction, personal development feedback, and career advice from resident mentors.

Limitations

Single site, single specialty study, and small sample size; survey tool lacks validity evidence.

Bottom line

The mentoring program benefited student education and students' perception of the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship experience.

Editor's Note: The online version of this article contains survey questions for medical students and resident mentors regarding the mentoring program.

Introduction

High-quality interactions between resident physicians and medical students have been shown to increase the quality of education as perceived by medical students, with the amount of time spent with resident teachers and mentors a large contributing factor.1,2 Moreover, positive experiences with resident physicians as teachers and perceived quality of education have been significantly associated with clerkship satisfaction.3

To learn all aspects of obstetrics and gynecology (ob-gyn), the ob-gyn residency program at the University of Kansas School of Medicine–Wichita (KUSM-W) places medical students with 20 residents and more than 40 attending physicians with full-time clinical practices. However, being or feeling overwhelmed is a barrier to students' success. Common struggles for students transitioning to clerkships include adjusting to the culture of patient care, performing clinical tasks, learning logistics, and understanding roles, responsibilities, and expectations in clinical settings.4 Medical students are concerned with knowing their role on a medical team, and have described feeling lost during clerkships.4 Despite available surgical and clinical opportunities, medical students consistently ranked the KUSM-W ob-gyn clerkship experience poorly, citing such common reasons as lack of continuity, unclear understanding of responsibilities, and nonexistent team atmosphere.5

Evidence stresses the importance of resident interaction on medical student education. One study suggests that surgical resident physicians can improve learning environments simply by having daily interactions with medical students, and residents can demonstrate clinical skills while also being approachable.6 Similarly, 1 factor shown to improve residents' teaching behaviors included the presence of a medical student on the team.7 Medical students report learning from residents in a variety of formats and often remember learning topics regarding ob-gyn from a resident.3 Furthermore, in medical student evaluations, residents outscored attending physicians in 12 of the 14 qualities noted as being important for a clinical mentor.8 Noting the importance of residents in medical education, this article focuses on the establishment of a mentoring program utilizing resident physicians as mentors in ob-gyn.

Methods

A medical student mentoring program (MSMP) was established by residents under the guidance of the department chair. Establishing the program was driven by the desire to improve medical students' evaluation of the clerkship, and to enhance the relationship between resident physicians and students. Specific goals of the program included encouraging frequent interactions, providing feedback from attending or resident physicians, and fostering discussions concerning education, career advice, and personal well-being. The program was implemented during the 2013–2014 academic year, beginning with the third rotation.

Third- and fourth-year residents served as mentors to third-year medical student mentees during the ob-gyn clerkship. On average, there were 6 to 10 students per 6-week clinical rotation. Each resident was randomly assigned a maximum of 2 mentees per 6-week core clinical rotation without taking into account sex or any personal preferences. All senior residents participated as mentors during the duration of the program.

Mentors were given an information sheet regarding the MSMP requirements at the beginning of each clerkship rotation, which reinforced increasing medical student interactions with all resident physicians. MSMP requirements included weekly meetings at a location negotiated between mentee and mentor, covering SOAP (subjective, objective, assessment, plan) notes, providing feedback, and answering questions regarding the rotation. Mentors could also cover additional topics, including professional development, career advice, and procedural instruction.

Mentees were provided with information regarding the mentor program during orientation on the first day of the clerkship, and were responsible for contacting their mentor to set up the initial meeting. Meetings were to take place in neutral settings; otherwise, no other restrictions were placed on mentor-mentee meetings. Mentees also worked directly with their mentor in the clinical setting, but were advised that meetings should occur outside of daily responsibilities.

Mentees completed a questionnaire at orientation prior to interacting with their mentor and again during the last week of the clerkship, and mentors completed a survey at the conclusion of the clerkship (provided as online supplemental material). Mentors were not required to complete surveys, but feedback was helpful for quality improvement purposes.

The mentoring program and associated evaluations were reviewed by the KUSM-W Human Subjects Committee 2 Institutional Review Board; the board determined that this constituted a quality improvement project.

Data were collected, managed, and analyzed using SurveyMonkey, Microsoft Excel, and SAS version 9.3 software (IBM Corp). Descriptive statistics were performed, and results are presented as frequencies and proportions.

Results

Mentee surveys were collected from 43 of 49 (88%) eligible third-year medical students. Slightly more than half of the mentees were men (23 of 42, 55%), and a majority (30 of 43, 70%) had completed 3 to 4 other clinical rotations prior to starting the ob-gyn clerkship. All mentees reported not having a MSMP available on other clinical rotations.

Weekly Meetings

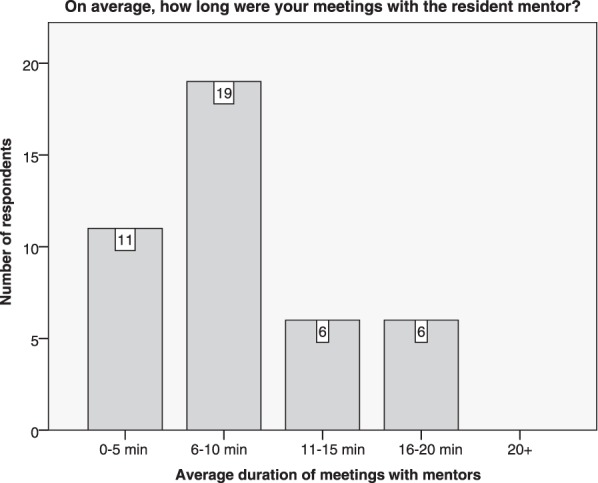

During the 6-week clerkship, more than half (31 of 42, 74%) of mentees reported having 5 or more meetings, and 10 (24%) respondents reported having 3 to 4 meetings with their resident mentors. Almost half (19 of 42, 45%) of the mentees reported meetings with their mentors lasted 6 to 10 minutes (figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Duration of Weekly Meetings

Discussion Topics and Feedback

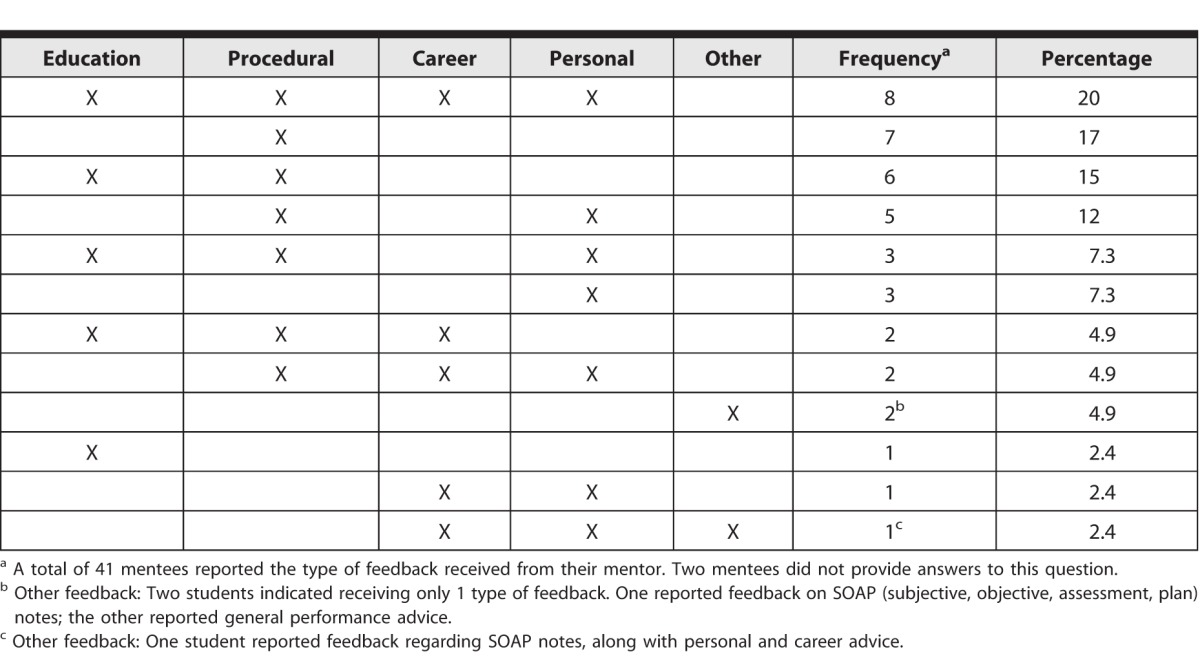

Among the 43 mentees, 41 (95%) reported receiving multiple types of feedback from mentors (table). Procedural instruction was the topic most reported by mentees (33 of 41, 80%), followed by personal development and support (23 of 41, 56%), and then career advice (14 of 41, 34%). Most mentees (28 of 42, 67%) reported receiving feedback from their mentors on 5 or more occasions.

TABLE.

Resident Mentor Discussion and Teaching Topics Reported by Medical Students

Mentee-Mentor Relationship

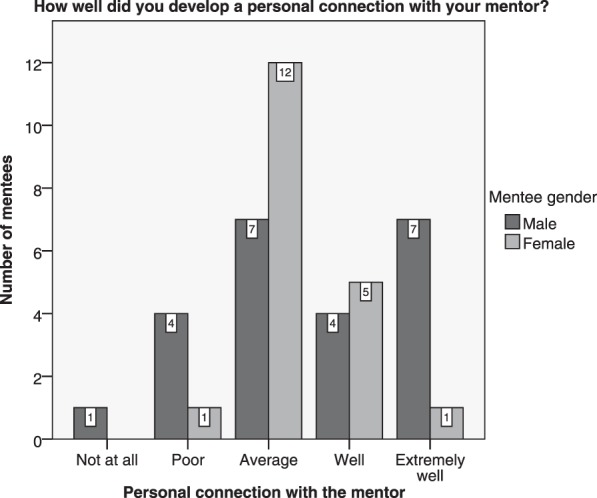

Many mentees reported feeling well or extremely well connected with their mentor (17 of 43, 40%), but 5 (12%) reported developing a poor connection with their mentor (figure 2). One of 19 female students (5%) reported developing an extremely good connection with her mentor, whereas 7 of 23 (30%) male students reported developing an extremely good connection with their mentor.

FIGURE 2.

Mentee-Mentor Personal Connection

Perception of Specialty and Clerkship

Postclerkship, many mentees (32 of 38, 84%) indicated that they would participate in the MSMP again. Most (30 of 36, 83%) felt that medical students could benefit from having a mentor on other clinical clerkships, and perceived the ob-gyn clerkship as being beneficial to their education (34 of 41, 83%). The majority (27 of 30, 90%) indicated that the MSMP had a positive effect on their clerkship experience.

Residents' Perception as Mentors

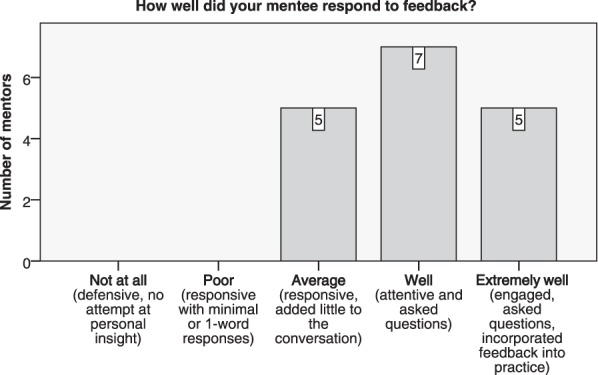

Residents provided 17 out of 45 possible responses (38%) on their perception of the MSMP program. In 2 instances (12%), a mentor reported having 2 mentees during the clerkship. Mentors felt that mentees responded well (7 of 17, 41%) or extremely well (5 of 17, 29%; figure 3) to feedback. In regards to the mentor-mentee relationship, mentors reported developing a well-connected relationship (3 of 17, 18%) or average connection (13 of 17, 76%) with their mentee. Most mentors (14 of 17, 82%) were not burdened by the MSMP. In contrast, 3 mentors (18%) felt burdened, specifically describing mentoring as “time consuming.” All mentors responded that they would participate in the MSMP again.

FIGURE 3.

Mentee Response to Feedback

Discussion

A mentoring program utilizing resident physicians as mentors proved not only to be beneficial to medical students, but also was not a burden to most resident physicians. This is consistent with previous research that reports residents spend 25% of their time teaching students and that both students and residents enjoy these experiences.9 The results of our project indicate that most meetings between residents and medical students tended to last less than 10 minutes, and although this may be the reason why residents felt the mentoring responsibility to be less of a burden, time constraints and scheduling have been shown to be an obstacle when forming a mentoring relationship.10

The MSMP provided feedback opportunities for medical students by establishing frequent meetings with resident physicians. Although 1 meeting each week throughout the clerkship may not seem substantial, every 1-on-1 interaction provided additional support to students. The MSMP created a structured program for feedback. Clerkship performance was reviewed by mentors and mentees on a weekly basis, and the program helped monitor student progress throughout the clerkship. Furthermore, improvement in students' perception of the ob-gyn clerkship was noted in feedback from the department chair and the medical school. The effect was also observed by an increase in medical students applying to our residency program (2 applicants in 2014 versus 11 applicants in 2015). Our MSMP places a focus on learning about the specialty, rather than pushing away medical students as they struggle with problems when entering clerkships.4

Although mentoring responsibilities were well-defined, mentors spent much of their time focusing on procedural instruction. Furthermore, not all students developed a good connection with their mentor. Students who developed poor connections with their mentors still reported having a similar number of meetings and evaluated their mentors' preparedness, engagement, and appropriateness of feedback in a range of average to excellent. This suggests a need to develop ways to help resident mentors be more personal, as previous research has shown that students view the mentors as more supportive than just supplying knowledge.10 An in-depth explanation of mentorship should be emphasized, with an increased focus on such interpersonal skills as friendliness, approachability, and relatedness. Developing resident mentoring skills has the potential to improve the clerkship learning environment and would better prepare resident physicians in their teaching roles.6

The discrepancy between male and female students who indicated developing an extremely good relationship with their mentor deserves discussion. This finding may result from the mentoring program helping male students overcome some of the discomfort they experience in being part of the clinical team in ob-gyn. Male medical students have described feeling socially excluded from female-dominated clinical teams.11

The generalizability of our program's findings is limited by a small sample size (N = 43). Although the MSMP had minimal requirements for residents, varying degrees of “mentorship” were observed due to lack of mentor orientation or follow-up midclerkship. Not all resident mentors approach teaching with the same vigor, and mentor availability was variable. In addition, no validity evidence for the surveys is available, and respondents may have interpreted the questions differently from what was intended. Mentor feedback also dropped moderately as the program aged. One reason for this may be the request to the same individuals to answer the survey multiple times.

Conclusion

Establishing a MSMP utilizing residents is a novel practice that can improve the educational experience of medical students during core clerkships. The program promoted increased resident interactions with medical students and provided opportunities for feedback to improve medical student education during clinical clerkships. Our MSMP program for an ob-gyn clerkship was well accepted by medical students, encouraged open lines of communication, and improved medical student education.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

All authors are in the University of Kansas School of Medicine–Wichita. Jackson Sobbing, DO, is Clinical Instructor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology; Jennifer Duong, MPH, is Research Assistant, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology; Frank Dong, PhD, is Research Assistant Professor, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health; and David Grainger, MD, MPH, is Daniel K. Roberts Professor and Chair, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

Funding: The authors report no external funding source for this study.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Brown RS. House staff attitudes toward teaching. J Med Educ. 1970;45(3):156–159. doi: 10.1097/00001888-197003000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tonesk X. The house officer as a teacher: what schools expect and measure. J Med Educ. 1979;54(8):613–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huynh A, Savitski J, Kirven M, Godwin J, Gil KM. Effect of medical students' experiences with residents as teachers on clerkship assessment. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(3):345–349. doi: 10.4300/JGME-03-03-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O'Brien B, Cooke M, Irby DM. Perceptions and attributions of third-year student struggles in clerkships: do students and clerkship directors agree? Acad Med. 2007;82(10):970–978. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31814a4fd5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolmans DH, Wolfhagen IH, Heineman E, Scherpbier AJ. Factors adversely affecting student learning in the clinical learning environment: a student perspective. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2008;21(3):32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu TC, Lemanu DP, Henning M, Maccormick AD, Hawken SJ, Hill AG. General surgical interns contributing to the clerkship learning environment of medical students. Med Teach. 2013;35(8):639–647. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.801550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkerson L, Lesky L, Medio FJ. The resident as teacher during work rounds. J Med Educ. 1986;61(10):823–829. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198610000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nguyen SQ, Divino CM. Surgical residents as medical student mentors. Am J Surg. 2007;193(1):90–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sternszus R, Cruess S, Cruess R, Young M, Steinert Y. Residents as role models: impact on undergraduate trainees. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1282–1287. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182624c53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalen S, Stenfors-Hayes T, Hylin U, Larm MF, Hindbeck H, Ponzer S. Mentoring medical students during clinical courses: a way to enhance professional development. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):e315–e321. doi: 10.3109/01421591003695295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang JC, Odrobina MR, McIntyre-Seltman K. The effect of student gender on the obstetrics and gynecology clerkship experience. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19(1):87–92. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.