Abstract

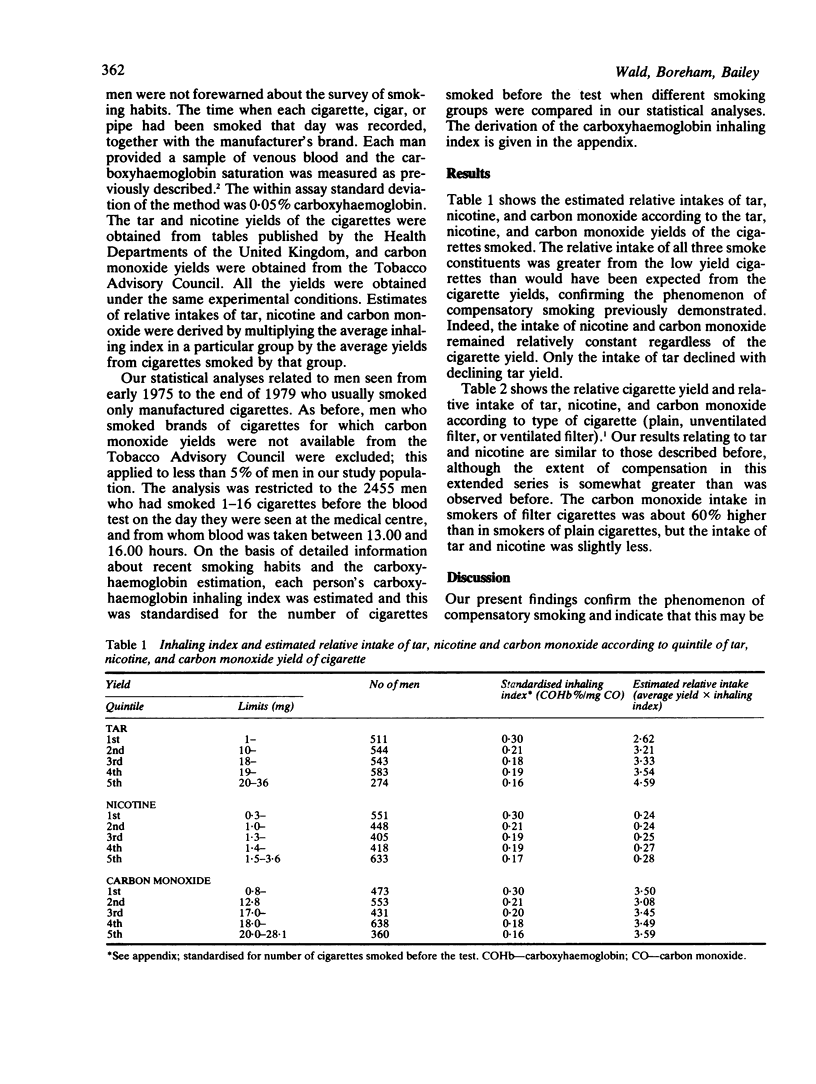

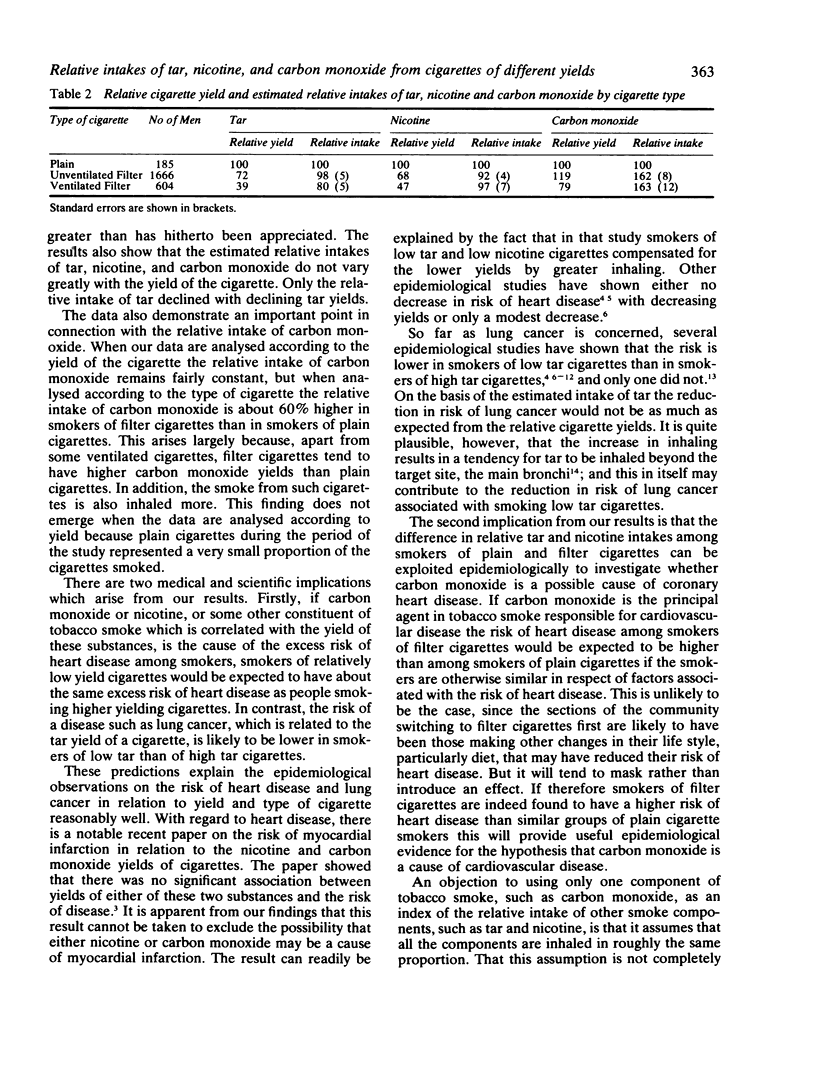

The relative intakes of tar, nicotine, and carbon monoxide were estimated in 2455 cigarette smokers, who freely smoked their usual brands of cigarette. The estimates were derived by using an objective index of inhaling based on the measurement of carboxyhaemoglobin divided by the carbon monoxide yield of the cigarettes smoked, after background and carry over carboxyhaemoglobin effects had been allowed for. Separate analyses were performed according to the yield and type (plain, filter, etc) of cigarette smoked. The analyses based on yield indicated that the extent of inhaling was adjusted sufficiently to achieve similar intakes of nicotine/carbon monoxide regardless of the nicotine/carbon monoxide yield. It was not, however, sufficiently increased to achieve a similar intake of tar as the tar yield of the cigarette decreased. The analyses based on type of cigarette indicated that the extent of inhaling was adjusted to achieve similar intakes of tar and nicotine regardless of the type of cigarette smoked, but that this led to a greater intake of carbon monoxide among filter cigarette smokers than that among smokers of plain cigarettes--more so than would have been expected from their relative carbon monoxide yields. Two conclusions arise from these results. Firstly, any harmful effects of nicotine/carbon monoxide are unlikely to be materially reduced by smoking cigarettes with lower yields of nicotine/carbon monoxide, but the harmful effects of tar are likely to be reduced by smoking cigarettes with lower tar yields. These predictions appear to be borne out by epidemiological observations. Secondly, any harmful effects of carbon monoxide on the cardiovascular system will be greater in smokers of modern filter cigarettes than in smokers of modern plain cigarettes, provided that these two groups of smokers are otherwise similar with respect to risk of cardiovascular disease.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Benowitz N. L., Hall S. M., Herning R. I., Jacob P., 3rd, Jones R. T., Osman A. L. Smokers of low-yield cigarettes do not consume less nicotine. N Engl J Med. 1983 Jul 21;309(3):139–142. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198307213090303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bross I. D., Gibson R. Risks of lung cancer in smokers who switch to filter cigarettes. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1968 Aug;58(8):1396–1403. doi: 10.2105/ajph.58.8.1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castelli W. P., Garrison R. J., Dawber T. R., McNamara P. M., Feinleib M., Kannel W. B. The filter cigarette and coronary heart disease: the Framingham study. Lancet. 1981 Jul 18;2(8238):109–113. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(81)90297-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond E. C., Garfinkel L., Seidman H., Lew E. A. "Tar" and nicotine content of cigarette smoke in relation to death rates. Environ Res. 1976 Dec;12(3):263–274. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(76)90036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne V. M., Fry J. S. Smoking and health: the association between smoking behaviour, total mortality, and cardiorespiratory disease in west central Scotland. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978 Dec;32(4):260–266. doi: 10.1136/jech.32.4.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higenbottam T., Shipley M. J., Rose G. Cigarettes, lung cancer, and coronary heart disease: the effects of inhalation and tar yield. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1982 Jun;36(2):113–117. doi: 10.1136/jech.36.2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman D. W., Helmrich S. P., Rosenberg L., Miettinen O. S., Shapiro S. Nicotine and carbon monoxide content of cigarette smoke and the risk of myocardial infarction in young men. N Engl J Med. 1983 Feb 24;308(8):409–413. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198302243080801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimington J. The effect of filters on the incidence of lung cancer in cigarette smokers. Environ Res. 1981 Feb;24(1):162–166. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(81)90142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepney R. Would a medium-nicotine, low-tar cigarette be less hazardous to health? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 Nov 14;283(6302):1292–1296. doi: 10.1136/bmj.283.6302.1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton S. R., Feyerabend C., Cole P. V., Russell M. A. Adjustment of smokers to dilution of tobacco smoke by ventilated cigarette holders. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1978 Oct;24(4):395–405. doi: 10.1002/cpt1978244395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vutuc C., Kunze M. Lung cancer risk in women in relation to tar yields of cigarettes. Prev Med. 1982 Nov;11(6):713–716. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(82)90033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald N. J., Idle M., Boreham J., Bailey A. Inhaling habits among smokers of different types of cigarette. Thorax. 1980 Dec;35(12):925–928. doi: 10.1136/thx.35.12.925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald N., Idle M., Bailey A. Carboxyhaemoglobin levels and inhaling habits in cigarette smokers. Thorax. 1978 Apr;33(2):201–206. doi: 10.1136/thx.33.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynder E. L., Mabuchi K., Beattie E. J., Jr The epidemiology of lung cancer. Recent trends. JAMA. 1970 Sep 28;213(13):2221–2228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynder E. L., Stellman S. D. Impact of long-term filter cigarette usage on lung and larynx cancer risk: a case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1979 Mar;62(3):471–477. doi: 10.1093/jnci/62.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]