Abstract

Objectives

To provide a brief overview of disparities across the spectrum of breast cancer incidence, treatment, and long-term care during the survivorship period.

Data sources

Review of the literature including research reports, review papers and clinically based papers available through PubMed and CINAHL.

Conclusion

Minority women generally experience worse breast cancer outcomes despite a lower incidence of breast cancer than whites. A variety of factors contribute to this disparity, including advanced stage at diagnosis, higher rates of aggressive breast cancer subtypes, and lower receipt of appropriate therapies including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation. Disparities in breast cancer care also extend into the survivorship trajectory, including lower rates of endocrine therapy use among some minority groups as well as differences in follow-up and survivorship care.

Implications for Nursing Practice

Breast cancer research should include improved minority representation and analyses by race and ethnicity and socioeconomic status. While we cannot yet change the biology of this disease, we can encourage adherence to screening and treatment and help address the many physical, psychological, spiritual and social issues minority women face in a culturally sensitive manner.

Keywords: breast cancer, disparities, quality of life, symptoms

The burden of breast cancer is not shared equally among all women in the United States. Non-Hispanic white women have a 5-year survival rate of 88.6% while African American women have a 78.9% rate, the lowest of all minority groups. Other variations in 5-year survival rates include Hispanic/Latina women (87%), Asian women (91.4%), and American Indian/Alaska Native American women (85.4%).1

Most of the research that has been done on minority breast cancer survivors focuses on the differences between non-Hispanic white women and African American women. Even though black women now receive screening mammography at least as often as white women, there remains a persistent problem of health disparities in breast cancer care and outcomes.2-7 Mortality rates remain higher among black women despite the fact that breast cancer incidence is higher in white women.1 Such data suggest that racial differences in biology, receipt of appropriate and timely treatment and follow-up care, and other non-cancer-related conditions may account for differences in all-cause and breast cancer-specific mortality.3, 4, 8-10 This article will explore why these variations may exist across the breast cancer care continuum. (Table 1)

Table 1. Sources of racial/ethnic disparities across the breast cancer care continuum.

| Etiology/Risk Factors for Breast Cancer | Breast Cancer Detection and Identification of Tumor-Specific Factors | Treatment | Survivorship |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

Epidemiology

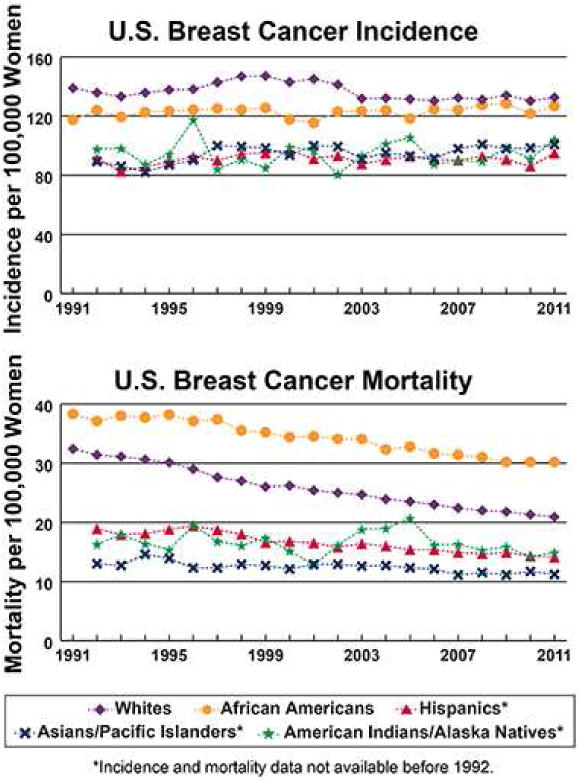

Decades of accumulated evidence supports the arguments that differences exist in tumor behavior and morphology,2-5, pharmacogenetic responses to therapy13, socioeconomic status, access to early screening and treatment11, 14, 15, and differences in patient-level behavioral factors.1, 11, 12 All may contribute to differences in breast cancer outcomes by race (Figure 1)16.

Figure 1.

U.S. breast cancer incidence and mortality by race from 1991 – 2011.16

Epidemiology of Breast Cancer by Race and Age

Black women have a 40% higher likelihood of death due to breast cancer than white women, suggesting that racial disparities may play an important role in health outcomes.1 Age and breast cancer are closely and meaningfully correlated with the median age at breast cancer diagnosis at 62 years 17, 18 Younger women (< age 50) often have more aggressive tumors and lower survival rates, whereas older women typically have slower growing tumors with a better prognosis.17, 18 African American women are more often diagnosed at a younger age, when the disease tends to have a worse prognosis. For black women under the age of 35, the incidence of invasive breast cancer is twice that of white women, and breast cancer mortality in this group is three times that of age-matched white women. A crossover occurs around the time of menopause with incidence rates among older white women surpassing rates of older black women.17, 19, 20 Notably mortality rates remain higher in black women regardless of age.

Younger women and African American women also have a greater burden of triple-negative breast cancers (i.e., estrogen receptor [ER], progesterone receptor [PR], and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 [HER2/neu] protein expression negative), which confers a poorer prognosis 20-22

Etiology and Biologic Risk Factors by Race

The risk of developing breast cancer is related to a number of factors, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, familial history of breast cancer, cumulative endogenous and exogenous hormone exposure, inherited mutations in breast cancer genes 1 and 2 (BRCA1, BRCA2) and other genes, high breast density, radiation exposure, diet, exercise, and post-menopausal obesity, many of which vary by race.18,19

Biological factors may also contribute in part to racial/ethnic differences observed in breast cancer. Biomarkers, histological features, and tumor behavior of breast cancers vary by race/ethnicity.4, 23 These findings further support the argument that biological differences in breast cancer exist between racial groups.

Screening Patterns

Despite the accumulating evidence for genetic and molecular biologic explanations for cancer aggressiveness, black women still have worse outcomes, even after controlling for ER, PR, and HER2/neu status and BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. Much of this difference was attributed historically to poor access to and follow-up after screening mammography.9, 23 However African American women have been receiving screening mammography at comparable rates to white women for a decade or more. Differences in mortality by race persist even when controlling for later stage at diagnosis due to omission of or delayed receipt of screening mammography. Thus, it is unlikely that screening differences explain racial differences in outcomes in the current era of breast cancer.7

Disparities in Treatment

While pre-diagnosis factors including differences in tumor biology and presenting stage certainly contribute to disparities in breast cancer outcomes, persistent racial gaps in stage-specific and subtype-specific survival suggest that other post-diagnosis factors also play an important role. Disparities have been documented across the treatment spectrum including surgery, radiation, chemotherapy and endocrine therapy.

Differences in Surgery and Radiation Therapy

In the 1980's and 90's, research on surgical treatment disparities focused on lower rates of breast conservation surgery among non-white women. The overall use of breast conservation surgery has increased over time, and the racial gap in access appears to have narrowed.24 However, in a recent national study of Medicare beneficiaries, African American and other non-white women remain modestly less likely than whites to undergo breast conserving surgery rather than mastectomy, after adjustment for other clinical and demographic factors.25 Other factors associated with lower likelihood of breast conserving surgery include geographic region, with rates being lowest in the South and highest in the Northeastern United States. Other factors include lower availability of radiation oncologists in the area of residence, higher county-level poverty, lower educational attainment, and residing in a rural rather than metropolitan area.25 These data suggest that structural factors affect access to care rather than race, and may be primary drivers of surgical treatment disparities in the modern era.

Interestingly, in a survey-based study of a diverse group of breast cancer patients, greater patient involvement in decision-making (compared to shared or passive decision-making) was associated with higher likelihood of receiving mastectomy among all racial groups, including African Americans, low- and high-acculturated Latinas, and whites.24 Thus, patient preference for treatment perceived as more aggressive or risk-reducing may also decrease uptake of breast conserving surgery, regardless of race.

Other research on surgical disparities has focused on management of the axilla. Surgical staging of the axilla is a standard of care in breast cancer treatment, but advances in the field in the past decade support the less morbid surgical alternative of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB).26 SLNB rather than full axillary dissection is the preferred option in most women with early stage disease. However, there was a consistently lower likelihood of receiving SLNB among African American women. 26 These findings suggest that disparities in the receipt of SLNB may be mediated by features of the institution that would logically lead to earlier adoption of innovative treatments, and geographic differences.

Significant gaps also occur in the access of poor and minority women to appropriate radiation therapy facilities. Radiation following breast conserving therapy is the standard of care for women, but is often delayed or missed in vulnerable populations. African American race, living in rural Appalachia, lack of insurance, and age >70 were all associated with lower rates of radiation following breast conserving surgery.27 This treatment disparity had a measurable effect on patient outcomes: not receiving radiation in this study was associated with lower overall survival at 10 yrs. In similar studies of Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Medicare patients, related factors emerged.28,29 Non-white race, rural compared to urban residence, older age, and greater burden of co-morbidities were all associated with lower likelihood of receiving appropriate radiation.28,29 In one study, surgeon factors were also significant predictors of receiving radiation including gender (patients of female surgeons more often received treatment), US-trained, and holding an MD rather than a DO degree.28 As with other treatment disparities, these data suggests that the clinical site and provider of care may be drivers of differential treatment.

Data are also available regarding disparities in breast reconstruction following mastectomy. Reconstruction rates after mastectomy varied significantly by race, with 41% of whites, 34% of African Americans, 41% of highly-acculturated Latinas, and only 13.5% of low-acculturated Latinas undergoing reconstruction.30

Differences in Chemotherapy

In recent studies minority women appeared to be equally likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy compared to their white counterpart.31,32 However, in one study minority women appeared to fare worse in the timeliness and completion of treatment, with both Hispanics and African Americans being more likely than white women to have delays in chemotherapy.33 African American women more often fail to complete treatment14 and more often receive non-standard regimens or reduced doses.34 In addition, completion rates for trastuzumab-based chemotherapy, which involves a year of intravenous treatment and significantly improves outcomes in HER2 positive breast cancer, are dramatically lower among African American women whereas Hispanic women appear equally likely to complete therapy compared to whites.14 These differences may relate to the significant social and financial stresses imposed by chemotherapy, such as extended time off work and transportation to frequent medical visits, but evidence to support this hypothesis is lacking.

Differences in Endocrine Therapy

Oral anti-estrogen medications including anti-estrogens and aromatase inhibitors are the standard of care for long-term prevention of recurrence among women with hormone-receptor positive breast cancers. These drugs are relatively inexpensive compared to chemotherapy and trastuzumab, non-toxic yet potent treatment, and easy to take at home. Unfortunately, medication adherence to endocrine therapy is a significant problem in the breast cancer population, and emerging evidence suggests that this issue may be more problematic in disadvantaged women. Two studies of Medicaid populations have found extremely low rates of endocrine therapy use in this group, with only 50% of eligible patients filling a prescription within one year35, and 50% of therapy initiators becoming non-adherent by year four.36

In the broader population, a recent study in a privately insured cohort found significantly lower rates of endocrine therapy initiation among African American compared to white women.37 Ongoing work by our group suggests that adherence after initiation is also low among young African American women. These findings constitute a need for the development of targeted interventions to improve adherence and breast cancer outcomes among poor and non-white women. Data on endocrine therapy adherence among minority populations other than African Americans is limited, but one study suggested that extremes of age (oldest and youngest patients) and increasing co-morbidity were associated with lower likelihood of completing therapy, while Asian compared to white women were associated with a higher likelihood of completion.38

Survivorship Care

A number of disparities exist in care during and beyond the initial treatment for breast cancer including health maintenance, side effect management, prevention of second cancers, and health promotion. For example, differences were noted in preventive care; black women were less likely to receive a flu vaccine, cholesterol screening, or bone density after a breast cancer diagnosis than white women. 39 Comorbid illnesses also varied by race and ethnicity with arthritis highest in whites (55.2%), and hypertension (71.1%) and diabetes (30.1%) higher in blacks.40 White women were more likely to be higher alcohol users and former smokers while black women were more likely to be obese five years or more after diagnosis.40 Quality of life was influenced by unemployment, being uninsured, having 1-2 comorbidities, higher life disruption, and daily stress. However, no differences in survivorship outcomes were noted between African American and non-Hispanic white women.41, 42

Symptoms

Common symptoms alone or in combination after breast cancer treatment include fatigue, depression, anxiety, pain, sleep disturbance, pain, and cognitive dysfunction43, 44. Of these symptoms, fatigue, depression and pain had the greatest impact on overall quality of life leading to poorer health status and worse functioning.44 Sleep was worse in minority women and was positively correlated with fatigue and depression.45 Black women also had higher rates of moist desquamation when treated with radiation therapy in addition to women who were obese and postmenopausal.46

After treatment physical activity was associated with fewer symptoms including fatigue and pain and better physical functioning and quality of life; findings were similar for non-Hispanic white and Hispanic women with breast cancer 47 However, fewer African American women met recommended levels for physical activity48 and had lower physical functioning. Mental health in African American women was positively correlated with social support but white women were not.

Financial Impact

The financial impact of having breast cancer was higher in low income women as they experienced higher job loss or longer delays in return to work after diagnosis.49 Minority women were more likely to be manual laborers and more likely to lose their job or stop working after their breast cancer.50 Latina women who received chemotherapy were also more likely to lose their job than white women.50 Jobs with less work schedule flexibility were detrimental to continued work regardless of other sociodemographic or treatment characteristics. In addition, being unemployed contributed to poorer mental health.42

Hispanic/Latina

In a systematic review of 22 quality of life studies in Latina women with breast cancer, 51 quality of life was lower than in non-Latina white, black or Asian American women.51 This included poorer emotional functioning, greater fear of recurrence, depression, and physical and social functioning.51 These differences were more pronounced in women with low acculturation. Another review of 37 studies of health-related quality of life in Latina survivors of breast cancer also reported poorer emotional and physical domains.52

Native Americans

Burnhansstipanov and colleagues surveyed 266 Native American breast cancer survivors with the help of Native American patient advocates.53 They evaluated their cross-sectional study by time since diagnosis and found significant differences in physical quality of life between those diagnosed less than 5 years (greatest impact in first year from diagnosis), and 5 years and beyond.53 The most significant symptoms included fatigue, weakness, anemia, pain, neuropathy, appetite and infections. Many respondents reported difficulty accessing and paying for cancer care.53 In comparison with non-Native cancer survivors, Native Americans scored lower for physical and social domains, similar for psychological domains, and higher in spiritual quality of life domains.53 The development of a culturally-specific cancer support with education program, Native American Cancer Survivor Support Circles, increased participants' confidence in their abilities to cope with their cancer.54

Asian

Wen and colleagues55 conducted a systematic review on Asian Americans breast cancer experiences and health related quality of life. There was significant variation within subgroups but the authors identified many unmet physical and emotional needs in the 26 studies they evaluated.55 Factors that influenced these women's well-being included their level of acculturation as determined by English proficiency and length of residency in the US.55

Many of the existing evidence-based interventions to help breast cancer survivors are not culturally or linguistically appropriate, limiting their effectiveness in the Asian American population. Chinese immigrant women were less likely to report physical distress or have problems resolved than US-born Chinese and non-hispanicwhite women.56

National Efforts to Improve Survivorship Care

The National Cancer Institute funded 25 Community Networks Programs to increase awareness of, and access to cancer screening in diverse populations. Some groups also developed programs to enhance survivorship for their specific community.57 From these experiences, they identified four elements for building survivorship programs for diverse groups: 1) engaging survivors from diverse groups in program planning and delivery; 2) involving survivors in research to enhance understanding, 3) improving well-being of diverse groups, and 4) respecting diverse cultures by attending to spirituality, storytelling, cultural values, and ceremony.57

Conclusion

We have identified a number of areas across the cancer continuum where disparities contribute to poorer outcomes for women with breast cancer. (Table 1) The least advantaged women appear to have more issues in facing and living with their breast cancer. The magnitude of survivorship problems faced by minority groups are not as well-defined or studied but include risk factors, screening, diagnosis and treatment, and survivorship beyond treatment. Each of these areas may need to be targeted to begin to close the gaps in quality of life and survival. We need to conduct more longitudinal studies with broad diverse samples to better identify how disparities influence these outcomes. Breast cancer studies should use race/ethnicity and income as covariates when analyzing their data to contribute to our understanding of how disparities affect outcomes. While nurses cannot alter the biology or many of the risk factors related to the development of breast cancer, they can help women adhere to screening and their treatment, identify and manage associated symptoms, and empower women in culturally sensitive ways to live their lives after their cancer.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Katherine E Reeder-Hayes, Email: kreeder@med.unc.edu, Division of Hematology/Oncology, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH), Member, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, UNC-CH, 170 Manning Drive Campus Box 7305, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, Phone (919)966-7828/Fax (919)966-6735.

Stephanie B Wheeler, Email: stephanie_wheeler@unc.edu, Department of Health Policy, Gillings School of Global Public Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Member, Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, UNC-CH, Cecil G Sheps Center for Health Services Research, UNC-CH, 1103C McGavran Greenberg Hall, CB#7411, 135 Dauer Drive, Chapel Hill NC 27599-7411. Phone 919.966.7374/Fax 919.843.6362.

Deborah K. Mayer, Email: dmayer@unc.edu, School of Nursing, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Director of Cancer Survivorship Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, CB 7460, Chapel Hill, NC 27599, Phone (919)843-9467.

References

- 1.DeSantis C, Ma J, Bryan L, Jemal A. Breast cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):52–62. doi: 10.3322/caac.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina breast cancer study. JAMA. 2006;295(21):2492–502. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chlebowski RT, Chen Z, Anderson GL, et al. Ethnicity and breast cancer: factors influencing differences in incidence and outcome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(6):439–48. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Demicheli R, Retsky MW, Hrushesky WJ, Baum M, Gukas ID, Jatoi I. Racial disparities in breast cancer outcome: insights into host-tumor interactions. Cancer. 2007;110(9):1880–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grunda JM, Steg AD, He Q, et al. Differential expression of breast cancer-associated genes between stage- and age-matched tumor specimens from African- and Caucasian-American women diagnosed with breast cancer. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:248. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quan L, Hong CC, Zirpoli G, et al. Variants of estrogen-related genes and breast cancer risk in European and African American women. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(6):853–64. doi: 10.1530/ERC-14-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller JW, King JB, Joseph DA, Richardson LC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Breast cancer screening among adult women--behavioral risk factor surveillance system, United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(Suppl):46–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee M, George J, Yee C, Hryniuk W, Schwartz K. Disentangling the effects of race on breast cancer treatment. Cancer. 2007;110(10):2169–77. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bickell NA, Wang JJ, Oluwole S, et al. Missed opportunities: racial disparities in adjuvant breast cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(9):1357–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bustami RT, Shulkin DB, O'Donnell N, et al. Variations in time to receiving first surgical treatment for breast cancer as a function of racial/ethnic background: a cohort study. JRSM Open. 2014;5(7):2042533313515863. doi: 10.1177/2042533313515863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magai C, Consedine NS, Adjei BA, Hershman D, Neugut A. Psychosocial influences on suboptimal adjuvant breast cancer treatment adherence among African American women: implications for education and intervention. Health Educ Behav. 2008;35(6):835–54. doi: 10.1177/1090198107303281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weekes CV. African Americans and health literacy: a systematic review. ABNF J. 2012;23(4):76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flockhart D. CYP2D6 genotyping and the pharmacogenetics of tamoxifen. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2008;6(7):493–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freedman RA, Hughes ME, Ottesen RA, et al. Use of adjuvant trastuzumab in women with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer by race/ethnicity and education within the National Comprehensive Cncer Network. Cancer. 2013;119(4):839–46. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerend MA, Pai M. Social determinants of black-white disparities in breast cancer mortality: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(11):2913–23. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program and the National Center for Health Statistics. [Last accessed 12/14/14];U S breast cancer incidence and mortality by race from 1991-2011. Available at http://www.cancer.gov/researchandfunding/snapshots/breast.

- 17.Anders CK, Johnson R, Litton J, Phillips M, Bleyer A. Breast cancer before age 40 years. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(3):237–49. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vogel VG. Epidemiology, genetics, and risk evaluation of postmenopausal women at risk of breast cancer. Menopause. 2008;15(4 Suppl):782–9. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181788d88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colditz GA, Baer HJ, Tamimi RM. Breast cancer. In: Schottenfeld D, Fraumeni JF Jr, editors. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2006. pp. 995–1012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peppercorn J, Perou CM, Carey LA. Molecular subtypes in breast cancer evaluation and management: divide and conquer. Cancer Invest. 2008;26(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/07357900701784238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin NU, Vanderplas A, Hughes ME, et al. Clinicopathologic features, patterns of recurrence, and survival among women with triple-negative breast cancer in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Cancer. 2012;118(22):5463–72. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anders C, Carey LA. Understanding and treating triple-negative breast cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2008 discussion: 1239-40, 43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowen RL, Stebbing J, Jones LJ. A review of the ethnic differences in breast cancer. Pharmacogenomics. 2006;7(6):935–42. doi: 10.2217/14622416.7.6.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, et al. Decision involvement and receipt of mastectomy among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(19):1337–47. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith GL, Shih YC, Xu Y, et al. Racial disparities in the use of radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery: a national Medicare study. Cancer. 2010;116(3):734–41. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reeder-Hayes KE, Bainbridge J, Meyer AM, et al. Race and age disparities in receipt of sentinel lymph node biopsy for early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128(3):863–71. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1398-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dragun AE, Huang B, Tucker TC, Spanos WJ. Disparities in the application of adjuvant radiotherapy after breast-conserving surgery for early stage breast cancer: impact on overall survival. Cancer. 2011;117(12):2590–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hershman DL, Wang X, McBride R, Jacobson JS, Grann VR, Neugut AI. Delay in initiating adjuvant radiotherapy following breast conservation surgery and its impact on survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(5):1353–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2006.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wheeler SB, Carpenter WR, Peppercorn J, Schenck AP, Weinberger M, Biddle A. Structural/organizational characteristics of health services partly explain racial variation in timeliness of radiation therapy among elderly breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133(1):333–345. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-1955-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alderman AK, Hawley ST, Janz NK, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of postmastectomy breast reconstruction: results from a population- based study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):5325–30. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griggs JJ, Hawley ST, Graff JJ, et al. Factors associated with receipt of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy in a diverse population-based sample. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3058–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.9564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wheeler SB, Carpenter WR, Peppercorn J, Schenck AP, Weinberger M, Biddle AK. Predictors of timing of adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with hormone receptor-negative, stages II-III breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;131(1):207–216. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1717-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fedewa SA, Ward EM, Stewart AK, Edge SB. Delays in adjuvant chemotherapy treatment among patients with breast cancer are more likely in African American and Hispanic populations: a national cohort study 2004-2006. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(27):4135–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griggs JJ, Culakova E, Sorbero ME, et al. Social and racial differences in selection of breast cancer adjuvant chemotherapy regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2522–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wheeler SB, Kohler RE, Reeder-Hayes KE, et al. Endocrine therapy initiation among Medicaid-insured breast cancer survivors with hormone receptor-positive tumors. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:603–610. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0365-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Partridge AH, Wang PS, Winer EP, Avorn J. Nonadherence to adjuvant tamoxifen therapy in women with primary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:602–606. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reeder-Hayes KE, Meyer AM, Dusetzina SB, Liu H, Wheeler SB. Racial disparities in initiation of adjuvant endocrine therapy of early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014;145:743–51. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2957-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hershman DL, Kushi LH, Shao T, et al. Early discontinuation and nonadherence to adjuvant hormonal therapy in a cohort of 8,769 early-stage breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4120–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Peairs KS, et al. Comparing care for breast cancer survivors to non-cancer controls: a five-year longitudinal study. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:469–74. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0903-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.White A, Pollack LA, Smith JL, Thompson T, Underwood JM, Fairley T. Racial and ethnic differences in health status and health behavior among breast cancer survivors--behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2009. J Cancer Surviv. 2013:93–103. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0248-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in quality of life after diagnosis of breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3:212–22. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0097-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matthews AK, Tejeda S, Johnson TP, Berbaum ML, Manfredi C. Correlates of quality of life among African American and white cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35(5):355–64. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e31824131d9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berger AM, Gerber LH, Mayer DK. Cancer-related fatigue: implications for breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118(8 Suppl):2261–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu HS, Harden JK. Symptom burden and quality of life in survivorship: a review of the literature. Cancer Nurs. 2015;38(1):E29–54. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Budhrani PH, Lengacher CA, Kip KE, Tofthagen C, Jim H. Nurs Res Pract. 2014. Minority breast cancer survivors: the association between race/ethnicity, objective sleep disturbances, and physical and psychological symptoms; p. 858403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wright JL, Takita C, Reis IM, Zhao W, Lee E, Hu JJ. Racial variations in radiation-induced skin toxicity severity: data from a prospective cohort receiving postmastectomy radiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2014;90:335–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alfano CM, Smith AW, Irwin ML, et al. Physical activity, long-term symptoms, and physical health-related quality of life among breast cancer survivors: a prospective analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1(2):116–28. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0014-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith AW, Reeve BB, Bellizzi KM, et al. Cancer, comorbidities, and health-related quality of life of older adults. Health Care Financ Rev. 2008;29(4):41–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blinder VS, Norris VW, Peacock NW, et al. Patient perspectives on breast cancer treatment plan and summary documents in community oncology care : a pilot program. Cancer. 2012;119:164–72. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ. The impact of sociodemographic, treatment, and work support on missed work after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;119(1):213–20. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0389-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanez B, Thompson EH, Stanton AL. Quality of life among Latina breast cancer patients: a systematic review of the literature. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5(2):191–207. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0171-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lopez-Class M, Gomez-Duarte J, Graves K, Ashing-Giwa K. A contextual approach to understanding breast cancer survivorship among Latinas. Psychooncology. 2012;21(2):115–24. doi: 10.1002/pon.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burhansstipanov L, Dignan M, Jones KL, Krebs LU, Marchionda P, Kaur JS. Comparison of quality of life between native and non-native cancer survivors: native and non-native cancer survivors' QOL. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(1 Suppl):S106–13. doi: 10.1007/s13187-012-0318-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weiner D, Burhansstipanov L, Krebs LU, Restivo T. From survivorship to thrivership: Native peoples weaving a healthy life from cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2005;20(1 Suppl):28–32. doi: 10.1207/s15430154jce2001s_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wen KY, Fang CY, Ma GX. Breast cancer experience and survivorship among Asian Americans: a systematic review. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(1):94–107. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0320-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang JH, Adams I, Huang E, Ashing-Giwa K, Gomez SL, Allen L. Physical distress and cancer care experiences among Chinese-American and non-Hispanic white breast cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;124(3):383–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kaur JS, Coe K, Rowland J, et al. Enhancing life after cancer in diverse communities. Cancer. 2012;118(21):5366–5373. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]