Abstract

This paper extends theory and research concerning cultural models of development beyond family and demographic matters to a broad range of additional factors, including government, education, human rights, daily social conventions, and religion. Developmental idealism is a cultural model—a set of beliefs and values—that identifies the appropriate goals of development and the ends for achieving these goals. It includes beliefs about positive cause and effect relationships among such factors as economic growth, educational achievement, health, and political governance, as well as strong values regarding many attributes, including economic growth, education, small families, gender equality, and democratic governance. This cultural model has spread from its origins among the elites of northwest Europe to elites and ordinary people throughout the world. Developmental idealism has become so entrenched in local, national, and global social institutions that it has now achieved a taken-for-granted status among many national elites, academics, development practitioners, and ordinary people around the world. We argue that developmental idealism culture has been a fundamental force behind many cultural clashes within and between societies, and continues to be an important cause of much global social change. We suggest that developmental idealism should be included as a causal factor in theories of human behavior and social change.

Keywords: Development, Modernization, Developmental Idealism, Cultural Models, Social Change, Globalization

“Culture lies at the heart of world development” (Boli & Thomas 1999:17).

Introduction

In a 2001 paper and a 2005 book, Arland Thornton introduced the concept of developmental idealism, a widespread and powerful cultural model constituted of a set of beliefs and values about development, including its causes and consequences. The cultural model of developmental idealism emerged from a long history of developmental thinking among Western scholars and other elites. Among the central values of this cultural model, Thornton posited, were the desirability of a modern society, modern family behavior, and freedom and equality. A central tenet of developmental idealism was the belief that modern social structures and modern family behaviors have reciprocal causal influences. Thornton further discussed how the values and beliefs of developmental idealism have spread across the world through numerous mechanisms, and how they have had an enormous influence on family change.

Subsequent empirical research has buttressed and expanded these basic arguments about developmental idealism and its influence on family matters. This growing research has shown that the beliefs and values of developmental idealism have spread not only to the world's rich and powerful individuals and large international organizations, but to the citizens of many countries throughout the world (Abbasi-Shavazi et al. 2012; Binstock and Thornton 2007; Binstock et al. 2013; Lai and Thornton 2014; Melegh et al. 2013; Thornton et al. 2012a; 2012b; 2014a; 2014b; Xie et al. 2012). This new research has also provided additional insights about how the spread of developmental idealism has affected many aspects of family behavior, including gender roles, marriage, childbearing, living arrangements, and divorce (Allendorf 2013; Allendorf and Thornton forthcoming; Cammack and Heaton 2011; Kavas and Thornton 2013; Pierotti 2013; Thornton and Philipov 2009; Thornton 2010; Yount and Rashad 2008).

It has also become clear in recent years that the influence of developmental idealism extends far beyond family life, to government, education, human rights, daily social conventions, and religion. For example, Kavas (2015) demonstrated how developmental idealism has influenced changing clothing styles in Turkey, and Thornton and colleagues (2014) have found acceptance for developmental idealism beliefs about freedom, democracy, and human rights among people in three Middle Eastern countries, where one might expect considerable resistance to foreign ideas (e.g., Huntington 1996).

This paper provides a general extension of the cultural model of developmental idealism and reformulates some of the basic values and beliefs contained within the model in order to take into account this extension. In particular, we extend the values and beliefs contained in developmental idealism beyond family matters to include numerous other values and beliefs. We discuss how the globalization of developmental idealism has affected many things around the world, including modes of production, education, international relations, clothing styles, human rights, gender equality, marriage, childbearing, and views of global hierarchies.

In this paper we analyze developmental idealism (hereafter DI) as a cultural model encompassing numerous values and beliefs that are held by many individuals and groups the world over. The DI cultural model encompasses the goals, rationales, and preferences for the individuals and groups under its influence. As such, DI provides guidance and motivation for decisions and actions. We also argue that the DI cultural model should be included as a causal force in scholarly scientific theories explaining human action and social change. We posit that the DI cultural model has spread widely around the world where, in combination with material conditions, demographic characteristics, and other values and beliefs, it both influences the decisions and behaviors of individuals and contributes to social change.

In the next section, we examine the origins and content of DI, discussing how its key elements have persisted over time even while some elements of the DI cultural model continue to vary across time, place, and individuals. Next we discuss how DI permeates the agendas and programs of agents of development and social change. The following section discusses several mechanisms for the spread of DI, and considers some of the consequences of its global dissemination, focusing on numerous dimensions of life, including family and demographic behavior, perceptions of hierarchy and inequality, education, modes of production, and international relations. The final section provides conclusions.

Before proceeding, we emphasize several features of our approach. We recognize that in the complex and multi-causal world in which we live, DI is not the only force affecting human behavior and social change. However, our position is that DI, among other forces, is often a crucial influence and for this reason should be considered in explanations of social change around the world.

We also emphasize that we neither advocate for, nor argue against, the DI cultural model. We take no position concerning the truth of DI beliefs or the merits of its values. Likewise, we are agnostic regarding whether the globalization of this cultural model has benefited or harmed people. We are interested only in the cultural features of DI, how it has been disseminated, how it influences human behavior, and how it has been a factor in cultural clashes and social change.

We note that space limitations prevent full discussion of the details and varieties of DI, its dissemination mechanisms, the clashes and resistance it produces, and the social changes it influences. Instead, we cover the main points and leave others for future discussion. Some areas of our paper are more extensively conceptualized and researched than others. In some places we present conclusions; in others we present hypotheses; for all we advocate additional research.

The Origins and Content of Developmental Idealism

Developmental Idealism as a Cultural Model

Developmental Idealism is like other cultural models in that it tells people both how the world works and how they should live in the world (D'Andrade 1984; Fricke 1997a, 1997b; Frye 2012; Geertz 1973; Johnson-Hanks et al. 2012; Vaisey 2009). As a cultural model of how the world works, DI comprises a system of beliefs that account for the nature of the world and how it changes. DI also includes beliefs about the causes and consequences of various individual and social phenomena, such as the accumulation of wealth, the achievement of education, the adoption of democracy, and the formation of marriages and families. These DI beliefs are often taken for granted as unquestioned “truths” or commonsense understandings about the world.

DI is also like other cultural models in that it helps people make sense of the world by specifying desirable end-states, including the most effective and legitimate means by which these goals should be pursued (Johnson-Hanks et al. 2012; Shanahan and Macmillan 2008; Taylor 2004; Thornton et al. 2001).1 That is, DI delineates the nature of the good life – including the material goods, social arrangements, and societal goals that should be achieved. These DI values generate motivations and aspirations for individual, group, nation-state, and even world-wide decisions and behavior. Also, DI provides guidance, sometimes in the form of prescriptions, regarding how to achieve the good life.

Cultural models of and for the world are usually associated with particular places, times, or people—such as Japanese culture, 17th century Navajo culture, pre-Revolution Russian culture, and Maasai culture. DI, however, is not directly associated with any particular time, place, or people, but rather with the powerful ideas of development and modernity, which are assumed to span historical time and geography. As such, DI is promulgated as a universal cultural model, generalizable in terms of its scope, relevance, and application.

However, as we explain below, DI is actually very Eurocentric. Many DI tenets derive from the cultures of northwest Europe, which historically have been placed at the apex of development in the DI cultural model. For example, within DI, northwest European societies are understood to be the positive endpoint of development, the model of the good life, and a powerful marker of the correct direction for social change. Though Western in its origins and content, the globalization of DI has subsumed all societies, including Western societies, under a universal set of expectations and global norms of development that is perceived to apply to all societies. An important consequence of the globalization of this model is that it provides societies outside of northwest Europe or the West with a globally sanctioned model by which to judge not only their own progress toward development, but also a model by which to judge and criticize Western countries. This is a significant development because it suggests that DI is not simply ‘Westernization’ by another name, but rather a foundational element of global culture to which all nations are expected to conform.

We follow current thinking on cultural theory in positing that culture is not necessarily an overwhelming and monolithic set of rules and demands so much as a toolkit of scripts and schemas that people use in making decisions about behaviors and relationships (Collett and Lizardo 2014; Sewell 1992; 2005; Swidler 1986; Vaisey 2009). That is, cultures are composed of schemas, scripts, values, and beliefs, which vary in their endorsement depending on time, place, and social context. So, for example, just as Chinese and American cultures have many varieties, the DI cultural model varies in its manifestations (Allendorf and Thornton forthcoming). DI is an omnibus cultural model whose varieties comprise different elements in different combinations and strengths.

Origins and Evolution of Developmental Idealism

Some of the essential components of the cultural model of developmental idealism can be traced back to the classical writings of the Greeks and Romans, who compared human societies to biological organisms whose development involved birth, growth, adulthood, decline, and death (Nisbet 1969; Pagden 1982; Thornton 2005). As with biological organisms, this pattern was seen to be the same for each society, although the pace varied. Saint Augustine and later Christians made an important modification to this classical developmental model by applying it to the overall history of mankind (Mandelbaum 1971; Nisbet 1969; Pagden 1982).

This model of societal development was reconceptualized in the 17th century when “the metaphor of genesis and decay was stripped....of its centuries-old property of decay leaving only genesis and growth” (Nisbet 1969:109). This more optimistic view, which can be seen in the writings of Hegel (Hegel 1878/1837), Condorcet (N.d./1795), Godwin (1926/1793), and others, posited that future societies were not destined to follow the biological life cycle, but rather were likely to progress continually from low development, which was viewed negatively, to high development, viewed positively. Although some people continued to espouse the rise-and-fall model (e.g., Malthus 1986/1803), the societal progress model gained substantial endorsement from the mid-18th century onward.

Developmental models were common among influential writers of the 17th- and 18th-century Enlightenment (Condorcet N.d./1795; Ferguson 1980/1767; Hobbes 1991/1642; Locke 1988/1690; Malthus 1986/1803; Millar 1979/1779; Smith 1937/1776) and in the social scientific writings of the 19th and early 20th centuries (e.g., Comte 1858/1830-42; Durkheim 1984/1893; Marx and Engles 1965/1848; Spencer 1851; Tylor 1871; Westermarck 1891). These writers argued that all societies pass through relatively uniform stages of development from less to more developed, albeit at different speeds. Consequently, at any given moment in historical time, societies could be conceptualized as constituting a continuum or hierarchy of development ranging from less to more advanced (Lerner 1958; Mandelbaum 1971; Nisbet 1969). The populations of northwest Europe, including northwest Europe's overseas populations in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, were posited to be the most advanced societies and the standard by which to locate all other societies on the developmental continuum. The more different a society was from northwestern Europe in terms of cultural practices, technological sophistication, and social institutions, the less developed it was perceived to be by social thinkers of the day (Tylor 1871). This idea of a developmental hierarchy with northwest Europe and its overseas populations at the apex was reinforced by the substantial, and for many years, growing cross-national economic inequality (Firebaugh 2006; Korzeniewicz and Moran 2010). This viewpoint continues today, with many rankings of international development placing northwest Europe and European-origin countries at the top level of development, although other places, such as Japan, are now seen as close to the top (e.g., United Nations Human Development Index). Belief in a developmental social hierarchy is a key element of the DI cultural model.

Scholars created multiple structures for conceptualizing, dividing, and naming their stages of development. Three such schemas that have emerged include: 1) the general three-stage model from savagery to barbarism to civilization; 2) the Scottish enlightenment construct with four stages from hunting to herding to agriculture to commerce; and 3) the Marxist scheme with its highest four stages from feudalism to capitalism to socialism to communism. The Marxist model was unusual in defining its last two stages as future developmental goals.

A key aspect of DI today is universality. All humans and societies are seen as having equal capability to develop and are therefore on the same developmental spectrum but at different stages of advancement. This sense of universality, however, emerged over time (Thornton 2005:22-25). As Europeans initially came into contact with large numbers of indigenous people around the world during the era of exploration, some concluded that certain of these native people were subhuman or had emerged through multiple human creations – and that they therefore had different amounts of developmental potential. However, these viewpoints were subsequently rejected in favor of the belief that all can progress on the same developmental path (Thornton 2005:24-25).

The identification of northwest Europe and its overseas populations with modernity has had substantial implications for the DI cultural model, most significantly the assumption that the attributes of northwest Europe are those that all societies must adopt to become developed or modern. As we discuss later, these attributes are not only considered modern but are also valued under developmental idealism. In Table 1 we list attributes identified with northwest Europe and modernity in the DI cultural model. These include national resources and social structures: wealth and health, technological sophistication, and an industrial and urban society. Also included are social institutions such as free and open markets, an educated citizenry, and democratic social and political institutions. The DI cultural model also defines certain social norms and values as modern: pluralistic norms and laws, an emphasis on the individual as compared to the family and community, universalism, freedom, equality, human rights, secularism (including the separation of church and state), and scientific-rational decision making. Other attributes DI defines as modern are individual and family arrangements associated with northwest Europe, including monogamy, marriages contracted at mature ages by the younger generation, planned and low fertility, gender egalitarianism, a high degree of personal autonomy and self-expression, and clothing styles of northwest Europe.

TABLE 1.

Attributes Associated with Modernity and Valued by Developmental Idealism

| National Resources and Social Structure |

| Wealth and health |

| Technological sophistication |

| Industrial and urban society |

| Social Institutions |

| Free and open markets |

| Educated citizenry |

| Democratic social and political institutions |

| Social Norms and Values |

| Pluralistic norms and laws |

| An emphasis on the individual, rather than family and community |

| Universalism |

| Freedom |

| Equality |

| Human rights |

| Secularism (including the separation of church and state) |

| Scientific-rational decision making |

| Individual and Family Arrangements |

| Monogamy |

| Marriages contracted at mature ages by the younger generation |

| Planned and low fertility |

| Gender egalitarianism |

| High degree of personal autonomy and self-expression |

| Clothing styles of northwest Europe |

NOTE: The listed items are not intended to be an exhaustive list of the elements of the DI cultural model, but rather, illustrative of its central features.

In addition, the belief in a uniform pattern of development and a single global developmental hierarchy made it easy for some scholars to believe that contemporary northwest European societies once resembled the indigenous populations in Australia, Africa, and America. For centuries this assumption was used as a basis from which to study family change in northwest Europe—only to have the conclusions over-turned when scholars used the historical record to study family change (Chakrabarty 2000; Hajnal 1965; Laslett and Wall 1972; Macfarlane 1979, 1986; Mandelbaum 1971; Nisbet 1969; Thornton 2005).

From a prospective vantage, this cultural model implies that as the indigenous populations of Africa, America, Australia, and Asia progress, they will eventually develop beliefs, values, social attributes, and behaviors similar to those of contemporary populations of northwest Europe. Because this model assumes a northwest European standard for modernity (Chakrabarty 2000; Wallerstein 1991), societies that deviate from progress toward northwest European characteristics (Table 1) may be seen as following either deficient or distorted development trajectories (Chakrabarty 2000; Melegh 2006).

An essential part of the cultural model of DI is reciprocal causation among the various aspects of modernity. Development theorists of the 19th and 20th centuries formulated and refined many explanations of how some social, demographic, economic, technological, familial, and political dimensions of modern life were both causes and consequences of other dimensions of modernity. Many of these explanations were subsequently incorporated into the DI cultural model as taken-for-granted truths rather than as theories in need of empirical validation. A key example of such causal explanations is that industrialization and increased economic productivity facilitate democracy, secularization, fewer marriages, and smaller families (Bhagwati 2004; Inglehart and Welzel 2005; Williamson 1990; Wolf 2004). And perhaps even more important are causal beliefs about the factors that help facilitate economic development. Scholars in the 19th and 20th centuries identified factors such as education (Becker 1964; Psacharopoulos 1994), democracy (Bollen 1979; Burkhart and Lewis-Beck 1994; Lipset 1959; Rostow 1971; Wejnert 2005), gender equality (Rathgeber 1990; Moser 1993; Nussbaum 2002), and smaller families (Coale and Hoover 1958; Kirk 1944; 1996; Notestein 1945) as positive influences on economic development.

The DI explanations of the causes of economic development tell actors what is necessary to achieve a modern society. These explanations are likely to motivate DI followers to make changes in the factors assumed to increase economic development, regardless of whether or not the explanations are valid.

The explanations about the consequences of economic development are also powerful elements of the DI model because they motivate actors to accept outcomes believed to be associated with economic progress that might otherwise be viewed as suboptimal or even unacceptable. People may moderate their opposition to such outcomes because they assume these changes are the natural, even inevitable, consequences of economic development. In this way, the DI beliefs about the consequences of economic development contribute to social change.

These DI beliefs are reinforced by the observed world. Many people recognize that individuals living in societies defined as economically modern tend to live longer, healthier lives and enjoy a wide range of sophisticated technologies viewed as modern, while also having smaller families, older ages at marriage, and greater education, democracy, and human rights. It is then a short step to accept the DI tenet of reciprocal causal associations between economic development and other elements of modern life and society.

DI also includes powerful value statements that explicitly define many of the characteristics of northwest Europe as not only modern, but beneficial and preferable to characteristics found elsewhere. In many ways, DI takes for granted that the attributes defined as modern in Table 1 are also worthwhile objectives. DI subscribers use terminology such as ‘developed,’ ‘progressive,’ ‘civilized,’ ‘polished,’ and ‘advanced’ to describe modern elements of society, and terms such as ‘backward,’ ‘barbaric,’ ‘uncivilized,’ ‘under-developed,’ ‘less-developed,’ ‘primitive,’ and ‘pre-modern’ to describe those that stand in contrast or opposition to modernity (Swindle 2014). Thus, in some ways modernity is a liberal humanitarian utopia as described by Karl Mannheim (Melegh 2006).

Although the content of developmental idealism largely originated in the West, it is more than just the values and beliefs of the West concerning a range of societal attributes. It is the linkage of those values and beliefs to a global model of development that defines the good life as modern and universal rather than local and particular. DI also integrates the values and beliefs of the West with a universal prescription of how Western values and beliefs are causes and consequences of global development, giving those beliefs and values particular power around the world.

Despite the link between northwest European societies and modern social life that historically has been a key part of DI, this connection appears to be weakening. Cultural values and beliefs that originated from northwest Europe have taken on a life of their own as global cultural models of modernity. These models subsume the West along with the rest of the world under a common model, and non-Western countries employ the logic of DI to critique Western countries. For example, many countries criticize the United States for its refusal to sign international treaties regarding child's rights or to legislate maternity leave benefits for women. Despite their historically privileged status, the United States and other Western societies are no longer the sole authors of global cultural models of modernity; rather they now face some of the same pressures that non-Western societies experience from these global cultural models.

Key Propositions of Developmental Idealism

In Thornton's original work, he distilled five basic propositions regarding DI (Thornton 2005:136-146). The first was that “modern society is good and attainable,” with “modern society” meaning such things as “industrial production, urban life, high levels of education, and rapid transportation and communication systems.” The second proposition was that “the modern family is good and attainable,” with “modern family” meaning “a social system with many nonfamilial elements, extensive individualism, many nuclear households, older and less universal marriage, extensive youthful autonomy, marriage largely arranged by the couple, affection in mate selection,.....high regard for women's autonomy and rights.....[and] low and controlled marital fertility”. The third was that “the modern family is a cause as well as an effect of a modern society. The fourth was that “individuals have the right to be free and equal, with social relationships being based on consent.” The fifth proposition of DI identified by Thornton—“modern political systems are good and attainable,” with “modern political systems” meaning “those that emphasize freedom, liberty, and the consent of the governed”—received little emphasis because his primary focus was on family issues.

Whereas Thornton's earlier distillation of the content of developmental idealism identified five main propositions, here we condense and distill three more general DI propositions—one value proposition and two belief propositions. Our value proposition continues the wording of Thornton's original first proposition that a “modern society is good and attainable,” but we emphasize a more expansive definition of “modern society.” We now include in the definition of “modern society”, all of the elements that Thornton originally labeled “modern society”, “modern family”, “modern political systems”, and freedom, equality, and consent, but we now add into the definition of “modern society” the following elements: free and open markets, democratic social and political institutions, pluralistic norms and laws, human rights, secularism (including the separation of church and state), and scientific-rational decision-making. The attributes we identify as comprising a “modern society” in this DI proposition in contemporary times are listed in Table 1, although, as we discuss below, we recognize that any such list would vary given the existence of assorted DI “packages” and “multiple modernities” (Eisenstadt 2000).

Our first DI belief proposition summarizes a general view of development: societies are at different levels of development and move from traditional to modern. The second DI belief involves interconnections between components of DI: many of the elements of modern society have reciprocal cause and effect relationships. This belief statement thus expands Thornton's original third proposition that “the modern family is a cause as well as an effect of a modern society” to include many other components of modernity in DI. We do not specify all possible belief statements about causal interrelationships, but list examples in Table 2, including some focused on the consequences of economic development, some focused on the causes of economic development, and some focused on causal relations among education, gender equality, and fertility.

TABLE 2.

Examples of Causal Belief Statements within Developmental Idealism

| Consequences of Economic Development |

| Economic development helps produce democracy |

| Economic development helps fertility to decline |

| Economic development helps education to expand |

| Causes of Economic Development |

| Democracy facilitates economic development |

| Education facilitates economic development |

| Planned and low fertility facilitates economic development |

| Personal freedom facilitates economic development |

| Gender equality facilitates economic development |

| Other Causes and Consequences |

| Education facilitates gender equality |

| Gender equality facilitates education |

| Small families facilitate education |

NOTE: The belief statements listed above are intended to be an illustrative list of the causal belief statements within the DI cultural model, rather than an exhaustive list.

The original formulation of DI by Thornton (2001, 2005) suggested that the various elements of DI came as a “package” – implying tight interconnections and limited variation across time and place. Here, however, we follow the revision of Allendorf and Thornton (forthcoming) that DI comes in varieties. While it is the case that DI values and beliefs can be tightly connected in people's minds,2 it is also true that they are sometimes only loosely connected or sometimes not at all connected. In this alternative conceptualization, DI is similar to other cultural models such as the Chinese culture or the American culture, which exist in different formats across geography and history. Consequently, the exact value and belief statements included in the propositions of developmental idealism can vary across time, place, and individuals.

The notion that the DI cultural model varies across places, times, and individuals is similar to the idea proposed by Eisenstadt (2000) of alternate modernities. Sometimes the differences between DI versions are fairly small and other times more substantial. Examples of such differences include the substitution of ‘good governance’ for ‘democracy’ in the development strategies of some Muslim-majority countries (Thornton et al. 2014a), the implementation of the Marxist developmental model in Russia and China, and the protectionist, state-driven, capitalist model being practiced in many countries of eastern Asia (Chang 2002). These multiple versions of DI or alternative modernities are sometimes encapsulated in societies that see themselves as rivals that compete with each other for resources and legitimacy (Melegh 2006). In addition, aspects of DI are always under debate, such as those that take place today at international conferences and global summits of world leaders. Irrespective of their diversity and competition, however, all versions of DI share values and beliefs about the desirability of modern life and society and similar concepts of development unfolding in stages.

Although DI generally links modernity to societies of northwest European ancestry, these societies have changed substantially over the past several hundred years. This makes it likely that some DI versions look to northwest European attributes of the 19th century while others favor those of the 20th or 21st centuries. Some of the changes in northwest Europe and its overseas populations, such as increased divorce and increased sex, cohabitation, and childbearing outside marriage, are disliked and absent from many DI model variations (Thornton 2005). In fact, in a number of societies these attributes are labeled ‘Western’ instead of ‘developed,’ and are strongly rejected.

Developmental Idealism in Global Development Programs and Policies

We now turn to the embedding of developmental idealism in global development programs and policies. We begin with Christian churches because they stand among the earliest substantial, organized, and systematic attempts to ‘civilize’ the world, and, of course, to also ‘Christianize’ it. With an agenda of global social change, Christianity has played a significant role in the diffusion of DI.

Today, Christianity has spread to nearly every region of the world. For centuries, Christian missionaries have established both churches and schools, through which they have evangelized many cultural features of Western society, such as individualism (personal salvation through grace and works), personal freedom (ability to choose right and wrong), and universality (all people are children of God and should accept Christianity) (see Meyer 1989). Woodberry (2012) documented the importance of these missionaries by showing a strong and robust relationship between the historical prevalence of Protestant missionaries and the later spread of democracy across nation-states. Christian missionaries were also the first to form long-distance advocacy and humanitarian organizations (Barnett 2011; Dromi 2014; Stamatov 2010; 2013). In the 20th century, leaders of Christian churches were very influential in the founding of the United Nations (Tarr 1975) and other powerful international organizations (Barnett 2011), and today many sponsor both small and large international nongovernmental organizations (Boli and Thomas 1997; 1999; Schnable 2014; Wuthnow 2009).

Despite the increasing importance of NGOs and INGOs in the global diffusion of DI today, Christian churches continue to be one of the primary and most effective mechanisms through which DI beliefs and values are spread (Berger 2008; Swidler 2013). Protestant churches generally champion values of individualism, autonomy, freedom, and achievement, and denigrate values of collectivism and extended kinship obligations. One well-documented example of this involves the influence of the Prosperity Gospel movement in Pentecostal churches across Latin America and Africa (Coleman 2000; Daswani 2011; Manglos 2010).

DI is also embedded in, and spread by, international development projects that have become more prevalent since the post-World War II expansion of the global development field. Common goals of these projects include stimulating national economic growth, increasing educational achievement, improving health, reducing population growth, and promoting personal freedom and human rights. International development projects are conducted by different types of organizations, including intergovernmental organizations like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund; foreign aid agencies like the U.S. Agency for International Development and the United Kingdom's Department for International Development; international nongovernmental organizations like CARE or Amnesty International; social business ventures such as Kiva.org and the Skull Foundation; and social responsibility initiatives conducted by large corporations like Coca-Cola and Verizon as well as by small boutique businesses that “give back” a percentage of their profits.

Individual actors and groups that describe their work and volunteer efforts as international development projects are yet another vehicle for the spread of DI. Actors of this nature, whom Jackson (2005) labels “globalizers,” include people on humanitarian mission trips, on alternative spring break excursions, and in the Peace Corps, to name a few. Many people engage in such projects around the world; Wuthnow (2009), for example, estimates that 20-25% of American churchgoers have been on at least one short humanitarian mission trip to another country at some point in their lives (see also Trinitapoli and Vaisey 2009; Wuthnow and Offutt 2008).

Though they often focus on spreading the specific cultural practices and values associated with particular development projects, implementers of such projects often spread other elements of DI in indirect ways. Their observable foreignness to the place they are visiting – their dress, their marketplace decisions, their social behaviors – are likely to be associated with DI values and beliefs by local observers.

Organizations and individuals enacting international development projects often emphasize how their definition of societal development is better and more “true” than the definitions espoused by others, leading to seemingly endless debates among development scholars, professionals, and do-it-yourself humanitarians alike over what constitutes the best approach to societal development. Debates over the definition of development and preferred policy proscriptions are evident in recent debates involving the modification or replacement of the millennium development goals (United Nations 2013). These various strands of development theory are unique in some ways, but few if any challenge the core tenets of developmental idealism. This is true of virtually all individuals and organizations working in the international development arena: though they vary in the particulars of their purposes and definitions of what constitutes development, they share a common understanding of the value of development and progress in and of itself.

Dominant theories of development in the mid-20th century revolved around the notion of “modernization,” whereby societal development was an assumed consequence of economic growth (e.g., Rostow 1961; 1970). Modernization theory has had prominent influence on the types of international development projects implemented by foreign aid agencies and nongovernmental organizations (Cooper and Packard 1997; Engerman et al. 2003; Gilman 2003; Latham 2000; Mitchell 2000).

Beginning in the late 1960s, dependency theorists critiqued modernization theory, arguing that most international development policies should be rejected because they further acerbate global inequalities through various mechanisms of unequal exchange (e.g., Frank 1966). These critiques eventually helped to undermine the focus of international development programs on assisting national governments directly. This created a window of opportunity for new approaches to development in the 1980s. The idea of promoting economic growth via free markets, which had gained popularity in domestic politics circles in England, the United States, and other wealthy nations during this time, quickly gained popularity as a development strategy. This neoliberal approach to development was most prominent in the late 1980s and the 1990s (e.g., Burnside and Dollar 2000; Williamson 1990), though it continues to be a common approach to development today.

During the 1990s and into the 2000s, several prominent economists involved in development policy debates began to question the assumption that national economic growth would inevitably transform a society in ways they perceived to be desirable. In particular, these development economists questioned the notion that national economic growth in fact causes greater levels of democracy, personal freedoms, human rights, educational achievement, and improved health (Hicks and Streeten 1979; Sen 1989; Streeten 1994). Led by Amartya Sen, they theorized that what matters for development are “substantive freedoms,” which they argued constitute both the means and the ends of development (e.g., Deneulin and Stewart 2002; Nussbaum 2000; 2011; Robeyns 2005; Sen 1989; 1999).

Sen's “capability approach,” as well as his elaboration of “human development,” has had a prominent influence on the global development field, inspiring the formation of new international development projects that focused on more than generating economic growth, and instead on a variety of other realms of social life, such as politics, social equality, and culture. Based largely on Sen's work, the United Nations in 1990 created the Human Development Index (HDI), a scale of societal development that takes into account education, health, and economic outcomes for each country in the world (Wherry 2004).

In more recent years, the concept of “sustainable development” has gained favor. One articulation of this approach emphasizes the importance of environmental preservation and ecological diversity alongside the more common socioeconomic development goals (Ackerman 2009; World Commission on Environment and Development 1987; UN 2011). In another articulation, sustainable development refers to projects that “help people to help themselves” by refraining from providing goods outright (which some development workers critically refer to as “Santa Claus development”) in favor of stimulating self-generating development through participatory trainings and public discussion about local solutions to the challenges that surround them (i.e. Chambers 1997; for critical reviews of this theory, see Hickey and Mohan 2005; Swidler and Watkins 2009). And in yet another articulation, sustainability refers more generally to whether the social changes brought about by a particular development project will continue after the organization behind the project leaves (Warburton 1998). Each of these versions of sustainability is currently promoted, and most recently it has been proposed that sustainability be placed at the core of national and international development policies and programs (United Nations 2013).

These approaches to sustainable development were constructed in response to political activism and critiques of established development theories. The ecological version rose alongside heightening concern over global climate change and critiques of the industrial development priority of economic development efforts. The self-development model arose after repeated reports of foreign aid corruption and the general trend toward neoliberal politics worldwide. And the concern for the durability of social changes once development projects ended came about due to a rising belief that development aid has few long-term effects. Although promoters of sustainable development confronted previous ideas about how to achieve development, they did not question the value of pursuing development. The same is true of those who promote other recent theories of development, including, but not limited to, institutional economics (Acemoglu and Robinson 2012; Rodrik 2004), rights-based development (Häusermann 1998; Sano 2000), and protectionism (Chang 2002; Kohli 1994); all critique pre-existing theories of development without challenging the fundamental goal of development itself.

Beginning in the 1990s, a small number of self-labeled “post-development” scholars challenged the wisdom of mounting any global development programs or policies (Dinerstine and Deneulin 2012; Escobar 1995; 2008; Ferguson 1994; Rist 2002/1997; Sachs 1992), arguing that development efforts impose the values and beliefs of “donor” societies onto “recipient” societies. Moreover, they claimed that many development projects negatively impact the lives of development aid recipients.

It is our position that even these post-development scholars inject their own vision of a “good” society into their social theories. While not labeling their theories as developmental, they are strikingly similar in the sense that they involve values and beliefs regarding collective well-being and social progress (e.g., Escobar 2008). Public programs and policies inspired by “post-development” theory are similar in this regard. In Latin America, for example, the notion of “buen vivir” or “living well” has recently gained political power (Acosta 2008; Walsh 2010), where it has come to signify an ecologically balanced, community-centric, and culturally sensitive approach. While proponents of this worldview emphasize its difference from other development theories, the key elements of “buen vivir” have a familiar ring and the ideas of progress and universalism remain central. For this and similar alternative movements, the central critique of mainstream development theory and practice is its emphasis on global capitalism for producing a socially just world.

These myriad approaches to development serve as mechanisms for the diffusion and influence of DI. Public and scholarly debate about which theory of development “works” (e.g., Banerjee and Duflo 2011; Easterly 2006; Moyo 2009; Sachs 2005) brings more attention to development theories, furthering the spread and power of the key elements of DI. This occurs despite the lack of agreement surrounding the precise definition of development and the preferred means for achieving it. And, importantly, these debates are based on the assumption that a universal model of development, societal progress, or human well-being exists, is possible, and should be actively pursued.

The Spread and Effects of Developmental Idealism

We now shift our attention from the culture of developmental idealism, including its features, varieties and embeddedness in global development programs to the spread of DI and the consequences of that spread. We earlier described the origins of DI among the elites of northwest Europe and its overseas populations. Here we discuss mechanisms for its spread from these origins to the general populations of these northwest European ancestry nations and to numerous other societies around the world. We then discuss some of the many effects of the globalization of DI, including: a) effects on national governments, policies, programs, and laws; b) effects on individuals’ values and beliefs; and c) effects on individuals’ behavior.

Mechanisms for the Spread of Developmental Idealism

The spread of DI within and across societies has been facilitated by a large and diverse set of mechanisms, which include the global development efforts previously discussed. We list the various mechanisms we have identified in Table 3 – grouped into three categories: transnational actors; programs, movements, and institutions; and transnational flows and interactions. Among transnational actors, we include Christian missionaries, the United Nations, governments, nongovernmental organizations, Western businesses, and writings of developmental scholars. Among programs, movements, and institutions that disseminate DI, we identify mass education, mass media, family planning programs, foreign aid programs, and social movements for such things as communism, civil rights, democracy, and women's equality. Transnational flows and interactions that spread DI are European and American exploration, Western colonization, international conflicts, and tourism.

TABLE 3.

Mechanisms for the Spread of Developmental Idealism

| Transnational Actors |

| Christian missionaries |

| United Nations |

| Governments |

| Nongovernmental organizations |

| Western businesses |

| Writings of developmental scholars |

| Programs, Movements and Institutions |

| Mass education |

| Mass media |

| Family planning programs |

| Foreign aid programs |

| Social movements (e.g., communism, civil rights, democracy, women's equality) |

| Transnational Flows and Interactions |

| European and American exploration |

| Western colonization |

| International conflicts |

| Tourism |

NOTE: The list above is meant to be illustrative, not exhaustive, of the mechanisms for the spread of DI.

The prominence of each of these mechanisms in the spread of developmental idealism has varied historically, geographically, and by the tenets of DI. In addition, at some times and places only one or two elements of DI were subject to dissemination, while more expansive dissemination occurred at other times. This variation can be attributed to cultural and structural differences in the places where DI is being disseminated, differences in the intentions of purveyors of DI – for instance, colonization versus family planning programs – and differences in the effectiveness of particular mechanisms in cross-national and within-country dissemination.

We argue that the spread of developmental idealism has been facilitated by the power of its ideas and by the power of the people, organizations, and institutions embracing it. The ideas are powerful because they include a cultural model about the locus and composition of the good life and how to achieve it. Furthermore, this cultural model has credibility and legitimacy because it is consistent with the distribution of economic, political, technological, and military resources among the various nations of the world. Also, powerful supporters of DI have used their economic, political, technological, and military resources to encourage the adoption of DI through numerous means, including force.

Colonization often brought the forced implementation of aspects of the DI cultural model, as can be seen in parts of the Americas. Resistance to colonization was also a powerful force for the adoption of DI in such places as China, Japan, and Turkey. In addition, governments can force DI on its own people, as was seen in the family planning programs of China and India.

In other cases, DI has been fostered from within by a variety of means. In China, Japan, Turkey, and among the Native Americans of the Columbia Plateau (in what is now the northwestern United States) individuals journeyed to northwest European societies to obtain the knowledge and resources they believed to be useful to achieve personal and societal development. They also invited northwest Europeans to bring their ideas and resources to them. And, today numerous governments around the world energetically seek after development programs supported by northwestern European-origin nations and some new donors like Brazil, China, and India. Of course, even when the knowledge and resources of development are sought after, their implementation can involve coercion of various types.

As we discuss more fully below, DI can now be found in virtually every corner of the world, and in the non-Eurocentric places indigenous cultures had their own centuries-old beliefs and values concerning the way the world works and how to live in it. When the beliefs and values inherent in DI are inconsistent with those of indigenous cultures, which has often been the case, competing cultural models coexist and almost always have resulted in some official and unofficial resistance to DI. Even where governments, populations, and individuals are receptive to DI values and beliefs, they may also offer resistance to and adaptation of DI tenets during incorporation into local cultural norms and practices.

It is important to note that the results of the introduction of DI into a society are neither deterministic nor inevitable. The people exposed to DI are active participants in the process, as they make decisions about a range of possible actions, including resistance, adoption, and hybridization. People can also adopt certain elements of DI in order to preserve other elements of their culture, which may be seen by them as more central to their lives and identities (Miller 2006). Reactions to and the effects of DI can also vary substantially across groups and individuals within a society, producing substantial and long-lasting within-society disagreement and conflict (Walker 1985). The strength of DI and the power of resisters can also ebb and flow over time, resulting in retrenchment, backlash, and counter movements. The results, therefore, have varied according to the nature of the local culture involved, the society's material circumstances, the means by which DI is introduced, and the current world milieu. Consequently, DI, local culture, and local material and other circumstances have combined in various places and times to produce a combination of cultural clashes and resistance, accommodation, and large-scale social change. Although we recognize conflict and resistance as an important part of the spectrum of responses, we focus below on DI's effects on social change.

Our position is that DI is a powerful force for social change in many parts of the world. Because DI tenets have become embedded into the ideologies of national and international elites and general publics around the world, DI is a powerful force for both individual and social change – a force whose effects are likely to unfold over many decades or even centuries.

Effects of Developmental Idealism on National Policies, Programs, and Laws

An important and extensive body of research variously referred to as “world polity,” “world society,” or “world culture” has documented extensive international dissemination of values and institutions to countries around the world, affecting a wide range of governmental and non-governmental organizations, policies, programs, and laws (Meyer et al. 1997; Boli and Thomas 1997; 1999; Schofer et al. 2012; Krücken and Drori 2009). Many of the values and institutions disseminated internationally overlap with the values of developmental idealism. These instances include the international spread of mass schooling (Baker and LeTendre 2005; Benavot et al. 1991; Benavot and Riddle 1988; Meyer et al. 1977; Meyer et al. 1992; Morrisson and Murtin 2009), family planning programs (Barrett and Frank 1999; Donaldson 1990; Greenhalgh 1996), movements toward gender equality (Berkovitch 1999; Dorius and Firebaugh 2010), and the adoption of human rights treaties and legislation (Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui 2005).

Consistent with world society research, we argue that DI values and beliefs have been globalized to governmental and non-governmental organizations around the world. Particularly indicative of the spread of developmental idealism at the national level was the entrance of many nation-states into the development field early in the 20th century, with the concomitant adoption of national development plans (Hwang 2006). The pace of new plan adoptions increased after World War II, and rose rapidly in the 1960s and early 1970s. After World War II wealthy industrial countries actively encouraged the spread of development plans, and international organizations promoted their adoption to move countries up the developmental ladder to higher levels of economic achievement. By the end of the 1980s, 135 countries had adopted at least one national development plan (Hwang 2006). As one observer noted during the 1960s, “the national development plan appears to have joined the national anthem and the national flag as a symbol of sovereignty and modernity” (Waterston 1965 quoted by Hwang 2006:71). These and other international organizing activities led to a substantial proliferation in national and international developmental organizations (Chabbott 1999).

Another example of the international institutionalization of developmental idealism is the international data infrastructure created to collect, standardize, evaluate, and disseminate quantified metrics of many dimensions of development (Babones 2013). This is a massive endeavor made possible by the partnership of national governments and non-governmental organizations and their shared understanding of and commitment to development. The World Bank, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Freedom House, Transparency International, and the United Nations are just a few of the organizations that collect and disseminate data designed to measure and rank countries according to levels of development.

To illustrate this point, consider four well-known and highly publicized indices of development: the Human Development Index (HDI), the Inequality Adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI), the Gender Inequality Index (GII), and the Gender-related Development Index (GDI). The HDI is a composite of the income, education, and health of each population. The IHDI adjusts the HDI score of each country by the level of inequality in each component of the index. The GII is a composite measure reflecting inequality in achievement between women and men in reproductive health, sociopolitical empowerment, and the labor market. The GDI calculates an HDI country score separately for the male and female populations of each country and then ranks countries based on the ratio of the female value to the male value. Although these four indices measure seemingly distinct societal attributes (e.g., human development, inequality of development, and gender inequality), they reflect a strong country-level association among these several measures of development. They are also consistent in reporting that northwest European ancestry nations are the most developed, sub-Saharan African nations are the least developed, and Latin American and Asian nations fall somewhere in the middle.

The impact of these development rankings is especially powerful because rankings benefit from the prescribed legitimacy of scientific-rationality – wherein the quantification of development is often assumed to measure social reality – as well as the halo effect of northwestern Europe. Further, essential values of DI such as education, contraceptive use and low fertility, gender equality, and social equality are embodied in and propagated by these and similar indices. Because international development statistics such as these are the basis for setting and monitoring development policies and programs, they can exert significant influence over the behaviors and beliefs of individuals, organizations, and nation-states.

Of course, the adoption of a policy or ratification of an international treaty containing DI goals does not necessarily mean that the nation-state involved itself endorses the goals. Rather, it may mean that the nation-state seeks legitimacy within the international community (Cole and Ramirez 2013; Hafner-Burton and Tsutsui 2005; Meyer and Rowan 1977; Schofer and Hironka 2005; Swiss 2009). In fact in many cases, policies or treaties have been endorsed without any intention for implementation. This behavior illustrates the power of DI: even nation-state actors who oppose the tenets of DI recognize the usefulness of publicly espousing DI values to enhance international legitimacy. And evidence indicates that, even lacking immediate national implementation of a DI value-based policy or treaty, the national endorsement alone furthers activists’ efforts toward adoption of the policy or treaty goals (Bob 2005; Hafner-Burton 2008; Murdie and Davis 2012).

Effects of Developmental Idealism on Individuals’ Values and Beliefs

The endorsement and adoption of DI beliefs and values at the national level does not indicate their acceptance by individual citizens. The world society literature recognizes that sometimes values promulgated by international forces do not reach below the levels of nation-state laws and policies to affect the everyday lives of individual citizens (Meyer and Rowan 1977; Schofer et al. 2012). Thus, the international values inherent in national treaties, laws, and constitutions are sometimes decoupled or only loosely coupled to the implementation and practice of these same values in the nation's populace (Meyer et al. 1997). In many other cases, however, we find evidence of penetration to the grassroots level.

Regarding the tenets of developmental idealism in particular, we posit that in many instances its values and beliefs have permeated below national elites and government policies, to become part of everyday life for many citizens around the world. For example, Swindle (2014) has demonstrated the presence of development terminology across millions of books and newspapers published in the English language for the past three centuries, and Melegh (2006) has found the language of development and developmental hierarchy contained in the materials of Western corporations and foundations as well. These findings suggest wide public exposure to developmental thinking and great potential for it to enter general discourse among native English-speaking populations.

In addition, the increasing use of English as a lingua franca suggests that DI values and beliefs have been disseminated outside the countries where English has long been the dominant language. For example, a study in Hungary by Csánóová (2013) in 2009 and 2010 reveals the use of developmental language and images in that country's media, as well as the media's tendency to view countries in ways that are consistent with the development hierarchy promulgated by powerful international agencies.

We also suggest that many of the mechanisms that have spread DI across national borders also have spread it within countries, reaching many ordinary people in everyday life. In fact, considerable evidence indicates near saturation levels of key DI belief and value statements in many populations. Ethnographic data from China, Egypt, India, Nepal, New Guinea, and places in Sub-Saharan Africa indicate that many citizens of these areas understand the concepts of development and developmental hierarchies and use them to describe the world (Abu-Lughod 1998; Ahearn 2001; Amin 1989; Blaut 1993; Caldwell et al. 1988; Dahl and Rabo 1992; Ferguson 1999; Guneratne 1998, 2001; Hannan 2012; Justice 1986; Osella and Osella 2006; Pigg 1992, 1996; Wang 1999).

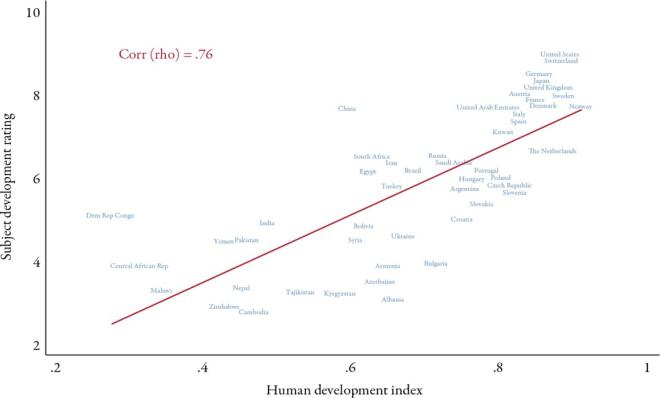

Furthermore, survey data from several countries from diverse settings document that general publics understand development and developmental hierarchies and do so in ways closely resembling descriptions used by the United Nations (Binstock and Thornton 2007; Binstock et al. 2013; Csánóová 2013; Melegh et al. 2013; Thornton, Binstock, and Ghimire 2008; Thornton et al. 2012b). Participants in 16 social surveys fielded in 14 countries and representing every major world region and level of living were asked to rate a set of countries on development on a scale from zero (or one) to ten. In each of the 16 surveys, the average respondent ratings for individual countries closely matched the ratings for the same countries assigned by the UN HDI, with correlations ranging from .75 to .97 (Thornton et al. 2012b; Csánóová 2013). Also, very large percentages of respondents provided country development ratings that correspond closely with the UN HDI scores.

Figure 1 provides a summary view of the strength of agreement between UN HDI ratings on the national development of 55 countries and the average public ratings gleaned from the surveys in 14 countries (Binstock et al. 2013; Csánóová 2013; Melegh et al. 2013; Thornton et al. 2012b).3 Figure 1 shows a remarkable correspondence between respondent averages and UN HDI scores, with the correlation between the two sets of ratings being .76. While these data cannot tell us how respondents around the world gleaned their understanding of the developmental hierarchy that so closely resembles that of the UN, they do demonstrate the penetration of DI beliefs to the general populaces of a fairly large and diverse set of countries.

FIGURE 1.

Correlation between subjective ratings of national development and the HDI.

Notes: Human development index score is from 2000.

Recent evidence from surveys around the world indicates widespread endorsement of other DI tenets as well. As mentioned in the introduction, research indicates that citizens of Lebanon, Egypt, and Iraq commonly believe in cause-and-consequence relationships between economic development and freedom, democracy, and human rights (Thornton et al. 2014a). Similarly, many Hungarian survey respondents link democracy to the concept of development (Csánóová 2013).

Also, general population surveys in Argentina, China, Egypt, Iran, Malawi, Nepal, and the United States document the widespread acceptance of the proposition that development is both a cause and consequence of several dimensions of family life, including marriage, living arrangements, gender roles, and childbearing (Abbasi-Shavazi et al. 2012; Binstock and Thornton 2007; Lai and Thornton 2014; Thornton et al. 2012a; 2012b; 2014a; 2014b). For example, survey data from these seven countries show the perception of a strong link between fertility and development, with large majorities of respondents in each country reporting the beliefs that high fertility is more common in places that are not developed (range = 75%–95%), that development will decrease fertility (range = 73%–95%), and that fertility reductions will increase the standard of living (range = 84%–99%) (Thornton et al. 2012a).

Effects of Developmental Idealism on Individuals’ Behavior

We now turn our attention to some observed effects of developmental idealism on people's behavior. Because of the scope of DI's effects, we cannot cover the entire range of effects, but can only provide brief examples. We begin with marriage and childbearing—two population components that have been central to many development programs.

Reductions in Marriage and Childbearing

The family planning programs initiated after World War II to control fertility in Africa, Asia, and Latin America constituted one of the largest and most successful social movements in history. These programs were motivated by the developmental idealism values and beliefs promulgated by Malthus (1986/1803), who argued that low fertility was good and would reduce human suffering and facilitate development (Barrett and Frank 1999; Donaldson 1990; Hodgson and Watkins 1997; Melegh 2006; Thornton 2005).

This family planning movement encouraged high-fertility countries across the globe to introduce programs intended to increase age at marriage and promote the use of birth control (Barrett and Frank 1999; Donaldson 1990; Greenhalgh 1996; Melegh 2006). This movement also created new contraceptives, established distribution channels for them, and provided expertise and personnel training for program implementation. These family planning programs also devoted efforts intended to increase desire for smaller families and to prompt acceptance and use of the means to limit fertility. Some programs provided aid to incentivize the adoption of family planning behaviors, and some were coercive – monitoring women's menstrual cycles, establishing quotas for reproduction, and forcing sterilization and abortion.

The introduction of family planning programs was often met with skepticism and resistance. For example, the program in Kenya was initially met with verbal endorsement but implementation neglect, with vigorous implementation only coming later (Chimbwete, Watkins, and Zulu 2005). In Malawi, the program initially met with outright government rejection, but was implemented later (Chimbwete, Watkins, and Zulu 2005). India instituted a vigorous sterilization program, which generated so much resistance that it played a role in the fall of a government. China, on the other hand, vocally resisted the idea of family planning, but later reversed direction and instituted its well-known one-child family policy (Greenhalgh 1996). Iran had its own experience: first, governmental acceptance with population resistance; second, a change of government followed by governmental resistance; and third, vigorous governmental support and very rapid fertility decline (Abbasi-Shavazi et al. 2009). Despite initial resistance in many places, family planning programs had become almost ubiquitous in non-Western countries within a few decades (Chimbwete, Watkins, and Zulu 2005; Johnson 1994; Nortman 1985).

In the decades following the introduction of family planning programs, marriage, contraception, and fertility have changed tremendously worldwide. Age at marriage has increased in almost every country (Ortega 2014), contraceptive use is quite common, and abortion is legal and accessible in many places. The global fertility rate has declined substantially over the past four decades (United Nations 2009) and has done so in every world region. In many countries, fertility levels have dropped to replacement level or below (United Nations 2009; Billari and Wilson 2001; Dorius 2008). Although we propose that developmental idealism is an important ideational influence on these global changes in marriage and childbearing, we also recognize the importance of other factors such as industrialization, urbanization, declines in mortality, and increases in economic production and consumption, education, and technological innovation.

Rising Freedom in Family and Personal Relations

We also believe that developmental idealism has significantly influenced changes in romantic relationships and family life in many places around the globe, contributing to increases in nonmarital sex and cohabitation, childbearing outside marriage, divorce, and same-sex marriages (Thornton et al. 2007). The spread of DI beliefs in equality and freedom have helped erode many restrictions on people's behavior in this sphere: marriage being required for sex, cohabitation, and childbearing; childbearing being expected in all marriages; divorce being prohibited or restricted; and marriage being limited to heterosexual couples (Thornton et al. 2007). Although these trends have been especially pronounced in northwest Europe and its overseas populations, trends in the same direction have been found among many populations of eastern and southern Europe, Latin America, and Asia (Cerrutti and Binstock 2009; Esteve et al. 2012; Lesthaeghe 2010; Lesthaeghe and Surkyn 2008; Thornton and Lin 1994; Thornton and Philipov 2009; Cammack and Heaton 2011).

Greater Spouse Choice

Another important area where increasing freedom and the right of consent have been important forces has been in choosing a spouse. Although freedom to choose a spouse has a very long tradition in northwest Europe and its overseas populations, in many non-Western places arranged marriages have predominated until recent decades. Recently, however, many non-western places have seen substantial increases in the prospective bride and groom having important, sometimes determinative, say in the marriage choice (Ghimire et al. 2006; Thornton and Lin 1994; Thornton 2005).

Mass Education

Developmental idealism specifies that education is a key component of the good life and an important mechanism for achieving progress in important life domains such as economic growth, democratization, expansion of individual rights and freedoms, health, and gender equality. These DI beliefs and values have played an essential role in the global expansion of education.

World society scholars identify the global diffusion of mass schooling as a manifestation of supranational institutional isomorphism occurring over time and geographic space (Benavot et al. 1991; Ramirez and Meyer 1980). Were education simply a mechanistic response to the labor market demands of an urban and industrial society, enrollment and attainment rates would not be nearly as high as they are in many countries around the world. Instead, empirical research demonstrates that the expansion of school enrollments after World War II is strongly linked to diffusion processes net of economic productivity and position in the world community (Meyer et al. 1977). This is true of primary and secondary school enrollments and also of higher education (Schofer and Meyer 2005). The value of education has become deeply embedded in worldwide beliefs about individual and societal enhancement, and contemporary transnational actors invest substantial energy and resources to further expand education.

Developmental idealism has contributed to the now taken-for-granted status of education as a universal institution, but it was not always the case that education had such ubiquitous appeal. The origins of the mass education movement that now extends to virtually the entire world can be traced to the Protestant nations of northwest Europe (Cippola 1969; Easterlin 1981). Mass education was rooted in Protestant beliefs in individual responsibility for salvation and the need to adequately empower individuals with the tools of salvation. The ability to read religious texts came to be seen as a formidable inoculation against a host of threats to spiritual enlightenment and progress. As education spread throughout continental Europe and North America, the seeds of mass education were also being planted in many non-Western locales by Protestant and, to a lesser extent, Catholic missionaries (Woodberry 2012). The establishment of schools in Asia and Africa, for example, followed almost immediately after the founding of missions. Although enrollment and attainment rates remained low in many parts of the world until well into the 20th century, developmental models that gradually secularized belief in a causal relationship between education and individual progress expanded well beyond their early Protestant origins.

The period following World War II witnessed a significant global expansion of education. Decolonization gave rise to many newly independent nations eager to establish their place in the world and to emulate the material successes of their former colonizers. And these fledgling nations and the international entities with which they interacted viewed the education of individuals and societies as a key driver of economic and social development of the kind observed in rich Western nations (Fiala and Langford 1987). Development agencies, political leaders in Western and non-Western nations alike, and both religious and secular transnational actors were key to the institutionalization of education in development programs, its association with the good life in the minds of publics around the world, and the global expansion of education.

School attendance and achievement are now at historically high levels and continue to grow in many parts of the world (Dorius 2013; Morrisson and Murtin 2010). An important transfer of power from religious to secular institutions has attended the secularization and institutionalization of education. High education, especially bachelors and postgraduate degree-awarding universities, are particularly important in this transfer of power to secular institutions. Achievers of high education gain unparalleled status, and are seen as capable of directing and defining global development (Frank and Meyer 2007; Meyer 2010; Meyer and Bromley 2013; Schofer and Meyer 2005). In the contemporary world, few question the transformative power of education over individual and collective life. Cultural models that posit causal relations between education and virtually every other feature of development are now deeply embedded in national and global institutions and in the minds of publics throughout the world.

International Relations

We now turn to international relations and the widely accepted observation that development models have influenced relations between Europe and other places—particularly by justifying colonization and slavery of people outside Europe. Here, however, we focus on international relationships within Europe, where one might expect little influence of the developmental idealism model. In this, we accept the view of Wolff (1994) and others that the developmental model led to the invention of Eastern Europe in contrast to Western Europe and that this bifurcation played a role in subsequent European relations (Wolff 1994; Melegh 2006; Böröcz 2000; Sztompka 2004; Bakic’-Hayden 1995; Todorova 1997). We recognize in the following discussion that many powerful forces beyond cultural models influence international relations, including national interests, balance of power concerns, domestic politics, spheres of influence, economic and military resources, and leadership idiosyncrasies.

By the 18th century, many western European Enlightenment writers had accepted the developmental model, documenting their belief that eastern Europe represented an intermediate stage between ‘backward’ Asia and ‘developed’ Europe (Melegh 2006; Neumann 1999; Todorova 1997; Wolff 1994). For example, in the late 18th century, Count Louis-Philippe de Segur, an envoy from the French court to the Russian court, reported that as one departs eastern Prussia and enters Poland, one leaves “a perfected civilization...., believes one has left Europe entirely...., [and thinks] one has been moved back ten centuries” (quoted in Wolff 1994:19). Another Frenchman who traveled to Russia in 1839, Astolphe Marquis de Custine (1987), suggested that “the Russians are not yet civilized” (p. 105), are just “regimented Tartars, nothing more” (p. 105), and are “a half-savage people” (p. 156). This view of eastern European development was not unique to western European thinkers. Trotsky espouses a DI worldview in his monumental work, The History of the Russian Revolution: “The fundamental and most stable feature of Russian history is the slow tempo of her development, with the economic backwardness, primitiveness of social forms and low level of culture resulting from it” (Trotsky 1932: 1).

Wolff has suggested that this Enlightenment-era creation of an Eastern Europe distinct from Western Europe established “the cultural context for presumptuous projects of power” (Wolff 1994:362). He indicated that Napoleon's failed invasion of Russia in 1812 may have been influenced by this cultural model and an underestimation of the intellectual and cultural power of the Russians. He also suggested that this East-West development model impacted French and English involvement in the Crimean and Balkan Wars later in the 19th century, influenced the re-making of Europe following World War I, and affected the way Hitler conducted his eastern campaign during World War II (Wolff 1994). According to Wolff, this model “served to underpin every aspect of German policy toward eastern Europe during World War II” (Wolff 1994:370).

More recently, this model is posited to have played a role in the British, American, and Soviet negotiations regarding post-World War II Europe (Harbutt 1986; Churchill 1953). At one important 1944 meeting between Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin, it was decided that the Soviet Union would have predominant influence in Romania and Bulgaria and little influence in Greece (Churchill 1953; Harbutt 1986; Resis 1978; Yergin 1978). Two years later, Churchill observed that an iron curtain had fallen across Europe, but that Greece—“with its immortal glories”--had remained on the western side of that curtain (Churchill 1946:8-9).

Even the fall of the iron curtain during the late 1980s and early 1990s did not erase the powerful image of an East-West civilizational divide (Wolff 1994). Many in Central Europe had identified themselves as “Europeans” before the iron curtain and saw its fall as an opportunity to go “back to Europe” (Krasnodębski et al. 2003; Kuus 2004; Melegh 2006). Many people now wanted “to escape from the grip of Asia and move toward Western Europe, and finally to realize old pro-Western aspirations and ambitions” (Sztompka 2004:489). As part of this movement to the “West,” many countries opted to join the Council of Europe, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the European Union.