Abstract

Low rates of antenatal care (ANC) service uptake limit the potential impact of mother-to-child HIV-prevention strategies. Zambézia province, Mozambique, has one of the lowest proportions of ANC uptake among pregnant women in the country, despite the availability of free services. We sought to identify factors influencing ANC service uptake (including HIV counseling and testing) through qualitative methods. Additionally, we encouraged discussion about strategies to improve uptake of services. We conducted 14 focus groups to explore community views on these topics. Based on thematic coding of discourse, two main themes emerged; (1) gender inequality in decision making and responsibility for pregnancy and (2) community beliefs that uptake of ANC services, particularly if supported by a male partner, reflects a woman’s HIV-positive status. Interventions to promote ANC uptake must work to shift cultural norms through male partner participation. Potential strategies to promote male engagement in ANC services are discussed.

Keywords: Gender, Pregnancy, HIV/AIDS, Rural, Africa, sub-Saharan, Stigma, relationships

Uptake of antenatal care (ANC) services during pregnancy and delivery via a skilled attendant is associated with reductions in maternal-child morbidity and mortality (Brown, Sohani, Khan, Lilford, & Mukhwana, 2008; Campbell, Graham, & Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering, 2006). The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that pregnant women attend a minimum of four ANC visits during pregnancy to receive health services, but only 36% of women in low-income countries completed the four recommended visits in 2010. Approximately four in ten women underwent HIV counseling and testing during routine ANC in sub-Saharan Africa, a missed window for the majority of these at-risk women (World Health Organization, 2011). Thus while antenatal care provides the potential for identification and treatment multiple issues (anemia and malnutrition, malaria prevention, diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs)), HIV counseling and testing, as well as the provision of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) for the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT), the overall impact relies on wide-scale uptake.

In Mozambique, ANC uptake is improving. Nationwide, 91% of all pregnant women attended at least one antenatal visit during their most recent pregnancy and 51% completed the WHO recommended four or more visits (Ministerio da Saude (MISAU), Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE), & ICF International (ICFI), 2013). Despite high levels of ANC service uptake in every other province (>90%) within Mozambique, the DHS estimates that only 74% of women in Zambézia province attended at least one ANC visit and only 38% attended all four appointments (Friends in Global Health unpublished data 2014; (Ministerio da Saude (MISAU) et al., 2013). In Zambézia, as in the rest of Mozambique, ANC services, including all necessary tests and medications are provided free of charge. HIV testing is offered to all women at each ANC service attended and again during delivery. Despite availability, only 28% of women in Zambézia province received HIV counseling and testing during ANC, among the worst in the country (Ministerio da Saude (MISAU) et al., 2013). The health and education infrastructure in Zambézia province was particularly hard hit by the civil war which ended in the early 1990s, leaving the province with the lowest GDP per capita in the country (Prodeza, 2006). Efforts to re-capacitate the province are only now achieving widespread improvements in health, education, sanitation, and transportation infrastructure (Vergara et al., 2011). One group supporting health capacitation is Friends in Global Health (FGH) (Moon et al., 2010). This international Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) provides HIV technical assistance in Zambézia province to increase ANC uptake, specifically HIV counseling and testing and the timely and appropriate initiation of ART during pregnancy (Ciampa et al., 2012).

Exploration of the clinical, social, economic and cultural barriers to ANC service uptake in sub-Saharan Africa suggest a number of factors may deter engagement in ANC. These factors include distance and transportation (Thaddeus & Maine, 1994), perceived poor treatment by clinicians (Grossmann-Kendall, Filippi, De Koninck, & Kanhonou, 2001), disagreement with clinical practices (Kyomuhendo, 2003), a lack of service availability (Kowalewski, Jahn, & Kimatta, 2000), preference for alternative therapies (Mathole, Lindmark, Majoko, & Ahlberg, 2004; Seljeskog, Sundby, & Chimango, 2006), increased social status if women deliver at home (Bazzano, Kirkwood, Tawiah-Agyemang, Owusu-Agyei, & Adongo, 2008), fear of witchcraft (if the pregnancy is disclosed too early) (Chapman, 2003; Jansen, 2006; Maimbolwa, Yamba, Diwan, & Ransjo-Arvidson, 2003; Ogujuyigbe & Liasu, 2007), a lack of social and financial support from family members (Mrisho et al., 2009), and differing concepts on symptom causation and appropriate treatments (Chapman, 2003; Kyomuhendo, 2003). Despite calls for attention to partner support (Aluisio et al., 2011; Auvinen, Kylma, & Suominen, 2013; Ditekemena et al., 2012; Peltzer, Jones, Weiss, & Shikwane, 2011; Small, Nikolova, & Narendorf, 2013; Tonwe-Gold et al., 2009) the role of partners in ANC uptake and engagement remains largely unexplored. In the Zambézia province, data suggests that male partner accompaniment occurs less than 1% of the time [unpublished data, Ministry of Health 2013].

To explore barriers and facilitators of ANC uptake and HIV counseling and testing during pregnancy as well as generate guidance for the development of culturally situated intervention strategies to improve service uptake, we conducted a series of focus groups with pregnant women, male partners of pregnant women, traditional birth attendants, community leaders, and ANC service providers. Using the situated-Information, Motivation, and Behavioral theory (Amico, 2011), we crafted questions designed to provide researchers and program administrators sufficient information to understand the prevailing beliefs of community members about the importance of ANC service uptake, factors (including clinician behaviors) that motivate or impede women from seeking ANC services, and the ways in which women openly or secretly negotiate seeking ANC services with their partners and families. Given the previously described debate around male-engagement into ANC and PMCTC programs in sub-Saharan Africa, we also focused discussions on the advantages and disadvantages to engaging male partners in these services.

Methods

Study Sites

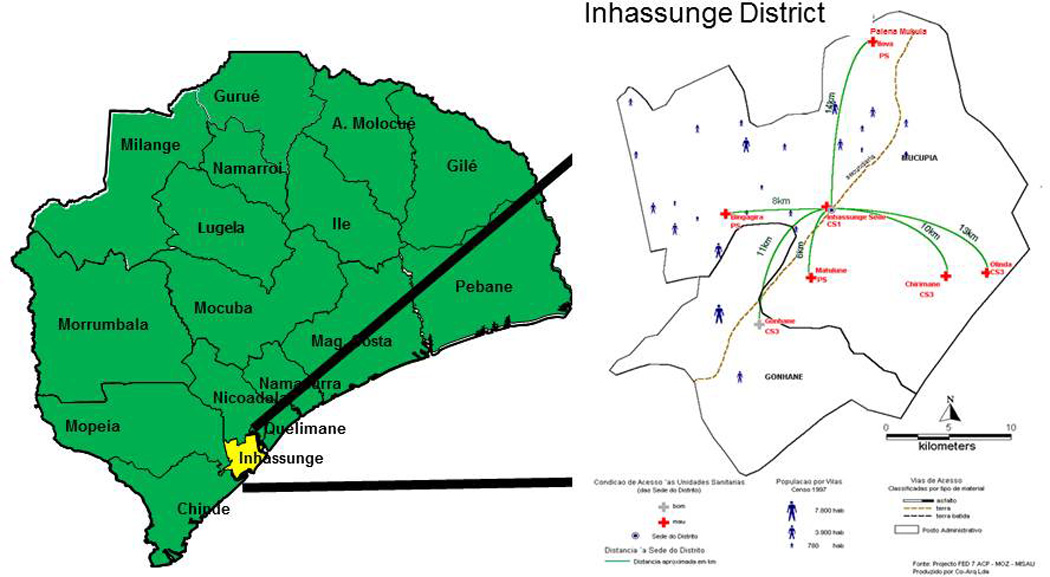

The study was carried out in five rural communities in Inhassunge district, Mozambique from 1 August to 30 September 2012. We chose to study attitudes and social norms in this district (from 18 total districts) for two reasons: (1) uptake of ANC services, including HIV counseling and testing, was reflective of the province as a whole thus we believed our results could inform province-wide initiatives; and (2) Friends in Global Health supports clinical services in this region and could ensure necessary changes to clinic services could be achieved and sustained. The chosen clinical sites included all communities where FGH provided HIV support services (of seven districts in Inhassunge) and clinicians were included in discussions to generate discussions about the reasons pregnant women have provided them for either not attending ANC services at all or who refuse HIV counseling and testing during ANC. HIV prevalence among ANC attendees in this district ranges from 8–26% (data unpublished, Friends In Global Health 2014).

Inhassunge is a small district of approximately 100,000 people (Instituto Nacional de Estatistica, 2007) (Figure 1). The region is isolated, accessible from the provincial capital only by boat across the large Rio dos Bon Sinais (locally called Cuácau or Quá-Qua). Like other districts in Zambézia province, Inhassunge is extremely poor; in 2007 less than 1% of the population had electricity or piped water in their homes (Instituto Nacional de Estatistica, 2007). Low levels of literacy are a challenge to development: in 2007 only 41% could read and write in the official language, Portuguese (Instituto Nacional de Estatistica, 2007).

Figure 1.

Participants

A month before the focus groups were conducted we held meetings with community leaders and the Chief Medical Officer for the district to describe the nature of the study and our desire to interview a diverse group of participants. We requested that the Chief Medical Officer assist us in identifying appropriate staff members from each of the five clinical sites. Participants were selected through purposeful sampling. Community leaders and community health activists actively searched for: (1) men who currently had a pregnant partner or who recently had a baby; (2) women who were pregnant or who had recently delivered a baby; (3) traditional birth attendants (TBAs); (4) influential men in the community (community leaders); and (5) clinicians who routinely provided ANC services. All participants were 18 years of age or older, and aside from the TBAs and community leaders, were of reproductive age. No compensation was offered to participants, but they did receive a drink and a small sandwich during the group. Fourteen focus groups were conducted (five with men, five with women, and four with clinical teams). Focus groups were chosen for our study for three reasons: (1) our experience conducting both focus groups and individual interviews in these rural communities revealed that participants are more comfortable speaking freely in focus groups, revealing more nuanced detail about social norms and beliefs than during individual interviews; (2) we were seeking to gain insight into community norms and behavioral expectations of antenatal health seeking behavior, including uptake of HIV testing and antiretroviral treatment and hospital delivery from the perspectives all multiple influential groups (Kitzinger, 1995); and (3) we wanted our groups to brainstorm solutions to the social, logistical and economic problems presented during the session. Our men’s and women’s groups had 9 to 10 participants each while clinical groups included between four and ten participants. This study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board and the Comité Nacional de Bioética a Saúde in Mozambique; all participants signed or used a thumbprint on an approved consent form after a research assistant read the consent form and provided additional study details to each participant.

Focus groups with men and women were conducted in centralized community meeting spaces (away from any health facilities) in each of the five communities surrounding the health facilities, to ensure there was adequate space for the participants, the note taker and the facilitator and to ensure privacy. The focus groups with clinicians were conducted within an empty meeting room at the clinic. Focus groups were conducted by trained FGH-contracted interviewers who were fluent in the local language but were not from Inhassunge. Questions had been pretested for cultural appropriateness, linguistic understanding, and to ensure they generated sufficient discussion among a group of men and women from Inhassunge who were not enrolled in the study. Several questions were modified to encourage candid discussion, including the addition of questions asking participants about future interventions to improve ANC and HIV counseling and testing uptake. Sessions focused on understanding barriers to women receiving ANC services and having a hospital delivery, male support and engagement in antenatal services and delivery, and HIV testing and treatment uptake during pregnancy. Sample questions can be found in Table 1. Participants also focused on the development of several strategies that could improve uptake of services. We did not seek consensus but instead encouraged all opinions to be openly discussed during the session. The questions asked to men and women were slightly different but covered barriers pertaining to the support of ANC services, including male accompaniment to the health facility, and strategies to improve any barriers that were identified by the group.

Table 1.

Sample Questions from Focus Groups

| 1. How do the male partners encourage and/ordiscourage their female partners to give birth at the health units? |

| 2. Would you [for woman only] like your husbands to accompany you, when you are pregnant to the antenatal care? Why? 3. Would you [for men only] like to accompany your wife to antenatal care? Why? |

| 3. In your opinion, would men like to be involved in the antenatal consultations of their wives, or not? What are the reasons that make you think that way? |

| 4. If a man accompanies his wife to the health unit, for the antenatal consultation, what do other men think about him? What do their partners think of them? What do the health providers think? |

| 5. What do you think could be done to encourage men to accompany their pregnant wives to antenatal care? |

| 6. Which could be the reasons that few partners (men and women) take the HIV test together? |

| 7. What could be done to encourage couples to take the HIV test together? |

Analysis

All discussions were transcribed within a week of the interview in the local language and were subsequently translated into Portuguese by the interviewer and into English by two independent translators to ensure accuracy. A fourth member of the team fluent in all three study languages subsequently reviewed the tapes and transcriptions to verify both the translation and transcription. Clinician focus groups were conducted and transcribed before the community member sessions were conducted to provide additional direction for community groups. The themes were developed inductively but the authors were aware of the findings from previous studies in sub-Saharan Africa which likely guided our initial interpretation of the transcripts. Comparison of focus groups was done using deductive sub-group analysis, comparing the attitudes and experiences by gender, age, and occupation. Two persons participated in the thematic analysis (LC and CMA) both with extensive experience conducting qualitative research (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, 2006). Agreement in coding was reviewed and discrepancies resolved by consensus. A comparison of coding agreement found 91% agreement (using Cohen’s Kappa in MAXQDA).

Conceptual Framework

We use an ecological framework based on the situated-Information, Motivation, and Behavioral model of Health Care Initiation and Maintenance (Amico, 2011) to guide this analysis. The sIMB–CIM model is adopts the core determinants of health behavior identified in the IMB model (Fisher & Fisher, 1992) to the process of initiating and sustaining a particular health behavior over time in a particular sociocultural context in which care is negotiated (Amico, 2011). When evaluating the barriers and facilitators of women’s engagement in ANC services, we focused on: 1) Accurate INFORMATION concerning the value of ANC services, including PMTCT; 2) the MOTIVATION, including the positive and negative attitudes/beliefs about the consequences of seeking ANC service; and 3) BEHAVIORAL SKILLS, including the confidence and skills women and men felt they possessed to fully attend all recommended ANC services and prioritize their own/partners care.

Results

Of the 122 participants in our focus groups, 99 were community members (50 men, 49 women) and 23 were clinical staff (including medical technicians, nurses, and counselors). Clinicians and community members were recruited separately. One hundred community members were approached to participate in our study: 100% agreed to participate and 99% appeared on the appropriate date and time. The median age of the male community members was 46.5 years (IQR 35, 52). The female community members were younger with a median age of 37 years (IQR 30, 46). Median age among women was higher than expected given the inclusion of traditional birth attendants (median age 66 years) and religious leaders/activists (median age 58 years). Aside from these older individuals, participants were all of reproductive age. Participant professions included farmers (21%), teachers (11%), secretaries (7%), religious leaders/activists (17%), traditional birth attendants/traditional healers (11%), and community health outreach workers (4%). Clinicians were more difficult to recruit given high patient loads: forty-five clinicians were approached but only 22 participated for a participation rate of 49%. Clinicians had a median age of 32 years (IQR: 27, 36), were equally split in terms of gender representation, and included nurses (27%), medical technicians (9%), counselors (50%), and clinical managers/facilitators (18%). The only physician working in the area was not available during our interviews.

Analysis of focus group discourse identified two main themes for barriers to uptake of ANC and several facilitators that were both linked to a perceived lack of support from members of their communities, primarily their male partners. This lack of support manifested as barriers to ANC through: (1) gender inequality and (2) HIV stigma. Each main theme for deterrents to ANC uptake is described below. Factors facilitating ANC uptake are also noted within each thematic area in which the discourse occurred. Suggestions for interventions to improve ANC uptake are discussed at the end of the results.

Gender Inequality

Mozambique has worked hard to improve gender equity in education, politics, and economic opportunities, but inequalities continue to impact the economic and social well-being of women and girls (Virgi, 2012). Participant’s highlighted two primary ways gender inequality impacted maternal and paternal participation in ANC services: (a) social stigmatization of partner support and (b) maternal responsibility for pregnancy. The use of alcohol by men exacerbated these issues.

(a) It is socially unacceptable for men to visibly provide support to their partners. Men and women described the support they gave (or received) during their pregnancy. Providing support to a pregnant partner, including accompaniment to an ANC appointment, meant that men had to endure the heckling and mocking of their friends. Providing physical or emotional support to a pregnant partner implied male weakness. These strong social taboos were discussed at length among men, women, and clinicians in each of the five communities. This taboo is fundamentally linked to unequal gender roles and the importance of the man appearing superior to his partner. Women and men both expressed the desire for change, citing social stigma as the primary barrier that needed to be addressed.

A woman in Mucupia best summarized the dynamic between men and women:

First point is that other men think that by doing that [accompanying her to her ANC appointment] he becomes the woman´s slave; others say that he is jealous, that he does not have an active voice in the house; that it is as if he were a chair at home, that the wife sits on top of. When he walks the others immediately comment, saying: "The chair came out of the house, where will the lady sit?" So, if he had a good initiative, he ends up leaving it behind, and starts copying his friends’ behavior. (Woman, 43, traditional birth attendant, Mucupia)

Those who had “good initiative” at the beginning risk ridicule among his peers for accompanying a woman to her ANC appointment. Women know this will occur, and may choose to avoid setting up her husband for this social scorn, even though they prefer being accompanied to the health facility. A woman in Chirimane described the things said to a man who accompanies his partner:

Sometimes he accompanies [her], but when he arrives at the market the others make fun of him saying: “you stopped cutting firewood, drinking cachaço [local alcoholic beverage], [the] only [thing you do is] accompany her?” …This is what sometimes discourages us to ask them to accompany us. (Woman, 26, farmer, Chirimane)

Men describe the same social pressures, and laughed several times during the groups at the thought of the reactions they would receive if they accompanied their wives to their ANC appointment. Other men provided examples of sarcastic comments made to men who accompanied their wives:

I see it this way—the men stay behind and those who do not accompany say: "but that one really, it even looks like that woman of his will give birth to God!" But they said that because they don’t know. But the midwives say that if in the community, some of your friend’s talk bad [things], don´t listen to them, carry on as far as God will lead you. (Man 27, teacher, Mucupia)

There are ignorant men here in the community, when you take your wife to the hospital, upon returning they say that you have been spoiled by your wife. They come fetch you up saying "Let´s go for a walk. Why are you being commanded by your wife?” (Man, 20, bike taxi driver, Gonhane)

The men who spoke of defying social norms to accompany their wives to appointments reported two very divergent rationales. Some supported their wives because they felt a strong bond of friendship with her, and that true friends would support each other even in the face of opposition. Others rationalized their accompaniment as necessary given their right to control their wives actions.

I want to add that us men, when our wives are pregnant we need to be in control, we said that some women are lazy, they are truly lazy to go to the hospital and, us the owners, when we are strong we will control the woman. (Man, 29, church leader, Chirimane)

The suggestion that women are incapable of managing their own affairs without the direction of men was a theme that only appeared in the men’s focus groups.

(b) Women are responsible for their pregnancy. Women highlighted the lack of respect and support they felt was provided by male partners during pregnancy. All women’s groups spoke of husbands in the community losing interest in their wives during pregnancy, resulting in additional strain on the pregnant woman, and in worst cases, abandonment, physical and/or psychological abuse. The health of the woman appeared not to be an important concern for some men. A male community leader explained that many men do not see the baby as their concern until after the birth:

Some men, when a situation such as this one [an ANC appointment] happens, say: "go yourself, the owner [of the baby]". (Man, 53, church leader, P. Mukula)

This sentiment was echoed by the women as well:

When the men get us pregnant they stop giving us attention, they just say that “when you have the baby you can give it to me”. (Woman 18, student, Gonhane)

When they get us pregnant they immediately say "I can´t accompany you to the hospital, you can go by yourself. What I want is just my son". (Woman, 32, farmer, Gonhane)

The common use of alcohol appeared to exacerbate underlying negative gender-based attitudes, and discussions about the common abuse (drinking to the point of inebriation with negative implications for their ability to function) of alcohol among men was identified in the three most rural communities.

A traditional birth attendant in Bingagira explained:

Here in Bingagira [for] some men, it is not due to a lack of information, it is just brutality, some give more value to drinks, when we talk with them they say: if you don´t want to go to the hospital, it is your problem, because the pregnancy is not in my body, it is in yours, so it is up to you.

There was a case in my neighborhood, a pregnant woman went to the hospital, she was sick, when she took the medicine they gave her [at home], she started vomiting, the husband started to insult her, said that if she lost her pregnancy with her vomiting, she would not end up well. Because the woman was taking the medicine by herself, the baby was born sick and ended up dying. When we ask our husbands to take us to the hospital, they say that the disease [pregnancy] is your [our] body, if you don´t want it, leave it. That's because they are drunkards. (Woman, 32, traditional birth attendant, Bingagira)

The consensus in most groups was that women were held responsible for the health of the baby during pregnancy. However there was some discussion among men in Gonhane that suggested young men were equally frustrated with this tradition. A 20 year old taxi driver explained that when he offered to accompany his wife to her ANC appointment, she refused him, saying “"First, sit down. Us the owners [of the baby], we will go". The identification of pregnant women as “owners” of the baby, while men were “owners” of their wives (and the baby after birth) suggests a complicated power dynamic between partners at play.

HIV Stigma

Efforts to reduce HIV stigma, including increased education and access to HIV testing and antiretroviral medication, have been moderately successful in rural Mozambique (Mukolo et al., 2013). Despite these efforts, HIV stigma was still reported as one of the primary reasons women and men avoided: (a) HIV testing during ANC; (b) ANC services because of association of attendance with having HIV.

(a) Avoiding HIV testing. HIV is often first diagnosed during a woman’s ANC appointment. It is common knowledge in these communities that all pregnant women will be asked to take an HIV test and, if positive, will be given medication to prevent their babies from becoming HIV infected. The association of ANC and HIV testing may be having a negative impact on uptake of services. Two men explain:

It´s true, I know that a lot of men forbid women to go to hospital when they are pregnant. Because when she goes there she is tested and I will also be obliged to do the test…For that reason a great number [of pregnant women] stay at home due to a lack of knowledge. Sometimes they [the men] say if you go and do the test it is your own problem. (Male, 40, religious leader, Bingagira)

The same as they are saying. Before we were very behind, now things are changing and we stay behind because of the lack of activists. Some women, when they are told “go to the hospital with your husband”, they say, "I don´t have AIDS, why should I go?” So there it spoils it, because there they want everyone, not only those who have AIDS, but yes, everybody has to go do the analysis, so they know what they have. (Male, 67, teacher, Mucupia)

Both men and women identified the health benefits associated with ANC uptake and early testing and treatment for HIV, both for themselves and their partner. Men spoke of the value of joining their partners at ANC, including increased understanding of the pregnancy (e.g. when to expect the delivery), the potential to identify and cure illnesses previously undetected, and improved relations with their partner. Despite this understanding, the social stigma of accompaniment and a potential HIV diagnosis proves too great of a risk.

A clinician provides insight into why a woman attending ANC alone would also refuse testing:

There are few women tested alone, because they come alone, without partners because when they are tested and take the result home, they take a risk, they are held responsible, as if they are the ones that bring the disease home. (Female, 36, Counselor, Mucupia)

(b) Social stigma of male accompaniment because of association of attendance with having HIV. If a woman attends ANC services and is asked to bring her husband in for testing, she may have trouble convincing her partner to attend given the stigma around HIV/AIDS, making her less likely to return. The assumption that only men who have HIV need to participate in ANC is a barrier to greater participation. If a man does accompany his partner for her ANC appointment, he may be accused of being HIV positive.

Other [some] men when they see the others accompanying their wife, afterwards they ask: "Where were you?" The person responds, and they even say: "You have AIDS, right?" While the person doesn’t. They say "You have already contaminated your wife with AIDS, that´s why you always accompany her to the hospital". (Man, 43, religious leader, Mucupia)

That´s true. It happened to me, I took a big examination at the hospital, but because I always went with my wife, young friends said: "but now, you are always taking your wife to the hospital, so you have that disease they talk about. I asked: which disease? My wife is pregnant, can´t I accompany her to the hospital?" (Man, 42, youth leader, Mucupia)

The stigma associated with a diagnosis of HIV is strong in these communities. Nurses often instruct women to bring their partners to the clinic for testing. But placing the responsibility for this invitation on the woman is a great burden, one that many women refuse to take on alone.

Us women, sometimes when we take the test it comes out positive, when we get home and try to convince our husband to go to the hospital, they refuse, claiming that they cannot have that disease; maybe us women are the ones who got it in the areas where we farm. (Woman, 33, farmer, Chirimane)

Some nurses when we go to the hospital do not receive us, they send us to get our husbands, but if it is one that understands, he accepts, and the others who do not understand say it is your problem because “who gave you that disease? I don´t have it”. And because we want to get better, we receive the pills and hide them in fear of being left [by him]. That also, even [both] women and men, there are those that do not understand. Men also end up hiding the pills. (Woman, 24 farmer, Chirimane)

There is reasonable fear among both men and women that their partners will abandon them should their test results be positive.

Sometimes, as the woman at home I am the most informed, I start doing the treatment alone, hence when my partner finds out it means divorce, while I spoke to him and he denied. (Woman, 26, farmer, Chirimane)

Us women too, as soon as we know that our partner is in treatment, we divorce. There is a lot of discrimination with neighbors or drinking friends. (Woman, 24, farmer, Chirimane)

Given the small sizes of these communities keeping one’s HIV status a secret while receiving treatment is almost impossible. The linkage of HIV with death as well as infidelity makes it difficult for couples to discuss HIV without a strong emotional reaction. The association of HIV with ANC, and the assumption that only women with HIV need to bring their husbands to an ANC appointment, is a barrier for male engagement and uptake of services by pregnant women.

Strategies for Change

The identification of social barriers to male support and engagement in ANC services also led to important suggestions about how to change cultural norms, both within communities and with the clinics. Clinicians in Palane Mecula discussed the idea of employing men who did accompany their partners to be “champions” for male involvement, and support for their partner’s participation, in ANC. They suggested:

This man, for us who are health technicians, is a man to whom it is possible to give good behavior, a good path, to teach the others as well, to accompany their wives. With this man [providing counseling], even those who refuse to accompany their wives, they will have the initiative of accompanying their wives from the beginning until the end; it will enlighten those men who would not like to accompany their wives. (Male, 25, Nurse)

This man is for us a male champion, we shouldn´t miss on the opportunity, as soon as he shows up at the hospital, we have to educate for health in such a way that he understands, more than he already did, the advantages, what are the objectives and transformation for other men who do not attend or that do not accompany their wives; for us he is a male champion… but also, we have to spread the information in the local communication means, we are talking about the radio, television, so that the information reaches them (Male, 28, Medical Technician)

Clinicians also highlighted the importance of engaging men from the first ANC visit, to ensure their participation was not seen to be linked with HIV/AIDS or STI treatment.

Really, men should be involved right from the beginning, because the pregnancy is part of him, there are also the changes in the woman herself that will happen and by staying at home he will not know that the woman will need this or that. So, male involvement in antenatal care has everything to do with the pregnancy as well, so not just to treat HIV/AIDS but also for the monitoring of the whole pre- and postnatal phases. (Male, 33, Counselor)

Discussions with community members about strategies for improvement, women independently identified the issue of male engagement. Without support from partners the difficulties in attending ANC services, uptake of HIV medications (if necessary) and delivery at the health facility is daunting. Women want their partners to be engaged, but they do not feel as if they can achieve this goal alone. In Chirimane, one woman noted that male support is absent due to a lack of knowledge.

If only there could be persons that could make them understand the importance of going with us to the antenatal consultation. Having a group passing by the community to give lectures would help our men to understand better. Those who accompany [their wives] are those who have some information. (Female, 27, Mozambican Youth Organization member, Chirimane)

Specifically women did not want to be the ones responsible to inviting their partners. In Palane Mekula a woman explained: “For me to tell my husband to go to the hospital is very hard, it could only be through the community counselors raising awareness in men to do that.”

Men expressed similar ideas for engagement, explaining that they needed outside assistance to convince their partners that ANC service uptake (and their participation) was important. Community activists were considered essential because “otherwise it will be hard to take our wives to the hospital. Because people are very hard [difficult], like iron.” (Man, 52, teacher, Mucupia). Men described good treatment by clinicians when they did accompany their partners, but older women in two groups expressed the need for nurses to be more accepting of men’s roles in ANC and maternity. In Mucupia a 38 year old farmer suggested:

Even at the hospital, there is the need to explain that they shouldn´t talk badly with our men, because when they accompany us, the health workers say: “you are a man, doesn´t she have a mother, doesn’t she have a sister or mother-in-law? Why isn´t she coming?” So they [the men] become less interested. (Male, 38, farmer, Mucupia)

Discussion

Barriers to male participation in ANC appointments were attributed to social norms that precipitate gender inequality and HIV–associated stigma. Contrary to findings in other sub-Saharan African countries (Auvinen et al., 2013; Ditekemena et al., 2012; Kululanga, Sundby, Malata, & Chirwa, 2011; Mohlala, Gregson, & Boily, 2012; Morfaw et al., 2013), perceived poor treatment by clinicians was not a prominent barrier noted by men in their willingness to accompany their partner to ANC appointments or to participate in couples counseling and testing for HIV. This difference can possibly be attributed to recent sensitization programs developed in this district to change clinician attitudes about including men in ANC services. However, two of the women’s groups did note this lack of respect as a problem when discussing potential intervention strategies. The concern was greatest in older women, suggesting behavior change by clinicians may have occurred recently. Instead, social stigma associated with participating in women’s health and fear of the perception of being dominated by their wife was of primary concern among men in these rural communities. While HIV testing is necessary to begin the cascade to prevent mother-to-child transmission and improve the health of the mother (Stringer et al., 2005), clinicians should invite the partners of all women to ANC appointments to avoid linking male participation with HIV infection.

Legally, women and girls have made significant strides towards equality in Mozambique (United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, 2012). In practice, gender norms still favor the male partner (Bandali, 2011; US Department of State, 2012). New laws protecting women from physical abuse, including marital rape, are seldom reported or enforced in rural areas (US Department of State, 2012). Women are rarely the decision makers in relationships (Victor et al., 2013), they have lower levels of literacy than men (Ministerio da Saude (MISAU) et al., 2013), and social norms dictate that they comply to their husbands commands (Bandali, 2011). New initiatives by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and other funders with a focus on gender based violence have included training clinicians, police officers and community leaders about the importance of gender equality and the reduction of gender based violence, post exposure prophylaxis for women who have been sexually assaulted, and enforcement of legal action against perpetrators, but the effects of these programs are not yet known.

All groups participating in this study discussed the need for male partners to provide logistic, financial and psychological support to increase uptake of ANC services. The current strategy to increase social support for ANC and HIV treatment uptake at home (i.e. directing a woman to bring her husband back for testing if she has HIV or other STI) is fraught with difficulties given several assumptions: (1) the woman is willing and able to try to convince her husband to accompany her to the health facility, which may not be possible (Victor et al., 2013); (2) the male partner accompanies/provides support to his partner because he wants to improve her health and the baby’s; (3) community members value the benefits derived from male accompaniment to an ANC appointment enough to overcome the negative social consequences (Fortenberry et al., 2002; Leaf, Bruce, & Tischler, 1986; Leaf, Bruce, Tischler, & Holzer, 1987; Rusch, Angermeyer, & Corrigan, 2005). Women state the desire to have an outside advocate (community counselor or health worker) to provide both education about the importance of ANC uptake and the invitation to participate in partners ANC services. Instead of requesting that a woman invite her partner to the clinic for testing, the use of “male peers” or “male champions” to encourage partner ANC visits may be more successful in changing social norms and improving uptake.

Regardless of the way in which information is delivered, programs must be conscious of the vastly differing factors that may motivate partner support. Responses from men in this study indicate that a desire to control a partner (because the woman is unable to remember their own ANC appointments and/or follow the advice of the clinicians) is a rational reason to get involved. Men with this attitude may not be supportive partners outside of the clinical setting and we may be putting women at risk of intimate partner violence by encouraging engagement. Thus women’s consent for approaching her male partner and the provision of ANC and HIV education coupled with relationship counseling must be achieved before any invitations are extended.

This study investigated the common attitudes and beliefs regarding partner support and engagement in ANC services. Our purposeful sampling of male and female community members as well as a group of ANC clinicians and counselors from five communities, coupled with thematic data saturation suggests we have adequately captured community norms. However our data is specific to one rural district in Zambézia, and may not be generalizable to urban communities or rural areas with different gender norms. Focus group discussions limit the opportunity for participants to share individual information that might contradict social norms or might otherwise wish to be kept confidential, although we attempted to minimize the impact of gender-based social norms by having same-sex focus groups.

Focus group discussion highlighted two main barriers to engagement in ANC services: gender inequality and the association of ANC with HIV testing (highlighting the stigma associated with an HIV diagnosis). Undertaking an effort to change gender norms is a difficult challenge. Legal barriers, social norms, and economic realities make it difficult for women to demand change. Involving leaders as “champions” to encourage male engagement in ANC may begin to address the social stigma associated with partner ANC attendance. There is a need to continue with stigma reduction efforts; despite the expectation that having access to treatment would decrease community-level stigma, as HIV is still heavily stigmatized.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants, the Mozambique Ministry of Health, and Friends in Global Health staff working in Inhassunge.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article: The ViiV Healthcare provided funding for data collection. CMA is supported in part by Clinician and Translational Science Award (CTSA)/Vanderbilt Clinical &Translational Research Scholars (VCTRS) grant (KL2TR000446).

Biographies

Carolyn M Audet, PhD, MSc, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Health Policy at Vanderbilt University, USA

Yazalde Manual Chire, MBA, is the Male Engagement Strategy Coordinator with Friends in Global Health, Mozambique

Lara Vaz, PhD, is a Senior Advisor, Monitoring and Evaluation, Saving Newborn Lives at Save the Children-USA

Ruth Bechtel, MA, is the Country Director of Village Reach, Mozambique.

Daphne Carlson-Bremer, PhD, DVM, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Health Policy at Vanderbilt University, USA

C. William Wester, MD, MPS, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Infectious Disease at Vanderbilt University, USA.

K. Rivet Amico, PhD, is a Research Associate Professor in the School of Public Health at University of Michigan, USA

Lázaro Calvo, PhD, is the Research Study Manager at Friends in Global Health, Mozambique

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ Contributions: CMA, YMC, RB, LC, CWW, DCB and LV made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study. YMC and LC collected the data. CMA, LV, DCB and LC assisted in the analysis the data. CMA, RB, LV, CWW, KRA, and DCB drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- Aluisio A, Richardson BA, Bosire R, John-Stewart G, Mbori-Ngacha D, Farquhar C. Male antenatal attendance and HIV testing are associated with decreased infant HIV infection and increased HIV-free survival. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(1):76–82. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fdb4c4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amico KR. A situated-Information Motivation Behavioral Skills Model of Care Initiation and Maintenance (sIMB-CIM): an IMB model based approach to understanding and intervening in engagement in care for chronic medical conditions. J Health Psychol. 2011;16(7):1071–1081. doi: 10.1177/1359105311398727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auvinen J, Kylma J, Suominen T. Male involvement and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Sub-Saharan Africa: an integrative review. Curr HIV Res. 2013;11(2):169–177. doi: 10.2174/1570162x11311020009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandali S. Norms and practices within marriage which shape gender roles, HIV/AIDS risk and risk reduction strategies in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique. AIDS Care. 2011;23(9):1171–1176. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.554529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazzano AN, Kirkwood B, Tawiah-Agyemang C, Owusu-Agyei S, Adongo P. Social costs of skilled attendance at birth in rural Ghana. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102(1):91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CA, Sohani SB, Khan K, Lilford R, Mukhwana W. Antenatal care and perinatal outcomes in Kwale district, Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2008;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell OM, Graham WJ Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering, group. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 2006;368(9543):1284–1299. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RR. Endangering safe motherhood in Mozambique: prenatal care as pregnancy risk. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(2):355–374. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciampa PJ, Tique JA, Juma N, Sidat M, Moon TD, Rothman RL, Vermund SH. Addressing poor retention of infants exposed to HIV: a quality improvement study in rural Mozambique. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60(2):e46–52. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824c0267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ditekemena J, Koole O, Engmann C, Matendo R, Tshefu A, Ryder R, Colebunders R. Determinants of male involvement in maternal and child health services in sub-Saharan Africa: a review. Reprod Health. 2012;9:32. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-9-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2006;5(1) [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JD, Fisher WA. Changing AIDS-risk behavior. Psychol Bull. 1992;111(3):455–474. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry JD, McFarlane M, Bleakley A, Bull S, Fishbein M, Grimley DM, Stoner BP. Relationships of stigma and shame to gonorrhea and HIV screening. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(3):378–381. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann-Kendall F, Filippi V, De Koninck M, Kanhonou L. Giving birth in maternity hospitals in Benin: testimonies of women. Reprod Health Matters. 2001;9(18):90–98. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(01)90095-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estatistica. Portal de dados Mocambique. [Retrieved September 30, 2013];2007 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen I. Decision making in childbirth: the influence of traditional structures in a Ghanaian village. Int Nurs Rev. 2006;53(1):41–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2006.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger J. Qualitative Research - Introducing Focus Groups. British Medical Journal. 1995;311(7000):299–302. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalewski M, Jahn A, Kimatta SS. Why do at-risk mothers fail to reach referral level? Barriers beyond distance and cost. Afr J Reprod Health. 2000;4(1):100–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kululanga LI, Sundby J, Malata A, Chirwa E. Striving to promote male involvement in maternal health care in rural and urban settings in Malawi - a qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2011;8:36. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyomuhendo GB. Low use of rural maternity services in Uganda: impact of women's status, traditional beliefs and limited resources. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11(21):16–26. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, Tischler GL. The differential effect of attitudes on the use of mental health services. Soc Psychiatry. 1986;21(4):187–192. doi: 10.1007/BF00583999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaf PJ, Bruce ML, Tischler GL, Holzer CE., 3rd The relationship between demographic factors and attitudes toward mental health services. J Community Psychol. 1987;15(2):275–284. doi: 10.1002/1520-6629(198704)15:2<275::aid-jcop2290150216>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimbolwa MC, Yamba B, Diwan V, Ransjo-Arvidson AB. Cultural childbirth practices and beliefs in Zambia. J Adv Nurs. 2003;43(3):263–274. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathole T, Lindmark G, Majoko F, Ahlberg BM. A qualitative study of women's perspectives of antenatal care in a rural area of Zimbabwe. Midwifery. 2004;20(2):122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio da Saude (MISAU), Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE), & ICF International (ICFI) Moçambique Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde 2011. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FR266/FR266.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mohlala BK, Gregson S, Boily MC. Barriers to involvement of men in ANC and VCT in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2012;24(8):972–977. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.668166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon TD, Burlison JR, Sidat M, Pires P, Silva W, Solis M, Vermund SH. Lessons learned while implementing an HIV/AIDS care and treatment program in rural Mozambique. Retrovirology: Research and Treatment. 2010;(3):1–14. doi: 10.4137/RRT.S4613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morfaw F, Mbuagbaw L, Thabane L, Rodrigues C, Wunderlich AP, Nana P, Kunda J. Male involvement in prevention programs of mother to child transmission of HIV: a systematic review to identify barriers and facilitators. Syst Rev. 2013;2:5. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrisho M, Obrist B, Schellenberg JA, Haws RA, Mushi AK, Mshinda H, Schellenberg D. The use of antenatal and postnatal care: perspectives and experiences of women and health care providers in rural southern Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukolo A, Blevins M, Victor B, Vaz LM, Sidat M, Vergara A. Correlates of social exclusion and negative labeling and devaluation of people living with HIV/AIDS in rural settings: evidence from a General Household Survey in Zambezia Province, Mozambique. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e75744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogujuyigbe PA, Liasu A. Perception and health-seeking behaviour of Nigerian women about pregnancy-related risks: strategies for improvement. J Chin Clin Med. 2007;2(11):643–654. [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Jones D, Weiss SM, Shikwane E. Promoting male involvement to improve PMTCT uptake and reduce antenatal HIV infection: a cluster randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:778. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodez . Support to Rural Development in Zambeiza Province, Mozambique. Mozambique: Mocuba; 2006. Retrieved from http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=3&ved=0CCsQFjAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.finland.org.mz%2Fpublic%2Fdownload.aspx%3FID%3D43105%26GUID%3D%257B7BF68007-1527-45C8-904A-8081E1C836DF%257D&ei=IGWIVJyEFYHogwSShYSYAQ&usg=AFQjCNGuN_jD25fK9CHxMT44N6YzJjl7mQ&sig2=L1DOg5FUkLo_hm5o7x0q2w&bvm=bv.81456516,d.eXY. [Google Scholar]

- Rusch N, Angermeyer MC, Corrigan PW. Mental illness stigma: concepts, consequences, and initiatives to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry. 2005;20(8):529–539. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seljeskog L, Sundby J, Chimango J. Factors influencing women's choice of place of delivery in rural Malawi--an explorative study. Afr J Reprod Health. 2006;10(3):66–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small E, Nikolova SP, Narendorf SC. Synthesizing Gender Based HIV Interventions in Sub-Sahara Africa: A Systematic Review of the Evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0541-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringer JS, Sinkala M, Maclean CC, Levy J, Kankasa C, Degroot A, Vermund SH. Effectiveness of a city-wide program to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS. 2005;19(12):1309–1315. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000180102.88511.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(8):1091–1110. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90226-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonwe-Gold B, Ekouevi DK, Bosse CA, Toure S, Kone M, Becquet R, Abrams EJ. Implementing family-focused HIV care and treatment: the first 2 years' experience of the mother-to-child transmission-plus program in Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire. Trop Med Int Health. 2009;14(2):204–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women. Mozambique is moving towards gender equality. Bulletin on Gender issues in Mozambique, January 2012–April 2012. 2012;(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- US Department of State. Country Reports on Human Rights Practices for 2012: Mozambique. Washington, DC: 2012. Retrieved from http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/hrrpt/humanrightsreport/index.htm?year=2012&dlid=204148#wrapper. [Google Scholar]

- Vergara AE, Blevins M, Vaz LM, Manders EJ, Calvo LG, Arregui C, Olupona OO. Baseline Survey Report: Phase I and II: Zambezia Wide. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt Universit.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Victor Bart, Fischer Edward F, Cooil Bruce, Vergara Alfredo, Mukolo Abraham, Blevins Meridith. Frustrated Freedom: The Effects of Agency and Wealth on Wellbeing in Rural Mozambique. World Development, forthcoming & Vanderbilt Owen Graduate School of Management Research Paper No. 2220849. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virgi ZS. Gender Inequality and Cultural Norms and Values: Root Causes Preventing Girls from Exiting a Life of Poverty. Paper presented at the Global Thematic Consultation, "Addressing Inequalities"; Montreal. 2012. http://www.worldwewant2015.org/node/284178. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global HIV/AIDS Response: Epidemic update and health sector progress towards Universal Access. 2011 http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/20111130_ua_report_en.pdf.